To The Editor

Food allergy has been estimated to affect nearly 5% of adults and 8% of children, and to be increasing in prevalence. 1, 2 Our understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of food allergy, particularly to the major food allergens of peanut, tree nut, egg, milk, fish, shellfish, wheat, and soy, have been largely built from studies of food allergy in children and infants: however, less is known about food allergy in adults. Although it is common for childhood food allergies to milk, egg, soy, or wheat to be outgrown, those to fish or shellfish have been suggested to develop in adulthood and/or to persist.3,4. Indeed, in a previous large, random, telephone-based study focused specifically on seafood and fish allergy in the United States, 60% and 39% of these respective allergies were ascribed to developing in adulthood rather than during childhood. Here, our primary objective was to determine the prevalence of adult-onset food allergy, with secondary objectives of examining the characteristics of these patients further, including the assessment of additional common allergens.

By using the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse, medical records of patients who were seen by allergy physicians at the Northwestern University adult allergy clinics and who received a diagnosis of food allergy (based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes 693.1, 995.3, 558.3, V15.05, 708.0, 975.60, 995.61, 995.62, 995.63, 995.64, 995.65, 995.66, 995.67, 995.68, v13.81) underwent retrospective chart review. Patients were deemed eligible if they had all of the following: (1) 1 of the diagnosis codes, (2) a documented history consistent with IgE-mediated allergy to food, (3) a demonstrated positive skin prick test (SPT) to the food, and (4) a diagnosis of food allergy occurring only after the age of 18 years old (determined from the patient's date of birth to time of diagnosis). A history consistent with IgE-mediated allergy to food was defined as the onset of symptoms, including hypotension, wheezing, urticarial, angioedema, vomiting, or abdominal cramping that occurred minutes to 3 hours after ingestion; whereas a positive SPT was defined as more than 3 mm higher than the saline solution control. Exclusion criteria was based on (1) an inconsistent history or negative SPT, and (2) a history consistent with oral allergy syndrome. The Northwestern Institutional Review Board Committee approved this study (STU00061627).

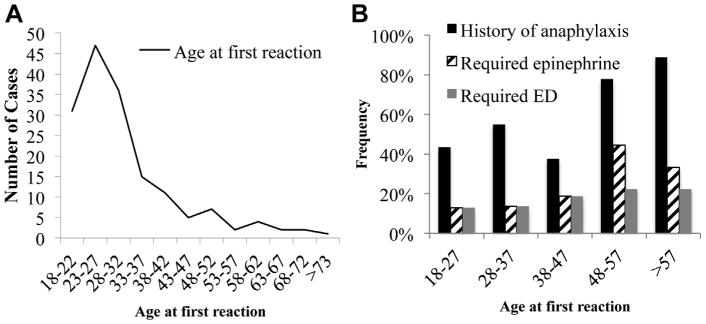

From 1111 charts assessed, 171 cases were determined to meet the age-restricted inclusion criteria, which suggests that at least 15% of patients with an initial food allergy diagnosis code were adult-onset food allergy. As shown in Figure 1,A, the age of first reaction showed a wide range but peaked during the early 30s (mean, 31 years, range, 18-86 years). The available documented food allergy–associated responses within all cases were 124 of 170 patients who reported cutaneous reactions (73%), 83 of 168 reported a history of anaphylaxis (49%), 121 of 149 reported a requirement for an epinephrine prescription (81%), and 35 of 62 indicated that a visit to the emergency department had been necessary (56%). Interestingly, the history of anaphylactic episodes, epinephrine prescription requirement, and emergency department visits significantly associated with the age at time of initial diagnosis (P = .014 by linear regression analysis), which suggests that an older age at time of diagnosis is associated with higher risk for severe reactions (Figure 1,B). In evaluating other characteristics of these patients, we observed a female versus male dominated bias (109 [64%] vs 62 [36%]; P = .0003, χ2 test), which contrasts with the male dominance described in pediatric food allergy.2 We also identified a number of comorbid allergic diseases, particularly dominated by allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis, although asthma was less evident (see Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Because the use of acid suppressive medications has been suggested to predispose towards food allergy sensitization,5 we also examined this. Current prescription of antacid therapies was seen in 19% of all of the patients, not different from current estimates of incidence of gastroesophageal reflux in the United States.6 A history of any atopic condition was present in 67% of the patients, with allergic rhinitis being the most common atopic disease (51% of all participants). We also did not detect any major differences in medical comorbidities between those younger than 30 years old and those older 30 years old.

Figure 1.

The incidence of adult-onset food allergy by age (A) and frequency of reactions, determined by history, requirement for epinephrine prescription and emergency department (ED) visit, by age group (B) (n = 78 for ages 18-27 years old, n = 51 for ages 28-37 years old, n = 16 for ages 38-47, n=9 for ages 48-57 years old, n = 9 for ages >57 years old).

We next investigated the specific trigger foods responsible, based on the criteria of reaction history and positive SPT. As shown in Figure 2, the 5 most common food allergies determined, in decreasing order of frequency, were shellfish (54%), tree nut (43%), non-shell fish (15%), soy (13%), and peanut (9%). Twenty-eight of 171 patients (16.4%) were determined to be allergic to more than 1 food. These findings indicated that several of the major food allergen groups commonly seen in childhood and those reported to persist into adulthood also are commonly found as triggers in the allergic reactions observed in newly diagnosed, adult-onset food allergy.

Figure 2.

The incidence of specific food triggers for adult-onset food allergy, determined by clinical history and positive SPT. Other food allergies (n = 1) included the following: ackee fruit, apple, basil, buckwheat, beef, homemade beer, celery, corn, cottonseed oil, ginger, green beans, green pepper, mango, nectarine, paprika, peach, pork, potato, spinach, tomato, and zucchini.

A limitation of our study is that the patients did not undergo double-blinded, placebo-controlled oral food challenge as recommended by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guidelines for food allergy diagnosis7; however this is not standard practice in most adult clinics, and so we relied on the criteria outlined above. It remains possible that we failed to capture all possible cases, for example, by excluding patients due to inconclusive SPT, and that we underestimated the overall prevalence of adult-onset food allergy. Conversely, there may be some patients who meet our inclusion criteria of history and positive SPT and who would fail to react to food challenge. In addition, the retrospective nature of our study meant that some key questions lacked full response rates. A prospective study will likely provide a more complete picture of this patient group. We also did not include several diagnosis codes, due to their low frequency in our Enterprise Data Warehouse system, and our study assumes that the codes we selected reliably captured an unbiased population of patients.

Our findings support the importance of understanding food allergy of adults, particularly in understanding that new-onset food allergy is evident across a broad age range during adulthood. In agreement with previous studies, shellfish and fish are most common within this population, but results of our data indicate that all the major food allergen groups are represented. The breadth of potential allergens observed in the adult population is a key consideration for diagnosis and avoidance advice by clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Table E1. Comorbidities

Clinical Implication.

Food allergy has mostly been studied in childhood and with infants but is recognized to also develop in adulthood. We sought to examine aspects of adult-onset food allergy, including age of onset and trigger foods.

Acknowledgments

P. J. Bryce received support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant 2R01AI076456 and R56AI105839.

T. Kamdar is employed by Northwest Community Hospital Medical Group. P. J. Bryce has received research support from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (2R01AI076456-06A1 and R01AI05839-06A1) and the Sunshine Charitable Foundation; has received consultancy fees from Essentials Pharmaceuticals; and is employed by Northwestern University. C. Lau is employed by Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago. R. Gupta has received consultancy fees from Allergen Research Corporation and Mylan; has received research support from Mylan and FARE; has received lecture fees from Grand Rounds; and receives royalties from CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform for his book, The Food Allergy Experience.

Footnotes

There are no financial relationships with biotechnology and/or pharmaceutical manufacturers that have an interest in this work.

Conflicts of interest: The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:291–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.020. quiz 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burks AW, Tang M, Sicherer S, Muraro A, Eigenmann PA, Ebisawa M, et al. ICON: food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:906–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of seafood allergy in the United States determined by a random telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Untersmayr E, Bakos N, Scholl I, Kundi M, Roth-Walter F, Szalai K, et al. Anti-ulcer drugs promote IgE formation toward dietary antigens in adult patients. FASEB J. 2005;19:656–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3170fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubenstein JH, Chen JW. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:S1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table E1. Comorbidities