Abstract

General anesthetics achieve behavioral unresponsiveness via a mechanism that is incompletely understood. The study of genetic model systems such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is crucial to advancing our understanding of how anesthetic drugs render animals unresponsive. Previous studies have shown that wild-type control strains differ significantly in their sensitivity to general anesthetics, which potentially introduces confounding factors for comparing genetic mutations placed on these wild-type backgrounds. Here, we examined a variety of behavioral and electrophysiological endpoints in Drosophila, in both adult and larval animals. We characterized these endpoints in 3 commonly used fly strains: wild-type Canton Special (CS), and 2 commonly used white-eyed strains, isoCJ1 and w1118. We found that CS and isoCJ1 show remarkably similar sensitivity to isoflurane across a variety of behavioral and electrophysiological endpoints. In contrast, w1118 is resistant to isoflurane compared to the other 2 strains at both the adult and larval stages. This resistance is however not reflected at the level of neurotransmitter release at the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ). This suggests that the w1118 strain harbors another mutation that produces isoflurane resistance, by acting on an arousal pathway that is most likely preserved between larval and adult brains. This mutation probably also affects sleep, as marked differences between isoCJ1 and w1118 have also recently been found for behavioral responsiveness and sleep intensity measures.

Keywords: behavior, Drosophila melanogaster, endpoints, general anesthesia, isoflurane, synapse

Abbreviations

- CS

Canton-Special

- CSP

cysteine string protein

- EJPs

excitatory junctional potentials

- mEJPs

miniature excitatory junctional potentials

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

Introduction

General anesthesia describes a state of decreased responsiveness, capable of being induced in all animals.1 Exactly how this profound lack of responsiveness is produced remains somewhat of a mystery. The study of genetic model systems has greatly advanced our understanding of general anesthesia, with characterization of mutant animals being one approach pursued to identify general anesthetic targets.1-3 Typically gene expression is altered, and general anesthesia sensitivities are compared between the manipulated and control animals. To ensure reproducibility and to facilitate comparison, only a limited number of control strains are used in most model organisms. In mice, these strains include C57BL and 129;4 N2 is a common control strain used in Caenorhabditis elegans,5 and for Drosophila melanogaster genetics studies, Canton-Special (CS) is one of the most-used wild-type strains, along with white background strains such isoCJ16,7 and w1118, which is a wild-type fly lacking the red eye color pigment.8

Several studies have shown that genetic background has a strong effect on behavior in Drosophila,9-12 and a common strategy to overcome this problem is to outcross mutations to the same genetic background. Yet, selection of which genetic background to use can itself be problematic, because these are likely to influence the behavioral phenotype being studied. In a recent study of sleep in Drosophila, we found that 2 related white strains, isoCJ1 and w1118, differ significantly in sleep architecture and behavioral responsiveness, with w1118 requiring less sleep and being more responsive to a mechanical vibration, for example, than isoCJ1.10 These results suggested there is a major difference in arousal between these related white strains (isoCJ1 is w1118 in a largely CS background),7 although it was not clear whether this was an effect restricted to adult animals, or whether this may be a systemic difference that extends to larvae or perhaps even physiologically at the level of the synapse.

Here, we used newly established general anesthesia assays10,13,14 to characterize behavioral and electrophysiological endpoints in these common genetic background strains (isoCJ1 and w1118), and compared these throughout to CS. A previous study has shown that w1118 is slightly resistant to general anesthetics,15 and it was suggested that this was due to the mutant white gene which may modulate dopaminergic signaling, and hence general anesthesia and sleep.13 However, it was unknown if this resistance effect in w1118 is life-stage dependent, and whether it is also evident across different anesthetic endpoints. By comparing the anesthetic phenotypes of another white mutant (isoCJ1) for all endpoints, we addressed whether these anesthesia phenotypes are likely to stem from the white gene.

We found that the 2 white strains respond differently to isoflurane, across a variety of behavioral endpoints in adults as well as larvae. CS and isoCJ1 show remarkably similar sensitivity to isoflurane for most endpoints examined, yet w1118 shows resistance to isoflurane compared to the other 2 strains, particularly for behavioral endpoints. However, the resistance of w1118 is not evident at the level of neurotransmitter release at the larval NMJ. This suggests that the systemic anesthesia resistance seen in w1118 is not due to a synaptic mechanism,14 nor is it likely to be an effect of the white mutation itself.15 This widespread effect of w1118 on behavior10 and general anesthesia15 highlights the need to carefully characterize control strains before selecting the best background for further genetic experiments. For our sleep10 and anesthesia (this study) experiments, isoCJ1 appears to be more similar to CS than w1118.

Results

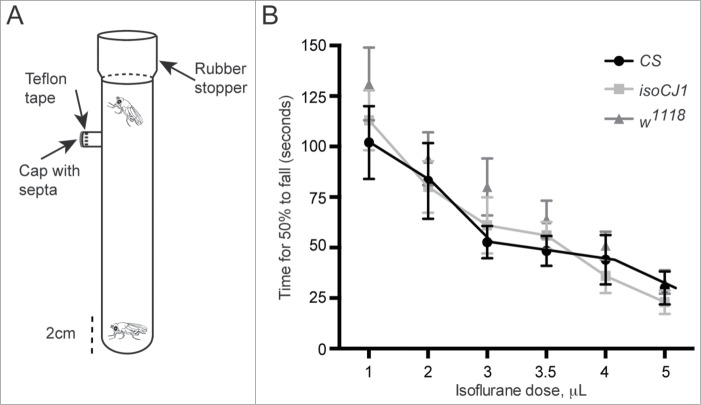

Behavioral responsiveness under isoflurane anesthesia uncovers a significant difference between 2 white strains

We examined adult fly behavior under isoflurane anesthesia using a stimulus-induced locomotion assay13,14 (Fig. 1A). Two anesthesia endpoints are derived from this assay: baseline locomotion (Fig. 1B, blue), and stimulus response locomotion (Fig. 1B, red). We have previously reported the isoflurane sensitivity of these endpoints for CS flies, showing that the EC50 for the stimulus-response locomotion is significantly lower than baseline, indicating that this form of behavioral responsiveness is a more sensitive anesthesia endpoint than baseline locomotion in CS flies.14 We wondered how consistent these endpoints would be across CS, isoCJ1 and w1118. When comparing the baseline locomotion endpoint, we find this endpoint to be fairly consistent across the 3 fly strains (p = 0.5; CS: EC50 = 0.35 ± 0.01, 95% CI, 0.32-0.38, n = 60 flies, isoCJ1: EC50 = 0.35 ± 0.01, 95% CI, 0.30–0.39, n = 40 flies, w1118: EC50 = 0.37 ± 0.01, 95% CI, 0.34–0.39, n = 40 flies, Fig. 1C). We next examined the stimulus-response locomotion endpoint, comparing CS, isoCJ1 and w1118. CS and isoCJ1 show similar responsiveness under isoflurane (CS: EC50 = 0.30 ± 0.005, 95% CI, 0.29–0.31, n = 60 flies vs. isoCJ1: EC50 = 0.28 ± 0.003, 95% CI, 0.27–0.29, n = 40 flies, p = 0.12, Fig. 1D). Moreover, consistent with CS flies, 14 in isoCJ1 the EC50 for the stimulus response endpoint is significantly lower than for baseline locomotion (P < 0.01, extra sum-of-squares F test between estimated EC50). Interestingly, w1118 shows resistance to isoflurane for the stimulus response endpoint compared to both CS and isoCJ1 (EC50 = 0.33 ± 0.01, 95% CI, 0.30–0.37, n = 40 flies, P < 0.01, Fig. 1D). Furthermore, unlike CS and isoCJ1, the stimulus response EC50 in w1118 is not significantly different than baseline locomotion (p = 0.09, extra sum-of-squares F test between estimated EC50). Our results show that responsiveness measures under general anesthesia are slightly different in these 3 common background strains of Drosophila, suggesting strain variability is an important consideration for drug studies. Since w1118 and isoCJ1 are supposed to harbor the same mutation in the white gene,7 these significant differences suggest the cause for the isoflurane anesthesia phenotype might lie elsewhere.

Figure 1.

The stimulus-induced locomotion assay quantifies fly responsiveness under isoflurane anesthesia. (A) Schematic of isoflurane anesthesia apparatus. Flies placed in individual glass tubes are presented with vibration stimuli delivered by motors (dashed circles) underneath the behavioral scaffold, which is enclosed in a chamber. Fly locomotion is monitored with a webcam. (B) Representative traces of fly locomotion before (blue) and after (red) the vibration stimulus (y axis denotes horizontal displacement in the tube (pixels) and x axis denotes time). (C) Summary of baseline locomotion endpoint in CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray) flies. Left: dose response curves are shown, with baseline velocity values normalized to their velocity in air (0vol% isoflurane). Error bars denote SEM. Right: summary of the EC50 (isoflurane vol%) for baseline locomotion in the 3 strains. Error bars represent SEE. (D) Summary of the stimulus response endpoint in CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray) flies. Left: dose response curves are shown, with mechanical stimulus velocity values normalized to their velocity in air (0vol% isoflurane). Error bars denote SEM. Right: summary of the EC50 (isoflurane vol%) for mechanical induced locomotion response in the 3 strains. Error bars represent SEE. The EC50 for the stimulus induced locomotion response is significantly higher in w1118 (dark gray) flies compared to CS (black) and isoCJ1 (light gray). ** P < 0.01, calculated by extra sum-of-squares F test between estimated EC50. N = 60 flies for CS, n = 40 for isoCJ1 and w1118.

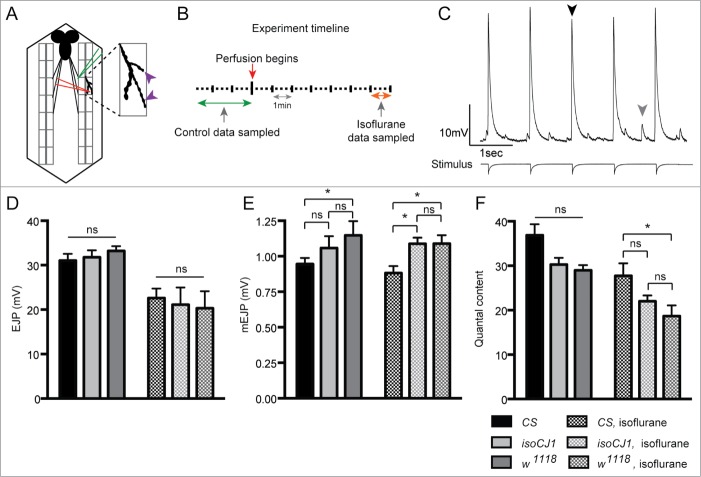

Testing fly climbing ability under isoflurane

To further explore baseline behavioral capabilities of flies under general anesthesia, we devised a fly coordination assay (Fig. 2A).14 This simple general anesthesia assay assessed a fly's capability to demonstrate negative geotaxis and move upwards against gravity, displaying climbing behavior.16 We find this endpoint is quite sensitive to the effects of isoflurane in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118: at concentrations of isoflurane sufficient to produce loss of consciousness in humans,17 (4 μL = 0.9vol% isoflurane), 14 the time taken for half the flies to fall to the bottom of the tube is less than 1 min (Fig. 2B). All three fly strains show similar sensitivity to isoflurane in this assay, with no statistical significant differences evident between the strains (see Table 1 for statistical comparisons). Coupled with our previous analysis (Fig. 1C), this is further evidence that baseline behavioral capabilities are similar between the 3 strains under general anesthesia.

Figure 2.

The fly coordination assay quantifies fly climbing behavior under isoflurane anesthesia. (A) A schematic of the fly coordination assay is shown. The tubes are commercially available glass tubes, 100 mL volume. The tubes were sealed with a rubber stopper, and the side-arm of the tube was sealed with Teflon tape, and a small cap with septa which would facilitate the insertion of a syringe. After anesthetic injection, the number of flies in the bottom 2 cm of the tube is counted every 10 sec. Data shown is the mean time for 50% of the flies to become anesthetized, error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) The mean time for 50% of CS (black circles), isoCJ1 (light gray squares) and w1118 (dark gray triangles) flies to fall to the bottom of the tube is shown, exposed to increasing isoflurane concentrations; n = 10 experiments per concentration, per genotype.

Table 1.

Statistical comparisons of CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 in fly coordination anesthesia assay. The mean time for 50% of flies to become anesthetized in the fly coordination across different isoflurane doses was compared between CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 over 10 individual experiments per concentration (n = 10). The distribution of the data was examined with the Lilliefors test to determine if a parametric or non-parametric t-test should be used.

| Isoflurane dose (μL) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype comparison (p value) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 |

| CS vs. iscoCJ1 | 0.665 | 0.896 | 0.759 | 0.761 | 0.597 | 0.750 |

| CS vs. w1118 | 0.284 | 0.636 | 0.156 | 0.380 | 0.624 | 0.659 |

| w1118 vs. isoCJ1 | 0.450 | 0.453 | 0.349 | 0.560 | 0.186 | 0.285 |

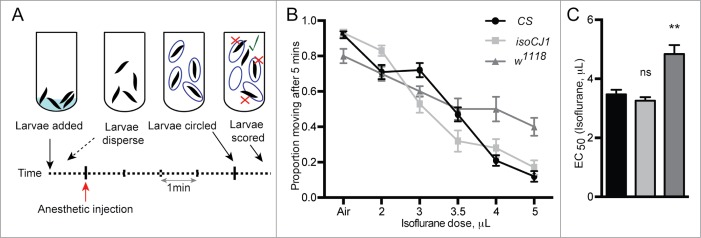

Larval locomotion is compromised by isoflurane

The larval stage of Drosophila represents an immature stage of the fly's lifecycle, amenable to behavioral assays and electrophysiology analyses. Larvae have a different nervous system to the adult fly,18,19 thus a thorough investigation of general anesthesia in Drosophila should ideally examine both life stages, due to these distinct brain architectures found in both animals. Importantly, it is unclear whether fly larvae sleep,20 so if the isoflurane resistance effects seen in w1118 stem from sleep-related processes,10 then these might not manifest in a life stage that may not have yet developed the relevant sleep circuitry. On the other hand, isoflurane resistance in w1118 larvae might suggest a more systemic effect.

We adapted our adult coordination assay and devised a coordination assay to test larval behavior under general anesthesia14 (Fig. 3A and see Materials and Methods). Under increasing concentrations of isoflurane, the proportion of larvae that can display coordinated movement significantly decreases (see Table 2 for statistical comparisons between the strains). Consistent with trends uncovered in adult Drosophila, a greater proportion of w1118 larvae are capable of coordinated movement compared to CS and isoCJ1, particularly at the higher isoflurane concentrations (Fig. 3B). This is also reflected in the EC50 values: the EC50 for w1118 in the larval behavioral assay is 4.8 ± 0.01 μL isoflurane (95% CI, 3.9–5.6, n = 96 larvae, Fig. 3C) and is significantly higher than both CS (EC50 = 3.4 ± 0.15 μL isoflurane, 95% CI, 3–3.9, n = 96 larvae, P < 0.01, Fig. 3C) and isoCJ1 (EC50 = 3.3 ± 0.12 μL isoflurane, 95% CI, 2.9–3.6, n = 96 larvae, P < 0.01, Fig. 3C). Isoflurane resistance in w1118 larvae suggests a mechanism that is not necessarily linked to the sleep/wake circuits that are found in adult flies. 6,21,22

Figure 3.

The larval anesthesia assay quantifies the proportion of larvae that can display coordinated movement under isoflurane anesthesia. (A) The larval general anesthesia assay uses the same apparatus as the fly coordination assay. Larvae are placed in glass tubes, and their capability to display coordinated movement is quantified. After general anesthetic exposure for 4 min, the position of the larvae is traced on the outside of the glass. After another minute, larvae that have moved at least one-body-length outside the marked circle were noted (green tick). (B) The proportion of wild-type larvae, CS (black circles), isoCJ1 (light gray squares) and w1118 (dark gray triangles) moving after 5 min of anesthetic exposure as a function increasing isoflurane dose (μL) is shown (n = 12 experiments per concentration, per genotype). See Table 2 for statistical comparison between the strains for isoflurane data. Error bars represent SEM. Isoflurane concentrations in vol% atm have been reported previously. 14 (C) EC50 (isoflurane dose in μL) of larval locomotion for CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray). ** P < 0.01, calculated by extra sum-of-squares F test between estimated EC50. Error bars represent SEE.

Table 2.

Statistical comparisons of CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 in larval anesthesia assay. The proportion of larvae that cannot display coordinated movement across different doses of isoflurane was compared between CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 over 12 individual experiments per concentration (n = 12). The distribution of the data was examined with the Lilliefors test to determine if a parametric or non-parametric t-test should be used.

| Isoflurane dose (μL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype comparison (p value) | Air | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 |

| CS vs. iscoCJ1 | 0.7215 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.01 | 0.061 | 0.5443 | 0.0625 |

| CS vs. w1118 | P < 0.05 | 0. 273 | P < 0.01 | 0.244 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.0001 |

| w1118 vs. isoCJ1 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.01 | 0.717 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.001 |

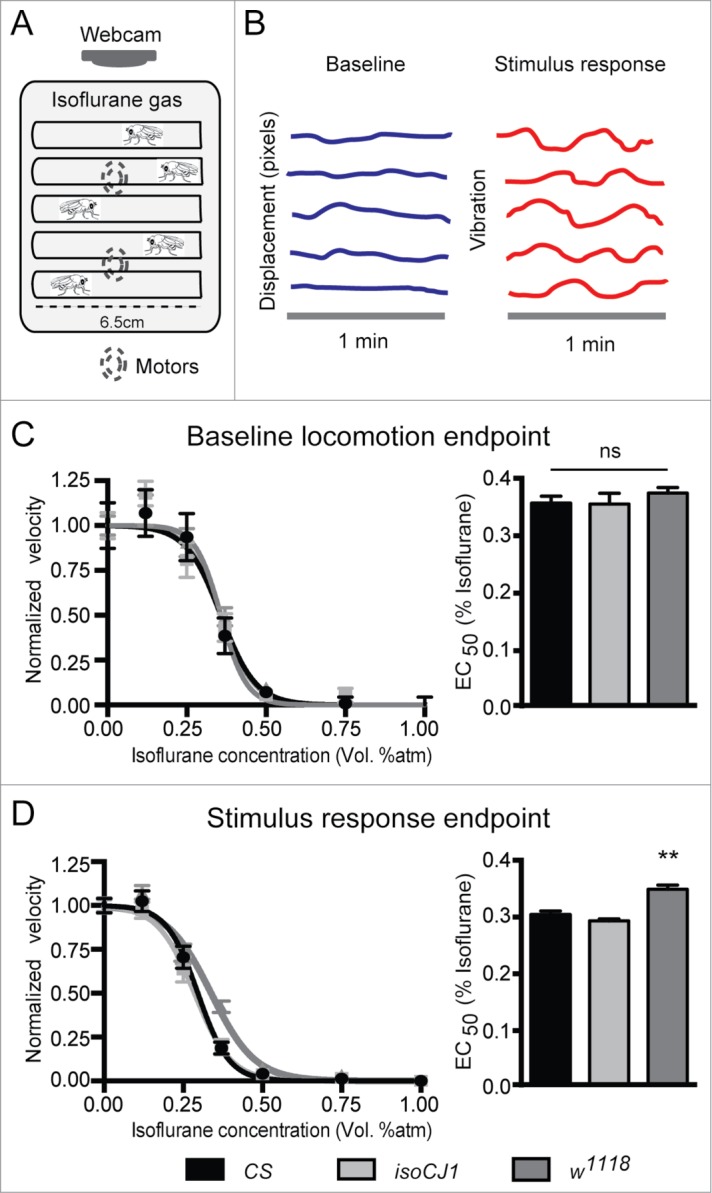

Isoflurane decreases transmitter release at the NMJ

We have recently proposed an alternative mechanism for general anesthesia that involves the synaptic release machinery.14,20 To investigate if the decreases in larval coordination under general anesthesia reflected a change in neurotransmitter release, synaptic transmission was examined at the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Fig. 4A). We recorded mEJPs and EJPs at NMJs before and during exposure to isoflurane perfusion (Fig. 4B & C). Based on a previously published dose-response characterization of the effects of isoflurane on synaptic transmission in Drosophila,23 we focused our investigations on isoflurane concentrations around the reported EC50 of 0.17 mM isoflurane that decreased EJP amplitudes in CS.23 We therefore measure 3 synaptic readouts: evoked responses (EJPs), spontaneous potentials (mEJPs), and quantal content. The latter is derived from the former 2 metrics, and provides a measure of the average number of synaptic vesicles releasing neurotransmitter.24,25

Figure 4.

Transmitter release decreases with isoflurane perfusion in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118. (A) A schematic of the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) recording preparation is shown. The recording electrode (red) is impaled into muscle 6 of segment 3 of dissected third-instar larvae. A stimulating electrode (green) encases the nerve, which innervates the muscle. Dashed lines represent a more detailed schematic of muscle 6 synaptic boutons (purple arrowheads) which release glutamate onto the muscle. Not all muscles or nerves are shown for simplicity, and the brain is shown in this schematic for illustration purposes only (brain is removed when recording). (B) Time course of NMJ experiment, showing duration of the recording (in min) with red arrow denoting when isoflurane perfusion begins, green arrow denoting time window when control data was sampled, and the orange arrow denoting when isoflurane perfusion data was sampled. (C) Example recording trace, showing nerve-evoked excitatory junctional potentials (EJPs, black arrowhead; stimulus trace shown below represent the times at which the stimulus pulses were applied). Spontaneous miniature excitatory junctional potentials (mEJPs, gray arrowhead) are also shown. (D) EJP amplitude (mV) in CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray) before (solid bars) and after isoflurane perfusion (shaded bars). (E) mEJP amplitude (mV) in CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray) before (solid bars) and after isoflurane perfusion (shaded bars). (F) Quantal content in CS (black), isoCJ1 (light gray) and w1118 (dark gray) before (solid bars) and after isoflurane perfusion (shaded bars). Quantal content is calculated by dividing the mean EJP amplitude by the mean mEJP amplitude. Data in (D) to (F) represents mean ± SEM from: CS (n = 14), isoCJ1 (n = 10) and w1118 (n = 10). * P < 0.05. Control vs. isoflurane comparisons were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. Comparisons between genotypes were analyzed with 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

Surprisingly, unlike our behavioral analysis in larvae, we found isoflurane perfusion produced a consistent effect across all 3 strains at the level of transmitter release. The amplitude of evoked responses significantly decreases with isoflurane perfusion in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 4D). There is no significant difference between the strains for the amplitude of evoked responses, with genotype not contributing significantly to the source of variation (p = 0.57, 2-way ANOVA). The amplitude of mEJP responses is however different in the 3 strains (Fig. 4E): in w1118 mEJP amplitudes are consistently higher than CS both before and after isoflurane perfusion (P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA), but not isoCJ1. Following isoflurane perfusion, the amplitude of mEJP responses is higher in isoCJ1 compared to CS (P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). However, as shown previously for CS,14 the amplitude of mEJPs remains unchanged in all 3 strains before and after isoflurane perfusion (Fig. 4E). Consistent with these effects, quantal content decreases with isoflurane perfusion in all 3 strains (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Fig. 4F). We find that when comparing the 3 strains, following isoflurane perfusion, quantal content is significantly lower in w1118 compared only to CS (P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). For quantal content, genotype accounts for 20% of the variation between strains (P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA). Despite the variation between the 3 strains, quantal content is not significantly different prior to isoflurane perfusion. Notably, w1118 is not resistant compared to CS or isoCJ1 for any of these electrophysiological endpoints. Rather, both white strains show a trend to increased mEJP amplitudes, compared to CS.

Discussion

Together with mice and nematodes, the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, has proven to be an important genetic model organism in the study of general anesthesia mechanisms. We studied behavioral and electrophysiological endpoints in 3 commonly used strains of Drosophila: wild-type CS, and 2 white-eyed strains, isoCJ1 and w1118. There are numerous studies reporting Drosophila mutant strains with different anesthetic sensitivities.12-16,26-32 Differences in general anesthesia sensitivities of different CS stocks has also been previously noted,12 and individual background strains have been characterized for their anesthetic sensitivity for specific endpoints,33 but a direct comparison across a range of endpoints in commonly used background strains has not been reported. In this study, we asked 2 broad questions: do different background strains display different sensitivity to isoflurane, and are any differences systemic across various endpoints in different life stages?

For adult flies, we examined behavioral responsiveness under isoflurane anesthesia using a stimulus-induced locomotion assay (Fig. 1A & B)13,14 in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118. We found all 3 strains show similar baseline locomotion capabilities under isoflurane anesthesia (Fig. 1C), but differences arise when examining behavioral responsiveness. The w1118 strain shows resistance for the stimulus response anesthetic endpoint compared to the other 2 strains (P < 0.01, Fig. 1D). Examining climbing behavior under isoflurane anesthesia shows that this endpoint is very sensitive in the fly, and climbing behavior is compromised to a similar extent all 3 strains (Fig 2B), which is consistent with our baseline locomotion result (Fig 1C). We found w1118 shows resistance to isoflurane as larvae. Under increasing doses of isoflurane, the proportion of larvae displaying coordinated movement decreases to a similar extent for CS and isoCJ1, yet for w1118, a significantly greater proportion of these larvae are capable of coordinated movement, particularly at high doses of isoflurane (see Table 2 for statistical comparison between the strains). Indeed, the EC50 for w1118 in the larval behavioral assay is significantly higher than both CS and isoCJ1 (P < 0.01, Fig. 3C). Thus, we have found w1118 is resistant to isoflurane compared to CS and isoCJ1 across adult responsiveness endpoints and also larval behavioral endpoints.

Our behavioral analysis of general anesthesia across adult and larval animals highlights an important consideration regarding anesthetic targets. We have postulated that general anesthesia may reflect 2 parallel target processes affected at different anesthetic concentrations: sleep-promoting pathways are activated first at low drug concentrations (thereby producing a “gentle” loss of consciousness for drugs such as isoflurane), and synaptic mechanisms are attenuated at the higher drug concentrations required for surgery.7 In regards to sleep-promoting pathways, in contrast to adult flies6,21,22, sleep circuitry is yet to be defined in larvae. Since we have shown isoflurane resistance of w1118 in both adults and larvae, this suggests the resistance may not be related to specific neural circuitry found in either animal, such as sleep/wake pathways in the adult fly6,21,22. Thus, our data suggest general anesthetics may act independently of sleep pathways.

We have also examined synaptic release properties with isoflurane perfusion in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118. This serves 2 key purposes. Firstly, it ascertains if the decrease in larval locomotion with isoflurane is reflected in a change in transmitter release. Secondly, resistance effects, if any, can be examined in a discrete neuronal circuit. Examining both EJP and mEJP responses from sharp intracellular recordings of muscle 6 in segment 3 (Fig. 4A), we find isoflurane perfusion corresponding to a concentration of 0.19 mM significantly decreased the amplitudes of EJPs in CS, isoCJ1 and w1118 (Fig. 4D). In contrast, isoflurane did not affect the amplitude of mEJP responses (Fig. 4E), in agreement with previous reports for isoflurane14,23 and halothane.34 We find that quantal content, a measure of how many vesicles are released per action potential was significantly decreased by isoflurane (Fig. 4F). Importantly, this effect on quantal content was the same for all 3 strains, so isoflurane resistance in w1118 cannot be due to increased synaptic release in this strain under anesthesia.

We have previously reported a consistency of effects between behavioral and electrophysiological endpoints under isoflurane anesthesia, with a mutant strain showing behavioral resistance to isoflurane also reflected at the level of transmitter release.14 Here, we report that the isoflurane resistance of w1118 is not evident at the level of transmitter release. Quantal content is actually significantly lower following isoflurane perfusion in w1118 compared to CS (P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA). Previous studies have reported reduced immunoreactivity for the synaptic vesicle marker cysteine string protein (CSP) in adult w1118, with this strain even having fewer synaptic vesicles compared to wild-type flies (Oregon-R).35 While this analysis was performed in adult flies, fewer synaptic vesicles in w1118 may explain why resistance to isoflurane is not reflected at the level of transmitter release, although differences prior to isoflurane exposure for quantal content are not evident in w1118. Interestingly, we found the amplitude of mEJPs to be significantly higher in w1118 compared to CS (P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA) prior to isoflurane perfusion. This suggests there may be a homeostatic adaptation in w1118: synaptic vesicles may contain more glutamate to compensate for their being fewer in number.

What then could explain the resistance of w1118 across multiple behavioral endpoints? Given the consistency of behavioral resistance to isoflurane for w1118 across the fly's lifecycle, this may reflect a role for the dopamine pathway that has been linked to the white gene.15,35 However, since isoCJ1 also carries the same mutation in the white gene, similar resistance levels should be expected in this strain if the anesthetic resistance was related to this neurotransmitter system. Since isoCJ1 is more similar to CS for the anesthetic endpoints investigated, this suggests that the resistance of w1118 does not stem from the white gene, although we cannot rule out the possibility that modifiers could be suppressing the effects of the white gene in isoCJ1. Resistance in w1118 must be related to another mutation present in w1118.7 Due to the likely presence of other mutations modifying anesthetic sensitivity in w1118, coupled with the similar anesthetic sensitivities of CS and isoCJ1, our analysis suggests isoCJ1 is a more suitable genetic background of mutant strains to study anesthetic sensitivities. In a recent study we have shown that isoCJ1 is also potentially a better background strain for sleep studies, because it is less responsive at night than w1118, as was also shown for CS.36

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

D. melanogaster were cultured on a yeast-sugar-agar medium in vials at 25°C on a 12-h light-dark cycle. Female flies (3–5 d old) were selected for behavioral experiments by brief carbon dioxide exposure and kept in food vials overnight prior to experiments. The control strains used in this study were wild-type Canton-Special strain (FBsn0000274), isolated by Bruno van Swinderen from Ralph Greenspan's stock in San Diego, CA in 1999 and taken to Brisbane, Australia. The w1118 stock (FBst0005905) was sourced from Bloomington. The isoCJ1 stock was from Kazuhiko Kume, Nagoya City University, Japan, and describes a white CS isogenic stock.6,7

Behavioral assays

Startle assay

The stimulus-induced locomotion assay assesses flies' movement response to a startle-inducing vibration stimulus, and has been described previously.13,14 Briefly, flies are placed in individual tubes, with their movement constantly filmed via a webcam. Locomotion before and after a mechanical vibration stimulus is quantified using a custom Matlab program (Drosophila Arousal Tracking, DART10) before and during isoflurane anesthesia. Isoflurane delivery into the behavioral apparatus has been described previously.13,14

Coordination assay

The fly-coordination assay was developed from previous Drosophila general anesthesia assays16,30 and has been described previously.14 Briefly, approximately 10 flies are placed in a 100 mL cylindrical glass tubes (length 20 cm, diameter 2.5 cm) with a side-arm. Following anesthetic injection, the number of flies in the bottom of the tube is counted every 10 s. This was repeated until the last fly had dropped to the bottom of the tube. Isoflurane concentrations used in this assay have been reported previously.14 Data were converted to express the number of flies in the bottom of the tube as a proportion, and tested for normality using the Lilliefors test.37 The mean time for 50% of the flies to fall to the bottom was compared across genotypes. Normally distributed data was tested for significance (P < 0.05) by 2-tailed t-test comparing means. Otherwise, for the nonparametric data, a Mann-Whitney test for unpaired comparisons was used.

Larval anesthesia assay

The larval anesthesia assay quantifies larval movement under isoflurane anesthesia and has been described previously. 14 Briefly, 9 larvae are exposed to isoflurane in 100 mL cylindrical glass tubes (same tubes used for adult fly coordination assay: length 20 cm, diameter 2.5 cm) for 4 min. The larvae's position was then circled with a marker on the outside of the glass. After a further 1 min, the number of larvae that had moved at least one-body-length outside the marked circle was noted, and data converted to express the number of larvae that moved as a proportion of the total. Data were tested for normality using the Lilliefors test.37 If the data to be compared is normal, a 2-tailed unpaired t-test was used for analyses. Otherwise, nonparametric comparisons were made with the Mann-Whitney test for unpaired comparisons. EC50 values were obtained as described below.

Curve fitting for stimulus-induced locomotion assay and larval assay

Velocity data of the adult flies (stimulus-induced locomotion assay) or the proportion of larvae that displayed coordinated movement was normalized to the response at 0vol% isoflurane to enable comparisons across experiments. Data was fit by nonlinear regression (Prism 6, Graphpad) to estimate an EC50 and standard error of the estimate (SEE) as described previously.13,14 Separate curves were compared for significant differences by simultaneous curve fitting, where all data are fit together while constraining the EC50 to be shared,38 with significance indicating rejection of the null hypothesis that both datasets share a common EC50 (extra sum-of-squares F test, P < 0.05). EC50 data represent isoflurane volume % atmospheres mean ± standard error of the estimate with 95% CIs reported.

Electrophysiology

Sharp intracellular recordings were made from the larval NMJ on muscle 6 in segment 3 as described previously.14,39 Briefly, wandering third instar larvae were dissected in ice-cold Schneider's insect medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. S0146), and pinned onto glass dissection plates. Intracellular electrodes (50–80 MΩ) were filled with a 2:1 mixture of 3 M potassium acetate and 3 M potassium chloride. Recordings were conducted at room temperature in HL3 haemolymph-like solution40,41 with [Ca2+] = 0.7 mM and [Mg2+] = 20 mM. Analysis was performed on recordings with membrane potentials lower than −65 mV.

Signals from intracellular recordings were amplified using an Axoclamp2B amplifier (Molecular Devices) in bridge mode. Signals were captured and stored using the Chart software (v.5.5.4; 2 kHz sampling rate) and hardware incorporated with the PowerLab/4s data acquisition system (ADInstruments).

Isoflurane solutions were prepared as previously described.14,23 Saline was perfused onto the dissected larvae using a syringe pump (KD Scientific) at a rate of approximately 1 mL/min. Recordings begin with 3 min of baseline excitatory junctional potentials (EJPs), stimulated at a frequency of 1 Hz. Isoflurane perfusion is then initiated, and continues until the recording has lasted 10 min or the muscles start contracting23 and the impalement is lost, whichever occurs first. Isoflurane concentrations in saline at the NMJ was determined by gas chromatographic headspace analysis (PerkinElmer Clarus 680 GC-FID), performed as described previously.14,23

NMJ analyses

Recordings were processed in Axograph as described previously.14 The amplitude and baseline offset of EJPs and mEJPs was obtained. Quantal content was calculated by dividing the mean EJP amplitude by the mean mEJP amplitude. Evoked responses were corrected for nonlinear summation 42 prior to calculations. Tests for significant differences between control and isoflurane perfusion were conducted using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. To test for significant differences between genotypes under isoflurane perfusion, 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test was used. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by Australian Research Council grants (FT100100725 and DP1093968 to BvS and LEI130100078 to SK).

References

- 1.Humphrey JA, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG. Understanding anesthesia: Making genetic sense of the absence of senses. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11:1241-9; PMID:12015284; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/11.10.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowder CM, Palanca BJ, Evers A. Mechanisms of Anesthesia and Consciousness In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC, Rafael O, eds. Clincial Anesthesia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonner JM, Antognini JF, Dutton RC, Flood P, Gray AT, Harris RA, Homanics GE, Kendig J, Orser B, Raines DE, et al.. Inhaled anesthetics and immobility: mechanisms, mysteries, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:718-40; PMID:12933393; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081063.76651.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandenberg JG. Use of house mice in biomedical research. ILAR J 2000; 41:133-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/ilar.41.3.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaxter M. Nematodes: the worm and its relatives. PLoS Biol 2011; 9:e1001050; PMID:21526226; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueno T, Tomita J, Tanimoto H, Endo K, Ito K, Kume S, Kume K. Identification of a dopamine pathway that regulates sleep and arousal in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15:1516-23; PMID:23064381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.3238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin JC, Del Vecchio M, Zhou H, Tully T. CREB as a memory modulator: Induced expression of a dCREB2 activator isoform enhances long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell 1995; 81:107-15; PMID:7720066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90375-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman SJ, Menon I, Haug-Collet K, Colley NJ. Expression of rhodopsin and arrestin during the light-dark cycle in Drosophila. Molecular vision 2001; 7:95-100; PMID:11320353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colomb J, Brembs B. Sub-strains of Drosophila Canton-S differ markedly in their locomotor behavior. F1000Research 2014; 3:176; PMID:25210619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faville R, Kottler B, Goodhill GJ, Shaw PJ, van Swinderen B. How deeply does your mutant sleep? Probing arousal to better understand sleep defects in Drosophila. Sci Rep 2015; 5:8454; PMID:25677943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep08454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruebenbauer A, Schlyter F, Hansson BS, Lofstedt C, Larsson MC. Genetic variability and robustness of host odor preference in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol 2008; 18:1438-43; PMID:18804372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walcourt A, Nash HA. Genetic effects on an anesthetic-sensitive pathway in the brain of Drosophila. J Neurobiol 2000; 42:69-78; PMID:10623902; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(200001)42:1%3c69::AID-NEU7%3e3.0.CO;2- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottler B, Bao H, Zalucki O, Troup M, Imlach W, van Alphen B, Paulk A, Zhang B, van Swinderen B. A sleep/wake circuit controls isoflurane sensitivity in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2013; 23:594-8; PMID:23499534; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zalucki O, Menon H, Kottler B, Faville R, Day R, Bademosi A, et al.. Syntaxin1A-mediated resistance and hypersensitivity to isoflurane in Drosophila melanogaster. Anesthesiology 2015; 122:1060-74; PMID:25738637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell JL, Nash HA. Volatile general anesthetics reveal a neurobiological role for the white and brown genes of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol 2001; 49:339-49; PMID:11745669; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/neu.10009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allada R, Nash HA. Drosophila melanogaster as a model for study of general anesthesia: The quantitative response to clinical anesthetics and alkanes. Anesth Analg 1993; 77:19-26; PMID:8317731; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1213/00000539-199307000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwyer R, Bennett HL, Eger EI 2nd, Heilbron D. Effects of isoflurane and nitrous oxide in subanesthetic concentrations on memory and responsiveness in volunteers. Anesthesiology 1992; 77:888-98; PMID:1443742; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00000542-199211000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consoulas C, Duch C, Bayline RJ, Levine RB. Behavioral transformations during metamorphosis: Remodeling of neural and motor systems. Brain research bulletin 2000; 53:571-83; PMID:11165793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0361-9230(00)00391-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tissot M, Stocker RF. Metamorphosis in Drosophila and other insects: The fate of neurons throughout the stages. Prog Neurobiol 2000; 62:89-111; PMID:10821983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Swinderen B, Kottler B. Explaining general anesthesia: A two-step hypothesis linking sleep circuits and the synaptic release machinery. BioEssays 2014; 36:372-81; PMID:24449137; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.201300154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donlea JM, Thimgan MS, Suzuki Y, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. Inducing sleep by remote control facilitates memory consolidation in Drosophila. Science 2011; 332:1571-6; PMID:21700877; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1202249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q, Liu S, Kodama L, Driscoll MR, Wu MN. Two dopaminergic neurons signal to the dorsal fan-shaped body to promote wakefulness in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2012; 22:2114-23; PMID:23022067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandstrom DJ. Isoflurane depresses glutamate release by reducing neuronal excitability at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Physiol 2004; 558:489-502; PMID:15169847; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karunanithi S, Barclay JW, Robertson RM, Brown IR, Atwood HL. Neuroprotection at Drosophila synapses conferred by prior heat shock. J Neurosci 1999; 19:4360-9; PMID:10341239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9:813-25; PMID:18854855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrn2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alone DP, Rodriguez JC, Noland CL, Nash HA. Impact of gene copy number variation on anesthesia in Drosophila melanogaster. Anesthesiology 2009; 111:15-24; PMID:19546691; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a3276c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell DB, Nash HA. Use of Drosophila mutants to distinguish among volatile general anesthetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:2135-9; PMID:8134360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamo S, Ogaki M, Nakashima-Tanaka E. Strain differences in minimum anesthetic concentrations in Drosophila melanogaster. Anesthesiology 1981; 54:289-93; PMID:6782911; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00000542-198104000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gamo S, Tomida J, Dodo K, Keyakidani D, Matakatsu H, Yamamoto D, Tanaka Y. Calreticulin mediates anesthetic sensitivity in Drosophila melanogaster. Anesthesiology 2003; 99:867-75; PMID:14508319; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan Z, Scott RL, Nash HA. A new assay for the genetic study of general anesthesia in Drosophila melanogaster: Use in analysis of mutations in the X-chromosomal 12E region. J Neurogenet 2000; 14:25-42; PMID:10938546; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/01677060009083475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan KS, Nash HA. A genetic study of the anesthetic response: mutants of Drosophila melanogaster altered in sensitivity to halothane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:8632-6; PMID:2122464; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walcourt A, Scott RL, Nash HA. Blockage of one class of potassium channel alters the effectiveness of halothane in a brain circuit of Drosophila. Anesth Analg 2001; 92:535-41; PMID:11159264; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1213/00000539-200102000-00047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell JL, Nash HA. The visually-induced jump response of Drosophila melanogaster is sensitive to volatile anesthetics. J Neurogenet 1998; 12:241-51; PMID:10656111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/01677069809108561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishikawa K, Kidokoro Y. Halothane presynaptically depresses synaptic transmission in wild-type Drosophila larvae but not in halothane-resistant (har) mutants. Anesthesiology 1999; 90:1691-7; PMID:10360868; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borycz J, Borycz JA, Kubow A, Lloyd V, Meinertzhagen IA. Drosophila ABC transporter mutants white, brown and scarlet have altered contents and distribution of biogenic amines in the brain. J Exp Biol 2008; 211:3454-66; PMID:18931318; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jeb.021162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Alphen B, Yap MH, Kirszenblat L, Kottler B, van Swinderen B. A dynamic deep sleep stage in Drosophila. J Neurosci 2013; 33:6917-27; PMID:23595750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0061-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilliefors HW. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality with mean and variance unknown. J Am Stat Assoc 1967; 62:399-402http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/01621459.1967.10482916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waud DR. On biological assays involving quantal responses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1972; 183:577-607; PMID:4636393 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong K, Karunanithi S, Atwood HL. Quantal unit populations at the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction. J Neurophysiol 1999; 82:1497-511; PMID:10482765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macleod GT, Hegstrom-Wojtowicz M, Charlton MP, Atwood HL. Fast calcium signals in Drosophila motor neuron terminals. J Neurophysiol 2002; 88:2659-63; PMID:12424301; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.00515.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart BA, Atwood HL, Renger JJ, Wang J, Wu CF. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol A 1994; 175:179-91; PMID:8071894; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00215114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feeney CJ, Karunanithi S, Pearce J, Govind CK, Atwood HL. Motor nerve terminals on abdominal muscles in larval flesh flies, Sarcophaga bullata: Comparisons with Drosophila. J Comp Neurol 1998; 402:197-209; PMID:9845243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981214)402:2%3c197::AID-CNE5%3e3.0.CO;2-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]