Abstract

Objective

To develop and test a post-abortal contraception counseling intervention using motivational interviewing (MI), and to determine the feasibility, impact, and patient acceptability of the intervention when integrated into an urban academic abortion clinic.

Study design

A single-session post-abortal contraception counseling intervention for young women aged 15–24 incorporating principles, skills, and style of MI was developed. Medical and social work professionals were trained to deliver the intervention, their competency was assessed, and the intervention was integrated into the clinical setting. Feasibility was determined by assessing ability to approach and recruit participants, ability to complete the full intervention without interruption, and participant satisfaction with the counseling.

Results

We approached 90% of eligible patients and 71% agreed to participate (n=20). All participants received the full counseling intervention. The median duration of the intervention was 29 minutes. Immediately after the intervention and at the one-month follow-up contact, 95% and 77% of participants reported that the session was helpful, respectively.

Conclusions

MI counseling can be tailored to the abortion setting. It is feasible to train professionals to use MI principles, skills, and style and to implement an MI-based contraception counseling intervention in an urban academic abortion clinic. The sessions are acceptable to participants.

Keywords: Motivational interviewing, contraception, abortion, adolescents, contraception counseling, counseling intervention

1. Introduction

In the United States, 21–27% of women who have an abortion experience a repeat pregnancy within 12 months, and repeat abortion incidence is 11–15% within 1–3 years[1, 2]. Although many women presenting for abortion have decided on a method of contraception and do not consider themselves in need of counseling[3], two-thirds of women who present for abortion desire a contraceptive method at their visit and believe that it is an appropriate time to discuss contraception[4]. For those women who do desire counseling or want to leave the abortion visit with a contraceptive method, patient-centered and effective counseling interventions are needed.

Relatively few trials have examined contraception counseling at the time of abortion, and most have not shown an increase in contraceptive uptake[5, 6]. However, these trials may have been limited by their lack of attention to a theoretical basis for the counseling intervention. Given the challenge of adopting new behaviors, behavioral theory-based, tailored approaches to contraception counseling may be important additions to educational interventions.

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based counseling approach defined as “a client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence[7].” MI relies on a therapeutic and collaborative relationship between counselor and patient, respect for autonomy, deep empathic understanding, and exploration of ambivalence without prejudice or coercion. While MI is not a theory, the MI counseling style was developed based on the tenets of established behavioral theories such as Social Cognitive Theory[8], Discrepancy Theory[9, 10], Decision Theory[11], Self-Perception Theory[12], and Self-Determination Theory[13, 14]. The four key principles of MI include: (1) express empathy, (2) develop discrepancy if it exists, (3) roll with resistance, and (4) support self-efficacy. These principles foster a collaborative and non-coercive approach that is well-suited to the preference-sensitive nature of contraceptive choice. The expression of empathy is key to the relational component of MI, in which the counselor strives to establish an empathic understanding of the patient’s experience through the skillful use of reflective listening and non-judgmental acceptance of the patient’s position, including her ambivalence. It is through the non-judgmental exploration of this ambivalence that the patient is able to examine her own arguments for change, change that can be further motivated if there is discrepancy between present behavior and personal goals and values. In this process, the patient is seen as the primary resource in identifying any existing discrepancy, as well as the primary resource in finding answers and solutions when needed. The counselor avoids arguing for change and recognizes that resistance, as a normal part of ambivalence, is only strengthened when opposed. Additionally, resistance may also be an expression that no change in behavior is required. Support for the patient’s self-efficacy and her autonomy enhances the person’s belief in the possibility of change, which is an important motivator. At its core, MI recognizes that people are “the undisputed experts on themselves”[15].

MI has been successfully applied to address an array of health-related behaviors, including improvement in weight loss, blood pressure control, substance use, and for contraception use[16–18]. Additionally, MI lends itself to single-session interventions, which may be more feasible than longer or multi-visit interventions in healthcare settings[16, 19]. However, MI has not been studied for contraception counseling at the time of abortion. In the specific context of post-abortion contraception counseling, MI seeks to establish a supportive and empathic relationship in which to elicit the patient’s life goals and values, to identify contraception options that are consistent with those goals and values, and to explore and resolve any ambivalence among those choices.

This paper describes the development of, counselor training for, and feasibility testing of an MI-based contraception counseling intervention to help young women utilize effective contraception after abortion.

2. Materials and methods

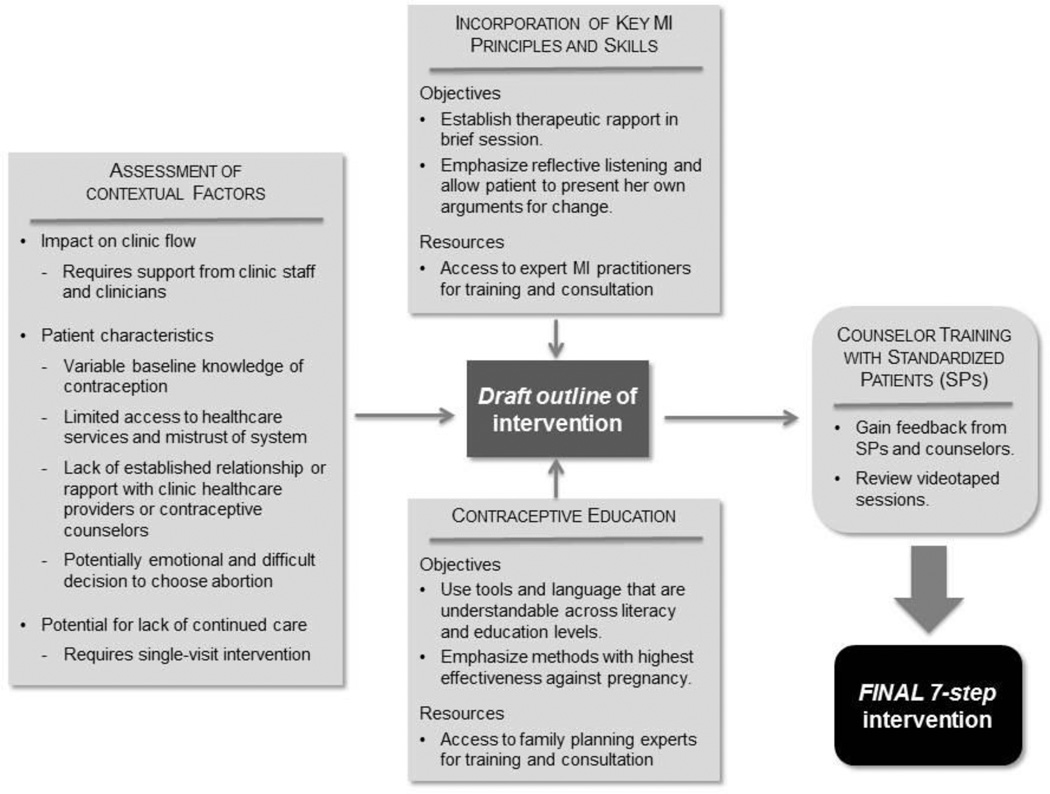

We developed a seven-step, post-abortal contraception counseling intervention incorporating MI principles, skills, and spirit. We paid particular attention to adapting the intervention to the physical, social, and therapeutic environment of the clinical setting and attending to issues of limited education and health literacy among the patient population (Figure). The seven steps to be performed during the counseling intervention were outlined in a two-page guide provided to each counselor. The contraception education component of the intervention used a pictorial guide to contraception adapted from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and World Health Organization (WHO)[20], in which contraceptive methods are organized in tiers based on their level of effectiveness. Counselors emphasized the effectiveness of the top two tiers, noting that 2nd tier methods (e.g. combined hormonal contraceptives) require regular action to maintain effectiveness. Although order of initial discussion of methods was organized by effectiveness, participant preferences for contraceptive characteristics other than effectiveness were acknowledged and incorporated into the intervention. While the “directive” nature of MI is reflected in that the intervention was designed to encourage uptake of highly effective contraception after the abortion procedure, participant preference, even if that preference was for non-use of contraception or avoidance of perceived contraceptive inconvenience or side effects, was valued and respected.

Figure.

Development of the motivational interviewing (MI) intervention

Four health care professionals completed training to deliver the single-session counseling intervention; three were evaluated for competency. The fourth counselor left the institution before skills were assessed. Due to cost constraints, it was neither feasible to train more than four counselors nor to train a new counselor after the fourth counselor left the institution. Of those evaluated, two were physicians (AW and EW) and one was a social work student (AT). None had prior experience using MI. The training program was designed and implemented by co-investigator MQ. Initial training included two 3-hour sessions of instruction on the theory and spirit of MI, evidence for its efficacy, videotaped and live demonstrations of MI counseling, and role-play with feedback to practice MI skills, including (1) reflective listening; (2) avoidance of confrontation; and (3) collaborative, open discussion of the pros and cons of contraceptive methods[7].

The training then included five hours of encounter and feedback utilizing professional standardized patients with the University of Chicago Simulation Center. We videotaped MI-based counseling sessions, each lasting approximately 20 minutes, with the trainees and four different standardized patients to evaluate for MI proficiency, to provide individual, case-based feedback to trainees, and to assess areas in which the intervention outline could be changed or improved. Two investigators (MQ and AW) independently evaluated and graded counselors on the full length of all four videotaped sessions using the Global Scores on the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Scale[21]. MITI is a validated observation scale designed to rate fidelity to 5 dimensions of MI: (1) evocation – focus on eliciting and expanding client’s own reasons for change, (2) collaboration – fostering collaboration and power-sharing between two equal partners, (3) autonomy/support – support and foster client choice, (4) direction – maintain appropriate focus on target behavior, and (5) empathy – make an effort to grasp the client’s perspective and feelings. Each dimension was graded on a behaviorally-anchored 5-point scale; the threshold for competency was a mean score of 4 across the 5 dimensions [21]. We did not code behavior counts because the Global Scores assess the spirit of MI, and a separate viewing of the sessions to allow behavior counts would limit the reproducibility of the training process. Agreement between evaluators was analyzed using percent agreement. The standardized patients also provided written qualitative feedback to counselors, and an experienced MI trainer (MQ) reviewed the videos with counselors to further develop their skills.

We used qualitative information gained from training to further revise the intervention (Table 1) for use in a feasibility study at an urban academic abortion clinic. Inclusion criteria were: English-speaking, presenting for abortion, and aged 15 to 24 years. Exclusion criteria included: maternal medical or fetal indications for abortion, pregnancy resulting from sexual assault, or desired pregnancy within 6 months. Clinic staff referred interested patients to a study investigator, who confirmed eligibility and obtained written informed consent. At enrollment, participants completed a written baseline questionnaire including which contraceptive methods they were considering for use post-abortion. One of the three counselors who passed the competency testing described above then performed the MI-based counseling intervention in a private setting, prior to the abortion procedure. Afterward, participants completed a confidential questionnaire to assess their opinion of the intervention and then returned to routine clinic flow, including non-standardized contraception counseling and provision of the contraceptive method by the clinic provider. We used the electronic medical record to identify contraceptive method choice. We contacted participants via telephone one-month post abortion to reassess the counseling intervention and contraceptive method. For follow-up, we made up to three attempts via telephone, two via e-mail (when available), and one via regular United States Mail.

Table 1.

Steps of the intervention

| Step* | Primary MI principle** and dimension*** |

|---|---|

1. Establish Rapport

|

Principle:

|

Dimension:

|

|

2. Set the agenda

|

Principle:

|

Dimensions:

| |

3. Ask permission to give information about contraceptive methods

|

Principle:

|

Dimensions:

| |

4. Discuss prior contraception use

|

Principles:

|

Dimensions:

| |

| 5. Assess importance, confidence, and readiness to use contraception, using 10-point Likert-like rulers described by Miller and Rollnick [10]. | Principles:

|

Dimensions:

|

|

6. Continued conversation about very effective contraception

|

Principles:

|

Dimensions:

| |

7. Wrap-up

|

Principle:

|

Dimensions:

|

Feasibility was evaluated by (1) assessing ability to approach patients and recruit participants, (2) ability to complete the full intervention without interruption, and (3) participant self-reported satisfaction with and utility of the counseling intervention. We also explored contraceptive outcomes by measuring intended contraceptive method at the abortion visit. Intended method was used instead of immediate method use, because depot medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, implants, and IUDs were not always immediately available after abortion due to logistic and financial constraints in the clinic that were unrelated to this study.

The study was designed as a feasibility study. Thus, determination of sample size was not based on a priori assumptions of effect size or statistical analysis. We determined sample size of 20 participants based on what was deemed to be adequate to determine if it was feasible to integrate the intervention into a clinical setting. Descriptive statistics were used for baseline data and for study outcomes. All analyses were carried out in STATA, version 11.2 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The Institutional Review Board of the Biologic Sciences Division of The University of Chicago approved all study procedures and granted a waiver of parental consent for minors.

3. Results

Inter-rater percent agreement between reviewers of the videotaped counselor training sessions was 68%. All three counselors who were graded passed the competency assessment. Mean scores for adherence across the five MI dimensions were all greater than 4 on the 5-point scale (range: 4.1 – 4.4). Feedback from the standardized patients as well as MI trainees was used to modify the intervention (Table 1). For example, the intervention was better received by the standardized patients when counselors expressed interest about, and subsequently demonstrated knowledge regarding, the patient’s social and medical history. Thus, the first step of the intervention, “establish rapport,” was expanded to allow more time for the patient to discuss her current life situation.

The feasibility study was conducted from July to November 2012. During that time, 31 eligible women presented to the clinic, and 20 of those women were recruited into the study. Of those eligible, 90.3% (28/31) were approached for recruitment, with the additional three patients not approached per clinician request. Of the remaining 28 patients, 20 (71.4%) chose to participate. The mean age of participants was 21 years (range 16–24), and 20% were teens (aged 16–19 years) (Table 2). Almost half (45%) were Black, non-Hispanic, and three-quarters were single and not living with a partner. All rated the importance of avoiding another pregnancy in the next year as a 7 or higher on a 0–10 Likert-like scale. All 20 participants completed the full counseling intervention without interruption; median counseling time was 29 minutes. All participants reported that the intervention was helpful in general, and 19 participants (95%) stated that the intervention helped them select a contraceptive method; 19 (95%) would recommend it to a friend. After the intervention, 12 women (60%), intended to use a LARC method and seven (35%) intended to use a 2nd tier method (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics – Feasibility study

| Characteristic | N = 20 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | 21 ± 2.4 |

| Range | 16–24 |

| Teens (15–19 years old) | 4 (20%) |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 4 (20%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9 (45%) |

| Hispanic | 6 (30%) |

| Other | 1 (5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single, not living with partner | 15 (75%) |

| Single, living with partner | 3 (15%) |

| Ever married | 2 (10%) |

| Annual income | |

| <$10,000 | 10 (50%) |

| $10,000 – 30,000 | 7 (35%) |

| >$30,000 | 3 (15%) |

| Education | |

| In high school | 2 (10%) |

| Did not complete high school | 3 (15%) |

| Completed high school or GED | 6 (30%) |

| Some college | 6 (30%) |

| College degree or above | 3 (15%) |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Public | 7 (35%) |

| Private | 8 (40%) |

| None | 5 (25%) |

| Gestational age at abortion (weeks) | |

| Median (range) | 10.8 (5.6 – 21.4) |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparous | 10 (50%) |

| Parous | 10 (50%) |

| Prior abortion | 4 (20%) |

| Importance: avoiding pregnancy in next year* | |

| 10 / 10 | 18 (90%) |

| 7–9 / 10 | 2 (10%) |

| Most effective post-abortion contraception considered (prior to counseling session) | |

| LARC method | 10 (50%) |

| DMPA | 2 (10%) |

| Combined hormonal method | 6 (30%) |

| Condom | 1 (5%) |

| Undecided | 1 (5%) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Self-reported importance was rated on a 0–10 scale, with 0 = “not at all important” and 10 = “extremely important.”

LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptive

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

Table 3.

Outcomes of feasibility study

| Abortion visit | N = 20 |

| Time of intervention (minutes) | |

| Median (range) | 29 (15–50) |

| Interquartile range | 25–41 |

| Participant confidential feedback immediately after the session:* | |

| Counseling intervention was helpful | 20 (100%) |

| Counseling intervention helped me decide on a method | 19 (95%) |

| Would recommend counseling intervention to a friend | 19 (95%) |

| Intended contraceptive method choice post-abortion:** | |

| Long-acting reversible contraceptive method | 12 (60%) |

| Combined hormonal method | 6 (30%) |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1 (5%) |

| Emergency contraception only | 1 (5%) |

| One-month follow-up | N = 13 |

| Participant feedback: | |

| Counseling intervention was helpful | 12 (92%) |

| Counseling intervention helped me decide on a method | 10 (77%) |

| Would recommend counseling intervention to a friend | 13 (100%) |

| Felt comfortable participating in research while waiting for abortion | 12 (92%) |

| Felt pressured to participate | 0 (0%) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Answers were considered affirmative if participant rated a statement as a 4 (“Agree”) or 5 (“Strongly Agree”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Assessed from the electronic medical record.

Fourteen women (70%) were contacted for follow up, and 13 answered questions about the session. Twelve (92%) reported that the intervention was helpful, and ten (77%) stated it helped them select a method. Twelve participants (92%) reported that they felt comfortable participating in research while waiting to have their abortion procedure, and none reported feeling pressured to participate (Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study describes development of an MI-based post-abortal contraception counseling intervention, counselor training and a feasibility study of the intervention. It makes a number of important contributions to the literature. First, we demonstrate how MI-based contraception counseling can be tailored to the abortion setting as a single-session intervention. By using a broad framework for the intervention rather than strict adherence to a script or educational tool, the intervention allowed counselors to develop a collaborative relationship with the participant and tailor the intervention according to her experiences, attitudes, and priorities. MI’s emphasis on patient autonomy, non-judgmental approach to ambivalence, and partnership between counselor and patient may represent an excellent framework for approaching the preference-sensitive and highly personal nature of contraception counseling. MI has a growing presence in theory-based research in obstetrics and gynecology, and has shown some success in studies of contraception counseling[18, 22]. In a Cochrane review of theory-based interventions for contraception, two of three studies involving face-to-face MI sessions showed improvement in use of effective contraception[18, 23–25]. Studies reviewed that used MI via telephone or computer texting did not show benefit [26, 27], suggesting the importance within MI of establishing a face-to-face therapeutic relationship between counselor and patient.

Although we designed this intervention before the publication of the 3rd edition of Miller and Rollnick’s definitive textbook on MI, our intervention is consistent with their newly described steps for an MI-based session: engage, focus, evoke, and plan[15]. Our first step to establish rapport, establishes engagement between the counselor and the patient. The counselor then focuses the session in the next steps of setting the agenda and asking permission to give information about contraceptive methods. The challenging step of evocation is accomplished during the discussion of past methods used and the ruler exercise, as well as during the continued discussion of contraception. Finally, the wrap-up is when the patient plans how to use the contraceptive method she has chosen.

For this study of MI at the time of abortion, all counselors were effectively trained using our protocol as assessed by the MI competency assessment. In our clinical study, we demonstrated that it is feasible to implement an MI-based contraception counseling intervention at an urban academic abortion clinic. Addressing our first measure of feasibility, approaching patients and recruiting participants, we were able to approach the majority of women for recruitment, and almost three-quarters chose to participate. For the second measure of feasibility, ability to complete counseling sessions, no sessions ended prematurely due to request by the participant or clinic provider, despite the fact that a quarter of sessions were over 40 minutes in duration. Our final measure of feasibility, participant response to the intervention, also demonstrated a positive outcome: the intervention was well-received, with almost all participants reporting that it was helpful and that they would recommend it to a friend.

There are several important limitations in the generalizability of this intervention development and counselor training protocol. Many clinics providing abortion services employ non-professionally trained staff to educate patients about both the abortion procedure itself and about contraceptive options. Our three counselors all had baseline professional training in medicine or social work, although not specifically in using MI. Additionally, the study PI participated both as a counselor and a training evaluator. Another important limitation is the cost of using videotaped standardized patients in training and evaluation of trainee competence, which may limit replication in large clinics with a high staff turnover and limited resources for staff training. Future research will involve training lay counselors and using less formalized and costly methods for role-play and skill practice[28, 29]. Additionally, the length of the intervention in the feasibility study may make implementation in a busy clinic challenging, and there was wide variability in intervention time. This variability was likely due to differences in baseline participant knowledge and concerns. We did not approach 9% of eligible women due to clinician request, possibly due to concern that the length of the intervention would disrupt clinical activities. Balancing effective, patient-centered contraception counseling within the constraints of efficient flow in a busy abortion clinic is an important consideration. While future study may benefit from more attention to the timing of the intervention to minimize disruption, we acknowledge that for some women, a longer intervention may be necessary.

Although designed to encourage uptake of any highly effective method, not LARC specifically, a notable 60% of our participants intended to use a LARC method, including three who had not considered using one of these methods prior to the intervention. Due to the small study size, definitive conclusions cannot be made regarding the study’s contraceptive outcomes. Additionally, because we analyzed intended contraception use rather than actual use, our data is susceptible to social desirability bias in that participants may have viewed contraception use, especially use of highly effective methods, as the most favorable response. However, we ascertained intended method use from the medical record, as reported to clinicians who were not involved in the study, which should decrease the impact of social desirability bias. Overall, these data suggest that women are willing to use effective methods of contraception after abortion and that an MI-based contraception counseling approach holds promise for increasing contraception uptake after abortion.

Implications for practice

Many women who undergo abortion want to receive contraception counseling. Yet, results to date have shown limited effect of contraception counseling on method uptake. As the availability of methods at the time of abortion increases, patient-centered collaborative counseling is critical. Incorporating established theoretical frameworks and skills to influence behavior change has been largely unexplored in the realm of contraception counseling. The use of MI in contraception counseling may be an appropriate and effective strategy for increasing use of contraception after abortion. This study demonstrates that this patient-centered, directive and collaborative approach can be developed into a counseling intervention that can be integrated into an abortion clinic.

Implications.

The use of motivational interviewing in contraception counseling may be an appropriate and effective strategy for increasing use of contraception after abortion. This study demonstrates that this patient-centered, directive and collaborative approach can be developed into a counseling intervention that can be integrated into an abortion clinic.

Acknowledgements

None.

Support: Funded by National Institutes of Health Grant 5 K23 HD067403. The NIH played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Goodman S, Hendlish SK, Reeves MF, Foster-Rosales A. Impact of immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine contraception on repeat abortion. Contraception. 2008;78:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madden T, Westhoff C. Rates of follow-up and repeat pregnancy in the 12 months after first-trimester induced abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:663–668. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195dd1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matulich M, Cansino C, Culwell KR, Creinin MD. Understanding women's desires for contraceptive counseling at the time of first-trimester surgical abortion. Contraception. 2014;89:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavanaugh ML, Carlin EE, Jones RK. Patients' attitudes and experiences related to receiving contraception during abortion care. Contraception. 2011;84:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langston AM, Rosario L, Westhoff CL. Structured contraceptive counseling--a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira AL, Lemos A, Figueiroa JN, de Souza AI. Effectiveness of contraceptive counselling of women following an abortion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14:1–9. doi: 10.1080/13625180802549970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychological review. 1987;94:319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Draycott S, Dabbs A. Cognitive dissonance 2: A theoretical grounding of motivational interviewing. The British journal of clinical psychology / the British Psychological Society. 1998;37(Pt 3):355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janis IL, Mann L. Coping with Decisional Conflict. Am Sci. 1976;64:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bem DJ. Self-Perception - an Alternative Interpretation of Cognitive Dissonance Phenomena. Psychological review. 1967;74:183. doi: 10.1037/h0024835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deci EL, Ryan RM. The Support of Autonomy and the Control of Behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1987;53:1024–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2012;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing : helping people change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37:768–780. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez LM, Tolley EE, Grimes DA, Chen M, Stockton LL. Theory-based interventions for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7(8) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007249.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comparing Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods. US Agency for International Development and World Health Organization. [Last accessed February 5, 2015];2007 http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadl061.pdf.

- 21.Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W, Ernst D. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) [Last accessed February 6, 2015]; http://www.motivationalinterview.org/Documents/miti3_1.pdf. Revised January 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:243–246. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181964254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, et al. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceperich SD, Ingersoll KS. Motivational interviewing + feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-exposed pregnancy risk among college binge drinkers: determinants and patterns of response. J Behav Med. 2011;34:381–395. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen R, Albright J, Garrett JM, Curtis KM. Pregnancy and STD prevention counseling using an adaptation of motivational interviewing: a randomized controlled trial. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:21–28. doi: 10.1363/3902107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirby D, Raine T, Thrush G, Yuen C, Sokoloff A, Potter SC. Impact of an intervention to improve contraceptive use through follow-up phone calls to female adolescent clinic patients. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42:251–257. doi: 10.1363/4225110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnet B, Liu J, DeVoe M, Duggan AK, Gold MA, Pecukonis E. Motivational intervention to reduce rapid subsequent births to adolescent mothers: a community-based randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:436–445. doi: 10.1370/afm.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dewing S, Mathews C, Schaay N, Cloete A, Simbayi L, Louw J. Improving the counselling skills of lay counsellors in antiretroviral adherence settings: a cluster randomised controlled trial in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evangeli M, Longley M, Swartz L. No reductions and some improvements in South African lay HIV/AIDS counsellors' motivational interviewing competence one year after brief training. AIDS care. 2011;23:269–273. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]