Abstract

Deployment separation and reunifications are salient contexts that directly impact effective family functioning and parenting for military fathers. Yet, we know very little about determinants of post-deployed father involvement and effective parenting. The present study examined hypothesized risk and protective factors of observed parenting for 282 post-deployed fathers who served in the Army National Guard/Reserves. Pre-intervention data were employed from fathers participating in the After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools (ADAPT) randomized control trial. Parenting practices were obtained from direct observation of father-child interaction and included measures of problem solving, harsh discipline, positive involvement, encouragement, and monitoring. Risk factors included combat exposure, negative life events, months deployed, and PTSD symptoms. Protective factors included education, income, dyadic adjustment, and social support. Results of a structural equation model predicting an effective parenting construct indicated that months deployed, income, and father age were most related to observed parenting, explaining 16% of the variance. We are aware of no other study utilizing direct parent-child observations of father’s parenting skills following overseas deployment. Implications for practice and preventive intervention are discussed.

Keywords: fathers, parenting practices, deployment, risk factors, protective factors

The soldiers of the National Guard and Reserve (NG/R) have been deployed at unparalleled rates during the decade-long conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although deployment is challenging for all military families, evidence indicates that NG/R personnel might face particular concerns related to the stress of deployment and reintegration (Griffith, 2010; Wheeler & Stone, 2010). While the primary mission of active duty military personnel is to provide full-time military defense of the nation, the National Guard have a dual federal-state mission that includes both military support to the community, and combat operations during times of conflict. Some studies have shown that NG/R troops are at greater risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mental health problems than active duty soldiers (Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007; Thomas et al., 2010), due to the demands these “citizen soldiers” face (Griffith, 2010; Griffith & West, 2010). In a study of veterans from the first gulf war NG/R soldiers were more likely to report family disruptions than active duty service members (Vogt, Samper, King, King, & Martin, 2008).

The stress of deployment is not limited to the time when the service member is in theater. Rather, families face a diverse array of stressors from pre-deployment to reintegration (DeVoe & Ross, 2012); the negative effects of deployment-related stress can persist long after the deployed person returns home. In study of returning NG/R soldiers, 69% of parents reported having concerns about child-rearing and getting along with children, while well over half reported feeling that parenting was more stressful after deployment (Khaylis, Polusny, Erbes, Gewirtz, & Rath, 2011). Longitudinal studies of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)/Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) service-members show that mental health concerns may persist for at least 12 months following return (Thomas et al., 2010).

Literature examining the pyschosocial adjustment of children of deployed parents indicates cause for concern. Although children of military service members do not have higher levels of psychopathology than children in civilian families (Jensen, Watanabe, Richters, Cortes, Roper, & Liu, 1995), deployment is associated with increased risk for poor mental health outcomes in children. For example, children of a deployed parent have more emotional difficulties as compared to national averages, and this is especially true for girls (Chandra et al., 2010). Additionally, the length of time that a parent was deployed and the mental health of the non-deployed caregiver are associated with poorer emotional outcomes for children, both during deployment and during reintegration to family life (Chandra et al., 2010; Jensen, Grogan, Xenakis, & Bain, 1989). Furthermore, fathers’ posttraumatic stress symptoms are related to impairments in parenting skills following deployment (Gewirtz, Polusny, DeGarmo, Khaylis, & Erbes, 2010).

The Social Context of Fathering After Deployment

According to Belsky’s process model (1984), effective parenting is multiply determined and affected by contextual factors that include parental functioning. A number of risk factors relative to military families may affect parenting behaviors, and protective factors may buffer those risks. Examining the associations among these factors is especially important to an understanding of fathering in military families, as fathering has been shown to be more influenced by contextual factors than mothering (Doherty, Kouneski, & Erickson, 1998; Pleck, 1997). Little is known about how fathers in NG/R families are affected by stressors, or how they access and utilize parenting support. Indeed, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to examine deployed NG/R fathers’ observed parenting practices in the context of relevant risk and protective factors.

Patterson’s (1982) social interaction learning (SIL) model proposes that negative or coercive interactions between parents and children are the primary mechanism by which adverse family experiences affect children’s well-being. Coercive interactions are negatively-reinforcing parent-child interactions that escalate conflict and negative affect. Contextual stressors such as poverty, and family transitions, are incubators of coercive interactions within families (DeGarmo, Patras, & Eap, 2008). Increases in coercive parenting coupled with decreases in positive parenting practices, such as problem solving, skill encouragement, and positive involvement, predict antisocial behavior in children (Patterson, 2005; Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, 2002). Importantly, these SIL parenting behaviors have shown construct validity for observed fathering behaviors (DeGarmo et al., 2008), predictive validity for growth in observed child behavior (DeGarmo, 2010) and sensitivity to intervention for at-risk fathers (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2007).

Fathering After Deployment: Risk and Protective Factors

Risk factors

Exposure to combat and related wartime events negatively affect both service members and their families (MacLean & Elder Jr, 2007). Posttraumatic stress is a major concern for parents returning from deployment. In a study of Vietnam veterans, symptoms of PTSD were associated with lower parenting satisfaction (Samper, Taft, King, & King, 2004). In a longitudinal study of NG/R soldiers, Gewirtz and colleagues found that increases in PTSD symptoms in the year following return from deployment were associated with greater self-reported impairments in parenting practices (Gewirtz, Polusny, DeGarmo, Khaylis, & Erbes, 2010).

In addition to combat stress and experiences, the length of time that a service member is deployed has been shown to have consequences for both parents and children. Length of deployment is a particular issue for NG/R families, who have routinely faced deployments of 18 months or more (Werber, Harrell, Varda, Hall, & Beckett, 2009). In a 2005 survey of families experiencing deployment, NG/R families reported more stress related to length of deployment than any other military branch (National Military Family Association, 2005).

Deployed NG/R soldiers may face a variety of life stressors upon returning home to resume civilian lives. These can have negative consequences for families, disrupting parenting practices by increasing parents’ irritability, punitiveness, and criticism (Webster-Stratton, 1990). In recent years, calls for research examining the potential benefits of post-deployment parenting interventions that are sensitive to the cultural contexts of military families to support the wellbing of both parents and children in military families have been increasing (Pemberton, Kramer, Borego, & Owen, 2013).

Protective factors relevant to NG/R families

Possessing adequate financial resources can help buffer families from the negative effects of stress (Pleck, 1997). Lack of economic resources has negative consequences for both parents and children (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002; Bor et al., 1997). Furthermore, the relationship between family income and children’s outcomes is mediated through parental emotional distress and compromised parenting practices (Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Kohen, 2002).

Social support can protect the functioning of caregivers and thereby buttress their parenting (Armstrong, Birnie-Lefcovitch, & Ungar, 2005; Campbell & Lee, 1992; Crnic, Greenberg, Ragozin, Robinson, & Basham, 1983). SIL research with at-risk fathers has demonstrated that behavioral and contextual social support is predictive of quality involvement, prosocial and coercive fathering behaviors (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2012; DeGarmo et al., 2008). In the context of deployment, social support for parenting is particularly salient for National Guard and Reserve fathers, whose families are often socially isolated from other military families (Black, 1993). Soldiers’ perceptions of social support following return from deployment may be protective against symptoms of posttraumatic stress (Polusny et al., 2011).

Couple adjustment is another important protective factor for NG/R fathers, given that most returning fathers are partnered. Khaylis and colleagues (2011) found that more than three-fourths of partnered reintegrating NG/R soldiers reported concerns about getting along with their partners. Relationship adjustment is negatively associated with combat stress (Renshaw, Rodrigues, & Jones, 2008) and PTSD in returning NG/R soldiers (Erbes et al., 2011; Gewirtz et al., 2010). However, when couple adjustment is strong, it can be an important protective factor for returning soldiers (Meis, Barry, Kehle, Erbes, & Polusny, 2010).

The Present Study

The goal of the current study was to better understand the contextual correlates of observed parenting practices in reintegrating NG/R fathers. We used observations of fathers’ parenting practices, which, despite some shortcomings (Gardner et al., 2000) are generally accepted as a highly informative method for examining parenting behavior that does not rely on parent’s ability to self-report (Patterson et al., 2010), and because multiple method studies reduce shared method variance (Patterson, 1982). Very few studies have examined parenting among deployed military fathers beyond a focus on single correlates (e.g. parenting and PTSD or couple adjustment). Examining associations among a range of risk and protective factors is important because mothers, fathers, and children all benefit from quality involvement and parenting by fathers (Calzada, Eyberg, Rich, & Querido, 2004).

Our specific hypotheses were:

Hypothesis 1: Post-deployment risk factors including combat exposure, negative life events, months deployed, and PTSD symptoms would be associated with lower levels of effective parenting practices.

Hypothesis 2: Post-deployment protective factors including education, income, dyadic adjustment, and social support would be associated with higher levels of effective parenting practices.

Methods

Design

The current study reports on baseline data gathered from a larger longitudinal prevention study of reintegrating NG/R families. Military families (N=336 families) located in the Midwest, were eligible to participate in the study with four assessments conducted over a two-year period. To be included in the study, families were required to have at least one biological, adoptive, or step-child living with them between the ages of four and twelve (i.e. the target child), and at least one parent who had deployed to the current conflicts (i.e. OIF/OEF). To ensure that parents did not systematically choose the child who they were most or least concerned about during reintegration, the eldest child was selected as the target child during the first wave of the recruitment process, while the youngest child was selected during the remainder of the study. In a few cases, if the eldest or youngest child was not willing or able to participate, selection was based upon parental choice. After the initial assessment (T1), 60% of families were randomly assigned to participate in the treatment group, receiving the facilitator-led ADAPT parenting program, while 40% received services-as-usual (i.e. print, online, and email parenting resources). University institutional review board approval was obtained for the study, and all participants provided informed consent.

Of the 336 families participating in the study, 294 had a father who provided data. Twelve of those 294 men were civilians partnered with deployed women, and were excluded from the sample, leaving 282 men who had deployed at least one time. In this paper we report on the information gathered at baseline (T1) for the 282 deployed fathers in the study.

Participants

As part of the baseline data collection, fathers were asked to report on their race, ethnicity, education, household income, occupation, and deployments. Demographic information about the deployed fathers is found in Table 1. This sample of deployed fathers reported predominantly white (89.4%) racial identity, while 3.5% reported Hispanic ethnicity. Nearly half reported completing at least a Bachelor’s degree. Household incomes were reported by categories, with 71% reporting income in two categories from $40,000 to $119,999. Most fathers (82.6%) were employed full-time. Deployed fathers were predominantly married (87.6%) with mean length of marriage 9.8 years (SD=5.4), and a mean of 2.39 children in the household (SD=.94). The target child’s age ranged from 4 to 13 years old at the time of the baseline assessment, and 53.2% were girls. Most fathers were deployed with the Army National Guard (60.3%), Army Reserves (12.1%), and Air National Guard (9.9%), with a mean of 1.96 deployments (SD=1.14). During these operations, 60.6% of participants were deployed more than once, for an average of 3.25 deployments (SD=1.57). Seventy one percent of participants were deployed for more than 12 months. The total months deployed and time since last deployment are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and Military Characteristics of Deployed ADAPT Fathers (N=282)

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Education Level | Marital Status | ||||

| High school/GED | 23 | 8.2 | Married | 247 | 87.6 |

| Some college | 74 | 26.2 | Divorced | 19 | 6.7 |

| AA degree | 45 | 16.7 | Separated | 8 | 2.8 |

| 4-year college degree | 97 | 34.4 | Never married | 3 | 1.1 |

| Master’s degree | 29 | 10.3 | Not reported | 5 | 1.8 |

| Doctoral or professional degree |

7 | 2.5 | Number of Marriages | ||

| Not reported | 5 | 1.8 | 0 | 8 | 2.8 |

| Occupational Status | 1 | 215 | 76.2 | ||

| Employed full time | 233 | 82.6 | 2 | 49 | 17.4 |

| Employed part time | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 5 | 1.8 |

| Retired | 6 | 2.1 | Not reported | 5 | 1.8 |

| Student | 21 | 7.5 | Military Affiliation | ||

| Unemployed | 16 | 5.6 | Air National Guard | 28 | 9.9 |

| Not reported | 5 | 1.8 | Army National Guard | 170 | 60.3 |

| Ethnicity | Army Reserves | 34 | 12.1 | ||

| Nonhispanic | 252 | 89.4 | Naval Reserves | 10 | 3.5 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 3.5 | Air Force Reserves | 9 | 3.2 |

| Not reported | 20 | 7.1 | Other/Unknown | 31 | 11.1 |

| Race | Number Times Deployed | ||||

| Caucasian/White | 251 | 89.0 | 1 | 110 | 39.0 |

| African-American/Black | 14 | 5.0 | 2 | 107 | 37.9 |

| Asian/Asian-American | 7 | 2.5 | 3 | 48 | 17.0 |

| Multiracial | 6 | 2.1 | 4 or more | 16 | 5.8 |

| Native American/Alaska Native |

1 | 0.4 | Unknown | 1 | 0.4 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island | 1 | 0.4 |

Number of Total Months of All OEF/OIF Deployments |

||

| Unknown | 8 | 2.9 | 6 months or less | 17 | 6.0 |

| Household Income | 7–12 months | 79 | 28.0 | ||

| Less than $39,999 | 30 | 10.6 | 13–18 months | 35 | 12.4 |

| $40,000 – $79,999 | 117 | 41.5 | 19–24 months | 55 | 19.5 |

| $80,000 – $119,999 | 85 | 30.1 | 25–30 months | 27 | 9.6 |

| $120,000 or more | 43 | 15.2 | 31–36 months | 39 | 13.8 |

| Unknown | 7 | 2.5 | 37 months or more | 28 | 10.3 |

| Gender of Target Child | Unknown | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Male | 132 | 46.8 |

Time Since Last Deployment |

||

| Female | 150 | 53.2 | Less than 12 months | 90 | 31.9 |

| Age of Target Child | 12 to 24 months | 87 | 31.2 | ||

| 4–5 | 63 | 22.3 | 25 to 48 months | 37 | 13.1 |

| 6–7 | 58 | 20.6 | More than 48 months | 50 | 17.7 |

| 8–9 | 79 | 28.0 | Unknown | 3 | 1.1 |

| 10–11 | 49 | 17.4 |

OEF Deployed (Afghanistan) |

166 | 58.9 |

| ≥12 | 33 | 11.7 | OIF Deployed (Iraq) | 215 | 76.2 |

Note: OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Procedures

Participants in the study were recruited through numerous methods, including presentations at pre-deployment and reintegration events for NG/R personnel and their spouses, mailings from the local Veteran’s Administration Medical Center to OIF/OEF veterans, media, and word of mouth. Initial participant screening and informed consent took place online, through the study website, unless participants specifically requested this process be accomplished over the phone or in person. Participants who submitted their informed consent were automatically directed to a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant site to complete an online assessment; each participating parent completed a separate assessment. Following this, project staff scheduled an in-home assessment with the family, during which self-report, observational, and physiological data were gathered from parent(s) and the target child. Families were debriefed after the interview for any questions or concerns. Parents were each paid $25 for the online assessment and each family received $50 for completing the baseline in-home assessment; children received a small gift.

Measures

Negative life events

Negative life events were measured with the Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ; (Norbeck, 1984; Sarason, Johnson, & Siegel, 1978). The LEQ is a list of 82 events which respondents rate according to whether the event occurred in the last year, whether it had a good or bad effect, and how strong the effect was (0 = “no effect”, 4 = “great effect”) The LEQ is significantly correlated with other stress-related measures, and the 1-week test-retest reliability was high (.78 – .83; Norbeck, 1984). Because the LEQ produces a count of negative life events rather than a scale, alphas are not reported.

Battle experiences

Battle experiences were measured with the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI; (King, King, Vogt, Knight, & Samper, 2006). The DRRI measures a variety of military events and experiences among military personnel who have been deployed to war zones. This study utilized the two sections of the DRRI focused on battle and post-battle experiences. Each section includes 15 items; examples include: “I or members of my unit received hostile incoming fire,” “I or members of my unit were attacked by terrorists or civilians,” and “I personally witnessed someone from my unit or an ally unit being seriously wounded or killed.” Items are rated “yes” or “no.” The DRRI has been validated with a large occupationally and demographically diverse sample of military personnel deployed to OIF, where the instrument demonstrated criterion-related validity with demonstrated associations with measures of mental and physical health (Vogt, Proctor, King, King, & Vasterling, 2008). Reliability for the combined 30-item measure used in this study was high (α = .94).

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

were measured with the PTSD Checklist (PCL; (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). The PCL is a 17-item questionnaire that measures symptoms of posttraumatic stress as defined by the DSM-IV. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, from “not at all” to “extremely.” Example of items are “Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts or images or a stressful experience,” and “Having difficulty concentrating.” The PCL has been empirically supported with military personnel as a valid and reliable screening instrument for PTSD (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003). Scores are obtained for symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, and arousal, as well as a total symptom severity score which is the sum of all 17 items (α = .95).

Dyadic adjustment

The seven-item version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale-7 (DAS-7; (Spanier, 1976) measured self-reported relationship satisfaction. The DAS consists of six items that measure perceived agreement about major life domains (e.g. spending time together, mutual goals, exchanging ideas, etc.) rated on a 6-point scale (0 = always disagree, 5 = always agree) along with an overall satisfaction item that measures happiness in the relationship rated on a seven-point scale (0 = extremely unhappy, 6 = perfect). The instrument is relevant for both married and cohabiting couples (Hunsley, Best, Lefebvre, & Vito, 2001). The DAS-7 has shown discriminant validity (Sharpley & Rogers, 1984), and good internal consistency (Hunsley et al., 2001). All items were rescaled 1 to 5 and averaged (α = .87).

Social support for parenting

Parenting support was measured with the Parenting Support Index PSI; (DeGarmo & Bryson, 2000; DeGarmo et al., 2008), a 24-item survey utilizing a 5-point Likert rating scale of 0 (not at all/not applicable) to 4 (a great deal). Deployed fathers indicated the parenting social support available to them within four domains: emergency child care (e.g., parent illness), non-emergency child care (e.g., time for fun), practical parenting assistance (e.g., advice, doctor referrals), and financial assistance with parenting (α = .79).

Fathers’ parenting practices

Fathers’ parenting behaviors were measured with five previously validated SIL indicators; (1) problem solving outcome (2) harsh discipline, (3) positive involvement, (4) skill encouragement, and (5) monitoring. Scores were obtained from direct observation of father-child interactions during structured Family Interaction Tasks (FITs). Based upon prior observational studies of parent and child relationships in families with children age 4 to 12, the FITs are ecologically valid, demonstrate construct validity, and sensitivity to change with at-risk families (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Gewirtz, DeGarmo, Plowman, August, & Realmuto, 2009), and at-risk fathers (DeGarmo et al., 2008; Patterson, Forgatch, & DeGarmo, 2010). During the short problem-solving tasks involving current conflict issues, topics were selected separately by parents and children during individual interviews, from the Issues Checklist (Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979), which lists areas of frequent family conflicts (e.g., bedtime, cleaning their room, homework). Immediately after reviewing video footage from each of the interaction tasks, trained coders scored the family interaction tasks using the Coder Impressions system (Forgatch, Knutson, & Mayne, 1992). Inter-rater reliability was assessed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for randomly selected coder teams.

Problem solving outcome was based on a 9-item scale with ratings on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (untrue) to 5 (very true), evaluating the quality of a father and child’s solution, the extent of resolution of the issue, satisfaction at the outcome of the discussion, and the likelihood the family would put this solution to use (α = .87, ICC = .88). Harsh discipline was measure by a 8-item scale with ratings on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always) assessing overly strict, authoritarian, erratic, inconsistent, or haphazard parenting practices (α = .76; ICC = .78). Positive involvement was derived from a 10-item measure with ratings on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Fathers’ warmth, empathy, encouragement, and affection were evaluated (α = .75; ICC = .84). Skill encouragement was assessed by an 8-item scale with ratings on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (untrue) to 5 (very true). Fathers’ ability to promote children’s skill development through encouragement and scaffolding strategies were observed during the family interaction tasks, where the child is given challenging problems and the father is asked to assist (α = .83; ICC = .72). Monitoring was determined by a 4-item scale with ratings on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (untrue) to 5 (very true). The items assessed parents’ supervision of the child and knowledge about their child’s activities on a daily basis, such as “The parent seems to be monitoring what the child is doing when outside adult supervision.” (α = .71; ICC = .74).

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, Sample Size, and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Father Age | --- | |||||||||

| 2. Child Age | .37*** | --- | ||||||||

| 3. Education | .26*** | .07 | --- | |||||||

| 4. Income | .36*** | .11 | .43*** | --- | ||||||

| 5. Months Deployed | −.04 | .09 | −.08 | −.05 | --- | |||||

| 6. Negative Life Events | .07 | .02 | −.18 | −.18** | .11 | --- | ||||

| 7. Combat Stress | .05 | −.02 | .01 | .02 | −.32*** | −.07 | --- | |||

| 8. PTSD | −.12 | −.03 | .10 | −.12* | .08 | .23*** | −.46*** | --- | ||

| 9. Dyadic Adjustment | −.10 | .02 | −.17** | .10 | −.03 | −.28*** | .07 | −.22** | --- | |

| 10. Social Support | −.00 | −.11 | .02 | .13* | −.03 | −.14* | .00 | −.12 | .31*** | --- |

| 11. Problem Solving | .04 | .09 | .10 | .10 | −.07 | .06 | −.02 | .06 | .05 | −.05 |

| 12. Harsh Discipline | −.06 | −.08 | −.08 | −.04 | .04 | −.11 | −.07 | −.02 | −.02 | .12 |

| 13. Positive Involvement | −.04 | −.12* | .15* | .16* | −.12 | .08 | .01 | −.03 | .11 | .00 |

| 14. Skill Encouragement | −.08 | −.17** | .08 | .13* | .05 | .05 | −.05 | −.01 | −.07 | −.04 |

| 15. Monitoring | −.06 | −.06 | .07 | .05 | .05 | .05 | −.00 | −.03 | .01 | −.01 |

| M | 37.40 | 7.99 | 5.18 | 8.57 | 3.81 | 4.69 | 25.21 | 30.20 | 3.50 | 45.12 |

| SD | 6.57 | 2.58 | 1.29 | 3.60 | 1.83 | 5.46 | 3.83 | 12.60 | .65 | 9.87 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||

| 11. Problem Solving | --- | |||||||||

| 12. Harsh Discipline | −.05 | --- | ||||||||

| 13. Positive Involvement | .12 | −.25*** | --- | |||||||

| 14. Skill Encouragement | .00 | −.48*** | −.29*** | --- | ||||||

| 15. Monitoring | −.04 | .24*** | −.17*** | .63*** | --- | |||||

| M | 7.98 | 5.18 | 8.57 | 3.81 | 4.69 | |||||

| SD | 2.57 | 1.28 | 3.60 | 1.83 | 5.46 |

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Analytic Strategy

Hypotheses were tested with path analytic regression techniques using structural equation modeling (SEM) in MPlus7 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998; 2012). Hypotheses were evaluated for just-identified regression models associating measured indicator domains of fathers’ parenting (i.e., problem solving, harsh discipline, positive involvement, encouragement, and monitoring). Main effect hypotheses were tested by regressing parenting behaviors on the hypothesized risk and protective factors. To examine potential moderating effects, block entry hierarchical regression models were conducted with block one entered as centered first order terms and variables in block two entered as centered cross products (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). To test risk and protective factors for effective parenting as a latent construct, a latent variable SEM model was specified with block entry of first order and second order terms. Model fit was evaluated using recommended fit indices (Kline, 2010; McDonald & Ho, 2002) including a chi-square minimization p value above .05, a comparative fit index (CFI) above .95; a chi-square ratio (χ2/df) less than 2.0; and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .08.

Missing data

Patterns of missing data were evaluated for the covariance structure analyzed in the specified SEM analyses. Little’s MCAR chi-square test indicated the data were missing at random/MAR (Little’s χ2 (228) = 231.749, p = .418). Following recommendations for the MAR data mechanism, models were estimated with full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) which uses all available information from the observed data in handling missing data (Enders, 2010; Jelicic, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009). FIML estimates are computed by maximizing the likelihood of a missing value based on observed values in the data.

Results

Risk and Protective Factors for Fathers’ Parenting

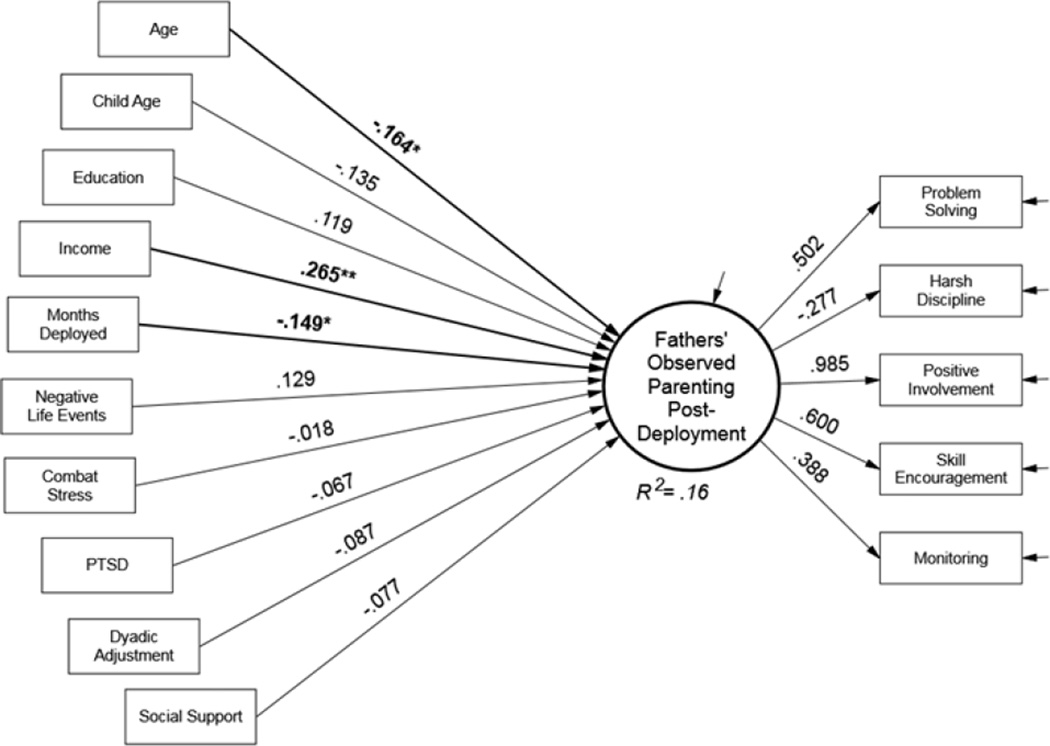

For the primary test of risk and protective factors that are associated with parenting behaviors of post-deployed fathers, we estimated a latent variable SEM model specifying parenting measured as the five core SIL fathering behaviors (DeGarmo, 2010; DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2007). Results are shown in Figure 1 for the SEM path model regressing observed parenting behaviors on the hypothesized first-order risk and protective factors.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Path Model for Risk and Protective Factors Predicting Post-Deployed Fathers’ Observed Parenting Practices. χ2 (45) = 53.96, p = .17, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03; χ2/df = 1.19. **p < .01; *p < .05

The model obtained good fit to the data (χ2 (45) = 53.96, p = .17, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03; χ2/df = 1.19). Although there was some support for Hypotheses 1 and 2, only two of the covariates obtained significant association with fathers’ parenting practices in the multivariate model. Higher levels of income were associated with higher levels of effective parenting (β = .27, p < .01) and more months of deployments were associated with lower levels of effective parenting (β = −.15, p < .05). Parent age was significantly associated with overall parenting such that younger parents showed more effective parenting. We next specified an SEM model that entered second-order cross-product terms to examine potential two-way interactions among risk and protective factors. None of the interactions were associated with the parenting construct. Overall the model explained 16% of the variance in observed parenting behaviors of post-deployed fathers, a large effect size (d = .86).

Risk and Protective Factors for Fathers’ Parenting Domains

We next wanted to examine and test hypotheses for the respective SIL prosocial and coercive parenting indicators separately. Results are shown in Table 3 in the form of standardized beta coefficients. Similarly, evidence was mixed for the independent multivariate impact of risk and protective factors. In total, the risk and protective factors were associated with prosocial parenting domains of positive involvement and skill encouragement. The models explained 15% and 14% of the variance, respectively, representing large effects (d = .84 and .80). There were no first order correlations with harsh coercive discipline and monitoring, and one association with problem solving. Model 1 demonstrates that higher levels of education were associated with higher levels of problem solving (β = .19, p < .01), and income was associated with higher levels of positive involvement (β = .26, p < .001) and skill encouragement (β = 28, p < .001). Among the risk factors, more months of deployment were associated with lower levels of positive involvement (β = −.15, p < .05).

Table 3.

SEM Regression Coefficients for Prediction of Fathers’ Parenting Outcomes using hierarchical block entry for Model 1 and 2.

| Problem Solving |

Harsh Discipline |

Positive Involvement |

Skill Encouragement |

Monitoring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| Parent Age | −.017 | .001 | −.170* | −.186* | −.073 |

| Child Age | .025 | −.037 | −.123 | −.196** | −.082 |

| Education | .192** | −.094 | .110 | .079 | .054 |

| Income | .038 | −.052 | .259*** | .275*** | .077 |

| Months Deployed | −.072 | .020 | −.149* | .059 | .061 |

| Negative Life Events | .019 | −.103 | .127 | .054 | .074 |

| Combat Stress | .014 | −.078 | −.021 | .016 | .064 |

| Log PTSD Symptoms | .032 | −.012 | −.076 | −.101 | −.095 |

| Dyadic Adjustment | −.024 | −.056 | .097 | −.059 | −.004 |

| Social Support | −.066 | .091 | −.067 | −.039 | −.054 |

| R2 | .052 | .039 | .152 | .135 | .037 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Income × Support | .064 | −.067* | .095 | .093 | .049 |

| Months Deployed × Support | .023 | .008 | −.026 | −.056 | .071 |

| Life Events × Support | −.021 | −.031 | −.049 | .010 | .060 |

| Combat Stress × Support | .127 | −.022 | −.092 | −.080 | −.064 |

| PTSD × Support | −.049 | .003 | .012 | −.100 | −.120 |

| R2 | .079 | .071 | .174 | .177 | .057 |

Note: SEM regression models are block entry for Model 1 and Model 2. Standardized coefficients are displayed.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05.

Model 2 shows that there was one significant interaction - higher levels of income by social support was associated with lower levels of coercive harsh discipline (β = −.07, p < .05). To examine the statistical reliability of the interaction effects we used model-based estimates to plot the conditioning effects and region of significance for the interaction terms (see Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). For the income × support on coercive discipline interaction, the confidence bands contained a zero slope for the income effect on discipline up to roughly 1 standard deviation in levels of social support. Beyond one standard deviation, higher levels of social support in combination with income were associated with lower levels of discipline. However, only about 15% of the sample data were contained in the region of significance. Further, among the parenting scores, harsh discipline had the lowest base rate mean value and was positively skewed; we replicated the interaction with a log transformed score, again with roughly 15% of the sample data in the region of significance.

Discussion

Results suggest that a combination of risk and protective factors was associated with observed overall effective parenting practices for this sample of NG/R fathers deployed to the recent conflicts. Income demonstrated the strongest association with observed parenting, such that higher levels of income were associated with more effective parenting. In the examination of the specific parenting domains, income was significantly positively associated both with skill encouragement and positive involvement. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating the importance of income for parenting and child outcomes (e.g. Conger et al., 2002; Yeung et al., 2002). Typically, however, the focus is on impairments in parenting practices secondary to poverty; few studies have extended the income-parenting relationship to middle and upper-income families (Gershoff et al., 2007). We were surprised that income would have such a robust association with parenting in this primarily middle-income sample of NG/R families. However, it is possible that particularly for NG/R families who may be more isolated with fewer overall supports than active duty families, extra income offers a buffer that enables them to purchase goods and services to support the family through deployment transitions. Babysitting, after school and summer programs, for instance, may be lifelines for families when a father is deployed, but these services are costly. When fathers return, income may increase, somewhat mitigating the stress of reintegration on parents, enabling a father to positively engage with his children without the stress of worries about meeting material needs. Given this, and the higher income nature of the sample, it is not surprising that income was specifically associated with positive involvement (the affective aspects of parenting, such as warmth), and skill encouragement (using positive parenting techniques to teach children prosocial behaviors).

Other putative protective factors – dyadic adjustment, parenting social support, and education - were not significantly associated with overall effective parenting practices, but higher father’s education was associated with better father-child problem solving. Problem-solving models flexibility, perspective-taking, and compromise in solving conflicts. More highly educated fathers may show better problem-solving because higher education teaches individuals to think and flexibly apply new skills to solve problems in innovative ways (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003).

The lack of findings for dyadic adjustment and parenting support suggest that neither a father’s perception of the strength of the couple relationship, nor his reports of parenting support are associated with observed effective parenting. We could find no other studies examining these constructs with observed parenting in military samples. However, we speculate that, in families where a father has been deployed for extended periods of time, and, in most cases, a mother has ‘picked up the slack’, his post-deployment parenting effectiveness may not be influenced by spouse and other relationships. Stated differently, a father may return to a post-deployment family environment in which he must work hard and quite proactively to reconnect with his children, regardless of the couple relationship. Support for parenting, while crucial for mothers during deployment, may almost be irrelevant for reintegrating fathers who are trying to reconnect with their children, particularly when finances are not a stressor. For example, one of our participants, during a parenting group discussion about fathering after deployment, talked about working hard to ensure that his children came to him with questions and concerns, rather than to his wife. He reported taking them on father-child fishing weekends away, and other activities aimed at strengthening the father-child relationship. Several years after his return from deployment, his children still naturally turned to their mother first.

With regard to risk factors, total number of months deployed was significantly negatively associated with effective parenting, as well as with the specific parenting domain of positive involvement (i.e. more months deployed associated with lower positive involvement). An increasing body of research is emerging to demonstrate the detrimental effects of wartime deployment on families regardless of the nature (i.e. extent of combat exposure) of those deployments. That is, while historically, studies of deployment on families attempted to understand how the residue of combat trauma affects families (e.g., the impact of a service member’s posttraumatic stress disorder, or traumatic brain injury, on children and family), there has been an increasing spotlight on the long separation inherent in deployment as a detrimental factor for family life. In this sample of National Guard and Reserve fathers, deployment length demonstrated the most robust association (indeed the only significant main effect) with observed effective parenting practices. Effective parenting requires practice, and, put quite simply, fathers who are absent for long periods of time do not have the opportunity to practice being effective parents. When they return from deployment, fathers may just not be able to make up for lost time with their children without help. As we further analyze study data, we will be able to examine whether an intervention to support parenting can in fact meaningfully improve parenting, and ultimately child adjustment in this Reserve Component population. Also yet to be examined is whether this association between length of deployment and parenting incorporates a threshold effect – i.e. whether meaningful decrement in parenting occurs only after a specified length of time away. Research among residential and nonresidential civilian fathers who spend time away from their children (e.g., due to extensive travel, post-divorce residence, or incarceration) indicates that higher levels of involvement benefit children (Lamb, 2004).

Although no prior research has examined the association of deployment length with observed parenting in any military sample, studies have examined the association of deployment length on children’s outcomes, finding it to be associated with greater psychological stress among children. In a study of military children aged 11 – 17 and their caregivers, length of parental deployment was associated with a greater number of challenges for children both during deployment and upon the deployed parent’s return (Chandra et al., 2010). In a study comparing families of singly- and multiply-deployed families, Barker and Berry found length of time of individual deployments and total time the deployed parent was absent was associated with increased child behavior problems (Barker & Berry, 2009) In a study of a family-based prevention program for parents returning from deployment, the cumulative length of time parents were deployed during a child’s lifetime was associated with increased child depression and externalizing symptoms. Furthermore, the effects of length of deployment on children were predicted by the psychological distress of both the deployed parent and the child’s at home caregiver (Lester et al., 2011). Much prior research has demonstrated the importance of parenting for child outcomes; but no military study has yet demonstrated a mediating role of observed parenting practices in the association between deployment length and child adjustment. Although child adjustment was not examined in this study, it clearly is a key factor in understanding parenting and deployment; our longitudinal data will enable us to further disentangle relationships among deployment length, observed parenting, and child adjustment.

Somewhat surprisingly, PTSD symptoms, negative life events, and battle experiences were not associated with observed parenting. Prior research has demonstrated a link between PTSD symptoms and self-reported parenting challenges (e.g., (Gewirtz et al., 2010), but no research that we know of has shown links between observed parenting and PTSD symptoms. However, a large body of research has demonstrated associations between parental psychopathology more broadly (e.g. depression) and observational (and self-report) measures of parenting in both fathers and mothers (Patterson & Forgatch, 1990). Within this sample, it should be noted that just 15% of fathers met or exceeded the clinical cut off for PTSD. Although this is higher than civilian samples, it is significantly lower than other NG/R samples reported in the literature (e.g. Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007). It is possible that observed parenting is impaired only at high levels of PTSD symptoms, and not, as with the majority of this sample, at subclinical levels. It also is possible that PTSD exerts different effects on parenting compared with other psychopathology (e.g. depression). For example, self-reported parenting impairments secondary to high levels of PTSD symptoms may not be easily observable in differences in parenting practices because fathers with PTSD may be able to ‘hold it together’ with their children in ways that depressed parents may not. It is important to note that very little research has demonstrated associations of fathering behavior with psychopathology in general – much of our knowledge is based on studies of mothers.

We were less surprised to see lack of associations between battle experiences and observed parenting. Although adverse experiences undoubtedly affect parenting (Masten, 2001), on average, fathers did not experience high levels of battle experiences and we might expect the impact of these experiences on parenting to be ‘filtered’ through PTSD and other psychopathology rather than having direct effects. Yet to be examined is whether this finding may be due to intervening variables such as social resources and supports. For example, a father experiencing more battle experiences may be more likely to access services (case management, therapy, financial or other material resources, help with job finding, etc), which may, in turn, provide him support to increase his emotional connection with his child(ren). Only longitudinal analyses will enable us to disentangle these relationships.

Among control variables, parent age was negatively associated with parenting practices, with younger parents demonstrating more effective parenting. It is possible that older parents have simply had more deployments (i.e. missed more of their children’s lives), or that older parents have older children, which can be more stressful than parenting early elementary children and require more sophisticated approaches to parenting. This may be especially true in dealing with emerging adolescents on emotionally complex issues like the separation of deployment to combat (Huebner & Mancini, 2005).

Limitations

First, this is a cross-sectional study, and thus direction of associations cannot be inferred. Second, our sample was limited to NG/R families with school age children, and thus is not representative of the military as a whole, or even the Reserve Component as a whole, given the age of parents and children in our sample, as well as their socio-demographics. That is, by virtue of the fact that our participants have 4–13 year old children, our sample consists of older fathers, married for longer, and with higher incomes than many military personnel. Third, although we made every attempt to recruit broadly for this study (for example, inviting participation from every father living in our target regions who returned from deployment over a three year period) participation in the study was voluntary. Finally, our results point to the fact that many of the correlates of observed parenting (income, education) in this sample have been shown to be general correlates of parenting in civilian samples. Additionally, although length of deployment was associated with parenting, neither combat experiences nor PTSD symptoms were associated. It could therefore be argued that deployment is simply a proxy for separation from the child, and, in that sense, the factors associated with parenting in military fathers are no different from those among civilian fathers. Clearly, further research (using civilian comparison samples of fathers who are separated from their children) is needed to test this. Finally, information about the father’s relationship to the child was not collected, so exploring the significance of biological versus adoptive or step child relationships with their father was not possible.

Implications for psychologists in public sector and organized service settings

Notwithstanding the limitations, this study is the first to report correlates of parenting practices among NG/R fathers. Little is known about fathering in general, compared to parenting behaviors of mothers; almost nothing is known about fathering in military families. Yet, over the past decade, a million parents have been deployed in service of our nation’s wars, affecting more than 1.4 million children (Creech, Hadley, & Borsari, 2014). Protecting crucial parenting functions – to strengthen the next generation of US military families - should be a priority for military family psychological providers (Pemberton, Kramer, Borego, & Owen, 2013). Our data, though they should be considered preliminary, demonstrate the importance of paying special attention to fathering in the socio-economic and military context in which the family resides. Fathers who face multiple, lengthy deployments may need special supports to strengthen parenting during reintegration. Lower income fathers and particularly those who also lack strong parenting support may also be at risk. Psychological providers within public systems such as VA have a special opportunity to highlight to fathers the importance of effective parenting and to provide fathers with needed support (e.g. simple tools to strengthen parenting, such as effective discipline, teaching through encouragement, and the importance of being involved with children. Resources have been developed to provide psycho-education particularly for families where fathers struggle with PTSD (Sherman, 2008).

Although VA hospitals have not typically provided services around parenting, or to families, recent policy changes at the Department of Veterans Affairs have lifted the barriers to serving the whole family, rather than just the service member and spouse. Both the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (http://www.veterantraining.va.gov), and the Department of Defense (AfterDeployment.Org, and Military Kids Connect) have developed online resources for parenting after deployment. Parenting programs such as After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools (ADAPT; Gewirtz, Pinna, Hanson, & Brockberg, 2014) have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of providing parenting programs within the VA system (M. A. Polusny, September, 28, 2013). Extending and widely implementing these interventions for military families is underway but the need to support military families is urgent and cannot wait.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by grant number R01 DA030114 to Abigail H. Gewirtz, and in part by P50 DA035763.

Contributor Information

Laurel Davis, University of Minnesota

Sheila K. Hanson, University of Minnesota, Crookston.

Osnat Zamir, University of Minnesota, Department of Family Social Science.

Abigail H. Gewirtz, University of Minnesota, Department of Family Social Science & Institute of Child Development.

David S. DeGarmo, Oregon Social Learning Center and University of Oregon, Prevention Science Institute, Educational Methodology, Policy, and Leadership.

References

- Armstrong MI, Birnie-Lefcovitch S, Ungar MT. Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Barker LH, Berry K. Developmental issues impacting military families with young children during single and multiple deployments. Military Medicine. 2009;174:1033–1040. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-04-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black WG. Military-induced family separation: A stress reduction intervention. Social Work. 1993;38:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor W, Najman JM, Andersen MJ, O’callaghan M, Williams GM, Behrens BC. The relationship between low family income and psychological disturbance in young children: an Australian longitudinal study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:664–675. doi: 10.3109/00048679709062679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Bradley RH. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, Rich B, Querido JG. Parenting disruptive preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:203–213. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019771.43161.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KE, Lee BA. Sources of personal neighbor networks: Social integration, need, or time? Social Forces. 1992;70:1077–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Lara-Cinisomo S, Jaycox LH, Tanielian T, Burns RM, Ruder T, Bing H. Children on the homefront: The experience of children from military families. Pediatrics. 2010;125:16–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech SK, Hadley W, Borsari B. The impact of military deployment and reintegration on children and parenting: A systematic review. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035055. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for behavioral sciences. 3 ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annal . Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, Greenberg M, Ragozin A, Robinson N, Basham R. Effects of stress and social support on mothers and infants. Child Development. 1983;54:209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo D, Bryson K. Parenting Support Index. Eugene, OR: OSLC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS. Coercive and prosocial fathering, antisocial personality, and growth in children’s postdivorce noncompliance. Child Development. 2010;81:503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo D, Forgatch M. Efficacy of parent training for stepfathers: From playful spectator to effective stepfathering. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2007;7:331–355. doi: 10.1080/15295190701665631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. A confidant support and problem solving model of divorced fathers’ parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49:258–269. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9437-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patras J, Eap S. Social Support for Divorced Fathers’ Parenting: Testing a Stress-Buffering Model. Family Relations. 2008;57:35–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe E, Ross A. Parenting cycle of deployment. Military Medicine. 2012;177:184–190. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Kouneski EF, Erickson MF. Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60(2):277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, Compton JS. Couple adjustment and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in National Guard veterans of the Iraq war. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:479–487. doi: 10.1037/a0024007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Knutson N, Mayne T. Coder impressions of ODS lab tasks. Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. Methodological issues in the direct observation of parent-child interaction: Do observational findings reflect the natural behavior of participants? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(3):185–198. doi: 10.1023/a:1009503409699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child development. 2007;78(1):70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, Plowman EJ, August G, Realmuto G. Parenting, parental mental health, and child functioning in families residing in supportive housing. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:336–347. doi: 10.1037/a0016732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz A, Pinna K, Hanson S, Brockberg D. Promoting parenting to support reintegrating military families. Psychological Services. 2014;11:31–40. doi: 10.1037/a0034134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Polusny M, DeGarmo D, Khaylis A, Erbes C. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq: Associations with parenting and couple adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(5):599–610. doi: 10.1037/a0020571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J. Citizens coping as soldiers: A review of deployment stress symptoms among reservists. Military Psychology. 2010;22:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J, West C. The Army National Guard in OIF/OEF: Relationships among combat exposure, postdeployment stressors, social support, and risk behaviors. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2010;14:86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner AJ, Mancini JA. Adjustments among adolescents in military families when a parent is deployed: A final report to the Military Family Research Institute and Department of Defense Quality of Life Office. Falls Church, VA: Virginia Tech; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, Best M, Lefebvre M, Vito D. The seven-item short form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Jelicic H, Phelps E, Lerner R. Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1195–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Grogan D, Xenakis SN, Bain MW. Father absence: effects on child and maternal psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28(2):171–175. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Watanabe HK, Richters JE, Cortes R, Roper M, Liu S. Prevalence of mental disorder in military children and adolescents: Findings from a two-stage community survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(11):1514–1524. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaylis A, Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Gewirtz A, Rath M. Posttraumatic stress, family adjustment, and treatment preferences among National Guard soldiers deployed to OEF/OIF. Military Medicine. 2011;176:126–131. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, Samper RE. Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology. 2006;18:89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3 ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. The role of the father in child development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lester P, Mogil C, Saltzman W, Woodward K, Nash W, Leskin G, Beardslee W. Families overcoming under stress: Implementing family-centered prevention for military families facing wartime deployments and combat operational stress. Military Medicine. 2011;176(1):19–25. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Kohen DE. Family processes as pathways from income to young children’s development. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):719–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean A, Elder GH., Jr Military service in the life course. Sociology. 2007;33:175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56:227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis LA, Barry RA, Kehle SM, Erbes CR, Polusny MA. Relationship adjustment, PTSD symptoms, and treatment utilization among coupled National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(5):560–567. doi: 10.1037/a0020925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(18):2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73:935–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide. 6 ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Military Family Association. Report on the cycles of deployment. Alexandria, VA: National Military Family Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck JS. Modification of recent life event questionnaires for use with female respondents. Research on Nursing and Health. 1984;7:61–71. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive Family Process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The next generation of PMTO models. Behavior Therapist. 2005;28:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Initiation and maintenance of processes disrupting single-mother families. In: Patterson GR, editor. Depression and aggression in family interaction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Cascading effects following intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:949–970. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton JR, Kramer TL, Borrego J, Jr, Owen RR. Kids at the VA? A call for evidence-based parenting interventions for returning veterans. Psychological services. 2013;10(2):194–202. doi: 10.1037/a0029995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck EH. In: Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. 3 ed. Lamb ME, editor. New York, NY: Wiley: The role of the father in child development; 1997. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Murdoch M, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Rath MB. Prospective risk factors for new-onset post-traumatic stress disorder in National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:687–698. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Foster S, Kent RN, O’Leary KD. Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. Journal of applied behavior analysis. 1979;12:691–700. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw KD, Rodrigues CS, Jones DH. Psychological symptoms and marital satisfaction in spouses of Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans: Relationships with spouses’ perceptions of veterans’ experiences and symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:586. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian version. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper RE, Taft CT, King DW, King LA. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and parenting satisfaction among a national sample of male Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:311–315. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038479.30903.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CF, Rogers HJ. Preliminary validation of the Abbreviated Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Some psychometric data regarding a screening test of marital adjustment. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1984;44:1045–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman MD. SAFE Program: Support and Family Education: Mental Health Facts for Families. 3rd ed. Oklahoma City VA Medical Center; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:614–623. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt DS, Proctor SP, King DW, King LA, Vasterling JJ. Validation of scales from the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory in a sample of Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Assessment. 2008;15:391–403. doi: 10.1177/1073191108316030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt DS, Samper RE, King DW, King LA, Martin JA. Deployment stressors and posttraumatic stress symptomatology: Comparing active duty and National Guard/Reserve personnel from Gulf War I. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:66–74. doi: 10.1002/jts.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist: Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Stress: A potential disruptor of parent perceptions and family interactions. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Werber L, Harrell M, Varda D, Hall K, Beckett M. Deployment experiences of Guard and Reserve families: Implications for support and retention. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AR, Stone RAT. Exploring stress and coping strategies among National Guard spouses during times of deployment. Armed Forces & Society. 2010;36:545–557. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child development. 2002;73:1861–1879. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]