Abstract

The photovoltaic (PV) effect in polar materials offers great potential for light-energy conversion that generates a voltage beyond the bandgap limit of present semiconductor-based solar cells. Ferroelectrics have received renewed attention because of the ability to deliver a high voltage in the presence of ferroelastic domain walls (DWs). In recent years, there has been considerable debate over the impact of the DWs on the PV effects, owing to lack of information on the bulk PV tensor of host ferroelectrics. In this article, we provide the first direct evidence of an unusually large PV response induced by ferroelastic DWs—termed ‘DW’-PV effect. The precise estimation of the bulk PV tensor in single crystals of barium titanate enables us to quantify the giant PV effect driven by 90° DWs. We show that the DW-PV effect arises from an effective electric field consisting of a potential step and a local PV component in the 90° DW region. This work offers a starting point for further investigation into the DW-PV effect of alternative systems and opens a reliable route for enhancing the PV properties in ferroelectrics based on the engineering of domain structures in either bulk or thin-film form.

The photovoltaic (PV) effect in polar materials has attracted substantial interest, because the photoconversion mechanism can be exploited for the development of advanced solar cells that generate a high voltage. The bulk PV effect has been extensively studied in ferroelectric oxides1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, compound semiconductors9,10 and fluoride polymers11. The introduction of transition-metal atoms into the host lattices has been shown to be effective in enhancing the bulk PV effect under visible-light irradiation, because defect states in the bandgap result in light absorption and the subsequent charge separation5,12.

Recent studies on ferroelectric thin films have demonstrated that bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3: BFO) with ferroelastic domain walls (DWs) delivers above-bandgap voltages that can be tuned by the number of the DWs13. An internal quantum efficiency in the DWs has been reported as high as 10%14. The microscopic origin of the high photovoltage is shown to originate from an electrostatic potential step at the DWs. Meanwhile, the temperature-dependent PV studies have revealed that BFO films generate a high photovoltage by controlling the conductivity of the DWs15. This anomalous PV effect is thought to be due to the bulk PV effect, not to the electrostatic potential step at the DWs. Essentially, the bulk PV effect arises from spatial symmetry breaking in polar materials16,17 and can be described in terms of the bulk PV tensor18. Recent theoretical calculations19,20,21,22 and atomic-scale microscopy23,24 have shown that spatial symmetry breaking is preserved in the local region of the ferroelastic DWs. These studies suggest that the DW region inherently has a local PV component similar to the bulk PV effect in addition to the electrostatic potential step.

Until now, there has been considerable debate over the mechanism of the PV effects in ferroelectrics in the presence of ferroelastic DWs, owing to lack of information on the bulk PV tensor of the host crystals. In this article, we present the first direct evidence that ferroelastic DWs deliver an anomalously large PV response in a perovskite ferroelectric crystal. We term it the ‘DW’-PV effect. We select barium titanate (BaTiO3: BT) as a model system to investigate these effects. The precise estimation of the bulk PV tensor allows us to quantify the contribution of 90° DWs in BT single crystals, revealing that the field strength due to the DW-PV effect is far beyond the bulk PV effect. We show that this extremely large field stems from an effective electric field consisting of a potential step and a local PV component in the 90° DW region.

Results

We evaluated the PV properties of the single crystals of Mn-doped BT (Mn-BT) in three different configurations shown in Fig. 1. The electronic mechanism of the photocurrent properties under visible-light irradiation in Mn-BT has been reported in ref.12. Here, we focus on the impact of 90° DWs on the PV properties. Throughout this paper, we denote photocurrent density vector by J, bias voltage by Vbias. We define short-circuit current density (JSC) as the J value at Vbias = 0 and open-circuit voltage (VOC) as the Vbias value at J = 0.

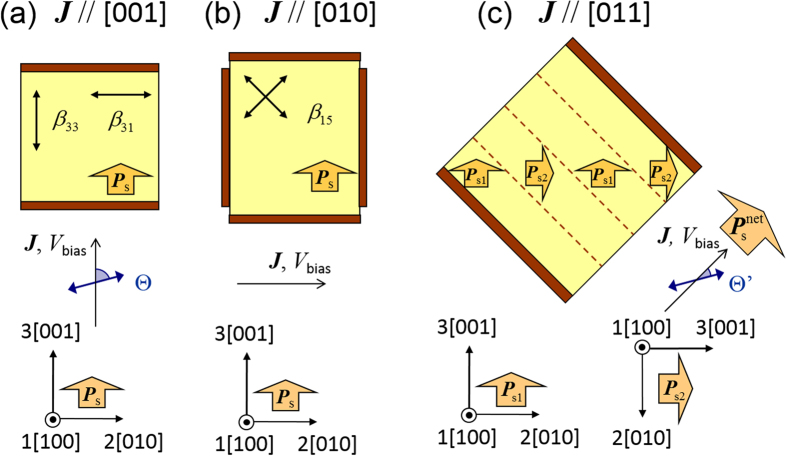

Figure 1.

Electrode configurations with respect to the crystal axes: (a) J//[001], (b) J//[010] and (c) J//[011]. The light-polarizations (Θ and  are defined as the angles between the polarization plane of light and the measured direction of J. The two-headed black arrows written with the components of bulk PV tensor (β33, β31 and β15) represent the light-polarization of the corresponding components.

are defined as the angles between the polarization plane of light and the measured direction of J. The two-headed black arrows written with the components of bulk PV tensor (β33, β31 and β15) represent the light-polarization of the corresponding components.

J - V bias characteristics

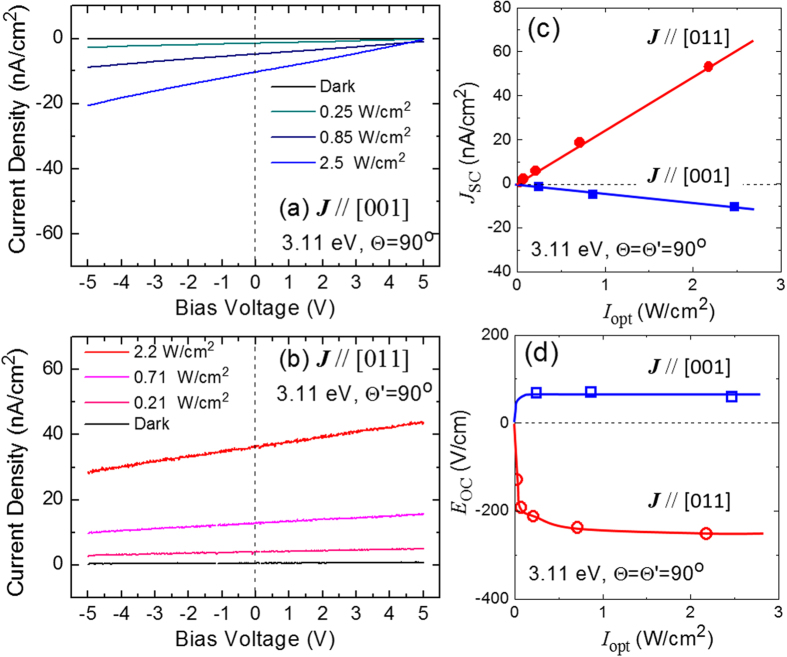

Figure 2a-2b represent the J - Vbias characteristics of the Mn-BT samples in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations, respectively, under light irradiation (3.11 eV, Θ =  = 90°). In the both configurations, we confirmed a linear relation between J and Vbias. It is worth noting that the signs of JSC and of VOC are different between the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations. That is, the photocurrent flows in the direction opposite to the spontaneous polarization (Ps) in the single-domain state (Fig. 2a) whereas the photocurrent is generated in the same direction as the net spontaneous polarization

= 90°). In the both configurations, we confirmed a linear relation between J and Vbias. It is worth noting that the signs of JSC and of VOC are different between the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations. That is, the photocurrent flows in the direction opposite to the spontaneous polarization (Ps) in the single-domain state (Fig. 2a) whereas the photocurrent is generated in the same direction as the net spontaneous polarization  in the 90° domain structure (Fig. 2b).

in the 90° domain structure (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Current density - voltage characteristics of the Mn-doped BT samples in (a) the J//[001] and (b) the J//[011] configurations. The light-polarization is fixed perpendicular to the measurement directions of photocurrent (Θ = 90°,  . (c) Short-circuit current density (JSC) as a function of light intensity

. (c) Short-circuit current density (JSC) as a function of light intensity  . The solid lines are the linear fitting results. (d) Open-circuit electric field (EOC) as a function of

. The solid lines are the linear fitting results. (d) Open-circuit electric field (EOC) as a function of  . The solid curves are guides to the eye. Note that the signs of JSC are opposite in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations.

. The solid curves are guides to the eye. Note that the signs of JSC are opposite in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations.

In Fig. 2c-2d we plot the light intensity  dependences of JSC and open-circuit electric field (EOC). While JSC is proportional to

dependences of JSC and open-circuit electric field (EOC). While JSC is proportional to  , EOC saturates in the high-

, EOC saturates in the high- region above ~1 W/cm2. Hereafter we discuss this high-

region above ~1 W/cm2. Hereafter we discuss this high- region, where the dark conductivity is negligible.

region, where the dark conductivity is negligible.

Values of the photoconductivity,  , estimated from the slope of the J - Vbias data (Fig. 2a,b) are proportional to

, estimated from the slope of the J - Vbias data (Fig. 2a,b) are proportional to  and the proportional constants

and the proportional constants  in both configurations are tabulated in Table 1. We note that

in both configurations are tabulated in Table 1. We note that  is almost the same in both the configurations. The 90° DWs that are present in the J//[011] samples do not affect the overall behaviour of σph. This experimental result provides the fundamental basis for identifying the DW-PV effect, as described below.

is almost the same in both the configurations. The 90° DWs that are present in the J//[011] samples do not affect the overall behaviour of σph. This experimental result provides the fundamental basis for identifying the DW-PV effect, as described below.

Table 1. Current density - voltage characteristics of the Mn-doped BT samples in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations under light irradiation (hv = 3.11 eV, Θ = Θ′ = 90°).

| J//[001] | J//[011] | |

|---|---|---|

(nA/W) (nA/W) |

−4.2 | +15.8 |

| EOC (V/cm) | +59.1 | −254 |

(pS cm/W) (pS cm/W) |

76 | 68 |

The photoconductivity (σph) is defined as  .

.

Light-polarization dependence of J SC

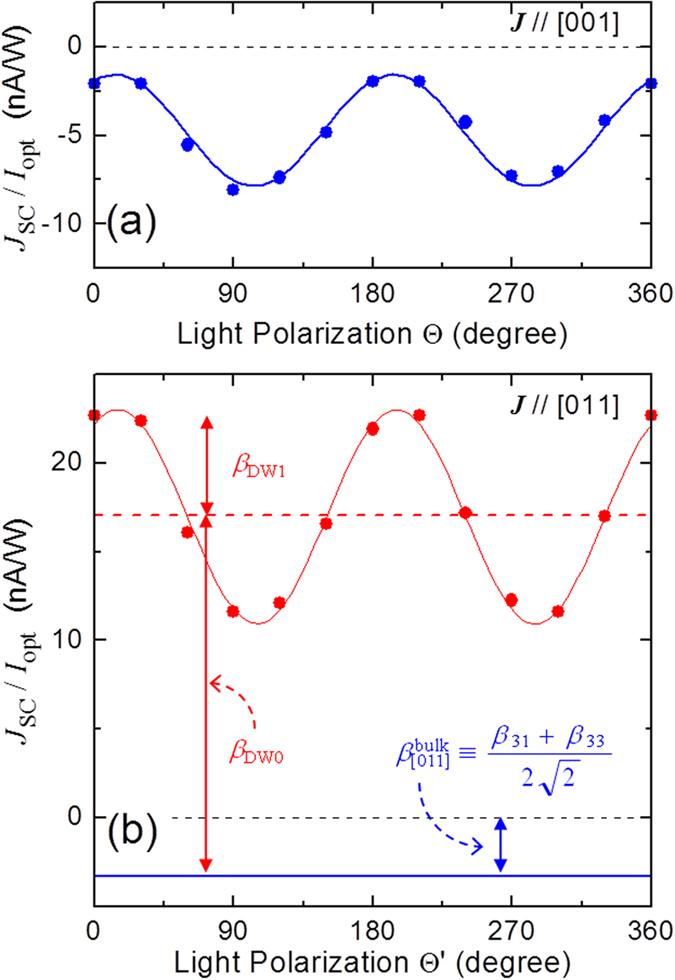

In Fig. 3 we plot the short-circuit photocurrent density normalized by the light intensity  observed for the Mn-BT samples in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations. In both of the configurations we could confirm a strong dependence of JSC on the light-polarization.

observed for the Mn-BT samples in the J//[001] and the J//[011] configurations. In both of the configurations we could confirm a strong dependence of JSC on the light-polarization.

Figure 3.

Photocurrent densities normalized by light intensity  as a function of the light-polarization (Θ or

as a function of the light-polarization (Θ or  in (a) the J//[001] and (b) the J//[011] configurations. The photon energy (hv) is 3.11 eV. Solid lines denote the fitting results.

in (a) the J//[001] and (b) the J//[011] configurations. The photon energy (hv) is 3.11 eV. Solid lines denote the fitting results.

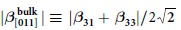

According to the bulk PV tensor in the tetragonal BT system [see Eq. (5) in Method], the photocurrent density in the J//[001] configuration  can be written by

can be written by

|

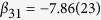

The fitting of the data shown in Fig. 3a leads to  nA/W and

nA/W and  nA/W at

nA/W at  eV. The standard deviations of these parameters are shown in parenthesis and estimated to be ~5% at most.

eV. The standard deviations of these parameters are shown in parenthesis and estimated to be ~5% at most.

From the results measured in the J//[010] configuration (Fig. 1b) we conclude that  is smaller than the detection limit of our measurement system, i.e., ~3 pA/W. Since the

is smaller than the detection limit of our measurement system, i.e., ~3 pA/W. Since the  value of ~3 pA/W is two orders of magnitude smaller than those of other components

value of ~3 pA/W is two orders of magnitude smaller than those of other components  and

and  , we neglect β15 throughout this paper.

, we neglect β15 throughout this paper.

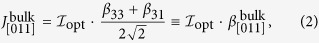

In the J//[011] configuration (Fig. 3b) we found that the photocurrent flows in the same direction as  , which cannot be explained by the bulk PV effect as described below. The poling in the J//[011] configuration leads to a domain structure in which two kinds of spontaneous polarizations (Ps1 and Ps2) with different orientations are present with the 90° DWs. The photocurrent density in the J//[011] configuration arising from the bulk PV effect

, which cannot be explained by the bulk PV effect as described below. The poling in the J//[011] configuration leads to a domain structure in which two kinds of spontaneous polarizations (Ps1 and Ps2) with different orientations are present with the 90° DWs. The photocurrent density in the J//[011] configuration arising from the bulk PV effect  can be expressed by

can be expressed by

|

which is independent of the light-polarization  . The derivation of Eq. (2) based on effective electric fields is given in Supplementary Information.

. The derivation of Eq. (2) based on effective electric fields is given in Supplementary Information.

In Fig. 3b we also put the contribution of  expected from Eq. (2). We note a considerable component of positive JSC with a strong dependence on

expected from Eq. (2). We note a considerable component of positive JSC with a strong dependence on  , which goes beyond the bulk PV effect with a negative constant

, which goes beyond the bulk PV effect with a negative constant  . The experimental fact that

. The experimental fact that  takes almost the same value regardless of the presence or absence of the DWs leads us to consider that the

takes almost the same value regardless of the presence or absence of the DWs leads us to consider that the  -dependent, positive

-dependent, positive  is not relevant to σph. These results strongly support the conclusion that the behaviour of JSC//[011] does originate from the 90° DWs. The thickness (wDW) of the 90° DW region is reported to be 2–100 nm25,26,27,28,29,30. Since wDW is two to three orders of magnitude smaller than the DW spacing (W ~ 15 μm), the large value of JSC//[011] appears to arise from a giant PV effect in the local region of the 90° DWs.

is not relevant to σph. These results strongly support the conclusion that the behaviour of JSC//[011] does originate from the 90° DWs. The thickness (wDW) of the 90° DW region is reported to be 2–100 nm25,26,27,28,29,30. Since wDW is two to three orders of magnitude smaller than the DW spacing (W ~ 15 μm), the large value of JSC//[011] appears to arise from a giant PV effect in the local region of the 90° DWs.

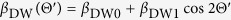

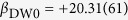

We define  as the difference between the measured

as the difference between the measured  and the bulk PV effect

and the bulk PV effect  . Using the following functional form:

. Using the following functional form:  , where βDW0 and βDW1 correspond to the positive offset and the amplitude, respectively, the fitting yields

, where βDW0 and βDW1 correspond to the positive offset and the amplitude, respectively, the fitting yields  nA/W and

nA/W and  nA/W. We emphasize that

nA/W. We emphasize that  is not calculated locally in the DW region but is averaged over the entire samples.

is not calculated locally in the DW region but is averaged over the entire samples.

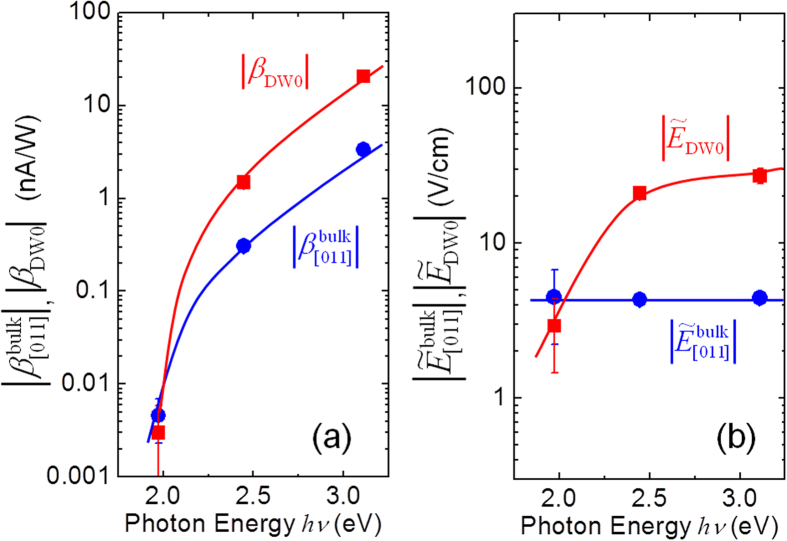

The bulk PV effect vs. the DW-PV effect

The results measured at three wavelengths (λ = 405, 515 and 639 nm) are summarized in Table 2. Here we focus on the positive offset  and the bulk PV effect

and the bulk PV effect  of the Mn-BT samples, which are plotted as a function of hv in Fig. 4a. Except for the data at hv = 1.97 eV, which are comparable to the detection limit of ~3 pA/W, we note that

of the Mn-BT samples, which are plotted as a function of hv in Fig. 4a. Except for the data at hv = 1.97 eV, which are comparable to the detection limit of ~3 pA/W, we note that  is 5–10 times as large as

is 5–10 times as large as  .

.

Table 2. The non-zero components of the bulk PV tensor (β31 and β 33) and the coefficients of the DW-PV effect (βDW0 and β DW1).

| Mn-BT |

BT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 405 nm(3.11 eV) | 515 nm(2.45 eV) | 639 nm(1.97 eV) | 405 nm(3.11 eV) | 515 nm(2.45 eV) | |

| β31 (nA/W) | −7.86(23) | −0.70(3) | −0.003(3) | −0.116(5) | −0.013(3) |

| β33 (nA/W) | −1.57(4) | −0.17(1) | −0.010(3) | −0.004(3) | −0.003(3) |

(nA/W) (nA/W) |

−3.33(28) | −0.31(4) | −0.005(6) | −0.043(8) | −0.006(5) |

| βDW0 (nA/W) | +20.34(61) | +1.47(4) | +0.003(3) | +0.48(2) | +0.013(3) |

| βDW1 (nA/W) | +6.06(18) | +0.74(3) | +0.003(3) | +0.27(1) | +0.003(3) |

The calculated values of  are also shown. For the DW-PV effect, the functional form of

are also shown. For the DW-PV effect, the functional form of  is assumed. The photocurrents of the BT samples under light illumination with a photon energy (hv) of 1.97 eV were smaller than the detection limit of our measurement system. The standard deviations of these parameters are shown in parenthesis.

is assumed. The photocurrents of the BT samples under light illumination with a photon energy (hv) of 1.97 eV were smaller than the detection limit of our measurement system. The standard deviations of these parameters are shown in parenthesis.

Figure 4.

Comparison of bulk PV effect with DW-PV effect of Mn-BT: (a)  and

and  , (b) corresponding effective electric fields

, (b) corresponding effective electric fields  and

and  . The solid curves are guides to the eye. The standard deviation of each data point is shown as an error bar.

. The solid curves are guides to the eye. The standard deviation of each data point is shown as an error bar.

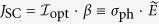

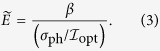

As described above, we found that σph does depend neither on the light-polarization nor on the crystal orientation nor on the presence/absence of the DWs. We can thus express JSC using effective electric field  as

as  and define the effective electric field

and define the effective electric field  for representing the PV effect by

for representing the PV effect by

|

Here  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  for the bulk PV effect and to

for the bulk PV effect and to  for the DW-PV effect, where β corresponds to its respective

for the DW-PV effect, where β corresponds to its respective  and βDW0. Considering the linear current - voltage characteristics and the independence of

and βDW0. Considering the linear current - voltage characteristics and the independence of  on

on  ,

,  is identical to the open-circuit electric field (EOC).

is identical to the open-circuit electric field (EOC).

In Fig. 4b we plot the  and

and  values as a function of hv. We found that

values as a function of hv. We found that  does not depend on hv, which seems to be a specific feature of the bulk PV effect. Even though the DW-PV effect occurs in an extremely small volume only in the 90° DW region, the resultant effective field averaged over the entire samples

does not depend on hv, which seems to be a specific feature of the bulk PV effect. Even though the DW-PV effect occurs in an extremely small volume only in the 90° DW region, the resultant effective field averaged over the entire samples  is large compared with

is large compared with  . These experimental results provide direct evidence that the 90° DWs deliver a giant PV effect. Taking into account that

. These experimental results provide direct evidence that the 90° DWs deliver a giant PV effect. Taking into account that  is significantly small at 1.97 eV and that

is significantly small at 1.97 eV and that  indicates a sharp decrease in the hv range of 2.0–2.5 eV, we speculate that the DW-PV effect due to βDW0 is activated at above a threshold of hv, the reason of which is still under investigation.

indicates a sharp decrease in the hv range of 2.0–2.5 eV, we speculate that the DW-PV effect due to βDW0 is activated at above a threshold of hv, the reason of which is still under investigation.

Discussion

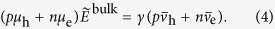

The bulk PV effect stems from an asymmetry in the photogenerated carrier dynamics in polar materials and can be interpreted in terms of effective electric fields. We introduce a single parameter (γ) representing the asymmetry in the photogenerated carrier density and relate the effective electric field  ( = JSC/σph) with γ as

( = JSC/σph) with γ as

|

Here n and p denote electron density and hole density, μe and μh their mobilities. We also define  and

and  as the averaged drift velocities projected onto the Ps direction where the average is taken over a solid angle of 2π. The derivation of Eq. (4) is given in Supplementary Information. As shown in Fig. 4b

as the averaged drift velocities projected onto the Ps direction where the average is taken over a solid angle of 2π. The derivation of Eq. (4) is given in Supplementary Information. As shown in Fig. 4b

is almost independent of hv. Based on this result it is reasonable to assume that in the [011] configuration the γ value does not depend on hv even though

is almost independent of hv. Based on this result it is reasonable to assume that in the [011] configuration the γ value does not depend on hv even though  and σph are strongly dependent on hv.

and σph are strongly dependent on hv.

The carrier dynamics under steady-state conditions can be interpreted in terms of electrochemical potential31. We first discuss the effective electric field  arising from the DW-PV effect using the electrochemical potential gradient. Noting that

arising from the DW-PV effect using the electrochemical potential gradient. Noting that  V/cm is averaged over the entire samples with the 90° domain structure (W~ 15 μm), we can regard the net photovoltage per DW

V/cm is averaged over the entire samples with the 90° domain structure (W~ 15 μm), we can regard the net photovoltage per DW  as ~37.5 mV. The 90° DW region indeed has a significant volume with a wDW of 2–100 nm25,26,27,28,29,30. Adopting wDW ~ 10 nm as a representative value, we estimate the corresponding effective electric field in the DW region,

as ~37.5 mV. The 90° DW region indeed has a significant volume with a wDW of 2–100 nm25,26,27,28,29,30. Adopting wDW ~ 10 nm as a representative value, we estimate the corresponding effective electric field in the DW region,  , to be ~37.5 kV/cm. This field strength is quite large, i.e., 8000–8500 times as large as that inside the domains

, to be ~37.5 kV/cm. This field strength is quite large, i.e., 8000–8500 times as large as that inside the domains  V/cm).

V/cm).

One of the key factors affecting  in the 90° DW region is electrostatic potential step

in the 90° DW region is electrostatic potential step  20. A rotation of the Ps vector in the 90° DW region is accompanied by

20. A rotation of the Ps vector in the 90° DW region is accompanied by  22. The variation in Ps normal to the DW results in an electric double layer, yielding

22. The variation in Ps normal to the DW results in an electric double layer, yielding  at each of the DW. Another factor affecting

at each of the DW. Another factor affecting  is a local PV component peculiar to the 90° DW region. The DW region has the non-centrosymmetric nature, i.e., a ferroelectric polarization to a considerable degree. The substantial strain in the 90° DW region with

is a local PV component peculiar to the 90° DW region. The DW region has the non-centrosymmetric nature, i.e., a ferroelectric polarization to a considerable degree. The substantial strain in the 90° DW region with  forces us to consider a local PV component, which appears to be greatly different from those inside the domain, i.e., from the bulk PV tensor. In fact, the large dependence of

forces us to consider a local PV component, which appears to be greatly different from those inside the domain, i.e., from the bulk PV tensor. In fact, the large dependence of  on the light-polarization shown in Fig. 3b (corresponding to βDW1) is not predicted by

on the light-polarization shown in Fig. 3b (corresponding to βDW1) is not predicted by  . Furthermore, the experimental fact of the large βDW0 value with an oscillation due to βDW1 validates the local PV component of the 90° DW region, which is clearly distinct from the bulk PV effect. Therefore, we take into account the following two factors affecting

. Furthermore, the experimental fact of the large βDW0 value with an oscillation due to βDW1 validates the local PV component of the 90° DW region, which is clearly distinct from the bulk PV effect. Therefore, we take into account the following two factors affecting  in the 90° DW region:

in the 90° DW region:  and the local PV component.

and the local PV component.

First we assessed the effect of  on

on  . According to the first-principles calculations20,

. According to the first-principles calculations20,  is estimated to be ~230 mV in the 90° DW in the tetragonal BT system. Under light irradiation,

is estimated to be ~230 mV in the 90° DW in the tetragonal BT system. Under light irradiation,  is partially screened by the photogenerated carriers. A detailed study including the screening of

is partially screened by the photogenerated carriers. A detailed study including the screening of  has been performed for BFO films based on a drift diffusion analysis14. We estimate the electrostatic potential step involving the screening effect, i.e., the screened electrostatic potential step

has been performed for BFO films based on a drift diffusion analysis14. We estimate the electrostatic potential step involving the screening effect, i.e., the screened electrostatic potential step  to be ~50 mV at least, which is still larger than the experimental value of

to be ~50 mV at least, which is still larger than the experimental value of  mV. Our estimation focusing on the carrier-density dependence of chemical potential is given in Supplementary Information.

mV. Our estimation focusing on the carrier-density dependence of chemical potential is given in Supplementary Information.

Next we investigated the effect of the local PV component on  . As described above, the non-centrosymmetric structure in the 90° DW region does produce the local PV component, which is superimposed on

. As described above, the non-centrosymmetric structure in the 90° DW region does produce the local PV component, which is superimposed on  . Assuming wDW ~ 10 nm, we estimate the effective electric field originating from the local PV component in the 90° DW region to be

. Assuming wDW ~ 10 nm, we estimate the effective electric field originating from the local PV component in the 90° DW region to be  kV/cm.

kV/cm.

We point out that the local PV component in the DW region can also explain the anomalous PV properties reported for BFO films. In the original report, Yang et al. have observed that VOC increases in proportion to the number of the 71° DWs between electrodes13. They have proposed a model in which  is the origin of the PV properties, together with the fact that a VOC evaluated for each DW of ~10 mV is quite close to a potential step

is the origin of the PV properties, together with the fact that a VOC evaluated for each DW of ~10 mV is quite close to a potential step  across the 71° DW of 20 mV14,21. In contrast, Bhatnagar et al. have observed that VOC markedly increases at low temperatures and that JSC depends on the light-polarization, both of which cannot be explained only by

across the 71° DW of 20 mV14,21. In contrast, Bhatnagar et al. have observed that VOC markedly increases at low temperatures and that JSC depends on the light-polarization, both of which cannot be explained only by  . The behaviour of VOC and JSC is due not to

. The behaviour of VOC and JSC is due not to  but to the bulk PV effect, and the bulk PV tensor was evaluated from the sinusoidal components in

but to the bulk PV effect, and the bulk PV tensor was evaluated from the sinusoidal components in  15. The data observed in

15. The data observed in  contain not only the sinusoidal component but also an apparently significant constant term. In their analysis, this constant term is thought to be caused by the combined effect of the experimental misalignments and is not taken into consideration. We infer that the DW-PV effect also contributes to the observed

contain not only the sinusoidal component but also an apparently significant constant term. In their analysis, this constant term is thought to be caused by the combined effect of the experimental misalignments and is not taken into consideration. We infer that the DW-PV effect also contributes to the observed  behaviour. The DW-PV effect involving

behaviour. The DW-PV effect involving  and the local PV component provides a reasonable explanation for the PV data reported for the BFO films, which are associated with both the number of DWs on the one hand13 and the bulk PV nature (the strong light-polarization dependence) on the other15.

and the local PV component provides a reasonable explanation for the PV data reported for the BFO films, which are associated with both the number of DWs on the one hand13 and the bulk PV nature (the strong light-polarization dependence) on the other15.

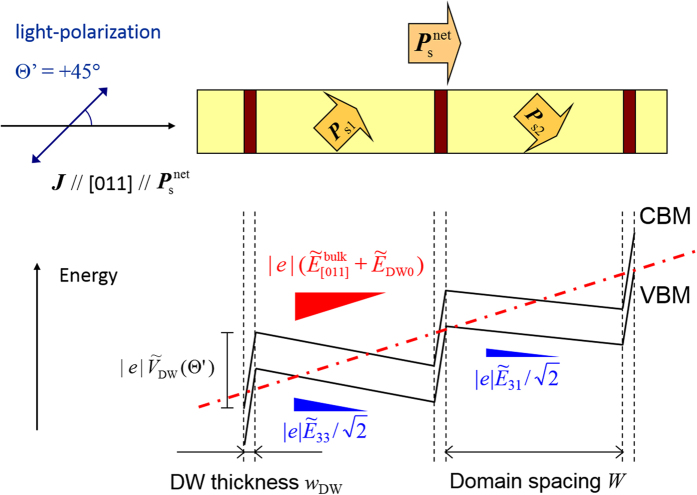

Finally, we discuss why the DW-PV effect delivers a large positive photocurrent going beyond the negative bulk PV effect, i.e.,  . Figure 5 depicts the schematic diagram of valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) under the open-circuit condition. The bulk PV and the DW-PV effects are incorporated as the effective electric fields. Although electronic band structures are modulated by the strain in the 90° DW regions, the modulation is assumed to be ~20% at most, as has been reported for 71° DW in BFO. Since the band modulation caused by the strain is much smaller than the influences of

. Figure 5 depicts the schematic diagram of valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) under the open-circuit condition. The bulk PV and the DW-PV effects are incorporated as the effective electric fields. Although electronic band structures are modulated by the strain in the 90° DW regions, the modulation is assumed to be ~20% at most, as has been reported for 71° DW in BFO. Since the band modulation caused by the strain is much smaller than the influences of  and the local PV component, we represent the CBM and the VBM as the two parallel segments. Given a light-polarization angle

and the local PV component, we represent the CBM and the VBM as the two parallel segments. Given a light-polarization angle  of +45°, the effective electric fields inside the domains are described as

of +45°, the effective electric fields inside the domains are described as  and

and  , where

, where  and

and  denotes those ascribed to β31 and β33, respectively. The electric field in each domain varies with the light-polarization angle

denotes those ascribed to β31 and β33, respectively. The electric field in each domain varies with the light-polarization angle  while the averaged field

while the averaged field  V/cm is independent of

V/cm is independent of  . As described above, the effective electric field in the 90° DWs region

. As described above, the effective electric field in the 90° DWs region  V/cm) and the DW spacing (W ~ 15 μm) lead to the net photovoltage per DW

V/cm) and the DW spacing (W ~ 15 μm) lead to the net photovoltage per DW  of ~37.5 mV, which is the sum of the

of ~37.5 mV, which is the sum of the  value and the local PV component. Noting that the magnitude of

value and the local PV component. Noting that the magnitude of  (positive) is larger than that of

(positive) is larger than that of  (negative), we estimate the net PV field in the [011] direction,

(negative), we estimate the net PV field in the [011] direction,  , to be ~+ 20.5 V/cm (the red dashed-dotted line in Fig. 5). Since the positive field arising from the DW-PV effect overcomes the negative field due to the bulk PV effect, the short-circuit current is reversed by the introduction of the 90° DWs.

, to be ~+ 20.5 V/cm (the red dashed-dotted line in Fig. 5). Since the positive field arising from the DW-PV effect overcomes the negative field due to the bulk PV effect, the short-circuit current is reversed by the introduction of the 90° DWs.

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) taking the bulk PV and DW-PV effects into account under the open-circuit condition.

The light-polarization angle  is fixed to +45°. The slopes inside the two types of alternate-stacking domains correspond to the effective electric fields,

is fixed to +45°. The slopes inside the two types of alternate-stacking domains correspond to the effective electric fields,  and

and  . The effective electric field of the DW-PV effect

. The effective electric field of the DW-PV effect  has a larger magnitude with the opposite sign than that of (averaged) bulk PV effect

has a larger magnitude with the opposite sign than that of (averaged) bulk PV effect  . The direction of the short-circuit photocurrent is reversed by introducing the 90° domain structure.

. The direction of the short-circuit photocurrent is reversed by introducing the 90° domain structure.

We emphasize that the DW-PV effect can be assessed by examining the PV properties based on the precise estimation of the bulk PV tensor. Our report on the giant DW-PV effect opens a reliable route for enhancing the PV properties in ferroelectrics based on the engineering of domain structure in either bulk or thin-film form.

Method

Sample preparation

The samples were prepared from commercial BT single crystals (Neotron) and a Mn(0.25%)-doped BT bulk single crystal grown by a top-seeded solution growth method in our group. The image of the Mn-BT crystal is given in Supplementary Information. After cutting the crystals, we polished the top and bottom sides of the samples [the (100) and  surfaces] and annealed them in air at 1250 °C for 12 h for recovery from mechanical damage incurred during the sample preparation. Electrodes were fabricated on the lateral sides by platinum sputtering. The poling was performed at an applied electric field of 2 kV/cm during a slow cooling from 150 °C down to room temperature through the Curie temperature (TC ~ 130 °C).

surfaces] and annealed them in air at 1250 °C for 12 h for recovery from mechanical damage incurred during the sample preparation. Electrodes were fabricated on the lateral sides by platinum sputtering. The poling was performed at an applied electric field of 2 kV/cm during a slow cooling from 150 °C down to room temperature through the Curie temperature (TC ~ 130 °C).

Electrode configurations

Figure 1 depicts the electrode configurations that we conducted the PV measurements. In all configurations, visible light was irradiated along the  direction, which is perpendicular to the top surface. In the J//[001] configuration (Fig. 1a) the electrodes on the (001) and

direction, which is perpendicular to the top surface. In the J//[001] configuration (Fig. 1a) the electrodes on the (001) and  surfaces were used for the poling and the PV measurements. The photocurrent was measured along the [001] direction in the single-domain samples. In the J//[010] configuration (Fig. 1b) the poling was performed along the [001] direction while the photocurrent was measured along the [010] direction. In the J//[011] configuration (Fig. 1c) the electrodes on the (011) and

surfaces were used for the poling and the PV measurements. The photocurrent was measured along the [001] direction in the single-domain samples. In the J//[010] configuration (Fig. 1b) the poling was performed along the [001] direction while the photocurrent was measured along the [010] direction. In the J//[011] configuration (Fig. 1c) the electrodes on the (011) and  surfaces were used for the poling and the PV measurements. The poling yielded a 90° domain structure where two kinds of spontaneous polarizations (Ps1 and Ps2) with different orientations are present. Using optical microscopy and piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM), we confirmed that the spacing between the 90° DWs was ~15 μm for both the Mn-BT and BT samples. The typical PFM image of the domain structure is given in Supplementary Information. The photocurrent was measured along the direction of the net spontaneous polarization

surfaces were used for the poling and the PV measurements. The poling yielded a 90° domain structure where two kinds of spontaneous polarizations (Ps1 and Ps2) with different orientations are present. Using optical microscopy and piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM), we confirmed that the spacing between the 90° DWs was ~15 μm for both the Mn-BT and BT samples. The typical PFM image of the domain structure is given in Supplementary Information. The photocurrent was measured along the direction of the net spontaneous polarization  , i.e., the [011] direction.

, i.e., the [011] direction.

PV measurements

The PV properties were measured at 25 °C. We denote photocurrent density vector by J and bias voltage by Vbias. We measured the current - voltage characteristics under visible light irradiation with an intensity of 0.03–3 W/cm2 using three monochromatic laser modules [wavelength (photon energy hv); 405 nm (3.11 eV), 515 nm (2.45 eV) and 639 nm (1.97 eV)]. In the measurement of the PV properties, we excluded a transient current due to the capacitance and resistance of the samples. We also confirmed that currents arising from both the pyroelectric and piezoelectric effect are eliminated thoroughly under the measurement conditions in the steady state.

As indicated by the arrows in Fig. 1, the positive direction of J and Vbias is defined as that of the net spontaneous polarization, Ps (Fig. 1a,b) or  (Fig. 1c). In Fig. 2a,b the measured current density (J) is plotted as a function of Vbias. We define short-circuit current density (JSC) as the J value at Vbias = 0 and open-circuit voltage (VOC) as the Vbias value at J = 0. In determining VOC we extrapolated the linear J - Vbias characteristics in a limited range owing to the current amplifier used in our study. It is noteworthy that the positive/negative of VOC means the opposite/same direction of the photovoltage generated inside the samples, because the open-circuit condition is achieved when Vbias cancels VOC under light irradiation.

(Fig. 1c). In Fig. 2a,b the measured current density (J) is plotted as a function of Vbias. We define short-circuit current density (JSC) as the J value at Vbias = 0 and open-circuit voltage (VOC) as the Vbias value at J = 0. In determining VOC we extrapolated the linear J - Vbias characteristics in a limited range owing to the current amplifier used in our study. It is noteworthy that the positive/negative of VOC means the opposite/same direction of the photovoltage generated inside the samples, because the open-circuit condition is achieved when Vbias cancels VOC under light irradiation.

We define light intensity  as the light power per unit area and denote open-circuit electric field (EOC) by the open-circuit voltage (VOC) divided by the electrode spacing. The light polarization was controlled by a half-wavelength plate and a polarizer. We represent the light-polarization (Θ or

as the light power per unit area and denote open-circuit electric field (EOC) by the open-circuit voltage (VOC) divided by the electrode spacing. The light polarization was controlled by a half-wavelength plate and a polarizer. We represent the light-polarization (Θ or  as the angle between the polarization plane of light and the measured direction of J, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

as the angle between the polarization plane of light and the measured direction of J, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

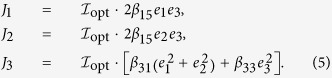

Tensor representation of the bulk PV effect

We describe the tensor representation of J arising from the bulk PV effect in the BT system. The tetragonal phase of BT with 4 mm point group symmetry has the bulk PV tensor with three independent non-zero components under the irradiation of linearly polarized light. We define the incident direction of light (//  ) as i = 1 and the polar axis (//[001]) as i = 3. Using the polarization unit vector [e = (e1, e2, e3)], the three non-zero components of the bulk PV tensor (β31, β33 and β15) and

) as i = 1 and the polar axis (//[001]) as i = 3. Using the polarization unit vector [e = (e1, e2, e3)], the three non-zero components of the bulk PV tensor (β31, β33 and β15) and  , the photocurrent density vector [J = (J1, J2, J3)] can be written as follows:

, the photocurrent density vector [J = (J1, J2, J3)] can be written as follows:

|

Taking into account that the bulk PV tensor (βijk) is a third-rank tensor and is symmetric for the latter two indices (j and k), we adopt here the standard 3 × 6 matrix notation:  with

with  , as used in the representation of the piezoelectric tensor.

, as used in the representation of the piezoelectric tensor.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Inoue, R. et al. Giant photovoltaic effect of ferroelectric domain walls in perovskite single crystals. Sci. Rep. 5, 14741; doi: 10.1038/srep14741 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is partly granted by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers (NEXT Program), initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy (CSTP).

Footnotes

Author Contributions R. Inoue and Y.N. conceived and designed the experiments. S.I. and R. Imura contributed material, and Y.K. and T.O. carried out PFM investigations. R. Inoue performed the experiments and the analysis. R. Inoue, Y.N. and M.M. co-wrote the paper.

References

- Chynoweth A. G. Surface space-charge layers in barium titanate. Phys. Rev. 102, 705–714 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- Koch W. T. H., Munser R., Ruppel W. & Würfel P. Bulk photovoltaic effect in BaTiO3. Solid State Commun. 17, 847–850 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- Koch W. T. H., Munser R., Ruppel W. & Würfel P. Anomalous photovoltage in BaTiO3. Ferroelectrics 13, 305–307 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. S. Optically induced change of refractive indices in LiNbO 3 and LiTaO3. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 3389–3396 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Perterson G. E., Glass A. M. & Negran T. J. Control of the susceptibility of lithium niobate to laser-induced refcactive index changes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 19, 130–132 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Glass A. M., von der Linde D. & Negran T. J. Highvoltage bulk photovoltaic effect and the photorefractive process in LiNbO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 25, 233–235 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Krumins A. E. & Günter P. Photogalvanic effect and photoconductivity in reduced potassium niobate crystals. Phys. Stat. Sol. A 55, K185–K189 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Krätzig E. & Orlowski R. LiTaO3 as holographic storage material. Appl. Phys. 15, 133–139 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Astafiev S. B., Fridkin V. M. & Lazarev V. G. The influence of the magnetic field on the linear bulk photovoltaic current in piezoelectric semiconductor GaP. Ferroelectrics 80, 251–254 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Fridkin V. M. et al. The experimental investigation of the photovoltaic effect in some crystals without a center of symmetry. Appl. Phys. 25, 77–80 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Sasabe H., Nakayama T., Kumazawa K., Miyata S. & Fukada E. Photovoltaic effect in Poly (vinylidene fluoride). Polymer J 13, 967–973 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R. et al. Photocurrent characteristics of Mn-doped barium titanate ferroelectric single crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 09KF03 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. Y. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 143–147 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel J. et al. Efficient photovoltaic current generation at ferroelectric domain walls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 126805 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A. et al. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 2835 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Young S. M. & Rappe A. M. First principle calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirmer O. F., Imlau M. & Merschjann C. Bulk photovoltaic effect of LiNbO3:Fe and its small-polaron-based microscopic interpretation. Phys. Rev. B 83, 165106 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sturman B. I. & Fridkin V. M. The Photovoltaic and Photorefractive Effects in Noncentrosymmetric Materials (Gordon and Breach Science, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B. & Vanderbilt D. ab initio study of ferroelectric domain walls in PbTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 65, 104111 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. & Goddard W. A. III Charge and polarization distributions at the 90° domain wall in barium titanate ferroelectric. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 182903 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Lubk A., Gemming S. & Spaldin N. A. First-principles study of ferroelectric domain walls in multiferroic bismurh ferrite. Phys. Rev. B 80, 104110 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hlinka J., Márton P. Phenomenological model of a 90° domain wall in BaTiO3-type ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 74, 104104 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Catalan G., Seidel J., Ramesh R. & Scott J. F. Domain wall nanoelectronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 119–156 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pramanick A., Prewitt A. D., Forrester J. S. & Jones J. L. Domains, domain walls and defects in perovskite ferroelectric oxides: a review of present understanding and recent contributions. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 37, 243–275 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Little E. A. Dynamic behavior of domain walls in barium titanate. Phys. Rev. 98, 978–984 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. & Honjo G. Electron optical studies of barium titanate single crystal films. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 19, 954–970 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M. D. & Bradt R. C. Thickness of 90° ferroelectric domain walls in (Ba,Pb)TiO3 single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 45, 1931–1933 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F., Khiznichenko V. & Cowley J. M. High-resolution electromicroscopy of 90° ferroelectric domain boundaries in BaTiO3 and Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3. Ultramicroscopy 45, 55–63 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Hashimoto T. & Joy D. C. Electron holographyc study of ferroelectric domain walls. Appl. Phys. Lett. 60, 784–786 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Floquet N. & Valot C. Ferroelectric domain walls in BaTiO 3: structural wall model interpreting fingerprints in XRPD daiagrams. Ferroelectrics 234, 107–122 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Würfel P. Physics of Solar Cells (Willey, Weinheim, 2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.