Abstract

The neurotensin receptor NTSR1 binds the peptide agonist neurotensin (NTS) and signals preferentially via the Gq protein. Recently, Grisshammer and co-workers reported the crystal structure of a thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5 with NTS bound. Understanding how the mutations thermostabilize the structure would allow efficient design of thermostable mutant GPCRs for protein purification, and subsequent biophysical studies. Using microsecond scale molecular dynamics simulations (4 μs) of the thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5 and wild type NTSR1, we have elucidated the structural and energetic factors that affect the thermostability and dynamics of NTSR1. The thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5 is found to be less flexible and less dynamic than the wild type NTSR1. The point mutations confer thermostability by improving the interhelical hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic packing, and receptor interactions with the lipid bilayer, especially in the intracellular regions. During MD, NTSR1-GW5 becomes more hydrated compared to wild type NTSR1, with tight hydrogen bonded water clusters within the transmembrane core of the receptor, thus providing evidence that water plays an important role in improving helical packing in the thermostable mutant. Our studies provide valuable insights into the stability and functioning of NTSR1 that will be useful in future design of thermostable mutants of other peptide GPCRs.

Introduction

Neurotensin (NTS) is a 13 amino acid peptide found in the central nervous system and in peripheral tissues,1 and plays a crucial role in a wide range of biological activities such as the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, antinoiception, hypothermia, and lung cancer progression.2−5 Neurotensin activates neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1) which is one of the three neurotensin receptors known to date.6 NTSR1 is a class A, peptide-activated GPCR sharing a seven transmembrane (TM) helical structural motif conserved in class A GPCRs.7 GPCRs are dynamic proteins sampling several functional conformations ranging from the “inactive state” to the “fully active” state.8,9 Analysis of the crystal structures of the inactive state10 and the active state of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) with the G protein bound8 shows that the intracellular portions of TM5 and TM6 move significantly with respect to TM3 upon activation when bound to both the agonist and the G protein. This outward movement of TM6 away from TM3 is a characteristic conformational change observed during activation in class A GPCRs. The change in the distance between TM3 and TM6 upon activation11,12 is measured as the distance between the Cα atoms of R3.50 and L6.30. Here we have used the Ballesteros–Weinstein amino acid numbering system for class A GPCRs.13 The first number in the superscript is the TM helix in which the amino acid is located, and the second number is the position of this residue with respect to the most conserved residue in that helix which is numbered 50. This distance in various crystal structures of the active and inactive states of class A GPCRs is given in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. However, this is only one of several conformational changes that occur during activation.11

Another structural feature observed in the crystal structure of the fully active state of class A GPCRs is the tight packing of the hydrophobic residues P5.50 and F6.44 in the active state compared to their respective inactive states.14 This distance in various GPCR crystal structures is given in Table S2 of the Supporting Information. A third feature of the active state crystal structures is the inward movement of the intracellular end of TM7 that brings this region of TM7 closer to TM3. In the active state crystal structures known so far, the inter-residue distance between R3.50 and Y7.53 decreases upon activation, as shown in Table S3 (Supporting Information). Hildebrand and co-workers recently15 calculated the distance between the center of mass (COM) of five residues in the intracellular region of TM2 to that of TM6 to measure the outward movement of the intracellular regions of TM6. Table S4 (Supporting Information) shows this distance in various active and inactive state crystal structures.

Recently, the crystal structures of thermostable mutants of NTSR1 with neurotensin bound have been reported.16,17 The thermostable mutant of NTSR1, known as GW5 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 4GRV],16 contains six thermostabilizing mutations: A86L1.54, E166A3.49, G215AECL2, L310A6.37, F358A7.42, and V360A7.44. The mutation in extracellular loop 2 is designated as ECL2. We denote the thermostable mutant as NTSR1-GW5 and the wild type NTSR1 as wt-NTSR1. We denote the crystal structure of NTSR1-GW5 with its PDB code 4GRV, as NTSR1-4GRV. This distinguishes it from NTSR1-GW5, which is used later in the paper for describing the conformations from the molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on the NTSR1-GW5 mutant.

The NTSR1-4GRV crystal structure with NTS bound shows outward movement of TM6 with respect to TM3 that is similar in extent to that observed in the crystal structure of ligand free opsin.18 NTSR1-4GRV also shows an interhelical hydrogen bond between R1673.50 and N2575.58, a feature also observed in ligand free rhodopsin (opsin*)18 and the active state of rhodopsin.19 Since the outward movement of TM6 in the NTSR1-4GRV structure is not as predominant as in the fully active state of the β2AR, we call the NTSR1-4GRV structure an “active-like” state, because of the many conserved features between the active states of rhodopsin and β2AR and NTSR1-4GRV. It is unlikely that NTSR1-4GRV represents a fully active structure as observed on G protein binding,8,16 because it would be expected that the intracellular end of TM6 should move further out when the G-protein couples to NTSR1.

Using the NTSR1-4GRV crystal structure, White et al.16 rationalized the role of two thermostabilizing mutations (E166A3.49 and L310A6.37), whereas there was no obvious structural reason for the thermostabilizing effect of the other four mutations (A86L1.54, G215AECL2, F358A7.42, and V360A7.44). None of the six mutant residues are located in the ligand binding site (Figure S1, Supporting Information). The E166A3.49 mutation prevents the intrahelical salt bridge with R1673.50, which is a feature of the inactive state, thus facilitating the movement of TM6 toward the active-like state by allowing R1673.50 to interact with N2575.58. Decreasing the size of the side chain by the mutation of L310A6.37 promotes the hydrogen bond between R1673.50 and N2575.58. The NTSR1 single mutants A86L1.54 and F358A7.42 showed higher measured thermostabilities both in the presence and absence of the agonist NTS compared to other mutations.20 Thus, the information gleaned from the crystal structure is limited and does not explain the thermostability of all the mutations. Since the single snapshot of the crystal structure is inadequate in providing understanding of the receptor dynamics, we have used microsecond molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to address two outstanding questions: (1) How do the mutations stabilize the receptor in the active-like state? (2) What are the differences in the dynamics of the active-like state of NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wt-NTSR1?

We have performed a total of 4 μs of MD simulations using the Anton specialized computers21 for the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5, starting from the NTSR1-4GRV crystal structure of the thermostabilized rat NTSR1 bound to the carboxy terminal portion (NTS8–13) of the endogenous peptide agonist NTS. Finally, the NTSR1-4GRV structure does not show the amphipathic helix 8 at the carboxy terminus of the receptor. Instead, the intracellular region of TM7 was elongated by three helical turns beyond the well-conserved NPxxY motif. Subsequent crystal structures of NTSR1 thermostable mutants showed the presence of helix 8. To examine the stability of helix 8 in the NTSR1-4GRV structure, we used an additional 2 μs of MD simulations to examine the dynamic behavior and stability of helix 8 by homology modeling. The MD simulations provide insights into the dynamics of NTSR1-GW5 and how the mutations specifically stabilize the active-like state compared to the wild type receptor.

Methods

Preparation of the Receptor Structures for MD Simulations

The MD simulations for the agonist NTS bound mutant NTSR1-GW5 were started from its crystal structure (PDB code 4GRV).16 The initial conformation of the wild type receptor was generated by mutating the residues in the crystal structure of NTSR1-4GRV back to the wild type sequence using Maestro v9.2 (Schrödinger, Inc.). We omitted T4 lysozyme from all the simulations, and did not model the unresolved 31-residue stretch in the intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) between TM5 and TM6 in the crystal structure (residues H269–R299), since the loop addition programs are not reliable for this long stretch of loop residues. The residues in the amino and carboxy termini that were either deleted from the crystallized construct or not resolved in the crystal structure were also omitted from the simulations. The four disordered residues in the intracellular loop 1 (K93–Q96) were added by homology modeling (Modeler v9.7).22,23 All the MD simulations were done in the presence of NTS8–13. All NTSR1 systems were embedded in a hydrated palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidyl-choline (POPC) bilayer in all the MD simulations. All the atoms (including those in lipids and water) were represented explicitly. Hydrogen atoms were added to the crystal structures using Maestro (Schrödinger, LLC), and N and C termini were capped with neutral groups (acetyl and methylamide, respectively). The protein structures were inserted into an equilibrated POPC bilayer solvated with 0.15 M NaCl. All four systems based on the NTSR1 crystal structure initially measured about 80 Å × 80 Å × 85 Å (0.54 × 106 Å3) and contained 173 lipid molecules, 2800 water molecules, 40 chloride (Cl–) ions, and 28 sodium ions (Na+), with a total of approximately 58 900 atoms.

Molecular Dynamics

We used the MD simulation package installed in the Anton specialized computers.21 For all the MD simulations, we used the CHARMM27 parameter set24 with CMAP terms25 and the TIP3P water model.26 A modified CHARMM22 lipid force field27 was used. After energy minimization and heating the system to 310 K, all simulations consisted of a 50 ns equilibration run followed by a 2 μs production run. All the systems were equilibrated in the NPT ensemble (310 K at 1 bar of pressure), with initial velocities sampled from the Boltzmann distribution and with 5 kcal/mol/Å2 harmonic position restraints applied to all non-hydrogen atoms of the protein and peptide ligand. The harmonic restraint was linearly tapered over the 50 ns equilibration period. Production simulations were initiated from the final snapshot of the equilibration run. Both equilibration and production runs were performed on Anton, the special-purpose supercomputer that significantly accelerates standard MD simulations.21,28 The SHAKE algorithm29 was used to constrain all bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms, allowing 2 fs time steps to be used. For the analysis, the long-range electrostatics were computed every 6 fs. The cutoff distance of 13.5 Å was used for nonbonded interactions, and the k-space Gaussian split Ewald method30 was used for long-range van der Waals interactions. The simulation details are summarized in Table S5 (Supporting Information).

RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) Calculation

RMS fluctuations for NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 were calculated using the g_rmsf program in the GROMACS v4.6 molecular dynamics package.31 These Cα RMSFs have been directly compared to the crystallographic temperature factor (B) using the conversion factor RMSF = (3B/8π2)1/2.

Protein Potential Energy Calculation

Protein structures from Anton trajectories for NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 were prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard protocol available in the Schrödinger suite (Maestro9.2 software package from Schrödinger, LLC). The NTS8–13 peptide, water molecules, and POPC bilayer lipids were deleted for protein enthalpy calculation. Each single-point enthalpy was calculated by the CHARMM27 force field with bond orders of protein reassigned.

Homology Modeling

During the course of this work, more crystal structures of other thermostable NTSR1 mutants bound to NTS were published.17 Unlike the NTSR1-4GRV structure, these crystal structures showed helix 8 (H8). To examine the stability of helix 8 for the GW5 mutant, we added the helix 8 structure from the crystal structures of Egloff et al.,17 on to NTSR1-4GRV and to the corresponding wild type derived from the NTSR1-4GRV structure. The homology models were generated using the structure of NTSR1-4GRV (PDB code 4GRV) until P3667.50, followed by the crystal structure of 4BUO(17) to the end of the carboxy terminus of amphipathic helix 8. MODELER v9.722,23 was used to build a homology model of helix 8 with the 4BUO as the template structure for helix 8. The resulting homology models of the NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 with helix 8 (denoted as NTSR1-GW5-H8 and wt-NTSR1-H8, respectively) were optimized to reduce the side chain steric clashes. Later on, the potential energy of the entire receptor was minimized and equilibrated using the GROMACS v4.6 package with the CHARMM22 lipid force field with TIP3P water molecules. These two homology models were equilibrated by performing 5 ns of MD at 310 K using the NPT ensemble with harmonic restraint followed by 1000 ns of NPT production run.

Principal Component Analysis

To understand the similarities and differences in the protein global motion in NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1, we performed the principal component analysis (PCA). The g_anaeig and g_covar programs in GROMACS v4.631 were employed to calculate covariance matrix elements in PCA. In our analysis, only the main chain atoms of six TM helices (TM2–TM7) were considered and TM1 was omitted for the PCA due to the missing amino terminus that would control its movement.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

For understanding the effect of point mutations on the effects of lipid packing (interaction of the protein and the POPC lipid bilayer), we have calculated the SASA for those residues that are within 5 Å of the POPC molecules in wt-NTSR1 and the NTSR1-GW5 mutant. We used the VMD Tcl command “measure sasa 1.4 $all −restrict $selection”, where $all is an atom selection for the whole protein and $selection is the protein atoms that are within 5 Å of the lipid molecules.

Results

Comparison of Receptor Flexibility of wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5

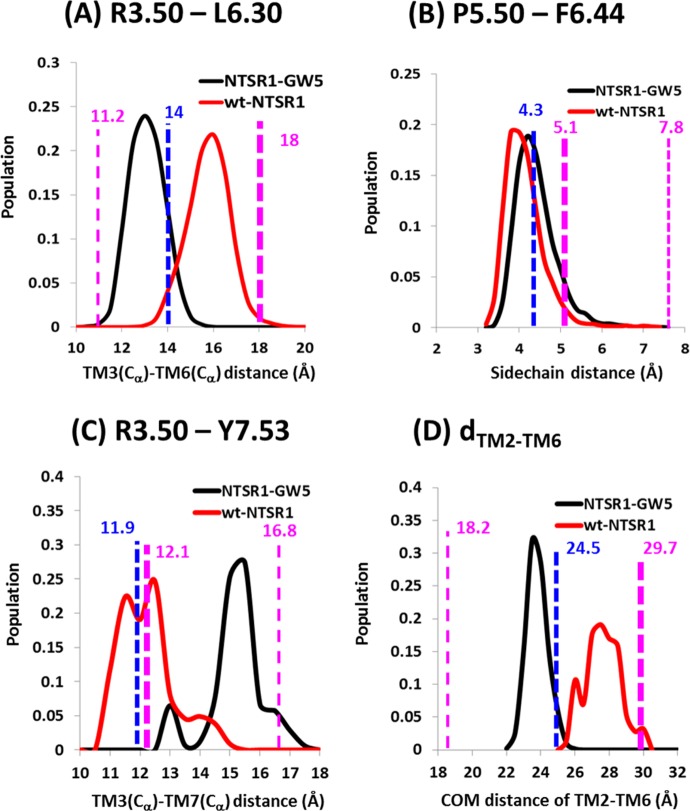

We have compared the flexibility of the wt-NTSR1 to the thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5. Figure 1 shows the comparison of the root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSFs) in coordinates from the average structure from MD simulations for each residue for the two systems (wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5) in addition to that computed from the X-ray B-factor. The loop regions showed large fluctuations irrespective of the simulation system. Lower flexibility was observed for the transmembrane regions, and these were in agreement with the B-factors of the crystal structure. The NTSR1-GW5 shows less receptor flexibility compared to the wt-NTSR1, especially in the extra- and intracellular loops.

Figure 1.

RMS fluctuation for the Cα atoms over the entire 2 μs simulation for NTSR1-GW5 mutant (black) and its wild type (red), and then compared with the RMSF of the 4GRV crystal structure (blue) (conversion from B-factor to RMSF). The transmembrane regions are marked in the figure.

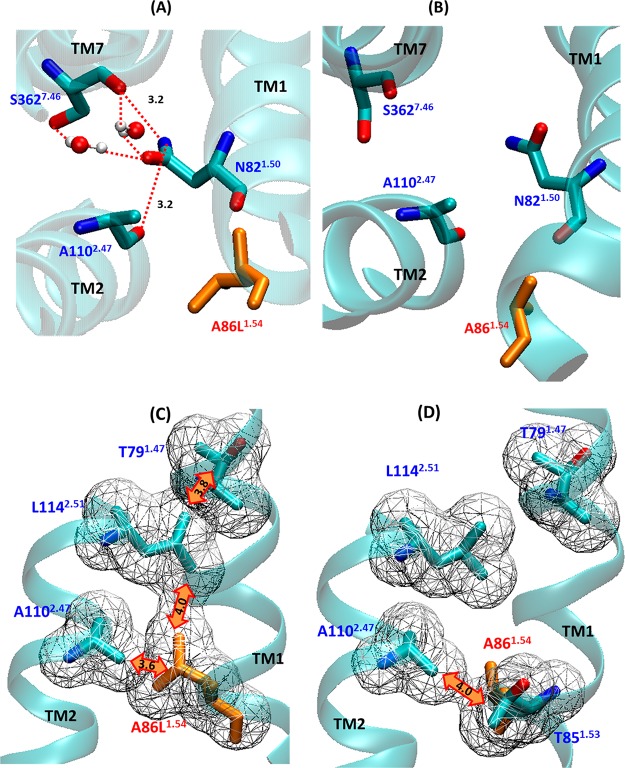

Comparison of the Active-Like Features of the wt-NTSR1 to NTSR1-GW5

We have analyzed four different inter-residue distances that show a change upon activation in class A GPCRs, described in the Introduction section, to understand the differences in the dynamics of the wt-NTSR1 compared to the mutant NTSR1-GW5 (Figure 2). Our MD simulations show that the distance between the Cα atoms of the residues R1673.50 and L3036.30 (Cα3.50–Cα6.30) in NTSR1-GW5 stays between the corresponding distance in the inactive state of β2AR and in the active-like state of the NTSR1-4GRV crystal structure. The R1673.50 and L3036.30 distance in the wt-NTSR1 is between the crystal structure of NTSR1-4GRV and the fully active state of β2AR, as shown in Figure 2A. We also calculated the most populated (observed in many conformations in the MD ensemble) distance between the center of mass of the last three helical turns of TM3 and TM6 that supports the same observation (shown in Figure S2, Supporting Information). Figure 2B shows the receptor population density variation with the inter-residue distance between P2495.50 and F3176.44 in both the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5. There is little difference in the dynamics between the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5 in this inter-residue distance. Figure 2C shows the population density variation with the inter-residue distance R3.50 and Y7.53. The wt-NTSR1 shows a lower spread in this distance, keeping it close to the crystal structure (11.9 Å), a more active-state-like behavior compared to the NTSR1-GW5. The increase in the distance between R3.50 and Y7.53 comes from rotation of the side chain of Y7.53 in the dynamics of NTSR1-GW5 and infiltration of three water molecules (with 40% of the snapshots having these waters). Such a rotation is not seen in the wt-NTSR1, which keeps the TM3 and TM7 distance intact. Figure 2D shows the distance between the center of mass of five residues in the intracellular part of TM2 and TM6. The wt-NTSR1 opens up more like G protein bound β2AR, while NTSR1-GW5 does not. Summarizing these inter-residue distance analyses shows that the dynamics of wt-NTSR1 are closer to the fully active state of the β2AR conformation compared to the dynamics of NTSR1-GW5. The wt-NTSR1 shows more of the active-state-like structural features than the NTSR1-GW5.

Figure 2.

Variation of inter-residue distances of active-like wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5. (A) The population distribution density of the Cα–Cα distance of R1673.50–L3036.30 for the NTSR1-GW5 (black) and wt-NTSR1 (red). (B) The receptor population density variation with the inter-residue side chain distance between P2495.50 and F3176.44 in the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5. (C) The population density variation with the inter-residue distance R1673.50–Y3697.53 observed in the MD simulation. (D) The observed population density of the COM (center-of-mass) distance using five residues in the intracellular TM2 and TM6 (dTM2-TM6) for NTSR1-GW5 (black) and wt-NTSR1 (red). The inter-residue distance in the crystal structure, NTSR1-4GRV, is shown as a blue dashed line. The same inter-residue distances in the crystal structures of the fully active (PDB code 3SN6) and inactive (PDB code 2RH1) states of β2AR are shown in bold and thin magenta dashed lines, respectively.

Differences in the Intracellular Movement of TM5 and TM6 in the Wild Type and the GW5 Mutant

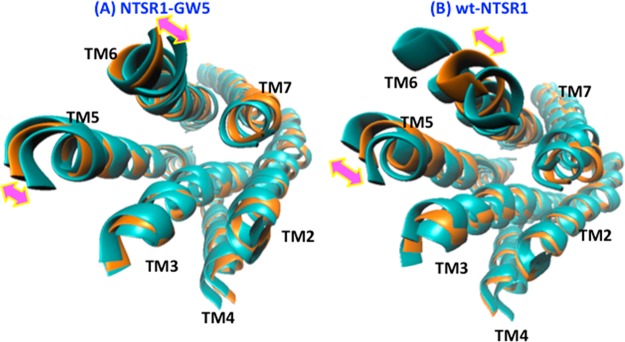

We used principal component analysis (PCA) to analyze the global motion of the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5 receptors during the MD simulations. We performed PCA of the MD trajectories of the main chain atoms in the TM helices of NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1, and visualized the movement of the first two principal components that show the direction and magnitude of major movements in the TM region of the receptors (shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Two principal components represented by the double arrows showing the dominant motion in the NTSR1-GW5 (A) and wt-NTSR1 (B) simulations. Shown in this figure is the intracellular view of the TM bundle. The orange-colored structures are the average structures for each system generated from covariance matrix and from filtering the trajectories, and the cyan-colored structures are the representative structures of the most populated cluster in the ensembles.

The principal component 1 (PC1) is dominated by the outward movement of the intracellular part of TM5 and TM6. As shown in Figure 3, the NTSR1-GW5 shows less movement in the intracellular regions of TM5 and TM6 compared to wt-NTSR1. Thus, the wt-NTSR1, which, in contrast to NTSR1-GW5, activates the G protein, shows an outward movement of TM5 and TM6 with respect to TM3. Such a movement also leads to activation, and we had observed this type of movement in our previous study of the dynamics of ligand free β2AR.32 PCA shows that the flexibility of the wt-NTSR1 receptor is higher, while the NTSR1-GW5 remains rather inflexible. Taking the results of the PCA combined with the analysis on the changes in inter-residue distances that characterize activation processes, we summarize that the dynamic behavior of wild type NTSR1 shows more active-like characteristics compared to NTSR1-GW5. This observation may explain why the NTSR1-GW5 mutant does not catalyze the GDP–GTP exchange at Gαq, as efficiently as the wt-NTSR1, an experimentally observed behavior of the two receptors.16

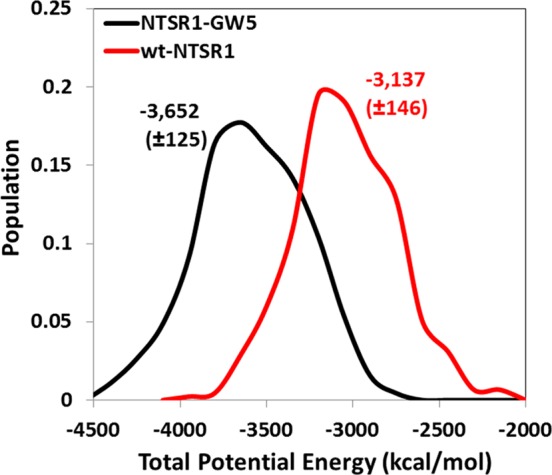

Enthalpic Stabilization of Thermostable Mutant NTSR1-GW5 from Increased Interhelical Packing Interactions

To understand the energetic contribution of the mutations in the thermostabilization of NTSR1, we compared the enthalpy of the wild type receptor and the NTSR1-GW5 mutant. Figure 4 shows the population density distribution of the enthalpy of various conformations in the MD ensemble calculated over the MD trajectories for the thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5 (black) and the wt-NTSR1 (red) receptors. The enthalpy is the total potential energy of the system (Etot), and provides information on the stability of the NTS8–13–NTSR1 complex and interaction energy between protein/POPC and protein/waters. The values of enthalpy at the peaks are shown in Figure 4. The difference in the energies between the most populated conformations of NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 shows that the thermostable mutant is more stable by 515 kcal/mol compared to the wt-NTSR1. The components of the potential energy such as the nonbonded energy of the receptor, receptor–ligand interaction energy, receptor–lipid (POPC) interaction energy, and receptor–water interaction energy are all shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Information). These results show that the significant contribution to the stability of NTSR1-GW5 comes from the receptor energy and the receptor–POPC interaction energy (Figure S3A and B, Supporting Information). The protein energy of NTSR1-GW5 is lower due to the improvement in the interhelical packing interactions, as discussed in the section below. The annular lipids around the NTSR1-GW5 show better packing than the lipids around wt-NTSR1 (Figure S3C and D, Supporting Information). This is reflected by the more compact radius of gyration calculated for the NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wt-NTSR1 (Figure S3C, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Population density distribution of the conformations in the MD ensemble with the total potential energy for the NTSR1-GW5 (black) and wt-NTSR1 receptors (red).

We have further analyzed the cause for the more favorable receptor–POPC interaction energy in the mutant NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wt-NTSR1. Figure S4A (Supporting Information) shows the nonbonded interaction energy between the lipid bilayer and the residues that are within 7 Å of the mutation positions in the receptor. As seen in this figure, 80% of the favorable interaction energy between the receptor and POPC in NTSR1-GW5 comes from the lipid interaction with the residues that are in the vicinity of the mutations. Figure S4B (Supporting Information) shows the breakdown of this interaction energy for each point mutation in NTSR1-GW5 (wt-NTSR1 shown in red and NTSR1-GW5 in black). Figure S4C (Supporting Information) shows the difference in the Coulombic and van der Waals components of the lipid protein interaction energies between the NTSR1-GW5 and the wt-NTSR1, for the residues in the vicinity of each mutation position. It is seen that the mutations A86L1.54, E166A3.49, and L310A6.37 that are located in the intracellular regions of transmembrane helices contribute significantly to the stronger protein–lipid interaction in the NTSR1-GW5 mutant compared to the wild type. We also calculated the solvent accessible surface area of the protein regions that are exposed to the lipid bilayer (calculated as described in the Methods section) in the NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1, shown in Figure S4D (Supporting Information). The protein surface area exposed to the lipid bilayer is higher in the NTSR1-GW5 than in the wild type NTSR1 that leads to better interaction energy between the NTSR1-GW5 and the lipid bilayer.

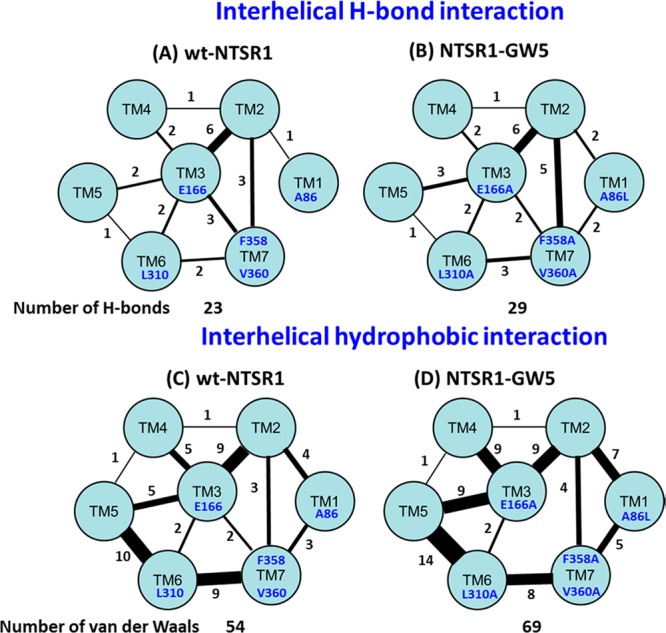

To understand the structural basis of the enthalpic stabilization of the NTSR1-GW5 mutant, we calculated the number of interhelical hydrogen bonds and van der Waals (vdW) packing interactions averaged over the trajectories for each system. Changes in the interhelical interactions play an important role in the packing33,34 of the TM core in the membrane protein structures. Figure 5 shows the analysis of the differences in the number of interhelical hydrogen bonds and vdW interactions in the 2 μs of MD simulations on NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1. Details of the specific interhelical hydrogen bond and vdW interactions observed are listed for these systems in Tables S6 and S7 (Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

Total number of interhelical interactions between various pairs of helices, calculated for the two NTSR1 systems. Parts A and B show the interhelical hydrogen bonds between each transmembrane helix in the wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5, while parts C and D show the interhelical vdW interactions. The number on each line is the total number of each type of interhelical interactions between pairs of TM helices.

As seen in Figure 5, NTSR1-GW5 has a higher number of pairwise interhelical hydrogen bonds and vdW interactions than those of the wt-NTSR1. The difference in the number of interhelical vdW interactions is much higher than that in the interhelical hydrogen bond interactions, since the six point mutations in NTSR1-GW5 lead to repacking of the side chains in the neighborhood of the mutations as explained in the next section. TM3 shows stronger vdW interactions with TM2, TM4, TM5, TM6, and TM7 in NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wild type receptor. This makes NTSR1-GW5 enthalpically more stable than the wild type receptor.

Effect of Individual Point Mutations on the Thermostability of NTSR1-GW5

The five mutations in NTSR1-GW5, A86L1.54, E166A3.49, L310A6.37, F358A7.42, and V360A7.44, are located in TM1, TM3, TM6, and TM7, respectively, whereas the sixth mutation G215AECL2 is located on the extracellular loop 2. The mutations A86L1.54, E166A3.49, and L310A6.37 are located in the intracellular parts of TM1, TM3, and TM6, respectively, while the mutations F358A7.42 and V360A7.44 are positioned in the middle of TM7. Out of these six mutations, the single mutants A86L1.54 and F358A7.42 show higher thermostability than any other single mutation;20,35 however, the structural basis of this thermostability is not obvious from the crystal structure. To rationalize the stability of each mutation, we calculated the difference in the interhelical hydrogen bonds as well as vdW interactions between NTSR1-GW5 and the wild type receptor in the neighborhood of the mutation positions 86, 166, 310, 358, and 360.

A86L, F358A, and V360A Lead to Tighter Interhelical Packing of TM1, TM2, and TM7

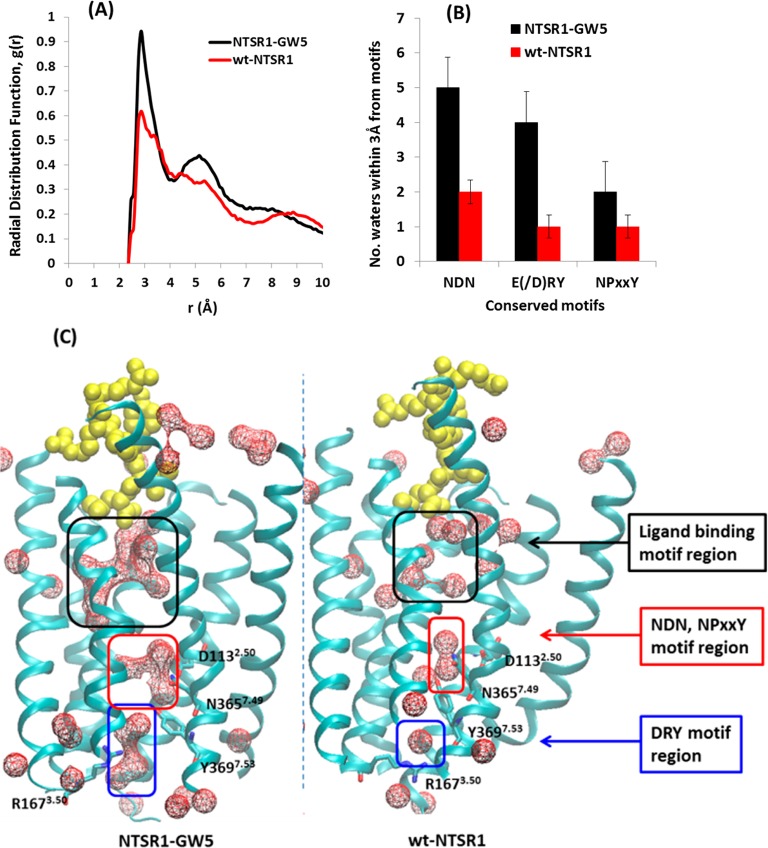

Shibata et al. measured the experimental stability of the A86L1.54 single mutation to be 656% of the wild type in the presence of full length [3H]NTS.20,35 We calculated the difference in the interhelical hydrogen bonds as well as vdW interactions between NTSR1-GW5 and the wild type receptor in the neighborhood of the mutation position A86L1.54. Figure 6 shows interhelical hydrogen bonds that are within 5 Å of the mutation A86L1.54. Compared to wt-NTSR1, NTSR1-GW5 shows an increased number of interhelical hydrogen bond interactions between TM1, TM2, and TM7 in the neighborhood of the A86L1.54 mutation.

Figure 6.

Differences in the interhelical interaction due to the mutation A86L1.54. (A) The direct and indirect contacts of N821.50 with A1102.47 and S3627.46 in the vicinity of the A86L1.54 mutation in NTSR1-GW5 (B) and the wild type receptor. Two waters that have important roles in indirect contacts between N821.50 and S3627.46 were observed in 53 and 83% of the snapshots from MD simulation trajectories, respectively. (C and D) Hydrophobic interaction pattern near the A86L1.54 mutation in NTSR1-GW5 and wild type receptor. The T791.47–L1142.51 and A86L1.54–L1142.51 interactions in NTSR1-GW5 and T851.53–A1102.47 hydrophobic interaction in the wild type receptor are highlighted by orange double arrows. The van der Waals surfaces of the atoms are shown as mesh, and the distances shown in orange are in Å.

The residue N821.50 makes a water mediated hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of S3627.46 and another water mediated hydrogen bond with the side chain of S3627.46. These two water molecules are present in more than 40% of the conformations in the MD ensemble. The side chain (ND2) of N821.50 makes a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl (O) of A1102.47 on TM2. In contrast, wt-NTSR1 has no direct interactions between TM1, TM2, and TM7. In addition to strong interhelical hydrogen bond interactions near the A86L1.54 mutation in NTSR1-GW5, the effect of A86L1.54 mutation from a short methyl side chain to a long hydrophobic side chain also resulted in improved interhelical vdW interactions between A86L1.54 with A1102.47 and L1142.51, as shown in Figure 6C, that is absent in the wild type receptor (shown in Figure 6D). The wild type NTSR1 shows interaction between T851.53 and A1102.47 that is absent in NTSR1-GW5 dynamics. The variations of the interhelical hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interaction distances near the A86L mutation with time, in NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1, are shown in Figures S5 and S6 (Supporting Information), respectively.

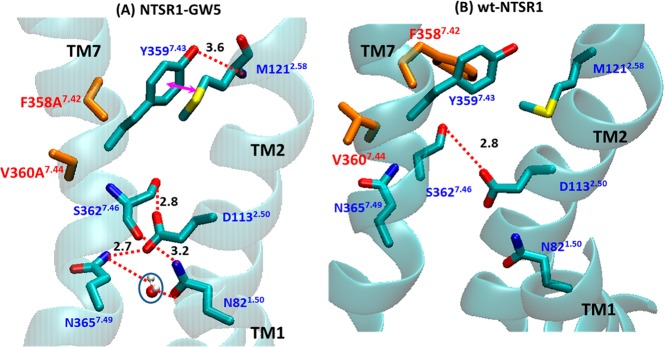

F358A7.42/V360A7.44 are neighboring mutations in NTSR1-GW5. Similar to the effect of A86L1.54, these mutations lead to a strong interhelical hydrogen bond network between N821.50, D1132.50, and S3627.46 and a water mediated hydrogen bond between N821.50 and N3657.49, as shown in Figure 7A. These hydrogen bond networks are not observed in the MD simulation of the wt-NTSR1 (Figure 7B), except for the hydrogen bond interaction between D1132.50–S3627.46. Strong interhelical hydrogen bonds between TM1, TM2, and TM7 in NTSR1-GW5 compared to wt-NTSR1 are shown in Figure S7 (Supporting Information). NTSR1-GW5 also shows favorable interhelical π-stacking interaction between the sulfur atom of M1212.58 and the aromatic side chain of Y3597.43 in the extracellular side of TM2 and TM7 (Figure S8, Supporting Information). In summary, the mutations A86L1.54, F358A7.42, and V360A7.44 improve the interhelical interactions in the mid region of TM1, TM2, and TM7 of NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wt-NTSR1.

Figure 7.

Changes in the interhelical interaction in the neighborhood of the mutations F358A7.42/V360A7.44. (A) The direct and indirect hydrogen bond interactions centered on the F358A7.42/V360A7.44 region of NTSR1-GW5. The water molecule located between N821.50 and N3657.49 has been observed in 59% of the snapshots in the MD simulation ensemble. (B) Corresponding conformation of the wild type NTSR1.

E166A and L310A Lead to Tighter Interhelical Packing of TM3, TM5, and TM6

The E166A3.49 is a charged residue to neutral residue mutation that would abolish the intrahelical salt bridge with R1673.50 that has been observed in the inactive state crystal structures of several class A GPCRs, thus freeing up this arginine residue. The side chain of R1673.50 turns around and makes a direct hydrogen bond with N2575.58 in the crystal structure NTSR1-4GRV.16 However, this hydrogen bond becomes water mediated during the MD simulations of NTSR1-GW5 and facilitates the formation of another interhelical hydrogen bond between R1673.50 and S3737.57 (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Thus, R1673.50 serves as a bridge between TM5 and TM7, making a two-pronged water mediated hydrogen bond network between N2575.58 and S3737.57. The side chain dihedral angle of N2575.58 rotates by about 60° (Figure S10, Supporting Information), facilitating the formation of a hydrogen bond with S1643.47 with 98% of the conformations in the MD ensemble of NTSR1-GW5 showing this hydrogen bond. This interaction is also observed in the crystal structure NTSR1-4GRV. However, the same interaction in the wt-NTSR1MD simulation was observed in less than 50% of the conformation ensemble. The E1663.49 forms a hydrogen bond with H1052.42 in the wt-NTSR1. Mutating E1663.49 to Ala abolishes this hydrogen bond that is however compensated by a direct hydrogen bond between S1623.45–H1052.42, and a water mediated interaction between the backbone atoms of A1663.49 and H1052.42 (Figure S9A, Supporting Information). Thus, the E166A3.49 mutation strengthens the interactions in the intracellular part of the TM3 with TM5 and TM7.

Like E166A3.49, the L310A6.37 mutation also modulates the interhelical interactions in the intracellular region of TM3, TM5, TM6, and TM7 (Figure S11, Supporting Information). In the wt-NTSR1, the side chain of L3106.37 affects the rotamer of N2575.58, such that the interaction between S1643.47 and N2575.58 is mediated by a bridging water molecule (see Figure S11B, Supporting Information). Mutating this residue to Ala in NTSR1-GW5 shortens the side chain and allows a rotamer change of N2575.58 that can then form a hydrogen bond directly with the side chain of S1643.47 (Figure S11A, Supporting Information), thus strengthening the interaction between the two helices. In addition, residue R3116.38 (a neighboring residue of L310A6.37) has a water mediated hydrogen bond with the backbone of N2575.58 in the NTSR1-GW5 in 73% of the snapshots in the MD trajectories. There is a water molecule present at this position in the crystal structure NTSR1-4GRV. In the wt-NTSR1, this interaction is not sustained and observed in less than 50% of the snapshots of the MD simulations. In summary, the L310A6.37 mutation again facilitates the strong interaction in the intracellular region of TM3 with TM5 and TM6. These interactions could hold the TM3, TM5, and TM6 stable in the active-like conformation and possibly restrict the dynamics of the receptor in this region.

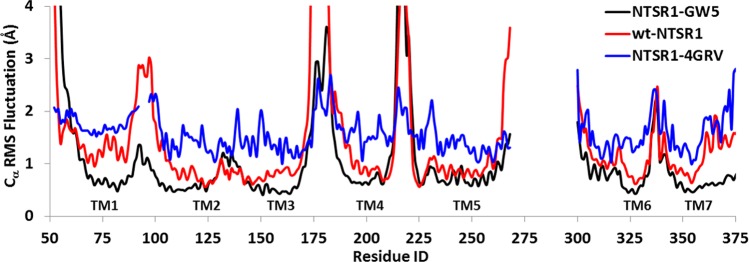

Water Dynamics within the Transmembrane Domain

The number of interhelical water mediated hydrogen bonds is higher in NTSR1-GW5 compared to wt-NTSR1. Therefore, to examine the difference in the extent of hydration between wt-NTSR1 and NTSR1-GW5, we calculated the radial distribution function of water molecules near the receptors for the 2 μs of MD simulation trajectories (Figure 8A). This function gives a quantitative measure of the density of water molecules within 3 Å of the protein residues in the TM region. The density of water molecules in the interior of the NTSR1-GW5 mutant is higher compared to wt-NTSR1, as seen in Figure 8A. We calculated the water map near the ligand binding site and the presumed Na+ ion binding region as well as near other well-conserved and structurally important motifs such as the E(/D)3.49R3.50Y3.51 motif in TM3 and NPxxY in TM7, shown in Figure 8B and C. As seen in Figure 8B, the water population near the highly conserved structural motifs, namely, N1.50D2.50N7.49, E(/D)3.49R3.50Y3.51, and N7.49P7.50xxY7.53, in the NTSR1-GW5 system is higher than that in the wild type receptor.

Figure 8.

(A) Radial distribution function of water from the center of mass (COM) of NTSR1-GW5 (black) and wt-NTSR1 (red). Only waters within the transmembrane domains are calculated in these analyses. (B) Number of water molecules observed in the MD simulations near conserved motifs. NDN motif, N1.50D2.50N7.49; E(/D)RY motif, E(/D)3.49R3.50Y3.51; NPxxY motif, N7.49P7.50xxY7.53. (C) Water density representation within the transmembrane domain of NTSR1-GW5 (left) and wt-NTSR1 (right). The water densities near the ligand binding site and near the E(/D)RY motif are shown by black and blue boxes, while the Na+ ion binding region including the NDN and NPxxY motifs is represented by a red box. Volumetric density maps were isosurface contoured (probe radius of 1.4 Å) using VMD software.

Most of the waters that have persistent density in the interior of the TM region in both the NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 are involved in mediating interhelical contacts. Figure 8C shows the van der Waals surface of the water molecules that are within 3 Å of the residues in the TM region, both in NTSR1-GW5 and in wt-NTSR1. However, the waters within 3 Å of the residues in the TM region of NTSR1-GW5 form larger hydrogen bonded water clusters that improve the interhelical packing compared to the wt-NTSR1. The water clusters form tight hydrogen bond networks between transmembrane helices leading to extra stability, as shown in Figure S12 (Supporting Information). Such large water clusters are not seen in the wt-NTSR1 dynamics. Most of the crystal structures of the class A GPCRs show an interhelical hydrogen bond network (either direct or water mediated) between N1.50, D2.50, and N7.49 residues.36 This region is also the Na+ ion binding region, as seen in the inactive state crystal structures of adenosine receptor A2A,37,38 β1-adrenergic receptor,39 protease-activated receptor (PAR1),40 and an opioid receptor (δ-OR).41 Upon agonist binding to the A2A receptor, the volume of the Na+ ion binding pocket in the receptor shrinks and is no longer able to accommodate the Na+ ion. The number of water molecules around the Na+ ion binding site is less in wt-NTSR1 compared to NTSR1-GW5 (see Figure 8B), implying that the wild type receptor shows greater shrinkage of the Na+ ion pocket compared to NTSR1-GW5.

Homology Modeling of Helix 8 into the NTSR1-GW5 Structure

Although most of all high resolution class A GPCR structures possess an amphipathic helix 8, surprisingly the structures of PAR1 (proteinase activated receptor 1),40 CXCR4 (chemokine receptor 4),42 and NTSR1-4GRV16 do not show helix 8 in their structures. However, helix 8 is present in a more recent crystal structure of a different thermostabilized mutant of NTSR1, although the helix 8 region was found to be less stable than that of other GPCRs.17 The reason for the absence of helix 8 in NTSR1-4GRV is unclear and may be the result of a crystallization artifact, but it may also be caused by its intrinsic instability. Thus, we explored the dynamic behavior of helix 8 in MD simulations of NTSR1-GW5 and of wild type receptor, by modeling helix 8, using the homology modeling technique described in the Methods section. We generated homology models of both NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1, starting from the crystal structure NTSR1-4GRV (PDB code 4GRV)16 until P3667.50 of TM7 (NPxxY region) (Figure S13A, Supporting Information). For the rest of the carboxy terminus sequence that includes helix 8, we used the helix 8 conformation of the crystal structure of NTSR1-TM86V (PDB code 4BUO).17 We followed the same procedure to generate the structure of the wt-NTSR1 with helix 8. The initial structures of NTSR1-GW5 with helix 8, denoted as NTSR1-GW5-H8, and of NTSR1-4GRV are shown in Figure S13A (Supporting Information). It is seen that the residues at the turn of helix 8 show a van der Waals clash with the residues in the intracellular edge of TM7 in the initial NTSR1-GW5-H8 structure. Starting from these initial structures, we performed 1 μs of MD simulations on both of these NTSR1 systems with helix 8. We observed that the helix 8 unravels spontaneously during these simulations in both NTSR1-GW5-H8 and wt-NTSR1-H8, as shown in Figure S13B (Supporting Information). This could mean that helix 8 is not stable in NTSR1-GW5, due to steric hindrance between the hydrophobic residues of P3667.50 and F380H8 and N3707.54 and F380H8. Details of the specific electrostatic and van der Waals interaction in the initial NTSR1-H8 homology models, that lead to the clashes of TM7 and helix 8, are listed in Table S8 (Supporting Information).

We performed a detailed analysis of the helix 8 unraveling in other class A GPCRs for which we have done at least 1 μs of MD simulations in explicit lipid bilayer and water. These simulations include class A GPCRs in both the inactive and active states. Table S9 of the Supporting Information shows that, while helix 8 remains largely intact during the MD simulations of the inactive state GPCRs, they are rather flexible and unravel in the active state or the active-like conformations.

Finally, we have analyzed the R3.50 and Y7.53 inter-residue distance in the NTSR1-GW5 and wt-NTSR1 in the presence of helix 8 (Figure S14, Supporting Information). We observed that the distance of TM3 and TM7 does increase in the NTSR1-GW5 more than wt-NTSR1 with and without helix 8 present (see Figure 2C also). We also observed a strong and persistent hydrogen bond between R1673.50 and S3737.57 and van der Waals interaction between Y3697.53 and V1603.43 in the wild type that is absent in GW5, which could lead to the inward movement of TM7 that is absent in the GW5.

Discussion

Our study is, to our knowledge, the first MD simulation study on the neurotensin peptide receptor NTSR1 with NTS bound, with the aim of understanding the structural basis of thermostabilization and activation. We performed 2 μs of MD simulation on the two systems, namely, the thermostable mutant NTSR1-GW5 and its wild type counterpart (wt-NTSR1). The NTSR1-GW5 is stabilized by enthalpic contributions from increased interhelical hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions within the receptor, as well as receptor–lipid (POPC) interactions. The layer of annular lipids (POPC) packs tighter around the NTSR1-GW5 compared to the wt-NTSR1, and this could lead to increased stability and reduced flexibility in the dynamics of the thermostable mutants. This observation is consistent with our previous studies on the dynamics of thermostable mutants of the β1-adrenergic receptor,43 adenosine A2A receptor.44 Experimentally, the thermostability of adenosine A2A receptor mutants reconstituted in surfactants was found to be dependent on the amount of lipid in the surfactant micelles.45 Adding lipids to the surfactant micelles led to improved thermostability in some of the mutant receptors. The tight packing of lipids around the GW5 mutant observed in our simulations could be a possible mechanism of thermostabilization in other GPCRs. The reduced flexibility and dynamics of the thermostable mutant receptors could result in reduced efficacy of these receptors to couple to G-proteins.

In NTSR1-GW5, all the thermostabilizing mutations (with the exception of A86L1.54) are alanine mutations. Alanine mutations are presumed to lead to “loss of effect” where the effect of the mutation is usually detrimental to the receptor stability compared to the wild type, due to the loss of side chain packing interactions. However, in NTSR1 (and other GPCRs such as β1AR and A2AR), alanine mutations lead to increased thermostability by improving the nonbonded contacts among neighboring residues. The point mutations show increased water mediated interhelical hydrogen bonds in the neighborhood of the respective mutation positions. Each of the six mutations in NTSR1-GW5 lead to tighter interhelical packing through water mediated inter helical hydrogen bonds in the middle of TM1, TM2, and TM7, as well as at the intracellular end of TM3, TM5, and TM6. Water molecules form hydrogen bonded water clusters similar to “ice-like waters” in the NTSR1-GW5 MD simulations. Moreover, the mutant A86L1.54 also shows increased side chain–backbone hydrogen bonds. The MD simulations also showed improved interhelical van der Waals packing in the neighborhood of the point mutations due to rearrangement of side chain conformations. This is consistent with our observations in the previous work on β2AR and A2AR thermostable mutants.44

Analysis of four different types of inter-residue distances during the MD simulations that characterize receptor activation in GPCRs (obtained from analyzing crystal structures of active and inactive states) shows that NTSR1-GW5, in contrast to wt-NTSR1, is an active-like state that shows reduced propensity to go to the fully active R* conformation, as defined by the structure of β2AR bound to G protein. The global motion analysis obtained from PCA shows that NTSR1-GW5 is less dynamic and less flexible than wt-NTSR1. The extent of the movement of TM6 away from TM3 is higher in the wt-NTSR1 compared to the NTSR1-GW5 mutant. The wt-NTSR1 has a lesser number of water molecules near the putative Na+ ion binding site in the TM1–TM2–TM7 region and near the well conserved motif NPxxY in TM7, showing that the wt-NTSR1 in the active-like state shows more potential to be activated than the NTSR1-GW5. These analyses that signify activation are consistent with the experimental observation that the wild type of NTSR1 activates the G-protein but NTSR1-GW5 does not.16 In the GW5 mutant, the thermostabilizing mutations stabilized an active-like receptor conformation, and in the process reduced the flexibility of the wild type receptor that is essential for GPCR activation and coupling to the G-protein. This is possibly due to the strong interhelical hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts that are formed in the thermostable mutant due to the single point mutations leading to the rearrangement of side chains in the neighboring residues. The single point mutations also lead to improved lipid interactions with residues within 7 Å of the mutation positions. There is formation of a tight annular lipid bilayer around the NTSR1-GW5 compared to wt-NTSR1. Thus, it is could be a challenge to design a GPCR thermostable mutant that preserves the full signaling efficacy of the wild type receptor, since it is difficult to decouple the thermostabilizing effect from the conformational flexibility. Our simulations showed that the presence of helix 8 in the active-like NTSR1-GW5 conformation leads to van der Waals clash and instability.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work to N.V. was provided by NIH-RO1GM097261. Anton computer time was provided by the National Center for Multiscale Modeling of Biological Systems (MMBioS) through Grant P41GM103712-S1 from the National Institutes of Health and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC). The Anton machine at PSC was generously made available by D.E. Shaw Research. C.G.T. is funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC U105197215), and the research of R.G. is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting Information Available

Details on data sets for MD simulations along with supporting figures and tables. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Carraway R.; Leeman S. E. The Isolation of a New Hypotensive Peptide, Neurotensin, from Bovine Hypothalami. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248, 6854–6861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissette G.; Nemeroff C. B.; Loosen P. T.; Prange A. J. Jr.; Lipton M. A. Hypothermia and Intolerance to Cold Induced by Intracisternal Administration of the Hypothalamic Peptide Neurotensin. Nature 1976, 262, 607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimpff R. M.; Avard C.; Fenelon G.; Lhiaubet A. M.; Tenneze L.; Vidailhet M.; Rostene W. Increased Plasma Neurotensin Concentrations in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2001, 70, 784–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alifano M.; Souaze F.; Dupouy S.; Camilleri-Broet S.; Younes M.; Ahmed-Zaid S. M.; Takahashi T.; Cancellieri A.; Damiani S.; Boaron M.; et al. Neurotensin Receptor 1 Determines the Outcome of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2010, 16, 4401–4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel G.; Holsboer F. Neuropeptide Receptor Ligands as Drugs for Psychiatric Diseases: The End of the Beginning?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 462–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabgi P. Targeting Neurotensin Receptors with Agonists and Antagonists for Therapeutic Purposes. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2002, 5, 764–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan A. J.; Deupi X.; Lebon G.; Tate C. G.; Schertler G. F.; Babu M. M. Molecular Signatures of G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. Nature 2013, 494, 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. G. F.; DeVree B. T.; Zou Y. Z.; Kruse A. C.; Chung K. Y.; Kobilka T. S.; Thian F. S.; Chae P. S.; Pardon E.; Calinski D.; et al. Crystal Structure of the Beta(2) Adrenergic Receptor-Gs Protein Complex. Nature 2011, 477, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K.; Kruse A. C.; Asada H.; Yurugi-Kobayashi T.; Shiroishi M.; Zhang C.; Weis W. I.; Okada T.; Kobilka B. K.; Haga T.; et al. Structure of the Human M2Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Bound to an Antagonist. Nature 2012, 482, 547–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V.; Rosenbaum D. M.; Hanson M. A.; Rasmussen S. G.; Thian F. S.; Kobilka T. S.; Choi H. J.; Kuhn P.; Weis W. I.; Kobilka B. K.; et al. High-Resolution Crystal Structure of an Engineered Human Beta2-Adrenergic G Protein-Coupled Receptor. Science 2007, 318, 1258–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehan B. G.; Bortolato A.; Blaney F. E.; Weir M. P.; Mason J. S. Unifying Family a GPCR Theories of Activation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 143, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror R. O.; Jensen M. O.; Borhani D. W.; Shaw D. E. Exploring Atomic Resolution Physiology on a Femtosecond to Millisecond Timescale Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010, 135, 555–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J. A.; Weinstein H.. Integrated Methods for the Construction of Three-Dimensional Models and Computational Probing of Structure-Function Relations in G Protein-Coupled Receptors. In Methods in Neurosciences; Stuart C. S., Ed.; Academic Press: 1995; Vol. 25, pp 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. G.; Choi H. J.; Fung J. J.; Pardon E.; Casarosa P.; Chae P. S.; Devree B. T.; Rosenbaum D. M.; Thian F. S.; Kobilka T. S.; et al. Structure of a Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Beta(2) Adrenoceptor. Nature 2011, 469, 175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A. S.; Elgeti M.; Zachariae U.; Grubmuller H.; Hofmann K. P.; Scheerer P.; Hildebrand P. W. Position of Transmembrane Helix 6 Determines Receptor G Protein Coupling Specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11244–11247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. F.; Noinaj N.; Shibata Y.; Love J.; Kloss B.; Xu F.; Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J.; Shah P.; Shiloach J.; Tate C. G.; et al. Structure of the Agonist-Bound Neurotensin Receptor. Nature 2012, 490, 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff P.; Hillenbrand M.; Klenk C.; Batyuk A.; Heine P.; Balada S.; Schlinkmann K. M.; Scott D. J.; Schutz M.; Pluckthun A. Structure of Signaling-Competent Neurotensin Receptor 1 Obtained by Directed Evolution in Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, E655–E662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. H.; Scheerer P.; Hofmann K. P.; Choe H. W.; Ernst O. P. Crystal Structure of the Ligand-Free G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Opsin. Nature 2008, 454, 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H. W.; Kim Y. J.; Park J. H.; Morizumi T.; Pai E. F.; Krauss N.; Hofmann K. P.; Scheerer P.; Ernst O. P. Crystal Structure of Metarhodopsin Ii. Nature 2011, 471, 651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y.; White J. F.; Serrano-Vega M. J.; Magnani F.; Aloia A. L.; Grisshammer R.; Tate C. G. Thermostabilization of the Neurotensin Receptor NTS1. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 390, 262–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D. E.; Dror R. O.; Salmon J. K.; Grossman J. P.; Mackenzie K. M.; Bank J. A.; Young C.; Deneroff M. M.; Batson B.; Bowers K. J.; et al. Millisecond-Scale Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Anton. In Proceedings of the Conference on High Performance Computing Networking, Storage and Analysis; ACM: Portland, OR, 2009; pp 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N.; Webb B.; Marti-Renom M. A.; Madhusudhan M. S.; Eramian D.; Shen M. Y.; Pieper U.; Sali A.. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using Modeller. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2006, Chapter 5, Unit 5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti-Renom M. A.; Stuart A. C.; Fiser A.; Sanchez R.; Melo F.; Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling of Genes and Genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000, 29, 291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell A. D.; Bashford D.; Bellott M.; Dunbrack R. L.; Evanseck J. D.; Field M. J.; Fischer S.; Gao J.; Guo H.; Ha S.; et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackerell A. D. Jr.; Feig M.; Brooks C. L. III. Extending the Treatment of Backbone Energetics in Protein Force Fields: Limitations of Gas-Phase Quantum Mechanics in Reproducing Protein Conformational Distributions in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1400–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglov D.; Roux B. Finite Representation of an Infinite Bulk System - Solvent Boundary Potential for Computer-Simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 9050–9063. [Google Scholar]

- Klauda J. B.; Venable R. M.; Freites J. A.; O’Connor J. W.; Tobias D. J.; Mondragon-Ramirez C.; Vorobyov I.; MacKerell A. D. Jr.; Pastor R. W. Update of the Charmm All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 7830–7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D. E.; Maragakis P.; Lindorff-Larsen K.; Piana S.; Dror R. O.; Eastwood M. P.; Bank J. A.; Jumper J. M.; Salmon J. K.; Shan Y.; et al. Atomic-Level Characterization of the Structural Dynamics of Proteins. Science 2010, 330, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautler V.; Van Gunsteren W. F.; Hunenberger P. H. A Fast Shake: Algorithm to Solve Distance Constraint Equations for Small Molecules in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y.; Klepeis J. L.; Eastwood M. P.; Dror R. O.; Shaw D. E. Gaussian Split Ewald: A Fast Ewald Mesh Method for Molecular Simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 54101–54113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D.; Lindahl E.; Hess B.; Groenhof G.; Mark A. E.; Berendsen H. J. Gromacs: Fast, Flexible, and Free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen M. J.; Bhattacharya S.; Vaidehi N. The Role of Conformational Ensembles in Ligand Recognition in G-Protein Coupled Receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13197–13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand P. W.; Gunther S.; Goede A.; Forrest L.; Frommel C.; Preissner R. Hydrogen-Bonding and Packing Features of Membrane Proteins: Functional Implications. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 1945–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F. X.; Cocco M. J.; Russ W. P.; Brunger A. T.; Engelman D. M. Interhelical Hydrogen Bonding Drives Strong Interactions in Membrane Proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000, 7, 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y.; Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J.; Love J.; Kloss B.; White J. F.; Grisshammer R.; Tate C. G. Optimising the Combination of Thermostabilising Mutations in the Neurotensin Receptor for Structure Determination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 1293–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo L.; Deupi X.; Dolker N.; Lopez-Rodriguez M. L.; Campillo M. The Role of Internal Water Molecules in the Structure and Function of the Rhodopsin Family of G Protein-Coupled Receptors. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-de-Teran H.; Massink A.; Rodriguez D.; Liu W.; Han G. W.; Joseph J. S.; Katritch I.; Heitman L. H.; Xia L.; Ijzerman A. P.; et al. The Role of a Sodium Ion Binding Site in the Allosteric Modulation of the a(2a) Adenosine G Protein-Coupled Receptor. Structure 2013, 21, 2175–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Chun E.; Thompson A. A.; Chubukov P.; Xu F.; Katritch V.; Han G. W.; Roth C. B.; Heitman L. H.; IJzerman A. P.; et al. Structural Basis for Allosteric Regulation of GPCRs by Sodium Ions. Science 2012, 337, 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Gallacher J. L.; Nehme R.; Warne T.; Edwards P. C.; Schertler G. F.; Leslie A. G.; Tate C. G. The 2.1 A Resolution Structure of Cyanopindolol-Bound Beta1-Adrenoceptor Identifies an Intramembrane Na+ Ion That Stabilises the Ligand-Free Receptor. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Srinivasan Y.; Arlow D. H.; Fung J. J.; Palmer D.; Zheng Y.; Green H. F.; Pandey A.; Dror R. O.; Shaw D. E.; et al. High-Resolution Crystal Structure of Human Protease-Activated Receptor 1. Nature 2012, 492, 387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenalti G.; Giguere P. M.; Katritch V.; Huang X. P.; Thompson A. A.; Cherezov V.; Roth B. L.; Stevens R. C. Molecular Control of Delta-Opioid Receptor Signalling. Nature 2014, 506, 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B.; Chien E. Y.; Mol C. D.; Fenalti G.; Liu W.; Katritch V.; Abagyan R.; Brooun A.; Wells P.; Bi F. C.; et al. Structures of the CXCR4 Chemokine GPCR with Small-Molecule and Cyclic Peptide Antagonists. Science 2010, 330, 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen M. J.; Bhattacharya S.; Grisshammer R.; Tate C. G.; Vaidehi N. Thermostabilization of the Beta1-Adrenergic Receptor Correlates with Increased Entropy of the Inactive State. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 7283–7291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Bhattacharya S.; Grisshammer R.; Tate C.; Vaidehi N. Dynamic Behavior of the Active and Inactive States of the Adenosine a(2a) Receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 3355–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani F.; Shibata Y.; Serrano-Vega M. J.; Tate C. G. Co-Evolving Stability and Conformational Homogeneity of the Human Adenosine A2a Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 10744–10749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.