Abstract

The rate of dissociation of a DNA-protein complex is often considered to be a property of that complex, without dependence on other nearby molecules in solution. We study the kinetics of dissociation of the abundant E. coli nucleoid protein Fis from DNA, using a single-molecule mechanics assay. The rate of Fis dissociation from DNA is strongly dependent on the solution concentration of DNA. The off-rate (koff) of Fis from DNA shows an initially linear dependence on solution DNA concentration, characterized by an exchange rate of kex ≈ 9×10−4 s−1 (ng/μl)−1 for 100 mM univalent salt buffer, with a very small off-rate at zero DNA concentration. The off-rate saturates at approximately koff,max ≈ 8×10−3 s−1 for DNA concentrations above ≈ 20 ng/μl. This exchange reaction depends mainly on DNA concentration with little dependence on the length of the DNA molecules in solution or on binding affinity, but does increase with increasing salt concentration. We also show data for the yeast HMGB protein NHP6A showing a similar DNA-concentration-dependent dissociation effect, with faster rates suggesting generally weaker DNA binding by NHP6A relative to Fis. Our results are well-described by a model with an intermediate partially-dissociated state where the protein is susceptible to being captured by a second DNA segment, in the manner of “direct transfer” reactions studied for other DNA-binding proteins. This type of dissociation pathway may be important to protein-DNA binding kinetics in vivo where DNA concentrations are large.

Keywords: binding kinetics, biomolecule interactions, affinity, unbinding, off-rate

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Once a DNA-binding protein has bound to a location along a double-helix DNA, the rate of its dissociation, koff, is often considered to be independent of other macromolecules in solution. One usually considers koff to be a property of the protein-DNA complex, with units of a pure rate (s−1). Balancing this off-rate against a diffusion-limited on-rate described by a binary reaction constant kon (with units of M−1 s−1) gives the familiar hyperbolic binding isotherm (Pbound = c / [c + Kd]), with a concentration-independent dissociation constant Kd = koff / kon, describing the bulk protein concentration c at which the binding site is 50% occupied by the protein. This type of model is often used to analyze data for protein-DNA interactions, and implicitly assumes that there are distinct bound and unbound states, without a significant kinetic role of other incompletely bound states present along the kinetic unbinding pathway.

However, given that even small DNA-binding proteins are macromolecules that bind nucleic acids via an array of noncovalent bonds, it is plausible that dissociation of a protein from DNA may involve intermediate, incompletely bound states, and that during the time that those intermediates are present, additional macromolecules may be able to affect rebinding or dissociation, effectively competing with the partially bound protein for its binding site 1. Many DNA-binding proteins are dimeric in structure, and release of a monomer from a half-site provides a reasonable mechanism to generate a partially bound intermediate2; 3. Whatever the detailed mechanism, any “facilitated dissociation” effect of this type is likely to be important for dynamics of protein binding in vivo, where there are high concentrations of proteins competing for DNA binding sites 1; 2; 3.

This effect is often not considered for DNA-binding proteins, but in fact a number of experiments have recently observed dissociation rates of proteins from DNA that depend on the solution concentration of protein. Double-stranded-DNA (dsDNA)-binding proteins which have displayed protein-solution-dependent dissociation rates include Fis, a small (23 kD) dimeric DNA-bending nucleoid protein from E. coli 1; the monomeric yeast chromatin protein NHP6A 1; the bacterial copper-dependent transcription factor CueR 4; and T7 DNA polymerase 5. Similar effects have been observed for the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding proteins E. coli SSB 6, in interactions between histones and the transcription factor LexA 7, and for human RPA 8. In addition, a recent paper has observed similar behavior for dissociation of a ssDNA oligonucleotide from a complementary ssDNA strand 9. While many of these observations have used single-molecule methods that allow direct observation of molecule binding kinetics, stop-flow kinetic measurements have seen similar effects for SSB-ssDNA interactions6.

For Fis, a fluorescent protein single-DNA-based assay determined a nearly linear dependence of off-rate on solution Fis concentration for Fis concentrations up 50 nM 1, with koff ≈ koff,0 + kex c, where koff,0 ≈ 1 × 10−3 s−1 and kex ≈ 6 × 104 M−1 s−1. The small value of kex relative to a diffusion-limited reaction rate (typically ≈109 M−1 s−1 1; 10) suggested that dissociation occurred via a relatively rarely appearing intermediate state. Theoretical work based on this general idea has provided a quantitative rationalization of this effect, based on the hypothesis that when an incompletely dissociated state appears, molecules in solution can block rebinding of the protein, facilitating its eventual dissociation 2; 3.

The Fis homodimer has two helix-turn-helix motifs which bind successive major grooves of DNA along a 21 bp binding window11. Both DNA minor groove compression and bending of the helix axis are required to form a Fis-DNA complex. For dimeric proteins like Fis, binding and unbinding may occur by successive interactions with half-binding-sites, and a partially bound intermediate state (or states) may be susceptible to competition with other molecules in solution. We stress that the general mechanism of appearance of an intermediate that may have rebinding kinetics influenced by nearby molecules in solution does not require a dimeric structure of either binding partner.

This mechanism for protein-stimulated dissociation of protein from DNA parallels the more familiar phenomenon of “intersegment transfer” of proteins from one DNA location to another, via formation of a DNA-protein-DNA intermediate 10; 12. Double-helix to double-helix “direct transfer” processes have been observed for a variety of DNA-binding ligands and proteins, including ethidium bromide 13; 14, bacterial transcription factors CAP and Lac repressor 15; 16, restriction enzymes 17, eukaryote transcription factors 18; 19; 20, HMGB proteins 21, and histones 22; 23. Direct transfer kinetics also have been observed for transfer of proteins between ssDNA segments, notably for RecA 24 and SSB 25; 26; 27. Acceleration of more complex DNA-to-DNA protein transfer reactions by increased DNA segment concentration has also been observed, for example chromatin-remodeling-factor-aided displacement of core histones 28. Direct transfer thus has been observed for a wide range of DNA-binding ligands and proteins, indicating the ability for proteins to move directly from DNA segment to DNA segment to be rather common.

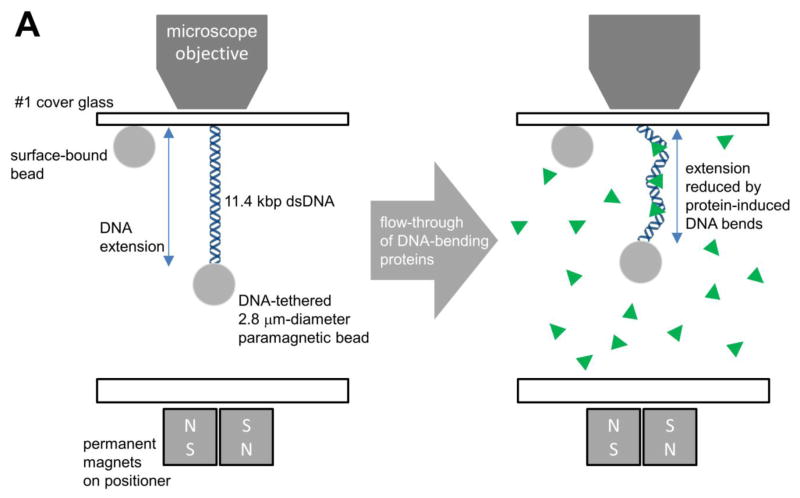

Here we report results of a quantitative study of DNA-stimulated dissociation and DNA to DNA direct transfer of Fis, which has had its protein-stimulated dissociation studied in detail1. We use a magnetic tweezers approach to detect protein unbinding through changes in the mechanical properties of the protein-DNA complex (Fig. 1A). The amount of DNA compaction was used to measure the amount of Fis bound 29, an approach that has been exploited in prior experiments23; 30; 31; 32; 33. We find that DNA segments in solution drastically accelerate the dissociation of Fis from DNA, presumably via direct transfer of the protein to the competitor molecules. While the off-rate initially increases linearly with solution DNA concentration, it then saturates above a certain DNA segment concentration. We find that the reaction is mainly dependent on the net concentration of DNA base pairs in solution, rather than on the length of the DNAs or on their sequence (i.e., on their affinity for Fis). We also show that a similar DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation effect occurs for the yeast chromatin-associated protein NHP6A. Notably, NHP6A binds DNA via a single-HMG box, indicating that this effect for double-helix-binding proteins does not require two DNA-binding domains.

Fig. 1. Increasing concentrations of Fis gradually compact DNA.

End-to-end extension as a function of force for 10 kb DNA in solution with Fis. 20 nM Fis solution shows the greatest change in length relative to naked DNA at 0.3 pN in comparison with other concentrations (10 nM, 20 nM 50 nM, 100 nM, and 200 nM). When the concentration of protein was greater than 20 nM, the length of the DNA began to return towards that of naked DNA. Results of N=3 independent measurements were averaged to obtain each data point; all bars represent standard errors.

Results

Dependence of DNA compaction on Fis concentration

We first carried out equilibrium binding experiments to measure the amount of compaction of the 10 kb tethered DNA as a function of Fis concentration in 100 mM KGlu buffer. In a series of experiments at Fis concentrations from 0 to 200 nM, we measured the extension of DNA at a series of forces from approximately 0.1 pN to 10 pN (Fig. 1B), ascertaining that each measurement was in mechanical-chemical equilibrium by comparison of measurements taken over a few-minute interval. As we increased the Fis concentration up from zero, we observed a gradual compaction (reduction of extension) of the molecule until 20 nM Fis was reached. This is the expected effect for a DNA-bending protein such as Fis; the added bends introduced by the protein binding to the double helix lead to an effective shortening of its persistence length, and therefore a compaction of it against applied force 34; 35; 36; 37. In this regime, the degree of compaction can be taken as a proxy for protein binding, since the compaction is monotonically increasing with solution protein concentration and therefore binding. The gradual increase of compaction with protein concentration in the 0 to 20 nM Fis concentration range is indicative of non-cooperative binding behavior in this concentration range, in accord with observation of gradual and non-cooperative binding in EMSA experiments 38.

For larger concentrations of Fis (Fig. 1B, 50 to 200 nM), the compaction effect was observed to be reduced, as has been observed for other DNA-bending proteins 23; 32; 38; 39. This compaction-reversal effect is possibly due to gradually more ordered binding of protein along the double helix, with bends phased inside a protein-coated stiff filament 23; 38; 39. In this study, all experiments are done in the low-concentration regime (at or below 20 nM), to allow us to consider DNA compaction to be monotonic as a function of amount of bound protein. The data of Fig. 1B agree with data from similar prior measurements36; 38.

The data for 20 nM Fis indicates that the amount of compaction (length reduction in microns) in protein solution, relative to buffer alone is larger at lower forces. We decided to focus on a force level of 0.3 pN, where there is a extension change of the 10 kb DNA from about 2.3 to 1.4 μm as Fis concentration is raised from 0 to 20 nM, but also where there are not strong and slow random-coil fluctuations of the molecule that make extension measurements problematic. This force is also sufficient to suppress contacts between different points along the DNA molecule via thermally excited loop formation, reducing the likelihood of direct transfer reactions along the micromanipulated DNA.

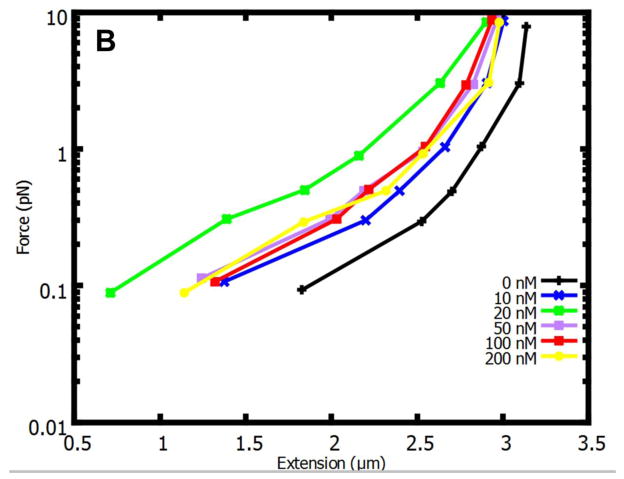

Fis spontaneously dissociates to macromolecule-free buffer extremely slowly

We carried out experiments to measure the compaction by Fis before and after replacement of Fis solution with buffer alone. In a series of 5 trials we measured the extension of 10 kb DNA tethers in protein-free 100 mM KGlu buffer; we then replaced the buffer with 20 nM Fis in 100 mM KGlu solution and measured extension again, and we then finally replaced the protein solution with protein-free 100 mM KGlu buffer and measured extension a third time (Fig. 2A). The result was that the naked DNA in KGlu buffer had an extension of ≈2.3 μm before protein was added, an extension of ≈1.7 μm after protein was added, and then maintained the ≈1.7 μm extension after the protein solution was removed. Kinetics of extension for a typical trial are shown in Fig. 2B; there is a very slow return of the extension towards the naked DNA level (heavy dashed black line), with less than a 20% return to the naked DNA level over 1200 s. Thus, in macromolecule-free solution, Fis is highly stable on DNA, dissociating only very slowly, in accord with prior studies1; 11; 40.

Fig. 2. Fis compacts DNA held at 0.3 pN and is stably bound after protein solution is removed.

(A) Bars show length of DNA before addition of protein solution (left), after replacement of buffer by 20 nM Fis (middle) and following replacement of protein solution with buffer (right). When Fis is added, the extension is reduced by about 30%; there is little or no return of the length to the naked DNA length following introduction of protein-free buffer. N=5 for each data point. (B) Kinetics of a typical run showing very slow change in extension of DNA at 0.3 pN following replacement of protein solution with buffer at t=4100 s. Note that for times shortly before t=4100 s the force was larger (1 pN) to keep the magnetic bead from being pushed to the surface by the buffer replacement.

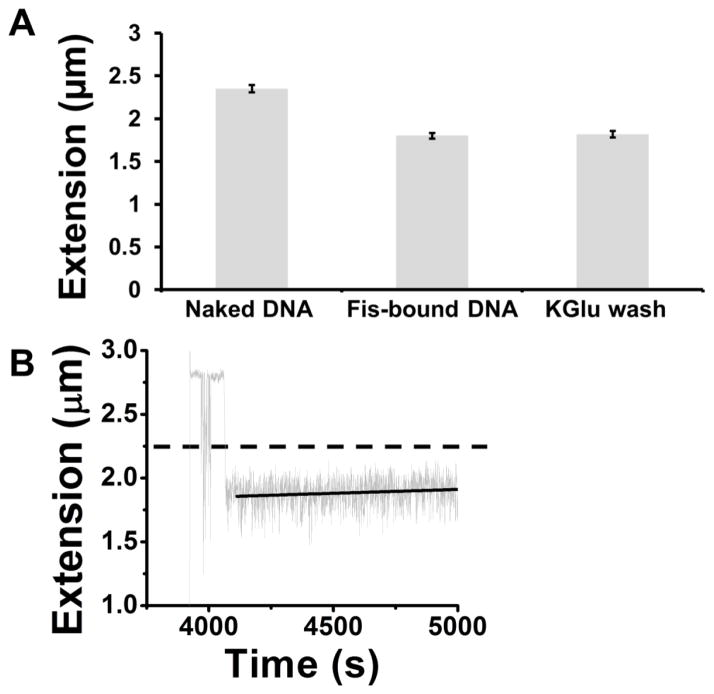

Fis dissociation from DNA is stimulated by DNA segments in solution

Having established the stability of Fis-DNA complexes after introduction of protein-free solution, we carried out similar experiments where a further solution exchange step was added, to introduce DNA segments into solution. Following washing away of the protein-containing solution by protein-free solution, we then brought herring sperm DNA (HS-DNA) segments (average size 750 bp) in 100 mM KGlu buffer into the flow cell. Following this third step, we observed a DNA-concentration-dependent recovery of the 10 kb DNA tether extension back towards its naked DNA length. Fig. 3A–C shows kinetic results for experiments with 2, 20 and 100 ng/μl HS-DNA in solution, which show a gradual increase in the rate with increasing DNA fragment concentration.

Fig. 3. DNA segments in solution accelerate dissociation of Fis from a 10 kb DNA.

Following binding of 20 nM Fis and washing out of the Fis solution, DNA segments in buffer were introduced, leading to a return of DNA extension to its naked DNA length. Time courses for extension at (A) 2 ng/μl, (B) 20 ng/μl and (C) 100 ng/μl herring sperm DNA (HS-DNA) are shown; in addition we carried out experiments using 5, 10 and 50 ng/μl DNA. Protein-free buffer washes were administered before the addition of competitor DNA so that no excess protein was present in the flow cell. (D) Off rate koff inferred from rates of relaxation of DNA length as a function of HS-DNA concentration. When no competitor DNA was added, the rate was undetectably small, but increased as DNA concentration was increased, up to roughly 20 ng/μl. However, once the DNA concentration exceeded 20 ng/μl the rate of release of protein leveled off.

Each time course was fit to an exponential decay, giving an apparent Fis off-rate (koff). We averaged the resulting rates obtained from a series of these experiments at DNA concentrations of 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 ng/μl (for which N=3, 4, 3, 3, 9, 5 and 5, respectively), obtaining the exchange rate vs. concentration data shown in Fig. 3D. The off-rate at zero concentration is approximately 3×10−4 s−1 and increases to near 8×10−3 s−1 as DNA fragment concentration is increased to 20 ng/μl. For higher DNA fragment concentrations, the off-rate is essentially constant, indicating that the facilitation of dissociation of protein is saturated.

To verify that the majority of the Fis protein was in fact dissociating, rather than simply having its DNA-bending and compaction function interfered with by the DNA fragments, we carried out a small number of similar single-DNA experiments, but where Fis occupation was directly measured using fluorescence intensity, using a transverse magnetic tweezers setup 1. After finding a tethered 48.5 kb λ-DNA using bright-field imaging, 200 nM GFP-Fis in 100 mM KGlu experiment buffer was introduced into the flow chamber, and then washed out with protein-free experiment buffer. Then, HS-DNA fragments (0, 5 or 50 ng/μl) were introduced into the flow chamber, after which fluorescence images were acquired every 40 seconds. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Little fluorescence decay is observed for 0 ng/μl DNA (Fig. S1, blue squares) over a 15 minute period, compared to robust decays observed in experiments with 5 and 50 ng/μl HS-DNA (Fig. S1, green diamonds, red circles). The rates for the decays (0.0033 +/− 0.00081 s−1 for 5 ng/μl HS-DNA and 0.0062 +/− 0.0018 s−1 for 50 ng/μl) are comparable to those obtained in the vertical magnetic tweezers experiment (compare with Fig. 3D). These experiments verify that the extension changes observed with the vertical magnetic tweezers correspond to dissociation of Fis from DNA.

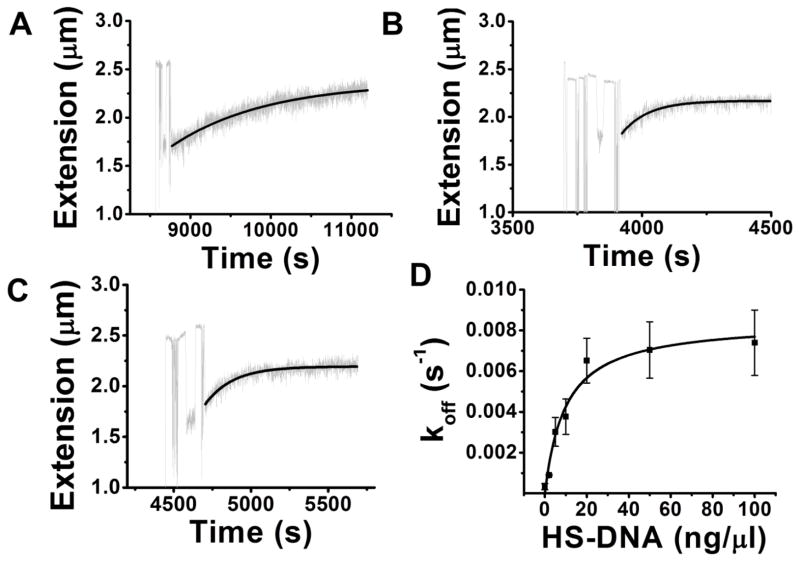

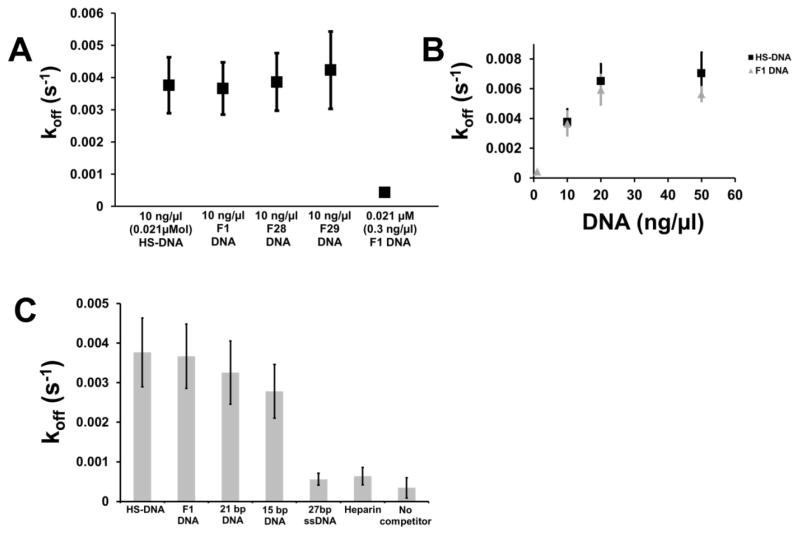

Dissociation rates show little dependence on DNA fragment length and sequence

Returning to vertical magnetic tweezers experiments, we next examined how much the length of the DNA segments and their sequence affected the facilitated dissociation effect. Therefore we carried out similar experiments, but using shorter 27 bp dsDNA molecules. We chose to use molecules of sequence which had been previously characterized as to Fis binding affinity; in decreasing order of Fis binding affinity, these molecules are called F1 (previously measured Kd=0.2 nM), F28 (Kd=30 nM) and F29 (Kd=400 nM) 41. Dissociation rates were measured in experiments where initially 20 nM Fis was bound to DNA in 100 mM KGlu buffer, then where the protein solution was washed away using 100 mM KGlu protein-free buffer, and then where 10 ng/μl 27 bp F1, F28 and F29 DNAs were added. Results comparing these different DNAs are shown in Fig. 4A, along with the data for 10 ng/μl HS-DNA (average length 750 bp). Fis dissociation rates were nearly the same for all these molecules at the same mass concentration (10 ng/μl), indicating that the main factor controlling the facilitated dissociation effect is overall base-pair concentration rather than length or sequence of DNA fragment.

Fig. 4. Rate of DNA-facilitated protein dissociation depends mainly on base pair concentration and not on length and sequence of solvated molecules.

(A) In a series of experiments as in Fig. 3, competitor DNA in buffer was introduced, following binding of 20 nM Fis to 10 kb DNA and washing away of protein solution by buffer, and the rate of removal of protein from DNA was measured. Data points (each N=3) from left to right show results for herring sperm DNA segments (10 ng/μl, N=3), high-Fis-binding-affinity 27 bp F1 DNA (10 ng/μl, N=3), medium-affinity 27 bp F28 DNA (10 ng/μl, N=3), and low-affinity 27 bp F29 DNA (10 ng/μl, N=3), and a low concentration of F1 DNA (0.021 ng/μl, N=3) which corresponds to roughly same molecular (molar) concentration in base pairs as the ~750 bp HS-DNA fragments. The 10 ng/μl experiments all show about the same facilitated dissociation rate, regardless of DNA length or sequence (Fis binding affinity). (B) Concentration dependence of dissociation of Fis from DNA on DNA fragment concentration, comparing results for HS-DNA (black squares; for 10, 20 and 50 ng/μl, N=3, 9 and 5) to 27 bp F1 DNA (gray triangles, N=3 for each concentration). The F1 DNA shows a similar rate versus concentration behavior to the HS-DNA segments, indicating that the main factor controlling the facilitated dissociation is base pair concentration rather than molar concentration of duplex fragments or sequence. (C) Competitor DNA length dependence of dissociation. As length of DNA is reduced from ≈ 750 bp (HS-DNA) to 27 bp F1 DNA, 21 bp DNA and to 15 bp DNA, all at 10 ng/μl, there is a mild reduction in the rate of release of Fis from DNA. Use of either 10 ng/ml 27 bp ssDNA or heparin shows a much slower dissociation rate, indicating a requirement of dsDNA.

We carried out a series of experiments with the 27 bp F1 dsDNA at varied concentrations to check whether the mass concentration dependence of facilitated dissociation driven by that molecule matched that obtained with HS-DNA. We first measured the rate of dissociation of Fis (bound at 20 nM concentration) driven by 0.3 ng/μl (21 nM) of 27 bp F1, which corresponds to the same molar (molecular) concentration as 10 ng/μl HS-DNA. The result was a much slower dissociation rate than seen for experiments at 10 ng/μl (Fig. 4A, rightmost data point), again in accord with overall base-pair concentration controlling the dissociation rate. In a series of such experiments using 27 bp F1 DNA we obtained dissociation rates that nearly matched those from HS-DNA, when plotted as a function of mass concentration (Fig. 4B). This verified that the major factor controlling DNA-facilitated dissociation was the overall mass, i.e., base-pair concentration.

Given that the size of a Fis binding site is approximately 21 base pairs, we were curious if even shorter DNAs would lead to a weaker facilitated dissociation effect. Fig. 4C shows the results for a series of experiments using DNA lengths (~750 bp HS-DNA, 27 bp F1 DNA, 21 bp DNA and 15 bp DNA) all at the same mass concentration of 20 ng/μl. Although the rate of dissociation does go down with DNA length, the effect of length is weak, with 15 bp dsDNA driving dissociation at about 75% of the rate observed for HS-DNA.

We also were curious whether double helix structure was required for the facilitated dissociation effect, so we carried out experiments using 27 base single-stranded DNA at a concentration of 10 ng/μl. The result was that little dissociation occurred, and at a very slow rate (Fig. 4C, 5th bar). Similarly, heparin (a highly negatively charged sulfated glycosaminoglycan) at 10 ng/μl causes only a small amount of slow dissociation (Fig. 4C, 6th bar). These experiments indicate that the facilitated dissociation effect requires DNA double helix structure, and not just the DNA backbone or a heavily negatively charged molecule.

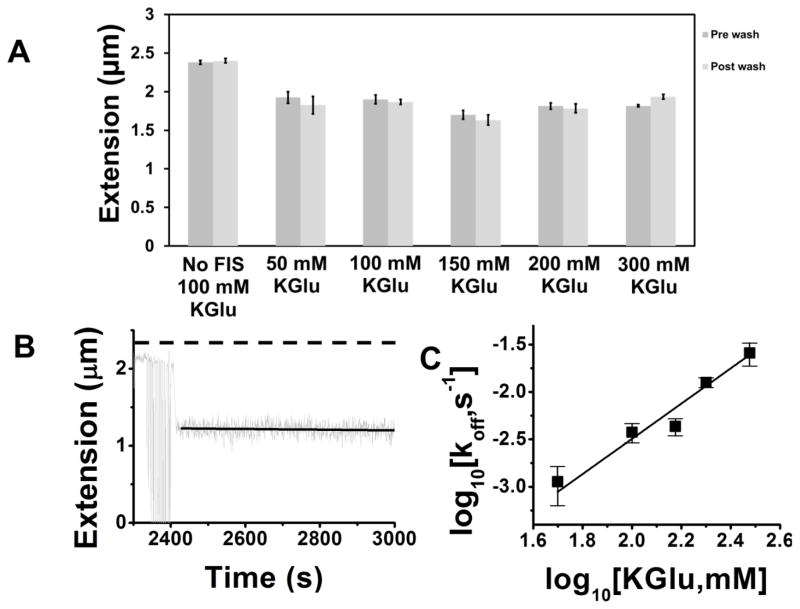

Dissociation rates are faster at higher salt concentration

We next studied how overall KGlu concentration affected the facilitated dissociation rates, given the appreciable salt-dependent electrostatic contribution to many protein-DNA interactions 42, including those of Fis 38. In a series of experiments using varied KGlu concentration (50 mM through 300 mM, see Fig. 5A) we checked that after binding Fis at 20 nM protein concentration, the protein remained on the 10 kb DNA tethers following replacement of the protein solution with protein-free buffer. The results are shown in Fig. 5A, and indicate that there is little change in 10 kb DNA extension and therefore in amount of bound Fis resulting from replacing the protein solution with protein-free buffer, for KGlu concentrations of up to 200 mM. Use of 300 mM KGlu (rightmost bars of Fig. 5A) led to a small change in extension due to the replacement of protein solution with protein-free buffer, indicating that most of the protein remained on the DNA even for that case (compare with leftmost bars of Fig. 5A for naked DNA in 100 mM KGlu). A kinetic trace is shown in Fig. 5B, indicating a stable level of DNA compaction and therefore Fis occupation, in an experiment where binding of 20 nM Fis in 200 mM KGlu was followed by incubation with 200 mM KGlu buffer.

Fig. 5. Solution salt concentration dependence of facilitated dissociation of Fis from 10 kb DNA driven by DNA segments.

Experiments of the type shown in Fig. 3 were carried out using different solution salt (KGlu) concentrations of 50 (N=4), 100, 150, 200 and 300 mM. Initially Fis at 20 nM concentration was bound to DNA in buffer of a given salt concentration, then the same buffer was used to wash the protein solution away, and finally DNA segments were introduced in the same buffer. (A) Comparisons of extensions of DNA at 0.3 pN force before and after the buffer wash following protein binding indicate that little or no Fis is lost by spontaneous dissociation over the time period of the wash (4 min), with the most recovery of length occurring in the 300 mM KGlu case (N=3). (B) Kinetics of DNA length for a 200 mM KGlu experiment following wash at t=2400 s, showing little or no extension recovery. (C) Results for the rate of extension recovery (release of protein from the 10 kb DNA by 10 ng/μl HS-DNA solution following binding at 20 nM Fis) as a function of KGlu concentration (for 50, 100, 150, 200 and 300 mM KGlu, N=4,3,3,7 and 3). The rate of release of Fis increases with KGlu concentration, following a power law (straight line on log-log graph) Rate ∝ [KGlu]1.9±0.3.

Results for the rate of DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation of Fis from pNG1175 DNA, following binding at 20 nM Fis concentration and a wash with protein-free buffer, and then addition of 10 ng/μl HS-DNA in the same buffer, are shown in Fig. 5C. The rate increased quickly with salt concentration, increasing from about 1×10−3 s−1 to about 2×10−2 s−1 as KGlu concentration was changed from 50 to 300 mM. When plotted on logarithmic axes, the data fit well to a straight line of slope 1.9±0.3 suggesting a power law dependence of dissociation rate ∝ [KGlu]1.9. Increased salt concentration accelerates the overall rate of DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation of Fis from DNA.

We also carried out measurements of off-rate of Fis from DNA as a function of HS-DNA concentration at a fixed salt concentration of 200 mM KGlu. Fig. S2 shows these results (gray triangles) compared to the 100 mM KGlu results of Fig. 3D (black squares). The rates are uniformly faster at the higher salt concentration, with a faster initial exchange rate constant, and a larger final saturation off-rate of 1.2×10−1 s−1 reached for HS-DNA concentrations above 10 ng/μl.

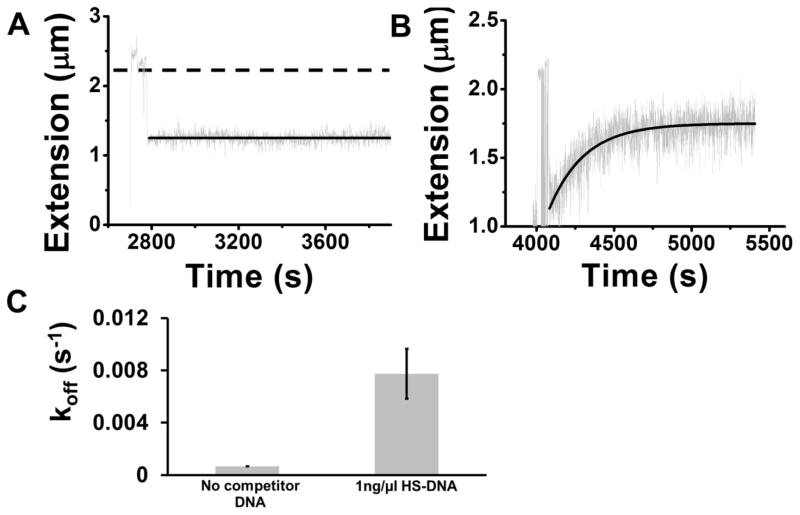

The yeast HMG box protein NHP6A shows DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation effects similar to those of Fis

We wanted to determine whether similar effects could be seen for another DNA-binding protein, and given that prior experiments had seen slow dissociation of NHP6A to 100 mM KGlu buffer 43 we carried out experiments examining the rate at which HS-DNA segments removed that protein from DNA. Fig. 6A shows the extension of pNG1175 DNA under 0.3 pN tension with NHP6A bound at 33 nM concentration in 100 mM KGlu buffer, after washing of the protein solution with protein-free buffer (2800 to 3800 s, solid line). The protein is stably bound to DNA and shows essentially no dissociation (solid black line, relative to dashed line showing length of naked DNA at the same tension). When 1 ng/μl HS-DNA segments were added, a gradual dissociation occurred (Fig. 6B). Averages of a series of experiments of this type yielded the average rates shown in Fig. 6C; 1 ng/μl HS-DNA leads to much faster dissociation of NHP6A than occurs in protein-free buffer. Although NHP6A is stably bound in the absence of dsDNA segments in solution, it is more susceptible to facilitated dissociation by DNA than is Fis, reflecting its overall weaker affinity for DNA.

Fig. 6. The yeast HMG-box protein NHP6A shows DNA-fragment-facilitated dissociation similar to that exhibited by Fis.

In experiments similar to those with Fis, 33 nM NHP6A was bound to 10 kb DNA in 100 mM KGlu buffer; the protein solution was then replaced with protein-free buffer. (A) Extension versus time following the wash (t=2800 s) with protein-free buffer (gray data and solid line) shows no return of extension towards the naked-DNA value (dashed line). (B) When 1 ng/μl of HS-DNA was added, DNA extension returned toward the naked DNA level, indicating release of protein from the DNA. (C) Rate of NHP6A dissociation facilitated by 1 ng/μl HS- DNA (right bar) is much faster than dissociation of NHP6A to protein-free solution (left bar).

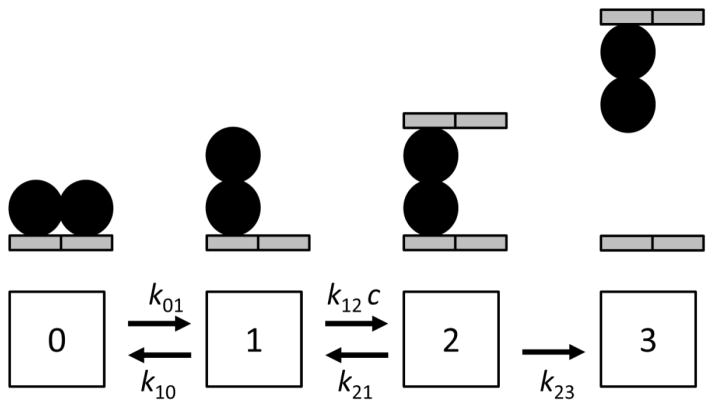

A model of facilitated dissociation via two intermediate states describes facilitated dissociation and its saturation

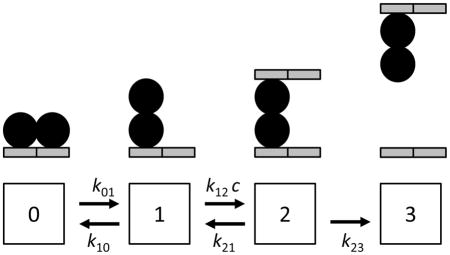

In our experiments we measure the time course of release of initially bound proteins, and we find that solution-phase DNA segments facilitate dissociation of the initially bound molecules. The experiments with Fis show a dissociation rate which initially increases with concentration, and which then saturates at a maximum dissociation rate. This saturation effect was not previously seen for protein-facilitated dissociation of Fis 1 but is readily apparent for DNA-facilitated dissociation (Fig. 3D). This behavior is readily produced by a simple model of dissociation where an initially well-DNA-bound protein (Fig. 7, state 0) can be thermally excited into an “activated”, partially bound state (state 1). In the activated state, the protein can bind to a second DNA segment (state 2) to form a ternary complex; the rate of binding of this second segment is proportional to the bulk DNA segment concentration c. From the ternary complex (state 2) either DNA segment can be released, leading either to release of the second segment (return to state 1), or complete release of the original DNA segment (state 3).

Fig. 7. Kinetic scheme for exchange of a protein between dsDNA segments.

A fully bound protein (state 0) can be partially released (state 1); in this state it may interact with a second DNA segment (state 2), which binds at a concentration (c) dependent rate. Then, the protein may dissociate from either dsDNA segment; if it dissociates from the original segment, it will transfer to the second dsDNA. The final transition is considered to be irreversible since it corresponds to the protein-dsDNA complex escaping and mixing with the bulk solution.

This type of reaction scheme has previously been used to describe transfer of RecA between ssDNAs (see Fig. 10 of Ref. 24), and to quantitatively analyze DNA-to-DNA transfer reactions involving ethidium bromide 14 and bacterial transcription factors 15. A feature of the present experiment is that we work under conditions of large excess of competitor DNA segments relative to tethered DNAs. A small amount of DNA (< 0.1 ng) is tethered in the flow cell, compared to the >200 ng of DNA brought in as a competitor into the ~100 μl flow cell volume at the low end of the competitor concentrations we have used (at higher DNA concentrations the excess is even greater). It is therefore reasonable to neglect the reaction from state 3 back to state 2; this is suppressed by a factor of more than 500 by the excess of competitor over tethered DNAs. Neglecting the rate from state 3 to 2 is further justified by our observation that we see complete recovery of the DNA extension to its “naked” value in even the lowest-DNA-concentration reactions (e.g., Fig. 3A). The fact that the final protein-transfer step is irreversible allows us to use an exact first-passage-time analysis with a simple result, instead of the more traditional and complex chemical reaction relaxation rate analysis 44 needed when the initial complex and competitor are at comparable concentrations.

We make three additional justified assumptions that simplify the analysis. First, we consider the rates k21 and k23 to be equal given that they correspond to nearly symmetric DNA-release transitions (relaxing this assumption does not change the predictions of the model but only modifies the interpretation of the fit parameters). Second, while in principle a transition directly from state 1 to fully dissociated protein can be added, because we see essentially no release of Fis without DNA segments in solution (Fig. 2B, Fig. 6A) we omit this process here (again this effect may be included if needed). We emphasize that the second-segment binding transition from 1 to 2 is the only point at which the bulk DNA concentration enters into the model, with k12 having units of (time concentration)−1. The other constants k01, k10, k21 and k23 are all intramolecular rates with units of (time)−1, corresponding to concentration-independent processes. Third, we suppose that the initially bound protein initially is in state 0, which is equivalent to assuming k01 ≪ k10, i.e., that state 1 is rarely populated.

For our experiment, it is convenient to compute the average time for an initially bound protein to dissociate as a function of bulk DNA segment concentration c, since this is just the inverse of the rates of Fig. 3D obtained from the fitting of the time courses to exponential decays. For the model of Fig. 7, assuming that the final dissociation reaction is irreversible, this amounts to computation of the mean first passage time from state 0 to state 3. This can be computed exactly using methods similar to those in Ref. 45:

| (1) |

where A and B are functions of the rates

| (2) |

The derivation of these formulae is included in the Supplementary Materials.

The reciprocal of (1) provides the rate for the exponential dissociation time course, i.e., koff = c / (A c + B). For small concentration (c ≪ B / A), the rate is c / B, and initially rises linearly with concentration. The “exchange rate constant” 1, or prefactor of concentration, is kex = 1 / B = [k01 / (k01+k10)] (k12 / 2). This can be understood as just the probability of occupation of state 1 in quasi-equilibrium with state 0 [k01/(k01+k10)] times the rate at which binding of the second DNA segment takes place (the factor of 2 arises from the symmetry between the rates of the two exit routes from state 2). In this low-concentration regime, the rate-limiting step is the binding of the second DNA segment (the transition from 1 to 2 with rate k12 c). A key point of this model is that despite the appearance of concentration dependence in only one microscopic on-rate (the transition from 1 to 2), there appears an emergent concentration dependence in the net off-rate (the transition from 0 to 3 considered as one process, and the transition observed experimentally).

For large concentration (c ≫ B / A), the rate saturates at a value of koff,max = 1 / A, which corresponds to the inverse of the total time to pass through the two transitions from 0 to 1 and from 2 to 3, since the concentration in the second-segment binding step from 1 to 2 is no longer rate-limiting. It should be noted that in this high-concentration regime, the apparent off-rate is nearly constant, despite the fact that incoming segments of DNA are responsible for the dissociation. The rate (reciprocal of Eq. 1) can be expressed in terms of koff,max and kex as koff = kex c / (1 + kex c / koff,max).

We fit the reciprocal of (1) to the rates of Fig. 3D to obtain the constants A = 118±10 s and B= 1160±80 ng·s/μl (solid curve in Fig. 3D shows this fit). The initial linear rate therefore fits to kex = 1 / B = 8.6 × 10−4 (ng/μl)−1 s−1, and the rate reached at high concentration is koff,max = 1 / A = 8.5 × 10−3 s−1.

Discussion

Fis and NHP6A show DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation

In prior work we have shown that Fis and other proteins display off-rates from DNA that depend on solution concentration of other proteins that are competing to bind the same dsDNA 1. In this paper we have studied similar “facilitated dissociation” effects driven by solution phase DNA segments; the presence of DNA segments accelerates the release of pre-bound Fis from a DNA molecule in the manner of “direct transfer” reactions studied for other proteins exchanging between nucleic acid molecules 10; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27; 28. We have done most of our experiments using the DNA-compacting effect of Fis as a readout of binding (Fig. 1), but we have verified the effect using fluorescence detection of GFP-Fis fusion proteins (Fig. S1).

We have found that Fis dissociation starts out being strongly stimulated by DNA fragments, increasing from a very slow rate at zero DNA concentration (Fig. 2) to a rate of approximately 8×10−3 s−1 as solution concentration of DNA is increased from zero to ≈50 ng/μl. However, for larger DNA concentrations, the release rate remains roughly constant (Fig. 3). This effect is largely independent of DNA length and sequence (Fig. 4), but is controlled by the net mass concentration (base-pair concentration). We have also observed the Fis release rate to be salt-dependent (Fig. 5), the rate increasing as a power law of KGlu concentration (exponent ≈ 2), an effect in accord with the general tendency for increased salt concentration to weaken electrostatic interaction of proteins and nucleic acids 42; 46.

We have also demonstrated similar DNA-segment-facilitated dissociation for the HMG-box yeast transcription factor NHP6A. This result establishes solution-DNA-concentration-off-rate-dependence for a protein known to exhibit protein-facilitated dissociation 1 but which binds through a different type of protein fold (a single HMG box in the case of NHP6A versus a pair of helix-turn-helix domains for Fis), and which binds via only one DNA-binding domain.

We have also discussed a model for this effect with two intermediate states which account for the possibility that the initially bound protein can transiently access a partially bound state, to which a second DNA segment can bind. This type of model has been used before to describe “direct transfer” reactions of proteins between nucleic acid molecules 14; 15; 24. Here we use an analysis that takes advantage of the limit of large excess of competitor DNA to initial protein-DNA complex typical of single-molecule experiments. This first-passage kinetic analysis leads to rather simple analytical formulae for fitting kinetic data. The result produces the initial linear dependence of off-rate on solution concentration, and also the saturation effect at high DNA concentration (Fig. 3).

This model provides an interpretation of the initial linear rate of increase of apparent off-rate with concentration, kex, in terms of the probability of the appearance of a partially unbound state [k01/(k01+k10)] times the rate at which an incoming molecule binds to the complex leading to a complete dissociation (k12 / 2). For dsDNA fragments from 27 bp to ~750 bp in length we find that that the exchange rate is determined by total base-pair concentration (or equivalently, mass concentration), with initial linear behavior koff ≈ kex c, with kex ≈ 9 × 10−4 (ng/μl)−1 s−1. This can be converted to a rate in terms of Fis binding site concentration (21 bp, ≈ 13,000 g/mol), as kex ≈ 1 × 104 M−1 s−1, comparable to the rate seen for Fis/GFP-Fis protein-protein exchange of 6 × 104 M−1 s−1 1. The similarity of these rates for protein- and DNA-facilitated dissociation of Fis from DNA is suggestive of a similar underlying mechanism, i.e., similar probabilities of the partially unbound state which gives a competing molecule access to the initially bound complex.

Given that the diffusion-limited binding reaction rate10 ≈109 M−1 s−1 is an upper limit for k12, the exchange rate constant of kex ≈ 1 × 104 M−1 s−1 suggests that the prefactor k01/(k01+k10) describing the probability of the partially bound precursor state (1) in Fig. 7 is at most ≈10−5. In turn this suggests that the partially bound state (1) is rather rarely occupied, and has a free energy on the order of ln(105) kBT = 11.5 kBT. This value is consistent with the idea that state (1) has had Fis-DNA interactions appreciably disrupted and also validates our assumption that initially the protein may be considered to be in state 0 (i.e., that k01 ≪ k10). We note that evidence exists that Fis is capable of binding duplex DNA at a density of one dimer per 11 bp (rather than the usual 21 bp) 38, providing further justification for consideration of a partially bound transient state in our exchange reactions.

The model also provides a straightforward explanation of the saturation of the rate of release of protein observed experimentally (limiting rate at high concentration in Fig. 3D); if the concentration is sufficiently high, the rate-limiting process for dissociation ceases to be diffusion-limited transport of the competitor to the complex, but is instead controlled by the concentration-independent rates for intermediate state formation (k01) and ternary complex disassembly (k23); the saturation exchange rate is essentially the smaller of these two rates. We observe a saturation of koff at roughly 8×10−3 s−1 for Fis bound to DNA in 100 mM KGlu solution which is therefore either the rate k01 of appearance of state 1 of Fig. 7, or alternately the rate k23 at which the protein dissociates from the ternary complex of state 2. Further experiments may be able to discern which of these two rates is in fact the rate limiting one, i.e., comparable to koff,max.

The appearance of a concentration-dependent off-rate is a consequence of the formation of a ternary complex between three molecules 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 8; 18; 19; 20; 27. We note that strictly speaking, it is not necessary to maintain a truly chemically bonded complex; merely the fact that a dissociated molecule will stay near its original substrate for a short time (a “microdissociation”) should be able to generate the same effect1; 9; 17. Of course this “microdissociation” mechanism still relies on the spatial localization of a molecule near its binding substrate and in some sense is still a “ternary complex” mechanism.

Comparison of results with observations of facilitated dissociation of other DNA-binding proteins

We compare our result for Fis exchange between DNA segments, characterized by kex ≈ 104 M−1 s−1 (per 21 bp Fis binding site, or from our 27 bp measurements), with results from other experiments. As noted above, our own experiments with Fis/GFP-Fis exchange 1, as well as experiments of Gibb et al. 8 on exchange of RPA by Rad51 and RPA on ssDNA segments, found comparable values of kex ≈ 104 M−1 s−1. Higher rates in protein-facilitated dissociation experiments have also been observed; experiments with CueR exchange on dsDNA 4 have found kex ≈ 108 M−1 s−1, while older experiments of Schneider et al 25 on exchange of SSB on ssDNA also observed kex ≈ 107 M−1 s−1. This range of rates suggests a probability of occurrence of a transition state from 10−1 to 10−5 (the factor by which these rates are below the diffusion-limited rate10 of ≈109 M−1 s−1).

In experiments with EcoRI removed from DNA by DNA segments, Sidorova et al.17 observed a much slower kex ≈ 1 × 102 M−1 s−1, with a similar exchange rate being recently observed for ssDNA-ssDNA exchange in a dsDNA oligomer9. These groups attribute the exchange reaction they observed to binding-site-occlusion during complete dissociation of the initially bound pair of molecules. The slower kex is consistent with this conclusion; both of these experiments observe an appreciable change in off-rate only over micromolar changes in the competing species concentration, much higher than the nanomolar concentrations needed for appreciable change in off-rate we have observed for removal of Fis from dsDNA by other protein molecules1 or by short dsDNA segments. It is plausible that the lower the value of kex, the more completely dissociated is the originally bound protein in the transition state for the exchange reaction.

Experiments on E. coli Lac-repressor protein observed roughly similar transfer kinetics to those observed here, with an initial linear dependence on DNA concentration with kex ≈ 30 M−1 bp−1 s−1 (Fig. 5 of Ref. 15), which corresponds to kex ≈ 103 M−1 s−1 per Lac-repressor binding site. Saturation of the transfer reaction off-rate was observed to be koff,max ≈ 10−3 s−1 (Fig. 5 of Ref. 15) in the same range of saturation off-rate as observed for Fis.

We also note experiments on RecA transferred between ssDNA molecules with a bimodal exchange rate characterized by “fast” and “slow” rates of kex ≈ 104 M−1 s−1 and 102 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 2 of Ref. 24). These experiments were carried out at a relatively low salt concentration (10 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2), where electrostatic interactions are enhanced, and where dissociation can be expected to be slow. In accord with this, increasing salt concentration was observed to accelerate the exchange rates (Fig. 4 of Ref. 24). Those experiments also observed saturation of off-rate at high nucleic acid competitor of koff,max ≈ 2×10−2 s−1 (Fig. 8 of Ref. 24), faster but comparable to the 8×10−3 s−1 saturation exchange rate observed in this paper for Fis. In summary, the DNA-facilitated dissociation behavior that we have observed for Fis using our single-molecule assay is quantitatively rather similar to that observed for a range of DNA-binding proteins in bulk assays.

The existence of exchange reactions of the type discussed in this paper have strong implications for quantitative analysis of kinetics of protein-DNA interactions, and for consideration of the dynamics of chromosomally-bound proteins in vivo1. For in vitro characterization of off-rates of a molecule from a substrate, one must consider the role of molecules in solution which may affect off-rates through competition for the binding substrate, and one must be careful about comparing “off-rates” obtained from experiments done at different solution concentrations of competing molecules. Given the high concentrations of macromolecules in vivo, the rates at which chromosomal proteins are removed from DNA are likely strongly affected by competition with macromolecules in the surrounding environment.

Materials and Methods

Protein Preparation

Wild-type Fis protein was over-expressed using the bacteriophage T7 promoter and purified from RJ3387 (BL21 (DE3) fis::kan-767 endA8::tet) using a Bioscale S20 (Bio-Rad) FPLC column followed by chromatography through Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) as described 38; 40. Recombinant NHP6A was purified from Escherichia coli essentially as described 47, except that an additional FPLC mono S chromatography step was included. GFP-Fis protein (a derivative of Fis with a GFP protein fused to its N-terminal end) was prepared as described 1 and used in a small number of experiments.

DNA

Most of the single-DNA magnetic tweezers experiments (vertical experiments, see below) were carried out using end-labeled and linearized 9702 bp plasmid pNG1175 43, which is a slightly modified version of the 9691 bp cloning vector pFOS-1 (New England Biolabs). pNG1175 was purified and then linearized by cutting at unique SpeI and ApaI restriction sites. This linear molecule was ligated to ~900 bp PCR products carrying either biotinylated or digoxigenin-labeled nucleotides, with SpeI and ApaI-compatible ends, respectively. The resulting constructs were 11.4 kb long (referred to in what follows as 10 kb DNA tethers).

Sheared herring sperm DNA (Promega, Madison WI, referred to below as HS-DNA) was used as a solution-phase competitor. Agarose gel electrophoresis showed these fragments to be from 100 to 3000 bp in length with an approximate average size of 750 bp.

Additional experiments were carried out with three 27 bp dsDNA oligomers as solution-phase competitors (IDT, Coralville IA):

F1 (5′-AAATTTGTTTGAATTTTGAGCAAATTT)

F28 (5′-AAATTTGTTTGAGCGTTGAGCAAATTT)

F29 (5′-AAATTTGTTTGGGCGCTGAGCAAATTT)

These molecules have had their Fis-binding affinities and Fis co-crystal structures analyzed in detail 11; 41.

A small number of experiments were carried out with 48.5 kb λ-DNA (Promega, Madison WI), end functionalized with biotinylated and digoxigenin-labeled ssDNAs using a transverse magnetic tweezers system as described 1.

Buffers

Experiments were carried out using 50, 100, 150, 200 or 300 mM potassium glutamate (KGlu), 20 mM HEPES aqueous solution, adjusted to a final pH of 7.5. The 100 mM KGlu buffer is that used in Ref. 1. DNAs were tethered to magnetic particles in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Gibco).

Vertical magnetic tweezers experiments

Vertical magnetic tweezers experiments (the majority of single-DNA experiments of this paper) were performed in flow cells of ≈50 μl volume that were assembled before each experiment. The upper face of the flow cell was a #1 cover glass covalently functionalized with anti-digoxigenin (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis IN) as described23. Before an experiment, a flow cell was filled and incubated with 0.25% w/v bovine casein (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution to passivate the surfaces. Linearized and end-labeled pNG1175 DNA was incubated with 2.7 μm diameter streptavidin-functionalized paramagnetic beads (M-270 Dynabeads, Invitrogen, Grand Island NY) in PBS, allowing the biotinylated ends of the DNA to bind the beads. Then, the beads were introduced into the flow cell, allowing their digoxigenin-functionalized ends to bind the anti-dig-functionalized flow cell surface.

The flow cell was then placed on a magnetic tweezers setup, consisting of a 100X 1.35 NA (Olympus) microscope objective on a piezoelectric positioner (Piezojena), near permanent magnets that are positioned using a stepper-motor-driven translator23. The force applied to the paramagnetic beads was adjusted by moving the magnets to different positions from the flow cell. A fraction of the paramagnetic particles adsorb permanently to the cover slip, providing a reference point for determination of the position of the glass surface. Vertical positions of beads were measured using a focusing algorithm, and also by a separate algorithm that uses the degree of focus of the beads to determine their distance from the glass, both implemented by Labview (National Instruments, Austin TX) programs. Forces were calibrated using a fluctuation method as described23. The known force-extension relation for single DNAs 48 was used to verify that a given bead was attached by a single molecule. It was checked that the DNA molecules under study were non-supercoilable (or “nicked”), by determining that magnet rotations did not change the extension of the DNA.

Once it was determined that the tether was a single DNA, a typical experiment started with force set to 1 pN, followed by exchange of the tethering buffer (PBS) with the experiment buffer (KGlu-HEPES buffer containing no protein or DNA segments; volume of buffer exchanged ~400 μl). The initial length of the tethered DNA at various forces was measured in buffer. Then, protein in KGlu buffer was introduced into the flow cell, and the length of the tethered DNA was measured again. In a number of “static” experiments, a series of force-extension measurements were made in protein-KGlu solution to measure the elasticity of DNA in equilibrium with solution at a given concentration.

In “kinetic” experiments, the protein solution was next replaced with protein-free KGlu buffer and the length of the tethered DNA was again measured. Then, a given concentration of linear DNA segments in KGlu buffer were introduced into the flow cell, and the force was reduced to 0.3 pN to provide maximum accuracy for detection of extension change as protein dissociated. Length measurements during the dissociation period were carried out at a rate of approximately 40 s−1. Magnetic tweezers raw data were analyzed off-line using Origin 7 (Originlab, Northampton MA).

Transverse Magnetic Tweezers Experiments

A small number of experiments were carried out using a transverse magnetic tweezers system as described1, and 48.5 kb λ-DNA end-functionalized with biotin and digoxigenin. In short, λ-DNA molecules were tethered to the inside of a glass capillary, the interior of which was coated with anti-digoxigenin (Roche). The interior of the capillary was then imaged using an inverted contact objective (100X, 1.4 NA, Nikon) using either bright-field or fluorescence imaging. Streptavidin-coated magnetic particles (2.8 μm Dynabead, Invitrogen) were attached to the other end of the DNA molecules to allow them to be manipulated using permanent magnets on a translator to the side of the capillary.

Experiments were carried out by first incubating the anti-digoxigenin-coated capillary with DNA in 20 mM HEPES buffer (100 mM KGlu) to allow them to bind to the interior glass surface then introducing the magnetic particles and incubating to allow the DNA to bind the particles. Once an appropriate tether was identified, a solution of 200 nM GFP-Fis protein was introduced and allowed to incubate for ~5 min. The protein solution was then washed out with experiment buffer and fluorescence imaging was carried out to visualize the GFP-Fis bound to the DNA. Finally, DNA fragments were added and a series of images were acquired to follow the removal of the GFP-Fis from the λ-DNA, in a manner similar to that used in 1. Data were analyzed using Igor Pro 6 (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR) software1.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

protein off-rates from DNA are often modeled as concentration-independent

single-molecule data show dependence of unbinding on DNA concentration

multi-state dissociation pathway can explain the experimental data

Acknowledgments

Work at NU was supported by NSF grants DMR-1206868 and MCB-0240998, by NIH grants GM105847 and CA193419 (JFM), and by NSF grant DMR-1309027 and by an International Institute for Nanotechnology Postdoctoral Fellowship (CES). Work at UCLA was supported by NIH grant GM038509 (RCJ). Work at Yale was supported by NIH grant GM097348 (PI: Enrique M. De La Cruz).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Graham JS, Johnson RC, Marko JF. Concentration-dependent exchange accelerates turnover of proteins bound to double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2249–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sing CE, Olvera de la Cruz M, Marko JF. Multiple-binding-site mechanism explains concentration-dependent unbinding rates of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:3783–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocco S, Marko JF, Monasson R. Stochastic ratchet mechanisms for replacement of proteins bound to DNA. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;112:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.238101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi CP, Panda D, Martell DJ, Andoy NM, Chen TY, Gaballa A, Helmann JD, Chen P. Direct substitution and assisted dissociation pathways for turning off transcription by a MerR-family metalloregulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208508109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loparo JJ, Kulczyk AW, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. Simultaneous single-molecule measurements of phage T7 replisome composition and function reveal the mechanism of polymerase exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3584–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018824108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunzelmann S, Morris C, Chavda AP, Eccleston JF, Webb MR. Mechanism of interaction between single-stranded DNA binding protein and DNA. Biochemistry. 2010;49:843–52. doi: 10.1021/bi901743k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo Y, North JA, Rose SD, Poirier MG. Nucleosomes accelerate transcription factor dissociation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:3017–27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibb B, Ye LF, Gergoudis SC, Kwon Y, Niu H, Sung P, Greene EC. Concentration-dependent exchange of replication protein A on single-stranded DNA revealed by single-molecule imaging. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paramanthan T, Reeves D, Friedman LJ, Kondev J, Gelles J. A general mechanism for competitor-induced dissociation of molecular complexes. Nat Comm. 2015;5:5207. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halford SE, Marko JF. How do site-specific DNA-binding proteins find their targets? Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3040–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stella S, Cascio D, Johnson RC. The shape of the DNA minor groove directs binding by the DNA-bending protein Fis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:814–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1900610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Hippel PH, Berg OG. Facilitated target location in biological systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:675–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bresloff JL, Crothers DM. DNA-ethidium reaction kinetics: demonstration of direct ligand transfer between DNA binding sites. J Mol Biol. 1975;95:103–23. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan DP, Crothers DM. Relaxation kinetics of DNA-ligand binding including direct transfer. Biopolymers. 1984;23:537–62. doi: 10.1002/bip.360230309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried MG, Crothers DM. Kinetics and mechanism in the reaction of gene regulatory proteins with DNA. J Mol Biol. 1984;172:263–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruusala T, Crothers DM. Sliding and intermolecular transfer of the lac repressor: kinetic perturbation of a reaction intermediate by a distant DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4903–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidorova NY, Scott T, Rau DC. DNA concentration-dependent dissociation of EcoRI: direct transfer or reaction during hopping. Biophys J. 2013;104:1296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esadze A, Iwahara J. Stopped-flow fluorescence kinetic study of protein sliding and intersegment transfer in the target DNA search process. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:230–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doucleff M, Clore GM. Global jumping and domain-specific intersegment transfer between DNA cognate sites of the multidomain transcription factor Oct-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman BA, Nordeen SK. DNA intersegment transfer, how steroid receptors search for a target site. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1061–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman J, Maher LJ., 3rd Transient HMGB protein interactions with B-DNA duplexes and complexes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aragay AM, Diaz P, Daban JR. Association of nucleosome core particle DNA with different histone oligomers. Transfer of histones between DNA-(H2A,H2B) and DNA-(H3,H4) complexes. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:141–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoko D, Wong B, Johnson RC, Marko JF. Micromechanical analysis of the binding of DNA-bending proteins HMGB1, NHP6A, and HU reveals their ability to form highly stable DNA-protein complexes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13867–74. doi: 10.1021/bi048428o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menetski JP, Kowalczykowski SC. Transfer of recA protein from one polynucleotide to another. Kinetic evidence for a ternary intermediate during the transfer reaction. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2085–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider RJ, Wetmur JG. Kinetics of transfer of Escherichia coli single strand deoxyribonucleic acid binding protein between single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid molecules. Biochemistry. 1982;21:608–15. doi: 10.1021/bi00533a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlov AG, Lohman TM. Kinetic mechanism of direct transfer of Escherichia coli SSB tetramers between single-stranded DNA molecules. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11611–27. doi: 10.1021/bi020361m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KS, Marciel AB, Kozlov AG, Schroeder CM, Lohman TM, Ha T. Ultrafast redistribution of E. coli SSB along long single-stranded DNA via intersegment transfer. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2413–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorch Y, Zhang M, Kornberg RD. Histone octamer transfer by a chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1999;96:389–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan J, Marko JF. Effects of DNA-distorting proteins on DNA elastic response (vol E 68, art no 011905, 2003) Physical Review E. 2003;68 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCauley M, Hardwidge PR, Maher LJ, 3rd, Williams MC. Dual binding modes for an HMG domain from human HMGB2 on DNA. Biophys J. 2005;89:353–64. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCauley MJ, Zimmerman J, Maher LJ, 3rd, Williams MC. HMGB binding to DNA: single and double box motifs. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:993–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao B, Johnson RC, Marko JF. Modulation of HU-DNA interactions by salt concentration and applied force. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6176–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCauley MJ, Rueter EM, Rouzina I, Maher LJ, 3rd, Williams MC. Single-molecule kinetics reveal microscopic mechanism by which High-Mobility Group B proteins alter DNA flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:167–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan J, Marko JF. Effects of DNA-distorting proteins on DNA elastic response. Physical Review E. 2003;68 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang HY, Marko JF. Range of Interaction between DNA-Bending Proteins is Controlled by the Second-Longest Correlation Length for Bending Fluctuations. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.248301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao BT, Zhang HY, Johnson RC, Marko JF. Force-driven unbinding of proteins HU and Fis from DNA quantified using a thermodynamic Maxwell relation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5568–5577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang HY, Marko JF. Intrinsic and force-generated cooperativity in a theory of DNA-bending proteins. Physical Review E. 2010;82 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.051906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skoko D, Yoo D, Bai H, Schnurr B, Yan J, McLeod SM, Marko JF, Johnson RC. Mechanism of chromosome compaction and looping by the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein Fis. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:777–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Noort J, Verbrugge S, Goosen N, Dekker C, Dame RT. Dual architectural roles of HU: formation of flexible hinges and rigid filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6969–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308230101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan CQ, Finkel SE, Cramton SE, Feng JA, Sigman DS, Johnson RC. Variable structures of Fis-DNA complexes determined by flanking DNA-protein contacts. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:675–95. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hancock SP, Ghane T, Cascio D, Rohs R, Di Felice R, Johnson RC. Control of DNA minor groove width and Fis protein binding by the purine 2-amino group. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:6750–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mascotti DP, Lohman TM. Thermodynamic extent of counterion release upon binding oligolysines to single-stranded nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3142–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bai H, Sun M, Ghosh P, Hatfull GF, Grindley ND, Marko JF. Single-molecule analysis reveals the molecular bearing mechanism of DNA strand exchange by a serine recombinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018436108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernasconi CF. Relaxation Kinetics. Academic Press; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ninio J. Alternative to the steady-state method: derivation of reaction rates from first-passage times and pathway probabilities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:663–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lohman TM, Mascotti DP. Thermodynamics of ligand-nucleic acid interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1992;212:400–24. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)12026-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yen YM, Wong B, Johnson RC. Determinants of DNA binding and bending by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae high mobility group protein NHP6A that are important for its biological activities. Role of the unique N terminus and putative intercalating methionine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4424–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marko JF, Siggia ED. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules. 1995;28:8759–8770. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.