Abstract

Social and biological contagions are influenced by the spatial embeddedness of networks. Historically, many epidemics spread as a wave across part of the Earth’s surface; however, in modern contagions long-range edges—for example, due to airline transportation or communication media—allow clusters of a contagion to appear in distant locations. Here we study the spread of contagions on networks through a methodology grounded in topological data analysis and nonlinear dimension reduction. We construct “contagion maps” that use multiple contagions on a network to map the nodes as a point cloud. By analyzing the topology, geometry, and dimensionality of manifold structure in such point clouds, we reveal insights to aid in the modeling, forecast, and control of spreading processes. Our approach highlights contagion maps also as a viable tool for inferring low-dimensional structure in networks.

Considerable research during the past few decades has aimed to understand spreading dynamics on networks [1–5]—a widespread phenomenon that occurs in diverse settings that range from biological epidemics [6–8] to collective social processes such as social movements [9] and innovation diffusion [10]. To study spreading, it is useful to contrast two classes of networks: “geometric networks,” in which nodes lie in a metric space and are connected by short-range “geometric edges” that are constrained by the nodes’ locations (e.g., lattices that describe discretized partial differential equations [11]), and networks that are not geometric, in the sense that their edges are not constrained or defined by distances between nodes. Although the embedding of nodes in a metric space is ubiquitous for spatial networks on Earth’s surface [12], recent studies have explored the mapping of nodes in a network to locations in a (potentially) latent and (typically) low-dimensional metric space for an extensive variety of applications. Such applications include inferring missing and spurious edges in networks [13–16]; efficiently routing information across the internet [17, 18]; identifying node-specific attributes that are responsible for edge formation in social networks [19]; and nonlinear dimension reduction of proximity networks inferred from point-cloud data (e.g., images, videos, and time series) for data-storage and signal-processing applications [20–27].

When dynamics such as contagions occur on a geometrically-embedded network, it is fundamental to question the extent to which the dynamics follows such underlying low-dimensional structure. This question is particularly important and difficult for geometric networks that are supplemented with long-range “non-geometric edges,” which directly connect nodes that are distant from each other with respect to an underlying metric space. Long-range edges arise in numerous applications, either by chance (e.g., subways that connect distant parts of cities) [12] or as a result of merging distinct layers in multilayer networks [28]. In some scenarios, they can also be construed as a source of “noise” in an otherwise geometric network (e.g., when edges arise due to the presence of noise for inferred proximity networks [25, 26]). They also play important roles in small-world network models [29] such as Watts-Strogatz [30], Newman-Watts [31], and Kleinberg [32] networks. Because we are interested in the geometric embeddedness of such networks, we use the term “noisy geometric networks” for networks that include non-geometric edges as supplements to geometric edges. (See Figs. 1–2 for examples).

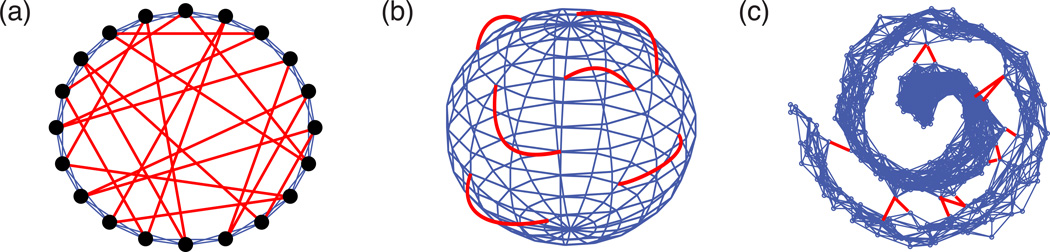

FIG. 1. Examples of noisy geometric networks.

Nodes are embedded in three manifolds: (a) a ring (1D) embedded as a circle in ℝ2; (b) a spherical surface (2D) in ℝ3; and (c) a bounded plane (2D) embedded (nonlinearly) in ℝ3 in a configuration known as the “swiss roll” [22]. Given a network with “geometric edges” (blue), in panels (a)–(b), we add “non-geometric edges” (red) uniformly at random. In panel (c), by contrast, we add noise to the nodes’ locations in the ambient space and place edges between nodes that are nearby in that space. In this scenario, we interpret edges between nodes that are nearby with respect to the ambient space but not the manifold as the nongeometric edges.

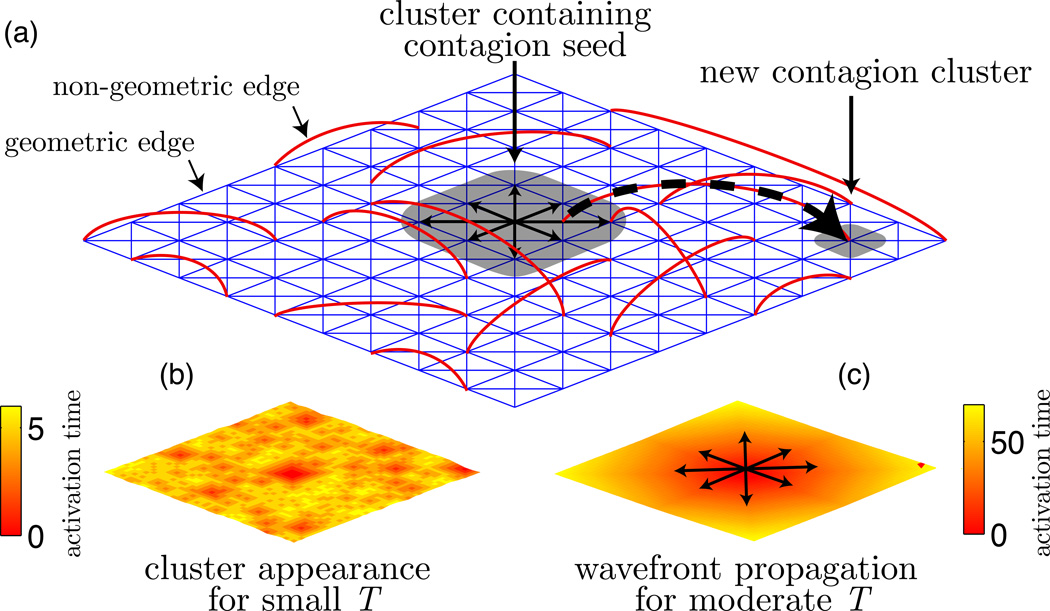

FIG. 2. Wavefront propagation and the appearance of new clusters.

(a) Contagions on a noisy geometric network containing geometric edges along a manifold (in this case, a two-dimensional lattice, which we indicate with the blue edges) and non-geometric edges (red edges), which introduce shortcuts in the network. We study two phenomena in the evolution of contagion clusters (shaded areas): “wavefront propagation” (WFP) describes the outward expansion of a contagion cluster’s boundary, and the “appearance of a new contagion cluster” (ANC) occurs when a contagion spreads exclusively along non-geometric edges (dashed arrow). (b,c) We examine WFP and ANC for the Watts threshold model (WTM) [44] for complex contagions by studying node activation times (i.e., the times at which nodes adopt the contagion), which depend on the WTM thresholds {Ti}, which we take to be identical for every node (i.e., Ti = T for all i). (b) For small T, frequent ANC leads to rapid dissemination of a contagion. (c) For moderate T, little to no ANC occurs and WFP leads to slow dissemination. For large T, there is no spreading. For a given network, activation times across multiple realizations of a contagion (with varying initial conditions) map the nodes to a point cloud via what we call a “WTM map”.

The presence of long-range edges can significantly alter how processes spread [30–33]. For example, it is traditional to characterize contagions in a geometric setting using “wavefront propagation” (WFP) [3], which agrees with the qualitative properties of historical epidemics such as the Black Death [34]. By contrast, Refs. [6–8] (and numerous other sources [1]) have highlighted that modern biological epidemics tend to be dominated by long-range transportation networks, such as airline networks or railway networks, rather than by geographic proximity. Spreading across long-range edges can result in the “appearance of new clusters” (ANC) of a contagion that are spatially-distant, which is an important phenomenon in the dynamics of recent global epidemics [35]. Indeed, it has been reported that prominent strains of influenza (e.g., H1N1/09) exhibited a pattern of “skip-and-resurgence” (in which some countries avoided outbreaks in some years) during recent worldwide outbreaks [36]. In addition, long-range edges can also have significant effects on social contagions [37–40]. Given the (either implicit or explicit) geometric embeddedness for so many of the networks on which ideas and diseases spread [1, 12], an improved understanding of contagions on noisy geometric networks is important for numerous applications, which range from the identification of influential spreaders of information [41] to control of biological epidemics [42, 43].

WFP and ANC can be very different in social versus biological contagions. One important difference arises from phenomena such as social reinforcement [37–40], which occurs only for social contagions. In Fig. 2, we illustrate the prominent effect of social reinforcement for the Watts threshold model (WTM) [44] of social contagions. The WTM is a generalization of bootstrap percolation [45] and is based on the idea that each node i has some threshold Ti ≥ 0 [46] for adopting a social contagion (i.e., for becoming infected). The threshold dynamics gives rise to the characterization of the WTM as a so-called “complex” contagion because the dynamics at each node i depend on the states of all neighboring nodes, and it might be necessary for multiple neighbors to be infected before node i adopts a contagion. Importantly, for some threshold values, WFP can dominate ANC even in the presence of many “noisy” edges—a phenomenon that has widespread applications (see Sec. II and our Supplementary Discussion).

In the present paper, we study bifurcations in WFP and ANC dynamics by examining data that are generated by several contagions on a given noisy geometric network. Our methodology is grounded in the field of computational topology [47, 48], and we note that there has been rapidly intensifying interest (see, e.g., [49–52]) in using tools from computational topology to study structural features in networks and for machine learning [53]. In taking this perspective, we introduce a map from the network nodes to points in a metric space based on contagion dynamics. By analogy to diffusion maps [24] and similar ideas in nonlinear dimension reduction and manifold learning [20–27], we use the term “contagion maps” for these maps. We investigate the topology, geometry, and dimensionality properties of these maps, and we find for the contagion regime that predominantly exhibits WFP versus ANC that these properties correspond to the manifold that underlies the noisy geometric network. We examine both synthetic and empirical networks, including a transit system in London (see Sec. I F, Supplementary Note 1, and Supplementary Figs. 1–5). Given that the manifold structure in a contagion map can reflect the underlying manifold structure of a noisy geometric network, contagion maps also help for the identification of such underlying structure. This has numerous applications, including for the denoising of networks (see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 6–7).

I. RESULTS

A. Noisy Geometric Networks

Noisy geometric networks are a class of networks that arise from geometric networks [12] but also include non-geometric, “noisy” edges. Consider a set 𝒱 of network nodes that have intrinsic locations {w (i)}i∈𝒱 in a metric space. We restrict our attention to nodes that lie on a manifold ℳ that is embedded in an ambient space 𝒜 (i.e., w(i) ∈ ℳ ⊂ 𝒜). We use the term “node-to-node distance” to refer to the distance between nodes in this embedding space 𝒜, which we equip with the Euclidean norm ‖·‖2 (although one can also use other metrics [17]). To create a noisy geometric network, we place the nodes in the underlying manifold and add two families of edges: (1) a set ℰ(G) of geometric edges, such that (i, j) ∈ ℰ(G) when nodes i and j are sufficiently close to one another (i.e., the length of shortest path along the manifold ℳ that connects the two nodes is less than some distance threshold); and (2) a set ℰ(NG) of non-geometric edges, which we place using some random process between pairs of nodes (i, j), where i ≠ j and (i, j) ∉ ℰ(G). In Figs. 1(a,b), we show examples of constructing noisy geometric networks by adding non-geometric edges uniformly at random. In Fig. 1(c), we show a construction that is motivated by nonlinear dimension reduction of point-cloud data [22–26].

As an illustrative example, consider the noisy ring lattice in Fig. 1(a), which is similar to the Newman-Watts variant of the Watts-Strogatz small-world model [30, 31]. Specifically, we consider N nodes that are uniformly spaced along the unit circle in ℝ2. We then add geometric edges so that every node i is connected to its d(G) nearest-neighbor nodes. (Note that there are no self-edges.) We then add d(NG) non-geometric edges to each node and connect the ends of these edges (i.e., the stubs) uniformly at random while avoiding self-edges and multiedges. The resulting network is a (d(G) + d(NG))-regular network that contains Nd(G)/2 geometric edges and Nd(NG)/2 non-geometric edges. We can thus specify this class of random networks using three parameters: N, d(G), and d(NG). It is also useful to define the ratio α = d(NG)/d(G) of non-geometric to geometric edges. Our construction assumes that N and d(G) are even. In Fig. 1(a), we depict a noisy ring network with N = 20 and (d(G), d(NG)) = (4, 2). In Supplementary Note 3 (see also Supplementary Figs. 8–9), we study models of noisy geometric networks on a ring manifold that incorporate heterogeneity in the nodes’ degrees and/or locations.

B. Watts Threshold Model (WTM)

We analyze a well-known dynamical system for social contagions: the Watts threshold model (WTM) for complex contagions [44]. In addition to allowing analytical tractability, we have two other motivations for using the WTM. First, WTM contagions yield “filtrations” of a network and thereby allow us to develop a methodology grounded in computational topology [47–52]. Second, the WTM is a simple-but-insightful model for social influence that has the virtue of explicitly considering social reinforcement [37–39].

We define a WTM contagion as follows. Given an un-weighted network (which we represent using an adjacency matrix A) with a set 𝒱 of nodes and a set ℰ of edges, we let ηi(t) denote the state of node i ∈ 𝒱 at time t, where ηi(t) = 1 indicates adoption (i.e., infection) and ηi(t) = 0 indicates non-adoption. We initialize a contagion at time t = 0 by choosing a set of nodes 𝒮 ⊂ 𝒱 and setting ηi(0) = 1 for i ∈ 𝒮 and ηi(0) = 0 for all other nodes. We refer to 𝒮 as the “contagion seed.” We consider synchronous updating in discrete time [4], so a node i that has not already adopted the contagion at time t [i.e., ηi(t) = 0] will adopt it during the next time step [i.e., ηi(t + 1) = 1] if and only if fi > Ti, where Ti is a node-specific adoption threshold and denotes the fraction of neighbors that are infected and di = ∑j Aij is the degree of node i. (Note that this is a slight modification from the original WTM [44], which uses the adoption criterion fi ≥ Ti.) We repeat this process until the system reaches an equilibrium point at some time t* < N (i.e., no further adoptions occur). For each node i, we let x(i) denote the node’s “activation time,” which is the time t at which the node adopts the contagion. Given {Ti} and the contagion seed, a WTM contagion on a network is a deterministic process. Additionally, a node’s adoption of the contagion is irreversible (i.e., there is no unadoption in this model), so the dynamics are monotonic in the sense that the subset ℐ(t) ⊆ 𝒱 of infected nodes at time t is non-decreasing with time [i.e., ℐ(t) ⊆ ℐ(t + 1)]. One can thus use the contagion to construct a “filtration” of the network nodes 𝒱. (See Refs. [47, 48] and our discussion in Supplementary Note 4.)

C. Contagion Maps

We study contagion maps based on WTM contagions, and we refer to these maps as “WTM maps.” A WTM map is a nonlinear map of nodes in a network to a point cloud in a metric space based on the activation times from several realizations of a WTM contagion. Given J realizations of a WTM contagion on a network with different initial conditions, the associated WTM map is a function from 𝒱 to ℝJ that records the activation time of the ith node in the jth realization. More precisely, we define a “regular” WTM map as 𝒱sto{x(i)}i∈𝒱 ∈ ℝJ, where . In practice, we enumerate the contagions j = 1, 2, …, J ≤ N, and we initialize the jth contagion at a contagion seed 𝒮(j) such that {j} ⊆ 𝒮(j) for each j. (Note that one can select any J nodes as seeds by relabeling the nodes.) In addition to the regular WTM map 𝒱sto{x(i)}i∈𝒱, we also define “reflected” and “symmetric” versions of the WTM map for the subset of nodes 𝒥 = {1, 2, …, J} ⊆ 𝒱. Letting and , we define the reflected WTM map 𝒥sto{y(i)}i∈𝒥 ∈ ℝN and symmetric WTM map 𝒥sto{z(i)}i∈𝒥 ∈ ℝJ. For a given network and thresholds {Ti}, the regular, reflected, and symmetric WTM maps are deterministic.

The choice of contagion seeds {𝒮(j)} plays a crucial role in determining the dynamics of WTM contagions and a WTM map. In practice, we use J = N realizations of a WTM contagion for an N-node network, for which we initialize the jth realization with a contagion seed 𝒮(j) = {j} ⋃ {k|Ajk ≠ 0} that includes node j and its network neighbors. We use the term “cluster seeding” to describe this type of initial condition, which we illustrate in Fig. 3. By contrast, we use the term “node seeding” to refer to the initialization of a contagion at a single node: 𝒮(j) = {j}. Additionally, note that setting J = N yields 𝒥 = 𝒱, and then the complete set of nodes is mapped by all versions of a WTM map. In Supplementary Note 5 (see also Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 1) we show that the typical computational complexity for constructing a WTM map is 𝒪(NM), where M is the number of edges. See Sec. IIIA for code, which we have made available, that constructs WTM maps.

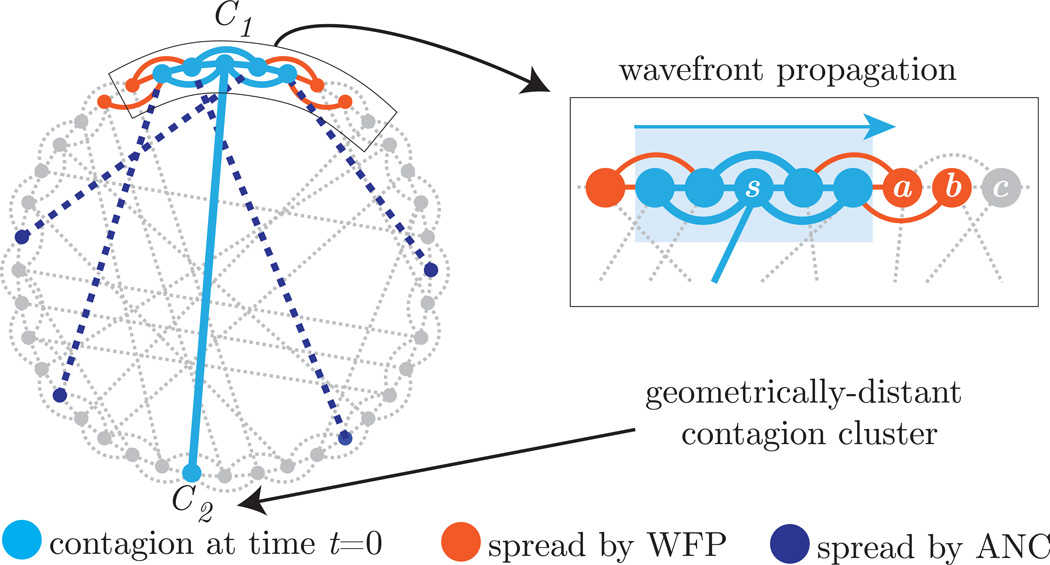

FIG. 3. Contagion initialized with cluster seeding.

A WTM contagion on a noisy ring lattice in which each node has d(G) = 4 geometric edges and d(NG) = 1 non-geometric edge. We initialize the contagion at time t = 0 by setting node s and its network neighbors as infected (indicated by the light blue nodes and edges). This results in two contagion clusters: C1 and C2. At time t = 1, depending on the WTM thresholds {Ti}, additional nodes can adopt the contagion either via WFP and/or via ANC. As indicated by the orange nodes and edges, nodes that are in the “boundary” of C1 can adopt the contagion via WFP traveling around the underlying ring lattice. We illustrate this idea further in the magnifying box, where nodes a and b in the boundary of C1 can potentially become infected in the first time step. Alternatively, nodes that share only a non-geometric edge with a contagion seed can potentially become infected via ANC (as indicated by the dark blue nodes and dashed edges).

We now motivate our choice for contagion initialization. The requirement that {j} ⊆ 𝒮(j) is convenient because it allows us to think of the activation time as a notion of distance from node j to node i (i.e., it describes the time that is required for a contagion to travel from node j to i). This choice is akin to the diffusion distance [24] and commutetime distance [54] derived from diffusion dynamics (although the latter is known to have shortcomings for certain classes of networks [55]). To illustrate this point, suppose that contagion seeds are individual nodes (i.e., 𝒮j = {j} for j ∈ 𝒱), and suppose that we construct the WTM map 𝒱sto{x̃(i)}i∈𝒱 for Ti = T = 0 for each node i ∈ 𝒱. In this case, the activation time exactly recovers the length of the shortest path between nodes i and j, and this in turn defines a metric on the discrete space 𝒱. In fact, the N × N matrix X̃ = [x̃(1),…, x̃(N)] is a dissimilarity matrix, which is central to many algorithms for dimension reduction [22–26] (including Isomap [22], which implements the mapping of nodes based on shortest paths). Letting Ti > 0 and still assuming that each is finite, we show in Supplementary Note 4 that the symmetric WTM map induces a metric on 𝒱. More generally, we show that a set of “filtrations” induces a metric under certain conditions. Consequently, we find that one can also use topological data analysis of networks to study the embedding geometry of networks.

Although node seeding has wonderful mathematical properties, cluster seeding is very useful in practice because it can allow a contagion to infect a larger fraction of the nodes in a network. When Ti > 0 for each i ∈ 𝒱, it is common for WTM contagions to reach equilibrium points that do not saturate the network with a contagion. This implies that for some i, j ∈ 𝒱. Activation times of infinity pose a problem, because WTM maps are well-defined only for activation times that are finite (see Sec. III C). Contagions initialized with clusters of a contagion are more likely to spread than those that are initialized at a single node [56], so cluster seeding increases the range of threshold choices that yield activation times that are finite. Although WTM maps that we construct using cluster seeding no longer automatically induce a metric on the node set 𝒱, one can still construe as a distance from node j to i if the contagion seeds are sufficiently small, |𝒮(j)| ≪ |𝒱|.

D. WTM Contagions on Noisy Ring Lattices

To guide our experiments on using WTM maps to study WFP and ANC on noisy ring lattices, we conduct a bifurcation analysis for WTM contagions that are initialized with cluster seeding. We present our analysis in detail in Sec. III B and Supplementary Note 6, and we summarize our results here.

Our primary results are two sequences of critical values for the WTM threshold T that depend on the non-geometric degree d(NG) and geometric degree d(G). These critical values determine the presence versus absence of WFP and ANC as well as their rates. The qualitative features of ANC behavior are determined by the thresholds

| (1) |

Whenever , a node requires at least (d(NG) − k) neighbors from non-geometric edges to be infected before it adopts the contagion. This subsequently determines the rate at which new clusters of contagion appear. For , there is no ANC. The qualitative features of WFP are determined by the thresholds

| (2) |

where a wavefront propagates at a speed of k + 1 nodes per time step for . For , there is no WFP.

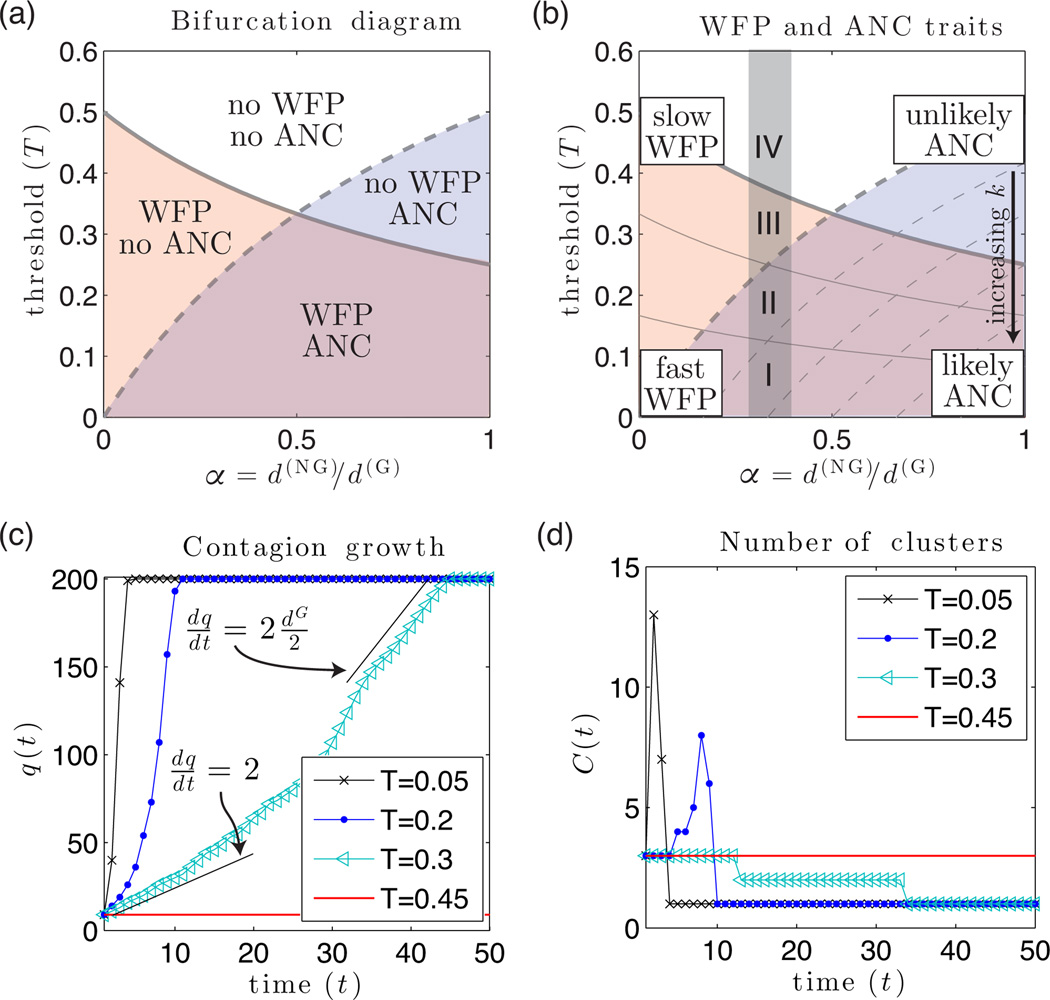

In Fig. 4(a), we show a bifurcation diagram that summarizes the WTM dynamics for various values of the contagion threshold T and ratio α = d(NG)/d(G) of non-geometric edges to geometric edges. The solid and dashed curves, respectively, describe Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) for k = 0. That is, and , which intersect at (α, T) = (1/2, 1/3) and yield four regimes of contagion dynamics that we characterize by the presence versus absence of WFP and ANC. In Fig. 4(b), we plot Eqs. (1) and (2) with other k values for d(G) = 6, where we note that lower curves correspond to larger k. Observe that increasing T for fixed α leads to slower WFP and less frequent ANC. In particular, for (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2) (which implies that α = 1/3), we find four qualitatively different regimes of WFP and ANC traits (see the regions that we label I–IV).

FIG. 4. Bifurcation analysis for WTM contagions on a noisy ring lattice.

(a) We plot the critical thresholds for k = 0 given by Eq. (1) (dashed curve) and Eq. (2) (solid curve) versus the ratio α = d(NG)/d(G) of non-geometric to geometric edges. These curves divide the parameter space into four qualitatively different contagion regimes, which we characterize by the presence versus absence of WFP and ANC. (b) Equations (1) and (2) for other values of k further describe WFP and ANC, and we show them for d(G) = 6. Note that the curves become lower with increasing k. Fixing (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2), which yields α = 1/3, we find four contagion regimes (which we label using the symbols I–IV), where increasing T corresponds to slower WFP and less frequent ANC. (c) For N = 200 and T 2 {0.05, 0.2, 0.3, 0.45}, we plot the contagion size q(t) versus time t for one realization of a WTM contagion with cluster seeding [i.e., q(0) = 1 + d(G) + d(NG) = 9]. We observe, as expected, that the growth rate decreases with T. In particular, for regime III (e.g., T = 0.3), the contagion spreads strictly via WFP, which initially spreads at a rate of 1 node per time step (both clockwise and counter clock wise along the ring) but eventually accelerates to d(G)/2 nodes per time step. As we show using the labeled black lines, we predict and observe linear growth for q(t) when the contagion spreads by WFP and no ANC and either q(t) ≈ 1 or q(t) ≈ N. (See Sec. III B and Supplementary Note 6.) (d) We plot the number of contagion clusters C(t) versus t. As expected, C(t) only increases above its initial value of C(0) = 1 + d(NG) = 3 for regimes I and II (for which ). There is no spreading in regime IV.

In Figs. 4(c,d), we illustrate dynamics from these regimes by choosing T ∈ {0.05, 0.2, 0.3, 0.45} and plotting the size q(t) of the contagion [see Fig. 4(c)] and the number of contagion clusters C(t) [see Fig. 4(d)] versus time t. Note that the number C(t) of contagion clusters is equal to the number of connected components in the subgraph of the original network that only includes infected nodes and geometric edges. The values of q(t) and C(t) that we determine numerically (for N = 200) agree with our analysis. For T = 0.05, the WTM contagion saturates the network [i.e., q(t) → N] very rapidly due in part to the appearance of many contagion clusters early in the contagion process. For T = 0.2, the contagion saturates the network relatively rapidly due to the appearance of some new contagion clusters. For T = 0.3, the contagion saturates the network slowly, as no new contagion clusters appear and the contagion spreads only via WFP. For T = 0.45, the contagion does not saturate the network, as neither WFP nor ANC occur.

E. Analyzing WTM Maps for Noisy Ring Lattices

In this section, we analyze symmetric WTM maps 𝒱sto{z(i)} for noisy ring lattices in several ways: geometrically, topologically, and in terms of dimensionality. Our point-cloud analytics identify parameter regimes in which characteristics of a network’s underlying manifold also appear in the WTM maps. This makes it possible to do manifold learning and to assess the extent to which a contagion exhibits WFP (along a network’s underlying manifold) versus ANC.

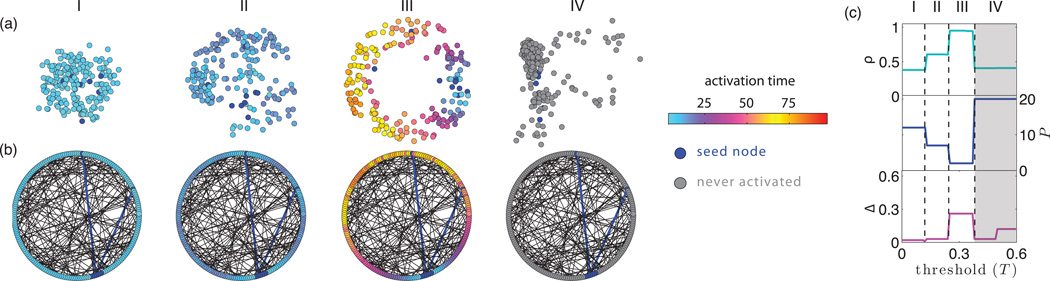

In Fig. 5, we study WTM maps for a noisy ring lattice with N = 200 and (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2). We give each node i an intrinsic location w(i) = [cos(2πi/N), sin(2πi/N)]T on the unit circle ℳ = {(a, b)|a2 + b2 = 1} ∈ ℝ2. In Fig. 5(a), we illustrate the point clouds {z(i)}i∈𝒱 ∈ ℝN that result from WTM maps with thresholds of T ∈ {0.05, 0.2, 0.3, 0.45}, which correspond to the four regimes of contagion dynamics that are predicted by Eqs. (1) and (2) for α = 1/3. [See labels I–IV in Fig. 4(b).] To visualize the N-dimensional point clouds {z(i)}i∈𝒱, we use principle component analysis (PCA) to project onto ℝ2 [22, 26, 57]. The color of each node at location w(i) and point z(i) reflects the activation time for node i during one realization of the WTM contagion that we use to generate the WTM map. In particular, dark blue nodes (points) indicate the contagion seed under cluster seeding. Gray nodes (points) never adopt the contagion and thus have activation times that are infinite. For practical purposes, we set these activation times to be 2N rather than ∞. (See Sec. III C for additional discussion.) Regime III is the regime for which the point cloud {z(i)} appears to best resemble (up to rotation) the nodes’ intrinsic locations {w(i)}. This is expected, as this regime corresponds to WFP and no ANC. (In other words, the contagion follows the network’s underlying manifold ℳ.)

FIG. 5. Contagion maps applied to noisy ring lattices.

Symmetric WTM maps were applied to a noisy ring lattice with N = 200 and (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2). (a) We show point clouds {z(i)} ∈ ℝN for WTM maps with T ∈ {0.05, 0.2, 0.3, 0.45}, which correspond, respectively, to regimes I–IV in Fig. 4(b). For visualization purposes, we show two-dimensional projections of the N-dimensional point clouds after applying principle component analysis (PCA) [26, 57]. (b) We show one realization of the contagion that we used to construct the WTM maps in panel (a). The color of each point in panel (a)—and corresponding node in panel (b)—indicates the node’s activation time. Nodes in the contagion seed are dark blue, and nodes that never adopt the contagion are gray. (c) As we discuss in the text, we analyze point clouds that result from WTM maps with respect to three criteria: geometry through a Pearson correlation coefficient ρ; dimensionality through the embedding dimension P; and topology through the difference Δ of lifetimes. (See the main text as well as the Methods section.) The vertical dashed lines in panel (c) indicate the predicted bifurcations in contagion dynamics from Eqs. (1) and (2) [see Fig. 4(b)]. Note that there are activation times that are infinite for [shaded region in (c)]. As expected for regime III, ρ ≈ 1, P ≈ 2, and large Δ indicate that the geometry, dimensionality and topology of the point cloud recover those of a ring manifold ℳ. See Secs. III D, III E, and III F as well as Supplementary Note 7 for discussions of these approaches for analyzing point clouds.

In Fig. 5(c), we summarize the characteristics of WTM maps for different thresholds T ∈ [0, 0.6]. For each threshold, we analyze manifold structure in a point cloud by studying geometry through a Pearson correlation coefficient ρ; dimensionality through an approximate embedding dimension P; and topology through Δ, which denotes the difference in lifetimes for the two most persistent 1-cycles in a Vietoris-Rips filtration [47, 48]. Large values of Δ indicate the presence of a single dominant 1-cycle (i.e., a ring) in a point cloud. See Secs. III D, III E, and III F as well as Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Figs. 11–13 for additional discussion of our analysis of point clouds.

As expected by our analysis, for regime III (which exhibits WFP but no ANC), we identify characteristics of the manifold ℳ in the point clouds that result from WTM maps. Namely, for regime III, the point cloud has similar geometry (i.e., indicated by large ρ), embedding dimension (i.e., indicated by P = 2), and topology (i.e., indicated by large Δ) as the network’s underlying manifold ℳ (i.e., a ring).

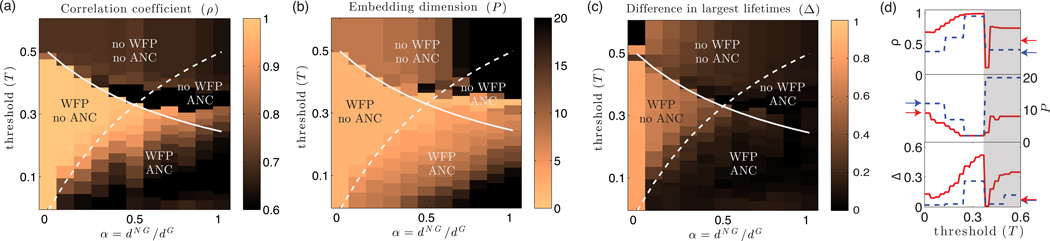

In Fig. 6, we analyze WTM maps applied to noisy ring lattices for various values of α = d(NG)/d(G). Specifically, we show values for ρ, P, and Δ for N = 200, d(G) = 20, various T, and various d(NG). We show using the solid and dashed curves, respectively, that the transitions between the qualitatively different regions of these properties closely resemble the bifurcation structure from Eqs. (1) and (2) with k = 0. In particular, there is WFP but no ANC, we are able to consistently identify the geometry, embedding dimension, and topology of the underlying manifold of the noisy ring lattice using the WTM map. When there is both WFP and ANC, the extent to which a contagion adheres to the network’s underlying manifold depends on α and T, and we can quantify this extent using the point-cloud measures ρ, P, and Δ. We illustrate our observations further in Fig. 6(d) by fixing α = 1/3 and plotting ρ, P, and Δ as a function of the threshold T. We show results for (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2) (blue dashed curves) and (d(G), d(NG)) = (24, 8) (red solid curves). Observe that the latter curve is smoother than the former one. The latter curve yields values of ρ, P, and Δ that better reflect the underlying ring manifold ℳ. By contrast, increasing the number N of nodes increases the contrast (i.e., as observed through ρ, P, and Δ) between the region that predominantly exhibits WFP and the other regions.

FIG. 6. Analyzing manifold structure in contagion maps.

We analyze the point clouds of WTM maps for various thresholds T for noisy ring lattices with N = 200 and various ratios α = d(NG)/d(G). (As an example, we show results for d(G) = 20 and various values of d(NG).) For each point cloud, we study (a) geometry through ρ, (b) dimensionality through P, and (c) topology through Δ (see the text and the Methods section). The transitions between qualitatively different structures in the WTM maps (i.e., as seen through ρ, P, and Δ) closely resemble the bifurcation structure from Eqs. (1) and (2), which we show for k = 0 using solid and dashed curves, respectively. In panel (d), we fix α = 1/3 and plot ρ, P, and Δ as a function of threshold T. We show results for (d(G), d(NG)) = (6, 2) (blue dashed curves) and (24, 8) (red solid curves). Note that there are activation times that are infinite for [shaded region in (d)]. The arrows indicate the ρ, P, and Δ values that we obtain for the embedding of nodes based on shortest paths, which (as we discuss in the text) one can construe as a variant of the dimension-reduction algorithm Isomap [22].

To give some perspective on the performance of WTM maps for identifying a noisy geometric network’s underlying manifold even in the presence of many non-geometric edges, we use the arrows in Fig. 6(d) to indicate the values of ρ, P, and Δ for a mapping of nodes based on shortest paths, which one can construe as a variant of the dimension-reduction algorithm Isomap [22] (which we apply to an unweighted network rather than to a point cloud). Specifically, we map 𝒱sto{x̃(i)} with T = 0 (as we discussed in the section “WTM Maps”).

In Supplementary Note 8, we describe additional numerical results that compare a WTM map to Isomap [22] and a Laplacian eigenmap [23] for generalizations of the noisy ring lattice by (1) allowing the node locations to be a random sampling of points on the unit circle and (2) allowing heterogeneity in their geometric and non-geometric degrees. We define these other network structures in Supplementary Note 2. Our results (see Supplementary Figs. 14–21) reveal large parameter regimes in which the ring manifold that underlies the noisy ring lattice is much more apparent (i.e., as indicated by large ρ, small P, and large Δ) for maps based on WTM contagions versus those based on shortest-path or diffusion dynamics (i.e., as in the Laplacian eigenmap). We stress that any applications of dimension reduction (e.g., manifold learning) in networks should use an approach that is appropriate for the question of interest. This is why we use contagions in this paper instead of other types of spreading dynamics.

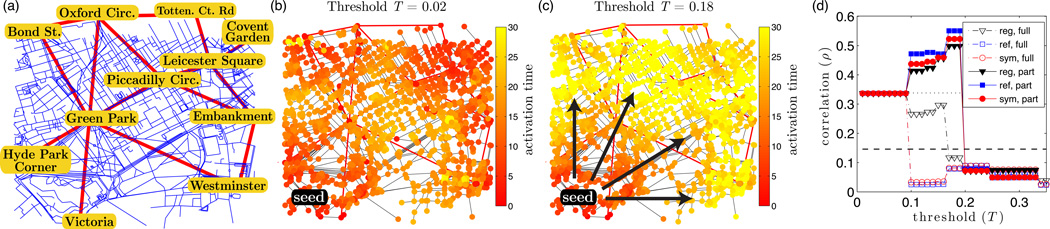

F. Contagions on a London Transit Network

In addition to synthetic networks, we study WTM maps for a London transit network [see Fig. 7(a)]. Nodes in the network represent intersections of known latitude and longitude (their coordinates are {w(i)}), geometric edges represent roads (from data used in Ref. [58]), and non-geometric edges represent metropolitan lines (from data used in Ref. [59]). We have made the network publicly available (see Sec. III A). We present our results in detail in Supplementary Note 1, and we summarize them here.

FIG. 7. Complex contagions on a London transit system.

(a) London transit network with N = 2217 nodes (i.e., intersections), 2854 roads [58] (which we interpret as geometric edges), and 15 metropolitan lines [59] (which we interpret as non-geometric edges). (b) Node activation times for a WTM contagion initialized with cluster seeding illustrate for small T that contagions quickly spread by skipping across the metro lines; this leads to ANC. (c) In contrast, for moderate T, the contagion spreads via slow WFP. (d) Although not all contagions exhibit such extreme sensitivity to T (see Supplementary Note 5), the dependence of ANC and WFP on T is captured by the geometry of WTM maps if one appropriately handles the activation times that are infinite (i.e., nodes that never adopt the contagion). See the discussion in the text. The curves with symbols indicate the values of ρ for WTM maps (curves with symbols), and the horizontal dotted and dashed lines, respectively, indicate ρ for the mapping of nodes based on shortest-path distances (i.e., as in the Isomap algorithm [22]) and a 2D Laplacian eigenmap [23].

Our central finding is that the qualitative dynamical regimes that we observe for synthetic noisy geometric networks also occur in the London transit network. More specifically, we observe both WFP and ANC. Additionally, as we illustrate in Fig. 7(b)–(c), these phenomena can be very sensitive to the WTM threshold T. We study WFP and ANC by examining the geometry of WTM maps. However, we do not study their one-dimensional homology, as computations of homology (which remains a very active area of research [60, 61]) have a much higher computational cost than our calculations of geometry and dimensionality.

In Fig. 7(d), we plot the Pearson correlation coefficient ρ that compares the distance between mapped nodes to their actual distance from each other (according to latitude and longitude) for various values of T. We show results for the regular, reflected, and symmetric versions of a WTM map (curves with symbols); and the horizontal dotted and dashed lines, respectively, give ρ for the mapping of nodes based on shortest-path distances (i.e., as in the Isomap algorithm [22]) and a 2D Laplacian eigenmap [23]. For each type of WTM map, we handle the activation times that are infinite (see Sec. III C) using two methods. In the method that we label “full,” we keep the entire matrix that encodes activation times, and we set the activation times that are infinite to be 2N. (Recall that we used this approach when studying WTM maps for synthetic networks.) In the method that we label “part,” we neglect contagions that do not saturate a network, so we use only a portion of the values in the matrix that encode activation times. In Fig. 7(d), we see that these choices give contrasting results. For the “full” option, activation times of infinity (which arise when T ⪆ 0.1) distort the WTM map and lead to a drop in ρ. In contrast, the “part” method neglects activation times of infinity, and we find that there is a range of T values for which there is a pronounced increase in ρ. Such improved agreement between the geometry of WTM contagions and the transit network’s inherent latitudinal and longitudinal embedding on Earth’s surface is characteristic of an increase in WFP versus ANC. Interestingly, we find that the small node degrees (e.g., 〈di〉 ≈ 2.59) and the significant heterogeneity (e.g., with respect to node locations, node degrees, and the length of roads) in the London transit network causes WFP and ANC to be extremely sensitive to the value of T for only a few of the contagion seeds S(j) (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Nevertheless, as we have demonstrated, such minority cases still have a significant effect on WTM maps.

Our numerical experiments for the London transit network highlight additional complexities that can arise for networks that are constructed from empirical data, and they offer complementary insights to our investigation of synthetic networks. In particular, the synthetic networks that we examine either are homogeneous or are only slightly heterogeneous, so the WFP and ANC behavior tends to be similar for contagions that are initialized in different parts of a network. This is not the case for the London transit network, which has significant heterogeneity and very small node degrees (which seems to exacerbate the effect of heterogeneity). Infections that start in some parts of the network have rather different properties than those than start in others, and one also needs to consider multiple strategies for how to handle activation times of infinity. There are also other interesting phenomena that our approach can examine for heterogeneous networks. For example, in Supplementary Note 1, we study the geometry ofWTM contagions for individual nodes (rather than averaging our results over an entire network) in what amounts to an “egocentric” analysis of geometry. We find that the local geometry of WTM maps (and hence of contagions) at a given node relates strongly to its proximity to a metro line.

II. DISCUSSION

Many empirical networks include a combination of geometric edges between nearby nodes and non-geometric, longrange edges [12]. Such situations can arise when nodes are restricted by their locations in a physical space (such as in a city) or in terms of latent underlying spaces [16–26]. When considering a spreading process on a noisy geometric network, it is important to understand the extent to which a contagion follows such underlying structure. To address this question, we conducted a detailed investigation using the Watts threshold model (WTM) of complex contagions (with uniform threshold T) on noisy geometric networks. The spreading dynamics exhibit both wavefront propagation (WFP) that follows the underlying manifold structure of a network as well as the appearance of new clusters (ANC) of contagions in distant locations. To investigate the extent to which a WTM contagion adheres to a network’s underlying manifold, we introduced the notion of WTM maps (and contagion maps more generally) and showed when a contagion predominantly spreads via WFP that WTM maps recover the topology, geometry, and dimensionality of a network’s underlying manifold even in the presence of many non-geometric (i.e., “noisy”) edges.

Our methodology of constructing and analyzing contagion maps has important implications not only for the analysis, modeling, and control of contagions, but also for other dynamics that can be used to construct filtrations of networks. Moreover, by studying manifold structure in contagion maps, we have shown that such maps can also be used to identify and study manifold structure in networks. We have compared WTM maps to Laplacian eigenmaps [23] and Isomaps [22] (see Supplementary Note 8 for additional discussion) and found that WTM maps—which are based on a nonlinear and nonconservative dynamical process—yield results that contrast with those from the other methods. This is sensible, as nonconservative and conservative dynamics (e.g., diffusion) are known to give different results for which nodes are central [65] and what network structures constitute bottlenecks to the dynamics [66].

In the Supplementary Discussion, we further consider the implications of our work on three important fields of research: (i) studying contagions and other dynamics from the perspective of high-dimensional data analysis (i.e., computational topology and nonlinear dimension reduction), (ii) identifying low-dimensional (e.g., manifold) structure in networks, (iii) identifying low-dimensional (e.g., manifold) structure in point-cloud data.

III. METHODS

A. Data and Code Availability

The London transit network that we study in Sec. I F and the code that we use to construct WTM maps are available as Supplementary Files 1 and 2.

B. Bifurcation Analysis

To guide our study of WTM maps, we set Ti = T for each node i ∈ 𝒱, and we perform a bifurcation analysis of WTM contagions on noisy ring lattices. In particular, we investigate the dependence of ANC and WFP on the contagion threshold T and on the network parameters d(G), d(NG), and N. In Fig. 3, we illustrate ANC and WFP for this class of networks with d(G) = 4, d(NG) = 1, and N = 40 by considering a WTM contagion at time t = 0. The light blue nodes are in the contagion seed S = s ⋃ {k|Ask ≠ 0}, which is centered at node s ∈ 𝒱. Because node s is incident to both geometric and non-geometric edges, the contagion is initialized with 1+ d(NG) = 2 contagion clusters. We denote these clusters by C1 and C2. Cluster C1 is more likely to grow via WFP than C2. The orange nodes in Fig. 3 are what we call contagion cluster C1’s “boundary”—the set of nodes that have yet to adopt the contagion but which are exposed to it via a geometric edge that is incident to an infected node in C1. As we show in the magnification on the right, nodes in the boundary can adopt the contagion via WFP. Nodes that are not infected and not on the boundary can become infected via ANC. (See the dark blue nodes and dashed edges.)

If node i adopts a contagion via ANC, then by definition it is not in the boundary of a contagion cluster, so its neighbors due to geometric edges have yet to adopt the contagion. Consequently, node i potentially has 0, 1, …, d(NG) neighbors that are infected, and its fraction of infected neighbors is restricted to , This observation yields the critical thresholds

The contagion dynamics changes abruptly at the critical values of T, so the qualitative dynamics of ANC for any are similar to each other, but there are abrupt changes at the endpoints of the interval. In particular, whenever , a node requires at least (d(NG) − k) neighbors due to non-geometric edges to be infected before it adopts the contagion. In Supplementary Note 6, we study the probability that a node has exactly (d(NG) −k) infected non-geometric neighbors at time t. For large networks, this probability is approximately , where q(t) denotes the number of nodes that have adopted the contagion at or before time t. Note that the probability is an expectation over the ensemble of noisy ring lattices, because it uses the fact that non-geometric edges are generated uniformly at random in our model. Therefore, it does not matter which of the q(t) nodes happen to be infected.

Turning to WFP, we now study contagion transmissions exclusively across geometric edges. That is, given a node i in a contagion cluster’s boundary, we assume that the node’s neighbors due to non-geometric edges are not infected. Naturally, this assumption does not always hold, but it is insightful to first examine this ideal case and then consider more general situations as perturbations of such a baseline analysis of WFP.

To facilitate our discussion, we will use the example contagion illustrated in Fig. 3. In particular, we consider WFP in the clockwise direction for cluster C1. Nodes a, b, and c are exposed, respectively, to 2, 1, and 0 nodes that have adopted the contagion, so their fractions of neighbors that are infected are fa = 2/5, fb = 1/5, and fc = 0/5. Note that we assume that the non-geometric edges for nodes a, b, and c are incident to nodes that are not infected (i.e., which have not adopted the contagion). Because fi > T for node i to adopt the contagion, one of three situations can occur at time t = 1: (1) if 0 ≤ T < 1/5, then nodes a and b adopt the contagion; (2) if 1/5 ≤ T < 2/5, then node a adopts the contagion; and (3) if 2/5 ≤ T, then the contagion cluster C1 does not increase in size via WFP. Node c cannot adopt the contagion via WFP at time t = 1 for any T ≥ 0. We find that WFP is governed by the critical thresholds

where a wavefront propagates at a speed of k + 1 nodes per time step for . For , there is no WFP.

We now include additional discussion of the assumptions in our analysis of WFP. Specifically, when considering whether or not node i in a contagion cluster’s boundary will become infected, we assumed that its non-geometric edges are not incident to an infected node. Obviously, this assumption is valid for d(NG) = 0. However, as we discuss in Supplementary Note 6, the expected probability (over an ensemble of noisy geometric networks with non-geometric edges generated uniformly at random) that a node’s non-geometric edge is incident to an infected node is q(t)=(N − 1). Similarly, the probability that a node has d(NG) non-geometric neighbors and that none of them are infected is approximately [1 − q(t)/N]d(NG), which is therefore the probability that our assumption is valid. In particular, whenever q(t) ≪ N, which necessarily requires N ≫ 1 and describes the scenario of an early stage of a contagion on a large network, the probability that our assumption is valid is approximately equal to 1. Therefore, Eq. (2) accurately describes the speed of WFP in this scenario with high probability. (Note that we also assume that d(NG) ≪ N, so there cannot be too many non-geometric edges.)

Equation (2), which one can construe as a “local” result, is also very useful for predicting the “global” behavior of WFP. To see this, we make the following two observations: (1) If a contagion cannot spread when q(t) ≪ N, then it will not reach a state in which q(t) = 𝒪(N); and (2) if q(t) does spread for q(t) ≪ N, then it will also spread when q(t) = 𝒪(N) because an increase in q(t) will help promote further spreading. Specifically, the presence of a node in the boundary with infected non-geometric neighbors can accelerate WFP by allowing the node to adopt the contagion with fewer infected geometric neighbors than Eq. (2) would predict. In fact, when the contagion size is large [i.e., when q(t) ≈ N], we find that the WFP speed accelerates up to d(G)/2 nodes per time step (i.e., all nodes in the boundary on one side of the contagion cluster become infected upon each time step). Similar accelerated WFP has also been observed for other applications including species dispersion [67]. See Supplementary Note 6 for further discussion.

In Supplementary Note 3, we use a perturbative approach to generalize our bifurcation analysis to a family of synthetic noisy geometric networks with slight heterogeneities. In our generalizations, we examine the WFP and ANC behavior of WTM contagions at each node. When the nodes are identical (i.e., as in the synthetic ring lattice), the contagion behavior is uniform across a network; this leads to the bifurcation diagram in Fig. 4. When there is heterogeneity, the contagion behavior at each node varies across a network. However, if the amount of heterogeneity is small, then one can construct a perturbed bifurcation diagram in which the boundaries between contagion regimes are thickened. That is, as one varies T or α, the transition from one regime (e.g., WFP and no ANC) to another (e.g., WFP and ANC) still occurs, but it does not occur simultaneously for each node.

C. Activation Times of Infinity in WTM Maps

When studying WTM maps, one needs a strategy for dealing with activation times that are infinite (which in some cases might be useful for identifying outliers and in other cases might be problematic). After constructing a map such as 𝒱sto{x(i)} ∈ ℝJ, the distance between points x(i) and x(j) for i, j ∈ 𝒱 can be infinite or even undefined, which complicates any subsequent analyses of the point cloud {x(i)}. Such an issue can also arise for distances that are derived from shortest paths or the commute time for diffusion, so algorithms for mapping networks often assume that a network consists of a single connected component [22, 23]. Distances that are infinite are not an issue for diffusion maps [24], because the nodes are mapped to a bounded metric space whose diameter is equal to twice the maximum of the heat kernel.

For complex contagions, activation times that are infinite arise not only due to disconnected networks, but also for networks that are “disconnected” with respect to the contagion dynamics. In the present work, we use two methods for handling activation times that are infinite: we either set these activation times to be large but finite (i.e., to be 2N ≪ ∞), or we neglect the contagions that lead to activation times that are infinite by restricting the map to a subset of contagions (i.e., j ∈ 𝒥′ ⊂ 𝒥, where ). We note in passing (though we do not explore the strategy in the present manuscript) that there exist maps such as dstod/(d+1) ∈ [0, 1] that map an unbounded metric space to a topologically-equivalent metric space that is bounded. This ought to be useful for some situations.

D. Geometry of WTM Maps

To quantify the similarity of the geometry of a WTM map to that of the nodes on the underlying manifold of a noisy geometric network, we calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient ρ to relate node-to-node distances for the WTM map. In Fig. 5, we compare the geometry of {z(i)} [see panel (a)] to that of the nodes’ locations {w(i)} ∈ ℳ [see panel (b)] by computing a Pearson correlation coefficient ρ to compare the node-to-node distances for the two point clouds (i.e., ‖z(i) − z(j)‖2 and ‖w(i) − w(j)‖2 for (i, j) ∈ 𝒱 × 𝒱). We conduct our comparison with respect to the dimension of the ambient spaces in which the points lie (i.e., ℝN for {z(i)} and ℝ2 for {w(i)}). See Supplementary Note 7 for further discussion.

E. Dimensionality of WTM Maps

We study the dimensionality by examining the residual variance [22, 57] of the point cloud {z(i)} and computing the smallest dimension such that we lose less than 5% of the variance when projecting to a lower dimension using PCA [22, 26, 57]. We refer to this dimension as the “embedding dimension” P. Specifically, we estimate the embedding dimension P of a WTM map by studying p-dimensional projections of the WTM map obtained via PCA for different values of p ∈ {1, 2, … }. For each projection, we calculate the residual variance Rp = 1 − (ρ(p))2 [22, 57], where ρ(p) denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient that relates the geometric similarity between the p-dimensional projection and the unprojected WTM map (see Sec. III D). We define the embedding dimension P as the smallest dimension p such that Rp < 0.05. See Supplementary Note 7 for further discussion.

F. Topology of WTM Maps

We study the topology of a WTM map by examining the persistence diagram of a Vietoris-Rips filtration that is generated by the point cloud {z(i)} [47, 48]. For our experiments involving a noisy ring lattice, we are interested primarily in assessing the presence versus absence of a ring topology in a WTM map. We thus study the persistent homology of a WTM map by examining a Vietoris-Rips filtration using the software package Perseus [68]. We calculate persistent 1D features (i.e., 1-cycles) for the point cloud and record the difference Δ = l1 − l2 between the two largest lifetimes of such 1D features. We normalize all lifetimes by the diameter of the point cloud so that Δ, l1, l2 ∈ [0,1]. (Note that sometimes it can be preferable to use the “bottleneck distance” between persistence diagrams [69] rather than Δ.) See Supplementary Note 7 for further discussion.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DT and PJM were partially supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD075712. DT was also funded by the National Science Foundation under Grant DMS-1127914 to the Statistical and Applied Mathematical Sciences Institute (SAMSI). DT also acknowledges an Institute of Mathematics and its Applications (IMA) travel grant to attend the workshop Topology and Geometry of Networks and Discrete Metric Spaces. MAP was supported by the European Commission FET-Proactive project PLEXMATH (Grant No. 317614) and also acknowledges a grant (EP/J001759/1) from the EPSRC. FK’s stay in Oxford was supported in part by the latter grant. HAH gratefully acknowledges funding from EPSRC Fellowship EP/K041096/1, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) KUK-C1-013-04, a SAMSI Low-Dimensional Structure in High-Dimensional Data workshop travel grant, and an AMS Simons travel grant. KM and MK were partially supported by NSF grants NSF-DMS-0915019, 1125174, 1248071, and contracts from AFOSR and DARPA. We thank Yannis Kevrekidis and Barbara Mahler for discussions and numerous helpful comments on a version of this manuscript. We thank James Gleeson, Ezra Miller, Sayan Mukherjee, and Hal Schenck for helpful discussions. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS All authors designed the research and wrote the text. DT and FK developed the analytical results and conducted the numerical experiments.

FINANCIAL INTEREST STATEMENT The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Barrat A, Barthelemy M, Vespignani A. Dynamical Processes on Complex Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easley D, Kleinberg JM. Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mollison D. Spatial contact models for ecological and epidemic spread. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B. 1977;39:283–326. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter MA, Gleeson JP. Dynamical systems on networks: A tutorial. 2014 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.7663. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastor-Satorras R, Castellano C, Van Miegham P, Vespignani A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. 2014 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1408.2701. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockmann D, Helbing D. The hidden geometry of complex, network-driven contagion phenomena. Science. 2013;342:1337–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.1245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colizza V, Barrat A, Barthelemy M, Vespignani A. The role of the airline transportation network in the prediction and predictability of global epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(7):2015–2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510525103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hufnagel L, Brockmann D, Geisel T. Forecast and control of epidemics in a globalized world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308344101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedstrom P. Contagious collectivities: On the spatial diffusion of Swedish trade unions, 1890–1940. Amer. J. Sociol. 1994;99:5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th Edition. Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong EK, Estep D, Hannig J. Continuum modeling of large networks. Intl. J. of Num. Mod.: Elec. Nets. Dev. Fields. 2008;21(3):169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barthelemy M. Spatial networks. Phys. Rep. 2011;499(1):1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liben-Nowell D, Kleinberg J. The link-prediction problem for social networks. J. Amer. Soc. Info. Sci. Tech. 2007;58(7):1019–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clauset A, Moore C, Newman MEJ. Hierarchical structure and the prediction of missing links in networks. Nature. 2008;453(7191):98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature06830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guimerá R, Sales-Pardo M. Missing and spurious interactions and the reconstruction of complex networks. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2009;106(52):22073–22078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908366106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano MA, Boguñá M, Sagueès F. Uncovering the hidden geometry behind metabolic networks. Mol. BioSys. 2012;8:843–850. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05306c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.M Boguñá M, Papadopoulos F, Krioukov D. Sustaining the Internet with hyperbolic mapping. Nature Comms. 2010;1:62. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrano MA, Krioukov D, Boguñá M. Self-similarity of complex networks and hidden metric spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100(7):078701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.078701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoff PD, Raftery AE, Handcock MS. Latent space approaches to social network analysis. J. Amer. Stat. Assoc. 2002;97(460):1090–1098. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer A, Zhao Z, Shkolnisky Y, Hadani R. Viewing angle classification of cryo-electron microscopy images using eigenvectors. SIAM. J. Imag. Sci. 2011;4(2):723–759. doi: 10.1137/090778390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer A, Wu H-T. Two-dimensional tomography from noisy projections taken at unknown random directions. SIAM J. Imag. Sci. 2013;6(1):136–175. doi: 10.1137/090764657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenenbaum JB, de Silva V, Langford JC. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science. 2000;290:2319–2323. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belkin M, Niyogi P. Laplacian eigenmaps for dimensionality reduction and data representation. Neural Comp. 2003;15(6):1373–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coifman RR, et al. Geometric diffusions as a tool for harmonic analysis and structure definition of data: Diffusion maps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(21):7426–7431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500334102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerber S, Tasdizen T, Whitaker R. Robust non-linear dimensionality reduction using successive 1-dimensional Laplacian eigenmaps; Proc. 24th Intern. Conf. Mach. Learn; 2007. pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorzano COS, Vargas J, Montano AP. A survey of dimensionality reduction techniques. 2014 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.2877. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lafon S, Lee AB. Diffusion maps and coarse-graining: A unified framework for dimensionality reduction, graph partitioning, and data set parameterization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intel. 2006;28(9):1393–1403. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2006.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kivelä M, et al. Multilayer networks. J. Cplx. Net. 2014;2:203–271. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter MA. Small-world network. Scholarpedia. 2012;7(2):1739. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman MEJ. Models of the small world. J. Stat. Phys. 2000;101:819–841. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinberg JM. Navigation in a small world. Nature. 2000;406:845. doi: 10.1038/35022643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monasson R. Diffusion, localization and dispersion relations on “small-world” lattices. The Euro. J. Phys. B. 1999;12:555. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noble JV. Geographic and temporal development of plagues. Nature. 1974;250:726–729. doi: 10.1038/250726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marvel SA, Martin T, Doering CR, Lusseau D, Newman MEJ. The small-world effect is a modern phenomenon. 2013 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1310.2636. [Google Scholar]

- 36.He D, Lui R, Tse CK, Lin X, Stone L. Global spatio-temporal patterns of influenza in the post-pandemic era. 2014 doi: 10.1038/srep11013. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1407.5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centola D. The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science. 2010;329:1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1185231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centola D, Macy M. Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties. Amer. J. Sociol. 2007;113(3):702–734. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centola D, Eguíluz VM, Macy M. Cascade dynamics of complex propagation. Physica A. 2007;374(1):449–456. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghasemiesfeh G, Ebrahimi R, Gao J. Complex contagion and the weakness of long ties in social networks: Revisited. In; Proc. Fourteenth ACM Conf. Elec. Commerce; 2013. pp. 507–524. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kempe D, Kleinberg J, Tardos E. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network; Proc. Ninth ACM SIGKDD Inter. Conf. Knowl. Disc. Data Min; 2003. pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. Immunization of complex networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;65(3):036104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.036104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes CJ, Anderson RM. Epidemic thresholds and vaccination in a lattice model of disease spread. Theor. Pop. Bio. 1997;52(2):101–118. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.1997.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watts DJ. A simple model of global cascades on random networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(9):5766–5771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082090499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aizenman M, Lebowitz J. Metastability Effects in Bootstrap Percolation. J. Phys. A. 1988;21:3801–3813. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Granovetter M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Amer. J. Sociol. 1978;83(6):1420–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaczynski T, Mischaikow K, Mrozek M. Computational Homology, Applied Mathematical Sciences 157. Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edelsbrunner H, Harer J. Computational Topology: An Introduction. American Mathematical Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petri G, Scolamiero M, Donato I, Vaccarino F. Networks and Cycles: A Persistent Homology Approach to Complex Networks; In Proc. Euro. Conf. Cplx. Sys; 2012. pp. 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petri G, Scolamiero M, Donato I, Vaccarino F. Topological strata of weighted complex networks. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e66506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kahle M. Topology of random simplicial complexes: A survey. 2013 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1301.7165. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bobrowski O, Kahle M. Topology of random geometric complexes: A survey. 2014 Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.4734. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlsson G, et al. Topological data analysis and machine learning theory. Tech. Rep. 12w5081, Banff Inter. Res. Station Math. Innov. Disc. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doyle PG, Snell JL. Random Walks and Electric Networks. Mathematical Association of America; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radl A, Luxburg UV, Hein M. The resistance distance is meaningless for large random geometric graphs. Proc. Workshop on Analyzing Networks and Learning with Graphs. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gleeson JP, Cahalane DJ. Seed size strongly affects cascades on random networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;75(5):056103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.056103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cox TF, Cox MA. Multidimensional Scaling. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee SH, Holme P. Exploring maps with greedy navigators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:128701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.128701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rombach MP, Porter MA, Fowler JH, Mucha PJ. Core-periphery structure in networks. SIAM. J. Appl. Math. 2014;74:167–190. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bauer U, Kerber M, Reininghaus J. Clear and compress: Computing persistent homology in chunks. Topo. Methods in Data Analys. and Vis. III. 2014:103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vejdemo-Johansson M. Sketches of a platypus: Persistent homology and its algebraic foundations. Algeb. Topo.: App. and New Directions. 2014:295–320. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gleeson JP. Binary-state dynamics on complex networks: Pair approximation and beyond. Phys. Rev. X. 2013;3:021004. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Melnik S, Ward JA, Gleeson JP, Porter MA. Multi-stage complex contagions. Chaos. 2013;23:013124. doi: 10.1063/1.4790836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jeub LGS, Balachandran P, Porter MA, Mucha PJ, Mahoney MW. Think locally, act locally: Detection of small, medium-sized, and large communities in large networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2015;91:012821. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.012821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ghosh R, Lerman K. Rethinking centrality: The role of dynamical processes in social network analysis. Disc. Cont. Dyn. Sys. Ser. B. 2014;19(5):1355–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lerman K, Ghosh R. Network structure, topology, and dynamics in generalized models of synchronization. Phys. Rev. E. 2012;86:026108. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.026108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hallatscheka O, Fisher DS. Acceleration of evolutionary spread by long-range dispersal. Proc. Natl. Acad. of Sci. USA. 2014;111(46):E4911–E4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404663111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mischaikow K, Nanda V. Morse theory for filtrations and efficient computation of persistent homology. Discr. and Comp. Geo. 2013;50(2):330–353. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kramár M, Goullet A, Kondic L, Mischaikow K. Quantifying force networks in particulate systems. Physica D. 2014;283:37–55. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The London transit network that we study in Sec. I F and the code that we use to construct WTM maps are available as Supplementary Files 1 and 2.