Abstract

Both the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and small GTPases of the ADP-ribosylation factors (ARF) family play important roles in regulating cell development, homeostasis and fate. The previous report of QS11, a small molecule Wnt synergist that binds to ARF GTPase-activating protein 1 (ARFGAP1), suggests a role for ARFGAP1 in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. However, direct inhibition of enzymatic activity of ARFGAP1 by QS11 has not been established. Whether ARFGAP1 is the only target that contributes to QS11’s Wnt synergy is also not clear. Here we present structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of QS11 analogs in two assays: direct inhibition of enzymatic activity of purified ARFGAP1 protein and cellular activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The results confirm the direct inhibition of ARFGAP1 by QS11, and also suggest the presence of other potential cellular targets of QS11.

Keywords: Wnt/β-catenin signaling, ADP-ribosylation factors, GTPase-activating proteins, QS11, Structure- activity relationship (SAR)

Graphical abstract

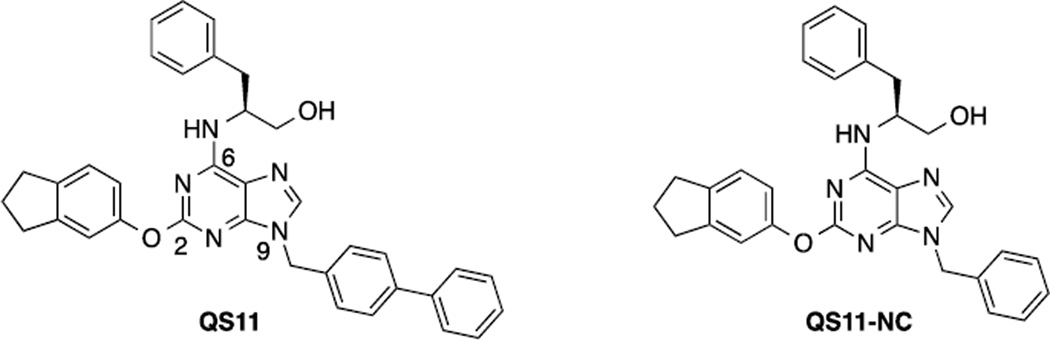

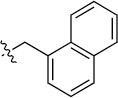

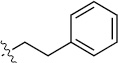

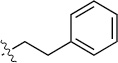

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is evolutionarily conserved and plays crucial roles in cellular differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis. Aberrant regulation of the pathway has been associated with various diseases including colorectal cancer, bipolar disorder and osteoporosis.1–3 Consequently, identifying novel Wnt modulators or pathways that cross-talk with the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has potential therapeutic significance.4–6 Previously, the small molecule QS11 (Figure 1) was demonstrated to synergize with Wnt proteins to activate β-catenin signaling.7 This appears to be through binding and inhibiting the ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein 1 (ARFGAP1). The close analog QS11-NC did not have effects on either Wnt signaling or ARFGAP1 activity.7 These results suggest an unexpected role of ARFGAP1 in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

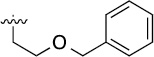

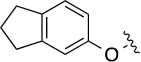

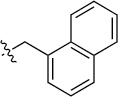

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of QS11 and QS11-NC.

ADP ribosylation factors (ARFs) are a family of GTP-binding proteins that are functional in cellular vesicle trafficking and actin remodeling processes,8, 9 and have been associated with various diseases such as invasive breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and autosomal recessive periventricular heterotopia.10, 11 Like other small GTPases, ARFs are activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that facilitate the release of GDP and binding of GTP, and deactivated by GAPs that catalyze the hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP.12 Different from other small GTPases, guanine nucleotide binding of ARFs is accompanied by conformational changes at its unique myristoylated N-terminal helix and by membrane association/dissociation.13–16 The mechanism of QS11 has therefore been proposed as activating cellular ARFs through inhibiting ARFGAP1, and QS11 has been successfully employed as ARFGAP inhibitors in a few studies in cellular environments.17–19 This hypothesis has been supported by other recent explorations of the role of ARFs for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. For example, Kim and coworkers showed that ARF-GTP level transiently increased upon stimulation with Wnt in a frizzled (Fzd), dishevelled, and LRP6-dependent manner.20 In addition, the activation of ARF1 was essential for Wnt-mediated synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2, which regulates the aggregation, phosphorylation and endocytosis of LRP6. Grossmann and coworkers further showed that in melanoma cells, ARF6 was activated via Fzd4-LRP6, which led to dissociation of β-catenin from membrane-bound N-cadherin and subsequently enhanced β-catenin-mediated gene transcription and cell invasion.21 Despite these positive connections, the direct inhibition of ARFGAP1 or any other GAP by QS11 has not been established. In addition, whether ARFGAP1 is the only major target of QS11 that contributes to its Wnt synergy remains unclear.

We synthesized QS11 derivatives and tested their activity in two assays that measure their capacity as ARFGAP1 inhibitors and as Wnt synergists for three reasons: 1) to confirm direct inhibition of ARFGAP activity by QS11; 2) to improve QS11’s potency and physical properties such as solubility; and 3) to compare the SAR of the two sets of assay data. The assays were carried out using modifications to protocols previously described in the literature.7, 22, 23 Briefly, to test ARFGAP1 enzymatic GAP activity, myristoylated wild type ARF1 and wild type ARFGAP1 were purified as described previously.24–26 ARF1 was preloaded with radiolabeled [γ-32P]GTP in the presence of liposomes. GTP hydrolysis was initiated by mixing with full length ARFGAP1 that was pre-incubated with QS11 analogs for 10 min, and stopped by charcoal precipitation to scavenge protein and non-hydrolyzed GTP. Hydrolyzed 32P-labeled phosphate remained in the supernatant, and was collected for scintillation counting. Due to the low throughput nature of the assay, ARFGAP1 inhibition was tested at only two compound concentrations with replicates. The activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was tested in HEK293 cells stably transfected with TOPFlash reporter. The cells were stimulated with Wnt3A conditional media for 24 h before luciferase activity was measured using the Bright-Glo luminescence kit.

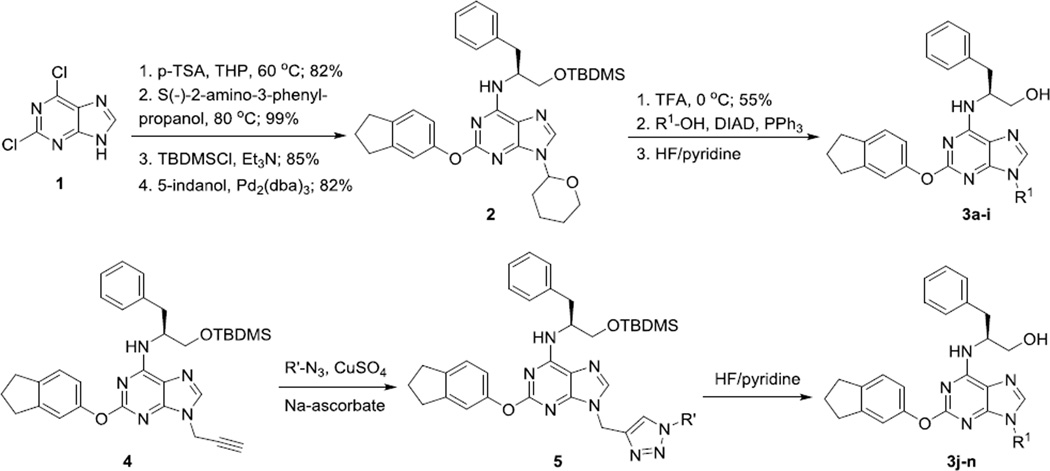

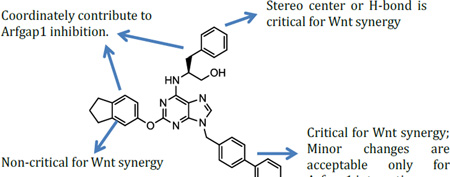

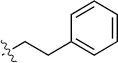

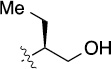

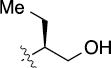

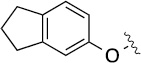

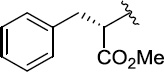

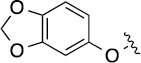

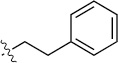

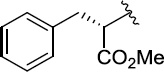

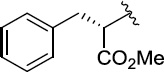

QS11 contains a planar purine ring with C2, C6, and N9-positions substituted. Naturally, the structural modifications are focused on these positions. The only difference between QS11 and QS11-NC is the substitution at the N9 position suggesting its critical role in activity. Consequently, we started our SAR studies by modifying the N-9 substitution. The synthetic route is shown in Scheme 1.7 The 2,6-dichloropurine was protected as the tetrahydropyran (THP) ether and the chlorides at the C6 and C2 positions were substituted with S(−)-2-amino-3-phenylpropanol and 5-indanol, respectively, to form compound 2. Removal of the THP protection in 2 followed by Mitsunobu reaction with various alcohols and treatment with HF/pyridine produced QS11 analogs 3 with different substitutions at the N9 position. To minimize the synthetic efforts for generating multiple analogs, we have also utilized the “click chemistry” strategy so that the modification at the N9 position is the final step of the synthesis (Scheme 1).27 A total of 14 analogs were synthesized using reactions in Scheme 1, including QS11 and QS11-NC.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of QS11 analogs with modifications at the N9 position.

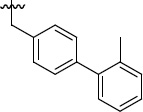

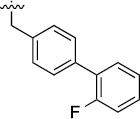

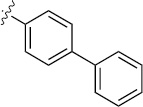

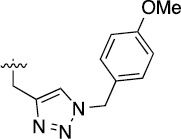

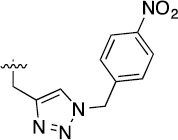

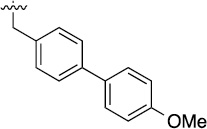

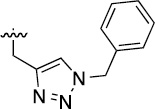

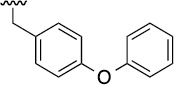

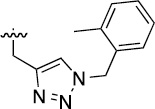

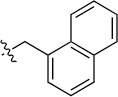

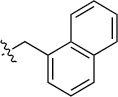

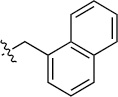

We first tested the activity of QS11 in the ARFGAP1 enzymatic assay (Table 1). At 10 and 20 µM, QS11 (3a) inhibited the enzymatic activity by 67% and 90%, respectively. In contrast, QS11-NC (3b) did not show any activity in this assay. The modifications on the biphenyl group are generally tolerated (3f, 3h, 3i), although the potencies decrease. The “spacer” between the purine core and the biphenyl substitution also has an impact on the ARFGAP1 activity: removal of the methylene spacer (3c) or addition of a methyl group (3e) decreased the activity. Insertion of an oxygen atom into the two phenyl ring (3g) decreased the activity slightly, possibly due to the perturbation of the perpendicular conformation of the biphenyl group. This notion is consistent with what was observed with QS11-NC and 3d. For both compounds, one phenyl ring is removed and neither compound has the capacity to inhibit the enzymatic activity of ARFGAP1. By incorporating the phenyl-triazole motif into the N9 position (3l), the analogs showed weak activity on ARFGAP1 inhibition. Adding a methylene spacer between the phenyl and triazole ring did not significantly improve the potency (3m, 3j), unless accompanied with ortho- electron donating group (3n) or para- electron withdrawing group (3k) on the phenyl ring. The results in the Wnt/β-catenin assay showed a distinct SAR profile. Other than QS11, only 3e showed potent synergistic activation effect with Wnt3A to activate the TOPFlash reporter, suggesting that the activity is highly sensitive to the biphenyl group in QS11.

Table 1.

SAR on QS11 analogues with modifications at the N-9 position

| Compound | R1 | EC50 (µM)a | Activity (%)b | Compound | R1 | EC50 (µM)a |

Activity (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

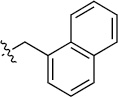

| 3a (QS11) |  |

1.5 | 10±6/33±12 | 3h |  |

>100 | 41±3/56±11 |

| 3b (QS11-NC) |  |

>100 | 113±15/117/12 | 3i |  |

>100 | 47±18/81±13 |

| 3c |  |

>100 | 32±9/50±22 | 3j |  |

>100 | 75±5/98±7 |

| 3d |  |

>100 | 109±4/106±11 | 3k |  |

>100 | 45±2/58±4 |

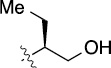

| 3e |  |

2.6 | 36±5/50±7 | 3l |  |

>100 | 57±10/105±11 |

| 3f |  |

>100 | 34±4/42±4 | 3m |  |

>100 | 62±6/93±7 |

| 3g |  |

>100 | 40±2/42±1 | 3n |  |

>100 | 27±4/50±2 |

EC50 in TOPFlash reporter assay in µM.

Percent remaining activity (RA) of ARFGAP1 with 20 µM and 10 µM of QS11 analogues in [γ-32P]GTP assay.

Number expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

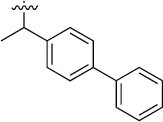

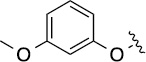

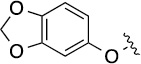

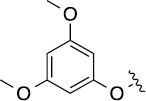

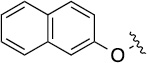

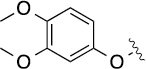

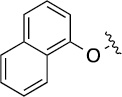

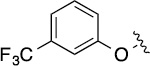

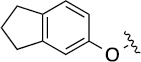

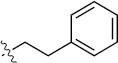

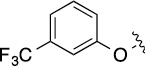

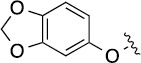

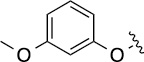

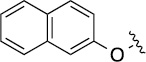

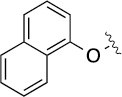

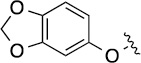

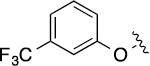

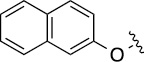

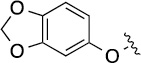

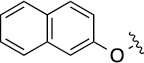

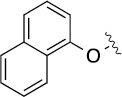

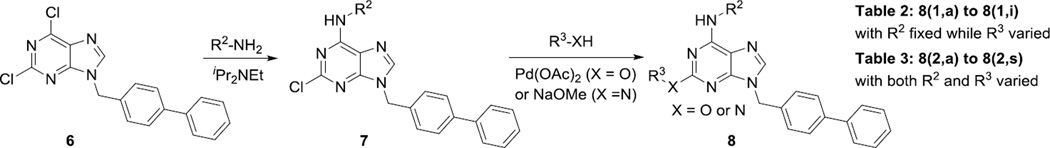

Next, we decided to fix the N9-substitution as the biphenyl group and vary the C6- and C2- positions for analog synthesis. As shown in Scheme 2, the biphenyl-substituted 2,6-dichloropurine 6 first reacted with amines to form 7, which subsequently were coupled with amines or alcohols at the C2 position to form 8. To investigate the SAR at the C2 position (Table 2), we initially also fixed the C6-substitution as the same as that in QS11. Distinct from the N9-modifications, C2-modifications are generally tolerated in both the ARFGAP1 enzymatic assay and the Wnt/β-catenin assay. In the ARFGAP assay, replacement of 3-trifluoromethylphenoxy group (8(1,d)) with 3-methoxyphenoxy group (8(1,e)), or with additional electron donating groups on the phenyl ring (8(1,a), 8(1,f), 8(1,g)) increased activity, suggesting that an electron rich phenyl ring is favored at C2 position. This is consistent with the moderate activity of naphthalene substituent analogs

Table 2.

SAR on QS11 analogues with modifications at the C2 position

| Compound | R2 | EC50 (µM) | Activity (%) | Compound | R2 | EC50(µM) | Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a (QS11) |  |

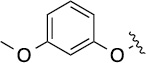

1.5 | 10±6/33±12 | 8(1,e) |  |

3.3 | 29±3/54±16 |

| 8(1,a) |  |

8.5 | 39±7/49±8 | 8(1,f) |  |

1.9 | 11±5/24±5 |

| 8(1,b) |  |

4.4 | 35±6/53±6 | 8(1,g) |  |

3.6 | 22±3/55±13 |

| 8(1,c) |  |

6.6 | 24±5/35±9 | 8(1,h) | 2.6 | 39±13/70±25 | |

| 8(1,d) |  |

2.9 | 78±5/81±4 | 8(1,i) |  |

1.5 | 71±6/98±5 |

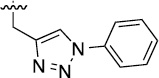

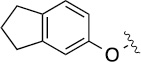

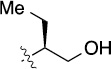

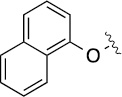

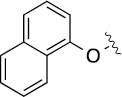

Finally, we explored the effects of the substitution at the C6 position on both ARFGAP1 inhibition and Wnt synergistic activation (Table 3). Consistent with what was observed in Table 2, the C2 position tolerates multiple variations in the ARFGAP assay when C6 and N9 positions are fixed. The SAR at the C2 position is dependent on the C6-substitution, implicating a potential collaborative interaction between these two positions. For example, substituents of a 2-naphthyl at either C2 or C6 positions generally enhanced the inhibition activity, rendering 8(2,d) one of our best analogs and indicating enhanced hydrophobicity is favored at these positions. The analog 8(2,e) with a naphalene group at the C6 position shows higher activity than 8(2,k), where a naphalene group is replaced with a phenethyl moiety, further suggesting the role of hydrophobicity at the C6 position. Replacement of the hydroxyl group at C6 with an ester also enhanced the activity (8(2,q), 8(2,r), 8(2,s)) and the EC50 value for 8(2,r) in the TOPFlash reporter assay was also improved by approximately 2-fold compared to that for QS11, indicating that an H-bond donor instead of acceptor may be favored at this position. TOPFlash reporter assay strongly disfavors the removal of stereo center and H-bond formation groups at the C6 position, thus analogs with naphthylmethyl substituent and phenylethyl substituent completely abolished Wnt synergistic effects. On the other hand, removal of the phenyl ring at C6 position is tolerated (8(2,m), 8(2,o), 8(2,p)).

Table 3.

SAR on QS11 analogues with modifications at the C-2 and C-6 positions.

| Compound | R2 | R3 | EC50 (µM) |

Activity (%) |

Compound | R2 | R3 | EC50 (µM) |

Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8(2,a) |  |

|

>100 | 63±8/74±13 | 8(2,k) |  |

|

>100 | 33±9/41±6 |

| 8(2,b) |  |

|

>100 | 34±13/35±7 | 8(2,l) |  |

|

>100 | 40±12/46±5 |

| 8(2,c) |  |

|

>100 | 31±2/53±10 | 8(2,m) |  |

|

4.5 | 57±5/90±6 |

| 8(2,d) |  |

|

>100 | 20±5/20±5 | 8(2,n) |  |

|

>100 | 32±6/70±14 |

| 8(2,e) |  |

|

18 | 12±1/16±2 | 8(2,o) |  |

|

4.0 | 24±3/41±0 |

| 8(2,f) |  |

|

>100 | 29±5/37±11 | 8(2,p) |  |

|

1.3 | 15±2/22±2 |

| 8(2,g) |  |

|

>100 | 50±11/60±13 | 8(2,q) |  |

|

1.1 | 18±2/31±11 |

| 8(2,h) |  |

|

>100 | 27±3/31±3 | 8(2,r) |  |

|

0.65 | 17±2/25±4 |

| 8(2,i) |  |

|

>100 | 20±1/32±1 | 8(2,s) |  |

|

3.4 | 12±2/21±3 |

| 8(2,j) |  |

|

>100 | 86±29/90±18 |

In summary, we have synthesized over 40 QS11 analogs and tested their activity in both the ARFGAP assay and the TOPFlash reporter assay. The study validates QS11’s activity as an ARFGAP inhibitor and identifies several QS11 analogs either with improved potency and/or solubility.28–29 The SAR encourages further analog synthesis to generate better Wnt synergists and/or ARFGAP inhibitors. The SAR at the C2, C6 and N9 positions for the ARFGAP assay are not the same as those for the TOPFlash assays, raising the concern whether ARFGAP1 is the major cellular target that contributes to QS11’s synergy with Wnt. We acknowledge that this conclusion is preliminary because the solubility, hydrophobicity, cellular permeability, and stability in the cell of each compound are likely to be different and so confound the apparent results. Nonetheless, the study suggests that a more comprehensive target identification of QS11 will likely provide novel insights into the role of ARFGAP1 in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of QS11 analogs with modifications at C2 and C6 positions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (GM086558 to Q.Z.) from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Randall Moon (University of Washington) for providing the cells stably transfected with the SuperTOPFlash reporter and Dr. Paul Randazzo (National Cancer Institute) for providing the plasmid for myristoylated ARF1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be access on website.

References

- 1.Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV, Kaykas A. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:689. doi: 10.1038/nrg1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polakis P. Gene Dev. 2000;14:1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polakis P. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbst A, Kolligs FT. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;361:63. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-208-4:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anastas JN, Moon RT. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:11. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bejsovec A. Cell. 2005;120:11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q, Major MB, Takanashi S, Camp ND, Nishiya N, Peters EC, Ginsberg MH, Jian X, Randazzo PA, Schultz PG, Moon RT, Ding S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702136104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavrier P, Goud B. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:466. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers KR, Casanova JE. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:184. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabe H, Onodera Y, Mazaki Y, Hashimoto S. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:558. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheen VL, Ganesh VS, Topcu M, Sebire G, Bodell A, Hill RS, Grant PE, Shugart YY, Imitola J, Khoury SJ, Guerrini R, Walsh CA. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:69. doi: 10.1038/ng1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillingham AK, Munro S. Annu. Rev. Cell and Dev. Biol. 2007;23:579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasqualato S, Renault L, Cherfils J. Embo. Rep. 2002;3:1035. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg J. Cell. 1998;95:237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Kahn RA, Prestegard JH. Structure. 2009;17:79. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonny B, Beraud-Dufour S, Chardin P, Chabre M. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4675. doi: 10.1021/bi962252b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CA, Nishiya N, London NR, Zhu W, Sorensen LK, Chan AC, Lim CJ, Chen H, Zhang Q, Schultz PG, Hayallah AM, Thomas KR, Famulok M, Zhang K, Ginsberg MH, Li DY. Nat. cell Biol. 2009;11:1325. doi: 10.1038/ncb1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu W, London NR, Gibson CC, Davis CT, Tong Z, Sorensen LK, Shi DS, Guo J, Smith MC, Grossmann AH, Thomas KR, Li DY. Nature. 2012;492:252. doi: 10.1038/nature11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanamarlapudi V, Thompson A, Kelly E, Lopez Bernal A. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim W, Kim SY, Kim T, Kim M, Bae DJ, Choi HI, Kim IS, Jho E. Oncogene. 2013;32:3390. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossmann AH, Yoo JH, Clancy J, Sorensen LK, Sedgwick A, Tong Z, Ostanin K, Rogers A, Grossmann KF, Tripp SR, Thomas KR, D'Souza-Schorey C, Odelberg SJ, Li DY. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:ra14. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Che MM, Nie Z, Randazzo PA. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:147. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber I, Rotman M, Pick E, Makler V, Rothem L, Cukierman E, Cassel D. Method Enzymol. 2001;329:307. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)29092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha VL, Thomas GM, Stauffer S, Randazzo PA. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:164. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randazzo PA, Fales HM. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002;189:169. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-281-3:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Premont RT, Vitale N. Methods Enzymol. 2001;329:335. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)29095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakshman MK, Singh MK, Parrish D, Balachandran R, Day BW. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2461. doi: 10.1021/jo902342z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mugnaini C, Nocerino S, Pedani V, Pasquini S, Tafi A, Chiaro MD, Bellucci L, Valoti M, Guida F, Luongo L, Dragoni S, Ligresti A, Rosenberg A, Bolognini D, Cascio MG, Pertwee RG, Moaddel R, Maione S, Marzo VD, Corelli F. ChemMedChem. 2015;7:920. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Columbano G, Albani C, Ottonello G, Ribeiro A, Scarpelli R, Tarozzo G, Daglian J, Jung K-M, Piomelli D, Bandiera T. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:380. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.