Abstract

Cladobranchia (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) is a diverse (approx. 1000 species) but understudied group of sea slug molluscs. In order to fully comprehend the diversity of nudibranchs and the evolution of character traits within Cladobranchia, a solid understanding of evolutionary relationships is necessary. To date, only two direct attempts have been made to understand the evolutionary relationships within Cladobranchia, neither of which resulted in well-supported phylogenetic hypotheses. In addition to these studies, several others have addressed some of the relationships within this clade while investigating the evolutionary history of more inclusive groups (Nudibranchia and Euthyneura). However, all of the resulting phylogenetic hypotheses contain conflicting topologies within Cladobranchia. In this study, we address some of these long-standing issues regarding the evolutionary history of Cladobranchia using RNA-Seq data (transcriptomes). We sequenced 16 transcriptomes and combined these with four transcriptomes from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive. Transcript assembly using Trinity and orthology determination using HaMStR yielded 839 orthologous groups for analysis. These data provide a well-supported and almost fully resolved phylogenetic hypothesis for Cladobranchia. Our results support the monophyly of Cladobranchia and the sub-clade Aeolidida, but reject the monophyly of Dendronotida.

Keywords: Mollusca, phylogenomics, nudibranchs, sea slugs, RNA-Seq, phylotranscriptomics

1. Introduction

Cladobranchia is a diverse (approx. 1000 species) but understudied and poorly understood group of sea slug molluscs. It is also a clade within Nudibranchia, which is a group of marine gastropods defined by the loss of the adult shell [1]. In the absence of a protective shell, these slug lineages have evolved a diverse array of alternative defence mechanisms. The development of chemical and physical defence mechanisms has allowed for the occupation of new ecological niches [2] and has been hypothesized as having been a primary driver in the diversification of Nudibranchia [1]. Defensive strategies found in Cladobranchia include the uptake or synthesis of biochemically active compounds [3,4], the presence of warning (aposematic) coloration [5] or cryptic coloration to deter or hide from predators, respectively, and the use of stinging organelles (nematocysts) acquired from cnidarian prey [1,6]. The theft and synthesis of biochemically active compounds has provided a pool of materials that have potential uses in the synthesis of new pharmaceuticals (e.g. Zalypsis, currently in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of various cancers; made from a chemical isolated from Jorunna funebris) [7–9]. Strong phylogenetic hypotheses of Cladobranchia will be useful in understanding the evolution of these chemical defences and the evolution of other character traits, such as the ability of many cladobranch species to sequester nematocysts [6] and swimming behaviours [10].

To date, there have been only two large-scale phylogenies published specifically on Cladobranchia [11,12], the first of which used the three genes most commonly used in nudibranch phylogenetics (mitochondrial 16S rRNA and cytochrome oxidase I (COI), and nuclear histone H3) [11]. The second study used all data publicly available through GenBank [13] to understand the evolutionary relationships of members of this group, thus adding two additional genes and increasing taxon sampling by approximately 200 taxa [12]. In both of these phylogenetic inferences of Cladobranchia, the majority of relationships remained unclear, both between and within the three traditional taxonomic divisions of Cladobranchia (Arminida, approx. 100 species; Dendronotida, approx. 250 species; and Aeolidida, approx. 600 species). The name of the taxon Arminida was changed by Bouchet & Rocroi [14], who introduced the taxon Euarminida for the two families Arminidae and Doridomorphidae. Though the analysis by Pola & Gosliner [11] supported the inclusion of only those families within a clade, they disagreed with the name change and retained Arminida in an altered sense, which we follow.

In addition to the phylogenies specifically aimed at understanding relationships within Cladobranchia, phylogenetic inferences have been attempted to address the evolutionary history of Nudibranchia or the larger clade Euthyneura [15–21]. The results regarding the major groupings within Cladobranchia were inconsistent in all of these studies, with all three major divisions considered both paraphyletic and monophyletic in different publications. The most recent and comprehensive work by Wollscheid-Lengling et al. [16], based on the 18S, 16S and COI genes, suggested that Aeolidida is monophyletic and both Dendronotida and Arminida are paraphyletic.

Though the more basal evolutionary history of Cladobranchia has been problematic for phylogenetic inference, a number of studies (both morphological and molecular) have provided evidence to support relationships at both the family and generic levels. Phylogenies of individual families have been published on Aeolidiidae [22], Arminidae [23,24], Bornellidae [25], Glaucidae [26], Scyllaeidae [27] and Tritoniidae [28], and at the genus level publications have focused on Antaeolidiella [29], Babakina [30,31], Berghia [32], Burnaia [33], Dendronotus [34–36], Limenandra [37], Melibe [38], Phyllodesmium [39,40] and Spurilla [41]. All of these studies were focused on particular aspects of the Cladobranchia tree, and although they have supported some relationships, it is clear that the overall relationships of higher level groups in Cladobranchia are not well understood. In addition, individually these studies cover very little of the overall diversity of Cladobranchia.

Most importantly for the purposes of this paper, the phylogenies estimated in all previous studies on taxa within Cladobranchia have lacked the support needed for confidence in suprageneric taxonomic relationships, with the exception of a small subset of familial-level phylogenies, mentioned above. This lack of resolution and low overall bootstrap (BS) support demonstrates that the relatively small, multi-gene strategies that have been previously used for phylogenetic reconstruction are insufficient for comprehensive analyses and deep phylogenetic inferences regarding the relationships of this particular group. To address this, our paper presents a preliminary exploration into the use of RNA-Seq data to generate well-supported hypotheses regarding the evolutionary relationships within Cladobranchia. This study includes the publication of 16 new cladobranchian transcriptomes.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Organismal sampling

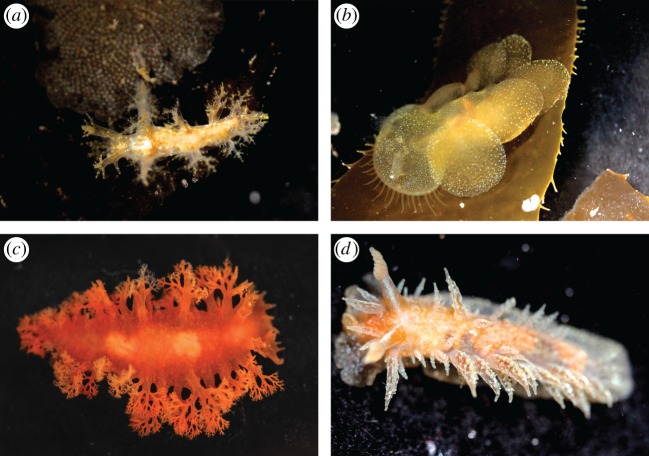

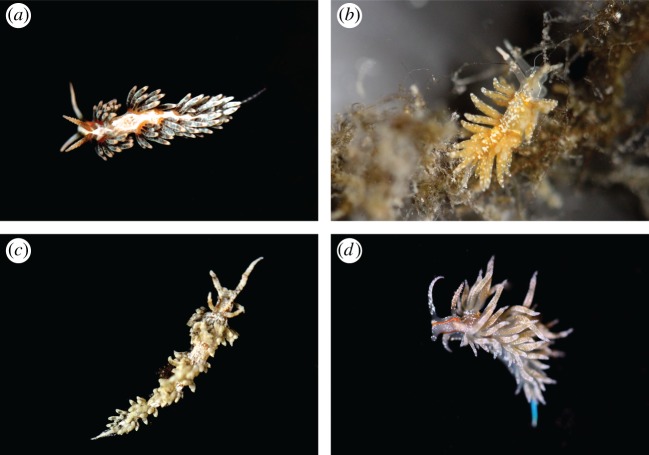

Two specimens of each representative species (a total of 16) were collected in tide pools or via snorkelling or SCUBA (under AAUS certification) using a variety of methods (direct collection, substrate collection and non-destructive collecting under rocks), with one individual used for RNA-Seq and one individual preserved as a voucher and deposited in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (SI-NMNH). Some specimen photographs are shown in figures 1 and 2. We generated raw transcriptome data by RNA-Seq for 16 Cladobranchia species and downloaded data for one additional Cladobranchia species from the US National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA). Three outgroup transcriptomes were also obtained from the SRA: two representatives of Anthobranchia (the sister taxon of Cladobranchia) and one of Pleurobranchoidea (the sister taxon to Nudibranchia). Specimen and sequence data are listed in table 1.

Figure 1.

Select photographs of dendronotid and unassigned taxa used in this project, including: (a) Dendronotus venustus (SRR1950948), (b) Melibe leonina, (c) Tritoniopsis frydis (SRR1950954) and (d) Dirona picta (USNM1276030).

Figure 2.

Select photographs of aeolid taxa used in this project, including: (a) Berghia stephanieae (SRR1950951), (b) Favorinus auritulus (USNM1276034), (c) Palisa papillata (SRR1950952) and (d) Dondice occidentalis.

Table 1.

List of specimens examined in this study, including species name, locality and morphological voucher information. SRA accession numbers are also provided for each transcriptome.

| species | locality | morphological voucher | SRA accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bathydoris clavigera | NCBI SRA | SRR1505104 | |

| Doris kerguelenensis | NCBI SRA | SRR1505108 | |

| Fiona pinnata | NCBI SRA | SRR1505109 | |

| Pleurobranchaea californica | NCBI SRA | SRR1505130 | |

| Austraeolis stearnsi | Point Loma, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276025 | SRR1950943 |

| Berghia stephanieae | Key Largo, FL, USA | — | SRR1950951 |

| Catriona columbiana | Redondo Beach, CA, USA | — | SRR1950949 |

| Cuthona albocrusta | Mission Bay, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276026 | SRR1950944 |

| Dendronotus venustus | Morro Bay, CA, USA | USNM1276033 | SRR1950948 |

| Dirona picta | Redondo Beach, CA, USA | USNM1276030 | SRR1950946 |

| Dondice occidentalis | Riviera Beach, FL, USA | USNM1276036 | SRR1950953 |

| Doto lancei | Mission Bay, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276027 | SRR1950945 |

| Favorinus auritulus | Key Largo, FL, USA | USNM1276034 | SRR1950950 |

| Flabellina iodinea | Point Loma, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276023 | SRR1950940 |

| Hermissenda crassicornis | Sunset Cliffs, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276022 | SRR1950939 |

| Janolus barbarensis | Point Loma, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276029 | SRR1950942 |

| Melibe leonina | Morro Bay, CA, USA | USNM1276031 | SRR1950947 |

| Palisa papillata | Key Largo, FL, USA | — | SRR1950952 |

| Tritonia festiva | Point Loma, San Diego, CA, USA | USNM1276024 | SRR1950941 |

| Tritoniopsis frydis | Pompano Beach, FL, USA | USNM1276038 | SRR1950954 |

A visual examination was used for confirmation of identity using field guides published by Valdés et al. [42] (for the Caribbean) and Behrens & Hermosillo [43] (for the eastern Pacific), as well as expert opinions when the placement of species was uncertain. One of the two specimens was placed in RNAlater solution (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for RNA preservation and frozen within one week of collection at −80°C to prevent RNA degradation. Some specimens in RNAlater were refrigerated or placed at −20°C within 24 h, others were kept at room temperature for up to one week. A second specimen of each species was preserved as a voucher for morphological analysis, first in Bouin's Fixative and subsequently transferred to 70% ethanol for long-term storage. Voucher specimens were deposited in the SI-NMNH and are available for study under the catalogue numbers provided in table 1.

2.2. RNA extraction and sequencing

A 20–100 mg tissue sample was taken from the anterior of each animal and manually homogenized using a motorized pestle. After 1–2 min of homogenizing, the tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent homogenizing, until tissue mixture was fully uniform. Five hundred microlitres of TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was then added and the mixture was homogenized again. This procedure was repeated until the solution was fully homogenized. Once this process was complete, an additional 500 μl of TRIzol Reagent was added to the solution and the mixture was left at room temperature for 5 min.

One hundred microlitres of bromochloropropane was then added to the solution, which was subsequently mixed thoroughly. The mixture was left at room temperature for 5 min, then centrifuged at 16 000g for 20 min at 8°C. Following this step, the top aqueous phase was removed and placed in another tube where 500 μl of 100% isopropanol was added. This tube was stored overnight at −20°C for RNA precipitation.

After overnight precipitation, the samples were centrifuged at 17 200g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then removed and the pellet washed with freshly prepared 75% ethanol. The sample was then centrifuged at 7500g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the pellet air-dried for 1–2 min (or until it looked slightly gelatinous and translucent). The total RNA was then re-suspended in 10–30 μl of Ambion Storage Solution (Life Technologies) and 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (Life Technologies) was added to prevent degradation.

Total RNA samples were submitted to the DNA Sequencing Facility at University of Maryland Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, where quality assessment, library preparation and sequencing were completed. RNA quality assessment was done with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and total RNA samples with a concentration higher than 50 ng μl−1 were used for library construction. For library preparation, the facility used the Illumina TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and 200 bp inserts; 100 bp, paired-end reads were sequenced with an Illumina HiSeq1000 (Illumina).

2.3. Quality control and assembly of reads

Reads that failed to pass the Illumina ‘Chastity’ quality filter were excluded from our analyses. Subsequent quality assessment and control were performed using autoadapt (v. 0.2 [44]) with default settings, which in turn used FastQC (v. 0.10.1 [45]) and cutadapt (v. 1.3 [46]) to remove overrepresented sequences and to trim and remove low-quality reads. Reads passing quality control were assembled using Trinity (v. r20140717 [47]) with default settings, which required assembled contigs to be at least 200 bp long.

2.4. Orthology assignment

Translated transcript fragments were organized into orthologous groups corresponding to a custom gastropod-specific core-orthologue set (3854 protein models) using HaMStR (v. 13.2.2 [48]), which in turn used FASTA (v. 36.3.6d [49]), GeneWise (v. 2.2.0 [50]) and HMMER (v. 3.0 [51]). In the first step of the HaMStR procedure, substrings of assembled transcripts (translated nucleotide sequences) that matched one of the gastropod protein models were provisionally assigned to that orthologous group. To reduce the number of highly divergent, potentially paralogous sequences returned by this search, we set the E-value cut-off defining a hidden Markov model (HMM) hit to 1×10−5 (the HaMStR default is 1.0) and retained only the top-scoring quartile of hits. In the second HaMStR step, the provisional hits from the HMM search were compared to our reference taxon, Aplysia californica, and retained only if they survived a reciprocal best BLAST [52] hit test with the reference taxon using an E-value cut-off of 1×10−5 (the HaMStR default was 10.0). In our implementation, we substituted FASTA [49] for BLAST because FASTA programs readily accepted our custom substitution matrix (GASTRO50).

The gastropod core-orthologue set was generated by first downloading all available gastropod clusters with 50% similarity or higher from UniProt [53] (39 403 clusters). Excluding clusters that contained only one sequence left 6160 clusters. We calculated the sequence similarity of each cluster and, as a heuristic, decided to remove clusters whose percentage identity was less than 70%, which left 6015 clusters. We then assessed the number of times each taxon was represented within those clusters. Aplysia californica was identified as the most abundant taxon (3854 associated clusters with 70% similarity or higher) and was therefore selected as the reference taxon for the custom HaMStR database. We constructed the gastropod HaMStR database by following the steps given in the HaMStR README file, which included generating profile HMMs for each cluster using HMMER. Our gastropod HaMStR database contained 3854 orthologous groups. All protein sequences for A. californica (Uniprot/NCBI taxon ID 6500) were downloaded from UniProt and used to generate the BLAST database for HaMStR.

Construction of the custom substitution matrix (GASTRO50) followed the procedure outlined in Lemaitre et al. [54] and used the 50%-similarity gastropod clusters downloaded from UniProt. In this protocol, a block is defined as a conserved, gap-free region of the alignment. Our blocks output file contained 34 109 blocks and a total of 2 442 130 amino acid positions. (This was after we removed one large block from the blocks output file that contained 1388 sequences, which prevented the scripts from executing properly.)

2.5. Construction of data matrix and paralogy filtering

Protein sequences in each orthologous group were aligned using MAFFT (v. 7.187 [55]). We used the ---auto and ---addfragments options of MAFFT to add transcript fragments to the A. californica reference sequence, which was considered the existing alignment. We converted the protein alignments to corresponding nucleotide alignments using a custom Perl script. A maximum-likelihood tree was inferred for each orthologous group using GARLI (v. 2.1 [56]) and was given as input to PhyloTreePruner (v. 1.0 [57]). Following the workflow of Bazinet et al. [58], orthologous groups that showed evidence of out-paralogues for any taxa were discarded; for those with in-paralogues, multiple sequences were combined into a single consensus sequence for each taxon. This process left 839 orthologous groups eligible for inclusion in data matrices. Individual orthologous group alignments were then concatenated (nt123_unfiltered matrix). Positions not represented by sequence data in at least four taxa were then removed (nt123 matrix), which resulted in more compact data matrices. To address potential issues in regards to missing data, three additional matrices were generated by increasing the required representation for a position to remain within the data matrices: nt123_min80percentcomplete (position must have been represented in at least 16 taxa), nt123_min90percentcomplete (position must have been represented in at least 18 taxa) and nt123_100percent complete(position must have been represented in all taxa).

The nt123 nucleotide matrix was then subjected to degen1 encoding (v. 1.4 [59]), which we refer to as our degen matrix. ‘Degen’ uses degeneration coding to eliminate all synonymous differences among species from the dataset, resulting in phylogeny inference based only on non-synonymous nucleotide change. This procedure was shown in a previous study [60] to generally improve recovery of deep nodes.

2.6. Phylogenetic analyses

To conduct the phylogenetic analyses, we used Genetic Algorithm for Rapid Likelihood Inference (GARLI, v. 2.1 [56]) through the GARLI Web service hosted at molecularevolution.org [61]. We used a general time reversible nucleotide model [62] with a proportion of invariant sites and among site rate heterogeneity modelled with a discrete gamma distribution (GTR+I+G) together with GARLI default settings, including stepwise-addition starting trees. We first analysed the nt123_unfiltereddata matrix, partitioned by codon position (nt123_partitioned; electronic supplementary material, figure S1), followed by the unpartitioned nt123 and degen data matrices (nt123 and degen analyses, respectively; electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3). We then analysed the partitioned nt123_unfiltered data matrix including only the first and second codon positions (nt12_partitioned; electronic supplementary material, figure S4) and the three more complete matrices nt123_min80percentcomplete (nt123_min80; electronic supplementary material figure S5), nt123_min90percentcomplete (nt123_min90; electronic supplementary material figure S6) and nt123_100percentcomplete (nt123_100percent; electronic supplementary material, figure S7). For each analysis, we ran 10 best tree searches and 1000 BS replicates. Post-processing of the phylogenetic inference results was performed by the GARLI Web service at molecularevolution.org using DendroPy [63] and the R system for statistical computing [64], which included the construction of a BS consensus tree.

3. Results

3.1. Read quality statistics

The raw number of 101 bp reads for each newly sequenced transcriptome ranged from 44 805 574 to 65 504 176 (mean: approx. 55 million reads; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Read processing (filtering and trimming) removed 1.40–9.14% of reads per sample (mean: 3.96%); thus, the number of reads provided as input to assembly ranged from 43 047 096 to 63 155 516 (mean: approx. 52 million).

3.2. Assembly and data matrix properties

The number of transcript fragments per sample ranged from 56 091 to 242 632 (mean: 108 957; electronic supplementary material, table S2). N50 ranged from 408 to 921 bases (mean: 714). HaMStR results for the 839 orthologous groups used in our analyses are presented in table 2 (HaMStR results for the complete set of orthologous groups are presented in the electronic supplementary material, table S3). The number of sequences from each assembly that matched the HaMStR database ranged from 662 to 1765 (mean: 1172). However, the number of matches to unique orthologous groups ranged from 599 to 1126 (mean: 916). The mean length of matching sequences was 249 amino acids. When concatenated and filtered, the final data matrices contained 9354–1 702 782 nucleotide positions from 839 orthologous groups and were 23.1–100% complete (electronic supplementary material, table S4).

Table 2.

HaMStR statistics for the subset of orthologous groups passing our paralogy filter, given for each taxon.

| species | sequences matching orthologous groups | unique orthologous groups represented | mean length (in amino acids) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bathydoris clavigera | 782 | 621 | 215 |

| Doris kerguelenensis | 622 | 530 | 190 |

| Fiona pinnata | 723 | 623 | 232 |

| Pleurobranchaea californica | 918 | 698 | 217 |

| Austraeolis stearnsi | 607 | 578 | 238 |

| Berghia stephanieae | 629 | 587 | 228 |

| Catriona columbiana | 540 | 513 | 224 |

| Cuthona albocrusta | 630 | 576 | 239 |

| Dendronotus venustus | 763 | 674 | 263 |

| Dirona picta | 589 | 558 | 227 |

| Dondice occidentalis | 621 | 578 | 227 |

| Doto lancei | 470 | 446 | 205 |

| Favorinus auritulus | 673 | 626 | 255 |

| Flabellina iodinea | 660 | 613 | 264 |

| Hermissenda crassicornis | 619 | 593 | 226 |

| Janolus barbarensis | 356 | 351 | 174 |

| Melibe leonina | 627 | 591 | 229 |

| Palisa papillata | 615 | 581 | 226 |

| Tritonia festiva | 469 | 453 | 168 |

| Tritoniopsis frydis | 407 | 388 | 210 |

3.3. Phylogenetic results

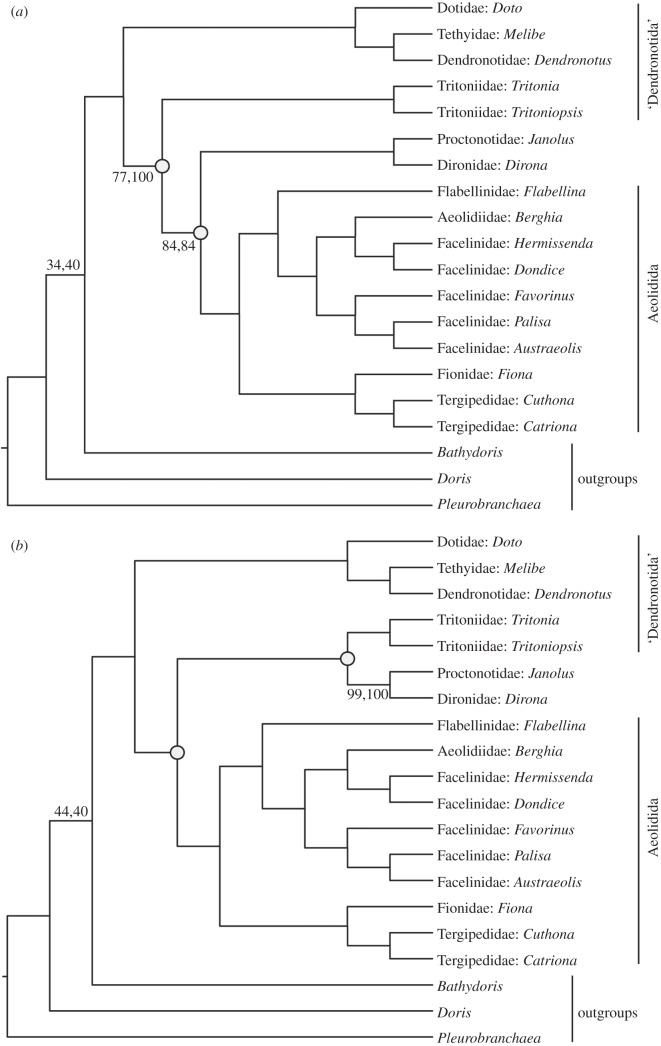

Our analyses supported Cladobranchia as a monophyletic group with a BS value of 100% (figure 3). This result remains consistent across topologies derived from all seven analyses.

Figure 3.

(a) The maximum-likelihood tree from the degen (first BS value) and nt12_partitioned (second BS value) analyses; (b) the maximum-likelihood tree from the nt123 (first BS value) and nt123_partitioned (second BS value) analyses. All unlabelled nodes have 100% BS support in both analyses; open circles indicate an inconsistent branching pattern between the two trees.

Aeolidida is also monophyletic (BS=100%) across all topologies, containing Flabellina (Flabellinidae), Berghia (Aeolidiidae), Hermissenda (Facelinidae), Dondice (Facelinidae), Favorinus (Facelinidae), Palisa (Facelinidae), Austraeolis (Facelinidae), Fiona (Fionidae), Cuthona (Tergipedidae) and Catriona (Tergipedidae). Facelinidae is paraphyletic due to the inclusion of Berghia in a clade with the members of this family. This clade is sister to Flabellinidae (BS=100%). In the sister group, Tergipedidae is monophyletic (BS=100%) and is the sister taxon to Fionidae (BS=100%).

Dendronotida is paraphyletic in all topologies. The degen and nt12_partitioned analyses (figure 3a) supported three clades within Dendronotida, and the nt123 and nt123_partitioned analyses (figure 3b) supported two clades. The clade found in both topologies (BS=100%) contained Doto (Dotidae), Melibe (Tethyidae) and Dendronotus (Dendronotidae) and placed Tethyidae and Dendronotidae as sister groups (BS=100%). The topology returned by the nt123 analyses included a clade sister to Aeolidida (BS=100% in nt123 analyses) that contained Tritonia (Tritoniidae), Tritoniopsis (Tritoniidae), Janolus (Proctonotidae) and Dirona (Dironidae), whereas the degen and nt12_partitioned analyses both supported a clade containing Proctonotidae and Dironidae (BS=100%) as sister to Aeolidida (BS=84%, degen; 86%, nt12_partitioned), and the Tritoniidae clade (BS=100%) as sister to the Aeolidida+Proctonotidae+Dironidae assemblage (BS=77%, 100%).

4. Discussion

In this section, we first review the characteristics of our data across our bioinformatics pipeline and the construction of our data matrix. We then address the efficacy of transcriptome data for inferring phylogenetic relationships within Cladobranchia and examine potential methodological concerns. Finally, we discuss the novel results produced by our analyses and compare them to previous studies.

4.1. Bioinformatics pipeline and data matrix construction

The number of reads from newly sequenced transcriptomes was higher than from transcriptomes downloaded from the SRA (electronic supplementary material, table S1). This is possibly due to a greater depth of sequencing in our pipeline compared to the original paper that published those transcriptomes [65]. Alternatively, the data retrieved from the SRA had already been filtered, with many reads removed prior to download. Though the average number of transcript fragments from the Trinity assembly was lower in newly generated datasets, the average length of the fragments was higher (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Importantly, the number of sequences that matched to unique orthologous groups, and the average length of these sequences, was sufficient for all taxa (electronic supplementary material, table S3), indicating that sequencing depth may not be a limiting factor. After we removed sites that were represented in fewer than four taxa, overall matrix completeness was slightly higher than in the previous five-gene, 296-taxon analysis [12]. Most importantly, the number of loci used in this analysis was orders of magnitude higher than in the two previous phylogenetic studies on the evolutionary history of Cladobranchia [11,12].

4.2. Use of phylotranscriptomics to understand the evolution of Cladobranchia

Phylogenetic inference of Cladobranchia has been a difficult part of the larger problem of understanding the evolutionary history of Nudibranchia [11,12,16,22]. However, the high BS values among the ingroup taxa in our analyses suggest that RNA-Seq will be useful in generating a well-supported hypothesis of the phylogenetic relationships among genera in Cladobranchia, thereby providing a basis for establishing a classification at infraorder, superfamily and family levels that reflects evolutionary history. Our tree topologies are almost fully resolved by our data, and the nodes that are recovered consistently across all trees all have 100% BS support. Thus, a phylotranscriptomic approach for understanding the phylogeny of Cladobranchia seems to be extremely effective in providing evidence to support relationships that were previously uncertain.

4.3. Bootstrap support levels

Though our methodology seems to have produced good results, the possibility exists that some of our relatively sparse data matrices (with at most 46.8% completeness) may have misled our likelihood analyses [66]. To address this, we ran analyses with more complete matrices (87.9–100%). In these results, the BS support values are quite high across the phylogenies, even with a matrix length of 48 426 nucleotides (93.6% complete), although the values decrease considerably in the 100% complete matrix analysis. The overall topology of the phylogenies from these analyses was also consistent with the other analyses, with Dendronotida supported as paraphyletic, and Aeolidida and Cladobranchia supported as monophyletic. In addition, some research suggests that missing data may not be as much of a problem as some have suspected. In Cho et al. [67], a data matrix with 45% intentionally missing data yielded no signs of the contradictory groupings that missing data might produce. This result is consistent with those of four other studies from across a broad taxonomic range, including frogs [68], angiosperms [69], an entire phylum of eukaryotes [70] and strains of the HIV virus [71].

In addition to concerns regarding missing data, multiple studies have been published that suggest that BS values in phylogenomic analyses may be inflated, primarily due to incongruent gene topologies [72,73]. However, others have suggested that these issues are not as problematic as they may seem. In particular, Simmons & Norton [74] specifically state that BS methods do not seem to have an elevated false-positive rate, and Betancur et al. [75] found that the incongruence in the data of Salichos & Rokas [72] is probably the result of sampling error, and thus not likely to be responsible for inflated BS values. In the case of our data and analyses, it is important to note that the divergences within Nudibranchia are much more recent than those addressed by Salichos & Rokas [72], and the number of genes in our analyses surpasses those in Dell'Ampio et al. [73].

4.4. The phylogeny of Cladobranchia

These analyses have resolved several questions regarding the evolutionary relationships within Cladobranchia. First and foremost, the monophyly of Cladobranchia is reinforced with 100% BS support. Though monophyly was indicated in previous morphological [18] and molecular [12,16] analyses, there have also been studies suggesting paraphyly [11] when the genus Melibe was included.

Of the three traditional taxonomic divisions within this group, members of Dendronotida (Melibe, Dendronotus, Tritonia and Tritoniopsis) and Aeolidida (Flabellina, Berghia, Hermissenda, Dondice, Favorinus, Palisa, Austraeolis, Fiona, Cuthonaand Catriona) are included in our analyses, as well as three taxa (Doto, Dirona and Janolus) that were recently classified as unassigned to any of the three groups [11,16,20]. Both Janolus and Dirona were originally considered to be within Arminida, and Doto was once placed under Dendronotida before newer molecular analyses rejected those classifications [15,16,18]. In our analyses, Dendronotida is not supported as monophyletic, which is consistent with previous morphological [18] and molecular [11,12,16,20] phylogenetic hypotheses. Our results indicate a serious need for complete taxonomic revision of the taxa within this group. The monophyly of Aeolidida has also been uncertain. Molecular analyses of Nudibranchia have supported Aeolidida as both paraphyletic and monophyletic, depending on the genes used for the analysis [16]. Other molecular studies on the evolution of Cladobranchia have suggested that Aeolidida is monophyletic [11,20], with very low support, although another did not support Aeolidida as monophyletic [12]. Our analyses strongly support the hypothesis in Pola & Gosliner [11], with Aeolidida being monophyletic with extremely high BS support.

Given our taxon sampling, the earliest diverging lineage within Cladobranchia is a clade containing Dotidae (Doto), Tethyidae (Melibe) and Dendronotidae (Dendronotus), which is a result novel to this study. An exciting result is the inclusion of Melibe well within Cladobranchia. This particular genus of filter feeders, which captures crustaceans using a dome-like oral hood fringed by sensory tentacles [76], was excluded from Cladobranchia in a previous study [11]. In that study, the authors attributed this result to a deletion in a section of the COI fragment used in the phylogenetic analyses. Further examination included Melibe within Cladobranchia [12], but the Melibe clade was at the end of a long branch, and might therefore have caused issues in phylogenetic inference [77].

Elsewhere among the dendronotid taxa, the family Tritoniidae (Tritonia and Tritoniopsis) is supported as monophyletic, as is a group composed of Proctonotidae (Janolus) and Dironidae (Dirona). In previous molecular analyses, Tritoniidae has been revealed as both paraphyletic [12] and monophyletic [11], though the monophyly results were poorly supported, with a posterior probability below 0.6. In our analyses, the exact positions of these two clades are uncertain. In one of our analyses (nt123_unfiltered), these two clades are sister taxa (figure 1b), whereas other datasets (nt123 and degen) suggest that the clade consisting of Proctonidae and Dironidae is the sister taxon of Aeolidida. Neither of these cases were supported in any previous analyses, but the tree presented in figure 3b clearly provides stronger support for the two clades as sister taxa, and these analyses included both synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions.

Within Aeolidida, the families Tergipedidae (Cuthona and Catriona) and Fionidae (Fiona) are sister taxa, supporting a previous hypothesis [22]. The study of Carmona et al. [11] weakly supported these taxa as an early diverging lineage within Aeolidida. Here, our phylogenomic data strongly favour this clade as the sister group of the remaining aeolid taxa in our analysis. An especially interesting result within Aeolidida is the paraphyly of Facelinidae (Hermissenda, Dondice, Favorinus, Palisa and Austraeolis), which forms a clade with Aeolidiidae (Berghia) that is sister to Flabellinidae (Flabellina). The paraphyly of Facelinidae with respect to Aeolidiidae is consistent with the results of Carmona et al. [22] and Mahguib & Valdés [20]. Our data strongly support the hypothesis that Aeolidiidae is derived from within Facelinidae and that the closest relative to Aeolidiidae, among the facelinid taxa we have been able to include, is a clade consisting of Hermissenda and Dondice, two genera that were not included in the Carmona et al. study [18]. Our lone representative of Flabellinidae was revealed as the sister group of Facelinidae plus Aeolidiidae. Similarly, Carmona et al. [18] found flabellinids in a clade sister to a clade consisting of Facelinidae, Babakinidae and Aeolidiidae, but their study revealed Flabellinidae to be polyphyletic, being interspersed with taxa from the family Piseinotecidae, which has not yet been sampled for phylogenomic data. Hence, broader taxon sampling will be necessary to better understand the specificity of these evolutionary relationships within Aeolidida.

Though this study supports some previous hypotheses and provides new support for others, more work remains to be done. It is critical for future studies to increase taxon sampling. These analyses represent only 10 of the 32 families and 17 of the over 100 genera from Cladobranchia that are accepted in the World Register of Marine Species [78]. It will be especially important to include taxa from Arminida, which would allow for a more complete evaluation of the placement of families with uncertain affinities. Additionally, a representative from Doridoxidae would allow for evaluation of the placement of Doridoxa within Cladobranchia [20], for which existing molecular data yield inconsistent results [21]. Overall, an increase in the number of genera and families represented in these analyses will allow for a more complete hypothesis regarding the evolutionary history of Cladobranchia, which will in turn allow for assessments of character evolution through detailed comparative analysis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Constance Gramlich at San Diego State University (SDSU), Craig Hoover at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (CPP), Jermaine Mahguib at Iowa State University, Ariane Dimitris and José Victor Lopez at Nova Southeastern University for assistance with specimen collection. We also thank Nathan Robinette at SDSU and Emma Ransome and Vanessa Gonzalez at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (SI-NMNH) for help with RNA extractions. Finally, we are grateful to Ángel Valdés at CPP and Forest Rohwer at SDSU for the use of their laboratory facilities for specimen processing. Portions of the laboratory work were also conducted in, and with the support of, the L.A.B. facilities of the National Museum of Natural History.

Ethics

Specimen collection was conducted under the auspices of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (Scientific Collecting Permit no. SC-13009) and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (Special Activity Licence no. SAL-14-1565-SR).

Data accessibility

Transcriptomes can be accessed at the SRA at NCBI: SRA accession nos. SRR1950939–SRR1950954. Aligned data matrices and the GASTRO50 custom substitution matrix are included as the electronic supplementary material to this paper.

Author' contributions

J.A.G. conceived the study, collected samples and field data, and carried out the molecular laboratory work; J.A.G. and A.L.B. performed the bioinformatics analyses; all authors participated in study design and data analysis, helped draft the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Conchologists of America, the Society of Systematic Biologists, a University of Maryland Graduate School Dean's Fellowship to J.A.G., a Smithsonian Institution Small Grant award to A.G.C., funding from University of Maryland to M.P.C., and NSF Partnerships for International Research and Education program Award 1243541.

References

- 1.Putz A, König GM, Wägele H. 2010. Defensive strategies of Cladobranchia (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia). Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 1386–1402. (doi:10.1039/b923849m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wägele H, Klussmann-Kolb A. 2005. Opisthobranchia (Mollusca, Gastropoda)—more than just slimy slugs. Shell reduction and its implications on defence and foraging. Front. Zool. 2, 3 (doi:10.1186/1742-9994-2-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putz A, Kehraus S, Díaz-Agras G, Wägele H, König GM. 2011. Dotofide, a guanidine-interrupted terpenoid from the marine slug Doto pinnatifida (Gastropoda, Nudibranchia). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3733–3737. (doi:10.1002/ejoc.201100347) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul VJ, Ritson-Williams R. 2008. Marine chemical ecology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25, 662–695. (doi:10.1039/b702742g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tullrot A. 1994. The evolution of unpalatability and warning coloration in soft-bodied marine invertebrates. Evolution 48, 925–928. (doi:10.2307/2410499) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood PG. 2009. Acquisition and use of nematocysts by cnidarian predators. Toxicon 54, 1065–1070. (doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radjasa OK, Vaske YM, Navarro G, Vervoort HC, Tenney K, Linington RG, Crews P. 2011. Highlights of marine invertebrate-derived biosynthetic products: their biomedical potential and possible production by microbial associants. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19, 6658–6674. (doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer AMS. et al 2010. The odyssey of marine pharmaceuticals: a current pipeline perspective. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 255–265. (doi:10.1016/j.tips.2010.02.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha RK, Zi-rong X. 2004. Biomedical compounds from marine organisms. Mar. Drugs 2, 123–146. (doi:10.3390/md203123) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newcomb JM, Sakurai A, Lillvis JL, Gunaratne CA, Katz PS. 2012. Homology and homoplasy of swimming behaviors and neural circuits in the Nudipleura (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10 669–10 676. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1201877109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pola M, Gosliner TM. 2010. The first molecular phylogeny of cladobranchian opisthobranchs (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Nudibranchia). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 931–941. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodheart J, Bazinet A, Collins A, Cummings M. 2015. Phylogeny of Cladobranchia (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia): a total evidence analysis using DNA sequence data from public databases. Digit. Repos. Univ. Maryl. 35, 1–35. See http://hdl.handle.net/1903/16863. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCBI Resource Coordinators. 2013. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D8–D20. (doi:10.1093/nar/gks1189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouchet P, Rocroi JP. 2005. Classification and nomenclature of gastropod families. Malacologia 47, 1–397. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wollscheid E, Wägele H. 1999. Initial results on the molecular phylogeny of the Nudibranchia (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia) based on 18S rDNA data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 13, 215–226. (doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0664) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wollscheid-Lengeling E, Boore J, Brown W, Wägele H. 2001. The phylogeny of Nudibranchia (Opisthobranchia, Gastropoda, Mollusca) reconstructed by three molecular markers. Org. Divers. Evol. 1, 241–256. (doi:10.1078/1439-6092-00022) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thollesson M. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Euthyneura (Gastropoda) by means of the 16S rRNA gene: use of a ‘fast’ gene for ‘higher-level’ phylogenies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 75–83. (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0606) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wägele H, Willan RC. 2000. Phylogeny of the Nudibranchia. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 130, 83–181. (doi:10.1006/zjls) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wägele H, Klussmann-Kolb A, Verbeek E, Schrödl M. 2013. Flashback and foreshadowing—a review of the taxon Opisthobranchia. Org. Divers. Evol. 14, 133–149. (doi:10.1007/s13127-013-0151-5) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahguib J, Valdés Á. 2015. Molecular investigation of the phylogenetic position of the polar nudibranch Doridoxa (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia). Polar Biol. 38, 1369–1377. (doi:10.1007/s00300-015-1700-5) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrödl M, Wägele H, Willan RC. 2001. Taxonomic redescription of the Doridoxidae (Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia), an enigmatic family of deep water nudibranchs, with discussion of basal nudibranch phylogeny. Zool. Anz. 240, 83–97. (doi:10.1078/0044-5231-00008) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL. 2013. A tale that morphology fails to tell: a molecular phylogeny of Aeolidiidae (Aeolidida, Nudibranchia, Gastropoda). PLoS ONE 8, e63000 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gosliner TM, Fahey SJ. 2011. Previously undocumented diversity and abundance of cryptic species: a phylogenetic analysis of Indo-Pacific Arminidae Rafinesque, 1814 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia) with descriptions of 20 new species of Dermatobranchus. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 245–356. (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00649.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolb A, Wägele H. 1998. On the phylogeny of the Arminidae (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia, Nudibranchia) with considerations of biogeography. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 36, 53–64. (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1998.tb00777.x) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pola M, Rudman WB, Gosliner TM. 2009. Systematics and preliminary phylogeny of Bornellidae (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Dendronotina) based on morphological characters with description of four new species. Zootaxa 1975, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valdés Á, Campillo OA. 2004. Systematics of pelagic aeolid nudibranchs of the family Glaucidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda). Bull. Mar. Sci. 75, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pola M, Camacho-García YE, Gosliner TM. 2012. Molecular data illuminate cryptic nudibranch species: the evolution of the Scyllaeidae (Nudibranchia: Dendronotina) with a revision of Notobryon. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 165, 311–336. (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00816.x) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertsch H, Valdés Á, Gosliner TM. 2009. A new species of Tritoniid nudibranch, the first found feeding on a zoanthid Anthozoan, with a preliminary phylogeny of the Tritoniidae. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 60, 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmona L, Bhave V, Salunkhe R, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL. 2014. Systematic review of Anteaeolidiella (Mollusca, Nudibranchia, Aeolidiidae) based on morphological and molecular data, with a description of three new species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 171, 108–132. (doi:10.1111/zoj.12129) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmona L, Gosliner TM, Pola M, Cervera JL. 2011. A molecular approach to the phylogenetic status of the aeolid genus Babakina Roller, 1973 (Nudibranchia). J. Molluscan Stud. 77, 417–422. (doi:10.1093/mollus/eyr029) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gosliner TM, González-Duarte MM, Cervera JL. 2007. Revision of the systematics of Babakina Roller, 1973 (Mollusca: Opisthobranchia) with the description of a new species and a phylogenetic analysis. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 151, 671–689. (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00331.x) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL. 2014. The Atlantic-Mediterranean genus Berghia Trinchese, 1877 (Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae): taxonomic review and phylogenetic analysis. J. Molluscan Stud. 80, 1–17. (doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu031) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL. 2015. Burnaia Miller, 2001 (Gastropoda, Heterobranchia, Nudibranchia): a facelinid genus with an Aeolidiidae's outward appearance. Helgol. Mar. Res. 69, 285–291. (doi:10.1007/s10152-015-0437-4) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stout CC, Pola M, Valdes A. 2010. Phylogenetic analysis of Dendronotus nudibranchs with emphasis on northeastern Pacific species. J. Molluscan Stud. 76, 367–375. (doi:10.1093/mollus/eyq022) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stout CC, Wilson NG, Valdés Á. 2011. A new species of deep-sea Dendronotus Alder & Hancock (Mollusca: Nudibranchia) from California, with an expanded phylogeny of the genus. Invertebr. Syst. 25, 60 (doi:10.1071/IS10027) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekimova I, Korshunova T, Schepetov D, Neretina T, Sanamyan N, Martynov A. 2015. Integrative systematics of northern and Arctic nudibranchs of the genus Dendronotus (Mollusca, Gastropoda), with descriptions of three new species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 173, 841–886. (doi:10.1111/zoj.12214) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL. 2013. The end of a long controversy: systematics of the genus Limenandra (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Helgol. Mar. Res. 68, 37–48. (doi:10.1007/s10152-013-0367-y) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gosliner TM, Smith VG. 2003. Systematic review and phylogenetic analysis of the nudibranch genus Melibe (Opisthobranchia: Dendronotacea) with descriptions of three new species. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 54, 302–355. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore E, Gosliner T. 2014. Additions to the genus Phyllodesmium, with a phylogenetic analysis and its implications to the evolution of symbiosis. Veliger 51, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore EJ, Gosliner TM. 2011. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of symbiosis in a clade of Indopacific nudibranchs. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 58, 116–123. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carmona L, Lei BR, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Valdés Á, Cervera JL. 2014. Untangling the Spurilla neapolitana (Delle Chiaje, 1841) species complex: a review of the genus Spurilla Bergh, 1864 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 170, 132–154. (doi:10.1111/zoj.12098) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valdés A, Hamman J, Behrens D, DuPont A. 2006. Caribbean sea slugs, 1st edn Gig Harbor, WA: Sea Challengers Natural History Books. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behrens DW, Hermosillo A. 2005. Eastern Pacific nudibranchs: a guide to the opisthobranchs from Alaska to Central America, 2nd edn Gig Harbor, WA: Sea Challengers Natural History Books. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shuttleworth R. 2013. autoadapt—Automatic quality control for FASTQ sequencing files. See https://github.com/optimuscoprime/autoadapt.

- 45.Andrews S. 2010. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. See http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- 46.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10 (doi:10.14806/ej.17.1.200) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grabherr MG. et al 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. (doi:10.1038/nbt.1883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ebersberger I, Strauss S, von Haeseler A. 2009. HaMStR: profile hidden Markov model based search for orthologs in ESTs. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 157 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-157) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson WR, Lipman DJ. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 2444–2448. (doi:10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. 2004. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995. (doi:10.1101/gr.1865504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eddy SR. 2011. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. (doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bairoch A. et al 2005. The universal protein resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 154–159. (doi:10.1093/nar/gki070) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemaitre C, Barré A, Citti C, Tardy F, Thiaucourt F, Sirand-Pugnet P, Thébault P. 2011. A novel substitution matrix fitted to the compositional bias in Mollicutes improves the prediction of homologous relationships. BMC Bioinform. 12, 457 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-12-457) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mst010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zwickl DJ. 2006. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. PhD dissertation University of Texas at Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kocot KM, Halanych KM, Krug PJ. 2013. Phylogenomics supports Panpulmonata: opisthobranch paraphyly and key evolutionary steps in a major radiation of gastropod molluscs. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 764–771. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bazinet AL, Cummings MP, Mitter KT, Mitter CW. 2013. Can RNA-Seq resolve the rapid radiation of advanced moths and butterflies (Hexapoda: Lepidoptera: Apoditrysia)? An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 8, e82615 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082615) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zwick A, Regier JC, Zwickl DJ. 2012. Resolving discrepancy between nucleotides and amino acids in deep-level Arthropod phylogenomics: differentiating serine codons in 21-amino-acid models. PLoS ONE 7, e47450 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047450) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Regier JC. et al. 2013. A large-scale, higher-level, molecular phylogenetic study of the insect order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). PLoS ONE 8, e58568 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058568) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bazinet AL, Zwickl DJ, Cummings MP. 2014. A gateway for phylogenetic analysis powered by grid computing featuring GARLI 2.0. Syst. Biol. 63, 812–818. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tavaré S. 1986. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect. Math. Life Sci. 17, 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sukumaran J, Holder MT. 2010. DendroPy: a Python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics 26, 1569–1571. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.R Development Core Team. 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zapata F, Wilson NG, Howison M, Andrade SCS, Jörger KM, Schrödl M, Goetz FE, Giribet G, Dunn CW. 2014. Phylogenomic analyses of deep gastropod relationships reject Orthogastropoda. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20141739 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1739) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simmons MP. 2012. Misleading results of likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses in the presence of missing data. Cladistics 28, 208–222. (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00375.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cho S. et al 2011. Can deliberately incomplete gene sample augmentation improve a phylogeny estimate for the advanced moths and butterflies (Hexapoda: Lepidoptera)? Syst. Biol. 60, 782–796. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr079) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiens JJ, Fetzner JW, Parkinson CL, Reeder TW. 2005. Hylid frog phylogeny and sampling strategies for speciose clades. Syst. Biol. 54, 778–807. (doi:10.1080/10635150500234625) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burleigh JG, Hilu KW, Soltis DE. 2009. Inferring phylogenies with incomplete data sets: a 5-gene, 567-taxon analysis of angiosperms. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 61 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-61) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Philippe H, Snell EA, Bapteste E, Lopez P, Holland PWH, Casane D. 2004. Phylogenomics of eukaryotes: Impact of missing data on large alignments. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1740–1752. (doi:10.1093/molbev/msh182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wiens JJ, Morrill MC. 2011. Missing data in phylogenetic analysis: reconciling results from simulations and empirical data. Syst. Biol. 60, 719–731. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salichos L, Rokas A. 2013. Inferring ancient divergences requires genes with strong phylogenetic signals. Nature 497, 327–331. (doi:10.1038/nature12130) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dell'Ampio E. et al 2014. Decisive data sets in phylogenomics: lessons from studies on the phylogenetic relationships of primarily wingless insects. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 239–249. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mst196) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simmons MP, Norton AP. 2014. Divergent maximum-likelihood-branch-support values for polytomies. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 73, 87–96. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.01.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Betancur R, Naylor GJP, Ortí G. 2014. Conserved genes, sampling error, and phylogenomic inference. Syst. Biol. 63, 257–262. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syt073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Espinoza E, Dupont A, Valdés Á. 2013. A tropical Atlantic species of Melibe Rang, 1829 (Mollusca, Nudibranchia, Tethyiidae). Zookeys 66, 55–66. (doi:10.3897/zookeys.316.5452) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kück P, Mayer C, Wägele JW, Misof B. 2012. Long branch effects distort maximum likelihood phylogenies in simulations despite selection of the correct model. PLoS ONE 7, e36593 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036593) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.WoRMS Editorial Board. 2015. World Register of Marine Species. See http://www.marinespecies.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Transcriptomes can be accessed at the SRA at NCBI: SRA accession nos. SRR1950939–SRR1950954. Aligned data matrices and the GASTRO50 custom substitution matrix are included as the electronic supplementary material to this paper.