Abstract

Racial disparities in cognitive outcomes may be partly explained by differences in locus of control. African Americans report more external locus of control than non-Hispanic Whites, and external locus of control is associated with poorer health and cognition. The aims of this study were to compare cognitive training gains between African American and non-Hispanic White participants in the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study and determine whether racial differences in training gains are mediated by locus of control. The sample comprised 2,062 (26% African American) adults aged 65 and older who participated in memory, reasoning, or speed training. Latent growth curve models evaluated predictors of 10-year cognitive trajectories separately by training group. Multiple group modeling examined associations between training gains and locus of control across racial groups. Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans evidenced less improvement in memory and reasoning performance after training. These effects were partially mediated by locus of control, controlling for age, sex, education, health, depression, testing site, and initial cognitive ability. African Americans reported more external locus of control, which was associated with smaller training gains. External locus of control also had a stronger negative association with reasoning training gain for African Americans than for Whites. No racial difference in training gain was identified for speed training. Future intervention research with African Americans should test whether explicitly targeting external locus of control leads to greater cognitive improvement following cognitive training.

Keywords: Older adults, race, cognition, cognitive training, locus of control

Racial/ethnic minority older adults are at greater risk of developing cognitive impairments and Alzheimer’s disease than non-Hispanic Whites (Glymour, Weuve, & Chen, 2008; Sloan & Wang, 2005; Tang et al., 2001). Further, cognitive impairment is more severe when Alzheimer’s disease is recognized in African Americans, even after controlling for duration of dementia symptoms (Shadlen, Larson, Gibbons, McCormick, & Teri, 1999). In the absence of dementia, African Americans still tend to score lower on standardized tests of cognition compared to non-Hispanic Whites (Carlson, Brandt, Carol, & Kawas, 1998; Herzog & Wallace, 1997; Manly et al., 1998; Schwartz et al., 2004; Zsembik & Peek, 2001). These disparities have been attributed to a variety of factors, including cognitive test bias and racial differences in background variables such as educational attainment, educational quality, income, and health (Aiken Morgan et al., 2010; Jones, 2003; Manly, 2002). In addition, locus of control may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in cognitive health. Unlike other factors (e.g., educational attainment and quality), locus of control may be modifiable in late life (Lachman, 2006). Thus, locus of control may represent a potential target for promoting cognitive health (and reducing disparities) in older racial/ethnic minorities.

The extent to which an individual perceives personal power and direction over outcomes in life is a function of both internal and external locus of control. Internal locus of control is the perception that skills and capabilities can be used to control one’s destiny; conversely, external locus of control is the perception of environmental constraints such as fate and the existence of powerful others (Lachman, 2006). Locus of control has important consequences for behavior and health. Several studies have demonstrated positive associations between stronger internal locus of control and better cognitive and physical health outcomes, as well as reduced risk of mortality (Infurna, Gerstorf, Ram, & Schupp, 2011; Lachman 2006; Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011; Surtees et al., 2010; West & Yassuda, 2004). Conversely, higher external locus of control is a risk factor for a variety of negative health outcomes (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). This relationship between external locus of control and health outcomes reflects, in part, less engagement in positive health behaviors among individuals who perceive that they have little control over their own circumstances (Lachman & Firth, 2004), including behaviors that promote cognitive health in later life. For example, it is possible that external locus of control leads to reduced expectations in a cognitive intervention.

On average, older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, and those with lower educational attainment report higher external locus of control (Caplan & Schooler, 2003; Fiori, Brown, Cortina, & Antonucci, 2006; Kennedy, Allaire, Gamaldo, & Whitfield, 2012; Lachman et al., 2011; Mirowsky, Ross, & Van Willigen, 1996; Schieman, 2001; Shaw & Krause, 2001). Social and economic constraints and/or negative environmental messages likely influence locus of control (Shaw & Krause, 2001) and may help to explain why African Americans report higher external locus of control than non-Hispanic Whites. Cumulative advantage and disadvantage (CAD) theory posits that African Americans face disadvantages related to discrimination and segregation that accumulate throughout their lifetimes (Crystal & Shea, 1990; O’Rand & Henretta, 1999). These accumulated disadvantages manifest in racial disparities related to education (Glymour, Kawachi, Jencks & Berkman, 2008), economic conditions (Crystal & Shea, 1990; Mirowsky & Ross, 2007), career patterns (Brown, 2009), health and health care (Warner & Hayward, 2006), and stress (Oliver & Shapiro, 2006). As CAD claims that inequality increases as an individual ages (Dannefer & Settersten, 2010; O’Rand, 1996), older African Americans may be more severely affected, potentially making them more prone to external locus of control and vulnerable to cognitive health disparities. Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence supports a late-life elevation in the belief that powerful others are responsible for life events (Lachman, 1986; Lachman & Leff, 1989).

To date, the cognitive training literature in older adults has largely considered race as a covariate without examining racial differences in training gains. For example, the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study included a substantial proportion of racial/ethnic minority older adults, and previous reports have described racial differences in initial cognitive levels and 5-year cognitive declines in untrained participants (Marsiske et al., 2013) and confirmed the absence of substantive race-related cognitive test bias (Aiken Morgan et al., 2010). However, no study has focused on differential benefits of the memory, reasoning, and speed interventions by race/ethnicity in ACTIVE (Aiken Morgan et al., 2008; Ball et al., 2002; Ball, Ross, Roth & Edwards, 2013; Marsiske et al., 2013; Rebok et al., 2013; Willis et al., 2006; Willis & Caskie, 2013). Among ACTIVE participants in the memory training group, African Americans showed a steeper decline in the use of inappropriate memory strategies compared to Whites, but Whites showed less decline in initial recall in the years following training than African Americans (Gross & Rebok, 2011; Gross et al., 2013).

Among the few studies that have examined racial differences in training gains, the SeniorWISE (Wisdom is Simply Exploration) randomized clinical trial examined the effects of memory training on cognitive, functional, and psychosocial outcomes. This study found that irrespective of training condition, African Americans improved more than Whites on visual memory measures at the end of the study (McDougall, Becker, Pituch, Acee, Vaughan, & Delville, 2010). However, this study was limited by a relatively small sample of African American older adults (N = 30) and lack of a no-treatment control condition. Additionally, McDougall et al. (2010) did not find an overall effect of memory training compared to a health-promotion training condition.

The ACTIVE study is the largest randomized controlled trial of a cognitive intervention among older adults to date (Jobe et al., 2001). By design, older adults (over age 65 years) were randomized to one of three training conditions (reasoning, speed, and memory) or to a no-contact control condition (Ball et al., 2002; Jobe et al., 2001). All three interventions were effective in increasing cognitive performance immediately, and beneficial effects remained over a period of 10 years (Rebok et al., 2014). In addition to cognitive benefits, cognitive interventions may also promote internal locus of control. For instance, Wolinsky and colleagues (2010) showed that internal locus of control was enhanced for the ACTIVE reasoning and speed intervention groups at five-year follow-up. Although training influences locus of control, other studies have suggested that the reverse may also be true (i.e., locus of control influences training gains; Caplan & Schooler, 2003; Neupert & Allaire, 2012). Individuals with low internal locus of control and/or high external locus of control may be less likely to believe that their participation in a cognitive intervention will actually improve their cognition, which could result in smaller training gains. Unfortunately, very few studies have examined these associations among racial/ethnic minorities.

The Present Study

We extend the current literature on racial/ethnic differences in cognitive training benefits and control beliefs by examining the following aims: (1) compare training gains between African American and non-Hispanic White participants in ACTIVE; (2) determine whether racial differences in training gains are mediated by locus of control when controlling for age, sex, education, health, depression, testing site, and baseline cognitive performance; (3) identify specific aspects of locus of control accounting for results: internal (i.e., belief in one’s intellectual competence) or external (i.e., belief that cognitive ability is due to chance, belief that outside assistance is needed to complete cognitive tasks); and (4) explore whether relationships between training gain and internal or external locus of control differ across race.

As summarized above, previous literature on racial differences in cognitive performance and locus of control indicates that African American older adults obtain lower scores on neuropsychological tests and measures of locus of control than non-Hispanic Whites. Based on these findings, we predicted that African American participants in ACTIVE would evidence smaller training gains than non-Hispanic Whites. We also predicted that these racial differences would be mediated by locus of control such that African Americans would report low internal locus of control and high external locus of control, and these beliefs would be associated with smaller training gains. Finally, we hypothesized that locus of control would be more strongly related to cognitive training gains among African Americans than non-Hispanic Whites based on evidence that membership in the majority group is associated with social and environmental advantages (Rothenberg, 2004) that could trump the impact of individual differences in locus of control on cognitive outcomes among non-Hispanic Whites. In other words, social and environmental advantages unavailable to African Americans may allow non-Hispanic Whites to benefit from cognitive training irrespective of locus of control.

Method

Data

This study used seven waves of the ACTIVE study (1998–2010), a single-blind, randomized controlled trial of three cognitive interventions: memory, reasoning, and speed. Detailed descriptions on the ACTIVE study design, recruitment strategies, and measures have been published elsewhere (Jobe et al., 2001; Willis et al., 2006). Briefly, participants included independent, community-dwelling people aged 65 or older who were geographically and racially diverse. Data were collected from six different sites across nation: the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Indiana University in Indianapolis, Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged in Boston, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Wayne State University in Detroit, and Pennsylvania State University in Philadelphia. Individuals were excluded from ACTIVE if they demonstrated: (1) cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental Status Exam [MMSE] score less than 23); (2) poor vision (less than 20/50); (3) disability in dressing, bathing, or hygiene; (4) Alzheimer’s disease; (5) history of stroke in the past 12 months; (6) diagnosed cancer; (7) current chemotherapy or radiation treatment; or (8) communication problems. Eligible participants (N= 2,802) were administered a baseline assessment, which included several cognitive, health, and function measures and randomly assigned to one of three different cognitive interventions (memory, reasoning, and speed) or a no-contact control group. Follow-up assessments were administered immediately after the 10-week training session, and at years 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 post-intervention. The study protocol was approved by participating institutions’ Institutional Review Boards, including written informed consent.

Participants in all three training groups received training according to standardized procedures across 10 sessions over five to six weeks. Training was carried out in small group settings with individual and group exercises by certified trainers. The memory training program focused on using strategies to remember information. Memory strategies taught to the participants included categorization, visualization, method of loci, and mnemonics. The reasoning training program focused on improving the ability to solve problems that follow a serial pattern or sequence. Reasoning strategies taught to the participants included underlining repeating elements, making slashes between elements, and indicating skipped elements with tick marks. Exercises involved both abstract and more concrete (e.g., identifying medication dosing patterns) problems. The speed training program focused on enhancing mental processing speed for increasingly more complex information over briefer periods of time. Speed training primarily involved computerized adaptive practice, though some strategies were taught by the trainer.

For the purposes of the present analysis, this study only analyzed non-Hispanic White (N = 1,525) and African American (N = 537) participants from the three intervention subgroups and excluded those from the control group, reducing the sample size to 2,062. Control participants were excluded because the goals of the present study related to individual differences in training gains among participants who underwent training, and the efficacy of all three ACTIVE interventions compared to the control condition has already been established (Ball et al., 2002; Rebok et al., 2014; Willis et al., 2006). This approach does not separately quantify re-test effects.

Measures

Factor scores for memory, reasoning, and speed of processing were generated from confirmatory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors using the regression method. The following measures were included in the factor scores.

Memory

Participants’ verbal memory was assessed by three measures: Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test (AVLT), Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT), and the Paragraph Recall Test from the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test (RVMT) (Brandt, 1991; Brandt & Benedict, 2001; Schmidt, 2004; Wilson, Cockburn, & Baddeley, 1985). Higher memory factor scores reflect better performance.

Reasoning

Participants’ reasoning ability was assessed with three inductive reasoning tests: Word Series (6-minutes, 10-item; Gonda & Schaie, 1985), Letter Series (6-minutes, 15-item; Thurstone & Thurstone, 1949), and Letter Sets (7 minutes; 15-item; Ekstrom, French, Harman, & Derman, 1976). Word Series asks participants to identify a pattern in a series of words (e.g., month or day of the week) and circle the word that comes next in the series. Letter Series requires participants to identify a pattern in a series of letters and circle the letter that comes next in the series. Letter sets requires participants to identify which set of letters out of four letter sets does not follow a pattern. Higher reasoning factor scores reflect better performance.

Speed

Participants’ speed of processing was assessed with three tasks from the Useful Field of View (UFOV) (Ball et al., 1988; Owsley et al., 1991; Owsley et al., 1998). These tasks measure the minimum time that participants need to identify and locate information. The UFOV begins with an easier task (simply identifying objects on a computer touch screen) and then adds more complex tasks (e.g., simultaneously judging where a peripheral target locates). Second, third, and fourth trials were used in the present study. Higher speed factor scores reflect worse performance.

Locus of control

Locus of control involves two dimensions—internal and external – that were originally viewed as existing on a single continuum (Rotter, 1966). More recently, internal and external dimensions have been shown to be relatively independent (Levenson, 1981; Parkes, 1985). In the present study, locus of control was examined both as a unified construct (Aim 2) and as separate internal and external dimensions (Aim 3). It was measured by three shortened subscales (6 items each) from the shortened version (36 items) of the Personality in Intellectual Aging Contexts (PIC) Inventory Control Scales (72 items), which measures individuals’ views of their own intellectual capabilities (Lachman, Baltes, Nesselroade, & Willis, 1982). Responses were made on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). Alpha coefficients for the individual 12-item PIC subscales range from 0.76 to 0.91 (Lachman et al., 1982). Alpha coefficients for the individual 6-item PIC subscales used in the present sample ranged from 0.62 to 0.79. Previous exploratory factor analytic work in the ACTIVE sample further confirmed the reliability of these subscales, as indicated by simple factor structures for each scale and minimum standardized factor loadings greater than or equal to 0.50 (Wolinsky et al., 2010).

The first subscale (Internal) evaluates individuals’ belief that they have control over their intellectual competence and that they are able to maintain or improve their intellectual ability over the course of their life (Lachman, 1986). Higher scores reflect higher internal locus of control. This subscale includes six items (e.g., “There would be ways for me to learn how to fill out a tax form if I really wanted to” and “If I want to and work at it, I’m able to figure out quite a few puzzles and similar problems”).

The external dimension of locus of control was measured with two subscales (Chance and Powerful Others), which reflect individuals’ belief that the environment or others are responsible for what happens in their lives. The Chance subscale includes six items (e.g., “I can’t expect to be good at remembering zip codes at my age” and “There’s nothing I can do to preserve my mental clarity”). The Powerful Others subscale also includes six items (e.g., “I wouldn’t be able to figure out postal rates on a package without the postman’s help” and “I would have to ask a sales person to figure out how much I’d save with a 20% discount”). Higher scores on the Chance and Powerful Others subscales reflect higher external locus of control (Kennedy et al., 2012). All three subscales of the shortened PIC have been tested and used in previous research (Lachman, 1983; Willis & Jay, 1989; Willis, Jay, Diehl, & Marsiske, 1992).

Initial analyses included a composite score for locus of control that was derived from the three subscales described above (Kennedy et al., 2012). Composite scores were computed by averaging the three subscale scores. Scores on Chance and Powerful Others were reverse-coded prior to averaging so that higher scores on the locus of control composite correspond to higher internal and lower external locus of control. Subsequent analyses examined internal and external locus of control as separate subscales simultaneously (Levenson, 1981; Parkes, 1985). In these analyses, internal locus of control was indexed with PIC – Internal, where higher scores correspond to higher internal locus of control. External locus of control was indexed by a composite score computed by averaging scores on PIC – Chance and PIC – Powerful Others, where higher scores correspond to higher external locus of control.

Covariates

In addition to examining race effects, the models controlled for demographic variables (age, sex, and years of education), number of chronic health conditions, depressive symptoms, testing site, and baseline performance in the respective cognitive domain. Testing site was dummy-coded into five variables, and the site with the most participants (i.e., Penn State) was the reference. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale, which includes 12 items ranging from 0 to 3 (Radloff, 1977). Higher values indicate higher levels of depressive symptomatology. Chronic health conditions were quantified as the total number of the following conditions, as determined via self-report at baseline: diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, heart disease, and congestive heart failure. Scores range from 0 to 5, and higher values indicate worse health. Continuous covariates were centered at the sample means (see Table 1) to facilitate parameter interpretation.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline, Mean (SD)

| Combined (N=2,062) | African American (N=537) | Non-Hispanic White (N=1,525) | Cohen’s d or phi | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.5 (5.8) | 71.8 (5.1) | 74.0 (5.9) | .4 | <.001 |

| Female (N; %) | 1584; 76.8 | 449; 83.6 | 1,135; 74.4 | .1 | <.001 |

| Education | 13.6 (2.7) | 13.0 (2.8) | 13.8 (2.7) | .3 | <.001 |

| Site (N; %) | .5 | <.001 | |||

| Alabama | 353; 17.1 | 26; 4.8 | 327; 21.4 | - | - |

| Indiana | 361; 17.5 | 147; 27.3 | 214; 14.0 | - | - |

| HRCA | 288; 14.0 | 15; 2.8 | 273; 17.9 | - | - |

| Johns Hopkins | 339; 16.4 | 109; 20.3 | 230; 15.1 | - | - |

| Wayne State | 353; 17.1 | 222; 41.3 | 131; 8.6 | - | - |

| Penn State | 368; 17.8 | 18; 3.4 | 350; 23.0 | - | - |

| Health | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.1) | .3 | <.001 |

| CES-D | 5.3 (5.3) | 5.1 (4.8) | 5.4 (5.4) | .1 | .20 |

| Locus of control composite | 23.4 (5.0) | 22.3 (4.7) | 23.8 (5.0) | .3 | <.001 |

| PIC – Internal | 30.9 (4.4) | 30.6 (4.1) | 31.0 (4.6) | .1 | .07 |

| PIC – Chance | 17.5 (7.3) | 18.7 (7.0) | 17.1 (7.4) | .2 | <.001 |

| PIC – Powerful Others | 15.1 (6.6) | 17.0 (6.7) | 14.4 (6.5) | .4 | <.001 |

| Memory | 0.0 (0.8) | −0.3 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.8) | .5 | <.001 |

| Reasoning | 0.0 (0.9) | −0.4 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.9) | .7 | <.001 |

| Speed | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.9) | −0.1 (0.9) | .2 | <.001 |

CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HRCA=Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged; PIC=Personality in Intellectual Aging Contexts Inventory Control Scales.

Analytic Approach

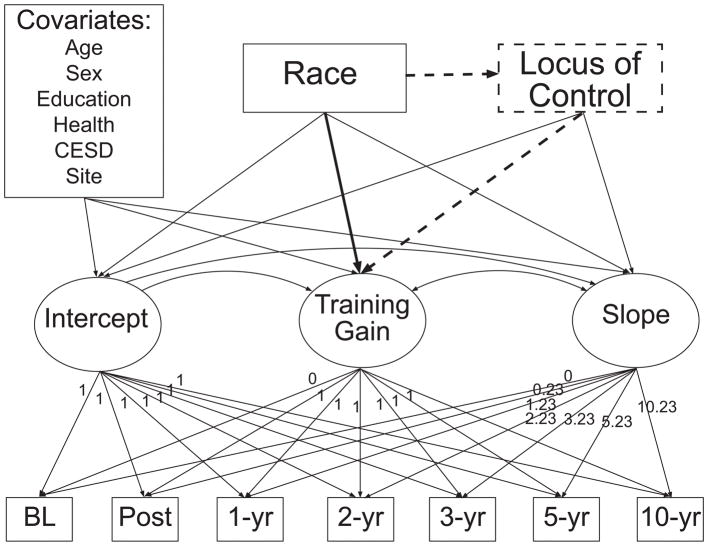

Descriptive statistics, t-tests, and χ2 tests were used to characterize the sample. Latent growth curve modeling (LGC) conducted using Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011) was used to estimate cognitive trajectories over the seven waves of data collection, representing a 10-year study period (see Figure 1). We estimated the following LGC factors: (1) initial level of cognition (i.e., intercept); (2) training gain (i.e., second intercept); and (3) rate of change in cognition following the immediate post-training wave of follow-up (i.e., slope) (Duncan, 2006). Factor loadings corresponding to these three latent factors are shown in Figure 1. Separate models were used to estimate trajectories for the three cognitive factor scores (memory, reasoning, and speed) within the corresponding intervention group. In other words, memory trajectories were modeled within the memory intervention group, reasoning trajectories were modeled within the reasoning intervention group, and speed trajectories were modeled within the speed intervention group. In all models, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to estimate parameters and account for missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987). Model fit was evaluated with the following commonly used fit indices: chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR). Both RMSEA and SRMR range from 0 to 1 with lower values indicating better fit; CFI values range from 1 to 0 with higher values indicating better fit. RMSEA close to 0.06, CFI > 0.95, and SRMR < 0.05 were used as criteria for adequate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the conditional latent growth curve model. Growth parameters (i.e., intercept, training gain, and slope) are estimated from cognitive factor scores observed at each of the seven waves (i.e., baseline, post-intervention, and one-, two-, three-, five-, and 10-year follow-ups) and regressed onto race and all covariates. Slope loadings correspond to years from baseline. Locus of control was added in subsequent mediation analyses. In mediation analyses, the direct effect of race on training gain is depicted by a heavy solid line, and the indirect effect of race on training is depicted by heavy dashed lines. CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

To evaluate whether race influenced training gain (Aim 1), the three growth parameters (i.e., intercept, training gain, and slope) were regressed onto a binary indicator for race and all covariates. To determine whether locus of control mediated any identified relationships between race and training gain (Aim 2), the locus of control composite was added to these models. As shown in Figure 1, the three growth parameters (i.e., intercept, training gain, and slope) were regressed onto the locus of control composite, and the locus of control composite was regressed onto race. This initial model estimated both direct and indirect (through locus of control) effects of race on training gain. Where appropriate, we determined whether mediation was partial versus full by examining chi square difference tests comparing models with both indirect and direct effects to models with just indirect effects. A non-significant change in model fit between these models was interpreted as evidence of full mediation.

For domains evidencing racial differences in training gain, subsequent models tested whether such racial differences were mediated by internal or external locus of control (Aim 3). Specifically, the locus of control composite from the best-fitting model identified through Aim 2 was replaced by two variables: internal locus of control (i.e., PIC – Internal) and external locus of control (i.e., a composite score of PIC – Chance and PIC – Powerful Others). These analyses determined which aspect of locus of control was an independent mediator of racial differences in training gains.

Next, multiple-group LGC models tested whether the strength of relationships between training gain and internal or external locus of control were moderated by race (Aim 4). Using multiple group models, we compared fit between models in which (1) all regression paths were forced to be equivalent in African American and non-Hispanic White groups versus (2) regression paths between training gain and internal (i.e., PIC – Internal) or external (i.e., a composite score of PIC – Chance and PIC – Powerful Others) locus of control was allowed to vary across racial groups. Significant improvement in model fit upon freeing a regression path was interpreted as evidence for a racial difference in the strength of the relationship between training gain and that specific aspect of locus of control. Note that intercepts of the growth parameters, residual variances, and covariances were not forced to equivalence in any of the multiple group models. Subsequent models were stratified by race to obtain group-specific parameter estimates. All models controlled for age, sex, years of education, chronic health conditions, depressive symptoms, testing site, and baseline performance in the respective cognitive domain (i.e., intercept).

Results

Intervention Group and Racial Differences at Baseline

Consistent with randomization at baseline, the three intervention groups did not differ in age (p=0.81), sex (p=1.00), racial composition (p=0.48), educational attainment (p=0.46), site (p=1.00), self-reported depressive symptoms (p=0.49), or locus of control (Composite: p=0.90; Internal: p=0.69; Chance: p=1.00; Powerful Others: p=0.84). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics by race, collapsing across the three intervention groups. As shown, African American participants were significantly younger, were more likely to be female, had lower educational attainment, and reported more chronic health conditions compared to non-Hispanic Whites. There were also significant differences in study site by race. The Wayne State (41.3%) and Indiana (27.4%) sites had the largest proportions of African American participants, while the HRCA (2.8%) and Penn State (3.4%) sites had the smallest proportions. African Americans obtained lower scores on the locus of control composite. Specifically, African Americans reported higher external locus of control (i.e., beliefs that cognitive ability was due to chance and that outside assistance was needed to complete cognitive tasks) than non-Hispanic Whites. There were no racial differences in depressive symptoms or internal locus of control. Finally, African Americans obtained lower scores in all cognitive domains (memory, reasoning, and speed) at baseline.

Aim 1: Racial Differences in Training Gains

Separate latent growth curve models (see Figure 1) were run for each of the three training groups. Standardized results (betas) are presented in Table 2. Significant racial differences were only identified for training gains in memory (β=−0.182) and reasoning (β=−0.192). Specifically, African American participants in the memory and the reasoning training groups evidenced smaller gains in memory and reasoning, respectively, than non-Hispanic Whites. A reference level participant – that is, a 74-year-old non-Hispanic White man with 13 years of education, one chronic health condition, and a baseline CES-D score of 5 (mean score for CES-D) recruited from the Penn State site – had an expected memory training gain of 0.287 points and an expected reasoning training gain of 0.833 points. In contrast, a comparable African American participant – that is, a 74-year-old African American man with 13 years of education, one chronic health condition, and a baseline CES-D of 5 recruited from the Penn State site – had an expected memory training gain of 0.123 points and an expected reasoning training gain of 0.668 points. Training gain was not significantly related to race in the speed training group.

Table 2.

Latent Growth Curve Model Standardized Regression Estimates (Betas) and Standard Errors for Three Intervention Groups

| Model 1: Memory (N=693) | Model 2: Reasoning (N=682) | Model 3: Speed (N=687) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||

| Age | −0.316 (0.034)** | −0.329 (0.030)** | 0.397 (0.034)** |

| Female | 0.238 (0.034)** | 0.021 (0.031) | −0.034 (0.036) |

| African American | −0.246 (0.040)** | −0.350 (0.034)** | 0.161 (0.041)** |

| Education | 0.248 (0.035)** | 0.366 (0.031)** | −0.124 (0.038)* |

| Health | −0.013 (0.033) | −0.031 (0.030) | −0.015 (0.035) |

| CES-D | −0.115 (0.034)* | −0.081 (0.030)* | 0.061 (0.036) |

| Training Gain | |||

| Intercept | −0.427 (0.053)** | −0.205 (0.056)** | −0.668 (0.033)** |

| Age | −0.246 (0.052)** | −0.190 (0.050)** | 0.246 (0.042)** |

| Female | −0.016 (0.051) | 0.067 (0.045) | −0.017 (0.037) |

| African American | −0.182 (0.058)* | −0.192 (0.056)* | 0.072 (0.043) |

| Education | 0.109 (0.053)* | 0.060 (0.052) | 0.050 (0.040) |

| Health | −0.061 (0.047) | 0.020 (0.045) | 0.022 (0.037) |

| CES-D | −0.150 (0.049)* | −0.113 (0.045)* | 0.022 (0.037) |

| Slope | |||

| Intercept | 0.210 (0.115) | 0.208 (0.102)* | 0.270 (0.106)* |

| Age | −0.547 (0.120)** | −0.420 (0.097)** | 0.193 (0.121)* |

| Female | −0.071 (0.101) | 0.059 (0.080) | −0.046 (0.096) |

| African American | −0.050 (0.115) | 0.043 (0.103) | 0.001 (0.106) |

| Education | 0.099 (0.106) | −0.051 (0.093) | −0.153 (0.104) |

| Health | −0.083 (0.091) | −0.106 (0.082) | 0.103 (0.094) |

| CES-D | 0.086 (0.104) | −0.094 (0.084) | −0.021 (0.093) |

|

| |||

| Model Fit | |||

| RMSEA | 0.045 | 0.059 | 0.041 |

| CFI | 0.977 | 0.974 | 0.970 |

| SRMR | 0.022 | 0.015 | 0.022 |

Note. For space, regression estimates for the five dummy-coded variables reflecting recruitment site are not shown. CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; RMSEA=Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; SRMR=Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

p<.05

p<.001

Aim 2: Does Locus of Control Mediate Racial Differences in Training Gain?

The locus of control composite was added to the memory and reasoning models presented in Table 2. As shown in Figure 1, the three growth parameters (i.e., intercept, training gain, and slope) were regressed onto locus of control, and locus of control was regressed onto race in both models. These models, allowing both direct and indirect (through locus of control) effects of race on training gains fit well (Memory: RMSEA=0.062; CFI=0.934; SRMR=0.048; Reasoning: RMSEA=0.064; CFI=0.952; SRMR=0.041).

The direct effects of race on memory and reasoning training gains were attenuated when locus of control was added to the models (Memory: β=−0.162; SE=0.055; p=0.003; Reasoning: β=−0.167; SE=0.057; p=0.003). There was also evidence for indirect effects of race (through locus of control) on memory and reasoning training gains. Independent of the covariates, African Americans in memory and reasoning training groups reported lower baseline scores on the locus of control composite (Memory: β=−0.109; SE=0.034; p=0.001; Reasoning: β=−0.142; SE=0.033; p<0.001), and lower scores were independently associated with smaller training gains (Memory: β=0.133; SE=0.056; p=0.018; Reasoning: β=0.183; SE=0.052; p=0.001). With regard to covariates, higher scores on the locus of control composite were also associated with younger age (p<0.001), higher education (p<0.001), fewer chronic health conditions (p<0.01), and fewer depressive symptoms (p<0.001) in both memory and reasoning training groups. Models allowing only indirect effects of race on training gain (through locus of control) fit significantly worse than models allowing both direct and indirect effects (Memory: Δχ2(1)=8.358; p=0.004; Reasoning: Δχ2(1)=80.573; p=0.003), suggesting only partial mediation.

Aim 3: Which Aspect of Locus of Control Mediates the Racial Differences in Training Gain?

Aim 2 models were repeated, replacing the locus of control composite with two variables reflecting internal (i.e., PIC – Internal) and external (i.e., PIC – Chance and PIC – Powerful Others) locus of control. Models allowing both direct and indirect (through both internal and external locus of control) effects of race on training gain fit well (Memory: RMSEA=0.060; CFI=0.938; SRMR=0.046; Reasoning: RMSEA=0.061; CFI=0.953; SRMR=0.040). The direct effects of race on training gain were attenuated when internal and external locus of control were added to the models (Memory: β=−0.168; SE=0.057; p=0.003; Reasoning: β=−0.165; SE=0.055; p=0.003).

There was clear evidence for an indirect effect of race (through external, but not internal locus of control) on reasoning training gain. African Americans in the reasoning training group reported higher scores on the external locus of control composite (β=0.160; SE=0.034; p<0.001), and higher scores on the external locus of control composite were associated with less reasoning training gain (β=−0.134; SE=0.055; p=.015). There was no racial difference in internal locus of control (β=−0.034; SE=0.037; p=.352), and internal locus of control was unrelated to reasoning training gain (β=0.079; SE=0.050; p=.111). A model allowing only indirect effects of race on training gain (through internal and external locus of control) fit significantly worse than the model allowing both direct and indirect effects (Δχ2(1)=8.765; p=0.003), suggesting only partial mediation. Together, results indicate that this partial mediation was specific to external, as opposed to internal, locus of control.

Evidence for an indirect effect of race (through external versus internal locus of control) on memory training gain was less clear. Specifically, African Americans in the memory training group reported higher scores on the external locus of control composite (β=0.113; SE=0.034; p=0.001), and there was a trend for higher scores on the external locus of control composite to be associated with less training gain (β=−0.102; SE=0.062; p=0.097). However, there was also a trend for African Americans in the memory training group to report less internal locus of control (β=−0.063; SE=0.037; p=0.092), though there was no evidence that internal locus of control was associated with memory training gain (β=0.044; SE=0.057; p=0.439). A model allowing only indirect effects of race on training gain (through internal and external locus of control) fit significantly worse than the model allowing both direct and indirect effects (Δχ2(1)=8.377; p=0.004), suggesting only partial mediation. Together, results suggest that this partial mediation was more specific to external, as opposed to internal, locus of control.

Aim 4: Racial Differences in the Strength of Associations between Training Gain and Internal or External Locus of Control

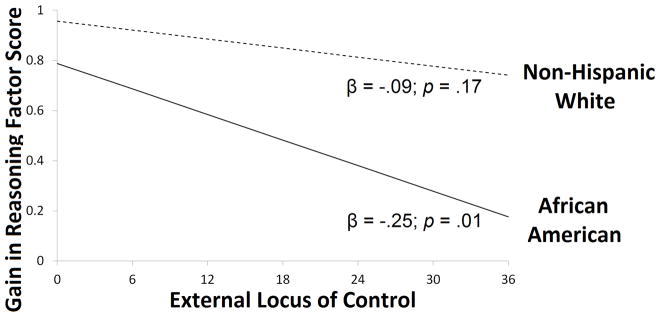

Interactions between race and locus of control were examined with separate multiple-group models for memory and reasoning groups, in which the association between training gain and internal or external locus of control was allowed to vary across African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. In the reasoning group, the multiple-group models suggested a difference in the strength of the relationship between reasoning training gain and external locus of control (Δχ2(1)= −2.872; p=0.090), but not internal locus of control (Δχ2(1)= −1.083; p=0.298). Specifically, there was a stronger negative association between training gain and external locus of control for African Americans (β=−0.254; SE=0.099; p=0.010) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (β=−0.089; SE=0.065; p=0.171), as shown in Figure 2. There was no suggestion of differences in the strength of the relationships between memory training gain and internal (Δχ2(1)= −0.533; p=0.465) or external (Δχ2(1)= −0.589; p=0.422) locus of control in the memory group.

Figure 2.

Relationship between external locus of control and reasoning training gain estimated in latent growth curve models stratified by race. External locus of control reflects a composite score of Chance and Powerful Others subscales from the Personality in Intellectual Aging Contexts (PIC). Reasoning training gain reflects change in a reasoning factor score. Depicted results control for age, sex, education, health, depressive symptoms, testing site, baseline reasoning performance, and internal locus of control.

Discussion

African American participants in ACTIVE exhibited less improvement in reasoning or memory scores following reasoning or memory intervention, respectively, compared to non-Hispanic Whites. These differences were partially mediated by locus of control such that African Americans reported lower scores on a locus of control composite, which in turn was associated with smaller training gains. These effects appeared to be driven by external locus of control (i.e., belief that cognitive ability is due to chance, belief that outside assistance is needed to complete cognitive tasks), rather than internal locus of control (i.e., belief in one’s intellectual competence). Specifically, African Americans reported significantly higher external locus of control, but not significantly lower internal locus of control, than non-Hispanic Whites. Only higher external locus of control was associated with smaller training gains. Further, having higher external locus of control had a greater negative effect on reasoning training gain for African Americans than for non-Hispanic Whites.

These results differ somewhat from those of McDougall et al. (2010), which indicated that irrespective of treatment condition, African Americans exhibited greater improvements in memory performance at the end of the study. However, unlike ACTIVE, McDougall et al. (2010) did not find an overall effect of memory training on memory performance. Specifically, memory-trained participants did not outperform participants in a health promotion training condition. In addition, the African American advantage described by McDougall et al. (2010) was specific to visual memory, as assessed by the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test. African Americans in that study did not show greater improvements in verbal memory or everyday memory. Visual memory was not assessed in ACTIVE. Finally, McDougall et al. (2010) did not control for chronic health conditions or depressive symptoms.

The cognitive training literature typically considers race as a covariate but does not explicitly examine the magnitude or mediators of racial differences in training gains. The results of this study suggest that African Americans benefited less from reasoning and memory training than non-Hispanic Whites, independent of age, sex, education, chronic health conditions, depressive symptoms, location of training, and baseline reasoning or memory performance. These differences appeared to reflect, in part, external locus of control, which was not only higher for African Americans than non-Hispanic Whites in both training groups, but also more impactful among African Americans in the reasoning training group. While racial differences in memory and reasoning training gains were attenuated after accounting for locus of control, they remained significant. The differential impact of external locus of control by race may partly explain the residual racial difference in reasoning training gain, but future studies should explore additional variables that could contribute to racial disparities in reasoning and memory training gains (e.g., adherence, perceived discrimination, educational quality).

It should be noted that racial disparities in training gain were not present for speed training, perhaps because locus of control was less influential in the efficacy of this intervention. Indeed, prior work has shown that self-efficacy, a construct highly related to locus of control, was unrelated to training gains among older adults who underwent speed-of-processing training as part of ACTIVE or the Staying Keen in Later Life (SKILL) study (Sharpe, Holup, Hansen, & Edwards, 2014). It is possible that higher-order or multi-componential constructs such as reasoning and memory may be more influenced by the psychosocial environment than a more basic ability like speed. However, this explanation is highly speculative and warrants systematic exploration in studies designed to address this question.

Another explanation for why racial disparities in training gains were evident for memory and reasoning, but not speed, is that educational factors that differ across race are less related to speed outcomes. Indeed, years of education was more strongly related to memory and reasoning outcomes than speed outcomes in the current study, and cognitive strategies taught as part of the memory and reasoning training involve verbal ability skills that are more education dependent. Although models controlled for years of education, it is likely that African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in this study also differed on other, unmeasured educational variables (e.g., school quality). Racial disparities in cognitive outcomes are often eliminated or attenuated when more sensitive indicators of school quality (e.g., single-word reading ability) are considered (Manly, Byd, Touradji & Stern, 2004; Manly, et al., 2002; Aiken-Morgan, Marsiske & Whitfield, 2008).

Unique aspects of the memory and reasoning interventions in ACTIVE, compared to the speed interventions, should be noted, though it is unclear how these differences interacted with locus of control. Reasoning and memory training sessions comprised a greater degree of social interaction, both with a trainer and with fellow group members, as compared to speed training sessions. Practice exercises in the speed training were largely carried out on a personal computer. Memory and reasoning interventions also focused on teaching strategies, while the speed intervention primarily involved computerized adaptive practice.

Because the results of this study were clearer for reasoning training than memory training, differences between reasoning and memory interventions should also be noted. For example, previous ACTIVE publications report that memory training gains were smaller than speed or reasoning training gains (Ball et al., 2002) and were not significant at year 10 (Rebok et al., 2014). Unlike memory or speed training, there were two levels of reasoning training in ACTIVE: basic and standard (Jobe et al., 2001). Assignment to training level was based on performance on test items administered at the end of the first training session. This procedure was adopted in light of extreme individual differences in performance after the first session, which highlights the relative difficulty of the reasoning tasks, compared to the memory and speed tasks. Specifically, basic and standard levels of reasoning training differed in three ways: (1) difficulty/complexity of tasks presented during the early training sessions; (2) pacing and amount of instructional time on tasks; and (3) relative emphasis on the trainer’s modeling and demonstration of strategy usage. The two levels were similar in the focus on strategies, practice on problems, feedback, and fostering of self-efficacy. Data on reasoning training level assignment are not available, precluding a direct test of whether racial differences in reasoning training gain reflect differential level assignment. However, it should be noted that models reported in the current study controlled for the influence of initial performance on training gain. In addition, the fact that the racial difference in memory training gain was of a similar magnitude to that in reasoning training gain suggests that racial differences in level assignment cannot fully explain these findings, as memory training did not involve different levels of training.

African American older adults in this study exhibited lower scores on a locus of control composite than non-Hispanic Whites, which is consistent with prior literature examining locus of control across the lifespan (Mirowsky, Ross, & Van Willigan, 1996). This difference in locus of control may relate to experiences of inequity and racism, which can result in demoralization, nihilism, and fatalism (Kelly, 2006). Such beliefs are assessed by measures of locus of control, particularly the Chance subscale used in this study. Though not explicitly examined in this study, racial discrimination and institutional barriers lead to social and economic constraints that disproportionately affect African Americans and create a disconnection between one’s efforts and outcomes (Ross & Mirowsky, 2013).

While the racial difference in locus of control observed in this study was independent of education, the relationship between education and beliefs about control has been shown to be weaker for African American compared to non-Hispanic White older adults (Shaw & Krause, 2001). In other words, African American older adults appear to have experienced less personal empowerment from schooling than non-Hispanic White older adults, which may reflect historic differences in the quality of education they received. For example, attending a desegregated school has been associated with lower scores on a sense of control scale among contemporary older adults (Wolinsky et al., 2012), presumably due to race-based discrimination during childhood. Racial differences in locus of control may also reflect cultural differences that were unmeasured in ACTIVE (Taylor, Mattis & Chatters, 1999; Aiken Morgan, et al., 2010; Marsiske et al., 2013).

A novel finding from this study was that African American and non-Hispanic White older adults differed significantly in external locus of control (i.e., beliefs that cognitive ability is due to chance or that outside assistance is needed to complete cognitive tasks), but not internal locus of control (i.e., belief in one’s intellectual competence). This result may be understood in the context of the apparently contradictory relationship between self-esteem and locus of control among African Americans. Specifically, while African Americans exhibit lower scores on general measures of locus of control, they can report comparable levels of self-esteem compared to non-Hispanic Whites, even though self-esteem and locus of control are highly correlated (Hughes & Demo, 1989). This seemingly paradoxical phenomenon indicates that self-esteem and locus of control are fostered via independent mechanisms. Specifically, self-esteem and internal locus of control may be most strongly influenced by the micro-environment (i.e., relationships with family, friends, and community), while external locus of control may be most strongly influenced by the macro-environment (i.e., societal and institutional forces).

The results of this study suggest that external, but not internal, locus of control contributes to racial disparities in memory and reasoning training outcomes. Attempts to reduce racial disparities by focusing on external locus of control (e.g., perceived barriers and constraints) may be more impactful than focusing on internal locus of control (e.g., personal competence). It should be noted that previously-reported improvements in locus of control following reasoning and speed interventions in ACTIVE were limited to internal locus of control (Internal), as no reductions in external locus of control (Chance, Powerful Others) were found (Wolinsky et al., 2010). The authors noted that external locus of control is more influenced by external factors rather than an individual’s own abilities, and only the latter were targeted in ACTIVE.

In addition to higher external locus of control, this study found stronger relationships between external locus of control and reasoning training gains among African Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites. In other words, African Americans appeared to be more vulnerable to the negative impact of external locus of control on reasoning training gains. This pattern of results suggests that non-Hispanic Whites may be protected from the negative impact of external locus of control on reasoning training efficacy, perhaps via social and other environmental advantages afforded to members of the majority group. For example, non-Hispanic Whites may have been exposed to higher-quality educational experiences that allowed them to benefit from the reasoning intervention regardless of locus of control.

In conclusion, this study found that African American older adults benefited less from reasoning and memory training than non-Hispanic Whites. These disparities reflect both higher levels of external locus of control and a greater impact of external locus of control on reasoning training gain among African Americans, while controlling for alternative factors such as education, health, depression, and baseline cognitive ability. Future intervention research with African Americans should test whether explicitly targeting external locus of control leads to greater cognitive improvement following cognitive training.

Acknowledgments

This study uses data from the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study (Ball et al., 2002; Jobe et al., 2001). This work was supported by the Advanced Psychometrics Methods in Cognitive Aging Research (R13AG030995) and by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K99AG047963. The ACTIVE intervention trials were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research to Hebrew Senior Life (U01NR04507), Indiana University School of Medicine (U01NR04508), Johns Hopkins University (U01AG14260), New England Research Institutes (U01AG14282), Pennsylvania State University (U01AG14263), the University of Alabama at Birmingham (U01AG14289), and the University of Florida (U01AG14276).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Contributor Information

Laura B. Zahodne, Columbia University

Oanh L. Meyer, University of California, Davis

Eunhee Choi, Colorado State University.

Michael L. Thomas, University of California, San Diego

Sherry L. Willis, University of Washington

Michael Marsiske, University of Florida.

Alden L. Gross, Johns Hopkins University

George W. Rebok, Johns Hopkins University

Jeanine M. Parisi, Johns Hopkins University

References

- Morgan Aiken, Marsiske M, Dzierzewski J, Jones RN, Whitfield KE, Johnson KE, Cresci MK. Race-related cognitive test bias in the ACTIVE study: A MIMIC model approach. Experimental Aging Research. 2010;36:426–452. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2010.507427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken Morgan AT, Marsiske M, Whitfield KE. Characterizing and explaining differences in cognitive test performance between African American and European American older adults. Experimental Aging Research. 2008;34:80–100. doi: 10.1080/03610730701776427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KK, Beard BL, Roenker DL, Miller RL, Griggs DS. Age and visual search: Expanding the useful field of view. JOSA A. 1988;5(12):2210–2219. doi: 10.1364/josaa.5.002210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, Willis SL for the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly Study Group. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KK, Ross LA, Roth DL, Edwards JD. Speed of processing training in the ACTIVE study: How much is needed and who benefits? Journal of Aging and Health. 2013;25:65S–84S. doi: 10.1177/0898264312470167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict R. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E. Work, retirement, race, and health disparities. In: Antonucci TC, Jackson JS, editors. Life-course perspectives on late-life health inequalities. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan LJ, Schooler C. The roles of fatalism, self-confidence, and intellectual resources in the disablement process in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:551–561. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MC, Brandt J, Carson KA, Kawas CH. Lack of relation between race and cognitive test performance in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;50:1499–1501. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal S, Shea D. Cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, and inequality among elderly people. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:437–443. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Settersten RAJ. The study of the life course: Implications for social Gerontology. In: Phillipson C, Dannefer D, editors. The SAGE handbook of social gerontology. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strychker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman H, Derman D. Kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service; 1976. (Rev. ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Brown EE, Cortina KS, Antonucci TC. Locus of control as a mediator of the relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction: age, race, and gender differences. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2006;9:239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Kawachi I, Jencks CS, Berkman LF. Does childhood schooling affect old age memory or mental status? Using state schooling laws as natural experiments. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62:532–537. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Weuve J, Chen JT. Methodological challenges in causal research on racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive trajectories: measurement, selection, and bias. Neuropsychology Review. 2008;18:194–213. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9066-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda J, Schaie KW. Schaie-Thurstone Mental Abilities Test: Word Series Test. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gross AL, Rebok GW. Memory training an dstrategy use in older adults: results from the ACTIVE study. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(3):503–517. doi: 10.1037/a0022687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AL, Rebok GW, Brandt J, Tommet D, Marsiske M, Jones RN. Modeling learning tests: results from ACTIVE. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68(2):153–167. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD study. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B:37–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.37. Special Issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structural analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Demo DH. Self-perceptions of Black Americans: Self-esteem and personal efficacy. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;95:132–159. [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Ram N, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Long-term antecedents and outcomes of perceived control. Psychology & Aging. 2011;26:559–575. doi: 10.1037/a0022890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe JB, Smith DM, Ball K, Tennstedt SL, Marsiske M, Willis SL, Kleinman K. ACTIVE: A cognitive intervention trial to promote independence in older adults. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2001;22:453–479. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN. Racial bias in the assessment of cognitive functioning of older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7:8–103. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000045872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with African Americans. In: Hays PA, Gayle Y, editors. Culturally responsive cognitive-behavioral therapy: Assessment, practice, and supervision. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SW, Allaire JC, Gamaldo AA, Whitfield KE. Race differences in intellectual control beliefs and cognitive functioning. Experimental Aging Research. 2012;38:247–264. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2012.672122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Perceived control over aging-related declines. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Locus of control in aging research: A case for multidimensional and domain-specific assessment. Psychology and Aging. 1986;1:34–40. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Perceptions of intellectual aging: Antecedent or consequence of intellectual functioning? Developmental Psychology. 1983;19:482–498. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Baltes P, Nesselroade JR, Willis SL. Examination of personality-ability relationships in the elderly: The role of the contextual (interface) assessment mode. Journal of Research in Personality. 1982;6:485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Firth KM. The adaptive value of feeling in control during midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler R, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Leff R. Perceived control and intellectual functioning in the elderly: A 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:722–728. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Neupert SD, Agrigoroaei S. The relevance of control beliefs for health and aging. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 7. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson H. Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance. In: Lefcourt H, editor. Research with the locus of control construct. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 15–63. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Byrd DA, Touradji P, Stern Y. Acculturation, reading level, and neuropsychological test performance among African American elders. Applied Neuropsychology. 2004;11(1):37–46. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1101_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Bell K, Merchant CA, Stern Y. Cognitive test performance among nondemented elderly African Americans and Whites. Neurology. 1998;50:1238–1245. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiske M, Dzierzewski JM, Thomas KR, Kasten L, Jones R, Johnson K, Rebok G. Race-related disparities in five-year cognitive level and change in untrained ACTIVE participants. Journal of Aging and Health. 2013;25:103S–127S. doi: 10.1177/0898264313497794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall GJ, Becker H, Pituch K, Acee TW, Vaughan PW, Delville CL. The SeniorWISE study: Improving everyday memory in older adults. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;24:291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross C. Life course trajectories of perceived control and their relationship to education. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1339–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE, Van Willigan M. Instrumentalism in the land of opportunity: Socioeconomic causes and emotional consequences. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1996;59:322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Allaire JC. I think I can, I think I can: Examining the within-person coupling of control beliefs and cognition in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:742–749. doi: 10.1037/a0026447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM. The precious and the precocious: Understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. The Gerontologist. 1996;36(2):230–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand A, Henretta J. Age and inequality: diverse pathways through later life. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M, Shapiro T. Black wealth, White wealth: A new perspective on racial inequality. 2. New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C, Ball K, Sloane ME, Roenker DL, Bruni JR. Visual/cognitive correlates of vehicle accidents in older drivers. Psychology and Aging. 1991;6(3):403–415. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C, Ball K, McGwin G, Jr, Sloane ME, Roenker DL, White MF, Overley ET. Visual processing impairment and risk of motor vehicle crash among older adults. JAMA. 1998;279(14):1083–1088. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.14.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes KR. Dimensionality of Rotter’s locus of control scale: an application of the “very simple structure” technique. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rebok GW, Ball K, Guey LT, Jones RN, Kim HY, Willis SL for the ACTIVE Study Group. Ten-year effects of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62:16–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebok GW, Langbaum JBS, Jones RN, Gross AL, Parisi JM, Brandt J. Memory training in the ACTIVE study: How much is needed and who benefits? Journal of Aging and Health. 2013;25:21S–42S. doi: 10.1177/0898264312461937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. The sense of personal control: Social structural causes and emotional consequences. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, Bierman A, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. 2. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg PS. White privilege: Essential readings on the other side of racism. New York: Worth Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs. 1966;80:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S. Age, education, and the sense of control. Research on Aging. 2001;23:153–178. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test: A handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BS, Glass TA, Bolla KI, Stewart WF, Glass G, Bandeen-Roche K. Disparities in cognitive functioning by race/ethnicity in the Baltimore Memory Study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112:314–320. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MF, Larson EB, Gibbons L, McCormick WC, Teri L. Alzheimer’s disease symptom severity in Blacks and Whites. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:482–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe C, Holup AA, Hansen KE, Edwards JD. Does self-efficacy affect responsiveness to cognitive speed of processing training? Journal of Aging and Health. 2014;26:786–806. doi: 10.1177/0898264314531615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA, Krause N. Exploring race variations in aging and personal control. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56:S119–124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.s119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan FA, Wang J. Disparities among older adults in measures of cognitive function by race or ethnicity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:P242–P250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.p242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Bingham SA, Khaw KT. Mastery is associated with cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women at apparently low risk. Health Psychology. 2010;29:412–420. doi: 10.1037/a0019432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among African Americans: A synthesis of findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:524–543. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone LL, Thurstone TG. Examiner manual for the SRT Primary Mental Abilities Test (Form 10–14) Chicago: Science Research Associates; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Turiano NA, Chapman BP, Agrigoroaei S, Infurna FJ, Lachman M. Perceived control reduces mortality risk at low, not high, education levels. Health Psychology. 2014 Feb 3; doi: 10.1037/hea0000022. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hea0000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Warner DF, Hayward MD. Early-life origins of the race gap in men’s mortality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(3):209–226. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RL, Yassuda MS. Aging and memory control beliefs: Performance in relation to goal setting and memory self-evaluation. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:56–65. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.p56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Jay GM. Lagged relationships between cognitive abilities and personality. Pennsylvania State University; 1989. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Jay GM, Diehl M, Marsiske M. Longitudinal change and prediction of everyday task competence in the elderly. Research on Aging. 1992;14:68–91. doi: 10.1177/0164027592141004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Caskie GIL. Reasoning training in the ACTIVE study: How much is needed and who benefits? Journal of Aging and Health. 2013;25:43S–64S. doi: 10.1177/0898264313503987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SL, Tennstedt SL, Marsiske M, Ball K, Elias J, Koepke KM, Stoddard AM. Long-term effects of cognitive training on everyday functional outcomes in older adults. JAMA. 2006;296:2805–2814. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B, Cockburn J, Baddeley A. The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test. Titchfield, Fareham, Hampshire, UK: Thames Valley Test Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky FD, Andresen EJ, Malmstrom TK, Miller JP, Schootman M, Miller DK. Childhood school segregation and later life sense of control and physical performance in the African American Health cohort. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:827–840. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky FD, Vander Weg MW, Martin R, Unverzagt FW, Willis SL, Tennstedt SL. Does cognitive training improve internal locus of control among older adults? The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65:591–598. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsembik BA, Peek MK. Race differences in cognitive functioning among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56:266–274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]