Abstract

Noise caused by fluctuations at the molecular level is a fundamental part of intracellular processes. While the response of biological systems to noise has been studied extensively, there has been limited understanding of how to exploit it to induce a desired cell state. Here we present a scalable, quantitative method based on the Freidlin-Wentzell action to predict and control noise-induced switching between different states in genetic networks that, conveniently, can also control transitions between stable states in the absence of noise. We apply this methodology to models of cell differentiation and show how predicted manipulations of tunable factors can induce lineage changes, and further utilize it to identify new candidate strategies for cancer therapy in a cell death pathway model. This framework offers a systems approach to identifying the key factors for rationally manipulating biophysical dynamics, and should also find use in controlling other classes of noisy complex networks.

Keywords: Complex Systems, Biological Physics, Nonlinear Dynamics

I. INTRODUCTION

Cellular systems are not entirely deterministic, but are instead impacted by small, random fluctuations in the number and activity of molecules of intracellular species [1, 2]. Such fluctuations lead to macroscopic effects in a diverse array of processes. In differentiation, the resulting noise plays a central role in cell fate determination and can allow clonal populations of differentiating cells to achieve distinct final states [3, 4]. Noise can also produce spontaneous transitions, whereby it causes a system to switch from one stable state to another, often producing a significant change of phenotype or function. Such stochastic state switching occurs, for example, in the lac system, where rare, brief transcription events in the “off” state cause large bursts in LacY expression, which in turn can be amplified and stabilized by a positive feedback loop [5]. Stochastically-induced transitions also underlie recent observations of spontaneous dedifferentiation in cancer cells [6, 7], in which cancer stem cells arose de-novo from non-stem cell populations.

The response to noise and the overall behavior of many biophysical systems are determined by an underlying epigenetic landscape [8]. In this landscape, the valleys represent the distinct achievable states of the system and the heights of the separating barriers determine their robustness to noise. A benefit of this representation is that bifurcation points—locations in the parameter space at which one or more stable states suddenly cease to exist— correspond precisely to the points where one or more of such barriers first reach zero height as parameters change. This landscape thus incorporates two distinct features of a state, namely its robustness to noise and its deterministic stability, into one: the less robust a state is to noise, the closer it is to being eliminated through a bifurcation, and vice-versa.

The landscape representation has been given a quantitative foundation as the quasipotential of the deterministic component of the system dynamics [9] and has been explored in experiments—e.g., to show how two parameters in the yeast galactose signaling network, the concentrations of galactose and intracellular Gal80p, can alter the rates of stochastic switching in this bistable circuit [10]. Despite these advances, researchers’ ability to control this landscape in order to induce prespecified biological outcomes has been generally limited to at most two parameters [11, 12], and no general method currently exists to systematically tune transitions between stable states and/or eliminate undesired states altogether. The possibility of such control would offer clear opportunities. For example, under the widely supported stochastic model for induced pluripotent stem cell generation [13], a majority of cells have the possibility of being reprogrammed, even though existing technologies have achieved substantially smaller yields [14]. The ability to control the response to noise of differentiated and stem-cell states (e.g., inhibiting transitions to the first and promoting transitions to the second) could lead to enhanced procedures to create induced pluripotent stem cells. Similarly, in the context of the “cancer attractor” hypothesis [15, 16], in which normal and cancer cells correspond to distinct co-existing stable states, identifying interventions that destabilize, or eliminate, the cancerous state could lead to new therapeutic strategies.

In this paper we propose a broadly applicable method, here termed optimal least action control (OLAC), that can predict and control the dynamical behavior and response to noise in a wide class of biophysical networks. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 1, the essence of our approach is that to control a biophysical system it is sufficient to identify interventions—e.g., changes to gene expression, protein levels, or interaction rates—that can reshape the topography of the underlying quasipotential in a desired way. This approach ultimately leads to a network of state transitions (NEST) describing the transitions between stable states and that can be controlled by changing the heights of the separating barriers without changing any quality of the noise. For a given system, this is achieved by determining the minimum action paths—those followed by the most likely noise-induced transition trajectories—and the corresponding transition rates between all pairs of stable states, and then optimizing these transition rates for a desired outcome. Furthermore, this general foundation in a physical least-action principle allows OLAC to be applied broadly to many other complex networks as well. In particular, while we focus our application of OLAC to biophysical networks, applications to other networks where noise and multistability play important roles, including power-grid networks [17], polymer networks [18] and food-web networks [19], among others, are immediate within the formulation we establish here.

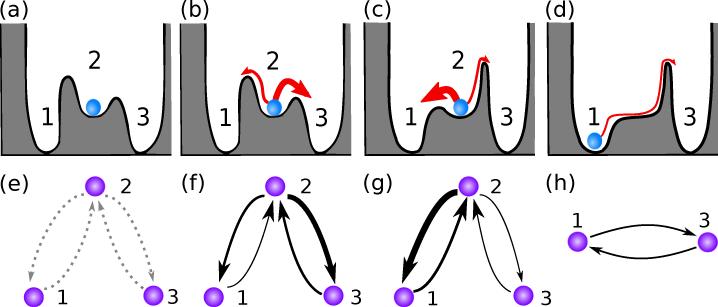

FIG. 1.

Control of the response to noise illustrated for a multi-well quasipotential. (a) Without noise the state of the system is fixed and will not change over time. (b) In the presence of noise the state of the system wanders within the attraction basin and will be eventually ejected into the attraction basin of another stable state. For small noise such transitions are exponentially more likely to occur through the lowest barrier, even though other transitions are also possible in principle. (c) Using OLAC on a set of tunable parameters, we can alter the quasipotential to produce a desired response to noise, in this case tailored to increase transitions from state 2 to state 1 and to reduce transitions to state 3. (d) If desired, OLAC can also find combinations of tunable parameters that can alter the quasipotential in order to eliminate a stable state through a bifurcation; in this illustration state 2 is eliminated, in favor of state 1. (e-h) NEST for each of the quasipotentials in (a-d), respectively, where the nodes represent stable states and the continuous edges represent transition rates. A wider continuous edge indicates a higher transition rate. The dotted edges in (e) indicate transitions that could occur in the presence of noise.

We apply OLAC to several gene network models and illustrate how this method can be used to make biologically realizable reprogramming predictions. In the limit of zero noise intensity, OLAC automatically identifies bifurcations that eliminate undesirable states and induce purely deterministic transitions to the desired ones. The significance of the latter is demonstrated by considering a third application, to eliminate cancerous states in a cell death network model, which concerns a time scale for which stochastic switches can be neglected. As illustrated in these examples, the NEST is a powerful yet simple representation that captures the essence of the state switching dynamics and can inform counterintuitive results—e.g., the possibility of transitions through intermediate stable states when direct transitions are essentially impossible (a behavior observed even in high dimensions, where indirect transitions generally require longer paths). The method proposed here is easily implemetable and the computational effort scales linearly in the number of control parameters and the dimension of the state space, allowing our approach to be applied to large networks and high-dimensional systems in general.

II. THEORY

A. Transition Rates for Small Noise

We consider biophysical networks whose deterministic components are described by non-linear differential equations of the form , where is a vector representing the activity of the relevant biological factors, is the function representing the rates of change of these factors, and Ω is a set of tunable parameters, which we show can be manipulated to drive cellular processes in advantageous directions. We focus on the most prevalent case of systems with two or more stable states and, although our approach is general, for concreteness we first assume that these states are time-independent. Time-independent stable states correspond to fixed points , defined by , towards which neighboring trajectories converge over time. The set of all stable states represent the possible long-term behaviors of the deterministic system.

Stochasticity is modeled here as additive Gaussian white noise,

| (1) |

where ε is the variance of the distribution (other cases are discussed in the Supplemental Material [20]). With the addition of this small noise term, trajectories no longer approach the stable states asymptotically as in the deterministic case. Instead, a trajectory close to a stable state will oscillate stochastically within its basin of attraction, typically staying close to the fixed point for long periods of time. The trajectory will also make rare but large excursions from the stable state. After sufficiently long time an excursion large enough to eject the trajectory from the original basin of attraction will necessarily occur, at which point it will transition to the neighborhood of another stable state of the system. The time scales for the occurrence of such transitions may be shorter or longer than the biologically relevant ones. The manipulation of these time scales underlies much of the control approach introduced below.

For a given noise intensity ε, the transitions between two stable states, i and j, occur as a Poisson process with a certain rate . These rates can be computed by evolving Eq. (1), but in general at an unreasonably high computational cost. As a way to reduce this effort, we employ an asymptotic formula [21]:

| (2) |

where serves as an excellent approximation to for ε small compared to , which is typically the case for noise associated with biophysical systems. Here, is the minimum of the Freidlin-Wentzell action S[·], a functional over all possible transition paths connecting the two stable states in the state space. The path minimizing the action for the given pair of stable states is calculated numerically employing an implementation of the adaptive minimum action method [22], in which we determine this minimum action path through the optimization of a discretized version of the action functional using a quasi-Newton method (Appendix A). Conceptually, represents the cumulative height of all saddle points traversed by the minimum action path between the states i and j. It should be noted that a proportionality constant is omitted in the expression for . Although there is no known formula for computing this constant in general [23], the key condition for neglecting it is clear: as long as the actions Si,j associated with two paths differ by more than , the exponential term will dominate and the omission of the proportionality constant will not a ect the result qualitatively.

The rate represents the transition probability per unit of time along the most likely direct path(s) between the stable states i and j. The transition rates through intermediate stable states can be determined by composing these elementary transition rates. It is often expected that the most likely transition path between two stable states would be a direct path, but as shown below, in many cases it passes through intermediate stable states. Moreover, the transition paths and rates are generally asymmetric, with . In the limit of long time, these transitions lead to an equilibrium probability distribution of occupied stable states, which we refer to as the limiting occupancy of the system and denote by . Given that we generally study large populations of cells, in our applications it is convenient to interpret the limiting occupancy as an ensemble average over different realizations of noise.

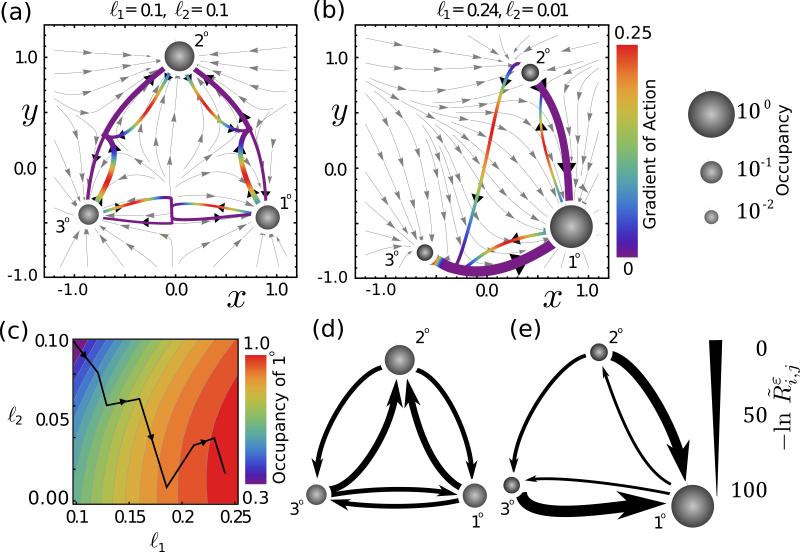

To illustrate the minimum action paths and their use in controlling cell behavior, we first consider a two-dimensional model for the Caenorhabditis elegans vulval precursor cell (VPC) differentiation [24]. The VPC differentiation is representative of many other differentiation processes and enjoys significant experimental characterization. The model describes the differentiation of VPCs into one of three competent lineages, 1°, 2°, and 3°, corresponding to stable states in the system and marked as nodes in Fig. 2(a). These lineages depend on two dimensionless parameters, and , that determine the levels of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and Notch signaling, respectively (for the model equations, see Appendix B). It is known experimentally that increasing EGF and decreasing Notch signaling (relative to the base value of 0.1) will bias cells towards lineage 1°, that decreasing EGF and increasing Notch will bias cells towards lineage 2°, and that decreasing both EGF and Notch will bias cells towards lineage 3° [25]. Figure 2(a) shows the state space for the VPC system with equal, intermediate levels of EGF and Notch signaling () and a realistic level of noise (ε = 0.007). The calculated transition paths, transition rates, and limiting occupancies are indicated by the edges, their width, and the size of the nodes, respectively. For these parameters, our calculations indicate that the limiting occupancy is comparable for all three stable states, with lineage 2° having the highest occupancy.

FIG. 2.

OLAC applied to a two-dimensional model of VPC differentiation. (a, b) State space representation of stable states (nodes) and optimal transition paths (edges) before intervention (a) and after OLAC is applied to maximize the limiting occupancy of lineage 1° (b). Node size indicates occupancy and edge width indicates the (negative of the) log transition rate along the corresponding minimum action path; the color code on the transition paths indicates the derivative of the quasipotential. The background shows the velocity field for the given parameters. For equal EGF and Notch signaling (a), lineage 2° is the one with highest occupancy. The OLAC solution (b) indicates that high EGF signaling and low Notch signaling will lead to the maximum occupancy of lineage 1°. (c) Trajectory in the parameter space for one realization of the optimization procedure, where the contour plot indicates the limiting occupancy of lineage 1°. Note that each step of the optimization routine increases the occupancy of this state. (d, e) NESTs for the initial (d) and optimized (e) systems. In all panels, the noise intensity is assumed to be ε = 0.007 (as used previously [24]).

B. Optimal Least Action Control

We now turn to the manipulation of the tunable parameters , which may include, for example, gene expression levels, protein activity, and interaction rates. Specifically, we seek to modify Ω to optimize either specific transition rates directly or the limiting occupancy through the alteration of the transition rates, while recognizing that the parameters can be modified only within specific ranges determined by biophysical and experimental constraints. The latter include sparsity constraints, which we can use to effectively limit the number of targets in the control set while avoiding a combinatorial explosion (Appendix C). The problem is formalized as the maximization of an objective function of interest G (unique to each problem) over the parameters Ω subject to the given constraints {gk(Ω) = ζk}k and {hk(Ω) ≤ ηk}k:

| (3) |

This procedure constitutes the central step of our implementation of OLAC. Note that this formulation is independent of the dimension and complexity of the system. Thus, given a well-defined model we can identify control interventions able to alter the switching behavior and/or the stability of the states in desired ways without the need to know explicitly a priori how variations of the tunable factors a ect the system (beyond the implicit dependence defined by the dynamical equations).

The objective function and the associated constraints do not need to be linear, allowing a wide range of possible dynamical behaviors to be optimized. For any set of such constraints, Eq. (3) can be solved numerically through a second quasi-Newton method step that nests the adaptive minimum action method used to determined the minimum action paths in connection with Eq. (2). Importantly, OLAC is highly scalable, with the following computational cost:

| (4) |

where D is the number of variables defining the state space, |Ω| is the number of tunable parameters under consideration, P is the number of stable states, and K is the number of transitions upon which G depends. This cost estimation follows from noting that every optimization step of OLAC relies on |Ω| evaluations of G, each of which requiring K runs of the nested optimization step, where each such run has a cost that is linear in D when using the L-BFGS optimization method [26]. Furthermore, for each top-level optimization step (3), every one of the P stable states has to be continued |Ω| times, each time at an integration cost that is linear in D if the average network's degree is approximately constant, as in most network models (it would be at most quadratic in D in the most general case) (Appendix A). Parameter γ accounts for other constants describing the relative cost between optimization and integration. Because of this high scalability, our method can be applied to complex high-dimensional multi-parameter systems without excessive computational cost. In this way OLAC expands on previous foundational work that demonstrated how barriers between stable states can be altered to control the response to fluctuations and multistability [27–32] to now address large networks with many variables and many potential control parameters.

Before turning to high-dimensional systems, we consider an illustrative example application of OLAC in which we maximize the final occupancy of lineage 1° in the VPC system. As an example constraint we stipulate that neither of the other two stable states be lost to bifurcation. This non-bifurcation constraint is intended to depict how the presence of dosing and/or experimental limitations may make complete elimination of undesired states infeasible. This condition is imposed as the constraint that the states representing each lineage k remain stable fixed points: and . In this notation, λk = λk(Ω) is the eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix with largest real part, and τ0 is a tolerance (set to be 0.1 in our simulations). The objective function is and the tunable parameters are . The result, shown in Fig. 2(b), indicates a substantial (3-fold) increase in the limiting occupancy of the lineage 1° state for the optimal control intervention identified by OLAC. The parameter-space path for a representative realization of the optimization is shown in Fig. 2(c). The optimal intervention, defined as an average over multiple realizations, is a combination of increased EGF signaling () and reduced Notch signaling (), which has the net effect of lowering the barrier for transitions from lineages 2° and 3° to lineage 1° while maintaining a high barrier for exiting this lineage. This controlled state corresponds to signaling strengths that have been observed experimentally to indeed bias cell lineages towards lineage 1° [25]. As mentioned above, for these results we utilized Eq. (2) with the proportionality constants omitted to calculate transition rates between states. The inclusion of these prefactors could potentially alter the occupancy calculations of the stable states and in turn invalidate the results of OLAC. In the Supplemental Material [20], Sec. S1, we apply sensitivity analysis to quantify the uncertainty associated with omitting prefactors and show that doing so does not significantly alter the results in this case. That section also discusses more generally under which conditions prefactors can be omitted.

C. Network of State Transitions

Our formulation leads to a succinct and intuitive NEST representation for the transition dynamics, in which the nodes are unique stable states and the weighted, directed edges between nodes represent the rates of transition between the stable states. The basis for this representation is the observation that, for small ε, the trajectories of the system in Eq. (1) are most often close to a stable state or transitioning between stable states along a minimum action path. The trajectories will rarely venture into other regions of the state space, allowing us to focus only on this “waiting-transition” dynamics without sacrificing information about the system's behavior. For a system with P stable states we can write the P × P transition matrix

| (5) |

which defines a (continuous-time) Markov process on the stable states of the system. In our numerical calculations we use the fact that the limiting occupancy is described by the equilibrium solution of this process. In fact, the Markov process specifies all attributes of the associated NEST. The NEST is conceptually similar to the state transition network used in physical chemistry and biochemistry [33–36] as well as to transition networks studied in mathematics [21]. There are, however, key differences between our approach and those considered previously, in addition to the fact that we focus on network systems. In particular, the NEST does not assume the existence of a potential energy landscape and is defined for nonvanishing levels of noise, which required us to develop a new formulation that accounts in particular for long mixing times and for values of ε larger than (see Supplemental Material [20], Sec. S4). Furthermore, unlike static state transition networks, the transition rates in the NEST are malleable and can be rationally manipulated with OLAC.

For the VPC model, the NESTs corresponding to the unmodified signaling strengths [Fig. 2(a)] and to the signaling strengths that optimize lineage 1° occupancy [Fig. 2(b)] are shown in Figs. 2(d) and 2(e), respectively. These networks represent a substantial distillation of the dynamics of the underlying biophysical system and can be used to simplify and explain the transition dynamics in a high-dimensional system without the need to consider its entire state space. In particular, for the range of edge widths shown, the optimized NEST in Fig. 2(e) has edges between all nodes except from lineage 3° to lineage 2°, indicating that a direct transition between these two states is highly unlikely whereas an indirect transition is possible; indeed, the two-step transition 3°→1°→2° has an overwhelmingly higher rate (102 times higher). By comparing with the NEST of the original system, shown in Fig. 2(d), this also demonstrates that direct transitions for one parameter regime can become indirect for another.

The OLAC method can be implemented directly on the NEST representation. Indeed, the objective function is naturally defined in terms of the transition matrix of the system, . As our application to the VPC system shows, the combined effect of optimizing this objective function is to vary the height of the transition barrier along the minimum action path between the stables states. This shows that OLAC itself does not require determining the full quasipotential of the system, which would be computationally prohibitive in high dimensions.

III. APPLICATIONS

A. Controlling Pancreas Cell Transdifferentiation

An important research problem in cellular reprogramming concerns the induction of insulin producing pancreatic β cells from non-insulin producing cell lineages; interventions capable of achieving this goal could lead to new treatments for type I diabetes. In order to computationally identify an optimal intervention to induce the desired reprogramming, we consider a ten-dimensional model of the hierarchical pancreas cell (HPC) differentiation [37]. The model has five stable fixed points—three representing differentiated endocrine pancreas cell types (α, β, δ) and two representing intermediate states (α/β and α/δ). The expression level of the ten regulatory genes, {xi}, are each assumed to be tunable independently through a factor σi (details of the model are given in Appendix B).

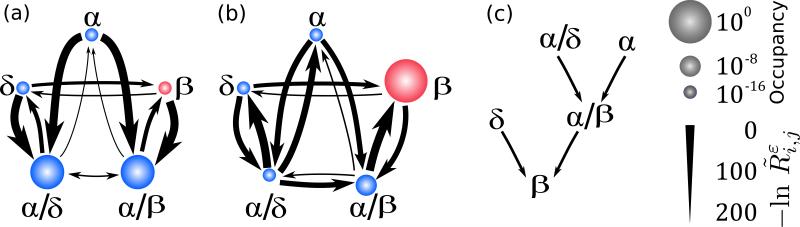

We first consider the uncontrolled model, in which σi = 1 for i = 1, . . . , 10. As shown in Fig. 3(a), in this case the two intermediate states attract the majority (> 99%) of the occupancy. Furthermore, transitions to the β state from the α and δ states occur at negligibly small rates (< 10−100), indicating that such lineage respecification effectively never occurs spontaneously. We apply OLAC to this model in order to identify the optimal combination of control actions that maximize the occupancy of the β state, ; the admissible interventions are limited to those for which no bifurcations occur, which is imposed using the same constraints as in the previous example. The optimal intervention that maximizes is a three-gene one, consisting of the downregulation of Brn4 and δ-gene combined with the upregulation of MafA. The resulting NEST for ε = 0.01 is shown in Fig. 3(b). Under this optimal intervention, the limiting occupancy of the β lineage goes from less than 0.01 to more than 0.99.

FIG. 3.

Controlled stochastic lineage switching in a multi-dimensional model of HPC differentiation. (a, b) NESTs of the model for the unmodified parameters (a) and for OLAC applied to optimize the limiting occupancy of the β cell state (red) (b), for ε = 0.01 In both panels, node size indicates the limiting occupancy of the state and edge width indicates the (negative of the) log transition rate. OLAC identifies that only three (out of ten) transcription factors need to be tuned in the model to optimize β-cell occupancy: MafA (increased), Brn4 (decreased), and δ-gene (decreased). (c) Transition hierarchy into the β cell state for the optimized system. Two states (δ and α/β) transition directly; two others (α and α/δ) require passage through an intermediate state—in this case α/β.

The analysis specifically shows the reliance of some, but not all, lineages on two-step transitions to reach the desired β lineage [Fig. 3(c)]. Previous research has suggested that indirect lineage respecifications might be suboptimal reprogramming strategies [38]. This is clearly the case for the δ → β reprogramming, which is optimized through a direct transdifferentiation event. For the α and α/δ lineages, however, with overwhelming likelihood the transformation to the β state will pass through the intermediate α/β state. Thus, which of the two cellular reprogramming strategies (direct or indirect) is optimal is context-dependent and cannot be determined without specification of the system, the initial state, and the final state. Systematically accounting for such context-dependence could lead to new advances in the development of cellular reprogramming technologies.

B. Predicting Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Targets

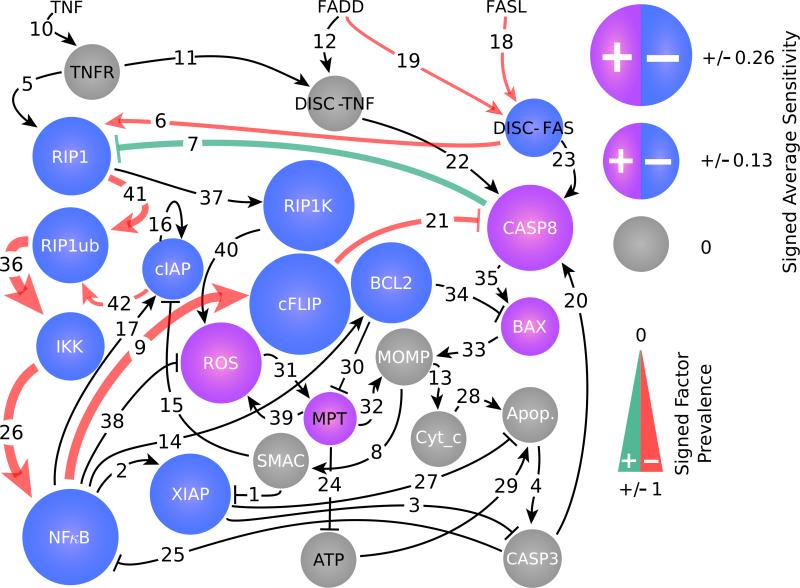

Evasion of apoptosis is one of the hallmarks of cancer cells [39]. As such, identifying tunable factors in the cell death pathway that effectively eliminate proliferative (or abnormal survival) cell states without harming healthy cells could lead to new therapeutic targets. To computationally identify candidate targets, we employ OLAC to analyze a reformulation of the Boolean model of the cell death pathway proposed in Ref. [40]. This reformulation is a continuous-variable model generated using the Hill-Cube methodology [41], which is more amenable to analysis and preserves all relevant properties of the original model, including the stable states. The model is comprised of 22 genes central to the programmed cell death and 42 parameters representing kinetic constants of the different reactions, which we denote by ci, i = 1, . . . 42 (Appendix B). It follows that two stable states form for all values of the parameters: apoptosis and necrosis. For a specific range of parameters representing healthy cells, a third state is also stable: the so-called naive state. For a different parameter range, however, a different stable state arises, corresponding to a survival cell type that is resistant to the apoptotic signal. This survival state represents cancer and is the focus of our discussion.

Our goal is to predict therapeutic targets that can induce transition from the survival state to the apoptotic state, without increasing the rate of apoptotic death in normal cell types or causing them to become survival cells. Although noise can in principle induce switches from the survival to the apoptotic state, only a fraction of the cells would transform as desired when both stable states exist. We therefore neglect the effect of noise temporarily and show that even in this case OLAC can be used to identify successful optimal interventions, which under these conditions lead to a bifurcation that completely eliminates the undesired (survival) state. To avoid inflammatory response, it is also desirable not to induce transitions to the necrotic state. These conditions are assured by taking G(Ω) = −S* (survival → apoptosis) as the objective function to be maximized, and by imposing the constraints ΔS*(naive → apoptotic) ≥ , ΔS* (naive → necrotic) ≥ , and S* (survival → necrotic) ≥ , where Δ indicates change under the control intervention and is taken to be 0.05 in our simulations. To encompass the largest possible set of candidate targets, we assume that any of the 42 parameters of the model can be tuned in experiments, and hence we take . However, since existing experimental techniques cannot be easily used to manipulate a large number of targets, we further constrain each control intervention to only involve a relatively small number of all tunable parameters. This can be achieved by stipulating that the sum of the absolute values of all changes to the parameters must be equal to a pre-specified intervention strength χ0, as detailed in Appendix C.

We thus apply OLAC to the cell death model for the objective function and constraints above. To account for genetic heterogeneity between cancer cells, we analyze six different survival cell types, represented here as six sets of unique values for the parameters Ω. These parameters represent nondimensional kinetic constants for each gene-gene interaction. In our simulations the individual uncontrolled parameters for these cell types are on average 0.50 ± 0.03 and the intervention strength χ0 is taken to be 0.1, 0.2, . . . 0.9 (Fig. S3, in the Supplemental Material [20], shows the breakdown of all cases). The number of parameters modified by optimal interventions tends to increase as χ0 increases, ranging from an average of 2.7 to 5.7 for χ0 varied from 0.1 to 0.9. For each cell type, a successful intervention (eliminating the survival state) is always achieved for large enough χ0 within this interval. On average, approximately only 5 out of the 42 parameters need to be modified in the optimal successful interventions. To put this result in perspective, we note that if the sparsity constraint in Eq. (C1) is disabled, OLAC leads to an average of no less than 40 modified parameters for a successful intervention. This constraint, which generalizes immediately to any system, is therefore effective to restrain the number of control parameters.

Figure 4 summarizes the results, showing that a unique subset of only 10 parameters is needed to form the (on average) 5-parameter successful target sets for any cell type. The biological functions and prevalence of these targets are explicitly indicated in Table S1 of the Supplemental Material [20]. Notably, only two targets are included in interventions found for all six cell types, namely the parameters whose predicted increase will decrease the activation of NFκB by IKK and the activation of IKK by RIP1ub (Fig. 4; parameters 26 and 36, respectively). The identification of these two targets is not entirely surprising since NFκB is a central regulator of the cell death pathway whose over-activation has been implicated in the cellular transition to cancer [42]; the consistent identification of both targets across all six cell types is an indication of the robustness of our approach. Aside from these global targets, OLAC also predicts unique combinations of targets for each cell type, in many cases indicating genes and interactions that have only recently been identified as possible cancer targets—e.g., the potential of suppressing the activation of cFLIP by NFκB [43] (Fig. 4; parameter 9). The identification of optimal target combinations that are unique to different cell types illustrates the potential of OLAC to assist the development of personalized therapeutic strategies as well as of interventions to address various forms of cancer [44] and to manipulate heterogeneous multistable cells in general [45–47].

FIG. 4.

Optimal therapeutic interventions for the cell death regulatory network model. The network has 22 genes (circles), 3 input parameters (top), and 42 target tunable parameters (edges), where the edge heads distinguish between excitatory (arrow) and inhibitory (bar) regulatory interactions. OLAC is applied to induce a bifurcation transition from survival to apoptotic states. The parameters involved in one or more optimal intervention are consistently upregulated (green) or downregulated (red) by the interventions; those not recruited by any optimal intervention are shown in black. The edge width indicates the prevalence of that parameter in optimal interventions for the various cell types and intervention strengths considered (up to the elimination of the survival state). The size of each circle represents the sensitivity of the gene to pro-apoptotic interventions, defined as the change in gene expression between the uncontrolled scenario and the smallest-intervention scenario at which the survival state is eliminated; the color distinguishes up- and down-expression. Genes in white are those that change expression substantially between the survival and apoptotic states. These results are based on 6 simulated cell types and 9 different intervention strengths (Supplemental Material [20], Fig. S3).

OLAC finds an optimal control action whether or not a bifurcation has been reached, allowing its effcacy and possible adverse effects to be monitored in experiments as the strength of the intervention is increased. Theoretically, the effcacy of an intervention can be defined as the relative reduction of the action associated with the transition from the survival state to the apoptotic state [Supplemental Material [20], Fig. S3(c)]. Experimentally, the effcacy can be more easily estimated by monitoring the predicted gene expression changes induced by the interventions [Supplemental Material [20], Fig. S3(b)]. As shown in Fig. 4 for interventions that eliminate the survival state, the sensitivity to the control interventions can vary widely across different genes. For example, in every cell type considered, the expressions of CASP3, SMAC, and CYT-c (among others) are predicted not to change at all until the elimination of the survival state; in contrast, cFLIP, IKK, and NFκB change expression in all cell types.

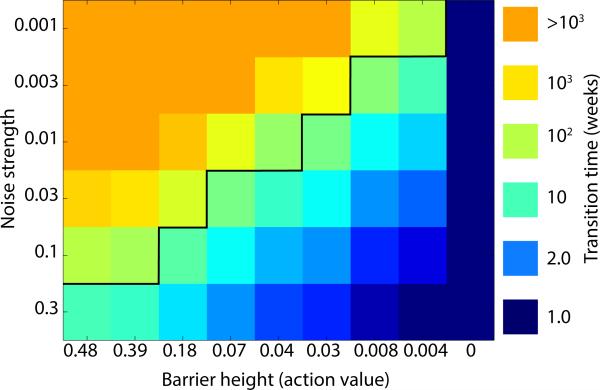

C. Biophysically Relevant Transition Times

In cases where OLAC identifies an intervention to induce a bifurcation to eliminate an undesired state, it is expected from experimental work in deterministically reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state (a prototypical example of an induced cell state transition) that such a transition will occur on a relatively short time scale, within approximately one week [48]. However, due to constraints on parameter changes, it may not always be possible to induce a bifurcation. To maintain biological relevance, the time scale over which these non-bifurcative interventions act should not be exceedingly long. Given a noise strength ε and a barrier height between two states, the approximate mean first exit time from that state can be estimated as [21]

| (6) |

where the transition time increases for lower noise levels and higher action barriers, as expected. Since in Eq. (6) is dimensionless, this quantity is best interpreted as a relative increase in transition time over the case of , which from above we take to be one week.

Figure 5 shows the mean first transition time using as a model application the cell death model considered in the previous section. The figure shows the mean transition time as a function of both noise level and barrier heights for a single cell type (as defined by each intervention strength in Fig. S3(c) of the Supplemental Material [20]). It follows that for cases where , the average transition time will be less than 20 weeks. This time scale is a reasonable upper limit for the biological relevance of any intervention: because transition times are exponentially distributed, interventions at this strength will cause a measurable fraction of the population to transition in just a couple of weeks. This benchmark thus provides a straightforward criterion to determine if an identified intervention will be relevant in practice. Figure 5 also demonstrates the important fact that it is not the size of the dynamical system that determines the switching time between states, but rather the ratio of the barrier height to the strength of the noise.

FIG. 5.

Transition time for the cell death model as a function of barrier height and noise strength. Transition time was calculated using Eq. (6). The black line separates those barrier height/noise strength combinations that occur over a therapeutically relevant time scale (bottom right) and those that do not (top left).

We expand on this approach in the Supplemental Material [20], Sec. S3, where we demonstrate that OLAC can be used to identify constrained interventions that achieve a desired limiting occupancy within a prespecified time frame. In that section we also generalize OLAC to systems with (multiplicative) noise that depends on the system state and to systems that are best modeled using a chemical kinetic formulation [49–51].

IV. DISCUSSION

The method proposed here, optimal least action control (OLAC), represents a new direction in the control of biophysical systems. Traditional control approaches for biophysical systems are based on manipulating the trajectories of the system, while our method is based instead on manipulating the epigenetic landscape through which these trajectories travel. This is achieved by effectively altering the barriers between different stable states in the quasipotential of the system, which could be achieved biologically through, for example, a genome editing approach [52]. In this way OLAC stands in contrast to other orthogonal methods that seek to control cellular states by directly modifying gene expression levels through, for example, siRNA strategies [53–55]. As such, our method naturally accounts for cellular noise and the incorporation of constraints on the possible control actions. But in contrast to previous work that has sought to construct the entire quasipotential for a dynamical system [56], we utilize the associated network of state transitions (NEST) to describe and control the system at a substantially reduced computational cost, which renders the approach applicable to a wide range of biophysical systems—including high-dimensional networks.

The cell death model example illustrates one of the key strengths of OLAC: its effectiveness when the problem involves an explosion in the number of possible reprogramming combinations. In practical applications to multi-parameter systems, it is of interest to identify interventions that are not only optimal but also sparse— i.e., that target only a few out of many possible tunable factors. Such sparsity is desired since most biologically realizable interventions are able to control only a few parameters and, for example, would not be able to directly control all parameters in the cell death model. Because OLAC can benefit from the framework of convex regularization, however, this combinatorial increase in the number of possible interventions can be dealt with easily by incorporating a sparsity constraint that has only marginal impact on the computational cost.

Another key property of the approach is its flexibility. For example, previous modeling approaches to explain reprogramming experiments have focused mainly on bifurcations that destabilize or eliminate states [57], which are comparatively larger changes in the dynamics of the system. These approaches do not benefit from the presence of noise and tacitly assume that, to reach the desired state, the initial state must become deterministically unstable or disappear, which, as demonstrated for the cell death model, may not be possible given a stringent enough set of constraints on the possible set of interventions. On the other hand, for being based on the Freidlin-Wentzell action, our method is effective as a unified approach both (i) to exploit the presence of noise for control in the absence of any bifurcation (as shown for the pancreas model and the cell death model with low intervention strengths) and (ii) to identify control interventions mediated by bifurcations in the absence of any noise (as shown for the cell death model with large intervention strengths). Therefore, instead of facing reduced performance in the presence of noise, which is a common drawback of other control approaches [53], OLAC benefits from the presence of noise, utilizing noise as an additional control tool.

Through the use of the approach introduced here we have shown that, counterintuitively, the optimal lineage respecification trajectory is often indirect; that is, they correspond to cases in which the most likely trajectory for an optimized transition between two states will pass through one or more intermediate stable states. Such cases cannot be anticipated by common sense since for a therapeutic intervention, for instance, an indirect path may cause the cells to worsen before they improve. This result suggests a new possible method for identifying enhanced reprogramming strategies, namely by systematically exploring combinations of intermediate transitions.

Our approach can also be applied to a much broader range of biophysical problems than those discussed in detail here. In particular, OLAC could be used in the context of synthetic biology, as researchers seek to build ever more complex synthetic systems and computer-aided design methods play an increasingly important role [58]. In that context, OLAC can identify optimal parameter tuning to reshape the quasipotential for the rational design of systems with pre-specified dynamical behavior and response to noise. The same approach can also be used to generate insights into epigenetic diseases and the mechanisms that give rise to them, including the possible dependence of their incidence rate on external versus genetic factors, as well as insights into potential preventive measures to reduce disease risks by identifying conditions that increase the barriers for transitions to disease states.

Furthermore, the foundation of OLAC in the Freidlin-Wentzell action means that the applications of this method need not be biophysical. In particular, our method can easily be used to predict control interventions in other noisy multistable networks and, along with NEST, to characterize the basins of attraction of these systems [59]. For example, in the Supplemental Material [20], Sec. S4, we construct the NEST for a dynamical system with more than 100 attractors [60] and demonstrate that even in a system with such substantial multistability, noise can effectively eliminate the occupancy of the majority of attractors, leaving only a small fraction of them occupied. Moreover, along with the already mentioned applications to power-grids, polymer networks, and food-web networks, OLAC could also find use in controlling spreading processes on social networks [61], in inducing synchronization patterns in oscillator networks [62], in manipulating associative memory networks [63], and potentially in creating new attractors [64]. Further development of this method could also expand its applications to models of disease epidemics and population dynamics. In particular, substantial foundational work has been done on the modeling of extinction events in such systems, which typically requires model-specific mathematical analysis [65–67]. Because a white-noise approximation, like in Eq. (1), cannot accurately approximate the dynamics of these systems [68], expanding OLAC to apply to extinction events in larger networks will require using situation-specific calculations of the transition rates.

Ultimately, we believe that OLAC—together with NEST—forms a flexible, scalable method which can be used to understand and control the dynamical stability and response to noise of a wide range of complex networks, including those with large number of dynamical variables, tunable parameters, and attractors. The method is easily implementable, with a ready-to-use numerical implementation included as supplemental files [20]. The method requires no a priori information (beyond those implicitly defined by the dynamical equations) about how variations in the control parameters a ect the system, and it can be used in concert with rather general constraints on the control actions. While OLAC can be applied to many systems, as formulated here application of the method requires a quantitative dynamical model. Extending the method to systems for which no model is available is an important direction for future research. Future work is also expected to expand on the applications of the approach and to further demonstrate its experimental efficacy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jorge Nocedal for insightful discussions on optimization methods, and members of the Leonard and Thomas-Elliott labs for continued support. This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute Grants No. 1U54CA143869 (NU PS-OC) and No. 1U54CA193419 (Chicago area PS-OC), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant R01GM113238, the National Science Foundation Grant No. DMS-1057128, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium, and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Appendix A: Calculating the Minimum Action Value

The minimum action is determined using

| (A1) |

where and denote the coordinates of the initial and final stable states, respectively. To solve this optimization problem we minimize the discretized version of the functional [22], given by

| (A2) |

where we use T1 = t0 < t1 < · · · < tms = T2, Δtn = tn – tn–1, , and . In our simulations we set T2 = –T1 = 20 and ms = 100, and verified that larger values of T2 – T1 and ms would not improve accuracy noticeably.

To maximize e ciency, we regularly remesh the path from the time domain to the space domain and adaptively redefine tn according to

| (A3) |

where Δαn = 1/ms, tn–1/2 = (tn + tn−1)/2, and is the monitor function measuring the speed along the path. We used the initial tn evenly spaced and C = 1010. These calculations require an initial path between the stable states. The numerical results we report are obtained using a straight line as the initial path. We have checked that using different initial paths, such as those generated through the Brownian bridge approach [69], the simulation always converges to the same optimal paths.

We note that, since the parameters of the system are modified at each step of OLAC, robust numerical continuation of the equilibria is necessary. We use a simple homotopy method to continue the stable states from initial parameters Ω′ to terminal parameters Ω″. Specifically, we use linear interpolation between these parameter values combined with a Newton step [70]. The latter includes checking at each step that the desired states are not lost to unintended bifurcations.

All optimization procedures are done employing the interior-point algorithm in the fmincon function of the optimization toolbox of MATLAB [71]. A MATLAB implementation of OLAC in included as supplemental files (see Supplemental Material [20], Sec. S2, for details).

Appendix B: Equations of the Models Considered

VPC Differentiation Model

The deterministic component of the VPC model [24] is given by

| (B1) |

where , , , and . This is an effective representation of the combined effects of EGF and Notch signaling, whose signaling strengths are determined by and , respectively. The other parameters are τ = 2.18, , , and .

HPC Differentiation Model

The deterministic component of the HPC differentiation model is [37]

| (B2) |

where (as, ae, a, kdeg, μ, μm, h) = (2.2, 6.0, 4.0, 1.0, 0.25, 0.125, 4.0) are the fixed parameters in these equations. Each parameter σi represents a tunable factor to alter the expression of the gene represented by xi.

Cell Death Model. The cell death model was converted from the Boolean model [40] (available at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels-main/MODEL0912180000) into a continuous version using the Odefy package [41]. The system has 22 variables, representing gene products, and 42 tunable parameters. In addition, the model has 3 input parameters that do not change in time, and 3 output variables that indicate the state of the cell (distinct combinations of which indicate whether the cell is in the survival, apoptotic, necrotic, or naive state).

Appendix C: Implementing the Sparsity Constraint

In many biological systems there are dozens or hundreds of parameters that could potentially be changed, but in general only a few of them can be changed in any one intervention. To identify the few most promising targets from a large field of possible ones we employ a sparsity constraint. The constraint is implemented as

| (C1) |

where, as above, Δ denotes the change due to the control action. While the condition in Eq. (C1) is by itself consistent with all parameters being altered, optimization under this constraint (as the one invoked by OLAC) is expected to lead to a reduced number of modified parameters. The basis for this conclusion is that this constraint works similarly to well-established methods of convex regularization, which are known to lead to sparsity under general conditions [72]. The specific number of modified parameters as well as success rate will generally depend on χ0, and this dependence can be explored as an additional control factor. This formulation has the remarkable advantage of involving only one optimization step, and hence avoids the combinatorial explosion that would be involved in testing all combinations of possible “|Ω| choose k” tunable factors. Indeed, an exhaustive strategy would be computationally prohibitive since testing for all k would require 2|Ω| – 1 optimization steps, which is > 1012 for |Ω| = 42. Naturally, if a particular parameter is not targetable under the given conditions, such information can be directly be incorporated into our analysis.

References

- 1.Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Nature, Nurture, or Chance: Stochastic Gene Expression and Its Consequences. Cell. 2008;135:216. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAdams HH, Arkin A. Stochastic Mechanisms in Gene Expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;95:814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balazsi G, van Oudenaarden A, Collins J. Cellular Decision Making and Biological noise: From Microbes to Mammals. Cell. 2011;144:910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang HH, Hemberg M, Barahona M, Ingber DE, Huang S. Transcriptome-Wide Noise Controls Lineage Choice in Mammalian Progenitor Cells. Nature (London) 2008;453:544. doi: 10.1038/nature06965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi PJ, Cai L, Frieda K, Xie XS. A Stochastic Single-Molecule Event Triggers Phenotype Switching of a Bacterial Cell. Science. 2008;322:442. doi: 10.1126/science.1161427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, Shapira SD, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Lander ES. Stochastic State Transitions Give Rise to Phenotypic Equilibrium in Populations of Cancer Cells. Cell. 2011;146:633. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaffer CL, et al. Normal and Neoplastic Nonstem Cells Can Spontaneously Convert to a Stem-Like State. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:7950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddington CH. The Strategy of the Genes. Allen and Unwin; London: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, Eichler G, Bar-Yam Y, Ingber DE. Cell Fates as High-Dimensional Attractor States of a Complex Gene Regulatory network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:128701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.128701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acar M, Becskei A, van Oudenaarden A. Enhancement of Cellular Memory by Reducing Stochastic Transitions. Nature (London) 2005;435:228. doi: 10.1038/nature03524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishimatsu K, Hata T, Mochizuki A, Sekine R, Yamamura M, Kiga D. General Applicability of Synthetic Gene-Overexpresssion for Cell-Type Ratio Control via Reprogramming. ACS. Synth. Biol. 2014;3:638. doi: 10.1021/sb400102w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai L, Vorselen D, Korolev K, Gore J. Generic Indicators for Loss of Resilience Before a Tipping Point Leading to Population Collapse. Science. 2012;336:1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1219805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanna J, Saha K, Pando B, van Zon J, Lengner CJ, Creyghton MP, van Oudenaarden A, Jaenisch R. Direct Cell Reprogramming is a Stochastic Process Amenable to Acceleration. Nature (London) 2009;462:595. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The Promise of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Research and Therapy. Nature (London) 2012;481:295. doi: 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S, Kauffman S. How to Escape the Cancer Attractor: Rationale and Limitations of Multi-Target Drugs. Semin. Cancer. Biol. 2013;23:270. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creixell P, Schoof EM, Erler JT, Linding R. Navigating Cancer Network Attractors for Tumor-Specific Therapy. Nat. Biotech. 2012;30:842. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motter AE, Myers SA, Anghel M, Nishikawa T. Spontaneous Synchrony in Power-Grid Networks. Nat. Phys. 2013;9:191. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnurr B, Gittes F, MacKintosh FC. Metastable Intermediates in the Condensation of Semiflexible Polymers. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;65:061904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.061904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahasrabudhe S, Motter AE. Rescusing Ecosystems from Extinction Cascades Through Compensatory Perturbations. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:170. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.See Supplemental Material for generalizations of OLAC, additional analyses, supplemental table, supplemental figures, and supplemental references..

- 21.Freidlin MI, Wentzell AD. Random Perturbations of Dynamical Systems. Springer; Berlin: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Ren W, W. E. Adaptive Minimum Action Method for the Study of Rare Events. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:104111. doi: 10.1063/1.2830717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maier R, Stein D. Limiting Exit Location Distributions in the Stochastic Exit Problem. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1997;57:752. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corson F, Siggia ED. Geometry, Epistasis, and Developmental Patterning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:5568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201505109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sternberg PW. Vulval Development. WormBook: The online review of C. elegans biology. 2005;1 doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.6.1. 10.1895/worm-book.1.6.1, http://wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nocedal J, Wright SJ. Numerical Optimization. Springer; Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smelyanskiy VN, Dykman MI. Optimal Control of Large Fluctuations. Phys. Rev. E. 1997;55:2516. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross J, Dykman MI, Mori E, Hunt PM. Large fluctuations and Optimal Paths in Chemical Kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;100:5735. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pisarchik AN, Feudel U. Control of multistability. Phys. Rep. 2014;540:167. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vugmeister BE, Rabitz H. Cooperating with non-equilibrium fluctuations through their optimal control. Phys. Rev. E. 1997;55:2522. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindley BS, Schwartz IB. An Iterative Action Minimizing Method for Computing Optimal Paths in Stochastic Dynamical Systems. Phys. D. 2013;255:22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billings L, Schwartz IB, McCrary M, Korotkov AN, Dykman MI. Switching Exponent Scaling Near Bifurcation Points for Non-Gaussian Noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;104:140601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.140601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker OM, Karplus M. The Topology of Multidimensional Potential Energy Surfaces: Theory and Application to Peptide Structure and Kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;106:1495. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao F, Caflisch A. The Protein Folding Network. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:299. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang RS, Saadatpour A, Albert R. Boolean Modeling in Systems Biology: an Overview of Methodology and Applications. Phys. Biol. 2012;9:055001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/5/055001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noe F, Fischer S. Transition Networks for Modeling the Kinetics of Conformational Change in Macromolecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:154. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou JX, Brusch L, Huang S. Predicting Pancreas Cell Fate Decisions and Reprogramming with a Hierarchical Multi-Attractor Model. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e14752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passier R, Mummery C. Getting to the Heart of the Matter: Direct Reprogramming to Cardiomyocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:139. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calzone L, Tournier L, Fourquet S, Thieffrey D, Zhivotovsky B, Barillot E, Zinovyev A. Mathematical Modeling of Cell-Fate Decision in Response to Death Receptor Engagement. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittmann DM, Krumsiek J, Saez-Rodriguez J, Lauffenburger DA, Klamt S, Theis FJ. Transforming Boolean Models to Continuous Models: Methodology and Application to T-cell Receptor Signaling. BMC Sys. Biol. 2009;3:98. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo JL, Kamata H, Karin M. IKK/NF-κB Signaling: Balancing Life and Death—a New Approach to Cancer Therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2625. doi: 10.1172/JCI26322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safa AR. c-Flip, a Master Anti-Apoptotic Regulator. Exp. Oncol. 2012;34:176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saadatpour A, Wang R, Liao A, Liu X, Loughran TP, Albert I, Albert R. Dynamical and structural analysis of a t-cell survival network identifies novel candidate therapeutic targets for large granular lymphocyte leukemia. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regan ER, Aird WC. Dynamical Systems Approach to Endothelial Heterogeneity. Circ. Res. 2012;111:110. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lang AH, Li H, Collins JJ, Mehta P. Epigenetic Landscapes Explain Partially Reprogrammed Cells and Identify Key Reprogramming Genes. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinway SN, Zañudo JGT, Ding W, Rountree CB, Feith DJ, Loughran TP, Jr., Albert R. Network Modeling of TGFβ Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Reveals Joint Sonic Hedgehog and Wnt Pathway Activation. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5963. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rais Y, Zviran A, Geula S, Gafni O, Chomsky E, Viukov S, AlFatah Mansour A, Caspi I, Krupalnik V, Zerbib M. Deterministic Direct Reprogramming of Somatic Cells to Pluripotency. Nature (London) 2013;502:65. doi: 10.1038/nature12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turner TE, Schnell S, Burrage K. Stochastic Approaches for Modelling In Vivo Reactions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2004;18:165. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu D. Optimal Transition Paths of Stochastic Chemical Kinetic Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:164104. doi: 10.1063/1.2191487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu D. A Numerical Scheme for Optimal Transition Paths of Stochastic Chemical Kinetic Systems. J. Comp. Phys. 2008;227:8672. doi: 10.1063/1.2191487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., III ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-Based Methods for Genome Engineering. Trends in Biotechnol. 2013;31:397. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cornelius SP, Kath WL, Motter AE. Realistic Control of Network Dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1942. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xia H, Mao Q, Paulson H, Davidson BL. siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1006. doi: 10.1038/nbt739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zañudo JGT, Albert R. Cell Fate Reprogramming by Control of Intracellular Network Dynamics. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Zhang K, Xu L, Wang E. Quantifying the Waddington Landscape and Biological Paths for Development and Differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:8257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017017108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chickarmane V, Peterson C. A Computational Model for Understanding Stem Cell, Trophectoderm and Endoderm Lineage Determination. PLOS ONE. 2008;3:e3478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marchisio M, Stelling J. Computational Design Tools for Synthetic Biology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:479. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menck PJ, Heitzig J, Marwan N, Kurths J. How Basin Stability Complements the Linear-Stability Paradigm. Nat. Phys. 2013;9:89. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feudel U. Complex Dynamics in Multistable Systems. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 2008;18:1607. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granovetter M. Threshold Models of Collective Behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978;83:1420. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abrams DM, Strogatz SH. Chimera States for Coupled Oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:174102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.174102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hopfield JJ. Neural Networks and Physical Systems with Emergent Computational Abilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1982;79:2554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Campbell C, Albert R. Stabilization of Perturbed Boolean Network Attractors Through Compensatory Interactions. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamenev A, Assaf M, Meerson B. Population extinction in a time-modulated environment. Phys. Rev. E. 2008;78:041123. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.041123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwartz IB, Dykman MI, Landsman AS. Disease Extinction in the Presence of Random Vaccination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:078101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.078101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khasin M, Dykman MI. Extinction rate fragility in population dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;103:068101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.068101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sargsyan KV, Doering CR, Sander LM. Extinction times for birth-death processes: exact results, continuum asymptotics, and the failure of the Fokker–Planck approximation. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2005;3:283. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karatzas I, Shreve SE. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer; Berlin: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seydel R. From Equilibrium to Chaos: Practical Bifurcation and Stability Analysis. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 71.MATLAB version 8.1.0.604. Natick, Massachusetts; The MathWorks Inc.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyd S, Vandenberghe L. Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.