Abstract

The covalent DNA modification of cytosine at position 5 (5-methylcytosine; 5mC) has emerged as an important epigenetic mark most commonly present in the context of CpG dinucleotides in mammalian cells. In pluripotent stem cells and plants, it is also found in non-CpG and CpNpG contexts, respectively. 5mC has important implications in a diverse set of biological processes, including transcriptional regulation. Aberrant DNA methylation has been shown to be associated with a wide variety of human ailments and thus is the focus of active investigation. Methods used for detecting DNA methylation have revolutionized our understanding of this epigenetic mark and provided new insights into its role in diverse biological functions. Here we describe recent technological advances in genome-wide DNA methylation analysis and discuss their relative utility and drawbacks, providing specific examples from studies that have used these technologies for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis to address important biological questions. Finally, we discuss a newly identified covalent DNA modification, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), and speculate on its possible biological function, as well as describe a new methodology that can distinguish 5hmC from 5mC.

Keywords: DNA methylation, epigenetics, high-throughput deep sequencing, 5-methylcytosine, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine

Epigenetic changes refer to stable, heritable, and reversible modifications. DNA methylation is one such epigenetic change and has been shown to be associated with almost every biological process (1–3). DNA methylation can increase the functional complexity of prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes by providing additional avenues for the control of cellular processes. DNA methylation is also dynamic and thus can control the timing of cellular events.

In prokaryotes, DNA methylation occurs at the C-5 or N-4 positions of cytosine, as well as the N-6 position of adenine. Multiple enzymes that are capable of methylating bacterial DNA have been identified and are named DNA-MTases (4). Initially, DNA methylation in bacteria was reported to be associated with restriction-modification systems, wherein foreign DNA that lacks DNA methylation can be recognized and degraded by host methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (4). Further studies in bacteria also implicated DNA methylation in the maintenance of the DNA replication fidelity, gene expression regulation, and virulence (2).

In plants, DNA methylation is found in the sequence context of CpG or CpNpG (5) and has been implicated in normal plant development (5) and regulation of transcription and transposition (5,6). At least two classes of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) have been identified and characterized in plants (5,7). These include the MET1 family of methyltransferases, which preferentially methylate cytosine in CpG context and function both as de novo and maintenance DNMTs (5), and a second class of DNMTs, named chromomethylases (CMTs), which are unique to plants and methylate cytosine in a CpNpG sequence context (7).

In mammalian cells, DNA methylation is predominantly found at CpG dinucleotides, but in some instances, such as in the case of mouse and human embryonic stem cells, DNA methylation can also be found in non-CpG contexts (8,9). DNA methylation in mammalian cells is associated with repression of transcription and maintenance of genomic stability. Due to its important role in genome maintenance and other biological processes, deregulation of DNA methylation is associated with multiple human diseases including cancer (3). Three major enzymes are required for either de novo methylation (DNMT3A and DNMT3B) or maintenance methylation (DNMT1) in mammalian cells (10).

Understanding DNA methylation marks and their biological regulation is crucial to understanding and targeting DNA methylation–associated changes. In the last decade, unprecedented advances have been made in the development of new technologies to advance the study of DNA methylation. Here, we review these technological advances and provide examples of their adaptation to genome-wide DNA methylation profiling and also discuss a newly identified DNA methylation mark, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), and speculate on its possible biological function. Finally, we describe a newly developed method, single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, that can unambiguously identify 5hmC marks.

Methods to distinguish 5mC from cytosine

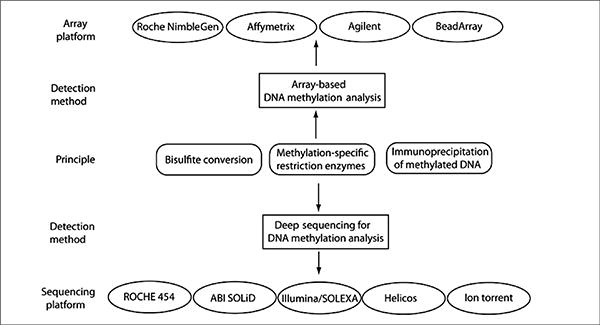

In this section, we discuss four major methods that are routinely used for distinguishing the DNA methylation mark 5-methylcytosine (5mC) from unmethylated cytosine (C). Many of these methods have been adapted for array-or sequencing-based genome-scale DNA methylation analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methods for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis.

Bisulfite-converted DNA, DNA methylation–specific immunoprecipitation methods, and DNA partitions generated by methylation-specific restriction enzymes can be used for both array-based and high-throughput deep sequencing–based genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. There are several different choices for both array platforms and sequencing technologies that can be used for DNA methylation analysis.

Restriction endonuclease–based analysis

Restriction endonucleases are arguably one of the most powerful tools in molecular biology. Due to the versatility of many restriction enzymes and their lack of the activity or selectivity toward methylated DNA, these enzymes have been adapted to discriminate methylated DNA from unmethylated DNA (11–15). The two most commonly used pairs of isoschizomers in restriction endonuclease–based DNA methylation analysis are HpaII-MspI, which recognize CCGG, and SmaI-XmaI, which recognize CCCGGG. While both pairs recognize the same restriction sites, neither HpaII nor SmaI can digest methylated DNA. Another enzyme that has become popular for DNA methylation analysis is McrBC (16,17). McrBC only cleaves DNA containing methylcytosine (5mC, 5hmC, or N4-methylcytosine) and shows no activity toward unmethylated DNA. McrBC recognizes two half sites of the form (G/A)mC. Although these half sites can be as far as 3 kb apart, the optimal distance is 55–103 bp (16).

Initially, restriction endonucleases were limited to the study of DNA methylation patterns within individual genomic regions, but in recent years, the approach has been adapted for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. Several recent studies have used restriction endonucleases along with deep sequencing to obtain useful biological information (14,18). It is important to note, however, that restriction endonuclease–based methods for DNA methylation analysis are limited by the availability of restriction enzyme sites in the target DNA.

Bisulfite conversion of DNA

Treatment of the DNA with sodium bisulfite, under the treatment conditions, leads to the conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil, while methylated cytosine (both 5mC or 5hmC) remains unchanged (19). This change in the DNA sequence following bisulfite conversion can be detected using a variety of methods, including PCR amplification followed by DNA sequencing. It is safe to say that the use of bisulfite-converted DNA for DNA methylation analysis has surpassed almost every other methodology for DNA methylation analysis, thereby becoming the gold standard for detecting changes in DNA methylation. Over the past several years, numerous methodologies have been developed that rely on the use of bisulfite-converted DNA (20–22). These methods have not only been used to detect changes in gene- or allele-specific DNA methylation, but they have also been adapted for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis and are capable of providing DNA methylation information at single-nucleotide resolution (9,23).

Immunoprecipitation-based methods

5mC marks and the proteins that selectively bind5mC—such as MeCP2 and MBD2—can be detected using specific antibodies. This information has allowed the development of immunoprecipitation-based methods for DNA methylation analysis (24,25). These methods are relatively straightforward and do not require either digestion of genomic DNA or bisulfite treatment. Also, since there is no chemical conversion of epigenetic information to genetic information, as in the case of bisulfite conversion, downstream data processing does not require reference bisulfite-converted genomes. Thus, immunoprecipitation-based methods generate data that is relatively easier to analyze and interpret. Due to the ease of these methods over bisulfite conversion–based methods, several studies have used immunoprecipitation-based approaches for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis (6,24,25). However, it is important to note that, unlike bisulfite conversion–based methodologies, immunoprecipitation-based methods do not provide DNA methylation information at single-nucleotide resolution.

Mass spectrometry-based methods

Mass spectrometry is based on the principle that a charged particle passing through a magnetic field is deflected along a circular path on a radius that is proportional to the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Since mass spectrometry has proved extremely useful and reliable for acquiring molecular information, it has been adapted for DNA methylation analysis. One such adapted mass spectrometry platform is MassARRAY EpiTYPER (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA). MassARRAY EpiTYPER uses base-specific enzymatic cleavage coupled to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis (26). Mass spectrometry–based methods can be adapted for DNA methylation analysis of a large set of genes. For example, EpiTYPER can analyze nearly 6000 different DNA samples per day; however, mass spectrometry has not been a method of choice for genome-wide, high-resolution surveys due to the limited throughput and high cost for performing large-scale DNA methylation analysis.

Array-based genome-wide DNA methylation analysis

Array-based platforms for methylation analysis rely on three basic techniques: (i) restriction digestion, (ii) affinity purification, and (iii) bisulfite sequencing. Array-based methodologies have evolved to enable genome-scale DNA methylation analysis through advances in methylation detection methods, as well as development of new high-density arrays. Table 1 provides a comparison of various array platforms along with features specific to each platform.

Table 1. Comparison of different array platforms for DNA methylation analysis.

| Roche NimbleGen | Affymetrix | Agilent | Illumina Arrays | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array types | Whole-genome, promoter, or custom arrays | Whole-genome, promoter, or custom arrays | Whole genome arrays, subgenome arrays, tiling arrays | HumanMethylation27 panel, Golden-Gate Methylation Cancer Panel, Sentrix Array Matrix BeadArray |

| Recommended methods for sample preparation | MeDIP, MIRA, restriction enzymes | MeDIP, MBD-immunoprecipitation bisulfite treatment | MeDIP, MBD-immunoprecipitation | Bisulfite conversion |

| Throughput | Genome-wide | Genome-wide | Genome-wide | Custom defined CpG island analysis |

| Accuracy | “Highly sensitive detection” due to the use of isothermal (50- to 75-mer) oligonucleotide probes | “Highly sensitive” with a low incidence of false positive | “Sensitive measurement” of weak and infrequent binding events as well as direct comparison of samples of the same microarray | 99.9% |

| Limit of detection | Can detect 2 CpG dinucleotide in a 500-bp fragment | N.A. | N.A. | Can detect as little as 17% difference in DNA methylation and can detect as little as 2.5% DNA methylation |

| Data analysis software | NimbleScan (for data extraction), M-Peak (for DNA methylation data analysis) | Tiling analysis software (TAS) | Agilent genomic workbench and feature extraction software | Genome Studio Data Analysis Software |

| Overall validation in a secondary DNA methylation analysis assay | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | High number of loci validates in the secondary assay (MS-PCR) [Spearman correlation coefficient (r) = 0.70] |

N.A., information not available.

Roche NimbleGen arrays

NimbleGen (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) provides several different array platforms for DNA methylation analysis as well as custom arrays that have been used to analyze DNA methylation on a genome-wide scale (25,27,28). Recently, a comprehensive high-throughput array-based relative methylation (CHARM) analysis was performed to examine variation in the DNA methylation patterns between normal and cancerous tissue samples and between human and mouse tissue samples (27). This study used a custom-designed NimbleGen HD2 microarray that included all classically defined CpG islands as well as nonrepetitive lower CpG density genomic regions. For each sample, ∼4.5 million CpG sites were analyzed. This study revealed several new trends in DNA methylation, including (i) most tissue-specific methylation occurs in CpG island shores rather than at CpG islands; (ii) tissue-specific differentially methylated regions are highly conserved in human and mouse; (iii) DNA methylation was sufficiently conserved to completely discriminate tissue types, independent of species of origin; and (iv) at least in case of colon cancer, differential methylation also corresponds to tissue-specific differential methylation and involves CpG island shores (27). These results indicate that genome-wide surveys of the CpG island regions alone might not reveal differentially methylated regions and that CpG island shores should also be analyzed. Additionally, gene ontology analysis suggested that changes in DNA methylation were most prominent in developmentally regulated and pluripotency-related genes; thus the results of this study provide further support for the epigenetic progenitor model of cancer (27), which suggests that cancer arises due to epigenetic regulation of tissue-specific differentiation-associated genes (29).

Affymetrix arrays

As indicated in Table 1, Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) also provides several array platforms that have been used in a number of methylation studies. Using the Arabidopsis tiling 1.0 array from Affymetrix, one group described a method called bisulfite methylation profiling (BiMP) (30). This method showed improved sensitivity and resolution over the traditional methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) method (30). In addition, the method is more economical and requires only 100 ng Arabidopsis DNA. According to Reinders et al., the major advance with the BiMP approach is the reduced amplification bias in the bisulfite-converted DNA, which enables preparation of genome-wide probes for high-density tiling arrays (30). Since a small amount of DNA can be used for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis using BiMP, this approach provides a new opportunity for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis from small tissue samples or analysis of DNA methylation during embryogenesis.

Agilent arrays

Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) array platforms have now been used to study DNA methylation and methylation-associated changes in several organisms (31–34). In a recent study, researchers performed a genome-wide screen to identify frequently methylated genes in hematological and epithelial cancers. This study used the methylated CpG island recovery assay (MIRA) (35) in combination with a human genome-wide CpG island array from Agilent to identify epigenetic molecular markers in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) on a genome-wide scale. Using an Agilent array with 237,220 probes covering 27,800 CpG islands, this study reported the identification of 30 genes demonstrating DNA methylation frequencies of >25% in childhood leukemia. When the leukemic cells were treated with the DNMT inhibitor 5aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5Aza2dC), expression for several of these genes was restored (34). In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), two of the identified genes (TFAP2A and EBF2) showed increased DNA methylation in blast crisis compared with chronic phase (34). Interestingly, 10 out of the 30 genes identified from the genome-wide screen were also methylated in epithelial cancers, suggesting that similar pathways might operate across different tumor types to cause cancer (34). This study underpins the common epigenetic changes shared among widely different human tumors and emphasizes the need to identify common epigenetic changes that can be targeted, possibly by a universal epigenetic therapy. In fact, synthetic lethality RNA interference (RNAi) screens that targeted a cancer-associated genetic change have validated the feasibility of such an approach, wherein knockdown of a single gene was able to inhibit Ras mutant cancer cells independent of their tissue of tumor origin (36–38). Now, it is just a matter of time before similar approaches will be tried for cancer-associated epigenetic changes (39).

Illumina BeadArray technology

Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) BeadArrays provide one of the most advanced array-based approaches for both custom and large-scale DNA methylation analysis and have been used by multiple investigators for addressing DNA methylation–related questions (40–44). One of the initial publications that used the Illumina platform for DNA methylation analysis did so by using the GoldenGate genotyping assay implemented on a BeadArray platform (40). This study analyzed the methylation status of 1536 specific CpG sites in 371 genes in a single reaction by multiplexed genotyping of bisulfite-treated DNA. After the validation of this assay in cell lines and normal tissues, a panel of lung cancer samples was analyzed, and a molecular DNA methylation–based signature was obtained that could distinguish lung adenocarcinoma from normal lung tissues with high specificity (40). The method, described by Bibikova et al., could detect as little as 2.5% methylation for CpG dinucleotides. Unlike restriction endonuclease–based methods, the BeadArray enables probes to be specifically designed for most CpG sites in the genome and requires only 200 ng genomic DNA (40). In the future, this technology might be useful in identifying DNA methylation signatures in different cancers as well as other pathological conditions.

Advantages and drawbacks of array-based methodologies

Compared with deep sequencing approaches, a major advantage to using array-based platforms for DNA methylation analysis is the ease of performing such experiments, even for those with limited expertise. The data obtained from array-based platforms is also easier to interpret through the use of many well-characterized software programs, which can both be learned and implemented with limited computational skills.

However, compared with deep-sequencing approaches, array-based platforms suffer from several drawbacks: (i) arrays have lower resolution; (ii) DNA methylation is often found in repetitive sequences of the mammalian genome, and array-based analysis is based on hybridizations (therefore, designing probes that can specifically distinguish one repetitive element from other in a hybridization-based method is not easy); and (iii) since arrays lack representation for the DNA methylation of repetitive genomic regions, they are therefore not truly genome-wide surveys.

Genome-scale DNA methylation analysis using deep sequencing

High-throughput, next-generation deep sequencing technologies have revolutionized research in biological science in the post-human genome sequencing era. These technologies provide an opportunity to rapidly analyze the genome of any organism. Table 2 describes several important features of the current next-generation deep sequencing platforms. For a detailed overview of these systems, refer to an excellent review by Michael L. Metzker on next-generation deep sequencing technologies (45).

Table 2. Comparison of different high-throughput deep sequencing technologies.

| Roche/454 | Illumina/SOLEXA | ABI SOLiD | Polonator | Heliscope | Ion Torrent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method for Sequencing | Polymerase (pyrosequencing) | Polymerase (reversible terminator) | Ligase (octomer) | Ligase (nonamer) | Polymerase (single molecule) | Polymerase (single molecule) |

| Template amplification method | Emulsion PCR | Bridge PCR | Emulsion PCR | Emulsion PCR | None (single molecule) | None (single molecule) |

| Throughput | 400–600 MB | 17 GB | 10–15 GB | ∼10 GB | 21–28 GB | 100 MB |

| Run time | 10 h | 4 daysa | 7 daysa | 4 days | 8 days | 1–2 h |

| Read length | ∼400 bp | ∼40 bpb | ∼50 bp | ∼15 bp | ∼30 bp | 100–200 bp |

| Accuracy | 99.74% | 99.99% | 99.7% | 98% | 99% | >99.995% |

| Cost | $60.0/MB | $2.0/MB | $2.0/MB | $1.0/MB | $1.0/MB | $500/run |

Number of days required for single end reads.

Paired-end reads can provide DNA sequence information for up to 80 nucleotides.

Adaptation of DNA methylation detection technologies for high-throughput deep sequencing

Most deep sequencing technologies provide very short DNA sequence reads, which makes genome-scale alignments and the data analysis quite challenging. Apart from generating short reads, these methodologies produce terabyte-size data files; development of appropriate computational resources and bioinformatics tools has thus become of the utmost importance. In order to solve this problem, many software programs have been developed to facilitate alignment, assembly, and visualization of next-generation DNA sequence data (Table 3). In this section, we discuss a few representative studies that analyze changes in global patterns of DNA methylation using deep sequencing technologies.

Table 3. Computational programs available for analysis of data generated by high-throughput sequencing.

| Software/programs | Web address/availability | Features |

|---|---|---|

| CLC Genomics Workbench | www.clcbio.com/index.php (commercial) |

|

| Galaxy | http://main.g2.bx.psu.edu (academic, freely available) |

|

| Genomatix genome analyzer | www.genomatix.de/en/produkte/genomatix-genome-analyzer.html (commercial) |

|

| NEXTGENe | http://softgenetics.com/NextGENe.html (commercial) |

|

| SeqMan NGen | www.dnastar.com/t-products-seqman-ngen.aspx (commercial) |

|

| RMAP | http://rulai.cshl.edu/rmap (academic, freely available) |

|

| ELAND | www.illumina.com (commercial) |

|

| Exonerate | www.ebi.ac.uk/∼guy/exonerate (academic, freely available) |

|

| SSAHA2 | www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/ssaha (academic, freely available) |

|

| Edena | www.genomic.ch/edena (academic, freely available) |

|

| SHARCGS | http://sharcgs.molgen.mpg.de (academic, freely available) |

|

| EagleView | http://bioinformatics.bc.edu/marthlab/EagleView (academic, freely available) |

|

Methylation-specific restriction enzyme digestion combined with high-throughput sequencing

Restriction enzyme–based techniques, depending on the type of the enzyme used for restriction digestion, can either enrich for methylated or unmethylated DNA sequences. The most commonly used restriction endonucleases for DNA methylation analysis were described in the “Restriction endonuclease–based analysis” section. Many studies have applied methylation-specific restriction endonucleases to high-throughput deep sequencing for methylation analysis (14,46).

A recent analysis performed by Edwards et al. adapted restriction endonucleases to what was described as methylation mapping analysis by paired-end sequencing (Methyl-MAPS) (14). The authors analyzed the status of >275 million CpG sites in human and mouse DNA from breast and brain tissues, achieving 82.4% coverage of CpG dinucleotides in the genome. For Methyl-MAPS, methylated compartments of the genome were isolated by digestion with five restriction endonucleases, while the unmethylated compartments were isolated by limited digestion with the McrBC enzyme. The results indicated that DNA methylation is the default state for CpG dinucleotides in the mammalian genome, and the presence of histone variants, or histone modification, shields most of the promoter-associated CpG islands from DNMTs (14). This study is of special interest to those profiling the DNA methylation status at repetitive genomic regions, since this was not previously possible using traditional array-based techniques or with several other versions of deep sequencing–based DNA methylation profiling. Thus, Methyl-MAPS has emerged as a new advance for genome-wide analysis for DNA methylation.

High-throughput deep sequencing of bisulfite-converted DNA

The most robust method, by far, for studying cytosine covalent modification is bisulfite conversion followed by massive high-throughput DNA sequencing. After the bisulfite sequencing, the genome is largely composed of only three nucleotides (A, G, and T); therefore the downstream analysis requires two reference genomes, of which one should represent an in silico mimic of the bisulfite conversion. Thus, data analysis is very cumbersome and requires highly trained bioinformaticians, biostaticians, and specialized analysis software. In this section, we describe several landmark studies that have put bisulfite-converted DNA in combination with high-throughput sequencing at the forefront of the DNA methylation analysis.

Roche/454 sequencing of bisulfite-converted DNA

Changes in DNA methylation patterns have been associated with tumorigenesis and other biological processes. A recent study using Roche/454 pyrosequencing-based massively parallel bisulfite pyrosequencing analyzed breast cancer tissue and sera for changes in DNA methylation (47). This analysis focused on four genomic regions where the authors had previously identified aberrant methylation at high frequency in breast cancer tissues. After analyzing DNA methylation in >700,000 DNA fragments derived from 50 cancer and cancer-free individuals, the authors concluded that no tumor-specific DNA methylation pattern could be identified from the four loci tested. While the levels of DNA methylation varied among tumor samples, little variation was found among normal samples, leading the authors to speculate that this could be of biological significance and that this scenario could be due to loss of yet-unidentified surveillance mechanisms in cancer cells. The study also provided an advance in the development of sera-based and cancer-specific DNA methylation biomarker discovery tools, thus indicating that similar nonbiopsy-based analysis can be performed for other cancers (47).

SOLiD sequencing of bisulfite-converted DNA

ABI SOLiD (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) has also been adapted for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. SOLiD technology differs from other high-throughput deep sequencing approaches, as it detects two nucleotides at a time by ligation and predicts one of the four colors associated with those specific two bases. Bromann et al. (48) assessed the capabilities of the ABI SOLiD approach for large-scale bisulfite sequencing and generated two libraries (in-solution bisulfite-converted and gel bisulfite-converted library) from Escherichia coli DH10B. These libraries were then amplified on magnetic beads by emulsion PCR (ePCR) using the standard SOLiD protocol, with the exception that additional dATP and dTTP were added to the aqueous ePCR phase to compensate for the low complexity of the bisulfite-converted libraries (48). Interestingly, this study indicated the advantage of bisulfite color versus base space sequencing, a finding that could assist in the analysis of more complex mammalian genomes, such as humans.

Illumina sequencing of bisulfite-converted DNA

Information on DNA methylation patterns can be acquired by sequencing bisulfite-converted DNA for a single genomic locus. For genome-wide analysis, many modified versions of the standard bisulfite sequencing have been developed. Using one such modification called reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), Meissner et al. performed a genome-scale DNA methylation analysis comparing mouse pluripotent stem cells to differentiated cells (23). Using high-throughput RRBS and the Genome Analyzer (Illumina), the authors generated DNA methylation maps covering most of the CpGs in the mouse genome, along with a representative sampling of conserved noncoding elements, transposons, and other genomic features. The results of this study demonstrated that DNA methylation patterns are dynamic and undergo global changes when pluripotent stem cells differentiate. Based on histone methylation analysis, the authors also found that DNA methylation is better correlated with histone methylation than any other underlying genomic feature (23). This study establishes RRBS as a new methodology that can be applied to the study of DNA methylation in several different biological systems.

A more recent study has taken genome-wide DNA methylation to the next level (49). Lister et al. examined DNA methylation changes in the floral tissue of Arabidopsis thaliana by deep sequencing the bisulfite-converted genome using a sequencing-by-synthesis approach, a technique the authors referred to as Methyl-C. A similar analysis of DNA methylation patterns in primary human fibroblasts, human pluripotent, and differentiated cells using Methyl-C led to the identification of many new features of DNA methylation (9), including large-scale non-CpG methylation in pluripotent stem cells, which was lost in differentiated cells. This indicated that non-CpG DNA methylation might be associated with stem cell pluripotency (9). This study is remarkable for several reasons. First, this approach provided CpG methylation data at a single base pair resolution. Second, the study generated 178 gigabases of the sequence, which is the equivalent of sequencing the entire human genome 57 times. Finally, the results indicated that brute force bisulfite sequencing on this scale was required to predict DNA methylation at 94% of the CpG islands in the human genome, since bisulfite-converted sequence reads are inherently difficult to map.

DNA methylation–specific affinity purification method with high-throughput sequencing

Due to the specific chemical structure of 5mC and the proteins that specifically recognize and bind to this covalently modified DNA nucleotide, several rapid affinity-based methylated DNA enrichment methods have been developed. These enrichment approaches have also been adapted for high-throughput deep sequencing analysis.

Recently, a study performed 5mC immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (MeDIP-seq) to analyze eight breast cancer cell lines along with normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC). The study also investigated changes in MCF7 cells during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (50) and found massive hypomethylations in breast cancer cell lines compared to normal human mammary epithelial cells. Interestingly, these regions of hypomethylation were localized to the CpG-poor regions. This study also indicated that although DNA hypomethylation was not associated with any distinct genomic features, hypermethylated regions were most commonly present in the CpG-rich areas, although these were not dependent on their distance from transcription start sites. With regard to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions, the authors found that 40% of the epithelial cell type–specific genes were altered by DNA methylation compared with those specific to mesenchymal transition, further establishing the role of DNA methylation in regulation of cell type–specific transcriptional gene regulation (50).

Analysis of high-throughput deep sequencing data

High-throughput DNA sequencing platforms are fast, reliable, and relatively affordable systems for obtaining genome-wide information at single-nucleotide resolution. Various applications of next-generation sequencing make it an attractive platform for addressing a wide variety of biological questions. As described earlier in this review, almost every DNA methylation analysis method (restriction endonuclease–based analysis, immunoprecitipitation, bisulfite sequencing) has been adapted to generate libraries for high-throughput deep sequencing analysis of DNA methylation.

However, there are several challenges to obtaining highly reproducible data, and the data analysis can be difficult to perform. Thus, these technologies are generally not preferred if a project requires only small-scale, low-resolution sequence information. Also, due to lack of universal software for efficient and appropriate data management, downstream processing and analysis of the terabyte-sized data sets generated during each run becomes extremely difficult. Table 3 lists some commonly used software programs for the analysis, alignment, assembly, and visualization of deep sequencing data sets.

Most studies described in this review developed their own custom-made programs for sequence analysis. To illustrate the range of data analysis approaches, Table 4 summarizes analysis methods used in six studies involving three of the most commonly used sequencing platforms (Roche/454, ABI SOLiD, and Illumina/SOLEXA). In the future, developing unified data analysis pipelines will be very important, as this will allow reproducible analysis of genome-scale DNA methylation data across laboratories.

Table 4. Summary of data and statistical analysis methods used by different genome-wide high-throughput deep sequencing DNA methylation studies.

| Sequencing platform | Aim of the study | Methods for sequencing data analysis and statistical analysis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roche/454 | Analysis of global DNA methylation in the tissue and the sera of breast cancer patients. | The data and efficacy of bisulfite mutagenesis for this study was analyzed using MethylMapper. The data set was also examined to ensure that each amplicon and each patient had balanced representation. t tests and discriminant analysis were performed to identify significantly changed amplicons in cancer-free versus cancer samples. All the statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) software. | [48] |

| Analysis of global CpG island methylation of sperm and female white blood cells. | The data was first preprocessed to remove all the sequences that had adaptor sequence. The remaining sequences were then mapped using VerJInxer software (http://verjinxer.googlecode.com). For mapping of the CpG island-enriched fragments, a CpG island reference sequence was generated by extracting CpG island sequences and defined by the UCSC browser from the repeat-masked human genome reference sequence. | [18] | |

|

| |||

| ABI SOLiD | Evaluating the utility of SOLiD for bisulfite-sequencing large and complex genomes. | First, two bisulfite reference genomes were created by in silico replacment of all Cs with Ts in both DNA strands of DH10B genome. Sequence reads were then aligned to both bisulfite-converted reference genomes and to the normal DH10B genome using the SOLiD System Analysis Pipeline Tool (http://solidsoftwaretools.com/gf/project/corona), allowing up to five mismatches per read. | [49] |

| Development of a method (Methyl-MAPS) that can globally detect DNA methylation status for both unique and repetitive DNA sequences. | Initial tag mapping was performed using SOLiD System Analysis Pipeline Tool. Paired-end tags were each individually mapped in color space, allowing up to two mismatches in each 25-bp tag to the human hg18 sequence obtained from the UCSC genome browser. A custom Pearl script was used for further identifying the methylated versus unmethylated regions in the sequences. CpG island, RepeatMasker, and RefSeq gene data were all downloaded from the UCSC genome browser. Each CpG island was annotated according to its genomic location. Promoter islands were defined as islands that occur within 1 kb of a gene transcription start site. | [14] | |

|

| |||

| Illumina/SOLEXA | Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of pluripotent and differentiated cells. | Sequence reads from bisulfite-converted libraries were identified using standard Illumina base-calling software and analyzed using a custom computational pipeline. | [23] |

| Single-base resolution DNA methylation map of Arabidopsis. | Sequence information was extracted from the image files with the Illumina Firecrest and Bustard applications and mapped to the Arabidopsis (Col-0) reference genome sequence (TAIR 7) with the Illumina ELAND algorithm. Reads were mapped against computationally bisulfite-converted and nonconverted genome sequences. Reads that aligned to multiple positions in the three genomes were aligned to an unconverted genome using cross_match algorithm. To identify the presence of a methylated cytosine, a significance threshold was determined at each base position using the binomial distribution, read depth, and precalculated error rate based on combined bisulfite conversion failure rate and sequencing error. Methylcytosine calls that fell below the minimum required threshold of percent methylation at a site were rejected. This approach ensured that ≤5% of methylcytosine calls were false positives. The authors also developed an open-source web-based application called Anno-J for visualization of genomic data. | [50] | |

| Human DNA methylation analysis at single-base resolution. | MethylC-Seq sequencing data was processed using the Illumina analysis pipeline, and FastQ format reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg18) using the Bowtie alignment algorithm46. The base calls per reference position on each strand were used to identify methylated cytosines at 1% false discovery rate. | [9] | |

Deep sequencing technologies have generated so much data in recent years that the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) now has a portal called Sequence Read Archive (SRA) that acts as a central repository for short read sequencing data, and provides links to other resources referring to or using this data. It also enables retrieval based on ancillary information and sequence comparison. Finally, it establishes the basis for user-interactive submission and retrieval.

5hmC mark

As early as 1970, researchers identified the epigenetic mark 5hmC in the brains and livers of rats, as well as in the brains of both frogs and mice (51). Two recent studies rediscovered this mark in mouse embryonic stem cells and Purkinje neurons (52,53).

Using an approach to identify enzymes that can modify 5mC, Tahiliani et al. (52) identified TET1 and found that overexpression of TET1 led to reduced 5mC. When genomic DNA from mouse embryonic stem cells was analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC), an additionally modified cytosine nucleotide was observed. Using mass spectrometry, Tahiliani and colleagues identified this modified nucleotide as 5hmC. mES cells expressing a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against TET1 led to reduced 5hmC, indicating that TET1 and potentially other members of the TET1 family might be involved in modifying 5mC to 5hmC.

In a second study, Krisaucionis et al. analyzed the DNA methylation in neurons and found the 5hmC mark in Purkinje neurons. Interestingly, the authors found no indication of this modification in cancer cell lines (53).

Speculating on the role of 5hmC

As indicated above, 5hmC has now been detected in a variety of cell types. It is interesting to note, however, that only a subset of 5mC is converted to 5hmC. This raises the possibility that cis-acting elements determine which 5mCs are targeted for conversion to 5hmC. Since there was no indication if the normal or immortalized cancer precursor cells lacked this modification, analysis of this mark during tumor progression might provide insight into the role of this modification in cellular immortalization and transformation. It is important to note that DNMT1 and MeCP2 do not bind to 5hmC; this modification might thus be involved in fine-tuning the transcriptional repression machinery (52). The fact that 5hmC mark is found in embryonic stem cells and neurons—which both have high plasticity—strengthens the hypothesis that 5hmC might be involved in gene expression regulation.

SMRT technology for 5hmC mark detection

After bisulfite treatment, 5hmC, similarly to 5mC, does not convert to uracil; thus, current bisulfite conversion–based methodologies fail to distinguish 5hmC from 5mC (54,55). Although there are methods to detect 5hmC—such as TLC and mass spectroscopy—these approaches cannot be applied for a large-scale detection of 5hmC marks. The studies that identified the 5hmC mark relied on TLC and mass spectrometry techniques. MassARRAY EpiTYPER can also be adapted for semi–high-throughput analysis of 5hmC. Two recent studies indicated that an antibody-based enrichment might also work, because 5mC antibodies do not recognize the 5hmC mark (54,55). In fact, Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA) has recently developed an antibody against 5hmC, which can distinguish 5hmC from 5mC and can now be used for a genome-wide DNA methylation analysis using a method similar to MeDIP in combination with an array-based or deep sequencing–based platform.

Recently, Pacific Biosciences developed SMRT sequencing, which is capable of detecting DNA methylation without the need for bisulfite conversion (56). In SMRT sequencing, DNA polymerase catalyzes the incorporation of fluorescently labeled nucleotides into complementary nucleic acid strands. SMRT sequencing utilizes arrival times and duration of the resulting fluorescence pulse to generate information about polymerase kinetics, which allows direct detection of modified nucleotides in the DNA template. SMRT sequencing was able to detect and differentiate N6-methylcytosine, 5mC, and 5hmC (56). According to Flusberg et al., SMRT sequencing is amenable to long read lengths and will likely enable mapping of DNA methylation patterns in even highly repetitive genomic regions (56).

Conclusions

DNA methylation marks are now established as important regulators of many different biological processes in a wide range of living organisms. For mammals, DNA methylation has been shown to play an important role during embryogenesis and in a variety of pathological conditions (1,3,57). Because of this, a better understanding of the changes in DNA methylation patterns and elucidating the mechanisms of DNA methylation regulation is a very active area of investigation. In the last decade, molecular biology has seen unprecedented expansion of technologies for DNA methylation analysis, which are becoming increasing available and affordable to academic laboratories. This is indicated by the influx of a large number of high-profile publications charting new research avenues and the discovery of very important epigenetic changes that involve covalent modifications of DNA (6,9,14,49).

Specifically, next-generation sequencing technologies are extremely important, since many disease states that are regulated through epigenetic means cannot be identified using regular DNA sequencing that does not enrich the methylated genomic compartment. In the last few years, several organisms and multiple types of cancers have been subjected to large-scale genome-wide DNA methylation analysis (4,6,14); these technologies are also providing the means to understand stem cells, cancer, bacterial virulence, and plant development (6).

Ultimately, there is a need to further develop technologies aimed at understanding the mechanisms and consequences of different DNA methylation–associated changes. The advent of genome-wide RNAi screens now provides such an opportunity. Two studies have exploited the power of genome-wide RNAi-based functional genomics to elucidate DNA methylation regulation by oncogenic RAS or epigenetic regulation of the tumor suppressor RASSF1A (58,59). Similar RNAi screens can now be performed to understand the regulation of numerous epigenetically silenced genes.

Acknowledgments

N.W. is a Yale Cancer Center member. This work is supported in part by start-up funds from the Yale Department of Pathology, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Centennial Career Development Award for Childhood Cancer Research, and a Yale Liver Center Pilot Grant (to N.W.). We regret that not all of our colleagues' work could be cited due to space limitations. We also thank our anonymous reviewers whose suggestions helped us to improve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Low DA, Weyand NJ, Mahan MJ. Roles of DNA adenine methylation in regulating bacterial gene expression and virulence. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7197–7204. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7197-7204.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noyer-Weidner M, Trautner TA. Methylation of DNA in prokaryotes. EXS. 1993;64:39–108. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9118-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finnegan EJ, Genger RK, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. DNA methylation in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:223–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilberman D, Gehring M, Tran RK, Ballinger T, Henikoff S. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methylation uncovers an interdependence between methylation and transcription. Nat Genet. 2007;39:61–69. doi: 10.1038/ng1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finnegan EJ, Kovac KA. Plant DNA methyltransferases. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;43:189–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1006427226972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsahoye BH, Biniszkiewicz D, Lyko F, Clark V, Bird AP, Jaenisch R. Non-CpG methylation is prevalent in embryonic stem cells and may be mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5237–5242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen T, Li E. Structure and function of eukaryotic DNA methyl-transferases. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;60:55–89. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bird AP, Taggart MH, Smith BA. Methylated and unmethylated DNA compartments in the sea urchin genome. Cell. 1979;17:889–901. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones PA, Taylor SM. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell. 1980;20:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatada I, Fukasawa M, Kimura M, Morita S, Yamada K, Yoshikawa T, Yamanaka S, Endo C, et al. Genome-wide profiling of promoter methylation in human. Oncogene. 2006;25:3059–3064. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards JR, O'Donnell AH, Rollins RA, Peckham HE, Lee C, Milekic MH, Chanrion B, Fu Y, et al. Chromatin and sequence features that define the fine and gross structure of genomic methylation patterns. Genome Res. 2010;20:972–980. doi: 10.1101/gr.101535.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadri R, Hornsby PJ. Rapid analysis of DNA methylation using new restriction enzyme sites created by bisulfite modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:5058–5059. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart FJ, Raleigh EA. Dependence of McrBC cleavage on distance between recognition elements. Biol Chem. 1998;379:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart FJ, Panne D, Bickle TA, Raleigh EA. Methyl-specific DNA binding by McrBC, a modification-dependent restriction enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:611–622. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeschnigk M, Martin M, Betzl G, Kalbe A, Sirsch C, Buiting K, Gross S, Fritzilas E, et al. Massive parallel bisulfite sequencing of CG-rich DNA fragments reveals that methylation of many X-chromosomal CpG islands in female blood DNA is incomplete. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1439–1448. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark SJ, Harrison J, Paul CL, Frommer M. High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2990–2997. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber M, Davies JJ, Wittig D, Oakeley EJ, Haase M, Lam WL, Schubeler D. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:853–862. doi: 10.1038/ng1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koga Y, Pelizzola M, Cheng E, Krauthammer M, Sznol M, Ariyan S, Narayan D, Molinaro AM, et al. Genome-wide screen of promoter methylation identifies novel markers in melanoma. Genome Res. 2009;19:1462–1470. doi: 10.1101/gr.091447.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehrich M, Nelson MR, Stanssens P, Zabeau M, Liloglou T, Xinarianos G, Cantor CR, Field JK, van den Boom D. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15785–15790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruzov A, Savitskaya E, Hackett JA, Reddington JP, Prokhortchouk A, Madej MJ, Chekanov N, Li M, et al. The non-methylated DNA-binding function of Kaiso is not required in early Xenopus laevis development. Development. 2009;136:729–738. doi: 10.1242/dev.025569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinders J, Delucinge Vivier C, Theiler G, Chollet D, Descombes P, Paszkowski J. Genome-wide, high-resolution DNA methylation profiling using bisulfite-mediated cytosine conversion. Genome Res. 2008;18:469–476. doi: 10.1101/gr.7073008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rauch TA, Pfeifer GP. The MIRA method for DNA methylation analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;507:65–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-522-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill VK, Hesson LB, Dansran-javin T, Dallol A, Bieche I, Vacher S, Tommasi S, Dobbins T, et al. Identification of 5 novel genes methylated in breast and other epithelial cancers. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:51. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grafodatskaya D, Choufani S, Ferreira JC, Butcher DT, Lou Y, Zhao C, Scherer SW, Weksberg R. EBV transformation and cell culturing destabilizes DNA methylation in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genomics. 2010;95:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunwell T, Hesson L, Rauch TA, Wang L, Clark RE, Dallol A, Gentle D, Catchpoole D, et al. A genome-wide screen identifies frequently methylated genes in haematological and epithelial cancers. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauch T, Pfeifer GP. Methylated-CpG island recovery assay: a new technique for the rapid detection of methylated-CpG islands in cancer. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1172–1180. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scholl C, Frohling S, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Barbie DA, Kim SY, Silver SJ, Tamayo P, et al. Synthetic lethal interaction between oncogenic KRAS dependency and STK33 suppression in human cancer cells. Cell. 2009;137:821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, Wong KK, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthusamy V, Bosenberg M, Wajapeyee N. Redefining regulation of DNA methylation by RNA interference. Genomics. 2010 Jul 8; doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bibikova M, Lin Z, Zhou L, Chudin E, Garcia EW, Wu B, Doucet D, Thomas NJ, et al. High-throughput DNA methylation profiling using universal bead arrays. Genome Res. 2006;16:383–393. doi: 10.1101/gr.4410706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suhr ST, Chang EA, Rodriguez RM, Wang K, Ross PJ, Beyhan Z, Murthy S, Cibelli JB. Telomere dynamics in human cells reprogrammed to pluripotency. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, Pan F, Pelloski CE, et al. Identification of a CpG island methylator phenotype that defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rakyan VK, Down TA, Maslau S, Andrew T, Yang TP, Beyan H, Whittaker P, McCann OT, et al. Human aging-associated DNA hypermethylation occurs preferentially at bivalent chromatin domains. Genome Res. 2010;20:434–439. doi: 10.1101/gr.103101.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, Morgan M, Hutchison K, Calhoun VD. A study of the influence of sex on genome wide methylation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oda M, Glass JL, Thompson RF, Mo Y, Olivier EN, Figueroa ME, Selzer RR, Richmond TA, et al. High-resolution genome-wide cytosine methylation profiling with simultaneous copy number analysis and optimization for limited cell numbers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3829–3839. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korshunova Y, Maloney RK, Lakey N, Citek RW, Bacher B, Budiman A, Ordway JM, McCombie WR, et al. Massively parallel bisulphite pyrosequencing reveals the molecular complexity of breast cancer-associated cytosine-methylation patterns obtained from tissue and serum DNA. Genome Res. 2008;18:19–29. doi: 10.1101/gr.6883307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bormann Chung CA, Boyd VL, McKernan KJ, Fu Y, Monighetti C, Peckham HE, Barker M. Whole methylome analysis by ultra-deep sequencing using two-base encoding. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lister R, O'Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, Gregory BD, Berry CC, Millar AH, Ecker JR. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruike Y, Imanaka Y, Sato F, Shimizu K, Tsujimoto G. Genome-wide analysis of aberrant methylation in human breast cancer cells using methyl-DNA immunoprecipitation combined with high-throughput sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penn NW, Suwalski R, O'Riley C, Bojanowski K, Yura R. The presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in animal deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J. 1972;126:781–790. doi: 10.1042/bj1260781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcy-tosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, Pastor WA, Shen Y, Tahiliani M, Liu DR, Rao A. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nestor C, Ruzov A, Meehan R, Dunican D. Enzymatic approaches and bisulfite sequencing cannot distinguish between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in DNA. BioTechniques. 2010;48:317–319. doi: 10.2144/000113403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flusberg BA, Webster DR, Lee JH, Travers KJ, Olivares EC, Clark TA, Korlach J, Turner SW. Direct detection of DNA methylation during single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Nat Methods. 2010;7:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Balaraman Y, Wang G, Nephew KP, Zhou FC. Alcohol exposure alters DNA methylation profiles in mouse embryos at early neurulation. Epigenetics. 2009;4:500–511. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.7.9925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gazin C, Wajapeyee N, Gobeil S, Virbasius CM, Green MR. An elaborate pathway required for Ras-mediated epigenetic silencing. Nature. 2007;449:1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/nature06251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palakurthy RK, Wajapeyee N, Santra MK, Gazin C, Lin L, Gobeil S, Green MR. Epigenetic silencing of the RASSF1A tumor suppressor gene through HOXB3-mediated induction of DNMT3B expression. Mol Cell. 2009;36:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]