Abstract

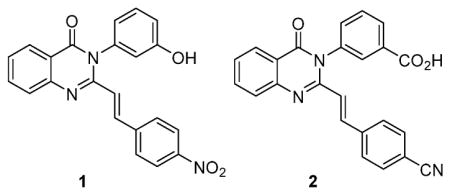

In the face of the clinical challenge posed by resistant bacteria, the present needs for novel classes of antibiotics are genuine. In silico docking and screening, followed by chemical synthesis of a library of quinazolinones, led to the discovery of (E)-3-(3-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (compound 2) as an antibiotic effective in vivo against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). This antibiotic impairs cell-wall biosynthesis as documented by functional assays, showing binding of 2 to penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 2a. We document that the antibiotic also inhibits PBP1 of S. aureus, indicating a broad targeting of structurally similar PBPs by this antibiotic. This class of antibiotics holds promise in fighting MRSA infections.

The emergence of resistance to antibiotics over the past few decades has created a state of crisis in the treatment of bacterial infections.1,2 Over the years, β-lactams were the antibiotics of choice for treatment of S. aureus infections. However, these agents faced obsolescence with the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Presently, vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, or ceftaroline are used for treatment of MRSA infections, although only linezolid can be dosed orally. Resistance to all four has emerged. Thus, new anti-MRSA antibiotics are sought, especially agents that are orally bioavailable. We disclose in this report a new antibiotic (E)-3-(3-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one, with potent activity against S. aureus, including MRSA. We document that quinazolinones of our design are inhibitors of cell-wall biosynthesis in S. aureus and do so by binding to DD-transpeptidases involved in cross-linking of the cell wall. We report that quinazolinones possess activity in vivo and are orally bioavailable. This antibiotic holds promise in treating difficult infections by MRSA.

We used the X-ray structure of PBP2a3 to computationally screen 1.2 million drug-like compounds from the ZINC database4 for binding to the active site using cross-docking with multiple scoring functions. Starting with high-throughput virtual screening, the filtering was stepwise with increasing stringency, such that at each stage the best scoring compounds were fed into the next stage. The final docking and scoring step involved Glide5 refinement of docking poses with the extra precision mode, where the top 2500 poses were clustered according to structural similarity. Of these, 118 high rankers were purchased and tested for antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and the ESKAPE panel of bacteria, comprised of Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acineto-bacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species, which account for the majority of nosocomial infections.1,2,6 Antibiotic 1 was discovered in this effort, with a minimal-inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2 μg/mL against S. aureus ATCC 29213 of the ESKAPE panel. The compound also had modest activity against E. faecium (MIC of 16 μg/mL), but did not have activity against Gram-negative bacteria of our panel. We initiated lead optimization of this structural template to improve its in vitro potency, while imparting in vivo properties. We synthesized 80 analogs of compound 1 and screened them for in vitro antibacterial activity, metabolic stability, in vitro toxicity, efficacy in an in vivo mouse MRSA infection model, and pharmacokinetics (PK).

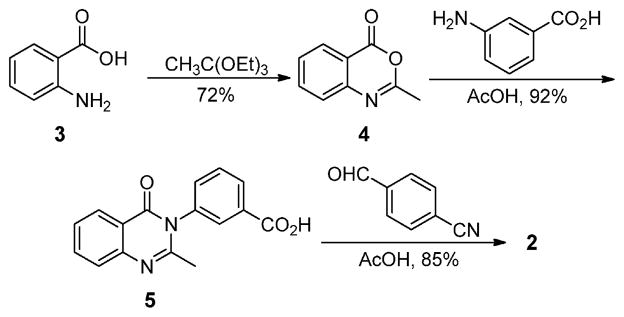

Antibiotic 2 emerged from these studies with the desired attributes, including efficacy in a mouse infection model. Antibiotic 2 was synthesized using a variation of a previously reported method for construction of the quinazolinone core (Scheme 1).7,8 This synthesis uses anthranilic acid (3) as a precursor, which is cyclized to the 2-methylbenzoxazinone intermediate (4) using refluxing triethyl orthoacetate, in 72% yield. The intermediate is then subjected to ring-opening and ring-closing amidation with the corresponding aniline derivative in refluxing acetic acid to give the 2-methylquinazolinone intermediate (5) with a yield of 92%. The final reaction is an aldol-type condensation with the respective aromatic aldehyde to give the 2-styrylquinazolinone product in 85% yield. Antibiotic 2 showed activity against MRSA strains similar to that of linezolid and vancomycin. Furthermore, activity was documented against vancomycin- and linezolid-resistant MRSA strains (Table 1). In the XTT cell proliferation assay using HepG2 cells, antibiotic 2 had an IC50 of 63 ± 1 μg/mL, a value well above the concentration range that manifested the antibacterial activity. We also showed that the antibiotic was not an alkylating agent (Figure S1), did not form glutathione adducts, and showed no hemolysis (<1%) of red blood cells at 50 μg/mL, indicating that the compound was not toxic at concentrations in which antibacterial activity was documented. Furthermore, antibiotic 2 was stable in mouse plasma (half-life of 141 h) and was metabolically stable in rat and human S9 (100% of 2 remaining after 1-h incubation), liver fractions containing microsomes (including cytochrome P450 enzymes capable of phase I metabolism), and cytosol (containing transferases capable of phase II metabolism). In addition, human plasma protein binding was determined to be 96.5 ± 0.7%. Antibiotic 2 in its sodium salt form is water-soluble, with a high solubility of 8 mg/mL.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Quinazolinone 2

Table 1.

A Comparison of the in Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Antibiotic 2 to Marketed Antibiotics against a Panel of Staphylococcal Strainsa

| 2 | vancomycin | linezolid | oxacillin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus ATCC 29213b | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 |

| S. aureus NRS128c | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| S. aureus NRS70d | 2 | 1 | 1 | 32 |

| S. aureus NRS123e | 2 | 1 | 2 | 32 |

| S. aureus NRS100f | 16 | 2 | 2 | 512 |

| S. aureus NRS119g | 8 | 2 | 32 | 512 |

| S. aureus NRS120g | 8 | 2 | 32 | 512 |

| S. aureus VRS1h | 16 | 512 | 2 | 512 |

| S. aureus VRS2i | 2 | 64 | 2 | 256 |

| S. epidermidis ATCC 35547 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 128 |

| S. hemolyticus ATCC 29970 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.25 |

In vitro activity reported as minimal-inhibitory concentration (MIC) in μg/mL.

Quality control methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strain.

MSSA strain, mecA negative, resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, and penicillin.

Clinical MRSA strain isolated in Japan, mecA positive, resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, oxacillin, and penicillin.

Community-acquired MRSA strain, mecA positive, resistant to methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin, and tetracycline.

MRSA strain, mecA positive, resistant to oxacillin, penicillin, and tetracycline.

Clinical MRSA strain, mecA positive, resistant to linezolid, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Clinical MRSA isolate from Michigan, mecA positive, vanA positive, resistant to vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, and penicillin.

Clinical MRSA isolate from Pennsylvania, mecA positive, vanA positive, resistant to vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, and penicillin.

Quinazolinone 2 demonstrated excellent in vivo efficacy in the mouse peritonitis model of MRSA infection,9 with a median effective dose (ED50, the dose that results in survival of 50% of the animals) of 9.4 mg/kg after intravenous (iv) administration (Figure S2). After a single 10 mg/kg iv dose of 2, plasma levels of 2 were sustained above MIC for 2 h and declined slowly to 0.142 ± 0.053 μg/mL at 24 h (Figure S3). The compound had a volume of distribution of 0.3 L/kg (Table S1), a long elimination half-life (>20 h), and low clearance of 6.87 mL/min/kg, less than 10% of hepatic blood flow in mice. After a single 10 mg/kg oral (po) dose of 2, a maximum concentration of 1.29 μg/mL was achieved at 1 h. The terminal half-life was long (>20 h), and the absolute oral bioavailability was 50% (Table S1).

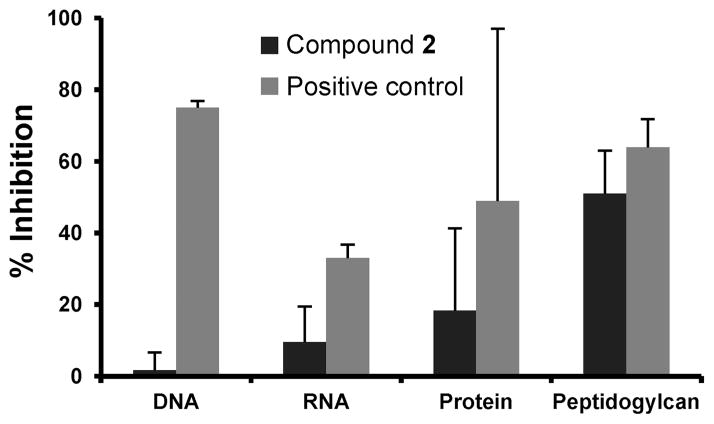

The mode of action of 2 was investigated by macromolecular synthesis assays with S. aureus ATCC 29213 (an MSSA strain) in the logarithmic phase,10 which monitor incorporation of radiolabeled precursors [methyl-3H]-thymidine, [5,6-3H]-uri-dine, L-[4,5-3H]-leucine, or D-[2,3-3H]-alanine into DNA, RNA, protein, or cell wall (peptidoglycan), respectively. Inhibition of radiolabeled precursor incorporation by antibiotic 2 at a concentration of 0.5 MIC was compared with those of known inhibitors of each pathway (ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, tetracycline, and fosfomycin/meropenem, respectively). As per our design paradigm, antibiotic 2 showed notable inhibition of cell-wall biosynthesis in these assays (51 ± 12% compared to 64 ± 8% for fosfomycin and 61 ± 4% compared to 64 ± 2% for meropenem) and did not significantly affect replication, transcription, or translation (Figures 1, S4, and S5). To further validate these results, additional in vitro transcription and translation assays were performed using a T7 transcription kit and an E. coli S30 extract coupled with a β-galactosidase assay system, respectively. Antibiotic 2 did not show inhibition of either transcription or translation using these assays (Figure S6).

Figure 1.

Macromolecular synthesis assays. Antibiotic 2 at 1/2 the MIC. Positive controls for DNA, RNA, protein, and peptidoglycan synthesis are ciprofloxacin (0.5 μg/mL), rifampicin (8 ng/mL), tetracycline (31 ng/mL), and fosfomycin (16 μg/mL), respectively. The maximum inhibition observed for antibiotic 2 is reported at 120 min of incubation in all cases, except for DNA synthesis, which was at 80 min.

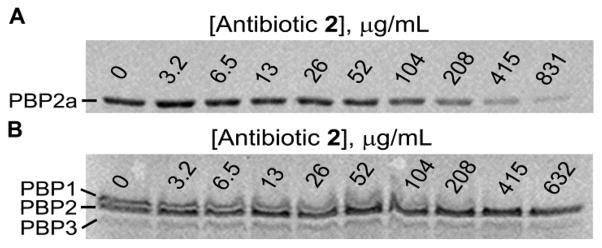

Having demonstrated that biosynthesis of cell wall is attenuated by antibiotic 2, we next explored if it would inhibit purified recombinant PBP2a by a competition assay with Bocillin FL, a cell-wall mimetic fluorescent penicillin reporter reagent.11,12 This inhibition assay for PBPs has a limitation in the fact that Bocillin FL is a covalent modifier of the active site of PBPs and the equilibrium is inexorably in favor of the irreversible acylation of the active-site serine by the reporter molecule. As such, the degree of inhibition by the noncovalent inhibitor (e.g., antibiotic 2) will be underestimated. Antibiotic 2 was able to inhibit Bocillin FL labeling of the active site of PBP2a in a competitive and dose-dependent manner, with an apparent IC50 of 140 ± 24 μg/mL (Figures 2A and S7A). It is important to note that we have observed antibiotic activity for quinazolinone 2 in strains of S. aureus that do not express PBP2a (Table 1), which indicated that the antibiotic is likely to bind to other PBPs as well. This is akin to the case of β-lactam antibiotics, which bind to multiple PBPs due to high structural similarity at the active sites. To demonstrate the ability to bind to other PBPs, membrane preparations of S. aureus ATCC 29213 (the MSSA strain used in the macromolecular synthesis assays) were used to assess broader PBP inhibition by antibiotic 2. Inhibition of PBP1 was observed, with an apparent IC50 of 78 ± 23 μg/mL (Figures 2B and S7B). Inhibition of PBP1 of S. aureus accounts for the antibacterial activity of imipenem and meropenem, two carbapenem antibiotics, in MSSA strains.13,14 However, both antibiotics are ineffective against MRSA. Because of the low-copy numbers of PBP2a in the membranes from MRSA, we could not demonstrate PBP2a inhibition in the membrane preparations directly.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of Bocillin FL binding to S. aureus PBP2a and PBP1. (A) Fluorescence labeling of recombinant purified PBP2a (1 μM) by Bocillin FL (20 μM) in the presence of increasing amounts of antibiotic 2 (μg/mL). (B) Fluorescence labeling of S. aureus membrane preparation (150 μg) by Bocillin FL (30 μM) in the presence of increasing amounts of antibiotic 2 (μg/mL). For data fitting, consult Figure S7.

Targeting of PBP1 and PBP2a by antibiotic 2 was further confirmed by the antisense methodology developed by Merck workers.15 MRSA COL was transformed individually with plasmids bearing antisense fragments for pbpA (encoding PBP1) and pbp2a (encoding PBP2a) under a xylose-inducible promoter. The transcribed antisense fragment under xylose induction binds to the complementary mRNA for the corresponding PBP, which leads to diminution of translation, hence hyper-sensitizing the strain to the antibiotic that targets that given PBP. Attenuation of expression of either PBP1 or PBP2a by this technology sensitized the strain to antibiotic 2, as it did to imipenem and to ceftaroline, known PBP inhibitors (Figure S8).

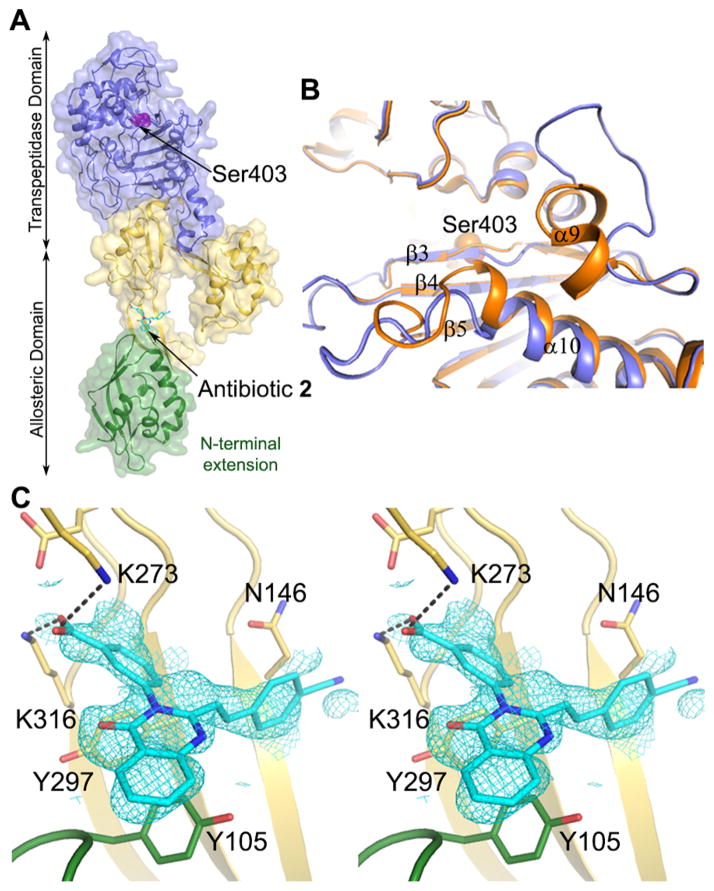

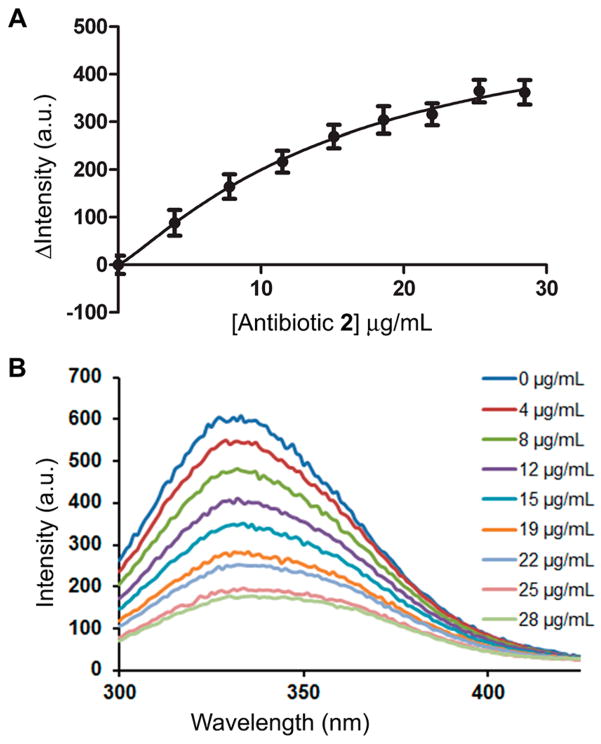

We sought to determine the X-ray structure for the complex of quinazolinone 2 and PBP2a. Soaking experiments of PBP2a crystals with antibiotic 2 resulted in a high-resolution structure at 1.95 Å of resolution for the complex (Table S2). This structure revealed density for antibiotic 2 bound to the allosteric site of PBP2a at a 60-Å distance from the DD-transpeptidase active site (Figure 3). The allosteric site of PBP2a has recently been described.16 The critical binding of ligands such as the nascent cell-wall peptidoglycan at the allosteric site leads to the opening of the active site, enabling catalysis by PBP2a. The structure revealed both alteration of three loops surrounding the active-site pocket, α9-β3, β3-β4, and β5-α10 loops (Figure 3B), and changes in the spatial positions of certain residues (Lys406, Lys597, Ser598, Glu602, and Met641) within the active site of the complex, which could be due to interactions with an antibiotic molecule, but density for it was not observed. The competitive mode of inhibition of Bocillin FL binding to the active site by antibiotic 2 was documented above and is consistent with this scenario. However, some of these alternative active-site conformations could also have come about due to the allosteric triggering. Nevertheless, the antibiotic binding at the allosteric site was unanticipated. Determination of the binding affinity at the allosteric site was performed using intrinsic fluorescence quenching of purified PBP2a, which had been modified covalently within the active site by the antibiotic oxacillin.17 Hence, compound 2 would be expected to bind only to the allosteric site. A Kd of 6.9 ± 2.0 μg/mL was determined (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of S. aureus PBP2a in complex with quinazolinone 2. (A) Ribbon representation of PBP2a showing antibiotic 2 (in cyan for carbons) bound to the allosteric site. The allosteric domain spans residues 27–326, where the N-terminal domain (residues 27–138) is shown in green and the remaining allosteric domain is colored yellow. The transpeptidase domain (residues 327–668) is shown in purple. (B) Ribbon superimposition at the active site of apo PBP2a (PDB ID: 1VQQ) colored in orange and complex colored in purple. Structural changes occur at loops α9-β3, β3-β4, and β5-α10. (C) Key interactions of antibiotic 2 at the allosteric site. Salt-bridge interactions with K273 and K316 are shown as black dashed lines, the distances are 2.9 Å. π-Stacking interactions are observed with Y105 and Y297. Stereoview showing the refined electron density (2Fo − Fc feature-enhanced map) for the ligand (blue mesh) contoured at 1.0 σ.

Figure 4.

Binding of quinazolinone 2 to PBP2a allosteric site, determined using a previously described procedure.17 (A) The change in the maximum fluorescence intensity gave a Kd of 6.9 ± 2 μg/mL (average of three experiments; nonlinear regression for data fitting with an R2 of 0.9997). (B) Emission scans of PBP2a intrinsic fluorescence with excitation at 280 nm. Antibiotic 2 was titrated in to give the final concentrations shown.

Our data can be interpreted as binding of antibiotic 2 both at the active site (competitive inhibition) and at the allosteric site of PBP2a or as binding at the allosteric site with negative allosteric inhibition of the active site of PBP2a. Inhibition of PBP1 is at the active site, as it lacks allosteric regulation. The importance of both PBPs to the mechanism of 2 was validated by the antisense technology. We further provide X-ray crystallography evidence that the antibiotic binds to the allosteric site of PBP2a. These data support PBP inhibition by 2, but they do not exclude the possibility for a pleiotropic effect that could result in inhibition of one or more additional target(s) in S. aureus. However, if the pleiotropic effect exists, it manifests itself in another step of the biosynthesis of cell wall based on the macromolecular synthesis assay results.

In summary, we have described the discovery of a new antibiotic that exhibits in vitro and in vivo activity against S. aureus, and its problematic kin MRSA and its resistant variants to other antibiotics. β-Lactam antibiotics are known inhibitors of PBPs, which are essential enzymes in cell-wall biosynthesis. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is widespread among pathogens, and in the case of MRSA, it encompasses essentially all commercially available drugs.18,19 In light of the fact that quinazolinones are non-β-lactam in nature, they circumvent the known mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. As such, quinazolinones hold great promise in recourse against MRSA as a clinical scourge that kills approximately 20 000 individuals annually in the US alone.20

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.B. was supported by Training Grant T32GM075762 and by an individual Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F31AI115851 from the National Institutes of Health and by an American Chemical Society Division of Medicinal Chemistry Predoctoral Fellowship. The research in Spain was supported by Grants BFU2011-25326 and S2010/BMD-2457. The antisense strains were generous gifts from Dr. Terry Roemer of Merck.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Experimental details, in vitro toxicity, in vivo efficacy, PK data, in vitro transcription and translation assay results, MRSA antisense results, X-ray crystallographic statistics, and regression curves. The crystallographic coordinates are deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 4CJN). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Jr, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellburg B, Bartlett J. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pendleton JN, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:297. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim D, Strynadka NCJ. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:870. doi: 10.1038/nsb858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45:177. doi: 10.1021/ci049714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glide. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice LB. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1079. doi: 10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosley CA, Acker TM, Hansen KB, Mullasseril P, Andersen KT, Le P, Vellano KM, Brauner-Osborne H, Liotta DC, Traynelis SF. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5476. doi: 10.1021/jm100027p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khajavi MS, Montazari N, Hosseini SSS. J Chem Research. 1997;S:286. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross M, Burli R, Jones P, Garcia M, Batiste B, Kaizerman J, Moser H, Jiang V, Hoch U, Duan JX, Tanaka R, Johnson KW. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3448. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3448-3457.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller AA, Bundy GL, Mott JE, Skepner JE, Boyle TP, Harris DW, Hromockyj AE, Marotti KR, Zurenko GE, Munzner JB, Sweeney MT, Bammert GF, Hamel JC, Ford CW, Zhong WZ, Graber DR, Martin GE, Han F, Dolak LA, Seest EP, Ruble JC, Kamilar GM, Palmer JR, Banitt LS, Hurd AR, Barbachyn MR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00247-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao G, Meier TI, Kahl SD, Gee KR, Blaszczak LC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1124. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dzhekieva L, Kumar I, Pratt RF. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2804. doi: 10.1021/bi300148v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Bhachech N, Bush K. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:75. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berti AD, Sakoulas G, Nizet V, Tewhey R, Rose WE. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5005. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00594-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SH, Jarantow LW, Wang H, Sillaots S, Cheng H, Meredith TC, Thompson J, Roemer T. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1379. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otero LH, Rojas-Altuve A, Llarrull LI, Carrasco-Lopez C, Kumarasiri M, Lastochkin E, Fishovitz J, Dawley M, Hesek D, Lee M, Johnson JW, Fisher JF, Chang M, Mobashery S, Hermoso JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fishovitz J, Rojas-Altuve A, Otero LH, Dawley M, Carrasco-Lopez C, Chang M, Hermoso JA, Mobashery S. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9814. doi: 10.1021/ja5030657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S. Chem Rev. 2005;105:395. doi: 10.1021/cr030102i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llarrull LI, Testero SA, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:551. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishbach MA, Walsh CT. Science. 2009;325:1089. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.