Abstract

The repair of oxidative damage to DNA is essential to avoidance of mutations that lead to cancer. Oxidized DNA bases, such as 8-oxoguanine, are a chief source of these mutations, and the enzyme 8-oxoguanine glycosylase 1 (OGG1) is the chief human enzyme that excises 8-oxoguanine from DNA. The activity of OGG1 has been linked to human inflammation responses and to cancer, and researchers are beginning to search for inhibitors of the enzyme. However, measuring the activity of the enzyme typically requires laborious gel-based measurements of radiolabeled DNAs. Here we report on the design and properties of fluorogenic probes that directly report on OGG1 (and bacterial homologue Fpg) activity in real time as the oxidized base is excised. The probes are short modified DNA oligomers containing fluorescent DNA bases and are designed to utilize the damaged DNA base itself as a fluorescence quencher. Screening of combinations of fluorophores and 8-oxoguanine revealed two fluorophores, pyrene and tCo, that are strongly quenched by the damaged base. We tested 42 potential probe designs containing these fluorophores, and we found an optimized probe OGR1 that yields a 60-fold light-up signal in vitro with OGG1 and Fpg, and can report on oxidative repair activity in mammalian cell lysate and with bacterial cells overexpressing a repair enzyme. Such probes may be useful in quantifying enzyme activity and performing competitive inhibition assays.

Keywords: Fluorescent probes, DNA damage, 8-oxo-guanine, hOGG1, Fpg

Introduction

8-Oxoguanine is an abundant form of oxidative nucleobase damage that is generated by reactive oxygen species resulting from metabolism, ionizing radiation, and chemicals [1–5]. 8-oxoguanine in DNA can adopt a syn conformation and pair with adenine during replication [6,7], ultimately leading to G-to-T mutations [8–10]. This form of nucleobase damage may be the chief molecular source of oxidation-induced mutagenesis in cells [11].

As protection against the mutagenic potential of 8-oxoguanine, cells have evolved multiple ways to repair this lesion. One of the chief eukaryotic 8-oxoguanine repair enzymes is 8-oxoguanine glycosylase 1 (OGG1), which preferentially removes 8-oxoguanine opposite cytosine in double-stranded DNA [12,13]. OGG1 first acts as a glycosylase to excise the 8-oxoguanine base. OGG1 can then act as an AP lyase, performing a β-elimination reaction on the 3′ side of the abasic site to generate an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde at the 3′ terminus [12,13]. However, the lyase activity of OGG1 proceeds slowly and is believed not to be relevant in vivo; it is proposed that the endonuclease APE1 instead cleaves the DNA backbone [14–18]. Formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (Fpg), the functional homolog of OGG1 in E. coli, excises the 8-oxoguanine base and then performs β- and δ- elimination reactions to generate a single nucleotide gap flanked by a 3′ and 5′ phosphate [19–23]. Both OGG1 and Fpg prefer double-stranded DNA substrates, but Fpg can act on single-stranded DNA substrates as well [24,25].

E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and mice engineered to be deficient in Fpg or OGG1 display increased levels of genomic 8-oxoguanine and increased mutations, highlighting the importance of these enzymes in maintaining genome integrity [26–30]. OGG1 mutants with decreased or abolished 8-oxoguanine repair activity have been found in many cancer specimens [31–39], and lower OGG1 activity has been associated with increased cancer risk [40–43].

In addition to its prominent association with genetic mutations leading to malignancies, the repair of 8-oxoguanine has been associated with multiple other important diseases as well. Several OGG1 mutants with decreased or abolished activity have been discovered in Alzheimer's patients [44,45]. Two OGG1 polymorphisms have been associated with rheumatoid arthritis [46], and decreased OGG1 activity has been linked to decreased lung inflammation in allergy models [47]. Moreover, altered levels of OGG1 have been associated with type 2 diabetes [48,49].

A method to easily measure OGG1 activity would help researchers further elucidate these multiple links between OGG1 activity and disease. Such a method would also aid in screening for OGG1 inhibitors or activators as drugs or research tools and in determining disease prognosis from patient samples. Currently, researchers’ ability to quickly and easily study OGG1 activity is hindered by the time-consuming and indirect nature of methods to measure it (e.g., PAGE, comet assay, GC/MS, ELISA, HPLC, and qRT-PCR). For example, one of the most common methods used to measure OGG1 activity, the strand nicking assay, involves radiolabeling an 8-oxoguanine-containing oligonucleotide, incubating it with the sample of interest, and analyzing the sample at various timepoints by gel electrophoresis and radioactivity measurement. This method requires at least a day and only measures OGG1 activity over discrete, predetermined times. More recently developed approaches using fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides [50–53] give a fluorescent readout of OGG1 activity, but these probes rely on backbone cleavage (which is done slowly by OGG1 and is believed to be performed by a separate enzyme in human cells) [14–17] and subsequent DNA dehybridization to generate a fluorescence signal. Thus, the FRET-based probes do not directly measure the excision of 8-oxoguanine but instead rely on downstream events following this excision. Moreover, other DNA-cleaving and DNA-unwinding activities (such as from various nucleases and helicases) may yield a false signal with this design. A split-luciferase sensor that detects 8-oxoguanine in DNA could potentially be used to identify competitive inhibitors of OGG1 or to indirectly measure OGG1 activity [54], but this sensor measures binding of OGG1 to 8-oxoguanine rather than OGG1 enzymatic activity.

Given the need for a more direct and simple measurement of 8-oxoguanine excision activity, we aimed to develop light-up probes that directly measure excision of this oxidized base in real time. By identifying and applying a fluorophore that is strongly quenched by 8-oxoguanine, we have developed a probe that gives a 60-fold fluorescence increase upon reaction with OGG1 or Fpg. Such probes enable direct and specific measurements of OGG1 and Fpg activity in vitro and are expected to be useful in screening the effects of polymorphisms, mutations, post-translational modifications, and competitive inhibitors on 8-oxoguanine repair enzyme activity.

Results and Discussion

Probe Design

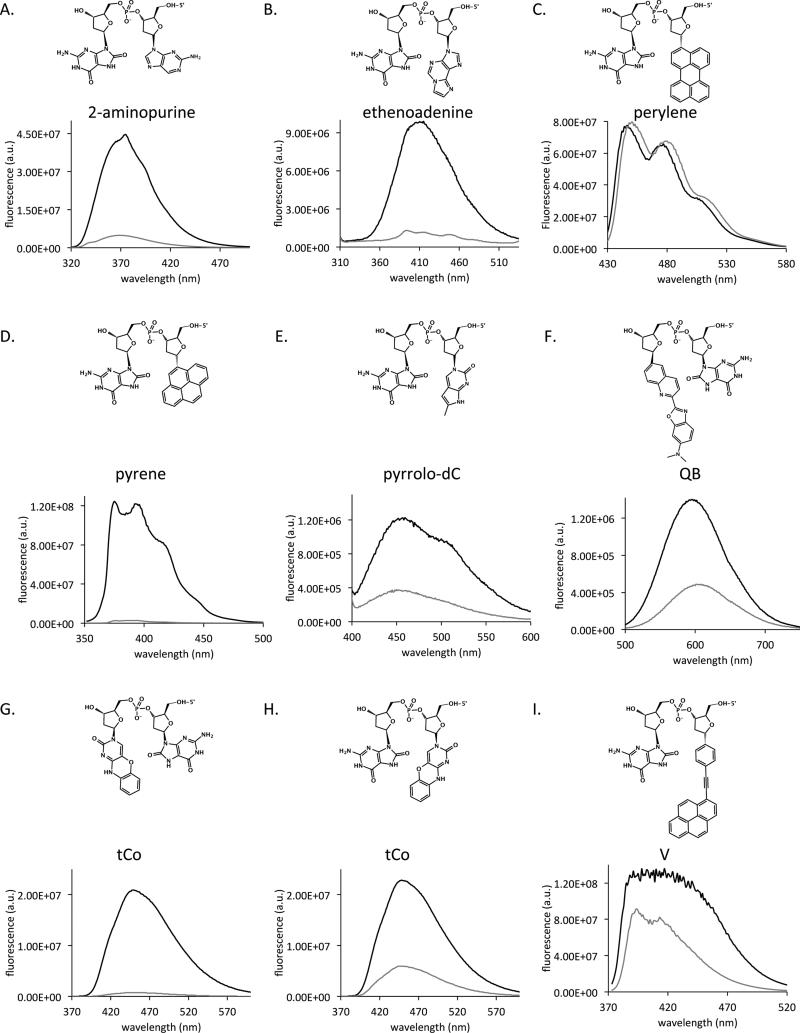

Our probe design relies on a fluorophore that is quenched specifically by 8-oxoguanine, thus becoming emissive following excision of the damaged base. Most desirable would be a fluorophore that is not strongly quenched by native undamaged nucleobases so that a DNA enzyme-binding sequence can be constructed while retaining the possibility of efficient fluorescence emission. Although the “8-oxo-G clamp” is known to be quenched by 8-oxoguanine ,[55–57] this nucleobase analogue pairs with and surrounds the damaged base and may prevent recognition or excision by repair enzymes. To screen for fluorophores that are quenched by 8-oxoguanine, we assembled dinucleotides consisting of a fluorophore deoxyriboside (a nucleoside with a fluorophore replacing the nucleobase) and either 8-oxoguanine or an abasic site mimic (representing the product following 8-oxoguanine excision). See Figure S1 (Supporting Information) for structures of the dye monomors and of a representative dinucleotide. By comparing the fluorescence emission intensities of these 8-oxoguanine-containing dinucleotides with those of the abasic controls, we found that the fluorophores pyrene, 2-aminopurine, ethenoadenine, pyrrolo-dC, and tCo were quenched 2- to 30-fold by 8-oxoguanine, with pyrene and tCo being quenched the most strongly (Figure 1). Pyrene was previously reported to be quenched strongly by thymine and cytosine and moderately by guanine [58]. Similar to a previous report of quenching of tCo by guanine, tCo was more strongly quenched by 8-oxoguanine located on the 5′ side of the fluorophore than on its 3′ side [59]. tCo is reported not to be strongly quenched by the other undamaged nucleobases [59]. In contrast to the above fluorophores, phenylethynylpyrene, perylene, and QB dye were not quenched or were poorly quenched by 8-oxoguanine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fluorescence quenching of varied fluorophores by 8-oxoG. Shown are emission spectra of DNA dinucleotides consisting of a fluorescent nucleoside adjacent to 8-oxo-dG (structure shown) with comparison to no damaged base. Fluorescent bases tested are: 2-aminopurine (A), ethenoadenine (B), perylene (C), pyrene (D), pyrrolo-dC (E), QB (F), tCo (G and H), and V (I) adjacent to 8-oxo-guanine (gray) or to abasic site mimic (black). Dinucleotides in panels F and G have the fluorophore on the 3′ side of the 8-oxoguanine or the abasic site mimic. All other panels have the fluorophore to the 5′ side of the 8-oxoguanine or the abasic site mimic.

Having determined at least two dyes that are strongly quenched by 8-oxoguanine in DNA, we synthesized 42 candidate probes as putative enzymatic substrates that contain 8-oxoguanine and one or more of these fluorophores in place of natural nucleobases (Figure S2). Oligonucleotide designs were guided by the desire to keep probes short in order to aid synthesis yield and enhance likelihood of cellular activity. Some probes were single-stranded, while others were double-stranded with a hairpin design. For the hairpin probes, we chose a highly stabilizing GAA loop [60] to enhance thermal stability in such short sequences. The probes were prepared by standard phosphoramidite chemistry on an automated DNA synthesizer, purified by HPLC or PAGE, and characterized by MALDI-MS to confirm intact incorporation of both the damaged nucleobase and the fluorescent deoxyriboside.

The probes were screened for increases in fluorescence emission following incubation with recombinant human OGG1 or Fpg. Figure S3 shows the degree of signal enhancement achieved with the two enzymes for all the probes.

We observed some trends with pyrene-containing probes, which were tested more generally: First, short double-stranded (hairpin) probes were much better substrates than single-stranded probes (compare OGR2-17 vs. OGR18-42 and OGR1). Second, placing the fluorophore on the 3′ side of 8-oxoguanine appears to be more favorable for enzymatic reaction than placing the fluorophore on the 5′ side (compare OGR19 vs. OGR21). To several of the pyrene-based probes, we added a second fluorophore as a FRET or exciplex partner as a possible strategy for yielding longer-wavelength emission. In these cases, we found that quenching by 8-oxoguanine was less efficient than in the single-fluorophore designs, leading to a high initial fluorescence signal. Many of the pyrene-based probes exhibited low turnover, which may be due to the bulky, hydrophobic fluorophore or the affinity of OGG1 for the abasic site included as pyrene's pairing partner [14,61].

We also observed trends with tCo-containing probes. Adding a second 8-oxoguanine to the other side of tCo did not decrease the initial signal but did decrease the final signal (compare OGR1 vs. OGR36). MALDI analysis (data not shown) indicates that only one 8-oxoguanine is excised, presumably rendering the probe a poor substrate for excision of the second 8-oxoguanine and thus keeping the probe in a semi-quenched state. Increasing the stem or removing the loop did not increase probe performance, indicating that the hairpin structure does not inhibit the enzyme (compare OGR1 vs OGR37, OGR41, and OGR42).

In Vitro Characterization

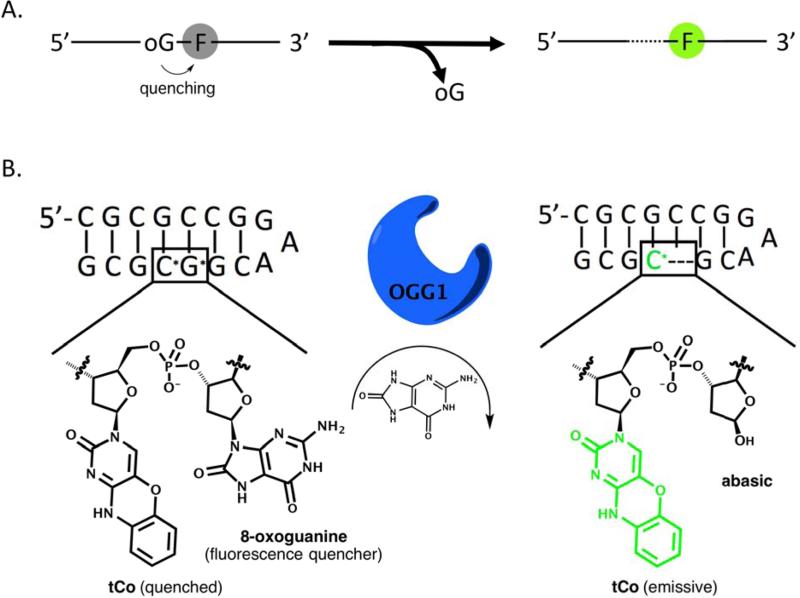

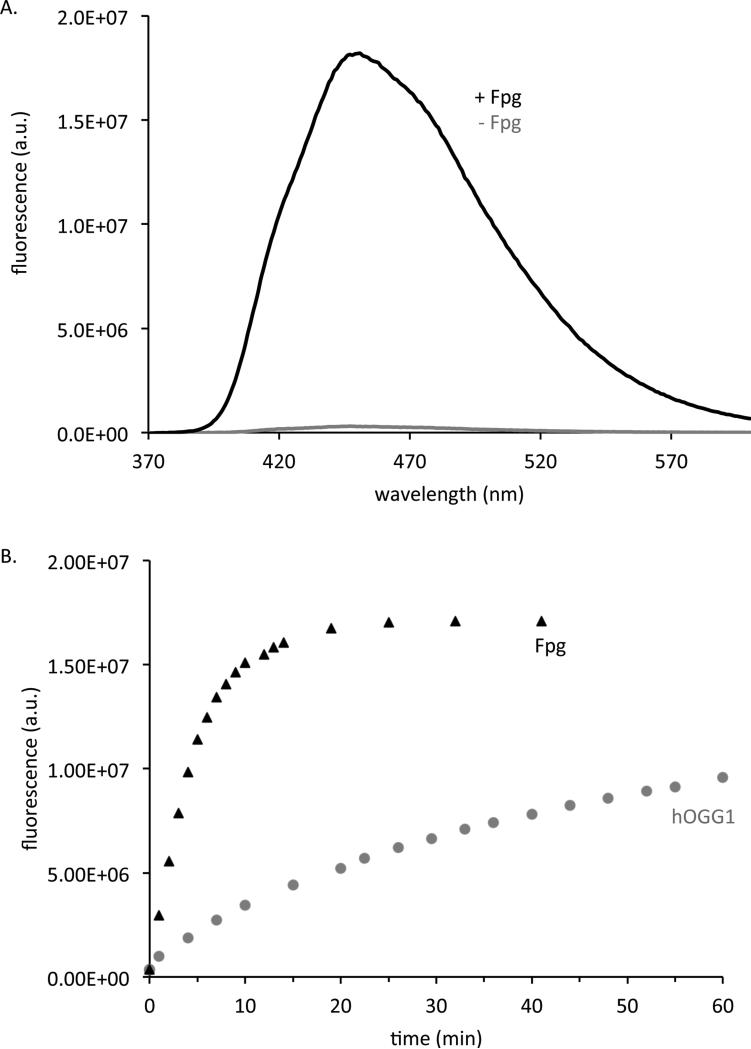

Of the 36 probes tested, the best-performing case was found to be a short hairpin that contains the fluorescent cytosine analog, tCo, opposite guanine and flanked on the 5’ side by 8-oxoguanine and on the 3’ side by guanine (Figure 2). The hairpin structure is stable, with a measured Tm of over 90 °C (Figure S4). The probe, designated OGR1, yields a 60-fold fluorescence increase upon reaction with Fpg or hOGG1 (see emission spectra in Figure 3A.) The quantum yield of the probe (emission maximum 460 nm) was measured to be 0.008 before reaction and 0.170 after completion. The probe reacts more quickly with Fpg than hOGG1, reaching 90% of the final fluorescence in 10 minutes with Fpg versus 3 hours with hOGG1 when using a 1:6 molar ratio of enzyme to substrate (Figure 3B). By measuring initial rates of fluorescence increase as a function of concentration, we determined the apparent KM of probe OGR1 to be 773 ± 120 nM with OGG1 and 14.5 ± 2.9 nM with Fpg. We calculated kcat to be 0.07 min−1 with the OGG1 enzyme and 0.2 min−1 with Fpg. Traditional double stranded DNA substrates have a reported KM of 3.4 nM with hOGG1 and 6 nM with Fpg and a kcat of 300 min−1 with hOGG1 and 3 min−1 with Fpg [24,45].

Figure 2.

A) General scheme of quenching and generation of fluorescence signals with base excision. 8-oxo-guanine is represented as “oG” and the fluorophore is represented as “F”. The fluorophore is quenched by 8-oxo-guanine but becomes emissive following excision of 8-oxo-guanine. B) Schematic drawing of the short hairpin probe OGR1, the best-performing probe in this study, undergoing base excision by OGG1. 8-oxoguanine is represented as G*; tCo (1,3-diaza-2-oxophenoxazine) is represented as C*.

Figure 3.

A) Fluorescence emission of 4 μM probe OGR1 in Fpg reaction buffer at 37 °C without Fpg (gray) and after 25 min with Fpg (black). B) Time course of 4 μM probe OGR1 emission at 465 nm following addition of 658 nM Fpg (black triangles) or hOGG1 (gray circles) at 37 °C. This is a representative curve of n=1.

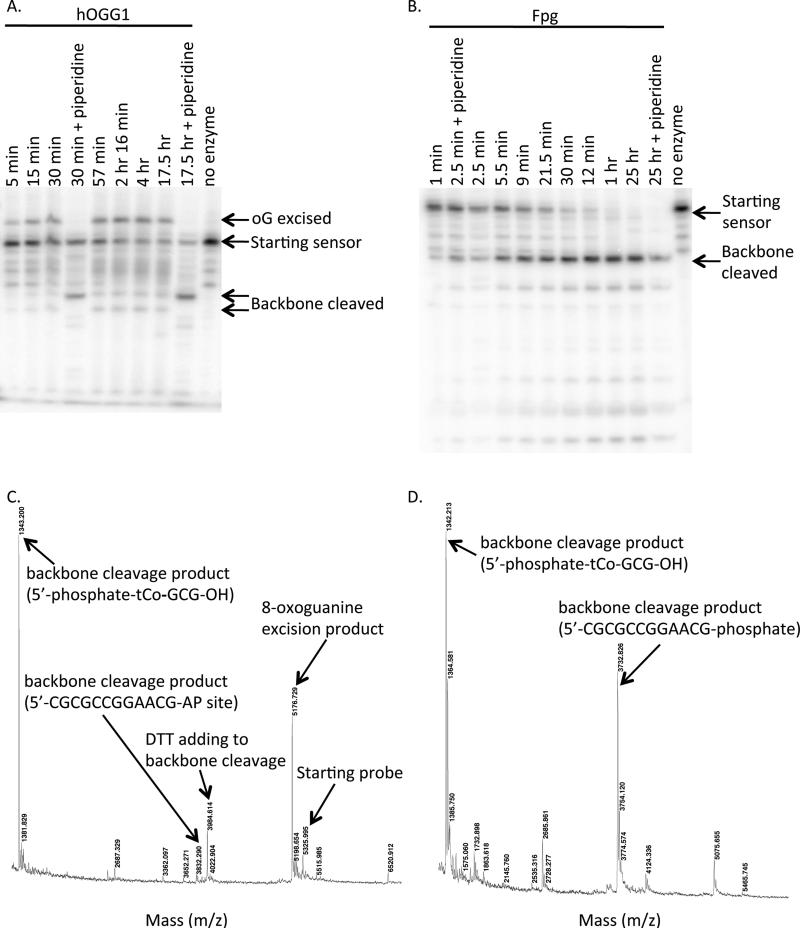

Analysis of reaction products by PAGE and by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identified the probe with 8-oxoguanine excised (for reactions with hOGG1) and the probe following cleavage of the DNA backbone (with phosphates at the new 3′ and 5′ termini when the cleavage occurred with Fpg and with phosphate at the 5′ terminus and an abasic site at the 3′ terminus when the cleavage occurred with hOGG1), which is consistent with the known mechanisms of these enzymes (Figure 4). Thus the analysis confirms enzymatic excision of the fluorescence-quenching damaged base as the mechanism of probe response.

Figure 4.

A and B) PAGE analysis of 4 μM probe OGR1 radiolabeled at the 5′ end with [32P]-phosphate and reacted with 658 nM hOGG1 (A) or Fpg (B) at 37 °C for various times. Piperidine (200 mM, 95 °C, 5 min), which cleaves the DNA backbone at abasic sites, was added to samples as indicated to identify the 8-oxoguanine excision product and the backbone cleavage product. C and D) MALDI mass spectrometry analysis of probe OGR1 following overnight reaction with hOGG1 (C) or Fpg (D).

Performance With Bacterial Cells Overexpressing a Repair Enzyme

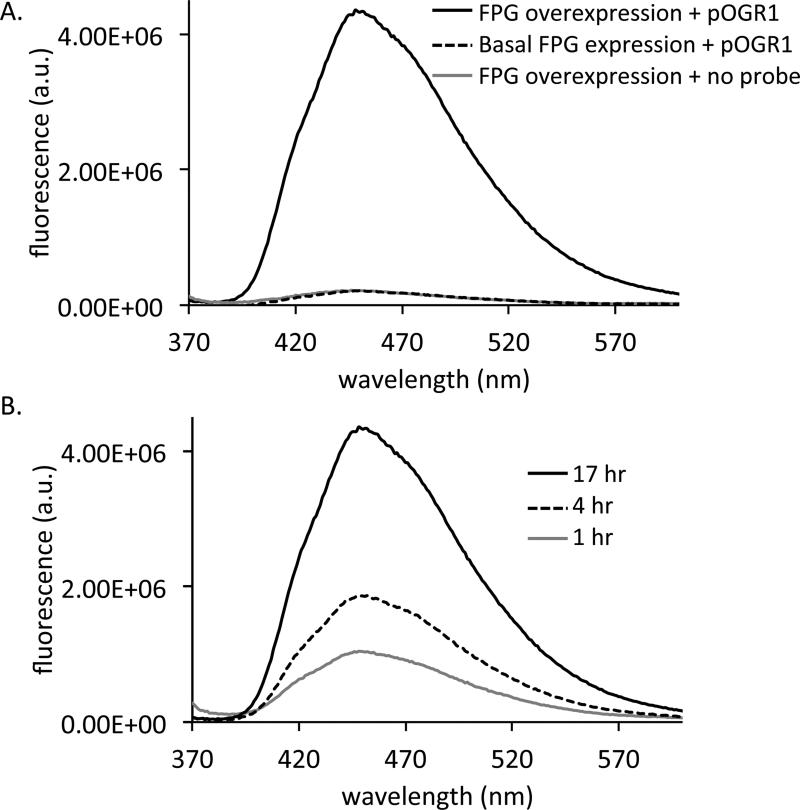

While assays with purified enzyme have general utility, the ability to evaluate enzyme activity without purification, directly in bacterial cells, would save steps in some applications. To test this possibility in a preliminary experiment, we used a nuclease-protected variant of probe OGR1 (containing 2′-O-methyl groups at its termini), designated pOGR1 (Figure S5), in bacterial suspension, with E. coli overexpressing Fpg. Probe pOGR1 incubated with these cells in the presence of 0.25% Triton-X 100 to permeabilize the cells showed an increase in fluorescence as early as 1 hour over cells not overexpressing Fpg or cells lacking probe pOGR1 (Figure 5). Thus, the probe can be used to assess enzymatic activity directly in bacterial cell suspensions.

Figure 5.

Reporting on 8-oxoguanine excision with bacterial cells expressing a repair enzyme. A) E. coli overexpressing Fpg after 17 hr with 4 μM nuclease protected probe pOGR1 and 0.25% triton-X (solid black), overexpressing Fpg after 17 hr with no probe and 0.25% triton-X (gray), or with basal Fpg expression after 17 hr with 4 μM probe and 0.25% triton-X (dashed black). B) E. coli overexpressing Fpg with 4 μM probe and 0.25% triton-X after 1 hr (gray), 4 hr (dashed black), or 17 hr (solid black).

Performance in Mammalian Cell Extracts

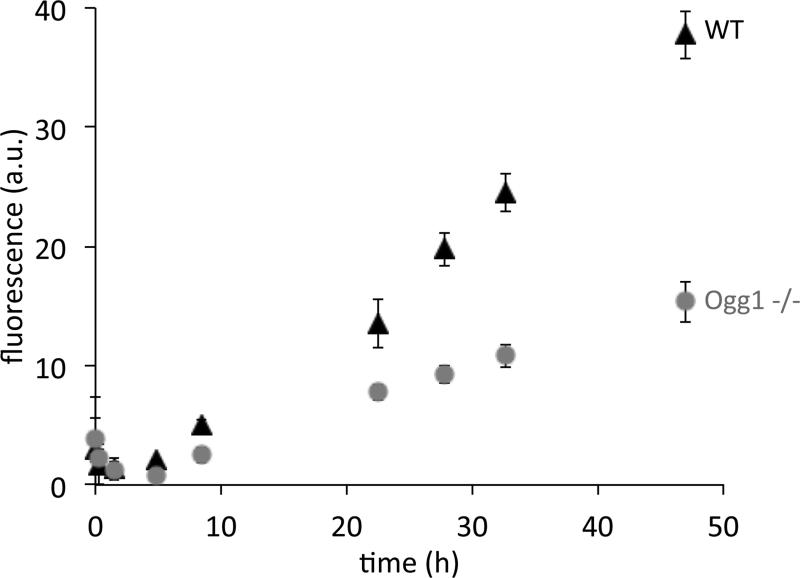

To test whether OGG1 activity could be detected in mammalian cell extracts, we incubated the nuclease-protected probe pOGR1 with extract from WT MEF cells and Ogg1 −/− MEF cells [47] (Figure 6). The WT cell extract yielded a higher fluorescence signal than the Ogg1 −/− cell extract. The signal in the OGG1-positive cells was ca. 2.5-fold greater than in the negative cell line, and the reproducibility was high, giving signals with small error relative to the signal. The difference between the two cell lines was reproducible beyond error limits after 8 hours, and became more readily apparent at longer times. Thus we conclude that the probe can detect OGG1 activity at native levels in mammalian cell extracts.

Figure 6.

Reporting on 8-oxoguanine excision in mammalian cell extracts. 2 μM probe pOGR1 was incubated with 6.7 ng/uL WT (black triangles) or Ogg1 −/− (gray circles) MEF cell extracts at 37 °C. The fluorescence at 460 nm (excitation 355 nm) was measured at the indicated time points. The background fluorescence of cell extract without probe pOGR1 was subtracted. Error bars represent the standard deviation from 5 replicates.

Utility in Detecting Inhibitors of OGG1

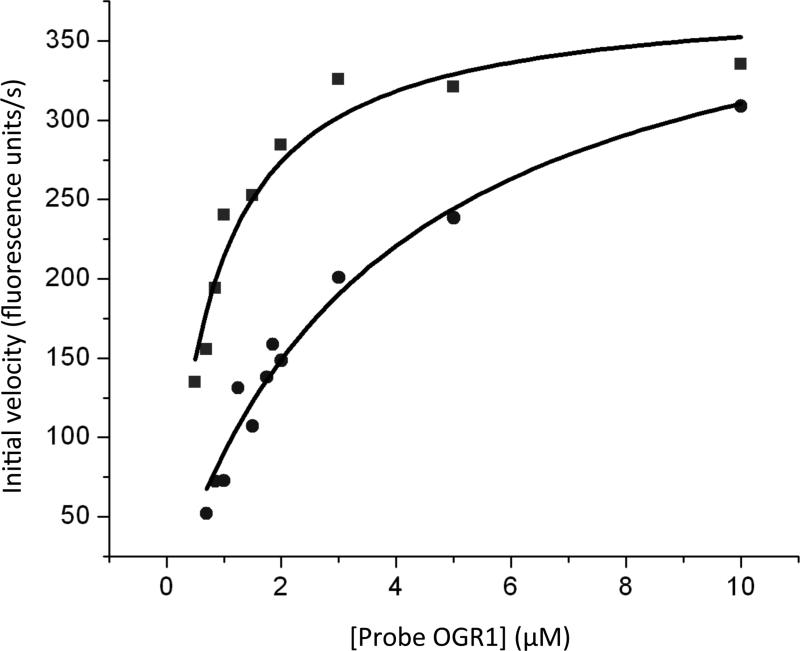

We proceeded to test whether probe OGR1 can be used in reporter assays for competitive inhibitors of OGG1. A previous study identified the unnatural nucleobase 3-Cl-4-F-indole in double-stranded DNA as a strong binder of OGG1 [62]. We synthesized a short stable hairpin containing 3-Cl-4-F-indole (see Figure S6 for the sequence) as a test inhibitor. By measuring the initial rate of fluorescence increase, we determined the apparent KM of probe OGR1 with OGG1 to be 0.77 ± 0.12 μM in the absence of the inhibitor and 3.71 ± 0.52 μM in the presence of the inhibitor (Figure 7). We determined the KI of the inhibitor to be 0.53 μM. Thus probe OGR1 can be used via simple fluorescence measurements to identify and characterize competitive inhibitors of OGG1.

Figure 7.

Michaelis-Menten curves (n = 1) of 0.11 μM hOGG1 with varying concentrations of probe OGR1 and no inhibitor (squares) or 2 μM inhibitor (circles) in hOGG1 reaction buffer at 37 °C. The curves were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation with Origin software (black line).

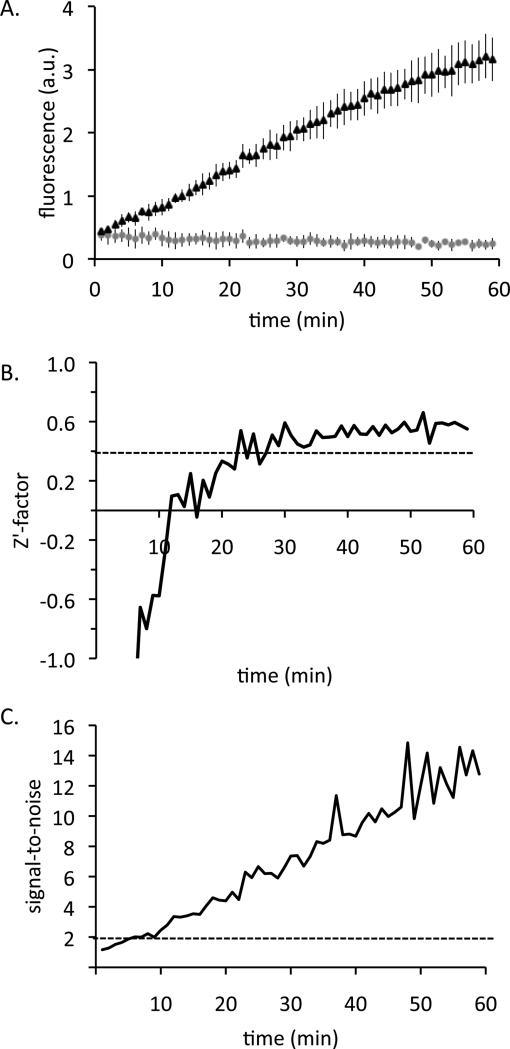

A FRET-based probe has been used to screen for inhibitors of the glycosylase/AP lyase activities of several base excision repair enzymes.[63] To demonstrate the suitability of probe OGR1 in a high-throughput screen, we tested the probe at lower concentrations (0.8 μM probe and 150 nM OGG1) in 384-well plate format and quantified the Z’-factor and signal-to-noise ratio (Figure 8). A Z’-factor greater than 0.4, a signal-to-noise ratio greater than 2, and a coefficient of variance less than 20% are acceptable for use in a high-throughput screen [64]. In our assay, the signal-to-noise ratio passed the cutoff after only 10 min and the Z’-factor passed the cutoff after 25 min, showing that long incubation times are not needed to assess enzyme activity with the probe. Coefficient of variance was less than 20% at all times. Although greater signal intensity can be achieved with probe OGR1 after longer reaction times, it is not necessary for the reaction to go to completion; comparison of the initial rates of fluorescence increase or of the fluorescence obtained after a specified time window would be sufficient. At 0.8 μM probe and a standard reaction volume of 20 mL, one micromole of probe (the scale of a standard DNA synthesis) would be sufficient for approximately 60,000 assays.

Figure 8.

Probe OGR1 in 384-well assay. A) 0.8 μM probe OGR1 was incubated with (black triangles) or without (gray circles) 0.15 μM OGG1 in 20 μL volume. The fluorescence at 460 nm (excitation 355 nm) was measured. Error bars represent the standard deviation from 5 replicates with the probe and 3 replicates without the probe. B) The Z’-factor at each timepoint. Dashed line indicates the cutoff value of 0.4. C) The signal-to-noise ratio at each timepoint. Dashed line indicates the cutoff value of 2.

Conclusion

We have generated a fluorescence turn-on probe of 8-oxoguanine excision that yields a 60-fold increase in fluorescence upon incubation with human OGG1 or bacterial Fpg. In this novel design, 8-oxoguanine acts as a quencher, providing a direct, real-time fluorescence signal corresponding to its excision from DNA. Because of this direct measurement of enzymatic bond breaking, the probe offers an advantage over FRET-based probes, which require downstream events such as DNA backbone cleavage and dehybridization to yield a fluorescent signal, and over other common methods to measure 8-oxoguanine excision, which are much more time-consuming and indirect. Compared with a previously reported FRET sensor of OGG1 [51], our probe displays a higher fluorescence fold change, and the probe's small size relative to previous FRET-based probes makes it easier to synthesize and lowers cost. Furthermore, creation of a highly stable double-stranded hairpin design eliminates the need to carefully anneal the probe and obviates issues of strand stoichiometry. We expect that this and related probes will be useful for screening the effect of polymorphisms, mutations, post-translational modifications, and competitive inhibitors on 8-oxoguanine repair enzyme activity.

The current results illustrate a molecular strategy for direct measurement of DNA base excision by fluorescence, in which the nucleobase to be excised acts as a fluorescence quencher. Specific coupling of the damaged base with a photophysically matched fluorescent nucleobase gives a dark probe that yields a light-up signal in real time as the damaged base is removed. A prior test of this strategy was carried out previously with uracil deoxyglycosidase and combined the uracil (which arises from hydrolytic damage of cytosine) with a fluorescent pyrene nucleoside to report on removal of uracil [65,66]. The current experiments suggest that such a fluorescence-quenching strategy may be more general for measuring base excision repair. Here we have shown this approach can be employed for 8-oxoguanine, by taking advantage of previously unknown quenching of tCo by the damaged base.

We observe that Fpg reacts with probe OGR1 approximately 18 times faster than recombinant human OGG1 does under our conditions (Figure 3B). While OGG1 is known to have a strong preference for double-stranded DNA substrates with 8-oxoguanine paired opposite cytosine [25], Fpg is reported to accept single-stranded substrates as well [24]. The increased activity of Fpg on the new probe relative to OGG1 may reflect Fpg's more flexible substrate requirements. The fact that OGR1 is a significantly less efficient substrate than natural DNA for OGG1 suggests that the extra steric bulk of the fluorescent cytosine derivative tCo may interact unfavorably in the OGG1 active site. Despite this, the probe shows useful levels of activity in vitro and in cell lysates. In the tested cell-derived systems, the signal was slower to develop than with pure enzyme in vitro, which we attribute to inherently low enzyme activity in these systems and to significant cellular background fluorescence at this wavelength. Nevertheless, assays run over 6-12 hours give reproducible signals of this enzyme activity.

Taken together, the results show that the current OGR1 probe design performs well for in vitro assays of enzyme activity with purified enzyme and with cell lysates, and for measurement of activity in bacteria, which is expected to be useful for measurement of inhibition and of the effects of mutations on the enzymes. The probe gives a sufficiently high signal and a low enough variation for use in a high-throughput screen for competitive OGG1 inhibitors. A single DNA synthesis (1 micromole scale) would yield approximately 60,000 assays in 384-well plate format. The fact that all components of probe OGR1 are commercially available makes it widely accessible for researchers.

Experimental Section

Oligonucleotide preparation

Adenine, thymine, guanine, cytosine, 2’-O-methylcytosine, 8-oxoguanine, spacer (tetrahydrofuran), Pyrrolo-dC, 2-aminopurine, ethenoadenine, Dss, and tCo phosphoramidites, 1 μmol columns of dG-CPG, dA-CPG, and Universal Support III, and DNA synthesis reagents were purchased from Glen Research.

5′-DMT 3′-cyanoethyl α-pyrene phosphoramidite [67], 5′-DMT 3′-cyanoethyl α-perylene phosphoramidite [68], 5′-DMT 3′-cyanoethyl α-phenylethynylpyrene phosphoramidite [69], 5′-DMT 3′-cyanoethyl β-N,N-dimethyl-2-(quinolin-2-yl)benzo[d]oxazol-6-amine phosphoramidite (QB) [70], and 5′-DMT 3′-cyanoethyl β-3-chloro-4-fluoro-indole phosphoramidite [62] were prepared according to published methods.

Oligonuceotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 394 DNA/RNA synthesizer with a DMT-off program. Coupling of each monomer used standard 3′-to-5′ cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry with 999 s coupling times for pyrene, perylene, and phenylethynylpyrene, 180 s coupling time for tCo, and 240 s coupling time for other bases. Oligonucleotides OGR37-40 were synthesized by the Stanford Peptide and Nucleic Acid Facility. Oligonuceotides containing 8-oxoguanine were deprotected in concentrated ammonium hydroxide with 0.25 M 2-mercaptoethanol for 17 hr at 55 °C. Dinucleotides containing pyrene, perylene, or phenylethynylpyrene but not 8-oxoguanine were deprotected in 0.05 M potassium carbonate in methanol for 24 hr at room temperature. All other oligonucleotides were deprotected in ammonium hydroxide for 17 hr at room temperature. The deprotected oligonucleotides were dried by speed vac.

Oligonucleotides were purified either by HPLC or PAGE. For purification by HPLC, samples were purified on a Shimadzu Series HPLC with a Phenomenex Jupiter C5 column or a Grace Prosphere C18 column and acetonitrile and 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate buffer pH 7 as eluents. For purification by PAGE, the crude oligonucleotide was loaded onto a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (20% acrylamide/bis solution (19:1), 7.5 M urea, 1X tris borate EDTA buffer). The gel was cooled with a fan during electrophoresis. The gel was visualized by UV absorbance, and the darkest band was excised. A gel extraction was performed in 0.2 M NaCl and 0.25 M 2-mercaptoethanol overnight at 4 °C with shaking. The sample was dialyzed at 4 °C, filtered, dried by speed vac, and resuspended in water.

Probe concentration was determined using fluorophore absorbance (pyrene ε342 = 39,000 M−1cm−1 [67], perylene ε440 = 39,200 M−1cm−1 [68], 2-aminopurine ε260 = 1,000 M−1cm−1 [71], ethenoadenine ε260 = 4,800 M−1cm−1 [72], pyrrolo-dC ε345 = 3,700 M−1cm−1 [73], Dss ε380 = 31,000 M−1cm−1 [74], tCo ε360 = 9,000 M−1cm−1 [59], phenylethynylpyrene ε363 = 67,000 M−1cm−1 [69], and 3-Cl-4-F-indole ε260 = 13,700 M−1cm−1) [62]. The QB extinction coefficient was calculated to be 22,400 M−1cm−1 according the Beer-Lambert Law by measuring the absorbances of known concentrations of the QB diol in methanol. For oligonucleotides with multiple nucleobases or fluorophores absorbing at the specified extinction coefficient wavelength, the extinction coefficient was calculated as the sum of the extinction coefficients of each nucleobase or fluorophore in the oligonucleotide.

Oligonucleotide identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry performed at the Stanford Peptide and Nucleic Acid Facility. See Table S1 for the calculated and found masses. Samples were stored at −20 °C.

Fluorescence analysis of in vitro enzymatic activity

Fpg, hOGG1, Fpg reaction buffer (NEB buffer 1: 10 mM Bis-Tris-Propane-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.0 at 25 °C), hOGG1 reaction buffer (NEB buffer 4: 50 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Tris-acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.9 at 25 °C), and BSA (10 mg/mL) were purchased from New England Biolabs.

The emission spectra were obtained with a Jobin Yvon-Spex Fluorolog 3 spectrophotometer by exciting the samples at the fluorophore's excitation maximum (pyrene 342 nm, perylene 440 nm, 2-aminopurine 303 nm, ethenoadenine 276 nm, pyrrolo-dC 347 nm, Dss 380 nm, tCo 360 nm, phenylethynylpyrene 363 nm, and QB 400 nm) and measuring the emission starting at 10 nm above the excitation wavelength with a step size of 1 nm.

Samples of Fpg or hOGG1 reaction buffer, 100 μg/mL BSA, and 4 μM probes were prepared in water in a quartz cuvette. The fluorescence emission spectrum was measured before addition of probe to determine buffer fluorescence. The fluorescence emission spectrum was measured after addition of probe following 0 and 10 min of incubation at 37 °C to confirm that the fluorescence was stable upon heating. For OGR1 studies, 658 nM of Fpg or hOGG1 was added. For probe screening, 833 nM of Fpg or 658 nM of hOGG1 was added. The fluorescent emission spectrum was measured at timepoints following addition of enzyme. The sample was incubated at 37 °C during and between measurements.

PAGE analysis of in vitro enzymatic activity

Probes were labeled at the 5′ end with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen) and [γ-32P] ATP (PerkinElmer) and purified by ethanol precipitation as previously described [75]. Fpg or hOGG1 reaction buffer, 100 μg/mL BSA, 4 μM unlabeled probe, 0.05 μM labeled probe, and 658 nM Fpg or hOGG1 were mixed and incubated at 37 °C. At indicated timepoints, 10 μL aliquots were removed. Non-piperidine-treated aliquots were mixed with 10 μL loading buffer (25 mM EDTA, 95% formamide, 0.1 % bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol). Samples to be further reacted with piperidine were mixed with 2 μL of a 1:10 dilution of piperidine in water for 5 min at 90 °C and then mixed with 10 μL loading buffer (25 mM EDTA, 95% formamide, 0.1 % bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol). The samples were frozen for up to 24 hours before PAGE analysis. 10 μL of each sample was loaded onto a 20% denaturaing analytical PAGE gel (20% acrylamide/bis solution (19:1), 7.5 M urea, 1X tris borate EDTA buffer) and electrophoresed. The gel was exposed overnight on a Molecular Dynamics phosphor screen and imaged on a GE Typhoon 9410 gel imager.

MALDI analysis of enzymatic activity

Samples were prepared as done for the fluorescence assays. An aliquot was submitted to the Stanford Peptide and Nucleic Acid Facility for zip-tip clean up and MALDI-TOF analysis. The samples were analyzed in HPA matrix in linear negative mode.

Quantum yield measurements

Quinine sulfate was used as a fluorescence quantum yield standard [76]. Quinine sulfate was diluted in 0.1 M H2SO4 and the probes were diluted in water to an absorbance of 0.04-0.05 at 350 nm. For the reacted probes, the absorbance of protein and buffer was subtracted from the absorbance of the sample. The absorbance was measured at 350 nm on a Varian Cary 100 Bio UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The fluorescence emission spectrum was measured a Jobin Yvon-Spex Fluorolog 3 spectrophotometer by exciting the samples at 350 nm and measuring the emission from 360-680 nm with a step of 1 nm. Quantum yield was calculated according to: Φsample = (Φstandard)(Isample/Istandard)(Astandard/Asample)(n2sample/n2standard), where Φ is quantum yield, I is the fluorescence emission over 360-680 nm, A is the absorbance at 350 nm, and n is the refractive index of the solvent.

E. coli methods

To test the OGR1 probe design in bacterial cell solutions, we added 2′-O-methyl monomers for protection at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the probe to generate probe pOGR1. The quantum yield of quenched probe pOGR1 was measured to be 0.004-0.005, comparable to the darkness of probe OGR1 (quantum yield 0.008). As a control we synthesized an unquenched probe containing guanine instead of 8-oxoguanine (designated G-OGR1) that has a quantum yield of 0.08.

One Shot BL21(DE3) E. coli cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with pKK223.3-WT Fpg plasmid (a gift from S. S. David (University of California-Davis) [77]) following the protocol recommended by Invitrogen. A single colony was picked and cultured overnight at 30 °C in LB containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin. The culture was diluted in LB containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.4. 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-galactopyranoside (IPTG) was added, and the culture was grown for 3 or 24 hr at 30 °C. The cells were washed 1 time in PBS by centrifuging at 5000 g at 4 °C for 5 min and resuspended in Fpg reaction buffer. The cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.6 in Fpg reaction buffer. Triton-X 100 was added to 0.25% and probe was added to 4 μM. Samples were incubated with shaking at 37 °C for 1, 4, or 17 hr. Samples were diluted 1:10 in water and their fluorescence emission following excitation at 360 nm was measured on a Jobin Yvon-Spex Fluorolog 3 spectrophotometer.

Mammalian Cell Extracts

Ogg1 −/− MEF cells were provided by Dr. Istvan Boldogh (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston). [47] Ogg1 −/− and WT MEF cells were grown in 3:1 DMEM:F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To obtain cell extract, the protocol by Folco et al. [78] was followed with a few changes: The cells were collected by trypsinization at room temperature instead of scraping. Roche complete mini EDTA-free tablets were used instead of PMSF. The cells were lysed by passing 10-15 times through a 21 gauge needle and 5-10 times through a 16 gauge needle instead of through a Dounce homogenizer. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay.

Equal amounts (6.7 ng/uL) of WT and Ogg1 −/− MEF cell extract were incubated with 2 μM probe pOGR1 and an additional 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C in 80 μL reaction volumes in a black 384-well plate. Fluorescence was measured at 460 nm following excitation at 355 nm on a Thermo Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence plate reader.

Melting temperature measurements

Samples containing 4 μM probe OGR1 in Fpg or hOGG1 reaction buffer reaction buffer were prepared in stoppered 1 cm-path length quartz cells. A Varian Cary 100 UV–vis spectrophotometer equipped with a thermoprogrammer was used to measure the absorbance of the samples at 260 nm while the temperature was changed from 25 to 99 °C and from 99 to 25 °C a rate of 1 °C/min. Due to the high melting temperature of probe OGR1 and the lack of absorbance plateau in the high temperature range, MeltWin software could not be used to determine the melting temperature. Melting temperatures were determined by visual inspection of the melting curve and by approximation of the first derivative of the melting curve.

Measurement of kinetic parameters

Michaelis Menten curves for hOGG1 with and without the inhibitor were generated by preincubating 0.11 μM hOGG1 with either no inhibitor or 2 μM inhibitor in hOGG1 reaction buffer and 100 μg/mL BSA at 37 °C for 5 min, and then adding probe OGR1 (0.5-10 μM) and measuring the initial velocity at 37 °C. The initial velocity was determined by measuring the rate of fluorescence increase at 460 nm over the first 10 minutes of the reaction, during which the fluorescence increase was linear.

Michaelis Menten curves for Fpg were generated by incubating probe OGR1 (0.03-0.3 μM) with 6 nM Fpg in Fpg reaction buffer and 100 μg/mL BSA at 37 °C and measuring the initial velocity at 37 °C. The initial velocity was determined by measuring the rate of fluorescence increase at 460 nm over the first 6 minutes of the reaction, during which the fluorescence increase was linear.

The curves were fit in Origin using the Hill fit with n=1 (yielding the Michaelis-Menten equation) to determine KM and Vmax. The dissociation constant, KI, of the hOGG1 inhibitor was calculated from the apparent KM's of the fit by KM, inhibitor = KM, no inhibitor(1 + ([I]/KI)) [79]

To calculate kcat, we made a calibration curve to convert fluorescence units to amount of product by incubating known concentrations of probe with excess Fpg and measuring the fluorescence increase after the fluorescence signal plateaued. Vmax was converted from fluorescence units/s to μM product/s using the resulting calibration curve. kcat was calculated by kcat = Vmax/[enzyme].

384-well assay

Probe OGR1 (0.8 μM) and hOGG1 (150 nM) in hOGG1 reaction buffer and 100 μg/mL BSA were incubated at 37 °C in 20 μL reaction volumes in a black 384-well plate. Fluorescence was measured at 460 nm following excitation at 355 nm on a Thermo Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorescence plate reader. The signal to noise ratio was calculated by dividing the signal of probe OGR1 incubated with OGG1 by the signal of probe OGR1 incubated without OGG1. The coefficient of variance was calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the average signal intensity at that timepoint. Z’-factor was calculated by:

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Philip Yuen and Prof. Sheila David (University of California-Davis) for providing a plasmid encoding Fpg. We thank Dr. Istvan Boldogh (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston) for providing Ogg1 −/− MEF cells.

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health [GM067201]; and the National Science Foundation [graduate fellowship to S.K.E.]. Funding for the open access charge was provided by Stanford University.

References

- 1.Kasai H, Nishimura S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2137–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.4.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames BN, Gold LS. Mutat. Res. 250:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90157-j. n.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasai H, Nishimura S, Kurokawa Y, Hayashi Y. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:1959–61. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.12.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasai H, Nishimura S. Environ. Health Perspect. 1986;67:111–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8667111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiala ES, Conaway CC, Mathis JE. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5518–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouchakdjian M, Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Eisenberg M, Johnson F, Grollman AP, Patel DJ. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1403–1412. doi: 10.1021/bi00219a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAuley-Hecht KE, Leonard GA, Gibson NJ, Thomson JB, Watson WP, Hunter WN, Brown T. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10266–10270. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng KC, Cahill DS, Kasai H, Nishimura S, Loeb LA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:166–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Nature. 1991;349:431–4. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood ML, Dizdaroglu M, Gajewski E, Essigmann JM. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7024–32. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bont R, van Larebeke N. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:169–85. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zharkov DO, Rosenquist TA, Gerchman SE, Grollman AP. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28607–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girard PM, Guibourt N, Boiteux S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3204–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.16.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill JW, Hazra TK, Izumi T, Mitra S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:430–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidal AE, Hickson ID, Boiteux S, Radicella JP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1285–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saitoh T, Shinmura K, Yamaguchi S, Tani M, Seki S, Murakami H, Nojima Y, Yokota J. Mutat. Res. 2001;486:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidorenko VS, Nevinsky GA, Zharkov DO. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalhus B, Forsbring M, Helle IH, Vik ES, Forstrøm RJ, Backe PH, Alseth I, Bjørås M. Structure. 2011;19:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun B, Latham KA, Dodson ML, Lloyd RS. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:19501–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailly V, Verly WG, O'Connor T, Laval J. Biochem. J. 1989;262:581–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2620581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connor TR, Laval J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:5222–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graves RJ, Felzenszwalb I, Laval J, O'Connor TR. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:14429–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhagwat M, Gerlt JA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:659–65. doi: 10.1021/bi9522662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishchenko AA, Bulychev NV, Maksakova GA, Johnson F, Nevinsky GA. IUBMB Life. 1999;48:613–618. doi: 10.1080/713803570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dou H, Mitra S, Hazra TK. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49679–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minowa O, Arai T, Hirano M, Monden Y, Nakai S, Fukuda M, Itoh M, Takano H, Hippou Y, Aburatani H, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:4156–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050404497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klungland A, Rosewell I, Hollenbach S, Larsen E, Daly G, Epe B, Seeberg E, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:13300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabrera M, Nghiem Y, Miller JH. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:5405–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5405-5407.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas D, Scot AD, Barbey R, Padula M, Boiteux S. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997;254:171–8. doi: 10.1007/s004380050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Furuichi M, Xu P, Tsuzuki T, Sekiguchi M, Nakabeppu Y. Cancer Res. 2003;63:902–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speina E, Arczewska KD, Gackowski D, Zielińska M, Siomek A, Kowalewski J, Oliński R, Tudek B, Kuśmierek JT. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005;97:384–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevillard S, Radicella JP, Levalois C, Lebeau J, Poupon MF, Oudard S, Dutrillaux B, Boiteux S. Oncogene. 1998;16:3083–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyun JW, Choi JY, Zeng HH, Lee YS, Kim HS, Yoon SH, Chung MH. Oncogene. 2000;19:4476–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyun J-W, Jung Y-C, Kim H-S, Choi E-Y, Kim J-E, Yoon B-H, Yoon S-H, Lee Y-S, Choi J, You H-J, et al. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003;1:290–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Audebert M, Radicella JP, Dizdaroglu M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2672–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Audebert M, Chevillard S, Levalois C, Gyapay G, Vieillefond A, Klijanienko J, Vielh P, El Naggar AK, Oudard S, Boiteux S, et al. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4740–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim I-J, Ku J-L, Kang HC, Park J-H, Yoon K-A, Shin Y, Park H-W, Jang SG, Lim S-K, Han SY, et al. Hum. Genet. 2004;115:498–503. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karihtala P, Kauppila S, Puistola U, Jukkola-Vuorinen A. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106:344–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruner SD, Norman DP, Verdine GL. Nature. 2000;403:859–66. doi: 10.1038/35002510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gackowski D, Speina E, Zielinska M, Kowalewski J, Rozalski R, Siomek A, Paciorek T, Tudek B, Olinski R. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paz-Elizur T, Krupsky M, Blumenstein S, Elinger D, Schechtman E, Livneh Z, Natl J. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1312–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paz-Elizur T, Ben-Yosef R, Elinger D, Vexler A, Krupsky M, Berrebi A, Shani A, Schechtman E, Freedman L, Livneh Z. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11683–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gangwar R, Ahirwar D, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Mutat. Res. 680:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao G, Pan X, Zhu B-B, Zhang Y, Yuan F, Huang J, Lovell MA, Lee MP, Markesbery WR, Li G-M, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2759–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sidorenko VS, Grollman AP, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Zharkov DO. FEBS J. 2009;276:5149–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen S-Y, Wan L, Huang C-M, Huang Y-C, Sheu JJ-C, Lin Y-J, Liu S-P, Lan Y-C, Lai C-H, Lin C-W, et al. Rheumatol. Int. 2012;32:1165–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacsi A, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Szczesny B, Radak Z, Hazra TK, Sur S, Ba X, Boldogh I. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyrberg B, Anachkov KA, Dib SA, Wang-Rodriguez J, Yoon K-H, Levine F. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2002;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simone S, Gorin Y, Velagapudi C, Abboud HE, Habib SL. Diabetes. 2008;57:2626–36. doi: 10.2337/db07-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maksimenko A, Ishchenko AA, Sanz G, Laval J, Elder RH, Saparbaev MK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim Y, Hong IS. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009;30:2149–2151. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mirbahai L, Kershaw RM, Green RM, Hayden RE, Meldrum RA, Hodges NJ. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikiforov TT, Roman S. Anal. Biochem. 2015;477:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furman JL, Mok P-W, Badran AH, Ghosh I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12518–27. doi: 10.1021/ja1116606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakagawa O, Ono S, Li Z, Tsujimoto A, Sasaki S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46:4500–3. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nasr T, Li Z, Nakagawa O, Taniguchi Y, Ono S, Sasaki S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:727–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taniguchi Y, Kawaguchi R, Sasaki S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7272–5. doi: 10.1021/ja200327u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson JN, Cho Y, Tan S, Cuppoletti A, Kool ET. Chembiochem. 2008;9:279–85. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sandin P, Börjesson K, Li H, Mårtensson J, Brown T, Wilhelmsson LM, Albinsson B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:157–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshizawa S, Ueda T, Ishido Y, Miura K, Watanabe K, Hirao I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2217–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matray TJ, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6191–6192. doi: 10.1021/ja9803310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKibbin PL, Kobori A, Taniguchi Y, Kool ET, David SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1653–61. doi: 10.1021/ja208510m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacobs AC, Calkins MJ, Jadhav A, Dorjsuren D, Maloney D, Simeonov A, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, McCullough AK, Lloyd RS. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Entzeroth M, Flotow H, Condron P. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0904s44. Chapter 9, Unit 9.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ono T, Wang S, Koo C-K, Engstrom L, David SS, Kool ET. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:1689–92. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ono T, Edwards SK, Wang S, Jiang W, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ren RX-F, Chaudhuri NC, Paris PL, Rumney S, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7671–7678. doi: 10.1021/ja9612763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao J, Watanabe S, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12748–9. doi: 10.1021/ja046910o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang S, Guo J, Ono T, Kool ET. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:7176–80. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yuen LH, Franzini RM, Wang S, Crisalli P, Singh V, Jiang W, Kool ET. Angew. Chemie. 2014;126:5465–5469. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Evans K, Xu D, Kim Y, Nordlund TM. J. Fluoresc. 1992;2:209–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00865278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Secrist JA, Barrio JR, Leonard NJ, Weber G. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3499–3506. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tinsley RA, Walter NG. RNA. 2006;12:522–9. doi: 10.1261/rna.2165806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kimoto M, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4988–9. doi: 10.1021/ja100806c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sambrook J, Russel D. Mol. Cloning A Lab. Man. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2001. p. 10.17. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lakowicz JR. Princ. Fluoresc. Spectrosc. Springer Books; 2006. p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leipold MD, Muller JG, Burrows CJ, David SS. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14984–14992. doi: 10.1021/bi0017982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Folco EG, Lei H, Hsu JL, Reed R. J. Vis. Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/4140. DOI 10.3791/4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Todhunter JA. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism Part A Initial Rate and Inhibitor Methods. Elsevier; 1979. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.