Abstract

Cancer biomarker discovery constitutes a frontier in cancer research. In recent years, cell-binding aptamers have become useful molecular probes for biomarker discovery. However, there are few successful examples, and the critical barrier resides in the identification of the cell-surface protein targets for the aptamers, where only a limited number of aptamer targets have been identified so far. Herein, we developed a universal SILAC-based quantitative proteomic method for target discovery of cell-binding aptamers. The method allowed for distinguishing specific aptamer-binding proteins from nonspecific proteins based on abundance ratios of proteins bound to aptamer-carrying bait and control bait. In addition, we employed fluorescently labeled aptamers for monitoring and optimizing the binding conditions. We were able to identify and validate selectin L and integrin α4 as the protein targets for two previously reported aptamers, Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e, respectively. This strategy should be generally applicable for the discovery of protein targets for other cell-binding aptamers, which will promote the applications of these aptamers.

Cancer is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with ∼14 million new cases and 8.2 million cancer-related deaths in 2012, and the number of new cases is expected to rise by ∼ 70% over the next two decades (1). Individual tumors may have distinct molecular profiles emanating from genetic and epigenetic alterations along with the activation of complex signaling networks (2). The use of reliable cancer biomarkers for early detection, staging, and individualized therapy may improve patient care. Along this line, Anderson et al. (3) predicted the need of biomarker panels for the detection of multiple proteins for a complex disease like cancer. Nevertheless, the elucidation of molecular alterations of cancer cells is limited by the lack of effective probes that can identify and recognize the protein biomarkers for cancer cells.

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules evolved from random oligonucleotide libraries by repetitive binding of the oligonucleotides to target molecules, a process known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX)1 (4, 5). Similar to antibodies, aptamers can bind to their target molecules with high affinity and specificity (4, 5). Additionally, a large number of aptamers exhibiting specific binding toward a variety of cells has been identified by employing cell-based SELEX (6). These aptamers can recognize the molecular signatures of certain types of cancer cells; thus, cell-surface protein targets of aptamers may serve as candidate biomarkers for these cells.

Identification of the molecular targets of the cancer-cell-specific aptamers is a crucial step toward the revelation of the molecular signatures of cancer cells and the applications of the aptamers. Although recent studies have led to the selection of more than 100 cell aptamers, protein targets for only a very limited number of these aptamers have been identified (7), which greatly hampered their applications. In this vein, aptamer-target protein binding requires a native conformation of the aptamer. On the other hand, membrane proteins are hydrophobic, poorly soluble in water, and of relatively low abundance. Thus, the identification of target protein(s) for aptamers is a challenging task. Through extraction and affinity purification of proteins of cancer cells with the use of cell-recognition aptamers, protein tyrosine kinase 7 and Siglec-5 were identified as protein targets for aptamers that can bind to T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (8) and acute myelogenous leukemia cells (9), respectively. In addition, an aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery method was developed for the identification of biomarkers of immature and mature dendritic cells (10). However, it remains difficult to identify biomarkers of low abundance. By employing cross-linking with the use of an aptamer harboring a photochemically activatable nucleoside, Mallikaratchy et al. (11) identified membrane-bound immunoglobin heavy mu chain as the cell-surface protein target for aptamer TD05. However, chemical modification of an aptamer may alter its binding property, and the method is labor-intensive, rendering it impractical for large-scale discovery of aptamer targets. Recently, the same group employed a formaldehyde-induced cross-linking method and identified stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 as a potential ovarian cancer biomarker (12); many proteins were identified by mass spectrometry, rendering it very difficult to ascertain which protein is the true aptamer target.

Recently, rapid advances have been made for the identification and quantifications of proteins by mass spectrometry. Among the many quantitative proteomic methods, stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) is simple, efficient, and accurate, and it is also suitable for the quantitative analysis of membrane proteins (13, 14). In the present study, we set out to develop a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic approach to identify cell-surface target proteins of two previously reported cell aptamers, Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e (6, 15), and we were able to identify unique cell-surface proteins that can bind to the two aptamers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Heavy lysine ([13C6, 15N2]-l-lysine) and arginine ([13C6]-l-arginine), 99% in isotopic purity and 98% in chemical purity, were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All reagents unless otherwise noted were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse IgG1 K isotype control (Clone: P3.6.2.8.1), anti-human CD62L (selectin L, Clone DREG56), anti-human CD49d (integrin α4, Clone 9F10), and anti-human CD29 (integrin β1) antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Anti-integrin α4 (ab81280) antibody was purchased from Abcam and used for Western blot analysis.

Cell Culture

Jurkat 6E-1 (TIB-152, human acute T cell leukemia) was a gift from Dr. Yi Zheng (Cincinnati Children's Hospital). K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells and the isogenic cells stably expressing α4β1 were kindly provided by Dr. Wassim El Nemer (Institut National de la Transfusion Sanguine) (16).

All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, with medium renewal at every 2–3 days. For SILAC experiments, the RPMI 1640 medium without l-lysine or l-arginine was custom-prepared following the ATCC formulation. The complete light and heavy RPMI 1640 media were prepared by the addition of light or heavy lysine and arginine, together with dialyzed FBS, to the above lysine, arginine-depleted medium. The Jurkat E6–1 cells were cultured in heavy RPMI 1640 medium for at least six cell doublings to achieve complete isotope incorporation.

Oligodeoxynucleotide Probes

Aptamer Sgc-3b (5′-biotin-TTTACTTATTCAATTCCCGTGGGAAGGCTATAGAGGGGCCAGTCTATGAATAAGTTT-FAM-3′); Sgc-4e (5′-biotin-TTTATCACTTATTCAATTCGAGTGCGGATGCAAACGCCAGACAGGGGGACAGGAGATAAGTGATTT-FAM-3′); L45 (5′-biotin-TTT(N)45TTT-FAM-3′, where ‘N′ represents an equimolar mixture of A, T, G, or C) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) and purified by HPLC.

Sample Preparation and Tryptic Digestion

Aptamers were dissolved in the binding buffer, which contained PBS with 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 0.1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA, and annealed by heating to 95 °C for 5 min and cooled on ice for 15 min. The aptamers were kept at 25 °C for 5 min prior to use. For the binding experiments, the aptamer (Sgc-3b or Sgc-4e, 100 nm) was incubated, on ice with gentle shaking, with 2 × 108 heavy- or light-labeled Jurkat E6–1 cells in a 4-ml binding buffer for 30 min, after which 4 ml of PBS buffer containing 2% formaldehyde were added. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 15 min to induce cross-linking. The reaction was subsequently quenched with a 400-μl solution of 2.5 m glycine. The cells were then washed twice with washing buffer, which contained PBS with 5 mm EDTA. Subsequently, the cells were incubated, at 4 °C for 1 h with shaking, in a lysis buffer containing PBS (pH 7.4), 2% Triton X-100 (v/v), 0.4% SDS (w/v), 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF, and a protease inhibitor mixture. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 8000g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubated with 20 μl high-capacity streptavidin agarose resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) at 4 °C for 1 h. The resin was washed sequentially with lysis buffer, washing buffer, and water twice. In the forward SILAC experiment, the light- and heavy-labeled cells were cross-linked with aptamers Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e, respectively, and the cells were subsequently lysed. The lysates were incubated separately with the resin and subsequently combined. On the other hand, the resins incubated with the lysates of light- and heavy-labeled cells that were cross-linked with aptamers Sgc-4e and Sgc-3b, respectively, were mixed in the reverse SILAC experiment.

The resin was subsequently resuspended in 50 mm NH4HCO3 and incubated at 65 °C overnight to remove nonspecific proteins. To the resultant mixture was added 4× reducing SDS loading buffer (500 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 20% β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mg/ml bromophenol blue), and the suspension was heated at 95 °C for 1 h. The sample was run on 12% SDS-PAGE at 150 V for 15 min to about 9–10 mm and the gel band was cut out. The proteins were digested in-gel with trypsin following published procedures (17). The resulting peptides were collected, dried in a Speed-vac, and stored at −20 °C until LC-MS and MS/MS analyses.

For pulling down endogenously biotinylated proteins, streptavidin beads and biotin-saturated streptavidin beads were employed to pull down heavy and light lysates, respectively, in the forward SILAC experiment. In the reverse SILAC experiment, streptavidin beads and biotin-saturated streptavidin beads were utilized to pull down light and heavy lysates, respectively. Other experimental procedures were the same as the aptamer pull-down experiment.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

LC-MS and MS/MS experiments were performed on an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Samples were automatically loaded from a 48-well microplate autosampler using an EASY-nLC II system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 3 μl/min onto a homemade trapping column (150 μm*60 mm) packed with 5 μm C18 120 Å reversed-phase material (ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, Dr. Maisch). The peptides were then separated on a 150 μm*200 mm column packed with the same type of material using a 180-min linear gradient of 8–35% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid and at a flow rate of 230 nl/min. The LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent scan mode, where one scan of MS was followed with MS/MS of the top 20 abundant ions found in MS.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

For peptide identification, the raw MS data were processed with the MaxQuant search engine (1.3.0.5) against human International Protein Index (IPI) protein database version 3.68 with 87,062 entries. Common contaminants were added to this database. Initial precursor ion mass tolerance of 20 ppm and fragment ion mass deviation of 0.5 Da were set as the search criteria. The maximum number of miss-cleavages for trypsin was set as two per peptide. Cysteine carbamidomethylation was considered as a fixed modification, and N-terminal acetylation and methionine oxidation were considered as variable modifications. For statistical evaluation of the data obtained, the posterior error probability and false discovery rate were used. The false discovery rate was determined by searching a reverse database. A false discovery rate of 0.01 was required for proteins and peptides. To match identifications across different replicates, the “match between runs” option in MaxQuant was enabled within a time window of 2 min.

For the candidate protein targets for the aptamers, two or more unique peptides had to be identified and the posterior error probability had to be lower than 10−5. In addition, the protein had to be identified in both forward and reverse SILAC labeling experiments, and the product of the paired forward and reverse “H/L ratio” had to be between 0.5 the 2.0. The intensity ratios for light/heavy-labeled peptides of the candidate aptamer targets were further validated by manual analysis, where the intensity ratios were taken across the peaks found in the selected-ion chromatograms for precursor ions of the unique peptides derived from the candidate aptamer targets. Protein ratios were calculated as the mean values for the observed ratios of the comprising peptides. For the aptamer target identification experiment, we normalized the protein ratios against the average ratio observed for endogenously biotinylated proteins, including pyruvate carboxylase, isoform 4 of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, propionyl-coenzyme A carboxylase, and methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase subunit α to correct for potential incomplete SILAC labeling and/or inequality in loading of light and heavy lysates to the aptamer-immobilized streptavidin beads. Ratio data are calculated as mean ± S.D. using Origin 8.0 Software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA) according to two forward and reverse SILAC labeling experiments (n = 4).

Flow Cytometry

A total of 5 × 105 cells were incubated with PE-labeled anti-CD62L, anti-CD49d, anti-CD29, and/or 100 nm FITC-labeled aptamers of Sgc-3b or Sgc-4e in a 200-μl binding buffer (PBS containing 5 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2) on ice for 30 min. The cells were washed once, resuspended in 0.4 ml of the above-mentioned binding buffer, and subjected to flow cytometry analysis on a BD FACSAria I or FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences); 10,000 events were measured for each cell sample. The FITC-labeled, unenriched ssDNA library and PE-labeled IgG were employed as negative controls.

For antibody competition experiments, 5 × 105 cells were incubated on ice with 100 nm aptamer in the binding buffer for 20 min; antibody was subsequently added and incubated for 30 min. After washing, the cell suspension was subjected to flow cytometry analysis. For aptamer competition experiments, 5 × 105 cells were incubated with antibody in binding buffer on ice for 20 min; aptamer was then added until its final concentration reached 100 nm or 1,000 nm. After a 30-min incubation and washing, the cells were again analyzed by flow cytometry.

siRNA Transfection

siRNA transfection was carried out by nucleofection of SMARTpool: ON-TARGETplus SELL siRNA, which was comprised of four different sequences of siRNAs targeting the mRNA of the gene encoding selectin L, or nontargeting control siRNA (d-001210, GE Dharmacon) using Amaxa® Cell Line Nucleofector® Kit V and X-001 program provided by the manufacturer (Amaxa, Lonza). Aptamer or antibody binding was examined at 72 h post siRNA treatment.

Western Blotting

The proteins were pulled down following the aforementioned procedures and electrophoresed on Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gel (Bio-Rad). The proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane by Trans-Blot Turbo System (Bio-Rad) and blocked with PBS-T (PBS with 0.1% Tween) containing 5% skim milk at 4 °C for 6 h. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight and then with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The HRP signals were detected using Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo).

RESULTS

Optimization and Monitoring of the Experimental Procedures

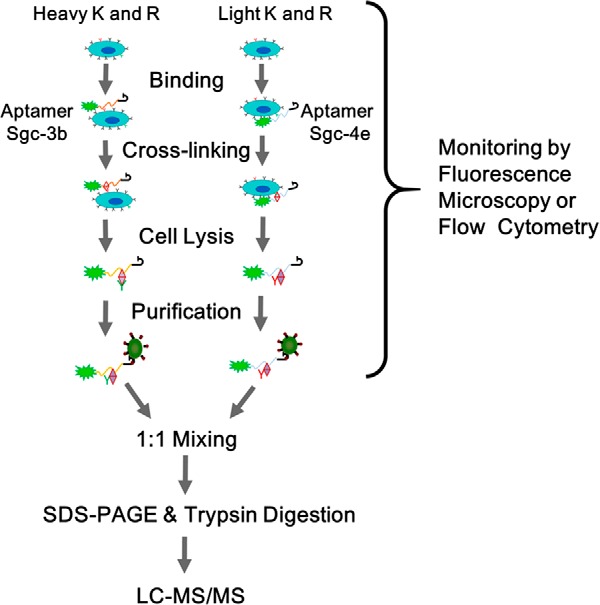

We set out to develop a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic method to identify cell-surface protein targets of two previously selected cell aptamers (Fig. 1, see also Experimental Section). Aptamer Sgc-3b displays selective binding toward T-lineage leukemia cells (e.g. Molt-4, Sup-T1, or Jurkat E6–1) (6) and nearly no binding toward normal hematopoietic cells or lymphoma and myeloma cells, whereas aptamer Sgc-4e can bind to several types of cancer cells (15) (Table S1). Because there are multiple steps involved in aptamer target identification, including protein pull-down, separation, and identification, and the protein targets for aptamer are not known until the last step, we employed 3′-fluorescently labeled aptamers for monitoring the aptamer-cell binding so as to optimize the experimental conditions. We found that the binding of Sgc-4e to Jurkat E6–1 cells depends on the presence of divalent metal ions (Figs. S1A and S1B); Sgc-4e cannot bind to the Jurkat E6–1 cells in the absence of Mg2+ or Ca2+, under which conditions the binding of Sgc-3b to the cells is not affected. We also optimized carefully the cross-linking time and found that a 15-min cross-linking led to substantial binding of the aptamer to the cell surface without introducing appreciable nonspecific binding (Fig. S1C). Thus, we chose to include Mg2+ (5 mm) and Ca2+ (1 mm) ions in the binding buffer and employed a 15-min cross-linking for the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

The strategy for the identification of protein targets of cancer cell aptamers using a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic method. Shown is the workflow for forward SILAC labeling experiment.

Surfactants are routinely employed to isolate proteins from cells and tissues. We found that the Sgc-3b-target complex could be isolated using a mild lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 (Fig. S2A). The same lysis buffer, however, did not allow for the isolation of the Sgc-4e-target complex from the cells (Fig. S2B). Thus, we employed a lysis buffer containing 0.4% SDS and 2% Triton X-100, under which conditions, the streptavidin-coated beads facilitated the pull-down of the target complexes for both aptamers, as illustrated by fluorescence microscopy results (Fig. S3).

In the conventional protein pull-down method (8, 12), proteins in the pull-down mixture are resolved by SDS-PAGE and individual protein bands on the gel are cut out and digested to peptides with trypsin for LC-MS/MS identification. However, we found that the streptavidin-coated beads can pull down a number of proteins displaying as distinct bands on SDS-PAGE, which can be blocked by biotin (Fig. S4A). Without knowing the molecular weights of the target proteins for the aptamers, it is difficult to determine which bands contain the protein targets (Fig. S4B). Hence, we cut the entire protein band after a very short separation on a 10% SDS-PAGE and digested the proteins in-gel with trypsin prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

To achieve unbiased identification of cell-surface protein targets of the two aptamers, we employed a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic method. To this end, we cultured Jurkat E6–1 cells separately in light and heavy media, where the heavy medium contained the uniformly 15N,13C-labeled lysine and arginine. First, we assessed the capability of streptavidin beads in pulling down endogenously biotinylated proteins, where we incubated streptavidin beads and biotin-saturated streptavidin beads with heavy and light lysates, respectively, in the forward SILAC experiment, or with light and heavy lysates, respectively, in the reverse SILAC experiment. After washing, the beads were combined, the proteins on the beads were digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were subjected to LC-MS and MS/MS analyses. As expected, the LC-MS data led to the identifications of known endogenously biotinylated proteins (18) that were preferentially pulled down by streptavidin beads over the corresponding biotin-saturated streptavidin beads, including pyruvate carboxylase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, propionyl-coenzyme A carboxylase, and methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase (Table S2). Additionally, the identification of endogenously biotinylated proteins was not affected by formaldehyde-mediated cross-linking (Table S2).

Simultaneous Identifications of Targets for Aptamers Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e

We then incubated the light- and heavy-labeled cells with the 5′-biotinylated aptamers Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e, respectively, in the forward SILAC experiment, or with the 5′-biotinylated aptamers Sgc-4e and Sgc-3b, respectively, in the reverse SILAC experiment. The pull-down mixture contained proteins that were cross-linked with the biotinylated aptamers, along with endogenously biotinylated proteins. After tryptic digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis, we were able to identify 71 proteins that can bind to the resins immobilized with the Sgc-3b and/or Sgc-4e aptamer. In this vein, we first determined the heavy/light (H/L) ratios for the aforementioned endogenously biotinylated proteins and normalized the H/L ratio for other quantified proteins against the mean H/L ratio for the endogenously biotinylated proteins to correct for potential incomplete SILAC labeling and/or inequal loading of light and heavy lysates to the streptavidin beads. After removal of those proteins that were only identified in forward or reverse SILAC experiments and those with the product of the paired forward and reverse “H/L ratio” being larger than 2 or smaller than 0.5, we observed 21 proteins exhibiting binding toward the Sgc-3b and/or the Sgc-4e aptamer (Table I).

Table I. A list of proteins that can bind to aptamer Sgc-3b or Sgc-4e identified using the SILAC method.

| Refseq protein accession | Gene symbol | Description | Unique peptides | Sequence coverage (%) | PEPa | Protein abundance ratio (Sgc-3b/Sgc-4e)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific binding proteins toward aptamer Sgc-3b or Sgc-4e | ||||||

| NP_000646 | SELL | Selectin L precursor | 4 | 11.7 | 4.75E-47 | 13.00 ± 3.61 |

| NP_006280 | TLN1 | Talin-1 | 4 | 1.9 | 1.97E-19 | 0.15 ± 0.07 |

| NP_000876 | ITGA4 | Integrin α-4 precursor | 13 | 14.5 | 1.69E-77 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| NP_002202 | ITGB1 | Isoform β-1A of Integrin β-1 | 7 | 10.9 | 9.95E-25 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Endogenously biotinylated proteins | ||||||

| NP_000402 | HLCS | Biotin-protein ligase | 6 | 7.9 | 1.47E-13 | 1.13 ± 0.14 |

| NP_000911 | PC | Pyruvate carboxylase | 42 | 43.5 | 0 | 1.08 ± 0.05 |

| NP_000273 | PCCA | Propionyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase, α polypeptide isoform a precursor | 32 | 48.6 | 0 | 1.04 ± 0.05 |

| NP_071415 | MCCC2 | Isoform 1 of Methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase β chain | 12 | 28.6 | 3.30E-84 | 1.02 ± 0.08 |

| NP_064551 | MCCC1 | Methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase subunit α | 19 | 35.2 | 6.91E-214 | 0.99 ± 0.06 |

| NP_000523 | PCCB | Propionyl coenzyme A carboxylase, β polypeptide, isoform CRA_c | 19 | 43.6 | 0 | 0.97 ± 0.11 |

| NP_942131 | ACACA | Isoform 4 of Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 | 64 | 28.2 | 0 | 0.93 ± 0.07 |

| Proteins with similar binding affinities toward aptamers Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e | ||||||

| NP_001460 | XRCC6 | X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 6 | 33 | 49.3 | 1.34E-251 | 1.58 ± 0.76 |

| NP_066964 | XRCC5 | ATP-dependent DNA helicase 2 | 25 | 34.7 | 2.90E-191 | 1.57 ± 0.81 |

| NP_006089 | GNB2L1 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit β-2-like 1 | 4 | 13.2 | 1.3904E-09 | 1.42 ± 0.52 |

| NP_031381 | HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-β | 5 | 14.8 | 4.14E-66 | 1.15 ± 0.40 |

| NP_003134 | SSBP1 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | 4 | 33.1 | 4.71E-123 | 1.11 ± 0.92 |

| NP_001949 | EEF1A2 | Elongation factor 1-α2 | 3 | 6.3 | 2.03E-11 | 1.11 ± 0.51 |

| NP_006588 | HSPA8 | Isoform 1 of heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 6 | 10.7 | 2.67E-51 | 1.09 ± 0.39 |

| NP_003312 | TUFM | Tu translation elongation factor | 3 | 9.5 | 8.85E-18 | 1.00 ± 0.13 |

| NP_002147 | HSPD1 | 60 kDa heat shock protein | 15 | 29.3 | 1.54E-79 | 0.94 ± 0.08 |

| NP_004125 | HSPA9 | Stress-70 protein | 6 | 9.6 | 4.12E-36 | 0.92 ± 0.16 |

a PEP, the posterior error probability. This value essentially operates as a p value, where smaller is better.

b The data represent the mean and standard deviation of results from independent forward and reverse pull-down experiments.

Validation of CD62L as a Target for Aptamer Sgc-3b

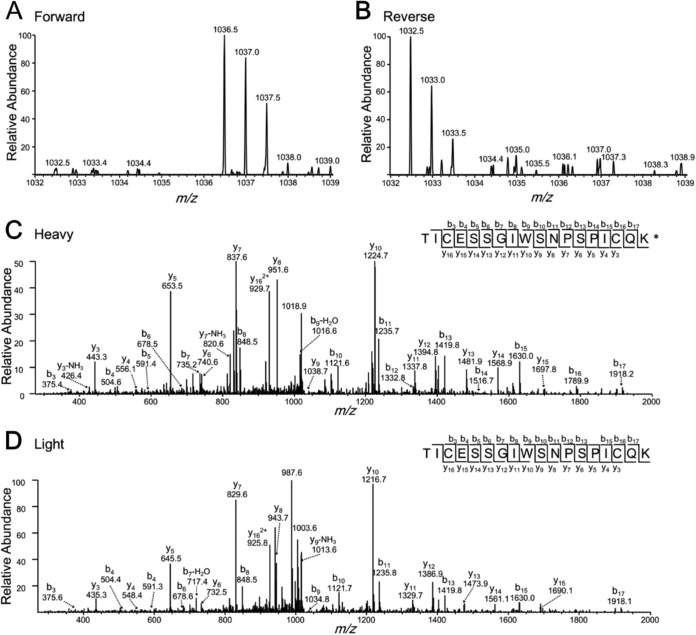

Our results showed that selectin L was the only candidate target protein for the Sgc-3b aptamer, with a pull-down ratio being greater than 10. Figure 2 depicts the ESI-MS and MS/MS results of a representative peptide TICESSGIWSNPSPICQK from selectin L. Selectin L, a.k.a. CD62L, is expressed on leukocyte surface, and it plays an important role in leukocyte adhesion (19). Selectin L can be easily shed from the cell membrane (20), which is in keeping with our observation that the Sgc-3b-target complex can be eluted using a mild lysis buffer.

Fig. 2.

Representative ESI-MS and MS/MS of a tryptic peptide from CD62L (the target protein for aptamer Sgc-3b). The cysteine residue was modified by a carbamidomethyl group. K* designates the heavy lysine. Shown in (A) and (B) are the ESI-MS for the heavy (m/z 1036.5 for the monoisotopic peak of the [M+2H]2+ ion) and the light (m/z 1032.5 for the monoisotopic peak of the [M+2H]2+ ion) lysine-containing peptide observed in forward and reverse SILAC experiments. Displayed in (C) and (D) are the MS/MS for the [M+2H]2+ ions of the heavy- and light-lysine-bearing peptide.

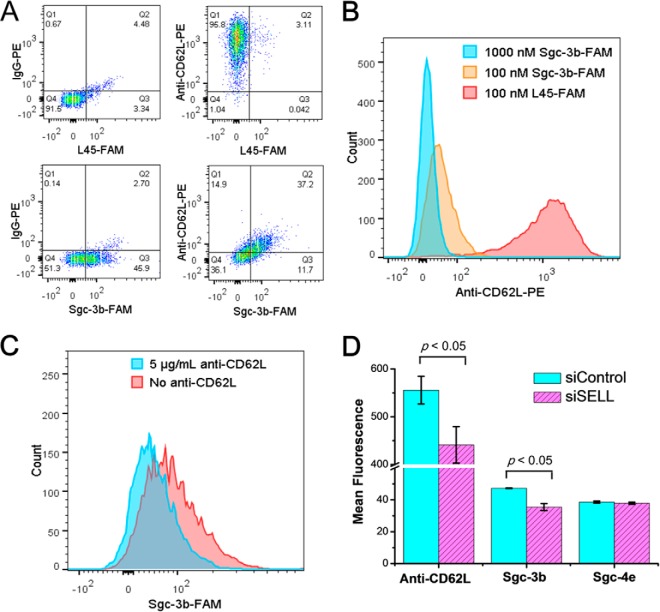

Multiple lines of evidence supports that CD62L is a target for aptamer Sgc-3b. First, we conducted a flow cytometry experiment to examine whether the binding of aptamer Sgc-3b to Jurkat E6–1 cells could be perturbed by anti-CD62L antibody. As expected, flow cytometry results revealed the cell-surface expression of CD62L on Jurkat E6–1 cells with the use of PE-labeled anti-CD62L antibody (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we observed a markedly diminished binding of anti-CD62L-PE to Jurkat E6–1 cells in the presence of excess amount of Sgc-3b (Fig. 3B). Likewise, we found that the addition of anti-CD62L resulted in a reduced binding of Sgc-3b to Jurkat E6–1 cells (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that Sgc-3b and anti-CD62L have overlapping binding sites on the extracellular domain of selectin L. Second, we confirmed the binding of Sgc-3b to selectin L by monitoring the binding of Sgc-3b to Jurkat E6–1 cells after depletion of endogenous selectin L using siRNA. Our results showed that, despite the relatively low knock-down efficiency of selectin L as reflected by a modest decrease in binding toward anti-CD62L (likely attributed to relatively poor transfection efficiency of Jurkat E6–1 cells), the treatment with siRNA against selectin L gave rise to a reduced binding of Sgc-3b compared with those cells treated with control nontargeting siRNAs (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, we found that, as expected, the binding of Sgc-4e with Jurkat E6–1 cells was not altered upon the siRNA-mediated depletion of selectin L (Fig. 3D). Third, our flow cytometry results revealed that those lines of cells displaying no detectable binding toward aptamer Sgc-3b (i.e. K562, HCT-8, LoVo, PC-3, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, MCF-7R, HEK-293, MRC-5, and SK-Hep-1 cells, see Table S1) did not exhibit appreciable expression of CD62L (Fig. S5). Together, the above results support that selectin L is a target for aptamer Sgc-3b.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry for validating CD62L as a target for aptamer Sgc-3b. (A) Flow cytometry assay of Jurkat E6–1 cells stained with Sgc-3b-FAM and anti-CD62L-PE FAM-labeled random DNA (L45-FAM) and IgG-PE, which do not bind to cells, were used as the negative controls. (B) Flow cytometry results to show the competition of different concentrations of Sgc-3b-FAM with 0.625 μg/ml anti-CD62L-PE in binding toward Jurkat E6–1 cells. (C) Flow cytometry results to show the competition of 5 μg/ml anti-CD62L-PE with 100 nm Sgc-3b-FAM in binding toward Jurkat E6–1 cells. (D) Flow cytometry assay results showed that the siRNA-mediated depletion of CD62L in Jurkat E6–1 cells led to a reduced binding of aptamer Sgc-3b, but not aptamer Sgc-4e. Binding toward anti-CD62L, Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e were assessed at 72 h after siRNA treatment, where reduced binding toward anti-CD62L indicated the successful, albeit modest, knock-down of CD62L after siRNA treatment.

Validation of CD49d as a Target for Aptamer Sgc-4e

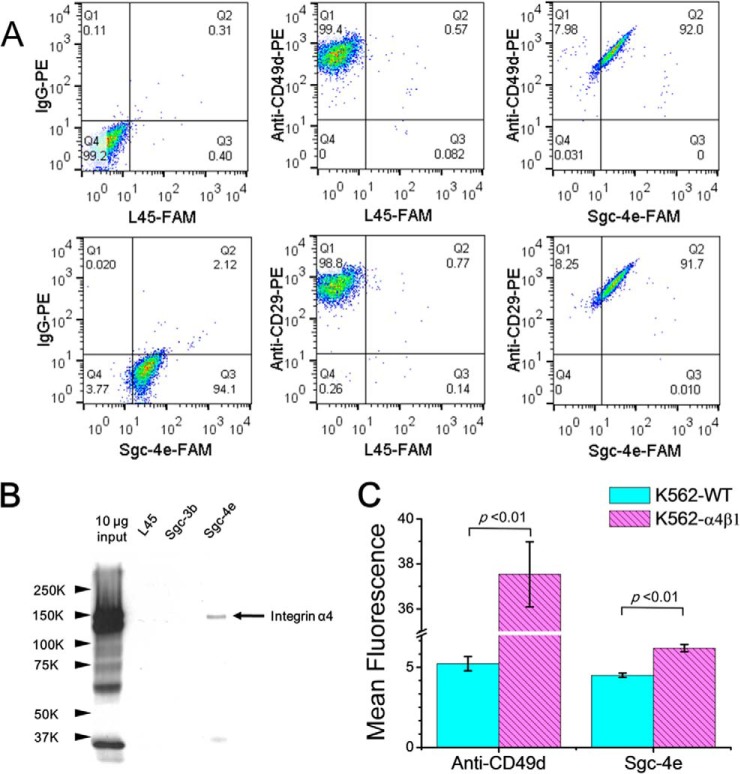

Our LC-MS and MS/MS results also led to the identifications of integrins α4 and β1 (a.k.a. CD49d and CD29, respectively) as well as talin-1 as the candidate protein targets for aptamer Sgc-4e (Table I). The quantification results for representative peptides from integrin α4, integrin β1, and talin-1 are shown in Figs. S6-S8 of the Supporting Information. Integrins α4 and β1 can form a heterodimer and are expressed in leukemic cells and different solid tumors (21). Talin-1 is a cytoskeleton protein that binds to the cytoplasmic tails of integrin β and regulates integrins and focal adhesion signaling (22, 23). Flow cytometry analysis with the use of PE-conjugated anti-CD49d and anti-CD29 antibodies showed that CD49d and CD29 are expressed on the membrane of Jurkat E6–1 cells (Fig. 4A). We also found that Jurkat E6–1 cells can bind simultaneously to aptamer Sgc-4e and anti-CD49d or CD29d. This observation could be attributed to the possibility that Sgc-4e and anti-CD49d or anti-CD29 bind to different sites on the extracellular domain of integrin α4β1.

Fig. 4.

Validation of protein targets of aptamer Sgc-4e. (A) Flow cytometry assay results of Jurkat E6–1 cells stained with Sgc-4e-FAM and anti-CD49d-PE or anti-CD29-PE. FAM-labeled random DNA (L45-FAM) and IgG-PE, which do not bind to cells, were used as negative control. Sgc-4e-FAM and anti-CD49d-PE or anti-CD29-PE can bind simultaneously to Jurkat E6–1 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of proteins that were pulled down by random DNA sequence (L45), control aptamer (Sgc-3b) and aptamer Sgc-4e, respectively. (C) Flow cytometry assay results showed that K562 cells with stable expression of α4β1 display stronger binding to Anti-CD49d or Sgc-4e than wild-type K562 cells.

To further confirm that integrin α4 is a target of Sgc-4e, we performed an aptamer pull-down experiment and monitored the pull-down proteins using Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 4B, we were able to pull down integrin α4 with the use of Sgc-4e but not an oligodeoxynucleotide with random sequence (L45) or aptamer Sgc-3b. Additionally, we monitored the expression levels of CD49d on ten different cell lines by flow cytometry analysis and found that MCF-7R, HEK-293, MRC-5, and SK-Hep-1 cells express moderate level of this protein (Fig. S5). This finding is in line with the observation that, among these ten lines of cells, MCF-7R, HEK-293, MRC-5, and SK-Hep-1 are the only lines exhibiting binding toward aptamer Sgc-4e (Table S1). In this vein, it is worth noting that all ten lines of cells express CD29 (Fig. S5). To examine the binding of Sgc-4e to integrin α4 or β1, we compared the ability of the aptamer in binding toward K562 cells, which express only the endogenous integrin β1 and the isogenic K562 cells stably expressing the α4β1 heterodimer on the cell surface (16). Our results showed that aptamer Sgc-4e binds more strongly to K562 cells stably expressing α4β1 than to the parental K562 cells (Fig. 4C), supporting again that the α4 chain of integrin α4β1 constitutes the target of Sgc-4e.

DISCUSSION

Aptamers, also known as chemical antibodies, have the ability to bind to their targets with high affinity and specificity. Aptamers have several advantages over antibodies, including the ease of chemical synthesis, high chemical stability, low molecular weight, and the ease of modification and manipulation (24). The use of cell-SELEX has led to the generation of many aptamers for targeting live cells (25–31), and these aptamers have been found to be useful for the capture, detection, and imaging of cells, as well as for cancer imaging in vivo. However, practical applications of cancer-cell-specific aptamers are currently hampered by the lack of knowledge about their molecular targets, where only a very limited number of aptamer targets have been identified (7).

In the present study, we developed a general method for identifying the protein targets for aptamers. The aptamer was labeled with a fluorophore, which facilitated the monitoring of the effectiveness of the binding, separation, and purification procedures. In addition, with the use of a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic workflow, we were able to distinguish specific from nonspecific binding. Moreover, we employed endogenously biotinylated proteins as references to correct for the SILAC ratio. In this context, it is worth noting that a panel of several aptamers may be generated from cell-SELEX, which may bind to different protein targets on the cell surface. In the present study, we employed two aptamers, which bind to distinct proteins of target cells, as an example to illustrate that the method could facilitate the simultaneous identifications of cell-surface target proteins of the two aptamers. However, the method can be readily employed for the identification of target proteins of a single aptamer, where a random or scrambled sequence can be used as the control bait. Additionally, although we utilized metabolic labeling with SILAC, the method reported in this study can also be adapted for other quantitative proteomics workflows, including chemical labeling approaches with the use of isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (32) and tandem mass tags (33). The latter labeling methods would be particularly attractive for identification of aptamer targets in tissues or biofluids where metabolic labeling is not easy to implement.

With this method, we identified, for the first time, selectin L (CD62L) and integrin α4 (CD49d) as targets for aptamers Sgc-3b and Sgc-4e, respectively. Selectin L is a biomarker found on naive T cells and further can distinguish central memory from effector memory T cells (20). Burgess et al. (34) found recently that CD62L could be employed as a therapeutic target for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Integrin α4 (CD49d) was an independent prognostic marker in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (35). Natalizumab, the first integrin α4 antagonist, was found in a phase III clinical trial to reduce the risk of sustained progression of disability and decrease the rate of clinical relapse in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (36). Different from antibody, aptamers are not immunogenic (37); thus, aptamer Sgc-4e may potentially be employed for the therapeutic intervention of relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions: T.B., D.S., and Y.W. designed research; T.B. performed the research; D.S. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; T.B. and Y.W. analyzed the data; and T.B., D.S., and Y.W. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by Grant 973 Program (2011CB911000 and 21275149), and the National Science Fund of China (21205124, 21321003, 21375135), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 ES019873). T. Bing was supported in part by the China Scholarship Council.

This article contains supplemental material Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1-S8.

This article contains supplemental material Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1-S8.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- SELEX

- systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

- SILAC

- stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- PE

- R-phycoerythrin

- IgG

- immunoglobulin G

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stewart B., Wild C. P. (2014) World Cancer Report 2014 IARC Nonserial Publication, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mäbert K., Cojoc M., Peitzsch C., Kurth I., Souchelnytskyi S., Dubrovska A. (2014) Cancer biomarker discovery: Current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 90, 659–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson N. L., Polanski M., Pieper R., Gatlin T., Tirumalai R. S., Conrads T. P., Veenstra T. D., Adkins J. N., Pounds J. G., Fagan R. (2004) The human plasma proteome: a nonredundant list developed by combination of four separate sources. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 311–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellington A. D., Szostak J. W. (1990) Invitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tuerk C., Gold L. (1990) Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shangguan D., Li Y., Tang Z., Cao Z. C., Chen H. W., Mallikaratchy P., Sefah K., Yang C. J., Tan W. (2006) Aptamers evolved from live cells as effective molecular probes for cancer study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11838–11843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ye M., Hu J., Peng M., Liu J., Liu J., Liu H., Zhao X., Tan W. (2012) Generating aptamers by cell-SELEX for applications in molecular medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 3341–3353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shangguan D., Cao Z., Meng L., Mallikaratchy P., Sefah K., Wang H., Li Y., Tan W. (2008) Cell-specific aptamer probes for membrane protein elucidation in cancer cells. J. Proteome Res. 7, 2133–2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang M., Jiang G., Li W., Qiu K., Zhang M., Carter C. M., Al-Quran S. Z., Li Y. (2014) Developing aptamer probes for acute myelogenous leukemia detection and surface protein biomarker discovery. J. Hematol. Oncol. 7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berezovski M. V., Lechmann M., Musheev M. U., Mak T. W., Krylov S. N. (2008) Aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery (AptaBiD). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9137–9143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mallikaratchy P., Tang Z., Kwame S., Meng L., Shangguan D., Tan W. (2007) Aptamer directly evolved from live cells recognizes membrane bound immunoglobin heavy mu chain in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 2230–2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Simaeys D., Turek D., Champanhac C., Vaizer J., Sefah K., Zhen J., Sutphen R., Tan W. (2014) Identification of cell membrane protein stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 as a potential ovarian cancer biomarker using aptamers selected by cell systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment. Anal. Chem. 86, 4521–4527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mann M. (2006) Functional and quantitative proteomics using SILAC. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 952–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ong S. E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D. B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M. (2002) Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shangguan D., Cao Z. C., Li Y., Tan W. (2007) Aptamers evolved from cultured cancer cells reveal molecular differences of cancer cells in patient samples. Clin. Chem. 53, 1153–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chaar V., Laurance S., Lapoumeroulie C., Cochet S., De Grandis M., Colin Y., Elion J., Le Van Kim C., El Nemer W. (2014) Hydroxycarbamide decreases sickle reticulocyte adhesion to resting endothelium by inhibiting endothelial lutheran/basal cell adhesion molecule (Lu/BCAM) through phosphodiesterase 4A activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 11512–11521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shevchenko A., Tomas H., Havlis J., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2006) In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protocols 1, 2856–2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chandler C. S., Ballard F. J. (1986) Multiple biotin-containing proteins in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem. J. 237, 123–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raffler N. A., Rivera-Nieves J., Ley K. (2005) L-selectin in inflammation, infection and immunity. Drug Disc. Today Ther. Strateg. 2, 213–220 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang S., Liu F., Wang Q. J., Rosenberg S. A., Morgan R. A. (2011) The shedding of CD62L (L-selectin) regulates the acquisition of lytic activity in human tumor reactive T lymphocytes. PLoS One 6, e22560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schlesinger M., Bendas G. (2015) Contribution of very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) integrin to cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin J. K., Tien P. C., Cheng C. J., Song J. H., Huang C., Lin S. H., Gallick G. E. (2015) Talin1 phosphorylation activates beta1 integrins: A novel mechanism to promote prostate cancer bone metastasis. Oncogene 34, 1811–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calderwood D. A., Zent R., Grant R., Rees D. J., Hynes R. O., Ginsberg M. H. (1999) The Talin head domain binds to integrin beta subunit cytoplasmic tails and regulates integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28071–28074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tan W., Donovan M. J., Jiang J. (2013) Aptamers from cell-based selection for bioanalytical applications. Chem. Rev. 113, 2842–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang Z., Shangguan D., Wang K., Shi H., Sefah K., Mallikratchy P., Chen H. W., Li Y., Tan W. (2007) Selection of aptamers for molecular recognition and characterization of cancer cells. Anal. Chem. 79, 4900–4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen H. W., Medley C. D., Sefah K., Shangguan D., Tang Z., Meng L., Smith J. E., Tan W. (2008) Molecular recognition of small-cell lung cancer cells using aptamers. ChemMedChem 3, 991–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shangguan D., Meng L., Cao Z. C., Xiao Z., Fang X., Li Y., Cardona D., Witek R. P., Liu C., Tan W. (2008) Identification of liver cancer-specific aptamers using whole live cells. Anal. Chem. 80, 721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fang X., Tan W. (2010) Aptamers generated from cell-SELEX for molecular medicine: A chemical biology approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 48–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y., Luo Y., Bing T., Chen Z., Lu M., Zhang N., Shangguan D., Gao X. (2014) DNA aptamer evolved by cell-SELEX for recognition of prostate cancer. PLoS One 9, e100243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li W. M., Bing T., Wei J. Y., Chen Z. Z., Shangguan D. H., Fang J. (2014) Cell-SELEX-based selection of aptamers that recognize distinct targets on metastatic colorectal cancer cells. Biomaterials 35, 6998–7007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sefah K., Bae K. M., Phillips J. A., Siemann D. W., Su Z., McClellan S., Vieweg J., Tan W. (2013) Cell-based selection provides novel molecular probes for cancer stem cells. Int. J. Cancer 132, 2578–2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ross P. L., Huang Y. N., Marchese J. N., Williamson B., Parker K., Hattan S., Khainovski N., Pillai S., Dey S., Daniels S., Purkayastha S., Juhasz P., Martin S., Bartlet-Jones M., He F., Jacobson A., Pappin D. J. (2004) Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 1154–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson A., Schäfer J., Kuhn K., Kienle S., Schwarz J., Schmidt G., Neumann T., Johnstone R., Mohammed A. K., Hamon C. (2003) Tandem mass tags: A novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 75, 1895–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burgess M., Gill D., Singhania R., Cheung C., Chambers L., Renyolds B. A., Smith L., Mollee P., Saunders N., McMillan N. A. (2013) CD62L as a therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 5675–5685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Majid A., Lin T. T., Best G., Fishlock K., Hewamana S., Pratt G., Yallop D., Buggins A. G., Wagner S., Kennedy B. J., Miall F., Hills R., Devereux S., Oscier D. G., Dyer M. J., Fegan C., Pepper C. (2011) CD49d is an independent prognostic marker that is associated with CXCR4 expression in CLL. Leukemia Res. 35, 750–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polman C. H., O'Connor P. W., Havrdova E., Hutchinson M., Kappos L., Miller D. H., Phillips J. T., Lublin F. D., Giovannoni G., Wajgt A., Toal M., Lynn F., Panzara M. A., Sandrock A. W., Investigators A. (2006) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Esposito C. L., Catuogno S., de Franciscis V., Cerchia L. (2011) New insight into clinical development of nucleic acid aptamers. Discov. Med. 11, 487–496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.