Abstract

Objectives. We assessed news media framing of New York City’s proposed regulation to prohibit the sale of sugar-sweetened beverages greater than 16 ounces.

Methods. We conducted a quantitative content analysis of print and television news from within and outside New York City media markets. We examined support for and opposition to the portion-size cap in the news coverage from its May 31, 2012, proposal through the appellate court ruling on July 31, 2013.

Results. News coverage corresponded to key events in the policy’s evolution. Although most stories mentioned obesity as a problem, a larger proportion used opposing frames (84%) than pro-policy frames (36%). Mention of pro-policy frames shifted toward the policy’s effect on special populations. The debate’s most prominent frame was the opposing frame that the policy was beyond the government’s role (69%).

Conclusions. News coverage within and outside the New York City media market was more likely to mention arguments in opposition to than in support of the portion-size cap. Understanding how the news media framed this issue provides important insights for advocates interested in advancing similar measures in other jurisdictions.

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption has increased concurrent with obesity and continues to represent a large source of added sugar in the US diet.1,2 In response to rising SSB consumption, US cities and states have considered implementing various strategies—including legislation and regulation.3,4 Strategies directed at SSB consumption have largely focused on limiting the availability of these products in specific environments (e.g., schools) or by imposing taxes on SSBs.5 Another recent policy example is New York City’s SSB portion-size cap.6

In January 2012, the New York City Mayor’s Office convened a task force to develop obesity prevention and control strategies.6 On May 31, 2012, the task force announced the SSB portion-size cap, a proposed regulation that would amend the New York City Health Code, restricting portions greater than 16 ounces of select SSBs from being sold in restaurants, food carts, convenience stores, and movie theaters.7 The regulation included nonalcoholic beverages with more than 25 calories per 8 ounces and those with less than 50% milk or milk substitute.7 The New York City Board of Health adopted it on September 13, 2012.8 It was challenged by a lawsuit brought by organizations representing racial/ethnic minority groups and labor and business associations in October 2012.9 A New York state court forbade its enforcement on March 12, 2013, 1 day before its scheduled implementation.9 An appellate court upheld the decision on July 30, 2013.10 New York’s highest court invalidated the policy on June 26, 2014.11

Consistent with the New York City portion-size cap experience, jurisdictions throughout the United States have faced difficulty implementing food and beverage policies. One factor that influences policy development and enactment is framing in the news media.12,13 Framing involves “selecting some aspects of a perceived reality and making them more salient . . . to promote a particular problem definition . . . or treatment recommendation.”14(p52) As illustrated in tobacco and alcohol control,15–20 framing can be strategically used in political debates to influence the views of decision-makers and the public.21 The volume of news coverage and framing are important before and during consideration of a policy change.16–20,22 The amount of attention and the nature of how an issue is covered by the media have been shown to both hinder and promote policy enactment16–20 with 1 study finding that lack of voter support for a tobacco tax was associated with news coverage.19

Framing in the news media can shape opinions of appropriate solutions for public health problems such as obesity.13,23 However, little is known regarding the framing of policies directed at adult SSB consumption. Niederdeppe et al. explored the arguments surrounding SSB taxes in the news media and found that the news source was associated with the proportion of pro- versus anti-tax arguments, with local outlets less likely than national outlets to include anti-tax arguments.24 In addition, Democrat-endorsing newspapers were more likely to cover SSB taxes than were Republican-endorsing newspapers.24

To date, no study has examined news coverage of an SSB portion-size cap policy. To fill this gap, we collected and analyzed news media coverage of New York City’s policy. Specifically, we examined how the news media described the portion-size cap policy, the use of supportive and opposing frames, and whether use of these frames shifted over time. Finally, we examined framing by different stakeholders.

METHODS

We conducted a quantitative content analysis to examine news media framing between May 31, 2012, and July 31, 2013, on the New York City restriction on the sale of SSBs greater than 16 ounces. Sources from the New York news media market included 5 regionally focused newspapers (New York Times, New York Post, Wall Street Journal, New York Daily News, and Newsday) and transcripts from evening news programs on 4 New York City broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox). News sources from outside the New York market included 18 newspapers from across the United States (USA Today, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Denver Post, Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, Orange County Register, Newark Star-Ledger, Tampa Bay Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Philadelphia Inquirer, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Phoenix Republic, Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Las Vegas Review-Journal, and Boston Globe) and transcripts from evening news programs on 3 national television networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS). We used data from the Alliance for Audited Media to identify newspapers with the highest circulation rates.25

News Coverage Selection

We identified print news and non–New York City television coverage by using LexisNexis, ProQuest, and Factiva databases. We used ShadowTV to collect New York City television transcripts.26 In our searches, we used the terms “New York,” “New York City,” “soft drink,” “sugary beverage,” “soda,” “sugary drink,” “soda pop,” “sugar-sweetened beverage,” “ban,” “policy,” “regulation,” and “restriction.”

We chose the study period to reflect the issue’s political evolution. Included news coverage began on May 31, 2012, the day that the proposal was announced.6 We conducted a week look-back of news coverage to confirm that there was not previous coverage. Because an appellate court upheld the decision to halt the policy’s implementation on July 30, 2013,11 the last date of publication for included stories was July 31, 2013.

After the database searches were complete, we removed duplicate news stories. We included stories if their primary focus was the portion-size cap (i.e., we included news stories if they discussed the New York City policy alone or if it was used as a primary example to discuss the government’s role in public health). We excluded news stories if they discussed a similar policy in another jurisdiction (e.g., a portion-size restriction in Cambridge, MA). We included and classified news stories, editorials, syndicated columns, and guest columns according to story type including news, op-ed or editorial, sports, health, or lifestyle. We excluded stories if they comprised fewer than 90 words or were letters to the editors, obituaries, or advertisements. With these exclusion criteria, we retained 263 news stories.

Content Analysis

We developed a 46-item coding instrument to assess the presence or absence of supportive (pro) and opposing (con) portion-size cap frames in the news coverage. Pro frames are arguments in support of the policy, such as it will reduce SSB consumption. Con frames are opposing arguments, such as it will unfairly hurt small businesses, with any mention of the word fairness, equity, discrimination, or related term coded in reference to the disproportionate economic impact. We identified the frames contained in the coding instrument through a qualitative review of a random sample of 15 articles within the New York City regional news outlets. Two coders (E. A. D. and P. L. T.) pilot tested the instrument by using a random sample of stories from news outlets not included in this study. We adjusted instrument wording, developed a codebook to clarify coding guidelines (e.g., example frames and definitions), and further refined the instrument with pilot testing. We managed the instrument and data in Qualtrics Research Suite 2015 (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

We double-coded 55% of the 263 articles (n = 145) to produce intercoder reliability statistics.27 Item-specific raw agreement ranged from 80.7% to 100%. The κ statistics ranged from 0.60 to 1.00 with an average κ of 0.79. We considered a κ statistic greater than 0.6 as having good agreement and greater than 0.8 as having excellent agreement.27 The κ statistic and raw agreement for each item are provided in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We coded news content across 4 domains. The first domain assessed obesity framing with 4 items. The second domain explored the policy’s characteristics with 6 items. The third domain measured pro-policy frames with 10 items and the fourth domain assessed con-policy frames with 26 items. The exact wording for all items is provided in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Data Analysis

The unit of analysis was the story. We calculated descriptive statistics to examine whether news coverage differed in print versus television news, by the political leaning of print sources based on their 2012 presidential endorsement, and across key time periods in the policy debate with control for story word count and adjustment for standard errors for nonindependence of news outlets.

We used an 8-item instrument developed during the qualitative review of articles to identify the stakeholder group(s) that were quoted or paraphrased in the news coverage and to code their messages regarding the policy as pro, con, or neutral or balanced. A single coder (E. A. D.) assessed stakeholder content. We coded stakeholders including individuals and organizations as 1 of the following: government officials, industry representatives, citizens or citizens’ groups, academic researchers, public health representatives, or medical professionals.

RESULTS

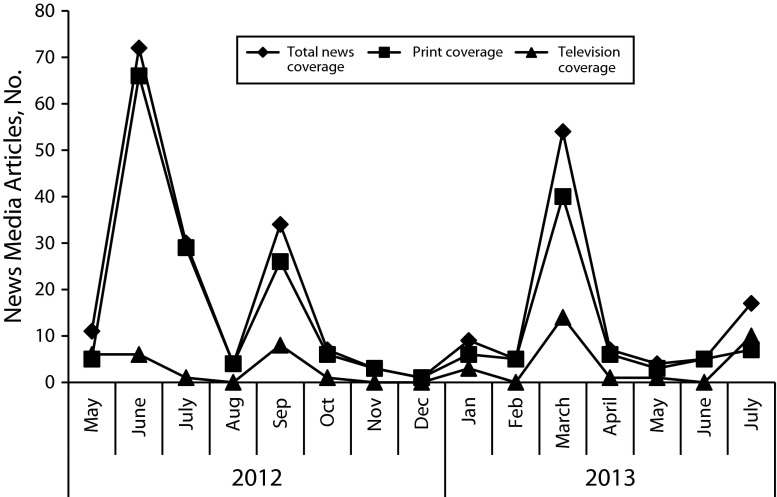

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 263 news stories covering the portion-size cap between May 28, 2012, and July 31, 2013. The majority of the stories were in print news (81%) and in local news sources (72%). Figure 1 indicates the volume of news coverage over the study period. As expected, print news and television coverage were highest following the main events in the regulation’s evolution.

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Characteristics of News Coverage of the New York City Portion-Size Cap Regulation: May 31, 2012–July 31, 2013

| Characteristic | No. (%) or Mean |

| Total news stories | 263 (100.0) |

| NYC news media marketa | 189 (71.9) |

| Non-NYC news media marketb | 74 (28.1) |

| Type of news stories | |

| 212 (80.6) | |

| Television | 51 (19.4) |

| Newspaper story type | |

| News section | 151 (71.2) |

| Op-ed or editorial | 49 (23.1) |

| Sports, health, lifestyle, or other section | 12 (5.7) |

| Word count | |

| Print news stories | 611 |

| Television news stories | 356 |

| Year | |

| 2012 | 162 (61.6) |

| 2013 | 101 (38.4) |

| News story volume before Board of Health vote: portion-size cap proposed by NYC Dept of Health on May 31, 2012, until the Board of Health vote on Sep 13, 2012 | 133 (50.6) |

| News story volume after Board of Health vote | |

| Following the vote through Oct 11, 2012, when the beverage industry filed a petition in court challenging the portion-size cap | 19 (7.2) |

| Following the industry petition until the portion-size cap implementation was halted by a New York state court on Mar 11, 2013 | 42 (15.9) |

| Following the portion-size cap court ruling until the city announced its plan to appeal the ruling on Apr 1, 2013 | 37 (14.1) |

| Following the city’s appeal announcement until the city lost the appeal on Jul 31, 2013 | 32 (12.2) |

Note. NYC = New York City.

NYC news media market outlets included 5 daily newspapers that have a regional focus on NYC (New York Times, New York Post, Wall Street Journal, New York Daily News, and Newsday), and transcripts from evening news programs on 4 local NYC networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox).

Non-NYC news media market outlets included 18 daily newspapers (USA Today, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Denver Post, Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, Orange County Register, Newark Star-Ledger, Tampa Bay Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Philadelphia Inquirer, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Phoenix Republic, Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Las Vegas Review-Journal, and Boston Globe), and transcripts of evening television news programs on 3 national networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS).

FIGURE 1—

News coverage of the New York City sugar-sweetened beverage portion-size cap policy: May 31, 2012–July 31, 2013.

Framing the Problem of Obesity and Portion-Size Cap Characteristics

Table 2 indicates that a majority of news stories framed the issue by mentioning that obesity is a problem (60.5%). Stories before the Board of Health vote were more likely to mention the role of the beverage industry than were stories after the vote (13.5% before vs 5.4% after; P < .05). For example, an industry role observed in stories was that rising obesity is tied to industry supersizing. Stories published after the vote were more likely to mention that the policy did not cover all locations where SSBs are sold (44.6% after vs 30.8% before; P < .05). Also, a greater proportion of stories after the vote mentioned that the aim of the policy was to improve health (57.7% after vs 49.6% before; P < .05). For example, one aim observed was that the policy’s intent was to combat obesity.

TABLE 2—

Proportion of News Coverage Framing the Problem of Obesity and the Characteristics of the New York City Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Portion-Size Cap Regulation: May 31, 2012–July 31, 2013

| Frame Topics Mentioned | Overall % (n = 263) | Before Board of Health Vote,a % (n = 133) | After Board of Health Vote,b % (n = 130) |

| News stories framing the problem of obesity | |||

| Obesity is a problem | 60.5 | 60.9 | 60.0 |

| SSB consumption is a cause of obesity | 27.4 | 31.6 | 23.1 |

| Role of the industry in contributing to SSB consumption or obesity | 9.5 | 13.5 | 5.4* |

| Role of individual choice, behavior, or lifestyles in contributing to SSB consumption or obesity | 13.7 | 16.5 | 10.8 |

| News stories framing characteristics of the SSB portion-size cap | |||

| Aim of the policy is to improve health | 53.6 | 49.6 | 57.7* |

| Policy only includes certain types of beverages | 28.9 | 24.8 | 33.1 |

| Policy only includes certain locations where SSBs are sold | 37.6 | 30.8 | 44.6* |

| Individuals can purchase refills or more than one 16-oz beverage | 28.1 | 33.8 | 22.3 |

| NYC health department has considered or enacted other obesity-specific public health interventionsc | 25.5 | 26.3 | 24.6 |

| NYC health department has considered or enacted other, non–obesity-specific public health interventionsd | 22.4 | 23.3 | 21.5 |

Notes. NYC = New York City; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage.

May 31, 2012, to Sep 13, 2012.

Sep 14, 2012, to Jul 31, 2013.

Other obesity-specific public health interventions include front-of-package labeling, menu labeling, trans-fat bans, and other food policies or programs.

Non–obesity-specific public health interventions include tobacco and alcohol policies and programs, such as smoke-free indoor air restrictions.

*P < .05 indicating frames in news stories that differ significantly across 2 time periods with control for news story word count and adjustment of standard errors for nonindependence of news outlets.

Overall, most stories (83.7%) contained at least 1 con-policy frame whereas about one third (36.1%) included a pro-policy frame (Table 3). Only between 2% and 23% of stories contained a specific pro-policy frame, such as the policy will reduce SSB consumption. By contrast, con frames about the role of government were included in 69% of stories. Thirty-nine percent of stories mentioned that the policy infringed on free choice or consumer rights and 38% noted that the policy was a government “overreach.” When we stratified the coverage by source, television stories were more likely than print to include at least 1 con-policy frame (90.2% vs 82.1%; P < .05); however, the proportion of stories with at least 1 pro-policy frame was not significantly different (41.2% vs 34.9%). There were no differences in the proportion of stories containing at least 1 pro-policy or con-policy frame in newspapers that endorsed the Democrat in the 2012 election versus Republican-endorsing papers (pro: 37.1% vs 35.4%; con: 86.5% vs 75.6%).

TABLE 3—

Proportion of News Coverage With Pro and Con Frames About New York City Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Portion-Size Cap Regulation, May 31, 2012–July 31, 2013

| Frame Topics Mentioned | Overall (n = 263), % | Before Board of Health Vote (n = 133),a % | After Board of Health Vote (n = 130),b % |

| Pro SSB portion-size cap frames | |||

| Any pro SSB portion-size cap frame | 36.1 | 31.6 | 40.8 |

| Policy will have a positive health impact | 23.2 | 24.8 | 21.5 |

| Policy will increase awareness of SSB harms and obesity risk factors | 8.4 | 12.0 | 4.6* |

| Policy will reduce the amount of SSBs consumed | 7.2 | 10.5 | 3.9 |

| Policy will decrease morbidity or mortality from obesity | 11.0 | 6.8 | 15.4 |

| Policy will help special populations | 7.6 | 3.0 | 12.3* |

| Policy could help children and adolescents | 5.3 | 2.3 | 8.5* |

| Policy could help low-income groups and neighborhoods | 2.3 | 0.8 | 3.9 |

| Policy could help racial/ethnic minorities | 1.9 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Policy is part of the government’s role or responsibility | 13.7 | 10.5 | 16.9 |

| Con SSB portion-size cap frames | |||

| Any con-SSB portion-size cap frame | 83.7 | 84.2 | 83.1 |

| Policy is flawed or will be ineffective | 34.2 | 31.6 | 36.9 |

| Flawed policy arguments | |||

| Policy does not cover all types of beverages | 10.3 | 4.5 | 16.2* |

| Policy does not cover all locations where SSBs are sold | 14.8 | 6.8 | 23.1* |

| Individuals can purchase refills | 9.9 | 11.3 | 8.5 |

| Policy will not reduce obesity | 9.9 | 12.0 | 7.8 |

| SSBs do not cause obesity | 3.8 | 6.0 | 1.5* |

| Local economy | |||

| Policy could hurt the local economy | 18.3 | 12.8 | 23.9* |

| Policy will affect small businesses | 12.6 | 8.3 | 16.9* |

| Special populations | |||

| Policy will hurt special populations | 7.2 | 6.0 | 8.5 |

| Story mentions fairness or a related term | 4.9 | 4.5 | 5.4 |

| Policy is not feasible | 33.5 | 18.8 | 48.5* |

| Public does not like the policy | 14.5 | 15.0 | 13.9 |

| Policy is not feasible or will be difficult to enact or implement | 6.1 | 2.3 | 10.0* |

| Policy is illegal, unconstitutional, or “arbitrary and capricious” | 19.0 | 1.5 | 36.9* |

| Policy is not part of the government’s role or responsibility | 68.8 | 71.4 | 66.2 |

| Story mentions free choice, consumer rights, or protection of independence | 38.8 | 45.9 | 31.5* |

| Policy is an overreach or beyond the government’s role or responsibilities | 37.6 | 30.1 | 45.4* |

| Story includes term “nanny” or “nanny state” | 22.1 | 30.1 | 13.9* |

| Policy is a slippery slope | 10.7 | 12.8 | 8.5 |

| Policy is not the best solution | 14.4 | 16.5 | 12.3 |

| Better solutions | |||

| A built environment change | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| A school environment change | 4.2 | 6.0 | 2.3 |

| Neighborhood or community programs | 2.7 | 3.8 | 1.5* |

| Mass media or education campaigns | 6.8 | 7.5 | 6.2 |

| Legislation or regulation | 5.3 | 6.0 | 4.6 |

May 31, 2012, to Sep 13, 2012.

Sep 14, 2012, to Jul 31, 2013.

*P < .05 indicating frames in news stories that differ significantly across 2 time periods with control for news story word count and adjustment of standard errors for nonindependence of news outlets.

When we compared stories before and after the Board of Health vote, the prevalence of pro- or con-policy frames overall was not significantly different. However, the proportion of stories with specific policy frames changed over time. Stories before the vote were more likely to contain a pro-policy frame suggesting that the policy would increase awareness of SSB harms than those after the vote (12.0% before vs 4.6% after; P < .05). By contrast, stories after the vote were more likely to emphasize the policy’s benefits for specific populations, such as addressing the high SSB consumption rates in low-income neighborhoods (12.3% after vs 3.0% before; P < .05). Framing the portion-size cap as a way to help children and adolescents increased from 2% before to 9% after the vote (P < .05).

With regard to con frames, stories after the vote were more likely to note that the policy would not affect health because it did not cover all beverages (16.2% after vs 4.5% before; P < .05) or locations (23.1% after vs 6.8% before; P < .05). Framing the policy as ineffective because SSBs are not a cause of obesity declined slightly over time (6.0% before vs 1.5% after; P = .05). Con-policy frames about the policy’s potential negative economic impact increased after the vote (23.9% after vs 12.8% before; P < .05) as did mentions of the policy’s negative impact on small businesses (16.9% after vs 8.3% before; P < .05). Legal and implementation concerns were also raised more frequently after the vote (48.5% after vs 18.8% before; P < .05). Framing around the role of government remained high and did not significantly differ over time. A greater proportion of stories before the vote mentioned that the policy would limit free choice (45.9% before vs 31.5% after; P < .05) or used the terms “nanny” or “nanny state” (30.1% before vs 13.9% after; P < .05). By comparison, stories after the vote were more likely to note that the policy was beyond the government’s role (45.4% after vs 30.1% before; P < .05). Lastly, 4% of stories before the vote mentioned that a community or neighborhood program would be better than the policy compared with 2% after the vote (P < .05).

Stakeholder Groups and Opinions

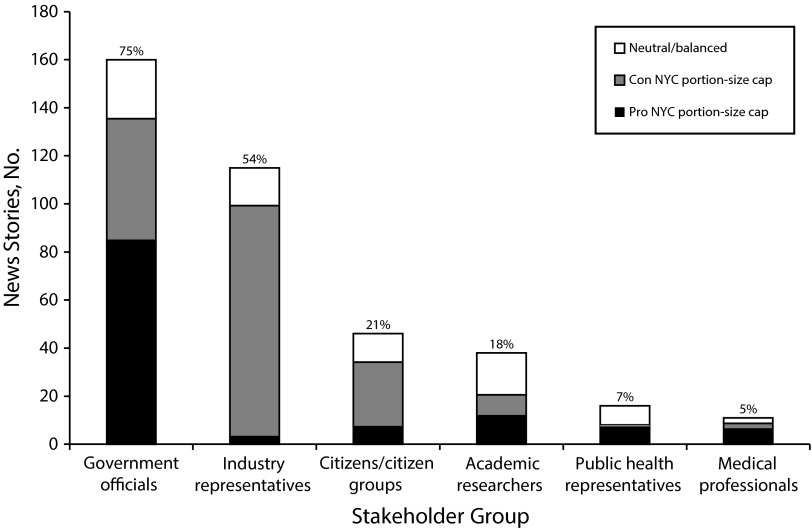

Half of the stories presented both pro-policy and con-policy stakeholder opinions (51%) with 28% providing only con-policy stakeholders and 21% only pro-policy stakeholders. As Figure 2 indicates, 75% of the stories quoted or paraphrased government officials and 54% included industry representatives. Health interest groups and medical professionals were the least represented with 7% and 5% included in the coverage, respectively.

FIGURE 2—

News coverage with pro and con stakeholder quotes about the New York City (NYC) sugar-sweetened beverage portion-size cap policy: May 31, 2012–July 31, 2013.

A slight majority of the government and medical professionals were supportive of the policy, whereas industry representatives and citizens were largely opposed. Public health representatives (50%) and academic researchers (45%) had the largest proportion of quotes that were balanced or neutral.

DISCUSSION

This study highlights the role of the news media in framing a novel policy debate. The analysis found largely negative framing of the New York City SSB portion-size cap in the news media with limited coverage of the policy’s health benefits, framing that paralleled the ongoing legal challenge, and a primary focus on the government’s role in public health.

In contrast to the only other news media content analysis focused on SSB policy,24 the majority of portion-size cap stories included con-policy frames and did not include a health benefit frame. Niederdeppe et al. found that SSB tax coverage included more pro- than anti-tax arguments with an overwhelming majority of national print and television stories containing a pro-tax argument.24 Also, most stories provided a health argument supporting a tax whereas less than one quarter of stories in this study mentioned a portion-size cap health benefit.24 The increasing use of con frames about the portion-size cap’s flaws, as well as the limited number of pro-policy health and medical stakeholders, may have weakened the pro-health frame over time. By contrast, industry stakeholders were prevalent in the news coverage and were unified in their opposition.

The portion-size cap’s introduction in New York City could have influenced the news coverage. For example, New York City has a history of considering and enacting novel public health policies28 that may have affected the news coverage. It is also possible that because the policy had not been tried elsewhere, the lack of evidence about its potential effectiveness contributed to the limited pro-policy framing. An evidence base emerged during policy consideration that included studies with mixed findings on the portion-size cap’s potential health effect.29–31

One possible reason that the news coverage of the portion-size cap was so negative could be the ongoing legal challenge. We selected the New York City Board of Health vote as a key transition in the analysis on the basis of the hypothesis that moving from consideration of the policy to facing its impending implementation and addressing ongoing legal challenges would alter framing. The findings indicate that the framing shifted coincident with timing of the vote and the filing of a lawsuit.

Con-policy frames focused more on economic, legal, and implementation concerns after the vote, and the proportion of stories that mentioned that the policy would affect small business owners, many of whom are minorities, doubled.32 Furthermore, the policy was framed as flawed because it would not cover all locations where SSBs are sold. This framing may have reflected the position of minority groups and small business organizations in the lawsuit that argued they would lose profits because large chains were exempt.9

In contrast to the negative frames regarding the policy’s impact on small businesses, including minority owners, framing how the policy would benefit minority communities and low-income neighborhoods was only included in 2% of stories. Therefore, despite the disproportionate impact of obesity on these communities,33,34 supporters of the policy were unable to successfully frame it as part of the solution for addressing obesity-related disparities. Furthermore, the involvement of minority groups with the beverage industry in the lawsuit against the policy was a significant challenge for policy proponents, and was reflected in news media framing. This dynamic was reminiscent of the relationship between these groups and the tobacco industry in early tobacco control efforts.35

Another driver of the negative framing of the portion-size cap in the news coverage was the inclusion of con frames about the role of government. The emphasis before the Board of Health vote was on restrictions in consumer choice, and on the mayor imposing a “nanny state,” which implied paternalism. Following the vote, the framing shifted to the notion that the policy was beyond the government’s role from a legal standpoint. This shift could be a reflection, in part, of the ongoing legal action that questioned whether the New York City Board of Health was the appropriate authority to enact this type of policy.9–11

As this study illustrated, the discourse around the use of policy approaches in public health often focuses on the contrast between individual freedoms and responsibilities, and protecting individuals from being harmed by themselves, other individuals, and the environment.36 Similar to studies of other policy debates over SSBs and smoking,24,37,38 the current findings suggest that news coverage of the policy was largely focused on the government’s intrusion on individual freedom as opposed to a government policy protecting health. Frequently quoted stakeholders were government representatives who supported the policy and industry representatives who opposed it. This reflected the rhetorical debate regarding the government’s role in protecting public health and perceived infringement on consumer freedom.

The observed framing shifts could have influenced the ongoing debate among policy elites and the public. As illustrated by tobacco tax studies, the nature of coverage and timing of frame changes are important for public support, as well as successful passage.19,39 Public support for the portion-size cap may have been stronger if news coverage had framed a clear need to protect individuals from environmental harms, or harms imposed by individuals or groups.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. This study included broadcast television news and newspapers. We excluded certain types of news coverage from the analysis including cable television news and news blogs, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings to these sources. Second, the ShadowTV database used to identify New York City television transcripts did not consistently attribute stakeholder quotations; therefore, those quotes (n = 25) were unable to be coded.

Third, the stakeholder analysis should be considered exploratory because these items were coded by a single reviewer. Single-reviewer coding is not preferable because it is difficult to catch errors and bias may be introduced because of the unique ways a coder evaluates the data. Fourth, the citizens’ groups could have included industry-funded groups, thereby influencing the perspectives of this category. Fifth, using a quantitative approach restricted the study of frame components, such as exploring the use of metaphor.13

Finally, this analysis used the news media to represent framing. The frames may reflect editorial opinions and societal values.37 Although news media may not be the most comprehensive source of data on framing, it offers a way to characterize what decision-makers are exposed to when a policy is proposed.36,374

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the content of news media coverage of the New York City portion-size cap debate from 2012 to 2013. Although previous studies have explored the effect of the news media on policy enactment,16–20,22 we focused on the debate surrounding the consideration, initial passage, and legal action that prevented a policy’s implementation. Therefore, the current findings offer a unique exploration of framing during an ongoing policy debate and emphasize that the bulk of coverage was dedicated to con-policy frames. Future qualitative research should consider how coverage of the portion-size cap may influence other policy actions in New York City and throughout the country.

The current analysis of a novel policy intervention may be useful to advocates in developing effective strategies for influencing the framing of future policy debates in news media coverage. The findings suggest that portion-size cap proponents should have clearly and repeatedly emphasized the policy’s health benefits. In addition, the findings suggest that proponents did not sufficiently engage a range of stakeholders, such as disadvantaged groups that may be affected by the policy. Lastly, the findings suggest that the policy’s rationale and the historical role of local government in public health were not articulated by proponents early enough to counter opposing frames about the government’s role. Overall, critically considering the role of news media framing in characterizing a policy debate and promoting or inhibiting policy action is critical when one is developing interventions to address the ongoing obesity epidemic.

Acknowledgments

E. A. Donaldson receives support for her doctoral training from a National Cancer Institute grant (T32 CA009314) and the Center for a Livable Future–Lerner Fellowship.

Human Participant Protection

This study was determined to be exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health institutional review board (00000287).

References

- 1.Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):372–381. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(3):726–734. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremers S, Reubsaet A, Martens M et al. Systematic prevention of overweight and obesity in adults: a qualitative and quantitative literature analysis. Obes Rev. 2010;11(5):371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestle M, Jacobson MF. Halting the obesity epidemic: a public health policy approach. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(1):12–24. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreyeva T, Long MW, Brownell KD. The impact of food prices on consumption: a systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):216–222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reversing the epidemic. the New York City Obesity Task Force plan to prevent and control obesity. 2012. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/om/pdf/2012/otf_report.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2014.

- 7.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Board of Health. Notice of adoption of an amendment (81.53) to article 81 of the New York City Health Code. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/notice/2012/notice-adoption-amend-article81.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2014.

- 8.Grynbaum MM. Health panel approves restriction on sale of large sugary drinks. New York Times. September 13, 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/nyregion/health-board-approves-bloombergs-soda-ban.html. Accessed May 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of Commerce et al. v New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene et al., WL 1343607 (NY Sup 2013), NY Slip Op 30609(U) (Trial Order).

- 10. Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of Commerce et al. v. New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene et al., 110 AD 3d 1 (NY App Div 2013).

- 11. Matter of New York Statewide Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of Commerce et al. v New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene et al., 23 NY 3d 681 (2014).

- 12.Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: a strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(3):293–317. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry CL, Brescoll VL, Brownell KD, Schlesinger M. Obesity metaphors: how beliefs about the causes of obesity affect support for public policy. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):7–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menashe CL, Siegel M. The power of a frame: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues—United States, 1985–1996. J Health Commun. 1998;3(4):307–325. doi: 10.1080/108107398127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holder HD, Treno AJ. Media advocacy in community prevention: news as a means to advance policy change. Addiction. 1997;92:S189–S199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson PD, Wasserman J, Raube K. The politics of antismoking legislation. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1993;18(4):787–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood EM, Witson JC, Fan DP, Wagenaar AC. Media advocacy and underage drinking policies: a study of Louisiana news media from 1994 through 2003. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(3):246–257. doi: 10.1177/1524839905276079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JK, Shelton SC, Moreland-Russell S, Luke DA. Tobacco coverage in print media: the use of timing and themes by tobacco control supporters and opposition before a failed tobacco tax initiative. Tob Control. 2010;19(1):37–43. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asbridge M. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman S, Lupton D. The Fight for Public Health: Principles and Practice of Media Advocacy. London, England: BMJ Publishing Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible? Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry CL, Jarlenski M, Grob R, Schlesinger M, Gollust SE. News media framing of childhood obesity in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):132–145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niederdeppe J, Gollust S, Jarlenski M, Nathanson A, Barry CL. News coverage of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: pro- and anti-tax arguments in public discourse. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):e92–e98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alliance for Audited Media. Top 25 U.S. newspapers for March 2013. Available at: http://www.auditedmedia.com/news/research-and-data/top-25-us-newspapers-for-march-2013.aspx. Accessed May 21, 2014.

- 26.Shadow TV. Available at: http://www.shadowtv.com. Accessed May 21, 2014.

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okie S. New York to trans fats: you’re out! N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2017–2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YC, Vine SM. Caloric effect of a 16-ounce (473-mL) portion-size cap on sugar-sweetened beverages served in restaurants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(2):430–435. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.054833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elbel B, Cantor J, Mijanovich T. Potential effect of the New York City policy regarding sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):680–681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1208318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson BM, Stolarz-Fantino S, Fantino E. Regulating the way to obesity: unintended consequences of limiting sugary drink sizes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. Spring 2011. Brooklyn labor market review. Available at: http://www.fiscalpolicy.org/BrooklynLaborMarketReview_FPI_June2011.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2014.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity in K–8 students—New York City, 2006–07 to 2010–11 school years. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(49):1673–1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim S, Harris TG. Neighborhood contributions to racial and ethnic disparities in obesity among New York City adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):159–165. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelley D, Ogedegbe G, Elbel B. Same strategy different industry: corporate influence on public policy. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):e9–e11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frieden TR. Government’s role in protecting health and safety. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1857–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheyne A, Dorfman L, Daynard RA, Mejia P, Gottlieb M. The debate on regulating menthol cigarettes: closing a dangerous loophole vs. freedom of choice. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e54–e61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magzamen S, Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Print media coverage of California’s smokefree bar law. Tob Control. 2001;10(2):154–160. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thrasher JF, Sei-Hill K, Rose I et al. Print media coverage around failed and successful tobacco tax initiatives: the South Carolina experience. Am J Health Promot. 2014;29(1):29–36. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130104-QUAN-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]