Abstract

The detailed molecular interactions between Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) capsid protein (CA) hexamers have been elusive in the context of a native protein. We report crystal structures describing novel interactions between CA monomers related by 6-fold symmetry within a hexamer (intra-hexamer) and by 3-fold and 2-fold symmetry between neighboring hexamers (inter-hexamer). These structures help elucidate how CA builds a hexagonal lattice, the foundation of the mature capsid. Lattice structure depends on an adaptable hydration layer that modulates interactions among CA molecules. Disruption of this layer by crystal dehydration treatment alters inter-hexamer interfaces and condenses CA packing, highlighting an inherent structural variability. Capsid stability changes imparted by high concentrations of CA-targeting antiviral PF74 can be explained by variations at inter-hexamer interfaces remote to the ligand binding site. Inherent structural plasticity, hydration layer rearrangement, and effector molecule binding may perturb capsid uncoating or assembly and have functional implications for the retroviral life cycle.

The mature capsid of Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) is formed from a single multifunctional capsid protein (CA), which contains highly helical N-terminal (CANTD, residues 1-145) and C-terminal (CACTD, residues 150-231) domains connected by a flexible inter-domain region (residues 146-149) (1-5). The capsid is made from a lattice of ~250 CA hexamers closed by the insertion of 12 CA pentamers. The hexamer building block comprises an inner ring of six CANTDs held together by CANTD-CANTD and CANTD-CACTD contacts between adjacent CA molecules. The six CACTDs of CA hexamers form an outer “girdle” that is engaged in inter-hexamer interactions (1-5). CA-CA interactions are of critical importance for the structural integrity of the capsid and viral infectivity (1-3, 6-11). Following infection and fusion of the viral and cellular membranes, the capsid undergoes controlled dissasembly (or uncoating), which seems coordinated with reverse transcription (7, 9). Hence, CA is an attractive therapeutic target and several antivirals have been reported to bind at the CANTD or CACTD (12-17). Among them, PF-3450074 (PF74) has been reported to have a bimodal mechanism of action (18-21): at lower concentrations (nanomolar to ~2 μM) PF74 exerts its antiviral effect by directly competing with binding of nuclear host factors cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 6 (CPSF6) and nucleoporin 153 (NUP153), whereas at higher concentrations (~10 μM) it blocks the uncoating, assembly, and the reverse transcription steps of the viral life cycle (18-23). Crystal structures of PF74 in complex with the CANTD fragment alone (CANTD-PF74) (14) or more recently with crosslinked CA hexamers (CAXL-PF74) (18, 19), have provided important insights into the structural mechanism by which PF74 binds CA. It was shown that PF74 preferentially binds the hexamer form of CA at the same general site used by CPSF6 and NUP153. However, the structural mechanism by which high concentrations of PF74 affect uncoating and assembly remains incompletely defined. Such effect of CA-targeting drugs would be relevant in a therapeutic context where antivirals are used at concentrations significantly higher than their inhibitory effective concentrations (EC50).

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies combined with advanced molecular modeling have provided information on the hexagonal lattice of CA and helped build informative models of the mature HIV-1 capsid (2, 3, 24). X-ray and NMR structures of isolated CANTD and CACTD domains or full-length CA monomers or dimers have provided key details for interactions at the 2-fold interface (1-5, 16, 25, 26). Structures of engineered crosslinked CA hexamers (CAXL) or pentamers elucidated the interactions between CA subunits in the hexameric and pentameric building blocks (1, 3). Although engineered mutations improved the biophysical aggregation properties of the crosslinked hexamers they also affected key interactions at the 2-fold interfaces. Hence, despite advances, critical details regarding the CA-CA interactions that govern virus uncoating and assembly remain insufficiently described.

Here we describe the elusive crystal structure of native full-length CA in a form that reveals a complete set of inter- and intra-hexamer interactions. Additional structures illustrate how these interactions are altered by changing the hydration layer of the CA lattice or binding of a CA-targeting antiviral, highlighting a structural variability that may affect uncoating, assembly, host factor recognition, and trafficking across the capsid shell.

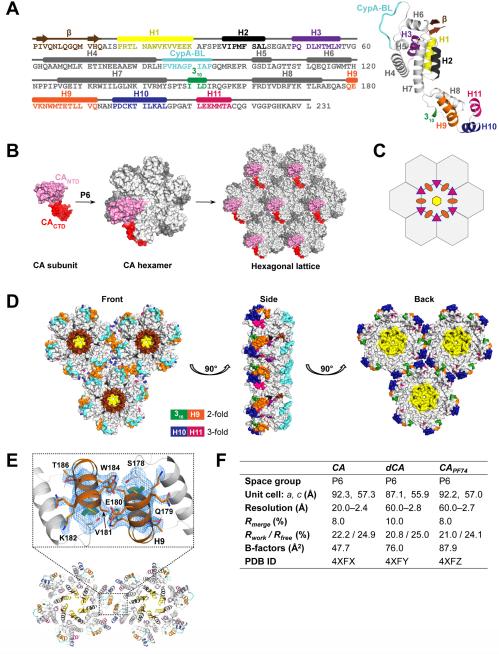

Native CA (CA) crystals were grown at low protein concentrations (<5 mg/ml), which may have reduced the propensity of native CA for aggregation without having to include any mutations (Fig. 1A). The protein crystallized in space group P6 with a single CA molecule per asymmetric unit (Fig. 1F, table S1). Crystallographic 6-fold symmetry generates CA hexamers, which in turn assemble the hexagonal lattice (Fig. 1B). CA subunits from neighboring hexamers are related by crystallographic 2-fold and 3-fold symmetry (Fig. 1, C and D). The structure of CA is in general agreement with the 9 Å resolution cryo-EM maps of the flattened CA hexagonal lattice (24) (fig. S1A) and tubes (2) (fig. S1B). The overall fold of CA is also in general agreement with the previously published crystal and NMR structures of full-length CA (1, 3-5, 24) and the CANTD and CACTD fragments (12, 14, 16, 25, 27, 28). The CANTD domain starts with a partially ordered β-hairpin, includes seven α-helices and a cyclophilin binding loop (CypA-BL) (Fig. 1A). The CANTD is followed by a short flexible hinge linker (1, 3-5) that leads to the CACTD, which comprises a 310-helix, an extended strand (major homology region) and four α-helices (H8-H11) (Fig. 1A). Key interactions between the CANTD and CACTD domains that are likely to stabilize the capsid particle are intra-hexamer CANTD-CANTD and CANTD-CACTD contacts among adjacent CA subunits around the 6-fold axis, inter-hexamer CACTD-CACTD contacts at the 2- and 3-fold axes (Fig. 1D) (1, 2) and to a lesser extent CANTD-CACTD intra-subunit contacts (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of native CA.

(A) Secondary structure and ribbon diagram of native CA. The CANTD (1-145) comprises β-hairpin (1-13, brown), CypA-BL (85-93, cyan), and seven α-helices: H1 (17-30; yellow), H2 (36-43; black), H3 (49-57; purple), and H4 (63-83), H5 (101-104), H6 (111-119), and H7 (126-145) in gray. The CACTD (150-231) comprises 310-helix (150-152; green), and four α-helices: H8 (161-173; gray), H9 (179-192; orange), H10 (196-205; blue), and H11 (211-217; pink). The CANTD and CACTD are connected with a flexible linker (146-149). (B) Each crystallographic asymmetric unit comprises a single native CA molecule (shown in surface view representation; pink CANTD, red CACTD). Application of 6-fold crystallographic symmetry generates the CA hexagonal lattice. (C) The six CA subunits in a hexamer are related by 6-fold crystallographic symmetry (yellow hexagon); CA subunits from neighboring hexamers are related by 2-fold (orange ovals) and 3-fold (pink triangles) crystallographic symmetry, shown at the inter-hexamer interfaces. (D) Orthogonal views of three native CA hexamers colored as in A. The hexamers are stabilized by interactions at the 6-fold (brown β-hairpin, yellow H1, black H2, and purple H3), 2-fold (green 310 and orange H9), and 3-fold interfaces (blue H10 and pink H11). (E) Inter-hexamer interactions at the 2-fold interface. Interpretable electron density is now observed for all residues at the 2-fold interface of CA (2.4 Å; 2Fo–Fc; σ=1.2) including residues 176-187, which were previously disordered in crosslinked hexamer structures. (F) Summary of X-ray data.

The inter-hexamer interactions at the crystallographic 2-fold interface are clearly defined in the CA structure through interpretable electron density (Fig. 1E). The observed interactions involve multiple residues, including S149, L151, S178, E180, V1181, W184, M185, L189, and Q192, as well as water molecules (Fig. 2A). These contacts are reminiscent of, but different than those in crystal or NMR structures of isolated CACTD domains (fig. S2A, table S2) (16, 25). They are also significantly different than those in the original crosslinked hexameric (CAXL, PDB ID: 3H47) (fig. S2B, table S2) and recent related CA structures that contain W184A and M185A mutations in helix H9 at the dimerization interface (1, 18, 19).

Fig. 2. Inter-hexamer interactions at the 2-fold and 3-fold interfaces.

Stereo views of CACTD regions that are related by 2-fold (A and C) or 3-fold symmetry (B and D) from CA (A and B), and dCA (C and D). The 2-fold interface comprises helices H9 and 310 in A and C. The 3-fold interface comprises helices H10 and H11 in B and D. Ordered water molecules (spheres) at the 2-fold (A) and 3-fold (B) interfaces of CA are modeled in 2.4 Å simulated annealing omit Fo–Fc electron density maps at σ=2.5 (green mesh). B-factors of refined waters were between 30-50 Å2 and matched well with those of interacting atoms from S149, E175, Q176, W184, I201 and A204. Helices are shown in cartoon representation; black dashed lines between residues (in sticks) indicate that they are within ~4 Å. No water molecules are present at the 2-fold and 3-fold of dCA (C and D).

Inter-hexamer interactions between pairs of helices H10 and H11 at the 3-fold have been reported in cryo-EM studies enhanced with molecular modeling (2). The higher resolution of the CA structure now reveals the details of these contacts (Fig. 2B, table S3). Previous studies proposed that the inter-hexamer interactions are hydrophobic in nature (2, 25). However, the CA structure highlights an additional hydrophilic component that is based on water-mediated interactions at both the 2-fold and 3-fold interfaces (Fig. 2, A and B). These water molecules engage in hydrogen bond interactions with either the side chains of highly conserved residues (S149, E175, W184 at the 2-fold), or main chain carbonyl groups (Q176 at the 2-fold; I201, A204 at the 3-fold) (Fig. 2, A and B). As a result, the closest distance between subunit residues at the 3-fold interface of CA is ~6 Å compared to up to ~15 Å in CAXL (as measured between the A204 carbonyl and its symmetry related mates) (fig. S3A and C). Water molecules at the inter-hexamer interface contribute to the stabilization of the capsid. Out of 450 assigned water molecules per CA hexamer in CA (75 per CA monomer), 30 are at the 2-fold and the 3-fold inter-hexamer interfaces (3 waters for each of the six 2-folds and 2 waters for each six 3-folds per hexamer). As there are ~250 CA hexamers per assembled capsid, thousands of water molecules at the inter-hexamer interfaces are likely to significantly contribute to capsid stability and geometry.

To further investigate the role of this hydration layer in CA structure we used a controlled dehydration protocol (29) that alters the water content of native CA crystals. Dehydration of CA crystals (dCA) resulted in shrinkage of the three dimensions of the unit cell by ~6%, ~6%, and ~3%, respectively (Fig. 1F, table S1). Superposition of the CA and dCA structures reveals significant conformational rearrangement in the relative orientation of the CANTD and CACTD domains, imparted by a hinge-like motion of the rigid bodies using the linker region as a pivot point (fig S4). These changes correlate with significant packing differences at the 2-fold and 3-fold (Fig. 2A vs. 2C, 2B vs. 2D, and fig. S3A vs. S3B). Hence, the hexamers of dCA (fig. S3B) arrange more tightly against each other (the closest distance ~3 Å as measured between residues A204 and L205 at the 3-fold interface) than those of CAXL (fig. S3C) and CA (fig. S5A) creating up to 22 and 15 new molecular contacts in the 2-fold and 3-fold of dCA (tables S2-S3). Calculations of solvent accessible area reveal that dCA has ~150% and ~200% more buried surface than CA and CAXL at the 2-fold, and ~400% more buried surface than CA at the 3-fold interface (table S4). The experimentally observed interactions at the 3-fold are between K203–T216, K203–A217 (involving main-chain atoms), and A204–L205, G206–T216, and P207–E213 (involving side-chain atoms) (table S3, Fig. 2D). Sequence alignment (fig. S5) of residues at the 2-fold and 3-fold shows that almost all of these are entirely conserved among HIV-1 subtypes (205, 206, 213, and 216; 207 is highly conserved). Consistent with our data, substitutions of A204 result in non-infectious virions with unstable or abnormal cores (2, 7). In addition, an extensive body of mutagenesis studies also confirms the importance of the observed residues as their substitution may lead to total loss of infectivity, defects in core morphology and stability, and abrogation of viral DNA synthesis (tables S2 and S3) (1, 6-11, 26, 30).

In addition to these inter-hexamer differences we also identify significant variations in the CANTD-CANTD and CANTD-CACTD intra-hexamer contacts (table S5). These involve changes in hydrogen bond networks, as well as water-mediated and hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3A). Extensive variations in the CANTD-CANTD and CANTD-CACTD intra-hexamer contacts are also observed in the crystal structure of the Bovine Leukemia Virus (BLV) CA hexamer (Obal et al.), supporting the notion that variability in these interactions is a common feature among multiple retroviruses.

Fig. 3. Changes at the intra-hexamer interfaces.

(A) Stereo view of intra-hexamer CANTD-CANTD and CANTD-CACTD inter-subunit interfaces. Two neighboring CA subunits are shown as cartoons outlined for clarity (CANTDs in lighter colors than the corresponding CACTDs). Sites of varying interactions among CA, dCA, CAXL, and CAPF74 are marked in blue/orange for CANTD-CANTD interfaces or pink/brown for CACTD-CANTD interfaces. (B) Intra-subunit rearrangement linked to changes at the 2-fold interface. Enlarged stereo view of the boxed region shows changes in the position of H9 helices in neighboring subunits (marked with primed symbols). Least squares superposition (residues 143–174, 192–219) of dCA (cyan CANTD, blue CACTD) on CA (pink CANTD, red CACTD). Crystal dehydration results in slight extension of helix H8 (blue arrow), interaction of R143 with main chain E175 carbonyl instead of Q176, and repositioning of helix H9 (black arrow). In dCA, W184' from the H9' helix (light blue for dCA and salmon for CA) forms a hydrogen bond with main chain E175 carbonyl from a neighboring subunit, whereas in CA, W184' interacts with Q176 and side chain of E175 through water-mediated contacts. Moreover, in dCA R143 also interacts with E187' and T188'from the neighboring subunit, thus, becoming a part of the 2-fold interface. Black dashed lines connect residues that interact through hydrogen bonds.

Finally, a significant structural difference between CA and dCA involves key interactions of R143 in CANTD with E175 or Q176 in helix H8 of CACTD within the same subunit (Fig. 3, A and B). The R143-Q176 interaction in CA is replaced with R143-E175 in dCA. This change repositions helix H9, leads to loss of the W184-bound water, and alters the H9-H9 inter-hexamer interactions at the 2-fold (Fig. 3B). Similar alternative interactions of R143 with CACTD residues were also observed in engineered unliganded (PDB ID: 3H4E) or ligand complex structures (PDB ID: 4U0E), crystallized in orthorhombic (1) or hexagonal space groups respectively (18), highlighting its functional importance, which is further supported by virological studies (7, 18).

Collectively, the observed structural changes suggest that this remarkable plasticity may provide opportunities for therapeutic intervention by stabilizing conformations sampled during uncoating and assembly, directing CA to non-productive intermediates, or replacing key waters of the hydration layer at the 2-fold or 3-fold interfaces. Notably, residues at these interfaces are highly conserved among various clades and clinical isolates (7, 9, 31) providing a high genetic fragility that makes CA an appropriate target for antivirals (9).

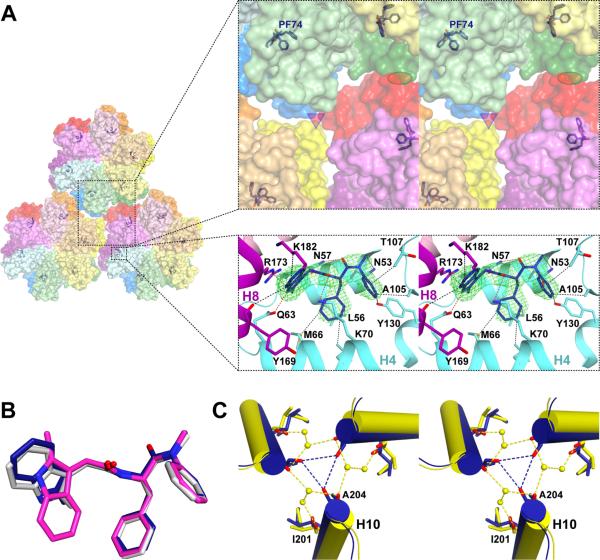

Among more than twenty CA-targeting compounds, PF74 is the most potent CA-targeting antiviral that blocks HIV-1 by affecting multiple steps of the virus life cycle (12-16). In the structure of CANTD-PF74 the ligand occupies a preformed pocket defined by helices H3, H4, H5, and H7 (14). As this binding site is proximal to CACTD, it was proposed that PF74 could interact with CACTD as well. This prediction was confirmed in recent reports (18, 19), explaining how low concentrations of PF74 prevent binding of CPSF6 and nuclear entry (18-23). However, the crystal structures of crosslinked engineered CA did not fully address how PF74 can affect inter-hexamer interactions that affect capsid stability and reverse transcription. Hence, we solved the crystal structure of PF74 in complex with native HIV-1 CA (CAPF74) permitting the detailed description of these interactions.

PF74 binds similarly across two CA monomers in the recent crosslinked structures by Price et al. (CAXL-PF74) (18) and by Bhattacharya et al. (19), as well as in the present CAPF74 structure (Fig. 4A, and fig. S6A) with the indole moiety bound differently than in CANTD-PF74 (Fig. 4B). In addition to the interactions observed in CANTD-PF74 (14), PF74 also interacts with helices H8 and H9 of CACTD from a neighboring subunit in the CAXL-PF74 and CAPF74 (18, 19). In CAXL-PF74, helix H9 mutations W184A and M185A leave part of the H9-H9 2-fold interface disordered and there are also no interactions observed at the neighboring 3-fold region. These interactions are observed in CAPF74. We also observe some differences in the intra-hexamer contacts of PF74 with CACTD residues at or near dimerization helix H9 (Y169 and K182 in CAPF74, vs. Q176, S178, and E179 in CAXL-PF74) (Fig. 4A) (18, 19). Interestingly, PF74 binding results in subtle structural changes at the remote 3-fold and 2-fold regions (Fig. 4C and fig. S6, B and C). These variations are reminiscent of the allosteric changes observed in the complex of CACTD with the CA-targeting antiviral peptide CAI that binds near the CACTD-CACTD interface (PDB ID: 2BUO) (16). Specifically, we observe changes in hydrophobic and water-mediated interactions at the CAPF74 2-fold that affect the buried surface area in this region (tables S2 and S4). Also, changes of the H10 helices of CAPF74 (rmsd ~1 Å with CA) lead to their convergence at the 3-fold, with the distance between A204 main chain oxygen atoms changing from 5.5 Å to 3.6 Å. In turn, this change leads to a displacement of the water molecules seen in CA (Fig. 4C and fig. S6C) and a 150% increase in buried surface area at the 3-fold of CAPF74 (tables S3 and S4). Hence, the CAPF74 structure provides insights into the mechanism by which high concentrations of PF74 change intra- and inter-hexamer interactions and affect the core stability (tables S2, S3, and S5).

Fig. 4. Effects of PF74 on HIV-1 CA structure.

(A) PF74 binding at the CANTD-CACTD interfaces of neighboring subunits within a CA hexamer. Top view of CAPF74 hexamers (side view is shown in fig. S6A). The larger box shows a close-up stereo view of the PF74 binding site in relation to the 3-fold (triangle) and 2-fold (oval) interfaces. CANTDs and the corresponding CACTDs are colored by the same colors (light and dark, respectively). CANTD and a CACTD of a neighboring subunit participate in PF74 binding (magenta and cyan ribbons). Helix H9 is omitted for clarity. PF74 is shown modeled in a 2.7 Å simulated annealing omit map (σ=2.5). (B) PF74 binding geometries in CAPF74 (blue), CAXL-PF74 (PDB ID: 4U0E; PF74 in grey), and CANTD-PF74 (PDB ID: 2XDE; PF74 in magenta) PF74 in 4QNB is almost identical to 4U0E and omitted for clarity. (C) Stereo view of the 3-fold interface of CAPF74 superposed onto CA (aligned on residues 1-219). Helices H10 of CAPF74 and CA are in yellow and blue. Water molecules are shown as yellow spheres in CA; no water molecules were present in CAPF74.

Obal et al. report a structural heterogeneity of CA monomers in the BLV CA hexamers (Obal et al.). Comparison of the related CA, dCA, and CAPF74 structures also suggests a structural variability and conformational plasticity of CA. The variability in inter-hexamer CACTD contacts at the 2-fold and 3-fold in our related structures is likely representative of the heterogeneous arrangement of CA molecules in an asymmetric capsid core. Such structural variability is in agreement with the molecular models of an asymmetric HIV-1 capsid (2, 24).

The nature of CA structural variability goes beyond mere side-chain rearrangement. A key structural determinant important for the stabilization of variable interfaces is likely to be the presence of structured water molecules observed at strategic regions (1), including the 2-fold and 3-fold interfaces (Fig. 2, A and B). This hydration layer could function as an extension of CA structure, contributing to surface complementarity among flexible CA molecules. It is likely to be adaptable and facilitate nearly isoenergetic structural rearrangements that contribute to quasi-equivalent structural variability.

In addition, similar to previous reports (1) we observe changes in the relative orientation of CANTD and CACTD (~10° rotation in fig. S4) that may cause a tilt among neighboring hexamers and contribute to the surface curvature of an authentic capsid. Different inter-hexamer tilt angles would be anticipated at the narrow and broad ends of the capsid. In addition, intra-hexamer interactions between CA monomers from laterally or longitudinally positioned hexamers are likely to differ in tilt, because of differences in surface curvature in the respective directions. Given the asymmetric nature of capsid, it is likely that no two CA molecules are identical in any one HIV-1 capsid core (2, 24). Hence, CA plasticity allows a wide range of conformations that contribute to the structural variability of the HIV-1 asymmetric core.

CA pliability may provide biological and evolutionary benefits to viruses by allowing interactions with multiple host factors. For HIV-1, these include TRIM5α, CPSF6, MxB, cyclophilin, NUP153, and NUP358 (recently reviewed in (32, 33)). Such diverse interactions afford a functional versatility reminiscent of a Swiss Army knife. Moreover, the large variability in subunit distances at the 3-fold region (ranging from ~3 Å to ~15 Å in fig. S3) may affect permeability to deoxynucleoside triphosphates that can have a footprint diameter of ≤10 Å. This may be relevant to the reverse transcription process, although nucleotide trafficking could also be affected by possible occasional imperfections in the malleable capsid core structure. Extensive structural variability may also become an Achilles heel for the virus by providing multiple opportunities for pocket targeting, destabilization of core, or stabilization of non-productive structural intermediates.

Supplementary Material

One Sentence Summary.

X-ray structures of native HIV-1 capsid protein reveal interactions important for uncoating, assembly, and CA-targeting by antivirals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nix of ALS beamline 4.2.2 for assistance with data collection. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. SAD phasing and initial model building were carried out at the workshop entitled “CCP4/APS School in Macromolecular Crystallography: From Data Collection to Structure Refinement and Beyond” at the Argonne National Laboratory in June 2014 (http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/schools/APS-2014/index.php). We also thank all the lecturers of the workshop and the staff of the APS beamline 23 for helpful discussions regarding data collection, processing, refinement and validation strategies. We thank Dr. C. Tang for providing a CA-expressing plasmid. This work was supported in whole or in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AI112417, GM103368, AI076119, AI099284, and AI100890 (SGS).

References

- 1.Pornillos O, et al. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell. 2009;137:1282–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao G, et al. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature. 2013;497:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature. 2011;469:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature09640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshmukh L, et al. Structure and dynamics of full-length HIV-1 capsid protein in solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:16133–16147. doi: 10.1021/ja406246z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du S, et al. Structure of the HIV-1 full-length capsid protein in a conformationally trapped unassembled state induced by small-molecule binding. Journal of molecular biology. 2011;406:371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, et al. The interdomain linker region of HIV-1 capsid protein is a critical determinant of proper core assembly and stability. Virology. 2011;421:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Garrus JE, Sundquist WI. Functional Surfaces of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Capsid Protein. Journal of virology. 2003;77:5439–5450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5439-5450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganser-Pornillos BK, von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Aiken C, Sundquist WI. Assembly Properties of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 CA Protein. Journal of virology. 2004;78:2545–2552. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2545-2552.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rihn SJ, et al. Extreme genetic fragility of the HIV-1 capsid. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003461. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng X, et al. Protease cleavage leads to formation of mature trimer interface in HIV-1 capsid. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002886. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamble TR. Structure of the Carboxyl-Terminal Dimerization Domain of the HIV-1 Capsid Protein. Science. 1997;278:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly BN, et al. Structure of the antiviral assembly inhibitor CAP-1 complex with the HIV-1 CA protein. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;373:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang C, et al. Antiviral inhibition of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Journal of molecular biology. 2003;327:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blair WS, et al. HIV capsid is a tractable target for small molecule therapeutic intervention. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1001220. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curreli F, et al. Virtual screening based identification of novel small-molecule inhibitors targeted to the HIV-1 capsid. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2011;19:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ternois F, Sticht J, Duquerroy S, Krausslich HG, Rey FA. The HIV-1 capsid protein C-terminal domain in complex with a virus assembly inhibitor. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2005;12:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nsmb967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamorte L, et al. Discovery of novel small-molecule HIV-1 replication inhibitors that stabilize capsid complexes. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57:4622–4631. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00985-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AJ, et al. Host Cofactors and Pharmacologic Ligands Share an Essential Interface in HIV-1 Capsid That Is Lost upon Disassembly. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004459. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharya A, et al. Structural basis of HIV-1 capsid recognition by PF74 and CPSF6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014:201419945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419945112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fricke T, Buffone C, Opp S, Valle-Casuso J, Diaz-Griffero F. BI-2 destabilizes HIV-1 cores during infection and Prevents Binding of CPSF6 to the HIV-1 Capsid. Retrovirology. 2014;11 doi: 10.1186/s12977-014-0120-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng K, et al. Quantitative microscopy of functional HIV post-entry complexes reveals association of replication with the viral capsid. eLife. 2014;3:e04114. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi J, Zhou J, Shah VB, Aiken C, Whitby K. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by virus capsid destabilization. Journal of virology. 2011;85:542–549. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01406-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matreyek KA, Yucel SS, Li X, Engelman A. Nucleoporin NUP153 phenylalanine-glycine motifs engage a common binding pocket within the HIV-1 capsid protein to mediate lentiviral infectivity. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003693. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Cheng A, Yeager M. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell. 2007;131:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worthylake DK, Wang H, Yoo S, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Structures of the HIV-1 capsid protein dimerization domain at 2.6 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:86–92. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998007689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartonova V, et al. Residues in the HIV-1 capsid assembly inhibitor binding site are essential for maintaining the assembly-competent quaternary structure of the capsid protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:32024–32033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly BN, et al. Implications for viral capsid assembly from crystal structures of HIV-1 Gag(1-278) and CA(N)(133-278). Biochemistry. 2006;45:11257–11266. doi: 10.1021/bi060927x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gitti RK, et al. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science. 1996;273:231–235. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heras B, Martin JL. Post-crystallization treatments for improving diffraction quality of protein crystals. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:1173–1180. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905019451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joshi A, Nagashima K, Freed EO. Mutation of dileucine-like motifs in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid disrupts virus assembly, gag-gag interactions, gag-membrane binding, and virion maturation. Journal of virology. 2006;80:7939–7951. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00355-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimonte S, Babakir-Mina M, Aquaro S. HIV-1 B-subtype capsid protein: a characterization of amino acid's conservation and its significant association with integrase signatures. Virus genes. 2014;48:429–437. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilditch L, Towers GJ. A model for cofactor use during HIV-1 reverse transcription and nuclear entry. Current opinion in virology. 2014;4:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambrose Z, Aiken C. HIV-1 uncoating: connection to nuclear entry and regulation by host proteins. Virology. 2014;454-455:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanman J, Sexton J, Sakalian M, Prevelige PE., Jr. Kinetic analysis of the role of intersubunit interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein assembly in vitro. Journal of virology. 2002;76:6900–6908. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.6900-6908.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price AJ, et al. CPSF6 defines a conserved capsid interface that modulates HIV-1 replication. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002896. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;Xds.66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution--from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forshey BM, von Schwedler U, Sundquist WI, Aiken C. Formation of a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Core of Optimal Stability Is Crucial for Viral Replication. Journal of virology. 2002;76:5667–5677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5667-5677.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wacharapornin P, Lauhakirti D, Auewarakul P. The effect of capsid mutations on HIV-1 uncoating. Virology. 2007;358:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.del Alamo M, Neira JL, Mateu MG. Thermodynamic dissection of a low affinity protein-protein interface involved in human immunodeficiency virus assembly. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:27923–27929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bocanegra R, Rodriguez-Huete A, Fuertes MA, Del Alamo M, Mateu MG. Molecular recognition in the human immunodeficiency virus capsid and antiviral design. Virus research. 2012;169:388–410. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Byeon IJ, et al. Structural convergence between Cryo-EM and NMR reveals intersubunit interactions critical for HIV-1 capsid function. Cell. 2009;139:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manocheewa S, Swain JV, Lanxon-Cookson E, Rolland M, Mullins JI. Fitness costs of mutations at the HIV-1 capsid hexamerization interface. PloS one. 2013;8:e66065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.