Abstract

The giardiasis is a neglected parasitic disease. The WHO has estimated more than 280 million of human infections each year; however, intraepithelial giardiasis is a rare entity, there are only 5 reports showing invasive giardiasis.

A pediatric female patient with chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, or pasty stools, without fever, was seen in the Gastroenterology and Nutrition Service. The stool studies were negative for pathogens and lactose hydrogen breath test was positive. The presumptive clinical diagnosis was giardiasis and the patient was empirically treated with nitazoxanide. But, the patient persisted with abdominal pain and pasty stools.

Endoscopy was indicated to search for Helicobacter and Giardia. Guardian and patient gave written informed consent. Hematological profile was normal. The endoscopy was performed under general anesthesia and the biopsies and duodenal aspirate were obtained. The microscopic analyses of duodenal fluid showed Giardia trophozoites. Electron microscopic analysis was negative for Helicobacter pylori, but Giardia trophozoites with a typical crescent shape within the tissue were found.

The patient was treated with tinidazole, subsequent tests showed that lactose absorption was normal, stool examinations were negative for Giardia and abdominal pain had stopped.

This case suggest that intraepithelial giardiasis could be a common entity but unseen because the giardiasis diagnosis is usually made on fecal samples. Future studies are necessary to determine the role of intraepithelial trophozoites in giardiasis pathogenic mechanisms

INTRODUCTION

Giardia intestinalis (also known as G lamblia or G duodenalis) is a successful intestinal parasite that causes waterborne diarrhea in humans and other mammals throughout the world.1 The WHO has estimated more than 280 million of human infections each year only in Africa, Asia, and America.2 In Mexico the seroprevalence is 55.3%.3 Giardiasis can be asymptomatic or symptomatic characterized by foul smelling diarrhea, with abdominal pain that is exacerbated by eating, flatulence, anorexia, and weight loss. In patients with chronic giardiasis there are periods with constipation or diarrhea with steatorrhea; nutriments malabsorption, and lactase deficiency.4,5 The parasite impairs the children's physical and mental development, especially those in developing countries.6 The giardiasis was included in the “neglected diseases initiative” in 2004.7

The G intestinalis morphological simplicity hides a big genetic variability; using molecular tools, have been described 8 assemblages/genotypes, A to H. Assemblages A (subgenotypes A–I and A–II) and B infect humans and other mammals, C and D mainly live in dogs, E thrive in artiodactyls, F in felines, G was described in rats,8,9 and H harbored in marine mammal.10

The pathogenic mechanism involves trophozoites adhesion to epithelial cells by the ventral suckling disc, using non-specific mechanical forces and/or specific interactions with lectins11 and annexins.12 The interaction between Giardia suckling disc and enterocytes generates a lesion on microvillus border of epithelium,13 that alter the ionic cell equilibrium, augmenting the peristalsis and producing diarrhea. There is also an increase in intestinal permeability caused by modifications in the zonula-occludens (ZO) tight-junction.14,15Giardia trophozoites have evolved to colonize an adverse environment, therefore, the parasite is able to modify and manipulate its milieu in several ways such as: competition for arginine to reduce the Nitric Oxide (NO) production in epithelial cells;16 the contact with the Giardia variable surface proteins (VSPs) to modulate the protein–protein interactions,17 as well as zinc/iron depletion18 and antigenic variation to avoid immune attack.19,20 The proteinase secretions protect trophozoites by degrading secreted IgA, or perhaps acting like caspases aimed to promote apoptosis.21 Interaction Giardia-enterocyte induces goblet cells hyperplasia and consequently produces cellular gaps on the epithelial barrier.22 It has been demonstrated that tight interaction between Giardia and Caco2 cells start the modulation in gene expression of the immune response23 and a complex genomic interactions with down/up gene regulations in Giardia.24 All these phenomena, directly or indirectly, could deteriorate the epithelial barrier. In Mexico, there is a predominance of Giardia assemblage A in symptomatic or asymptomatic patients,25,26 until now, it has been impossible to make an unequivocal differentiation between asymptomatic Giardia isolates from those capable to produce clinical symptomatology.27–29 Therefore is necessary to think in alternative hypothesis, then we wish to present the case of Giardia trophozoites within the intestinal epithelium from a patient with chronic abdominal pain and lactose intolerance, and a review of the literature.

PATIENT AND METHODS

Case Report

A patient of 9.5 year old, with chronic pain abdominal was admitted in the Gastroenterology and Nutrition Service and integrated to: The chronic abdominal pain protocol, authorized by the Ethical and Research Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Pediatría. The patient had history of diarrhea or pasty stools, neither fever nor vomiting. The feces from patient were processed seeking for pathogenic bacteria and the results were negatives. The microscopic examination looking for cysts and ova after the centrifugation-concentration method30 was negative for cysts and eggs. The lactose hydrogen breath test was positive. The presumptive clinical diagnosis was giardiasis and the patient was empirically treated with nitazoxanide (7.5 mg/kg/12 h/3 days). However, the patient persisted with abdominal pain and pasty stools; therefore, endoscopy was indicated to search for Helicobacter and Giardia. Hematological profile was: white blood cells 4700/mL, neutrophils 44%, hemoglobin 14.7 g/dL, hematocrit 43.2%, mean corpuscular volume 83.4 fL, platelets 262,000/mL, prothrombin time 13.6 seconds (90.4% and INR 1.13). The signed informed written consent was obtained form guardian and from patient. The endoscopy was performed in the Endoscopy Service under general anesthesia using the endoscopic video imaging system Olympus GIF-Q150 (Japan), the biopsies were taken from the first and second duodenal portions and antrum. The duodenal aspirate was obtained using a sterile aspirate kit (Portex-Specimen-Trap, Smith Medical International) compatible with the suction mechanism in endoscope.

Duodenal tissue was placed in a glass container with 2% glutaraldehyde buffered in 0.1 M phosphate buffered solution at pH 7.2. Samples were submitted to the Experimental parasitology and Electron microscopy laboratories. The microscopic analyses of duodenal fluid, under phase contrast illumination showed Giardia trophozoites, subsequently, duodenal aspirate was cultured in sterile TYI-S-33 medium and incubated at 37 °C. In a new stool sample from patient Giardia cyst were identify. Afterward, the patient was under treatment based on tinidazole at 75 mg/kg/day/4 days. Subsequent tests showed that lactose absorption was normal, stool examinations were negative for Giardia and abdominal pain had stopped.

Literature Search

A systematic review was made in PubMed (US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health) search database of invasive giardiasis in human. We searched the MEDLINE database for the following terms: “Giardia invasion” “Giardia invasion man”.

Electron Microscopy

The duodenal samples were post-fixed with osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in epon resin. Semi-thin sections (0.5–1 μm) were cut and stained with toluidine blue for light microscopic examination. Ultra-thin sections (60–90 nm) were cut and collected on slot grids covered with formvar membrane. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a JEM-1011 (JEOL, Osaka, Japan) microscope.

Giardia Trophozoites Culture

The cysts from the stool samples were concentrated using a sucrose solution. The excystation was induced in Hank balanced salt solution (HBSS) at pH 2.0 for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Induced cysts were washed with 37 °C HBSS at pH 7.4, concentrated by centrifugation and placed in warm TYI-S-33 to complete excystation, as described elsewhere.31 Bacterial and/or fungal contamination was tested with cultures in blood agar and Sabouraud medium.

Genotyping

DNA samples from cysts and trophozoites were obtained using QIAamp spin columns following the manufacturer instructions (Quiagen GmbH, D-40724 Hilden, Germany). The Giardia isolate was genotyped using hemi-nested PCR and RFLP analysis of a segment from the glutamate dehydrogenase gene using primers described by Read9 and with the endonuclease NlaIV. The RFLP pattern was observed using 5% acrylamide gel electrophoresis stained with a silver stain kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. 2000 Alfred Nobel Drive Hercules, CA 94547, USA) following the supplier instructions. The genotype was confirmed by repeating the PCR and RFLP analysis using reagents specific for a segment of the VSP417 gene.25

RESULTS

Electron Microscopy

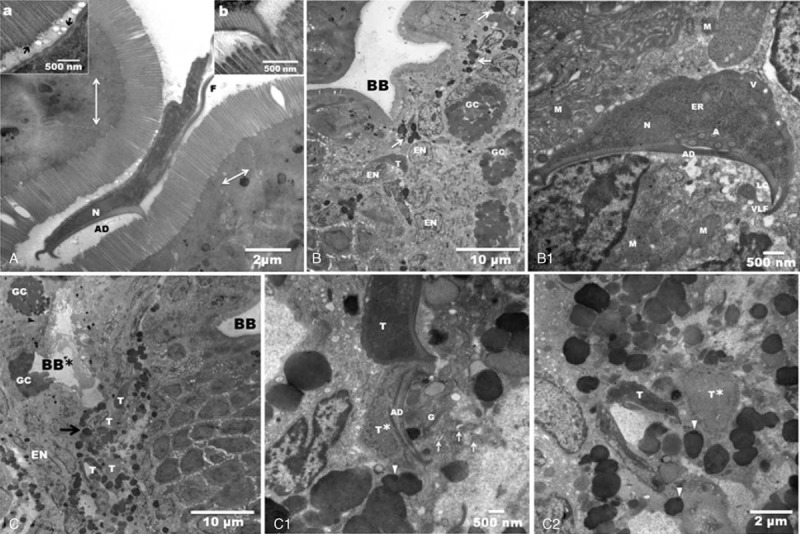

Electron microscopic analysis was negative for H pylori. The Giardia trophozoites were found in several areas. In semi-thin sections we found trophozoites in submucosa (Figure 1). Other trophozoites were found in the lumen as well as within the epithelium (Figure 2A–C). Electron microscopy showed trophozoites in tight contact with the intestinal microvilli (Figure 2A). Trophozoite with a typical crescent shape was also embedded in the tissue between the enterocytes nuclei and goblet cells. Scattered electron-dense granules were evident in the tissue, giving the impression that these granules were following the tracks of the parasites. The brush border appeared normal (Figure 2B). At higher magnification, the trophozoite had ultrastructural integrity it seems interacting with the enterocyte nucleus. There was cell lysis and damaged organelles surrounding the trophozoite (Figure 2B1). We found areas with either intact (BB) or abnormal (BB∗) brush borders. In areas with abnormal microvilli, there were lysed cells and many electron-dense granules that formed a channel that appeared to flow into the tissue. Trophozoites were found between granules at the level of the nuclei and goblet cells (Figure 2C). At a higher magnification, we found that some trophozoites in the epithelium were structurally intact and other damaged. The presence of eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs) was observed32 (Figure 2C1, 2C2).

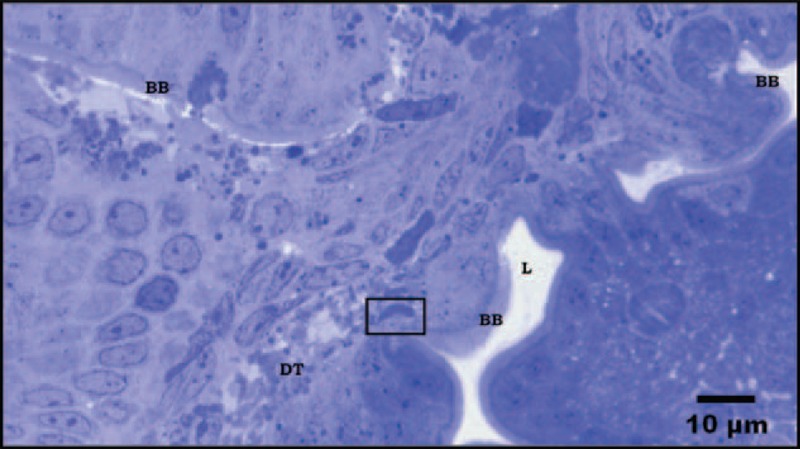

FIGURE 1.

Semi-thin section from duodenal biopsy shows panoramic view of different cutting planes. Several areas of the epithelium with normal appearance and intact trophozoite within the damaged submucosa are shown. BB: Brush border; DT: Damage tissue. Stain toluidine blue.

FIGURE 2.

Transmission electron micrographs are showing intraepithelial trophozoites from a patient biopsy. A: Giardia trophozoite attached on the normal duodenal brush border, (N) nucleus, (AD) adhesive disc and (F) flagellum. There is a remarkable integrity of the intestinal intercellular tight junctions (arrows). Inset (a) shows small vacuoles between cellular microvillus and the plasma membrane of the trophozoite (arrows), suggesting a biochemical interaction. Inset (b) shows that the microvilli and ventral disc interactions give rise to an electron-dense zone. B: Panoramic of the duodenal epithelium with a brush border (BB) of normal appearance. At the level of the enterocyte nuclei (EN) and goblet cell (GC) there is a trophozoite (T). Note the electron-dense granules dispersed in the tissue (arrows). B1: Higher magnification shows the normal architecture of the trophozoite, which appears to be attached with its adhesive disc (AD) to one nucleus. Note the vacuoles (V) in the normal plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), axonemes (A), nucleus (N), lateral crest (LC), and ventrolateral flange (VLF). Lysed cells were found near the adhesive disc. Several damaged mitochondria (M). C: Low magnification of the duodenal epithelium. There is damage in the epithelial tissue and in the brush border (BB∗), which is the likely site of entry of the trophozoites (T). We clearly see 4 trophozoites surrounded by electron-dense granules (arrow). In another area, the brush border appears intact (BB). C1: High magnification shows an intact trophozoite (T) and another trophozoite with total lysis of the dorsal membrane (T∗), and fragmentation of it adhesive disc (AD). Nearby, there are eosinophil sombrero vesicles (arrows), granules (arrowheads), and Golgi bodies (G). C2: Two Giardia trophozoites surrounded by granules (arrowheads); one looks swollen (T∗), and the other has a normal morphology (T).

Giardia Culture and Molecular Genotyping

The Giardia trophozoites obtained by duodenal aspirate were unable to survive in axenic culture after 1 week. Trophozoites isolated by the excystation method were established in the axenic culture medium, and this Giardia isolate was designated INP220806-HGINV. The Giardia isolate belong to assemblage A, genetic group A2.

Literature Review

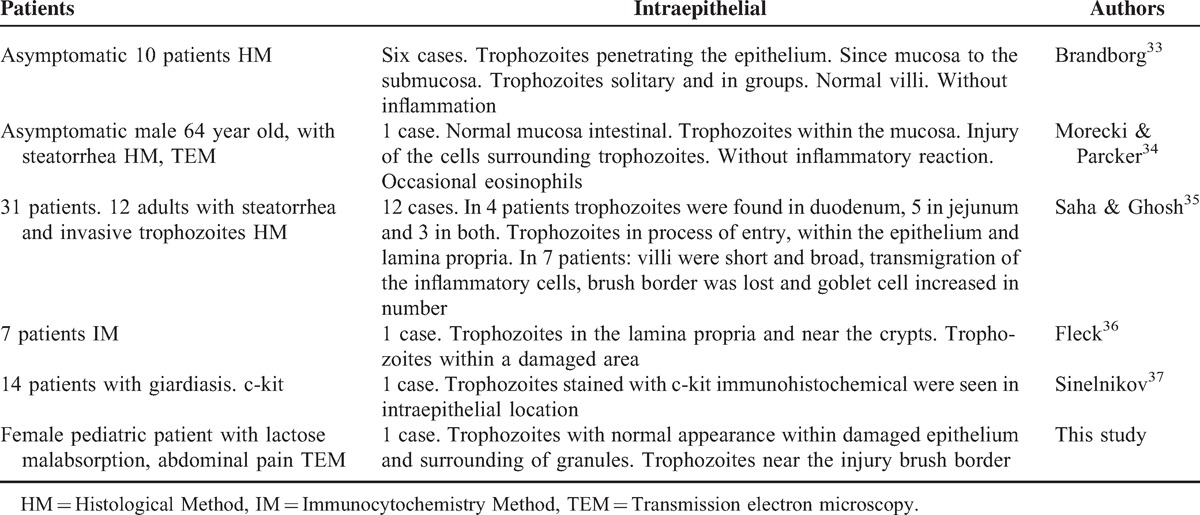

Reports of intraepithelial Giardia trophozoites are unusual; we found 5 reports in the literature.33–37 In these works, the tissue was processed with standard methods for light or electron microscopy and presents in clear way the trophozoites presence within the duodenal tissue (Table 1). Included the patient from this work 64 patients were analyzed. In 21 patients were seen trophozoites within epithelium, mucosa, lamina propria, submucosa or near of the crypts. The Sinelnikov37 report is unclear because does not explain in how much of 14 patients they find with intraepithelial trophozoites. Besides, none was able to isolate and culture the Giardia trophozoites. Until now, this is the first culture of G intestinalis isolate with ability to invade the epithelium.

TABLE 1.

Invasive Giardiasis Summary of Reported Cases

DISCUSSION

The intestinal invasion of G intestinalis trophozoites is not accepted.38 Data from humans and experimental infections in animals show trophozoites in the lumen and on the surface of the mucosa of the small intestine. However, we found intraepithelial trophozoites in the biopsy from 1 patient with chronic abdominal pain and lactose malabsorption. For the first time Giardia trophozoites with potential to be invaders were successfully excysted, and maintained in culture in TYI-S-33 medium. Cyst and trophozoites from this isolate were genotyped; they belong to assemblage A, genetic group A2, which is a common genotype in our country.25 These data are important because there are discrepancies regarding the use of assemblages/genotypes as pathogenic markers.27–29

The literature review showed 20 cases of invasive Giardia trophozoites, including this one there are 21 cases with invasive trophozoites.33–37 Previously we showed trophozoites during the invasion process and goblet cells hyperplasia in samples from dogs.22 Here, we are showing trophozoites with and without a normal morphology inside the epithelium, many granules surrounded the trophozoites, which may be from eosinophils because EoSVs were recognized. No inflammatory cells were observed. Owen et al39 suggest that reports showing invasive trophozoites result from mistakes in the sample collection and preparation processes, rather than true invasion. Trophozoites may take advantage of breaks in the epithelium before fixation and may use their flagella to enter into the epithelium.

This and other studies evidence Giardia trophozoites inside the intestinal epithelium, suggesting that there is invasive Giardia isolates, but these trophozoites are not detected because the duodenal biopsy is an invasive technique and giardiasis diagnosis is performed by stool analysis. Future studies are necessary to reproduce, based on the INP220806-HGINV culture, the epithelial invasion phenomenon in an animal model, and to determine whether intraepithelial parasites play a role in the pathogenic mechanisms involved in symptomatic giardiasis.

In the medical literature there are few cases of invasive giardiasis. Analysis of this case and the review of the literature suggest that patients with steatorrhea, abdominal pain, or lactose malabsorption could have trophozoites with the potential to be invaders.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thompson RCA. Giardiasis as a re-emerging infectious disease and its zoonotic potential. Int J Parasitol 2000; 30:1259–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comité OMS d’Experts, “Importance des parasitoses intestinalis en santé publique,” Bulletin de la Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, no. 66, vol. 1, 23–34, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cedillo-Rivera R, Yelda A, Yépez-Mulia L, et al. Seroepidemiology of giardiasis in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 80:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill DR. Giardiasis. Issues in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1993; 7:503–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rana SV, Bhasin DK, Vinayak VK. Lactose hydrogen breathe test in Giardia lamblia positive patients. Dig Dis Sci 2005; 50:259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eppig C, Fincher CL, Thornhill R. Parasite prevalence and the worldwide distribution of cognitive ability. Proc R Soc B 2010; 277:3801–3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Savioly L, Smith H, Thompson A. Giardia and Cryptosporidium join the “neglected diseases initiative”. Trends Parasitol 2006; 22:203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monis PT, Andrews RH, Mayrhofer G, Ey PL. Molecular systematics of the parasitic protozoan Giardia intestinalis. Mol Biol Evol 1999; 16:1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Read CM, Monis PT, Thompson RC. Discrimination of all genotypes of Giardia duodenalis at the glutamate dehydrogenase locus using PCR-RFLP. Infect Genet Evol 2004; 4:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasek-Nesselquist E, Welch DM, Sogin ML. The identification of a new Giardia duodenalis assemblage in marine vertebrates and a preliminary analysis of G. duodenalis population biology in marine systems. Int J Parasitol 2010; 40:1063–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lev BI, Ward HD, Keusch GT, Pereira MEA. Lectin activation in Giardia lamblia by host protease: a novel host–parasite interaction. Science 1986; 23:71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiland MEL, Palm JE, Griffiths WJ, et al. Characterization of alpha-1 giardin: an immunodominant Giardia lamblia annexin with glycosaminoglycan-binding activity. Int J Parasitol 2003; 33:1341–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlandsen SL, Sherlock LA, Januschka M, et al. Cross-species transmission of Giardia spp.: inoculation of beavers and muskrats with cysts of human beaver mouse and muskrat origin. Appl Environ Microbiol 1988; 54:2777–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buret AG, Mitchell K, Muench DG, Scott KGE. Giardia lamblia disrupts tight junctional ZO-1 and increases permeability in non-transformed human small intestinal epithelial monolayers: effects of epidermal growth factor. Parasitology 2002; 125:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troeger H, Epple HJ, Schneider T, et al. Effect of chronic Giardia lamblia infection on epithelial transport and barrier function in human duodenum. Gut 2007; 56:328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckmann L, Laurent F, Langford D, et al. Nitric oxide production by human intestinal epithelial cells and competition for arginine as potential determinants of host defense against the lumen-dwelling pathogen Giardia lamblia. J Immunol 2000; 164:1478–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer SM, Elmendorf HG, Conrad JT, Nash TE. Biological selection of variant-specific surface proteins in Giardia lamblia. J Infect Dis 2000; 183:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luján HD, Mowatt MR, Wu JJ, et al. Purification of a variant-specific surface protein of Giardia lamblia and characterization of its metal-binding properties. J Biol Chem 1995; 270:13807–13813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nash TE. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia and the host's immune response. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1997; 352:1369–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nash TE. Surface antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia. Mol Microbiol 2002; 45:585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin AC, Teoth DA, Scott KG, et al. Strain-dependent induction of enterocyte apoptosis by Giardia lamblia disrupts epithelial barrier function in a caspase-3-dependent manner. Infect Immun 2002; 70:3673–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponce-Macotela M, González-Maciel A, Reynoso-Robles R, Martínez-Gordillo MN. Goblet cells: are they the first unspecific barrier against Giardia intestinalis or a gate? Parasitol Res 2008; 102:509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roxström-Lindquist K, Ringqvist E, Palm D, Svärd S. Giardia lamblia-induced changes in gene expression in differentiated Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2005; 73:8204–8208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringqvist E, Avesson L, Söderbom F, Svärd SG. Transcriptional changes in Giardia during host–parasite interaction. Int J Parasitol 2011; 41:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ponce-Macotela M, Martínez-Gordillo MN, Bermúdez-Cruz RM, et al. Unusual prevalence of the Giardia intestinalis A-II subtype amongst isolates from humans and domestic animals in Mexico. Int J Parasitol 2002; 32:1201–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cedillo-Rivera R, Darvy JM, Enciso-Moreno JA, et al. Genetic homogeneity of axenic isolates of Giardia intestinalis derived from acute and chronically infected individuals in Mexico. Parasitol Res 2003; 90:119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homan WL, Mank TG. Human giardiasis: genotype linked differences in clinical symptomatology. Int J Parasitol 2001; 31:822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Read CM, Walters J, Robertson ID, Thompson RCA. Correlation between genotype of Giardia duodenalis and diarrhea. Int J Parasitol 2002; 32:229–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahagún J, Clavel A, Goñi P, et al. Correlation between the presence of symptoms and the Giardia duodenalis genotype. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008; 27:81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faust EC, D’Antoni JS, Odom V, et al. A critical study of clinical laboratory techniques for the diagnosis of protozoan cysts and helminth eggs in feces. Am J Trop Med 1938; 18:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feely DE. A simplified method for in vitro excystation of Giardia muris. J Parasitol 1986; 72:474–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo RC, Spencer LA, Dvorak AM, Weller PF. Mechanisms of eosinophil secretion: large vesiculotubular carriers mediate transport and release of granule-derived cytokines and other proteins. J Leukoc Biol 2008; 83:229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandborg LL, Tankersley CB, Gottlieb S, et al. Histological demonstration of mucosal invasion by Giardia lamblia in man. Gastroenterology 1967; 52:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morecki R, Parker JG. Ultrastructural studies of the human Giardia lamblia and subjacent jejunal mucosa in a subject with steatorrhoea. Gastroenterology 1967; 52:151–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha TK, Ghosh TK. Invasion of small intestinal mucosa by Giardia lamblia in man. Gastroenterology 1977; 72:402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleck SL, Hames SE, Warhurst DC. Detection of Giardia in human jejunum by the immunoperoxidase method. Specific and non-specific results. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1985; 79:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinelnikov I, Sion-Vardy N, Shaco-Levi R. C-kit (CD117) immunostain is useful for the diagnosis of Giardia lamblia in duodenal biopsies. Hum Pathol 2009; 40:323–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eckmann L, Gillin FD. Microbes and microbial toxins: paradigms for microbial–mucosal interactions. I. Pathophysiological aspects of enteric infections with the lumen-dwelling protozoan pathogen Giardia lamblia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001; 280:G1–G6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owen RL, Nemanic PC, Stevens DP. Ultrastructural observations on giardiasis in a murine model. I. Intestinal distribution, attachment, and relationship to the immune system of Giardia muris. Gastroenterology 1979; 76:757–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]