Background: Activin maintains TSC self-renewal in the presence of FGF4 while promoting syncytiotrophoblast differentiation without FGF4.

Results: Bcor is repressed by activin and regulates TSC self-renewal and differentiation by inhibiting trophoblast-specific transcription factors.

Conclusion: Bcor is a downstream target of activin and mediates activin functions in TSCs.

Significance: This study advances our understanding of placental development and placenta-related diseases.

Keywords: activin, differentiation, pluripotency, stem cells, trophoblast, Bcor, activin, trophoblast stem cell, self-renewal

Abstract

The development of a functional placenta is largely dependent upon proper proliferation and differentiation of trophoblast stem cells (TSCs). Activin signaling has long been regarded to play important roles during this process, but the exact mechanism is largely unknown. Here, we demonstrate that the X chromosome gene BCL-6 corepressor (Bcor) is a critical downstream effector of activin to fine-tune mouse TSC fate decision. Bcor was specifically down-regulated by activin A in TSCs in a dose-dependent manner, and immediately up-regulated upon TSC differentiation. Knockdown of Bcor partially compensated for the absence of activin A in maintaining the self-renewal of TSCs together with FGF4, while promoting syncytiotrophoblast differentiation in the absence of FGF4. Moreover, the impaired trophoblast giant cell and spongiotrophoblast differentiation upon Bcor knockdown also resembled the function of activin. Reporter analysis showed that BCOR inhibited the expression of the key trophoblast regulator genes Eomes and Cebpa by binding to their promoter regions. Our findings provide us with a better understanding of placental development and placenta-related diseases.

Introduction

Specification of trophectoderm and inner cell mass, which is composed of trophoblast stem cells (TSCs)4 and embryonic stem cells (ESCs), respectively, is the first cell fate decision event during the mouse early developmental process (1, 2). Unlike ESCs that generate all three germ layers of the embryo, TSCs differentiate to trophoblast giant cells, syncytiotrophoblasts, and spongiotrophoblasts and exclusively contribute to the embryonic part of the placenta, a vital organ that mediates the physiological exchange between the fetus and the mother during mammalian pregnancy (3, 4). Placental development disorders cause a wide range of pregnancy complications in humans, such as pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and even premature death of the fetus (5, 6). Thus, the self-renewal and differentiation of TSCs are under a precise control to provide sufficient trophoblast sub-lineages, while maintaining the stem cell pool for proper placental development.

Extrinsic signaling and intrinsic transcription factors collaborate to regulate TSC fate determination. It is well known that FGF4 signaling and TGF-β/activin/nodal signaling play essential roles during this process (7–9). FGF4 directly up-regulates trophoblast core transcription factors Cdx2, Eomes (eomesodermin), and Sox2 through its downstream effector ERK to maintain the self-renewal state of TSCs (10, 11), whereas activin can either maintain self-renewal or promote syncytiotrophoblast differentiation, depending on the availability of FGF4 (8, 12).

Binding of TGF-β/activin to their serine/threonine kinase receptors initiates signal transduction, leading to the activation of receptors and subsequent phosphorylation of the intracellular signal transducers Smad2/3. The phosphorylated Smad2/3 then form a heterocomplex with Smad4 and are accumulated in the nucleus to regulate the expression of their target genes with the help of other transcription factors or cofactors (13–17). Although the functions of TGF-β/activin in ESCs and the underlying mechanisms have been well investigated (18, 19), how activin exerts its function in TSCs is largely unknown.

Proper activity of X chromosome is essential for placental development. Activation of both X chromosomes in female embryos leads to embryonic lethality due to placental development failure (20, 21). These observations raise the possibility that some key placental regulators may be encoded by X chromosome and that their expression must be precisely controlled. Plac1 and Esx1 have been shown to be two of such X-linked dosage-sensitive regulators (22, 23). BCOR, which encodes an interacting corepressor of BCL-6, is located on the Xp11.4 of the human genome (24). BCOR mutations are the direct cause of human oculofaciocardiodental (OFCD) syndrome in females with genetic disorders affecting ocular, facial, dental, and cardiac systems and embryonic lethality for males (25–27), suggesting an important role of BCOR during embryo development. At the gastrulation stage of mouse embryos, the expression of Bcor is highly restricted to the trophectoderm lineages and later spreads to the embryo proper (28). Recent evidence from Bcor knock-out mice further implies that BCOR may participate in extraembryonic lineage development (29).

In the present study, we provided evidence that Bcor is a downstream target of activin signaling and plays an important role in self-renewal and differentiation of TSCs. BCOR mediates the activity of activin in maintaining TSC self-renewal together with FGF4 while promoting syncytiotrophoblast differentiation in the absence of FGF4 by inhibiting the expression of Eomes and Cebpa.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Reagents

129R3 trophoblast stem cells (kindly provided by Shaorong Gao, Tongji University, Shanghai, China) were cultured as reported previously (30). In brief, feeder-free 129R3 cells were cultured in 70CM+F4H medium composed of 30% TS medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% FBS, 2 mm GlutaMAX, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 100 μm β-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) and 70% feeder-conditional medium (CM) and supplemented with 1 μg/ml heparin (Wako Pure Chemical) and 25 ng/ml FGF4 (Invitrogen). Feeder-conditional medium was supposed to provide TGF-β/activin for TSCs, and for the indicated experiments, it was substituted with 10 ng/ml activin A (R&D Systems). Culture conditions for R1 mouse embryonic stem cells and H1 human embryonic stem cells were described elsewhere (31, 32). Mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells and HEK293FT cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Bcor Knockdown

Specific shRNAs for Bcor were obtained from Sigma (shRNA lentiviral transduction particles TRCN0000081965 and TRCN0000081966). Lentivirus production and infection were performed as described previously (33). Briefly, the shRNA lentiviral vectors were co-transfected into HEK293FT cells together with package plasmids VSV-G and Δ8.9 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The supernatant was collected 72 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore). The virus-containing supernatant was applied to TSCs in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene, and 48 h later, the cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/ml) for an additional 3–5 days before the stable cell lines could be generated.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was then performed through reverse transcription using 1 μg of the extracted RNA, oligo(dT), and reverse transcriptase. qRT-PCR was carried out in triplicate for each sample using EvaGreen dye (Biotium) on LC480 (Roche Applied Science) system. All the primers used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

qRT-PCR primers

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | CATGGCCTTCCGTGTTCCTA | CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGAT |

| Bcor | GCTGTGGAGAATGACCACTTAG | CATGATGGTTCTCCCTGAGTATG |

| Cdx2 | CAAGGACGTGAGCATGTATCC | GTAACCACCGTAGTCCGGGTA |

| Eomes | GAGCTTCAACATAAACGGACTCAA | CGGCCAGAACCACTTCCA |

| Elf5 | ATGTTGGACTCCGTAACCCAT | GCAGGGTAGTAGTCTTCATTGCT |

| Nanog | ACCTGAGCTATAAGCAGGTTAAGAC | GTGCTGAGCCCTTCTGAATCAGAC |

| Pou5f1 | CACGAGTGGAAAGCAACTCA | AGATGGTGGTCTGGCTGAAC |

| Fgfr2c | CACCAACTGCACCAATGAAC | CTGGGTGAGATCCAAGTATTCC |

| Ascl2 | AAGCACACCTTGACTGGTACG | AAGTGGACGTTTGCACCTTCA |

| Gcm1 | GGACGTATGGAGACTACGAAGA | CAAAGAGTTCTGGGAGGGAAAG |

| Tpbpa | AAGTTAGGCAACGAGCGAAA | AGTGCAGGATCCCACTTGTC |

| Pl-1 | CTGCTGACATTAAGGGCA | AACAAAGACCATGTGGGC |

| Pl-2 | TCCTTCTCTGGGGCACTCCTGTT | CCATGAAGGCTTTTGAAGCAAGATCA |

| Plf | CATCTCCAAAGCCACAGACATAAA | GTTCTTCTTTTCTTCATCTCCA |

| Esrrb | TTTCTGGAACCCATGGAGAG | AGCCAGCACCTCCTTCTACA |

| Lefty1 | CCAACCGCACTGCCCTTAT | CGCGAAACGAACCAACTTGT |

| Cebpa | CAAGAACAGCAACGAGTACCG | GTCACTGGTCAACTCCAGCAC |

| Pcdh12 | ACTCGGGTCTTGAGGATCT | TGTCCCTGTTGTCCGTAAAG |

| Gjb3 | CAACACCGTGGATTGCTACA | GTGGACTTGCCCTTGCTTAT |

| Synb | GCCTTCTGCCTCAACTCTT | CAGGCACCGTTTGGTTATTG |

| BCOR | CCTGTACTGCTTAGAGAACA | CAAGTGATCGTTCTCAACAG |

| LEFTY1 | CCCTGAAGCACCAATGACC | TCCCTCCTTGATGCTGACGA |

Immunoblotting, Immunoprecipitation, Immunofluorescence and Antibodies

For immunoblotting, cells were lysed in TNE buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) containing freshly added proteinase inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) for 30 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were resolved by SDS-PAGE gel. For immunoprecipitation, one-tenth of the cell lysate was preserved as whole cell lysate, and the other nine-tenths of the cell lysate was incubated with 2 μg of antibodies and 30 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Zymed Laboratories Inc.. overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with TNE buffer and then analyzed using immunoblotting. For immunofluorescence, cells were sequentially treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, 0.5% BSA for 30 min, the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, and finally the secondary antibody for 1 h in the dark. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). Images were obtained with confocal Olympus FluoView 1200 microscope. The following antibodies were used: α-PL-1 (sc-34713) and α-GAPDH (sc-20357) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; α-GCM1 (ab2) from Sigma-Aldrich; and α-CDX2 (27189) from Signalway Antibody.

TSC Differentiation Assay

The next day after passaging, cells were cultured in TS medium in the absence of FGF4, heparin, and CM to induce differentiation. For the indicated experiments, TS medium was supplemented with 10 ng/ml activin A (TS+Ac10 medium), 25 ng/ml FGF4, and 1 μg/ml heparin (TS+F4H medium) or 10 μm SB431542 (TS+SB10 medium). The culture medium was replaced every day before the cells were harvested.

Proliferation and TUNEL Assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells/well into 24-well plates, and cultured in the stemness condition (70CM+F4H medium) for 3 days or in the differentiation-inducing condition (TS medium) for 5 days. Cell numbers were counted every day or every other day, respectively. TUNEL assay (Roche Applied Science) was performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were trypsinized and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 60 min, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 min on ice, and then the labeling mixture and DAPI were added sequentially to the cells for staining the apoptotic cells and cell nucleus, respectively.

Analysis of Endoreduplication

After induction of differentiation for 0, 2, 4, or 6 days, cells were detached with TrypLE (Gibco) and fixed with cold 70% ethanol. Then, the cells were stained with propidium iodide for 30 min and analyzed by flow cytometry for DNA content using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Cells with DNA content ≤4n (2n cells in G0/G1 phase, 2n–4n cells in S phase, and 4n cells in G2/M phase) represent those non-endoreduplicated cells, whereas cells with DNA content ≥8n are defined as endoreduplicated trophoblast giant cells.

Promoter Reporter Analysis

The Eomes promoter segment (−1000 bp to +1000 bp) and the Cebpa promoter segment (−250 bp to +200 bp) were PCR-amplified using mouse genomic DNA as template, and then cloned into the pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector between KpnI/XhoI sites. The primers are: 5′-ATAGGTACCTGGGGCTGAGCGCTGCAA-3′ (Cebpa pro sense); 5′-TCTCTCGAGAAAGCCAAAGGCGGCGTTG-3′ (Cebpa pro antisense); 5′-ATAGGTACCCGTCCTTGACTGTTTGCGGAAACGCAGG-3′ (Eomes pro sense); and 5′-ATACTCGAGATTGGACGCGGGGTACACGGGTCCGT-3′ (Eomes pro antisense). Potential regulatory roles for BCOR on these promoter activities were evaluated in 129R3 TSCs according to the following procedure. Cells were seeded into a 24-well plate and transiently transfected with the reporter constructs at 30–50% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). pRenilla-TK vector was used as an internal control. Then, the cells were maintained in stemness condition for 48 h before they were collected and measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were repeated at least three times. The values were presented as mean ± S.D., and the significance between means was calculated using Student's t test. p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant (* for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01 and *** for p ≤ 0.001).

Results

Bcor Is Specifically Down-regulated by Activin Signaling in TSCs

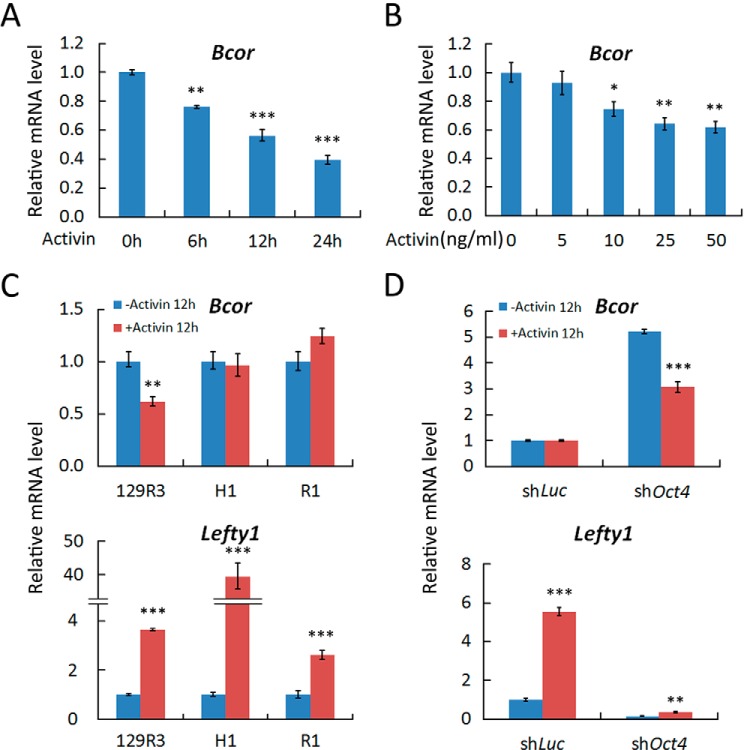

To determine how activin signaling regulates self-renewal and differentiation of TSCs, we treated 129R3 mouse TSCs with activin A and performed qRT-PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, activin A treatment down-regulated Bcor mRNA levels in both a time-dependent and dose-dependent manner, indicating that Bcor is a downstream target of activin.

FIGURE 1.

Activin down-regulates Bcor in TSCs. A and B, 129R3 mouse TSCs were treated with 25 ng/ml activin A for the indicated time (A) or treated 12 h for the indicated activin A concentrations (B) and then harvested for qRT-PCR analysis. C and D, R1 ESCs (C) and ESC-induced TSC-like cells (D) were treated with 25 ng/ml activin A for 12 h before being harvested for qRT-PCR analysis. shLuc, luciferase shRNA. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

To further examine the cell type specificity of the down-regulation of Bcor by activin, we treated R1 mouse ESCs and H1 human ESCs with 25 ng/ml activin A for 12 h. No significant down-regulation of Bcor can be seen in these cells (Fig. 1C), although both of them exhibited the up-regulation of the classical activin target gene Lefty1 (34). Repression of Oct4 (Pou5f1) expression has been shown to induce ESCs to transdifferentiate into TSC-like cells (35). Consistently, down-regulation of Bcor by activin only occurred in Oct4 knockdown R1 cells (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data indicate that activin can down-regulate Bcor expression specifically in TSCs.

Bcor Is Highly Expressed in Trophoblast Lineages and Up-regulated upon TSC Differentiation

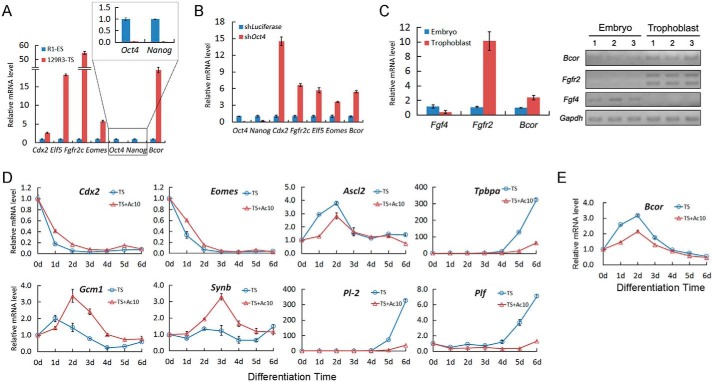

As two of the first specified cell lineages, TSCs and ESCs express different genes to dictate their own cellular phenotypes. High expression of TSC marker genes Cdx2, Eomes, Elf5, and Fgfr2c and low expression of ESC marker genes Oct4 and Nanog in TSCs clearly distinguished them from ESCs. Notably, Bcor was only highly expressed in TSCs (Fig. 2A). This result was confirmed by acquisition of high Bcor expression upon ESC to TSC transdifferentiation by lentivirus-mediated Oct4 knockdown (Figs. 1D and 2B). We further examined the in vivo expression of Bcor in early mouse embryogenesis. Fgf4 and Fgfr2 were used as specific lineage markers, as it is widely regarded that the response of trophoblast-localized FGF receptor Fgfr2 to the embryo-produced Fgf4 is required for the maintenance of TSC self-renewal (36). Bcor showed a similar expression pattern with Fgfr2 (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these observations indicate that Bcor is highly expressed in trophoblast lineages, consistent with a previous study (28).

FIGURE 2.

Activin has profound effects on the expression of TSC pluripotency and differentiation markers. A and B, TSCs (A) or ESC-induced TSC-like cells (B) were harvested together with ESCs for assessment of the expression of Bcor or lineage-specific markers using qRT-PCR. shLuciferase, luciferase shRNA; shOct4, Oct4 shRNA. C, qRT-PCR (left panel) and conventional PCR (right panel) were performed to detect the Bcor mRNA level in both the embryonic part and the trophoblast part of the embryonic day 8.5 mouse embryo. D and E, 129R3 cells were cultured in TS medium (blue) or TS medium plus 10 ng/ml activin A (TS+Ac10 medium, red) and harvested every 24 h until day 6. The expression of trophoblast markers (C) and Bcor (D) was analyzed using qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

We next investigated the expression profile of Bcor during TSC differentiation. Deprivation of both CM and FGF4 (TS medium) resulted in rapid differentiation of TSCs, reflected by a decrease of the TSC self-renewal markers (Cdx2 and Eomes) and an increase of the trophoblast differentiation markers (Gcm1, Synb, Ascl2, Tpbpa, Pl-2, and Plf) (Fig. 2D). The presence of 10 ng/ml activin A (TS+Ac10 medium) delayed the down-regulation of the self-renewal markers Cdx2 and Eomes and enhanced the expression of the syncytiotrophoblast markers Gcm1 and Synb. However, differentiation toward trophoblast giant cells (Pl-2 and Plf) and spongiotrophoblast (Ascl2 and Tpbpa) was inhibited (12) (Fig. 2D). Bcor mRNA level was immediately up-regulated upon withdrawal of both FGF4 and CM and reached the peak at 2 days after differentiation, and then gradually declined (Fig. 2E). The presence of activin A decreased Bcor expression during this process, which is consistent with the inhibitory effect of activin shown in Fig. 1. Taken together, these data indicate that activin inhibits the up-regulation of Bcor during TSC differentiation.

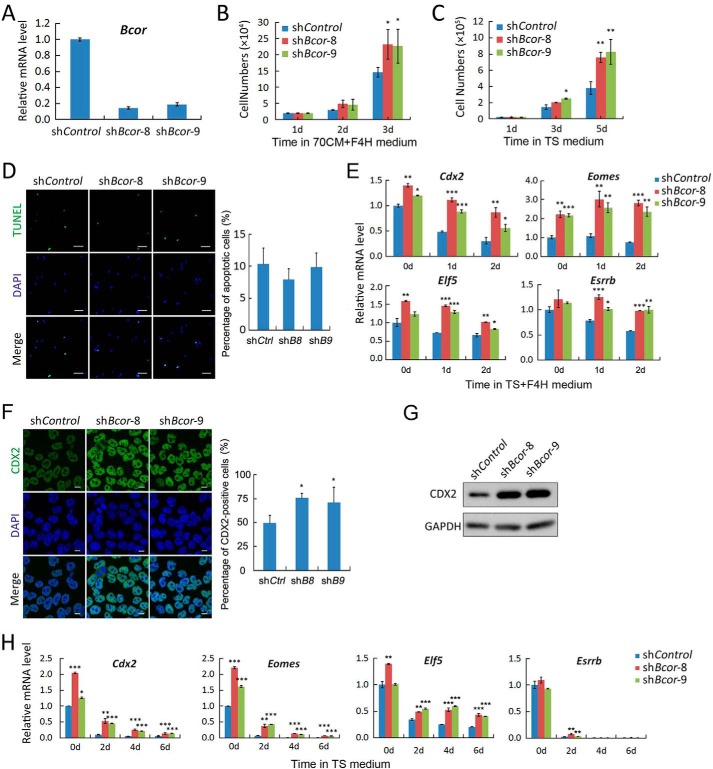

Bcor Knockdown Sustains TSC Self-renewal

The Bcor expression pattern suggests its potential regulatory roles in TSCs, which prompted us to analyze its cellular functions. TSCs were stably infected with lentiviruses carrying either control (shControl) or Bcor shRNAs (shBcor-8 or shBcor-9). qRT-PCR showed that both of the two Bcor shRNAs exhibited more than 80% knockdown efficiency (Fig. 3A). The Bcor knockdown cells showed increased proliferation rate with no obvious apoptosis when compared with control cells under either promoting self-renewal or inducing differentiation conditions (Fig. 3, B–D). To test whether depletion of Bcor prevents TSCs from undergoing autonomous or induced differentiation and makes the cells inclined to stay in the self-renewal state, cells were cultured only in the presence of FGF4 (TS+F4H medium) for 0, 1, and 2 days, respectively, and the stem state was determined by the expression of the pluripotency markers Cdx2, Eomes, Elf5, and Esrrb. As shown in Fig. 3E, shControl cells showed a gradual decrease of pluripotency marker expression, suggesting that FGF4 alone could not maintain the self-renewal state of TSCs. In contrast, the down-regulation of those pluripotency markers was totally blocked (Eomes and Esrrb) or partially inhibited (Cdx2 and Elf5) upon Bcor knockdown. This observation was verified by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting of CDX2 protein levels after 4 days of culture in TS+F4H medium (Fig. 3, F and G). Even in the absence of FGF4, silencing Bcor could still slow the down-regulation of stemness markers (Fig. 3H). Collectively, these results indicate that depletion of Bcor sustains the self-renewal of TSCs, mimicking the function of activin.

FIGURE 3.

Knockdown of Bcor promotes self-renewal of TSCs. TSCs were infected with lentiviruses carrying control or Bcor shRNAs and selected with puromycin. A, qRT-PCR was performed for Bcor expression in the resultant 129R3 stable cells. B, cells were cultured in 70CM+F4H medium to maintain self-renewal, and the cell numbers were counted every day until day 3. C, cells were cultured in TS medium to induce differentiation, and the cell numbers were counted every the other day until day 5. D, cells cultured in 70CM+F4H medium were subjected to TUNEL assay. Scale bars, 100 μm. The right panel shows the percentage of apoptotic cells counted from five fields of each sample. E, cells were cultured in TS medium plus 25 ng/ml FGF4 and 1 μg/ml heparin (TS+F4H medium) for the indicated times, and the expression of the self-renewal markers Cdx2, Eomes, Elf5, and Esrrb was determined by qRT-PCR. F and G, cells were cultured in TS+F4H medium for 4 days before they were harvested for anti-CDX2 immunostaining (F) or anti-CDX2 immunoblotting (G). GAPDH served as a loading control. Scale bars, 10 μm. Five fields of each sample were quantified for the ratio of CDX2-positive cells. H, cells were cultured in TS medium for the indicated times, and the expression of Cdx2, Eomes, Elf5, and Esrrb was determined by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

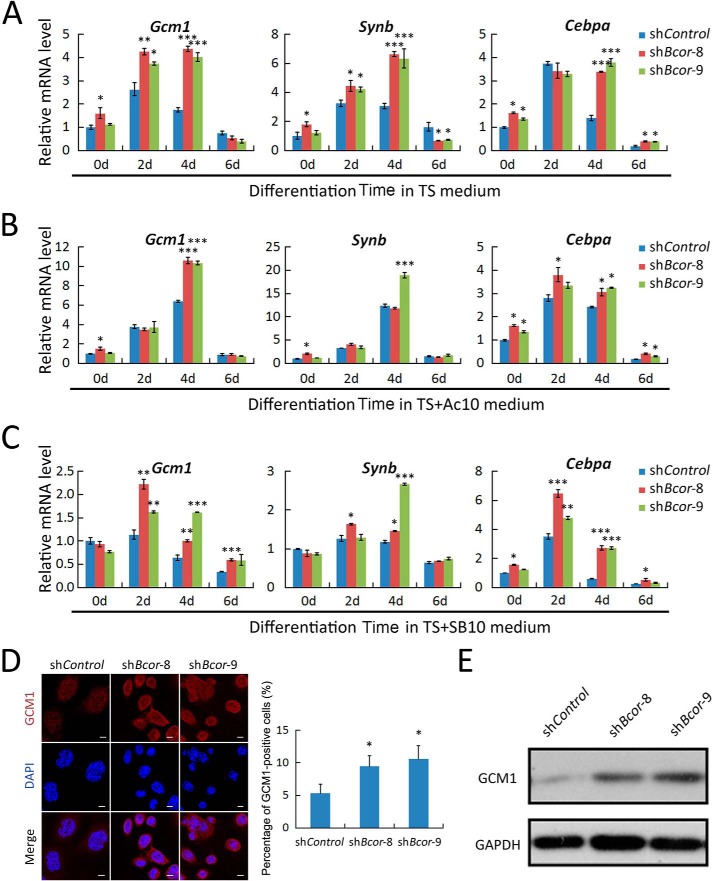

Bcor Inhibits Syncytiotrophoblast Differentiation

In addition to promoting self-renewal, activin also promotes syncytiotrophoblast differentiation in the absence of FGF4 (12). Thus, we investigated whether Bcor participates in this process. We cultured TSCs in either TS medium (Fig. 4A) or TS+Ac10 medium (Fig. 4B) to trigger differentiation for 0, 2, 4, and 6 days. The expression of syncytiotrophoblast markers (Gcm1, Synb, and Cebpa) showed a dynamic change: increased at 2 and 4 days of differentiation and decreased at 6 days in TS medium (Fig. 4A). Bcor knockdown further enhanced their expression. Activin also promoted expression of these markers (Figs. 2D and 4B), whereas Bcor knockdown cells showed only mild enhancement of syncytiotrophoblast marker gene expression when compared with control cells in TS+Ac10 medium. These data suggest that Bcor acts as a negative regulator downstream of activin to inhibit syncytiotrophoblast differentiation.

FIGURE 4.

Knockdown of Bcor promotes syncytiotrophoblast differentiation of TSCs. A–C, Bcor knockdown TSCs (shBcor-8 and shBcor-9) and control TSCs (shControl) were cultured in TS medium (A), TS+Ac10 medium (B), or TS medium plus 10 μm SB431542 (TS+SB10 medium) (C) to allow differentiation for 0, 2, 4, and 6 days before being harvested for qRT-PCR analysis of the syncytiotrophoblast markers Gcm1, Synb, and Cebpa. D and E, cells differentiated in TS medium for 4 days were harvested for anti-GCM1 immunostaining (D) and immunoblotting (E). Scale bar: 10 μm. Five fields of each sample were quantified for the ratio of GCM1-positive cells. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

Consistent with the promoting role of activin in syncytiotrophoblast differentiation, the TGF-β/activin receptor inhibitor SB431542 dramatically decreased the expression of these markers during TS medium-induced differentiation (Fig. 4C). However, the up-regulation of marker genes was still observed in the Bcor knockdown cells, further confirming that Bcor acts downstream of activin to inhibit syncytiotrophoblast differentiation. These data were further verified by higher GCM1 protein expression in the Bcor knockdown cells, as shown by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting (Fig. 4, D and E).

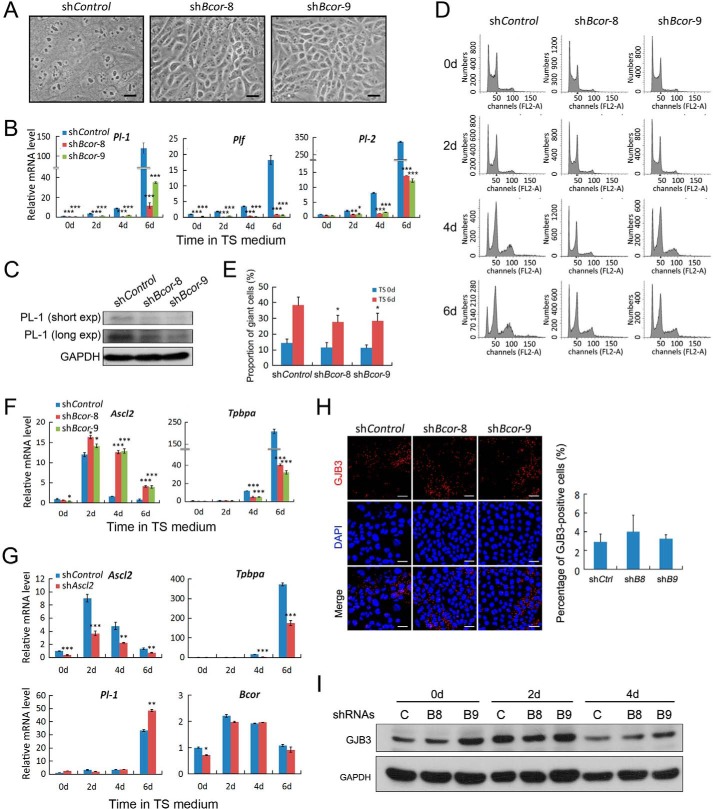

Bcor Is Required for Proper Differentiation of Trophoblast Giant Cells and Spongiotrophoblast

In addition to promoting self-renewal and syncytiotrophoblast differentiation, activin also blocks differentiation toward trophoblast giant cells and disrupts spongiotrophoblasts (12). Therefore, we further examined the function of Bcor in differentiation of these two trophoblast lineages. After withdrawal of both FGF4 and CM for 4 days, control TSCs mainly differentiated into trophoblast giant cells with big cell bodies and enlarged nuclei, whereas Bcor knockdown greatly attenuated the number of trophoblast giant cells (Fig. 5A; also see Fig. 4D). Examination of the expression levels of trophoblast giant cell markers (Pl-1, Pl-2, and Plf) using either qRT-PCR or immunoblotting also confirmed this observation (Fig. 5, B and C). Flow cytometry detection of the endoreduplication of trophoblast giant cells showed that Bcor knockdown reduced the numbers of polyploid cells when compared with control cells (Fig. 5, D and E). Moreover, Bcor knockdown was associated with enhanced Ascl2 (previously known as Mash2) expression and decreased Tpbpa expression, indicating abnormal spongiotrophoblast differentiation (Fig. 5F). Ascl2 is an essential transcription factor required for proper differentiation into spongiotrophoblast (37, 38). However, knockdown of Ascl2 had no influence on Bcor expression (Fig. 5G), suggesting that Bcor acts upstream of Ascl2 to regulate spongiotrophoblast differentiation. Apart from the three major trophoblast lineages mentioned above, TSCs can also generate a small part of trophoblast glycogen cells named by their intracellular accumulation of glycogen (39). Our results showed that Bcor had no obvious effect on this process, as revealed by the protein levels of the marker Gjb3 (Fig. 5, H and I).

FIGURE 5.

Bcor is required for trophoblast giant cell differentiation. A, representative images showing the morphology of shControl, shBcor-8, and shBcor-9 TSCs after 4 days of differentiation in TS medium. Scale bars represent 250 μm. B, cells were cultured in TS medium to allow differentiation for the indicated time points. The mRNA levels of the trophoblast giant cell markers Pl-2 and Plf were determined by qRT-PCR. C, PL-1 protein was detected using immunoblotting after 6 days of differentiation in TS medium. short exp, short exposure; long exp, long exposure. D and E, cells were cultured in TS medium for 0, 2, 4, and 6 days, respectively, and the cellular DNA content was measured by FACS (D). The percentages of cells with DNA content ≥ 8n in day 6 are shown in the bar graph (E). F, cells were cultured in TS medium to allow differentiation for the indicated time points. The mRNA levels of the spongiotrophoblast markers Ascl2 and Tpbpa were determined by qRT-PCR. G, TSCs expressing control or Ascl2 shRNAs were cultured in TS medium to induce differentiation for 0, 2, 4, and 6 days, respectively, and then they were collected for qRT-PCR analysis to determine the expression of the lineage markers and Bcor. H, cells were differentiated in TS medium for 4 days and harvested for anti-GJB3 immunostaining. Scale bar: 50 μm. I, cells differentiated in TS medium for the indicated time points were harvested for anti-GJB3 immunoblotting. C, shControl; B8, shBcor-8; B9, shBcor-9. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

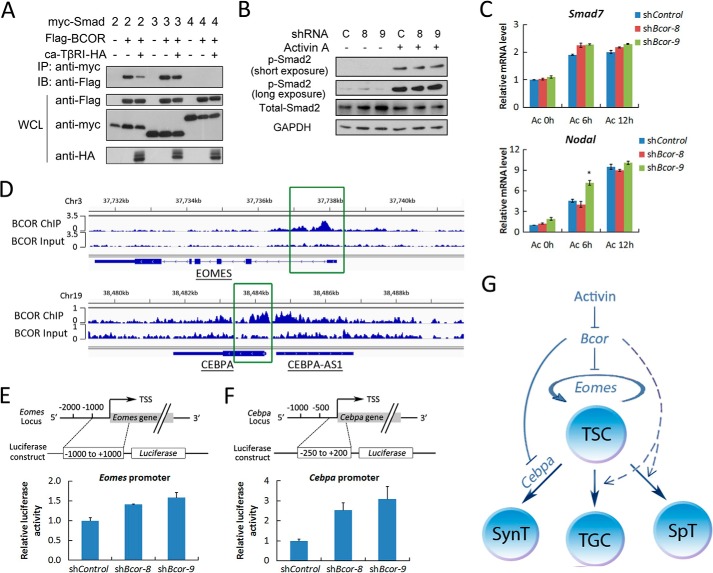

BCOR Negatively Regulates Eomes and Cebpa Promoter Activity

BCL-6 has been reported to interact with Smad3 and Smad4 and negatively regulate TGF-β signaling through disrupting the Smad-p300 interaction (40). As BCOR is a BCL-6-interacting corepressor, we tested whether BCOR could function through inhibiting activin signaling. An immunoprecipitation experiment showed that BCOR interacted with Smad2 and Smad3, but not with Smad4 (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the interaction between BCOR and Smad2/3 was slightly reduced by the active TGF-β type I receptor. However, BCOR had no influence on both Smad2 phosphorylation and the expression of the activin target genes Nodal and Smad7 (Fig. 6, B and C). These results suggest that BCOR exerts its function independent of activin signaling, which is in agreement with the result that Bcor knockdown promoted syncytiotrophoblast differentiation in the presence of SB431542 (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 6.

BCOR regulates TSC self-renewal and differentiation by inhibiting Eomes and Cebpa. A, HEK293FT cells were co-transfected with constructs carrying Smads, BCOR, and active TGF-β type I receptor (ca-TβRI) as indicated for 48 h before they were harvested. Cell lyses were precipitated with anti-Myc antibody, followed by anti-FLAG immunoblotting (IB) to detect the interaction between BCOR and Smads. IP, immunoprecipitation; WCL, whole cell lysate. B and C, self-renewing cells were starved in TS+F4H medium for 12 h and then treated with 25 ng/ml activin A for the indicated times. The Smad2 phosphorylation level (B, p-Smad2) or the mRNA levels of Nodal and Smad7 (C) are shown. D, the binding of BCOR to EOMES and CEBPA promoters based on the ChIP sequencing of Huang et al. (42). E and F, luciferase reporter constructs with indicated Eomes or Cebpa promoter regions (upper panel) were transfected into TSCs cultured in self-renewal condition, and the cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and then subjected to luciferase activity determination. G, schematic model for the function of activin signaling in controlling mouse TSC fate through down-regulating Bcor. Activin inhibits the expression of Bcor, which in turn negatively regulates TSC self-renewal and syncytiotrophoblast differentiation through down-regulating Eomes and Cebpa. The solid line indicates direct effect, while the dotted line indicates unclear mechanisms. The dark blue line and cycle represent differentiation and self-renewal, respectively. TGC, trophoblast giant cells; SynT, syncytiotrophoblasts; SpT, spongiotrophoblasts. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3; *, p < 0.05).

As BCOR is a nuclear protein in TSCs (41), it is possible that BCOR could regulate gene expression through direct DNA binding. According to previously published ChIP sequencing data (42), we found that BCOR could directly bind to the promoter of the stemness gene Eomes and the syncytiotrophoblast gene Cebpa (Fig. 6D). Based on the binding sites of BCOR on these promoter regions, we constructed Eomes and Cebpa promoter reporters and observed that the promoter activity was significantly enhanced upon Bcor knockdown (Fig. 6, E and F). These data suggest that BCOR can down-regulate the expression of these genes.

Discussion

The self-renewal and differentiation of TSCs play a fundamental role for the proper development of placenta and are under precise control of both extrinsic stimuli and intrinsic core transcription factors. In contrast to the well characterized roles of activin signaling in ESCs (19, 43), how activin regulates self-renewal and differentiation of TSCs remains largely unknown. The present study demonstrated for the first time that the transcription corepressor Bcor is a downstream target of activin signaling to regulate TSC self-renewal and differentiation (Fig. 6G).

Loss of function of Bcor in mice showed a strong parent-of-origin effect; that is, only the paternal Bcor null allele can be transmitted to offspring, whereas none of the offspring produced by heterozygous females mated with wild type males carry the Bcor null allele (29). This is due to the imprinted paternal X chromosome inactivation in extraembryonic tissues, especially the placenta where Bcor is highly expressed (28). Our results showing that Bcor is essential for TSC self-renewal and differentiation and thus proper placental development provide a molecular interpretation for the embryonic lethality observed in Bcor knock-out mice.

We observed that Bcor was highly expressed in TSCs, quickly up-regulated upon differentiation of TSCs within the first 48 h, and subsequently declined. Furthermore, activin repressed Bcor expression in TSCs but not in ESCs, but the underlying mechanism is unknown. It is possible that some lineage-specific transcription factors may be important for this cell type-specific regulation (44).

It has been shown that a transcriptional network established by EOMES, TCFAP2C, and SMARCA4 could target large spectrum of genes essential for the maintenance of the TSC self-renewal state (45). BCOR has been suggested to be able to bind to the promoter region of EOMES (42), and we demonstrated that BCOR negatively regulates Eomes expression. Furthermore, knockdown of Bcor maintained the self-renewal state of TSCs cultured only in the presence of FGF4. These data strongly indicate a critical role of BCOR in TSC self-renewal maintenance.

Bcor depletion also makes TSCs more prone to differentiate toward syncytiotrophoblast at the expense of spongiotrophoblast and trophoblast giant cells in the absence of both activin and FGF4. These findings further demonstrated that Bcor, as an activin target gene, could contribute to the function of activin in regulating TSC differentiation. CEBPA is an important regulator of syncytiotrophoblast, as double knock-out of Cebpa and its homolog Cebpb leads to embryonic lethality due to impaired syncytiotrophoblast development (46). Our results revealed that Bcor knockdown enhanced Cebpa expression and its promoter activity, which is in accordance with the binding of BCOR to the promoter region of CEBPA (42). Our data also suggest that BCOR is required for the differentiation of TSCs to trophoblast giant cells. How BCOR promotes trophoblast giant cell differentiation is still unclear.

Bcor mutations have been closely linked to OFCD syndrome. ESCs with Bcor loss of function showed impaired mesoderm, especially hematopoietic lineages differentiation capacity (29), which is consistent with the observation that the mutant BCOR allele is localized on the inactivated X chromosome in most of the blood cells of the OFCD patient (25). In addition, BCOR mutation results in abnormal activation of AP-2α that mediates the increased osteo-dentinogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells, perhaps providing an explanation for the abnormal root growth in most OFCD patients (47). However, the molecular basis for the function of BCOR in OFCD syndrome development needs further investigation.

Author Contributions

G. Z. and Y. G. C. designed the study and wrote the paper. T. F., Z. L., and X. Y. provided constructive suggestions for the whole study. All authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shaorong Gao (Tongji University, Shanghai, China) for providing 129R3 mouse TSCs. We thank Xuanhao Xu for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the 973 Program (2011CB943803 and 2013CB933700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31221064 and 31330049) (to Y. G. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- TSC

- trophoblast stem cell

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- C/EBP

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

- CM

- conditional medium

- OFCD

- oculofaciocardiodental

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- shControl

- control shRNA.

References

- 1. Bergsmedh A., Donohoe M. E., Hughes R. A., Hadjantonakis A. K. (2011) Understanding the molecular circuitry of cell lineage specification in the early mouse embryo. Genes (Basel) 2, 420–448, 10.3390/genes2030420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suwiśka A., Czoøwska R., Ozdzeński W., Tarkowski A. K. (2008) Blastomeres of the mouse embryo lose totipotency after the fifth cleavage division: expression of Cdx2 and Oct4 and developmental potential of inner and outer blastomeres of 16- and 32-cell embryos. Dev. Biol. 322, 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cross J. C., Werb Z., Fisher S. J. (1994) Implantation and the placenta: key pieces of the development puzzle. Science 266, 1508–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossant J., Cross J. C. (2001) Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norwitz E. R. (2006) Defective implantation and placentation: laying the blueprint for pregnancy complications. Reprod. Biomed. Online 13, 591–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jauniaux E., Van Oppenraaij R. H., Burton G. J. (2010) Obstetric outcome after early placental complications. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 22, 452–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka S., Kunath T., Hadjantonakis A. K., Nagy A., Rossant J. (1998) Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282, 2072–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erlebacher A., Price K. A., Glimcher L. H. (2004) Maintenance of mouse trophoblast stem cell proliferation by TGF-β/activin. Dev. Biol. 275, 158–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guzman-Ayala M., Ben-Haim N., Beck S., Constam D. B. (2004) Nodal protein processing and fibroblast growth factor 4 synergize to maintain a trophoblast stem cell microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15656–15660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adachi K., Nikaido I., Ohta H., Ohtsuka S., Ura H., Kadota M., Wakayama T., Ueda H. R., Niwa H. (2013) Context-dependent wiring of Sox2 regulatory networks for self-renewal of embryonic and trophoblast stem cells. Mol. Cell 52, 380–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu C. W., Yabuuchi A., Chen L., Viswanathan S., Kim K., Daley G. Q. (2008) Ras-MAPK signaling promotes trophectoderm formation from embryonic stem cells and mouse embryos. Nat. Genet. 40, 921–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Natale D. R., Hemberger M., Hughes M., Cross J. C. (2009) Activin promotes differentiation of cultured mouse trophoblast stem cells towards a labyrinth cell fate. Dev. Biol. 335, 120–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Massagué J., Chen Y.-G. (2000) Controlling TGF-β signaling. Genes Dev. 14, 627–644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Massagué J., Seoane J., Wotton D. (2005) Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 19, 2783–2810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng X. H., Derynck R. (2005) Specificity and versatility in TGF-β signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 659–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Datto M., Wang X. F. (2000) The Smads: transcriptional regulation and mouse models. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 11, 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heldin C. H., Miyazono K., ten Dijke P. (1997) TGF-β signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 390, 465–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watabe T., Miyazono K. (2009) Roles of TGF-β family signaling in stem cell renewal and differentiation. Cell Res. 19, 103–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fei T., Chen Y.-G. (2010) Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation by TGF-β family signaling. Sci. China Life Sci. 53, 497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang J., Mager J., Chen Y., Schneider E., Cross J. C., Nagy A., Magnuson T. (2001) Imprinted X inactivation maintained by a mouse Polycomb group gene. Nat. Genet. 28, 371–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marahrens Y., Panning B., Dausman J., Strauss W., Jaenisch R. (1997) Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 11, 156–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jackman S. M., Kong X., Fant M. E. (2012) Plac1 (placenta-specific 1) is essential for normal placental and embryonic development. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 79, 564–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Y., Behringer R. R. (1998) Esx1 is an X-chromosome-imprinted regulator of placental development and fetal growth. Nat. Genet. 20, 309–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huynh K. D., Fischle W., Verdin E., Bardwell V. J. (2000) BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev. 14, 1810–1823 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng D., Thakker N., Corcoran C. M., Donnai D., Perveen R., Schneider A., Hadley D. W., Tifft C., Zhang L., Wilkie A. O., van der Smagt J. J., Gorlin R. J., Burgess S. M., Bardwell V. J., Black G. C., Biesecker L. G. (2004) Oculofaciocardiodental and Lenz microphthalmia syndromes result from distinct classes of mutations in BCOR. Nat. Genet. 36, 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Horn D., Chyrek M., Kleier S., Lüttgen S., Bolz H., Hinkel G. K., Korenke G. C., Riess A., Schell-Apacik C., Tinschert S., Wieczorek D., Gillessen-Kaesbach G., Kutsche K. (2005) Novel mutations in BCOR in three patients with oculo-facio-cardio-dental syndrome, but none in Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 13, 563–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kondo Y., Saitsu H., Miyamoto T., Nishiyama K., Tsurusaki Y., Doi H., Miyake N., Ryoo N. K., Kim J. H., Yu Y. S., Matsumoto N. (2012) A family of oculofaciocardiodental syndrome (OFCD) with a novel BCOR mutation and genomic rearrangements involving NHS. J Hum. Genet. 57, 197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wamstad J. A., Bardwell V. J. (2007) Characterization of Bcor expression in mouse development. Gene Expr. Patterns 7, 550–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wamstad J. A., Corcoran C. M., Keating A. M., Bardwell V. J. (2008) Role of the transcriptional corepressor Bcor in embryonic stem cell differentiation and early embryonic development. PLoS One 3, e2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu T., Wang H., He J., Kang L., Jiang Y., Liu J., Zhang Y., Kou Z., Liu L., Zhang X., Gao S. (2011) Reprogramming of trophoblast stem cells into pluripotent stem cells by Oct4. Stem Cells 29, 755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Z., Fei T., Zhang J., Zhu G., Wang L., Lu D., Chi X., Teng Y., Hou N., Yang X., Zhang H., Han J. D., Chen Y. G. (2012) BMP4 Signaling acts via dual-specificity phosphatase 9 to control ERK activity in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 10, 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fei T., Zhu S., Xia K., Zhang J., Li Z., Han J. D., Chen Y. G. (2010) Smad2 mediates Activin/Nodal signaling in mesendoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Res 20, 1306–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang J., Fei T., Li Z., Zhu G., Wang L., Chen Y. G. (2013) BMP induces cochlin expression to facilitate self-renewal and suppress neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8053–8060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Besser D. (2004) Expression of Nodal, lefty-a, and lefty-B in undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells requires activation of Smad2/3. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45076–45084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niwa H., Miyazaki J., Smith A. G. (2000) Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat. Genet. 24, 372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roberts R. M., Fisher S. J. (2011) Trophoblast stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 84, 412–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guillemot F., Nagy A., Auerbach A., Rossant J., Joyner A. L. (1994) Essential role of Mash-2 in extraembryonic development. Nature 371, 333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanaka M., Gertsenstein M., Rossant J., Nagy A. (1997) Mash2 acts cell autonomously in mouse spongiotrophoblast development. Dev. Biol. 190, 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bouillot S., Rampon C., Tillet E., Huber P. (2006) Tracing the glycogen cells with protocadherin 12 during mouse placenta development. Placenta 27, 882–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang D., Long J., Dai F., Liang M., Feng X. H., Lin X. (2008) BCL6 represses Smad signaling in transforming growth factor-β resistance. Cancer Res. 68, 783–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gearhart M. D., Corcoran C. M., Wamstad J. A., Bardwell V. J. (2006) Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 6880–6889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang C., Hatzi K., Melnick A. (2013) Lineage-specific functions of Bcl-6 in immunity and inflammation are mediated by distinct biochemical mechanisms. Nat. Immunol. 14, 380–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gaarenstroom T., Hill C. S. (2014) TGF-β signaling to chromatin: how Smads regulate transcription during self-renewal and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 32, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mullen A. C., Orlando D. A., Newman J. J., Lovén J., Kumar R. M., Bilodeau S., Reddy J., Guenther M. G., DeKoter R. P., Young R. A. (2011) Master transcription factors determine cell-type-specific responses to TGF-β signaling. Cell 147, 565–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kidder B. L., Palmer S. (2010) Examination of transcriptional networks reveals an important role for TCFAP2C, SMARCA4, and EOMES in trophoblast stem cell maintenance. Genome Res. 20, 458–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bégay V., Smink J., Leutz A. (2004) Essential requirement of CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins in embryogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9744–9751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fan Z., Yamaza T., Lee J. S., Yu J., Wang S., Fan G., Shi S., Wang C. Y. (2009) BCOR regulates mesenchymal stem cell function by epigenetic mechanisms. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1002–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]