Abstract

Zn2+ plays essential and diverse roles in numerous cellular processes. To get a better understanding of intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis and the putative signaling role of Zn2+, various fluorescent sensors have been developed that allow monitoring of Zn2+ concentrations in single living cells in real time. Thus far, two families of genetically encoded FRET-based Zn2+ sensors have been most widely applied, the eCALWY sensors developed by our group and the ZapCY sensors developed by Palmer and co-workers. Both have been successfully used to measure cytosolic free Zn2+, but distinctly different concentrations have been reported when using these sensors to measure Zn2+ concentrations in the ER and mitochondria. Here, we report the development of a versatile alternative FRET sensor containing a de novo Cys2His2 binding pocket that was created on the surface of the donor and acceptor fluorescent domains. This eZinCh-2 sensor binds Zn2+ with a high affinity that is similar to that of eCALWY-4 (Kd = 1 nM at pH 7.1), while displaying a substantially larger change in emission ratio. eZinCh-2 not only provides an attractive alternative for measuring Zn2+ in the cytosol but was also successfully used for measuring Zn2+ in the ER, mitochondria, and secretory vesicles. Moreover, organelle-targeted eZinCh-2 can also be used in combination with the previously reported redCALWY sensors to allow multicolor imaging of intracellular Zn2+ simultaneously in the cytosol and the ER or mitochondria.

Although zinc is sometimes still referred to as a “trace metal ion”, zinc ions play a range of essential roles in numerous cellular processes. In addition to serving as a cofactor in enzyme catalysis and protein stabilization,1,2 Zn2+ ions have been postulated to be involved in a variety of signaling processes, ranging from a relatively well-established role in neuromodulation,3 insulin secretion,4,5 and fertilization6,7 to its proposed role as a secondary messenger in intracellular signaling.8,9 The high intrinsic affinity of Zn2+ for the amino acid side chains of cysteines, histidines, as well as carboxylic acids makes the free Zn2+ ion a potent inhibitor of enzymes and a potential modulator of protein–protein interactions.10−12 The level of free Zn2+ in the cytosol is therefore believed to be tightly controlled between 100 pM and 1 nM,13−15 which is sufficient for Zn2+ to bind to native Zn-binding proteins but low enough not to interfere with normal metabolic and signaling processes.16 The concentration of free Zn2+ can be very different in other parts of the cell, however, as millimolar concentrations of total Zn2+ have been reported for secretory vesicles in pancreatic β cells,17 oocytes,7 neuronal cells,18 and mast cells.19 Triggered release of Zn2+ from organelles has been implicated in transient increases in cytosolic free Zn2+, potentially regulating the activity of regulatory enzymes such as protein phosphatases and caspases.8,9

To get a better understanding of intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis and the putative signaling role of Zn2+, a variety of fluorescent sensors have been developed that allow monitoring of Zn2+ concentrations in single living cells in real time. Although small molecule sensors are still the most commonly used imaging probes,20,21 it has proven challenging to control their subcellular localization and concentration. In contrast, genetically encoded, protein-based sensors can be conveniently targeted to specific subcellular locations and, at least in the cytosol, were found to not perturb intracellular free Zn2+ levels.13,22,23 Thus far, two families of genetically encoded FRET-based Zn2+ sensors have been most widely applied: the eCALWY13 sensors developed by our group and the ZapCY sensors developed by Palmer and co-workers.14 These FRET-based sensors are ratiometric and display at least a 2-fold change in emission ratio upon binding Zn2+ at physiological pH. Their affinities have been tuned within the picomolar to nanomolar range, and for both families red-shifted variants have been developed to allow multiparameter imaging.24,25 The eCALWY sensors consist of two small, CXXC-motif-containing metal binding domains (ATOX1 and WD4), connected by a long and flexible peptide linker, which in turn are linked to self-associating variants of cerulean and citrine. Formation of a tetrahedral Zn2+ complex between the metal binding domains disrupts the interaction between the fluorescent domains, resulting in a decrease in citrine/cerulean emission ratio. Substitution of one of the cysteines by a serine in the WD4 domain decreased the Zn2+ affinity from 2 pM in eCALWY-1 to 630 pM in eCALWY-4, whereas shortening of the linker between the metal binding domains allowed more subtle attenuation of the Zn2+ affinity. Application of these eCALWY sensors for measuring concentrations of cytosolic Zn2+ in various cell types and organisms has shown that cytosolic Zn2+ concentrations are typically between 100 pM and 1 nM, rendering the eCALWY-4 variant the sensor of choice for cytosolic Zn2+ imaging. The ZapCY family of sensors contains the first two zinc finger domains from the Zn2+-responsive transcriptional regulator Zap1. ZapCY1, the sensor containing the wild-type zinc finger domains, displayed an increase in FRET following Zn2+-induced folding of the zinc finger domains with a Kd of 2.5 pM.14 Consistent with the results obtained with the eCALWY sensors, this sensor was found to be fully saturated with Zn2+ when expressed in the cytosol of HeLa cells. Therefore, a lower affinity variant has been constructed by replacing two of the Zn2+ coordinating residues by histidines, yielding a sensor with a Kd of 811 pM.14

Both the eCALWY and ZapCY sensors have been successfully applied to measure cytosolic free Zn2+ in a number of different cell types (primary cells, cell lines) originating from various organisms (bacterial, yeast, mammalian, and plant cells).15,22,26−28 However, while both sensors report similar values for free Zn2+ when expressed in the cytosol, they respond differently when targeted to other organelles such as the ER and the mitochondria.15,28,29 ZapCY1 targeted to the ER and mitochondria was found to be mostly Zn2+-free, which, because of the high affinity ZapCY1, would be consistent with very low concentrations of free Zn2+ of 0.9 pM and 0.22 pM in the ER and mitochondria, respectively. More recent studies using the eCALWY sensors reported free Zn2+ concentrations in the ER and mitochondria that are 2–3 orders of magnitude higher, however.15 The reason for this strikingly different behavior is unclear, but one way to resolve this discrepancy is to develop alternative FRET sensors based on a different binding mechanism. Another incentive for the development of alternative FRET sensors is a need for probes with affinities that are tuned to specific applications, such as measuring the relatively high free Zn2+ concentrations under the acidic conditions present in secretory vesicles.

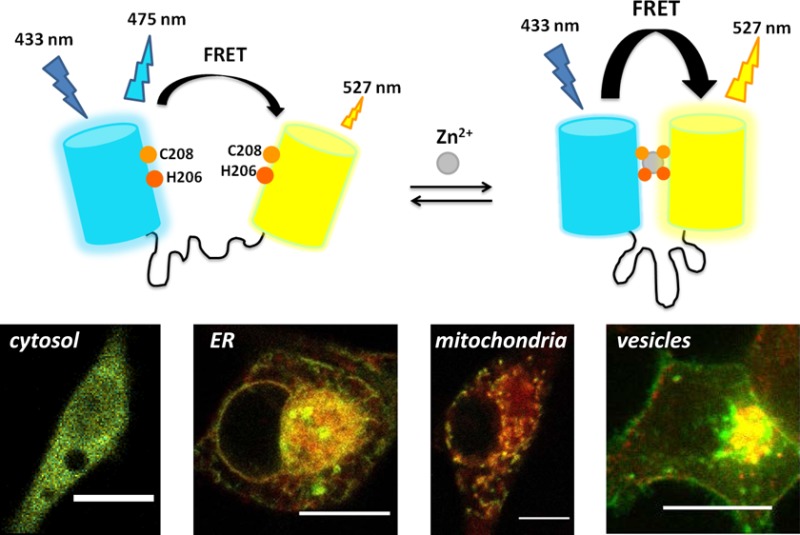

We previously reported the construction of an alternative FRET sensor that lacked separate metal binding domains, but in which Zn2+-coordinating amino acids were introduced directly at the so-called dimerization interface of two fluorescent domains.30 The first generation of these ZinCh sensors showed a large ratiometric change upon Zn2+ binding, but the Zn2+ affinity was relatively low (Kd = 8.2 μM at pH 7.1).13 Here, we show that combining histidine and cysteine coordination to create a Cys2His2 binding pocket on the dimerization interface can increase the affinity for Zn2+ over 1000-fold. This new sensor variant, eZinCh-2, has an affinity that is similar to that of eCALWY-4 (Kd = 1 nM at pH 7.1),13 but a substantially larger change in emission ratio. eZinCh-2 not only provides an attractive alternative for measuring Zn2+ in the cytosol but was also successfully used for measuring Zn2+ in the ER, mitochondria, and even dense core secretory vesicles, providing an independent system for assessing the free Zn2+ concentrations in these organelles. Moreover, organelle-targeted eZinCh-2 provides an attractive sensor to be used in combination with our previously reported red eCALWY variants to allow multicolor imaging of intracellular Zn2+ simultaneously in the cytosol and the ER or mitochondria.

Results and Discussion

Development and in Vitro Characterization of eZinCh-2

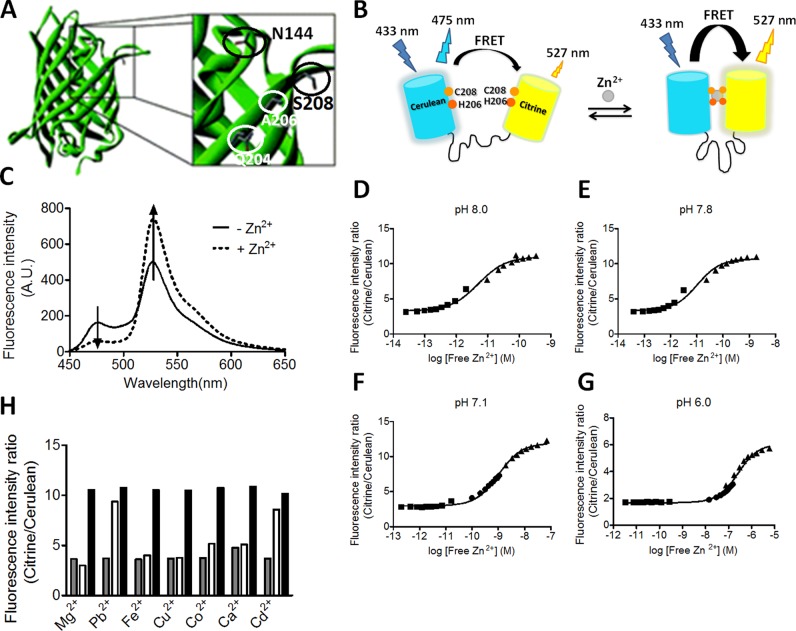

In an effort to create high affinity Zn2+ binding sites at the dimerization interface of the eZinCh FRET sensor, we previously created several variants with two cysteines on each of the two fluorescent domains (C144/C206, C206/C208, and C206/C204; Figure 1A).31 None of these variants showed enhanced affinity for Zn2+ compared to the parent sensor eZinCh-1, which contained a single Cys at position 208. Increased affinity was observed for Cd2+, a metal ion with similar coordination properties as Zn2+, but a larger ionic radius.31 Modeling showed that the Cys4 binding pocket created by displaying cysteines on a β-barrel scaffold in these variants was too large to allow simultaneous coordination of Zn2+ by all four cysteines and suggested that a binding site consisting of a combination of cysteines and histidines might provide a better Zn2+ binding site.32 We therefore screened a small collection of sensor variants in which one or two of the cysteines were mutated to histidines for increased Zn2+ affinity at pH 7.1. Three variants were found with a Zn2+ affinity in the low nanomolar range at pH 7.1 (Supporting Table 1; Supporting Figure 1), which is 3 orders of magnitude higher compared to the original eZinCh sensors. Only one sensor displayed a large, 4-fold change in emission ratio, whereas the other two showed ∼10% changes in emission ratio. This sensor variant, which contains a cysteine at position 208 and a histidine at position 206 on both domains, was further characterized in vitro and will be referred to as eZinCh-2 (Figure 1). The small change in emission ratio observed for the other two variants could be due to an unfavorable orientation of the two fluorescent domains in the Zn2+-bound state, resulting in a low value for the orientation factor κ and relative inefficient energy transfer.

Figure 1.

Design and Zn2+ binding properties of eZinCh-2. (A) Crystal structure of green fluorescent protein (PDB code: 1GFL)33 showing the positions that were used to introduce cysteine or histidine residues. (B) eZinCh-2 sensor design containing a Cys2His2 binding pocket on the dimerization interface of both fluorescent proteins. (C) Emission spectra of eZinCh-2 before (empty) and after (Zn2+ saturated) addtion of Zn2+. (D–G) Zn2+ titrations of eZinCh-2 at different pH’s, showing the emission ratio of citrine over cerulean as a function of Zn2+ concentration. To obtain picomolar to micromolar free Zn2+ concentrations, HEDTA (squares) and different amounts of EGTA (5 mM and 1 mM, circles and triangles, respectively) were used as buffering systems (Tables S2–S5). Solid lines represent a fit assuming a 1:1 binding event, yielding Kd’s of 256 nM (pH 6.0), 1.03 nM (pH 7.1), 10 pM (pH 7.8), and 5 pM (pH 8.0). Measurements were performed in 150 mM MES (pH 6.0), 150 mM HEPES (pH 7.1), or 50 mM Tris (pH 7.8 and 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01% Tween and 1 mM DTT at 20 °C. (H) Emission ratio of eZinCh-2 before (gray bars) and after (white bars) the addition of Pb2+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Co2+, or Cd2+ (all 20 μM) or Mg2+ or Ca2+ (both 0.5 mM) in the presence of 10 μM TPEN. The black bars show the emission ratio upon subsequent addition of 20 μM Zn2+.

Zn2+ titration experiments were done to determine the Zn2+ affinity of eZinch-2 at different, physiologically relevant pH’s. At pH 7.1, which is the pH of the cytosol and the ER lumen, eZinCh-2 binds Zn2+ with a Kd of 1.0 ± 0.1 nM. This affinity is similar to that of eCALWY-4 at this pH, whereas the change in emission ratio for eZinCh-2 is 2-fold higher (400% vs 200%). Titrations done at pH 6, the pH representative of vesicular conditions, yielded a Kd of 256 ± 22 nM. This affinity is still 3 orders of magnitude higher than that of its predecessor eZinCh-1, while retaining a large, 300% change in emission ratio. As expected, increasing the pH results in stronger Zn2+ binding, yielding Kd values of 5 and 10 pM at pH 8 and 7.8, respectively. The affinity of eZinCh-2 at pH 7.8, which is representative of the pH in the mitochondrial matrix, is 6-fold stronger than that of eCALWY-4. Based on these Zn2+ affinities, the eZinCh-2 sensor may represent a versatile sensor to measure Zn2+ not only in the cytosol but also in the ER, mitochondrial matrix, and secretory vesicles. However, since the Cys2His2 site at the dimerization interface in eZinCh-2 was created de novo, it was important to first assess its metal specificity. The emission ratio of eZinCh-2 was therefore measured in the presence of a wide variety of metal ions (20 μM or 5 mM) and 10 μM of the zinc chelator TPEN (Figure 1G). An increase in emission ratio was observed for Cd2+ and Pb2+, which was not unexpected as these metal ions have similar coordination properties to Zn2+. However, no significant changes were observed for physiological relevant metal ions such as Fe2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, or Ca2+. To test whether these metal ions might still compete with Zn2+ binding and in this way interfere with Zn2+ sensing, the emission ratio was also determined upon subsequent addition of 20 μM Zn2+. None of the metals had any effect on the Zn2+ binding response, however.

Using eZinCh-2 to Monitor Intracellular Free Zn2+ Concentrations in the Cytosol

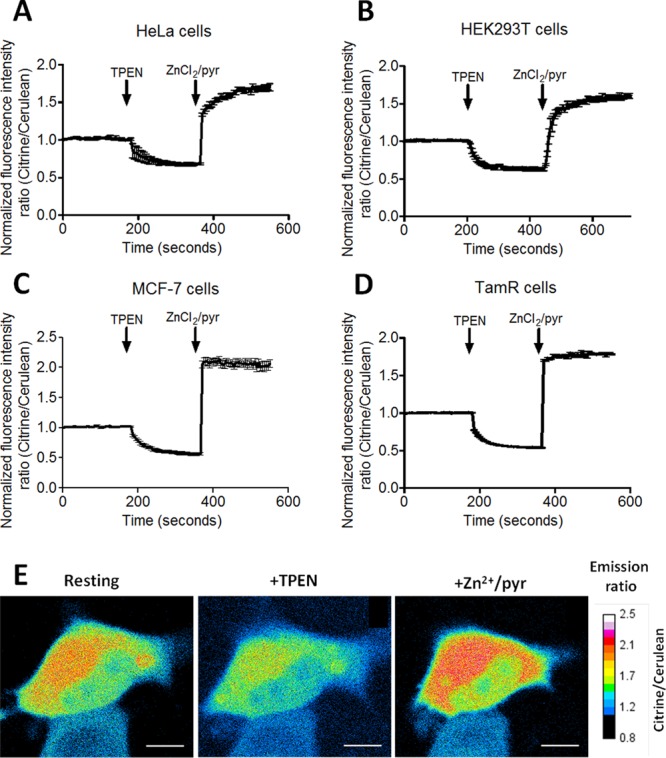

Its Zn2+ affinity of 1 nM at pH 7.1, together with its 4-fold change in emission ratio, makes eZinCh-2 an attractive alternative to eCALWY-4 and ZapCY2 for measuring cytosolic free Zn2+ levels. The eZinCh-2 construct was cloned into a plasmid containing a CMV promoter for transient expression, and the performance of eZinCh-2 was tested in four different mammalian cell lines. HeLa and HEK293T cells were chosen because these cells were previously used for the in situ characterization of the eCALWY and ZapCY sensors.13,28 In addition, we also used eZinCh-2 to determine the cytosolic free Zn2+ concentration in wild-type (MCF-7) and tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 (TamR) breast cancer cell lines. These breast cancer cell lines were chosen because previous work using small molecule fluorescent sensors reported increased levels of intracellular Zn2+ in TamR cells compared to wild-type MCF-7 cells.34,35 The performance of eZinCh-2 was assessed by monitoring the response of the eZinCh-2 sensor in single living cells to the subsequent addition of the strong membrane-permeable Zn2+ chelator TPEN, followed by the addition of excess Zn2+ together with the Zn2+ specific ionophore pyrithione (Figure 2). In all cell lines tested, a robust, 3-fold change in citrine over cerulean emission ratio was observed between the Zn2+-depleted and Zn2+-saturated states of the sensor. eZinCh-2 also showed relatively fast in situ association and dissociation kinetics, and low variability between individual cells. The determination of Rmin and Rmax allowed calculation of the sensor occupancy at the start of the experiment, which could be translated into a free Zn2+ concentration using the Kd of 1 nM that was measured in vitro. Very similar free Zn2+ concentrations of 0.87 ± 0.10 nM and 0.83 ± 0.10 nM were determined for HeLa and HEK293 cells, respectively. These numbers agree reasonably well with values determined previously using the eCALWY and ZapCY sensors in the same cell types. Slightly lower concentrations of free Zn2+ were measured in wild type MCF-7 cells (0.44 ± 0.06 nM) and TamR cells (0.65 ± 0.06 nM). These results show that cytosolic Zn2+ concentrations are well-buffered and relatively constant among different mammalian cell types, in particular when one considers that cell lines were grown under slightly different conditions, each optimal for that specific cell type. In addition, the increased levels of intracellular Zn2+ that were previously reported for TamR cells, apparently do not translate into a large increase in the concentration of free Zn2+ in the cytosol of these cells.

Figure 2.

Determination of the free cytosolic Zn2+ concentration in different cell types using eZinCh-2. (A–D) Responses of HeLa (A), HEK293T (B), MCF-7 (C), and TamR (D) cells expressing eZinCh-2 to the addition of 50 μM TPEN, followed by the addition of 100 μM Zn2+/ 5 μM pyrithione. All traces in A–D represent the average of at least four cells after normalization of the emission ratio at t = 0. Error bars represent SEM. (E) False colored ratiometric images of a HeLa cell expressing eZinCh-2 in a resting state (start), after perfusion with 50 μM TPEN (+TPEN), and 100 μM ZnCl2/5 μM pyrithione (+Zn/pyr).

Targeting of eZinCh-2 to the Endoplasmic Reticulum

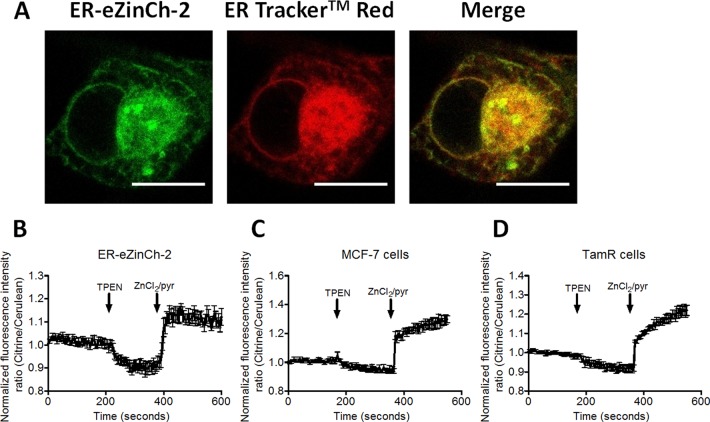

Following the robust performance of eZinCh-2 in imaging cytosolic Zn2+, we next explored its suitability for measuring free Zn2+ in the ER. eZinCh-2 was targeted to the lumen of the ER by introducing a preproinsulin (PPI) signal peptide sequence at the N-terminus and a C-terminal retention sequence KDEL, yielding ER-eZinCh-2. Co-staining with a commercially available ER tracker (ER-tracker Red, Life Technologies) confirmed correct targeting of ER-eZinCh-2 in HeLa cells (Figure 3A). The addition of TPEN to HeLa cells expressing ER-eZinCh-2 showed a decrease in emission ratio that was stable after a few minutes. Subsequent addition of excess Zn2+ in the presence of pyrithione resulted in an immediate increase in emission ratio. Based on these traces, a free Zn2+ concentration of 0.8 ± 0.6 nM was determined for the ER in HeLa cells. The large standard error for the estimated Zn2+ levels reflects relatively high cell-to-cell variability, with some cells showing a concentration of 1.5 nM, while others contain only 0.3 nM. Although these concentrations are slightly lower than estimated using ER-targeted eCALWY-4,15 these values are still at least 100-fold higher than the concentration estimated using ZapCY1 in HeLa cells.28

Figure 3.

Zn2+ imaging using ER-targeted eZinCh-2 in different cells types. (A) Fluorescent confocal images of a HeLa cell expressing ER-eZinCh-2 in the endoplasmic reticulum, costained with ER-tracker red. Pearson’s coefficient, 0.936. Scale bar, 15 μm. (B–D) Responses of HeLa (B), MCF-7 (C), and TamR (D) cells expressing ER-eZinCh-2 to the addition of 50 μM TPEN, followed by the addition of 100 μM Zn2+/5 μM pyrithione. All traces in B–D represent the average of at least four cells after normalization of the emission ratio at t = 0. Error bars represent SEM.

Previous work by Taylor and co-workers showed increased expression of ZIP7 in TamR cells compared to wild type MCF-7 cells. ZIP7 is a Zn2+ transporter protein located almost exclusively on the ER membrane. Phosphorylation of ZIP7 was shown to activate the importer, resulting in release of Zn2+ from the ER into the cytosol.9 To establish whether TamR cells have increased concentrations of free Zn2+ in the ER, ER-ZinCh-2 was expressed in both wild-type MCF-7 and TamR cells (Figure 3C,D). The addition of TPEN and excess Zn2+ showed similar response curves to those found in HeLa cells, yielding free ER Zn2+ concentrations of 0.54 ± 0.27 nM for MCF-7 and 0.75 ± 0.49 nM for TamR cells. Please note that Rmax was determined using the immediate, rapid increase in emission ratio following the addition of excess Zn2+. Control measurements using ER-targeted eCALWY-4 gave similar ER Zn2+ concentrations of 0.39 ± 0.17 nM and 0.21 ± 0.05 nM for MCF-7 and TamR cells, respectively (Supporting Figure 2). Again, the cell-to-cell variation in free Zn2+ concentration was found to be larger in the ER when compared to the cytosol, which may reflect more efficient buffering of the free Zn2+ concentration in the cytosol due to the presence of metallothionein.

Targeting eZinCh-2 to Mitochondria and Insulin-Secreting Vesicles

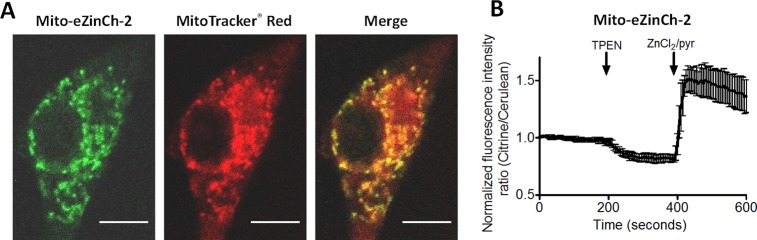

To explore whether eZinCh-2 could also be successfully applied to other organelles, we targeted the sensor to the mitochondrial matrix in HeLa cells and to insulin-secreting vesicles in INS-1 (832/13) cells, a rat pancreatic beta cell line. Targeting to the mitochondrial matrix was achieved by introducing the N-terminal targeting sequence from cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIII (Cox VIII), yielding mito-eZinCh-2. Co-staining HeLa cells expressing mito-eZinCh-2 with MitoTracker Red (Life Technologies) confirmed correct targeting of the genetically encoded Zn2+ probe to this compartment (Figure 4A). A robust response to the addition of TPEN and excess Zn2+ was observed (Figure 4B), showing an average occupancy of the sensor of 23 ± 6% (Figure 4B). Assuming an intramitochondrial pH of 7.8, and thus a Kd of 10 pM for eZinCh-2, this number translates into a mitochondrial matrix Zn2+ concentration of 3.3 ± 1.2 pM. Experiments under identical conditions in the same cells using mito-eCALWY-4 yielded a somewhat higher concentration of about 42 ± 28 pM (Supporting Figure 3; Table S6). These mitochondrial free Zn2+ concentrations are in between those previously reported using eCALWY-4 (∼200 pM) in a number of cell lines and the 0.14 pM determined using the ZapCY-1 sensors.29 A value of 0.2 pM has also been reported by Thompson and co-workers using a carbonic anhydrase based FRET sensor,36 while a concentration of 72 pM has been determined using a small molecule ratiometric fluorescent probe targeted to the mitochondria of NIH3T3 cells.37 Because the Zn2+ affinities of both eZinCh-2 and the other two FRET sensors are strongly pH sensitive, it is important to note that these values will be very dependent on the exact pH of the mitochondrial matrix, however.

Figure 4.

Targeting of eZinCh-2 to the mitochondrial matrix. (A) Fluorescent confocal images of a HeLa cell expressing the mitochondrial targeted mito-eZinCh-2, costained with MitoTracker Red. Pearson’s coefficient, 0.895. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Response of mito-eZinCh-2 expressed in HeLa cells upon the addition of 50 μM TPEN, followed by the addition of excess 100 μM Zn2+/5 μM pyrithione. The trace in B represent the average of four cells after normalization of the emission ratio at t = 0. Error bars represent SEM.

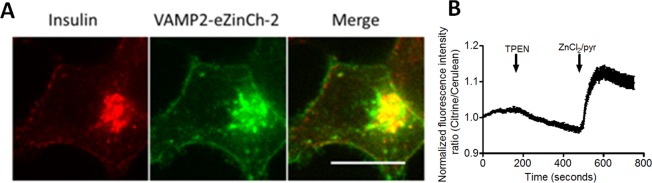

In an effort to determine the free Zn2+ concentrations in secretory vesicles, we previously targeted both the eCALWY sensors and the eZinCh-1 sensor to insulin granules of INS-1 (832/13) cells by fusing them to the vesicle-targeted membrane protein 2 (VAMP2). However, neither of these sensors showed changes in emission ratio upon the addition of TPEN or Zn2+/pyrithione. Vesicular targeting of eZinCh-2 was performed similarly by fusion of VAMP-2 to the N-terminus of eZinCh-2. Co-staining of VAMP2-eZinCh-2 with an insulin-specific antibody revealed significant localization to insulin-containing granules as expected (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Targeting of eZinCh-2 to insulin secreting vesicles. (A) Overlay of the fluorescent confocal images of INS-1 (832/13) cells expressing vesicular targeted VAMP2-eZinCh-2, costained for insulin. Pearson’s coefficient, 0.83. Scale bar, 15 μm. (C) Ratiometric response of INS-1 (832/13) cells expressing VAMP2-eZinCh-2 to perfusion with 50 μM TPEN, or 100 μM Zn2+/5 μM pyrithione. Traces in C represent the average of 10 cells after normalization of the emission ratio at t = 0. Error bars represent SEM.

Interestingly, vesicular-targeted eZinCh-2 was found to be responsive to the addition of TPEN and Zn2+/pyrithione (Figure 5B). A relatively slow decrease in emission ratio was observed upon the addition of TPEN, suggesting that prolonged incubation with TPEN is required to lower the relatively high free Zn2+ concentration in these vesicles. Subsequent addition of Zn2+/pyrithione induced a relatively rapid increase in emission ratio. Although it is more difficult to determine the sensor occupancy very accurately in this case, VAMP2-eZinCh-2 appeared to be ∼30% saturated, which, assuming an intragranular pH of 6,38 corresponds to a free Zn2+ concentration of ∼120 nM. Also in this case, more accurate determination of these values will require independent assessment of the vesicular pH. Nonetheless, as far as we know, these results represent the first successful application of a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for vesicular Zn2+.

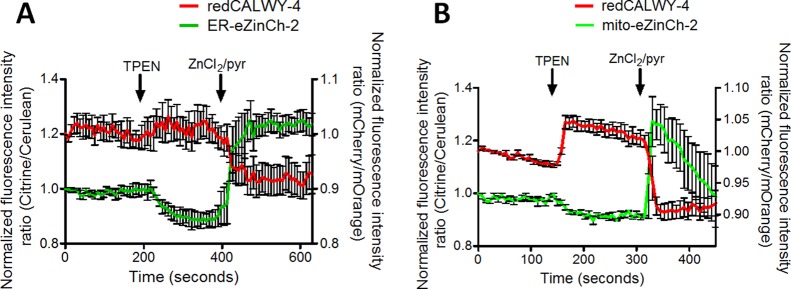

Multicolor Imaging

The results shown above prove that eZinCh-2 is a versatile Zn2+ sensor that can be applied to monitor the free Zn2+ concentrations in a number of different organelles. eZinCh-2 would therefore be an attractive sensor to use in conjunction with one of the recently developed red-shifted cytosolic eCALWY sensors to allow simultaneous monitoring of cytosolic and organelle Zn2+ concentrations in a single cell. To explore the feasibility of using eZinCh-2 for multicolor imaging, we coexpressed the cytosolic redCALWY-4 sensor with either ER-ZinCh-2 or mito-eZinCh-2 in HeLa cells. redCALWY-4 is a red-shifted variant of eCALWY-4 in which the original cerulean and citrine fluorescent domains have been replaced by self-associating variants of the mOrange2 and mCherry, respectively.24Figure 6A shows that coexpression of cytosolic redCALWY-4 together with ER-eZinCh-2 allows simultaneous monitoring of Zn2+ levels in both the ER and the cytosol (Figure 6A). The response of each sensor to the addition of TPEN or excess Zn2+ was similar to what was observed in single sensor measurements. The addition of TPEN resulted in an increase in acceptor/donor emission ratio for redCALWY-4 and a decrease in acceptor/donor emission ratio for ER-eZinCh-2, both consistent with a simultaneous decrease in cytosolic and ER Zn2+ levels. The opposite behavior was observed upon the addition of excess Zn2+/pyrithione. Successful multicolor imaging was also achieved when coexpressing redCAWY-4 with mito-eZinCh-2. Again, multicolor imaging allowed independent monitoring of both cytosolic and mitochondrial free Zn2+ in the same cell, with each sensor behaving as expected based on single sensor experiments. Because of their smaller volume, imaging in organelles is typically more challenging than measuring in the cytosol. In this case, the organelle Zn2+ status was more easily measured than the cytosolic Zn2+ concentration, however. This is partly due to the relatively low expression levels of the redCALWY sensors, but also a testament of the robust nature of the organelle-targeted eZinCh-2 sensors.

Figure 6.

Responses of HeLa cells expressing both redCALWY-4 (red) and either ER-eZinCh-2 (A) or mito-eZinCh-2 (B) (green) to the addition of 50 μM TPEN, followed by the addition of excess 100 μM Zn2+/5 μM pyrithione. Traces in A and B represent the average of at least four cells after normalization of the emission ratio at t = 0. Error bars represent SEM.

Conclusion

A de novo metal binding site with a remarkable high affinity for Zn2+ was created on the dimerization interface of two fluorescent domains by using a combination of cysteine and histidine coordination. The development of the eZinCh-2 sensor did not require extensive evolution or precise tuning of the secondary coordination sphere, suggesting that a similar strategy could be applied to construct FRET sensors based on different fluorescent proteins (e.g., mOrange/mCherry) or introduce Zn2+-dependent control of other protein–protein interactions. Although the high affinity is consistent with the formation of a Cys2His2 complex, definite proof for such coordination should come from X-ray structure determination and/or EXAFS. This could also help to further optimize the Zn2+ affinity. Alternatively, directed evolution could be envisioned to identify variants of eZinCh-2 with even higher affinity or larger change in emission ratio.

eZinCh-2 provides an attractive alternative to the previously developed FRET sensors of the eCALWY and ZapCY series (Table S6). The lack of separate metal binding domains makes the sensor architecture of eZinCh-2 relatively simple, which may explain the robust expression of eZinCh-2 in all the cell lines we tested. The unique binding mechanism not only ensures a large difference in FRET between the on and off state of the sensor but also provides an opportunity to help resolve some of the contradictory results obtained with the eCALWY and ZapCY sensors. Although the free Zn2+ concentration in the ER was found to be more heterogeneous than in the cytosol, the results obtained with ER-targeted eZinCh-2 largely confirmed previous experiments using ER-targeted eCALWY-415 and are inconsistent with the very low, sub-picomolar concentrations of free Zn2+ determined using ZapCY1.28 When targeted to the mitochondrial matrix eZinCh-2 reported Zn2+ concentrations that are between those reported by the eCALWY-4 probe and the ZapCY1 probe. More definite determination of the mitochondrial free Zn2+ concentration should ideally also involve the experimental determination of the mitochondrial pH, as the Zn2+ affinities of these sensors are known to be strongly pH dependent in this regime. The same strategy is also recommended for future applications in which eZinCh-2 is used to measure vesicular Zn2+.

Methods

Cloning Strategies and Protein Expression and Purification

A detailed description of cloning strategies to create several eZinCh mutants and ER and mitochondrial targeted eZinCh-2 probes, as well as protein expression and purification strategies, can be found in the Supporting Information.

Zn2+ Titration Experiments

Zn2+ titrations were carried out with 1 μM of different eZinCh variants in 2 mL of buffer consisting of 150 mM MES (pH 6.0), 150 mM HEPES (pH 7.1) or 50 mM Tris (pH 7.8 and 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01% Tween, and 1 mM DTT at 20 °C.30 Different Zn2+-chelators (HEDTA and EGTA) were used together with increasing Zn2+ concentrations to reach the desired free Zn2+ concentration. These free Zn2+ concentrations were calculated using the MaxChelator program (http://maxchelator.stanford.edu/). To determine the dissociation constants (Kd) for Zn2+ of eZinCh-2 at different pH’s, the emission ratio was fitted as a function of [Zn2+] using eq 1.

| 1 |

In eq 1, R is the ratio of citrine (at 527 nm) to cerulean (at 475 nm) emission, [Zn2+] is the calculated free Zn2+ concentration in M, P1 is defined as the ratiometric change upon Zn2+ binding, P2 is the ratio (Cit/Cer) in the absence of Zn2+, and Kd is the dissociation constant in M.

Mammalian Cell Culture and Imaging

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. MCF-7 and TamR cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute media (RPMI), supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM fungizone, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at the same temperature and CO2 levels; for TamR cells, the media were supplemented with 10–7 M 4-hydroxytamoxifen. For TamR cells, developed as described previously,39 stripped fetal calf serum (SFCS) was used instead of FBS. INS-1 (832/13) cells were cultured at 37 °C/5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium-pyruvate, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Life Technologies). Cells were seeded on glass coverslips (ø 30 mm, VWR) 1 day before transfection. About 200 000 cells were seeded to reach a confluency of ∼80% on the day of transfection. Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) was used to carry out transfections, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were imaged either 1 day (single sensor experiments) or 2 days (two sensor experiments) after transfection in a HEPES buffer (Live Cell Imaging Buffer, Life Technologies) at 37 °C. Imaging on Hek293T, HeLa, MCF-7, and TamR cells was performed with a confocal microscope (Leica, TCS SP5X) equipped with a 63× water immersion objective, acousto-optical beamsplitters (AOBS), a white light laser, and a 405 nm laser. A black box was installed around the stage of the microscope to avoid surrounding light coming in, and the temperature inside this box was controlled at 37 °C using a temperature controller. For all CFP-YFP based constructs, except for the vesicular targeted sensor, cerulean was excited using the 405 nm laser. For the redCALWY-4, the white light laser was set to 550 nm (5% of full power) to excite mOrange2. Emission was monitored using the AOBS and avalanche photo diode/photomultiplier tubes hybrid detectors (HyD, Leica): cerulean (450–500), citrine (515–595 nm), mOrange2 (565–600), and mCherry (600–630). Images were recorded at either 7.5 s intervals (two sensor experiments) or at 5 s intervals (single sensor experiments). Secretory granule free Zn2+ was imaged in INS1(832/13) cells expressing VAMP2-eZinCh-2 using the protocol described in ref (15) using an Olympus IX-70 wide-field microscope with a 40x/1.35NA oil immersion objective and a zyla sCMOS camera (Andor Technology, Belfast, UK) controlled by Micromanager software.40 Excitation was provided at 433 nm using a monochromator (Polychrome IV, Till Photonics, Munich, Germany). Emitted light was split and filtered with a Dual-View beam splitter (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) equipped with a 505dcxn dichroic mirror and two emission filters (Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT, USA - D470/24 for cerulean and D535/30 for citrine). Images were acquired at 3 s intervals

Cells were perfused for a few minutes with HEPES buffer without additives; next the buffer was changed to a HEPES buffer containing 50 μM N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN, Sigma) for a few minutes, followed by perfusion with HEPES buffer containing 100 μM ZnCl2 and 5 μM of the Zn2+-specific ionophore 2-mercaptopyridine N-oxide (pyrithione, Sigma). Imaging experiments on INS1(832/13) cells were performed using KREBS buffer.13 All buffers were kept at 37 °C during imaging using a water bath.

Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software as described before.15,41 The steady-state fluorescence intensity ratio of acceptor over donor was measured, followed by the determination of the minimum and maximum ratios to calculate the free Zn2+ concentration using the following formula:

in which Rmin is the ratio in the Zn2+ depleted state, after the addition of 50 μM TPEN, and Rmax was obtained upon Zn2+ saturation with 100 μM ZnCl2 in the presence of 5 μM pyrithione.

Acknowledgments

The work of A.M.H. and M.M. was supported by an ECHO grant from The Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (700.59.013) and an ERC starting grant (ERC-2011-StG 280255). This work was supported by an STSM Grant from COST Action TD1304 (ZincNet). G.A.R. was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (WT098424AIA) and a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award. K.M.T. acknowledges the support of a Wellcome Trust University award (091991/Z/10/Z), and we thank Julia Gee for the use of the TAMR cells.

Supporting Information Available

Molecular cloning methods, protein purification methods, primer sequences. Additional titration data, ER-eZinCh-2 MCF-7 and TamR cell measurements, Mito-eZinCh-2 HeLa cell measurements, and nucleotide sequences for expression constructs. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00211.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vallee B. L.; Falchuk K. H. (1993) The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiol. Rev. 73, 79–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. (2009) Molecular aspects of human cellular zinc homeostasis: redox control of zinc potentials and zinc signals. BioMetals 22, 149–157 10.1007/s10534-008-9186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson C. J.; Koh J. Y.; Bush A. I. (2005) The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 449–462 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Chen S.; Bellomo E. A.; Tarasov A. I.; Kaut C.; Rutter G. A.; Li W. H. (2011) Imaging dynamic insulin release using a fluorescent zinc indicator for monitoring induced exocytotic release (ZIMIR). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 21063–21068 10.1073/pnas.1109773109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Liu L.; Li W. H. (2015) Genetic targeting of a small fluorescent zinc indicator to cell surface for monitoring zinc secretion. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 1054–1063 10.1021/cb5007536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A. M.; Bernhardt M. L.; Kong B. Y.; Ahn R. W.; Vogt S.; Woodruff T. K.; O’Halloran T. V. (2011) Zinc sparks are triggered by fertilization and facilitate cell cycle resumption in mammalian eggs. ACS Chem. Biol. 6, 716–723 10.1021/cb200084y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que E. L.; Bleher R.; Duncan F. E.; Kong B. Y.; Gleber S. C.; Vogt S.; Chen S.; Garwin S. A.; Bayer A. R.; Dravid V. P.; Woodruff T. K.; O’Halloran T. V. (2015) Quantitative mapping of zinc fluxes in the mammalian egg reveals the origin of fertilization-induced zinc sparks. Nat. Chem. 7, 130–139 10.1038/nchem.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S.; Sakata-Sogawa K.; Hasegawa A.; Suzuki T.; Kabu K.; Sato E.; Kurosaki T.; Yamashita S.; Tokunaga M.; Nishida K.; Hirano T. (2007) Zinc is a novel intracellular second messenger. J. Cell Biol. 177, 637–645 10.1083/jcb.200702081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. M.; Hiscox S.; Nicholson R. I.; Hogstrand C.; Kille P. (2012) Protein kinase CK2 triggers cytosolic zinc signaling pathways by phosphorylation of zinc channel ZIP7. Sci. Signaling 5, ra11. 10.1126/scisignal.2002585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W.; Jacob C.; Vallee B. L.; Fischer E. H. (1999) Inhibitory sites in enzymes: zinc removal and reactivation by thionein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 1936–1940 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A.; Maret W. (2008) Thionein/metallothionein control Zn(II) availability and the activity of enzymes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 13, 401–409 10.1007/s00775-007-0330-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A.; Maret W. (2007) Dual nanomolar and picomolar Zn(II) binding properties of metallothionein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10911–10921 10.1021/ja071979s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkenborg J. L.; Nicolson T. J.; Bellomo E. A.; Koay M. S.; Rutter G. A.; Merkx M. (2009) Genetically encoded FRET sensors to monitor intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Nat. Methods 6, 737–740 10.1038/nmeth.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y.; Dittmer P. J.; Park J. G.; Jansen K. B.; Palmer A. E. (2011) Measuring steady-state and dynamic endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi Zn2+ with genetically encoded sensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 7351–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabosseau P.; Tuncay E.; Meur G.; Bellomo E. A.; Hessels A.; Hughes S.; Johnson P. R.; Bugliani M.; Marchetti P.; Turan B.; Lyon A. R.; Merkx M.; Rutter G. A. (2014) Mitochondrial and ER-targeted eCALWY probes reveal high levels of free Zn2+. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 2111–2120 10.1021/cb5004064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. (2013) Zinc biochemistry: from a single zinc enzyme to a key element of life. Adv. Nutr. 4, 82–91 10.3945/an.112.003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton J. C.; Penn E. J.; Peshavaria M. (1983) Low-molecular-weight constituents of isolated insulin-secretory granules. Bivalent cations, adenine nucleotides and inorganic phosphate. Biochem. J. 210, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkous D. H.; Flinn J. M.; Koh J. Y.; Lanzirotti A.; Bertsch P. M.; Jones B. F.; Giblin L. J.; Frederickson C. J. (2008) Evidence that the ZNT3 protein controls the total amount of elemental zinc in synaptic vesicles. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 56, 3–6 10.1369/jhc.6A7035.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L. H.; Ruffin R. E.; Murgia C.; Li L.; Krilis S. A.; Zalewski P. D. (2004) Labile zinc and zinc transporter ZnT4 in mast cell granules: role in regulation of caspase activation and NF-kappaB translocation. J. Immunol. 172, 7750–7760 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domaille D. W.; Que E. L.; Chang C. J. (2008) Synthetic fluorescent sensors for studying the cell biology of metals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 168–175 10.1038/nchembio.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan E. M.; Lippard S. J. (2009) Small-molecule fluorescent sensors for investigating zinc metalloneurochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 193–203 10.1021/ar8001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y.; Miranda J. G.; Stoddard C. I.; Dean K. M.; Galati D. F.; Palmer A. E. (2013) Direct comparison of a genetically encoded sensor and small molecule indicator: implications for quantification of cytosolic Zn2+. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2366–2371 10.1021/cb4003859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozym R. A.; Thompson R. B.; Stoddard A. K.; Fierke C. A. (2006) Measuring picomolar intracellular exchangeable zinc in PC-12 cells using a ratiometric fluorescence biosensor. ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 103–111 10.1021/cb500043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenburg L. H.; Hessels A. M.; Ebberink E. H.; Arts R.; Merkx M. (2013) Robust red FRET sensors using self-associating fluorescent domains. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2133–2139 10.1021/cb400427b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J. G.; Weaver A. L.; Qin Y.; Park J. G.; Stoddard C. I.; Lin M. Z.; Palmer A. E. (2012) New alternately colored FRET sensors for simultaneous monitoring of Zn2+ in multiple cellular locations. PLoS One 7, e49371. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V.; Grossmann G.; Vinkenborg J. L.; Merkx M.; Thomine S.; Frommer W. B. (2014) Dynamic imaging of cytosolic zinc in Arabidopsis roots combining FRET sensors and RootChip technology. New Phytol. 202, 198–208 10.1111/nph.12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo E. A.; Meur G.; Rutter G. A. (2011) Glucose regulates free cytosolic Zn2+ concentration, Slc39 (ZiP), and metallothionein gene expression in primary pancreatic islet beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25778–25789 10.1074/jbc.M111.246082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y.; Dittmer P. J.; Park J. G.; Jansen K. B.; Palmer A. E. (2011) Measuring steady-state and dynamic endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi Zn2+ with genetically encoded sensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 7351–7356 10.1073/pnas.1015686108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. G.; Qin Y.; Galati D. F.; Palmer A. E. (2012) New sensors for quantitative measurement of mitochondrial Zn2+. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1636–1640 10.1021/cb300171p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers T. H.; Appelhof M. A.; de Graaf-Heuvelmans P. T.; Meijer E. W.; Merkx M. (2007) Ratiometric detection of Zn(II) using chelating fluorescent protein chimeras. J. Mol. Biol. 374, 411–425 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkenborg J. L.; van Duijnhoven S. M.; Merkx M. (2011) Reengineering of a fluorescent zinc sensor protein yields the first genetically encoded cadmium probe. Chem. Commun. 47, 11879–11881 10.1039/c1cc14944j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek B. A.; Zawadzke L. E.; Berg J. M. (1993) Independence of metal binding between tandem Cys2His2 zinc finger domains. Protein Sci. 2, 1313–1319 10.1002/pro.5560020814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Moss L. G.; Phillips G. N. Jr. (1996) The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1246–1251 10.1038/nbt1096-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. M.; Morgan H. E.; Smart K.; Zahari N. M.; Pumford S.; Ellis I. O.; Robertson J. F.; Nicholson R. I. (2007) The emerging role of the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters in breast cancer. Mol. Med. 13, 396–406 10.2119/2007-00040.Taylor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. M.; Vichova P.; Jordan N.; Hiscox S.; Hendley R.; Nicholson R. I. (2008) ZIP7-mediated intracellular zinc transport contributes to aberrant growth factor signaling in antihormone-resistant breast cancer Cells. Endocrinology 149, 4912–4920 10.1210/en.2008-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCranor B. J.; Bozym R. A.; Vitolo M. I.; Fierke C. A.; Bambrick L.; Polster B. M.; Fiskum G.; Thompson R. B. (2012) Quantitative imaging of mitochondrial and cytosolic free zinc levels in an in vitro model of ischemia/reperfusion. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 44, 253–263 10.1007/s10863-012-9427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L.; Li G.; Yu C.; Jiang H. (2012) A ratiometric and targetable fluorescent sensor for quantification of mitochondrial zinc ions. Chem. - Eur. J. 18, 1050–1054 10.1002/chem.201103007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K. J.; Pinton P.; Varadi A.; Tacchetti C.; Ainscow E. K.; Pozzan T.; Rizzuto R.; Rutter G. A. (2001) Dense core secretory vesicles revealed as a dynamic Ca2+ store in neuroendocrine cells with a vesicle-associated membrane protein aequorin chimaera. J. Cell Biol. 155, 41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlden J. M.; Hutcheson I. R.; Jones H. E.; Madden T.; Gee J. M.; Harper M. E.; Barrow D.; Wakeling A. E.; Nicholson R. I. (2003) Elevated levels of epidermal growth factor receptor/c-erbB2 heterodimers mediate an autocrine growth regulatory pathway in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells. Endocrinology 144, 1032–1044 10.1210/en.2002-220620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein A., Amadai N., Hoover K., Vale R., and Stuurman N. (2010) Computer Control of Microscopes using μManager, (Ausubel F. M., Ed.) John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A.; Rasband W. S.; Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.