Abstract

MRL/MpJ-Faslpr (MRL-lpr) and New Zealand Black/White (NZB/W) mice develop spontaneous autoimmune disease characterized by autoantibody production and glomerulonephritis that progresses in parallel with increasing systemic nitric oxide (NO) production. A pre-viously published study from our laboratory indicated that oral administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMMA) before the onset of clinical disease significantly decreased renal and joint pathology in MRL-lpr mice. To characterize the effect of late modulation of NO production in murine SLE, we administered oral NMMA and/or restricted dietary arginine after disease onset in two murine models of SLE. When receiving combined NMMA and arginine restriction, MRL-lpr mice had reduced joint pathology scores and NZB/W mice had lower renal pathology scores than control mice. These results indicate that modulating NO production after the onset of disease diminishes disease severity in two models of SLE, although not as effectively as treating before disease onset.

INTRODUCTION

Nitric oxide (NO) is a soluble intercellular messenger that is formed by the deamination of the amino acid L-arginine by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) to form NO and L-citrulline. NO’s many biologic functions include relaxation of smooth muscle, neurotransmission, antitumor and anti-microbial activities, differentiation of hematopoietic cells, and enhancing inflammation (1–3). In rodents, NO is produced in macrophages, activated neutrophils, lymphocytes, mast cells, and Kupffer cells by inducible NOS (NOS2) (4). NO produced during an immune response is proinflammatory and anti-microbial via several mechanisms. First, NO itself is cytotoxic through its ability to bind and deplete intracellular iron and inactivate cellular enzymes in target cells (2, 5). Second, it can react with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which can either be metabolized to nitrite or form highly reactive hydroxyl and nitrogen dioxides, the latter of which is directly toxic to cells. Peroxynitrite affects cellular function through nitrosylation of proteins. For example, when catalase is nitrosylated, cells are more susceptible to injury from free radicals (6). Third, NO can modulate inflammatory responses by inhibiting the production of interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-2 by Th1 cells (7–9).

Several human studies have examined the role of NO in autoimmunity and inflammation. Patients with SLE have elevated serum measures of NO production (10, 11). Renal biopsy specimens from individuals with immune complex glomerulonephritis have enhanced immunostaining for NOS2 compared to those from controls (12). Measures of NO production are increased in the synoviocytes, synovial fluid, and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (13–15). These data suggest that NO is an inflammatory mediator in human autoimmune disease as well as murine disease.

Animal models of autoimmunity are useful reagents for defining the role of NO in disease. A number of studies demonstrated increased production of NO during spontaneous and induced autoimmune responses. NOS inhibitors such as NMMA reduced clinical disease activity in these animal models, confirming the role of NO in murine autoimmune diseases. NMMA reduced both adjuvant and strep cell wall arthritis in mice and rats respectively. In a rat model, NMMA reduced immune complex induced vascular and pulmonary injury. Inflammation in rat diabetes was reduced by administration of aminoguanidine, another NOS inhibitor (16). Restriction of dietary arginine, the substrate for NOS, reduced proteinuria and fibrosis associated with antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis in Sprague–Dawley rats (17).

MRL-lpr and NZB/W mice are useful murine models of SLE. Both strains produce autoantibodies and develop nephritis in the setting of reduced complement and overproduction of NO. In addition to glomerulonephritis, MRL-lpr mice also develop arthritis, vasculitis, and lymphoproliferation (18). We previously demonstrated that spontaneous immune complex glomerulonephritis and arthritis in MRL-lpr mice was significantly decreased by NMMA administration early in disease (19). These mice were given an arginine-free diet to prevent arginine from competitively inhibiting NMMA uptake in macrophages (20). Control MRL-lpr mice in these experiments, on the arginine-free diet, developed less pathologic disease than historical controls, suggesting dietary arginine restriction alone may alter disease expression (19).

These observations led us to test the following hypotheses: (i) NMMA reduces clinical and pathological signs of murine lupus when administered after the onset of disease. (ii) Restriction of dietary arginine modulates NO production and thus reduces autoimmune disease in MRL-lpr mice. (iii) NMMA therapy is more effective when combined with dietary arginine restriction. We evaluated the effects of NMMA after the onset of clinical disease by giving MRL-lpr mice NMMA beginning at 14–16 weeks of age while on either an arginine-restricted or standard rat chow diet. Controls were fed either standard rat chow or an arginine-free diet and distilled water. The NMMA-treated groups developed less arthritis and proteinuria than controls; differences between control and NMMA treatment were greatest in the mice receiving an arginine-free diet. NMMA treatment had no significant effect on pathologic glomerular scores whether the mice were on an arginine restricted diet or not. An arginine restricted diet alone did not alter the course of autoimmune disease in MRL-lpr mice despite reduced levels of NO production. Administration of NMMA after the onset of proteinuria in NZB/W mice reduced proteinuria and glomerular pathology scores. These data indicate that modulation of NO production after onset of disease can alter the progression of murine lupus.

METHODS

Mice

Female NZB/W and MRL-lpr mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at 4–5 weeks of age. All mice were housed in the animal research facility at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Durham, North Carolina, under pathogen-free conditions. All mice were negative by serological testing for common murine pathogens.

Mice were fed a nitrate/nitrite (N/N)-free diet (Zeigler Brothers, Gardners, PA); a N/N-free arginine-free diet where arginine was replaced on a weight basis by glutamate (Zeigler Brothers); or standard rat chow, depending on the experimental group. Mice were given distilled deionized water or NMMA ad libitum. Mice were placed in metabolic cages (2 or 3 per cage) for 24hr urine collections at several points before and during treatment (21). The urine specimens were collected in an antibiotic solution containing 25 μg/ml ampicillin, 50 μg/ml of gentamicin, and 200 μg/ml of chloramphenicol to prevent bacterial overgrowth.

Treatment Groups (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Treatment Groups

| Group No. |

Mouse strain |

Treatment | Age of therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MRL-lpr | NMMA alone | 14–20 weeks |

| 2 | MRL-lpr | NMMA + arginine restriction |

16–20 weeks |

| 3 | MRL-lpr | Arginine restriction alone | 8–18 weeks |

| 4 | NZB/W | NMMA + arginine restriction |

21–25 weeks |

NMMA was purchased from Cyclops Biochemical Corporation (Salt Lake City, UT). A 50 mM solution of NMMA was prepared in distilled water and filtered through a 0.2-μm filter (Costar) for ad libitum oral administration in glass bottles. On average, each mouse consumed 0.25 μmol of NMMA per day. Control mice were given distilled, deionized water. Group I was a pilot study consisting of 8 MRL-lpr mice. From 14 to 20 weeks of age, 3 were treated with NMMA, and 5 were given distilled water. All were fed a standard rat chow diet during this period. Group II consisted of 37 MRL-lpr mice. From 16 to 20 weeks of age, 18 were treated with NMMA, and 19 with distilled water while on a N/N-free, arginine-free diet. Group III consisted of 18 MRL-lpr mice. Nine were given an arginine-free, N/N-free diet, and 9 were given a N/N-free diet. The diet therapy was administered from 8 to 18 weeks of age. Group IV consisted of 20 NZB/W mice. From 21 to 25 weeks of age, 10 mice were given NMMA and 10 distilled water. All mice in this group were fed an arginine-free diet.

In Groups I, II, and IV, treatment was started when urinary protein in untreated mice exceeded three times the baseline level at age 6–8 weeks. Due to variability in the strains and between groups, therapy was started at Week 14 in Group I, Week 16 in Group II, and Week 21 in Group IV. Group III was started on diet therapy after obtaining the mice and allowing acclimation to the animal facility (i.e., 8 weeks of age).

Nitrate/Nitrite Assay

Urine samples were deproteinized by filtration through a 1000-NMWL filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Nitrate reductase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) was used to convert nitrate to nitrite, which was measured in either duplicate or triplicate using the Greiss reaction as described previously (22). A standard curve was devised using known concentrations of N/N. Total N/N excretion was calculated and expressed as μmol/mouse/day.

Protein Assay

Urine protein was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay and expressed as μg/mouse/day.

Anti-DNA Antibody ELISA

Serum anti-single stranded DNA and anti-double stranded DNA antibody titers were determined by ELISA as previously described (23). Calf thymus DNA (Sigma Chemical Corp., St. Louis, MO) was purified by repeated phenol extractions. Double-stranded DNA was derived by incubating DNA with S1 nuclease (Sigma). Single-stranded DNA was derived by boiling the DNA for 10 min and immediately immersing in ice.

The DNA preparations were coated on microtiter plates and incubated at 37°C for either 4 hr (for ssDNA) or 16 hr (for dsDNA). After the addition of serial dilutions of sera, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse g chain-specific antibody was added. Tetramethyl benzidine (TMB) with 0.015% H2O2 in 0.1 M citrate was used as the substrate. Absorbance at 380 nm was measured on a Molecular Dynamics plate reader.

Pathology

At the end of treatment, all mice were anesthetized and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Kidneys were imbedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before examination by a pathologist who was ‘‘blinded’’ to the treatment groups. Knee joints were decalcified in formic acid, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained before analysis. Renal and joint disease activity were graded as previously described (24). Briefly, glomeruli were graded for hypercellularity (0–4), hyperlobularity (0–4), crescent formation (0–4), and necrosis (0–4). Scores were additive, with normal BALB/c kidneys being scored from 0 to 1. Synovial tissue was scored by the amount of synovial proliferation (0–3) and subsynovial inflammation (0–3). Again, scores were additive, with normal BALB/c synovium receiving scores from 0 to 0.5.

Statistical Analysis

Data sets were analyzed using standard deviation and the two-tailed Mann–Whitney (Wilcoxon) U test to compare means and median rank sums between data from treatment and control mice. Some urine samples were pooled; therefore, standard deviation and P values could not be calculated for these samples.

RESULTS

Late Treatment of MRL-lpr Mice on Regular Diet with NMMA (Group I)

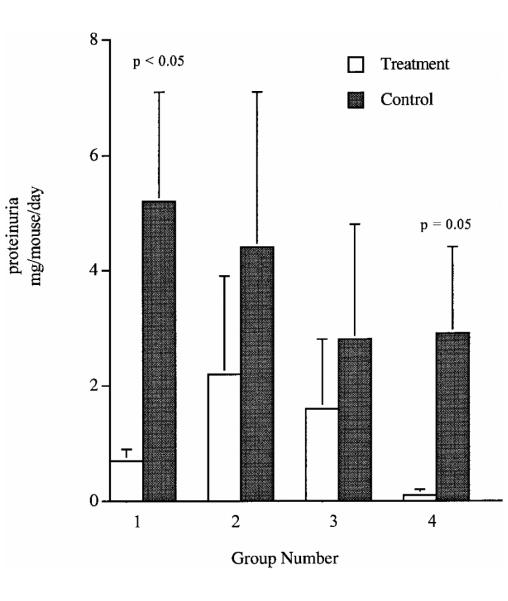

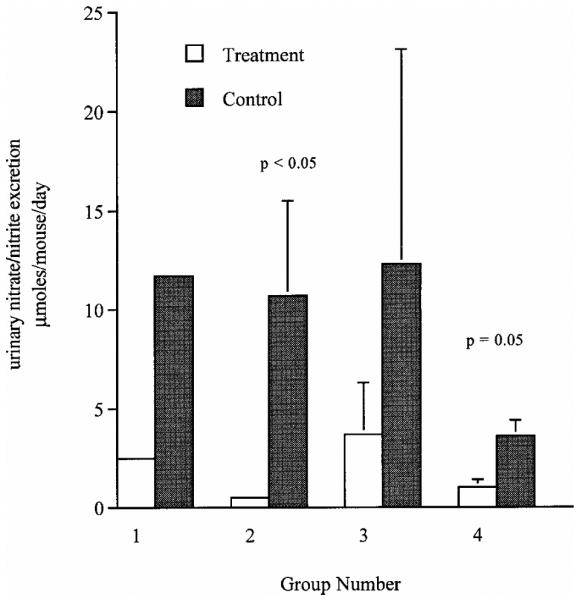

Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated that early treatment of MRL-lpr mice with NMMA and an arginine-free diet reduced glomerulonephritis and arthritis. In order to determine the effects of late administration of NMMA in this murine model, we administered 50 μm NMMA in drinking water for ad libitum consumption from the age of 14 to 20 weeks. The mice in the NMMA treatment group excreted less urinary N/N(2.5 μmoles vs 11.7 μmoles/mouse/day; Fig. 1) and had lower joint pathology scores than the untreated group (1.5 ± 1.3 vs 5.5 ± 1.2, P = 0.13; Table 2). Renal disease at 20 weeks of age as determined by proteinuria was reduced (0.7 ± 0.2 μg/mouse/day vs 5.2 ± 1.9 μg/mouse/day, P = 0.05; Fig. 2). Despite the significant decrease in proteinuria, glomerular scores demonstrated only a minor trend toward improvement in the treatment group (7.0 ± 2.5vs9.5 ± 3.3, P = 0.28; Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Effect of modulation of NO production on urinary nitrate/nitrite excretion of lupus-prone mice. Data presented are the mean ± standard deviation of the urinary excretion of nitrate and nitrite (in μmol/mouse/day) for all of the study groups. Groups are as described in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Pathology Scores of Kidney and Joint Specimens from All Groups

| Group No. |

Treatment | n | Renal score |

Joint score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NMMA | 3 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 |

| Control | 5 | 9.5 ± 3.3 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | |

| 2 | NMMA + dieta | 19 | 8.7 ± 3.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3* |

| Dieta | 18 | 9.2 ± 3.0 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | |

| 3 | Dieta | 9 | 9.4 ± 5.5 | 4.4 ± 3.2 |

| Control | 9 | 4.6 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 3.1 | |

| 4 | NMMA + dieta | 10 | 1.0 ± 0.7** | NA |

| Dieta | 10 | 4.4 ± 4.2 | NA |

Note. Data are given as means and standard deviations. Unless otherwise noted, P > 0.05 between treatment and control groups.

Diet, arginine-free, nitrate/nitrite-free diet.

P = 0.02 between the treatment and control groups.

P = 0.01 between the treatment and control groups.

FIG. 2.

Effect of modulation of NO production on proteinuria in murine models of lupus. The figure represents mean ± standard deviation of 24-hr urinary protein excretion (in μg/mouse/day) for all of the study groups. Groups are as described in Table 1.

Late Treatment of MRL-lpr with NMMA and an Arginine-Free Diet (Group II)

A larger group of mice was then treated with NMMA to confirm the trends in the first study. Because dietary arginine reduces the uptake of NMMA into macro-phages, MRL-lpr mice were fed an arginine-free diet in association with NMMA treatment from 16 to 20 weeks of age (20). Controls were given distilled water and an arginine free diet. Mice in the NMMA group excreted less urinary N/N (0.5 ± 0.2 μmoles/mouse/day vs 10.7 ± 4.8 μmoles/mouse/day, P*** = 0.03; Fig. 1) and had lower joint scores (0.6 ± 0.3 vs 3.1 ± 0.9, P = 0.02; Table 2) than the control group at 20 weeks of age. Proteinuria (2.2 ± 1.7 μg/mouse/day vs 4.4 ± 2.7 μg/mouse/day, P = 0.6; Fig. 2) and renal pathology were not significantly different in the treated and untreated groups, respectively (8.7 ± 3.0 vs 9.2 ± 3.0, P = 0.8; Table 2).

MRL-lpr Mice Treated with an Arginine-Free Diet (Group III)

Earlier studies from our laboratory suggested there was less pathologic disease than expected in control MRL-lpr mice fed an arginine-free diet. We, therefore, assessed the effect of an arginine-free diet administered from 8 to 18 weeks of age on disease in MRL-lpr mice. At 18 weeks, 24-hr urinary N/N excretion was reduced compared to controls, but not significantly (3.7 ± 2.6 μmoles/mouse/day vs 12.3 ± 10.8 μmoles/mouse/day, P = 0.7; Fig. 1). Glomerular pathologic scores were actually higher, although not significantly, in the treatment group when compared to controls (9.4 ± 5.5 vs 4.6 ± 2.2, P = 0.13; Table 2). Proteinuria (1.6 ± 1.2 μg/mouse/day vs 2.8 ± 2.0 μg/mouse/day, P = 0.7; Fig. 2) and joint scores (4.4 ± 3.2 vs 5.8 ± 3.1, P = 0.4; Table 2) were similar in the two diet groups.

Late Treatment of NZB/W Mice with NMMA (Group IV)

NZB/W mice develop a spontaneous autoimmune disease and produce elevated levels of NO as disease progresses (25). To determine the effect of blocking NO production on clinical disease, we treated NZB/W mice with NMMA and an arginine-free diet from 21 to 25 weeks of age. These mice were compared to a control group given distilled water and an arginine-free diet. The NMMA-treated mice had a reduction in N/N excretion when compared to controls (1.0 ± 0.4 μmoles/mouse/day vs 3.6 ± 0.8 μmoles/mouse/day, P = 0.08; Fig. 1). Renal excretion of protein (0.1 ± 0.1 μg/mouse/day vs 2.9 ± 1.5 μg/mouse/day, P = 0.05; Fig. 2) and renal pathologic scores (1.0 ± 0.7 vs 4.4 ± 4.2, P = 0.01; Table 2) were reduced in the treatment group.

Effect of NO Modulation on Anti-DNA Production

In none of the treatment groups was there a difference in sera titers of antibodies to single-stranded or double-stranded DNA as tested by ELISA between the treatment groups and the controls (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

These results indicate that blocking NO production even after the onset of spontaneous autoimmune disease alters the progression of clinical disease. By implication, NO appears to be an important mediator of inflammation in murine models of lupus both in the initiation and progression of disease. As with most forms of immune therapy tested in these mice, intervention prior to disease was more effective than treatment initiated after disease onset. Combined therapy with dietary arginine restriction and NMMA appears more effective than NMMA therapy alone in the treatment of synovitis. Comparing the treatment groups, the efficacy of therapy paralleled the level to which NO production was suppressed, again providing evidence that NO is an important mediator of disease. In addition, our results indicate that blocking NO production was also effective in NZB/W mice, suggesting common mechanisms for end organ inflammation involving NO in both NZB/W and MRL-lpr mice.

Not all interventions that modulated NO production, however, were effective. Based on the therapeutic effectiveness of dietary arginine restriction in the Sprague–Dawley rat glomerulonephritis model, we hypothesized that arginine restriction may reduce disease in MRL-lpr mice (17). Oral arginine restriction, however, was only partially effective in blocking NO production and had no effect on synovitis or glomerulonephritis in MRL-lpr mice. The differing effects of arginine restriction on these two models of glomerulonephritis may refiect enhanced production of arginine by B cells in autoimmune mice (26). Thus, oral intake of arginine may not be a rate-limiting step in the production of NO in MRL-lpr mice as was demonstrated in the Sprague–Dawley rat and in some human studies (17, 27).

NMMA therapy alone reduced urinary N/N levels and proteinuria in older (14–20 weeks) MRL-lpr mice and showed a trend toward reducing proteinuria in mice treated from 16 to 20 weeks with additional arginine restriction. The reduction in proteinuria in Group II may not have been as significant for two reasons. First, the mice in Group II were treated 2 weeks later in disease, after irreversible glomerular damage had begun to occur. Second, treatment in Group II was two weeks shorter in duration.

Late NMMA therapy did not significantly reduce renal pathology in either Group I or Group II by the end of treatment. This reduced efficacy in later disease can be explained by the observation that 36% of all diffuse glomerulonephritis had already occurred by the age of 4 months in these mice (28). The decreased proteinuria in the treatment arm of group I suggests that the NMMA therapy did affect glomerular function and may have slowed the progression of disease. However, it did not prevent the eventual development of pathologic changes. Had we sacrificed the mice at 16–18 weeks of age, a more notable difference in pathologic scores may have been evident.

Late treatment with NMMA was more effective in altering synovitis than glomerulonephritis in MRL-lpr mice. This differential effect on synovitis versus glomerulonephritis may reflect differences in the mechanisms of disease or that glomerulonephritis is more advanced at a given age than is synovitis. Synovitis in MRL-lpr mice is a pathologic rather than clinical disease, as less than 10% of mice ever develop clear swelling of their joints, while the majority develop pathologic synovitis (29). Thus, we cannot state with certainty that synovitis was present in the mice at the time of NMMA treatment. Previous studies indicate, however, that the onset of synovitis occurs before 14–16 weeks of age in most MRL-lpr mice (30). Pathogenetically, glomerulonephritis and synovitis differ in MRL-lpr mice with different genetic loci predisposing to disease and different sets of autoantibodies leading to disease (31, 32). Thus, the inflammatory pathways that result in synovitis may be more sensitive to the blocking of NO synthesis than are pathways leading to glomerulonephritis.

As with many other forms of therapy in MRL-lpr mice, blocking nitric oxide production prior to disease onset rather than after clinical presentation was more effective. This difference in efficacy between early and late therapy may reflect that (a) once inflammation is initiated, multiple pathways in addition to those mediated by NO are responsible for its progression; (b) NO is an important mediator in early, acute but not in chronic inflammation; and (c) while reducing NO production may reduce inflammation, it does not reverse preexisting fibrosis. A combination of these hypotheses seems most likely.

In contrast to a minimal effect of late NMMA therapy on glomerular disease in MRL-lpr mice, glomerulonephritis was significantly decreased in NZB/W mice by blocking NO production. This difference in efficacy of NMMA between the two strains may reflect differences in pathogenesis of disease between the two strains. Although both strains produce glomerular binding antibodies and immune complex glomerulonephritis, the pathways of inflammation that follow initiation of disease differ. Development of nephritis in MRL-lpr mice appears dependent on production of IFN-γ, while disease in NZB/W mice appears to be IL-10 and TNF-α mediated (33, 34, 35). These differences in cytokine production may affect the inflammatory cascade and thus the response to NO modulation.

Alternatively, the inflammatory response in MRL-lpr and NZB/W mice may be very similar and equally responsive to blocking NO production. In both strains proteinuria was decreased by NMMA therapy. Only in the NZB/W mouse was this decrease in proteinuria translated into decreased pathologic disease. As mentioned above, if we had sampled glomerular pathology at an earlier time point in MRL-lpr disease, we may have detected a significant difference. Thus the difference in NMMA treatment on glomerular disease between NZB/W mice and MRL-lpr mice may merely reflect the time of sacrifice and not intrinsic differences in the effectiveness of NMMA therapy between the two strains.

Our results confirm a role for nitric oxide in the progression of murine SLE. Our data suggests that dietary arginine restriction enhances the effectiveness of NMMA treatment. This paper also expands the demonstrated effectiveness of NMMA to a second model of murine lupus, indicating that NO-mediated disease is not restricted to the MRL-lpr strain. Because clinicians rarely, if ever, have the opportunity to treat SLE before clinical presentation, the demonstrated clinical efficacy of NO blockade after disease onset provides support for therapies directed at blocking NO for treatment of inflammatory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was support by the Medical Research Service, Ralph H. Johnson VAMC, NIH Grant AR39162, and grants from the Arthritis Foundation and Lupus Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowenstein CJ, Dinerman JL, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: A physiologic messenger. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:227–237. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-3-199402010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moilanen E, Vapaatalo H. Nitric oxide in inflammation and immune response. Ann. Med. 1995;27:359–367. doi: 10.3109/07853899509002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moncada S, Higgs A. The l-arginine–nitric oxide pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forstermann U, Dun NJ. Immunohistochemical localization of nitric oxide synthases. Methods Enzymol. 1996;268:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler JS, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. Biochemistry of nitric oxide and its redox-activated forms. Science. 1992;258:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1281928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Privalle CT, Keng T, Gilkeson GS, Weinberg JB. The role of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in the pathogenesis of spontaneous murine autoimmune disease. In: Stamler J, Gross SS, Moncada S, editors. The Biology of Nitric Oxide. Elsevier Press; New York, NY: in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liew FY. The role of nitric oxide in parasitic diseases. Ann. Trop. Med. Parisitol. 1993;87:637–642. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1993.11812822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Meide PH, de Labie MCDC, Botman CAD, Aten J, Weening JJ. Nitric oxide suppresses IFN-g production in the spleen of mercuric chloride-exposed brown Norway rats. Cell. Immunol. 1995;161:195–206. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor-Robinson AW, Liew FY, Severn A, Xu D, McSorley SJ, Garside P, Padron J, Phillips RS. Regulation of the immune response by nitric oxide differentially produced by T helper type 1 and T helper type 2 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:980–984. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilkeson GS, Cannon C, Goldman D, Petri M. Correlation of a serum measure of nitric oxide production with lupus disease activity measures. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:s251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miesel R, Zuber M. Reactive nitrogen intermediates, antinuclear antibodies and copper theonein in serum of patients with rheumatic diseases. Rheum. Int. 1993;12:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00290295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashem A, Endoh M, Yano N, Yamauchi F, Nomoto Y, Sakai H. Expression of inducible-NOS in human glomerulonephritis: The possible source is infiltrating monocytes/macrophages. Kidney Int. 1996;50:392–399. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai H, Kohsaka H, Lui MF, Higashiyama H, Hirata Y, Kanno K, Siato I, Miyasaka N. Nitric oxide production an inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in inflammatory arthritides. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:2357–2363. doi: 10.1172/JCI118292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell AJ, Blake DR, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Increased concentrations of nitrite in synovial fluid and serum samples suggest increased nitric oxide synthesis in rheumatic diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1992;51:1219–1222. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.11.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St. Clair EW, Wilkinson WE, Lang T, Sanders L, Misukonis MA, Gilkeson GS, Pisetsky DS, Granger DL, Weinberg JB. Systemic activation for nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1173–1178. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vladutiu AO. Role of nitric oxide in autoimmunity. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1995;76:1–11. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narita I, Border WA, Ketteler M, Ruoslahti E, Noble NA. l-Arginine may mediate the therapeutic effects of low protein diets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4552–4556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews BS, Eisenberg RA, Theofilopoulos AN, Izui S, Wilson CB, McConahey PJ, Murphy ED, Roths JB, Dixon FJ. Spontaneous murine lupus-like syndromes: Clinical and immunopathological manifestations in several strains. J. Exp. Med. 1978;148:1198–1215. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinberg JB, Granger DL, Pisetsky DS, Seldin MF, Misukonis MA, Mason SN, Pippen AM, Ruiz P, Wood WR, Gilkeson GS. The role of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of spontaneous murine autoimmune disease: Increased nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthase expression in MRL-lpr/lpr mice, and reduction of spontaneous glomerulonephritis and arthritis by orally administered NG-monomethyl-Larginine. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:651–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt K, Klatt P, Mayer B. Uptake of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors by macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. Biochem. J. 1994;301:313–316. doi: 10.1042/bj3010313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granger DL, Hibbs JB, Broadnax LM. Urinary nitrate excretion in relation to murine macrophage activation. Influence of dietary l-arginine and oral NG-mono-methyl-l-arginine. J. Immunol. 1991;146:1294–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moshage H, Kok B, Huizenga JR, Jansen PLM. Nitrite and nitrate determinations in plasma: A critical evaluation. Clin. Chem. 1995;41:892–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilkeson GS, Grudier JP, Karounos DG, Pisetsky DS. Induction of anti-double stranded DNA antibodies in normal mice by immunization with bacterial DNA. J. Immunol. 1989;142:1482–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilkeson GS, Ruiz P, Grudier JP, Kurlander RJ, Pisetsky DS. Genetic control of inflammatory arthritis in con-genic lpr mice. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1989;53:460–474. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilkeson GS, Ruiz P, Pippen AMM, Alexander A, Lefkowith JB, Pisetsky DS. Modulation of renal disease in autoimmune NZB/NZW mice by immunization with bacterial DNA. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1389–1397. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimura K, Wada Y, Kimura T, Ohno T, Kobayashi S, Azuma I. Inherited hyperactivation of l-arginine synthesis in gamma + B lymphocytes of systemic autoimmune MRL mice. Int. Immunol. 1990;2:1033–1038. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.11.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibbs JB, Westenfelder C, Taintor R, Vavrin Z, Kablitz C, Baronowski RL, Ward JH, Menlove RL, McMurry MP, Kushner JP, et al. Evidence for cytokine-inducible nitric oxide synthesis from l-arginine in patients receiving interleukin-2 therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:867–877. doi: 10.1172/JCI115666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewicker M, Trautwein G. Glomerular lesions in MRL mice: A light and immunofluorescence microscopic study. J. Vet. Med. B. 1986;33:727–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1986.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hang L, Theofilopoulos AN, Dixon FJ. A spontaneous rheumatoid arthritis-like disease in MRL/lpr mice. J. Exp. Med. 1982;155:1690–1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.6.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Sullivan FX, Fassbender HG, Gay S, Koopman WJ. Etiopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis-like disease in MRL/lpr mice. I. The histomorphologic basis of joint destruction. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:529–536. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson ML, Rao JK, Gilkeson GS, Ruiz P, Eicher EM, Pisetsky DS, Matsuzawa A, Rochelle JM, Seldin MF. Genetic analysis of MRL-lpr mice: Relationship of Fas apoptosis gene to disease manifestations of renal disease-modifying loci. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:1645–1656. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nose M, Nishimura M, Kyogoku M. Analysis of granulomatous arteritis in MRL/Mp autoimmune disease mice bearing lymphoproliferative genes: The use of mouse genetics to dissociate the development of arteritis and glomerulonephritis. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;135:271–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi S, Fossati L, Iwamoto M, Merino R, Motta R, Kobayakawa T, Izui S. Imbalance towards Th1 predominance is associated with acceleration of lupus-like autoimmune syndrome in MRL mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:15997–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI118584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida H, Muchamuel T, Sakaguchi S, Andrade S, Menon S, Howard M. Continuous administration of anti-interleukin-10 antibodies delays onset of autoimmunity in NZB/W F1 mice. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:305–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brennan DC, Yui MA, Wuthrich RP, Kelley BE. Tumor necrosis factor and IL-1 in New Zealand Black/White mice: Enhanced gene expression and acceleration of renal injury. J. Immunol. 1989;143:3470–3475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]