Abstract

Objective

While gout is associated with cardiovascular (CV)-metabolic comorbidities and their sequelae, the antioxidant effects of uric acid may have neuroprotective benefits. We evaluated the potential impact of incident gout on the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in a general population context.

Methods

We conducted an age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched and body mass index (BMI)-matched cohort study using data from The Health Improvement Network, an electronic medical record database representative of the UK general population, from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2013. Up to five non-gout individuals were matched to each case of incident gout by age, sex, year of enrolment and BMI. We compared incidence rates of AD between the gout and comparison cohorts, excluding individuals with prevalent gout or dementia at baseline. Multivariate hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated, while adjusting for smoking, alcohol use, physician visits, social deprivation index, comorbidities and medication use. We repeated the same analysis among patients with incident osteoarthritis (OA) as a negative control exposure.

Results

We identified 309 new cases of AD among 59 224 patients with gout (29% female, mean age 65 years) and 1942 cases among 238 805 in the comparison cohort over a 5-year median follow up (1.0 vs 1.5 per 1000 person-years, respectively). Univariate (age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched and BMI-matched) and multivariate HRs for AD among patients with gout were 0.71 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.80) and 0.76 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.87), respectively. The inverse association persisted among subgroups stratified by sex, age group (<75 and ≥75 years), social deprivation index and history of CV disease. The association between incident OA and the risk of incident AD was null.

Conclusions

These findings provide the first general population-based evidence that gout is inversely associated with the risk of developing AD, supporting the purported potential neuroprotective role of uric acid.

INTRODUCTION

Hyperuricaemia is the key causal precursor for gout, the most common inflammatory arthritis, and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular (CV)-renal comorbidities and their sequelae.1–5 However, as a major natural antioxidant in the body, uric acid has been estimated to account for more than 50% of the antioxidant capacity of plasma.6 Furthermore, the antioxidant properties of uric acid have been hypothesised to protect against the development or progression of neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (PD).7–9

With these potentially neuroprotective properties, uric acid has been hypothesised to protect against oxidative stress, a prominent contributor to dopaminergic neuron degeneration in PD,9,10 which may also play an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).11,12 Indeed, a prospective, population-based study has found that higher serum uric acid (SUA) levels were associated with a lower risk of incident dementia over an 11 year follow-up period (HR adjusted for age, sex and CV risk factors, 0.89 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.99) per SD increase of SUA).13 Furthermore, the same study found that higher SUA levels at baseline were associated with better cognitive function later in life, for all cognitive domains. Notably, this study investigated overall dementia, thus including both AD and vascular dementia. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between gout and the risk of AD. In this study, we evaluated the potential impact of incident gout on the risk of developing AD in a general population context.

METHODS

Data source

The Health Improvement Network (THIN) is a computerised medical record database from general practices in the UK.14 Data on approximately 10.2 million patients from 580 general practices are systematically recorded by general practitioners (GPs) and sent anonymously to THIN. Because the National Health Service in the UK requires every individual to be registered with a GP regardless of health status, THIN is a population-based cohort representative of the UK general population. The computerised information includes demographics, details from GP visits, diagnoses from specialists’ referrals and hospital admissions, results of laboratory tests and additional systematically recorded health information including height, weight, blood pressure, smoking status and vaccinations. The Read classification is used to code specific diagnoses,15 and a drug dictionary based on data from the Multilex classification is used to code drugs.16 Health information is recorded onsite at each practice using a computerised system with quality control procedures to maintain high data completion rates and accuracy.

Study design

The study population included individuals aged ≥40 years who had at least 1 year of active enrolment with the general practice during 1 January1995–31 December 2013 (n=3 727 437). Individuals diagnosed with gout or any dementia prior to the start of follow-up were excluded. We conducted a cohort analysis of AD among adults with incident gout compared with up to five non-gout individuals matched by age, date of study entry, enrolment year and body mass index (BMI) within a calliper of ±0.5 kg/m2 (comparison cohort) using data from THIN. We matched on BMI, as obesity is a strong risk factor for gout17 and has been consistently associated with dementia.18,19 Participants entered the cohort when all inclusion criteria were met or on the matched date for subjects in the comparison cohort (index date), and were followed until they developed AD, died, left the THIN database or the follow-up ended, whichever came first.

Gout case ascertainment

Gout was defined by diagnostic code using the Read classification.20 Through a computer search using Read codes, we identified all patients with a first-ever diagnosis of gout recorded by a GP (n=59 224). This date of gout diagnosis was the index date. To evaluate the robustness of gout case ascertainment, we performed a sensitivity analysis where we restricted gout cases to those with a gout diagnosis plus those receiving gout treatment (colchicine or urate-lowering drugs (ie, allopurinol, febuxostat or probenecid)) (n=31 799). A similar case definition of gout has been shown to have a validity of 90% in the General Practice Research Database (GPRD),21,22 in which 60% of patients overlap with THIN.

AD ascertainment

Our primary outcome was the first recorded diagnosis of AD (see online supplementary table S1 for the list of AD diagnostic codes). The dementia codes were shown to have a positive predictive value of 83% in a validation study based on the UK GPRD.23 The incidence rates (IRs) of AD per 1000 person-years in our cohort according to age categories <75 years and 75–90 years were 0.6 and 4.0 cases among men and 1.2 and 4.8 cases among women, respectively. These rates were comparable with previous estimates from the GPRD database24 and other population-based studies.25

Assessment of covariates

All comorbidities, lifestyle factors, social–economic deprivation index (SDI), use of CV drugs and healthcare use (ie, GP visits) were collected prior to the index date. Specifically, comorbidities included a history of ischaemic heart disease, stroke, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus. Lifestyle factors such as BMI, smoking status and alcohol consumption were recorded to the nearest possible measurement prior to the index date. The SDI was measured by the Townsend Deprivation Index Score, which was grouped into quintiles from 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived).26,27 Use of CV drugs (ie, aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) and the number of visits to a GP were ascertained within 1 year prior to the index date.

A comparison analysis of osteoarthritis as a negative control exposure

As there has been no purported association between osteoarthritis (OA) and AD, we used the same approach to analyse the risk of incident AD among patients with incident OA (n=206 664) as compared with 828 018 age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched and BMI-matched individuals without OA.

Statistical analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics between gout and comparison cohorts. We identified incident cases of AD during the follow-up and calculated the eligible person-time and IRs. We then estimated the cumulative incidence of AD in each cohort, accounting for the competing risk of death.28 Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to calculate HRs after accounting for matched clusters (age, sex, entry-time and BMI). Our intermediate multivariate model was adjusted for lifestyle factors (smoking and alcohol consumption), and GP visits, whereas our full multivariate model adjusted additionally for comorbidities and CV medication use. In all multivariate models, we additionally adjusted for BMI as a continuous variable to eliminate residual confounding. Stepwise adjustments for adding each covariate into the model were also presented to display the impact of each covariate adjustment. In addition, we conducted further subgroup analyses by sex, age group (<75 years vs 75–90 years), social deprivation index (≤2: low depravity vs >2: high depravity) and comorbidity (ie, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and CV disease). We tested the significance of heterogeneity with a likelihood ratio test by comparing a model with the main effects, the stratifying variable and the interaction terms to a reduced model with only the main effects. For all analyses, missing values for covariates (ie, smoking and alcohol use) were imputed by a sequential regression method based on a set of covariates as predictors (IVEware for SAS, V.9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). To minimise random error, we imputed five datasets and then combined estimates from these datasets.29,30

RESULTS

The study cohort included 59 224 patients with gout and 238 805 matched non-gout individuals. The mean age at baseline was 65 years and approximately 71% of the population was men. Baseline characteristics of the cohorts are shown in table 1. Patients with gout tended to consume more alcohol, visit their GP more often and have more CV-metabolic comorbidities and more frequent use of CV medicines.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the presence of gout

| Variables | Gout (n=59 224) | No gout (n=238 805) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.3±12.2 | 65.3±12.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 41 950 (70.8%) | 169 749 (71.1%) |

| Female | 17 274 (29.2%) | 69 056 (28.9%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Mean±SD | 28.5±4.6 | 28.2±4.2 |

| <18.5 | 214 (0.4%) | 600 (0.3%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 12 476 (21.1%) | 51 898 (21.7%) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 27 235 (46.0%) | 115 671 (48.4%) |

| ≥30.0 | 19 299 (32.6%) | 70 636 (29.6%) |

| Socioeconomic deprivation index score | 2.6±1.3 | 2.6±1.3 |

| GP visits | 5.0±3.9 | 4.2±3.5 |

| Smoking | ||

| Current | 7784 (13.1%) | 38 808 (16.3%) |

| None/past | 50 690 (85.6%) | 196 566 (82.3%) |

| Unknown | 750 (1.3%) | 3431 (1.4%) |

| Alcohol | ||

| Current | 47 526 (80.2%) | 182 960 (76.6%) |

| None/past | 8800 (14.9%) | 41 788 (17.5%) |

| Unknown | 2898 (4.9%) | 14 057 (5.9%) |

| Hypertension | 33 337 (56.3%) | 101 435 (42.5%) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 23 966 (40.5%) | 80 280 (33.6%) |

| Stroke | 4976 (8.4%) | 15 782 (6.6%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 12 673 (21.4%) | 38 386 (16.1%) |

| Diabetes | 7341 (12.4%) | 31 531 (13.2%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) | 19 210 (32.4%) | 53 459 (22.4%) |

| Aspirin | 16 400 (27.7%) | 57 133 (23.9%) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) | 6861 (11.6%) | 18 411 (7.7%) |

| Beta-blockers | 17 957 (30.3%) | 47 212 (19.8%) |

| Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) | 13 347 (22.5%) | 47 447 (19.9%) |

| Diuretics | 26 606 (44.9%) | 59 256 (24.8%) |

| NSAIDs | 20 530 (34.7%) | 49 826 (20.9%) |

Data are represented as mean±SD or number (percentage).

Hyperlipidaemia: defined as a diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia or use of antihyperlipidaemics.

Socioeconomic Deprivation Index score was measured by the Townsend Deprivation Index, which was grouped into quintiles from 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived).

BMI, body mass index; GP, general practitioner; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

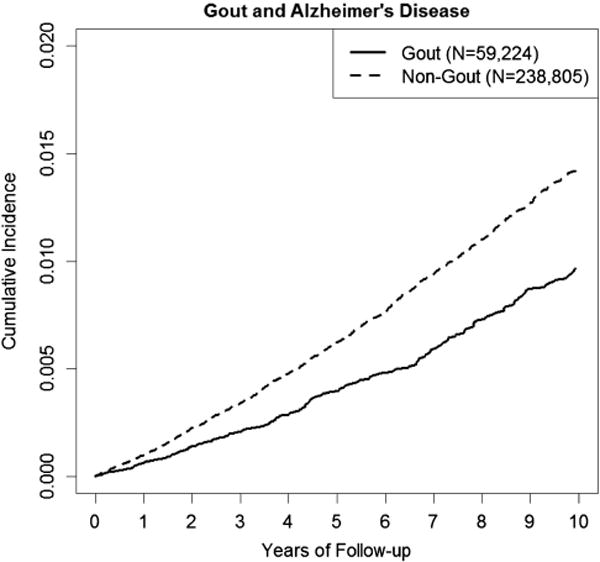

The cumulative incidence of AD according to the study cohort is depicted in figure 1; the incidence rates and HRs for the risk of AD are shown in table 2. Compared with individuals without gout, the age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched and BMI-matched HR of AD among patients with gout was 0.71 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.80). After adjusting for all covariates, the multivariate HR was 0.76 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.87). Stepwise regressions suggested that only diuretic use accounted for a difference between these HRs (table 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease according to the presence of gout.

Table 2.

Incidence rates and HRs for Alzheimer’s disease according to the presence of gout

| Gout (n=59 224) | No gout (n=238 805) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cases, n | 309 | 1942 |

| Follow-up time, person-years | 299 799 | 1 258 059 |

| Mean follow-up, years | 5.1 | 5.3 |

| Incidence rate (cases per 1000 person-years) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) |

| Age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched, BMI-matched HR (95% CI) | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.80) | 1.0 (reference) |

| +Continuous BMI-adjusted HR (95% CI) | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.80) | 1.0 (reference) |

| +Diuretics-adjusted HR (95% CI) | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.87) | 1.0 (reference) |

| +Other CV drugs (95% CI) | 0.76 (0.67 to 0.87) | 1.0 (reference) |

| +CV comorbidities (95% CI) | 0.76 (0.67 to 0.88) | 1.0 (reference) |

| +GPs visits, smoking, alcohol and SDI (95% CI) | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.87) | 1.0 (reference) |

BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; GP, general practitioner; SDI, social–economic deprivation index.

The inverse association persisted among subgroups by sex, age group (<75 and ≥75 years), social deprivation index and history of CV disease (table 3). The protective effect of gout on AD was similar among those with and without CV disease (ie, ischaemic heart disease or stroke) (HRs, 0.65 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.92) vs 0.78 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.93)) (p for heterogeneity, 0.12) (table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence rates and HRs for associations between gout and Alzheimer’s disease according to subgroups

| Gout status | N | Cases | Follow-up time (person-years) | Mean follow-up (years) | Incidence rate (cases per 1000 person-years) | Age, sex, entry-time, and BMI-matched HR (95% CI)* | + GPs visits, continuous BMI, smoking, and alcohol adjusted HR (95% CI) | + comorbidity and CVD drug adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||||||

| Yes | 59 224 | 309 | 299 799.1 | 5.1 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.80) | 0.70 (0.62 to 0.80) | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.87) |

| No | 238 805 | 1942 | 1 258 058.9 | 5.3 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Female | ||||||||

| Yes | 17 274 | 122 | 83 951.9 | 4.9 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.7) | 0.65 (0.53 to 0.80) | 0.68 (0.55 to 0.83) | 0.72 (0.58 to 0.90) |

| No | 69 056 | 856 | 355 988.2 | 5.2 | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.6) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Male | ||||||||

| Yes | 41 950 | 187 | 215 847.3 | 5.1 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.87) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.95) |

| No | 169 749 | 1086 | 902 070.8 | 5.3 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| <75 years | ||||||||

| Yes | 44 407 | 141 | 244 754.2 | 5.5 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.94) | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.93) | 0.79 (0.65 to 0.97) |

| No | 180 066 | 850 | 1 025 029.2 | 5.7 | 0.8 (0.8 to 0.9) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 75–90 years | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 817 | 168 | 55 045.0 | 3.7 | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.6) | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.78) | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.78) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.87) |

| No | 58 739 | 1092 | 233 029.7 | 4.0 | 4.7 (4.4 to 5.0) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| High socioeconomic depravity (SDI>2) | ||||||||

| Yes | 23 277 | 121 | 117 926.0 | 5.1 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.64 (0.50 to 0.83) | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.87) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.92) |

| No | 92 583 | 810 | 489 553.6 | 5.3 | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Low socioeconomic depravity (SDI≤2) | ||||||||

| Yes | 35 947 | 188 | 181 873.2 | 5.1 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.91) | 0.78 (0.61 to 0.99) |

| No | 146 222 | 1132 | 768 505.3 | 5.3 | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 33 337 | 192 | 159 670.2 | 4.8 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.88) | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.88) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.91) |

| No | 101 435 | 927 | 487 592.5 | 4.8 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| No hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 25 887 | 117 | 140 128.9 | 5.4 | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.76 (0.59 to 0.98) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.97) | 0.78 (0.60 to 1.01) |

| No | 137 370 | 1015 | 770 466.5 | 5.6 | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | ||||||||

| Yes | 23 966 | 121 | 101 617.9 | 4.2 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 0.66 (0.51 to 0.86) | 0.65 (0.50 to 0.84) | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.91) |

| No | 80 280 | 623 | 345 379.8 | 4.3 | 1.8 (1.7 to 2.0) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| No hyperlipidaemia | ||||||||

| Yes | 35 258 | 188 | 198 181.3 | 5.6 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.84) | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.84) | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.91) |

| No | 158 525 | 1319 | 912 679.1 | 5.8 | 1.4 (1.4 to 1.5) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| CVD | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 691 | 87 | 70 580.6 | 4.5 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 0.56 (0.40 to 0.78) | 0.54 (0.39 to 0.75) | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.92) |

| No | 49 189 | 508 | 236 346.2 | 4.8 | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| No CVD | ||||||||

| Yes | 43 533 | 222 | 229 218.5 | 5.3 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.78 (0.65 to 0.93) |

| No | 189 616 | 1434 | 1 021 712.8 | 5.4 | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

Adjusted for the covariates in table 1, except for the subgroup variables.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GP, general practitioner; SDI, social–economic deprivation index.

In our sensitivity analysis, restricting gout cases to those receiving anti-gout treatment (n=31 799) showed that both the main and subgroup results persisted (see online supplementary table S2). Furthermore, in our comparison analysis of OA as a negative control exposure, we found no association between OA and the risk of incident AD (age-matched, sex-matched, entry-time-matched and BMI-matched HR=1.05 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.10) and multivariate HR=1.02 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.08)).

DISCUSSION

In this large general practice cohort representative of the UK population, we found a 24% lower risk of AD among individuals with a history of gout, after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors, prior CV-metabolic conditions and use of CV drugs. The inverse association was evident among subgroups stratified by sex, age group, social deprivation index and history of CV disease. In contrast, we found no such association with OA. These findings provide the first general population-based evidence that gout is inversely associated with the risk of developing AD, thus supporting the purported potential neuroprotective role of uric acid.

The potential biological mechanisms behind the observed inverse association are speculative. Uric acid has previously been shown to have antioxidative properties;31 specifically, it is an effective scavenger of peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radicals (thus reducing oxidative stress)32 and it has metal chelator properties in vitro.31,33 Thus, the possible neuroprotective effects of uric acid may be due to suppression of oxyradical accumulation and preservation of mitochondrial function,34 thus inhibiting the cytotoxic activity of lactoperoxidase35 and repairing free-radical-induced DNA damage.36 In animal models of PD, uric acid has shown neuroprotective effects against oxidative stress-induced dopaminergic neuron death,37–39 and similar neuroprotective effects have been observed in animal models of other neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury.40

Our study expands on a prospective analysis based on the Rotterdam study that showed an inverse association between prior SUA levels (ie, the causal precursor of gout) and the risk of any dementia.13 As both vascular dementia and Alzheimer dementia were included in the Rotterdam study, the neuroprotective effect of uric acid may have been masked by the hyperuricaemia-associated increased CV risk (eg, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke).37–39 The current study investigated the specific risk of AD as an endpoint and found a consistently inverse association with the risk of AD. Further, considering AD (as opposed to vascular dementia) would be more likely to be diagnosed among individuals without CV risk factors or comorbidities, our subgroup analyses according to CV risk factors suggest that the inverse relation persists among individuals regardless of known CV comorbidities. Overall, these findings support the proposed hypothesis that supplementary use of the metabolic precursor to uric acid, like inosine or hypoxanthine, could prevent and attenuate the progression of AD.41

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First, our study was based on a large electronic medical record (EMR) database representative of the general population; therefore, our findings are likely to be more generalisable. Because the definitions of gout and AD were based on doctors’ diagnoses, a certain level of misclassification is inevitable. A diagnosis of gout could often have been recorded based on the suggestive clinical presentation of gout without documentation of monosodium urate crystals. However, any non-differential misclassification of these diagnoses would have biased the study results towards the null and would not likely explain the significant associations observed in this study. Furthermore, when we used doctors’ diagnoses of gout combined with anti-gout drug use (which has previously shown a validity of 90%)21,22 as our case definition, our results tended to be even stronger. While the aforementioned Rotterdam study data13 suggest that high SUA levels (as opposed to anti-gout medication use) are likely to explain the observed inverse association, these issues deserve further investigation. Finally, our negative control exposure analysis using OA supports that the observed inverse association is unlikely to be related to common features of arthritis such as chronic pain, NSAID use or methodological artefact, and rather is specific to gout, which is caused by hyperuricaemia.

In conclusion, our findings provide the first population-based evidence for the potential protective effect of gout on the risk of AD and support the purported neuroprotective role of uric acid. If confirmed by future studies, a therapeutic investigation that has been employed to prevent progression of PD may be warranted for this relatively common and devastating condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported in part by grants from NIAMS (P60AR047785, R01AR056291 and R01AR065944).

Footnotes

Handling editor Tore K Kvien

Contributors NL, YZ and HKC: design, analysis and drafting of the manuscript. MD: data extraction and drafting of the manuscript. MAH, TN, SKR and AA: analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

Competing interests HKC has served on advisory boards for Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals.

Ethics approval The study research protocol was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board and the Multicenter Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007–2008. Am J Med. 2012;125:679–687 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbott RD, Brand FN, Kannel WB, et al. Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:237–42. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan E, Baker JF, Furst DE, et al. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2688–96. doi: 10.1002/art.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, et al. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1104–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi HK, Curhan G. Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2007;116:894–900. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller NJ, Rice-Evans C, Davies MJ, et al. A novel method for measuring antioxidant capacity and its application to monitoring the antioxidant status in premature neonates. Clin Sci (Lond) 1993;84:407–12. doi: 10.1042/cs0840407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisskopf MG, O’Reilly E, Chen H, et al. Plasma urate and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:561–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarzschild MA, Schwid SR, Marek K, et al. Serum urate as a predictor of clinical and radiographic progression in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:716–23. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.6.nct70003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ascherio A, LeWitt PA, Xu K, et al. Urate as a predictor of the rate of clinical decline in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1460–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A, Beal MF, et al. Inosine to increase serum and cerebrospinal fluid urate in Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:141–50. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:3223–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunomura A, Castellani RJ, Zhu X, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:631–41. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000228136.58062.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Euser SM, Hofman A, Westendorp RG, et al. Serum uric acid and cognitive function and dementia. Brain. 2009;132:377–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourke A, Dattani H, Robinson M. Feasibility study and methodology to create a quality-evaluated database of primary care data. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12:171–7. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i3.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National_Health_Service(NHS) Read Codes—NHS Connecting for Health [Google Scholar]

- 16.FirstDataBank. Drug Databases—Multilex Drug Data File [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:922–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafson DR, Backman K, Joas E, et al. 37 years of body mass index and dementia: observations from the prospective population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:163–71. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolppanen AM, Ngandu T, Kareholt I, et al. Midlife and late-life body mass index and late-life dementia: results from a prospective population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:201–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HK, Soriano LC, Zhang Y, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2012;344:d8190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso A, Rodriguez LA, Logroscino G, et al. Gout and risk of Parkinson disease: a prospective study. Neurology. 2007;69:1696–700. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279518.10072.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier CR, Jick H. Omeprazole, other antiulcer drugs and newly diagnosed gout. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:175–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn N, Mullee M, Perry VH, et al. Association between dementia and infectious disease: evidence from a case-control study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:91–4. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000165511.52746.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imfeld P, Brauchli Pernus YB, Jick SS, et al. Epidemiology, co-morbidities, and medication use of patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia in the UK. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35:565–73. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:111–28. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/cqiu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris R, Carstairs V. Which deprivation? A comparison of selected deprivation indexes. J Public Health Med. 1991;13:318–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. Health and deprivation: inequality and the North. London; New York: Croom Helm; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, et al. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Zhu Y, et al. Diabetes incidence in psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, et al. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6858–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rundles RW, Wyngaarden JB. Drugs and uric acid. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1969;9:345–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.09.040169.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies KJ, Sevanian A, Muakkassah-Kelly SF, et al. Uric acid-iron ion complexes. A new aspect of the antioxidant functions of uric acid. Biochem J. 1986;235:747–54. doi: 10.1042/bj2350747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu ZF, Bruce-Keller AJ, Goodman Y, et al. Uric acid protects neurons against excitotoxic and metabolic insults in cell culture, and against focal ischemic brain injury in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:613–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980901)53:5<613::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Everse J, Coates PW. The cytotoxic activity of lactoperoxidase: enhancement and inhibition by neuroactive compounds. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:839–49. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson RF, Harris TA. Dopamine and uric acid act as antioxidants in the repair of DNA radicals: implications in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:1131–6. doi: 10.1080/10715760310001604134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cipriani S, Desjardins CA, Burdett TC, et al. Urate and its transgenic depletion modulate neuronal vulnerability in a cellular model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong L, Zhang QL, Zhang N, et al. Neuroprotection by urate on 6-OHDA-lesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease: linking to Akt/GSK3beta signaling pathway. J Neurochem. 2012;123:876–85. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X, Burdett TC, Desjardins CA, et al. Disrupted and transgenic urate oxidase alter urate and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217296110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooper DC, Bagasra O, Marini JC, et al. Prevention of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by targeting nitric oxide and peroxynitrite: implications for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waugh WH. Inhibition of iron-catalyzed oxidations by attainable uric acid and ascorbic acid levels: therapeutic implications for Alzheimer’s disease and late cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2008;54:238–43. doi: 10.1159/000122618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.