Abstract

Context:

Knee laxity increases during exercise. However, no one, to our knowledge, has examined whether these increases contribute to higher-risk landing biomechanics during prolonged, fatiguing exercise.

Objectives:

To examine associations between changes in fatigue (measured as sprint time [SPTIME]), multiplanar knee laxity (anterior-posterior [APLAX], varus-valgus [VVLAX] knee laxity, and internal-external rotation [IERLAX]) knee laxity and landing biomechanics during prolonged, intermittent exercise.

Design:

Descriptive laboratory study.

Setting:

Laboratory and gymnasium.

Patients or Other Participants:

A total of 30 male (age = 20.3 ± 2.0 years, height = 1.79 ± 0.05 m, mass = 75.2 ± 7.2 kg) and 29 female (age = 20.5 ± 2.3 years, height = 1.67 ± 0.08 m, mass = 61.8 ± 9.0 kg) competitive athletes.

Intervention(s):

A 90-minute intermittent exercise protocol (IEP) designed to simulate the physiologic and biomechanical demands of a soccer match.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

We measured SPTIME, APLAX, and landing biomechanics before and after warm-up, every 15 minutes during the IEP, and every 15 minutes for 1 hour after the IEP. We measured VVLAX and IERLAX before and after the warm-up, at 45 and 90 minutes during the IEP, and at 30 minutes after the IEP. We used hierarchical linear modeling to examine associations between exercise-related changes in SPTIME and knee laxity with exercise-related changes in landing biomechanics while controlling for initial (before warm-up) knee laxity.

Results:

We found that SPTIME had a more global effect on landing biomechanics in women than in men, resulting in a more upright landing and a reduction in landing forces and out-of-plane motions about the knee. As APLAX increased with exercise, women increased their knee internal-rotation motion (P = .02), and men increased their hip-flexion motion and energy-absorption (P = .006) and knee-extensor loads (P = .04). As VVLAX and IERLAX increased, women went through greater knee-valgus motion and dorsiflexion and absorbed more energy at the knee (P ≤ .05), whereas men were positioned in greater hip external and knee internal rotation and knee valgus throughout the landing (P = .03). The observed fatigue- and laxity-related changes in landing biomechanics during exercise often depended on initial knee laxity.

Conclusions:

Both exercise-related changes in fatigue and knee laxity were associated with higher-risk landing biomechanics during prolonged exercise. These relationships were more pronounced in participants with greater initial knee laxity.

Key Words: soccer, joints, anterior cruciate ligament injuries, risk factors

Key Points

Greater exercise-related changes in knee laxity during prolonged, intermittent exercise were associated with higher-risk landing biomechanics, and these effects were independent of fatigue-related changes in landing biomechanics.

Changes toward higher-risk landing biomechanics with exercise-related increases in knee laxity often were more pronounced in athletes who had greater initial knee laxity. Fatigue-related effects on landing biomechanics suggest that athletes may use markedly different movement strategies later in a game or practice, when they are fatigued. These changes are compounded by how much initial knee laxity an individual has and how much the knee laxity changes with exercise.

The effects of exercise-related changes in knee laxity and fatigue on landing biomechanics are of particular concern for women, who have greater initial knee laxity and who experience greater changes in knee laxity during exercise than men.

Authors of retrospective1–4 and prospective5,6 studies consistently have reported associations between greater magnitudes of sagittal- and transverse-plane knee-joint laxity and greater risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. Researchers examining the potential biomechanical consequences of greater magnitudes of knee laxity have reported that individuals with greater anterior-posterior knee laxity (APLAX) demonstrate greater anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur during the transition of the knee to weight bearing7,8 and shift more of the workload to the knee during the initial landing phase of a drop jump.9 Individuals with greater magnitudes of varus-valgus knee laxity (VVLAX) and internal-external–rotation knee laxity (IERLAX) demonstrate greater hip adduction and internal rotation and greater knee-valgus motions early in the landing phase10; these biomechanics are more commonly observed in females and are likely to increase ACL strain.11 Whereas these associations suggest that greater knee laxity may contribute to higher-risk landing strategies that have been associated with ACL injury, they have been reported only in laboratory studies with participants in resting conditions and do not account for the acute increases in knee laxity that can occur during exercise.

Knee-joint laxity can increase by as much as 20% above initial preexercise (baseline) values within 20 to 30 minutes of starting intermittent sport-related activity12–14 and can continue to rise with increasing exercise duration.12,15 These increases coincide with the times in games when injury rates begin to rise.16 Although this rise in injury rate with increasing game duration has been attributed largely to muscular fatigue,16 acute increases in knee laxity also may contribute to the potential for injury. For example, acute increases in knee laxity that occur during the menstrual cycle (similar in magnitude to those reported during exercise15) have been associated with greater anterior tibial translation during the transition of the knee from nonweight bearing to weight bearing8 and with greater transverse- and frontal-plane knee motions17 and moments18 during landing and cutting maneuvers. To our knowledge, no one has investigated whether biomechanical changes occur with acute increases in knee laxity during exercise.

Exercise-related increases in knee laxity have been observed shortly after the initiation of submaximal running12 and dynamic warming exercises.15 As such, these increases are thought to result primarily from viscoelastic changes in joint structures rather than muscular fatigue.15,19 However, as knee laxity continues to increase and remains elevated with increasing exercise duration,12,15 the potential for higher-risk biomechanics may be compounded as muscular fatigue develops.20–22 We are not aware of any studies in which researchers have examined relationships between concurrent changes in neuromuscular fatigue and knee laxity and lower extremity biomechanics during exercise that are consistent with the duration, intensity, and movement demands of sport activity. These findings may provide further insights into the factors that increase the risk of knee injury later in a practice or game and may guide our injury-prevention efforts.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to examine relationships between concurrent changes in fatigue and multiplanar knee laxity and changes in landing biomechanics during a 90-minute intermittent exercise protocol (IEP) in male and female athletes. After accounting for fatigue-related effects as measured by increases in sprint time (SPTIME) during a shuttle-run performance, our expectation was that greater exercise-related increases in multiplanar knee laxity would be associated with greater changes in landing biomechanics toward higher-risk strategies (eg, dynamic knee valgus,10 greater knee-extensor loading9).

METHODS

A total of 30 male and 30 female collegiate and club-sport athletes with at least 5 years of competitive experience in their respective sports were recruited to participate. Of these volunteers, 30 men (age = 20.3 ± 2.0 years, height = 1.79 ± 0.05 m, mass = 75.2 ± 7.2 kg) and 29 women (age = 20.5 ± 2.3 years, height = 1.67 ± 0.08 m, mass = 61.8 ± 9.0 kg) completed all aspects of the IEP. One woman withdrew from the IEP after the 15-minute mark and, therefore, was excluded from the analyses. Male participants consisted of the following athletes: 9 basketball, 9 soccer, 3 lacrosse, 3 ultimate Frisbee, 2 tennis, 2 volleyball, 1 football, and 1 rugby. They reported activity scores of 13.6 ± 2.6 (range, 7–16) on the Marx Activity Rating Scale.23 Female participants consisted of the following athletes: 14 soccer, 8 basketball, 2 tennis, 2 ultimate Frisbee, 2 volleyball, and 1 rugby. They reported activity scores of 13.8 ± 2.7 (range, 8–16). At the time of the study, participants were active for 6 or more hours per week without physical restrictions; had healthy left knees with no history of osteochondral, ligament, tendon, capsular, or meniscus injury; had no known medical conditions affecting the connective tissue; and had no vestibular or balance disorders. Women were tested during the first 10 days of their menstrual cycles to control for hormone-related effects on joint laxity and biomechanics.17 Participants refrained from exercise for 48 hours before testing. On the day of testing, they (1) avoided moderate to strenuous activity, which was defined as activity beyond what they normally and consistently performed; (2) maintained dietary habits consistent with their preparations for an athletic competition; and (3) did not consume alcohol. All participants wore the same footwear (Uraha 2 model G09359 for men and model G09364 for women; Adidas AG, Herzogenaurach, Germany) throughout the IEP and for all biomechanical testing. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Greensboro Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Testing Protocol

The protocol was designed to characterize exercise-related changes in fatigue, knee-joint laxity, and weight-bearing knee-joint biomechanics via serial measures taken before a prolonged IEP, every 15 minutes during the IEP, and every 15 minutes for 1 hour after the IEP. Each participant attended a familiarization session during which he or she was acquainted with all study procedures and underwent the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 (Yo-Yo IR1) to prescribe individual running intensity according to fitness level.24 This ensured that all participants put forth a similar level of effort during the IEP. During the familiarization, they also completed one 15-minute exercise bout to ensure they understood the demands of the IEP and could complete it. Next, they performed an experimental test session and a control test session. The order of the sessions was counterbalanced. To obtain biomechanical data during the testing protocol, participants were instrumented with clusters of 3 light-emitting diode markers (Phase Space, San Leandro, CA) placed on the left foot, shank, thigh, and sacrum. We determined joint centers via the centroid (ankle and knee) and rotational (hip) methods. During the experimental test session, we obtained serial measures of sprint performance, knee laxity, and lower extremity biomechanics during a 90-minute IEP. In the control condition, we obtained measures of knee laxity and lower extremity biomechanics at equivalent time points while participants rested quietly between testing segments. Given the purpose of the study, only the experimental condition is reported. Researchers have described the development of the IEP in detail24 and have characterized knee-laxity changes15 and biomechanical changes25 in response to this IEP by comparing data between control and experimental conditions.

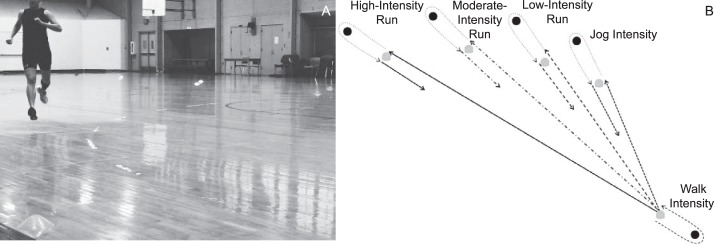

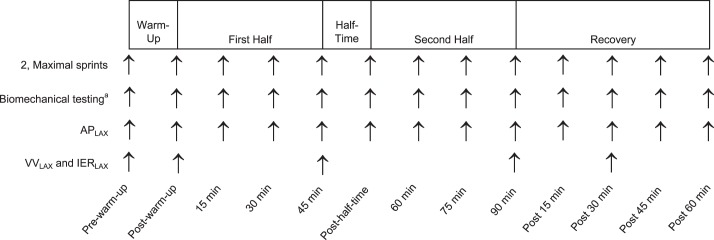

The experimental protocol consisted of a dynamic warm-up, followed by a 90-minute IEP designed to simulate the physiologic and biomechanical demands of a soccer match.15 The dynamic warm-up consisted of 3 minutes of forward and backward jogging, followed by 9 minutes of dynamic flexibility movements of increasing complexity (eg, forward and backward runs, heel kicks, side shuffles, walking lunges, inward and outward walking hip rotations, and high knees). The IEP was structured into two 45-minute halves and one 20-minute half-time intermission.24 Each 45-minute half comprised three 15-minute exercise bouts: 12 minutes of intermittent running followed by a 3-minute testing segment. The 12 minutes of intermittent running consisted of repeated 6-second shuttle runs to cones positioned at 5 different distances on a gymnasium floor to vary running intensities among jogging and low-, moderate-, and high-intensity running (Figure 1). The 3-minute testing segment consisted of 2 maximal sprint trials, 2 countermovement jumps, 3 drop jumps, and 4 perturbation trials. After the testing segment was completed, knee laxity was measured while participants rested (less than 90 seconds). Using this protocol, serial changes in maximal-effort SPTIME, APLAX, and lower extremity biomechanics were captured at 13 time points: before and after the dynamic warm-up (PreWm and PostWm, respectively), every 15 minutes during the IEP (15, 30, and 45 minutes; half; and 60, 75, and 90 minutes), and every 15 minutes during a 1-hour recovery (15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes; Figure 2). To reduce the potential for injury, maximal SPTIME was not measured PreWm, and for the purpose of analyses, we used the PostWm value to represent both PreWm and PostWm SPTIME values. Given that VVLAX and IERLAX took more than 5 minutes to obtain, these measures were limited to PreWm, PostWm, 45 and 90 minutes of the IEP, and 30 minutes into the recovery to avoid prolonged intervals of inactivity during the IEP (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A and B, Intermittent running protocol consisted of 6-second shuttle runs to cones positioned at different distances on a gymnasium floor to vary the running intensities.

Figure 2.

Measurement time points when sprint time, laxity measures, and lower extremity biomechanics were obtained before, during, and after the intermittent exercise protocol. a Biomechanical testing for the entire protocol consisted of 2 countermovement jumps, 3 drop-jump landings, and 4 lower extremity postural perturbations measured in succession without resting between activities. Abbreviations: APLAX, anterior-posterior knee laxity; IERLAX, internal-external rotation knee laxity; VVLAX, varus-valgus knee laxity.

Maximal-effort SPTIME (m/s) was measured with the 505 agility test26,27 to represent fatigue-related changes in performance during the IEP. The 505 agility test consists of a 15-m down-and-back sprint with a single cutting maneuver at the 15-m mark. At the end of each 12-minute intermittent shuttle-run block, participants walked 10 yd (9 m) and immediately performed 2 consecutive maximal sprint trials, cutting with the right limb in 1 trial and the left limb in the other trial. Total SPTIME over 30 m (start to finish) was measured to the nearest 0.01 second (Brower Timing Systems, Salt Lake City, UT). The 2 trials at each time point were averaged for analysis.

Laxity measures were acquired by 2 experienced investigators (M.M.M., A.J.T.) using established techniques with confirmed measurement consistency.10,15 All laxity measures within a participant were acquired by the same investigator across all conditions and time points. We measured APLAX as the total anterior-posterior displacement of the tibia relative to the femur during 3 continuous loading cycles from −90 N (posterior-directed load) to 130 N (anterior-directed load) using the KT-2000 knee arthrometer (MEDmetric Corp, San Diego, CA). We measured VVLAX and IERLAX with the Vermont knee-laxity device (University of Vermont, Burlington, VT) as the total rotational displacements between 3 continuous cycles of ±10 Nm varus-valgus torques and ±5 Nm internal-external rotation torques, respectively.10,15 The average APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX values over the last 2 loading cycles at each measurement time point were used for analysis.

Lower extremity biomechanics were assessed during the initial landing of 3 consecutive drop jumps from a 0.45-m height as previously described.10 Participants dropped from the box, landed evenly on both feet (left foot centered on the force plate [model 4060; Bertec Corporation, Columbus, OH]), and immediately performed a maximal-effort, double-legged vertical jump upon landing. Kinematics were acquired at 240 Hz with an 8-camera optical system (Impulse; Phase Space) and ground reaction forces were acquired at 1000 Hz with a force plate. Kinematic and kinetic data were acquired with The MotionMonitor motion-analysis software (version 8.77; Innovative Sports Training, Inc, Chicago IL) and processed using a fourth-order, zero-phase-lag, low-pass Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 12 Hz. All biomechanical variables (N = 40) were obtained during the initial landing phase of the drop jump (initial contact to peak center-of-mass displacement). We calculated 3-dimensional hip, knee, and ankle motions using Euler angle definitions at initial contact and peak center-of-mass displacement and calculated total joint excursions (peak − initial). Measurement consistency and precision of joint kinematics during the IEP have been reported.24 Corresponding intersegmental kinetic data were calculated via inverse dynamics to acquire 3-dimensional peak hip-, knee-, and ankle-joint moments normalized to body weight (BW) and height (Ht) (Nm · BW−1 · Ht−1) and anterior knee shear-force data normalized to body weight (%BW). Sagittal-plane hip, knee, and ankle stiffness (Δ net internal moment / Δ joint angle) were normalized to percentage of body weight and height (Nm · BW−1 · Ht−1). Sagittal-plane hip, knee, and ankle energy absorption (J · BW−1 · Ht−1) were calculated as the area under the negative power curve.

Principal components analysis was used to reduce the 40 kinematic and kinetic variables into 11 biomechanical factors that served as the dependent variables for our statistical analyses (Table 1). Schmitz et al25 provided a complete description of this variable-reduction process. Before the principal components analysis, all biomechanical variables were converted to standardized scores to ensure that the scale (ie, variance) of any 1 variable did not overwhelm the model. Each resultant biomechanical factor was unique (ie, independent of the others) and represented a combination of biomechanical variables that tend to be correlated with one another. Reducing the data to these 11 biomechanical factors allowed us to better summarize how lower extremity biomechanics change over time in response to exercise-related changes in SPTIME and laxity and reduce the potential for type I error in our statistical analyses. Briefly, factors 1, 3, and 5 characterize the ability to dissipate landing forces at the hip, knee, and ankle, respectively. Factors 2, 4, and 6 characterize the loads generated about the hip, knee, and ankle structures. Factors 7 and 8 characterize the coupled transverse- and frontal-plane motions at the hip that contribute to dynamic knee valgus. Factors 9 and 10 represent the direction and magnitude of knee rotation, and factor 11 characterizes the loading of the hip and knee structures in the transverse and frontal planes.

Table 1.

Biomechanical Factors Obtained From Principal Components Analysis

| Factor |

Factor Loadingsa |

Biomechanical Changes on Jump Landing as Factor Score Increasesb |

Functional Result |

| 1 | ↑ Peak hip flexion (0.180), flexion excursion (0.270), hip work absorption (0.431) | ↑ Hip flexion, energy absorption | ↑ Dissipation of landing forces at hip |

| 2 | ↑ Initial hip flexion (0.188), flexion moment (0.219), stiffness (0.347) | Ground contact in ↑ hip flexion; ↑ hip-flexion moment, stiffness | ↑ Loads on hip |

| 3 | ↑ Peak ankle flexion (0.332), peak knee flexion (0.235), knee-flexion excursion (0.288), knee work absorption (0.220) | ↑ Knee, ankle flexion at peak landing; ↑ knee energy absorption | ↑ Dissipation of landing forces at knee |

| 4 | ↑ Ground reaction force (0.256), anterior knee shear forces (0.343), knee-extensor moment (0.432), stiffness (0.386), work absorption (0.232) | ↑ Stiff knee on landing → ↑ knee-extensor loads, shear forces, ground reaction forces | ↑ Loads on knee |

| 5 | ↑ Initial ankle flexion (0.433); ↓ ankle-flexion excursion (−0.393) | Ground contact in ↑ ankle dorsiflexion; ↓ dorsiflexion motion on landing | ↓ Reliance on ankle motion to dissipate landing forces |

| 6 | ↑ Anterior knee shear forces (0.222), ankle-extensor moment (0.323), stiffness (0.289), work absorption (0.253) | ↑ Stiff ankle on landing → ↑ ankle plantar-flexor loads; ↑ anterior knee shear forces | ↑ Loads on ankle plantar-flexor loads, structures that restrain anterior tibial translation |

| 7 | ↑ Initial hip external rotation (0.264), initial knee (0.216) and peak knee valgus (0.213), initial knee internal rotation (−0.346); ↓ peak knee external rotation (−0.330) and knee internal-rotation excursion (0.282) | Ground contact in ↑ relative hip external rotation, knee valgus, internal rotation; remain in ↑ knee valgus, internal rotation | Knee posture associated with ↑ anterior cruciate ligament loading, injury risk during landing |

| 8 | ↑ Hip-adduction excursion (−0.183), knee-valgus excursion (0.208); ↓ peak hip internal rotation (0.260), internal-rotation excursion (0.264), peak knee varus (0.236), knee-varus excursion (0.324) | ↑ Frontal-plane hip adduction, knee-valgus motion; ↓ hip internal-rotation motion | More functional valgus posture during landing |

| 9 | ↑ Peak knee internal rotation (–.299), internal-rotation excursion (−0.229) | ↑ Knee internal-rotation motion during landing | |

| 10 | ↑ Knee external-rotation excursion (0.694) | ↑ Knee external-rotation motion during landing | |

| 11 | ↓ Hip-adduction moment (0.315), hip external-rotation moment (−0.225), knee-varus moment (0.411), knee internal-rotation moment (0.251) | ↓ Hip adduction and external rotation, knee-varus and internal-rotation moments during landing | ↓ Peak loading of structures associated with transverse, frontal control of hip, knee |

Anterior-posterior flexion angles, extensor moments, stiffness, and work-absorption values are positive.

If factor score decreases, the opposite biomechanical changes are observed.

Statistical Analyses

We used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to determine the extent to which changes in SPTIME and APLAX were associated with changes in biomechanical factors during landing across the 13 measured time points of the IEP. The HLM estimates the linear relationship among the independent (SPTIME, laxity) and dependent (biomechanical factors) variables within each participant and then measures the extent to which these individual linear relationships vary among participants. Conceptually, this is similar to running separate regression analyses for each individual, then summarizing (ie, averaging) the regression analyses across participants. It allowed us to determine whether changes in SPTIME or APLAX consistently predicted changes in each biomechanical factor score during exercise. When we used the 5 time points at which VVLAX and IERLAX were measured, a second HLM determined whether exercise-related increases in VVLAX and IERLAX predicted any of the remaining variation in each factor score (ie, the variation not explained by APLAX and SPTIME in the first analysis).

In both models, the APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX measured at baseline (PreWm) for each participant were included as covariates. This allowed us to test whether the amount of change in each factor score due to exercise-related changes in SPTIME and laxity depended on (or was moderated by) the initial APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX. Given that men and women can differ considerably in their baseline laxity, exercise-related increases in laxity,15 and landing biomechanics from before to after fatigue,21,22,28 we conducted separate analyses for men and women to better control for other covariates highly correlated with sex that might influence these relationships.

The study originally was powered to detect changes in laxity and biomechanics over time (13 repeated measures, a correlation among repeated measures conservatively estimated at r = 0.5; effect size f2 > 0.11–0.15) and to identify moderate relationships between changes in laxity and SPTIME and changes in knee biomechanics over time (4 predictor variables; effect size f2 = 0.25). Therefore, a sample size of 60 (30 per group) was required to achieve statistical power of 80% or greater. The study was not powered specifically for HLM analyses. We used SPSS software (version 20; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) to analyze the data. The α level was set at .05.

RESULTS

Yo-Yo IR1 running distances averaged 1393 ± 425 m for men and 847 ± 313 m for women. Yo-Yo IR1 results by sport have been previously reported25 and are consistent with the range in values seen in athletes performing at the recreational and subelite levels.29

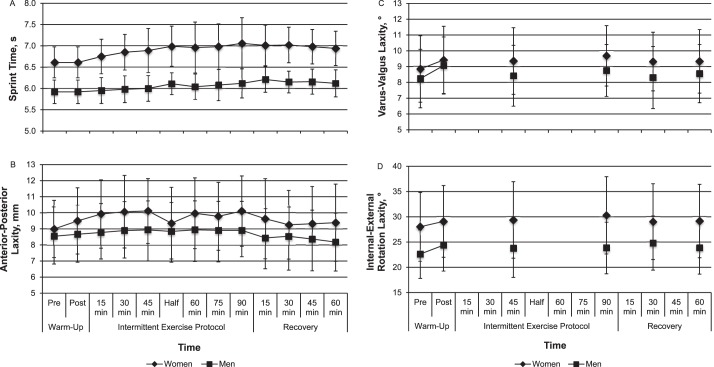

Table 1 provides a clinical description of each of the 11 biomechanical factors derived from the principal components analysis and the combination of kinematic and kinetic variables that loaded strongly on each factor.25 For descriptive purposes, Figure 3 displays the direction and magnitude of changes in SPTIME and multiplanar knee laxity during the IEP for each sex. A full reporting of these results is provided by Shultz et al.15 Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 (available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S1) display the direction and magnitude of changes in each of the 11 biomechanical factor scores during the IEP for each sex.

Figure 3.

Serial changes in, A, sprint time, B, anterior-posterior knee laxity, C, varus-valgus knee laxity, and D, internal-external rotation knee laxity before, during, and after the 90-minute intermittent exercise protocol. Statistical comparisons of these data over time were previously reported.15

Tables 2 and 3 list the findings from the HLM analyses that were different for men and women, respectively, when predicting exercise-related changes in each biomechanical factor score from exercise-related changes in SPTIME, APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX when accounting for the moderating effects of baseline knee laxity on these relationships. Complete HLM results for each factor can be found in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S2). Using factor 1 in women as an example (Table 2), the average slope for SPTIME was significantly different from zero and negative, but none of the laxity coefficients were significant, which indicates the relationship between SPTIME and factor 1 did not depend on baseline knee laxity. In this case, the ability to dissipate landing forces at the hip would decrease by an average factor score of 0.60 for every 1-second increase in SPTIME, and this relationship would not be affected by initial knee laxity. However, for factor 5 in women, the average slope for SPTIME was significantly different from zero and positive, and the coefficient for baseline IERLAX also was significantly different from zero. Thus, the effect of SPTIME was moderated by the initial IERLAX. In this case, women landed in more ankle dorsiflexion at ground contact, which reduced the available dorsiflexion motion during landing by an average factor score of 0.39 for every 1-second increase in SPTIME for an individual with average baseline laxity. However, if a woman had above-average baseline IERLAX, the increase in ankle dorsiflexion at ground contact with increasing SPTIME would be 0.07 greater than the 0.39 average expected change in the factor score for every 1° that baseline IERLAX was more than the mean (eg, total change in the factor score of 0.46 for an individual with IERLAX that was 1° more than the mean). The opposite would be true (total change in the factor score of 0.32) for an individual with IERLAX that was 1° less than the mean.

Table 2.

Significant Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results for Womena

| Biomechanical Factors |

Exercise-Related Increases in APLAX and SPTIME |

Exercise-Related Increases in VVLAX and IERLAX |

||||||||

| Slopesb |

Interceptc |

Baseline Knee Laxityd |

Slopese |

Interceptc |

Baseline Knee Laxityd |

|||||

| AP, mmd |

VV, °d |

IER, °d |

AP, mmd |

VV, °d |

IER, °d |

|||||

| 1: Greater hip-flexion motion and energy absorption | SPTIME | −0.60f | VVLAX | |||||||

| APLAX | −0.02 | −0.03f | IERLAX | |||||||

| 2: Greater initial hip-flexion and hip-extensor loading | SPTIME | −0.55f | VVLAX | |||||||

| APLAX | 0.04 | −0.01f | IERLAX | −0.03 | 0.01f | |||||

| 3: Greater knee and ankle flexion and knee energy absorption | SPTIME | −0.55 | 0.68f | −0.10f | VVLAX | 0.52f | 0.07g | |||

| APLAX | −0.08 | −0.14g | IERLAX | −0.02 | 0.02g | |||||

| 4: Greater knee-extensor loading | SPTIME | −0.32f | 0.44f | −0.45f | −0.04f | VVLAX | −0.19 | −0.03f | ||

| APLAX | 0.23g | 0.02g | IERLAX | −0.01 | 0.06f | −0.08f | 0.01f | |||

| 5: Greater initial ankle dorsiflexion with less excursion | SPTIME | 0.39f | 0.07f | VVLAX | 0.36g | |||||

| APLAX | −0.08 | −0.03g | IERLAX | |||||||

| 6: Greater ankle plantar-flexor loading and knee shear forces | SPTIME | −0.41f | VVLAX | |||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | |||||||||

| 7: Began and remained in greater hip external rotation, knee valgus, and knee internal rotation | SPTIME | −0.51f | VVLAX | |||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | −0.05 | −0.04g | 0.05g | ||||||

| 8: Greater pure frontal-plane knee-valgus motion | SPTIME | VVLAX | 0.34f | 0.24f | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | 0.05f | 0.01f | |||||||

| 9: Greater knee internal-rotation motion during landing | SPTIME | VVLAX | ||||||||

| APLAX | 0.19f | 0.12g | 0.02g | IERLAX | ||||||

| 10: Greater knee external-rotation motion during landing | SPTIME | 0.61f | 0.79g | VVLAX | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | 0.05 | −0.04g | 0.01g | ||||||

| 11: Less frontal- and transverse-plane hip and knee loading | SPTIME | VVLAX | −0.16 | 0.29g | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | |||||||||

Abbreviations: AP, anterior-posterior; APLAX, anterior-posterior knee laxity; IER, internal-external rotation; IERLAX, internal-external rotation knee laxity; SPTIME, sprint time; VV, varus-valgus; VVLAX, varus-valgus knee laxity.

The nonsignificant findings that are not included in this Table can be found in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S2).

SPTIME and APLAX slopes describe the extent to which exercise-related changes in SPTIME and APLAX, respectively, predict exercise-related changes in each biomechanical factor within a person.

The intercept represents the average expected change in the factor score for every unit change in the predictor variable (ie, 1-second change in SPTIME, 1-mm change in APLAX, and 1° change in VVLAX and IERLAX).

The baseline laxity coefficients represent the extent to which an individual's initial knee-laxity measures (APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX at pre-warm-up) moderate the relationship (or slope) between the independent variable (eg, SPTIME) and the factor score. Specifically, for an individual with a baseline knee-laxity value that is 1 unit value above or below the group mean, the average expected change (ie, slope of the intercept) is predicted to increase or decrease, respectively, by that amount.

The VVLAX and IERLAX slopes describe the extent to which exercise-related changes in VVLAX and IERLAX, respectively, predict additional exercise-related changes in each biomechanical factor that was not previously explained by SPTIME and APLAX.

Indicates coefficient (slope) is different from zero (P < .05).

Indicates coefficient (slope) is different from zero (P < .10).

Table 3.

Significant Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results for Mena

| Biomechanical Factors |

Exercise-Related Increases in APLAX and SPTIME |

Exercise-Related Increases in VVLAX and IERLAX |

||||||||

| Slopesb |

Interceptc |

Baseline Knee Laxityd |

Slopese |

Interceptc |

Baseline Knee Laxityd |

|||||

| AP, mmd |

VV, °d |

IER, °d |

AP, mmd |

VV, °d |

IER, °d |

|||||

| 1: Greater hip-flexion motion and energy absorption | SPTIME | 0.20 | −0.08f | VVLAX | ||||||

| APLAX | 0.17f | IERLAX | 0.03 | 0.01f | ||||||

| 2: Greater initial hip-flexion and hip-extensor loading | SPTIME | −1.08f | −0.16f | VVLAX | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | |||||||||

| 3: Greater knee and ankle flexion and knee energy absorption | SPTIME | VVLAX | ||||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | |||||||||

| 4: Greater knee-extensor loading | SPTIME | −0.54 | 2.30f | −1.63f | 0.16f | VVLAX | ||||

| APLAX | 0.14f | −0.03f | IERLAX | |||||||

| 5: Greater initial ankle dorsiflexion with less excursion | SPTIME | VVLAX | ||||||||

| APLAX | 0.17g | −0.26f | 0.17f | IERLAX | ||||||

| 6: Greater ankle plantar-flexor loading and knee shear forces | SPTIME | −0.57 | 0.97f | VVLAX | 0.23 | −0.61f | 0.55f | |||

| APLAX | IERLAX | 0.02 | 0.07f | |||||||

| 7: Began and remained in greater hip external rotation, knee valgus, and knee internal rotation | SPTIME | −0.26 | −0.28f | VVLAX | 0.37f | −0.56f | 0.38f | |||

| APLAX | IERLAX | −0.05 | 0.08g | |||||||

| 8: Greater pure frontal-plane knee-valgus motion | SPTIME | −0.94g | VVLAX | 0.01 | 0.05f | |||||

| APLAX | −0.05 | 0.16f | −0.12f | −0.03g | IERLAX | −0.06g | ||||

| 9: Greater knee internal-rotation motion during landing | SPTIME | 0.32 | −0.63g | VVLAX | −0.21 | −0.07f | ||||

| APLAX | 0.04 | 0.08f | −0.08f | 0.02g | IERLAX | |||||

| 10: Greater knee external-rotation motion during landing | SPTIME | 0.11 | 0.05g | VVLAX | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | 0.02 | 0.07f | −0.07f | ||||||

| 11: Less frontal- and transverse-plane hip and knee loading | SPTIME | 0.10 | −0.12f | VVLAX | ||||||

| APLAX | IERLAX | −0.07g | ||||||||

Abbreviations: AP, anterior-posterior; APLAX, anterior-posterior knee laxity; IER, internal-external rotation; IERLAX, internal-external rotation knee laxity; SPTIME, sprint time; VV, varus-valgus; VVLAX, varus-valgus knee laxity.

The nonsignificant findings that are not included in this Table can be found in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S2).

SPTIME and APLAX slopes describe the extent to which exercise-related changes in SPTIME and APLAX, respectively, predict exercise-related changes in each biomechanical factor within a person.

The intercept represents the average expected change in the factor score for every unit change in the predictor variable (ie, 1-second change in SPTIME, 1-mm change in APLAX, and 1° change in VVLAX and IERLAX).

The baseline laxity coefficients represents the extent to which an individual's initial knee laxity measures (APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX at pre-warm-up) moderate the relationship (or slope) between the independent variable (eg, SPTIME) and the factor score. Specifically, for an individual with a baseline knee-laxity value that is 1 unit value above or below the group mean, the average expected change (ie, slope of the intercept) is predicted to increase or decrease, respectively, by that amount.

The VVLAX and IERLAX slopes describe the extent to which exercise-related changes in VVLAX and IERLAX, respectively, predict additional exercise-related changes in each biomechanical factor that was not previously explained by SPTIME and APLAX.

Indicates coefficient (slope) is different from zero (P < .05).

Indicates coefficient (slope) is different from zero (P < .10).

Predicting Changes in Biomechanical Factors From Changes in SPTIME

Among women, changes in SPTIME consistently predicted changes in factors 1, 2, 4–7, and 10. In general, as SPTIME in women slowed with fatigue, they landed with more ankle dorsiflexion (factor 5); reduced their hip-flexion motion and energy absorption (factor 1); and reduced their hip-, knee-, and ankle-extensor loads and knee shear forces (factors 2, 4, and 6). In the frontal and transverse planes, women exhibited more neutral knee alignment at ground contact (factor 7; less knee valgus and rotation) and greater knee external-rotation excursion during the landing (factor 10) as they fatigued.

For the biomechanical factors that described sagittal-plane knee motions and loads upon landing (factors 3 and 4), changes in these factors with changes in SPTIME were moderated by baseline knee laxity in women. Knee-extensor loads (factor 4) and knee and ankle flexion and energy absorption (factor 3) increased as SPTIME increased in women who had greater relative APLAX at baseline (ie, above-average APLAX but average or below-average VVLAX and IERLAX), whereas these variables decreased in women with average or below-average APLAX at baseline. Hence, the moderating effect of baseline knee laxity on the relationship between SPTIME and sagittal-plane biomechanics largely depends on the relative magnitude of APLAX as compared with VVLAX and IERLAX at baseline.

For men, the only consistent relationship we observed between changes in SPTIME and changes in the biomechanical factors was for factor 2: an increase in SPTIME predicted less initial hip flexion at ground contact and reduced hip-extensor loads during landing. This relationship tended to be stronger in men who initially had more IERLAX. For other biomechanical factors (factors 1, 4, 6, 7, and 11), relationships with SPTIME were moderated by baseline knee laxity (Table 3). Men with greater initial APLAX were predicted to increase the loads generated in the sagittal plane about the knee (factor 4) and ankle structures (factor 6) as they fatigued, whereas men with average or below-average baseline APLAX were predicted to decrease the loads about the knee and ankle as they fatigued. Men with above-average IERLAX were more likely to decrease their hip-flexion motion and energy absorption (factor 1), decrease their knee valgus and internal rotation (factor 7), and increase their frontal- and transverse-plane hip and knee moments (factor 11) as they fatigued.

Predicting Changes in Biomechanical Factors From Changes in APLAX

On average, exercise-related increases in APLAX predicted greater increases in knee internal-rotation motion (factor 9) in women. The extent to which exercise-related changes in APLAX predicted changes in sagittal-plane hip biomechanics (factors 1 and 2) was moderated by the baseline IERLAX of women. Specifically, increases in APLAX during exercise were more likely to predict reductions in hip flexion, hip-extensor loads, and hip energy absorption upon landing in women who had above-average IERLAX at baseline.

In men, an increase in APLAX with exercise consistently predicted an increase in hip-flexion motion and energy absorption (factor 1) and knee-extensor loads (factor 4). Further, the predicted increase in knee-extensor loads with increasing APLAX was greater in men who had less relative baseline IERLAX. For other biomechanical factors, men with greater relative baseline APLAX (ie, above-average APLAX with below-average VVLAX) were more likely to land initially in less dorsiflexion (factor 5) and go through greater dorsiflexion (factor 5), knee valgus (factor 8), and knee internal rotation (factor 9) during landing as APLAX increased with exercise.

Predicting Changes in Biomechanical Factors From Changes in VVLAX and IERLAX

After accounting for the effects of APLAX and SPTIME, greater exercise-related increases in VVLAX and IERLAX consistently predicted greater increases in frontal-plane knee-valgus motion (factor 8) in women. This relationship was more pronounced if women initially had more VVLAX and IERLAX. Women who increased their VVLAX during exercise also were more likely to increase their knee and ankle flexion and knee energy absorption (factor 3) during landing. Relationships between changes in VVLAX and IERLAX with hip-extensor loading (factor 2) and knee-extensor loading (factor 4) were not as consistent and depended more on the initial knee laxity in women (Table 2).

On average, exercise-related increases in VVLAX in men predicted greater positioning of the hip and knee toward dynamic knee valgus (factor 7), and this relationship was stronger in men who had greater relative VVLAX than APLAX at baseline. Relationships between increases in VVLAX and IERLAX with frontal-plane knee valgus (factor 8), hip-flexion motion and energy absorption (factor 1), ankle plantar-flexor loading and knee shear forces (factor 6), and knee internal-external rotation (factors 9 and 10) were not as consistent and depended more on the baseline knee laxity of participants (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

During the 90-minute IEP, we observed changes in landing biomechanics that were dependent on the magnitude of fatigue (as measured by SPTIME) and the magnitude of change in knee laxity with exercise. Fatigue-related increases in SPTIME were associated with decreased landing forces and out-of-plane motions about the knee, whereas exercise-related increases in knee laxity were more likely to be associated with greater knee-extensor loads and knee-shear forces and greater dynamic knee valgus. These relationships often depended on the relative magnitude of baseline knee laxity. Our discussion addresses fatigue-related changes in landing biomechanics followed by laxity-related effects. We also consider the clinical implications of these findings on the risk of knee injury during prolonged intermittent exercise.

Biomechanical Changes With Increasing SPTIME

We consistently observed broad biomechanical changes (contacting the ground in a more upright landing position; greater dorsiflexion throughout the landing; and decreased stiffness, extensor loads, and ability to dissipate landing forces at the hip, knee, and ankle) in women as SPTIME increased. However, the only consistent relationship we observed in men with increasing SPTIME was a decrease in hip-flexion and hip-extensor loading. Unlike women, men did not demonstrate reductions in joint motion or energy absorption at the hip and knee (factors 1 and 3) with fatigue-related reductions in SPTIME, suggesting that they retained a greater overall ability to dissipate landing forces as they fatigued during the IEP.

The biomechanical changes we observed in women as SPTIME increased, in part, are consistent with other reports of decreasing flexion angles, joint-extensor moments, and ground reaction forces in women during other types of fatiguing exercise.21,28,30 However, direct comparisons of our findings with those reported in other studies are difficult given differences in the fatigue protocols (eg, length, intensity, and type of exercise), the functional tasks performed, and the biomechanical variables studied. We are the first, to our knowledge, to use a principal components analysis to group related biomechanical variables to gain a more global picture of changes in multijoint strategies and to examine fatigue-related changes in biomechanics during prolonged intermittent exercise while also accounting for changes related to knee laxity.

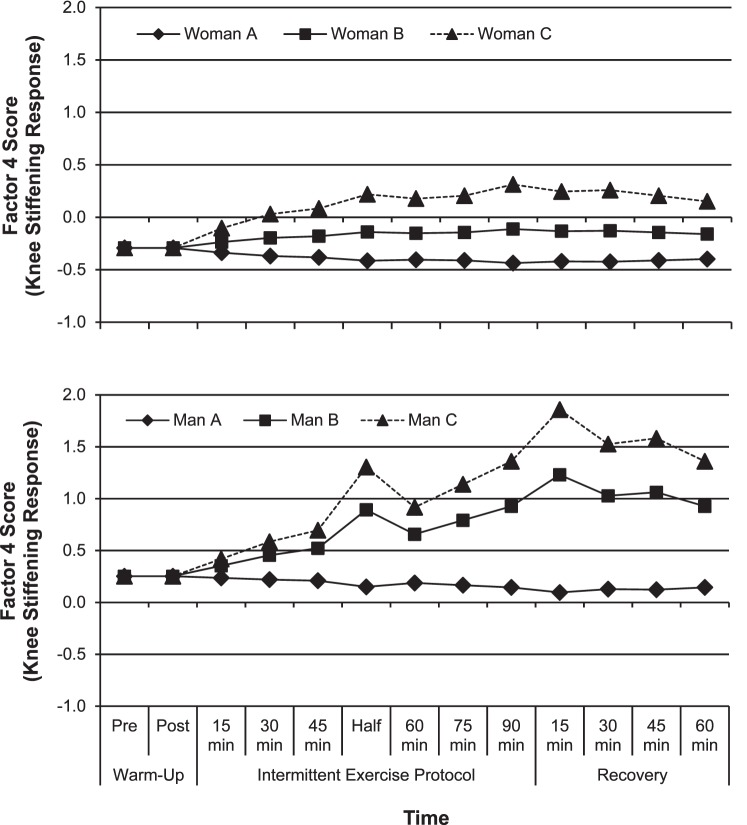

In both men and women, the loads produced on the knee structures with increasing SPTIME depended on how much knee laxity an individual had initially. Specifically, participants who had greater relative APLAX at baseline were more likely to increase knee stiffness and the loads produced on the knee structures on landing (men and women), increase ankle plantar-flexor loads and knee shear loads (men), and increase the amount of landing forces absorbed at the knee (women) as they fatigued. However, in individuals with average or below-average APLAX at baseline, these same biomechanical factors were expected to decrease with fatigue. To illustrate the magnitude of this effect, we compared the estimated rate (and direction) of change in factor 4 (how stiffly an individual landed and, thus, his or her generation of knee-extensor loads, shear forces, and ground reaction forces, accordingly) as SPTIME increased in men and women under 3 baseline knee-laxity conditions (Figure 4). The first participant (A) had average baseline APLAX, VVLAX, and IERLAX. The second participant (B) had above-average (+1 SD above the mean) baseline APLAX (9.0 mm versus 10.8 mm in women, 8.5 mm versus 10.2 mm in men) but average VVLAX and IERLAX. The third participant (C) had above-average APLAX but below-average (−1 SD below the mean) VVLAX (8.8° versus 6.7° in women, 8.2° versus 6.4° in men) and IERLAX (28.0° versus 21.2° in women, 22.6° versus 17.8° in men). Each participant represents a realistic laxity profile in men and women.31 These data clearly show the predicted change in knee stiffness during landing; thus, the loads imparted on the knee structures with fatiguing exercise are substantially higher in those with greater absolute and relative APLAX. Given that biomechanical changes at the hip and ankle with fatigue were relatively unaffected by baseline APLAX, the loads on the knee structures would be accentuated as performance declined in individuals with above-average APLAX.

Figure 4.

Exemplar data depicting the predicted changes in the knee-stiffening response (factor 4) between women (top graph) and men (bottom graft) with, A, average baseline knee laxity, B, above-average anterior-posterior knee laxity (APLAX; +1 SD above the mean), but average varus-valgus knee laxity (VVLAX) and internal-external rotation knee laxity (IERLAX), and C, above-average APLAX but below-average VVLAX and IERLAX (−1 SD below the mean).

Our finding that women with high APLAX demonstrated both greater energy absorption and stiffness at the knee is consistent with previous research.9 The combination of greater knee stiffening and energy absorption may reflect an attempt to increase sagittal-plane knee stability while working to limit high axial forces. Clinically, this strategy may be less efficient from a performance and injury-reduction standpoint, as a more absorptive landing may limit the ability to respond quickly to a potentially injurious situation.9,32 Additionally, this effect may be accentuated in men with above-average IERLAX at baseline, who were more likely to maintain a more extended hip (factor 1) and more neutral hip and knee alignment (factor 7) and to generate greater knee-extensor loads (factor 4) while generating lesser hip-extensor loads (factor 2) and lesser frontal- and transverse-plane knee loads (factor 11) as SPTIME increased. The combination of a more extended hip with greater knee-extensor and knee-shear loads as SPTIME increased in men with above-average APLAX and IERLAX may further increase the potential for sagittal-plane knee loading and ACL strain.

Biomechanical Changes With Increasing Laxity

After accounting for fatigue-related effects (SPTIME), changes in knee laxity predicted additional changes in lower extremity biomechanics during exercise, and these relationships differed for men and women. In women, increases in APLAX during exercise were consistently associated with greater knee internal-rotation motion, whereas increases in VVLAX and IERLAX during exercise consistently were associated with greater functional knee valgus, greater knee and ankle flexion, and greater knee energy absorption. These relationships tended to be stronger in participants who initially had more knee laxity. The APLAX represents an in vivo measure of tibiofemoral-joint displacement, which the ACL restrains in the anterior direction.33 Given that the ACL controls both anterior translation and internal rotation of the tibia relative to the femur,34,35 it seems reasonable that, as APLAX increases with exercise, a concomitant increase in internal rotation of the tibia would occur. This would be particularly true during weight-bearing activity when anterior translation of the tibia occurs relative to the femur,35 with the lateral femoral condyle translating more than the medial side because of the greater slope of the lateral than the medial tibial plateau.36

The increase in frontal-plane knee motion in women with exercise-related increases in VVLAX and IERLAX is consistent with findings of investigators10 who reported greater hip-adduction and knee-valgus motion in women with greater baseline VVLAX and IERLAX. Their work also supports our observation of stronger associations between increases in VVLAX and IERLAX and knee-valgus motion during exercise in women who had greater initial VVLAX and IERLAX. Together, these findings suggest that women who begin with more VVLAX and IERLAX and who experience greater increases in VVLAX and IERLAX during prolonged intermittent exercise may be particularly vulnerable to dynamic knee-valgus motion later in a game or practice. Given that the combination of knee valgus and knee internal rotation is known to place the greatest strain on the ACL,37 increases in both sagittal-plane knee laxity and combined transverse- and frontal-plane knee laxity during exercise may be particularly concerning for these women. However, a more lax knee is expected to displace farther than a less lax knee at the same externally applied load, so more research is needed to fully understand how these multiplanar changes in knee laxity differentially affect knee arthrokinematics and ACL strain early in the landing phase.17

The increase in knee and ankle flexion and knee energy absorption (factor 3) with exercise-related increases in VVLAX during exercise is more difficult to interpret. The average increase in VVLAX during exercise was about 1° for this group of women, with 33% (n = 10) of the women experiencing VVLAX increases of 2.8° or more.15 Changes of this magnitude predicted an almost 1-SD change in the factor score, suggesting that this relationship may be substantial. Given that greater joint flexion and energy absorption are thought to reduce impact stress on soft tissues,38 women with greater changes in frontal-plane joint laxity and out-of-plane motions may be attempting to land in a way that reduces peak destabilizing forces at ground contact.

In men, exercise-related increases in APLAX were associated with an increased ability to dissipate landing forces at the hip (factor 1) while producing greater stiffening of and loads on the knee structures (factor 4). This sagittal-plane strategy suggests an attempt to stiffen and stabilize the knee at ground contact while reducing overall ground reaction forces through a more absorptive landing at the hip. The increased knee-stiffening response with increasing APLAX is also consistent with the increase in knee-stiffening response associated with fatigue in those who had greater initial APLAX at baseline. Therefore, men who have greater initial APLAX and who experience greater increases in APLAX with exercise may accentuate this knee-stiffening response and transfer greater loads to the knee structures as exercise progresses. This may be clinically important, as a stiffer knee landing that increases ground reaction forces and shear loads38 would further accentuate the potential for anterior tibial translation,39 which already is enhanced with greater APLAX.7 More study is needed to determine whether the increases in hip flexion and absorption are sufficient to offset this stiffening response at the knee. Modeling or computational studies may be needed to understand the effect of these multijoint strategies on joint loads and ligament strain behavior.

In men, we also observed a relationship between exercise-related increases in VVLAX and greater positioning in hip external and knee internal rotation and knee valgus (factor 7). Whereas this relationship is somewhat consistent with what we observed in women, the increase in VVLAX was more likely to affect the initial and peak positioning of the hip and knee angles in men (ie, they began and ended in greater hip external rotation, knee valgus, and knee internal rotation; factor 7). As with women, this relationship was stronger in those who initially had greater VVLAX. Unique to men was that several of the relationships between exercise-related increases in knee laxity and knee-joint biomechanics depended on the relative amount of baseline APLAX versus VVLAX. Specifically, men who had greater relative APLAX than VVLAX at baseline demonstrated less ankle dorsiflexion (factor 7) but greater frontal-plane knee valgus (factor 8) and knee internal rotation (factor 9) as APLAX increased during exercise, greater increases in knee external rotation (factor 10) as IERLAX increased during exercise, and decreases in ankle plantar-flexion loading (factor 6) and dynamic valgus position (factor 7) as VVLAX increased during exercise. Appreciating that neither baseline knee laxity31 nor exercise-related increases in knee laxity15 are uniform across planes of motion, these findings represent a complex relationship between multiplanar knee laxity and their effects on 3-dimensional landing biomechanics during prolonged, intermittent exercise.

In summary, we observed laxity-related changes in high-risk landing biomechanics during prolonged, intermittent exercise that were independent of fatigue-related performance decrements. Moreover, the tendency toward higher-risk landing biomechanics with exercise-related increases in knee laxity were often more pronounced in participants who initially had greater knee laxity at baseline. These findings suggest that movement strategies used later in a game, when athletes are fatigued, may differ markedly from strategies used when they are rested. Moreover, the amount of knee laxity (both initially at baseline and the magnitude of change during exercise) may compound these fatigue-related effects by contributing to higher-risk knee biomechanics (greater dynamic knee valgus, greater stiffening of and loads produced at the knee), thus increasing the potential for injury later in a competitive or exercise session. These laxity-dependent biomechanical changes are of particular concern in women, who tend to have greater baseline knee laxity and are more likely to increase their knee laxity during exercise than men.15 Collectively, these findings provide additional insight into the mechanisms by which greater knee-joint laxity may be associated with ACL injury risk.1–3,5,6,25 Although knee laxity often is considered a nonmodifiable anatomic risk factor, researchers40 who noted strong correlations between knee-joint laxity and muscle mass about the knee have suggested that reductions in knee laxity through strength-training interventions may be plausible.

These findings are limited to the type of intermittent activity performed and the predictor variables studied (ie, fatigue as measured by SPTIME and knee laxity). Ultimately, how resilient one may be to changes in biomechanical strategies during prolonged intermittent exercise and how protective those strategies are may depend on additional factors beyond knee laxity and physical capacity. Researchers should explore additional factors (eg, physical characteristics, such as lower extremity posture, joint geometry, body composition, strength) that may further moderate changes in landing biomechanics during prolonged physical activity and, in turn, render an individual more or less prone to higher-risk biomechanics and injury later in a practice or game. Understanding these potential modifiers of fatigue-related effects may lead to targeted neuromuscular interventions so that vulnerable athletes can be taught to safely compensate for these changes while fatigued.

These findings also are limited to the independent contributions of each predictor (ie, SPTIME, APLAX, VVLAX, IERLAX). Given the already complex nature of this study and the fact that our study was not powered to do so, we did not examine interactions between exercise-related changes in SPTIME and laxity with exercise changes in landing biomechanics. Examining these interactions in future studies may be important, as women with above-average frontal- and transverse-plane knee laxity are reported to rely more heavily on active muscle forces to control a similar type of landing than those with below-average knee laxity.10 Thus, muscular fatigue may occur more quickly in these individuals during prolonged exercise, further compromising knee-joint biomechanics as fatigue reduces the capacity of the muscle to stabilize the joint.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by a grant from the National Football League Charities. We thank Timothy Copple for his assistance with this project.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental Figures, found at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S1 (632.8KB, pdf)

Supplemental Tables, found at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.5.08.S2 (32.1KB, docx)

REFERENCES

- 1.Branch TP, Browne JE, Campbell JD, et al. Rotational laxity greater in patients with contralateral anterior cruciate ligament injury than healthy volunteers. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(10):1379–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-1010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scerpella TA, Stayer TJ, Makhuli BZ. Ligamentous laxity and non-contact anterior cruciate ligament tears: a gender based comparison. Orthopaedics. 2005;28(7):656–660. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20050701-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodford-Rogers B, Cyphert L, Denegar CR. Risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury in high school and college athletes. J Athl Train. 1994;29(4):343–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramesh R, VonArx O, Azzopardi T, Schranz PJ. The risk of anterior cruciate ligament rupture with generalised joint laxity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(6):800–803. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B6.15833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Nick TG, Hewett TE. The effects of generalized joint laxity on risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury in young female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1073–1080. doi: 10.1177/0363546507313572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhorchak JM, Scoville CR, Williams GN, Arciero RA, St Pierre P, Taylor DC. Risk factors associated with non-contact injury of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):831–842. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310061801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shultz SJ, Shimokochi Y, Nguyen AD, et al. Non-weight bearing anterior knee laxity is related to anterior tibial translation during transition from non-weight bearing to weight bearing. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(3):516–523. doi: 10.1002/jor.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ, Nguyen AD, et al. Knee laxity and its cyclic variations influence tibiofemoral joint motion during weight acceptance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(2):287–295. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed118d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ, Nguyen AD, Levine BJ. Joint laxity is related to lower extremity energetics during a drop jump landing. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(4):771–780. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181bbeaa6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ. Effects of transverse and frontal plane knee laxity on hip and knee neuromechanics during drop landings. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1821–1830. doi: 10.1177/0363546509334225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Withrow TJ, Huston LJ, Wojtys EM, Ashton-Miller JA. The effect of an impulsive knee valgus moment on in vitro relative ACL strain during a simulated jump landing. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21(9):977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nawata K, Teshima R, Morio Y, Hagino H, Enokida M, Yamamoto K. Anterior-posterior knee laxity increased by exercise: quantitative evaluation of physiological changes. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(3):261–264. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner ME, Grana WA, Chillag K, Schelberg-Karnes E. The effect of exercise on anterior-posterior knee laxity. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(1):24–29. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoller DW, Markolf KL, Zager SA, Shoemaker SC. The effects of exercise, ice, and ultrasonography on torsional laxity of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(174):172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ, Cone JR, et al. Multiplanar knee laxity increases during a 90-min intermittent exercise protocol. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(8):1553–1561. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828cb94e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkins RD, Hulse MA, Wilkinson C, Hodson A, Gibson M. The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(1):43–47. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ, Kong Y, et al. Cyclic variations in multi-planar knee laxity influence landing biomechanics. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(5):900–909. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823bfb25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SK, Stefanyshyn DJ, Ramage B, Hart DA, Ronsky JL. Alterations in knee joint laxity during the menstrual cycle in healthy women leads to increases in joint loads during selected athletic movements. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1169–1177. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannsen HV, Lind T, Jakobsen BW, Kroner K. Exercise-induced knee joint laxity in distance runners. Br J Sports Med. 1989;23(3):165–168. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.23.3.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borotikar BS, Newcomer R, Koppes R, McLean SG. Combined effects of fatigue and decision making on female lower limb landing postures: central and peripheral contributions to ACL injury risk. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008;23(1):81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappell JD, Herman DC, Knight BS, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, Yu B. Effect of fatigue on knee kinetics and kinematics in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1022–1029. doi: 10.1177/0363546504273047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLean SG, Fellin R, Suedekum N, Calabrese G, Passerallo A, Joy S. Impact of fatigue on gender-based high-risk landing strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(3):502–514. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180d47f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marx RG, Stump TJ, Jones EC, Wickiewiecz TL, Warren RF. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):213–218. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cone JR, Berry NT, Goldfarb AH, et al. Effects of an individualized soccer match simulation on vertical stiffness and impedance. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2027–2036. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz RJ, Shultz SJ, Cone JR, et al. Changes in drop jump landing biomechanics during prolonged intermittent exercise. Sports Health. 2014;6(2):128–135. doi: 10.1177/1941738113503286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbett TJ, Kelly JN, Sheppard JM. Speed, change of direction speed, and reactive agility of rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(1):174–181. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815ef700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Draper JA, Lancaster MG. The 505 test: a test for agility in the horizontal plane. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1985;17(1):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kernozek TW, Torry MR, Iwasaki M. Gender differences in lower extremity landing mechanics caused by neuromuscular fatigue. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(3):554–565. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bangsbo J, Iaia FM, Krustrup P. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: a useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Med. 2008;38(1):37–51. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortes N, Quammen D, Lucci S, Greska E, Onate JA. A functional agility short-term fatigue protocol changes lower extremity mechanics. J Sport Sci. 2012;30(8):797–805. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.671528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shultz SJ, Dudley WN, Kong Y. Identifying knee laxity profiles and associated physical characteristics. J Athl Train. 2012;47(2):159–169. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horita T, Komi PV, Nicol C, Kyröläinen H. Interaction between pre-landing activities and stiffness regulation of the knee joint musculoskeletal system in the drop jump: implications to performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;88((1–2)):76–84. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler DL, Noyes FR, Grood ES. Ligamentous restraints to anterior-posterior drawer in the human knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(2):259–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Shepard MF, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Combined knee loading states that generate high anterior cruciate ligament forces. J Orthop Res. 1995;13(6):930–935. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torzilli PA, Deng X, Warren RF. The effect of joint-compressive load and quadriceps muscle force on knee motion in the intact and anterior cruciate ligament-sectioned knee. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):105–112. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashemi J, Chandrashekar N, Gill B, et al. The geometry of the tibial plateau and its influence on the biomechanics of the tibiofemoral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2724–2734. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanamori A, Woo SL, Ma CB, et al. The forces in the anterior cruciate ligament and knee kinematics during a simulated pivot shift test: a human cadaveric study using robotic technology. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(6):633–639. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.7682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devita P, Skelly WA. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(1):108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitz RJ, Kim H, Shultz SJ. Effect of axial load on anterior tibial translation when transitioning from non-weight bearing to weight bearing. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2010;25(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shultz SJ, Pye ML, Montgomery MM, Schmitz RJ. Associations between lower extremity muscle mass and multi-planar knee laxity and stiffness: a potential explanation for sex differences in frontal and transverse plane knee laxity. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(12):2836–2844. doi: 10.1177/0363546512461744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]