Abstract

Despite nearly two decades since the discovery of gene fusions involving TFE3 or TFEB (“TFE”) in sporadic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the molecular mechanisms underlying the renal-specific tumorigenesis remains largely unclear. The recent publication of the TCGA Network's clear cell kidney cancer paper provides further evidence for the importance of gene fusions by identifying 5 tumors harboring SFPQ-TFE3 fusions that otherwise lacked the common clear cell RCC associated mutation. Herein, we review key molecular features of TFE-fusion RCC, including candidate signaling pathways contributing to oncogenesis and a detailed overview of gene fusion isoforms based on an updated knowledge of TFE genetic organization. A total of 5 TFE3 gene fusions (PRCC-TFE3, ASPSCR1-TFE3, SFPQ-TFE3, NONO-TFE3, CLTC-TFE3) and 1 TFEB gene fusion (MALAT1-TFEB) have been identified in RCC tumors and characterized at the mRNA transcript level, with considerable heterogeneity in exon structure across different tumors, even for the same fusion partners. Common to all TFE3 and TFEB fusion isoforms is the retention of the wild-type protein C-terminus, including domains for DNA-binding, dimerization, and nuclear localization, but interestingly, not transcriptional activation. Despite this, the most widely accepted model explaining TFE-fusion oncogenesis remains the introduction of a constitutively active promoter leading to dysregulated TFE transcriptional activity. A multitude of molecular pathways well-implicated in carcinogenesis are regulated in part by TFE3 and/or TFEB protein, including activation of TGFβ and ETS transcription factors, E-cadherin expression, CD40L-dependent lymphocyte activation, mTORC1 signaling, insulin-dependent metabolism regulation, folliculin signaling, and Rb-dependent cell cycle arrest. Determining which pathways are most important will be critical to discovering the most promising therapeutic targets for this disease. Useful to this goal is a panel of cell lines derived from different TFE3-fusion RCC patient tumors, representing multiple fusion isoforms.

1 Introduction

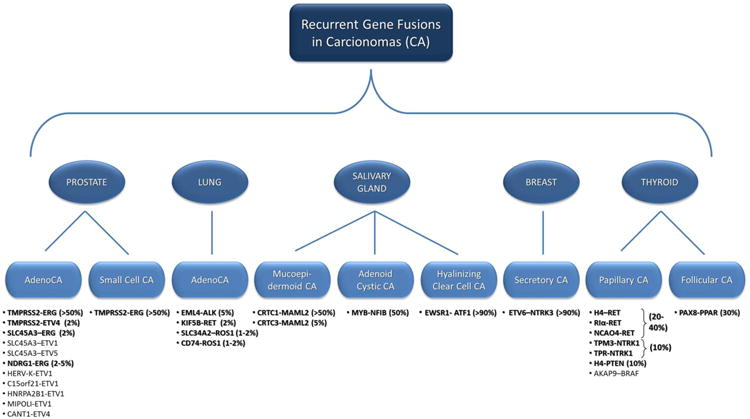

Chromosomal rearrangement resulting in the fusion of two different genes is the most common type of mutation in human cancer.1 The role of these mutations in sarcomas and hematologic malignancies has been well established for several decades but has only recently become more apparent in common carcinomas due to advances in genetic analysis.2 (Figure 1) The Next-generation sequencing of breast and prostate carcinomas has highlighted the common nature of this event in carcinogenesis by demonstrating numerous gene fusions per patient tumor.2-4 Although the effect and importance of all these gene fusions has yet to be fully elucidated, it underscores the fact that they represent a common mutation event.

Figure 1. Recurrent Gene Fusions in Non-Renal Carcinomas.

This demonstrates the currently known gene fusions that have been recurrently shown in Prostate, Lung, Salivary Gland, Breast and Thyroid carcinomas. The listed gene fusions appear in boldface if they occur with an incidence of greater that 1% with the reported percentage shown in parenthesis.

Renal cell carcinomas (RCC) include multiple heterogeneous cancer types originating from renal tubular epithelium.5 Each is defined by a distinct histology, the most common types including clear cell (65-70%), papillary (15-20%), and chromophobe (5-10%).6 Genetic mutations underlying RCC tumorigenesis are increasingly understood, aided by the discovery of least 12 genes (VHL, MET, FH, FLCN, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, TSC1, TSC2, PTEN, MiTF and BAP1) whose germline mutation confers hereditary RCC susceptibility.7,8 Additional insight has come from recent full-exome sequencing efforts in sporadic clear cell RCC tumors including the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network's clear cell kidney cancer project (KIRC). These have revealed the importance of mutations within chromatin remodeling genes, including PBRM1, SETD2, KDM6A (UTX), KDM5C (JARID1C), ARID1A and BAP1, as well as confirming the continued importance of VHL mutation and chromosome 3p loss.9-11

Gene fusions of two genes from the micropthalmia transcription factor (MiT) gene family genetically define a histologically variable group of approximately 1-5% of sporadic RCC tumors.12-14 The MiT family includes four structurally related genes (TFE3, TFEB, TFEC, and MiTF), which regulate a variety of tissue-specific functions contributing to cell differentiation. (Table 1, Figure 2) While one member of the family, MiTF, has been associated with hereditary RCC susceptibility; two other members, TFE3 and less commonly TFEB, are found fused to other genes in sporadic RCC tumors that are often referred to as “translocation RCC”, although chromosomal rearrangements other than translocations can also cause these fusions. In contrast to the histologically defined RCC types, these gene fusion associated kidney cancers are more common among pediatric patients, with the prevalence peaking in early adulthood.15,16 Clinical behavior of RCC with the TFE3 fusion is relatively aggressive, with metastasis common at presentation. Yet despite nearly two decades since the discovery of the MiT family gene fusions in RCC, the molecular biology underlying these cancers remains largely uncharacterized and effective targeted therapies are yet to be identified. Hence, there remains no clinical standard available for pharmacologic treatment of these patients.15

Table 1. Mutations of MiT family of transcription factors observed clinically.

| MiT member | Chromosome | Mutations in RCC | Mutations in other neoplasms |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MiTF | 3p14.1 | Germline activating amino-acid substitution | Melanoma: germline activating amino-acid substitution, gene amplification |

|

| |||

| TFE3 | Xp11.2 | Gene fusions with PRCC, ASPSCR1, SFPQ, NONO, CLTC | Alveolar soft part sarcoma: gene fusions with ASPSCR1 Perivascular epithelial benign tumors (a.k.a., PEComas): gene fusions with SFPQ/other genes? |

|

| |||

| TFEB | 6p21.2 | Gene fusion with MALAT1 | None known |

|

| |||

| TFEC | 7q31.2 | None known | None known |

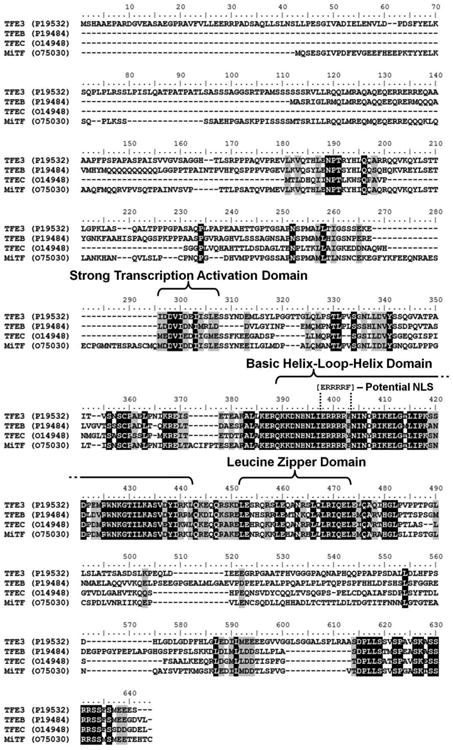

Figure 2. ClustalW Alignment of the TFE3, TFEB, TFEC, and MiTF gene protein sequences.

Multiple sequence alignment using the protein sequence of the four genes of the micropthalmia transcription factor (MiT) gene family (TFE3, TFEB, TFEC, and MiTF) was performed using the ClustalW function of Bioedit Sequence Alignment Editor (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). The shared protein functional domains are highlighted as well as the potential nuclear localization signal (NLS) within the commonly retained region. Black shading = 100% homology, gray shading = 75% homology.

Critical to developing effective therapeutics for RCC patients with TFE3 or TFEB gene fusions is identification of the key clinical pathways driving these particular cancers. Herein, we summarize the contemporary understanding of the molecular biology underlying these gene fusion associated (translocation) RCCs, which we subsequently refer to within as “TFE-fusion RCCs”. Our report includes an up-to-date overview of the candidate mechanisms and signaling pathways thought to contribute to oncogenesis, as well as a detailed description of gene fusion structures based on an updated understanding of TFE3 and TFEB genetic organization. Clinical traits and management recommendations for TFE-fusion RCC patients are reviewed in detail elsewhere.15

2 Multiple TFE gene fusion partners: a historical perspective

2.1 Transcription factor binding to IGHM enhancer 3 (TFE3)

The first documented case of an Xp11 rearrangement in an RCC tumor was described over 25 years ago as a t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) translocation in a pediatric patient.17 Follow-up reports revealed this translocation to be a recurrent mutation in adults.18,19 At this time, three immortalized cell lines (UOK120, UOK124, and UOK146) derived from RCC patient tumors with papillary-like histology and the t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) mutation were established in our laboratory, and their study led to the cloning and description of the first gene fusion in RCC, PRCC-TFE3, in 1995.20-23 This fusion was noted to link the gene encoding a previously described transcription factor, Transcription factor binding to IGHM enhancer 3 (TFE3), on chromosome Xp11.2 with a novel gene on chromosome 1q21.2, designated Papillary renal cell carcinoma (translocation-associated) or PRCC at the time due to its presumed importance in papillary RCC oncogenesis. This discovery marked the first gene fusion identified in a carcinoma other than thyroid cancer.

Subsequently, two other RCC patient cell lines were created within our laboratory (UOK145 and UOK109) harboring two novel Xp11.2 rearrangements, t(X;1)(p11.2;1p34) and inv(X)(p11.2;q12), from which we cloned and described two additional gene fusions, SFPQ-TFE3 (previously referred to as PSF-TFE3) and NONO-TFE3 (previously referred to as p54nrb-TFE3), respectively.24 This work underscored that TFE3, rather than PRCC, was the critical gene fusion partner. Intriguingly, both the Splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich (SFPQ) and Non-POU domain containing, octamer-binding (NONO) genes were noted at this time to encode functionally conserved mRNA-splicing proteins, possibly implicating this process in TFE3-fusion oncogenesis or that nuclear localization was important. Characterization of the NONO-TFE3 fusion, resulting from inversion of the TFE3 and NONO loci on chromosome Xp, revealed that chromosomal rearrangements other than translocations could generate TFE3 gene fusions.

In 2001 and 2003, Argani et al identified the 4th and 5th TFE3 fusions in RCC, ASPSCR1-TFE3 (previously referred to as ASPL-TFE3) and CLTC-TFE3, respectively.25,26 Both the Alveolar soft part sarcoma chromosome region, candidate 1 (ASPSCR1) and Clathrin - heavy chain (CLTC) were found to localize to chromosome 17q. The former was cloned as a novel gene of unknown function and remains as such to date, while the latter had been previously cloned as the heavy chain component of the vesicular transport protein, clathrin.25,26

A total of five partner genes have thus been identified in fusions with TFE3. (Table 2) Only three of these five TFE3 gene fusions (PRCC-TFE3, ASPL-TFE3, and PSF-TFE3) are confirmed as recurrent mutations in multiple RCC patients with differing gene fusion boundaries being observed and designated as “types”, while NONO-TFE3 and CLTC-TFE3 have thus far each been identified in only a single patient. TFE3 gene fusions are not unique to RCC patients. The ASPSCR1-TFE3 fusion was originally identified in 100% of alveolar soft part sarcomas (ASPS), a rare lung cancer variant with no known RCC association, and the SFPQ-TFE3 fusion and possibly other TFE3-fusions are also found in a subset of rare tumors known as perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas).27,28 The existence of additional TFE3-fusion partners is suggested by case reports of Xp11.2 rearrangements with other chromosomal loci in RCC tumors, including 3q23 and 19q13.1, however TFE3 fusions were not genetically confirmed in these studies.29,30

Table 2. TFE3 Gene-Fusions in RCC.

| Chromosomal Rearrangement | Gene Fusion | Type | Cell Line | Fusion Gene | Fusion Protein | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ Gene Exons | TFE3 Exons | Animo Acids | Predicted Mass | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| t(X;1)(p11.2;q21) | PRCC-TFE3 | 1 | UOK120, UOK146 | 1 | 4-10 | 553 | 58.4 kDa | Sidhar et al21, Argani et al36 |

| PRCC-TFE3 | 2 | UOK124 | 1-4 | 4-10 | 790 | 85.6 kDa | Sidhar et al21, Argani et al26 | |

| PRCC-TFE3 | 3 | - | 1 | 5-10 | 471 | 49.8 kDa | Argani et al36 | |

| PRCC-TFE3 | 4 | - | 1-2 | 6-10 | 452 | 47.8 kDa | Argani et al36 | |

|

| ||||||||

| t(X;1)(p11.2;p34) | SFPQ-TFE3 | 1 | UOK145 | 1-9 | 6-10 | 942 | 102.0 kDa | Clark et al24 |

| SFPQ-TFE3 | 2 | - | 1-9 | 5-10 | 977 | 105.7 kDa | Chang et al37, Zhong et al38 | |

| SFPQ-TFE3 | 3 | - | 1-6 | 2-10 | 1,102 | 118.0 kDa | Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network11 | |

|

| ||||||||

| t(X;17)(p11.2;q25) | ASPSCR1-TFE3 | 1 | FU-UR1 | 1-7 | 6-10 | 591 | 63.7 kDa | Ladanyi et al27 |

| ASPSCR1-TFE3 | 2 | - | 1-7 | 5-10 | 626 | 67.4 kDa | Ladanyi et al27 | |

|

| ||||||||

| inv(X)(p11.2;q12) | NONO-TFE3 | - | UOK109 | 1-9 | 6-10 | 657 | 75.1 kDa | Clark et al24 |

|

| ||||||||

| t(X;17)(p11.2;q23) | CLTC-TFE3 | - | - | 1-17 | 6-10 | 1,212 | 136.1 kDa | Argani et al36 |

The recent publication of the TCGA Network's clear cell kidney cancer project (KIRC) paper provides further evidence for the importance of gene fusions in RCC and identified 5 tumors harboring SFPQ-TFE3 fusions by RNASeq analysis.11 These newly identified TFE-fusion RCCs provided both a new type of SFPQ-TFE3 fusion, with gene boundaries including more of the TFE3 gene than any previous fusion (Table 2), and the most intense genetic analysis of a TFE-fusion RCC. Exome sequencing analysis demonstrated that only one of these tumors had a VHL mutation, normally very common in cell clear RCC, and no tumors demonstrated mutations in any of the commonly mutated genes in clear cell RCC (PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1, MTOR, PIK3CA, ARID1A, ATM, PTEN, KDM5C).11 This lack of mutation in RCC associated genes strongly suggests that the TFE-fusions are the driving force in these tumors without the necessity for common associated mutations.

2.2 Transcription factor EB (TFEB)

Chromosomal rearrangements resulting in the fusion between the Transcription factor EB (TFEB) gene on chromosome 6p21.2 and the non-protein encoding Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 gene known as MALAT1 (previously referred to as Alpha) on chromosome 11q13 is the most recently described gene fusion in RCC.31,32 Its discovery provided the initial evidence of a common role for the MiT family in kidney cancer. Less than two dozen cases are documented with genetic confirmation of the MALAT1-TFEB fusion or t(6;11)(p21.2;q13) mutation to date, and the incidence of this fusion is approximately 1:15-1:20 compared to that of TFE3 fusions.15 No cell line has yet to be derived from TFEB-fusion RCC patients. In contrast to the multiple fusion partners of TFE3, no TFEB fusion partners other than MALAT1 are presently known, although a t(6;17)(p21;q24-25) translocation reported in a pediatric RCC tumor has suggested a potential novel TFEB fusion partner on chromosome 17q24-25, the same locus of the ASPSCR1 gene found in TFE3 fusions.33 Also in contrast to TFE3 fusions, the MALAT1-TFEB fusion may be associated with a favorable clinical prognosis.15

3 TFE Gene Fusion Structure and mRNA Transcript Isoforms

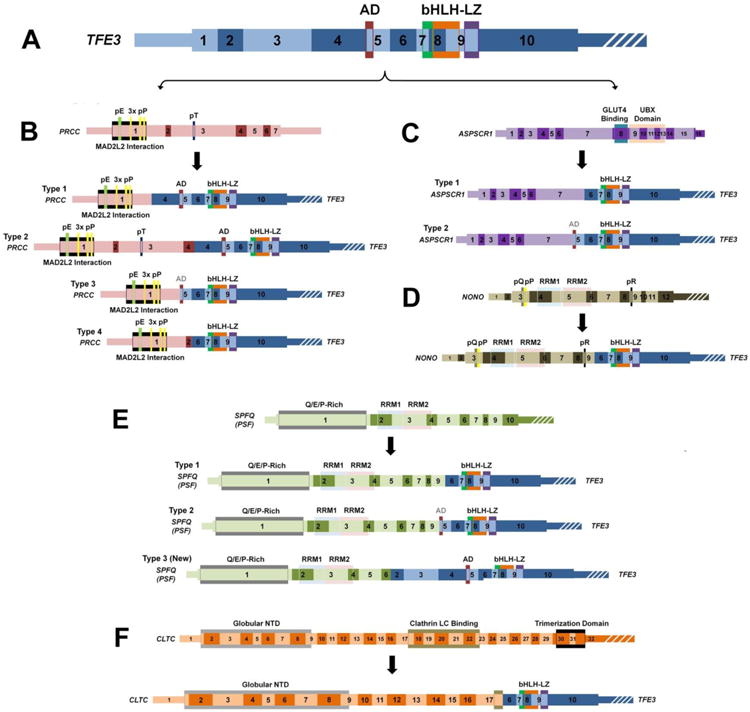

The precise nucleic acid site of the fusion between TFE3 or TFEB and their respective fusion partners varies and can produce fusions containing differing number of exons in the case of TFE3 and its gene partners. Accordingly, different mRNA transcript isoforms have been characterized for most known TFE fusions and have been designated with a numbered “type”. (Figure 3) Unfortunately, the published literature invokes some confusion regarding the structure of chimeric TFE3 transcripts, due to inconsistencies in exon nomenclature following the recent identification of two additional upstream coding exons and a novel transcriptional start site. Here we provide a summary of different TFE fusion transcript isoform structures characterized to date, based on comparison of sequence data from the TFE-fusion literature and contemporary genetic databases, including the UCSC Genome Browser on Human (February 2009; GRCh37/hg19; http://genome.ucsc.edu), the Ensembl database (release 69 - October 2012; http://www.ensembl.org/) and the UniProt Protein Database (November 2012; http://www.uniprot.org). (Table 2, Figure 2)

Figure 3. A schematic of the known TFE3 gene fusions.

This scale schematic demonstrates the exons and functional domains of the TFE3 gene (A - blue), PRCC gene (B - pink), ASPSCR1 gene (C - purple), NONO gene (D - dark green), SPFQ (PSF) gene (E - light green), CLTC gene (F - orange), and highlights the region/type of fusion with the TFE3 gene. The known fusion genes are shown below each specific partner gene to demonstrate the retained exons/function domains for each fusion gene. The strong transcription activation domain (AD) crosses an exon boundary and is shaded black if all of the domain is retained and grey if only part of the domain is retained. Thin regions represent non-coding sequence, while thick regions represent the translated reading frame and white strips indicate the region is no longer to scale. bHLH = Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Domain, LZ = Leucine Zipper Domain, pE = Poly-Glutamate, pP = Poly-Proline, pT = Poly-Threonine, pQ = Poly-Glutamine, pR = Poly-Arginine, UBX = Ubiquitin Regulatory X, RMM = RNA-Recognition Motif, NTD = N-Terminal Domain.

3.1 Wild-type TFE3

The TFE3 gene (Figure 3A) is encoded by 14,749 base pairs (bp) on chromosome Xp11.22 and produces a 3,431-bp mRNA transcript consisting of a 238-bp 5′ untranslated region (UTR) followed by ten coding exons and a 1,427-bp 3′ UTR (NM_006521.4). The coding region includes a start codon in exon 1 and stop codon in exon 10. Wild-type TFE3 mRNA is translated into a 575 amino-acid (AA) protein (61.5 kD) sharing highly conserved peptide domains with other MiT family members, including a 12-AA transcription activation domain (AD 260AA-271AA) spanning exons 4-5, a 54-AA basic region and helix-loop-helix domain (bHLH 346AA-399AA) within exons 7-9, and a 22-AA leucine-zipper domain (LZ 409AA-430AA) within exons 9-10. (Figure 2, Figure 3A) The bHLH and LZ domains mediate dimerization and DNA binding,34,35 and the former additionally contains a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS).

3.2 TFE3 gene fusions

The exact breakpoint site in TFE3 fusions varies and is presumed to occur with different introns of both the TFE3 gene and its fusion partners. Pre-mRNA splicing of the gene fusion generates a chimeric mRNA transcript fused at exon-exon junctions that maintains a coding open reading frame that reads from one partner gene to the other and it is these transcripts that have been successfully mapped to define the gene fusion types. The chimeric mRNA transcripts encode the N-terminal portion of each fusion partner linked to a range of the C-terminal encoding exons of TFE3, including the recently identified SFPQ-TFE3 type 3 fusion that contains nearly the entirety of TFE3 (exons 2-10). (Figure 3B-F) The TFE3 exon 1 is invariably absent (reports prior to 2004 of exon 1 in chimeric transcripts refer to exon 3 using updated nomenclature )and the universally retained region of the TFE3 gene (exons 6-10) corresponds to a 280-AA C-terminal peptide, which includes the bHLH/LZ dimerization/DNA-binding domains and the putative NLS, but not all of the strong transcription activation domain.21,23-26,36-38 The TFE3-PRCC fusion has the greatest degree of transcript heterogeneity, with at least four isoforms characterized to date.21,23,36 The reciprocal transcript encoding the TFE3 N-terminus fused to the fusion partner C-terminus is not consistently generated, and is thus generally believed to be unimportant in TFE3-fusion oncogenesis.21,23,25 TFE3 fusion proteins vary considerably in size, from the smallest PRCC-TFE3 isoform (type 4) at 452 AA (47.8kDa) to the largest CLTC-TFE3 at 1,212 AA (136.1 kDa), more than twice the size of the wild-type protein. (Table 2, Figure 3) As described above, a series of cell lines have been derived from the tumors of TFE3-fusion RCC patients that represent most of the different gene fusions, including multiple PRCC-TFE3 isoforms. (Table 2)

3.3 Wild-type TFEB

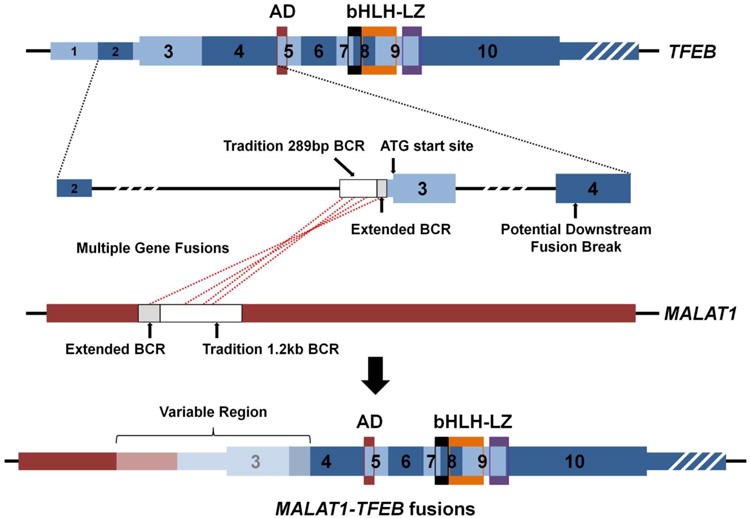

The TFEB gene is encoded by 51,083 bp on chromosome 6p21.1. The gene encodes a 2,364bp mRNA transcript consisting of two non-coding and eight coding exons, with a 302-bp 5′ UTR followed by a start codon in exon 3, and a stop codon in exon 10 followed by a 621bp 3′ UTR (NM_007162.2). (Figure 4) A variant transcript isoform contains only one alternative non-coding exon (NM_001167827.1). Wild-type TFEB mRNA produces a 476-AA protein similar to TFE3 with a 10-AA strong transcription activation domain (AD 156AA-165AA), a 54-AA basic region and helix-loop-helix domain (bHLH 235AA-288AA) containing a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a 22-AA leucine-zipper DNA-binding domain (LZ 298AA-319AA). (Figures 2, Figure 4)

Figure 4. A schematic of MALAT1-TFEB gene fusions.

This scale schematic demonstrates the exons and functional domains with the TFEB gene and highlights the regions of fusion with the non-coding MALAT1 gene. The white box regions represent the traditional breakpoint cluster region (BCR) and the grey boxed regions represent the recently published extensions to BCR (Inamura et al43). To date, all but one fusion has occurred before the initial ATG translational start of TFEB with a single downstream fusion breakpoint reported in exon 4 (Inamura et al43). Thus, all MALAT1-TFEB gene fusions contain an upstream MALAT1 region (red) and the majority of the TFEB gene (blue) with differing amounts of the “variable region” (light red/blue).

Thin regions represent non-coding sequence, while thick regions represent the translated reading frame and white strips indicate the region is no longer to scale. AD = Strong Transcription Activation Domain, bHLH = Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Domain, LZ = Leucine Zipper Domain.

3.4 TFEB gene fusions

MALAT1-TFEB fusion breakpoints generally occur before the start codon in TFEB exon 3, resulting in retention of the complete TFEB coding sequence. (Figure 4) Until recently, all MALAT1-TFEB fusions were believed to occur within a 289-bp breakpoint cluster region (BCR) upstream of TFEB exon 3, and within a 1,205-bp BCR of MALAT1.31,32,39-42 (Figure 4) However, a recent report by Inamura et al of three new cases of TFEB-fusion RCC has suggested a wider range of the traditional BCRs in both TFEB and MALAT1.43 This study also suggested that a breakpoint can occur in TFEB exon 4, after the start codon, although the protein product produced was shown to be a similar size to the wild-type protein.43 (Figure 4)

4 Developmental Roles of MiT Transcription Factors

TFE3 and TFEB are members of the MiT transcription factor family, which also includes TFEC and the prototype member, MiTF. MiT transcription factors form homo- or heterodimers that bind target promoters at a consensus E-box sequence motif (CA[C/T]GTG). Members have overlapping transcriptional target specificity due to highly conserved bHLH and LZ domains.35,44 MiT functions are diverse and tissue-specific, often related to cell growth and differentiation. With the exception of TFEC, all MiT members have ubiquitous tissue expression, although activity is still tightly regulated in a tissue-specific manner.45-49 This may occur in part through tissue-specific splicing, which in turn may be mediated by promoter multiplicity.50,51 Additionally, TFEC inclusion can repress transcriptional activation by its family members in heterodimers, adding another potential level of regulation complexity.52

The most well characterized function of the MiT family is its master regulatory role in melanocyte differentiation, best described for MiTF. Over a dozen rodent models with germline MiTF mutations in the bHLH-LZ regions are described with various pigmentation defects including albinism, ocular defects (micropthalmia), and deafness.35,53-58 In humans, heterozygous MiTF mutations are responsible for Waardenburg Syndrome IIA, characterized by melanocyte deficiency and similar phenotypic manifestation. Melanocytic differentiation appears to be mediated by MiT transcriptional activation of key melanocytic enzymes, tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins (TRP)-1 and -2.59,60 Important in this role may also be the ability of MiT members to bind and enhance activity of the LEF-1 protein, a mediator of the Wnt signaling pathway.61

Another well-described role of the MiT family is the regulation of hematopeotic cell differentiation, including for macrophages, osteoclasts, lymphocytes, and mast cells.53,62-66 Phosphorylation of either TFE3 or MiTF by p38 MAP kinase in response to osteoclastogenic cytokines, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) is required for osteoclast differentiation.67,68 Several osteoclast-related genes targeted by MiT transcription factors may play a role, including CLCN7, cathepsin K, Oscar, Ostm1, and TRAP.62,69-71 Importantly, either MiTF or TFE3 alone is sufficient to activate osteoclastogenesis, underscoring the phenomenon of functional redundancy within the MiT family, with one member able to rescue loss of another.35,62,72,73 Certain MiT gene mutations may act as a “dominant negative” if they inhibit protein function but allow continued heterodimerization. Hence, MiTF mutations in the basic domain lead to osteoporosis in mice despite wild-type TFE3, presumably due to TFE3 sequestration in transcriptionally inactive heterodimers with the mutant MiTF protein.

5 Mechanism of TFE-Fusion Oncogenesis: Dysregulated Protein Activity

Oncogenic activity of TFE3 gene fusions has been demonstrated in various preclinical cancer models. For example, ectopic expression of the PRCC-TFE3 fusion confers tumorigenicity to fibroblast cells in nude mice and enables benign proximal renal tubule cells to overcome in vitro growth arrest.74 Similarly, expression of the NONO-TFE3 fusion is required for soft-agar colonization by the UOK109 TFE3-fusion RCC cell line.72 However, the molecular mechanisms behind TFE-fusion renal oncogenesis remain poorly understood. Three different models can be proposed to explain the oncogenic behavior of gene fusions in general. The first model (“lost activity model”) presumes a wild-type tumor-suppressive gene function which is disrupted by the gene fusion; however, a fusion protein is not generally translated in such cases. The second model (“novel activity model”) involves a novel transforming activity in the fusion protein due to altered protein conformation. In the third model (“dysregulated activity model”), which is the most widely accepted for TFE3 gene fusions, the fusion protein upregulates oncogenic activity already present in the wild-type protein through introduction of a more active or less tightly controlled transcriptional promoter that is not regulated in a similar manner to wild-type TFE3 promoter. Consistent with this mechanism, all TFE3 fusion partners have constitutively active gene promoters, and TFE3 fusion proteins are expressed at dramatically higher levels than wild-type TFE3.23,24,26,32,74-76 Furthermore, the dysregulated activity model is known to be the mechanism for TFEB-fusion oncogenesis, with MALAT1-TFEB fusions generally upregulating a full-length wild-type TFEB protein as opposed to a chimeric protein. The dysregulated activity model is consistent with gene fusion mechanisms in other cancers, in which promoter substitution leads to upregulation of a transcription factor oncogene, such as TMPRSS2-ERG in prostate cancer. (Figure 1)

The dysregulated activity model suggests therefore that function of the wild-type TFE3 and TFEB proteins (and perhaps other MiT family members), irrelevant of the gene fusion mutation, is at least in part pro-oncogenic and the MiT family members oncogenic activity has in fact been described in various cancer types.72,77 In a preclinical model of clear cell sarcoma (CSS), for example, wild-type TFE3 protein and wild-type MiTF protein can both mediate the mitogenic activity of the pathognomonic EWS-ATF1 oncoprotein.72 While in UOK109 RCC cells, wild-type MiTF can rescue soft-agar colonization inhibited by endogenous NONO-TFE3 knockdown.72 Wild-type TFEB similarly has mitogenic effects in some cancer types.77 The oncogenic activity of MiT members is also supported by clinical observations. For example, MiTF is amplified in 20% of metastatic melanomas, and a germline activating MiTF amino-acid substitution recently been identified in association with increased risk of RCC and/or melanoma.78-80 (Table 1) In RCC patients, higher TFE3 expression correlates independently with worse patient outcomes.81,82

6 Candidate Dysregulated TFE Signaling Pathways

6.1 Diversity of TFE signaling pathways

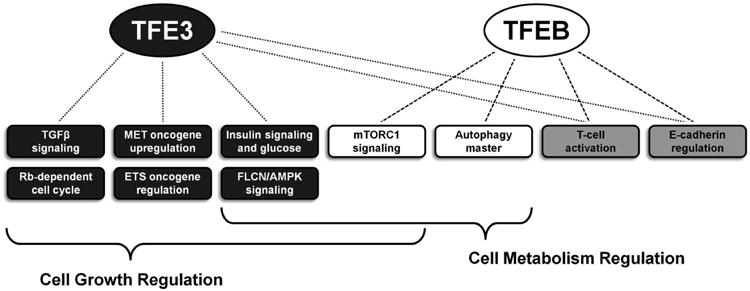

A variety of signaling pathways are employed by TFE3 and TFEB, the dysregulation of which might contribute to renal carcinogenesis. (Figure 5) TFE3 is known to cooperate with SMAD proteins in mediating the TGFβ signaling pathway, which has a well-characterized role in carcinogenesis regulation. Important to this mechanism may be transcriptional activation of the plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1) gene, a regulator of fibrinolysis implicated in the metastasis of many cancer types.83,84 TFE3 also directly binds and enhances activity of ETS-1, the prototype member of the ETS transcription factor family found in gene fusions among prostate cancer and sarcomas.85 TFE3 and TFEB additionally govern transcription of E-cadherin, an important regulator of cancer cell-cell interactions, as well as CD40L, the primary activator of T-cell lymphocytes, raising a possible role in tumor immunoevasion.73,86

Figure 5. TFE3 and TFEB functions that could potentially contribute to caricinogenesis.

The functions and pathways associated solely with TFE3 are highlighted in dark grey boxes and those solely associated with TFEB in white boxes. The light grey boxes represent functions and pathways associated with both genes and the brackets highlight the multiple pathways involved in more broad global pathways such as growth and metabolism.

Both TFE3 and particularly TFEB have also been implicated in mTORC1 signaling, a major regulator of protein synthesis contributing to tumor growth for many cancer types, including RCC.87 Argani et al reported mTORC1 activation to be more common among TFE3-fusion RCC tumors relative to clear cell RCC tumors, based on higher phosphorylated levels of the downstream mTORC1 target, S6.88 We have similarly observed the frequent activation of mTORC1 signaling in a panel of TFE3-fusion RCC cell lines, with variable suppression of cancer cell growth using a selective mTORC1 inhibitor.89 Additionally, phosphorylation and nuclear localization of TFEB was recently found by Pena-Llopis et al to be regulated by mTORC1 in some cell types.77 Drugs with selective mTORC1 inhibition have been studied in a small number of TFE-fusion patients, with occasional but inconsistent patient responses.90,91

6.2 TFE and Metabolic Regulation

Kidney cancer is a metabolically driven disease, as evidenced by the involvement of many kidney cancer genes within major metabolic pathways.92 Similarly, both TFE3 and TFEB appear to play roles in regulating metabolic pathways. (Figure 5) In liver and muscle, TFE3 governs insulin signaling and glucose metabolism through upregulation of IRS-2 and the hexokinase enzymes, inhibiting lipogenesis and increasing glycogen synthesis.93,94 We have also shown in a Birt-Hogg-Dubé preclinical model that TFE3 activity may be inhibited by expression of Folliculin, a protein found in complexes with AMPK, the primary sensor of cell energy and a putative tumor suppressor.95 TFEB may similarly have a key energy sensing role. The TFEB gene product has been identified as a master transcriptional regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, the cellular process by which nutrients are recycled during periods of cellular starvation.96,97

6.3 TFE3 and Cell Cycle Regulation

There is some evidence to suggest that dysregulated TFE3 expression might promote oncogenesis by preventing cell cycle arrest. (Figure 5) TFE3 protein is known to interact with the Rb target, E2F3, causing synergistic activation of E2F target genes and allowing escape from Rb-induced cell cycle arrest.98 The ability of TFE3 to block the anti-mitogenic effects of TGFβ has been suggested to result from TGFβ signaling dependence on the downstream Rb protein product.98 Potential upregulation of cyclin proteins by TFE3 may promote cell cycle progression.98,99 Furthermore, at least one type of TFE3-fusion protein (SFPQ-TFE3) can interact with p53, a key cell cycle regulator.100

6.4 TFE and Met Tyrosine Kinase Regulation

Upregulation of the Met tyrosine kinase, an oncogene frequently amplified in papillary RCC, has been suggested to mediate TFE3-fusion oncogenicity.101,102 (Figure 5) Tsuda et al showed direct activation of the Met promoter by various TFE3-fusion proteins in vitro leading to up to 3.5-fold increases in Met transcription.102 However, among clinical renal tumors with TFE3-fusions, activated (i.e., phosphorylated) Met protein was frequently undetectable in their study. Furthermore, the FU-UR1 RCC cell line harboring a ASPSCR1-TFE3 type 1 gene fusion required very high concentrations of a selective Met inhibitor (500 nM of PHA665752) for growth inhibition, ∼10 times higher than the IC50 for growth reported by Guo et al in cancer cells with Met upregulation (∼100 times higher than the IC50 for phosphorylation), but similar to the IC50 among cancer cells without Met upregulation.103 We have similarly observed no significant growth inhibition at high concentrations of selective Met inhibitors in a panel of TFE3-fusion RCC cell lines.89 Hence, Met inhibition may not be an effective mono-therapy for TFE-fusion RCC patients. Consistent with this, a recent clinical trial using the selective Met inhibitor, tivantinib, demonstrated poor progression-free survival (median 1.9 months) and no objective responses among six RCC patients with known translocations.104

6.5 Functional significance of the TFE3-fusion protein partner

An alternative mechanistic hypothesis argues that the function of the TFE3-fusion partner may have significance within the chimeric protein. This theory has been proposed by some investigators based on functional similarity among known TFE3 fusion partners. Most of these fusion partners appear to have regulatory roles in mRNA splicing and/or mitosis. Both NONO and SFPQ are pre-mRNA splicing factors, while PRCC can also be found in complexes with splicing factors.24,105 Both PRCC and CLTC are implicated in mitosis control through their direct or indirect interactions with MAD2B, a regulator of the anaphase-promoting complex. PRCC binds to MAD2B directly, while CLTC is thought to regulate MAD2B through shared interactions with the clathrin light chain component (CLTA).106,107 The similarity of functions among TFE3 fusion partners is intriguing and warrants further investigation.

7 Conclusion

Nearly two decades since the discovery of TFE3 gene fusions and one decade since the discovery of TFEB gene fusions, the mechanisms underlying the oncogenic effects of these mutations in kidneys remain largely unclear. As with other fusion proteins involving transcription factors, promoter substitution appears to be the key molecular event with TFE-fusions, causing dysregulated TFE protein activity. Yet how this dyregulation translates into cancer is unknown. It is interesting in this regard that so many signaling pathways already implicated in carcinogenesis appear to be regulated by TFE3 and TFEB, and it may be this multitude of pathways that allows a single mutation in these genes to be sufficient enough for cellular transformation. The ability of TFE3 and TFEB to regulate metabolic pathways and mTOR signaling is particularly intriguing, given the known roles of both processes in RCC tumorigenesis. Whether dysreguation of these pathways contributes to TFE-fusion carcinogenesis warrants further investigation, with an ultimate goal of pinpointing the most promising molecular targets for novel therapeutics. The advent of new and rapid genetic analysis and large scale investigative projects, such as the Cancer Genome Atlas, will identify ever increasing numbers of patients with tumors harboring gene fusions such as the TFE-fusion RCCs and thus now could be the optimal time to begin thorough investigations of targeted therapies based on the existing and forthcoming knowledge of these specific cases.

References

- 1.Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards PA. Fusion genes and chromosome translocations in the common epithelial cancers. J Pathol. 2010;220:244. doi: 10.1002/path.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, Varela I, Pleasance ED, Simpson JT, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G, Pinto PA, Schmidt LS, Neckers L, Bottaro DP, et al. Molecular diagnosis and therapy of kidney cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.042808.171650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin MB, Amin MB, Tamboli P, Javidan J, Stricker H, de-Peralta VM, et al. Prognostic impact of histologic subtyping of adult renal epithelial neoplasms: an experience of 405 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:281. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linehan WM, Ricketts CJ. The metabolic basis of kidney cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farley MN, Schmidt LS, Mester JL, Pena-Llopis S, Pavia-Jimenez A, Christie A, et al. Germline BAP1 mutation predisposes to familial clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, Huang D, Ong CK, Stephens P, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Liao A, Leng N, Pavia-Jimenez A, Wang S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:751. doi: 10.1038/ng.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Cancer Genome Working Group. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komai Y, Fujiwara M, Fujii Y, Mukai H, Yonese J, Kawakami S, et al. Adult Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma diagnosed by cytogenetics and immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1170. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosquera JM, Dal CP, Mertz KD, Perner S, Davis IJ, Fisher DE, et al. Validation of a TFE3 break-apart FISH assay for Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2011;20:129. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e31820e9c67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong M, De AP, Osborne L, Paniz-Mondolfi AE, Geller M, Yang Y, et al. Translocation renal cell carcinomas in adults: a single-institution experience. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:654. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824f24a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kauffman EC, Shuch B, Rais-Bahrami S, Yang Y, Merino MJ, Srinivasan R, et al. Clinical features of MiT family gene fusions in renal cell carcinoma and recommendations for clinical management. J Urol. 2012 in submission. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rais-Bahrami S, Drabick JJ, De Marzo AM, Hicks J, Ho C, Caroe AE, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma: delayed but massive and lethal metastases of a chemotherapy-associated secondary malignancy. Urology. 2007;70:178. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de JB, Molenaar IM, Leeuw JA, Idenberg VJ, Oosterhuis JW. Cytogenetics of a renal adenocarcinoma in a 2-year-old child. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1986;21:165. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(86)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meloni AM, Dobbs RM, Pontes JE, Sandberg AA. Translocation (X;1) in papillary renal cell carcinoma. A new cytogenetic subtype. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1993;65:1. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(93)90050-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tonk V, Wilson KS, Timmons CF, Schneider NR, Tomlinson GE. Renal cell carcinoma with translocation (X;1). Further evidence for a cytogenetically defined subtype. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;81:72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(94)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shipley JM, Birdsall S, Clark J, Crew J, Gill S, Linehan M, et al. Mapping the X chromosome breakpoint in two papillary renal cell carcinoma cell lines with a t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) and the first report of a female case. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1995;71:280. doi: 10.1159/000134127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sidhar SK, Clark J, Gill S, Hamoudi R, Crew AJ, Gwilliam R, et al. The t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) translocation in papillary renal cell carcinoma fuses a novel gene PRCC to the TFE3 transcription factor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weterman MA, Wilbrink M, Dijkhuizen T, van den Berg E, Geurts van KA. Fine mapping of the 1q21 breakpoint of the papillary renal cell carcinoma-associated (X;1) translocation. Hum Genet. 1996;98:16. doi: 10.1007/s004390050153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weterman MA, Wilbrink M, Geurts van KA. Fusion of the transcription factor TFE3 gene to a novel gene, PRCC, in t(X;1)(p11;q21)-positive papillary renal cell carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark J, Lu YJ, Sidhar SK, Parker C, Gill S, Smedley D, et al. Fusion of splicing factor genes PSF and NonO (p54nrb) to the TFE3 gene in papillary renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 1997;15:2233. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Argani P, Antonescu CR, Illei PB, Lui MY, Timmons CF, Newbury R, et al. Primary renal neoplasms with the ASPL-TFE3 gene fusion of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a distinctive tumor entity previously included among renal cell carcinomas of children and adolescents. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:179. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argani P, Lui MY, Couturier J, Bouvier R, Fournet JC, Ladanyi M. A novel CLTC-TFE3 gene fusion in pediatric renal adenocarcinoma with t(X;17)(p11.2;q23) Oncogene. 2003;22:5374. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladanyi M, Lui MY, Antonescu CR, Krause-Boehm A, Meindl A, Argani P, et al. The der(17)t(X;17)(p11;q25) of human alveolar soft part sarcoma fuses the TFE3 transcription factor gene to ASPL, a novel gene at 17q25. Oncogene. 2001;20:48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka M, Kato K, Gomi K, Matsumoto M, Kudo H, Shinkai M, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with SFPQ/PSF-TFE3 gene fusion in a patient with advanced neuroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1416. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a9cd6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argani P, Olgac S, Tickoo SK, Goldfischer M, Moch H, Chan DY, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma in adults: expanded clinical, pathologic, and genetic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1149. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318031ffff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armah HB, Parwani AV, Surti U, Bastacky SI. Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma occurring during pregnancy with a novel translocation involving chromosome 19: a case report with review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2009;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis IJ, Hsi BL, Arroyo JD, Vargas SO, Yeh YA, Motyckova G, et al. Cloning of an Alpha-TFEB fusion in renal tumors harboring the t(6;11)(p21;q13) chromosome translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931430100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiper RP, Schepens M, Thijssen J, van AM, van den Berg E, Bridge J, et al. Upregulation of the transcription factor TFEB in t(6;11)(p21;q13)-positive renal cell carcinomas due to promoter substitution. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1661. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dal CP, van GS, Brock P, Proesmans W, Casteels-van DM, de W. Renal cell carcinoma in a child. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1991;57:137. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(91)90199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takebayashi K, Chida K, Tsukamoto I, Morii E, Munakata H, Arnheiter H, et al. The recessive phenotype displayed by a dominant negative microphthalmia-associated transcription factor mutant is a result of impaired nucleation potential. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemesath TJ, Steingrimsson E, McGill G, Hansen MJ, Vaught J, Hodgkinson CA, et al. microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2770. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Argani P, Antonescu CR, Couturier J, Fournet JC, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M, et al. PRCC-TFE3 renal carcinomas: morphologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis of an entity associated with the t(X;1)(p11.2;q21) Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1553. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang IW, Huang HY, Sung MT. Melanotic Xp11 translocation renal cancer: a case with PSF-TFE3 gene fusion and up-regulation of melanogenetic transcripts. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1894. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ba7a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong M, Weisman P, Zhu B, Brassesco M, Yang Y, Linehan WM, et al. Xp11.2 Translocation Renal Cell Carcinoma With PSF-TFE3 Rearrangement. Diagn Mol pathol. 2013;22:107. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e318278962e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Argani P, Lae M, Hutchinson B, Reuter VE, Collins MH, Perentesis J, et al. Renal carcinomas with the t(6;11)(p21;q12): clinicopathologic features and demonstration of the specific alpha-TFEB gene fusion by immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR, and DNA PCR. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:230. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146007.54092.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Argani P, Lae M, Ballard ET, Amin M, Manivel C, Hutchinson B, et al. Translocation carcinomas of the kidney after chemotherapy in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pecciarini L, Cangi MG, Lo CC, Macri' E, Dal CE, Martignoni G, et al. Characterization of t(6;11)(p21;q12) in a renal-cell carcinoma of an adult patient. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:419. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhan HQ, Wang CF, Zhu XZ, Xu XL. Renal cell carcinoma with t(6;11) translocation: a patient case with a novel Alpha-TFEB fusion point. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e709. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inamura K, Fujiwara M, Togashi Y, Nomura K, Mukai H, Fujii Y, et al. Diverse fusion patterns and heterogeneous clinicopathologic features of renal cell carcinoma with t(6;11) translocation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:35. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182293ec3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferre-D'Amare AR, Prendergast GC, Ziff EB, Burley SK. Recognition by Max of its cognate DNA through a dimeric b/HLH/Z domain. Nature. 1993;363:38. doi: 10.1038/363038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beckmann H, Su LK, Kadesch T. TFE3: a helix-loop-helix protein that activates transcription through the immunoglobulin enhancer muE3 motif. Genes Dev. 1990;4:167. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roman C, Cohn L, Calame K. A dominant negative form of transcription activator mTFE3 created by differential splicing. Science. 1991;254:94. doi: 10.1126/science.1840705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu SY, Li M, Lin YL. Mitf induction by RANKL is critical for osteoclastogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1763. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGill GG, Horstmann M, Widlund HR, Du J, Motyckova G, Nishimura EK, et al. Bcl2 regulation by the melanocyte master regulator Mitf modulates lineage survival and melanoma cell viability. Cell. 2002;109:707. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takemoto CM, Yoon YJ, Fisher DE. The identification and functional characterization of a novel mast cell isoform of the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shibahara S, Takeda K, Yasumoto K, Udono T, Watanabe K, Saito H, et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF): multiplicity in structure, function, and regulation. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001;6:99. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yasumoto K, Amae S, Udono T, Fuse N, Takeda K, Shibahara S. A big gene linked to small eyes encodes multiple Mitf isoforms: many promoters make light work. Pigment Cell Res. 1998;11:329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1998.tb00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao GQ, Zhao Q, Zhou X, Mattei MG, de CB. TFEC, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, forms heterodimers with TFE3 and inhibits TFE3-dependent transcription activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steingrimsson E, Moore KJ, Lamoreux ML, Ferre-D'Amare AR, Burley SK, Zimring DC, et al. Molecular basis of mouse microphthalmia (mi) mutations helps explain their developmental and phenotypic consequences. Nat Genet. 1994;8:256. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes AE, Newton VE, Liu XZ, Read AP. A gene for Waardenburg syndrome type 2 maps close to the human homologue of the microphthalmia gene at chromosome 3p12-p14.1. Nat Genet. 1994;7:509. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore KJ. Insight into the microphthalmia gene. Trends Genet. 1995;11:442. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price ER, Fisher DE. Sensorineural deafness and pigmentation genes: melanocytes and the Mitf transcriptional network. Neuron. 2001;30:15. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tachibana M. Evidence to suggest that expression of MITF induces melanocyte differentiation and haploinsufficiency of MITF causes Waardenburg syndrome type 2A. Pigment Cell Res. 1997;10:25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1997.tb00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tassabehji M, Newton VE, Read AP. Waardenburg syndrome type 2 caused by mutations in the human microphthalmia (MITF) gene. Nat Genet. 1994;8:251. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verastegui C, Bertolotto C, Bille K, Abbe P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R. TFE3, a transcription factor homologous to microphthalmia, is a potential transcriptional activator of tyrosinase and TyrpI genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:449. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Widlund HR, Fisher DE. Microphthalamia-associated transcription factor: a critical regulator of pigment cell development and survival. Oncogene. 2003;22:3035. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yasumoto K, Takeda K, Saito H, Watanabe K, Takahashi K, Shibahara S. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor interacts with LEF-1, a mediator of Wnt signaling. EMBO J. 2002;21:2703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Motyckova G, Weilbaecher KN, Horstmann M, Rieman DJ, Fisher DZ, Fisher DE. Linking osteopetrosis and pycnodysostosis: regulation of cathepsin K expression by the microphthalmia transcription factor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091479298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steingrimsson E, Tessarollo L, Pathak B, Hou L, Arnheiter H, Copeland NG, et al. Mitf and Tfe3, two members of the Mitf-Tfe family of bHLH-Zip transcription factors, have important but functionally redundant roles in osteoclast development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072071099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merrell K, Wells S, Henderson A, Gorman J, Alt F, Stall A, et al. The absence of the transcription activator TFE3 impairs activation of B cells in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3335. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zanocco-Marani T, Vignudelli T, Parenti S, Gemelli C, Condorelli F, Martello A, et al. TFE3 transcription factor regulates the expression of MAFB during macrophage differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1798. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yagil Z, Hadad ET, Ofir-Birin Y, Tshori S, Kay G, Yekhtin Z, et al. Transcription factor E3, a major regulator of mast cell-mediated allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weilbaecher KN, Motyckova G, Huber WE, Takemoto CM, Hemesath TJ, Xu Y, et al. Linkage of M-CSF signaling to Mitf, TFE3, and the osteoclast defect in Mitf(mi/mi) mice. Mol Cell. 2001;8:749. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mansky KC, Marfatia K, Purdom GH, Luchin A, Hume DA, Ostrowski MC. The microphthalmia transcription factor (MITF) contains two N-terminal domains required for transactivation of osteoclast target promoters and rescue of mi mutant osteoclasts. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luchin A, Purdom G, Murphy K, Clark MY, Angel N, Cassady AI, et al. The microphthalmia transcription factor regulates expression of the tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase gene during terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:451. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.So H, Rho J, Jeong D, Park R, Fisher DE, Ostrowski MC, et al. Microphthalmia transcription factor and PU.1 synergistically induce the leukocyte receptor osteoclast-associated receptor gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meadows NA, Sharma SM, Faulkner GJ, Ostrowski MC, Hume DA, Cassady AI. The expression of Clcn7 and Ostm1 in osteoclasts is coregulated by microphthalmia transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis IJ, Kim JJ, Ozsolak F, Widlund HR, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Granter SR, et al. Oncogenic MITF dysregulation in clear cell sarcoma: defining the MiT family of human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:473. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huan C, Sashital D, Hailemariam T, Kelly ML, Roman CA. Renal carcinoma-associated transcription factors TFE3 and TFEB are leukemia inhibitory factor-responsive transcription activators of E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weterman MA, van Groningen JJ, den HA, Geurts van KA. Transformation capacities of the papillary renal cell carcinoma-associated PRCCTFE3 and TFE3PRCC fusion genes. Oncogene. 2001;20:1414. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P, Shukla N, McGill GG, Nagai M, et al. TFE3 fusions activate MET signaling by transcriptional up-regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:919. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weterman MJ, van Groningen JJ, Jansen A, van Kessel AG. Nuclear localization and transactivating capacities of the papillary renal cell carcinoma-associated TFE3 and PRCC (fusion) proteins. Oncogene. 2000;19:69. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Schwartz JC, Wolff NC, Tran TA, Zou L, et al. Regulation of TFEB and V-ATPases by mTORC1. EMBO J. 2011;30:3242. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cronin JC, Wunderlich J, Loftus SK, Prickett TD, Wei X, Ridd K, et al. Frequent mutations in the MITF pathway in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:435. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ugurel S, Houben R, Schrama D, Voigt H, Zapatka M, Schadendorf D, et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor gene amplification in metastatic melanoma is a prognostic marker for patient survival, but not a predictive marker for chemosensitivity and chemotherapy response. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6344. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bertolotto C, Lesueur F, Giuliano S, Strub T, de LM, Bille K, et al. A SUMOylation-defective MITF germline mutation predisposes to melanoma and renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;480:94. doi: 10.1038/nature10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mir MC, Trilla E, de Torres IM, Panizo A, Zlotta AR, Van RB, et al. Altered transcription factor E3 expression in unclassified adult renal cell carcinoma indicates adverse pathological features and poor outcome. BJU Int. 2011;108:E71. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Macher-Goeppinger S, Roth W, Wagener N, Hohenfellner M, Penzel R, Haferkamp A, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of TFE3 activation in renal cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:308. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hua X, Liu X, Ansari DO, Lodish HF. Synergistic cooperation of TFE3 and smad proteins in TGF-beta-induced transcription of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3084. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hua X, Miller ZA, Wu G, Shi Y, Lodish HF. Specificity in transforming growth factor beta-induced transcription of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene: interactions of promoter DNA, transcription factor muE3, and Smad proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tian G, Erman B, Ishii H, Gangopadhyay SS, Sen R. Transcriptional activation by ETS and leucine zipper-containing basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2946. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huan C, Kelly ML, Steele R, Shapira I, Gottesman SR, Roman CA. Transcription factors TFE3 and TFEB are critical for CD40 ligand expression and thymus-dependent humoral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1082. doi: 10.1038/ni1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Argani P, Hicks J, De Marzo AM, Albadine R, Illei PB, Ladanyi M, et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma (RCC): extended immunohistochemical profile emphasizing novel RCC markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1295. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e8ce5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kauffman EC, Gupta G, Cecchi F, Raffensperger K, Linehan WM, Bottaro DP, et al. Characterization of the Akt-mTOR Pathway in TFE3-Fusion Renal Cell Cancer and Implications for Targeted Therapy. J Urol. 2012;187:e183. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Malouf GG, Camparo P, Oudard S, Schleiermacher G, Theodore C, Rustine A, et al. Targeted agents in metastatic Xp11 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion renal cell carcinoma (RCC): a report from the Juvenile RCC Network. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1834. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Choueiri TK, Lim ZD, Hirsch MS, Tamboli P, Jonasch E, McDermott DF, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy for the treatment of adult metastatic Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:5219. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:277. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iwasaki H, Naka A, Iida KT, Nakagawa Y, Matsuzaka T, Ishii KA, et al. TFE3 regulates muscle metabolic gene expression, increases glycogen stores, and enhances insulin sensitivity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E896. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00204.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Yoshikawa T, Ide T, Tamura M, Furusawa M, et al. TFE3 transcriptionally activates hepatic IRS-2, participates in insulin signaling and ameliorates diabetes. Nat Med. 2006;12:107. doi: 10.1038/nm1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hong SB, Oh H, Valera VA, Baba M, Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Inactivation of the FLCN tumor suppressor gene induces TFE3 transcriptional activity by increasing its nuclear localization. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di RA, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325:473. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Settembre C, Di MC, Polito VA, Garcia AM, Vetrini F, Erdin S, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nijman SM, Hijmans EM, El MS, van Dongen MM, Sardet C, Bernards R. A functional genetic screen identifies TFE3 as a gene that confers resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of the retinoblastoma protein and transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Muller-Hocker J, Babaryka G, Schmid I, Jung A. Overexpression of cyclin D1, D3, and p21 in an infantile renal carcinoma with Xp11.2 TFE3-gene fusion. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:589. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mathur M, Das S, Samuels HH. PSF-TFE3 oncoprotein in papillary renal cell carcinoma inactivates TFE3 and p53 through cytoplasmic sequestration. Oncogene. 2003;22:5031. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schmidt L, Duh FM, Chen F, Kishida T, Glenn G, Choyke P, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P, Shukla N, McGill GG, Nagai M, et al. TFE3 fusions activate MET signaling by transcriptional up-regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:919. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guo T, Zhu Y, Gan CS, Lee SS, Zhu J, Wang H, et al. Quantitative proteomics discloses MET expression in mitochondria as a direct target of MET kinase inhibitor in cancer cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2629. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wagner AJ, Goldberg JM, Dubois SG, Choy E, Rosen L, Pappo A, et al. Tivantinib (ARQ 197), a selective inhibitor of MET, in patients with microphthalmia transcription factor-associated tumors: Results of a multicenter phase 2 trial. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Skalsky YM, Ajuh PM, Parker C, Lamond AI, Goodwin G, Cooper CS. PRCC, the commonest TFE3 fusion partner in papillary renal carcinoma is associated with pre-mRNA splicing factors. Oncogene. 2001;20:178. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Medendorp K, Vreede L, van Groningen JJ, Hetterschijt L, Brugmans L, Jansen PA, et al. The mitotic arrest deficient protein MAD2B interacts with the clathrin light chain A during mitosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weterman MA, van Groningen JJ, Tertoolen L, van Kessel AG. Impairment of MAD2B-PRCC interaction in mitotic checkpoint defective t(X;1)-positive renal cell carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241304198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]