Abstract

Moderate hyperoxic exposure in preterm infants contributes to subsequent airway dysfunction and to risk of developing recurrent wheeze and asthma. The regulatory mechanisms that can contribute to hyperoxia-induced airway dysfunction are still under investigation. Recent studies in mice show that hyperoxia increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a growth factor that increases airway smooth muscle (ASM) proliferation and contractility. We assessed the mechanisms underlying effects of moderate hyperoxia (50% O2) on BDNF expression and secretion in developing human ASM. Hyperoxia increased BDNF secretion, but did not alter endogenous BDNF mRNA or intracellular protein levels. Exposure to hyperoxia significantly increased [Ca2+]i responses to histamine, an effect blunted by the BDNF chelator TrkB-Fc. Hyperoxia also increased ASM cAMP levels, associated with reduced PDE4 activity, but did not alter protein kinase A (PKA) activity or adenylyl cyclase mRNA levels. However, 50% O2 increased expression of Epac2, which is activated by cAMP and can regulate protein secretion. Silencing RNA studies indicated that Epac2, but not Epac1, is important for hyperoxia-induced BDNF secretion, while PKA inhibition did not influence BDNF secretion. In turn, BDNF had autocrine effects of enhancing ASM cAMP levels, an effect inhibited by TrkB and BDNF siRNAs. Together, these novel studies suggest that hyperoxia can modulate BDNF secretion, via cAMP-mediated Epac2 activation in ASM, resulting in a positive feedback effect of BDNF-mediated elevation in cAMP levels. The potential functional role of this pathway is to sustain BDNF secretion following hyperoxic stimulus, leading to enhanced ASM contractility and proliferation.

Keywords: Lung, Development, Hyperoxia, Neurotrophin, Cyclic Nucleotide, Epac

Introduction

In spite of significant changes in neonatal intensive care clinical practice for respiratory support of premature infants, such as limiting the extent of supplemental oxygen (moderate hyperoxia) and minimizing mechanical ventilation, in order to lessen incidence of lung injury and bronchopulmonary dysplasia [1–5], the major short-term and long-term problem for survivors of this critical period remains chronic airway disease [6–10], manifested as wheezing, asthma, and increased risk of respiratory infection. Indeed, regardless of other lung changes, former preterm infants continue to be at high risk for airway hyperreactivity throughout infancy and childhood [11–15], suggesting that beyond alveolar and vascular targets, factors such as moderate hyperoxia affect the structure and function of the developing tracheobronchial tree. However, the mechanisms by which hyperoxia affects the growing airway are still under investigation.

Enhanced airway tone and reactivity involve increased bronchoconstriction mediated by greater [Ca2+]i and force responses of airway smooth muscle (ASM) [16–19], as well as by airway remodeling and wall thickening mediated in part by increased ASM proliferation [16, 20–22]. In this regard, an emerging theme is the role of growth factors such as neurotrophins (nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF) that are more known for their role in the nervous system, but are increasingly recognized to be involved in non-neuronal tissues [23–25]. In adult airways, we and others have reported that BDNF and its receptors (TrkB, p75NTR) are expressed in ASM [26, 27], suggesting that the airway is both source and target for BDNF, and that BDNF enhances ASM [Ca2+]i and contractility as well as ASM cell proliferation [27, 28]. These data suggest a prominent role for BDNF in local control of airway structure and function. However, the role of BDNF in developing airway is still emerging [23, 29, 30]. In this regard, we have previously shown that moderate hyperoxia increases intracellular ASM BDNF, and enhances TrkB-mediated pro-contractile effects of BDNF on ASM, suggesting that BDNF is a key player in hyperoxia-induced increase of tone and reactivity of developing airway. What is not known are the mechanisms underlying regulation of BDNF by hyperoxia, and its consequences for airway tone and reactivity in this setting.

While it is likely that BDNF generation and secretion is modulated by a number of factors, for endogenous BDNF to have autocrine effects, it must be secreted. In this regard, data in neurons show that post-transcriptionally, pro-BDNF is cleaved by proteases to form a mature product, while secretory vesicles facilitate both pro- and mature BDNF release [31, 32]. However, in ASM, regulation of BDNF expression and secretion are not well defined. Among the several factors that may regulate BDNF at least in other cell types such as neurons, two pathways particularly important to airway physiology are the cyclic nucleotides cGMP [33–35] and cAMP [36–39]. Previous studies in neurons [40–42] and endothelium [43, 44] consistently show that cAMP regulates increases in BDNF secretion. In airways, elevated levels of cAMP is associated with bronchodilation, but limited data in adult airways suggest that BDNF actually enhances airway [Ca2+]i and contractility. Furthermore, limited data suggest that hyperoxia can increase cAMP, but again hyperoxia also increases [Ca2+]i. This raises the question regarding the links between BDNF secretion, cAMP and [Ca2+]i regulation in the context of hyperoxia. In the present study, we examined the role of cAMP in regulation of BDNF in the developing airway, focusing on the potential roles for phosphodiesterases (PDEs) and PKA-independent guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac [45–50], which can promote activation of secretory proteins that modulate exocytosis [51, 52].

Methods

Isolation of Human Fetal Airway Smooth Muscle Cells

The techniques have been previously described [53]. Briefly, ASM cells were enzymatically dissociated from tracheobronchial tissue of de-identified non-viable 18–22 week gestation fetuses (Dr. Pandya or from Novogenix Los Angeles, CA; protocols approved and considered exempt by the Mayo Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committees in the UK). Persistence of smooth muscle phenotype was verified by expression of smooth muscle myosin and actin and Ca2+ regulatory proteins, but lack of expression of E-cadherin (epithelial marker) [53, 54].

Cell treatments

Fetal ASM were incubated at humidified 95% air/5% CO2 in DMEM/F12 phenol red free medium, 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and grown to 80% confluence prior to experiments. Cells were serum starved in 0.5% FBS medium for 24 h prior to all studies. The next day, fresh 0.5% FBS media was added to plates and cells were treated with media only, 100 µM dibutyl-cAMP (cell-permeant cAMP analog; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), 10µM Roflumilast (PDE4 inhibitor; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), 0.5 µM KT5720 (PKA inhibitor; EMD Millipore), or 10 µM 8-CPT-2-O-Me-cAMP-AM (Epac-selective cAMP analog; Tocris Bioscience, U.K.) for 30 min and then exposed to room air (21% O2) or hyperoxia (50 % O2) for 8, 12, 24, or 48 h. Oxygen levels were monitored using a MiniOx 3000 oxygen monitor (MSA Medical Products, Pittsburgh, PA). Media or cell lysates were collected and stored at −80°C until analyses.

[Ca2+]i imaging

In gas permeable 24 well plates (Coy Laboratories), fetal ASM cells were incubated with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM for 60 min at room temperature, washed, and cells imaged (20 cells/field) in real time using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U fluorescent microscope (20× Plan Fluor objective lens) and imaging system software (MetaFluor; Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). Baseline [Ca2+]i was established for 20s followed by addition of histamine (10µM) and responses recorded for 2 min. Responses were calculated by comparing the ratio of peak fluorescence to the average baseline fluorescence.

Transfection with siRNAs

Fetal ASM cells were transfected with 20nM (final concentration) siRNA against EPAC1, EPAC2, BDNF or TrkB (GE Dharmacon), via manufacturer protocols, under serum- and antibiotic-free conditions using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 24 h followed by 48 h normoxia or hyperoxia exposure in serum-free medium. Treatment with Lipofectamine alone and transfection with scrambled (non-targeting RNA) served as controls.

ELISA

BDNF levels were measured in media using human BDNF Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Flexstation3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Comparison to a standard curve was used to determine BDNF concentration in samples.

Measurement of cAMP levels

Cells were treated in the presence of 10 µM IBMX (phosphodiesterase inhibitor) with media only, 10 nM BDNF, or 1 µg/mL TrkB-Fc during exposure to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Following exposures, 5% (final concentration) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was immediately added to media and subsequently extracted by adding 5× volume of water saturated ether to media. Samples were vortexed, layers allowed to separate and the top layer (ether layer) was removed with the process repeated twice more for a total of three extractions. Cyclic AMP levels in media were measured by ELISA following the manufacturer’s protocol (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA) for acetylated samples. Absorbance at 410 nm was measured and cAMP concentration in media determined by comparison to a standard curve.

Phosphodiesterase Activity

PDE4 activity was measured using a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, fetal ASM cells were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h and harvested using the supplied PDE assay buffer containing 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Extracts containing 2.5 µg protein were then incubated with 3’, 5’-cAMP and 5’-nucleotidase (200 µM and 50 kU final concentrations respectively) in the presence or absence of a PDE4 inhibitor, 10 µM Roflumilast, for 60 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated using the supplied BIOMOL GREEN reagent and, after 30 min for color development, OD determined at 620nm. PDE4 activity was determined by comparing the amount of phosphate released from samples incubated with or without Roflumilast and normalized to the amount of protein in cell lysate.

Protein Kinase A activity

Cells were untreated or incubated with 100 µM dibutyl-cAMP (db-cAMP) during exposure to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Cell lysates were collected and PKA activity was measured using a solid phase ELISA-based kit (Enzo Life Sciences) following manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured. To calculate relative PKA activity, OD values were divided by protein concentrations. Values were normalized to untreated and 21% O2 control. To confirm the inhibitory effect of KT5720, fetal ASM cells were incubated with 10 µM isoproterenol or 100 µM 8-Br-cAMP for 30 min in the presence or absence of 0.5 µM KT5720. Cell lysates collected and probed for PKA activity to confirm effectiveness of inhibitor (data not shown).

Real time PCR

RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and complementary DNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For qRT-PCR reactions, cDNA, forward and reverse primers, and SYBR green master mix (Roche), were amplified with using LC480 Light Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) for 60 cycles. Primer sequences are summarized in Table 1. The housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used to normalize Ct values.

Table 1.

Quantitative Real Time PCR primer sequences

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Adenylyl Cyclase 3 | TTCAACCCTGGGCTCAATGG | TCTACGTGGCGGGAGAAGTA |

| Adenylyl Cyclase 4 | CAATCCGGGTTTGAGGGAGG | TGGCAATCCCGTCTCCTTTTT |

| Adenylyl Cyclase 6 | TAGCTTGTCAGTGGGAAGTGC | ACATGTTGCTGGTAGGGAAGG |

| Adenylyl Cyclase 7 | GGGACGCTCTGCACTATCTC | ACTTGGAAAGGCATCAGGGG |

| Adenylyl Cyclase 9 | CATAAAAACAGCACCAAGGCT | AGTCTGACTGTTGGTGAGCTT |

| BDNF | ATACTTTGGTTGCATGAAGGCTGCCC | CGAACTTTCTGGTCCTCATCC AACAG |

| GAPDH | AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATT | AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATT |

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were harvested using standard techniques (cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors). Protein was separated by SDS PAGE using a 4–15% Tris-HCl gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo rapid transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primary antibodies used include BDNF, Epac1, Epac2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Membranes were imaged on a Li-Cor OdysseyXL system and densitometry was quantified with Image Studio software. Protein blots were normalized to β-actin.

Statistics

Fetal ASM isolated from at least 3 different fetal lung samples, with multiple repetitions for each sample for all experiments. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test and presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance is indicated as p<0.05.

Results

Effect of Hyperoxia on BDNF Expression and Secretion

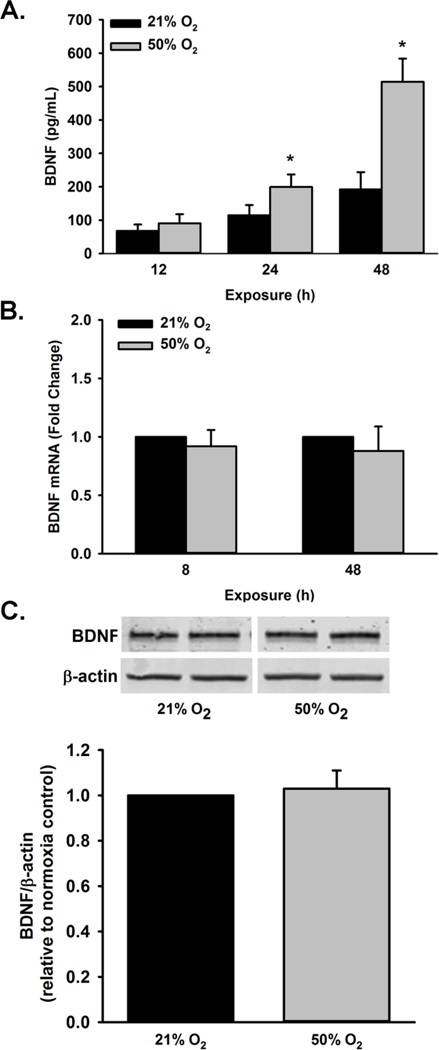

ELISA of fetal ASM showed a significant increase in BDNF secretion (pg/ml) from 50% O2 exposed cells at 24 and 48 h (but not 12h) compared to room air (p<0.05; Figure 1A.). To determine if 50% O2 increases BDNF transcription, RNA was isolated from fetal ASM for qRTPCR analysis following 8 and 48 h of 21% O2 or 50% O2 exposure. There was no difference observed in BDNF mRNA expression between time points (Figure 1B). Additionally, intracellular BDNF expression at 48h was assessed and found not to be altered (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Effect of 50% O2 exposure on BDNF expression and secretion. (A) Cells were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 8 h, 24 h or 48 h. Exposure to 50% O2 increased BDNF secretion after 24 and 48 h of exposure. (B) BDNF mRNA levels were not altered at 8 and 48 h, (C) and intracellular BDNF expression was also unchanged after exposure to 50% O2 for 48 h. Message RNA levels are presented as fold change relative to control. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n=at least 3 samples, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2 at the respective time point.

Effect of Hyperoxia on [Ca2+]i Responses to Histamine

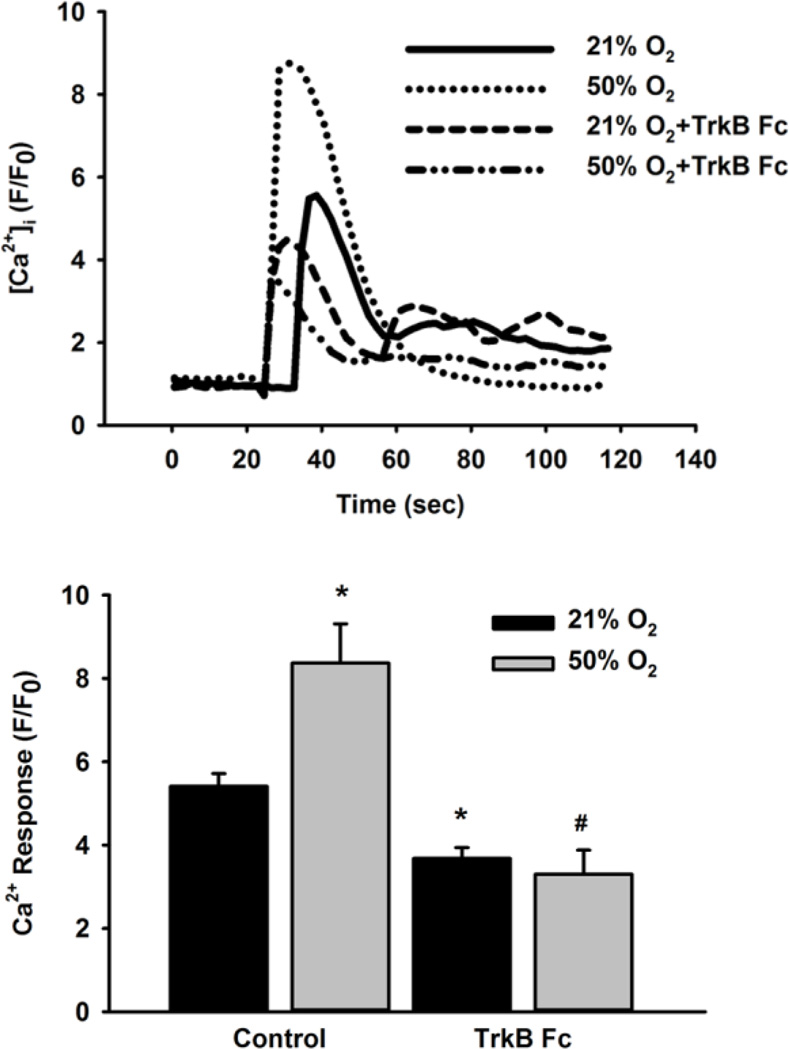

In Fluo-4 loaded fetal ASM cells 48h exposure to moderate hyperoxia significantly increased the amplitude of [Ca2+]i responses to 10 µM histamine compared to normoxic controls. Incubation with the chimeric BDNF chelator TrkB-Fc (1µg/mL) significantly reduced the peak histamine responses in fetal ASM exposed to both normoxia and moderate hyperoxia (p<0.05; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Role of BDNF in [Ca2+]i response following 50% O2 exposure. Fetal ASM in media only or TrkB-Fc (BDNF chelator) were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Cells were then loaded with Fluo-4 and stimulated with 10 µM histamine. [Ca2+]i response was greater in cells exposed to 50% O2 than 21% O2-exposed cells while cells treated with TrkB-Fc during 50% O2 exposure blunted the peak [Ca2+]i response. Data are presented as mean± SE, n= 3 samples, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2. # indicates significant difference from 50% O2.

Effect of cAMP on Hyperoxia-induced BDNF Secretion

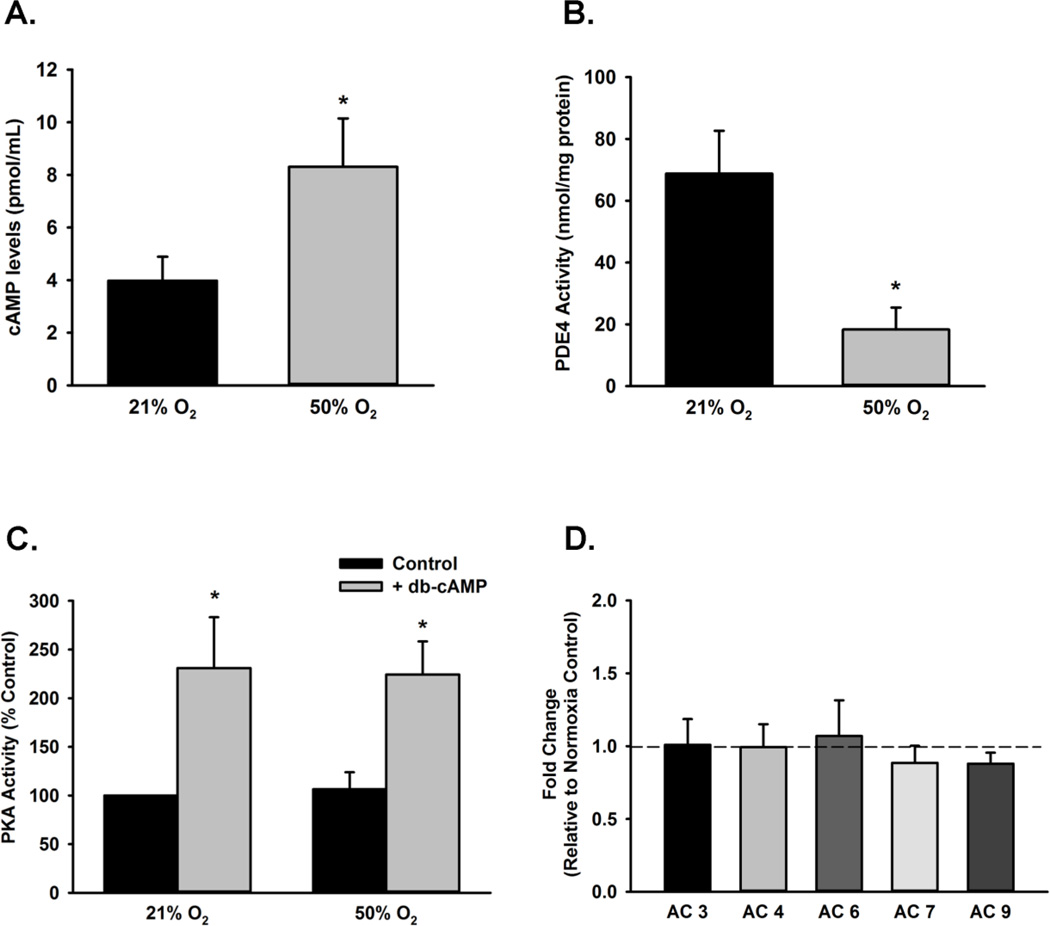

Fetal ASM were exposed to 50% O2 for 48 h followed by measurement of cyclic AMP levels via ELISA. Compared to normoxic control cells, 50% O2 significantly increased cAMP levels (p<0.05; Figure 3A). Conversely, cells exposed to 50% O2 for 48 h show significantly decreased PDE4 activity (p<0.05; Figure 3B). Fetal ASM treated with the cell-permeant cAMP analog db-cAMP showed a significant increase in PKA activity, while 50% O2 exposed cells did not have enhanced PKA activity (Figure 3C). Expression of AC isoforms (3, 4, 5, 7, and 9) were not changed in cells exposed to 50% O2 (Fig 3D).

Figure 3.

Effect of 50% O2 on cAMP levels and PDE4 activity. (A) Cells were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Cyclic AMP levels were increased in fetal ASM exposed to 50% O2 after 48 h. (B) Compared to control cells, 50% O2 exposure led to reduced PDE4 activity in cell lysates. (C) Cells were treated with control or dibutyryl-cAMP and then exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. While db-cAMP increased PKA activity, exposure to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for did not significantly change PKA activity. (D) Adenylyl Cyclase isoform mRNA expression levels were not altered in cells exposed to 50% O2 for 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n= 3–4 samples, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2.

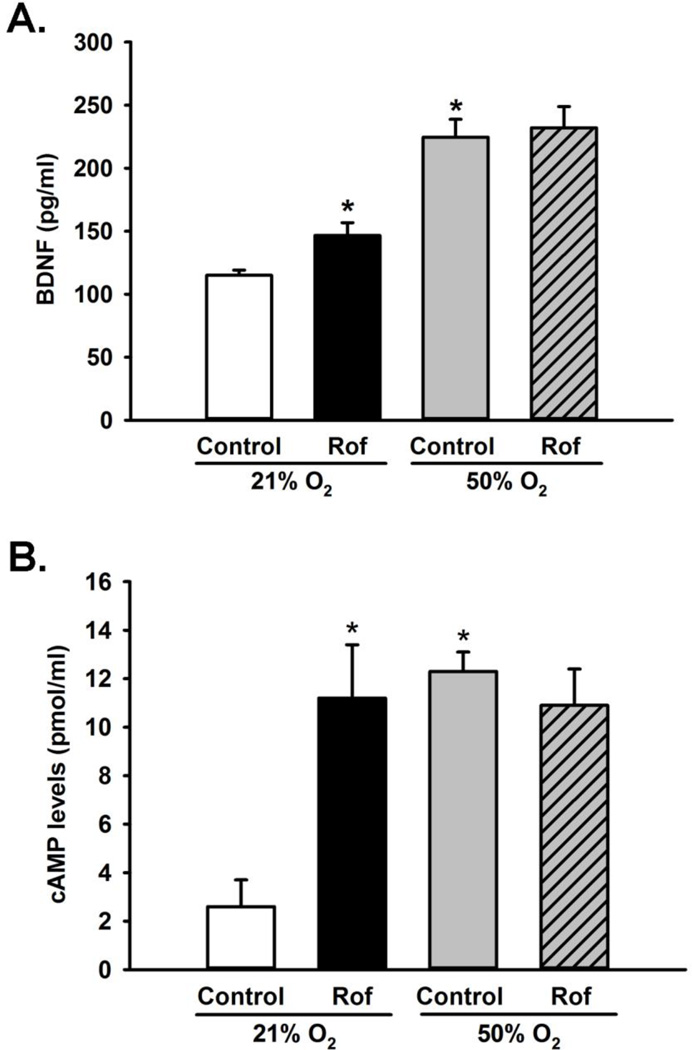

Fetal ASM incubated with PDE4 inhibitor Roflumilast for 48 h showed significant increase in BNDF secretion in normoxia-exposed cells, compared to untreated controls (p<0.05; Figure 4A); however, no such difference was observed in Roflumilast-treated fetal ASM exposed to hyperoxia. Consistently, fetal ASM incubated with Roflumilast show a significant increase in cAMP levels in normoxia compared to untreated controls (p<0.05; Fig 4B), but in the presence of moderate hyperoxia no difference in cAMP levels was observed in Roflumilasttreated cells.

Figure 4.

Role of PDE4 in modulating BDNF secretion. (A) Fetal ASM were incubated in the presence or absence of Roflumilast and exposed to 21% or 50% O2 for 48 h and media assayed for BDNF. Roflumilast significantly increased BDNF secretion under normoxic conditions but not during hyperoxia exposure. (B) Cells treated with Roflumilast and exposed to normoxia and hyperoxia for 48 h were analyzed for cAMP levels. Significant increases in cAMP levels are observed in cells treated with Roflumilast in 21% O2; however, no change is seen in Roflumilast treated cells compared to controls when exposed to 50% O2. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n=3 samples, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2.

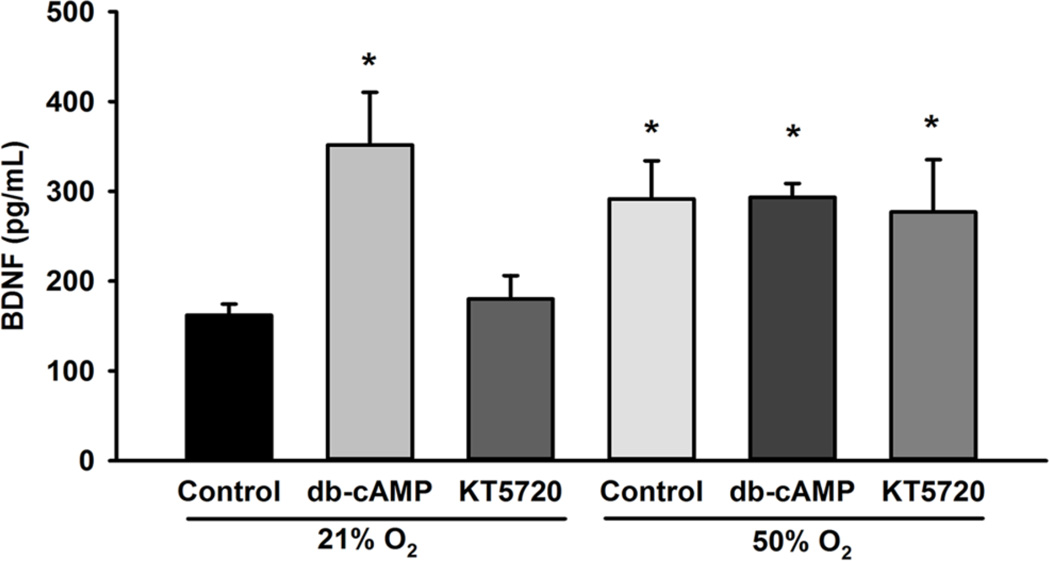

To determine the contribution of cAMP to BDNF secretion, cells were treated with dbcAMP in both 21% O2 and 50% O2. BDNF secretion was significantly increased in cells treated with db-cAMP in both the 21% O2 and 50% O2 exposed groups (Figure 5). Since cAMP effects can be mediated through PKA, we compared secretion of BDNF in fetal ASM exposed to 21% O2 and 50% O2 in the absence vs. presence of KT5270, a PKA inhibitor. In the presence of KT5270, 50 % O2 continued to stimulate BDNF secretion (p<0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of cAMP analog and PKA inhibitor on BDNF secretion. Fetal ASM were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Dibutyryl-cAMP (cAMP analog) increased BDNF secretion in 21% O2-exposed cells, while KT5270 (PKA inhibitor), did not alter 50% O2-induced BDNF secretion after 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n=3 samples, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2.

Role of Epac Proteins in Hyperoxia-induced BDNF Secretion

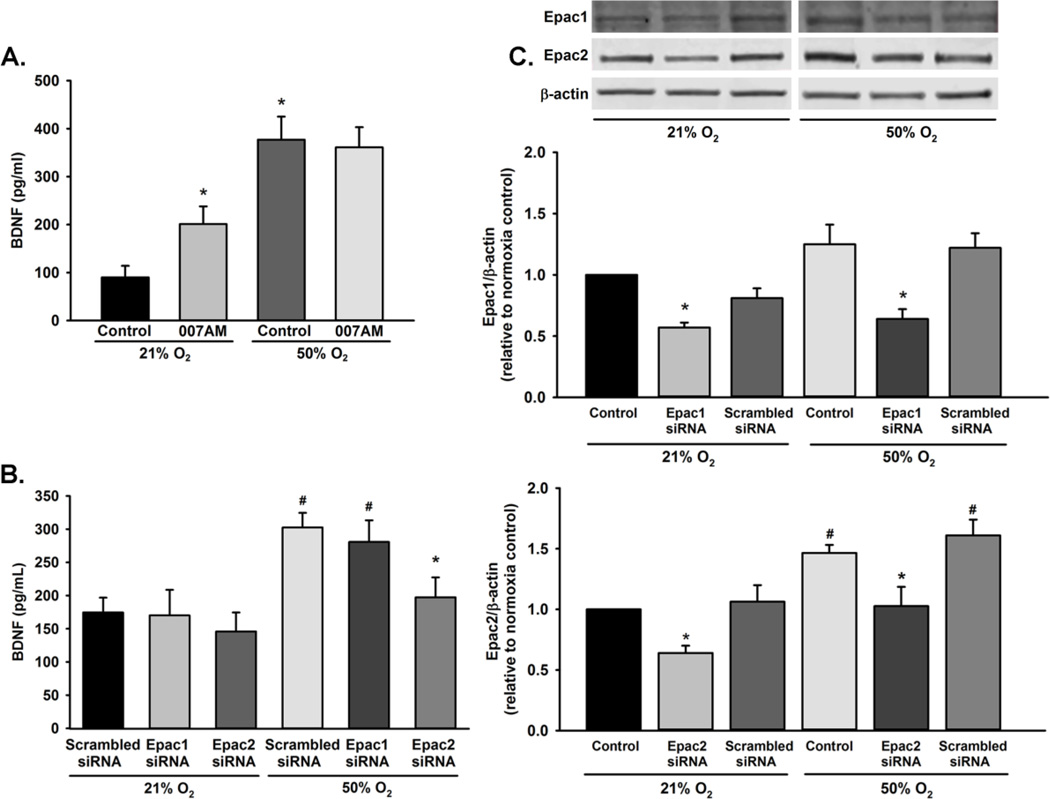

Cyclic AMP can facilitate protein secretion through activation of Epac1 and Epac2. Since PKA activity did not appear to play a role in BDNF secretion during 50% O2 exposure, we alternatively hypothesized that Epac1 and/or Epac2 mediate BDNF secretion. Exposure to 10 µM 8-CPT-2-O-Me-cAMP-AM, an Epac1 and Epac2 activator, for 48 h resulted in significant increase of BNDF secretion at normoxia. However, no change in BDNF secretion was observed in 8-CPT-2-O-Me-cAMP-AM stimulated cells exposed to 50% O2 (Figure 6A). To elucidate the role of Epac1 and Epac2 on BDNF secretion, we utilized Epac1 and Epac2 siRNA in cells exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Although siRNA knockdown of Epac1 expression did not alter 50% O2-induced BDNF secretion, cells treated with Epac2 siRNA showed significantly decreased BDNF secretion with 50% O2 exposure (p<0.05; Figure 6B). Compared to 21% O2 exposed cells, 50% O2 increased expression of Epac1 and Epac2 (p<0.05; Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Role of Epac1 and Epac2 in BDNF secretion. (A) Fetal ASM cells were exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h in the presence or absence of 8-CPT-2-O-Me-cAMP-AM and supernatants assayed for BDNF secretion via ELISA. Levels of BDNF were increased in the presence of Epac stimulation in 21% O2, but not during 50% O2 exposure. (B) BDNF secretion was decreased in 50% O2 exposed cells transfected with Epac2 siRNA, but not Epac1 siRNA. (C) Cells were treated with control, Epac1 or Epac2 siRNA during exposure to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Exposure to 50% O2 increased expression of Epac2. Data are presented as mean ± SE. p<0.05. * indicates significant effect of Epac siRNA; # indicates significant difference from 21% O2 + scrambled siRNA.

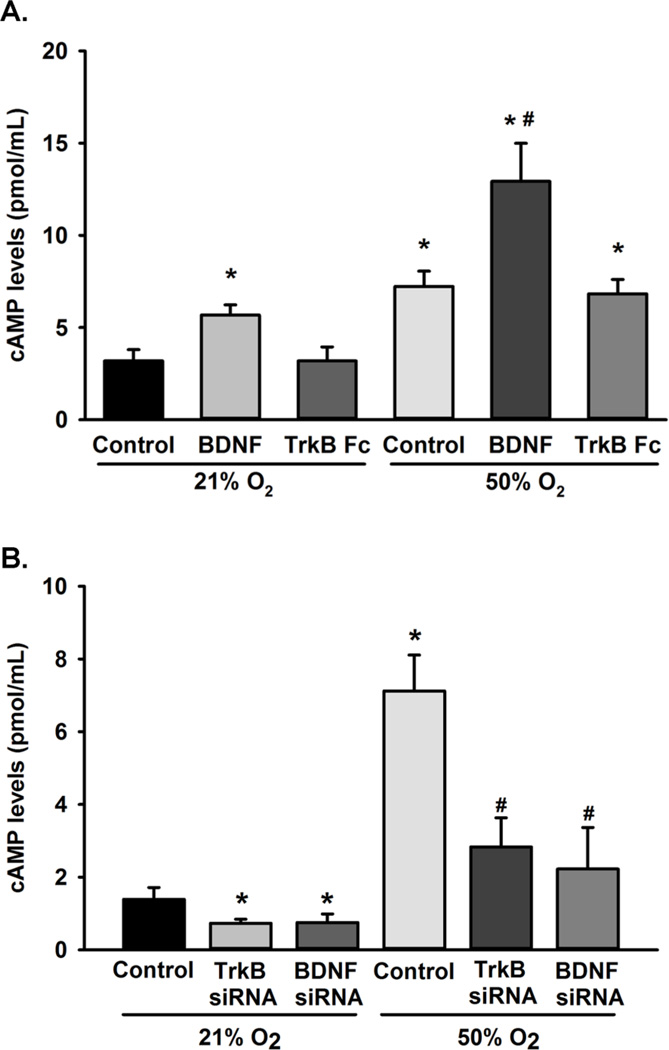

Effect of BDNF on cAMP

In neurons, BDNF can regulate cAMP levels, thus resulting in a feed-forward mechanism. We investigated the role of BDNF and its receptor, TrkB, on cAMP levels. Cells were treated with exogenous BDNF or with the chimeric compound TrkB-Fc, which chelates extracellular BDNF, during 21% O2 or 50% O2 exposure for 48 h. Cyclic AMP levels were significantly increased in cells exposed to BDNF, and 50% O2 enhanced such effects of BDNF on cAMP (p<0.05; Figure 7A). Furthermore, cells transfected with siRNA targeting BNDF or TrKB significantly reduced cAMP levels in cells exposed to 21% O2 or 50% O2 (p<0.05; Fig 7B). Interestingly, TrkB-Fc did not prevent increases in cAMP levels during 50% O2 exposure (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of BDNF and TrkB on cAMP levels. (A) Fetal ASM were untreated or treated with BDNF or TrkB-Fc during exposure to 21% O2 or 50% O2 for 48 h. BDNF increased cAMP levels while the BDNF chelator, TrkB-Fc, reduced 50% O2-induced cAMP levels. (B) Cells transfected with siRNA against BDNF and TrkB show a significant reduction in cAMP levels. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n=3, p<0.05. * indicates significant difference from 21% O2; $ indicates significant difference from 21% O2 + BDNF; # indicates significant difference from 50% O2.

Discussion

Recent studies implicate BDNF as a contributor to airway hypercontractility and remodeling, which are hallmark features of airway diseases. Previously, we have demonstrated that human ASM express BDNF and its receptors, TrkB and p75NTR. Via autocrine or paracrine activation of TrkB, BDNF can regulate human ASM proliferation and Ca regulatory mechanisms which are both key for dysfunction in airway disease [28, 55–57]. However, there is currently limited data on the source and role of BDNF in the developing airway or its functional significance. In the present study, we show that human fetal ASM expresses and secretes BDNF, with increased secretion in the presence of moderate hyperoxia. Such secreted BDNF contributes to hyperoxia-enhanced [Ca2+]i responses to agonist: effects blunted by TrkB-Fc, a chimeric peptide chelator. In this regard, [Ca2+]i per se might be contributory to BDNF secretion and its effects, as suggested by previous studies in adult ASM showing that on the one hand, hyperoxia enhances [Ca2+]I, while conversely BDNF secretion is blunted by [Ca2+]i chelation [57]. The present study now demonstrates the importance of cAMP in the link between hyperoxia and BDNF in the context of [Ca2+]i. Together, these findings are relevant to the use of hyperoxia in the neonatal ICU for premature infants, and suggests the potential for BDNF to then have autocrine/paracrine effects on the developing airway.

Cyclic AMP is a second messenger that can modulate multiple cellular functions including exocytosis, cell proliferation and muscle contraction. In the present study, exposure to 50% O2 resulted in increased cAMP levels in fetal ASM. A number of mechanisms may contribute to hyperoxia-induced changes in cAMP including adenylyl cyclase and the phosphodiesterases (PDEs). In adult ASM, PDE4 is a key regulator of cAMP levels [58] and reduction in its activity can lead to increased activation of cAMP-mediated pathways [59]. However, there is currently very little information on these mechanisms in the developing airway. In human fetal ASM, we found that exposure to hyperoxia decreased PDE4 activity, a finding in contrast to data in alveoli of mouse and rat pups [60, 61] which may reflect differential hyperoxia effects on airways vs. lung parenchyma, species differences, as well as differences in oxygen concentration and duration. While we did not specifically examine the mechanisms by which hyperoxia affects PDE4, oxidative stress is a likely pathway. For example, previous studies on endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) report a dramatic decrease in PDE4B and PDE4C mRNA levels (but not PDE5) in response to oxidative stress [62], resulting in compromised anigiogenic potential. Our studies are the first to establish hyperoxia-induced changes in PDE4 in fetal ASM, and the data are consistent with hyperoxia-induced increased cAMP. Additionally, there is little data on the effect of hyperoxia on adenylyl cyclase (AC), the enzyme which catalyzes formation of cAMP. Previous studies have suggested that oxidative stress does not alter the expression of AC6 in murine EPCs [62], but little is known about its effect on the developing airway. Given the range of AC isotypes, a thorough investigation into the role of the AC pathway was beyond the scope of this particular study. However, mRNA screening found AC3, 4, 6, 7 and 9 in fetal ASM. Importantly, and somewhat surprisingly, none of these mRNAs were altered by moderate hyperoxia. Pilot studies using the AC inhibitor, SQ22536 showed only modest decrease in cAMP in the presence of 50% O2 suggesting that much of the hyperoxia effect on cAMP may involve PDEs or other non-AC mechanisms.

We also assessed the interaction between cAMP and BDNF during hyperoxia exposure. Treatment with exogenous cAMP increased BDNF secretion during 21% O2 and 50% O2 exposure. While BDNF increased cAMP levels in 21% O2 exposed cells, 50% O2 exposure and BDNF treatment synergistically increased cAMP levels. However, chelation of secreted BDNF did not alter increased cAMP levels during 50% O2 exposure. These data suggest that heightened exogenous levels of BDNF, but not endogenous ASM production of BDNF, can increase cAMP levels. Overall, these data demonstrate that secreted BDNF does not have an autocrine effect on cAMP levels per se during exposure to hyperoxia.

The role of cAMP in ASM is complex and is relevant to multiple mechanisms in the airway, most notably for mediating ASM relaxation via β-agonists. PKA is activated in response to increases in cAMP levels and can inhibit multiple pro-contractile mechanisms within ASM. Although exposure to 50% O2 increased cAMP levels, we found that PKA activity was not altered, a finding similar to previous studies in neonatal and adult rats which reported a lack of PKA activation in the presence of hyperoxia therefore suggesting an alternate target of cAMP [57, 58]. Additionally, pharmacological inhibition of PKA activity did not alter 50% O2-induced BDNF secretion. Previous studies in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts have found that isoproterenol-stimulated release of IL-6 can be regulated independent of PKA activation indicating a novel mechanism for modulating secretion [63]. Based on these data, we speculate that cAMP facilitates BDNF secretion through a PKA-independent mechanism.

Epac1 and Epac2 are proteins that were recently identified as guanine exchange factors whose activity are cAMP dependent [64]. Epac activity leads to activation of Ras-like small GTPases, including Rap1 [64]. Epac1 and Epac2 mRNA expression were reported in the neonatal mouse lung among other tissues such as the heart and brain [65]. At 3 weeks of age, their expression in the mouse lung increased compared to fetal lung expression [65], however to date the expression patterns in the human lung have not been reported. Although transcriptional regulation of Epac expression remains undefined, recent studies showed that TGFβ decreases Epac1 expression in cardiac and lung fibroblasts [66]. The effects of hyperoxia on Epac expression has not been explored in the context of the developing lung. Given the differential expression of Epacs in the lung during the neonatal period and the effects of hyperoxia on Epac2, future studies should investigate Epacs during hyperoxia exposure. Our study suggests that Epacs in ASM may be important for signaling in the developing airway, and in development of neonatal airway diseases, e.g. via secretion of growth factors such as BDNF.

Epac2 and Rap1 regulate insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells [67]. Thus, we hypothesized that Epac1 and/or Epac2 may be involved in BDNF secretion stimulated by exposure 50% O2. Expression of Epac2, but not Epac1, was increased upon exposure to 50% O2. Subsequently, we used siRNA knockdown studies to determine if Epac1 and/or Epac2 were involved in BDNF secretion. Our studies demonstrate that Epac2 was involved in BDNF secretion during 50% O2 exposure. Recent studies demonstrate that Epac1 and Epac2 regulate bradykinin-induced IL-8 secretion and relaxation mechanisms in adult ASM [68, 69]. However, Epacs may not be involved in ASM relaxation mediated by isoproterenol, whose effects were demonstrated to be mediated through PKA-dependent pathways [70]. These recent studies suggest that there may be differential effects of cAMP and Epac depending on the stimulus.

Cyclic AMP compartmentalization is another important factor that could influence the effects of hyperoxia on BDNF secretion. A-kinase Anchoring proteins (AKAP) contribute to regulation of cAMP by modulating formation of complexes which include PDE4 and PKA [71]. In human ASM, AKAP has been demonstrated to regulate intracellular cAMP localization and modulate β2-Adrenergic receptor signaling [72]. Epacs can also be part of the AKAP complex, recent studies showed co-localization amongst Epac1, AKAP, PDE4, and PKA [73], suggesting that Epac could potentially be part of an AKAP-regulated complex in fetal ASM. However, the the effects of hyperoxia on the formation of this complex remain unknown. We speculate that exposure to hyperoxia could have an as of yet undefined effect on cAMP compartmentalization, which potentially could mediate Epac vs PKA activation.

Regarding developing ASM, modulation of Epac2 expression and BDNF secretion by moderate hyperoxia has implications for airway development as well as airway remodeling. These data identifies a novel role for Epac2 in protein release by ASM and set the basis for future investigations on altered airway function/structure observed in former preterm infants.

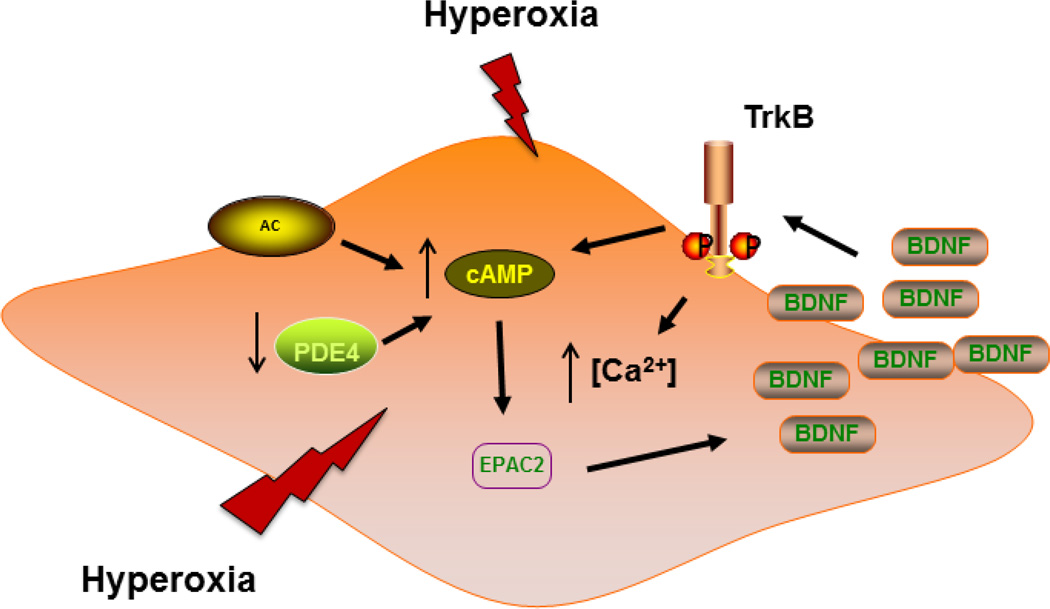

Figure 8.

Mechanism of BDNF secretion in fetal ASM. Exposure to moderate hyperoxia increases BDNF secretion, but not mRNA or protein expression, in developing ASM. Hyperoxia also increased cAMP levels which may be due, in part, to reduced phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) activity. The effect of hyperoxia on BDNF is independent of PKA activation. However, our data suggests that BDNF secretion is mediated through Epac2 to modulate protein exocytosis. In addition to hyperoxia, BDNF also increased cAMP levels which suggest that, possibly through its receptor TrkB, secreted BDNF could enhance the cAMP-Epac2 pathway.

Highlights.

Human fetal ASM secretes BDNF in response to moderate (50%) hyperoxia

50% O2 increases cAMP in fetal ASM through inhibition of PDE4.

cAMP works through Epac1 and 2 to enhance BDNF secretion

Epac2 in developing airway may be important for signaling responses to hyperoxia

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL 105355 (Britt), F32 HL123075 (Britt), R01 HL 056470 (Prakash, Martin), and R01 HL 088029 (Prakash)) and the Department of Anesthesiology, Mayo Clinic (Prakash, Pabelick).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walsh MC, Hibbs AM, Martin CR, Cnaan A, Keller RL, Vittinghoff E, Martin RJ, Truog WE, Ballard PL, Zadell A, Wadlinger SR, Coburn CE, Ballard RA. Two-year neurodevelopmental outcomes of ventilated preterm infants treated with inhaled nitric oxide. J Pediatr. 2010;156:556–561 e551. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jobe AH. The new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283423e6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes D, Jr, Feola DJ, Murphy BS, Shook LA, Ballard HO. Pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Respiration. 2010;79:425–436. doi: 10.1159/000242497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abman SH. The dysmorphic pulmonary circulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a growing story. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:114–115. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-629ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chess PR, D'Angio CT, Pryhuber GS, Maniscalco WM. Pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:171–178. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwinta P, Pietrzyk JJ. Preterm birth and respiratory disease in later life. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4:593–604. doi: 10.1586/ers.10.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Pulmonary and neurological follow-up of extremely preterm infants. Neonatology. 2010;97:388–394. doi: 10.1159/000297771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar R. Prenatal factors and the development of asthma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:682–687. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283154f26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holditch-Davis D, Merrill P, Schwartz T, Scher M. Predictors of wheezing in prematurely born children. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG. 2008;37:262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbs AM, Walsh MC, Martin RJ, Truog WE, Lorch SA, Alessandrini E, Cnaan A, Palermo L, Wadlinger SR, Coburn CE, Ballard PL, Ballard RA. One-year respiratory outcomes of preterm infants enrolled in the Nitric Oxide (to prevent) Chronic Lung Disease trial. J Pediatr. 2008;153:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein RB, Huggins BW. Chronic bronchitis in children. Seminars in respiratory infections. 1994;9:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speer CP, Silverman M. Issues relating to children born prematurely. The European respiratory journal. 1998;27:13s–16s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenough A. Long-term pulmonary outcome in the preterm infant. Neonatology. 2008;93:324–327. doi: 10.1159/000121459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng DK, Lau WY, Lee SL. Pulmonary sequelae in long-term survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:603–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colin AA, McEvoy C, Castile RG. Respiratory morbidity and lung function in preterm infants of 32 to 36 weeks' gestational age. Pediatrics. 2010;126:115–128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahn K, Ojo OO, Chadwick G, Aaronson PI, Ward JP, Lee TH. Ca(2+) homeostasis and structural and functional remodelling of airway smooth muscle in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:547–552. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amrani Y, Panettieri RA., Jr Cytokines induce airway smooth muscle cell hyperresponsiveness to contractile agonists. Thorax. 1998;53:713–716. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.8.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amrani Y, Panettieri RA., Jr Modulation of calcium homeostasis as a mechanism for altering smooth muscle responsiveness in asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:39–45. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiba Y, Misawa M. The role of RhoA-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of bronchial smooth muscle contraction in airway hyperresponsiveness. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2004;40:155–167. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.40.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentley JK, Hershenson MB. Airway smooth muscle growth in asthma: proliferation, hypertrophy, and migration. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:89–96. doi: 10.1513/pats.200705-063VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekkers BG, Maarsingh H, Meurs H, Gosens R. Airway structural components drive airway smooth muscle remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:683–692. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-056DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui S, Martin JG. Structural aspects of airway remodeling in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:540–547. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scuri M, Samsell L, Piedimonte G. The role of neurotrophins in inflammation and allergy. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2010;9:173–180. doi: 10.2174/187152810792231913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakash Y, Thompson MA, Meuchel L, Pabelick CM, Mantilla CB, Zaidi S, Martin RJ. Neurotrophins in lung health and disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4:395–411. doi: 10.1586/ers.10.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao Q, Zaidi SI, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ. Neonatal lung and airway injury: a role for neurotrophins. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:156–162. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meuchel L, Townsend E, Thompson M, Cassivi S, Prakash Y. Neurotrophins produce nitric oxide in human airway epithelium. American Thoracic Society International Conf; 2010; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Mantilla CB, Pabelick CM. Neurotrophin effects on intracellular Ca2+ and force in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L447–L456. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00501.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravamudan B, Thompson M, Pabelick C, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:812–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Q, Haxhiu MA, Zaidi SI, Liu S, Jafri A, Martin RJ. Hyperoxia enhances brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase B receptor expression in peribronchial smooth muscle of neonatal rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L307–L314. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00030.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piedimonte G. Contribution of neuroimmune mechanisms to airway inflammation and remodeling during and after respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:S66–S74. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000053888.67311.1d. discussion S74-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mowla SJ, Farhadi HF, Pareek S, Atwal JK, Morris SJ, Seidah NG, Murphy RA. Biosynthesis and post-translational processing of the precursor to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12660–12666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lessmann V, Brigadski T. Mechanisms, locations, and kinetics of synaptic BDNF secretion: an update. Neurosci Res. 2009;65:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canossa M, Giordano E, Cappello S, Guarnieri C, Ferri S. Nitric oxide down-regulates brainderived neurotrophic factor secretion in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3282–3287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042504299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furini CR, Rossato JI, Bitencourt LL, Medina JH, Izquierdo I, Cammarota M. Beta-adrenergic receptors link NO/sGC/PKG signaling to BDNF expression during the consolidation of object recognition long-term memory. Hippocampus. 2010;20:672–683. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh HY, Robertson CL, Vermehren-Schmaedick A, Balkowiec A. Nitric oxide regulates BDNF release from nodose ganglion neurons in a pattern-dependent and cGMP-independent manner. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1285–1297. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Adenylyl cyclase-cyclicAMP signaling in mood disorders: role of the crucial phosphorylating enzyme protein kinase A. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:161–176. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tardito D, Perez J, Tiraboschi E, Musazzi L, Racagni G, Popoli M. Signaling pathways regulating gene expression, neuroplasticity, and neurotrophic mechanisms in the action of antidepressants: a critical overview. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:115–134. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conti AC, Cryan JF, Dalvi A, Lucki I, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is essential for the upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription, but not the behavioral or endocrine responses to antidepressant drugs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3262–3268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03262.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deogracias R, Espliguero G, Iglesias T, Rodriguez-Pena A. Expression of the neurotrophin receptor trkB is regulated by the cAMP/CREB pathway in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Condorelli DF, Dell'Albani P, Mudo G, Timmusk T, Belluardo N. Expression of neurotrophins and their receptors in primary astroglial cultures: induction by cyclic AMP-elevating agents. J Neurochem. 1994;63:509–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon SJ, Rhee SY, Seo JE, Bak HR, Lee SH, Ryu JH, Cheong JH, Shin CY, Kim GH, Lee YS, Ko KH. Oroxylin A increases BDNF production by activation of MAPK-CREB pathway in rat primary cortical neuronal culture. Neurosci Res. 2011;69:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto M, Sobue G, Li M, Arakawa Y, Mitsuma T, Kimata K. Nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (LNGFR) mRNA levels in cultured rat Schwann cells; differential time- and dose-dependent regulation by cAMP. Neurosci Lett. 1993;152:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakahashi T, Fujimura H, Altar CA, Li J, Kambayashi J, Tandon NN, Sun B. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize and secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caporali A, Emanueli C. Cardiovascular actions of neurotrophins. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:279–308. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borland G, Smith BO, Yarwood SJ. EPAC proteins transduce diverse cellular actions of cAMP. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;158:70–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breckler M, Berthouze M, Laurent AC, Crozatier B, Morel E, Lezoualc'h F. Rap-linked cAMP signaling Epac proteins: compartmentation, functioning and disease implications. Cellular signalling. 2011;23:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng X, Ji Z, Tsalkova T, Mei F. Epac and PKA: a tale of two intracellular cAMP receptors. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:651–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gloerich M, Bos JL. Epac: defining a new mechanism for cAMP action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:355–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grandoch M, Roscioni SS, Schmidt M. The role of Epac proteins, novel cAMP mediators, in the regulation of immune, lung and neuronal function. British journal of pharmacology. 2010;159:265–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Insel PA, Zhang L, Murray F, Yokouchi H, Zambon AC. Cyclic AMP is both a pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic second messenger. Acta physiologica. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holz GG, Kang G, Harbeck M, Roe MW, Chepurny OG. Cell physiology of cAMP sensor Epac. J Physiol. 2006;577:5–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Branham MT, Bustos MA, De Blas GA, Rehmann H, Zarelli VE, Trevino CL, Darszon A, Mayorga LS, Tomes CN. Epac activates the small G proteins Rap1 and Rab3A to achieve exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24825–24839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartman WR, Smelter DF, Sathish V, Karass M, Kim S, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Amrani Y, Pandya HC, Martin RJ, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Oxygen dose responsiveness of human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L711–L719. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Britt RD, Jr, Faksh A, Vogel ER, Thompson MA, Chu V, Pandya HC, Amrani Y, Martin RJ, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Vitamin D Attenuates Cytokine-Induced Remodeling in Human Fetal Airway Smooth Muscle Cells. J Cell Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jcp.24814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abcejo AJ, Sathish V, Smelter DF, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Hartman WR, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances calcium regulatory mechanisms in human airway smooth muscle. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sathish V, Vanoosten SK, Miller BS, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Vassallo R, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cigarette smoke-induced airway hyperreactivity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:431–438. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0129OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vohra PK, Thompson MA, Sathish V, Kiel A, Jerde C, Pabelick CM, Singh BB, Prakash YS. TRPC3 regulates release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from human airway smooth muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2953–2960. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trian T, Burgess JK, Niimi K, Moir LM, Ge Q, Berger P, Liggett SB, Black JL, Oliver BG. beta2-Agonist induced cAMP is decreased in asthmatic airway smooth muscle due to increased PDE4D. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krymskaya VP, Panettieri RA., Jr Phosphodiesterases regulate airway smooth muscle function in health and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;79:61–74. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)79003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Visser YP, Walther FJ, Laghmani el H, Steendijk P, Middeldorp M, van der Laarse A, Wagenaar GT. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition attenuates persistent heart and lung injury by neonatal hyperoxia in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L56–L67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00041.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woyda K, Koebrich S, Reiss I, Rudloff S, Pullamsetti SS, Ruhlmann A, Weissmann N, Ghofrani HA, Gunther A, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Morty RE, Schermuly RT. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4 enhances lung alveolarisation in neonatal mice exposed to hyperoxia. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:861–870. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00109008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Curatola AM, Xu J, Hendricks-Munoz KD. Cyclic GMP protects endothelial progenitors from oxidative stress. Angiogenesis. 2011;14:267–279. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yin WY, F1, Du JH, Li C, Lu ZZ, Han C, Zhang YY. Noncanonical cAMP pathway and p38 MAPK mediate beta2-adrenergic receptor-induced IL-6 production in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006 Mar;40:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt M, Dekker FJ, Maarsingh H. Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (epac): a multidomain cAMP mediator in the regulation of diverse biological functions. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:670–709. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ulucan C, Wang X, Baljinnyam E, Bai Y, Okumura S, Sato M, Minamisawa S, Hirotani S, Ishikawa Y. Developmental changes in gene expression of Epac and its upregulation in myocardial hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1662–H1672. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00159.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yokoyama U, Patel HH, Lai NC, Aroonsakool N, Roth DM, Insel PA. The cyclic AMP effector Epac integrates pro- and anti-fibrotic signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6386–6391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801490105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibasaki T, Takahashi H, Miki T, Sunaga Y, Matsumura K, Yamanaka M, Zhang C, Tamamoto A, Satoh T, Miyazaki J, Seino S. Essential role of Epac2/Rap1 signaling in regulation of insulin granule dynamics by cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19333–19338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roscioni SS, Kistemaker LE, Menzen MH, Elzinga CR, Gosens R, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, Schmidt M. PKA and Epac cooperate to augment bradykinin-induced interleukin-8 release from human airway smooth muscle cells. Respir Res. 2009;10:88. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roscioni SS, Maarsingh H, Elzinga CR, Schuur J, Menzen M, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, Schmidt M. Epac as a novel effector of airway smooth muscle relaxation. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1551–1563. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan SJ, Deshpande DA, Tiegs BC, Misior AM, Yan H, Hershfeld AV, Rich TC, Panettieri RA, An SS, Penn RB. beta-Agonist-mediated Relaxation of Airway Smooth Muscle Is Protein Kinase A-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:23065–23074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willoughby D, Wong W, Schaack J, Scott JD, Cooper DM. An anchored PKA and PDE4 complex regulates subplasmalemmal cAMP dynamics. Embo J. 2006;25:2051–2061. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Horvat SJ, Deshpande DA, Yan H, Panettieri RA, Codina J, DuBose TD, Jr, Xin W, Rich TC, Penn RB. A-kinase anchoring proteins regulate compartmentalized cAMP signaling in airway smooth muscle. Faseb J. 2012;26:3670–3679. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dodge-Kafka KL, Soughayer J, Pare GC, Carlisle Michel JJ, Langeberg LK, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD. The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature. 2005;437:574–578. doi: 10.1038/nature03966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]