Abstract

The target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) pathway couples nutrient, energy and hormonal signals with eukaryotic cell growth and division. In yeast, TORC1 coordinates growth with G1–S cell cycle progression, also coined as START, by favouring the expression of G1 cyclins that activate cyclin-dependent protein kinases (CDKs) and by destabilizing the CDK inhibitor Sic1. Following TORC1 downregulation by rapamycin treatment or nutrient limitation, clearance of G1 cyclins and C-terminal phosphorylation of Sic1 by unknown protein kinases are both required for Sic1 to escape ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis prompted by its flagging via the SCFCdc4 (Skp1/Cul1/F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complex. Here we show that the stabilizing phosphorylation event within the C-terminus of Sic1 requires stimulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase, Mpk1, and inhibition of the Cdc55 protein phosphatase 2A (PP2ACdc55) by greatwall kinase-activated endosulfines. Thus, Mpk1 and the greatwall kinase pathway serve TORC1 to coordinate the phosphorylation status of Sic1 and consequently START with nutrient availability.

The target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) pathway couples nutrient availability with cell growth and division by destabilizing the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor Sic1. Here the authors show that TORC1 downregulation leads to stabilization of Sic1 via phosphorylation by the MAP kinase Mpk1 and inhibition of dephosphorylation via the greatwall kinase pathway.

The target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) pathway couples nutrient availability with cell growth and division by destabilizing the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor Sic1. Here the authors show that TORC1 downregulation leads to stabilization of Sic1 via phosphorylation by the MAP kinase Mpk1 and inhibition of dephosphorylation via the greatwall kinase pathway.

Nutrient signalling drives protein kinase activity of target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) to stimulate anabolic, growth-related processes (for example, protein biosynthesis) in concert with cell cycle transition events1,2. TORC1 has primarily been appreciated for its role in coordinating growth with the G1–S cell cycle transition, or START in yeast3, but recent data indicate that TORC1 also contributes to the fine-tuning of other cell cycle events (for example, G2–M transition) to environmental cues4,5. TORC1 favours the G1–S transition in part by promoting transcription and translation of the cell cycle regulatory G1 cyclins4,6,7,8. However, detailed mechanistic insight into TORC1-regulated G1 cyclin expression is still sporadic and incomplete. A well-studied example in yeast indicates that the Cln3 G1 cyclin levels, and consequently START-promoting G1 cyclin-dependent protein kinase (CDK; Cln-Cdc28) activity, are specifically sustained by TORC1-mediated stimulation of translation initiation. The latter is required for ribosomes to bypass a translational repressive upstream open reading frame and reach the start codon of the 5′-untranslated region within the CLN3 messenger RNA (mRNA)7,9. In parallel to favouring G1 cyclin expression, TORC1 further couples cell growth with cell cycle progression by antagonizing the expression and/or function of CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) that restrain CDK-mediated G1–S transition4. Although the underlying mechanistic details remain poorly understood, progress has also been made in this area. An example in yeast, again, is the CDKI Sic1, which binds, following G1 CDK-dependent multi-site phosphorylation, the F-box protein Cdc4 of the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase complex that flags it for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis10,11,12,13. TORC1 apparently triggers Sic1 degradation not only by ensuring G1 CDK activation but also by confining the phosphorylation of specific residue(s) (for example, Thr173) in Sic1 (ref. 6). The details of the latter regulatory mechanism, however, are still elusive.

Attenuation of signalling through TORC1 (for example, following carbon and/or nitrogen limitation) incites yeast cells to arrest in G1 of the cell cycle and enter a quiescent state that is characterized by a distinct array of physiological, biochemical and morphological traits14,15. The protein kinase Rim15 orchestrates quiescence (including proper G1 arrest) when released from inhibition by the AGC family kinase, Sch9, which requires, analogously to mammalian S6 kinase (S6K), activation by TORC1 (refs 16, 17, 18, 19). Like the orthologous greatwall kinases (Gwl) in higher eukaryotes, Rim15 controls some of its distal readouts by phosphorylating a conserved residue within endosulfines (that is, Igo1/2 in yeast), thereby converting them to inhibitors of the Cdc55 protein phosphatase 2A (PP2ACdc55; or PP2A-B55 in higher eukaryotes)20,21,22. The Gwl signalling branch in yeast (Rim15-Igo1/2-PP2ACdc55) mediates the activation of a quiescence-specific gene expression programme in part via the transcriptional activator Gis1 and likely additional factors that protect specific mRNAs from degradation via the 5′–3′ mRNA decay pathway22,23,24,25. Whether Rim15 also controls cell cycle arrest in G1 via Igo1/2-PP2ACdc55 is currently not known. Interestingly, in this context, Xenopus, Drosophila and likely human cells employ their respective greatwall kinase pathway (Gwl-endosulfine-B55) to maintain high-level phosphorylation of cyclin B-CDK1 substrates, thereby promoting mitotic entry26,27. In yeast, however, the Gwl signalling branch contributes only marginally to the regulation of mitotic entry28,29, likely because TORC1 curtails signalling through Rim15 in exponentially growing cells.

Here we show that TORC1 inhibition and consequently activation of Igo1/2 by the Gwl Rim15 serves to antagonize PP2ACdc55 and prevent it from dephosphorylating pThr173 within the CDKI Sic1. This specific phosphorylation event depends on the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Mpk1 and ensures protection of Sic1 from SCFCdc4-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis to enable it to grant proper G1 arrest when TORC1 is downregulated. Thus, TORC1 coordinates the phosphorylation status of Sic1 and consequently G1–S cell cycle progression with nutrient availability via Mpk1 and the greatwall kinase pathway.

Results

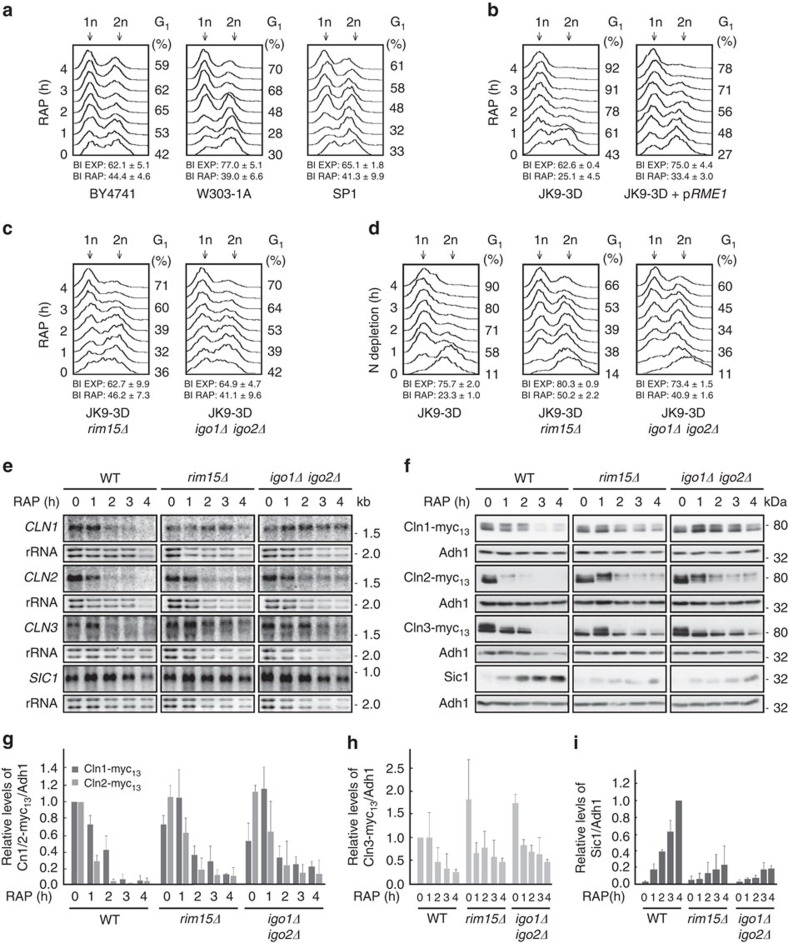

The greatwall kinase pathway controls Sic1 stability

To study whether Rim15 mediates G1 cell cycle arrest via activation of endosulfines and consequently inhibition of PP2ACdc55, we treated wild-type (WT) BY4741 cells with rapamycin and examined the cells by standard fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses. Unexpectedly, we found that BY4741 WT cells, like the ones from other commonly used WT strains such as W303-1A and SP1 (ref. 30), exhibited a significant delay in rapamycin-induced G1 arrest that contrasted with the quite rapid G1 arrest observed in JK9-3D WT cells (Fig. 1a,b). In trying to understand the different behaviour of JK9-3D cells, which have been instrumental for the discovery of TORC1 (ref. 31), we noticed that they carry a genomic rme1 mutation that (on the basis of our complementation analysis) is in part responsible for their expedited rapamycin-induced G1 arrest (Fig. 1b). Of note, Rme1 contributes to G1 cyclin gene expression and has been assigned a specific role in preventing premature entry of cells into an off-cycle stationary phase (at G1) in response to nutrient limitation32. While this issue deserves to be addressed in more detail elsewhere, we decided to take advantage of the robust rapamycin-induced G1 arrest in JK9-3D cells to address our question whether Rim15 mediates G1 cell cycle arrest via activation of endosulfines. Accordingly, we found that a large fraction of rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells was significantly impaired in proper G1 arrest following rapamycin treatment when compared with their isogenic JK9-3D WT cells (Fig. 1c). This defect of rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells was even more pronounced following nitrogen starvation, a physiological condition that results in rapid TORC1 downregulation and subsequent G1 arrest in WT cells (Fig. 1d)33.

Figure 1. The greatwall kinase pathway ensures proper G1 arrest following TORC1 inactivation.

(a) Cells of commonly used Saccharomyces cerevisiae wild-type strains (that is, BY4741, W303-1A and SP1) exhibit a delay in G1 arrest following rapamycin-mediated TORC1 inactivation. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses of the DNA content of wild-type cells treated for the indicated times with rapamycin are shown. The relative number of budded cells (budding index, BI) was determined in exponentially growing (EXP) and rapamycin-treated (RAP; 4 h) cultures. Numbers are means±s.d. from three independent experiments in which at least 300 cells were assessed. Populations of cells contain both 1n (G1; left-hand peak) and 2n (G2/M; right-hand peak) DNA. The relative level of 1n cells within the populations is indicated on the right of the graphs (G1 (%)). (b) JK9-3D cells promptly and uniformly arrest in G1 following rapamycin treatment. Expression of plasmid-encoded RME1 from its own promoter (pRME1) delays the rapamycin-mediated G1 arrest in JK9-3D cells, indicating that the rme1 mutation in JK9-3D contributes significantly to the observed phenotype. (c,d) Swift G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated (c) or nitrogen-starved (d) JK9-3D cells requires Rim15 and Igo1/2. (e) Northern blot analyses of the expression of the indicated cell cycle regulatory genes in exponentially growing (0 h) and rapamycin-treated (1–4 h) wild-type (WT; JK9-3D), rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ mutant cells. Ribosomal RNA served as loading control. (f–i) The levels of genomically myc13-tagged cyclins (f–h), or of endogenous Sic1 (f,i), in exponentially growing (0 h) and rapamycin-treated (1–4 h) WT (JK9-3D), rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ mutant cells, were determined by immunoblot analyses using monoclonal anti-myc or polyclonal anti-Sic1 antibodies, respectively. Adh1 levels served as loading controls. The experiments were performed independently three times (one representative blot is shown in f). The myc13-tagged cyclin (g,h) or Sic1 (i) levels were normalized to the Adh1 levels in each case, calculated relative to the value in exponentially growing WT cells (set to 1.0 (g,h)) or to the value in 4-h rapamycin-treated WT cells (set to 1.0 (i)), respectively, and expressed as mean values (n=3;±s.d.).

Since our results suggested a role for Rim15/Igo1/2 in cell cycle control, we next examined whether the expression of G1 cyclins (Cln1, Cln2 and Cln3) or of the CDKI Sic1 was altered in rapamycin-treated rim15Δ or igo1/2Δ mutant cells. In agreement with previous reports6,7, the CLN1–3 transcripts and their corresponding proteins were progressively depleted in rapamycin-treated WT cells (Fig. 1e,f). In parallel, and consistent with the notion that TORC1 inhibition entails post-translational Sic1 stabilization6, Sic1 protein levels strongly increased despite the fact that the respective SIC1 transcript levels remained relatively constant over the entire period of the rapamycin treatment. In rapamycin-treated rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ mutant cells, clearance of CLN1–3 transcripts and of Cln1–3 proteins was noticeably delayed when compared with WT cells (Fig. 1e–h). In addition, loss of Rim15 or of Igo1/2, while only marginally affecting SIC1 mRNA levels (Fig. 1e), severely and persistently compromised the ability of rapamycin-treated cells to accumulate Sic1 (Fig. 1f,i). This latter defect, which was also observed in respective BY4741, W303-1A and SP1 rim15Δ mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1), may in part be due to the delayed elimination of G1 cyclins that favour CDK-mediated multi-site phosphorylation and consequently SCFCdc4-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of Sic1. However, both the transient nature of the G1 cyclin downregulation defect and the rather persistent Sic1 accumulation defect in rapamycin-treated rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells indicate that the Rim15-Igo1/2 signalling branch controls Sic1 stability also via an additional mechanism(s) that is not directly related to G1 cyclin expression control.

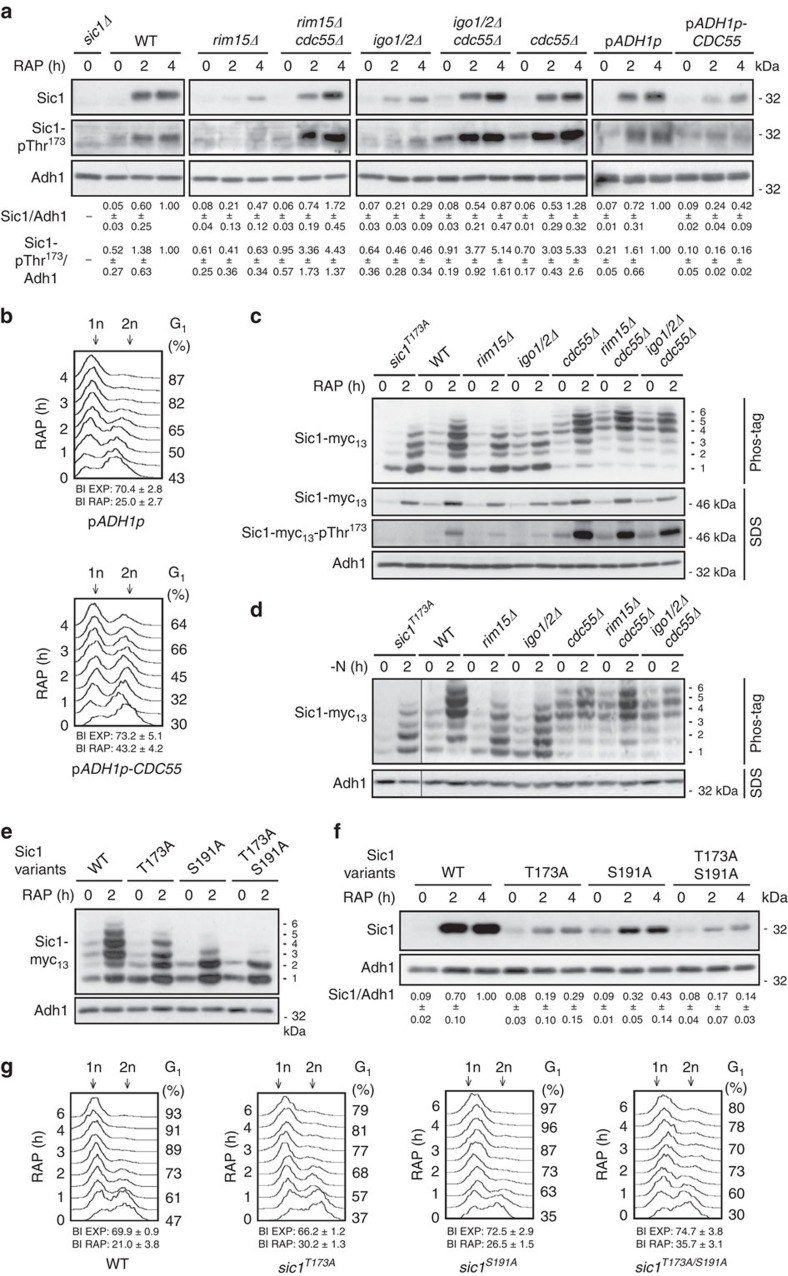

Following their activation by Rim15, Igo1/2 mediate some, if not all, of their effects via the inhibition of PP2ACdc55. Supporting this notion, we also found that loss of the regulatory Cdc55 subunit of the heterotrimeric PP2ACdc55 complex rescued the Sic1 stabilization defect in rapamycin-treated rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells (Fig. 2a). Loss of Cdc55 alone, however, was not sufficient to drive Sic1 accumulation in exponentially growing cells, indicating that TORC1 antagonizes Sic1 by additional Cdc55-independent means. We were not able to examine whether loss of Cdc55 also suppresses the G1 arrest defect in rapamycin-treated rim15Δ or igo1/2Δ cells because all of the respective cdc55Δ mutants exhibited an extended G2/M delay that reflects an additional crucial role of PP2ACdc55 in mitotic entry and spindle assembly checkpoint control34. Expectedly, however, overexpression of Cdc55 under the control of the constitutive ADH1 promoter destabilized Sic1 (Fig. 2a) and caused a G1 arrest defect in rapamycin-treated cells (Fig. 2b) to a similar extent as loss of Rim15 or of Igo1/2 (Fig. 1c). Together with the current literature, these data could be unified in a model in which PP2ACdc55 and Cln-CDK antagonize G1 arrest by favouring Sic1 destabilization via dephosphorylation and phosphorylation, respectively, of different, specific residues within Sic1.

Figure 2. The greatwall kinase pathway regulates phosphorylation and stability of Sic1.

(a) Loss of Cdc55 suppresses the defect of rapamycin-treated rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells in Sic1 accumulation. Sic1 levels and phosphorylation of Thr173 in Sic1 (Sic1-pThr173) were determined by immunoblot analyses using polyclonal anti-Sic1 and phospho-specific anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies, respectively. Overexpression of plasmid-encoded CDC55 from the strong constitutive ADH1 promoter (ADH1p) prevents normal Sic1 accumulation and reduces the total amount of Sic1-pThr173 in WT cells. Relevant genotypes are indicated. The experiments were performed independently three times (one representative blot is shown). The respective Sic1 levels or Sic1-pThr173 signals were normalized to the Adh1 levels in each case, calculated relative to the value in 4-h rapamycin-treated wild-type cells (set to 1.0), except for the values of the CDC55-overexpressing cells (pADH1p-CDC55), which were calculated relative to the control cells carrying the empty vector (pADH1p), and expressed as mean values (n=3;±s.d.). (b) Overexpression of plasmid-encoded CDC55 from the ADH1 promoter causes a substantial defect in G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated WT cells. (c–e) Phos-tag phosphate affinity gel electrophoresis analyses of genomically myc13-tagged Sic1, Sic1T173A, Sic1S191A and/or Sic1T173A/S191A in extracts from exponentially growing (time 0 h) and rapamycin-treated (RAP; 2 h; (c,e)) or nitrogen-deprived (−N; 2 h; (d)) strains with the indicated genotype. The six differentially phosphorylated Sic1-myc13 isoforms are numbered sequentially from 1 to 6 (right side of the panels). In c, samples were also subjected to SDS–gel electrophoresis to detect the Sic1-myc13 levels and Sic1-myc13-pThr173 signals by immunoblot analyses using monoclonal anti-myc and phospho-specific anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies, respectively. (f,g) The Sic1T173A allele is unstable (f) and compromises timely G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated cells (g). Levels of Sic1 in f were determined in exponentially growing (time 0 h) and rapamycin-treated (2 and 4 h) WT, sic1T173A, sic1S191A and sic1T173A/S191A cells and quantified as in a. For quantifications of FACS profiles, see Supplementary Fig. 4. FACS and BI analyses in b and g were performed as in Fig. 1a. Adh1 levels in a,c,d,e and f served as loading controls. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

The greatwall kinase pathway impinges on Thr173 in Sic1

To begin to study how many residues in Sic1, if any, are targeted by PP2ACdc55, we examined the migration pattern of Sic1-myc13 by phosphate affinity gel electrophoresis in different yeast strains. When analysed in extracts of exponentially growing WT, rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells, the weakly expressed Sic1-myc13 migrated in at least four distinct bands (labelled isoforms 1–4; Fig. 2c,d). Following rapamycin treatment (Fig. 2c), and similarly following nitrogen starvation (Fig. 2d), two additional slow-migrating Sic1-myc13 isoforms (labelled 5 and 6) were detectable in WT cell extracts. These were either absent (isoform 6) or reduced in intensity (isoform 5) in rapamycin-treated and in nitrogen-starved rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ cells, which likely explains the relative increase in the intensity of the faster migrating isoforms in the extracts of the respective strains (Fig. 2c,d). Loss of Cdc55, however, rendered rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ mutant cells capable again of expressing both isoforms (that is, isoforms 5 and 6) at levels comparably (or even higher) to the ones in WT cells under the same conditions. Of note, in exponentially growing, rapamycin-treated and nitrogen-starved cells, and independently of the presence or absence of Rim15 or Igo1/2, Sic1-myc13 preferentially migrated as isoforms 4, 5 and 6 when Cdc55 was absent. Together, these results indicate that PP2ACdc55 targets at least two Sic1 phosphoresidues (to various degrees), and that activation of Rim15/Igo1/2 following rapamycin treatment or nitrogen starvation restrains the respective PP2ACdc55 activity. To examine whether one of the respective residues corresponded to phosphorylated Thr173 (pThr173), which is critical for Sic1 stability in rapamycin-treated cells6 (Supplementary Fig. 2), we also analysed the migration pattern of a Sic1T173A mutant allele via phosphate affinity gel electrophoresis in extracts of rapamycin-treated or nitrogen-starved cells. The Sic1T173A-myc13 migration pattern specifically lacked isoform 6 and was overall very similar to the one observed for Sic1-myc13 in extracts of rapamycin-treated or nitrogen-starved rim15Δ and igo1/2Δ mutant cells (Fig. 2c,d; Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that pThr173 in Sic1 may indeed represent a PP2ACdc55 target. Moreover, the previously identified phosphoresidue pSer191 in Sic1 (ref. 35) was required for the formation of three of the observed 6 isoforms (as Sic1S191A-myc13 migrated only in three (two major and one weaker) bands in rapamycin-treated cells; isoforms 1–3; Fig. 2e). Interestingly, mutation of Thr173 to Ala in Sic1 destabilized Sic1 and compromised proper G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated cells, and both of these defects were marginally enhanced by combined mutation of Thr173 and Ser191 to Ala in Sic1 (Fig. 2f,g; see budding indices; Supplementary Fig. 4). The Sic1S191A allele per se, albeit less stable than WT Sic1, was able to ensure normal rapamycin-induced G1 arrest in vivo (Fig. 2f,g; Supplementary Fig. 4). The stability of Sic1 and hence proper G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated cells therefore primarily depend on the phosphorylation of Thr173 with at most accessory contributions from pSer191 (as well as potentially additional, less significant phosphoresidues). To further verify this assumption, we decided to focus our subsequent analyses on Thr173 in Sic1. Using phospho-specific antibodies against pThr173 in Sic1 (see below), we found that the Sic1-pThr173 signal strongly increased in rapamycin-treated WT cells, but not in Cdc55 overproducing nor in rim15Δ, or igo1/2Δ cells, unless the latter two mutant strains were additionally deleted for CDC55 (Fig. 2a). In control experiments (corroborating the in vivo specificity of the anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies), mutation of Thr173 to Ala in Sic1 totally abolished the Sic1-pThr173 signal, and eliminated the Sic1-myc13 isoform 6 on phos-tag gels, even when Cdc55 was absent (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation signals closely mirrored the overall Sic1 levels in rapamycin-treated WT and all, except the sic1T173A, mutant strains tested (Fig. 2a). Together, these data corroborate a model in which activation of Rim15/Igo1/2 following TORC1 inhibition serves to antagonize PP2ACdc55 and prevent it from dephosphorylating pThr173 (and possibly additional phosphoresidues) in Sic1, which presumably exposes Sic1 to a proteolytic degradation mechanism.

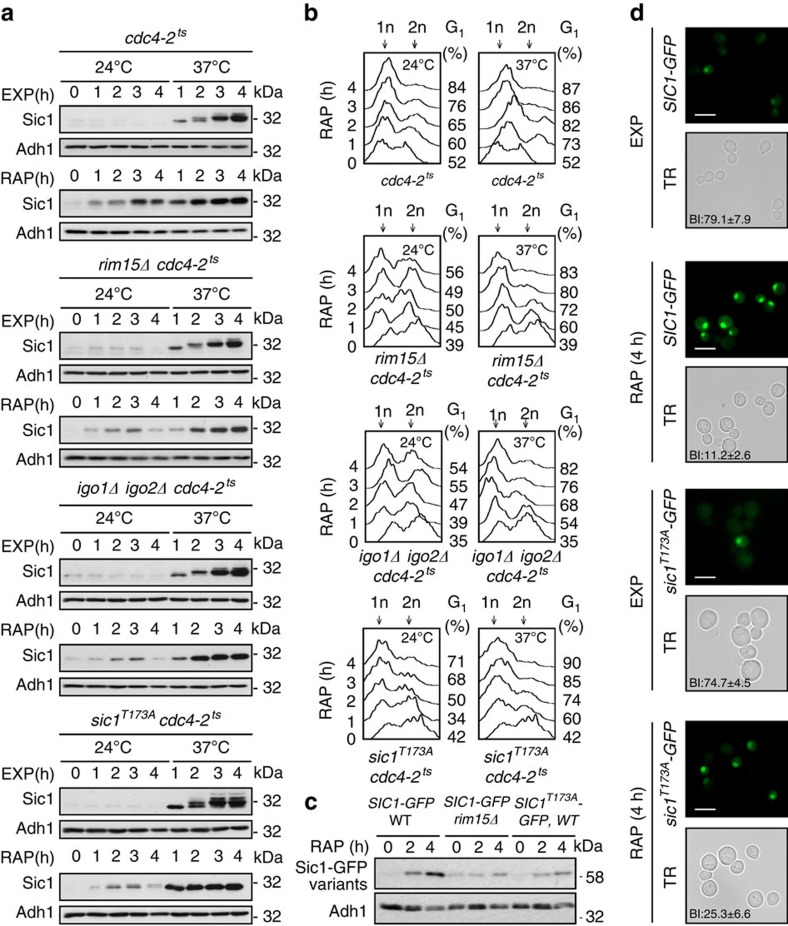

Inactivation of SCFCdc4 stabilizes Sic1T173A

To examine whether phosphorylation of Thr173 in Sic1 may serve to protect Sic1 from SCFCdc4-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis, we introduced the temperature-sensitive cdc4-2ts allele in our WT, rim15Δ, igo1/2Δ and sic1T173A strains, and measured their capacity to accumulate Sic1 during exponential growth or following rapamycin treatment at the permissive (24 °C) and the non-permissive temperature (37 °C). At 24 °C, the cdc4-2ts allele did not noticeably alter the Sic1 expression pattern in any of the strains studied, whether they were grown exponentially or subjected to rapamycin treatment (that is, specifically rim15Δ cdc4-2ts, igo1/2Δ cdc4-2ts and sic1T173A cdc4-2ts cells were still defective for normal Sic1 accumulation following rapamycin treatment when compared with cdc4-2ts cells; Fig. 3a). Temperature inactivation of Cdc4-2ts (at 37 °C), however, prompted Sic1 accumulation to a similarly strong extent in all strains, independently of the presence or absence of rapamycin, and could thus override the defect in Sic1 accumulation, but not in Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b), in rapamycin-treated rim15Δ cdc4-2ts, igo1/2Δ cdc4-2ts, and sic1T173A cdc4-2ts cells. As expected, the latter mutant strains also regained their capacity to timely arrest in G1 following rapamycin treatment at 37 °C, but not at 24 °C (Fig. 3b). Rim15-Igo1/2-mediated inhibition of PP2ACdc55 therefore likely serves to preserve the phosphorylation status of Thr173 (and other residues) in Sic1, thereby preventing SCFCdc4-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis of Sic1. To address the possibility that Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation plays an additional role in nutrient-regulated nucleo-cytoplasmic distribution of Sic1 (ref. 36), we examined the localization of endogenously tagged Sic1–green fluorescent protein (GFP) and of Sic1T173A–GFP. These GFP fusions behaved like the respective untagged versions in terms of their stability (that is, Sic1–GFP accumulated in rapamycin-treated WT, but not in rim15Δ cells, and Sic1T173A–GFP was intrinsically unstable in a WT context under the same conditions; Fig. 3c). Sic1T173A–GFP, although expressed at lower levels and compromised in ensuring proper G1 arrest to a larger fraction of the population, was able to accumulate like Sic1–GFP within the nuclei of those cells that were still able to arrest in an unbudded state, specifically also following rapamycin treatment (Fig. 3d). Thus, Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation likely serves to primarily control Sic1 stability, but not Sic1 subcellular localization.

Figure 3. Inactivation of SCFCdc4 stabilizes Sic1T173A.

(a) Levels of endogenous Sic1 were determined by immunoblot analyses as in Fig. 2a. Cells (genotypes indicated) were pre-grown exponentially at 24 °C (time 0 h) and then grown up to 4 h at either 24 °C or 37 °C (to inactivate Cdc4-2ts) in the absence (EXP) or presence of rapamycin (RAP). Samples were taken at the indicated time points. (b) FACS analyses from cells treated as in a. (c,d) Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation primarily serves to control Sic1 stability, but not Sic1 subcellular localization. In c, levels of endogenously tagged Sic1–GFP and Sic1T173A–GFP were determined in exponentially growing (time 0 h) and rapamycin-treated (2 h and 4 h) WT and/or rim15Δ cells by immunoblot analyses using polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies. In d, exponentially growing (EXP) or rapamycin-treated (RAP; 4 h) cells expressing endogenously tagged versions of Sic1–GFP or Sic1T173A–GFP were analysed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars, 5 μm (white); TR, transmission; BI, budding index. Adh1 levels in a and c served as loading controls. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

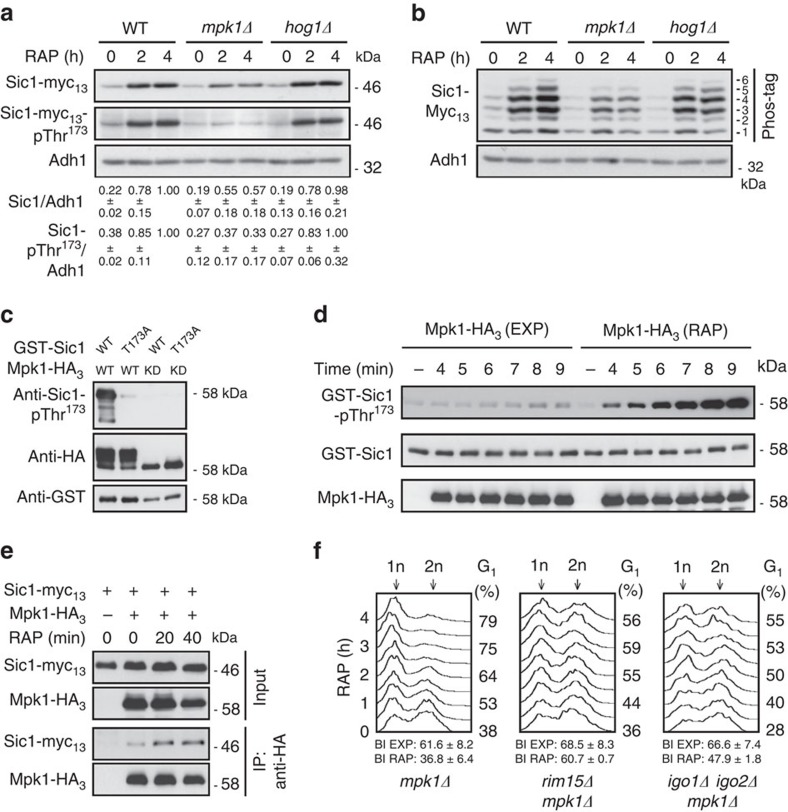

Mpk1 phosphorylates Thr173 in Sic1

Since rapamycin treatment was able to strongly increase the Sic1-pThr173 signal in cdc55Δ cells (Fig. 2a), we reasoned that TORC1 is additionally involved in downregulation of a Sic1-Thr173-targeting protein kinase(s). In this context, the MAPK Hog1 has previously been proposed to mediate Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation following exposure of cells to osmotic stress37. Whether TORC1 impinges on Hog1 is not known, but TORC1 indirectly inhibits the closely related MAPK Slt2/Mpk1 (refs 38, 39). Intriguingly, and consistent with a role of Mpk1 in Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation, loss of Mpk1, but not of Hog1, significantly reduced the Sic1-pThr173 signal and rendered Sic1 unstable in rapamycin-treated cells (Fig. 4a). Moreover, the migration pattern of Sic1-myc13 (analysed by phosphate affinity gel electrophoresis) in extracts of rapamycin-treated WT, mpk1Δ and hog1Δ cells indicated that Mpk1, but not Hog1, might (directly or indirectly) target one major residue in Sic1 (compare the levels of isoforms 5 and 6 in WT and hog1Δ versus mpk1Δ cells in Fig. 4b). Together, these data pinpoint a potential role for Mpk1 in direct phosphorylation of Thr173 in Sic1. Corroborating this assumption, we further found that Mpk1-HA3, but not kinase-dead Mpk1KD-HA3, strongly phosphorylated Sic1-Thr173 in vitro (Fig. 4c; notably, the respective signal was almost entirely abrogated by introduction of the Thr173 to Ala mutation in Sic1, indicating that the anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies are also exquisitely specific in vitro). In addition, rapamycin treatment not only stimulated the activity of Mpk1 towards Thr173 in Sic1 10.4-fold (±2.6 s.d.; three independent time-course experiments; Fig. 4d), but also significantly boosted the interaction of Mpk1 with Sic1 in vivo (Fig. 4e). From these studies, we infer that Mpk1 directly phosphorylates Sic1-Thr173 in vivo, thereby contributing to Sic1 stability when TORC1 is attenuated. Expectedly, therefore, loss of Mpk1, but not of Hog1, also caused a significant G1 arrest defect in rapamycin-treated cells (Fig. 4f; Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Mpk1 phosphorylates Thr173 in Sic1.

(a) Mpk1, but not Hog1, is required for normal Sic1 accumulation in rapamycin-treated cells. Levels of Sic1-myc13 and of Sic1-myc13-pThr173 signals were determined in cells with the indicated genotypes before (0 h) and following a rapamycin treatment (for 2 and 4 h). The Sic1-myc13 levels or Sic1-myc13-pThr173 signals (three independent experiments) were normalized to Adh1 in each case, calculated relative to the value in 4-h rapamycin-treated wild-type cells (set to 1.0), and expressed as mean values (±s.d.). (b) Phos-tag phosphate affinity gel electrophoresis analysis of genomically myc13-tagged Sic1 from exponentially growing (time 0 h) and rapamycin-treated (2 and 4 h) WT, mpk1Δ and hog1Δ cells were carried out as in Fig. 2c. (c) Mpk1 phosphorylates Thr173 in Sic1 in vitro. Mpk1-HA3 and kinase-dead Mpk1KD-HA3 (carrying the K54R mutation) were purified from rapamycin-treated (1 h) cells and used for in vitro protein kinase assays on bacterially purified GST-Sic1 or GST-Sic1T173A. Levels of Sic1 protein and of Sic1-pThr173 signals were determined using anti-GST and anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies, respectively. Immunoblot analysis using anti-HA antibodies served as input control for Mpk1-HA3 variants. Mpk1-HA3, but not Mpk1KD-HA3, displayed slow-migrating isoforms due to post-translational modifications. (d) Rapamycin treatment strongly stimulates Mpk1 protein kinase activity towards Thr173 in Sic1. In vitro protein kinase assays were carried out as in c for the indicated times using Mpk1-HA3 preparations from exponentially growing (EXP) or rapamycin-treated (1 h; RAP) cells. (e) Rapamycin treatment stimulates the interaction between Sic1-myc13 and Mpk1-HA3. Plasmid-encoded Mpk1-HA3 was immunoprecipitated from extracts of untreated (0 min) and rapamycin-treated (RAP; 20 and 40 min) Sic1-myc13-expressing WT cells. Cells carrying an empty vector (−) were used as control. The co-precipitated Sic1-myc13 levels were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-myc antibodies. (f) Proper G1 arrest in rapamycin-treated cells requires Mpk1. FACS analyses (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for quantifications of triplicates) and BI determinations were performed as in Fig. 1a. All strains (relevant genotypes indicated) are isogenic to JK9-3D (see Fig. 1b,c for comparison). FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Mpk1 and PP2ACdc55 reciprocally control Sic1-pThr173

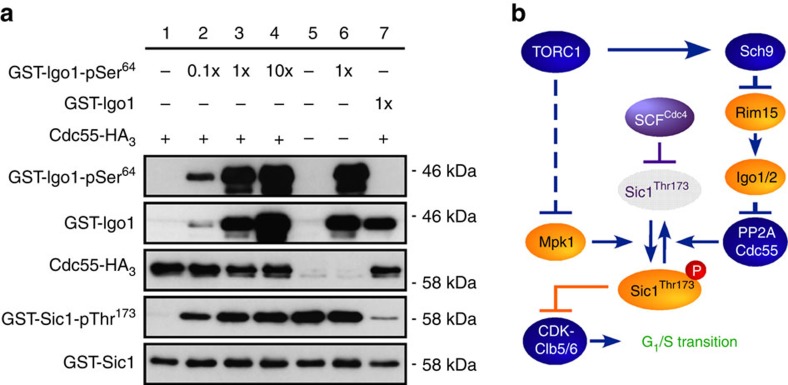

Since we were able to phosphorylate Sic1-Thr173 with Mpk1, we also examined whether PP2ACdc55 could directly dephosphorylate this residue in vitro. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, PP2ACdc55 indeed very efficiently dephosphorylated pThr173 in Sic1 in these assays (Fig. 5a, lane 1 versus lane 5). In addition, following prior activation by Rim15, Igo1 (Igo1-pSer64; Fig. 5a, lanes 2–4), but not inactive Igo1 (Fig. 5a, lane 7), efficiently inhibited the respective PP2ACdc55 activity in a concentration-dependent manner. Thus, Mpk1 and PP2ACdc55 directly and antagonistically control the phosphorylation status of Thr173 in Sic1 both in vitro and within cells. Of note, since Sic1-Thr173 phosphorylation was not fully abolished in the absence of Mpk1 (in mpk1Δ), nor in the presence of unrestricted PP2ACdc55 (in rim15Δ or igo1/2Δ cells), we expected the combination of mpk1Δ with either rim15Δ or igo1/2Δ to cause an additive G1 arrest defect in rapamycin-treated cells. This was indeed the case (Fig. 4f).

Figure 5. TORC1 coordinates G1–S cell cycle progression via Mpk1 and PP2ACdc55.

(a) PP2ACdc55 dephosphorylates pThr173 in Sic1 and this activity is inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by activated Igo1 (Igo1-pSer64), but not inactive Igo1. GST-Sic1 was phosphorylated by Mpk1 in vitro before being used as a substrate for the PP2ACdc55 phosphatase assay. Phosphatase activity of PP2ACdc55 was analysed in the absence (lane 1) and in the presence of increasing amounts (lanes 2, 3 and 4, respectively) of recombinant Igo1-pSer64, which had been subjected to thio-phosphorylation by Rim15 previously. Assays without both PP2ACdc55 and Igo1-pSer64 (lane 5), without PP2ACdc55 but with Igo1-pSer64 (lane 6), and with PP2ACdc55 combined with inactive Igo1 (lane 7) were included as additional controls. The levels of Ser64 phosphorylation in GST-Igo1 (GST-Igo1-pSer64), GST-Igo1, Cdc55-HA3, Thr173 phosphorylation in GST-Sic1 (GST-Sic1-pThr173) and GST-Sic1 were determined by immunoblot analyses using phospho-specific anti-Igo1-pSer64, anti-GST, anti-HA, phospho-specific anti-Sic1-pThr173 and anti-GST antibodies, respectively. (b) Model for the role of TORC1 in regulating the phosphorylation status and stability of the CDKI Sic1. For the sake of clarity, we have not schematically depicted the additional role of Rim15-Igo1/2 in G1 cyclin downregulation that may transiently favour CDK-mediated multi-site phosphorylation and consequently SCFCdc4-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of Sic1 following TORC1 inactivation. Sic1 inhibits the CDK–Clb5/6 complexes to prevent transition into S phase43. Arrows and bars denote positive and negative interactions, respectively. Solid arrows and bars refer to direct interactions, the dashed bar refers to an indirect interaction. For details see text.

Discussion

TORC1 coordinates START with nutrient availability in part by tightly regulating the phosphorylation status of Thr173 within the CDKI Sic1 (Fig. 5b). Together with the previous observations (i) that Sic1 only marginally interacts with the catalytic SCFCdc4 subunit Cdc34 in rapamycin-treated cells6 and (ii) that the introduction of a phosphomimetic Glu at position 173 of Sic1 compromises its capacity to interact with Cdc4 (ref. 37), our present data are best explained in a model in which phosphorylation of Thr173 in Sic1 serves to stabilize Sic1 by preventing (directly or indirectly) its association with SCFCdc4. Of note, Cln-CDK downregulation following TORC1 inhibition, which transiently relies on Rim15 and Igo1/2 (Fig. 1e,f), presumably also contributes to the latter process. It will therefore be interesting in future studies to decipher the respective Rim15- and Igo1/2-dependent and -independent mechanism(s) by which TORC1 controls transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional control of G1 cyclin expression.

Finally, Sic1 is functionally and structurally related to the mammalian CDKI p27Kip1, an atypical tumour suppressor that regulates the G0–S cell cycle transition by inhibiting cyclin-CDK2-containing complexes40. Similar to Sic1, p27Kip1 turnover is stimulated by direct cyclin-CDK2-mediated phosphorylation, followed by SCFSkp2-dependent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in proliferating cells. In quiescent G0 cells, in contrast, phosphorylation of specific alternative residues ensures p27Kip1 stability40. Since p27Kip1 also mediates in part the anti-proliferative effects of rapamycin4, it will be interesting to study whether and to what extent our findings in yeast may have been evolutionarily conserved.

Methods

Strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast cells were pre-grown overnight at 30 °C in standard synthetic defined (SD) medium with 2% glucose and supplemented with the appropriate amino acids for maintenance of plasmids. Before the experiments, cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.001 in SD and grown until they reached an OD600 of 0.4. Rapamycin was dissolved in 10% Tween-20/90% ethanol and used at a final concentration of 200 ng ml−1. Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Epitope-tagged proteins studied were expressed from their genomic locus, except GST-Sic1, Mpk1-HA3 and Cdc55-HA3 that were expressed from plasmids (under the control of their own promoter) to be used for the in vitro protein kinase and phosphatase assays.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis

A measure of 1.5 ml samples were collected at the indicated time points after rapamycin treatment, centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml 70% ethanol. Following overnight incubation at 4 °C, cells were washed once with H2O, centrifuged, resuspended in 250 μl of RNAse solution (50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 200 μg ml−1 RNAse A (Axonlab AG)) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were centrifuged again, resuspended in 250 μl of propidium idodide solution (50 mM Na+-citrate (pH 7.0) and 10 μg ml−1 propidium idodide (Sigma)) and analysed in a CyFlow (PARTEC) flow cytometer. Data were processed using the FlowJo software.

Northern blot and immunoblot analyses

Northern blot analyses were performed according to our standard protocol18 and the respective uncropped scans have been included in Supplementary Fig. 7. Total protein extracts were prepared by mild alkali treatment of cells followed by boiling in standard electrophoresis buffer41. SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analyses were performed according to standard protocols. For the analysis of protein phosphorylation states, we used Phos-tag acrylamide gel electrophoresis42. Anti-Sic1, (sc-50441; Santa Cruz), anti-c-Myc (9E10; sc-40; Santa Cruz), anti-Adh1 (Calbiochem), phospho-specific anti-Sic1-pThr173 (produced by GenScript), anti-GFP (Roche), phospho-specific anti-Igo1-pSer64 (ref. 24), anti-GST (Lubio) and anti-HA antibodies (Enzo) were used at 1:1,000, 1:3,000, 1:200,000, 1:1,000, 1:3,000, 1:1,000, 1:1,000 and 1:1,000 dilutions, respectively. Goat anti-rabbit/anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (BioRad) were used at a 1:3,000 dilution. All immunoblots presented in the main text have been included as uncropped scans in Supplementary Figs 8–25.

Co-immunoprecipitation

For co-immunoprecipitation analyses, Sic1-myc13- and Mpk1-HA3-expressing cells were fixed for 20 min with 1% formaldehyde, quenched with 0.3 M glycine, washed once with Tris-buffered saline, centrifuged and subsequently frozen (−80 °C). Lysates were prepared by disruption of frozen cells in lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40 and 1 × protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche)) with glass beads (0.5-mm diameter) using a Precellys cell disruptor and subsequent clarification by centrifugation (5 min at 14,000 r.p.m.; 4 °C). Mpk1-HA3 was immunoprecipated with anti-HA magnetic matrix (Pierce) and co-immunoprecipitated Sic1-myc13 was determined by immunoblot analysis using anti-c-Myc antibodies.

Mpk1 protein kinase assays

Mpk1-HA3 or Mpk1K54R -HA3was immunopurified from yeast cells using anti-HA magnetic matrix (Pierce). The respective matrices were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C with 3 μl of bacterially purified GST-Sic1 or GST-Sic1T173A in 50 μl of kinase buffer mix (125 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol and 10 mM ATP). The reactions were stopped by addition of loading buffer, boiled at 95 °C and analysed by immunoblot analyses. For the Mpk1 kinase time-course experiment, Mpk1-HA3 was purified from exponentially growing or rapamycin-treated (1 h) cells. The protein kinase reactions (with bacterially purified GST-Sic1 as substrate) were stopped at the indicated time points by addition of loading buffer and subsequent boiling (5 min).

PP2ACdc55 protein phosphatase assay

Cdc55-HA3 was isolated from exponentially growing cdc55Δ cells carrying the pRS416-CDC55-HA3 plasmid. Cdc55-HA3 was immunoprecipitated from total extracts in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40 and 1 × protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails from Roche) using anti-HA magnetic matrix (Pierce). Igo1-GST and Igo1S64A-GST were isolated from bacteria using glutathione sepharose (GE Healthcare) and phosphorylated where indicated by yeast-purified GST-Rim15-HA3 using 1 mM adenosine 5'-[γ-thio] triphosphate17,22. The in vitro phosphatase assay (30 min at 30 °C) was performed in phosphatase buffer (10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EGTA) with purified PP2ACdc55, bacterially purified Sic1-GST that was phosphorylated by Mpk1 in vitro as substrate, and different concentrations of Igo1, which was, or was not, subjected to in vitro phosphorylation by Rim15 before the use. To assess PP2ACdc55 activity, the decrease in Sic1T173 phosphorylation was detected using phospho-specific anti-Sic1-pThr173 antibodies. Levels of immunoprecipitated Cdc55-HA3 were assessed using anti-HA antibodies.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Moreno-Torres, M. et al. TORC1 controls G1–S cell cycle transition in yeast via Mpk1 and the greatwall kinase pathway. Nat. Commun. 6:8256 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9256 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-25, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank Séverine Bontron for strains, plasmids and discussions, and Louis-Félix Bersier for advice regarding statistical analyses. This research was supported by the Canton of Fribourg and grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Novartis Foundation (C.D.V).

Footnotes

Author contributions M.M.-T. designed and performed experiments. M.J. helped with experimental design and procedures. C.D.V. conceived and directed the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and interpreted the data together.

References

- Soulard A., Cohen A. & Hall M. N. TOR signaling in invertebrates. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 825–836 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R., Efeyan A. & Sabatini D. M. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 21–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Culotti J., Pringle J. R. & Reid B. J. Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. Science 183, 46–51 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. & Proud C. G. Nutrient control of TORC1, a cell-cycle regulator. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 260–267 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman J. J., Chen H. & Laribee R. N. Environmental signaling through the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1: mTORC1 goes nuclear. Cell Cycle 13, 714–725 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzalla V., Graziola M., Mastriani A., Vanoni M. & Alberghina L. Rapamycin-mediated G1 arrest involves regulation of the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 1482–1494 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet N. C. et al. TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 25–42 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta L., Gingras A. C., Svitkin Y. V., Hall M. N. & Sonenberg N. Rapamycin blocks the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and inhibits cap-dependent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 15, 658–664 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenis M. & Schmidt E. V. Coupling of cell division to cell growth by translational control of the G1 cyclin CLN3 in yeast. Genes Dev. 11, 2522–2531 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. M., Correll C. C., Kaplan K. B. & Deshaies R. J. A complex of Cdc4p, Skp1p, and Cdc53p/cullin catalyzes ubiquitination of the phosphorylated CDK inhibitor Sic1p. Cell 91, 221–230 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C. et al. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86, 263–274 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D., Craig K. L., Tyers M., Elledge S. J. & Harper J. W. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell 91, 209–219 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski M. D. & Deshaies R. J. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Virgilio C. The essence of yeast quiescence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 306–339 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza D., Ghavidel A., Heitman J. & Schultz M. C. Rapamycin induces the G0 program of transcriptional repression in yeast by interfering with the TOR signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4463–4470 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanke V., Pedruzzi I., Cameroni E., Dubouloz F. & De Virgilio C. Regulation of G0 entry by the Pho80-Pho85 cyclin-CDK complex. EMBO J. 24, 4271–4278 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders A., Bürckert N., Boller T., Wiemken A. & De Virgilio C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae cAMP-dependent protein kinase controls entry into stationary phase through the Rim15p protein kinase. Genes Dev. 12, 2943–2955 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedruzzi I. et al. TOR and PKA signaling pathways converge on the protein kinase Rim15 to control entry into G0. Mol. Cell 12, 1607–1613 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J. et al. Sch9 is a major target of TORC1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 26, 663–674 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi-Ayachi A. et al. The substrate of Greatwall kinase, Arpp19, controls mitosis by inhibiting protein phosphatase 2A. Science 330, 1673–1677 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S., Maslen S. L., Skehel M. & Hunt T. Greatwall phosphorylates an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A that is essential for mitosis. Science 330, 1670–1673 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontron S. et al. Yeast endosulfines control entry into quiescence and chronological life span by inhibiting protein phosphatase 2A. Cell Rep. 3, 16–22 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Talarek N. & De Virgilio C. Initiation of the yeast G0 program requires Igo1 and Igo2, which antagonize activation of decapping of specific nutrient-regulated mRNAs. RNA Biol. 8, 14–17 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talarek N. et al. Initiation of the TORC1-regulated G0 program requires Igo1/2, which license specific mRNAs to evade degradation via the 5'-3' mRNA decay pathway. Mol. Cell 38, 345–355 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedruzzi I., Bürckert N., Egger P. & De Virgilio C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ras/cAMP pathway controls post-diauxic shift element-dependent transcription through the zinc finger protein Gis1. EMBO J. 19, 2569–2579 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S. & Hunt T. Protein phosphatases and their regulation in the control of mitosis. EMBO Rep. 13, 197–203 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzenberger C. & Gerlich D. W. Phosphatases: providing safe passage through mitotic exit. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 469–482 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanes M. A. et al. Budding yeast greatwall and endosulfines control activity and spatial regulation of PP2ACdc55 for timely mitotic progression. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003575 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossio V., Kazatskaya A., Hirabayashi M. & Yoshida S. Comparative genetic analysis of PP2A-Cdc55 regulators in budding yeast. Cell Cycle 13, 2073–2083 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R. & Engelberg D. Commonly used Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains (e.g., BY4741, W303) are growth sensitive on synthetic complete medium due to poor leucine uptake. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273, 239–243 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J., Movva N. R. & Hall M. N. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 253, 905–909 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toone W. M. et al. Rme1, a negative regulator of meiosis, is also a positive activator of G1 cyclin gene expression. EMBO J. 14, 5824–5832 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Virgilio C. & Loewith R. Cell growth control: little eukaryotes make big contributions. Oncogene 25, 6392–6415 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. Regulation of the cell cycle by protein phosphatase 2A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 440–449 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R. Phosphorylation of Sic1p by G1 Cdk required for its degradation and entry into S phase. Science 278, 455–460 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R. L., Zinzalla V., Mastriani A., Vanoni M. & Alberghina L. Subcellular localization of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor Sic1 is modulated by the carbon source in budding yeast. Cell Cycle 4, 1798–1807 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoté X., Zapater M., Clotet J. & Posas F. Hog1 mediates cell-cycle arrest in G1 phase by the dual targeting of Sic1. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 997–1002 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard A. et al. The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3475–3486 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J., Di Como C. J., Herrero E. & De La Torre-Ruiz M. A. Regulation of the cell integrity pathway by rapamycin-sensitive TOR function in budding yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43495–43504 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu I. M., Hengst L. & Slingerland J. M. The Cdk inhibitor p27 in human cancer: prognostic potential and relevance to anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 253–267 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov V. V. Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast 16, 857–860 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita E., Kinoshita-Kikuta E., Takiyama K. & Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 749–757 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis M. Sic1 as a timer of Clb cyclin waves in the yeast cell cycle—design principle of not just an inhibitor. FEBS J. 279, 3386–3410 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-25, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References