Abstract

Two linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates (MICs, 8 μg/ml) from unique patients of a medical center in New Orleans were included in this study. Isolates were initially investigated for the presence of mutations in the V domain of 23S rRNA genes and L3, L4, and L22 ribosomal proteins, as well as cfr. Isolates were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (just one band difference), and one representative strain was submitted to whole-genome sequencing. Gene location was also determined by hybridization, and cfr genes were cloned and expressed in a Staphylococcus aureus background. The two isolates had one out of six 23S rRNA alleles mutated (G2576T), had wild-type L3, L4, and L22 sequences, and were positive for a cfr-like gene. The sequence of the protein encoded by the cfr-like gene was most similar (99.7%) to that found in Peptoclostridium difficile, which shared only 74.9% amino acid identity with the proteins encoded by genes previously identified in staphylococci and non-faecium enterococci and was, therefore, denominated Cfr(B). When expressed in S. aureus, the protein conferred a resistance profile similar to that of Cfr. Two copies of cfr(B) were chromosomally located and embedded in a Tn6218 similar to the cfr-carrying transposon described in P. difficile. This study reports the first detection of cfr genes in E. faecium clinical isolates in the United States and characterization of a new cfr variant, cfr(B). cfr(B) has been observed in mobile genetic elements in E. faecium and P. difficile, suggesting potential for dissemination. However, further analysis is necessary to access the resistance levels conferred by cfr(B) when expressed in enterococci.

INTRODUCTION

Linezolid resistance remains rare among clinical isolates from global surveillance programs (1, 2). Among isolates exhibiting linezolid-nonsusceptible results, alterations in the 23S rRNA genes remain responsible for the majority of the resistance mechanisms observed (2). Mutations in the L3 and L4 ribosomal proteins were demonstrated to cause decreased susceptibility to linezolid (3, 4). In fact, alterations in these ribosomal proteins are currently often observed among staphylococcal isolates, especially among coagulase-negative staphylococci, demonstrating a shift in the epidemiology of linezolid-nonsusceptible isolates and associated resistance mechanisms (2). Efflux-pump mechanisms have also been implicated as a linezolid resistance mechanism (5), and a plasmid-mediated gene (transferable) was recently described (6).

A plasmid-encoded linezolid resistance mechanism, namely, cfr, was reported in human specimens (7). Cfr belongs to the radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) family of enzymes that mediate transfer of methyl residue to unactivated C-H bonds. Cfr methylates the unreactive C2- and C8-carbon atoms on the A2503 residue located in a functionally critical region of the 23S rRNA component (8). The methylation at C8 protects the Cfr-producing bacteria from the action of five major classes of antibiotics, namely, phenicols, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, macrolides, and streptogramin A compounds (PhLOPSA phenotype) (9). Furthermore, it has been proposed that the cfr gene evolved from the naturally occurring rlmN methyltransferase (10), which is widely distributed in several organisms (11).

The gene encoding Cfr was initially observed in Staphylococcus sciuri from calves (12) and other staphylococcal species from animal and human origins from the United States, Italy, China, Canada, India, and Brazil (13–17). Moreover, the cfr gene has been reported in a variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates (18). However, reports of cfr among enterococcal isolates of human origin have remained sporadic (19–22). Recently, Marin et al. reported a cfr-like gene in seven Peptoclostridium (previously Clostridium) difficile isolates recovered from human clinical specimens (23). However, the resistance phenotype conferred by the cfr-like gene remained to be investigated (23, 24). Here, we report the characterization and genetic context of this cfr variant recently reported in P. difficile that was detected in two human clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium from a medical center in New Orleans (1, 25). Our analysis showed that the complete encoded protein variant had approximately 75% amino acid identities with the Cfr protein commonly found in staphylococci and enterococci (12, 20, 26), and this variant was assigned the name Cfr(B).

(Part of these data was presented at the 115th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, New Orleans, LA, May 2015 [27].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

E. faecium clinical isolates included in this study were isolated in a medical site in New Orleans and submitted to a central monitoring laboratory (JMI Laboratories, North Liberty, IA), as part of the 2012 to 2013 SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Species identification and initial susceptibility testing were performed by the use of a MicroScan WalkAway system (Dade Behring, Inc. Sacramento, CA) by the submitting site. Identification was confirmed by the central laboratory using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Confirmation of the initial susceptibility profile and interpretation was carried out by broth microdilution according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations (28, 29). Validation of the MIC values was performed by concurrent testing of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212.

Detection of linezolid resistance mechanisms.

Isolates that showed elevated MIC results for linezolid (i.e., an MIC of ≥4 μg/ml) were selected for further characterization at the central laboratory. Presence of cfr, mutations in 23S rRNA, and ribosomal proteins (L3, L4, and L22) were investigated by PCR and sequencing of amplicons on the two strands, as previously described (13, 30). 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein sequences obtained were compared to those from wild-type E. faecium ATCC 35667 using the Lasergene software package (DNAStar, Madison, Wisconsin).

Epidemiology typing.

E. faecium isolates were epidemiologically typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using genomic DNA prepared in agarose blocks, digested with SmaI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA) and resolved in the CHEF-DR II apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). Results were analyzed by GelCompar II software (Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed according to instructions on the website efaecium.mlst.net.

Gene location.

Genomic DNA was prepared in 1% agarose blocks and digested separately with S1 nuclease (partial digest), I-CeuI, SmaI, and EcoRI. DNA fragments were resolved by PFGE using CHEF-DR II and transferred to nylon membranes. Membranes were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled cfr-specific probe (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) (26).

Whole-genome sequencing and genetic environment of the cfr variant.

Genomic DNA, extracted using the QIAamp genomic DNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), was used to prepare paired-end TrueSeq library and cluster generation. Samples were sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq instrument (SeqWright, Houston, TX, USA). Sequences were aligned into multiple contigs using Lasergene NGen de novo assembly protocol (DNAStar, Madison, WI). Contigs were searched for cfr-like genes and their surrounding sequences. In silico analysis was also performed to investigate the presence of other antimicrobial resistance markers (i.e., erm, mef, tet, van, and aminoglycoside-modifying genes) and additional genetic analysis.

Cloning and expression of the cfr variant.

The cfr-like gene investigated here and that from plasmid pSCFS3 (EMBL accession number AM086211) (9, 17, 26) were amplified using High-Fidelity PCR master mix and cloned into the PCRII-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Ligation reactions were transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 electrocompetent cells (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and selected on nutrient agar plates containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin. The recombinant PCRII-TOPO plasmids and the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pEPSA5 were extracted using a Qiagen plasmid miniprep kit. Double digests using BamHI and XbaI were performed, and cfr inserts were ligated into pEPSA5 using T4 DNA ligase. Ligation mixtures were transformed into E. coli NEB5α electrocompetent cells (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). Transformants were selected in 50 μg/ml ampicillin. Plasmid preparations containing the recombinant shuttle vector pEPSA5 carrying the cfr genes were electroporated into S. aureus RN4220. Transformants were selected on 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and the presence of cfr was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Nomenclature of the cfr variant.

The cfr-like gene and deduced protein sequences were submitted to Marilyn Roberts (Washington State University, WA, USA) and the new variant designated cfr(B) (24).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

cfr(B) and its adjacent regions were submitted to the EMBL database and deposited under the accession number KR610408.

RESULTS

Patient histories.

A 56-year-old male from south Louisiana received a kidney-pancreas transplant 2 years earlier (2010) with associated immunosuppression. Other pertinent past medical history includes a splenectomy and partial liver resection following a motor vehicle accident. In September 2011, he received linezolid therapy (600 mg orally [p.o.] twice a day [b.i.d.], length of time unknown) to treat right-sided mastoiditis. In February 2012, he developed septic shock secondary to Fournier's gangrene and was treated with vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and surgical debridement. In March 2012, he was hospitalized for diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. An exploratory laparotomy resulted in small bowel resection for perforation. Initial treatment included vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and fluconazole. Cultures of the peritoneal fluid grew Peptostreptococcus spp., Klebsiella spp., vancomycin- and linezolid-resistant E. faecium (18203R), and Candida glabrata. The patient was treated with micafungin, metronidazole, and ciprofloxacin until discharged. The patient was also diagnosed with orchitis and upon discharge, doxycycline at 100 mg p.o. b.i.d. was prescribed for 1 month. As of August 2014, the patient was alive and doing well.

A 61-year-old male from south Louisiana being treated for neurosarcoidosis and disseminated Nocardia with a trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole regimen and chronic steroids developed an intra-abdominal abscess in October 2012 that required drainage. Culture of the abscess yielded vancomycin-resistant E. faecium that was susceptible to linezolid. He was treated with linezolid, piperacillin-tazobactam, and ciprofloxacin. He remained on all antibiotics through mid-December. In January 2013, the patient developed fever and was hospitalized. Blood cultures were positive for linezolid-susceptible, vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium. The patient received doripenem and micafungin but continued to have intra-abdominal abscesses requiring drain placement. In March 2013, he remained on doripenem, linezolid, ciprofloxacin, and micafungin (total length of time unknown). In April 2013, blood cultures revealed vancomycin- and linezolid-resistant E. faecium (18961R). He was started on daptomycin and metronidazole but expired in May 2013.

The two patients lived in different towns, but they were inpatients in the same two hospitals and long-term acute care center in the New Orleans area. However, the patients were not hospitalized at the same time.

Susceptibility profile, epidemiology, and linezolid resistance mechanisms.

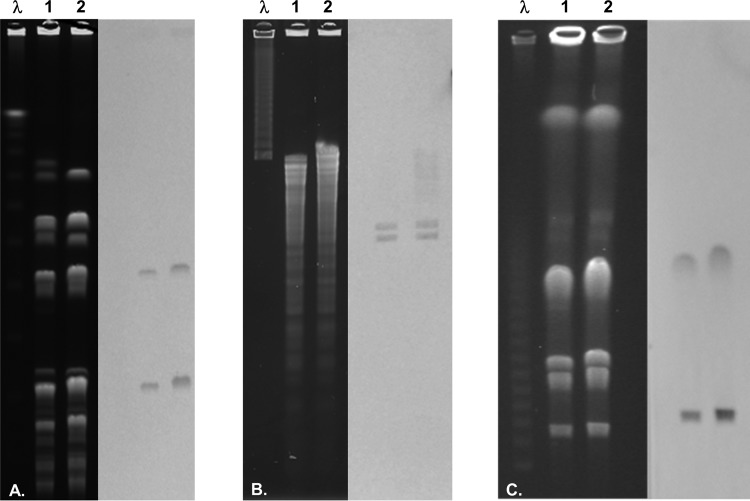

The two E. faecium isolates exhibited elevated MIC results to linezolid, vancomycin, teicoplanin (VanA phenotype), gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline (Table 1). The two isolates were susceptible to doxycycline (MIC, 4 μg/ml) (Table 1). The isolate recovered during the 2012 sampling year displayed resistance phenotypes to erythromycin and clindamycin, while the E. faecium isolate collected during 2013 was susceptible to the two compounds (Table 1). The E. faecium isolates shared highly similar PFGE profiles (one band difference) (Fig. 1A) and were assigned ST794. The two isolates were cfr positive, and one out of six 23S rRNA alleles had a G2576T alteration. Modifications in the L3, L4, and L22 proteins were not observed.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Cfr-producing E. faecium isolated in a New Orleans hospital and S. aureus RN4220 carrying cfr and cfr(B) recombinant plasmids

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) for: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. faecium |

S. aureus |

|||||

| 18203R | 18961R | RN4220 | RN4220(pEPSA5) | RN4220(pEPSA5-cfr)a | RN4220(pEPSA5-cfr(B))b | |

| Linezolid | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | >64 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 16 | 16 |

| Erythromycin | >64 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 4 | 4 | 64c | 128 | 128 |

| Retapamulin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4 | 4 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 |

| Virginiamycin | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 |

| Ampicillin | >8 | >8 | NDd | ND | ND | ND |

| Tetracycline | 32 | 32 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Tigecycline | 0.06 | 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Doxycycline | 4 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Vancomycin | >16 | >16 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Teicoplanin | >16 | >16 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Daptomycin | 2 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Gentamicin | >8 | >8 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Ciprofloxacin | >4 | >4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

FIG 1.

PFGE of E. faecium genomic DNA digests and Southern blot hybridization with a cfr-specific digoxigenin-labeled probe. (A) SmaI digests; (B) EcoRI digests; (C) ICeuI digests. Lanes λ, 1, and 2 represent lambda DNA molecular marker, E. faecium 18203R, and E. faecium 18961R, respectively.

Characterization of the cfr gene variant, cfr(B), and encoded protein.

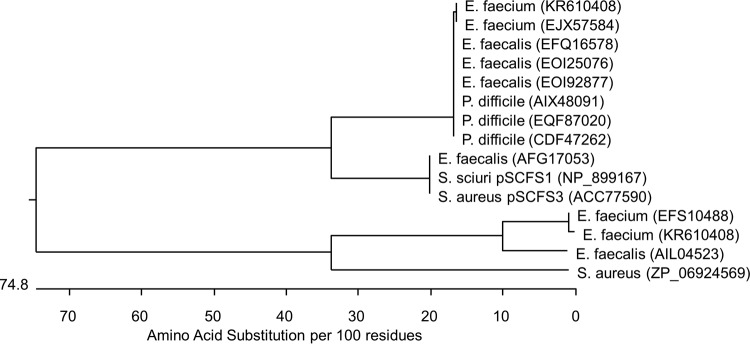

The cfr(B) nucleotide sequence was most similar (99.7%) to those found in P. difficile (GenBank accession numbers KM359438, KM359439, CP003939, HG002389, and HG002396). The Cfr(B) amino acid sequences from the two E. faecium isolates were identical and had only 74.9% amino acid or 72.0% nucleotide identities compared with those of the Cfr proteins and cfr genes carried in plasmids pSCFS1 or pSCFS3 (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). However, the Cfr(B)-encoded protein showed complete identity with 23S rRNA methyltransferase or SAM-dependent methyltransferase described in E. faecium (GenBank accession number EJX74584) or 99.7% with those from E. faecalis (GenBank accession numbers EFQ16578, EOI25076, and EOI92877) and P. difficile (GenBank accession numbers AIX48091, CDF47262, and EQF87020) (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, Cfr(B) showed the conserved amino acid positions that are associated with Cfr and that differentiate it from the intrinsic RlmN (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (11). Compared with examples of the indigenous RlmN, those of Cfr(B) showed approximately 35.0% identity (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Moreover, the cfr and cfr(B) expressed in the S. aureus RN4220 background demonstrated that the two proteins similarly increased the MIC results for linezolid, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, retapamulin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, and virginiamycin (Table 1).

FIG 2.

Evolutionary relationships predicted from the Cfr, Cfr(B), and RlmN sequence alignment. The length of each branch represents the distance between sequences, while the units at the bottom of the tree indicate the number of substitution events. Reference information and accession numbers are given in parentheses here for the following proteins: Cfr(B) (KR610408) from E. faecium strains 18203R and 18961R (this study; USA), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number EFQ16578) from E. faecalis TX0635/WH245 (USA) (37), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number EOI25076) from E. faecalis WH571 (USA) (37), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number EOI92877) from E. faecalis TX0635/WH245 (USA) (37), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number EJX57584) from E. faecium R497 (USA) (38), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number AIX48091) from P. difficile 11107643 (Spain) (23), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number CDF47262) from P. difficile Ox2167 (England) (32), Cfr(B) (GenBank accession number EQF87020) from P. difficile 824 (USA; not available), Cfr (GenBank accession number NP_899167) from S. sciuri (Germany) (39), Cfr (GenBank accession number ACC77590) from S. aureus 737X (USA) (13), RlmN (GenBank accession number AIL04523) from E. faecalis ATCC 29212 (USA; not available), RlmN (GenBank accession number EFS10488) from E. faecium TX0082 (USA) (40), and RlmN (GenBank accession number ZP_06924569) from S. aureus ATCC 51811 (USA) (41).

Location of cfr(B) and genetic context.

PFGE followed by Southern blotting hybridization of I-CeuI digests revealed two signals from the E. faecium isolates (Fig. 1). This was confirmed by additional Southern blotting hybridizations of SmaI and EcoRI digests (Fig. 1), each generating two hybridization signals. S1 nuclease digest blotting did not yield hybridization signals, suggesting the absence of extrachromosomal locations for cfr(B).

The genetic context of cfr(B) included a Tn6218 structure similar to the cfr-carrying transposon described in P. difficile (GenBank accession number HG002396) (Fig. 3) including integrase, excisionase, regulatory proteins, sigma 70 region, and other open reading frames flanked by chromosomal DNA. Only 94 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were observed in the sequence spanning 8,363 nucleotides surrounding the cfr(B) gene compared to that under GenBank accession number HG002396. Among these SNPs, 91 were within the transposase/integrase (int) gene, which translated in 86% identity between the two int genes. In addition, the int gene from E. faecium was identical to that encoding a transposase described in E. faecium under GenBank accession number WP_002350216. The cfr(B)-containing genetic element was inserted in the chromosome in between 16S rRNA pseudouridylate synthase and a bacteriophage integrase. Further in silico sequence analysis demonstrated that E. faecium isolates harbored tet(L), tet(M), aac(6′)-aph(2″), aph(3′)-III, vanA, and erm(B) genes; however, the erm(B) gene in 18961R was disrupted by sasK.

FIG 3.

Schematic representation of DNA sequences (8.4 kb) surrounding cfr(B).

DISCUSSION

Cfr belongs to the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzyme superfamily of proteins, which are widely distributed in nature (11). These proteins have similarities to the Cfr(B) protein described here, and many sequences belonging to this class observed in several bacterial species (e.g., E. faecium, P. difficile, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and Bacillus methylotrophicus) have been deposited in GenBank as putative chloramphenicol-florphenicol-resistance proteins. Similar to Cfr and Cfr(B), three Cfr-like proteins from B. amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus clausii, and Brevibacillus brevis were shown to confer decreased susceptibility to five classes of antibiotics when expressed in E. coli or S. aureus (31).

With rare exceptions, cfr has been plasmid located and surrounded by mobile elements (18, 20, 26). Likewise, cfr(B) was located on a Tn6218 element, the structure of which was published in GenBank (accession number HG002396) and obtained from a P. difficile isolate (Ox2167) collected from a human specimen in 2009 in Oxford, England (32). These results suggest that cfr(B) was incorporated by Tn6218, and this genetic structure was disseminated among E. faecium (this study) and P. difficile (England) isolates and likely among the P. difficile isolates from Spain (23) and other bacterial species yet to be detected. Tn6218 has been detected in other P. difficile clinical isolates (Ox42 [GenBank accession number HG002387] and Ox1485 [GenBank accession number HG002395]); however, these genetic structures lack the cfr or cfr(B) gene. Moreover, the presence of multiple copies of cfr(B) in the E. faecium chromosome (this study) emphasizes the capability of this transposon to mobilize.

It was demonstrated here that Cfr(B) confers a similar phenotype compared to Cfr expressed in an S. aureus background. However, it is tempting to speculate that the same may not be true when Cfr(B) is expressed in an enterococcal background since E. faecium 18961 displayed a low MIC value for clindamycin, and the two isolates showed low MIC results for chloramphenicol. As isolate 18961 had a nonfunctional Erm(B), it would be expected that the clindamycin MIC value would remain elevated due to the production of Cfr(B). Thus, it appears that, at least in isolate 18961, Cfr(B) does not confer the usual PhLOPSA phenotype, which has been previously reported in E. faecalis (33). In addition, the two E. faecium isolates exhibited a linezolid MIC value of 8 μg/ml, which would be consistent with a low number of alleles mutated in 23S rRNA (34). Therefore, further investigations are needed to access the resistance levels conferred by cfr(B) when expressed in enterococci and its possible effect when associated with 23S rRNA mutations.

In summary, this study reports the first detection of cfr genes in E. faecium clinical isolates in the United States and the characterization of a new variant, cfr(B), which was shown to confer a resistance phenotype to several antimicrobial agents similar to that of cfr when expressed in an S. aureus background. The origin of cfr-like genes and their dissemination within several distinct genetic structures remains to be elucidated. Just like the cfr gene detected in several bacterial species from human and animal specimens, cfr(B) has been observed in mobile genetic elements and among at least three bacterial species (i.e., E. faecium, E. faecalis, and P. difficile). Overall, linezolid resistance rates remain low (1, 2, 25, 35, 36); however, sporadic outbreaks and clonal spread of linezolid-resistant Gram-positive isolates remain a threat, highlighting the importance of active surveillance and screening for mobile genes, such as those described here.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following staff members at JMI Laboratories (North Liberty, IA, USA) for technical support and manuscript assistance: J. Oberholser, P. Rhomberg, J. Ross, J. Schuchert, J. Streit, and L. Woosley. We are also grateful to Alex Horswill, University of Iowa, for providing the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pEPSA5.

JMI Laboratories, Inc., received research and educational grants from 2012 to 2014 from Achaogen, Actelion, Affinium, American Proficiency Institute (API), AmpliPhi Biosciences, Anacor, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Basilea, BioVersys, Cardeas, Cempra, Cerexa, Cubist, Daiichi, Dipexium, Durata, Exela, Fedora, Forest Research Institute, Furiex, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Medpace, Meiji Seika Kaisha, Melinta, Merck, MethylGene, Nabriva, Nanosphere, Novartis, Pfizer, Polyphor, Rempex, Roche, Seachaid, Shionogi, Synthes, The Medicines Co., Theravance, Thermo Fisher, VenatoRx, Vertex, Waterloo, Wockhardt, and some other corporations.

Some JMI employees are advisors/consultants for Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer, Cempra, Cerexa-Forest, and Theravance.

With regard to speakers bureaus and stock options, we have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Ochsner Clinic Foundation authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01473-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Hogan PA, Ross JE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2015. In vitro activity of linezolid as assessed through the 2013 LEADER surveillance program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Jones RN. 2014. Linezolid update: stable in vitro activity following more than a decade of clinical use and summary of associated resistance mechanisms. Drug Resist Updat 17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw KJ. 2009. Mutations in ribosomal protein L3 are associated with oxazolidinone resistance in staphylococci of clinical origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5275–5278. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01032-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw KJ. 2009. Novel ribosomal mutations in Staphylococcus aureus strains identified through selection with the oxazolidinones linezolid and torezolid (TR-700). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5265–5274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00871-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Floyd JL, Smith KP, Kumar SH, Floyd JT, Varela MF. 2010. LmrS is a multidrug efflux pump of the major facilitator superfamily from Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:5406–5412. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00580-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Lv Y, Cai J, Schwarz S, Cui L, Hu Z, Zhang R, Li J, Zhao Q, He T, Wang D, Wang Z, Shen Y, Li Y, Fessler AT, Wu C, Yu H, Deng X, Xia X, Shen J. 2015. A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2182–2190. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toh SM, Xiong L, Arias CA, Villegas MV, Lolans K, Quinn J, Mankin AS. 2007. Acquisition of a natural resistance gene renders a clinical strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to the synthetic antibiotic linezolid. Mol Microbiol 64:1506–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Challand MR, Salvadori E, Driesener RC, Kay CW, Roach PL, Spencer J. 2013. Cysteine methylation controls radical generation in the Cfr radical AdoMet rRNA methyltransferase. PLoS One 8:e67979, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long KS, Poehlsgaard J, Kehrenberg C, Schwarz S, Vester B. 2006. The cfr rRNA methyltransferase confers resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2500–2505. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00131-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminska KH, Purta E, Hansen LH, Bujnicki JM, Vester B, Long KS. 2010. Insights into the structure, function and evolution of the radical-SAM 23S rRNA methyltransferase Cfr that confers antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 38:1652–1663. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson GC, Hansen LH, Tenson T, Rasmussen A, Kirpekar F, Vester B. 2013. Distinction between the Cfr methyltransferase conferring antibiotic resistance and the housekeeping RlmN methyltransferase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4019–4026. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00448-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz S, Werckenthin C, Kehrenberg C. 2000. Identification of a plasmid-borne chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance gene in Staphylococcus sciuri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:2530–2533. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2530-2533.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Castanheira M, DiPersio J, Saubolle MA, Jones RN. 2008. First report of cfr-mediated resistance to linezolid in human staphylococcal clinical isolates recovered in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2244–2246. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00231-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bongiorno D, Campanile F, Mongelli G, Baldi MT, Provenzani R, Reali S, Lo Russo C, Santagati M, Stefani S. 2010. DNA methylase modifications and other linezolid resistance mutations in coagulase-negative staphylococci in Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2336–2340. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajan V, Kumar VG, Gopal S. 2014. A cfr-positive clinical staphylococcal isolate from India with multiple mechanisms of linezolid-resistance. Indian J Med Res 139:463–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gales AC, Deshpande LM, de Souza AG, Pignatari AC, Mendes RE. 2015. MSSA ST398/t034 carrying a plasmid-mediated cfr and erm(B) in Brazil. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:303–305. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehrenberg C, Schwarz S. 2006. Distribution of florfenicol resistance genes fexA and cfr among chloramphenicol-resistant Staphylococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1156–1163. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1156-1163.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen J, Wang Y, Schwarz S. 2013. Presence and dissemination of the multiresistance gene cfr in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1697–1706. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Wang Y, Schwarz S, Li Y, Shen Z, Zhang Q, Wu C, Shen J. 2013. Transferable multiresistance plasmids carrying cfr in Enterococcus spp. from swine and farm environment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:42–48. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01605-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz L, Kiratisin P, Mendes R, Panesso D, Singh KV, Arias CA. 2012. Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to linezolid due to cfr in a human clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3917–3922. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Wang Y, Wu C, Shen Z, Schwarz S, Du XD, Dai L, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Shen J. 2012. First report of the multidrug resistance gene cfr in Enterococcus faecalis of animal origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1650–1654. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06091-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SN, Memari N, Shahinas D, Toye B, Jamieson FB, Farrell DJ. 2013. Linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecium isolated in Ontario, Canada. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 77:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marin M, Martin A, Alcala L, Cercenado E, Iglesias C, Reigadas E, Bouza E. 2015. Clostridium difficile isolates with high linezolid MICs harbor the multiresistance gene cfr. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:586–589. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04082-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz S, Wang Y. 2015. Nomenclature and functionality of the so-called cfr gene from Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2476–2477. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04893-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes RE, Flamm RK, Hogan PA, Ross JE, Jones RN. 2014. Summary of linezolid activity and resistance mechanisms detected during the 2012 LEADER surveillance program for the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1243–1247. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02112-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Bonilla HF, Schwarz S, Huband MD, Jones RN, Quinn JP. 2013. Dissemination of a pSCFS3-like cfr-carrying plasmid in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates recovered from hospitals in Ohio. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2923–2928. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00071-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn HP, Deshpande LM, Mendes RE, Ashcraft DS, Pankey G. 2015. Abstr 115th Gen Meet Am Soc Microbiol, abstr 103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard— 10th ed CLSI document M07-A10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 25th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S25. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller K, Dunsmore CJ, Fishwick CW, Chopra I. 2008. Linezolid and tiamulin cross-resistance in Staphylococcus aureus mediated by point mutations in the peptidyl transferase center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1737–1742. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen LH, Planellas MH, Long KS, Vester B. 2012. The order Bacillales hosts functional homologs of the worrisome cfr antibiotic resistance gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3563–3567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00673-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dingle KE, Elliott B, Robinson E, Griffiths D, Eyre DW, Stoesser N, Vaughan A, Golubchik T, Fawley WN, Wilcox MH, Peto TE, Walker AS, Riley TV, Crook DW, Didelot X. 2014. Evolutionary history of the Clostridium difficile pathogenicity locus. Genome Biol Evol 6:36–52. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Wang Y, Schwarz S, Wang S, Chen L, Wu C, Shen J. 2014. Investigation of a multiresistance gene cfr that fails to mediate resistance to phenicols and oxazolidinones in Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:892–898. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobritz M, Hutton-Thomas R, Marshall S, Rice LB. 2003. Recombination proficiency influences frequency and locus of mutational resistance to linezolid in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:3318–3320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3318-3320.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendes RE, Hogan PA, Streit JM, Jones RN, Flamm RK. 2015. Update on the linezolid in vitro activity through the Zyvox Annual Appraisal of Potency and Spectrum program, 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2454–2457. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04784-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendes RE, Hogan PA, Streit JM, Jones RN, Flamm RK. 2014. Zyvox Annual Appraisal of Potency and Spectrum (ZAAPS) program: report of linezolid activity over nine years (2004-12). J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1582–1588. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride SM, Fischetti VA, Leblanc DJ, Moellering RC Jr, Gilmore MS. 2007. Genetic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 2:e582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arias CA, Panesso D, McGrath DM, Qin X, Mojica MF, Miller C, Diaz L, Tran TT, Rincon S, Barbu EM, Reyes J, Roh JH, Lobos E, Sodergren E, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Quinn JP, Shamoo Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. 2011. Genetic basis for in vivo daptomycin resistance in enterococci. N Engl J Med 365:892–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kehrenberg C, Ojo KK, Schwarz S. 2004. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the multiresistance plasmid pSCFS1 from Staphylococcus sciuri. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:936–939. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Murray BE. 2006. Construction of improved temperature-sensitive and mobilizable vectors and their use for constructing mutations in the adhesin-encoding acm gene of poorly transformable clinical Enterococcus faecium strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:334–345. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.334-345.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su YC, Wong AC. 1995. Identification and purification of a new staphylococcal enterotoxin, H. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1438–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.