Abstract

Background

Urine proteins may help understand physiology and diagnose disease in premature infants. Understanding how urine proteins vary by degree of prematurity, sex and postnatal day is warranted.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study to assess the independent correlation of 14 urine biomarkers (measured on postnatal days 1–4) with gestational age (GA), sex, and postnatal age in 81 premature infants (mean 1017 grams) without acute kidney injury using random effects mixed model.

Results

Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) showed significant associations for sex, GA, and postnatal age. Cystatin C, Osteopontin (OPN), and Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) were associated with postnatal age and GA, but not sex. Epithelial growth factor (EGF) and uromodulin were associated with GA only. clusterin was associated with postnatal age and sex. Albumin was associated with sex only. Beta-2-microglbulin (B2M), osteoactivin, kidney injury molecule -1 (KIM-1), and alpha Glutathione S-Transferase (αGST) were associated with postnatal age only.

Conclusion

Postnatal age affects B2M, Cystain C, NGAL, OPN, Clusterin, Kim-1, Osteoactivin, TFF3, VEGF, αGST. GA affects Cystatin C, EGF, NGAL, OPN, UMOD, TFF3, and VEGF. Sex affects albumin, NGAL, clusterin. Interpretation of urine biomarker will need to account for these associations.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, acute renal failure, infant, reference, baseline, NGAL, KIM-1, Cystatin C

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of urine protein can provide insights into the pathophysiology and diagnosis of disease. We and others have recently shown that urine biomarkers can not only predict acute kidney injury (AKI), but also mortality in premature and near term/term infants.(1, 2) Recently, numerous studies on urine AKI biomarkers, including neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), Cystatin C, and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and many others have shown promise in the ability to detect AKI in many critically ill populations. (3–6). These and other markers can also predict hard clinical outcomes such as mortality and could serve to improve our understanding of important pathobiological pathways. AKI is associated with reduced survival and poor outcomes in neonatal and pediatric populations (7–9); yet its diagnosis is challenging as current traditional biomarkers such as serum creatinine (SCr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or urine output determine changes in renal function (not damage), therefore, are later indicators of kidney insult and are not specific for renal damage (8, 10, 11). Interpretations of SCr changes in neonates are further complicated as the initial SCr reflects maternal SCr, which improves over the first weeks of life, and inversely related to the degree of immaturity.(12)

For any biomarker, the parameters, which impact serum or urine concentrations, are important to understand before applying their use to predict clinical outcomes. In premature infants, we and others have shown that values for urine biomarkers significantly vary by gestational age (GA)(12). This is likely due to abnormalities in tubular function present in premature infants. Similarly, sex differences affect NGAL levels in premature infants(12, 13) and other cohorts(14). Insight about how urine biomarker concentrations change in the first few days of life, across gestational age categories and sex are critical to make proper inferences about the pathophysiology, the diagnosis of AKI and other outcomes.

In order to study the variability and association between 14 urine biomarkers, with gestational age, sex, and postnatal age, we performed a prospective cohort study on 81 premature infants without AKI. We hypothesize that different urine biomarkers have decreasing/increasing trends over time after birth, differ by GA and sex. To answer our hypotheses, we assessed the independent correlation of 14 biomarkers with GA, sex, and age, after controlling for these variables and their interactions.

STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS

Study population

Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants with birthweight (BW) ≤ 1200 grams and/or ≤31 weeks gestational age admitted to the regional NICU at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) between February 2012 and June 2013 were enrolled in this prospective cohort study. Newborns were excluded if they had known congenital kidney disease, developed AKI in the first two weeks after birth, or if they did not survive beyond the first 48 hours of life. The study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board, informed parental consent was obtained, and LBW infants eligible for the study were enrolled. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

For each enrolled infant, infant demographics (i.e., birth weight, GA, sex, race, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes), and maternal demographics (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, smoking, prenatal care, and parity) were collected. Race was defined as Black, White, and Other. GA was categorized as <26 weeks, 26–27 weeks, 28–29 weeks, and ≥ 30 weeks. In order to ascertain whether a child developed AKI within the first 2 weeks of life, we measured SCr at postnatal days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12–14 on most infants, in addition to any clinically measured values. The mean number of SCr values obtained for each patient during the first 2 weeks of life was 5 (range 2–14). Neonatal AKI was defined according contemporary definition modified for neonates, similar to KDIGO AKI definition by which a SCr rise by ≥ 0.3 mg/dl from baseline defines AKI. The lowest previous SCr serves as the baseline for each SCr measurement. The reason that each SCr has a unique baseline level is because on postnatal day 1 SCr reflects maternal creatinine which decreases steadily over the first weeks of life (1,2).

Biomarker Analysis

Urine was collected daily during the first 4 days of life using cuddle buns™ (Small Beginnings, Hersperia, CA, USA) diapers placed at the perineum. The moist part of the diaper was cut out and placed in a syringe. Urine was squeezed into a centrifuge tube using the syringe plunger and centrifuged for 10 minutes to separate urine. The supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −70° C until the evaluation. Urine biomarker analysis was performed on multi-array plates by electrochemiluminescence using the Sector Image 2400 (Meso Scale Discovery (MSD); Gaithersburg, MD). Albumin, Beta-2-Microglobulin (B2M), Cystatin C, epithelial growth factor (EGF), NGAL, osteopontin (OPN), and uromodulin (UMOD) were measured in urine with MSD Human Kidney Injury Panel 5 Kit assay. Alpha Glutathione S-Transferase (αGST), Calbindin, Clusterin, KIM-1, Osteoactivin, Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were measured with MSD Human Kidney Injury Panel 3 Kit Assay. Samples in the panel 3 were diluted 10-fold before being added to the plate. Samples in the panel 5 were diluted 500-fold before being added to the plate. Samples were added to plates and prepared as stated in manufacturer protocol and analyzed on SECTOR Imager. All samples were run in duplicate. All analytes detected in the samples were in the range of the standard curve. The inter-run %CV (coefficient of variance) and intra-run %CV, the variability of samples and standards between and in runs, was below 10% in all cases, and below 5% in most sample/standard comparisons.

Statistical Analysis

Raw biomarker concentrations were recorded as pg/ml, and reported as ng/ml after appropriate unit conversions. These values were corrected for urine creatinine (UCr) concentrations to account for the variability in urine dilution. To report biomarker differences by gestational age (unadjusted by day of life), samples from all 4 days were averaged. Shapiro-Wilk test and normal probability plot were used to test for normality of data. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine the differences for non-normal data.

When conducting models to describe the impact of postnatal age on biomarker values, we normalized the data using the natural logarithm (ln). A random effects mixed model was used to examine whether the variance and mean of the biomarkers of interest was dependent on day of life, sex, and gestational age. In the mixed model analysis, unconditional means model was used to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in order to determine the proportion of biomarker variance (i.e., due to differences in levels by individual). To examine between- and within-person effects, a linear growth model was used to calculate the proportion of variance (POV) explained for both between and within-person variance. In addition, the effects of gender and GA on mean values of biomarkers were estimated adjusting for day of life (DOL) and the other variable (i.e., the full model). In order to understand the potential confounding effects of gender and GA on the variance by which day affects biomarker level, and also to evaluate their predictive impact on biomarker level, we added GA and gender to the linear growth model with DOL and intercept as the random effect. The proportion of variance explained between-person (POVb) for GA and gender is the proportion of the explainable variation in biomarker level that can be explained by each predictor after being added to the linear growth model; the associated p-value corresponds to the slope of the mean biomarker level by either parameter. A p-value for fixed effects < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

The incidence rate of AKI was 30/111 (27%). We report data for only the 81 infants without AKI. Maternal and infant demographics for the 81 neonates without AKI are shown in table 1. Biomarker concentrations (averaged over the first four days of life) were significantly different across gestational age categories for albumin, cystatin c, EGF, NGAL, UMOD, and osteoactivin (Table 2). After adjusting for urine creatinine, Albumin, Cystatin C, NGAL, OPN, TFF3 were significantly different across gestational age categories (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographics among 81 neonates without acute kidney injury (AKI)

| Infant Demographics | |

| Birth Weight (Mean ± SD) | 1017 ± 298 |

| Apgar 1 min (Median, IQR) | 5 (2–6) |

| Apgar 5 min (Median, IQR) | 7 (7–8) |

| Gender (N, %) | |

| Female | 38 (46.9) |

| Race (N, %) | |

| Black | 44 (54.3) |

| White | 30 (37.0) |

| Other | 7 (8.7) |

| Gestational Age (N, %) | |

| <26 weeks | 13 (16.1) |

| 26–27 weeks | 20 (24.7) |

| 28–29 weeks | 30 (37.0) |

| ≥30 weeks | 18 (22.2) |

| Maternal Demographics (N, %) | |

| Prenatal care | 76 (93.8) |

| Diabetes | 8 (9.9) |

| Hypertension | 21 (25.9) |

| Smoking | 10 (12.4) |

| Multiparity | 22 (27.2) |

Table 2.

Average absolute biomarker concentration (during the first 4 days) across gestational age categories

| Concentra- tion (ng/ml) |

<26 wk (N=13) | 26–27 wk (N=20) | 28–29 wk (N=30) | ≥30 wk (N= 18) | p* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Me- dian |

IQR | 2.5 %– 97.5 % |

Me- dian |

IQR | 2.5% – 97.5 % |

Me- dian |

IQR | 2.5%– 97.5 % |

Me- dian |

IQR | 2.5 %– 97.5 % |

||

| Albumin | 24200 | 22300–42273 | 12614–99564 | 18866 | 13396–37453 | 3216–246705 | 26714 | 16536–45713 | 5578–2408044 | 17196 | 11100–21692 | 6154–72746 | <0.04 |

| B2M | 8876 | 7325–12325 | 1725–23700 | 10242 | 6036–12485 | 1928–19546 | 8606 | 4652–11200 | 515–25465 | 8561 | 6172–15244 | 2769–27900 | 0.83 |

| CystatinC | 1354 | 493–1807 | 75–2962 | 844 | 320–1173 | 33–4863 | 358 | 157–830 | 32–9713 | 209 | 85–632 | 18–3702 | 0.03 |

| EGF | 0.75 | 0.61–1.04 | 0.51–1.77 | 0.79 | 0.53–1.02 | 0.35–2.85 | 1.40 | 1.07–1.62 | 0.39–5.12 | 1.45 | 1.02–1.80 | 0.39–2.81 | <0.001 |

| NGAL | 298 | 194–640 | 153–3409 | 276 | 110–406 | 37–6943 | 210 | 139–559 | 7–2928 | 48 | 33–211 | 8–2460 | 0.01 |

| OPN | 466 | 395–638 | 180–1439 | 373 | 261–642 | 90–2734 | 410 | 239–728 | 59–1651 | 347 | 239–517 | 106–1850 | 0.59 |

| UMOD | 744 | 613–955 | 345–2910 | 977 | 763–1367 | 272–2766 | 1373 | 1126–2034 | 279–5193 | 1447 | 953–1902 | 168–7671 | 0.001 |

| Clusterin | 177 | 115–194 | 79–468 | 165 | 75–217 | 15–537 | 176 | 111–261 | 25–1384 | 115 | 80–315 | 23–1341 | 0.51 |

| KIM-1 | 3.16 | 1.68–4.53 | 0.86–9.69 | 1.91 | 1.14–2.59 | 0.39–6.64 | 2.63 | 1.41–3.95 | 0.52–33.15 | 2.04 | 0.99–2.92 | 0.72–7.34 | 0.23 |

| Osteoactivin | 1.25 | 0.88–1.72 | 0.45–2.36 | 1.11 | 0.88–1.39 | 0.37–5.73 | 1.53 | 1.31–2.42 | 0.50–8.50 | 1.58 | 1.34–2.34 | 0.61–3.65 | 0.03 |

| TFF3 | 9.34 | 4.80–24.35 | 1.53–41.84 | 7.71 | 4.60–15.42 | 0.92–72.17 | 10.81 | 6.34–16.20 | 1.08–44.38 | 5.21 | 2.83–8.47 | 0.93–62.41 | 0.17 |

| VEGF | 0.94 | 0.74–1.94 | 0.51–3.54 | 0.75 | 0.58–1.13 | 0.31–7.09 | 1.01 | 0.79–1.34 | 0.20–3.12 | 0.72 | 0.50–1.35 | 0.40–5.24 | 0.15 |

| Calbindin | 6.32 | 3.96–7.31 | 0.98–13.10 | 3.79 | 2.78–7.68 | 0.97–20.59 | 5.90 | 3.67–9.11 | 1.30–36.88 | 6.01 | 4.91–15.26 | 1.87–35.11 | 0.20 |

| GST | 0.21 | 0.06–0.53 | 0.03–1.21 | 0.13 | 0.01–0.30 | 0.00–1.78 | 0.09 | 0.04–0.24 | 0.00–49.60 | 0.18 | 0.04–0.92 | 0.00–86.17 | 0.48 |

| UCr (mg/dl) | 11.9 | 10.0–13.2 | 2.3–14.9 | 8.9 | 7.1–11.4 | 4.6–32.6 | 13.4 | 10.6–17.7 | 7.1–33.5 | 12.4 | 10.1–18.8 | 6.8–23.9 | 0.006 |

Estimated from a Kruskal-Wallis test

Table 3.

Average biomarker concentration (during the first 4 days) corrected for urine creatinine (UCr) across gestational age categories

| <26 wk (N=13) | 26–27 wk (N=20) | 28–29 wk (N=30) | ≥30 wk (N= 18) | p* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Medi- an |

IQ R |

2.5% – 97.5 % |

Medi- an |

IQ R |

2.5% – 97.5 % |

Medi- an |

IQ R |

2.5% – 97.5 % |

Medi- an |

IQ R |

2.5% – 97.5 % |

||

| Albumin | 2.12×10−1 | 1.74×10−1, 2.94×10−1 | 1.06×10−1, 4.28 | 2.22×10−1 | 1.43×10−1, 2.90×10−1 | 4.76×10−2, 2.18 | 1.81×10−1 | 9.77×10−2, 3.71×10−1 | 5.77×10−2, 1.20×10 | 1.21×10−1 | 8.71×10−2, 1.68×10−1 | 4.86×10−2, 6.03×10−1 | 0.04 |

| B2M | 7.38×10−2 | 6.08×10−2, 1.09×10−1 | 1.34×10−2, 5.09×10−1 | 9.93×10−2 | 4.70×10−2, 1.64×10−1 | 2.07×10−2, 2.12×10−1 | 7.16×10−2 | 3.32×10−2, 9.13×10−2 | 1.54×10−3, 1.60×10−1 | 7.71×10−2 | 5.26×10−2, 9.54×10−2 | 1.46×10−2, 2.45×10−1 | 0.20 |

| CystatinC | 1.15×10−2 | 4.56×10−3, 2.07×10−2 | 5.81×10−4, 5.82×10−2 | 8.98×10−3 | 3.30×10−3, 1.26×10−2 | 4.85×10−4, 2.96×10−2 | 3.03×10−3 | 9.61×10−4, 7.38×10−3 | 2.48×10−4, 4.24×10−2 | 1.50×10−3 | 5.25×10−4, 3.45×10−3 | 1.90×10−4, 4.82×10−2 | 0.006 |

| EGF | 7.60×10−6 | 6.20×10−6, 9.40×10−6 | 3.38×10−6, 2.63×10−5 | 8.30×10−6 | 5.90×10−6, 1.00×10−5 | 5.08×10−6, 1.63×10−5 | 1.02×10−5 | 7.40×10−6, 1.37×10−5 | 4.68×10−6, 2.14×10−5 | 1.07×10−5 | 8.80×10−6, 1.31×10−5 | 5.39×10−6, 1.40×10−5 | 0.14 |

| NGAL | 2.48×10−3 | 1.94×10−3, 1.32×10−2 | 1.14×10−3, 3.22×10−2 | 2.67×10−3 | 1.19×10−3, 5.39×10−3 | 4.28×10−4, 6.13×10−2 | 1.84×10−3 | 9.66×10−4, 4.32×10−3 | 7.59×10−5, 1.28×10−2 | 4.47×10−4 | 2.75×10−4, 1.25×10−3 | 5.83×10−5, 2.04×10−2 | 0.002 |

| OPN | 4.88×10−3 | 2.71×10−3, 5.79×10−3 | 1.51×10−3, 1.97×10−2 | 4.27×10−3 | 3.03×10−3, 6.80×10−3 | 1.06×10−3, 2.41×10−2 | 2.98×10−3 | 2.00×10−3, 4.00×10−3 | 6.10×10−4, 1.38×10−2 | 2.58×10−3 | 1.79×10−3, 3.77×10−3 | 1.05×10−3, 1.58×10−2 | 0.02 |

| UMOD | 6.76×10−3 | 5.91×10−3, 7.55×10−3 | 2.69×10−3, 2.75×10−2 | 1.24×10−2 | 7.46×10−3, 1.54×10−2 | 3.71×10−3, 3.42×10−2 | 1.09×10−2 | 9.26×10−3, 1.37×10−2 | 2.71×10−3, 2.46×10−2 | 1.04×10−2 | 8.21×10−3, 1.29×10−2 | 2.48×10−3, 3.80×10−2 | 0.06 |

| Clusterin | 1.35×10−3 | 9.30×10−4, 2.46×10−3 | 5.40×10−4, 6.85×10−3 | 1.37×10−3 | 7.11×10−4, 2.13×10−3 | 2.17×10−4, 4.74×10−3 | 1.21×10−3 | 7.07×10−4, 2.23×10−3 | 2.14×10−4, 9.40×10−3 | 8.98×10−4 | 7.63×10−4, 1.59×10−3 | 1.15×10−4, 1.77×10−2 | 0.67 |

| KIM-1 | 2.71×10−5 | 1.87×10−5, 4.28×10−5 | 5.76×10−6, 3.83×10−4 | 2.03×10−5 | 1.43×10−5, 2.92×10−5 | 4.52×10−6, 4.00×10−5 | 1.62×10−5 | 9.40×10−6, 3.41×10−5 | 3.21×10−6, 2.97×10−4 | 1.35×10−5 | 8.50×10−6, 2.38×10−5 | 3.62×10−6, 5.80×10−5 | 0.14 |

| Osteoactivin | 1.32×10−5 | 8.50×10−6, 1.73×10−5 | 2.98×10−6, 3.77×10−5 | 1.25×10−5 | 9.70×10−6, 1.58×10−5 | 4.49×10−6, 2.44×10−5 | 1.18×10−5 | 8.10×10−6, 1.74×10−5 | 4.28×10−6, 4.9×10−5 | 1.24×10−5 | 9.40×10−6, 1.75×10−5 | 3.21×10−6, 3.47×10−5 | 0.99 |

| TFF3 | 1.05×10−4 | 4.44×10−5, 2.81×10−4 | 1.14×10−5, 4.01×10−4 | 9.48×10−5 | 5.33×10−5, 1.42×10−4 | 1.37×10−5, 3.16×10−4 | 7.90×10−5 | 4.39×10−5, 1.12×10−4 | 7.20×10−6, 3.93×10−4 | 4.28×10−5 | 1.82×10−5, 6.70×10−5 | 5.60×10−6, 5.18×10−4 | 0.04 |

| VEGF | 1.20×10−5 | 6.90×10−6, 1.83×10−5 | 5.03×10−6, 2.68×10−5 | 8.20×10−6 | 6.70×10−6, 1.23×10−5 | 3.60×10−6, 2.18×10−5 | 7.30×10−6 | 5.10×10−6, 1.19×10−5 | 2.08×10−6, 2.62×10−5 | 5.70×10−6 | 4.70×10−6, 9.10×10−6 | 2.10×10−6, 4.34×10−5 | 0.07 |

| Calbindin | 5.89×10−5 | 4.14×10−5, 6.49×10−5 | 7.60×10−6, 1.64×10−4 | 3.70×10−5 | 2.93×10−5, 7.02×10−5 | 1.44×10−5, 1.79×10−4 | 4.47×10−5 | 2.65×10−5, 7.25×10−5 | 7.35×10−6, 1.81×10−4 | 5.32×10−5 | 3.64×10−5, 1.09×10−4 | 9.35×10−6, 2.50×10−4 | 0.31 |

| GST | 2.10×10−6 | 5.00×10−7, 5.70×10−6 | 2.20×10−7, 1.15×10−5 | 1.30×10−6 | 1.00×10−7, 3.90×10−6 | 0, 1.20×10−5 | 7.00×10−7 | 3.00×10−7, 2.00×10−6 | 0, 4.44×10−4 | 1.20×10−6 | 4.00×10−7, 3.80×10−6 | 0, 1.27×10−3 | 0.43 |

Estimated from a Kruskal-Wallis test

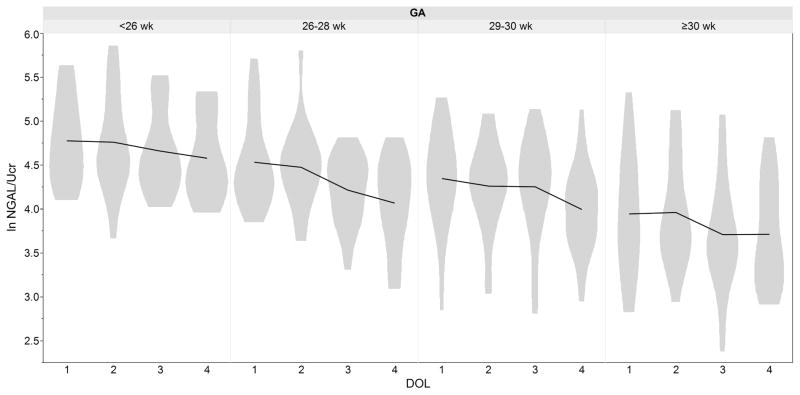

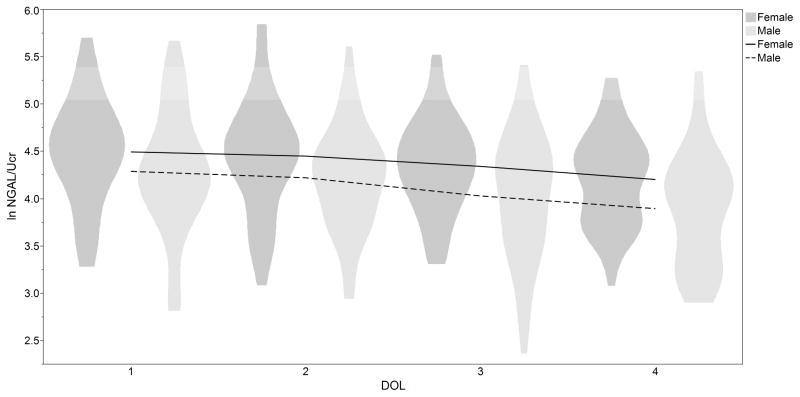

The independent associations of biomarkers with sex, GA, and postnatal age (natural log transformed and corrected for urine creatinine) are shown in Table 4. NGAL, and VEGF showed statistically significant associations for Sex, GA, and postnatal age (p< 0.05). Cystatin C, OPN, and TFF3 were associated with postnatal age and GA (all p< 0.05), but not sex. EGF and UMOD were associated with GA only (p<0.05). Clusternin was associated with postnatal age and sex p<0.05. Albumin was significantly associated with sex only (p< 0.05). B2M, Osteoactivin, KIM1, and αGST were associated with postnatal age only (p<0.05). Calbindin was not associated with GA, postnatal age, or sex. It should be noted that there were no significant interactions between GA, sex and day of life (DOL) (data not shown). To illustrate these relationships Figure 1 demonstrates ln NGAL over the first 4 days of life by GA. Figure 2 shows ln NGAL over time by sex.

Table 4.

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and proportion of variance (POV) explained by postnatal age (DOL), gestational age, and gender

| Postnatal Age | Gestational Age | Gender | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| ICC* | POVw† | P (unadjusted) | p (Full model) | POVb‡ | p (DOL-adjusted) | p (Full model) | POVb | p (DOL-adjusted) | p (Full model) | |

| ln Albumin/Cr | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.67 | 0.62 | −0.61 | 0.2 | 0.13 | −0.58 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| ln B2M/Cr | 0.41 | 0.41 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.38 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.54 | 0.84 | 0.71 |

| ln CystatinC/Cr | 0.68 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.21 | 0.005 | 0.004 | −0.49 | 0.36 | 0.25 |

| ln EGF/Cr | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.4 | −0.16 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| ln NGAL/Cr | 0.73 | 0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.18 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.46 | 0.02 | 0.003 |

| ln OPN/Cr | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.009 | 0.01 | −1.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −1.21 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| ln UMOD/Cr | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −2.34 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −2.32 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| ln Clusterin/Cr | 0.59 | 0.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.19 | 0.13 | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| ln KIM-1/Cr | 0.59 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.66 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.92 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| ln Osteoactivin/Cr | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.65 | 0.87 | 0.88 | −0.61 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| ln TFF3/Cr | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.63 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.81 | 0.43 | 0.28 |

| ln VEGF/Cr | 0.51 | 0.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ln Calbindin/Cr | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.2 | −1.77 | 0.69 | 0.7 | −1.73 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| ln GST/Cr | 0.51 | 0.44 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −1.35 | 0.21 | 0.22 | −1.50 | 0.5 | 0.54 |

ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

POVw: Proportion of Variance explained within-person

POVb: Proportion of Variance explained between-person

Figure 1.

Mean and distribution (range) for urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) corrected for urine creatinine over time by gestational age (GA) in 81 premature infants without acute kidney injury (AKI)

Figure 2.

Mean and distribution (range) for urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) corrected for corrected for urine creatinine over time by gender in 81 premature infants without acute kidney injury (AKI)

The between- and within-person variance of the biomarker levels differed among biomarkers. Those with an ICC close to 1 suggest high between-person variance, i.e. Cystatin C (ICC=0.68), NGAL (ICC=0.73), and TFF3 (ICC=0.63).

DISCUSSION

This prospective cohort study provides reference values for 14 candidate urine biomarkers of kidney damage in a sample population of premature infants without AKI. We provide data which suggest that most biomarker evaluated vary by gestational age and postnatal age, and that sex impacts reference values of albumin, NGAL, Clusterin, and VEGF, but not other studied biomarkers. These findings will be essential in future studies of urine biomarkers’ ability to predict AKI and other clinical outcomes in premature infants.

We also report normative ranges for 14 candidate urine biomarkers and urine biomarkers (corrected by urine creatinine) in premature infants without AKI. We report the, 2.5, 25, mean 75 and 97.5 percentiles for each biomarker according to gestational age categories. This data will be useful as a reference range for infants without AKI. Importantly, these reference values must be taken in context of several factors. First, the cohort had predefined inclusion criteria and more importantly the way we excluded those infant with AKI accoding the neonatal KDIGO AKI definition modified for newborns, which is an empiric working definition which may change over time. Second, the method of urine collection (for example is one use a urine bag, different types of cotton fibers balls, or directly from an indwelling urine catheter) may alter the values we publish herewith.

Several articles investigate the use of urinary biomarkers as a predictive and diagnostic tool for AKI in different populations (15–20). Lavery et al.(21) reported that NGAL has negative association with birth weight, which could be regarded a proxy for gestational age and in accordance with our results; however they did not find such association with DOL. This is likely due to small sample size in their study (N=20). A study by Huynh et al.(13) investigated urine NGAL measured between days 4–30 of life in premature infants in whom the likelihood of AKI was low, as they only measured urine in VLBW infants with uncomplicated courses. They found relatively lower overall levels of NGAL, which may reflect tubular maturity, and thus less urine NGAL. Our study corroborated their findings that NGAL concentrations are higher in female premature infants, decrease with higher gestational age and higher postnatal age. In a study of 48 premature infants, Genc et al.(19) concluded that there is no association between urinary KIM-1 level and either GA or sex and we can confirm their findings in our study of premature infants. These data corroborated our previous work (22) where we show that NGAL, Cystatin C, KIM-1, OPN, and B2M were inversely correlation with GA, and female sex was associated with higher NGAL. After excluding newborns with AKI in current study, the correlation of GA with KIM-1 and B2M is diminished (data not shown).

The strength of this study includes the comprehensive analysis of 14 potential candidate kidney injury biomarkers, and exclusion of infants who had AKI, using contemporary definitions, and large number of SCr values. We chose to analyze the 14 urine biomarker values as we were aiming to expand our knowledge of urine biomarkers in premature infants using the same technology/procedures we have done previously. Thus, we used the 7 plex mesoscale Acute kidney injury Kit 3. In addition, because we wanted to explore the role of KIM-1 in this cohort, and we wanted to maintain similar procedures, we added Acute Kidney Injury Kit 5. Doing the entire panel that had already been validated by the Mesoscale was the most efficient and effective way to perform the studies. We had adequate sample size to understand the biological pattern of change in the first postnatal days, and the modifying factors of GA, sex, and the interaction of all three variables. Additionally, we measured ICC and POV which indicate how much variability exist in biomarker concentrations and how much of that variability can be explained by GA, sex, and postnatal age. However, we acknowledge the limitations in our study: not all infants had urine samples collected for all four days, which could potentially decrease the accuracy of predictions. No differences in demographic characteristics were evident by the number of urine samples assessed, and thus we do not have any reason to believe that those individuals with missing values were systematically different to introduce bias. We also acknowledge that not all of the variability can be accounted for by the variables which we explored, as suggested by POVs. Hence, other variables and confounding effects (besides GA, sex and postnatal age) could impact baseline biomarker levels in premature infants. Considering our sample size, we could not include other potential modifying parameters in our study. It is important to bear in mind that these results reflect the characteristics of premature infants without AKI, and a comparative evaluation of these characteristics in AKI patients is essential before any interpretation.

In conclusion, in this patient population, postnatal age affects B2M, Cystatin C, NGAL, OPN, Clusterin, Kim-1, Osteoactivin, TFF3, VEGF, and αGST; Gestational age affects Cystatin C, EGF, NGAL, OPN, UMOD, TFF3, and VEGF; sex impacts albumin, NGAL, clusterin, and VEGF. It is necessary to account for these associations and variations when designing studies to investigate the diagnostic role of urinary biomarkers and clinical outcomes, and when using urine proteins to understand the pathophysiology of disease. Larger cohorts are needed to facilitate the exploration of more parameters that could potentially impact these biomarkers in VLBW infants.

Acknowledgments

Statement of financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Norman Siegel Career Development Award from the American Society of Nephrology. Dr. Askenazi receives funding from the NIH (R01 DK13608-01) and the Pediatric and Infant Center for Acute Nephrology (PICAN) which is sponsored by Children’s of Alabama and the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) under award number UL1TR00165. Dr. Ambalavanan receives funding from NIH (grant # U01 HL122626; R01 HD067126; R01 HD066982; U10 HD34216). Dr. Griffin receives funding from UAB CCTS, and PICAN.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of interest: Dr. Askenazi is speaker for The AKI Foundation.

References

- 1.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Hundley HE, Montesanti A, Parwar P, Sonjara S, Ambalavanan N. Urine Biomarkers Predict Acute Kidney Injury in Newborns. J Pediatr. 2012;161:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askenazi DJ, Montesanti A, Hunley H, Koralkar R, Pawar P, Shuaib F, Liwo A, Devarajan P, Ambalavanan N. Urine biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and mortality in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2011;159:907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shemin D, Dworkin LDZ. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for early acute kidney injury. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh CR, Garg AX. Testing new biomarkers for acute kidney injury: association, prediction, and intervention. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:987–989. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Fu C, Zhou X, Xiao Z, Zhu X, Jin M, Li X, Feng X. Urine interleukin-18 and cystatin-C as biomarkers of acute kidney injury in critically ill neonates. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:851–860. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-2072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han WK, Bailly V, Abichandani R, Thadhani R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:237–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuasuwan A, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury and its management. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;171:218–225. doi: 10.1159/000327198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein SL. Acute kidney injury in children: prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:163–172. doi: 10.1159/000329394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Himmelfarb J, Joannidis M, Molitoris B, Schietz M, Okusa MD, Warnock D, Laghi F, Goldstein SL, Prielipp R, Parikh CR, Pannu N, Lobo SM, Shah S, D’Intini V, Kellum JA. Evaluation and initial management of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:962–967. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04971107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soni SS, Ronco C, Katz N, Cruz DN. Early diagnosis of acute kidney injury: the promise of novel biomarkers. Blood Purif. 2009;28:165–174. doi: 10.1159/000227785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostermann M, Philips BJ, Forni LG. Clinical review: Biomarkers of acute kidney injury: where are we now? Crit Care. 2012;16:233. doi: 10.1186/cc11380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Levitan EB, Goldstein SL, Devarajan P, Khandrika S, Mehta RL, Ambalavanan N. Baseline Values of Candidate Urine Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Biomarkers Vary by Gestational Age in Premature Infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:302–306. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182275164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huynh TK, Bateman DA, Parravicini E, Lorenz JM, Nemerofsky SL, Sise ME, Bowman TM, Polesana E, Barasch JM. Reference values of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:528–532. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181baa3dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett MR, Nehus E, Haffner C, Ma Q, Devarajan P. Pediatric reference ranges for acute kidney injury biomarkers. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2989-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coca SG, Yalavarthy R, Concato J, Parikh CR. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and risk stratification of acute kidney injury: a systematic review. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dent CL, Ma Q, Dastrala S, Bennett M, Mitsnefes MM, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts acute kidney injury, morbidity and mortality after pediatric cardiac surgery: a prospective uncontrolled cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R127. doi: 10.1186/cc6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:194–200. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328343f4dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarafidis K, Tsepkentzi E, Diamanti E, Agakidou E, Taparkou A, Soubasi V, Papachristou F, Drossou V. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin to predict acute kidney injury in preterm neonates. A pilot study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:305–310. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genc G, Ozkaya O, Avci B, Aygun C, Kucukoduk S. Kidney injury molecule-1 as a promising biomarker for acute kidney injury in premature babies. Am J Perinato. 2013;30:245–252. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto K, Coelho S, Rodrigues B, Martins H, Frade F, Lopes S, Cunha L, Papoila AL, Devarajan P. Cystatin C as a marker of acute kidney injury in the emergency department. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1745–1754. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00690110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavery AP, Meinzen-Derr JK, Anderson E, Ma Q, Bennett MR, Devarajan P, Schibler KR. Urinary NGAL in premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:423–428. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318181b3b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Levitan EB, Goldstein SL, Devarajan P, Khandrika S, Mehta RL, Ambalavanan N. Baseline values of candidate urine acute kidney injury biomarkers vary by gestational age in premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:302–306. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182275164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]