Abstract

Background:

Acne is a common disorder among adolescents and young adults causing a considerable psychological impact including anxiety and depression. Isotretinoin, a synthetic oral retinoid is very effective in the treatment of moderate to severe acne. But there have been many reports linking isotretinoin to depression and suicide though no clear proof of association has been established so far.

Objective:

To determine whether oral isotretinoin increases the risk of depression in patients with moderate to severe acne.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and fifty patients with moderate to severe acne were treated with oral isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg/day for a period of 3 months. Their acne and depression scoring was done at baseline and then every month for the first 3 months and then at 6 months.

Results:

We found that the acne scoring reduced from 3.11 ± 0.49 to 0.65 ± 0.62 (P = < 0.001) at the end of 3 months. Also, the depression scoring decreased significantly from 3.89 ± 4.9 at the beginning of study to 0.45 ± 1.12 (P < 0.001) at the end of 3 months. Both the acne and depression scores continued to remain low at the end of 6 months at 0.5 ± 0.52 (P = < 0.001) and 0.18 ± 0.51 (P = < 0.001), respectively.

Conclusions:

Our study proves that oral isotretinoin causes significant clearance of acne lesions. It causes significant reduction in depression scores and is not associated with an increased incidence of depression or suicidal tendencies.

Keywords: Acne, depression, isotretinoin

What was known?

Oral isotretinoin has been linked to varied psychiatric adverse effects like depression and suicidal behavior

Introduction

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin involving the pilosebaceous units.[1] At any given time, most 16-18 year old and up to half of adults have acne.[2] In 60% of teenagers, the condition is sufficiently severe for them to seek medical advice.[3] In 7-17%, acne is of late onset (age over 25 years).[4] Acne causes significant psychological morbidity in its young sufferers.[5] There are several treatment options for acne based on its severity. Isotretinoin, a synthetic oral retinoid has great efficacy against moderate to severe acne.[6] But since its introduction to the market, it has been alleged to be associated with a variety of adverse psychiatric effects, including depression, psychosis, mood swings, violent behavior, suicide and suicide attempts.[7] However, a causal relationship has not yet been established and the link between isotretinoin use and psychiatric events remains controversial.

Materials and Methods

Objective

The main objective of our study was to determine whether oral isotretinoin significantly increases the risk of depression in patients with moderate to severe acne.

Patient selection

All patients who came to our outpatient department for the treatment of acne were graded as having Grade 1 to Grade 4 acne, based on the classification suggested by Tutakne et al. A detailed history was obtained pertaining to the onset and duration of acne, exacerbating factors, associated systemic illnesses, drug intake, any psychiatric illnesses, and the various forms of treatment taken for acne and/or other psychiatric illnesses in the past.

One hundred and fifty consecutive patients with Grade 2 to Grade 4 acne were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included those who have had other forms of therapy for acne in the previous 4 weeks, past history or family history of psychiatric illnesses and/or treatment for the same, abnormal lipid profile, children less than 14 years of age, pregnancy and lactation. Women of child bearing potential were advised to follow strict contraceptive measures before being enrolled in the study. Approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained and all patients signed an informed consent document.

Study design

It was an open-label prospective study. All patients included in the study underwent baseline investigations such as lipid profile, liver function tests, and a psychiatric evaluation. Depression scores were evaluated according to the “Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression” (HRSD-17 item scale) by a psychiatrist.

Treatment plan included administration of oral isotretinoin at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day for a period of 3 months. All patients also received topical clindamycin1% and adapalene 0.1%.

Patients were evaluated every month for the first 3 months and then at 6 months. At each visit, the acne and depression scoring was done with added observations on adverse effects. The lipid profile and liver function tests were done at the end of 1 and 3 months. The patients were followed up for a period of 6 months.

Statistical analysis

All statistical evaluations were done using SPSS version 17.0. The results are expressed as mean ± SD. Student's paired ‘t’ test and ‘repeated measures ANOVA’ were used for the statistical analysis of the data. Level of significance was P < 0.05.

Results

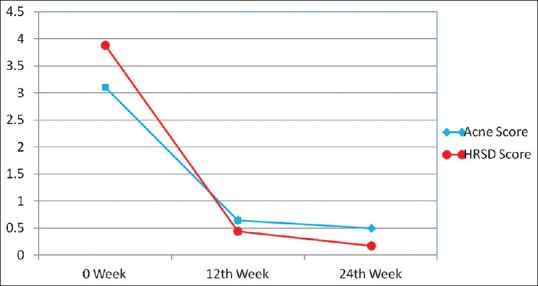

Of the 150 patients included in the study, 143 patients completed the study. There were 94 males and 49 females. Their ages ranged from 15 years to 37 years. (Mean 20.71 ± 3.2 years). The duration of lesions was from 1 week to 108 weeks. (Mean 25.06 ± 3.8 weeks) 102 patients (71%) had family history of acne in one or more first degree relative. 114 (79.7%) patients had associated seborrhea and 67 patients (46.95%) had pityriasis capitis. Seventeen (11.9%) patients had acne excoriee. There was significant clinical improvement as shown by the reduction in acne scores from 3.11 ± 0.49 to 0.65 ± 0.62 (P = <0.001) at the end of 12 weeks [Figure 1]. The acne score continued to remain low at the end of 6 months (0.5 ± 0.52, P = <0.001).

Figure 1.

Significant reduction of acne and depression scores from 0 week to 24 weeks

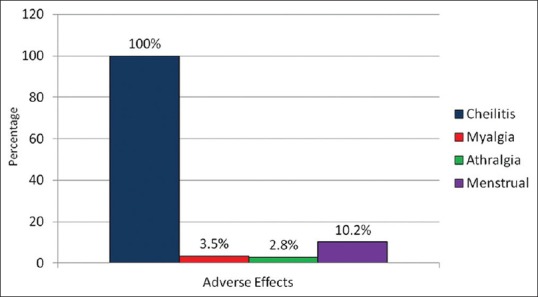

The HRSD scores showed that there was significant reduction in depression scores from 3.89 ± 4.9 to 0.45 ± 1.12 (P < 0.001) at the end of 3 months and there was a further reduction at the end of 6 months at 0.18 ± 0.51 (P = <0.001) [Figure 2]. The adverse effects observed during our study were cheilitis (100%), myalgia (3.5%), arthralgia (2.8%) and menstrual disturbances (10.2% of women).

Figure 2.

The spectrum of adverse effects encountered during the study

Discussion

Acne is a common disorder of adolescents and young adults characterized by seborrhea, the formation of comedones, erythematous papules and pustules, less frequently by nodules, deep pustules or cysts and in some cases, is accompanied by scarring.[8] Four major factors contribute to the pathogenesis of acne: (a) Increased sebum production, (b) hypercornification of the pilosebaceous duct, (c) colonization of the duct with Propionibacterium acnes and (d) production of inflammation.[9]

There are several grading systems for the evaluation of severity of acne. Tutakne et al., in 2003, suggested that acne be graded as 1 to 4 depending on the severity of skin lesions.[10] Acne is considered grade 1 if comedones and occasional papules are seen. Grade 2 acne consists of comedones, papules and a few pustules. When predominant pustules and nodules occur, it was considered as grade 3. The patient was said to have severe acne when there were cysts, abscesses and widespread scarring.

Therapeutic options for acne are chosen based on the grading and severity of acne. The various topical therapies used in the treatment of acne are topical antibiotics like tetracycline, erythromycin and clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide, retinoids and azelaic acid. Oral treatments used are antibiotics, isotretinoin and hormones. Other drugs like dapsone and clofazimine are rarely used.[11]

Oral isotretinoin revolutionized the treatment of acne when it was introduced in 1982. It still remains the most effective treatment for severe, recalcitrant and nodulocystic acne producing long-term remissions in most patients.[12] But it is recognized to have a varied range of adverse effects. The most notable of these is teratogenicity but other known side effects include mucocutaneous dryness causing cheilitis, nasal dryness and soreness, blepharoconjunctivitis, arthralgia and myalgia, headache, visual disturbances, transient rise in liver transaminases and serum triglyceride levels.[7] Also, concerns have been raised regarding its potential association with depression and suicidal behavior.[13] The relationship between isotretinoin and depression is controversial with some studies showing an increased risk while some others not demonstrating the same.

Oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is a synthetic oral retinoid which influences cellular processes such as differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis via retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid X receptor (RXR), and has therapeutic applications in the treatment of moderate to severe acne. Isotretinoin has been found to impair serotonin (5-HT) expressing neurons, including morphological changes and is thought to be associated with depressive symptoms.[14]

A number of case reports and case series linking isotretinoin to depression or suicide have appeared in the medical and psychological literature since 1982.[7] Between 1982 and 2000, the FDA has received reports of 394 cases of depression and 37 suicides occurring in patients exposed to isotretinoin.[15,16] In a number of these case reports, cessation of the drug has been associated with resolution of the mood disturbance and reinstitution of treatment has been followed by recurrence of depression.[15,16] But pitfalls in making inferences from case reports or case series are illustrated by the case reported by Kovacs and Mallory.[17] They describe a 17-year-old boy who developed behavior and mood changes while taking isotretinoin. Symptoms resolved with isotretinoin withdrawal, but reemerged with rechallenge, and the boy's psychological morbidity was attributed to isotretinoin. It later emerged that the boy's symptoms also coincided with periods of recreational drug abuse.

Prospective Canadian and US studies by Hull et al. and Bruno et al. found an incidence of depression in patients during a course of isotretinoin therapy of 4% and 11%, respectively.[18,19] However, in these trials, depression was self-reported in response to a questionnaire item. There was no objective measure of depression. Similar studies by Scheinman et al., Layton et al., Goulden et al., Mc Elwee et al., and Mc Lane et al. reported incidence of depression between 0% and 1%.[7] But in all these studies, depression and suicidal ideation were not specifically asked about or ascertained but were mostly self-reported side effects.

Jick et al. analyzed data from the Canadian Health Database and the US General Practice Research Database and found no increase in the relative risk of depression, psychosis or suicide over users of antibiotics for acne.[20] Similarly, there was no increased relative risk of these outcomes for prior treatment with isotretinoin versus post treatment.

Hersom et al. performed a retrospective prescription sequence symmetry analysis of isotretinoin and antidepressant pharmacotherapy using a large US database and demonstrated no support for an association between the use of isotretinoin and the onset of depression.[21] On the contrary, Chia et al. have demonstrated a decrease in the incidence of depressive symptoms in patients treated with isotretinoin.[22]

In our study, we found that the scoring for depression was higher prior to the onset of isotretinoin therapy. The scoring was found to decrease steadily during the treatment period and the reduction was found to be statistically significant at the end of three months of therapy. None of the patients developed worsening of their scores or suicidal thoughts during the 6 months of follow-up period. The most common adverse effect during our study was cheilitis. The lipid profile and liver function tests remained within normal levels throughout the study.

Conclusion

Our findings provide evidence to prove that oral isotretinoin causes significant clinical improvement in moderate to severe acne which is corroborated by a similar reduction in depression scores. It did not cause worsening of depression or suicidal thoughts in any of the patients in our study. However, large, randomized, prospective studies of longer duration are needed to further explore the risks of depression with isotretinoin.

What is new?

Our study shows that oral isotretinoin improves depression scores as shown by objective testing by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 2004;3:43–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J. Acne vulgaris: A disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones H. Acne vulgaris. Med Int. 1992;103:4340–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post adolescent acne: A review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhlenhake E, Yentzer BA, Feldman SR. Acne vulgaris and depression: A retrospective examination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9:59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162–9. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.3.9364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magin P, Pond D, Smith W. Isotretinoin, depression and suicide: A review of the evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:134–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purdy S, de Berker D. Acne. BMJ. 2006;333:949–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38987.606701.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunliffe WJ. Acne vulgaris: Pathogenesis and treatment. Br Med J. 1980;280:1394–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6229.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adityan B, Kumari R, Thappa DM. Scoring systems in acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:323–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.51258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimball AB. Advances in the treatment of acne. J Reprod Med. 2008;53:742–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatological conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171–82. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ault A. Isotretinoin use may be linked with depression. Lancet. 1998;351:730. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa J, Sutoh C, Ishikawa A, Kagechika H, Hirano H, Nakamura S. 13-cis-retinoic acid alters the cellular morphology of slice-cultured serotonergic neurons in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2363–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J. An analysis of reports of depression and suicide in patients treated with isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:515–9. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J. Depression and suicide in paqtients treated with isotretinoin. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs SO, Mallory SB. Mood changes associated with isotretinoin and substance abuse. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:350. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull PR, Demkiw-Bartel C. Isotretinoin use in acne: Prospective evaluation of adverse events. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:66–70. doi: 10.1177/120347540000400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruno NP, Beacham BE, Burnett JW. Adverse effects of Isotretinoin therapy. Cutis. 1984;33:484–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jick SS, Kremers HM, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C. Isotretinoin use and the risk of depression, psychotic symptoms, suicideand attempted suicide. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1231–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersom K, Neary MP, Levaux HP, Klaskala W, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin and antidepressant pharmacotherapy: A prescription sequence symmetry analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:424–32. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)02087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chia CY, Lane W, Chibnall J, Allen A, Siegfried E. Isotretinoin therapy and mood changes in adolescents with moderate to severe acne: A cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:557–60. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]