Abstract

Context:

The burden of injuries to college ultimate players has never been fully described.

Objective:

To quantify the injury rate in ultimate players and describe the diagnoses, anatomic locations, and mechanisms of injuries.

Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting:

College ultimate teams in the United States during the 2012 season.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Initial injury rate per 1000 athlete-exposures.

Results:

The initial injury rate in college ultimate players was 12.64 per 1000 athlete-exposures; the rate did not differ between men and women (P = .5). Bivariate analysis indicated that injuries occurred twice as often during games as during practices, men were more likely than women to be injured when laying out for the disc, and men were more likely to incur strains and sprains than women.

Conclusions:

Injury patterns to college ultimate players were similar to those for athletes in other National Collegiate Athletic Association sports. This is the first study to systematically describe injuries to ultimate players.

Key Words: injury mechanisms, injury surveillance, athletic injuries, Barell matrix

Key Points

Injury patterns in college ultimate players were similar to those in athletes pursuing other National Collegiate Athletic Association sports.

Injury rates did not differ between male and female ultimate players; however, the injury patterns suggest the need for sex-specific preventive strategies.

The sport of ultimate, often called Ultimate Frisbee, was created in the late 1960s in Columbia, New Jersey.1,2 According to USA Ultimate, the governing body of ultimate in the United States, an estimated 1.5 million adults and children played ultimate at least 13 times in the United States in 2011.3 The sport can be described as a cross between soccer and American football: the offensive team passes the disc among themselves with the intent of receiving a pass in the end zone for a goal, and the defensive team seeks to intercept or force the offensive team to drop the disc, at which time the defensive team immediately becomes the offensive team.1 From both the prior literature4 and our own experience in the sport, we believe that soccer serves as the most appropriate comparison sport.

The injury rate in ultimate players has never been reported, and limited research has been conducted on the burden of injuries in ultimate. In a small retrospective survey5 of players participating in an informal tournament, almost 90% had experienced at least 1 injury while playing that had caused them to miss time playing ultimate. At the 2007 Ultimate Players Association College National Championships, men were injured at a higher rate than women, and laying out (ie, diving for the disc) and contact with other players accounted for more than half of the injuries.6 Competition in USA Ultimate is generally divided into the Youth, College, and Club divisions.7 We chose to examine the College division because its players are generally within a narrow age range (ie, 18–24 years) and because players on a given team would be located near one another, thus reducing the reporting burden for the person on each team responsible for data entry. College teams consist of degree-seeking students, and the individuals who participate are considered club, not intercollegiate, athletes.

Our goals were to establish injury rates in college ultimate players, to describe the locations and diagnoses of these injuries, and to understand the mechanisms causing these injuries.

METHODS

Data Collection

A pilot study was conducted by the research team in 2011. This trial indicated the feasibility of collecting injury data on ultimate players by using a Web-based data-entry system. However, these data suffered many limitations, such as a lack of consistent time intervals for data entry, inconsistent injury definitions, and loss to follow-up. Informed by the data collected from the pilot study and the challenges encountered, we designed a more systematic online data-collection method.

We recruited college ultimate teams from the Women's and Open divisions participating in the 2012 USA Ultimate college series; because all Open players we encountered were men, we will refer to this group as the Men's division. Using team contact information publicly available from the USA Ultimate Web site, we made e-mail contact with team representatives from men's and women's teams nationwide. With the goal of recruiting 50 teams from each division, we sent recruitment e-mails to 229 teams. Some schools had both an A and a B team (the A team being the more competitive team), so our initial study population consisted of 55 Women's Division and 57 Men's Division teams, a 49% response rate.

Each team designated 1 team member as a study contact to communicate with the research team and enter data for his or her team. The study contacts were given a tutorial on injury definitions and how to enter data. To ensure that study contacts used consistent injury definitions and were proficient with the survey instrument, a quiz was attached to the tutorial requiring each contact to enter injury situations using the data-entry system. In ultimate, an injury time-out can be granted to any player requesting it.1 This is a universally recognized rule in ultimate and aided our injury definition. In the weekly materials sent to each team contact, we asked if any injuries took place that required a player to miss part of a game or practice: “For example, an injury time-out where the player leaves the field.” Although the severity necessary to require an injury time-out would vary from player to player, this provided a standardized definition that would make injuries easily recognizable. In this article, we will refer to the injury determination in place of diagnosis because in most cases, neither an athletic trainer nor other trained medical personnel made a definitive diagnosis. Although team contacts were trained in general injury definitions, we cannot conclude that they were rendering medically accurate diagnoses.

For consistency, study staff requested that only 1 contact enter data for a given team. The data-collection instrument was built using SurveyMonkey software (Palo Alto, CA). Each week, study contacts were e-mailed a link for that week's data entry. The link would take the contact to the instrument, where information on the past week's practices, games, player attendance, and unique injuries were entered. Data collected on each injury included (1) anatomic location of injury; (2) type of injury (eg, strain, sprain, dislocation); (3) mechanism of injury (eg, noncontact while running, laying out, collision while running); and (4) whether the injury took place during a game or practice.8 This method allowed us to communicate directly with each contact, assess which contacts had completed data entry for a given week, and follow up with those who had not done so. Data collection was initiated during the first week of February 2012 and continued through the end of each team's season (the final data were entered at the end of May).

Data were collected on initial injuries only.9 Because we did not have trained medical professionals for each team, we did not want to force team contacts to determine whether a recurrent injury was due to a distinct event or was simply a reinjury.10 Thus, we instructed team contacts to enter an injury only on its first occurrence or if 3 months had passed without subsequent reinjury to a previously injured location. Because we were not collecting any personalized data, the Stanford University Institutional Review Board deemed this study not to be human subjects research.

Data Analysis

We downloaded data from SurveyMonkey using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). The data were cleaned and ordered using SPSS (version 19.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and were analyzed in Stata (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Injury incidence rates (IRs) were calculated as injuries per athlete-exposure (AE). One AE is equal to 1 player participating in 1 practice or 1 game; this unit has been used previously to analyze injury rates across practices and games11,12 and to make comparisons across sports.13,14 Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were used to compare Men's versus Women's Divisions, practice injuries versus game injuries, and practice injuries versus game injuries by sex. We compiled data on mechanism of injury, injury location, and determination and calculated IRs for the total population, including all of the Men's and Women's Divisions. The IRRs were calculated for men's versus women's players for mechanism of injury, location, and determination.

To further analyze injury incidence by body region, we created a version of the Barell matrix.15 This tool was developed to standardize the comparison of traumatic injuries. Because we did not have International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes, we could not create a Barell matrix employing the usual method; however, we used this 2-dimensional body region–by–determination matrix to compare injuries between men and women. Injuries that are specific to 1 region (eg, concussion, shin splints) and systemic injuries (eg, heat or cold injuries) were excluded from the matrix to save space.

RESULTS

A total of 6 of the 112 teams (5%) were lost to follow-up. The final sample consisted of 53 men's teams and 53 women's teams from 73 colleges and universities. There were 1317 injuries across 104 193 AEs, for an IR of 12.64 per 1000 AEs. The injury IRs for men and women did not differ (P = .5), as shown in Table 1. The IR for injuries occurring in games was 43% greater than that for practices. Both men and women were more likely to be injured during games than during practices.

Table 1.

Injury Incidence, Athlete-Exposures (AEs), Injury Incidence Rates, and Injury Rate Ratios by Sex and by Setting

| Category and Value |

Injury Incidence |

AEs |

Injury Incidence Rate (per 1000 AEs) |

Injury Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

| Total | 1317 | 104 193 | 12.64 | N/A |

| Sex | ||||

| Men's | 671 | 53 124 | 12.63 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.11) |

| Women's | 646 | 51 069 | 12.65 | N/A |

| Setting | ||||

| Practices | 503 | 49 906 | 10.08 | N/A |

| Games | 787 | 54 287 | 14.50 | 1.43 (1.28, 1.61)a |

| Missingb | 109 | — | — | — |

| Setting by sex | ||||

| Men's practices | 257 | 26 446 | 9.72 | N/A |

| Men's games | 403 | 26 678 | 15.11 | 1.55 (1.32, 1.82)a |

| Women's practices | 246 | 23 460 | 10.49 | N/A |

| Women's games | 384 | 27 609 | 13.91 | 1.33 (1.13, 1.56)a |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Incidence rate ratio significant at the α = .05 level.

Dashes indicate comparisons that are not testable.

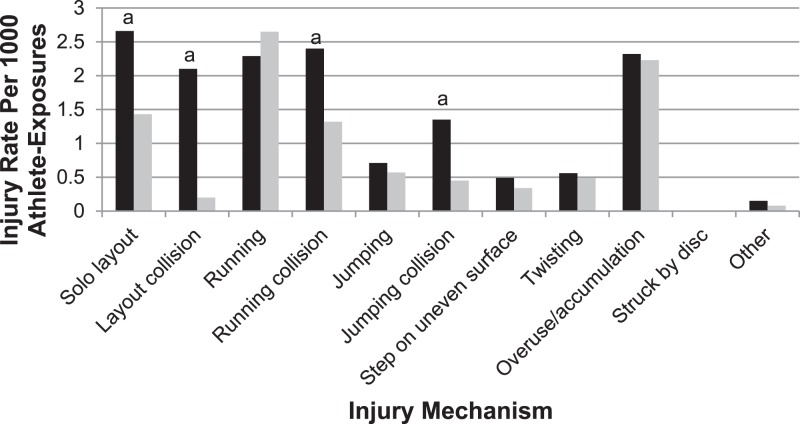

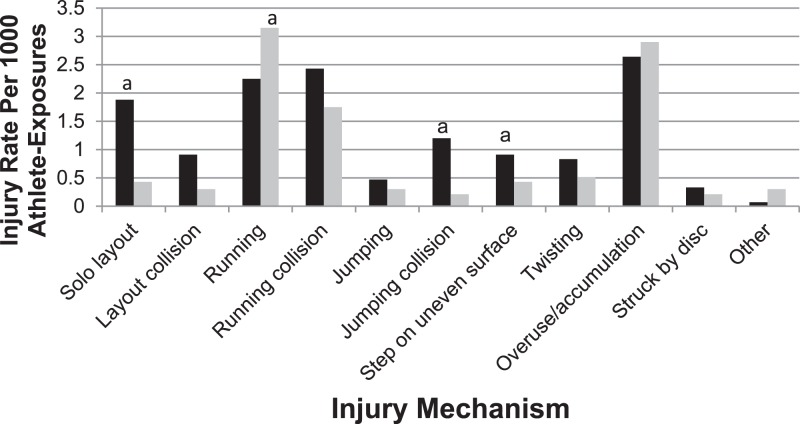

The mechanism of injury, injury location, and determination are provided in Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The most common injury was muscle/tendon strain (IR = 3.06 per 1000 AEs). The most common injury location was the ankle (IR = 2.54 per 1000 AEs). The most common mechanisms of injury were running (IR = 2.56 per 1000 AEs) and overuse/accumulation (IR = 2.51 per 1000 AEs). All IRRs for men versus women are reported in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Here we will discuss those IRRs that were statistically significant at the α = .05 level. For mechanism of injury, men were more likely than women to be injured on a layout (IRR = 1.69) or a layout collision (IRR = 1.86) and were less likely to be injured when struck by the disc (IRR = 0.14). Injury rates for each mechanism by sex, comparing game IRs with practice IRs, are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. For both men and women, layout-related injuries were more common in games compared with practices. For men, all collision-related IRs increased in games. For women, injuries caused by jumping, collision, and stepping on uneven surfaces increased in games, whereas running injuries had an increased IR in practices. Men were more likely than women to sustain injuries to the shoulder (IRR = 1.61), wrist (IRR = 3.27), torso (IRR = 1.88), and hip/pelvis (IRR = 1.76), and they were less likely to incur injuries to the face (IRR = 0.42) and knee (IRR = 0.74) or to sustain injuries to multiple locations or systemic injuries (IRR = 0.27). Men had an increased IR for sprained ligaments compared with women (IRR = 1.43; Table 4).

Table 2.

Injury Mechanismsa

| Activity |

Total No. |

Incidence Rate |

Men's |

Women's |

Injury Incidence Rate (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

| No. |

Incidence Rate |

No. |

Incidence Rate |

||||

| Solo layout | 171 | 1.64 | 109 | 2.05 | 62 | 1.21 | 1.69 (1.23, 2.34)b |

| Layout collision | 94 | 0.90 | 62 | 1.17 | 32 | 0.63 | 1.86 (1.20, 2.94)b |

| Running | 267 | 2.56 | 131 | 2.47 | 136 | 2.66 | 0.93 (0.72, 1.19) |

| Running collision | 207 | 1.99 | 99 | 1.86 | 108 | 2.11 | 0.88 (0.66, 1.17) |

| Jumping | 54 | 0.52 | 34 | 0.64 | 20 | 0.39 | 1.64 (0.91, 3.00) |

| Jumping collision | 86 | 0.83 | 48 | 0.90 | 38 | 0.74 | 1.21 (0.78, 1.91) |

| Step on uneven surface | 57 | 0.55 | 22 | 0.41 | 35 | 0.69 | 0.60 (0.34, 1.06) |

| Twisting | 60 | 0.58 | 26 | 0.49 | 34 | 0.67 | 0.74 (0.42, 1.26) |

| Struck by disc | 12 | 0.15 | 2 | 0.04 | 14 | 0.27 | 0.14 (0.02, 0.60)b |

| Overuse/accumulation | 262 | 2.51 | 121 | 2.28 | 141 | 2.76 | 0.82 (0.64, 1.06) |

| Other | 15 | 0.14 | 6 | 0.11 | 9 | 0.18 | N/A |

| Missingc | 26 | — | 11 | — | 15 | — | |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Incidence rates per 1000 athlete-exposures for Men's and Women's Divisions, incidence rate ratios for Men's/Women's Divisions.

Incidence rate ratio significant at the α = .05 level.

Dashes indicate comparisons that are not testable.

Table 3.

Injury Locationsa

| Location |

Total No. |

Incidence Rate |

Men's |

Women's |

Incidence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

| No. |

Incidence Rate |

No. |

Incidence Rate |

||||

| Head | 89 | 0.85 | 36 | 0.68 | 53 | 1.04 | 0.65 (0.42, 1.02) |

| Face | 43 | 0.41 | 13 | 0.25 | 30 | 0.59 | 0.42 (0.20, 0.82)b |

| Neck | 7 | 0.07 | 5 | 0.09 | 2 | 0.04 | 2.40 (0.39, 25.24) |

| Shoulder | 83 | 0.80 | 52 | 0.98 | 31 | 0.61 | 1.61 (1.01, 2.60)b |

| Elbow | 17 | 0.16 | 10 | 0.19 | 7 | 0.14 | 1.37 (0.47, 4.25) |

| Wrist | 22 | 0.21 | 17 | 0.32 | 5 | 0.10 | 3.27 (1.18, 11.33)b |

| Hand | 34 | 0.33 | 17 | 0.32 | 17 | 0.33 | 0.96 (0.46, 2.00) |

| Finger | 30 | 0.29 | 16 | 0.30 | 14 | 0.27 | 1.10 (0.50, 2.43) |

| Torso | 68 | 0.65 | 45 | 0.85 | 23 | 0.45 | 1.88 (1.11, 3.26)b |

| Hip/pelvis | 85 | 0.82 | 55 | 1.04 | 30 | 0.59 | 1.76 (1.11, 2.85)b |

| Upper leg | 152 | 1.46 | 73 | 1.37 | 79 | 1.55 | 0.88 (0.64, 1.24) |

| Knee | 209 | 2.01 | 91 | 1.71 | 118 | 2.31 | 0.74 (0.56, 0.98)b |

| Lower leg | 93 | 0.89 | 50 | 0.94 | 43 | 0.84 | 1.12 (0.73, 1.72) |

| Ankle | 265 | 2.54 | 135 | 2.54 | 130 | 2.55 | 1.00 (0.78, 1.28) |

| Foot | 57 | 0.55 | 31 | 0.58 | 26 | 0.51 | 1.15 (0.66, 2.01) |

| Toe | 20 | 0.19 | 12 | 0.23 | 8 | 0.16 | 1.44 (0.54, 4.07) |

| Multiple or systematic | 37 | 0.36 | 8 | 0.15 | 29 | 0.57 | 0.27 (0.10, 0.59)b |

| Missingc | 9 | — | 5 | — | 4 | — | |

Incidence rates per 1000 athlete-exposures for Men's and Women's Divisions, incidence rate ratios for Men's/Women's Divisions.

Incidence rate ratio significant at the α = .05 level.

Dashes indicate comparisons that are not testable.

Table 4.

Injury Determinationsa

| Determination |

Total |

Incidence Rate |

Men's |

Women's |

Incidence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

| No. |

Incidence Rate |

No. |

Incidence Rate |

||||

| Strain muscle/tendon | 319 | 3.06 | 180 | 3.39 | 139 | 2.72 | 1.24 (0.99, 1.56) |

| Sprain ligament | 211 | 2.03 | 126 | 2.37 | 85 | 1.66 | 1.43 (1.07, 1.90)b |

| Bruise/hematoma | 140 | 1.34 | 72 | 1.36 | 68 | 1.33 | 1.02 (0.72, 1.44) |

| Abrasion/laceration | 50 | 0.48 | 29 | 0.55 | 21 | 0.41 | 1.33 (0.73, 2.45) |

| Fracture | 41 | 0.39 | 24 | 0.45 | 17 | 0.33 | 1.36 (0.70, 2.69) |

| Dislocation/subluxation/separation | 25 | 0.24 | 16 | 0.30 | 9 | 0.18 | 1.71 (0.71, 4.39) |

| Bursitis | 7 | 0.07 | 3 | 0.06 | 4 | 0.08 | 0.72 (0.11, 4.26) |

| Tendinitis | 23 | 0.22 | 9 | 0.17 | 14 | 0.27 | 0.62 (0.24, 1.53) |

| Concussion | 47 | 0.45 | 18 | 0.34 | 29 | 0.57 | 0.60 (0.31, 1.11) |

| Asthma attack | 8 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.02 | 7 | 0.14 | 0.14 (0.03, 1.07) |

| Heat injury/illness | 11 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.04 | 9 | 0.18 | 0.21 (0.02, 1.03) |

| Cold injury/illness | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.02 | Unable to calculate |

| Ligament tear | 10 | 0.10 | 3 | 0.06 | 7 | 0.14 | 0.87 (0.31, 2.37) |

| Shin splints | 19 | 0.18 | 9 | 0.17 | 10 | 0.20 | 0.80 (0.63, 1.01) |

| Pain: no diagnosis | 287 | 2.76 | 130 | 2.45 | 157 | 3.07 | 0.59 (0.35, 0.96) |

| Unsure: will follow-up | 74 | 0.71 | 28 | 0.53 | 46 | 0.90 | 1.55 (1.05, 2.29)b |

| Other | 35 | 0.34 | 15 | 0.28 | 20 | 0.39 | N/A |

| Missingc | 9 | — | 6 | — | 3 | — | |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Incidence rates per 1000 athlete-exposures for Men's and Women's Divisions, incidence rate ratios for Men's/Women's Divisions.

Incidence rate ratio significant at the α = .05 level.

Dashes indicate comparisons that are not testable.

Figure 1.

Injury incidence rates (IRs) for mechanisms of injury for practices (black bars) versus games (gray bars) for men. aSignificant difference for IRs between games and practices.

Figure 2.

Injury incidence rates (IRs) for mechanisms of injury for practices (black bars) versus games (gray bars) for women. aSignificant difference for IRs between games and practices.

A partial Barell matrix is shown in Table 5. The most common injuries were ankle sprain (men: n = 77; women: n = 62) and muscle/tendon strain of the upper leg (men: n = 52; women: n = 58). Men were much more likely than women to have a separation/dislocation/subluxation of the shoulder, and women were more likely than men to tear a knee ligament.

Table 5.

Partial Barell Matrix of Injuries by Locationa

| Anatomic Location |

Injury Determination |

|||||||||

| Strain Muscle/ Tendon |

Sprain Ligament |

Bruise/ Hematoma |

Abrasion/ Laceration |

Fracture |

Dislocation/ Separation/ Subluxation |

Bursitis |

Tendinitis |

Ligament Tear |

Pain: No Diagnosis |

|

| Head | 0/2 | 0/0 | 2/4 | 1/0 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 13/16 |

| Face | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/10 | 5/7 | 7/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/7 |

| Neck | 2/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2/2 |

| Shoulder | 10/10 | 6/2 | 2/2 | 0/0 | 2/1 | 15/5 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2/0 | 11/5 |

| Elbow | 3/1 | 0/2 | 3/1 | 4/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| Wrist | 2/1 | 7/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/3 |

| Hand | 0/0 | 1/3 | 4/5 | 1/2 | 4/2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 4/2 |

| Finger | 1/3 | 7/6 | 0/1 | 1/0 | 4/0 | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/3 |

| Torso | 17/4 | 0/0 | 8/4 | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 13/8 |

| Hip/pelvis | 35/17 | 4/0 | 3/1 | 5/0 | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 7/7 |

| Upper leg | 52/58 | 1/0 | 13/2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 6/13 |

| Knee | 13/15 | 20/8 | 15/15 | 4/2 | 0/0 | 0/2 | 3/4 | 4/7 | 1/7 | 22/41 |

| Lower leg | 20/9 | 0/2 | 7/6 | 1/2 | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/2 | 0/0 | 6/3 |

| Ankle | 19/15 | 77/62 | 3/6 | 2/0 | 1/2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2/3 | 0/0 | 25/31 |

| Foot | 6/4 | 3/2 | 5/2 | 4/2 | 1/4 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2/1 | 0/0 | 8/8 |

| Toe | 0/0 | 1/0 | 5/5 | 0/0 | 1/2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3/1 |

The number on the left in each cell is the injury incidence for men; the number on the right is the incidence for women. Data on location-specific injuries (eg, concussion, shin splints) are excluded.

DISCUSSION

In this study we were able to track initial injuries to college ultimate players using an online reporting system. We found no previous reports on methods for systematically collecting and reporting injuries to ultimate players in the peer-reviewed or gray literature. For most intercollegiate sports, injury rates are monitored by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).12 Because the NCAA system uses more precise injury definitions than were available in this study, we are not able to accurately compare ultimate injury rates with those in other NCAA sports. Yet, these results on injury determination, mechanism, and location are informative when compared with other NCAA sports.

Injuries to the hip/pelvis, upper leg, knee, lower leg, ankle, foot, and toe accounted for 67% (881 of 1317) of the total. This finding is consistent with a prior analysis,16 which demonstrated that more than half of all injuries in high school and college athletes affected the lower extremities. We noted that ankle sprain was the most commonly reported injury (Table 5). Similarly, ankle sprain was the leading cause of injury to NCAA athletes participating in men's17 and women's18 basketball, women's volleyball,19 women's field hockey,20 and men's21 and women's22 lacrosse. Although laying out creates a momentary risk to the torso, head, and upper extremities, the predominance of lower body injuries is unsurprising, given the nature of running and cutting in the sport. Even though we did not examine injury location by injury mechanism, the increase in layout-related injuries in games could indicate that players are laying out more often in games, thus putting themselves at increased risk for upper torso injuries.

Although running and overuse mechanisms accounted for 40% (529 of 1317) of injuries, collision-related injuries increased significantly in games. This is consistent with analyses that indicated male and female collegiate soccer players experienced more collision-related injuries in games and more noncontact injuries in practice.23,24

Because ultimate is not a formal intercollegiate sport, college ultimate players encounter institutional factors that increase their injury risk unlike NCAA-level athletes encounter. College ultimate teams receive minimal or no club funding from their institutions; thus, all formal coaching, practicing, and logistics are provided by volunteers. We are aware of no official athletic trainers or injury support staff for college ultimate players. Because these college players are mainly undergraduates, it is unlikely that any of them will have completed medical, nursing, or physical therapy training. In the event that a player on a given team has such training, then his or her work would be voluntary as well. Additionally, college ultimate players rely on their own health insurance and their school health care systems for treatment of and therapy for sports injuries.

Another factor increasing the risk of injury for college ultimate players is the lack of sport-specific training regimens. Although in recent years multiple ultimate athlete training programs have begun,25,26 these programs are still in their infancy. Thus, college ultimate players continue to rely primarily on word of mouth for best practices in planning and training. As these best practices become more formalized, they may help to reduce injury rates. If our surveillance system is maintained, we will be able to track the effect of sport-specific training methods on injury rates. Because 40% of injuries involve running or overuse activity, future interventions should address running form, better recovery methods after ultimate games and practices, and more appropriate warm-up routines. Overuse injuries may be related to the structure of college ultimate competition, the vast majority of which happens during 2-day tournaments, rather than during league play with 1 game per day. Teams typically play 6 to 9 games during these 2 days, with each game lasting 1 to 2 hours. This compression of competition is in contrast to most NCAA sports, in which 1 or, rarely, 2 games are played in a single day. Efforts to decrease the repetitive exertion of athletes at tournaments may decrease overuse injuries. For example, games in the newly formed professional ultimate leagues are played much less frequently than in college ultimate. Although these problems may not be exclusive to ultimate, resolving them could benefit ultimate players tremendously.

Our study is the first to establish the epidemiology of injury in college ultimate players. It is only with surveillance data like these that we can identify and address the major injury hazards facing ultimate athletes.27 In the Tables we begin to see specific areas requiring attention. Concussions are a current “hot” topic at all levels of sports.28 We found 49 reported concussions, but we suspect that this number is vastly underreported compared with the NCAA sports because of the general lack of knowledge surrounding concussion and the lack of formal medical sideline coverage of practices and games. Yet, despite undergoing compulsory concussion education, NCAA athletes still underreport concussions.29 So although education and enforcement of return-to-play guidelines are important, we believe that better concussion surveillance is necessary to more thoroughly understand this injury in ultimate players.

In the Barell matrix, 2 notable sex disparities in severe injuries exist: men separated or dislocated their shoulders 3 times more frequently than women, and women tore knee ligaments at a 7:1 ratio compared with men. We specifically followed up with the team contacts about the torn knee ligaments and found that all of the injuries were either anterior cruciate ligament tears alone or tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in addition to another ligament or tendon. The most frequently reported injury location was the ankle, comprising 26% (266 of 1020) of all unique injuries. Although the ankle injuries did not involve the tears, fractures, and dislocations noted in other body parts, prevention of these frequent injuries might be accomplished by preventive use of ankle braces30 or prophylactic ankle-strength and balance training.31 Further analysis of these data could aid medical personnel in targeting sex-specific injury-prevention strategies.

Limitations

Because data collection was conducted by volunteers and not athletic trainers or other trained medical staff, we cannot be sure of their consistency in applying the injury definitions. To address this, we made sure that each team contact was familiar with the definition of each type of injury in this study's orientation materials. However, we are not the first to use self-reported measures to calculate injury rates.32 Diagnoses were not specific enough for us to use definitive disease-classification systems, such as the ICD, for our analysis. Access to accurate ICD diagnoses would allow for comparisons between the injury rate in college ultimate and the NCAA Injury Surveillance System.12 Use of the ICD codes would have allowed for a more accurate Barell matrix.15

Future researchers should call on certified athletic trainers and medical professionals who could accurately diagnose each injury. We did not have a mechanism to validate a sample of injury entries. If continued, data collection would rely on athletic training or other medical personnel assigned to a subset of teams to assess validity-of-injury determinations and data entry.

This study examined only initial injuries and was not designed to capture reinjuries. The total injury rate for ultimate players is likely to be higher than the rates we presented, because players reaggravate existing injuries. The analysis was designed to assess the incidence and not the prevalence of injuries. The results, therefore, do not reflect players who miss practices and games because of injury; however, the AE measure gives us a more accurate picture of players who are actively at risk for injury.

CONCLUSIONS

We were able to establish injury rates in college ultimate players via online surveillance. Although overall injury rates did not differ between men and women, the locations, determinations, and mechanisms of these injuries are informative for creating injury-prevention programs in this previously underexamined population of athletes.

REFERENCES

- 1.11th Edition Rules of Ultimate. USA Ultimate Web site. 2014 http://www.usaultimate.org/resources/officiating/rules/11th_edition_rules.aspx. Accessed February 20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siedler Joe. Ultimate History Web site. 2014 http://www.ultimatehistory.com/. Accessed February 20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics. USA Ultimate Web site. 2014 http://www.usaultimate.org/membership/statistics.aspx. Accessed February 20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannon JC, Ratliffe T. Physical activity levels in coeducational and single-gender high school physical education settings. J Teach Phys Educ. 2005;24(2):149–164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds KH, Halsmer SE. Injuries from ultimate frisbee. WMJ. 2006;105(6):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen LE, Gregory A, Kuhn JE, Markle R. The ultimate frisbee injury study: the 2007 Ultimate Players Association College Championships. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(4):300–305. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181ea8b1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.History. USA Ultimate Web Site. 2014 http://www.usaultimate.org/about/history/default.aspx. Accessed February 20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gansneder BM. Research methods and injury surveillance in sports medicine. In: Perrin DH, editor. The Injured Athlete. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers;; 1999. pp. 187–199. In. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Ji M, Wiksten DL. Subsequent injury patterns in girls' high school sports. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):486–494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM. Issues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury research. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):207–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darrow CJ, Collins CL, Yard EE, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of severe injuries among United States high school athletes: 2005–2007. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1798–1805. doi: 10.1177/0363546509333015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):173–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):311–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Bowling JM, et al. A prospective study of injury incidence among North Carolina high school athletes. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(12):1209–1221. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barell V, Aharonson-Daniel L, Fingerhut LA, et al. An introduction to the Barell body region by nature of injury diagnosis matrix. Inj Prev. 2002;8(2):91–96. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolbert TA, McIlvain GE, Giangarra CE, Binkley HM. Injury rates in high school and collegiate athletics. Strength Cond J. 2011;33(3):82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick R, Hertel J, Agel J, Grossman J, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's basketball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):194–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agel J, Olson DE, Dick R, Arendt EA, Marshall SW, Sikka RS. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's basketball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):202–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agel J, Palmieri-Smith RM, Dick R, Wojtys EM, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's volleyball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):295–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dick R, Hootman JM, Agel J, Vela L, Marshall SW, Messina R. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's field hockey injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):211–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dick R, Romani WA, Agel J, Case JG, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's lacrosse injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dick R, Lincoln AE, Agel J, Carter EA, Marshall SW, Hinton RY. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's lacrosse injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):262–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agel J, Evans TA, Dick R, Putukian M, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's soccer injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):270–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dick R, Putukian M, Agel J, Evans TA, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's soccer injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):278–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrill Performance. Strength and Conditioning Fitness Web site. 2014 http://strengthandconditioningfitness.com/. Accessed February 20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ultimate Results. The Ultimate Athlete Project Web site. 2013 http://www.theultimateathleteproject.com. Accessed June 8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thacker SB. Public health surveillance and the prevention of injuries in sports: what gets measured gets done. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):171–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hainline B, Dexter WW, DiFiori J. Sports-related concussion: truth be told. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3(4):277–278. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e3182a1ba46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres DM, Galetta KM, Phillips HW, et al. Sports-related concussion: anonymous survey of a collegiate cohort. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3(4):279–287. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e3182a1ba22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farwell KE, Powden CJ, Powell MR, McCarty CW, Hoch MC. The effectiveness of prophylactic ankle braces in reducing the incidence of acute ankle injuries in adolescent athletes: a critically appraised topic. J Sport Rehabil. 2013;22(2):137–142. doi: 10.1123/jsr.22.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKeon PO, Hertel J. Systematic review of postural control and lateral ankle instability, part II: is balance training clinically effective? J Athl Train. 2008;43(3):305–315. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theisen D, Frisch A, Malisoux L, Urhausen A, Croisier JL, Seil R. Injury risk is different in team and individual youth sport. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;16(3):200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]