INTRODUCTION

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research and Development convened a group of experts (authors on this guest editorial) to identify key rehabilitation research opportunities. Our first task was to examine the important themes of rehabilitation research to serve as a guide to the identification process. Rehabilitation research encompasses a broad field of disciplines and methodologies covering the full spectrum of basic to applied science. Important themes for rehabilitation research include prevention, improvement, restoration, and replacement of underdeveloped or deteriorating function [1]. The use of the term “function” refers to the level of impairment, activity, and participation as defined by the World Health Organization [2]. An anonymous reviewer of this editorial noted that rehabilitation researchers are practitioners and investigators of the “science of recovery.” Rehabilitation research operates within three domains of investigation: (1) physiological function (molecule, cell, tissue, and organs), (2) physical and mental function, and (3) social and community integration and design and delivery of rehabilitation services [3].

In defining areas of research opportunity, we do not intend to suggest an exclusive focus on the proposed topics and we fully support other creative approaches. Within each of the three domains of investigation identified previously, this editorial provides examples and highlights areas of interest but does not fully describe each potential research area of interest, nor does it cover all areas.

PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTION (MOLECULE, CELL, TISSUE, AND ORGANS)

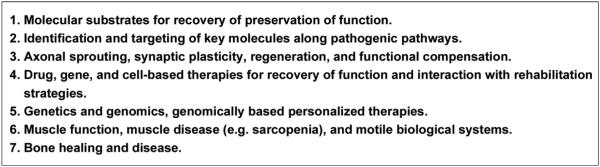

It is important to understand the mechanisms of disease or injury relating to impairment. In considering research opportunities, we identified seven areas within the domain of physiological function (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Areas of opportunity in rehabilitation research: molecule, cell, tissue, and organs.

Molecular Substrates for Recovery and Preservation of Function

An example of the molecular substrates for recovery relates to the process of demyelination in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). The finding that a persistent current mediated by abnormally long regions of expression of Nav1.6 sodium channels triggers axonal degeneration in animal models of MS [4] has provided the basis for current clinical studies on sodium channel blockers as potential neuroprotective agents in MS [5]. Likewise, understanding molecular substrates for recovery and preservation of function is critical for developing treatments for spinal cord injury (SCI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) and in all other areas of rehabilitation research.

Identification and Targeting of Key Molecules Along Pathogenic Pathways

Changes in potassium channel expression in demyelinated fibers have been demonstrated in the demyelinating diseases [6]. These studies provided the rationale for the development of the potassium channel blocker, 4-aminopyridine, as the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapy for restoring function in MS [7]. Understanding cellular physiological changes in both animal models and in people with disabilities has also led to deep brain stimulation, the most significant advance in the treatment of Parkinson disease (PD) since the introduction of L-DOPA in the 1960s [8–9]. Neurophysiological analysis of both nonhuman primates treated with the toxin MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) as well as patients with PD identified over-activity in brain regions such as the subthalamic nucleus and the globus pallidus interna as a major contributor to abnormal motor function [10]. FDA-approved implanted devices inhibit this activity, and their benefits have been well documented [11]. These examples illustrate the benefit of research efforts focused on identifying and understanding molecular pathways associated with disease mechanism.

Axonal Sprouting, Regeneration, and Functional Compensation

The role of growth or trophic factors on the nervous system has undergone a transformation from molecules in early development to potential therapies for both neurodegenerative diseases and injury. Factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) have been well studied, both with regard to their mechanisms of action and their protective and restorative effects in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases and SCI [12–14]. Translation of these factors into effective protein-based therapeutics has been a major challenge. Gene-based strategies, such as the injection of viral vectors expressing NGF in Alzheimer disease (AD) or the GDNF homolog neurturin in PD, are undergoing clinical trials as a means of administering biologically active amounts of these factors to brain regions undergoing degeneration [15–16]. Enhanced understanding of these factors and their clinical use will have a profound effect on treatment of a variety of conditions, including SCI, TBI, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Drug, Gene, and Cell-Based Therapies for Recovery of Function

A variety of cell-based therapies are under development for neurodegenerative diseases, stroke, TBI, and SCI. Both embryonic stem cells and adult mesenchymal cells secrete a variety of potentially beneficial substances that have both anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective qualities [17–18]. The feasibility and safety of infusion of autologous (adult-derived) bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells has been demonstrated in phase I studies in human subjects [19]. Cell-based therapies are viewed as major components of regenerative neuroscience and medicine.

Recent studies are developing more efficient protocols for conversion of embryonic stem cells into dopamine-producing neurons with the potential to replace degenerating cells in patients with PD [20]. Translation of such neuron replacement therapy will be a challenge, where cells will need to both differentiate appropriately and form functional connections with the host brain. The forms of potential cell-based therapies continue to expand. Not only can adult somatic cells be induced to form lines of pluripotent stem cells with properties of embryonic stem cells (induced pluripotent stem cells) but recent studies have demonstrated that adult human fibroblasts can be converted into functioning neurons [21–22]. The identification of genes that orchestrate neuronal development, such as those coding for transcription factors, has made these novel cell-based therapies possible.

Drug-based therapies targeting acute secondary injury mechanisms for TBI have shown tremendous potential in experimental models but have yet to be successfully translated to clinical trials [23]. However, drug-based therapies targeting chronic intervals may have potential for attenuating injury-related neurodegeneration and stimulating recovery mechanisms. Another opportunity is to examine the rehabilitation benefits of drugs approved for other indications. An example is statins, which have been shown to have a neuroprotective effect in experimental central nervous system (CNS) disease models [24].

Muscle Function, Muscle Disease, and Motile Biological Systems

While conditions such as stroke, SCI, and TBI are primarily associated with neurological consequences, they can also affect multiple body tissues as well as cellular structure and function. Nowhere is this more evident than in the effect on skeletal muscle, where molecular regulation of fiber type, metabolism, and contractile function is a rapidly growing research theme in both neurological disability and age-related functional declines. The biology of sarcopenia (muscle wasting) in aging and disuse atrophy, both of which lead to weakness and insulin resistance, are important areas of geriatric muscle-molecular biology research.

Increasing data suggest that both these conditions are modulated by master transcriptional regulators of muscle molecular phenotype, metabolism atrophy or hypertrophy signaling, and that these are modifiable by physical activity, altered neural innervation, and possibly, pharmacologically. SCI and stroke produce strikingly similar downstream pathologies in skeletal muscle that include atrophy, increased muscular area fat, and a major shift from slow twitch to the fast myosin heavy chain molecular phenotype. Research in such areas as activity-dependent plasticity (including calcineurin-related pathways) and activation of PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha), which upregulates slow twitch muscle expression and glucose metabolism, constitute an opportunity for rehabilitation research to innovate chronic disease management models in neurological disease as well as aging. Also important is understanding and treating acute musculoskeletal injuries.

Bone Healing and Disease

The key to developing effective therapies for bone loss is understanding the regulatory network for skeletal progenitors and downstream mediators. Understanding bone adaptation and healing will help development of new therapeutic targets for traumatic injury, osteoporosis, and other bone issues. Connective tissue regeneration is also important to bone healing and function. Important topics for future research include implantable cartilage, cellular therapy such as stem cell homing, cell-cell communication, and others.

Genetics and Genomics: Genomically Based Personalized Therapies

Genomics applied to rehabilitation carries great potential to assist in understanding molecular mechanisms of disease, injury, and recovery, as well as clinical effectiveness of therapies. Additionally, the field will greatly assist in identification of new potential targets, understanding responsiveness to clinical treatment, and potential targeting of rehabilitation therapy approaches. Genetic variability association with the recovery process, response to rehabilitation, and recovery outcome are all areas of interest for rehabilitation genomics. Examples include work focused on outcome after TBI and several candidate genes related to neuroplasticity (BDNF gene), blood flow (ACE [angiotensin-converting enzyme] gene), and apoptosis (TP53) [25–26]. Genomic studies and functional profiling have also demonstrated the presence of single amino acid substitutions that increase or decrease the sensitivity of target channels to pharmacological agents, suggesting that personalized or genomically based approaches to pain pharmacotherapy are possible [27–29]. The identification and subsequent validation of candidate genes can open new research approaches related to understanding the biological pathways associated with conditions and recovery mechanisms of interest.

PHYSICAL AND MENTAL FUNCTION

Within the domain of physical and mental function, we identified 35 key areas of opportunity within rehabilitation research (Table). Also important to this domain are medical complications of disabling conditions, including venous thromboembolism, pressure ulcers, and wound infections. In addition, understanding the rehabilitation of medically complex patients and postintensive care syndrome are of interest. These 35 areas are grouped into 8 categories, which are briefly described next.

Table.

Areas of opportunity in rehabilitation research: physical and mental function.

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Aging and Impairment | Successful aging with chronic illness and/or disability. |

| Role of mood and cognition in successful aging. | |

| Cardiometabolic risk factors and aging. | |

| Cognitive Impairment | Understanding interplay of cognitive and emotional issues and their effect on rehabilitation. |

| Developing interventions that remedy cognitive and emotional issues in rehabilitation. | |

| Exercise and Motor Learning | Activity-dependent (including cognitive exercise) plasticity/regeneration and cognitive function. |

| Understanding relationship between physical activity and biological changes in muscle/bone. | |

| Physical activity and effect on physiological systems, quality of life, functional ability, and pre- vention of illness (e.g., secondary stroke prevention and pelvic floor muscle training for uri- nary and fecal incontinence). |

|

| Understanding continuum of structured physical activity (i.e., types of exercise) and effect on health. | |

| Models of motor function/optimizing motor function. | |

| Effects in muscle of central nervous system-based trophic factors. | |

| Neurodegeneration | Neurodegenerative diseases and relationship to traumatic injury. |

| Neurodegenerative diseases and development of new treatment approaches and targets. | |

| Importance of disease-modifying approaches to slow neurodegeneration and improve quality of life. Translational clinical strategies in progress include (1) modification of beta amyloid, Tau, and alpha-synuclein load to reduce disease pathology; (2) growth factor gene therapy to reduce cell death and improve cell function in Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease; and (3) anti-sense oligonucleotide therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. |

|

| Pain | Understanding contributors to chronicity in pain: What are drivers of chronic neuropathic pain? |

| Understanding molecular and cellular basis for pain: development of new therapeutic targets and approaches. |

|

| Understanding transition from acute (nociceptive, and sometimes protective) pain to chronic, unprovoked (often neuropathic) pain. |

|

| Understanding integrative and cognitive basis for pain: development of new therapeutic approaches. | |

| Pain as comorbidity and moderator and mediator. | |

| Sensory Issues | Understanding sensory issues related to injury, aging, and neurodegeneration. |

| Optimizing rehabilitation models for low vision, auditory impairment, and other sensory deficits. | |

| Technologies to promote improved functional outcomes and community reintegration. | |

| Spinal Cord Regeneration | Mechanisms of regeneration. |

| Cellular and extracellular environment supporting axonal growth (e.g., matrices). | |

| Growth factors and inhibitors. | |

| Mechanisms to deliver therapeutics (e.g., growth factors, matrices). | |

| Neural stem cells. | |

| Development and evaluation of rehabilitative therapies for spinal cord injury. | |

| Prevention and treatment of secondary complications. | |

| Health promotion and maintenance of post-spinal cord injury. | |

| Assistive technologies. | |

| Motor Issues | Paralysis. |

| Bladder and bowel control, sexual function and adaptation. | |

| Respiratory support/upper airway. | |

| Oral, speech, and swallowing. |

Aging

Aging has a profound effect on functional ability, outcomes, rehabilitative care plans, and treatment. As such, the effect of aging is an important topic for rehabilitative research. Language and other cognitive processes (e.g., memory, attention, decision making) are readily susceptible to the effects of aging, injury, or disease. Impairments to language and or memory can affect quality of life and produce barriers to employment, social relationships, and leisure activity. Identifying new rehabilitation strategies to enhance cognitive function and emotional health are important research areas [30].

Recent work has shown that executive functions (goal setting, planning, decision making, etc.) are especially vulnerable to the effects of vascular risk, which increases with age. This relationship is consistent with the pattern of gray matter changes and white matter integrity loss found to vary systematically with vascular risk [31–33]. These data suggest that systemic cerebrovascular health for the whole person may play a role in neural tissue degeneration in brain areas critical for executive functions.

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment associated with disease or injury is an important theme for rehabilitation research. The cognitive sequelae of TBI and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are important themes for rehabilitation research. Evidence suggests that TBI may be a risk factor for several neurodegenerative disorders [34]. Several studies have implied an effect of repeated episodes of concussion in combat and potential cumulative effects related to the parallel and noninteractive development of PTSD and prolonged sequelae of mild TBI [35–36]. New therapies for the treatment of PTSD and TBI are of particular interest, e.g., the centrally acting alpha-adrenergic blocking agent, prazosin, to reduce the frequency and/or severity of nightmares [37–38].

TBI and PTSD can cause a constellation of overlapping physical and emotional symptoms that are associated with cognitive deficits, including executive and attentional dysfunction [39]. Blast injury may exacerbate these relationships and pose additional challenges for the development of successful treatments [40]. Additional research is needed to fully understand any effect of blast exposure on outcome. Depression has significant effects on cognitive function across a broad array of clinical issues relevant to Veteran rehabilitation research. Later-life depression is associated with cognitive deficiency and increased risk of developing AD [41]. Models of depression and AD implicate glucocorticoids and cerebrovascular disease as primary mechanisms leading to neuropathological changes [42].

Exercise and Motor Learning

Physical inactivity is a strong predictor of physical disability in older adults, and physical activity patterns decrease as a function of age [43]. Maintaining a physically active lifestyle is associated with prolonged longevity and a reduced risk of becoming physically disabled [44]. Physical activity has been demonstrated to improve quality of life by improving overall well-being [45], reducing physical symptoms [46], reducing depressive symptoms [47], and improving self-efficacy [48]. Further research is needed to understand the dose, timing, and modalities of exercise to optimize long-term health outcomes and how to best synergize exercise with motor learning, nutrition, and clinical pathways across the continuum of care.

Aerobic exercise produces improvements in a range of cognitive domains, including auditory and visual attention, processing speed and motor function, and planning and working memory [49–50]. Exercise has a broad role in causing, preventing, and treating select medical conditions. Exercise-mediated cognitive improvements are, in general, most robust for executive control: an area of cognitive function typically most impaired in stroke, TBI, schizophrenia, and aging with vascular risk factors [51]. Although the mechanisms by which exercise affects cognition and affect are not conclusively delineated, several studies have documented a positive association between exercise and brain activation in the frontal and parietal cortices, production of BDNF, and improved autonomic function [52–53].

Recent advances in neuroimaging methods have enabled researchers to link alterations in brain structure (e.g., cortical thickness, tissue integrity) and function (e.g., resting brain networks) with cognitive change in response to cognitive training and physical exercise [54–56]. The use of neuroimaging to investigate the neurobiological effects of cognitive and physical exercise is currently limited but has broad implications for guiding the development and evaluating the efficacy of rehabilitative strategies for cognitive and emotional function in aging, neurodegenerative disease, and brain injury.

Neurodegeneration

As the proportion of the elderly population increases, so does the number of individuals afflicted with neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, PD, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Identifying aberrant processing of the amyloid precursor protein as a major risk for the development of AD-type dementia has led to the development and testing of several new classes of drugs to prevent or slow disease progression, including amyloid-modifying compounds that are in clinical trials [57]. Greater understanding of the biochemistry and role of the structural protein tau in neurons has also led to clinical trials in AD that target this mechanism [58]. The finding that growth factors can prevent cell death arising from diverse mechanisms and can stimulate cell function has led to trials in AD, PD, and ALS [59]. In PD, appreciation for the importance of intracellular accumulation of alpha-synuclein in neuronal degeneration has led to the development of new therapies in animal models that are in the process of undergoing clinical translation [60–61]. Progress in understanding fundamental risks associated with the development of spinal motor neuron loss, including the role of glia, is leading to new approaches to the treatment of ALS [62].

Spinal Cord Regeneration

A topic of great interest in SCI research over the last several decades has been the elucidation of mechanisms that underlie the failure of central axons to regenerate. Several mechanisms, both intrinsic and extrinsic to the adult neuron, contribute to regenerative failure. First, in the injured environment, cystic lesion cavities fail to become filled with cellular or extracellular matrices to support growth. Accordingly, experimental efforts aim to place permissive matrices (both natural and bioengineered) into the lesion site to support axonal growth. Second, growth factors are not expressed at sites of SCI in appropriate spatial or temporal gradients to promote the recruitment of new axonal growth. This is in marked contrast to the regenerating peripheral nerve wherein Schwann cells produce a number of growth-promoting molecules, including NGF, BDNF, neurotrophin-3, GDNF, and others [63]. Third, two classes of molecular inhibitors to growth are present in the lesioned CNS to actively block axonal growth: inhibitory extracellular matrix proteins, including chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, and inhibitory proteins present on adult myelin, including Nogo, myelin-associated glycoprotein, oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein, netrin, semaphorins, Wnt proteins, and others [64–66]. Finally, unlike peripherally injured neurons, centrally injured neurons fail to upregulate a repertoire of genes to support an active, intrinsic growth state.

Based on these findings, experimental therapies aim to (1) place bridges in spinal cord lesion sites, (2) deliver growth factors, (3) neutralize or eliminate inhibitors of growth, and (4) activate the intrinsic growth state of the neuron. Individually, many of these approaches incrementally improve axonal regeneration. When combined, the effects of these experimental interventions are more potent, resulting in the first successes in achieving axonal regeneration into and beyond spinal cord lesion sites over the last few years [67–68]. To improve function in humans, additional progress is needed. Primarily, the number of axons and the distance over which axons will regenerate needs to be substantially improved to have detectable benefit in human trials.

Pain

Pain is almost universally experienced as a concomitant of most physical and behavioral health impairments. Pain has been identified as an important moderator of the effectiveness of treatment for common mental health conditions, including depression, substance use disorders, and PTSD [69]. Reduction in pain may mediate improvements in the rehabilitation of other disabling conditions such as stroke [70]. Consistent with these observations, current trends in rehabilitation research encourage the development and evaluation of integrated treatment and rehabilitative approaches [71].

Existing medications might, at sufficient dosages, be effective in treating pain, but their efficacy is limited by off-target side effects, including ataxia, confusion, sedation, cardiac arrhythmias, and dependency. This is especially true for pharmacological blockers of sodium channels that support the firing of neurons. A goal of pain research has been the search for sodium channel subtypes that are selectively or preferentially expressed in pain-signaling neurons. Research has identified a sodium channel that is specifically produced only in pain-signaling neurons and a sodium channel subtype that is upregulated in injured pain-signaling neurons. This identification has led to the functional profiling of other sodium channel subtypes that are primarily expressed in peripheral neurons [72–75]. These studies have demonstrated how these channels work together to generate pain signals [76]. Studies of rare inherited pain syndromes have pinpointed pivotal molecules that drive pain signaling by identifying, for the first time, a single gene or gene product, the Nav1.7 sodium channel, that is a major contributor to human pain [77–78].

A major challenge in understanding pain lies in the transition from acute pain to chronic, unprovoked (often neuropathic) pain. Neuropathic pain takes on a life of its own, arising not from a noxious external stimulus but from disease or dysfunction of the nervous system itself. Such pain negatively affects quality of life in many after nerve injury or SCI, in association with diabetic neuropathy, and as a complication of cancer chemotherapy. Further, this type of chronic pain is often refractory to existing pharmacotherapies and represents a major challenge for millions. In order to develop more effective therapies, understanding the factors that trigger and maintain neuropathic pain as well as the transition from acute nociceptive pain to chronic neuropathic pain is needed. One such trigger is synaptic strengthening caused by central sensitization along the pain-signaling pathway. Recent studies have demonstrated major contributions from dysregulated expression of ion channels that increase the excitability of pain-signaling neurons [79–80].

In addition to molecular and cellular changes, there is evidence that psychosocial factors may be linked to the perpetuation, if not the development, of chronic neuropathic pain and pain-related disability. High levels of maladaptive coping, high baseline functional impairment, presence of psychiatric comorbidities, history of sexual trauma, and low general health status have been found to be particularly reliable predictors of poor outcomes [81–82].

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been demonstrated to be effective, either delivered alone or in the context of interdisciplinary and multimodal approaches for the management of pain associated with a broad array of disabling medical conditions [83–84]. Patient motivation and readiness to adopt a pain self-management approach have been identified as reliable predictors of psychological treatment engagement and adherence to therapist recommendations for pain coping-skill practice and have been highlighted as particularly important targets for intervention [85–86]. Continued research is needed to overcome barriers to access and engagement to effective therapies and to develop new novel therapies, including nonpharmacological treatments.

Sensory

Visual

Millions of Americans have a visual impairment, with prevalence estimated at 3.1 percent [87]. In addition to vision loss itself, the associated diseases lead to substantial individual and societal costs as well as disability. Important foci for research in this area include understanding the mechanisms associated with disease and injury that contribute to vision loss; diagnosing and treating conditions leading to vision loss; and developing assistive equipment and tools that support this research, such as high-resolution retinal imaging. Within these areas, important topics include (1) understanding optic neuroprotection; age-related macular degeneration and other retinopathies; optic neuropathy caused by glaucoma ischemia, compression, toxins or trauma, and diabetic retinopathy; (2) identifying biomarkers for disease, injury, and response to treatment; subretinal and transcorneal electrical stimulation; and (3) assessing via computers and detecting visual field loss and imaging modalities for assessment of structure and function of the visual system that can also be applied to remote, telemedical assessment; retinal prosthesis; and wayfinding and mobility devices. In addition, recent evidence has shown that degenerative disorders affecting the CNS, such as MS, TBI, PD, and AD, can also affect the layers of the retina and neural pathways mediating vision and eye movements. Assessments of visual and oculomotor function (e.g., eye movements, eyelid movement and blinking, accommodation and pupil movements) and retinal structure may provide easily quantifiable ancillary rehabilitatory tools to assess CNS disorders and their treatment.

Auditory

The prevalence of hearing loss is increasing at 1.6 times the rate of population growth in the United States—due primarily to the shift in population demographics toward higher age groups [88]. It is estimated that over 34 million Americans have some degree of hearing loss. This trend is particularly prevalent in the Veteran population where tinnitus and hearing loss are the most common and second-most common of all service-connected disabilities for Veterans, respectively [89]. The primary remediation for hearing loss is the use of hearing aids. However, three of every four people with hearing loss (and 6 of every 10 people with moderate-to-severe hearing loss) do not use hearing aids. Further, many patients who wear hearing aids are dissatisfied with their performance.

Numerous studies have examined the reasons why individuals with hearing loss tend to be satisfied or dissatisfied with treatment. There is general agreement that outcomes are associated with the hearing aid itself, in combination with individual differences in auditory, cognitive, and psychological factors [90–91]. Research is needed in the areas of evaluation, treatment, and ongoing rehabilitation to increase the use and effectiveness of hearing aids and/or assistive listening devices.

Anything that can cause hearing loss can also trigger the onset of tinnitus. Based on multiple studies, the prevalence of tinnitus in adults in the United States is estimated at 10 to 15 percent [92]. It was recently reported that Veterans have twice the prevalence of tinnitus as non-Veterans [89]. Most tinnitus interventions focus on reducing reactions to tinnitus rather than attempting to mitigate the sensation [93]. Research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the most promising treatments and to identify patient characteristics that are associated with the effectiveness of various treatments.

Motor Issues

Motor control and motor learning are important areas of concern for rehabilitation researchers. Two example conditions frequently associated with motor issues are SCI and stroke. SCI can cause loss of voluntary control and involve movement of the arms and hands, trunk, lower limbs, breathing and cough, bladder and bowel function, and sexual function. Pain and spasticity may also be encountered. Findings show that latent pathways of the spinal cord may be facilitated by activation through induced movement such as robotic devices and body-weight supported treadmill training combined with low-level electrical stimulation delivered epidurally to the spinal cord [94].

With regard to stroke, there is evolving evidence that patients retain the capacity to regain function for extended periods after their original insult. This outcome is due to the plasticity of the cerebral cortex that enables areas of the brain to be reassigned the control tasks [95]. Repetitive activity is well suited to technologies that supplement the actions of the therapist and allow professionals to direct their attention toward higher-level intervention. Robotic devices that augment the patient’s own effort are well suited to repetition, as are interventions that employ electrical stimulation delivered to the muscle. Another important issue facing patients with stroke is swallowing and aspiration (dysphagia). Appropriate management of dysphagia is important for patients with stroke because it can lead to poor nutrition and increased disability. In addition to these areas, other important topics include research focused on pulmonary rehabilitation and speech and language recovery.

NEW TECHNOLOGICAL APPROACHES AFFECTING REHABILITATION

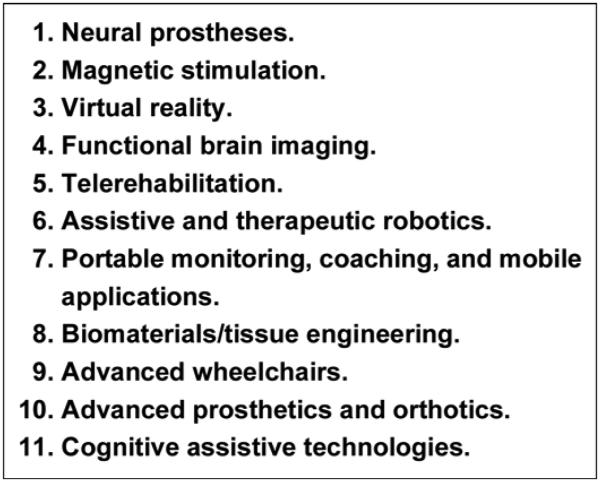

Within the domain of new technological approaches affecting rehabilitation research, Figure 2 identifies 11 key areas of opportunity. Of the many technological approaches affecting rehabilitation, these areas identified in Figure 2 are highlighted because of recent improvements in their use either clinically or in research.

Figure 2.

Promising new technological approaches affecting rehabilitation.

Neural Prostheses

Neural prostheses are often divided into two categories: motor and sensory. These medical devices are generally implanted with the goal of restoring some aspect of either motor or sensory function that has been lost elsewhere in the body due to injury or disease, such as SCI or stroke. In restoration of movement, neural prostheses are used to stimulate intact upper motor neurons that are still connected to paralyzed muscle (striated or smooth). In attempts to restore sensation, neural prostheses are used to stimulate intact sensory neurons that are still ultimately connected to the brain but whose peripheral sensory receptors have been damaged. Neural prostheses have been used to restore some voluntary control of paralyzed upper and lower limbs, trunk control and postural stability, bladder and bowel control, and breathing and cough and for building muscle tissue for prevention of pressure sores [96]. Lower-limb systems can restore some ability to stand, transfer from one surface to another, and some walking capability.

Neural prostheses also include brain-computer interface systems. These systems use a variety of neural recording technologies on the skin or brain surface or penetrate into the brain for recording cortical neural signals and translating them into information that can be used to control other devices, such as computers, motor neural prostheses, or electromechanical prosthetic limbs [97]. The more complex systems use a small array of invasive penetrating recording electrodes that can record electrode potentials from single cells and integrate the activity from multiple cells to create control information. A recent article describes two people with tetraplegia using an implanted 96-channel microelectrode array in their motor cortex to control a robotic arm to perform complex reach and grasp movements [98].

Electrical stimulation provides a means of restoring some bladder control. Stimulation of the sacral roots either in the extradural or intradural space can generate significant bladder pressure. Relaxation of the external sphincter appears to be feasible by either inducing a reflex relaxation through the pudendal nerve or by blocking activity to the external sphincter, e.g., through the high-frequency blocking technique [99]. Restoration of bowel function has not been as extensively researched as restoration of bladder function. While newly advancing bladder systems are expected to have a similar effect on the bowel as earlier devices, additional research will be necessary.

Sensory neural prostheses are typified by devices such as the cochlear implant, which stimulates the endings of the auditory nerve when the hair cells have been destroyed. There have also been successful preliminary clinical results in stimulating the optic nerve when the photoreceptors of the retina have been damaged [100].

Magnetic Stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) involves the discharge of a large capacitor into a conductive coil positioned over the scalp, with the rapidly changing current in the coil generating electric fields in the brain [101]. TMS techniques include methods to both stimulate and inhibit cortical function. TMS has been shown to improve language function after stroke [102]. The presence of TMS-evoked motor potentials has been found to be predictive of recovery after stroke [103–104]. Impairments of the corticobulbar system in the form of motor speech disorders, caused by decreased excitability of the cerebral cortex, have also been shown to be amenable to treatment with TMS in PD [105–107]. Repetitive TMS stimulation designed to suppress activity in the unaffected hemisphere can enhance motor and language performance generated from the affected side [108]. A more recent type of repetitive stimulation, theta-burst stimulation, can transiently improve the efficacy of the affected motor cortex [109].

In the future, TMS may increasingly become part of an evidence-based rehabilitation practice in which measurement of neuronal and clinical deficit result in application of a rehabilitation program specifically designed to reverse that deficit. New methods of noninvasively stimulating the brain are also being developed, including transcranial direct current stimulation, and these may supplant TMS when the goal is the neuromodulation of wide areas [110].

Functional Brain Imaging

Many forms of advanced imaging are important tools of interest for rehabilitation research. Functional brain imaging is of particular interest because of the potential to measure brain activity in the context of brain function. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most widely used, and other techniques include positron emission tomography, near infrared spectroscopy, and electro/magneto-encephalography.

The use of functional imaging to measure brain activity related to movement, language, and other cognitive functions after stroke has led to several conclusions related to brain reorganization, although the field has been fraught with controversy. Much of this has to do with the functional role of brain areas that are activated during task performance. For example, in aphasia resulting from stroke, there is frequently activation of nondominant hemispheric homologs of language areas. However, this activity appears to correlate with poorer function and, when suppressed, can lead to better recovery [111]. In the realm of motor recovery and rehabilitation, non-primary motor areas in both hemispheres are frequently active during motor tasks after stroke, and many appear to contribute to the recovered ability to move [112]. As with TMS, prediction of recovery is also possible with functional imaging [113]. Future developments in this area may enhance understanding of neuronal function during recovery and thus be a useful tool for rehabilitation research.

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality (VR) systems in rehabilitation consist of a computer, software, various types of display devices, and mechanisms for user interaction (gloves, sensors, treadmills, etc.). Haptic and other sensory feedback may also be part of the system. VR systems are well suited to simulate naturalistic environments where rehabilitation patients have challenges. VR systems have been successfully used for improvement of balance and ambulation poststroke; skill training; and motor rehabilitation for TBI, SCI, and in other areas [114–115]. VR systems for rehabilitation could provide an enhanced approach for controlled functional measurement in a variety of applications.

Telerehabilitation

Telehealth encompasses a range of clinical services performed when distance separates provider and patient. These services include medical diagnosis, health monitoring, and therapy. A meta-analysis of 29 home-based telehealth studies revealed an overall positive effect of a variety of interventions on clinical outcomes in diverse patient populations [116].

An example of telehealth for rehabilitation is tinnitus management for Veterans and military personnel with TBI [117]. Another example is the emerging use of remote monitoring devices to assess visual structure and function [118]. Development of automated image analysis of retinal and optic nerve images collected remotely allows disorders such as macular degeneration, glaucoma, papilledema, and diabetic retinopathy to be diagnosed and monitored for effective treatment and more efficient triage [119–122].

Robotics

Robotic-assisted rehabilitation has long offered the promise of repetitive task practice without therapist fatigue, programmability to customize motor learning paradigms, measurement capacity to empirically progress training and quantify outcomes, and efficiency to possibly reduce costs. Until recently, data establishing comparative effectiveness of robotics to usual care or other forms of rehabilitation were not available. In Veterans with chronic stroke, robotic-assisted rehabilitation for upper-limb function had similar treatment benefits to aggressive occupational therapy and was more effective than usual care [123]. Emerging research themes in this area are testing modular, lower-limb, multi-segmental, and whole body exoskeletons; advanced control algorithms; novel motor learning paradigms; and patient-robot interfaces to enhance control and/or usability.

Portable Monitoring and Mobile Applications

Portable monitoring is rising in use along with telehealth to improve the outreach, customization, and quality of rehabilitation and related services. Examples of portable monitoring methodologies that have entered clinical translational research relevant to rehabilitation include continuous monitoring of physical activity, eye structure and function, body position, surrogate measures of balance, electroencephalography, geo-location, select cardiopulmonary parameters, and integrated sleep apnea/integrity monitoring systems. An example is a microprocessor-linked step monitor that was shown to be accurate in counting steps in patients with stroke [124]. Newer generations of monitors include wearable technology and accelerometers coupled with gyroscopes and linked to smartphones, making portable whole-body movement analyses and feedback to track and improve the quality, quantity, and safety of multi-segmental movements and balance a new frontier in rehabilitation research [125]. Smartphone applications also provide mechanisms to deliver context relevant information as well as gathering data.

Biomaterials/Tissue Engineering

Bioengineering advances have the potential to improve regenerative therapies for SCI. Nanotechnology has allowed the fabrication of synthetic bridges to guide axons into and through sites of SCI [126–127]. Bioengineered matrices can be loaded with therapeutic substances, including growth factors, that are gradually released over time to further enhance axon regeneration. Engineered nanofiber scaffolding constructs are also being developed to improve the delivery of progenitor cells in CNS injury [128]. Biomaterials and tissue engineering techniques have been used in a wide array of areas, including development of cartilage, bladder, skin, and biomaterials for bone tissue regeneration. These approaches are important for the future of rehabilitation and rehabilitation research.

Advanced Wheelchairs

Effective wheelchair mobility requires that the person and wheelchair work together intimately to form an effective human-machine system. The interactions vary from mechanical interfaces, such as seating, positioning, and propulsion, to control and sensing interfaces that operate on a sliding scale of autonomy and assistance. Optimal wheelchair mobility promotes the wheelchair and user working symbiotically as one from physical, sensory, and control perspectives [129]. Significant problems remain with secondary conditions associated with wheelchair usage, such as repetitive strain injury, pain, deformities, tissue integrity, and functional limitations [130]. It is essential to understand the interaction between the fixed and flexible built environment in order to facilitate full participation of wheelchair users. It is also important to understand tasks such as transfers, obstacle negotiation, and whole-body vibration [131]. In addition, providing enhanced mechanisms for transfer assistance is needed. Research is needed into fixed and mobile dexterous manipulators [132]. There are still many technical, social, and behavioral barriers to overcome related to wheelchairs and their users.

Advanced Prosthetics and Orthotics

Prosthetics and orthotics continue to evolve and improve for both upper- and lower-limb applications. Perhaps the most dramatic example of success in lower-limb prosthetics was an individual with bilateral below-knee amputation running in the 2012 London Olympics and competing at the highest athletic level. An example of a new approach is the actively powered foot/ankle prostheses. When compared with passive-elastic prostheses, this approach resulted in decreased metabolic energy costs and increased walking velocities [133]. Other examples include advanced upper-limb prosthetics that allow many more degrees of freedom of movement than previously available in upper-arm prosthetics [134]. Dexterous hands and arms that have nearly anthropometric movement have been developed.

Even with these major advances, significant challenges remain for completely compensating for limb loss. Advanced upper-limb prosthetics face challenges in obtaining sufficient control signals from the user to control multiple degrees of freedom. Lower-limb prosthetics continue to face challenges in areas such as allowing users to walk over uneven terrain and stairs or the ability to easily change gait velocity. Other than vision and extended physiological proprioception, prostheses do not, in general, provide sensation to the user. Researchers continue to investigate methods of providing sensory feedback, either by vibration or low-level electrical stimulation to remaining sensory nerves.

Another significant issue is attachment of the prosthesis to the body. Currently, the socket is the means for attachment of a prosthesis to the residual limb. There are many unsolved problems with the fitting of sockets, such as changes in limb volume during the day and over time, temperature, perspiration, and the sometimes frequent breakdown of the skin due to pressure. Advances in osseointegration, direct attachment of the prosthetic to the bone, may someday provide a means for improving the attachment of the prosthesis [135]. Dental implants have demonstrated the potential for these new interfaces, and new materials for biointegration and stable skin interfaces make these interfaces appear feasible for prosthetic application. Another area of research is phantom pain. Elimination or mitigation of the pain response is important for the person with amputation. Targeted muscle reinnervation has yielded some encouraging results as a method to reduce or eliminate phantom-limb pain in some individuals.

SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY INTEGRATION AND DESIGN AND DELIVERY OF REHABILITATIVE SERVICES

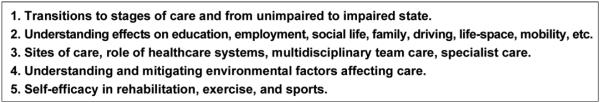

Within the domain of social and community integration and design and delivery of rehabilitative services, Figure 3 identifies five key areas of opportunity within rehabilitation research.

Figure 3.

Areas of opportunity in rehabilitation research: social and community integration and design and delivery of rehabilitation services.

Key to rehabilitative efforts is an understanding of the role of the social and community environment and social integration and its effect on one’s physical condition. Strong social networking and a positive environment are relevant to both limiting the rate of natural decline as well as expediting the recovery process. The converse is also true; a limited social support system or nonaccommodating environment can result in suboptimal outcomes to otherwise manageable conditions.

Transitions to Stages of Care and from Unimpaired to Impaired State

The transition from an unimpaired to impaired state needs to be defined in terms that extend beyond the clinical environment and considered within the context of both how and where care is being provided and the transition environment. Seamless transition is especially a challenge when subtle decline is noted in an ambulatory or nonclinical setting and when the consequences are more social rather than medical (e.g., loss of job, family dissolution, incarceration). In these settings, there is often a mismatch among the care provided (or available), the degree of evolving impairment, and the social supports needed. Research designed to identify and intervene in nontraditional settings represents a novel effort at addressing these mismatches in disability needs and care settings [136].

Understanding Effects on Employment, Social Life, Family, Driving, and Life Space

Employment is often viewed in a more limited context as necessary for economic self-sufficiency and sustainment. However, several studies have also demonstrated the therapeutic effects of employment, particularly in settings that accommodate physical or cognitive limitations [137–139]. Self-worth, constructive engagement, and physical and cognitive conditioning are all related to employment status. Similarly, the role of social supports and social networking have long been recognized as critical to recovery efforts, while conversely, social isolation and withdrawal have a deleterious effect on the mental and physical functioning of individuals [140–141]. The contribution of caregivers and their effect on the rehabilitation process is also an important topic. In addition, it is important to develop and understand models of care for managing client, caregiver, and family psychosocial issues in rehabilitation. Individuals with limited social contact and poor social support systems coupled with limited financial resources are often the most vulnerable to a debilitating or disabling event [142]. In addition, the study of employment as a therapeutic tool to enhance and sustain rehabilitative outcomes (coupled or uncoupled with social supports and mentoring) represents an important research area.

Sites of Care, Role of Healthcare Systems, Multidisciplinary Team Care, and Specialist Care

While increased care coordination, including team-based care, is usually associated with improved outcomes, we have incomplete knowledge on how such care actually achieves the desired outcomes. Team-based care can also be costly and inefficient. Stroke rehabilitation outcomes, e.g., functional gains, length of stay, and discharge destination, were shown to vary by the characteristics of rehabilitation teams [143]. In addition, in a subsequent clinical trial, a process improvement intervention directed at team functioning was associated with improved stroke outcomes in the experimental versus control sites [144–145]. Further understanding relating to the dynamics of team-based care in rehabilitation in various care settings is an important topic for future research. In particular, understanding team functioning (or more broadly, processes of care) and its relationship with patient outcomes is an important area of focus.

Understanding and Mitigating Environmental Factors Affecting Care

Mitigating environmental factors include family issues such as domestic violence, emotional neglect, and home conditions. Understanding challenges associated with mitigating environmental factors affecting care can be considered within the context of homeless patients, who often present with extreme challenges associated with social integration. Musculoskeletal conditions and traumatic arthropathies are the most common comorbidities among homeless and imminent homeless (extreme poverty) cohorts and play a significant role in determining capacity to work and disability [146]. Important areas of inquiry for these high-risk populations include developing approaches for earlier identification and development of care models focused on employment and self-sufficiency. Still another area of future inquiry is identification of care models for those individuals who are treatment resistant or who have not done well in traditional care because of their social condition, destructive behaviors, or extensive needs.

Self-Efficacy in Rehabilitation

Self-efficacy refers to how confident a patient is about his or her abilities based on feelings of self-confidence and control [147]. The degree to which a patient believes that he or she is competent to manage a chronic condition can be directly related to treatment outcomes and the ability to self-manage the condition. An example intervention is education leading to self-management for chronic pain management [148]. In the past, urgent pain relief mostly depended on treatments such as opioid drugs or surgery. In current practice, it is recognized that effective management of chronic pain depends much more on patients’ own efforts and expectations. Another example of successful self-management is Progressive Tinnitus Management, which is used in the VA [149].

As patients become more actively involved in decisions affecting their clinical care in a recovery-oriented context, they naturally experience a greater sense of commitment to participate in the care management process. The movement toward patient engagement and self-care has resulted in a greater shift of responsibility from healthcare providers to patients for aspects of their disease management [150]. Accomplishing this shift of responsibility requires working with patients to help them understand their condition, participate in decisions regarding their management plan, develop and follow the plan, and monitor success of their self-management effort and revise the plan as needed. This overall approach is appropriately termed “collaborative self-management.” Understanding interventions and factors that enhance engagement in rehabilitation is an important area of research.

DISCUSSION

In addition to the research opportunities noted in this editorial, we identified several important themes as critical issues for rehabilitation research. These themes relate to translational rehabilitation research and methodological challenges associated with rehabilitation research.

Methodological Challenges, Measures, and Metrics

There are two critical challenges in conducting clinical trials in rehabilitation: the variation in clinical conditions underlying functional impairments and the range of individualized treatments provided in usual care. In prosthetics, for example, unique variations in and modifications to each piece of equipment may affect outcomes. Understanding the efficacy of rehabilitation interventions requires detailed knowledge regarding the complete array of services provided rather than just the length of stay or hours of therapy [151]. Further, rehabilitation interventions are often comprised of many components, require a team approach, and involve varied levels of patient engagement or participation.

The long-standing gold standard for evidence-based practice is a well-conducted, multicentered (phase III) randomized clinical trial. However, there have been very few large-scale clinical trials to test safety and efficacy for interventions in rehabilitative care. Some of the reasons for this relatively small number are associated with difficulty in standardization of rehabilitation protocols, use of appropriate control groups, and identification and recruitment of participants. Key challenges related to evaluating rehabilitation devices in clinical trials relate to their design for individual use and blinding. Often, blinding is not possible in clinical trials on technology. Although research methods exist to accommodate the challenges of small sample size, additional research is needed in the statistical methodology for alternative study designs that do not rely on large sample sizes [152]. Examples of these approaches are n of 1 studies and use of quasi-experimental designs.

A challenge for all clinical research, not just rehabilitation clinical studies, is the development of measures that relate to disability and impairment and also allow measurement of clinically meaningful change. Opportunities for research in this area include measures assessing cognitive function (including language), physiological function, and quality of life in the rehabilitation setting. In addition, tools to assess social integration and patient engagement are of interest.

Challenges Involved in Translational Research: Bench to Bedside

Translation of research from basic science into clinical development and use in clinical practice requires moving through two major barriers: human studies and translation of new knowledge into widespread use in clinical practice and healthcare decision making [153]. Development of new knowledge and clinical application is facilitated by the flow of information back and forth from the domains of basic and applied research, as well as the domains of clinical practice and the human environment. Rehabilitation research that is concerned with the integrative model of human functioning crosses all these domains [154].

Limited understanding of the biological mechanisms associated with rehabilitation domains presents a challenge in identifying potential molecular targets and interventions that could affect functional limitation. The identification of key molecular targets is a challenge for all translational research and is necessary for translating a biological discovery into a drug, device, or other intervention that will facilitate rehabilitation. Additionally, testing hypotheses in different models and in humans is also needed to validate therapeutic targets. Translational research requires the formation of many partnerships, including researchers, sponsors, clinicians, participants, and industry. Infrastructure such as experienced investigative teams, clinical research pharmacies (with regulatory support), pharmacogenomic laboratories, and advanced technology centers are needed to facilitate translational research efforts.

It is our hope that this editorial will serve to enhance interest and activity in the field of rehabilitation research, which holds a vital and important place in the scientific enterprise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Additional Contributions: We thank Louise Arnheim for her review and helpful suggestions regarding the manuscript. She was not compensated for her contributions.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this editorial are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the VA or the U.S. Government.

This article and any supplementary material should be cited as follows:

Ommaya AK, Adams KM, Allman RM, Collins EG, Cooper RA, Dixon CE, Fishman PS, Henry JA, Kardon R, Kerns RD, Kupersmith J, Lo A, Macko R, McArdle R, McGlinchey RE, McNeil MR, O’Toole TP, Peckham PH, Tuszynski MH, Waxman SG, Wittenberg GF. Opportunities in rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):vii–xxxii. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2012.09.0167

REFERENCES

- 1.Craik R, Chae J. Blue ribbon panel on rehabilitation research at the NIH [Internet] National Institutes of Health; Bethesda (MD): 2013. [updated 2012 Jun 7; cited 2012 Jul 2]. Available from: http://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/advisory/nachhd/Documents/Blue_Ribbon_Panel_201205.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health [Internet] World Health Organization; Geneva (Switzerland): 2002. [cited 2012 Jul 2]. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selzer ME, Dorn PA, Kupersmith J. Rehabilitation Research & Development Service: 2009 ORD local accountability for research [Internet] Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington (DC): Jan 13–14, 2009. [cited 2012 Jul 2]. Available from: http://www.research.va.gov/programs/pride/conferences/docs/accountability/rrd.ppt. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stys PK, Waxman SG, Ransom BR. Ionic mechanisms of anoxic injury in mammalian CNS white matter: role of Na+ channels and Na(+)-Ca2+ exchanger. J Neurosci. 1992;12(2):430–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00430.1992. [PMID:1311030] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waxman SG. Mechanisms of disease: sodium channels and neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis-current status. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(3):159–69. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0735. [PMID:18227822] http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn J, Blight A. Dalfampridine: a brief review of its mechanism of action and efficacy as a treatment to improve walking in patients with multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(7):1415–23. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.583229. [PMID:21595605] http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2011.583229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman H, Wichmann T, DeLong MR. Reversal of experimental parkinsonism by lesions of the subthalamic nucleus. Science. 1990;249(4975):1436–38. doi: 10.1126/science.2402638. [PMID:2402638] http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.2402638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Follett KA, Weaver FM, Stern M, Hur K, Harris CL, Luo P, Marks WJ, Jr, Rothlind J, Sagher O, Moy C, Pahwa R, Burchiel K, Hogarth P, Lai EC, Duda JE, Holloway K, Samii A, Horn S, Bronstein JM, Stoner G, Starr PA, Simpson R, Baltuch G, De Salles A, Huang GD, Reda DJ, CSP 468 Study Group Pallidal versus subthalamic deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2077–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907083. [PMID:20519680] http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0907083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, Hur K, Harris C, Marks WJ, Jr, Rothlind J, Sagher O, Reda D, Moy CS, Pahwa R, Burchiel K, Hogarth P, Lai EC, Duda JE, Holloway K, Samii A, Horn S, Bronstein J, Stoner G, Heemskerk J, Huang GD, CSP 468 Study Group Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(1):63–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.929. [PMID:19126811] http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL, Lozano AM, Volkmann J, Stefani A, Horak FB, Okun MS, Foote KD, Krack P, Pahwa R, Henderson JM, Hariz MI, Bakay RA, Rezai A, Marks WJ, Jr, Moro E, Vitek JL, Weaver FM, Gross RE, DeLong MR. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: an expert consensus and review of key issues. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):165. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.260. [PMID:20937936] http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollis ER, 2nd, Jamshidi P, Löw K, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Induction of corticospinal regeneration by lentiviral trkB-induced Erk activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(17):7215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810624106. [PMID:19359495] http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810624106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangasamy SB, Soderstrom K, Bakay RA, Kordower JH. Neurotrophic factor therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2010;184:237–64. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84013-0. [PMID:20887879] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang AE, Gill S, Patel NK, Lozano A, Nutt JG, Penn R, Brooks DJ, Hotton G, Moro E, Heywood P, Brodsky MA, Burchiel K, Kelly P, Dalvi A, Scott B, Stacy M, Turner D, Wooten VG, Elias WJ, Laws ER, Dhawan V, Stoessl AJ, Matcham J, Coffey RJ, Traub M. Randomized controlled trial of intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor infusion in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):459–66. doi: 10.1002/ana.20737. [PMID:16429411] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(3):209–19. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. [PMID:21358740] http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuszynski MH, Thal L, Pay M, Salmon DP, U HS, Bakay R, Patel P, Blesch A, Vahlsing HL, Ho G, Tong G, Potkin SG, Fallon J, Hansen L, Mufson EJ, Kordower JH, Gall C, Conner J. A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2005;11(5):551–55. doi: 10.1038/nm1239. [PMID:15852017] http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks WJ, Jr, Bartus RT, Siffert J, Davis CS, Lozano A, Boulis N, Vitek J, Stacy M, Turner D, Verhagen L, Bakay R, Watts R, Guthrie B, Jankovic J, Simpson R, Tagliati M, Alterman R, Stern M, Baltuch G, Starr PA, Larson PS, Ostrem JL, Nutt J, Kieburtz K, Kordower JH, Olanow CW. Gene delivery of AAV2-neurturin for Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(12):1164–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70254-4. [PMID:20970382] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichim T, Riordan NH, Stroncek DF. The king is dead, long live the king: entering a new era of stem cell research and clinical development. J Transl Med. 2011;9:218. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-218. [PMID:22185188] http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson RM, Singh A, Sun D, Fillmore HL, Dietrich DW, 3rd, Bullock MR. Stem cell biology in traumatic brain injury: effects of injury and strategies for repair. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(5):1125–38. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.JNS081087. [PMID:19499984] http://dx.doi.org/10.3171/2009.4.JNS081087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honmou O, Houkin K, Matsunaga T, Niitsu Y, Ishiai S, Onodera R, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 6):1790–1807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr063. [PMID:21493695] http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caiazzo M, Dell’Anno MT, Dvoretskova E, Lazarevic D, Taverna S, Leo D, Sotnikova TD, Menegon A, Roncaglia P, Colciago G, Russo G, Carninci P, Pezzoli G, Gainetdinov RR, Gustincich S, Dityatev A, Broccoli V. Direct generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature. 2011;476(7359):224–27. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [PMID:21725324] http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas M. Role of transcription factors in cell replacement therapies for neurodegenerative conditions. Regen Med. 2010;5(3):441–50. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.17. [PMID:20455654] http://dx.doi.org/10.2217/rme.10.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [PMID:16904174] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loane DJ, Faden AI. Neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury: translational challenges and emerging therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(12):596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.005. [PMID:21035878] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood WG, Eckert GP, Igbavboa U, Müller WE. Statins and neuroprotection: a prescription to move the field forward. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1199:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05359.x. [PMID:20633110] http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson-Fuhrhop KM, Cramer SC. Genetic influences on neural plasticity. PM R. 2010;2(12 Suppl 2):S227–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.09.011. [PMID:21172685] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAllister TW. Genetic factors modulating outcome after neurotrauma. PM R. 2010;2(12 Suppl 2):S241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.10.005. [PMID:21172686] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheets PL, Jackson JO, 2nd, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD, Cummins TR. A Nav1.7 channel mutation associated with hereditary erythromelalgia contributes to neuronal hyperexcitability and displays reduced lidocaine sensitivity. J Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 3):1019–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127027. [PMID:17430993] http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer TZ, Gilmore ES, Estacion M, Eastman E, Taylor S, Melanson M, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. A novel Nav1.7 mutation producing carbamazepine-responsive erythromelalgia. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(6):733–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.21678. [PMID:19557861] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.21678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JS, Zhang L, Dib-Hajj SD, Han C, Tyrrell L, Lin Z, Wang X, Yang Y, Waxman SG. Mexiletine-responsive erythromelalgia due to a new Na(v)1.7 mutation showing use-dependent current fall-off. Exp Neurol. 2009;216(2):383–89. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.012. [PMID:19162012] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendrie HC, Albert MS, Butters MA, Gao S, Knopman DS, Launer LJ, Yaffe K, Cuthbert BN, Edwards E, Wagster MV, Report of the Critical Evaluation Study Committee The NIH Cognitive and Emotional Health Project. Alzheimers Dement. 2006;2(1):12–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.11.004. [PMID:19595852] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raz N, Dahle CL, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Land S. Effects of age, genes, and pulse pressure on executive functions in healthy adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(6):1124–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.015. [PMID:19559505] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leritz EC, Salat DH, Williams VJ, Schnyer DM, Rudolph JL, Lipsitz L, Fischl B, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP. Thickness of the human cerebral cortex is associated with metrics of cerebrovascular health in a normative sample of community dwelling older adults. Neuroimage. 2011;54(4):2659–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.050. [PMID:21035552] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salat DH, Williams VJ, Leritz EC, Schnyer DM, Rudolph JL, Lipsitz LA, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP. Inter-individual variation in blood pressure is associated with regional white matter integrity in generally healthy older adults. Neuroimage. 2012;59(1):181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.033. [PMID:21820060] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavett BE, Stern RA, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC. Mild traumatic brain injury: a risk factor for neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010;2(3):18. doi: 10.1186/alzrt42. [PMID:20587081] http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/alzrt42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peskind ER, Petrie EC, Cross DJ, Pagulayan K, McCraw K, Hoff D, Hart K, Yu CE, Raskind MA, Cook DG, Minoshima S. Cerebrocerebellar hypometabolism associated with repetitive blast exposure mild traumatic brain injury in 12 Iraq war Veterans with persistent post-concussive symptoms. Neuroimage. 2011;54(Suppl 1):S76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.008. [PMID:20385245] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruff RL, Riechers RG, 2nd, Wang XF, Piero T, Ruff SS. A case-control study examining whether neurological deficits and PTSD in combat veterans are related to episodes of mild TBI. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000312. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000312. [PMID:22431700] http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calohan J, Peterson K, Peskind ER, Raskind MA. Prazosin treatment of trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in soldiers deployed in Iraq. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):645–48. doi: 10.1002/jts.20570. [PMID:20931662] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson CE, Taylor FB, McFall ME, Barnes RF, Raskind MA. Nonnightmare distressed awakenings in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: response to prazosin. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):417–20. doi: 10.1002/jts.20351. [PMID:18720392] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, Kerns RD, Clark ME, Cifu DX. Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: polytrauma clinical triad. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):697–702. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0006. [PMID:20104399] http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2009.01.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark ME, Walker RL, Gironda RJ, Scholten JD. Comparison of pain and emotional symptoms in soldiers with polytrauma: unique aspects of blast exposure. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):447–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00590.x. [PMID:19416436] http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, Begley AE, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Zmuda MD, Bhalla R, Meltzer CC, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Becker JT. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(6):587–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [PMID:15184238] http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, Aizenstein HJ, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, 3rd, DeKosky ST, Becker JT. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):345–57. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/mabutters. [PMID:18979948] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Motl RW, McAuley E. Physical activity, disability, and quality of life in older adults. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(2):299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.12.006. [PMID:20494278] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu SC, Leu SY, Li CY. Incidence of and predictors for chronic disability in activities of daily living among older people in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(9):1082–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05231.x. [PMID:10484250] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Netz Y, Wu MJ, Becker BJ, Tenenbaum G. Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(2):272–84. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272. [PMID:16029091] http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins EG, Fehr L, Bammert C, O’Connell S, Laghi F, Hanson K, Hagarty E, Langbein WE. Effect of ventilation-feedback training on endurance and perceived breathlessness during constant work-rate leg-cycle exercise in patients with COPD. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5 Suppl 2):35–44. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.10.0035. [PMID:15074452] http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2003.10.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Possley D, Budiman-Mak E, O’Connell S, Jelinek C, Collins EG. Relationship between depression and functional measures in overweight and obese persons with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(9):1091–98. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.03.0024. [PMID:20437315] http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2009.03.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McAuley E, Konopack JF, Motl RW, Morris KS, Doerksen SE, Rosengren KR. Physical activity and quality of life in older adults: influence of health status and self-efficacy. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(1):99–103. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_14. [PMID:16472044] http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3101_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD005381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005381.pub3. [PMID:18646126] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(2):125–30. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [PMID:12661673] http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, Erickson KI, Scalf P, McAuley E, Cohen NJ, Webb A, Jerome GJ, Marquez DX, Elavsky S. Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(9):3316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400266101. [PMID:14978288] http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0400266101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rojas Vega S, Strüder HK, Vera Wahrmann B, Schmidt A, Bloch W, Hollmann W. Acute BDNF and cortisol response to low intensity exercise and following ramp incremental exercise to exhaustion in humans. Brain Res. 2006;1121(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.105. [PMID:17010953] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandercock GR, Bromley PD, Brodie DA. Effects of exercise on heart rate variability: inferences from meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(3):433–39. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000155388.39002.9d. [PMID:15741842] http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000155388.39002.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Draganski B, Gaser C, Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Büchel C, May A. Temporal and spatial dynamics of brain structure changes during extensive learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26(23):6314–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4628-05.2006. [PMID:16763039] http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4628-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Engvig A, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Moberget T, Sundseth Ø , Larsen VA, Walhovd KB. Memory training impacts short-term changes in aging white matter: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(10):2390–2406. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21370. [PMID:21823209] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voss MW, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, Basak C, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Alves H, Heo S, Szabo AN, White SM, Wójcicki TR, Mailey EL, Gothe N, Olson EA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Plasticity of brain networks in a randomized intervention trial of exercise training in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:32. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00032. [PMID:20890449] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(77):77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [PMID:21471435] http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]