Abstract

Background:

It has been reported that high intensity long term training in elite athletes may increase risk of immune function.

Objectives:

This study is to examine training effects on immunoglobulin and changes of physiological stress and physical fitness level induced by increased cold stress during 12-week winter off-season training in elite Judoists.

Patients and Methods:

Twenty-nine male participants (20 ± 1 years) were assigned to only Judo training (CG, n = 9), resistance training combined with Judo training (RJ, n = 10), and interval training combined with Judo training (IJ, n = 10). Blood samples collected at rest, immediately after all-out exercise, and 30-minute recovery period were analyzed for testing IgA, IgG, and IgM, albumin and catecholamine levels.

Results:

VO2max and anaerobic mean power in IJ (P < 0.05) and anaerobic power in RJ (P < 0.05) were significantly increased after 12-week training compared to CG. There was no significant interaction effect (group × period) in albumin after 12-week training; however, there was a significant interaction effect (group × period) in epinephrine after 12-week training (F (4, 52) = 3.216, P = 0.002) and immediately after all-out exercise and at 30-minute recovery (F (2, 26) = 14.564, P = 0.008). There was significantly higher changes in epinephrine of RJ compared to IJ at 30-minute recovery (P = 0.045). There was a significant interaction effect (group × period) in norepinephrine after 12-week training (F (4, 52) = 8.141, P < 0.0001), at rest and immediately after all-out exercise (F (2, 26) = 9.570, P = 0.001), and immediately after all-out exercise and at 30-minute recovery (F (2, 26) = 8.862, P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

Winter off-season training of IJ increased physical fitness level as well as physical stress induced by overtraining. Along with increased physical stress, all groups showed reduced trend of IgA; however, there was no group difference based on different training methods.

Keywords: Immunoglobulins, Training, Physical Fitness

1. Background

It has been reported that vigorous exercise and training cause immune function changes such as biphasic alteration of circulating immune cell numbers in marathoners (1) and athletes (2), a reduced phagocytic activity in Judoists (3), a reduced Salivary immunoglobulin A (IgA) secretion in marathoners (4), and elevated oxidative burst activity in Judoists (5). Especially, it has been reported that high intensity long term training in elite athletes may increase risk of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) (6) and cause overtraining syndrome such as persistent fatigue, poor performance, mood state changes, and reduced catecholamine excretion (7).

Circulating immunoglobulins are glycoprotein molecules that are produced by plasma cells in response to an immunogen and are responsible for targeting and eradicating foreign bacteria and viruses (8). Immunoglobulin isotypes are named by capital letters corresponding to their heavy chain type. IgG is capable of carrying out all of the functions of Ig molecules and is the major Ig in serum and the most important antibody component (2). IgA and IgM are the antibodies related to exercise (9). However, previous studies concerning well-trained athletes and/or exercise investigated changes in Ig responses are still not in agreement. No Ig response change (10), an increased Ig response (11) and a decreased Ig response (12), and a suppressed immune response(12) were investigated.

For over 30 years, Korean Judoists have received high intensity training to enhance athletic performance during season (March to November) (13), to maintain fat free mass in winter off-season training period (December to February), and to increase aerobic and anaerobic performance. Moreover, most university Judoists in Korea performed scheduled training such as 2-time fitness training at 06:00 - 07:30 and 10:00 - 11:30, Judo training at 15:00 - 16:30, and resistance training at 19:00 - 20:30 at least 6 hours per day and 5 days per week during 12-week winter off-season, living in the same dormitory (13). Considering training volume, intensity, and period, it is expected that Korean Judoists might have frequent illness change such as URTI induced by overtraining (7, 14). Although previous studies considered that URTI incidence would be higher in athletes during on-season compared to off-season, it would be assumed that there would be differences in competition times and match methods during on-season. Moreover, previous studies focused on middle and long distance runners having more exercise time, volume, and intensity during on-season competition than off-season. Thus, they concluded that URTI incidence would be higher in athletes and URTI J curve has been modeled during on-season (7). However, it is still not clear how the mechanism of immunomodulation is induced by winter off season outdoor training.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study is to examine training effects on immunoglobulin and physiological stress changes and physical fitness level changes induced by increased cold stress during winter off-season training in elite Judoists.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

This is a randomized control trial study with 12-week duration. Dependent variables in this study are level of serum albumin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, serum IgA, IgG, and IgM at rest, immediately after all-out exercise, and recovery. Independent variables are exercise intervention (control group only with Judo training, resistance training group combined with Judo training, and interval training group combined with Judo training) in each group. All experimental measurements were completed at approximately the same time of day in each measurement day. Subjects were instructed to maintain their normal diet throughout the testing period, to avoid food and drink in the hour before testing, and to avoid strenuous exercise 24 hours before each measurement. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects under protocols approved by the institutional review boards of Yongin University.

3.2. Subjects

Twenty-nine Judoists from the Yongin University Judo team participated in this study during winter off-season (12 weeks). All participants were well trained college-aged males (20 ± 1 years) and they were Korean National Championship medalists or had practiced at the senior or junior international level for the past 12 months. All participants were assigned to 3 groups; control group only with Judo training (CG, n = 9), resistance training group combined with Judo training (RJ, n = 10), and interval training group combined with Judo training (IJ, n = 10). All participants lived in the same dormitory consuming controlled and supervised food intake by 3,800 kcal ± 15% per day during training session. Before participating in this study, Judoists having recent 3-month injury experience and disease related to immune function were excluded.

3.3. Procedures

All participants performed pre-intervention measures including: 1) maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) test; 2) lower limb Wingate anaerobic power test; 3) 8 hours fasting venous blood sample draw at rest, immediately after Judo match, and recovery 15 and 30 minute; and 4) height, weight, and percent body fat (% fat). Maximal oxygen uptake was tested on a motor-driven treadmill using the Bruce protocol. It was measured with standard open-circuit spirometry techniques (Quark b2 metabolic cart, Cosmed, Italy) and electrocardiograms were measured with an EKG monitor (QMC2500; Quinton, USA). All participants were encouraged to exercise to volitional exhaustion during the test. Requirements to strictly define whether subjects reached their VO2max by this protocol included at least two of the following criteria (1); a leveling of the VO2 after an increase in intensity, (2) rate of perceived exertion > 17 using Borg’s scale (3), volitional exhaustion, and (4) achievement of age-predicted maximal heart rate.

Participants performed a 30-second Wingate anaerobic power test to measure peak and mean anaerobic power, both which are considered vital during the tsukuri (positioning) and kake (execution) phase of Judo throwing. To test the difference in anaerobic power among the groups as well as correlations between anaerobic power and body composition, a computer-aided electrically braked cycle ergometer was used (excalibur sports, Lode B.V., The Netherlands). For the Wingate protocol, participants warmed up for 10 minutes at 60 rpm and 100 Watt so that their heart rate was maintained at 120 - 125 beat/minute, with an additional 5-minute warm-up after 5-minute rest (13). Then, breaking resistance was set as 0.8 Nm·kg-1 of body mass. Participants continued pedaling as fast as possible against the resistance for 30 seconds. After the sprint, the resistance was removed and they continued cycling for 4 minutes of active recovery. The entire measuring procedure was controlled by a computer using Lode Wingate Version 1.0.7 (Lode B.V.). Body composition was measured in duplicate by the DSM-BIA method using In-Body 3.0 (Biospace, Seoul, Korea). This indirect method uses 6 analysis frequencies (1, 5, 50, 250, 500, and 1,000 kHz) and analyzes fat free mass (FFM) and fat mass (FM) by using the tetra-polar 8-point tactile electrode method (15).

During the 12-week off-training period, CG, RJ, and IJ participated in the standardized winter off-season training program. The standard Judo training for all three groups was conducted at 2:30 - 4:30 pm. from Monday to Friday for 10 hours per week including attacking or defending by using the 4 limbs (arms, hands, legs, and feet). With standard Judo training, RJ performed 6 h. wk-1 of resistance training on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday at 6:00 - 7:30 am. Each resistance training set was consisted of 12 repetitions with 2 sets (1 - 2 training weeks), 3 sets (3 - 8 training weeks) and 4 sets (9 - 12 training weeks). Resistance training intensity was set as 70% of 1 RM (one repetition maximum) until 2 weeks and 80% of 1RM after 3 weeks being conducted on Monday and Tuesday (leg curl, leg dead lift, and cable one leg curl), and Thursday and Friday (squat, leg extension, leg press, and lunge). One RM was measured every 2 weeks to revise maximum strength. With standard Judo training, IJ performed 6 hours. wk-1 of interval training at 6:00 - 7:30 am. on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Interval training was consisted of 30 seconds maximal running efforts with a 4 minutes warm-up period and 4 minutes of recovery between the sprint bouts, respectively. Each sprint was completed on a treadmill (Healma 7700, Healma®, Seoul, Korea) by dynamic mode. The number of bouts increased from 6 (weeks 1, 2) to 8 (weeks 3 - 8) and to 10 (weeks 9 - 12) per training session. Intensive interval training was conducted at 80% maximal aerobic velocity (MAV), which was determined via VO2max test during first 2 weeks and at 90% MAV from week 3 to week 12.

Antecubital venous blood samples (10 mL) were obtained at rest, immediately after all-out exercise using graded exercise test, and 30 minutes of recovery at baseline and after 12-week training. Blood was drawn into Heparin tubes (Becton Dickson Co.) and was immediately centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 2000 rpm. Plasma was aliquoted and stored in 80°F until later analysis. Serum immunoglobulin levels were determined by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Bio Med, Micro plate 680, USA). Epinephrine and norepinephrine concentrations were assayed by high-pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical (amperometric) detection (16). Nutrional risk index is calculated using the following equation: NRI = 1.519 × serum albumin (g/dL) + 41.7 (present/usual body weight (kg)) (17).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means and standard deviations. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze trends of participant characteristics, baseline of serum blood factors, and nutritional risk index. Group differences in body composition and aerobic and anaerobic power changes followed by 12-week training were analyzed by two-way mixed (group × period) ANOVA and one-way ANOVA was used to consider baseline error with using delta value (after 12-week training difference from baseline). Bonferroni method was used to test group difference. Data were analyzed with SPSS 16.0 for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA) and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all tests.

4. Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of participants in this study. Mean age of CG, RJ, and IJ was 19.67 ± 1.02 years, 20.30 ± 1.25 years, and 19.90 ± 1.10 years, respectively. There was no significant group difference in height, body mass index (BMI), and exercise career. Epinephrine at rest and immediately after all-out exercise showed a significantly lower trend in RJ and IJ compared to CG and IgG at immediately after all-out exercise showed a significantly lower trend in RJ and IJ compared to CG (P < 0.05) (Table 2). However, there was no significant group difference in albumin, norepinephrine, IgA, IgM, and nutritional risk index (Figure 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants a.

| Variables | Control Group Only With Judo Training (CG; n = 9) | Resistance Training With Judo Training (RJ; n = 10) | Interval Training With Judo Training Group (IJ; n = 10) | P Value for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 19.67 ± 1.02 | 20.30 ± 1.25 | 19.90 ± 1.10 | 0.5 |

| Height, cm | 174.56 ± 8.63 | 171.80 ± 5.69 | 172.30 ± 5.89 | 0.7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 | 25.37 ± 1.22 | 25.19 ± 2.14 | 24.89 ± 2.06 | 0.9 |

| Exercise career, y | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 7.8 ± 2.1 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 0.9 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 2. Baseline of Serum Level on Blood Factors a.

| Variables | Control Group Only With Judo Training (CG; n = 9) | Resistance Training With Judo Training (RJ; n = 10) | Interval Training With Judo Training Group (IJ; n = 10) | P Value for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin, g/L | ||||

| Rest | 27.92 ± 6.01 | 27.24 ± 3.54 | 28.44 ± 2.56 | 0.8 |

| Immediately after exercise | 59.12 ± 8.18 | 57.50 ± 7.37 | 57.25 ± 6.61 | 0.1 |

| 30-minute recovery | 42.20 ± 7.65 | 43.06 ± 5.85 | 42.85 ± 12.01 | 0.7 |

| Epinephrine, nmol/L | ||||

| Rest | 4.90 ± 0.06 | 4.51 ± 0.05 b | 4.88 ± 0.03 c | < 0.0001 |

| Immediately after exercise | 24.54 ± 1.49 | 23.08 ± 4.24 b | 22.56 ± 1.14 c | 0.008 |

| 30-minute recovery | 5.78 ± 0.18 | 5.70 ± 5.53 | 5.59 ± 0.33 | 0.08 |

| Norepinephrine, nmol/L | ||||

| Rest | 16.47 ± 3.26 | 16.14 ± 2.17 | 17.12 ± 1.54 | 0.9 |

| Immediately after exercise | 87.27 ± 18.01 | 101.42 ± 11.74 | 102.45 ± 24.41 | 0.08 |

| 30-minute recovery | 54.61 ± 17.63 | 48.87 ± 8.35 | 48.62 ± 9.49 | 0.5 |

| Immunoglobulin A, g/L | ||||

| Rest | 1.89 ± 0.20 | 1.96 ± 0.26 | 2.02 ± 0.24 | 0.5 |

| Immediately after exercise | 1.71 ± 0.29 | 1.66 ± 0.21 | 1.69 ± 0.21 | 0.9 |

| 30-minute recovery | 1.61 ± 0.28 | 1.52 ± 0.29 | 1.39 ± 0.22 | 0.2 |

| Immunoglobulin G, g/L | ||||

| Rest | 9.12 ± 0.22 | 9.06 ± 0.24 | 9.03 ± 0.32 | 0.7 |

| Immediately after exercise | 9.06 ± 0.18 | 8.83 ± 0.18 b | 8.87 ± 0.19 c | 0.03 |

| 30-minute recovery | 8.94 ± 0.21 | 8.71 ± 0.30 | 8.81 ± 0.26 | |

| Immunoglobulin M, g/L | ||||

| Rest | 9.11 ± 0.23 | 9.05 ± 0.24 | 9.15 ± 0.32 | 0.6 |

| Immediately after exercise | 9.16 ± 0.32 | 9.06 ± 0.18 | 8.87 ± 0.19 | 0.07 |

| 30-minute recovery | 8.90 ± 0.21 | 9.04 ± 0.29 | 8.91 ± 0.26 | 0.5 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b Control group compared with resistance training with Judo training group.

c Control group compared with interval training with Judo training group.

Figure 1. Delta Values (Baseline and After 12-Week Training Difference) of Serum Albumin, Epinephrine, and Norepinephrine at Rest, Immediately After All-Out Exercise, and Recovery. †, CG and IJ were compared; ‡, RJ and IJ were compared.

Changes in body composition, aerobic performance, and anaerobic power at baseline and after 12-week training are presented in Table 3. After 12-week training, there was a significant decrease in body weight (P = 0.003), % fat (P = 0.009), VO2max (P = 0.03), and HRmax (P = 0.01) of IJ compared to CG. Otherwise, there were no significant changes in % fat, VO2max, and HRmax of RJ compared to CG after 12-week training. There was a significant increase in anaerobic peak power of RJ compared to CG (P = 0.03). However, there was a significant increase in mean power of RJ (P = 0.03) and IJ (P = 0.001) compared to CG after 12-week training and there was no significant group difference in RJ and IJ.

Table 3. Changes in Body Composition, Aerobic Power, and Anaerobic Power at Baseline and After 12-Week Training a,b.

| Variable | Control Group Only With Judo Training | Resistance Training With Judo Training | Interval Training With Judo Training Group | P Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After 12-Week Training | Delta (Post-Pre) | Baseline | After 12-Week Training | Delta (Post-Pre) | Baseline | After 12-Week Training | Delta (Post-Pre) | ||

| Weight, kg | 77.56 ± 11.05 | 77.63 ± 12.18 | -0.12 ± 1.30 | 74.58 ± 9.32 | 72.59 ± 9.05 | -0.99 ± 0.51 | 73.94 ± 7.41 | 71.15 ± 7.92 | -1.79 ± 1.34 c | 0.011 |

| Percent body fat, % | 13.36 ± 1.36 | 13.28 ± 1.01 | -0.08 ± 0.75 | 12.97 ± 2.09 | 12.27 ± 1.71 | -0.69 ± 0.60 | 13.31 ± 2.82 | 12.27 ± 2.57 | -1.04 ± 0.86 c | 0.03 |

| VO 2 max, mL/kg/min | 46.56 ± 2.62 | 48.74 ± 2.61 | 2.18 ± 1.83 | 46.95 ± 6.45 | 49.88 ± 5.49 | 2.93 ± 1.92 | 49.88 ± 4.30 | 54.39 ± 4.32 | 4.50 ± 2.78 c | 0.085 |

| HRmax, beat/min | 180.02 ± 7.81 | 178.67 ± 7.58 | -1.33 ± 2.65 | 180.20 ± 5.37 | 178.90 ± 5.83 | -1.30 ± 2.67 | 180.70 ± 1.34 | 176.10 ± 2.23 | -4.60 ± 2.91 c | 0.018 |

| Anaerobic peak power | 12.40 ± 2.14 | 13.19 ± 2.13 | 0.78 ± 1.08 | 13.23 ± 1.48 | 15.07 ± 1.32 | 1.84 ± 1.13 d | 12.9 ± 1.35 | 14.42 ± 1.15 | 1.61 ± 0.71 | 0.07 |

| Anaerobic mean power | 9.41 ± 1.86 | 9.44 ± 1.86 | 0.04 ± 1.40 | 9.13 ± 1.43 | 11.17 ± 2.92 | 2.04 ± 2.72 d | 9.52 ± 1.11 | 13.02 ± 1.77 | 3.48 ± 1.31 c | 0.003 |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b Abbreviations: G, group; T, time (pre and post); X, interaction; GxT, interaction between group and time.

c Control group compared with interval training with Judo training group.

d Control group compared with resistance training with Judo training group.

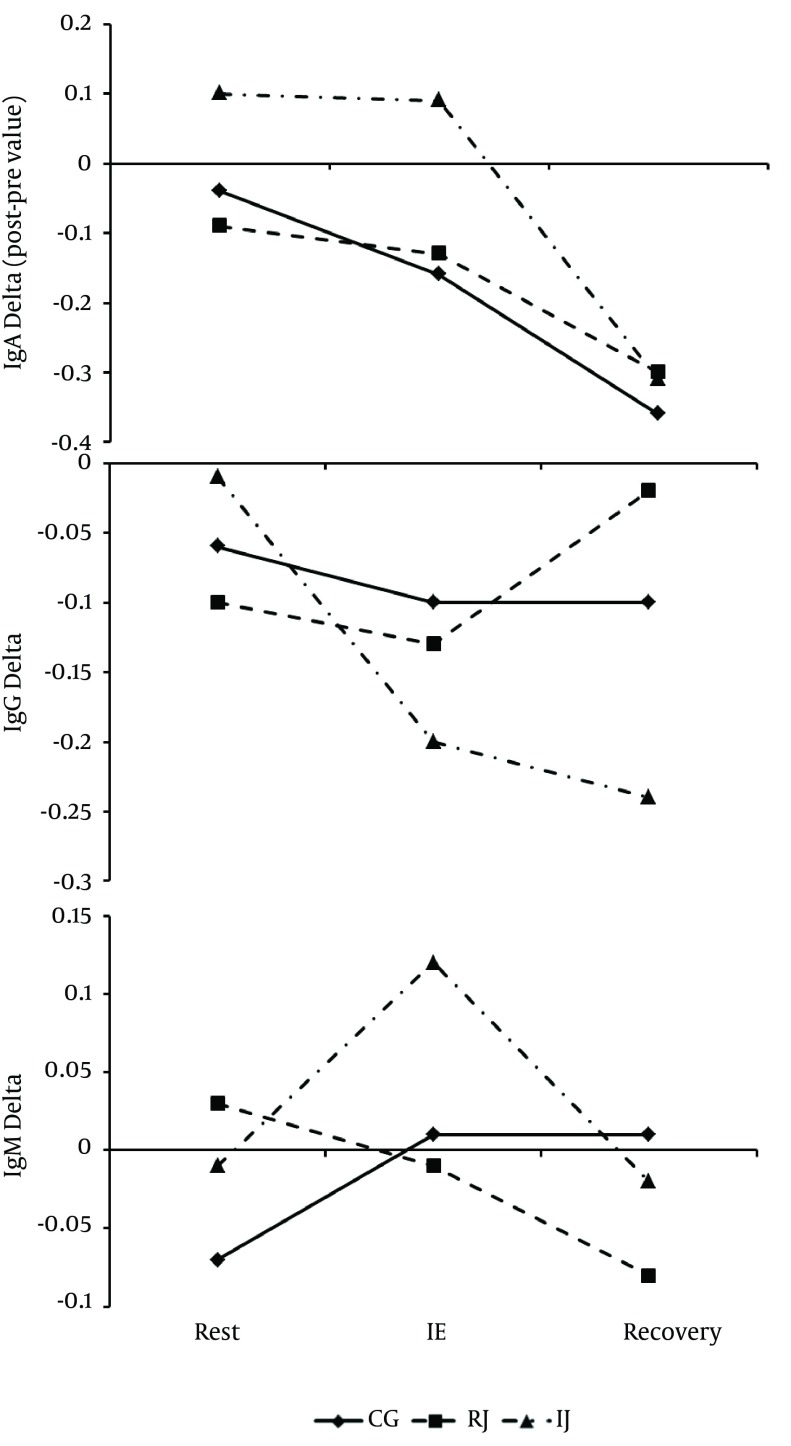

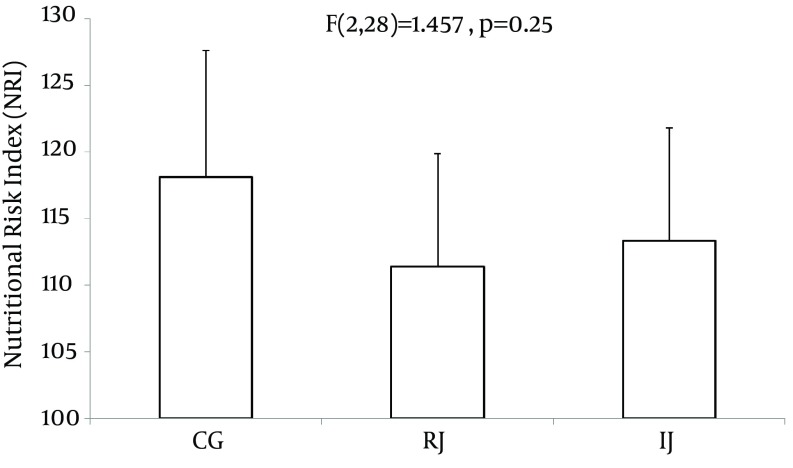

There was a significant interaction effect (group × period) in weight (P = 0.011), % fat (P = 0.03), HRmax (P = 0.018), and anaerobic mean power (P = 0.003). However, there was no significant interaction effect (group × period) in VO2max and anaerobic peak power. There was no significant interaction effect (group × period) in albumin after 12-week training; however, there was a significant interaction effect (group × period) in epinephrine after 12-week training (F (4, 52) = 3.216, P = 0.002) and immediately after all-out exercise and at 30-minute recovery (F (2, 26) = 14.564, P = 0.008). There was significantly higher changes in epinephrine of RJ compared to IJ at 30-minute recovery (P = 0.045). There was a significant interaction effect (group × period) in norepinephrine after 12-week training (F (4, 52) = 8.141, P < 0.0001), at rest and immediately after all-out exercise (F (2, 26) = 9.570, P = 0.001), and immediately after all-out exercise and at 30-minute recovery (F (2, 26) = 8.862, P = 0.001). There was a significant increase in group change of IJ compared to CG at rest after 12-week training (P = 0.014) and there was a significant decrease in group change of IJ compared to CG (P = 0.005) and RJ (P = 0.006) immediately after all-out exercise followed by 12-week training. There was a significant increase in group change of IJ compared to CG at 30-minute recovery followed by 12-week training (P = 0.036) (Figure 1). There was no interaction effect (group × period) in IgA, IgG, and IgM after 12-week training (Figure 2). During 12-week training period, there was no significant group difference in nutritional risk index (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Delta Values (Baseline and After 12-Week Training Difference) of Serum Immunoglobulin A, Immunoglobulin G, and Immunoglobulin M at Rest, Immediately After All-Out Exercise, and Recovery.

Figure 3. Nutritional Risk Index.

5. Discussion

The primary finding of this study was that resistance and interval training combined with Judo training influenced body composition, aerobic and anaerobic performance level, and stress hormone level changes in Judoists during winter off-season training. However, there was no significant immunoglobulin change in Judoists. Previous studies have discussed how high intensity exercise influences body composition (15) and in particular, how anaerobic power is closely correlated with fat-free mass in Judoists (e.g. brief intense muscular action) (15, 18). This study found that there was a significant change in body weight and % fat of IJ. Moreover, there was a significant increase in VO2max and anaerobic mean power of IJ and this might be highly induced by body composition and physical fitness changes followed by high intensity training. Otherwise, there was a significant anaerobic power change in RJ without any significant body composition change and this might come from muscle content change in RJ after 12-week training. Previous studies insisted that Wingate anaerobic power test is the reliable one for measuring anaerobic power in Judoists (15). However, Judoists participated in this study conducted resistance training for upper extremity, trunk, and lower extremity and Wingate anaerobic power test focusing on lower extremity might cause no significant difference in anaerobic power among groups.

Since intensive exercise has been reported to be associated with enhanced sympathetic nervous system, previous studies reported that a decrease in salivary IgA level followed by high intensity exercise (> 80% VO2max) after 1 hour recovery period (19, 20). Several studies reported that trained athletes have greater basal concentration of catecholamine compared to untrained subjects (21, 22), higher concentration of catecholamine in anaerobic trained athletes compared to aerobic trained athletes, and different response to stimuli unlike untrained ones (23). Especially, trained athletes have been known to have a ‘sports adrenal medulla’; although, aerobically and anaerobically trained Judoists might have it or not (24). This study's results showed that concentration level of epinephrine was increased in all groups immediately after all-out exercise and at 30-minute recovery and there was no difference in all groups which is the same as a previous report (24). Moreover, there was no difference in all groups at rest and immediately after all-out exercise followed by 12-week training; however, there was significant increase in RJ at 30-minute recovery compared to IJ. This compensatory mechanism might be due to decreased sensitivity of human body to beta-adrenergic stimulation in RJ (23). Concentration level of epinephrine immediately after all-out exercise in IJ was higher than RJ after 12-week training and concentration level of epinephrine at 30-minute recovery was greater than RJ. This might come from decreased sensitivity of compensatory mechanism in RJ compared to IJ. Davis et al. (25) reported that mice's alveolar macrophage antiviral resistance followed by 8-hour prolonged strenuous exercise to fatigue was inhibited by increased plasma epinephrine. In this study, it seems that increased concentration of epinephrine level after all-out exercise in RJ having low variation tuned to recovery phase might have a more negative effect on immune function compared to IJ based upon different winter off-season training methods in Judoists.

Most participants in this study might have overtraining symptoms caused by high intensity and long term winter off-season training. Especially, it is argued that overtraining symptoms have reduced nocturnal excretion of norepinephrine changes (26). However, basal norepinephrine level has been known to be increased under high intensity and long term training condition (24). Winter off-season training increased basal norepinephrine level and increased basal norepinephrine level of IJ showed a significant increase compared to CG. However, there was no difference in basal norepinephrine level of IJ and RJ and this might be due to increased stress in Judoists induced by Judo training combined with interval and resistance training.

Basal norepinephrine level of CG and RJ was increased and basal norepinephrine level of IJ was decreased after training. Otherwise, basal norepinephrine level of IJ was increased and basal norepinephrine level of RJ was decreased at 30-minute recovery. This cannot be clearly explained and this might come from body composition change in IJ. Moreover, changes of difference in circulating norepinephrine concentration and epinephrine concentration immediately after all-out exercise and 30-minute recovery might be affected by decreased plasma volume after all-out exercise because norepinephrine comprises 80% of blood catecholamine (24).

We expected that long term participation in training might cause URTI incidence change in Judoists because of reduced secretary IgA. However, there was no significant group difference at rest, immediately after all-out exercise, and 30-minute recovery. It seems that Judo training combined with resistance and interval training did not affect antibody secretion difference in Judoists. In other words, this can be explained that Judo training combined with resistance and interval training did not evoke immune system changes induced by overtraining through antibody synthesis in Judoists. Additionally, lymph flow rate stimulated by Judo training and additional training (resistance and interval training) can increase flux of different proteins into circulation (27); however, there was no lymph flow rate difference caused by additional training and therefore, there was no group difference.

There are several limitations in this study. First, most previous studies measured mucosal Ig levels; however, only serum Ig was measured in this study, which was limited to compare previous references. Second, this study population was limited to elite Judoists’ Ig level during non-season training period, and therefore this cannot be compared to Ig level due to over training during season training period. Lastly, additional Ig level and body composition during detraining period were not measured in this study. Generally, it is expected that Ig level would be higher in 1-week recovery period after long term training period. It was unable to conduct additional measurement at recovery period, considering Judoists’ competition schedule and body condition. Although there were fitness level and stress hormone changes induced by long term training, there was no Ig level change in this study. Therefore, Judoists would be safe for URTI induced by long term training during winter off-season. Also, additional dietary supplementation for Judoists considering age and fitness level would be helpful in enhancing immune function followed by intensive winter season training.

Findings of this study would be useful for Judo coaches and Judoists in order to enhance athletic performance as well as understanding immune responses followed by intensive training. This may help to clarify the benefits of resistance and interval training in elite Judoists. It would be suitable for future studies to consider additional Ig level, body composition, and fat metabolism based upon Judoists’ rapid weight loss during a short period of time.

Footnotes

Funding/Support:This study was approved by the institutional review board for human subjects’ protection at Yongin University.

References

- 1.Starkie RL, Rolland J, Angus DJ, Anderson MJ, Febbraio MA. Circulating monocytes are not the source of elevations in plasma IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels after prolonged running. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280(4):C769–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saygin O, Karacabey K, Ozmerdivenli R, Zorba E, Ilhan F, Bulut V. Effect of chronic exercise on immunoglobin, complement and leukocyte types in volleyball players and athletes. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27(1-2):271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinda D, Umeda T, Shimoyama T, Kojima A, Tanabe M, Nakaji S, et al. The acute response of neutrophil function to a bout of judo training. Luminescence. 2003;18(5):278–82. doi: 10.1002/bio.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Fagoaga OR, Utter AC, Vinci DM, Davis JM, et al. Change in salivary IgA following a competitive marathon race. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(1):69–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-19375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaegaki M, Umeda T, Takahashi I, Yamamoto Y, Kojima A, Tanabe M, et al. Measuring neutrophil functions might be a good predictive marker of overtraining in athletes. Luminescence. 2008;23(5):281–6. doi: 10.1002/bio.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKune AJ, Smith LL, Semple SJ, Wadee AA. Influence of ultra-endurance exercise on immunoglobulin isotypes and subclasses. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(9):665–70. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKinnon LT. Special feature for the Olympics: effects of exercise on the immune system: overtraining effects on immunity and performance in athletes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78(5):502–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2000.t01-7-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brolinson PG, Elliott D. Exercise and the immune system. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(3):311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi I, Umeda T, Mashiko T, Chinda D, Oyama T, Sugawara K, et al. Effects of rugby sevens matches on human neutrophil-related non-specific immunity. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(1):13–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davison G, Allgrove J, Gleeson M. Salivary antimicrobial peptides (LL-37 and alpha-defensins HNP1-3), antimicrobial and IgA responses to prolonged exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):277–84. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klentrou P, Cieslak T, MacNeil M, Vintinner A, Plyley M. Effect of moderate exercise on salivary immunoglobulin A and infection risk in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;87(2):153–8. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umeda T, Nakaji S, Shimoyama T, Kojima A, Yamamoto Y, Sugawara K. Adverse effects of energy restriction on changes in immunoglobulins and complements during weight reduction in judoists. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2004;44(3):328–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Lee N, Trilk J, Kim EJ, Kim SY, Lee M, et al. Effects of sprint interval training on elite Judoists. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32(12):929–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreira A, Delgado L, Moreira P, Haahtela T. Does exercise increase the risk of upper respiratory tract infections? Br Med Bull. 2009;90:111–31. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Cho HC, Jung HS, Yoon JD. Influence of performance level on anaerobic power and body composition in elite male judoists. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(5):1346–54. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d6d97c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willemsen JJ, Ross HA, Jacobs MC, Lenders JW, Thien T, Swinkels LM, et al. Highly sensitive and specific HPLC with fluorometric detection for determination of plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine applied to kinetic studies in humans. Clin Chem. 1995;41(10):1455–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Develioglu ON, Kucur M, Ipek HD, Celebi S, Can G, Kulekci M. Effects of Ramadan fasting on serum immunoglobulin G and M, and salivary immunoglobulin A concentrations. J Int Med Res. 2013;41(2):463–72. doi: 10.1177/0300060513476424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva AM, Fields DA, Heymsfield SB, Sardinha LB. Body composition and power changes in elite judo athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(10):737–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKinnon LT, Jenkins DG. Decreased salivary immunoglobulins after intense interval exercise before and after training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(6):678–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDowell SL, Hughes RA, Hughes RJ, Housh TJ, Johnson GO. The effect of exercise training on salivary immunoglobulin A and cortisol responses to maximal exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(8):577–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjaer M, Galbo H. Effect of physical training on the capacity to secrete epinephrine. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988;64(1):11–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kjaer M, Farrell PA, Christensen NJ, Galbo H. Increased epinephrine response and inaccurate glucoregulation in exercising athletes. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1986;61(5):1693–700. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.5.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob C, Zouhal H, Prioux J, Gratas-Delamarche A, Bentue-Ferrer D, Delamarche P. Effect of the intensity of training on catecholamine responses to supramaximal exercise in endurance-trained men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(1):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-1002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zouhal H, Jacob C, Delamarche P, Gratas-Delamarche A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med. 2008;38(5):401–23. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis JM, Kohut ML, Colbert LH, Jackson DA, Ghaffar A, Mayer EP. Exercise, alveolar macrophage function, and susceptibility to respiratory infection. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1997;83(5):1461–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehmann M, Schnee W, Scheu R, Stockhausen W, Bachl N. Decreased nocturnal catecholamine excretion: parameter for an overtraining syndrome in athletes? Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(3):236–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedfors E, Holm G, Ivansen M, Wahren J. Physiological variation of blood lymphocyte reactivity: T-cell subsets, immunoglobulin production, and mixed-lymphocyte reactivity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1983;27(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]