Abstract

Despite intensive studies since the 1990s, the physiological role of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) remains elusive. Here, we present a novel concept suggesting that PrPC contributes to immunological quiescence in addition to cell protection. PrPC is highly expressed in diverse organs that by multiple means are particularly protected from inflammation, such as the brain, eye, placenta, pregnant uterus, and testes, while at the same time it is expressed in most cells of the lymphoreticular system. In this paradigm, PrPC serves two principal roles: to modulate the inflammatory potential of immune cells and to protect vulnerable parenchymal cells against noxious insults generated through inflammation. Here, we review studies of PrPC physiology in view of this concept.

Keywords: prion protein, immune privilege, immune modulation, cytoprotection, cell signaling, inflammation, neurodegeneration, Alzheimer

Introduction

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is known for its crucial involvement, via its scrapie isoform PrPSc, in the development of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in man and scrapie in sheep and goats. In these fatal diseases, the spontaneous or template-directed misfolding of PrPC into abnormal PrPSc subverts PrPC’s normal function and causes synaptic loss and neuronal demise (1, 2). Despite extensive investigations for three decades, PrPC remains a conundrum. What is the major physiological role of this protein and why does it exist under a plethora of isoforms and interact with so many partners? Why do Prnp knockout mice develop normally and without major phenotypic alterations, although PrPC is ubiquitous and highly conserved between species? Here, based on the current knowledge of PrPC function, we provide an overview of its potential contribution to a phenomenon generically known as immune privilege, providing a new angle to the question of the physiological role of PrPC.

During evolution of the vertebrate immune system, the potency of inflammatory responses has increased, not least during the transition from ectothermic (fish, amphibians, and reptiles) to endothermic (birds and mammals) species, dramatically increasing O2 consumption and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (3). In parallel with increasing immunological firepower, to combat intruding microorganisms and cancer cells, several anti-inflammatory and protective measures have evolved to shield “innocent bystander” cells from inflammatory damage. Interestingly, major areas of modern medical treatment are concerned with dampening inflammatory responses. In organs such as the eye, the brain, pregnant uterus, and testicles, inflammation can have devastating consequences. One fascinating development to protect such tissues with limited regenerative capacity is the evolution of immune privilege. This phenomenon is established through combinations of physical barriers and circulatory adaptations, together with organ expression of potent cell surface and soluble immunomodulatory factors (4). The principal concept presented in this review is that PrPC serves an anti-inflammatory and protective role. This explains the prevalent observation that phenotypes due to loss of PrPC are minor if detectable at all under physiological conditions, while clearly evident under stress and particularly under inflammation in immune-privileged organs, such as the brain.

Immune Privilege

In the late nineteenth century, VanDooremaal and later, in the 1940s, Medawar pioneered studies that defined “immune privilege” after studying grafts that survived after being transplanted into the brain or anterior chamber of the eye (5) [reviewed in Ref. (6)]. Classically, immune-privileged sites were the central nervous system (CNS), the anterior chamber of the eye, the placenta and fetus, and testicles. Immune privilege was considered a static phenomenon, mainly resulting from anatomical and circulatory peculiarities, such as an apparent lack of lymphatic drainage. This concept was supported by the discovery of the blood–brain barrier and later the blood–testis barrier (7).

Today, our understanding of immune privilege, often referred to as immunological quiescence, is vastly extended, and may be defined as a dynamic and highly complex interplay between anatomical, physiological and immunoregulatory adaptations, which together restrict, deviate, and block inflammatory processes in the privileged tissue (8, 9). Moreover, many organs and cellular niches can obtain immune privilege, and certain elements of immune privilege have been observed in tumor growth and during chronic inflammation. Importantly, immune privilege is not a general immunosuppression, but involves tight control and often downregulation of those immune responses that potentially cause severe tissue damage. These include cytotoxic T cells, natural killer cells (NK), and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Several cell surface and extracellular proteins play important parts in immune privilege, e.g., the immunomodulatory enzyme indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) which causes a local depletion of L-tryptophan and thereby halts proliferation of T cells (10), the apoptosis-stimulating receptor ligand couple Fas/FasL (11), tumor necrosis factor alpha apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) (12), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (13), amongst others. In addition, in many immune-privileged organs, cells, such as neurons, have low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ia molecules, which confer fundamental protection from cytotoxic T cells [reviewed in Ref. (4)]. They instead express non-classical MHC class Ib molecules that downregulate NK cell activity. Novel immunomodulating proteins are constantly being discovered (14, 15), and considering the importance of monitoring and fine-tuning inflammatory responses in particularly vulnerable organs, there are probably many more to come.

Another contribution to immune privilege is active recruitment of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (TREGs), which suppress the activation of other T cells, both directly and indirectly [reviewed in Ref. (16)]. TREGs exert their immunosuppressive activities in various ways, such as cell-cycle arrest via suppressive cytokines, e.g., IL-10 and TGF-β or cell surface expression and secretion of molecules, such as Galectin-1. They can induce apoptosis in IL-2-dependent T cells via IL-2 uptake or direct cytolysis via, e.g., granzyme. Indirectly, TREGs can also exert their effects on antigen-presenting cells, impairing their co-stimulatory or antigen-presenting activity or inducing them to remain naïve.

Posttranslational Modifications of PrPC

Cellular prion protein is a 210-residue glycoprotein, encoded by a single-copy gene denoted Prnp (17, 18). It is mainly located at the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, attached by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (19) and exists in many forms due to variable N-glycosylation (20) and proteolytic processing (21, 22).

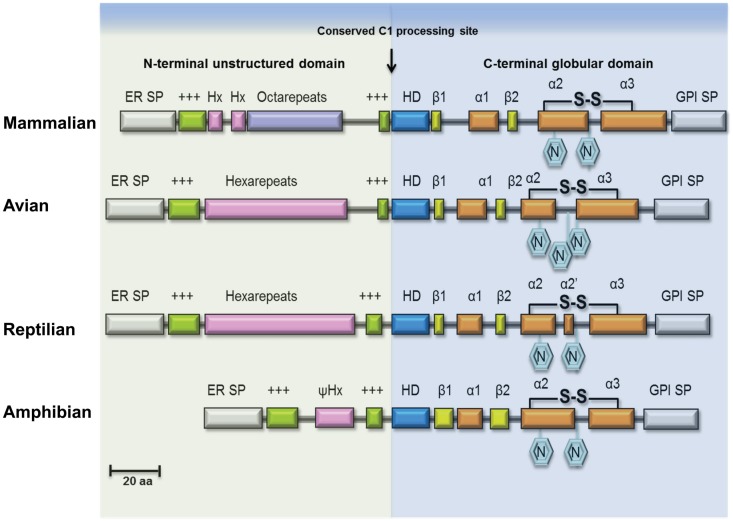

Mammalian PrPC has two N-X-T sequence motifs for glycosylation (Figure 1) and most PrPC isolated from tissues is indeed diglycosylated. The glycosylation sites of mammalian PrPC appear invariant and they are conserved in avian, reptilian, and amphibian PrPC sequences; glycosylation promotes trafficking of PrPC to the plasma membrane and may increase PrPC half-life. As a response to oxidative stress, mammalian PrPC can be cleaved near codon 90 generating fragments PrP-N2 and PrP-C2 (22, 23). Alternatively, while passing the late-Golgi compartment, a subset of PrPC is processed into two fragments PrP-N1 and PrP-C1 (Figure 1, C1 processing site) (24). The N-terminal PrP-N1 fragment is secreted, whereas the remaining C-terminal fragment PrP-C1 remains attached to the cell membrane. Whether it is localized in lipid rafts like full-length PrPC remains to be shown.

Figure 1.

Structural features of PrPC in vertebrate lineages. Schematic illustration of major structural features of PrPC in terrestrial vertebrates. The ER transfer signal peptide (ER SP) and the glycophosphatidylinositol-anchor attachment signal peptide (GPI SP) are removed during maturation of the primary translation product, followed by N-glycosylation and cysteine bridge formation in the C-terminus. The N-terminal domain is an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) of variable length containing repeated sequence elements (pink/purple) flanked by two positively charged amino-acids motifs (green). In mammalian PrPC, this region contains a number of glycine-rich octapeptides or nonapeptides, preceded by two hexapeptides, while in avian and reptilian PrPC it is comprised entirely of hexapeptides, and in amphibian PrPC only a very short pseudo-hexapeptide (ψHx) sequence is present. A highly conserved hydrophobic, alanine-rich motif (HD) at the center is characteristic for PrPC. Proteolytic cleavage of PrPC, known as α-cleavage (arrow) occurs N-terminal to the HD-motif at the boundary between the IDR domain and the globular C-terminal domain thus generating the fragments PrP-N1 and PrP-C1 of PrPC (not shown). The globular domain consists in most PrPs of three helices (α1, α2, α3) and a β-sheet formed by two short β-strands (β1, β2).

PrP-C1 may also be generated on the cell membrane (23), while C-terminal shedding by ADAM10 can release full-length PrPC (and PrP-C1) from the membrane (25, 26). The generation of truncated PrP-C1 is conserved in avian PrPC and is likely to occur also in other vertebrates, intriguingly it is also seen in other prion family genes (PRND, SPRN) (27) and even in the structurally related zinc-transporter ZIP10 (SLC39A10) (28). Although PrPC processing is in principal conserved, there is evidence that the degree of cleavage and shedding is dependent on the PrPC sequence (29). Questions remain whether cleavage and PrP-C1 specifically may influence regulation and function attributed to normal prion protein and because full-length PrPC and PrP-C1 are not always experimentally differentiated it is often left unresolved which of the isoforms is actually responsible for the observed activity. However, the recent finding that PrP-C1 exhibited myelinotrophic activity in the peripheral nervous system strengthens the concept that all the various PrPC molecules have physiological importance (30).

The Intrinsically Disordered N-Terminal Domain of PrPC

Structural studies revealed that PrPC is composed of an intrinsically disordered N-terminal and a structured C-terminal domain, containing three α-helical regions and a short, two-stranded ß-sheet (31–33). Classically, the activity of a protein was linked to the ability of the polypeptide chain to adopt a stable secondary/tertiary structure. This concept was extended when it became evident that intrinsically disordered region (IDRs) and proteins can participate in a broad range of defined physiological activities and play a major role in several protein classes, including transcription factors, scaffold proteins, and signaling molecules (34–36). This ability of IDRs to interact with many different substrates may explain the observation that PrPC can flexibly engage in a variety of supramolecular complexes (see below).

Considering the evolution of PrPC, it is interesting to note that the three-dimensional structure of the globular C-terminal domain of human (121–230), chicken (121–225), turtle (121–225), and xenopus (90–222) PrPC show extensive similarities, indicating a conserved activity (37). By contrast, the N-terminal IDR of PrPC shows high diversity between vertebrate classes. This is in line with the observation that IDRs often evolve more rapidly than well-structured protein domains (38). Many IDRs show sequence conservation, sometimes involving particular amino-acid residues, such as leucine (L), proline (P), tyrosine (Y), and tryptophan (W) (39). The IDR of PrPC harbors many of these characteristics. Specifically, mammalian PrPCs contain glycine-rich octarepeats with conserved W, P, and histidine (H) residues in this region (18, 40–46), while a hexarepeat region with conserved P, H, and Y is found in avian (47–49) and reptile PrPCs (50). Strikingly, amphibian PrPC is devoid of any repeats and H residues (51). Interestingly, IDRs are prevalent in virus proteins, allowing many interacting partners. Correspondingly, many proteins involved in innate immunity also carry IDRs, which may reflect the evolutionary “arms” race between invading pathogens and the host immune system. The evolutionary modifications that can be observed in the N-terminal IDR of PrPC among terrestrial vertebrates may indeed be a relic of these evolving immune functions. The most apparent evolutionary change that has occurred first in some reptilian species and then has become the norm in avian and mammalian PrPC are precisely spaced H residues which allow binding of divalent metal-ions, such as Cu2+ (52) and Zn2+ (53). Cu2+ binding will not only confer structural order to the N-terminus (54) but also by operating as a sensitive regulator of the structural state of PrPC’s IDR it may govern protein interactions and proteolytic processing (PrP-N1/PrP-C1).

Studies, comparing wild-type PrPC with mutated PrPs lacking the repeat region have shown that the octarepeat region is crucial for PrPC’s neuroprotective activity. For instance against Bax induced cell death (55) or toxicity caused by ectopic expression of the PrP-like protein Doppel (Dpl) (56, 57), excitotoxic stress and PrPSc toxicity (58). Interestingly, Drisaldi and co-workers demonstrated that the neuroprotective function of the repeat region is dependent on four histidine residues (57). Furthermore, the repeat region is also necessary for the PrP-mediated neuroprotection observed in models of brain ischemia (59). Similarly, the ability of PrPC to transmit neurotoxic signaling of amyloid beta (Aβ) and other neurotoxic β-sheet-rich-conformers is greatly diminished in PrPC mutants devoid of this domain (60). Further studies of the mechanisms underlying the activities of the IDR of PrPC and its evolution, particularly in neuro-immune crosstalk appears to be an important area for future research.

Functionally, PrPC can by virtue of its GPI anchor move between membrane subdomains (61, 62), and interact with many partners at the cell surface. These partners may include other GPI-anchored molecules like the proteoglycan Glypican-1 (63), transmembrane proteins like the neural cell-adhesion molecule, NCAM (64), the low-density-related protein LRP1 (65), the amyloid precursor protein APP (64, 66), lipid raft constituents such as caveolin (67), or src kinases (68, 69). The formation of these complexes may occur following the interaction of PrPC with extracellular matrix components, e.g., vitronectin (70) or laminin (71) or soluble ligands such as the extracellular chaperone stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 (STI1) (72). Moreover, in lymphoid cells PrPC has been shown to be recruited into microdomains of the membrane, the so-called immunological synapses harboring T-cell receptor components (73–76). As discussed above, many ligands appear to interact with the N-terminal IDR of PrPC [reviewed in Ref. (77)].

Of major pathophysiological relevance is the ability of the N-terminal PrP fragment (PrP-N1) to bind to and to mediate toxic effects of Aβ oligomers (78). PrPC may further engage into homophilic interactions or bind the two other members of the prion protein family Doppel and Shadoo (58, 68). It could be speculated that shed PrPC or PrP-N1 can act at a distance via extracellular fluids. Indeed it has been demonstrated that soluble PrP-N1 fragments can prevent Aβ-induced toxicity and have a neuroprotective activity (79–84).

PrPC Pattern of Expression

Although PrPC is ubiquitously expressed, its main expression overlaps strikingly with the distribution of immunologically quiescent sites (Figure 2). PrPC is abundantly present in the central and peripheral nervous system (17, 18, 85), glial cells of the CNS (86, 87), and in the testes, eye, placenta, and uterus (88, 89). PrPC is also present in the neurovascular unit, including endothelial cells (90, 91), it may thus be one of the protagonists modulating blood–brain barrier functions (92).

Figure 2.

The expression pattern of Prnp overlaps with immune-privileged organs and extends into the lymphoreticular system. Schematic representation of (A) major immune-privileged organs; highlighting the brain, testes, pregnant uterus, and eye, and (B) the organs with highest levels of PrPC overlap with the immune-privileged organs with the addition of lymphoreticular tissues, illustrated with lymph nodes and the spleen.

Cellular prion protein is also found in microglial cells (93). Whether its expression is associated with the inflammatory M1 producing TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, or the immunosuppressive M2 (producing IL-10 and TGF-β) phenotype of microglia has not been clarified. Notwithstanding, the observation that Prnp knockout mice produce less of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in response to LPS-induced chronic inflammation would suggest a positive role for PrPC in M2 microglia (94).

Cellular prion protein is abundantly expressed in neuronal and non-neuronal stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (95) and it contributes to stem-cell renewal, reviewed by Lopes and Santos (96) and Martin-Lannerée et al. (97). HSCs have been shown to co-localize with TREGs, suggesting that TREGs provide a “shield” conferring relative immune privilege to the HSCs (98). Interestingly, PrPC is found at high levels in both immature HSCs (95) and TREGs (99), and probably contributes to the interplay between HSCs and TREG cells in this niche.

Differentiation of HSCs along the lymphoid (100–102) or monocytic (103) lineages maintains the expression of surface PrPC, while during the granulocyte maturation PrPC is downregulated (104). Within lymphoid cells, B cells express lower levels of PrPC compared to T cells and NK cells (105), which could be linked to the observation that B cells are not repressed in immune-privileged sites. Regulatory CD4+ CD25+ T cells expressed 4.5 fold higher levels of Prnp mRNA and showed a 10-fold higher intensity of surface PrPC than CD4+ CD25− T cells (99). However, an attempt to identify the role of PrPC in TREGs using Prnp knockout mice was unsuccessful since no loss-of-function phenotypes could be recognized in Tregs without PrPC expression (99). In most immune cells, PrPC is dynamically expressed and generally naïve immune cells contain less PrPC than mature or stimulated immune cells, with a few exceptions (105, 106). Even neutrophils strongly upregulate PrPC levels after treatment with immunosuppressive TGF-β or dexamethasone (107). On some immune cells, such as mast cells, Prnp is highly and constitutively expressed and PrPC is rapidly released from the cell surface when these cells are activated (108).

Following from the concept presented here, the principal role of PrPC in immune-privileged organs would be to protect against inflammatory damage. The dynamically regulated levels of PrPC observed in cells of the immune system, particularly the high expression in immunosuppressive TREGs, indicate that PrPC is important in immunological homeostasis.

Inflammation Reveals Cytoprotective and Immunomodulatory Roles of PrPC

Prnp knockout mice develop normally, with normal life expectancy (109, 110) and exhibit complete resistance toward prion infection. Despite a relative lack of robust and reproducible phenotypes under physiological conditions, a wide variety of roles for PrPC have been suggested, such as in maintenance of axonal myelin (30, 111), modulating circadian rhythms (112), and neuronal excitability (113). For a comprehensive review of suggested physiological roles of PrPC, see Ref. (114). In addition to murine models, Prnp knockout cattle have been produced (115). After extensive analysis, under physiological conditions, only minor phenotypes were observed. Similar findings have been reported from a recently discovered line of Norwegian dairy goats, carrying a nonsense mutation that renders these animals devoid of PrPC (116, 117).

Interestingly, experiments with Prnp knockout mice involving a diverse set of inflammatory processes (Table 1), such as experimental brain ischemia, brain trauma, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), experimental colitis, and, intracerebral infection with encephalomyocarditis virus variant B (EMCV-B), have revealed that in the absence of PrPC, inflammatory damage is greatly exacerbated; reviewed by Onodera et al. (118).

Table 1.

Loss of PrPC aggravates immunopathology in a variety of experimental settings.

| Tissue damagea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Insult | Prnp wild type | Prnp knockout | Reference |

| Brain ischemia | ++ | ++++ | (59, 119–122) |

| Brain trauma | ++ | ++++ | (123, 124) |

| Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) | ++ | ++++ | (125, 126) |

| Experimental colitis | ++ | ++++ | (127) |

| Encephalomyocarditis Virus variant B | ++ | ++++ | (128) |

aRefers to onset, duration, and severity of inflammation and magnitude of tissue damage.

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice, a chronic demyelinating disease of the CNS and a model of multiple sclerosis in humans, is often induced by immunization with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). Autoantigen-specific T cells of both the Th1 and Th17 phenotypes cross the BBB and are the primary immune cells recruited to the CNS where they activate microglia and attract blood monocytes and other inflammatory cells (129). Induction of EAE by MOG injection in Prnp knockout mice resulted in earlier onset, prolonged and more severe neuroinflammation than in normal mice (125). The Prnp knockout mice had persisting T-cell and monocytic/microglial infiltrates in the CNS, accompanied by demyelination and axonal drop-out in spinal cord white matter. It was concluded that PrPC modulates T-cell-mediated neuroinflammation, with a suppressive effect on MOG-induced peripheral T-cell responses and the authors discussed whether the larger pathological lesions in mice lacking PrPC also could be caused by increased cellular susceptibility to oxidative stress.

Gourdain and colleagues (126) conducted experiments with reciprocal bone marrow chimeras with lack of PrPC expression in lymphoid cells or the CNS, but did not observe earlier disease onset nor increased leukocyte infiltration in the CNS in animals with Prnp knockout lymphocytes. However, they observed significantly higher pathology scores in mice lacking PrPC expression in the brain, and concluded that PrPC primarily confers neuroprotection against neuroinflammatory insult. In a different attempt to discriminate neuroprotection by PrPC from immunoregulatory roles, Hu and co-workers (130) used pharmacologically selective silencing of PrPC in lymphocytes in models of nervous system autoimmune disease. They were able to show that depletion of PrPC in lymphocytes directly affected T-cell activation, survival, and differentiation. In the absence of PrPC expression in lymphocytes, the severity of EAE was considerably increased. They concluded that lack of PrPC in lymphocytes resulted in pro-inflammatory activities and that autoimmune brain pathologies could develop despite protective PrPC expression in neuronal cells. Thus, under these experimental conditions, the role for PrPC as a regulator of immunological homeostasis apparently dominated the cytoprotective role of the protein in the CNS. In Gourdain et al. (126), the authors state that their data do not exclude an important role for PrPC, particularly in early lymphoid responses. They further discuss several possible explanations for the conflicting results in their study and the study by Hu et al. (130). The models used are complicated and obviously differ in many aspects, such as mouse strain, encephalitogenic antigens, T-cell assay protocols and differences in methodology for gene silencing, all factors that may have contributed to the discrepancies.

In a different model with induction of focal brain ischemia, Prnp knockout mice experience more severe tissue damage after focal brain ischemia than wild-type mice (59, 119–121). Spudich and colleagues observed 200% larger infarct volume in Prnp knockout mice. In addition, an induction of ERK1/2, STAT1, JNK1/2, and Caspase-3 activity in the Prnp knockouts suggests that these signaling molecules are involved in Prnp knockout-related neuronal cell death (120). Significantly increased infarction volumes were also observed in Prnp knockout mice, in studies of permanent and transient focal cerebral ischemia (121). Moreover, they observed reduced levels of phosphorylated Akt and enhanced neuronal caspase-3 activation in Prnp knockout mice. In a rat stroke model, Shyu and colleagues revealed a time-dependent increase in PrPC levels in infarcted tissue to reach a peak 3 days post infarction and that overexpression of PrPC reduced ischemic injury (122). Mitsios and colleagues detected increased levels of PrPC in plasma from human stroke patients compared with healthy controls (131). Moreover, they found upregulation of PrPC in gray matter peri-infarcted tissue and in infarcted tissue, in 6 out of 10 patients. In a study of traumatic brain injury, Prnp knockout mice had a larger lesion volume and a breakdown of the blood–brain barrier 1 month after injury compared to wild-type mice (123). Interestingly, it has been observed that Prnp mRNA is one of two most upregulated mRNAs after induced traumatic brain injury in mice (124), supporting a protective role for PrPC. From the studies on ischemic and traumatic brain injury, the role of inflammation in the development of lesions remains to be clarified, since no inflammation-specific parameters were measured, nor infiltration of cells along the borders of the necrotic tissue were observed. Cell death also activates inflammation and further studies should include the role of cytokines and immune cells, such as locally activated or blood-derived macrophages/microglia, when evaluating how PrPC influences damage control (94).

Intracranial infection with EMCV-B resulted in similar viral titers in wild-type and Prnp knockout mice, however, mice lacking PrPC showed higher numbers of apoptotic neurons, while wild-type mice had more activation of microglial cells as well as more severe infiltration of immune cells in the hippocampal area (128), suggesting that PrPC affected the inflammatory response, while also serving a protective, anti-apoptotic role during the infection.

In a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease, mice lacking PrPC developed a more severe colitis with markedly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-apoptotic regulatory proteins (127). Moreover, it was shown that overexpression of PrPC protected against induction of colitis. Interestingly, lack of PrPC has been shown to skew T-cell development in favor of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 phenotypes (125, 130).

Taken together, these observations made under different experimental modalities demonstrate that PrPC both mediates cytoprotective signaling under inflammatory stress and has the capacity to attenuate the inflammation itself.

In summary, PrPC is highly expressed in immune-privileged organs and it serves a protective role evident most clearly under inflammatory stress and/or tissue damage. Moreover, data show that PrPC is more than a passive protector, but also dampens the inflammation itself, by modulating the activity of immune cells in an anti-inflammatory direction. The latter role of PrPC fits well into the concept of immune privilege and immune modulation. The molecular details and signaling pathways by which PrPC modulates inflammation are not yet clarified and stand out as a challenging area of future research. Below, we highlight some of the current data on signaling mediated via or influenced by PrPC presence on the cell surface.

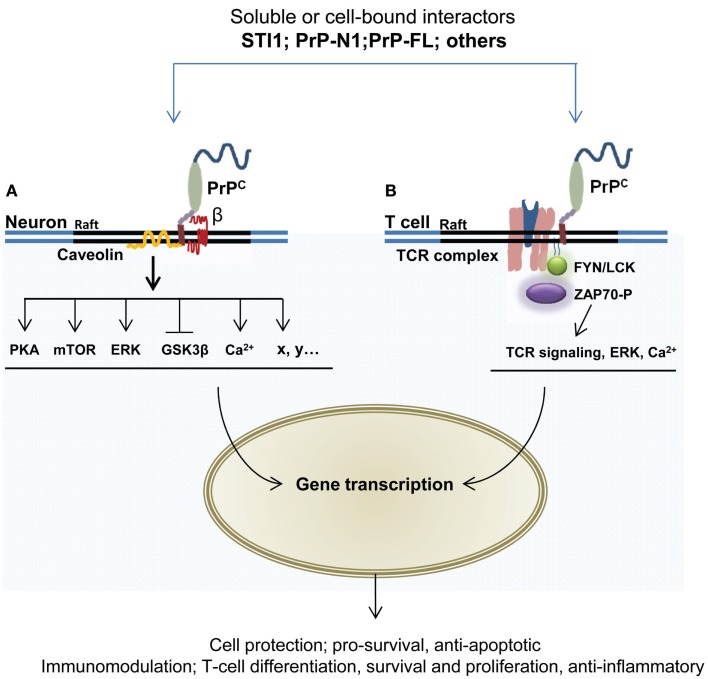

PrPC in Cytoprotective and Immunoregulatory Signaling

At a molecular level, the cytoprotective activity of PrPC may depend on its capacity to engage into multimolecular complexes at the cell surface and mobilize signal transduction cascades. For a review of these signaling events in neuronal cells, see Ref. (132). With respect to the concept presented here, the molecular cascades underlying the potential contribution of PrPC to immune quiescence remain to be dissected. However, many of these probably overlap with cytoprotective signaling, which is better characterized. We will therefore elaborate somewhat on PrPC partners and effectors potentially contributing to its cytoprotective activity (Figure 3). The extracellular co-chaperone STI1, identified as a PrPC partner in 1997 through a complementary hydropathy approach (133), is a well-established inducer of PrPC-dependent signals. The STI1–PrPC interaction has been shown to protect retinal (72, 134) and hippocampal neurons (135) against chemically induced apoptosis, in both cases via cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA). The neuroprotective action of this partnership is also supported by the recruitment of mTOR (136) as well as the inactivation of the GSK3β kinase (69), whose overactivity is detrimental to neurons (137). Noteworthy, STI1 can be secreted from astrocytes (138), a cell type highly contributing to immune quiescence in the CNS (92). STI1 may act in a cell-autonomous manner to favor astrocytic differentiation upon binding to PrPC (139). Whether the STI1–PrPC interaction also instigates a dialog between astrocytes and neurons deserves to be considered. Interestingly, astrocytes release STI1 in response to oxygen–glucose deprivation (140), and thereby induce neuroprotective signals through PrPC. In line with this, Lee and colleagues found that STI1 is induced in the ischemic brain and contributes to recovery via PrPC (141). The same study showed that the upregulation of STI1 promotes the recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells to the ischemic brain and thereby helps reducing brain injury. Although the full pathway of signaling events imparted by the STI1–PrPC duo in this context remains to be elucidated, a beneficial contribution of the downregulation of matrix-metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) transcripts and activity fostered by PrPC (142) should be proposed, since MMP-9 knockout mice are less vulnerable to ischemia than their wild-type counterparts (143), possibly because activation of MMPs during brain injury leads to increased permeability of the glia limitans (144), separating the perivascular space from the neural tissue proper and thereby opens for a higher flux of cells and solutes into the neuropil.

Figure 3.

GPI-anchored PrPC has the capacity to interact with multiple partners and trigger cell signaling events leading to neuroprotection and immunomodulation. The formation of PrPC-containing multimolecular complexes and subsequent mobilization of protective or immunomodulatory signals may be induced following the binding of soluble ligands, such as STI1, PrPC itself, or its N-terminal domain (PrP-N1). (A) In neurons, several targets of PrPC signaling relay its neuroprotective action, including protein kinase A, mTOR, the MAP kinases ERK1/2, and GSK3b. This action may also involve intracellular calcium mobilization. Some of these signaling cascades require the association of PrPC with the membrane protein caveolin. The participation of transmembrane partner(s) of PrPC to the signaling complexes is represented by «β». (B) In T lymphocytes, PrPC is enriched at the immunological synapse, where it can interact with components of the T cell receptor (TCR), such as the Fyn tyrosine kinase and the zeta chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70). These interactions may further promote the activation of downstream effectors, including NFkB, JNK, ERK, as well as elevation of intracellular calcium concentration.

In addition to the mature brain, the cytoprotective action of the PrPC–STI1 interaction may operate during embryonic development since the two proteins are expressed from early stages (140, 145). Beraldo and colleagues reported that maternally derived STI1 can be found in blastocysts. Deletion of the STI1 gene in mice leads to embryonic lethality around E9–E10.5 due to placental disruption and lack of cellular viability (140). The molecular details causing embryonal lethality in the STI1 knockout mice have not been elucidated. This drastic phenotype implies that STI1 signaling in early embryos is relayed by several receptors beyond PrPC. These include the activin receptor-like kinase-2 (ALK2) (146), whose deficiency leads to developmental arrest at the gastrulation stage (147). Another possibility to be considered is the binding of STI1 to the PrPC homolog Shadoo, which is abundantly expressed in extra-embryonic annexes, and which may have overlapping functions with PrPC during early development (148). Notwithstanding, because PrPC is abundant in extra-embryonic annexes (148), STI1–PrPC protective signaling is likely to also occur in placenta, another important site of immune privilege. With respect to embryonic development, it is worth noting that the binding of STI1 to PrPC enhances the self-renewal of neural progenitor cells (149). On the other side, however, STI1–PrPC signaling appears to contribute to tumor growth (150) (see below).

Regarding cells of the immunological lineage, it has long been known that PrPC is present on the surface of lymphocytes and that it is rapidly upregulated upon activation of these cells (100–102). Mattei and co-workers demonstrated that PrPC was part of a signaling complex involved in T-cell activation (73). Furthermore, through immunoprecipitation they observed an association between PrPC and the signaling tyrosine kinase Fyn, and, in activated T cells, PrPC was co-immunoprecipitated with zeta chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70), a protein of central importance in T-cell receptor signaling. Upon silencing of PrPC in lymphocytes by Prnp siRNA, an increase in ZAP-70 activation was seen with a corresponding rise in CD3/CD28 which was stimulated by transcription factor NFAT/AP-1, known for its function in T-cell signaling and differentiation (130). In Jurkat lymphocytes, a co-localization of PrPC and T-cell co-receptor CD3ϵ and the lipid-raft ganglioside GM1 was observed (74, 76). Further compelling evidence of PrPC operating in immunological synapses, such as in antigen-driven interactions between T cells and DCs, have been reported (75). Interestingly, absence of PrPC in T cells and DCs had different consequences for T-cell proliferation; T cells devoid of PrPC exhibited a normal allogenic antigen response, while DCs without PrPC significantly reduced proliferation in interacting T cells, suggesting that PrPC might serve different signaling roles in the two cell types. From experiments using PrPC antibodies, the authors concluded that PrPC is a negative regulator of T-cell receptor signaling and that PrPC modulates neuroinflammation.

PrPC and Cancer

While immune privilege represents a physiological safeguard mechanism, it is also known to be hijacked by cancer cells to evade antitumor immunity (151). Over a decade ago, PrPC was found to be overexpressed in a breast cancer cell line that was resistant to TNFα-induced cell death (152). A correlation between PrPC expression and resistance to cytotoxic agents has now been described in various types of tumors, including breast cancer, gastric cancer, and glioblastoma [reviewed in Ref. (153)]. While the molecular mechanisms underlying the contribution of PrPC to tumor resistance are poorly understood, the disruption of the STI1 binding to PrPC was recently shown to impair glioblastoma growth (150), suggesting that cancer cells may usurp the cytoprotective activity of PrPC. A question that deserves further investigation is whether the presence of PrPC at the surface of cancer cells endows them with properties that enable them to evade the immune response.

Future Prospects

Although the concept presented here allows many pieces of the PrPC puzzle to fall into place, by providing principal physiological roles of PrPC in all tissues, several important questions remain to be answered. For instance, does surface-bound PrPC on patrolling immune cells interact with PrPC or a PrPC-controlled protein complex in tissues and cells, like in the blood–brain barrier tight junctions of the endothelial cells (90) and thereby sense the entrance into an immune-privileged, PrPC-enriched zone; thus contributing to “do no harm” signaling? To what extent does PrPC play part in the maintenance of stem-cell niches, in the proliferation and differentiation of cell lineages derived from the bone marrow and in modulating the development of lymphoid organs? Furthermore, the concept presented here calls for careful scrutiny of the role of PrPC in chronic inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease and various pathologies eliciting inflammation in the brain or other immune-privileged organs.

Besides, in all these questions, we have to examine which of the many PrPC protein/peptide forms are the actual executors of these physiological roles. From the genomic perspective, it would be of great help to understand the gene control of Prnp and whether other immunomodulators, such as TRAIL, Fas/FasL, and IDO, are part of the same expression network controlled by similar transcription factors; and whether there is genetic variation resulting in altered immune-privilege. Our proposed link between PrPC and immunological quiescence opens an exciting new avenue for the study of this protein beyond the chronic diseases of the CNS into the domain of the immune system, the reproductive system, and in sensatory organs. It will encourage the study of PrPC in several inflammatory conditions and cancer.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

MB, AE, and MT were supported by funds from the Research Council of Norway and the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. SM-R is supported by funds from INSERM. JT is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Max Planck Society. WG is supported by a BBSRC UK Strategic Programme Grant to The Roslin Institute.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Professors Lucy Robertson and Trygve Holmøy for critically reading the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Prion diseases and central nervous system degeneration. Clin Res (1987) 35(3):177–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguzzi A, Calella AM. Prions: protein aggregation and infectious diseases. Physiol Rev (2009) 89(4):1105–52. 10.1152/physrev.00006.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okin D, Medzhitov R. Evolution of inflammatory diseases. Curr Biol (2012) 22(17):R733–40. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niederkorn JY. See no evil, hear no evil, do no evil: the lessons of immune privilege. Nat Immunol (2006) 7(4):354–9. 10.1038/ni1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medawar PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin. III. The fate of skin homographs transplanted to the brain, to subcutaneous tissue, and to the anterior chamber of the eye. Br J Exp Pathol (1948) 29(1):58–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson E. A historical perspective on immunological privilege. Immunol Rev (2006) 213(1):12–22. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head JR, Neaves WB, Billingham RE. Immune privilege in the testis. I. Basic parameters of allograft survival. Transplantation (1983) 36(4):423–31. 10.1097/00007890-198310000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galea I, Bechmann I, Perry VH. What is immune privilege (not)? Trends Immunol (2007) 28(1):12–8. 10.1016/j.it.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forrester JV, Xu H, Lambe T, Cornall R. Immune privilege or privileged immunity? Mucosal Immunol (2008) 1(5):372–81. 10.1038/mi.2008.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dürr S, Kindler V. Implication of indolamine 2,3 dioxygenase in the tolerance toward fetuses, tumors, and allografts. J Leukoc Biol (2013) 93(5):681–7. 10.1189/jlb.0712347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson TA, Griffith TS. A vision of cell death: fas ligand and immune privilege 10 years later. Immunol Rev (2006) 213(1):228–38. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips TA, Ni J, Pan G, Ruben SM, Wei Y-F, Pace JL, et al. TRAIL (Apo-2L) and TRAIL receptors in human placentas: implications for immune privilege. J Immunol (1999) 162(10):6053–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahl SM, Wen J, Moutsopoulos N. TGF-β: a mobile purveyor of immune privilege. Immunol Rev (2006) 213(1):213–27. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Connexin 43 is critical to maintain the homeostasis of the blood–testis barrier via its effects on tight junction reassembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107(42):17998–8003. 10.1073/pnas.1007047107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulay A-C, Mazeraud A, Cisternino S, Saubaméa B, Mailly P, Jourdren L, et al. Immune quiescence of the brain is set by astroglial connexin 43. J Neurosci (2015) 35(10):4427–39. 10.1523/jneurosci.2575-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of Foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity (2009) 30(5):636–45. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesebro B, Race R, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Bloom M, Lechner D, et al. Identification of scrapie prion protein-specific mRNA in scrapie-infected and uninfected brain. Nature (1985) 315(6017):331–3. 10.1038/315331a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oesch B, Westaway D, Wälchli M, McKinley MP, Kent SBH, Aebersold R, et al. A cellular gene encodes scrapie PrP 27-30 protein. Cell (1985) 40:735–46. 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90333-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stahl N, Borchelt DR, Hsiao K, Prusiner SB. Scrapie prion protein contains a phosphatidylinositol glycolipid. Cell (1987) 51(2):229–40. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haraguchi T, Fisher S, Olofsson S, Endo T, Groth D, Tarentino A, et al. Asparagine-linked glycosylation of the scrapie and cellular prion proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys (1989) 274(1):1–13. 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90409-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris DA, Huber MT, van Dijken P, Shyng SL, Chait BT, Wang R. Processing of a cellular prion protein: identification of N- and C-terminal cleavage sites. Biochemistry (1993) 32(4):1009–16. 10.1021/bi00055a003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SG, Teplow DB, Parchi P, Teller JK, Gambetti P, Autilio-Gambetti L. Truncated forms of the human prion protein in normal brain and in prion diseases. J Biol Chem (1995) 270(32):19173–80. 10.1074/jbc.270.32.19173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald AJ, Millhauser GL. PrP overdrive: does inhibition of alpha-cleavage contribute to PrP(C) toxicity and prion disease? Prion (2014) 8(2): 183–191. 10.4161/pri.28796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walmsley AR, Watt NT, Taylor DR, Perera WS, Hooper NM. Alpha-cleavage of the prion protein occurs in a late compartment of the secretory pathway and is independent of lipid rafts. Mol Cell Neurosci (2009) 40(2):242–8. 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altmeppen HC, Prox J, Puig B, Kluth MA, Bernreuther C, Thurm D, et al. Lack of a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase ADAM10 leads to intracellular accumulation and loss of shedding of the cellular prion protein in vivo. Mol Neurodegener (2011) 6:36. 10.1186/1750-1326-6-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altmeppen HC, Prox J, Krasemann S, Puig B, Kruszewski K, Dohler F, et al. The sheddase ADAM10 is a potent modulator of prion disease. eLife (2015) 4:1–28. 10.7554/eLife.04260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mays CE, Coomaraswamy J, Watts JC, Yang J, Ko KW, Strome B, et al. Endoproteolytic processing of the mammalian prion glycoprotein family. FEBS J (2014) 281(3):862–76. 10.1111/febs.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehsani S, Salehzadeh A, Huo H, Reginold W, Pocanschi CL, Ren H, et al. LIV-1 ZIP ectodomain shedding in prion-infected mice resembles cellular response to transition metal starvation. J Mol Biol (2012) 422(4):556–74. 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell L, Gill AC, McGovern G, Jalland CM, Hopkins J, Tranulis MA, et al. The PrP(C) C1 fragment derived from the ovine A136R154R171PRNP allele is highly abundant in sheep brain and inhibits fibrillisation of full-length PrP(C) protein in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta (2013) 1832(6):826–36. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bremer J, Baumann F, Tiberi C, Wessig C, Fischer H, Schwarz P, et al. Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance. Nat Neurosci (2010) 13(3):310–8. 10.1038/nn.2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donne DG, Viles JH, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, James TL, Cohen FE, et al. Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein PrP(29-231): the N terminus is highly flexible. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1997) 94(25):13452–7. 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Billeter M, Glockshuber R, Wuthrich K. NMR structure of the mouse prion protein domain PrP(121-321). Nature (1996) 382(6587):180–2. 10.1038/382180a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Glockshuber R, Wuthrich K. NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein, mPrP(23-231). FEBS Lett (1997) 413(2):282–8. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00920-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim Biophys Acta (2010) 1804(6):1231–64. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuxreiter M, Tompa P. Fuzzy complexes: a more stochastic view of protein function. Adv Exp Med Biol (2012) 725:1–14. 10.1007/978-1-4614-0659-4_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2015) 16(1):18–29. 10.1038/nrm3920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calzolai L, Lysek DA, Perez DR, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Prion protein NMR structures of chickens, turtles, and frogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(3):651–5. 10.1073/pnas.0408939102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown CJ, Takayama S, Campen AM, Vise P, Marshall TW, Oldfield CJ, et al. Evolutionary rate heterogeneity in proteins with long disordered regions. J Mol Evol (2002) 55(1):104–10. 10.1007/s00239-001-2309-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown CJ, Johnson AK, Daughdrill GW. Comparing models of evolution for ordered and disordered proteins. Mol Biol Evol (2010) 27(3):609–21. 10.1093/molbev/msp277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Walchli M, Groth DF, et al. Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell (1986) 46(3):417–28. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kretzschmar HA, Stowring LE, Westaway D, Stubblebine WH, Prusiner SB, Dearmond SJ. Molecular cloning of a human prion protein cDNA. DNA (1986) 5(4):315–24. 10.1089/dna.1986.5.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao YC, Lebo RV, Clawson GA, Smuckler EA. Human prion protein cDNA: molecular cloning, chromosomal mapping, and biological implications. Science (1986) 233(4761):364–7. 10.1126/science.3014653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao YC, Tokes Z, Lim E, Lackey A, Woo CH, Button JD, et al. Cloning of rat “prion-related protein” cDNA. Lab Invest (1987) 57(4):370–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westaway D, Goodman PA, Mirenda CA, McKinley MP, Carlson GA, Prusiner SB. Distinct prion proteins in short and long scrapie incubation period mice. Cell (1987) 51(4):651–62. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90134-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Foster JD, Salbaum JM, Beyreuther K, Hope J. Two alleles of a neural protein gene linked to scrapie in sheep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1990) 87(7):2476–80. 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart P, Campbell L, Skogtvedt S, Griffin KA, Arnemo JM, Tryland M, et al. Genetic predictions of prion disease susceptibility in carnivore species based on variability of the prion gene coding region. PLoS One (2012) 7(12):e50623. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris DA, Falls DL, Johnson FA, Fischbach GD. A prion-like protein from chicken brain copurifies with an acetylcholine receptor-inducing activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1991) 88(17):7664–8. 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gabriel JM, Oesch B, Kretzschmar H, Scott M, Prusiner SB. Molecular cloning of a candidate chicken prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1992) 89(19):9097–101. 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wopfner F, Weidenhöfer G, Schneider R, von Brunn A, Gilch S, Schwarz TF, et al. Analysis of 27 mammalian and 9 avian PrPs reveals high conservation of flexible regions of the prion protein. J Mol Biol (1999) 289(5):1163–78. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simonic T, Duga S, Strumbo B, Asselta R, Ceciliani F, Ronchi S. cDNA cloning of turtle prion protein. FEBS Lett (2000) 469(1):33–8. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01232-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strumbo B, Ronchi S, Bolis LC, Simonic T. Molecular cloning of the cDNA coding for Xenopus laevis prion protein. FEBS Lett (2001) 508(2):170–4. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03027-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haigh CL, Marom SY, Collins SJ. Copper, endoproteolytic processing of the prion protein and cell signalling. Front Biosci (2010) 15:1086–104. 10.2741/3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watt NT, Taylor DR, Kerrigan TL, Griffiths HH, Rushworth JV, Whitehouse IJ, et al. Prion protein facilitates uptake of zinc into neuronal cells. Nat Commun (2012) 3:1134. 10.1038/ncomms2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viles JH, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Goodin DB, Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Copper binding to the prion protein: structural implications of four identical cooperative binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96(5):2042–7. 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bounhar Y, Zhang Y, Goodyer CG, LeBlanc A. Prion protein protects human neurons against Bax-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem (1997) 276:39145–9. 10.1074/jbc.C100443200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atarashi R, Nishida N, Shigematsu K, Goto S, Kondo T, Sakaguchi S, et al. Deletion of N-terminal residues 23-88 from prion protein (PrP) abrogates the potential to rescue PrP-deficient mice from PrP-like protein/doppel-induced neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(31):28944–9. 10.1074/jbc.M303655200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drisaldi B, Coomaraswamy J, Mastrangelo P, Strome B, Yang J, Watts JC, et al. Genetic mapping of activity determinants within cellular prion proteins: N-terminal modules in PrPC offset pro-apoptotic activity of the doppel helix B/B’ region. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(53):55443–54. 10.1074/jbc.M404794200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rambold AS, Müller V, Ron U, Ben-Tal N, Winklhofer KF, Tatzelt J. Stress-protective activity of prion protein is corrupted by scrapie-prions. EMBO J (2008) 27:1974–84. 10.1038/emboj.2008.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitteregger G, Vosko M, Krebs B, Xiang W, Kohlmannsperger V, Nolting S, et al. The role of the octarepeat region in neuroprotective function of the cellular prion protein. Brain Pathol (2007) 17(2):174–83. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00061.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Resenberger UK, Harmeier A, Woerner AC, Goodman JL, Muller V, Krishnan R, et al. The cellular prion protein mediates neurotoxic signalling of beta-sheet-rich conformers independent of prion replication. EMBO J (2011) 30(10):2057–70. 10.1038/emboj.2011.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vey M, Pilkuhn S, Wille H, Nixon R, DeArmond SJ, Smart EJ, et al. Subcellular colocalization of the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in caveolae-like membranous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1996) 93(25):14945–9. 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hooper NM, Taylor DR, Watt NT. Mechanism of the metal-mediated endocytosis of the prion protein. Biochem Soc Trans (2008) 36(Pt 6):1272–6. 10.1042/BST0361272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mani K, Cheng F, Havsmark B, Jonsson M, Belting M, Fransson LA. Prion, amyloid beta-derived Cu(II) ions, or free Zn(II) ions support S-nitroso-dependent autocleavage of glypican-1 heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(40):38956–65. 10.1074/jbc.M300394200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmitt-Ulms G, Hansen K, Liu J, Cowdrey C, Yang J, DeArmond SJ, et al. Time-controlled transcardiac perfusion cross-linking for the study of protein interactions in complex tissues. Nat Biotechnol (2004) 22(6):724–31. 10.1038/nbt969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taylor DR, Hooper NM. Role of lipid rafts in the processing of the pathogenic prion and Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol (2007) 18(5):638–48. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaiser DM, Acharya M, Leighton PL, Wang H, Daude N, Wohlgemuth S, et al. Amyloid beta precursor protein and prion protein have a conserved interaction affecting cell adhesion and CNS development. PLoS One (2012) 7(12):e51305. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mouillet-Richard S, Ermonval M, Chebassier C, Laplanche JL, Lehmann S, Launay JM, et al. Signal transduction through prion protein. Science (2000) 289(5486):1925–8. 10.1126/science.289.5486.1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Watts JC, Huo H, Bai Y, Ehsani S, Jeon AH, Shi T, et al. Interactome analyses identify ties of PrP and its mammalian paralogs to oligomannosidic N-glycans and endoplasmic reticulum-derived chaperones. PLoS Pathog (2009) 5(10):e1000608. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hernandez-Rapp J, Martin-Lanneree S, Hirsch TZ, Pradines E, Alleaume-Butaux A, Schneider B, et al. A PrP(C)-caveolin-Lyn complex negatively controls neuronal GSK3beta and serotonin 1B receptor. Sci Rep (2014) 4:4881. 10.1038/srep04881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hajj GN, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Veiga SS, da Silveira RB, Santos TG, et al. Cellular prion protein interaction with vitronectin supports axonal growth and is compensated by integrins. J Cell Sci (2007) 120(Pt 11):1915–26. 10.1242/jcs.03459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Graner E, Mercadante AF, Zanata SM, Forlenza OV, Cabral AL, Veiga SS, et al. Cellular prion protein binds laminin and mediates neuritogenesis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res (2000) 76(1):85–92. 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00334-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zanata SM, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Hajj GN, Chiarini LB, Nomizo R, et al. Stress-inducible protein 1 is a cell surface ligand for cellular prion that triggers neuroprotection. EMBO J (2002) 21(13):3307–16. 10.1093/emboj/cdf325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mattei V, Garofalo T, Misasi R, Circella A, Manganelli V, Lucania G, et al. Prion protein is a component of the multimolecular signaling complex involved in T cell activation. FEBS Lett (2004) 560(1–3):14–8. 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wurm S, Paar C, Sonnleitner A, Sonnleitner M, Hoglinger O, Romanin C, et al. Co-localization of CD3 and prion protein in Jurkat lymphocytes after hypothermal stimulation. FEBS Lett (2004) 566(1–3):121–5. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ballerini C, Gourdain P, Bachy V, Blanchard N, Levavasseur E, Grégoire S, et al. Functional implication of cellular prion protein in antigen-driven interactions between T cells and dendritic cells. J Immunol (2006) 176(12):7254–62. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paar C, Wurm S, Pfarr W, Sonnleitner A, Wechselberger C. Prion protein resides in membrane microclusters of the immunological synapse during lymphocyte activation. Eur J Cell Biol (2007) 86(5):253–64. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beland M, Roucou X. The prion protein unstructured N-terminal region is a broad-spectrum molecular sensor with diverse and contrasting potential functions. J Neurochem (2012) 120(6):853–68. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature (2009) 457(7233):1128–32. 10.1038/nature07761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guillot-Sestier MV, Sunyach C, Druon C, Scarzello S, Checler F. The alpha-secretase-derived N-terminal product of cellular prion, N1, displays neuroprotective function in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(51):35973–86. 10.1074/jbc.M109.051086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Resenberger UK, Winklhofer KF, Tatzelt J. Neuroprotective and neurotoxic signaling by the prion protein. Top Curr Chem (2011) 305:101–19. 10.1007/128_2011_160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beland M, Motard J, Barbarin A, Roucou X. PrPC homodimerization stimulates the production of PrPC cleaved fragments PrPN1 and PrPC1. J Neurosci (2012) 32(38):13255–63. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2236-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nieznanski K, Choi JK, Chen S, Surewicz K, Surewicz WK. Soluble prion protein inhibits amyloid-beta (Abeta) fibrillization and toxicity. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(40):33104–8. 10.1074/jbc.C112.400614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fluharty BR, Biasini E, Stravalaci M, Sclip A, Diomede L, Balducci C, et al. An N-terminal fragment of the prion protein binds to amyloid-beta oligomers and inhibits their neurotoxicity in vivo. J Biol Chem (2013) 288(11):7857–66. 10.1074/jbc.M112.423954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beland M, Bedard M, Tremblay G, Lavigne P, Roucou X. Abeta induces its own prion protein N-terminal fragment (PrPN1)-mediated neutralization in amorphous aggregates. Neurobiol Aging (2014) 35(7):1537–48. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taraboulos A, Jendroska K, Serban D, Yang SL, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Regional mapping of prion proteins in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1992) 89(16):7620–4. 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moser M, Colello RJ, Pott U, Oesch B. Developmental expression of the prion protein gene in glial cells. Neuron (1995) 14(3):509–17. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90307-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertuchi FR, Bourgeon DMG, Landemberger MC, Martins VR, Cerchiaro G. PrPC displays an essential protective role from oxidative stress in an astrocyte cell line derived from PrPC knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2012) 418(1):27–32. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tanji K, Saeki K, Matsumoto Y, Takeda M, Hirasawa K, Doi K, et al. Analysis of PrPc mRNA by in situ hybridization on brain, placenta, uterus and testis of rats. Intervirology (1995) 38:309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Prion (PrPC) expression in ovine uteroplacental tissues increases after estrogen-treatment in ovariectomized (OVX) ewes and during early pregnancy. Reproduction (2014) 148(1):1–10. 10.1530/REP-13-0548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Viegas P, Chaverot N, Enslen H, Perrière N, Couraud P-O, Cazaubon S. Junctional expression of the prion protein PrPC by brain endothelial cells: a role in trans-endothelial migration of human monocytes. J Cell Sci (2006) 119(22):4634–43. 10.1242/jcs.03222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pflanzner T, Petsch B, Andre-Dohmen B, Muller-Schiffmann A, Tschickardt S, Weggen S, et al. Cellular prion protein participates in amyloid-beta transcytosis across the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab (2012) 32(4):628–32. 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci (2006) 7(1):41–53. 10.1038/nrn1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown DR, Besinger A, Herms JW, Kretzschmar HA. Microglial expression of the prion protein. Neuroreport (1998) 9(7):1425–9. 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu J, Zhao D, Liu C, Ding T, Yang L, Yin X, et al. Prion protein participates in the protection of mice from lipopolysaccharide infection by regulating the inflammatory process. J Mol Neurosci (2015) 55(1):279–87. 10.1007/s12031-014-0319-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang CC, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Lodish HF. Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103(7):2184–9. 10.1073/pnas.0510577103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lopes MH, Santos TG. Prion potency in stem cells biology. Prion (2012) 6(2):142–6. 10.4161/pri.19035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martin-Lannerée S, Hirsch TZ, Hernandez-Rapp J, Halliez S, Vilotte J-L, Launay J-M, et al. PrP(C) from stem cells to cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol (2014) 2:55. 10.3389/fcell.2014.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fujisaki J, Wu J, Carlson AL, Silberstein L, Putheti P, Larocca R, et al. In vivo imaging of Tregs providing immune privilege to the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature (2011) 474(7350):216–9. 10.1038/nature10160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Isaacs JD, Garden OA, Kaur G, Collinge J, Jackson GS, Altmann DM. The cellular prion protein is preferentially expressed by CD4(+) CD25(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Immunology (2008) 125(3):313–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02853.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cashman NR, Loertscher R, Nalbantoglu J, Shaw I, Kascsak RJ, Bolton DC, et al. Cellular isoform of the scrapie agent protein participates in lymphocyte activation. Cell (1990) 61(1):185–92. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90225-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mabbott NA, Brown KL, Manson J, Bruce ME. T-lymphocyte activation and the cellular form of the prion protein. Immunology (1997) 92(2):161–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li R, Liu D, Zanusso G, Liu T, Fayen JD, Huang JH, et al. The expression and potential function of cellular prion protein in human lymphocytes. Cell Immunol (2001) 207(1):49–58. 10.1006/cimm.2000.1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Burthem J, Urban B, Pain A, Roberts DJ. The normal cellular prion protein is strongly expressed by myeloid dendritic cells. Blood (2001) 98(13):3733–8. 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dodelet VC, Cashman NR. Prion protein expression in human leukocyte differentiation. Blood (1998) 91(5):1556–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dürig J, Giese A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Rosenthal C, Schmücker U, Bieschke J, et al. Differential constitutive and activation-dependent expression of prion protein in human peripheral blood leucocytes. Br J Haematol (2000) 108(3):488–95. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Isaacs JD, Jackson GS, Altmann DM. The role of the cellular prion protein in the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol (2006) 146(1):1–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03194.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mariante RM, Nóbrega A, Martins RAP, Areal RB, Bellio M, Linden R. Neuroimmunoendocrine regulation of the prion protein in neutrophils. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(42):35506–15. 10.1074/jbc.M112.394924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Haddon DJ, Hughes MR, Antignano F, Westaway D, Cashman NR, McNagny KM. Prion protein expression and release by mast cells after activation. J Infect Dis (2009) 200(5):827–31. 10.1086/605022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bueler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H-P, DeArmond SJ, et al. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature (1992) 356(6370):577–82. 10.1038/356577a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, Hope J. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol (1994) 8(2–3):121–7. 10.1007/BF02780662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baumann F, Tolnay M, Brabeck C, Pahnke J, Kloz U, Niemann HH, et al. Lethal recessive myelin toxicity of prion protein lacking its central domain. EMBO J (2007) 26(2):538–47. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tobler I, Gaus SE, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rulicke T, et al. Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature (1996) 380(6575):639–42. 10.1038/380639a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Walz R, Amaral OB, Rockenbach IC, Roesler R, Izquierdo I, Cavalheiro EA, et al. Increased sensitivity to seizures in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Epilepsia (1999) 40(12):1679–82. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MAM, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol Rev (2008) 88(2):673–728. 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Richt JA, Kasinathan P, Hamir AN, Castilla J, Sathiyaseelan T, Vargas F, et al. Production of cattle lacking prion protein. Nat Biotechnol (2007) 25(1):132. 10.1038/nbt1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Benestad S, Austbo L, Tranulis M, Espenes A, Olsaker I. Healthy goats naturally devoid of prion protein. Vet Res (2012) 43(1):87. 10.1186/1297-9716-43-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Reiten MR, Bakkebo MK, Brun-Hansen H, Lewandowska-Sabat AM, Olsaker I, Tranulis MA, et al. Hematological shift in goat kids naturally devoid of prion protein. Front Cell Dev Biol (2015) 3:44. 10.3389/fcell.2015.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Onodera T, Sakudo A, Tsubone H, Itohara S. Review of studies that have used knockout mice to assess normal function of prion protein under immunological or pathophysiological stress. Microbiol Immunol (2014) 58(7):361–74. 10.1111/1348-0421.12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McLennan NF, Brennan PM, McNeill A, Davies I, Fotheringham A, Rennison KA, et al. Prion protein accumulation and neuroprotection in hypoxic brain damage. Am J Pathol (2004) 165(1):227–35. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63291-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Spudich A, Frigg R, Kilic E, Kilic Ü, Oesch B, Raeber A, et al. Aggravation of ischemic brain injury by prion protein deficiency: role of ERK-1/-2 and STAT-1. Neurobiol Dis (2005) 20(2):442–9. 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weise J, Sandau R, Schwarting S, Crome O, Wrede A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, et al. Deletion of cellular prion protein results in reduced Akt activation, enhanced postischemic caspase-3 activation, and exacerbation of ischemic brain injury. Stroke (2006) 37(5):1296–300. 10.1161/01.STR.0000217262.03192.d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shyu W-C, Lin S-Z, Chiang M-F, Ding D-C, Li K-W, Chen S-F, et al. Overexpression of PrPC by adenovirus-mediated gene targeting reduces ischemic injury in a stroke rat model. J Neurosci (2005) 25(39):8967–77. 10.1523/jneurosci.1115-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hoshino S, Inoue K, Yokoyama T, Kobayashi S, Asakura T, Teramoto A, et al. Prions prevent brain damage after experimental brain injury: a preliminary report. Acta Neurochir Suppl (2003) 86:297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Marciano PG, Brettschneider J, Manduchi E, Davis JE, Eastman S, Raghupathi R, et al. Neuron-specific mRNA complexity responses during hippocampal apoptosis after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci (2004) 24(12):2866–76. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5051-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tsutsui S, Hahn JN, Johnson TA, Ali Z, Jirik FR. Absence of the cellular prion protein exacerbates and prolongs neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol (2008) 173(4):1029–41. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gourdain P, Ballerini C, Nicot AB, Carnaud C. Exacerbation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in prion protein (PrPc)-null mice: evidence for a critical role of the central nervous system. J Neuroinflammation (2012) 9:25. 10.1186/1742-2094-9-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Martin GR, Keenan CM, Sharkey KA, Jirik FR. Endogenous prion protein attenuates experimentally induced colitis. Am J Pathol (2011) 179(5):2290–301. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nasu-Nishimura Y, Taniuchi Y, Nishimura T, Sakudo A, Nakajima K, Ano Y, et al. Cellular prion protein prevents brain damage after encephalomyocarditis virus infection in mice. Arch Virol (2008) 153(6):1007–12. 10.1007/s00705-008-0086-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Murphy AC, Lalor SJ, Lynch MA, Mills KH. Infiltration of Th1 and Th17 cells and activation of microglia in the CNS during the course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav Immun (2010) 24(4):641–51. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hu W, Nessler S, Hemmer B, Eagar TN, Kane LP, Leliveld SR, et al. Pharmacological prion protein silencing accelerates central nervous system autoimmune disease via T cell receptor signalling. Brain (2010) 133(Pt 2):375–88. 10.1093/brain/awp298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mitsios N, Saka M, Krupinski J, Pennucci R, Sanfeliu C, Miguel Turu M, et al. Cellular prion protein is increased in the plasma and peri-infarcted brain tissue after acute stroke. J Neurosci Res (2007) 85(3):602–11. 10.1002/jnr.21142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hirsch TZ, Hernandez-Rapp J, Martin-Lanneree S, Launay JM, Mouillet-Richard S. PrP(C) signalling in neurons: from basics to clinical challenges. Biochimie (2014) 104:2–11. 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Martins VR, Graner E, Garcia-Abreu J, de Souza SJ, Mercadante AF, Veiga SS, et al. Complementary hydropathy identifies a cellular prion protein receptor. Nat Med (1997) 3(12):1376–82. 10.1038/nm1297-1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J (2002) 21(13):3317–26. 10.1093/emboj/cdf324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lopes MH, Hajj GN, Muras AG, Mancini GL, Castro RM, Ribeiro KC, et al. Interaction of cellular prion and stress-inducible protein 1 promotes neuritogenesis and neuroprotection by distinct signaling pathways. J Neurosci (2005) 25(49):11330–9. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2313-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Roffe M, Beraldo FH, Bester R, Nunziante M, Bach C, Mancini G, et al. Prion protein interaction with stress-inducible protein 1 enhances neuronal protein synthesis via mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107(29):13147–52. 10.1073/pnas.1000784107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol (2001) 65(4):391–426. 10.1016/S0301-0082(01)00011-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hajj GN, Arantes CP, Dias MV, Roffe M, Costa-Silva B, Lopes MH, et al. The unconventional secretion of stress-inducible protein 1 by a heterogeneous population of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci (2013) 70(17):3211–27. 10.1007/s00018-013-1328-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Arantes C, Nomizo R, Lopes MH, Hajj GN, Lima FR, Martins VR. Prion protein and its ligand stress inducible protein 1 regulate astrocyte development. Glia (2009) 57(13):1439–49. 10.1002/glia.20861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Beraldo FH, Soares IN, Goncalves DF, Fan J, Thomas AA, Santos TG, et al. Stress-inducible phosphoprotein 1 has unique cochaperone activity during development and regulates cellular response to ischemia via the prion protein. FASEB J (2013) 27(9):3594–607. 10.1096/fj.13-232280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lee SD, Lai TW, Lin SZ, Lin CH, Hsu YH, Li CY, et al. Role of stress-inducible protein-1 in recruitment of bone marrow derived cells into the ischemic brains. EMBO Mol Med (2013) 5(8):1227–46. 10.1002/emmm.201202258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pradines E, Loubet D, Schneider B, Launay JM, Kellermann O, Mouillet-Richard S. CREB-dependent gene regulation by prion protein: impact on MMP-9 and beta-dystroglycan. Cell Signal (2008) 20(11):2050–8. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Svedin P, Hagberg H, Savman K, Zhu C, Mallard C. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out protects the immature brain after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. J Neurosci (2007) 27(7):1511–8. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bechmann I, Galea I, Perry VH. What is the blood-brain barrier (not)? Trends Immunol (2007) 28(1):5–11. 10.1016/j.it.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tremblay P, Bouzamondo-Bernstein E, Heinrich C, Prusiner SB, DeArmond SJ. Developmental expression of PrP in the post-implantation embryo. Brain Res (2007) 1139:60–7. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Tsai CL, Tsai CN, Lin CY, Chen HW, Lee YS, Chao A, et al. Secreted stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 activates the ALK2-SMAD signaling pathways and promotes cell proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Cell Rep (2012) 2(2):283–93. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gu Z, Reynolds EM, Song J, Lei H, Feijen A, Yu L, et al. The type I serine/threonine kinase receptor ActRIA (ALK2) is required for gastrulation of the mouse embryo. Development (1999) 126(11):2551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Makzhami S, Passet B, Halliez S, Castille J, Moazami-Goudarzi K, Duchesne A, et al. The prion protein family: a view from the placenta. Front Cell Dev Biol (2014) 2:35. 10.3389/fcell.2014.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Santos TG, Silva IR, Costa-Silva B, Lepique AP, Martins VR, Lopes MH. Enhanced neural progenitor/stem cells self-renewal via the interaction of stress-inducible protein 1 with the prion protein. Stem Cells (2011) 29(7):1126–36. 10.1002/stem.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lopes MH, Santos TG, Rodrigues BR, Queiroz-Hazarbassanov N, Cunha IW, Wasilewska-Sampaio AP, et al. Disruption of prion protein-HOP engagement impairs glioblastoma growth and cognitive decline and improves overall survival. Oncogene (2014) 34(25):3305–14. 10.1038/onc.2014.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Schatton T, Frank MH. Antitumor immunity and cancer stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2009) 1176:154–69. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04568.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Diarra-Mehrpour M, Arrabal S, Jalil A, Pinson X, Gaudin C, Pietu G, et al. Prion protein prevents human breast carcinoma cell line from tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced cell death. Cancer Res (2004) 64(2):719–27. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mehrpour M, Codogno P. Prion protein: from physiology to cancer biology. Cancer Lett (2010) 290(1):1–23. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]