Abstract

Nonsense suppression is a readthrough of premature termination codons. It typically occurs either due to the recognition of stop codons by tRNAs with mutant anticodons, or due to a decrease in the fidelity of translation termination. In the latter case, suppressors usually promote the readthrough of different types of nonsense codons and are thus called omnipotent nonsense suppressors. Omnipotent nonsense suppressors were identified in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in 1960s, and most of subsequent studies were performed in this model organism. Initially, omnipotent suppressors were localized by genetic analysis to different protein- and RNA-encoding genes, mostly the components of translational machinery. Later, nonsense suppression was found to be caused not only by genomic mutations, but also by epigenetic elements, prions. Prions are self-perpetuating protein conformations usually manifested by infectious protein aggregates. Modulation of translational accuracy by prions reflects changes in the activity of their structural proteins involved in different aspects of protein synthesis. Overall, nonsense suppression can be seen as a “phenotypic mirror” of events affecting the accuracy of the translational machine. However, the range of proteins participating in the modulation of translation termination fidelity is not fully elucidated. Recently, the list has been expanded significantly by findings that revealed a number of weak genetic and epigenetic nonsense suppressors, the effect of which can be detected only in specific genetic backgrounds. This review summarizes the data on the nonsense suppressors decreasing the fidelity of translation termination in S. cerevisiae, and discusses the functional significance of the modulation of translational accuracy.

Keywords: prion, amyloid, yeast, nonsense suppression, translation, SUP35, SUP45, ribosome, translation termination

Abbreviations

- eEF

eukaryotic translation elongation factor

- eRF

eukaryotic translation release factor

- G418

geneticin, aminoglycoside antibiotic

- NMD

Nonsense-Mediated Decay

- ORF

open reading frame

- SNM

suppressor of nonsense mutation

- t-SNARE

(target membrane) soluble N-ethylmaleimide attachment protein receptor protein

Introduction

Efficiency and precision of the three major templated processes in the cell, replication, transcription, and translation, are determined by the balance of ambiguity (error frequency) and repair (efficiency of proofreading). In translation, templating errors result either from reading of codons by non-cognate tRNAs, or from recognition of codons by cognate tRNAs charged with wrong amino acids. Attachment of non-cognate mRNAs to codons may be reversed by the mechanism of ribosomal correction with elongation factor EF-Tu in prokaryotes, and with its ortholog eEF-1A in eukaryotes (for a review see refs. 1–2). Also, correction of tRNA mis-acylation was described for several aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (for a review see ref. 3). When correction does not occur, resulting errors can be divided into two major categories: (i) when sense codons are mistranslated into other sense codons, leading to a single amino acid substitution, or (ii) when stop codons are readthrough as sense ones, leading to an extension of the peptide. Also, mistranslation of both sense and nonsense codons may involve a shift of the reading frame.

The genetic approach to the analysis of mistranslation is to obtain reporters with missense, frameshift and nonsense mutations, and then identify suppressors called, respectively, missense-, frameshift- and nonsense-suppressors, that would allow to detect mistranslation events. In general, nonsense suppression is easier to detect and measure, so it has been studied in more detail than other two types of suppression.

The study of nonsense suppression began in the 1960s with the discovery of nonsense mutations and suppressors of nonsense mutations (SNMs) in the classical Escherichia coli – bacteriophage T4 system,4,5 followed by the identification of the three nonsense codons, UAG, UAA and UGA,6,7 the existence of which was predicted in the work of Francis Crick with co-authors in 1961.8 Saccharomyces cerevisiae was the first eukaryote, in which SNMs were identified,9,10 (for a review see ref. 11). SNMs are subdivided into two major classes: codon-specific that suppress only one of the three nonsense codons, and omnipotent that affect readthrough of all three nonsenses.

Codon-specific nonsense suppression has been found to be due to mutations in genes encoding different tRNAs. Usually the anticodon is mutated to an anti-stop, but occasionally changes are outside of the anti-codon.12-15 Also, codon-specific nonsense suppression may be caused by amplification of genes encoding tRNAs that are near-cognate to stop codons.16,17 Such SNMs are called “multicopy” suppressors. In this case, multicopy suppression apparently reflects a lower-level physiological nonsense readthrough.18 For a detailed review of codon-specific SNMs see refs 11, 19.

The story of omnipotent nonsense suppressors in S. cerevisiae started in 1964 with the discovery of the sup1 (s1) and sup2 (s2) recessive SNMs that were proposed to be mutations in translation termination factors.20-22 A very simple phenotypic assay for the selection of omnipotent nonsense suppressors relied on the simultaneous readthrough of different nonsenses in the same strain, e.g., ade1–14 (UGA) and his7–1 (UAA). Almost all of these double prototroph revertants bore a recessive mutation in either one or the other of the two genes. These SNMs, currently known as sup45 and sup35, were also identified in several other labs as omnipotent suppressors, as well as frameshift suppressors or allosuppressors that enhance suppressor phenotypes of codon-specific nonsense suppressors.13,23-27 Later, it was shown that sup45 and sup35 are the mutant alleles of indispensable genes, SUP45 and SUP35, that indeed encode release factors, eRF1 and eRF3, respectively.28-30 Discovery of release factor SNMs indicated that nonsense suppression depends on the outcome of the competition for nonsense codons between tRNAs and translation release factors.

While initial evidence could suggest that omnipotent nonsense suppression was caused directly by the loss of function of release factors, further studies revealed a more complex interplay of tRNAs, translation factors, and ribosomes during the recognition of stop codons. Indeed, omnipotent suppressors were soon identified in other components of translation machinery, including ribosomal components, and in other translation-coupled proteins. Furthermore, in many cases mutations in the same gene could manifest either as suppressors, or as antisuppressors that inhibited the readthough caused by other nonsense suppressors. Adding another level of complexity, numerous studies reported that readthrough of termination codons in S. cerevisiae could be caused by mutations or multicopy expression of genes that were not directly related to translation. Finally, a unique subgroup of SNMs in S. cerevisiae was associated with epigenetic elements – prions, i.e., self-perpetuating conformations of proteins that are prone to form infectious aggregates. In this review we summarize the data on these heterogenous groups of nonsense suppressors, and attempt to draw a global picture of the control of the fidelity of translational termination and discuss its physiological role.

Genetic Modulators of the Frequency of Translational Readthrough

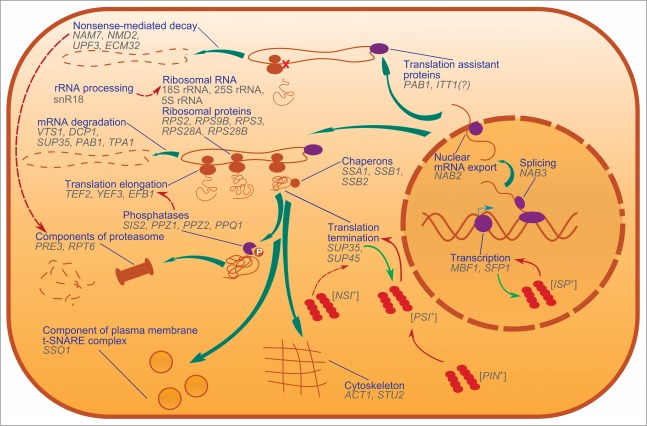

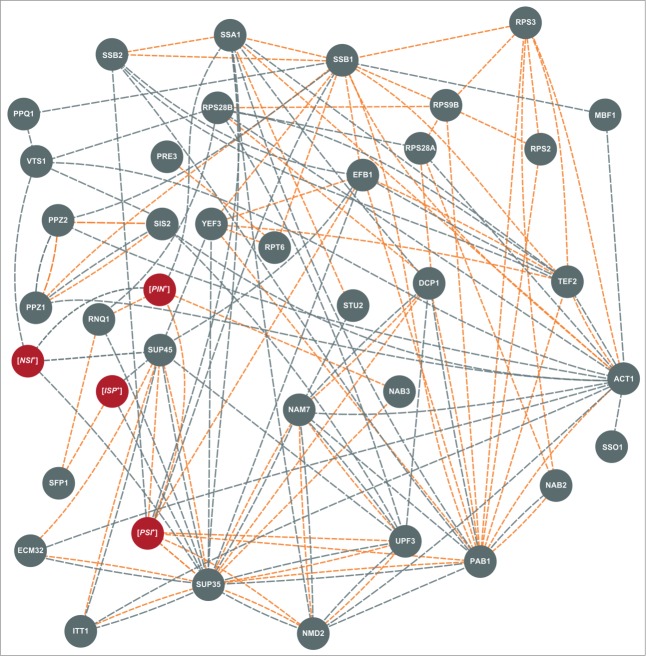

Here we discuss genes, for which there is evidence for nonsense suppressor phenotypes due to mutations or changes in expression level. Table 1 lists these suppressor genes with the information on mutations and amplification effects. Figure 1 presents a graphical scheme illustrating the involvement of proteins with different cellular functions in the modulation of translational readthrough. The map of the genetic and physical interactions between these genes or their products is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Genes that affect nonsense readthrough in S. cerevisiae

| Gene* | Protein | Function** | Effect on nonsense readthrough*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACT1 | Act1 | Actin | Nonsense suppressor96 |

| DCP1 | Dcp1 | Component of P-bodies; subunit of the de-capping enzyme complex | Nonsense suppressor76 |

| ECM32 (MTT1) | Mtt1 | Upf1-like helicase | Multicopy nonsense suppressor66 |

| EFB1 (TEF5) | Efb1 | Alpha subunit of translation elongation factor eEF1B; nucleotide exchange factor for eEF1A | Antisuppressor;49 multicopy antisuppressor50,51 |

| ITT1 | Itt1 | Interacts with translation release factors eRF1 and eRF3 | Multicopy omnipotent nonsense suppressor80 |

| MBF1 (SUF13) | Mbf1 | Transcriptional co-activator | Nonsense suppressor25,37 |

| NAB2 | Nab2 | RNA-binding protein; required for nuclear mRNA export | Weak multicopy suppressor of ade1–1479 |

| NAB3 | Nab3 | RNA-binding protein required for termination of non-poly-A transcripts and efficient splicing | Weak multicopy suppressor of ade1–1479 |

| NAM7 (SUP113, UPF1, MOF4, IFS2) | Nam7 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase; component of nonsense mediated mRNA decay pathway | Recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressor58-63 |

| NMD2 (SUP111, UPF2, IFS1) | Nmd2 | Component of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway; involved in telomere maintenance | Weak recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressor58-61,57 |

| PAB1 | Pab1 | Poly-A binding protein involved in translation and polyA tail length control | Multicopy antisuppressor67 |

| PPQ1 | Ppq1 | Serine/threonine PP1 family phosphatase | Allosuppressor81,82 |

| PPZ1 | Ppz1 | Serine/threonine protein phosphatase Z | Nonsense suppressor;84 multicopy antisuppressor85 |

| PPZ2 | Ppz2 | Serine/threonine protein phosphatase Z, isoform of Ppz1p | Allosuppressor86 |

| PRE3 (CRL21) | Pre3 | Beta 1 subunit of the 20S proteasome | Nonsense suppressor hypersensitive to hygromycin B87-89 |

| RPS2 (SUP44; SUP138) | Rps2 | Protein of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit | Dominant omnipotent nonsense suppressor33,150 |

| RPS28A and RPS28B | Rps28 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit | Nonsense suppressor and antisuppressor35,36 |

| RPS3 (SUF14) | Rps3 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit | Nonsense suppressor25,37 |

| RPS9B (SUP46) | Rps9b | Protein of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit | Dominant omnipotent nonsense suppressor34,31 |

| RPT6 (CRL3) | Rpt6 | ATPase of the 19S regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome | Nonsense suppressor hypersensitive to hygromycin B87-89 |

| SFP1 | Sfp1 | Transcription factor | Weak allosuppresoor;93 antisuppressor when in the [ISP+] prion form92 |

| SIS2 (HAL3) | Sis2 | Negative regulatory subunit of protein phosphotaze Z | Antisuppressor and multicopy allosuppressor85 |

| SSA1 | Ssa1 | Heat-inducible Hsp70 chaperone | Increases nonsense readthrough in [PSI+] cells when overexpressed152 |

| SSB1, SSB2 | Ssb | Ribosome-associated Hsp70 chaperone | Multicopy antisuppressor (SSB1);50 double deletion allosuppressor for [PSI+]151 |

| SSO1 | Sso1 | Plasma membrane t-SNARE; involved in fusion of secretory vesicles at the plasma membrane and in vesicle fusion during sporulation | Multicopy suppressor100 |

| STU2 | Stu2 | Microtubule-associated protein; spindle body component controlling microtubule dynamics | Multicopy suppressor100 |

| SUP35 (s2, SUP2, SUP36, SAL3, SUF12, SUPP) | Sup35 | eRF3 translational release factor | Recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressor and allosuppressor20,13,23-26 |

| SUP45 (s1, SUP1, SUP47, SAL4, SUPQ) | Sup45 | eRF1 translational release factor | Recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressor, allosuppressor20,13,23,24,26 |

| TEF2 | Tef2 | Translation elongation factor eEF1A | Omnipotent nonsense suppressor46,47 |

| TPA1 | Tpa1 | Poly-A binding protein involved in polyA tail length control | Nonsense suppressor73 |

| UPF3 (SUP112) | Upf3 | Component of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway; involved in telomere maintenance | Weak recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressor58-60,57 |

| VTS1 | Vts1 | RNA-binding protein; stimulates deadenylation-dependent mRNA degradation | Weak omnipotent multicopy nonsense suppressor77 |

| YEF3 (TEF3) | Yef3 | Gamma subunit of translational elongation factor eEF1B; nucleotide exchange factor for eEF1A | Multicopy antisuppressor51 |

| snR18 (SNR18) | — | snoRNA U18 | Multicopy antisuppressor50 |

| 18S rRNA (RDN18–1 and RDN18–2) | — | 18S rRNA | Nonsense suppressor and antisuppressor38-41 |

| 25S rRNA (RDN25–1 and RDN25–2) | — | 25S rRNA | Nonsense suppressor42 |

| 5S rRNA | — | 5S rRNA | Nonsense suppressor and antisuppressor45 |

Note: *Alternative names are shown in the brackets; **See “Saccharomyces Genome Database” (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) and references therein for the functional role of gene products; ***Unless otherwise stated the phenotypes are caused by mutations or gene disruptions.

Figure 1.

Nonsense suppressors in S. cerevisiae, and cellular processes in which SNMs are implicated. Genes that are linked to nonsense suppressors are shown and grouped by cellular functions of their products. Thick teal arrows show the lifecycle of proteins, from transcription to degradation. Red arrows show influence of one process or prion on another. Light-green arrows show conversion of soluble proteins into prion conformations. Dashed arrows are shown in the cases if the mechanisms of an influence are not fully elucidated. Dark blue lines connect processes and their graphical representations.

Modulators of translation termination directly involved in translation

Beyond SUP35 and SUP45 coding for the translation termination factors discussed above, this group includes genes encoding ribosomal components, both ribosomal proteins and rRNAs, and translation factors.

Consistent with the key role of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit in the decoding process, effects on translational accuracy have been reported for several ribosomal proteins of the 40S subunit. Two dominant omnipotent SNMs, SUP44 and SUP46, were found to be mutant alleles of the genes RPS2 and RPS9 encoding the homologs of bacterial “ribosomal ambiguity” proteins, ram's, S4 and S5, respectively.31-34 Also, an array of mutations modulating efficiency of translation termination was isolated in the gene for the Rps28 protein, a homolog of another bacterial ram protein, S12. Interestingly, Rps28 can alter translational accuracy in both directions: some of RPS28 mutations were SNMs, and some had an antisuppressor effect toward other nonsense suppressors, including SUP44 and SUP46.35,36 Altogether, these findings were interpreted as the existence of a ribosomal decoding center that is conserved from bacteria to yeast. Finally, suf14, which had been discovered as the +1 frameshift suppressor25 but later found to be able to suppress the trp1–1 nonsense mutation, is an allele of RPS3.37

The second and very interesting subgroup of translation-coupled omnipotent SNMs are mutant rRNAs of both small and large ribosomal subunits. Consistent with structural evidence that the 18S rRNA occupies the accuracy center of the ribosome in the 40S subunit, mutations affecting ambiguity of translation termination are particularly abundant in 18S rRNA, where such mutations were found in helices 18, 27, 34 and 44.38-41 Noteworthy, both suppressor and antisuppressor mutations were found in 18S rRNA. The most striking illustration of how this rRNA can fine-tune translation termination was obtained for the residue C1054 in helix 34: while substituting this residue to A or G led to a dominant nonsense suppressor phenotype, the C1054T mutation caused antisuppression.39

SNMs were also detected in both rRNAs of the large ribosomal subunit. In the 25S rRNA, nonsense suppression was linked to the conserved sarcin / ricin domain.42 This domain is involved in the decoding through binding to elongation factors43 (see elongation factor SNMs below), as well as to residues that fine-tune the structure of the A-site region of the large subunit essential for the correct aa-tRNA accommodation.44 In the saturating mutagenesis study of the entire 5S rRNA, 44 and 5 out of 239 mutations had nonsense suppressor and antisuppressor phenotypes, respectively. SNMs were clustered in several regions of the 5S rRNA molecule and, strikingly, their proportion was dramatically increased for evolutionary conserved residues.45 The authors proposed that 5S rRNA affects translational accuracy by transducing information between different functional centers of the ribosome.

Translation elongation factors also affect translational readthrough. Omnipotent SNMs were obtained in the S. cerevisiae TEF2, one of the two genes encoding the translation elongation factor eEF1A.46 eEF1A plays a central role in the delivery of aa-tRNA to the ribosome and, after the GTP hydrolysis, leaves aa-tRNA docked in the ribosomal A-site, where decoding events occur for both elongation and termination. The mutations were clustered in two regions of the Tef2 protein that are involved, respectively, in the interaction with aa-tRNA and GTP-binding, suggesting two distinct mechanisms for the modulation of translational accuracy by Tef2. Disruption of TEF2 that left only one eEF1A-encoding gene, TEF1, and thus led to the reduction of eEF1A levels, caused antisuppression, and not only in S. cerevisiae,47 but also in Podospora anserina.48 A feasible explanation for these data is that reduction in eEF1A allowed for a more efficient competition from termination factors. This explanation was supported by findings that mutations inactivating the nucleotide exchange factor for eEF1A, the eEFB1α protein encoded by EFB1, also had an antisuppressor effect.49 A seemingly contradictory result, that overexpression of EFB1 also causes antisuppression,50,51 is apparently because the antisuppressor effect of EFB1 overexpression is caused not by the eEFB1α encoded by the EFB1 ORF, but by the EFB1 intron-encoded snoRNA, snR18, that guides the 2’-O-methylation of the 25S rRNA. In this case control of translation termination fidelity possibly occurs via modification of rRNAs by the snoRNA regulatory system.50 Valouev et al. (2009) proposed another interesting explanation for the multicopy antisuppressor phenotype of eEFB1α, and also of another subunit of eEFB1, eEFB1γ encoded by YEF3. They hypothesized that eEFB1 has an auxiliary function as a nucleotide exchange factor for the translation termination factor eRF3 encoded by SUP35, so excess eEFB1α and eEFB1γ promote the activity of Sup35 and, consequently improve the efficiency of translation termination.51 This hypothesis is further supported by the homology of eEF1A and the C-terminal part of Sup35.

The fact that SNMs were found in most ribosomal components and in translation factors is not surprising. Ribosome, as a protein-RNA complex guiding the decoding process, has a great potency for the fine-tuning of translational fidelity, not only increasing but also decreasing the frequency of translational errors. Indeed, there is an obvious link between SNMs and the decoding center of the ribosome and, specifically, the A-site, where the choice between elongation and termination is made. For example, all known SNMs for ribosomal proteins are in the small subunit. And among elongation factors, termination accuracy is affected by the ones that are implicated in events at the A-site. Noteworthy, while some studies raise the possibility of nonsense recognition as an outcome of a competition between elongation and termination, many mutations in different ribosomal components and translation factors have similar effects on the accuracy of translation termination and on the frequency of other translational errors, such as framesifting and mistranslation of sense codons, indicative of a global effect on the accuracy of decoding.52 This supports the idea that in some cases nonsense suppression could reflect the general inaccuracy of the decoding site. Beyond the decoding site, factors affecting the overall accuracy of translation do not always cause nonsense readthrough. For example, a dramatic effect on the accuracy of sense codon recognition without a nonsense suppressor phenotype was reported for Rpl39,53 a large subunit protein that is located in the peptide exit channel, where it affects both the post-translational signaling events and the speed of the peptidyl transferase reaction, which is downstream of the critical steps of the codon recognition essential for the nonsense readthrough.54,55

RNA-binding proteins involved in mRNA processing

This group includes proteins that are either directly involved in translation, or affect it through directing mRNA to active translation, storage or degradation. While many of them are known to interact with Sup35 and/or Sup45, the mechanisms of the modulation of the efficiency of translation termination are largely unclear.

The NMD (Nonsense-Mediated Decay) mRNA degradation pathway is tightly coupled with translation, and its components interact with both eRF1 and eRF3.56,57 The mutant alleles of NAM7 (UPF1), NMD2 (UPF2), and UPF3 encoding the components of the surveillance complex implicated in NMD were initially isolated as weak recessive omnipotent nonsense suppressors sup113, sup111 and sup112, correspondingly.58 The relationship between these suppressors and NMD genes was proven only in 2005,59 but meanwhile several studies directly tested the effects of known NMD components on the fidelity of translation termination, and nonsense suppression was detected in the upf1-Δ, upf2-Δ and upf3-Δ strains.60-63,57 While stabilization of nonsense-containing transcripts in NMD-deficient strains could be the simplest explanation for these phenotypes, experimental evidence indicates alternative explanations implying an interaction of NMD components with translation termination factors. Indeed, nonsense suppression in the presence of disruptions or mutations in UPFs was independent on their effects on mRNA turnover.62,63,57 Also, there is evidence that Upf1 affects the mode of translation of stop codons: decoding of premature stop codons by the release factor is aberrant, but only in the presence of Upf1.64 On the other hand, it is feasible that inefficient NMD is a contributing factor to nonsense suppressor phenotypes of some sup35 and sup45 mutants: accumulation of nonsense-containing mRNAs was reported for several sup45 SNMs.65

In addition to the well-known components of the surveillance complex, Ecm32 (Mtt1), an Upf1-like helicase that also interacts with translation termination factors, was shown to cause nonsense suppression when overexpressed.66

Another Sup35-binding protein affecting the accuracy of translation termination is the poly-A binding protein encoded by the PAB1 gene: its overexpression antisuppresses nonsense-suppression caused by Sup35 mutations, as well as reduces the readthrough of different stop codons in reporter assays.67 The understanding of how Pab1 promotes translational accuracy is complicated by the fact that Pab1 is a multifunctional protein involved in both translation and control of mRNA stability, and the interaction of Pab1 with Sup35 is important for different functions of Pab1. On one hand, Pab1 interacts with the initiation factor eIF4G promoting the formation of a closed-loop structure between the mRNA cap and poly-A tail, essential for efficient translation. This process is translation-dependent and requires the retention of Sup35 with the Pab1 complex after termination.68 Thus, the effect of Pab1 on termination efficiency could be through translation. Indeed, disruption of the ribosomal protein Rpl39, which is critical for translational accuracy,53 rescues the lethality of pab1-Δ.69 Furthermore, a recent finding that NMD depends on a complex competition of Pab1 and Upf1 for binding with Sup35,70 opens the possibility that NMD could be involved in Pab1-associated nonsense suppression. On the other hand, Pab1 controls mRNA stability through the conventional de-adenylation / de-capping pathway, and mutations in Sup35 have been shown to interfere with mRNA de-adenylation and degradation.71,72 This indicates that termination accuracy could be controlled through de-adenylation. The possible role in this for proteins specifically interacting with poly-A and implicated in the control of its length is further underscored by the finding that the disruption of the TPA1 gene, which encodes a protein interacting with Pab1, Sup35, Sup45 and de-adenylation enzymes, is also an SNM.73

P-bodies and stress granules are the RNP complexes involved in mRNA storage and degradation. They encompass multiple components of the translational machinery and occasionally incorporate eRF1 and eRF3,74,75 although association with release factors is not obligatory. Both disruption and point mutations in the DCP1 gene, which encodes the P-body marker Dcp1 involved in mRNA de-capping prior to degradation, increase the stop codon readthrough and suppress the ade2–1 nonsense mutation.76 An interaction between Dcp1 and Sup35 was reported in co-immunoprecipitation experiments, so this interaction may be either direct, or it is possible that the effect of Dcp1 on translational accuracy is mediated by Pab1, with which Dcp1 also interacts.

Expanding the involvement of mRNA degradation machinery in nonsense readthrough, we have recently made an interesting observation that VTS1, a gene that encodes a protein essential for the degradation of the normal transcripts containing a specific Signal Recognition Element (SRE) hairpin loop, can cause weak omnipotent nonsense suppression when expressed from a multicopy plasmid.77 The suppression was observed in a system where the SUP35 chromosomal copy was deleted and replaced by a plasmid expressing a chimeric Aβ-Sup35 protein, which acts as cryptic nonsense suppressor.78

Also, in the same suppression-sensitive background, we found that essential genes NAB2 and NAB3 act as multicopy allosuppressors of the ade1–14(UGA) nonsense mutation.79 NAB2 encodes a protein involved in nuclear mRNA export, and NAB3 is an RNA-binding protein required for efficient mRNA splicing and maturation. Thus, readthrough of termination codons is caused not only by mRNA decay proteins, but also by RNA-binding proteins with a wide spectrum of functions regulating mRNA production and delivery to the cytoplasm. We hope that exact molecular mechanisms for the Vts1, Nab2 and Nab3 action will be elucidated in the nearest future, but some hints can be obtained even now, from interactome analyses. As can be seen from Figure 2, VTS1, NAB2 and NAB3 each interact with several previously identified SNMs that may mediate their effects on nonsense suppression.

Figure 2.

Interaction network of the genes and factors affecting nonsense readthrough in S. cerevisiae. Genetic factors are indicated as gray circles, epigenetic – as red circles. Different lines indicate different types of interactions between suppressors: physical interactions are shown in orange, genetic – in gray. The data on interactions were obtained and combined from “BioGrid” (http://thebiogrid.org/), “GeneMANIA” (http://genemania.org/), “Saccharomyces Genome Database” (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) and, in some cases, from papers cited in this review.

The last SNM we include in this group is ITT1, which causes omnipotent nonsense suppression when overexpressed.80 The function of the protein is not known, but it interacts with two known SNMs, Sup35 and Sup45.

Phosphatases

The first indication of the influence of a gene encoding a protein phosphatase on nonsense suppression was obtained from the analysis of recessive allosuppressors, which enhanced nonsense suppression in the presence of the sup35–2 and sup45–4 alleles.81 One such allosuppressor, sal6, was mapped to the PPQ1 gene encoding a protein phosphatase regulating the mating response.82 While the exact target through which Ppq1 affects translational accuracy was not established, there is evidence for its involvement in the regulation of protein synthesis: disruption of PPQ1 results in the reduced rate of protein synthesis and hypersensitivity to protein synthesis inhibitors.83

More recently, several studies implicated the protein phosphatase Z in the control of the accuracy of translational termination. Deletion of one of the genes for this phosphatase, PPZ1, was shown to increase readthrough of termination codons.84 Conversely, overexpression of PPZ1 causes antisuppression.85 Deletion and overexpression of SIS2 (HAL3), which is a negative regulatory subunit of Ppz1p, cause, respectively, antisuppression and allosuppression.85 Finally, mutational inactivation of PPZ2, the PPZ1 paralogue, causes allosuppression in the presence of the Sup35-based prion [PSI+].86 It has been proposed that Ppz1 affects translational fidelity through its target, translation elongation factor eEFB1α (see the Modulators of translation termination directly involved in translation section).85

Components of the protein folding machinery and proteasome

In 1988 McCusker and Haber isolated a set of cycloheximide-resistant mutants that fall into 22 complementation groups. These mutants, called crl (cycloheximide-resistant lethal), had pleiotropic phenotypes similar to those of omnipotent nonsense suppressors, including temperature sensitivity, and suppressed the met13–2 nonsense mutation.87,88 Later, by complementation of their temperature sensitivity, crl3 and crl21 mutants were localized to the RPT6 and PRE3 genes encoding proteasome proteins.89 It is interesting that, similarly to rRNA SNMs, these crl mutants were also sensitive to different aminoglycoside translational inhibitors, such as hygromycin B and G418. Other mutations in the 20S proteosomal components that were isolated in this study, pre1, pre2, pre3 and pre4,89 also had pleiotropic phenotypes observed for the crl mutants, suggesting that these genes could be involved in the modulation of translational ambiguity. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no follow-up studies that would explain the role of the proteasome in translational ambiguity. However, recent findings link nonsense decoding and proteasomal protein degradation by showing that the NMD system facilitates the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of truncated peptides synthesized from templates containing premature stop codons.90,91 Thus, deficiencies in proteasome system could either specifically stabilize partially functional truncated proteins or even interfere with the functioning of NMD and translation termination.

Several studies also report that nonsense suppression and efficiency of stop codon readthrough is regulated by the chaperone machinery and, specifically, by chaperones of the Hsp70 family. For example, SSB1 that encodes the Ssb Hsp70 chaperone involved in the co-translational protein folding decreases detectable nonsense readthrough when overexpressed,50 whereas a double deletion of SSB1 and SSB2, the second Ssb-encoding gene, increases nonsense readthrough in the presence of the [PSI+] prion.151 Among the Ssa Hsp70-encoding genes, overexpression of SSA1 increases nonsense readthrough in [PSI+] cells.152 While these chaperones may work through the folding and modulation of stability of proteins with stop codons recoded into sense codons, it is also feasible that they change availability of the translation termination factor, Sup35, by affecting its recruitment into the [PSI+] prion,151,152 or, in the case of Ssb, by directly affecting the decoding process on the ribosome.50

Transcription factors

This group currently includes two genes, SFP1 and MBF1. The protein product of the SFP1 gene, Sfp1, is capable of forming the [ISP+] prion that has an antisuppressor effect.92 However, deletion of SFP1 causes an opposite effect, a weak allosuppression,93 which is observed in the strains bearing a combination of specific SUP35 and SUP45 mutant alleles.94

MBF1, a DNA replication stress-dependent transcriptional co-activator, was initially isolated as the suf13 +1 frameshift suppressor,25 and later found to suppress the trp1–1 nonsense mutation.37

However, the number of transcription factors affecting nonsense suppression, is likely much higher. Indeed, we recently found that the genes encoding transcriptional regulators ABF1, GLN3, FKH2, MCM1, MOT3, and REB1 can act as very weak multicopy suppressors. Their effect on translational accuracy needs further investigation, since it was detected only for the relatively efficiently suppressed ade1–14(UGA) codon. Also, suppressor effect of these transcription factors was observed only in the genetic background that was made readthrough-prone by introducing a cryptic nonsense suppressor:95 like in the study describing the discovery of the VTS1, NAB2 and NAB3 multicopy suppressors (see the RNA-binding proteins involved in mRNA processing section), this was done by substituting Aβ-Sup35 for the wild type Sup35.

Cytoskeleton and transport

Finally, SNMs were linked to changes in both actin and microtubular cytoskeletons. Due to yet unclear mechanisms, several act1 mutations cause nonsense suppression.96 The authors hypothesized that the effect is mediated by elongation factors and, specifically, by eEF1A. The alternative possibility is that the suppression is mediated by Sup35, which is known to interact with multiple components of the actin cytoskeleton, especially in the context of the formation of the Sup35-based prion [PSI+].97-99,153 Also, a multicopy SNM phenotype was reported for STU2, a gene encoding a component of the spindle body controlling microtubule dynamics, and for SSO1, which codes for a component of the plasma membrane t-SNARE complex involved in the fusion of secretory vesicles to the membrane.100

In summary, currently the list of genes affecting readthrough of termination codons includes 37 names (Table 1). As can be seen on the map in Figure 2, many of these genes interact. Moreover, there are no genes in this group that don't have genetic interactions with other group members. This suggests that, although SNM genes curate extremely different cellular processes, they are involved in a specific sub-interactome, in which four genes, SUP35, SUP45, PAB1 and ACT1, appear to be the “hubs” connecting most of its members (Figure 2). Thus, SNMs involved in different cellular processes may realize their influence on translation via interaction with these four major translation-coupled SNMs. Alternatively it is possible that modulation of translation by these key proteins allowed the discovery of an array of cellular functions influencing translational readthrough. Indeed, the fact that SNM genes do encode proteins involved in all stages of the expression of genetic information, from transcription, to splicing and mRNA export from the nucleus, to mRNA modification, to translation, and finally, to mRNA degradation (Figure 1), certainly underscores a multi-level control of translational accuracy.

It is also noteworthy that recently several novel SNMs were uncovered in the presence of mutations in other SNM genes, such as SUP35 and SUP45. All these new SNMs are very weak suppressors, often allosuppressors. So the pre-existing mutations, which can be cryptic themselves, create an environment, essential for the initial selection of such weak suppressors and allosuppressors. This suggests that genetic background may be crucial for the detection of factors that fine-tune the frequency of the readthrough of nonsense codons. Considering that most studies have not been conducted in such suppression-sensitive backgrounds, it is likely that only a small fraction of weak nonsense suppressors, allosuppressors or antisuppressors were identified to date.

Epigenetic Modifiers of Translational Readthrough Efficiency

Along with a number of genes that affect nonsense suppression in the mutated or overexpressed state, a family of epigenetic elements modulating this process has also been described (Table 2, Figure 2). The first epigenetic modulator of nonsense suppression, [PSI+], was discovered in 1965 as the allosuppressor of the weak suppressor tRNA.101,102 Its molecular nature remained mysterious for a long time, until it was explained within the framework of the prion hypothesis by Reed B. Wickner,103,104 based on a series of studies linking [PSI+] to Sup35, and eventually demonstrating that [PSI+] is a prion form of Sup35.105-109 The nonsense suppressor phenotype of [PSI+] is a result of partial inactivation of Sup35 release factor, due to its incorporation in the [PSI+] prion aggregate.

Table 2.

Epigenetic modifiers of nonsense suppression in S. cerevisiae

| Prion | Structural protein | Function of structural protein | Prion phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| [PSI+] | Sup35 | eRF3 translational release factor | Dominant omnipotent suppressor101,105-109 |

| [PIN+] | Rnq1 | Unknown | Enhances the de novo appearance of [PSI+]110-113 |

| [ISP+] | Sfp1 | Transcription factor | Antisuppressor92,121 |

| [NSI+]* | Unknown | Unknown | Weak dominant omnipotent suppressor123,77 |

Note: *Prion-like non-chromosomal factor.

The second prion identified in our studies, [PIN+], also modulates translational readthrough, although this influence is indirect. This prion was initially discovered as the non-chromosomal determinant essential for the de novo induction of [PSI+].110,111 Later [PIN+] was linked to the protein with an unknown function encoded by the RNQ1 gene and biochemically and genetically proven to be able to take on a prion conformation.112,113 Both [PSI+] and [PIN+] were recently detected in wild yeast populations, with [PIN+] occurring considerably more frequently than [PSI+] and present in all wild [PSI+] strains.114,115 The demonstration that [PSI+] can act as a phenotypic modifier for an array of traits in various genetic backgrounds led to a hypothesis that [PSI+] has an adaptive role revealing hidden genetic variability and thus facilitating the survival and evolvability of wild yeast populations in changing environmental conditions.116,117,115 In this case, an adaptive role of [PIN+] could be in the induction of [PSI+] (as well as of other prions). However, the hypothesis of the adaptive role of [PSI+] is challenged on the grounds that the frequency of [PSI+] strains in nature is too low for a non-harmful trait,118 that at least some [PSI+] variants are notably detrimental or even lethal to yeast cells,119 and that the existing intraspecies barriers for [PSI+] transmission manifest an adaptation to limit the spread of the prion.120

Two novel epigenetic modulators of nonsense suppression were recently discovered in our laboratory. The first is the non-chromosomal determinant [ISP+], an antisuppressor detectable in the background of some SUP35 and SUP45 mutations.121 This determinant was demonstrated to be the prion form of Sfp1,92 which was discussed above (see the Transcription factors section). The most interesting features of [ISP+] are the very high frequency of its spontaneous de novo appearance, the nuclear localization of the prion, and that this prion does not lead to the Sfp1-deficient phenotypes, but rather enhances the phenotype of wild type Sfp1.92 The latter obviously indicates that Sfp1 retains its activity upon acquiring its prion conformation. One possibility is that the prion-related aggregation allows for the concentration of Sfp1 at the site of its activity. Sfp1 regulates the transcription of ∼10% of yeast genes, so it is possible that the effect of [ISP+] is due to global changes in the transcriptome / proteome. Alternatively, according to recent findings, the levels of SUP35 mRNA and Sup35 protein are increased in [ISP+] cells, which could provide a more direct explanation to the antisuppression and the growth and survival advantages of the [ISP+] prion in strains with insufficient levels and/or activity of translation termination factors.122

The other non-chromosomal determinant affecting nonsense suppression is [NSI+]. This determinant is a weak omnipotent nonsense suppressor, which also affects vegetative growth.123,77,78 The structural gene for [NSI+] has not yet been found, but [NSI+] is very similar to other known yeast prions in many aspects. Indeed, [NSI+] is characterized by dominant non-Mendelian inheritance and cytoplasmic infectivity, which has been proven both by cytoduction and protein transformation. Also, it is curable by a universal anti-prion agent GuHCl, as well as by the deletion or a mutational inactivation of the Hsp104 chaperone, but not by overexpression of HSP104.123 [NSI+] modulates the amounts of the mRNA for several genes, including VTS1,78 (see the RNA-binding proteins involved in mRNA processing section above), thus its determinant appears to be involved in the regulation of transcription or degradation of mRNAs.

Altogether, the system of epigenetic modulators of translational readthrough in yeast contains four members (Table 2), two of which, [PSI+] and [NSI+], act as omnipotent suppressors, the third, [ISP+], as an antisuppressor, and the fourth, [PIN+], as a modulator of prion formation.

The Role of Translation Termination Ambiguity: Sense or Nonsense?

A potentially ambiguous reading of initiation and termination signals is a basis for the regulation of every templated process in the cell, and this is particularly true for the termination of translation. While the first examples of naturally occurring codon-specific nonsense readthrough were found in viruses, now such examples are known for all groups of organisms. With the exception of the UGA codons decoded by selenocystein tRNA in prokaryotes and higher eukaryotes, and UAG codons decoded by the pyrrolysine tRNA in some prokaryotes (for reviews see refs. 124, 125), the readthrough function is usually provided by non-mutant near-cognate host tRNAs potentially capable of nonsense translation. For some tRNAs the propensity for such mistranslation is determined by nucleotide modifications, both in the anticodon and outside of it. An extreme example of an adaptation to the nonsense codon readthrough comes from Euplotes sp. where the recoding of the UGA stop codon into cystein is both due to the presence of a promiscuous tRNACys and the inability of eRF1 to recognize UGA codons.126-128 In mRNAs, the readthrough is facilitated by the context of stop codons that makes them “leaky” (for a review see ref. 19).

In yeast the biological role of an ambiguous reading of nonsense codons remains unclear. However, several examples of natural SNMs and SNM-affected templates have been obtained. The ability to recognize the UAG and UAA stop codons was reported for tRNAGln CAG and CAA, respectively.16-18 There is also and indirect evidence for the readthrough of UAG codons by endogenous tRNATrp, tRNATyr and tRNALys. This evidence comes from sequencing analyses of translational products of nonsense-containing mRNAs.129

The first search for SNM-sensitive yeast ORFs aimed to identify the “leaky” stop codons based on the presence of “provocative” motifs known to promote readthrough in yeast. The idea was based on the finding that the efficiency of translation termination in yeast is determined by a synergistic interplay between sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the stop codon.129,130 In the screen, the stop codon contexts were derived from the CAA UAG CAA UUA context from the Tobacco mosaic virus leading to a 25% readthrough of some ORFs in S. cerevisiae.129-132 The screen revealed that readthrough of a termination codon in the PDE2 gene drastically increases in the presence of the [PSI+] prion and leads to overproduction of cAMP.133 For seven more ORFs the level of stop codon readthrough was at least 2-fold higher in a [PSI+] strain in comparison to [psi−]. Another whole-genome screen performed by Namy and co-authors predicted genes for which expression is likely controlled by non-conventional decoding.134 The authors searched for two adjacent ORFs separated by only one stop codon. Out of 58 ORFs identified by the in silico search, for eight ORFs the basal readthrough level reached 3–25%, and in two of those ORFs, BSC4 and IMP3, the readtrough significantly increased in the presence of [PSI+]. These findings suggest that some yeast ORFs are really read through in the presence of SNMs, including the naturally occurring [PSI+], and that such readthrough can be functional. Taking into consideration that the first screen was based on the predictions for “leaky stop” contexts that were far from being fully elucidated, and the second screen had a strict length filter for ORFs beyond the internal stop, the real number of SNM-sensitive ORFs is likely significantly higher than currently assumed.

It should also be noted that the role of translational ambiguity may be not limited to nonsense readthrough, but also includes other mistranslation events. Indeed, some omnipotent SNMs, including [PSI+], also act as frameshift suppressors.135 Programmed frameshifting in yeast is important not only for Ty1 and Ty3 retrotransposons136 and L-A dsRNA virus,137 but also for the expression of some cellular genes. For example, [PSI+] modulates the cellular content of polyamines through the +1 frameshifting required for the antizyme gene expression.138 In addition, Est1, a subunit of telomerase, and Abp140, an actin filament-binding protein, require the +1 frameshifting for their expression.139,140 Interestingly, a recent study establishes a link between nonsense and frameshift suppression: in Euplotes sp. deficiency of eRF1 in the recognition of stop codons coincides with a dramatic increase in the frequency of frameshifting.141

In addition to specific ORFs requiring nonsense suppression or frameshifting for their translation, pseudogenes, which are considered to be a source of new functional units in gene evolution, are often inactivated with nonsense and frameshift mutations. So, as it had been suggested earlier,142 SNMs, including Sup35 prionization, may play an important role in the activation of either pseudogenes or their fragments exposed to natural selection in the process of gene evolution.

Certainly, studies of nonsense suppressors in yeast may have important implications for treatment of human diseases. Indeed, nonsense mutations constitute up to a third of the disease causing mutations in humans, and selection of chemical compounds promoting the readthrough of these premature stop codons has recently become a promising therapeutic approach for such diseases as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis and several types of cancer. Understanding of the mechanisms of translational readthrough obtained in the course of studies of nonsense suppression is likely to be helpful for drug screens, from the mechanistic details on how particular types of drugs affect specific translational components (e.g., the effects of aminoglycoside antibiotics on rRNA), to the knowledge about the differences of termination at normal and premature stop codons (e.g., in relation to mRNA stability and subsequent translation of the message). Drug discovery can also be facilitated by the well-developed experimental systems used for the selection of nonsense suppressors and measurement of nonsense readthrough (for reviews see refs.143, 144).

Another important aspect is that proteins encoded by genes, for which SNMs have been reported, may not only decrease but also increase translation termination fidelity. Multiple examples are discussed above. For example, SUP35, where mutations or prionization generally cause readthrough, can act as an antisuppressor if its N-terminal prion-forming domain is deleted.145 Also, both suppressor and antisuppressor mutations were reported for the Rps28 ribosomal proten35,36 and 18S rRNA.38,39 Finally, mutations in TEF2 cause omnipotent nonsense suppression,46 whereas its disruption causes antisuppression,47 and for PPZ1 and PPZ2 deletion and overexpression cause allosuppression and antisuppression, respectively.84,86 These findings led to an unexpected discovery: if even a single nucleotide substitution or an adjustment of expression level can significantly increase the efficiency of translation termination, it is not selected to be maintained at the highest possible level. Possibly, the naturally existing gap between the real and maximal efficiencies of translation termination fidelity allows for the realization of the information from the sites of programmed frame-shifting and read through.

Overall, the growing understanding that roles for omnipotent SNMs are important and widespread, and that SNMs form an extensively interacting system, brings us to the question: how is this system regulated? In this respect the differences between genetic and epigenetic SNMs are very interesting. Of course, genetic SNMs typically appear due to mutations that permanently inactivate or change expression levels of the corresponding proteins. In contrast to genetic suppressors, prions arise upon reversible conformational changes. Recent evidence indicates that at least for some prions, switching between prion and non-prion state occurs in response to environmental signals. The most striking example is [MOT3+] that can be induced by ethanol stress and eliminated by hypoxia.146 For [PSI+], appearance is facilitated by various stressful conditions, including oxidative stress and high salt concentrations,147 whereas its loss may be promoted by heat shock, probably due to imbalance in the chaperone system.148 Also, induction of [PSI+] is dependent upon the presence of [PIN+],110,113 which is relatively widespread in natural yeast populations.114,115 Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that promoting each other's formation and elimination is a common feature of yeast prions establishing a network of interrelated conformational switches (for a review see ref. 149). Considering this, epigenetic modulation of the fidelity of translation termination appears to be faster and more flexible than genetic changes. However, genetic SNMs, when they arise not from mutations, may also be the consequences of up- or downregulation of the corresponding genes, and this regulation may be flexible and responsive to various environmental stimuli. Altogether, a dualistic system of the genetic and epigenetic modulators of the translational readthrough in yeast has a great potential to provide the precise tuning of this process. It is clear that naturally polysemantic recognition of nonsenses by the translation machinery is important, but only the tip of the iceberg is currently discovered, and a number of intriguing findings await us along this way.

Disclosure Statement

Authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grant 7 R01 GM070934–06 to I.L.D.), as well as by Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant 14–04–31838 to K.S.A.) and St. Petersburg Government (to A.A.N. and K.S.A.) This work was also funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, project 14.132.21.1324 to A.A.N. The authors acknowledge Saint-Petersburg University for a research grant 1.50.2543.2013 (to A.A.N. and S.G.I.).

References

- 1.Rodnina MV, Gromadski KB, Kothe U, Wieden HJ. Recognition and selection of tRNA in translation. FEBS Lett 2005; 579:938-42; PMID:15680978; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. Recent mechanistic insights into eukaryotic ribosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2009; 21:435-43; PMID:19243929; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling J, Reynolds N, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and translational quality control. Annu Rev Microbiol 2009; 63:61-78; PMID:19379069; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benzer S, Champe SP. A change from nonsense to sense in the genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1962; 48:1114-21; PMID:13867417; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.48.7.1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stretton AO, Brenner S. Molecular consequences of the amber mutation and its suppression. J Mol Biol 1965; 12:456-65; PMID:14337507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80268-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigert MG, Garen A. Base composition of nonsense codons in E. coli. Evidence from amino-acid substitutions at a tryptophan site in alkaline phosphatase. Nature 1965; 206:992-4; PMID:5320271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/206992a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner S, Barnett L, Katz ER, Crick FH. UGA: a third nonsense triplet in the genetic code. Nature 1967; 213:449-50; PMID:6032223; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/213449a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crick FH, Barnett L, Brenner S, Watts-Tobin RJ. General nature of the genetic code for proteins. Nature 1961; 192:1227-32; PMID:13882203; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/1921227a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawthorne DC, Mortimer RK. Super-suppressors in yeast. Genetics 1963; 48:617-20; PMID:13953232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manney TR. Action of a super-suppressor in yeast in relation to allelic mapping and complementation. Genetics 1964; 50:109-21; PMID:14191344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman F. Suppression in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Molecular Biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: Metabolism and Gene Expression. Ed. by Strathern JN, et al. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories, New York: 1982; 463-486. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsh D. Tryptophan transfer RNA as the UGA suppressor. J Mol Biol 1971; 58:439-58; PMID:4933412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90362-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawthorne DC, Leupold U. Suppressors in yeast. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1974; 64:1-47; PMID:4602646; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-642-65848-8_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capecchi MR, Hughes SH, Wahl GM. Yeast super-suppressors are altered tRNAs capable of translating a nonsense codon in vitro. Cell 1975; 6:269-77; PMID:802681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90178-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piper PW, Wasserstein M, Engbaek F, Kaltoft K, Celis JE, Zeuthen J, Liebman S, Sherman F. Nonsense suppressors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be generated by mutation of the tyrosine tRNA anticodon. Nature 1976; 262:757-61; PMID:785283; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/262757a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pure GA, Robinson GW, Naumovski L, Friedberg EC. Partial suppression of an ochre mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by multicopy plasmids containing a normal yeast tRNAGln gene. J Mol Biol 1985; 183:31-42; PMID:2989539; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90278-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss WA, Friedberg EC. Normal yeast tRNA(CAGGln) can suppress amber codons and is encoded by an essential gene. J Mol Biol 1986; 192:725-35; PMID:3295253; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss WA, Edelman I, Culbertson MR, Friedberg EC. Physiological levels of normal tRNA(CAGGln) can effect partial suppression of amber mutations in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987; 84:8031-4; PMID:3120182; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.84.22.8031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beier H, Grimm M. Misreading of termination codons in eukaryotes by natural nonsense suppressor tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29:4767-82; PMID:11726686; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/29.23.4767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inge-Vechtomov SG. Reversions to prototrophy in yeast deficient by adenine. Vestnik LGU 1964; 2:112-7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inge-Vechtomov SG, Andrianova VM. Recessive super-suppressors in yeast. Russ J Genet 1970; 6:103-15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smirnov VN, Kreier VG, Lizlova LV, Andrianova VM, Inge-Vechtomov SG. Recessive super-suppression in yeast. Mol Gen Genet 1974; 129:105-21; PMID:4598794; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00268625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerlach WL. Genetic properties of some amber-ochre supersuppressors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 1975; 138:53-63; PMID:1102924; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00268827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox BS. Allosuppressors in yeast. Genet Res 1977; 30:187-205; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0016672300017584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culbertson MR, Gaber RF, Cummins CM. Frameshift suppression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. V. Isolation and genetic properties of nongroup-specific suppressors. Genetics 1982; 102:361-78; PMID:6757053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono B, Moriga N, Ishihara K, Ishiguro J, Ishino Y, Shinoda S. Omnipotent Suppressors Effective in psi Strains of SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE: Recessiveness and Dominance. Genetics 1984; 107:219-30; PMID:17246215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikuchi Y, Shimatake H, Kikuchi A. A yeast gene required for the G1-to-S transition encodes a protein containing an A-kinase target site and GTPase domain. EMBO J 1988; 7:1175-82; PMID:2841115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frolova L, Le Goff X, Rasmussen HH, Cheperegin S, Drugeon G, Kress M, Arman I, Haenni AL, Celis JE, Philippe M, et al. A highly conserved eukaryotic protein family possessing properties of polypeptide chain release factor. Nature 1994; 372:701-3; PMID:7990965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/372701a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhouravleva G, Frolova L, Le Goff X, Le Guellec R, Inge-Vechtomov S, Kisselev L, Philippe M. Termination of translation in eukaryotes is governed by two interacting polypeptide chain release factors, eRF1 and eRF3. EMBO J 1995; 14:4065-72; PMID:7664746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stansfield I, Jones KM, Kushnirov VV, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Poznyakovski AI, Paushkin SV, Nierras CR, Cox BS, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Tuite MF. The products of the SUP45 (eRF1) and SUP35 genes interact to mediate translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 1995; 14:4365-73; PMID:7556078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono BI, Stewart JW, Sherman F. Serine insertion caused by the ribosomal suppressor SUP46 in yeast. J Mol Biol 1981; 147:373-9; PMID:6273576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90489-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eustice DC, Wakem LP, Wilhelm JM, Sherman F. Altered 40 S ribosomal subunits in omnipotent suppressors of yeast. J Mol Biol 1986; 188:207-14; PMID:3522920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90305-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.All-Robyn JA, Brown N, Otaka E, Liebman SW. Sequence and functional similarity between a yeast ribosomal protein and the Escherichia coli S5 ram protein. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10:6544-53; PMID:2247072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent A, Liebman SW. The yeast omnipotent suppressor SUP46 encodes a ribosomal protein which is a functional and structural homolog of the Escherichia coli S4 ram protein. Genetics 1992; 132:375-86; PMID:1427034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alksne LE, Anthony RA, Liebman SW, Warner JR. An accuracy center in the ribosome conserved over 2 billion years. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90:9538-41; PMID:8415737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anthony RA, Liebman SW. Alterations in ribosomal protein RPS28 can diversely affect translational accuracy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1995; 140:1247-58; PMID:7498767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendrick JL, Wilson PG, Edelman II, Sandbaken MG, Ursic D, Culbertson MR. Yeast frameshift suppressor mutations in the genes coding for transcription factor Mbf1p and ribosomal protein S3: evidence for autoregulation of S3 synthesis. Genetics 2001; 157:1141-58; PMID:11238400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chernoff YO, Vincent A, Liebman SW. Mutations in eukaryotic 18S ribosomal RNA affect translational fidelity and resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. EMBO J 1994; 13:906-13; PMID:8112304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chernoff YO, Newnam GP, Liebman SW. The translational function of nucleotide C1054 in the small subunit rRNA is conserved throughout evolution: genetic evidence in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93:2517-22; PMID:8637906; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velichutina IV, Hong JY, Mesecar AD, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic interaction between yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae release factors and the decoding region of 18 S rRNA. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:715-27; PMID:11162087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Velichutina IV, Dresios J, Hong JY, Li C, Mankin A, Synetos D, Liebman SW. Mutations in helix 27 of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae 18S rRNA affect the function of the decoding center of the ribosome. RNA 2000; 6:1174-84; PMID:10943896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1355838200000637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu R, Liebman SW. A translational fidelity mutation in the universally conserved sarcin/ricin domain of 25S yeast ribosomal RNA. RNA 1996; 2:254-63; PMID:8608449 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panopoulos P, Dresios J, Synetos D. Biochemical evidence of translational infidelity and decreased peptidyltransferase activity by a sarcin/ricin domain mutation of yeast 25S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:5398-408; PMID:15477390; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkh860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baxter-Roshek JL, Petrov AN, Dinman JD. Optimization of ribosome structure and function by rRNA base modification. PLoS One 2007; 2:e174; PMID:17245450; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MW, Meskauskas A, Wang P, Sergiev PV, Dinman JD. Saturation mutagenesis of 5S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21:8264-75; PMID:11713264; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8264-8275.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandbaken MG, Culbertson MR. Mutations in elongation factor EF-1 alpha affect the frequency of frameshifting and amino acid misincorporation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1988; 120:923-34; PMID:3066688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song JM, Picologlou S, Grant CM, Firoozan M, Tuite MF, Liebman S. Elongation factor EF-1 alpha gene dosage alters translational fidelity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1989; 9:4571-5; PMID:2685557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silar P, Picard M. Increased longevity of EF-1 alpha high-fidelity mutants in Podospora anserina. J Mol Biol 1994; 235:231-6; PMID:8289244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carr-Schmid A, Valente L, Loik VI, Williams T, Starita LM, Kinzy TG. Mutations in elongation factor 1beta, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, enhance translational fidelity. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19:5257-66; PMID:10409717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hatin I, Fabret C, Namy O, Decatur WA, Rousset JP. Fine-tuning of translation termination efficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae involves two factors in close proximity to the exit tunnel of the ribosome. Genetics 2007; 177:1527-37; PMID:17483428; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.107.070771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valouev IA, Fominov GV, Sokolova EE, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Elongation factor eEF1B modulates functions of the release factors eRF1 and eRF3 and the efficiency of translation termination in yeast. BMC Mol Biol 2009; 10:60; PMID:19545407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-10-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Synetos D, Frantziou CP, Alksne LE. Mutations in yeast ribosomal proteins S28 and S4 affect the accuracy of translation and alter the sensitivity of the ribosomes to paromomycin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996; 1309:156-66; PMID:8950190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0167-4781(96)00128-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dresios J, Derkatch IL, Liebman SW, Synetos D. Yeast ribosomal protein L24 affects the kinetics of protein synthesis and ribosomal protein L39 improves translational accuracy, while mutants lacking both remain viable. Biochemistry 2000; 39:7236-44; PMID:10852723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi9925266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dresios J, Panopoulos P, Frantziou CP, Synetos D. Yeast ribosomal protein deletion mutants possess altered peptidyltransferase activity and different sensitivity to cycloheximide. Biochemistry 2001; 40:8101-8; PMID:11434779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi0025722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woolhead CA, McCormick PJ, Johnson AE. Nascent membrane and secretory proteins differ in FRET-detected folding far inside the ribosome and in their exposure to ribosomal proteins. Cell 2004; 116:725-36; PMID:15006354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00169-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Czaplinski K, Ruiz-Echevarria MJ, Paushkin SV, Han X, Weng Y, Perlick HA, Dietz HC, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Peltz SW. The surveillance complex interacts with the translation release factors to enhance termination and degrade aberrant mRNAs. Genes Dev 1998; 12:1665-77; PMID:9620853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.12.11.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang W, Czaplinski K, Rao Y, Peltz SW. The role of Upf proteins in modulating the translation read-through of nonsense-containing transcripts. EMBO J 2001; 20:880-90; PMID:11179232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/20.4.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ono BI, Tanaka M, Kominami M, Ishino Y, Shinoda S. Recessive UAA suppressors of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1982; 102:653-64; PMID:6821248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ono B, Yoshida R, Kamiya K, Sugimoto T. Suppression of termination mutations caused by defects of the NMD machinery in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet Syst 2005; 80:311-6; PMID:16394582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1266/ggs.80.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leeds P, Wood JM, Lee BS, Culbertson MR. Gene products that promote mRNA turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1992; 12:2165-77; PMID:1569946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cui Y, Hagan KW, Zhang S, Peltz SW. Identification and characterization of genes that are required for the accelerated degradation of mRNAs containing a premature translational termination codon. Genes Dev 1995; 9:423-36; PMID:7883167; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.9.4.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weng Y, Czaplinski K, Peltz SW. Identification and characterization of mutations in the UPF1 gene that affect nonsense suppression and the formation of the Upf protein complex but not mRNA turnover. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16:5491-506; PMID:8816462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weng Y, Czaplinski K, Peltz SW. Genetic and biochemical characterization of mutations in the ATPase and helicase regions of the Upf1 protein. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16:5477-90; PMID:8816461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amrani N, Ganesan R, Kervestin S, Mangus DA, Ghosh S, Jacobson A. A faux 3′-UTR promotes aberrant termination and triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature 2004; 432:112-8; PMID:15525991; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chabelskaya S, Gryzina V, Moskalenko S, Le Goff C, Zhouravleva G. Inactivation of NMD increases viability of sup45 nonsense mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Mol Biol 2007; 8:71; PMID:17705828; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-8-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Czaplinski K, Majlesi N, Banerjee T, Peltz SW. Mtt1 is a Upf1-like helicase that interacts with the translation termination factors and whose overexpression can modulate termination efficiency. RNA 2000; 6:730-43; PMID:10836794; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1355838200992392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cosson B, Couturier A, Chabelskaya S, Kiktev D, Inge-Vechtomov S, Philippe M, Zhouravleva G. Poly(A)-binding protein acts in translation termination via eukaryotic release factor 3 interaction and does not influence [PSI(+)] propagation. Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22:3301-15; PMID:11971964; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3301-3315.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amrani N, Ghosh S, Mangus DA, Jacobson A. Translation factors promote the formation of two states of the closed-loop mRNP. Nature 2008; 453:1276-80; PMID:18496529; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sachs AB, Davis RW. Translation initiation and ribosomal biogenesis: involvement of a putative rRNA helicase and RPL46. Science 1990; 247:1077-9; PMID:2408148; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.2408148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kervestin S, Li C, Buckingham R, Jacobson A. Testing the faux-UTR model for NMD: analysis of Upf1p and Pab1p competition for binding to eRF3/Sup35p. Biochimie 2012; 94:1560-71; PMID:22227378; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hosoda N, Kobayashi T, Uchida N, Funakoshi Y, Kikuchi Y, Hoshino S, Katada T. Translation termination factor eRF3 mediates mRNA decay through the regulation of deadenylation. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:38287-91; PMID:12923185; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C300300200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi T, Funakoshi Y, Hoshino S, Katada T. The GTP-binding release factor eRF3 as a key mediator coupling translation termination to mRNA decay. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:45693-700; PMID:15337765; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M405163200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keeling KM, Salas-Marco J, Osherovich LZ, Bedwell DM. Tpa1p is part of an mRNP complex that influences translation termination, mRNA deadenylation, and mRNA turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:5237-48; PMID:16809762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02448-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dori D, Choder M. Conceptual modeling in systems biology fosters empirical findings: the mRNA lifecycle. PLoS One 2007; 2:e872; PMID:17849002; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grousl T, Ivanov P, Malcova I, Pompach P, Frydlova I, Slaba R, Senohrabkova L, Novakova L, Hasek J. Heat shock-induced accumulation of translation elongation and termination factors precedes assembly of stress granules in S. cerevisiae. PLoS One 2013; 8:e57083; PMID:23451152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0057083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kofuji S, Sakuno T, Takahashi S, Araki Y, Doi Y, Hoshino S, Katada T. The decapping enzyme Dcp1 participates in translation termination through its interaction with the release factor eRF3 in budding yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 344:547-53; PMID:16630557; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nizhnikov AA, Magomedova ZM, Rubel AA, Kondrashkina AM, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Galkin AP. [NSI+] determinant has a pleiotropic phenotypic manifestation that is modulated by SUP35, SUP45, and VTS1 genes. Curr Genet 2012; 58:35-47; PMID:22215010; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00294-011-0363-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nizhnikov AA, Kondrashkina AM, Galkin AP. Interactions of [NSI+] prion-like determinant with SUP35 and VTS1 Genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Russ J Genet 2013; 49:1004-12; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1134/S1022795413100074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nizhnikov AA, Magomedova ZM, Saifitdinova AF, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Galkin AP. Identification of genes encoding potentially amyloidogenic proteins that take part in the regulation of nonsense suppression in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Russian Journal of Genetics: Applied Research. 2012; 2:398-404. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Urakov VN, Valouev IA, Lewitin EI, Paushkin SV, Kosorukov VS, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Itt1p, a novel protein inhibiting translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Mol Biol 2001; 2:9; PMID:11570975; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song JM, Liebman SW. Allosuppressors that enhance the efficiency of omnipotent suppressors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1987; 115:451-60; PMID:3552876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vincent A, Newnam G, Liebman SW. The yeast translational allosuppressor, SAL6: a new member of the PP1-like phosphatase family with a long serine-rich N-terminal extension. Genetics 1994; 138:597-608; PMID:7851758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen MX, Chen YH, Cohen PT. PPQ, a novel protein phosphatase containing a Ser +Asn-rich amino-terminal domain, is involved in the regulation of protein synthesis. Eur J Biochem 1993; 218:689-99; PMID:8269960; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Nadal E, Fadden RP, Ruiz A, Haystead T, Ariño J. A role for the Ppz Ser/Thr protein phosphatases in the regulation of translation elongation factor 1Balpha. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:14829-34; PMID:11278758; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M010824200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aksenova A, Muñoz I, Volkov K, Ariño J, Mironova L. The HAL3-PPZ1 dependent regulation of nonsense suppression efficiency in yeast and its influence on manifestation of the yeast prion-like determinant [ISP(+)]. [ISP+]. Genes Cells 2007; 12:435-45; PMID:17397392; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ivanov MS, Radchenko EA, Mironova LN. [The protein complex Ppz1p/Hal3p and nonsense suppression efficiency in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2010; 44:1018-26; PMID:21290823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCusker JH, Haber JE. crl mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae resemble both mutants affecting general control of amino acid biosynthesis and omnipotent translational suppressor mutants. Genetics 1988; 119:317-27; PMID:3294104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McCusker JH, Haber JE. Cycloheximide-resistant temperature-sensitive lethal mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1988; 119:303-15; PMID:3294103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gerlinger UM, Gückel R, Hoffmann M, Wolf DH, Hilt W. Yeast cycloheximide-resistant crl mutants are proteasome mutants defective in protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell 1997; 8:2487-99; PMID:9398670; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuroha K, Tatematsu T, Inada T. Upf1 stimulates degradation of the product derived from aberrant messenger RNA containing a specific nonsense mutation by the proteasome. EMBO Rep 2009; 10:1265-71; PMID:19798102; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/embor.2009.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuroha K, Ando K, Nakagawa R, Inada T. The Upf factor complex interacts with aberrant products derived from mRNAs containing a premature termination codon and facilitates their proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:28630-40; PMID:23928302; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.460691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rogoza T, Goginashvili A, Rodionova S, Ivanov M, Viktorovskaya O, Rubel A, Volkov K, Mironova L. Non-Mendelian determinant [ISP+] in yeast is a nuclear-residing prion form of the global transcriptional regulator Sfp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:10573-7; PMID:20498075; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1005949107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drozdova PB, Radchenko EA, Rogoza TM, Khokhrina MA, Mironova LN. [SFP1 controls translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via regulation of the Sup35p (eRF3) level]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2013; 47:275-81; PMID:23808161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aksenova AIu, Volkov KV, Rovinskiĭ NS, Svitin AV, Mironova LN. [Phenotypic manifestation of epigenetic determinant [ISP+] in Saccharomyces serevisiae depends on combination of mutations in SUP35 and SUP45 genes]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2006; 40:844-9; PMID:17086985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nizhnikov AA, Kondrashkina AM, Antonets KS, Galkin AP. Overexpression of genes encoding asparagine-glutamine-rich transcriptional factors causes nonsense suppression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Russian Journal of Genetics: Applied Research. 2014; 4:122-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1134/S2079059714020051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kandl KA, Munshi R, Ortiz PA, Andersen GR, Kinzy TG, Adams AE. Identification of a role for actin in translational fidelity in yeast. Mol Genet Genomics 2002; 268:10-8; PMID:12242494; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00438-002-0726-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ganusova EE, Ozolins LN, Bhagat S, Newnam GP, Wegrzyn RD, Sherman MY, Chernoff YO. Modulation of prion formation, aggregation, and toxicity by the actin cytoskeleton in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:617-29; PMID:16382152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.26.2.617-629.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mathur V, Taneja V, Sun Y, Liebman SW. Analyzing the birth and propagation of two distinct prions, [PSI+] and [Het-s](y), in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21:1449-61; PMID:20219972; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chernova TA, Romanyuk AV, Karpova TS, Shanks JR, Ali M, Moffatt N, Howie RL, O’Dell A, McNally JG, Liebman SW, et al. Prion induction by the short-lived, stress-induced protein Lsb2 is regulated by ubiquitination and association with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Cell 2011; 43:242-52; PMID:21777813; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]