Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis K, a member of the Beijing family, was first identified in 1999 as the most prevalent genotype in South Korea among clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis from high school outbreaks. M. tuberculosis K is an aerobic, non-motile, Gram-positive, and non-spore-forming rod-shaped bacillus. A transmission electron microscopy analysis displayed an abundance of lipid bodies in the cytosol. The genome of the M. tuberculosis K strain was sequenced using two independent sequencing methods (Sanger and Illumina). Here, we present the genomic features of the 4,385,518-bp-long complete genome sequence of M. tuberculosis K (one chromosome, no plasmid, and 65.59 % G + C content) and its annotation, which consists of 4194 genes (3447 genes with predicted functions), 48 RNA genes (3 rRNA and 45 tRNA) and 261 genes with peptide signals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40793-015-0071-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Korean Beijing strain, Outbreak, M. tuberculosis K complete genome, TB clinical strain, TB Beijing family

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium responsible for causing tuberculosis, carries the world record for the highest mortality as a single infectious agent. According to a 2014 World Health Organization report, 8.6 million people were estimated to be new TB cases, and approximately 1.3 million people died from TB worldwide [1]. Strains of M. tuberculosis in different geographical locations or populations may have different levels of virulence due to co-evolutionary processes, which consequently leads to varying epidemiological dominance [2, 3].

Among the various M. tuberculosis strains, M. tuberculosis strains belonging to the Beijing genotypes are more prone to induce disease progression and relapse from the latent state [4, 5]. For example, HN878, the causative agent of major TB outbreaks in Texas prisons between 1995 and 1998 [6], belongs to the W-Beijing family, which expresses a highly biologically active lipid species (phenolic glycolipid). HN878 causes rapid progression to death in mice compared to other clinical isolates (CDC1551) or standard laboratory-adapted virulent strains (H37RvT) [7]. In addition, the Beijing genotypes are associated with greater drug resistance than the other M. tuberculosis genotypes [8]. The frequency of Beijing M. tuberculosis is estimated to be 85 to 95 % in South Korea [9]. Recently, the Beijing strains have spread all over the world, including the US, Europe, and Africa, and account for over 13 % of all of the M. tuberculosis strains worldwide [10–12].

Unusually high rates of pulmonary TB occurred in senior high schools in Kyunggi Province in South Korea in 1998 [13]. During the national survey for genotyping analysis of clinical M. tuberculosis isolates in 1999, a single strain with a unique restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profile was the most frequently identified strain [13]. This particular M. tuberculosis K strain phylogenetically belongs to the Beijing genotype and is the most dominant M. tuberculosis strain in South Korea.

M. tuberculosis K replicates rapidly during the early stages of infection in a murine model of TB, causing a more severe pathology and a high level of reactivation from latent infection [14]. In addition, the Bacillus-Calmette-Guérin vaccination is less effective against an M. tuberculosis K infection than H37RvT (unpublished data). These remarkable features of M. tuberculosis K are associated with its high transmissibility and dominance in South Korea. However, the molecular mechanisms of virulence and the pathogenicity-related genetic features of this strain remain unclear. To understand the genomic features of the strain in detail, we sequenced and annotated the complete genome of M. tuberculosis K.

Organism information

Classification and features

A representative genomic rpoB gene of M. tuberculosis K was compared with those obtained using BLASTN [15] with the default settings (only highly similar sequences). The sequence of the single rpoB gene copy was found in the genome. The rpoB gene, which was derived from the M. tuberculosis K genome sequence, showed 99.97 % sequence similarity to the M. tuberculosis H37RvT that was deposited in GenBank (GenBank accession: CP007803.1). We identified only one single-nucleotide polymorphism within the entire rpoB gene (3519 bp) in M. tuberculosis K compared to M. tuberculosis H37RvT (C3225T). M. tuberculosis K shares a high nucleotide sequence similarity with M. tuberculosis H37RvT and other mycobacteria (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic position of M. tuberculosis K in the partial rpoB-based tree. For a more detailed analysis, the whole-genome sequences were used for an average nucleotide identity analysis (Additional file 2: Figure S1). The ANI results showed that M. tuberculosis K belongs to the M. tuberculosis group but is separated from the other M. tuberculosis strains. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of M. tuberculosis K showed 100 % similarity with M. tuberculosis H37RvT.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of M. tuberculosis K according to the MIGS recommendation [16]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [26] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [27] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [28] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [28–31] | ||

| Family Mycobacteriaceae | TAS [28–30, 32] | ||

| Genus Mycobacterium | TAS [30, 33, 34] | ||

| Species Mycobacterium tuberculosis | TAS [35] | ||

| Strain K (CP007803.1) | |||

| Gram stain | Weakly positive | TAS [35] | |

| Cell shape | Irregular rods | TAS [35] | |

| Motility | Non motile | TAS [35] | |

| Sporulation | Nonsporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | TAS [35] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37 °C | TAS [35] | |

| pH range; Optimum | 5.5–8; 7 | IDA | |

| Carbon source | Asparagine, Oleic acid, Potato starch | TAS [14, 35] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human-associated: Human lung | TAS [35] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Normal | TAS [35] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | Aerobic | TAS [35] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Hypervirulent | TAS [14, 35] |

| Biosafety level | 3 | NAS | |

| Isolation | Sputum of TB patient | TAS [35] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | High schools in Kyunggi Province, Republic of Korea. | TAS [35] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1999 | TAS [35] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude Longitude | 37.274377 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 127.009442 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported | NAS |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [36]

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of M. tuberculosis K with other Mycobacterium species based on aligned sequences of the rpoB gene. 711 bp internal region was used for phylogenetic analysis. All sites were informative and there were no gap-containing sites. Phylogenetic tree was built using the Maximum-Likelihood method based on Tamura-Nei model by MEGA. Bootstrap analysis [37] was performed with 500 replicates to assess the support of the clusters. Bootstrap values over 50 are shown at each node. The bar represents 0.02 substitutions per site

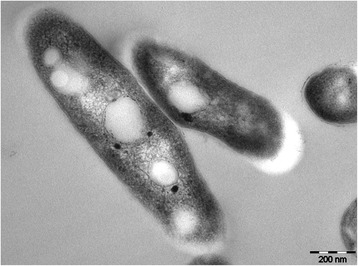

M. tuberculosis K is an aerobic, non-motile rod with a cell size of approximately 0.2–0.5 × 1.0–1.5 μm. It stains weakly positive under Gram staining and contains lipid bodies (Fig. 2). The colonies are slightly yellowish and appear rough and wrinkled on a 7H10-OADC plate (Fig. 3). The viable temperature range for growth is 4–37 °C, with optimum growth at 30–37 °C. The viable pH range is 5.5–8.0, with optimal growth at pH 7.0–7.5.

Fig. 2.

Image of Mycobacterium tuberculosis K using the appearance of colony morphology on 7H10-OADC solid medium

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis K

M. tuberculosis K is resistant to ampicillin, penicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin and tetracycline, but it is susceptible to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, cycloserine, protionamide, amikacin, capreomycin, kanamycin, streptomycin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin and ofloxacin. To investigate the phenotype of M. tuberculosis K, we observed 106M. tuberculosis K bacilli under transmission electron microscopy. Briefly, the immobilized bacteria were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed in 2.0 % paraformaldehyde and 2.0 % glutaraldehyde in 1x PBS with 3 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.2) for at least 1 h at room temperature. The bacterial cells were transferred to propylene oxide and were gradually infiltrated with Spurr’s low-viscosity resin (Polysciences, Warrington, USA): propylene oxide. After three changes in the 100 % Spurr’s resin, the pellets were cured at 60 °C for two days. The sections were cut on an ultramicrotome using a Diatome Diamond knife (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, USA). Eighty-nanometer sections were picked up on formvar-coated 1 × 2-mm copper slot grids and stained with tannic acid and uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate. The grids were examined and photographed using TEM (JEM-1011, JEOL, Japan).

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

Mycobacterium tuberculosis K and the other K-related strains comprise the most dominant genotype of M. tuberculosis in South Korea, but the genomic characteristics and genetic information regarding this strain are still poorly understood. This organism was selected to gain understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of the highly pathogenic and prevalent strain of M. tuberculosis in South Korea.

As the reference strain for studying tuberculosis in Korea, in this study, M. tuberculosis K was selected and sequenced. We used two different next-generation sequencing methods: Sanger and Illumina. The Sanger sequencing was performed at the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Daejeon, South Korea. The NGS sequencing, finishing and genome annotation was performed by ChunLab Inc., Seoul, Korea, and the finished genome sequence and the related data were deposited in GenBank under the accession number CP007803.1. Table 2 presents the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [16].

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: two Sanger libraries; 2 kb shotgun library, fosmid library, respectively and one Illumina library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Sanger, Illumina MiSeq 250 bp paired-end |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 8.3x (Sanger), 551.66x (Illumina) |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Phred/Phrap/Consed, CLC genomics workbench v6.5, CodonCode Aligner v3.7 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Glimmer v 3.02 |

| Locus Tag | MTBK | |

| Genbank ID | CP007803.1 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | June 05, 2014 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0032286 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA178919 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source Material Identifier | The Korean Institution of Tuberculosis |

| Project relevance | Human-associated pathogen |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

M. tuberculosis K was kindly provided by the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis, Seoul, Korea. M. tuberculosis H37RvT, which is stored at the International Tuberculosis Research Centre (ITRC, Masan, South Korea), was also used in this study. M. tuberculosis was cultured aerobically at 37 °C in Middlebrook 7H10 media containing 0.02 % glycerol and 10 % OADC for 4 weeks.

From the M. tuberculosis cultures grown in the 7H10 media for a month, the bacterial DNA was isolated as previously described [17]. In short, the bacilli in suspension were killed by heating at 80 °C for 30 min, and after centrifugation, the cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of TE buffer (0.01 M Tris–HCl, 0.001 M EDTA [pH 8.0]). The cells were treated with lysozyme (1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C, then with 10 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and proteinase K (10 mg/ml) for 10 min at 65 °C prior to the DNA isolation. A total of 80 μl of N-acetyl-N,N,N,-trimethyl ammonium bromide was then added to approximately 500 μl of the lysed cell suspension, and the suspension was vortexed briefly and incubated for 10 min at 65 °C. An equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol) was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 10 s. The solution was then centrifuged for 5 min, and 0.6 volumes of isopropanol were added to the supernatant to precipitate the DNA. After cooling for 30 min at 20 °C, the DNA solution was centrifuged for 15 min, and the pellet was washed once with 70 % ethanol. Finally, the air-dried pellet was redissolved in 50 μl of 0.1x TE buffer and stored at −20 °C until use.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The M. tuberculosis K genome was sequenced at KRIBB (Daejeon, South Korea) and ChunLab Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) using two Sanger libraries (2 kb random shotgun library and fosmid library) and one Illumina library. The random shotgun and fosmid libraries were prepared using the pTZ19U vector and the CopyControl Fosmid Library Production Kit (Epicentre, Madison, USA), respectively. For the Illumina sequencing, the genomic DNA was fragmented using dsDNA fragmentase (NEB, Hitchin, UK) to make it to the proper size for the library construction. The resulting DNA fragments were processed using the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final library was quantified using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA), and the average library size was 300 bp.

The genomic libraries were sequenced via Sanger sequencing on an ABI3730 and an Illumina MiSeq (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA). The generated Sanger sequencing reads (70,889 reads, total read length: 36,413,063 bp) and the Illumina paired-end sequencing reads (10,493,598 reads, total read length: 2,419,306,885 bp) were assembled using the Phred/Phrap/Consed package and CLC Genomics Workbench v6.5 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark). The resulting contigs from the Sanger sequencing of the 2 kb random shotgun library were scaffolded by sequencing the reads from the fosmid clones, and the gaps in the scaffolds were closed using PCR and Sanger sequencing. The contigs and the Sanger sequence reads for the gap closure were combined via manual curation using Phred/Phrap/Consed and CodonCode Aligner 3.7.1 (CodonCode Corp., Centerville, USA). The final genome sequence was reviewed by remapping with the Illumina raw reads and correcting the dubious regions and errors.

Genome annotation

The coding sequences were predicted by Glimmer 3.02 [18]. The tRNAs were identified using tRNAScan-SE [19], and the rRNAs were searched using HMMER with the EzTaxon-e rRNA profiles [20, 21]. The predicted CDSs were compared to catalytic families and NCBI Clusters of Orthologous Groups using rpsBLAST and the NCBI reference sequences SEED, TIGRFam, Pfam, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, COG and InterPro databases, using BLASTP and HMMER for the functional annotation [22–25]. Additional analyses and functional annotations for the genome statistics were performed using the Integrated Microbial Genomes platform.

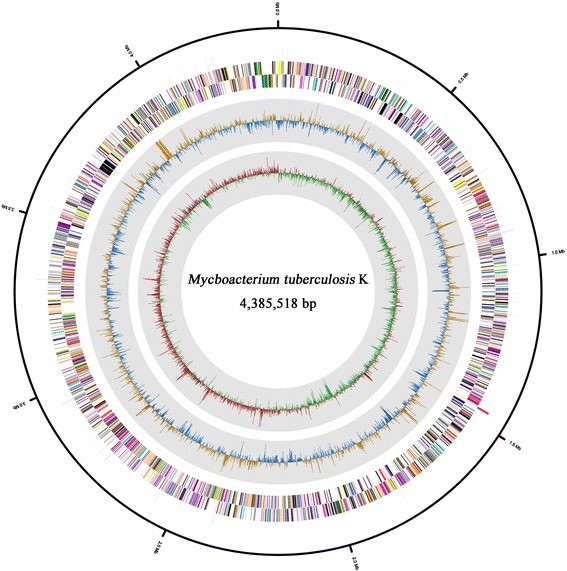

Genome properties

The total length of the complete genome sequence was 4,385,518 bp, and no plasmid was found. The G + C content was determined to be 65.59 %, which is similar to other M. tuberculosis strains (65–66 %) (Fig. 4 and Table 4). Based on the gene prediction results, 4194 CDSs were identified, and 45 tRNAs and 1 rRNA operon were annotated. The total length of the genes was 3,953,484 bp, which makes up 90.15 % of the entire genome. The majority of the genes (82.19 %) were assigned putative functions, while the remaining genes (17.81 %) were annotated as hypothetical. A total of 2610 CDSs were assigned to functional COG groups, 3349 genes were assigned to Pfam domains and 261 genes had signal peptides. The genome properties and statistics are summarized in Table 3. The distributions of the genes among the COG functional categories are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Fig. 4.

Graphical circular map of M. tuberculosis K strain genome. From the outside to the center: RNA features (ribosomal RNAs are colored as blue, and transfer RNAs are colored as red), genes on the forward strand and the reverse strand (colored according to the COG categories). The inner two circles show the GC ratio and GC skew. The GC ratio and GC skew are shown in orange and red indicates positive, and in blue and green indicates negative, respectively

Table 4.

Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,385,518 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 3,954,282 | 90.17 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,876,511 | 65.59 |

| DNA scaffolds | 1 | 100.00 |

| Total genes | 4,194 | 100.00 |

| Protein coding genes | 4,146 | 98.86 |

| Pseudo genes | 2 | 0.05 |

| RNA genes | 48 | 1.14 |

| Genes in internal clusters | NA | NA |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,885 | 68.79 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,892 | 69.74 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 3,347 | 79.80 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 233 | 5.56 |

| Genes coding transmembrane helices | 810 | 19.31 |

| CRISPR repeats | 4 | 0.10 |

The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Also includes 1 pseudogene

Table 3.

Summary of genome: one chromosome and two plasmids

| Label | Size (Mb) | Topology | INSDC identifier | RefSeq ID (Optional) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 4,385,518 | Circular | GenBank | CP007803.1 |

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % age | COG category |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 193 | 4.66 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 10 | 0.24 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 195 | 4.70 | Transcription |

| L | 106 | 2.56 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | – | – | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 37 | 0.89 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | – | – | Nuclear structure |

| V | 84 | 2.03 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 112 | 2.70 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 157 | 3.79 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 8 | 0.19 | Cell motility |

| Z | – | – | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 1 | 0.02 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 23 | 0.55 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 117 | 2.82 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 195 | 4.70 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 139 | 3.35 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 186 | 4.49 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 83 | 2.00 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 225 | 5.43 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 275 | 6.63 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 127 | 3.06 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 107 | 2.58 | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 246 | 5.93 | General function prediction only |

| S | 266 | 6.42 | Function unknown |

| – | 1254 | 30.26 | Not in COGS |

The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Conclusion

M. tuberculosis strains in different populations or geographical locations can exhibit different levels of virulence during the human-adaptation process with consequent varying epidemiological dominance. Importantly, clinical and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the emergence of the Beijing strains may be associated with multi-drug resistance and a high level of virulence, resulting in increased transmissibility and rapid progression from infection to active disease. The M. tuberculosis K strain, which was isolated from an outbreak of pulmonary TB in senior high schools in South Korea, phylogenetically belongs to the Beijing genotype. Here, we present a summary classification and a set of genomic features of M. tuberculosis K together with the description of the complete genome sequence and annotation. The genome of the M. tuberculosis K strain is 4.4 Mbp with a GC content of 65.59 %. M. tuberculosis K genome contains several key virulence factors that are absent in the M. tuberculosis H37RvT genome, such as PE/PPE/PE-PGRS family proteins considered to be involved in granuloma formation and antigenic variations. Further functional analyses of the M. tuberculosis K-specific virulence factors involved in pathogenesis are currently under investigation. These studies may help us to understand the geographical evolution and molecular pathogenesis of this unique genotypic M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (NRF-2013R1A2A1A01009932). We would like to thank Dr. Hong-Seok Park (Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology) for performing the Sanger sequencing.

Abbreviations

- TB

Tuberculosis

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- ANI

Average nucleotide identity

- RFLP

Restriction fragments length polymorphism

Additional files

Associated MIGS record. (DOCX 36 kb)

The genome tree showing the relationships of M. tuberculosis K with other Mycobacterium species based on ANI values. Description of data: To convert the ANI into a distance, its complement to 1 was taken. From this pairwise distance matrix, an ANI tree was constructed using the UPGMA clustering method. (PDF 846 kb)

Footnotes

Seung Jung Han, Taeksun Song and Yong-Joon Cho contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

SJH and TS performed all of the microbiological work and significantly contributed to the writing of the manuscript. SJH, TS, and YJC performed the molecular characterization and all of the bioinformatic analyses, including phylogenetic analysis, the genome assembly, and annotation. TS and YJC significantly contributed to the writing of the manuscript. JSJ and SYC performed all electron microscopy experiments. JC participated in genome sequencing and ensuring quality control of the data. GHB isolated the strain and prepared related clinical information regarding the isolate. SNC participated in the study design and helped to write the manuscript. SJS conceived the study as the supervisor of the project and was responsible for completing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. Global tuberculosis report. WHO report 2014.

- 2.Brown T, Nikolayevskyy V, Velji P, Drobniewski F. Associations between Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and phenotypes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:272–280. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.091032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouwman AS, Kennedy SL, Muller R, Stephens RH, Holst M, Caffell AC, Roberts CA, Brown TA. Genotype of a historic strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18511–18516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209444109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thwaites G, Caws M, Chau TT, D'Sa A, Lan NT, Huyen MN, Gagneux S, Anh PT, Tho DQ, Torok E, et al. Relationship between Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotype and the clinical phenotype of pulmonary and meningeal tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1363–1368. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02180-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong BC, Hill PC, Aiken A, Awine T, Antonio M, Adetifa IM, Jackson-Sillah DJ, Fox A, Deriemer K, Gagneux S, et al. Progression to active tuberculosis, but not transmission, varies by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage in The Gambia. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1037–1043. doi: 10.1086/591504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sreevatsan S, Pan X, Stockbauer KE, Connell ND, Kreiswirth BN, Whittam TS, Musser JM. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9869–9874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barczak AK, Domenech P, Boshoff HI, Reed MB, Manca C, Kaplan G, Barry CE., 3rd In vivo phenotypic dominance in mouse mixed infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:600–606. doi: 10.1086/432006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn JR, Whiteley J, Bifani PJ, Kremer K, van Soolingen D. Worldwide occurrence of Beijing/W strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:843–849. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamputa IC, Lee J, Allix-Beguec C, Cho EJ, Lee JI, Rajan V, Lee EG, Min JH, Carroll MW, Goldfeder LC, et al. Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a tertiary care tuberculosis hospital in South Korea. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:387–394. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02167-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bifani PJ, Mathema B, Kurepina NE, Kreiswirth BN. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parwati I, van Crevel R, van Soolingen D. Possible underlying mechanisms for successful emergence of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:103–111. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Concerted Action on New Generation Genetic Markers and Techniques for the Epidemiology and Control of Tuberculosis Beijing/W genotype Mycobacterium tuberculosis and drug resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:736–743. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SJ, Bai GH, Lee H, Kim HJ, Lew WJ, Park YK, Kim Y. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis among high school students in Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:824–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon BY, Kwak J, Hahn MY, Eum SY, Yang J, Kim SC, Cho SN. In vivo characteristics of Korean Beijing Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain K1 in an aerosol challenge model and in the Cornell latent tuberculosis model. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1373–1379. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrity GM, Holt J. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2001. The Road Map to the Manual; pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stackebrandt ERF, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:479–491. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:589–608. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skerman VBD, Mcgowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Re B. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1917;2:155–164. doi: 10.1128/jb.2.2.155-164.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chester FD. Report of mycologist: bacteriological work. Del Agric Exp Stn Bull. 1897;9:38–145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Runyon EH WL, Kubica GP. Genus I. Mycobacterium Lehmann and Neumann 1896, 363. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE, editors. Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. 8. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co; 1974. pp. 682–701. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann KB KB, Neumann RO. Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik. München: JF Lehmann; 1896. pp. 1–448. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Soolingen D, Hermans PW, de Haas PE, Soll DR, van Embden JD. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim OS, Cho YJ, Lee K, Yoon SH, Kim M, Na H, Park SC, Jeon YS, Lee JH, Yi H, et al. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:716–721. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overbeek R, Begley T, Butler RM, Choudhuri JV, Chuang HY, Cohoon M, de Crecy-Lagard V, Diaz N, Disz T, Edwards R, et al. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5691–5702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu C, Zavaljevski N, Desai V, Reifman J. Genome-wide enzyme annotation with precision control: catalytic families (CatFam) databases. Proteins. 2009;74:449–460. doi: 10.1002/prot.22167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Klimke W, Maglott DR. NCBI Reference Sequences: current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D32–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felsenstein D. Confidence limits on phylogenies an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]