Abstract

Twenty years ago, the transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) from a mouse to other recipient mice was shown to be feasible, which clearly demonstrated the functional identity of SSCs. Since then, several important new findings and other technical developments have followed, which included a new hypothesis on their cell kinetics and spermatogonial hierarchy in the testis, a culture method allowing their self-renewal and proliferation, a testis tissue organ culture method, which induced their complete differentiation up to sperm, and the in vitro induction of germ cells from embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. These advancements reinforced or advanced our understanding of this unique cell. Nonetheless, there are many unresolved questions in the study of spermatogonial stem cells and a long road remains until these cells can be used clinically in reproductive medicine.

Keywords: in vitro spermatogenesis, male infertility, organ culture

INTRODUCTION

Spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) play a number of pivotal roles in spermatogenesis. Firstly, SSCs are the cells that spermatogenesis starts from. Once SSCs have committed to differentiate, the subsequent cellular processes progress in a strictly ordered manner up to sperm formation in the seminiferous tubules. Secondly, SSCs sustain spermatogenesis throughout life owing to their function as stem cells. In other words, SSCs maintain themselves by self-renewal, which facilitates the continuation of spermatogenesis. Thirdly, disruption of spermatogenesis, whether physiological such as in seasonal breeders or due to pathological insult, can be regulated or restored by SSCs. Along with these roles, SSCs must maintain the integrity of DNA so it can be effectively transmitted to the next generation. Thus, SSCs are not just one type of tissue stem cell, but could be called stem cells ensuring the continuation of life.

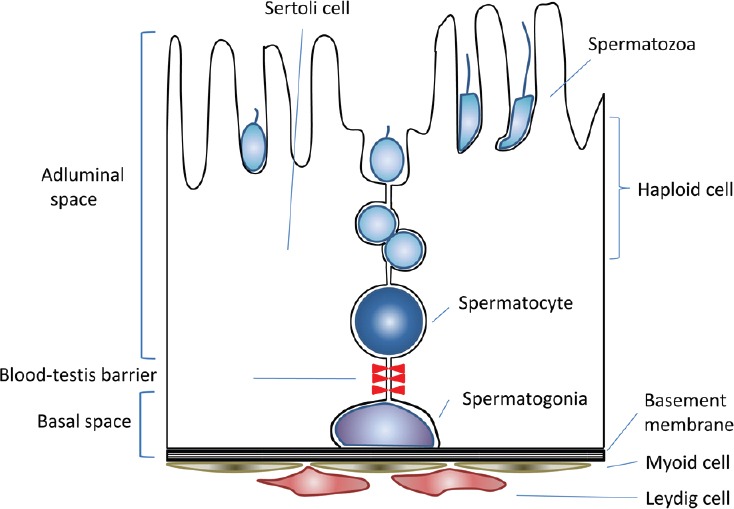

To produce adequate numbers of daughter cells which are destined to undergo the differentiation process of spermatogenesis while maintaining themselves in a certain range as a rather small population, SSCs have to achieve a delicate balance between commitment to differentiation and self-renewal. This balance is maintained not only by SSCs themselves but also requires support from the surrounding somatic cells. In addition to germ cells, the testis contains many different kinds of somatic cells, including Sertoli, Leydig, peritubular myoid and immune cells, as well as vascular cells (Figure 1). Each cycle of spermatogenesis and its sequential progression are made possible by delicate cooperation among these somatic cells. The number of SSCs has been estimated to be as low as 0.03% of all germ cells in the rodent testis.1 This fact, along with the lack of specific markers for identifying them, has hampered the study of SCCs. These difficulties, however, are being overcome with technological advancements in this and related areas of science that have taken place over the last two decades. In this review, we summarize the characteristics of SSCs, give a historical overview and describe recent progress in SSC research, and finally discuss prospects of future research.

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the seminiferous epithelium.

SSCS IN SITU IN THE TESTIS

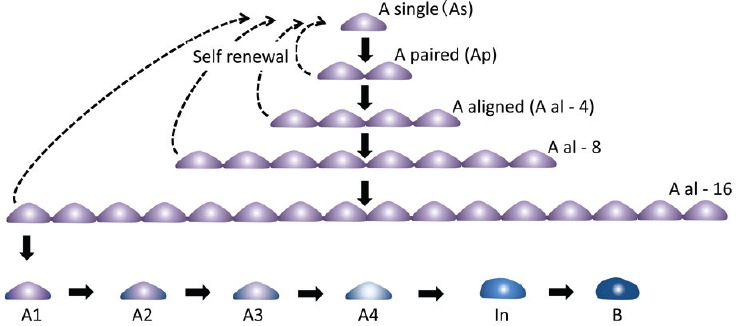

The SSCs along with other spermatogonia reside inside the basal lamina of the seminiferous tubules. In other words, they are considered to be present on a two-dimensional plane. Thus, a whole mount technique, which can provide a view of almost half of the area of the peripheral plane of a seminiferous tubule, is superior for their observation compared to regular histological thin-sectioning. Using this whole mount method, classical studies on spermatogonia were performed to clarify the cell kinetics of spermatogonia, which comprise different subtypes including type A, Intermediate, and B. Based on their numbers, the morphology of the nucleus, especially the amount and appearance of heterochromatin, and mitotic cell cycles, it is clear that the SSCs are a subset of the type A spermatogonia. Among type A spermatogonia, more immature subgroups were classified and collectively named undifferentiated type A spermatogonia. These undifferentiated type A spermatogonia include Asingle (As), Apaired (Apr), and Aaligned (Aal); this classification is based on cyst formation by inter-cellular cytoplasmic bridges (Figure 2). In addition to morphological techniques, studies using3 H-thymidine labeling revealed the unique cell kinetics of these spermatogonia.2 The differentiating spermatogonia undergo synchronous successive cell division based on a fixed schedule, while undifferentiating spermatogonia, especially As and to a lesser extent Apr, are flexible in that regard. The cell cycle length was also different in each group. These data qualitatively distinguished undifferentiated type A spermatogonia from differentiating spermatogonia, which is difficult to do based on morphology alone. Then, along with other data accumulated by morphological observation, the As model was established, proposing that As spermatogonia are the only cells functioning as SSCs in the testis.3,4 Other cells, including Apr and Aal spermatogonia, were considered to have committed to differentiate toward sperm formation. This As model has been regarded as plausible and accepted as a likely hypothesis to establish the identity of SSCs. On the other hand, another mechanism for maintaining the number of stem cells in a particular organ, the niche theory, was proposed in 1978.5 It was later demonstrated in Drosophila gonads that the stem cell niche actually exists and controls the fate of stem cells.6,7,8 Based on these findings, along with the prevailing As model, it was generally assumed that each SSC exists at a particular location on the basal lamina and is responsible for the continuation of spermatogenesis in the surrounding area, at least under stable conditions.

Figure 2.

Schematic view of self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs. Solid and broken arrows indicate differentiation and self-renewal, respectively.

This assumption was challenged in 2007 by a report demonstrating that clones of each SSC fluctuate markedly in size even under a steady state condition.9 To our surprise, the majority of those clones disappear sooner or later and the vacant area left behind is occupied by neighboring clones. Time-lapse observation of GFRα1-positive cells, a receptor of GDNF (explained below) and a marker for the subset of undifferentiated spermatogonia, revealed that they are actively migrating over a large area on the basal lamina and do not stay at a certain point. It was also found that the breakage of inter-cellular bridges took place more often than thought. This means that As spermatogonia are produced by their duplication but also from Apr or Aal spermatogonia by fragmentation. More correctly, it was observed that pure duplication, namely the production of two As by cell division, was rather rare and the majority of As resulted from the fragmentation of Apr and Aal.10 These observations naturally necessitated a new model for the cell kinetics and hierarchy of spermatogonia including SSCs. In fact, the same research group proposed a new biophysical model, which faithfully predicted the fate of GFRα1-positive spermatogonia in not only a steady-state but also in a postinsult regeneration state, by adopting the rates of cell division and fragmentation as parameters.10 Simply put, not only As spermatogonia but also Apr and Aal have the potential to become SSCs and actually work as SSCs in the mouse testis. It appears that SSCs are not a fixed entity but a differentiation state which could be lost or regained according to their physical status, whether they occur singly, are connected with other sibling germ cells, or become free again to be single.

Many critical questions regarding the nature of SSCs remain to be answered. For instance, it is not clear how they are maintained in small populations in the testis which are controlled in a robust and flexible manner. It is true, however, that research on SSCs has been providing and will continue to provide cutting-edge information on the biology of tissue stem cells in general.

IN VITRO PROPAGATION OF SSCS

Now, it is possible to culture and propagate SSCs of mice and some other species. It had been known for many years that germ cells were difficult to culture, so the development of culture systems for these cells was a historic achievement in germ cell biology. We would like to mention that, prior to this achievement, there were two important earlier breakthroughs that significantly contributed to the development of these culture methods: establishment of the spermatogonial transplantation technique (in 1994), and identification of GDNF as a key growth factor for the proliferation of SSCs (in 2000).

In 1994, Ralph L. Brinster and his colleagues reported that testis cells from a donor mouse could be dissociated into single cells and injected in the seminiferous tubules of recipient mice, which were pretreated with busulfan to ablate endogenous spermatogenesis. Certain cells in the injected population, namely SSCs, settled to the basal lamina and formed colonies of spermatogenesis in the seminiferous tubules of host testes.11 The number of the spermatogenic colonies was proportional to the number of cells transplanted and they continued expanding in the subsequent period.12 Thus, this method, called spermatogonial transplantation, became a novel and unique functional assay for SSCs, with each colony in the transplanted testis corresponding to a single SSC or a unit of SSCs. With this method, it became possible to study functional aspects of SSCs, whose identity was still unclear, with no molecular markers available. Following the development of this spermatogonial transplantation method, several important and interesting studies utilizing this method were reported. For instance, surface markers of SSCs were identified using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. The sorted cells were tested by spermatogonial transplantation to determine whether they could form spermatogenic colonies in recipient mouse testes. With this strategy, several surface markers for SSCs were identified, including α6-integrin (CD49f),13,14β1-integrin (CD29),13 Thy1 (CD90)15 and CD9.16 Another interesting advance using the transplantation method was interspecies transplantation. It was shown that rat SSCs could actually develop spermatogenic colonies in mouse testis, while cells of other animals phylogenetically more distant did not form spermatogenic colonies in the mouse testis.17,18

In 2000, the important discovery was reported that glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is key regulatory factor for the self-renewal of SSCs. Transgenic mice which overexpress GDNF showed hyper-proliferation of spermatgonia, while mice with a hemi-defect of GDNF showed spermatogonial depletion.19 This crucial finding soon led to the development of culture medium for the propagation of mouse SSCs in vitro.

In 2003 and 2004, two groups of researchers independently reported a culture method for spermatogonial stem cells using GDNF and other factors in the culture media.20,21 One of them, Shinohara's team, named the cultured SSCs germline stem (GS) cells.20 Mouse GS cells proliferated exponentially and their karyotypic, genetic, and epigenetic states could be stably maintained. The stem cell characteristics of the GS cells were then tested with the transplantation method, which had played a critical role in the identification of SSCs. When GS cells were tested with the transplantation technique, they produced spermatogenic colonies in the recipient testes, which was the only and definite proof of their identity as SSCs. In addition, sperm derived from these transplanted GS cells were functional and normal, producing offspring.

Through studies involving SSC culture along with the transplantation methods, several genes were identified which delineate SSCs. Those include GFRα1 (GDNF family receptor α 1), nanos-2 and -3,22 PLZF (promyelocyte leukemia zinc-finger factor),23 inhibitor of differentiation 4 (Id4),24 and Pax-7,25 which are useful both for identification of SSCs as well as studies of the molecular control of their behavior and functions.

The culture method has been modified and applied to other species, including the rat, hamster, and rabbit, and successfully allowed for propagation of SSCs from these various species.26,27,28,29 Human SSCs have also been tested for in vitro propagation by several researchers. However, up till now, the culture conditions do not seem optimal for their successful maintenance and proliferation. In fact, the medium formulation has not yet been optimized even for mouse GS cells. At present, the factors necessary for successful culture have been reported to be GDNF and FGF2.30 There are reports of trying to improve the culture conditions by modifying the medium formula.

It is known that germ cells are pluripotent because they can give rise to a teratoma or teratocarcinoma. This unique characteristic was initially attributed specifically to primordial germ cells (PGCs). PGCs were also converted to ES-like pluripotent cells, embryonic germ (EG) cells, under culture conditions with Kit ligand, basic fibroblast growth factor, and leukemia inhibitory factor. On the other hand, it was not clear if SSCs also maintain such pluripotent potential. In 2004, it was reported that GS cells were converted to ES-like cells during culturing. This conversion is very rare in practice but has important implications for germ cell carcinogenesis. It is noteworthy that GS cells cannot be converted to iPS cells by Yamanaka factors. There appears to be different kinds of signal transduction machinery or transcriptional compositions which are dominant in the germ cells. Recently, it was reported that the conversion of GS cells to the pluripotent state became highly efficient by down-regulating Dmrt1 and p53 together. Down-regulating Dmrt1 seemed to induce Sox 2 and Oct4 expression, which conferred pluripotency to the cell.31 It is important to know the exact mechanism of such conversion between uni-potent SSCs and the pluripotent ES-state, in that this would allow us to manipulate these important cells in a reliable manner.

IN VITRO SPERMATOGENESIS WITH AN ORGAN CULTURE METHOD

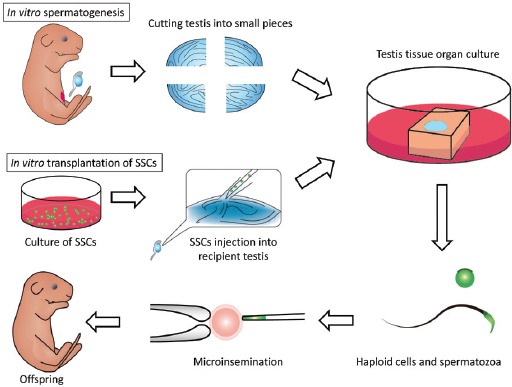

Studies on in vitro spermatogenesis date back to organ culture experiments about a century ago.32 In 1937, it was reported that spermatogenesis proceeded up to the pachytene stage of meiosis in testis tissues of a newborn mouse placed on a blood clot.33 In the 1960s, organ culture methods advanced and various conditions were extensively examined. However, it was not possible to promote spermatogenesis beyond the pachytene stage.34,35 Thereafter, cell culture methods, instead of organ culture, were used with new concepts and devices, including immortalized germ cell lines,36 the production of Sertoli cell lines for use as feeder cells,37 and bicameral chamber methods.38,39,40 Despite such endeavors, progress has been limited and it had been impossible to produce fertility-competent haploid cells from SSCs in vitro.39,40,41 After achieving the successful cultivation of SSCs and GS cells, we and others tried to promote their differentiation to sperm in vitro. However, we did not observe meiotic progression of the cells, let alone production of haploid cells. We then decided to re-evaluate organ culture methods based on the idea that the histological architecture of the testis, seminiferous tubules in particular, is necessary for the progression of spermatogenesis. We adopted the classical air-liquid interphase method that Takeshi Miura et al. and Emil and Anna Steinberger used for the testes of eels and rats, respectively.34,35,42 Using mice, we successfully replicated the results reported by the Steinbergers but were not able to make spermatogenesis progress beyond the pachytene stage of meiosis. When we used KnockOut™ Serum Replacement (KSR) instead of FBS, however, the efficiency of spermatogenesis improved markedly and it culminated in sperm production. The method faithfully produced haploid cells, up to sperm in some cases, which were functional and give rise to offspring by micro-insemination43 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic view of organ culture and in vitro transplantation of SSCs for in vitro spermatogenesis.

Then a question arose: does the spermatogenesis taking place in the cultured tissue really originate from SSCs? In other words, does it really encompass the whole process of spermatogenesis, from SSCs to sperm? We addressed this issue by devising a new experimental technique: the combination of the organ culture method and transplantation of GS cells into seminiferous tubules of the host testis. With this technique, named in vitro transplantation, we found that GS cells initially floating in the seminiferous tubule migrated toward the basement membrane to colonize it. They proliferated and formed colonies of spermatogenesis and differentiated into sperm in the cultured tissues44 (Figure 3). This was the first experiment to produce functional sperm from authentic SSCs totally in vitro.

We also tried to reconstruct the testicular histological architecture from cells singly dissociated enzymatically. We succeeded in inducing such a reconstruction using the subcutaneous space of nude mice as an incubator.45 In that experiment, testes of neonatal mice were digested with enzymes to produce a cell suspension, which was injected under the back subcutis of nude mice. The injected suspensions formed a quasi-testis structure which received its vascular supply from the host mouse. When we mixed GS cells in the dissociated testis cell suspension, some GS cells were incorporated into the newly formed seminiferous tubule and underwent spermatogenesis up to round spermatid formation, and viable offspring were produced with these round spermatids by micro-insemination.45 Thus, we wondered whether the same reconstruction would be possible under culture conditions, although a vascular supply could not be available. In the initial step, the enzymatically dissociated cells of the neonate mouse testis were cultured under suspension conditions to induce aggregation. Formed cell-aggregates were then transferred to the top of agarose gel and they were cultured according to our organ culture method. In 2 weeks, tubular structures emerged. The tubules that were formed contained Sertoli cells which expressed Sox9. Leydig cells, which expressed β-HSD, were observed between the tubules. There were also some germ cells in the reconstructed tubules and they differentiated up to meiotic cells.46 This means that it is possible to build the testicular architecture de novo from singly dissociated immature testicular cells and expect spermatogenesis to proceed up to, at least, the meiotic phase under culture conditions. This will certainly be a useful method for the study of testicular organogenesis and spermatogenesis. The combination of cells from different sources, not only germ cells but also different kinds of somatic cell, will be possible for testis reconstruction. When those cells become available from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or other accessible cell sources,47,48 testicular tissue fragments could be rebuilt in vitro from those cells without depending on the testis of individuals as a cell source in the future, which will make this method more useful and even practical for application to the study of human spermatogenesis.

INDUCTION OF SSCS FROM ESCS/IPSCS

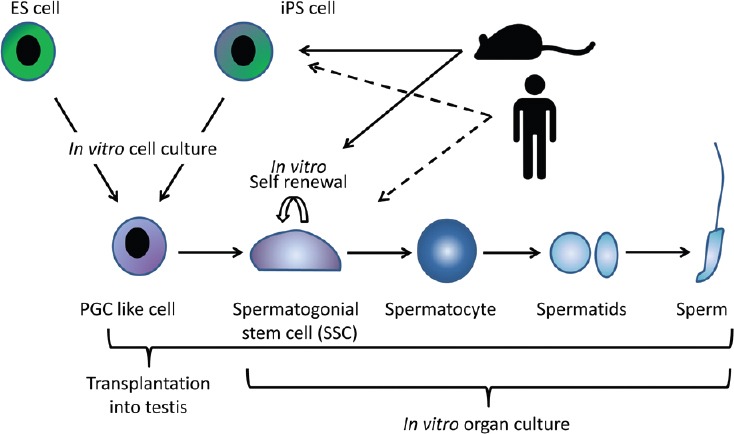

The origin of SSCs traces back to primordial germ cells (PGCs) in the embryonic stage, while PGCs originate from a small population of cells in the epiblast, which comes from the inner cell mass (ICM) of the blastocyst. Thus, it should be possible to induce PGCs or SSCs from ES cells (ESCs), which are derived from ICM and can be introduced back into ICM to take part in the subsequent embryogenesis, if we can exactly replicate the embryonic developmental process under culture conditions. Based on such an idea, Hayashi and Saitou successfully produced PGCs, although they cautiously call them “PGC-like cells (PGCLCs),” from ESCs in vitro.49 They meticulously mimicked the developmental process; thus, ES cells were induced first to “epiblast-like cells (EpiLCs)” before becoming PGCLCs. The PGCLCs differentiated into sperm when transplanted into the seminiferous tubules of a recipient mouse. The sperm were functional and produced offspring by micro-insemination. The same germ cell induction was also achieved from not only ESCs but also from iPSCs. This means that somatic cells were artificially converted through iPS cells to germ cells. The same research team also succeeded in producing oocytes from iPS cells.50 In addition, this conversion from ES/iPS cells to PGCs became highly efficient with a direct reprogramming method, the introduction of a set of transcription factors.51 These recent research developments are encouraging to elucidate the mechanisms of germ cell development and gametogenesis in the near future. At the same time, conversion from somatic to germ cells would arouse ethical concerns anticipating future clinical applications.

CONCLUSION

The study of SSCs has markedly advanced over the last two decades, especially in the last decade. Their identity in the testis along with their proliferation/differentiation control mechanism became clearer. They can be maintained in vitro and induced to differentiate up to sperm with an organ culture method. In addition, ES/iPS cells were induced to become PCGs in vitro (Figure 4). Conversion of somatic cells up to sperm totally in vitro would be possible in the near future. However, these results were mostly obtained using the mouse as a model animal. Future studies may be focused on species other than mice, including humans. Studies on human SSCs and human spermatogenesis are now needed to reinforce our knowledge of male reproductive physiology and pathology. Based on such new information, we will be able to establish a sophisticated management method for male fertility control and treatments for male infertility patients.

Figure 4.

Schematic view of recent progress in the study of in vitro spermatogenesis. In mice, PGC-like cells can be induced from ES and iPS cells under in vitro condition. Transplantation of PGC-like cells into the recipient mouse testis induces their differentiation up to sperm. On the other hand, SSCs can be induced to differentiate into sperm by organ culture in vitro (solid arrows). In future, a therapeutic strategy for infertile patients could be possible through same strategies, especially with in vitro culture method.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Yoshida for his critical and constructive comments on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagano MC. Homing efficiency and proliferation kinetics of male germ line stem cells following transplantation in mice. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:701–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meistrich ML, van Beek ME. Spermatogonial stem cells. In: Desjardins C, Ewing LL, editors. Cell and Molecular Biology of the Testis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 266–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oakberg EF. Spermatogonial stem-cell renewal in the mouse. Anat Rec. 1971;169:515–31. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091690305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huckins C. The spermatogonial stem cell population in adult rats. I. Their morphology, proliferation and maturation. Anat Rec. 1971;169:533–57. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091690306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie T, Spradling AC. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science. 2000;290:328–30. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran J, Brenner TJ, DiNardo S. Somatic control over the germline stem cell lineage during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Nature. 2000;407:754–7. doi: 10.1038/35037613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–4. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagawa T, Nabeshima Y, Yoshida S. Functional identification of the actual and potential stem cell compartments in mouse spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2007;12:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hara K, Nakagawa T, Enomoto H, Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, et al. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:658–72. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11298–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrinski I, Ogawa T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Computer assisted image analysis to assess colonization of recipient seminiferous tubules by spermatogonial stem cells from transgenic donor mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;53:142–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199906)53:2<142::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. β1- and α6-integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5504–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinohara T, Orwig KE, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cell enrichment by multiparameter selection of mouse testis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8346–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cells share some, but not all, phenotypic and functional characteristics with other stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6487–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631767100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. CD9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:70–5. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clouthier DE, Avarbock MR, Maika SD, Hammer RE, Brinster RL. Rat spermatogenesis in mouse testis. Nature. 1996;381:418–21. doi: 10.1038/381418a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Transplantation of germ cells from rabbits and dogs into mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1331–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvönen ME, Parvinen M, de Rooij DG, et al. Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science. 2000;287:1489–93. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, et al. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:612–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Growth factors essential for self-renewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuda M, Sasaoka Y, Kiso M, Abe K, Haraguchi S, et al. Conserved role of nanos proteins in germ cell development. Science. 2003;301:1239–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1085222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti G, Manova K, et al. Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:653–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oatley MJ, Kaucher AV, Racicot KE, Oatley JM. Inhibitor of DNA binding 4 is expressed selectively by single spermatogonia in the male germline and regulates the self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:347–56. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.091330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aloisio GM, Nakada Y, Saatcioglu HD, Peña CG, Baker MD, et al. PAX7 expression defines germline stem cells in the adult testis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3929–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI75943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu BY, Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Conservation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal signaling between mouse and rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14302–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamra FK, Chapman KM, Nguyen DM, Williams-Stephens AA, Hammer RE, et al. Self renewal, expansion, and transfection of rat spermatogonial stem cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17430–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508780102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota H, Wu X, Goodyear SM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and endothelial cells promote self-renewal of rabbit germ cells with spermatogonial stem cell properties. FASEB J. 2011;25:2604–14. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Muneto T, Lee J, Takenaka M, Chuma S, et al. Long-term culture of male germline stem cells from hamster testes. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:611–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishii K, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. FGF2 mediates mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal via upregulation of Etv5 and Bcl6b through MAP2K1 activation. Development. 2012;139:1734–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.076539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takashima S, Hirose M, Ogonuki N, Ebisuya M, Inoue K, et al. Regulation of pluripotency in male germline stem cells by Dmrt1. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1949–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.220194.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champy C. Quelques resultats de la měthode de culture des tissues. Arch Zool Exp Gen. 1920;60:461–500 [in French]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinovitch PN. Development in vitro of the mammalian gonad. Nature. 1937;139:413. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberger A, Steinberger E, Perloff WH. Mammalian testes in organ culture. Exp Cell Res. 1964;36:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(64)90156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinberger A, Steinberger E. Factors affecting spermatogenesis in organ cultures of mammalian testes. J Reprod Fertil. 1967;2(Suppl):117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng LX, Chen Y, Dettin L, Pera RA, Herr JC, et al. Generation and in vitro differentiation of a spermatogonial cell line. Science. 2002;297:392–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1073162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rassoulzadegan M, Paquis-Flucklinger V, Bertino B, Sage J, Jasin M, et al. Transmeiotic differentiation of male germ cells in culture. Cell. 1993;75:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90543-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staub C, Hue D, Nicolle JC, Perrard-Sapori MH, Segretain D, et al. The whole meiotic process can occur in vitro in untransformed rat spermatogenic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;260:85–95. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staub C. A century of research on mammalian male germ cell meiotic differentiation in vitro. J Androl. 2001;22:911–26. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2001.tb03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parks JE, Lee DR, Huang S, Kaproth MT. Prospects for spermatogenesis in vitro. Theriogenology. 2003;59:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(02)01275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La Salle S, Sun F, Handel MA. Isolation and short-term culture of mouse spermatocytes for analysis of meiosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;558:279–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-103-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miura T, Yamauchi K, Takahashi H, Nagahama Y. Hormonal induction of all stages of spermatogenesis in vitro in the male Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5774–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato T, Katagiri K, Gohbara A, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, et al. In vitro production of functional sperm in cultured neonatal mouse testes. Nature. 2011;471:504–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato T, Katagiri K, Yokonishi T, Kubota Y, Inoue K, et al. In vitro production of fertile sperm from murine spermatogonial stem cell lines. Nat Commun. 2011;2:472. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kita K, Watanabe T, Ohsaka K, Hayashi H, Kubota Y, et al. Production of functional spermatids from mouse germline stem cells in ectopically reconstituted seminiferous tubules. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:211–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokonishi T, Sato T, Katagiri K, Komeya M, Kubota Y, et al. In vitro reconstruction of mouse seminiferous tubules supporting germ cell differentiation. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:1–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.108613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bucay N, Yebra M, Cirulli V, Afrikanova I, Kaido T, et al. A novel approach for the derivation of putative primordial germ cells and sertoli cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:68–77. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buganim Y, Itskovich E, Hu YC, Cheng AW, Ganz K, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into embryonic Sertoli-like cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:373–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kurimoto K, Aramaki S, Saitou M. Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2011;146:519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayashi K, Ogushi S, Kurimoto K, Shimamoto S, Ohta H, et al. Offspring from oocytes derived from in vitro primordial germ cell-like cells in mice. Science. 2012;338:971–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1226889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakaki F, Hayashi K, Ohta H, Kurimoto K, Yabuta Y, et al. Induction of mouse germ-cell fate by transcription factors in vitro. Nature. 2013;501:222–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]