Abstract

Among the perfluoroalkyl sulfonates (PFASs), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) have half-lives of several years in humans, mainly due to slow renal clearance and potential hepatic accumulation. Both compounds undergo enterohepatic circulation. To determine whether transporters involved in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids are also involved in the disposition of PFASs, uptake of perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS), PFHxS, and PFOS was measured using freshly isolated human and rat hepatocytes in the absence or presence of sodium. The results demonstrated sodium-dependent uptake for all 3 PFASs. Given that the Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) and the apical sodium-dependent bile salt transporter (ASBT) are essential for the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, transport of PFASs was investigated in stable CHO Flp-In cells for human NTCP or HEK293 cells transiently expressing rat NTCP, human ASBT, and rat ASBT. The results demonstrated that both human and rat NTCP can transport PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS. Kinetics with human NTCP revealed Km values of 39.6, 112, and 130 µM for PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS, respectively. For rat NTCP Km values were 76.2 and 294 µM for PFBS and PFHxS, respectively. Only PFOS was transported by human ASBT whereas rat ASBT did not transport any of the tested PFASs. Human OSTα/β was also able to transport all 3 PFASs. In conclusion, these results suggest that the long half-live and the hepatic accumulation of PFOS in humans are at least, in part, due to transport by NTCP and ASBT.

Keywords: perfluoroalkyl sulfonates, perfluorobutane sulfonate, perfluorohexane sulfonate, perfluorooctane sulfonate, hepatocytes

Perfluoroalkyl sulfonates (PFASs) are fluorinated fatty acid analogs used as surfactants in industrial and commercial applications (Buck et al., 2011; Kissa and Kissa, 2001). Due to the unique physicochemical properties of the carbon–fluorine bonds, certain PFASs such as perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) are resistant to environmental and biological degradation. They are frequently detected in the environmental biota (Calafat et al., 2007; Fromme et al., 2009; Houde et al., 2011; Kato et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2012). Consequently, PFOS has been nominated to the Stockholm Convention in 2009 as a persistent organic pollutant (http://chm.pops.int/Implementation/NewPOPs/TheNewPOPs/tabid/672/Default.aspx).

Pharmacokinetic studies revealed that PFASs primarily bind to serum proteins and that their clearance is species- and chain length-dependent (Andersen et al., 2008). In Sprague–Dawley rats, the estimated serum elimination half-life for PFOS (an 8-carbon homolog) is approximately 1 month (Chang et al., 2012) whereas perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS, a 4-carbon homolog) is efficiently excreted in urine with an estimated serum half-life of 3.9–4.5 h (Olsen et al., 2009). In rats, there is a distinct gender difference in the serum elimination of PFHxS (a 6-carbon homolog) in that the estimated half-lives are 30 days in male but only 2 days in female rats (Sundström et al., 2012). In cynomolgus monkeys, the estimated serum elimination half-lives for PFHxS and PFOS are approximately 4 months (Chang et al., 2012; Sundström et al., 2012); whereas for PFBS the respective half-life is approximately 4 days (Olsen et al., 2009). The estimated serum elimination half-lives of PFHxS and PFOS in human serum are several years [geometric means are 7.3 years (95% CI 5.8–9.2 years) and 4.8 years (95% CI 4.0–5.8 years), respectively] (Olsen et al., 2007). In contrast, PFBS has an estimated geometric serum elimination half-life of 26 days (95% CI 16–40 days) (Olsen et al., 2009).

Several studies have demonstrated that PFOS preferentially accumulates in the liver. In Sprague–Dawley rats given a single IV dose of 14C-radiolabelled PFOS, Chang et al. (2012) reported that 3% and 25% of the administered dose was recovered in plasma and liver, respectively, after 89 days. They also reported data for CD-1 mice and Sprague–Dawley rats given single oral doses which demonstrated that PFOS liver concentrations were always higher than concurrent serum PFOS concentrations by a factor of approximately 2–3 at measured time points following dosing. This is consistent with observations from repeat-dose studies in Sprague–Dawley rats where the liver to serum PFOS concentration ratios ranged from 2.5 to 12.2 in Sprague–Dawley rats after 4–14 weeks of dosing (Seacat et al., 2003). Thus, these data suggest that PFOS is preferentially distributed to the liver and may undergo enterohepatic circulation. In addition, studies by Johnson et al. (1984) and Genius et al. (2010) also provided evidence for enterohepatic circulation that may subsequently contribute to the preferential distribution of certain PFASs to liver. Male rats were given a single IV dose of 14C-labelled PFOS and followed for 21 days during which they were given either a basal diet or a diet containing the bile acid sequestrant, cholestyramine (Johnson et al., 1984). Fecal elimination of PFOS was increased approximately 10-fold, and liver and serum PFOS concentration were reduced by 75% and 85%, respectively, in rats given cholestyramine in their diet as compared to rats fed basal diet. A case study involving a single human subject demonstrated that cholestyramine was effective in removing both PFOS and PFHxS via fecal elimination (Genuis et al., 2010). More individuals were included in a follow-up study and cholestyramine treatment increased the fecal elimination of PFOS and PFHxS in all 8 subjects (Genuis et al., 2013).

Although previous studies have shown that certain perfluoroalkyl carboxylates are substrates of members of the organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) and the organic anion transporter (OAT) family (Han et al., 2012; Nakagawa et al., 2008; Weaver et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), interactions between PFASs and transporters might not be limited to OATPs and OATs. During the process of enterohepatic circulation of bile salts, it is well-known that the two uptake transporters Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) and apical sodium-dependent bile salt transporter (ASBT) play important roles (Hagenbuch and Dawson, 2004). NTCP is highly expressed at the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes and mediates the uptake of bile acids into hepatocytes in a sodium-dependent manner (Claro da Silva et al., 2013). Besides bile acids, other known substrates of NTCP include steroid sulfates such as estrone-3-sulfate (Schroeder et al., 1998), antihyperlipidemic drugs like rosuvastatin (Ho et al., 2006), and drug conjugates such as chlorambucil–taurocholate (Kullak-Ublick et al., 1997). When bile acids reach the gastrointestinal tract, ASBT localized to the brush-border membrane in the terminal ileum reabsorbs the majority of them and OSTα/β exports them across the basolateral membrane of enterocytes (Ballatori et al., 2005). ASBT is also expressed at the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells and at the apical membrane of cholangiocytes. Similar to NTCP, the transport by ASBT depends on the sodium gradient across the cell membrane. In contrast to NTCP, ASBT has narrow substrate specificity, which is restricted to bile acids (Claro da Silva et al., 2013).

Given the evidence that some PFASs might undergo enterohepatic circulation and given the important role the bile salt transporters play in the enterohepatic circulation, we hypothesized that bile salt transporters are involved in the disposition of PFASs. In this study, we investigated the roles of human and rat NTCP and ASBT as well as of human OSTα/β in transporting 3 PFASs (PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS). Initial inhibition studies and uptake experiments indicated the potential of interactions between PFASs and the transporters. Based on these results, additional time dependency and kinetic studies were performed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Radiolabelled [3H]-taurocholate and [3H]-estrone-3-sulfate were purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, Massachusetts), potassium perfluorobutane sulfonate (K+PFBS, 98.2% pure), potassium perfluorohexane sulfonate (K+PFHxS, >99% pure), and potassium perfluorooctane sulfonate (K+PFOS, 86.9% pure) were received from the 3 M Company (St. Paul, Minnesota).

Plasmids and cell lines

The rat ASBT (rASBT) cDNA was subcloned from a plasmid purchased from Origene (NM_017222, RN209999, Rockville, Maryland) into the pcDNA5/FRT vector using PCR and restriction digestion with the following primers: forward primer containing an Nhe I restriction site: 5′-AGAGGCTAGCACCATGGATAACTCCTCCGTCT-3′, reverse primer including a 6-His tag and the Not I restriction site 5′-AGAGGCGGCCGCCCTAGTGGTGATGGTGATGATGTTTCTCATCTGGTTGA-3′. A human NTCP (hNTCP) containing pSport1 vector (Hagenbuch and Meier, 1994) was digested with restriction enzymes Kpn I and BamH I, and the resulting hNTCP cDNA was inserted into the pcDNA5/FRT vector. CHO Flp-in cells were transfected with the hNTCP-pcDNA5/FRT construct to generate a stable hNTCP expressing cell line. Rat NTCP (rNTCP) was cloned into the pcDNA5/FRT expression vector from a cell line overexpressing rat NTCP (Schroeder et al., 1998) using the following primers: forward primer with a Nhe I restriction site, 5′-AGAGAGCGGCCGCCTAATGGTGATGGTGATGATGATTTGCCATCTGACCAGAATTC-3′; reverse primer containing a 6-His tag and the Not I restriction site, 5′-AGAGAGCGGCCGCCTAATGGTGATGGTGATGATGATTTGCCATCTGACCAG-3′. The human ASBT (hASBT) cDNA was subcloned from a plasmid purchased from Open Biosystems (OHS6084-202630699, Lafayette, Colorado) into the pcDNA5/FRT expression vector using PCR and restriction digestion with the following primers: forward primer containing a Hind III restriction site, 5′-AGAGAAGCTTCGGGACCATGAATGATCCGAACAGCTG-3′; reverse primer including a 6-His tag and the Kpn I restriction site, 5′-AGAGGGTACCTTATTAATGGTGATGGTGATGATGCTTTTCGTCAGGTTGAAATCC-3′. The human OSTα cDNA in pCMV6-XL4 (Origene SC100623, NCBI NM_152672) was digested with NotI and inserted into pcDNA5/FRT vector. The human OSTβ cDNA in pCMV6-Entry (Origene (RC517638, NCBI NM_178859) was subcloned into pcDNA5/FRT using the following primers: 5′-AGAGGCTAGCACCATGGAGCACAGTGAGG-3′ with an NheI restriction site as forward primer and 5′-AGAGGCGGCCGCCCTAGCTCTCAGTTTCTGGTACATC-3′ with an NotI restriction site as the reverse primer. Correctness of all sequences was verified by DNA sequencing.

Tissue culture and transporter expression

CHO-hNTCP cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 1 g/l d-glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer, and 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), 50 µg/ml l-proline, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 500 µg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). For uptake assays, CHO-hNTCP cells were plated at 40 000 cells per well on 24-well plates and 72 h later used for uptake experiments. Medium was changed when needed.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia) were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in DMEM High Glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. HEK293 cells were plated at 200 000 cells per well in 24-well plates coated with 0.1 mg/ml poly-d-lysine. Twenty-four hours later cells were transfected with 0.5 µg plasmid DNA and 1.5 µl Fugene HD (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) per well and uptake assays were performed 48 h later. Medium was changed when needed.

Human and rat hepatocytes were isolated by the Cell Isolation Core in the Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutics at University of Kansas Medical Center as described (Xie et al., 2014). All human liver specimens were obtained in accordance with an HSC approved protocol from patients undergoing hepatic resection procedures or from donor organs. The hepatocytes were then seeded at 250 000 cells per well on collagen coated 24-well plates and allowed to attach in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Uptake with human hepatocytes was determined 24 h after plating and uptake with rat hepatocytes was measured 3 h after plating.

Cell-based transport assays

Cells were washed 3 times with 1 ml of prewarmed (37°C) CHO uptake buffer (116.4 mM NaCl or choline chloride, 5.3 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 5.5 mM d-glucose, and 20 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with Tris-base), HEK293 uptake buffer (142 mM NaCl or choline chloride, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, and 12.5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), or hepatocyte uptake buffer (136 mM NaCl or choline chloride, 5.3 mM KCl, 1.1 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 11 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Then, 200 µl uptake buffer (37°C) containing PFASs or radiolabeled model substrates were added to the well to initiate transport. Uptake was terminated at indicated time points by two 1-ml washes with ice-cold uptake buffer containing 3% bovine serum albumin and two 1-ml washes with plain ice-cold uptake buffer. Cells were lysed with 200 µl 1% Triton X-100 in H2O for PFASs or 300 µl 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for radiolabeled substrates at room temperature for 20 min. For PFASs, 120 µl cell lysate was used for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). For radiolabeled substrates, 200 µl of cell lysate was transferred to a 24-well scintillation plate (Perkin, Billerica, Massachusetts) and 750 µl Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts) was added to each well. Radioactivity was measured in a Microbeta liquid scintillation counter. The remaining cell lysates were transferred to 96-well plates to determine the total protein concentration using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, Illinois). All transport measurements were corrected by the total protein concentration. All experiments were performed 2 to 4 times independently with triplicate determinations.

Sf9 vesicle transport

Sf9 vesicles overexpressing human MRP2, BCRP, or BSEP were purchased from Corning Incorporated (Tewksbury, Massachusetts). Fifty µg human MRP2, BCRP, or BSEP Sf9 vesicles were incubated with model substrates CDCF (Corning gentest MRP/BCRP vesicle assay kit), [3H]-estrone-3-sulfate or [3H]-taurocholate at 37°C in the presence of 5 mM ATP or AMP for 15, 3, or 30 min, respectively. The reaction was stopped by filtering the vesicle suspension through a 96-well glass fiber filter plate (Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) on a MultiScreenHTS vacuum manifold (Millipore) and the filters were washed 6 times with ice-cold wash buffer from the corresponding vesicle assay kit (Corning). For radiolabeled substrates, Optiphase Supermix scintillation cocktail was added to the filter and it was heat sealed and used directly for counting in a Microbeta liquid scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer). For the fluorescent substrate CDCF, 100 µl 0.1 N NaOH was added to each well and the substrate was eluted into a fresh 96-well plate. Fluorescence was determined in a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont) at 485/525 nm. Transport was determined by subtracting the values in the presence of AMP from the values in the presence of ATP. All experiments were performed 2 times independently with triplicate determinations.

LC-MS/MS analyses for PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS

Cell lysates collected (vide supra) were analyzed for PFBS, PFHxS, or PFOS by LC-MS/MS using the following procedures:

(1) Standard and sample preparation

A fixed amount of internal standard (either 18O2-PFBS, 18O2-PFHxS, or 18O2-PFOS) was added to new disposable 1.8-ml polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes containing 25 ul of either PFAS standard or lysate samples. PFAS standards were prepared in the same buffer matrix as lysate samples.

To all tubes, 175 µl of a solution containing 5% ammonium acetate (2 mM) and 95% acetonitrile was added followed by vortex (approximately 5 s) and then centrifugation (2500 × g, 20 min, room temperature). Subsequently, 180 μl of the supernatant was aliquoted to a new clean 100-μl polypropylene auto sampler vial pending LC-MS/MS analyses. The reagent-grade water used for all the LC-MS/MS analyses was MilliQ deionized water that has been further purified to remove residual traces of perfluorinated compounds by being pumped through a C-18 HPLC column prior to use.

(2) LC-MS/MS conditions

The instrument used for analysis was an API 5000 mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS-Sciex Instrument Corporation) configured with Turbo Ion Spray (pneumatically assisted electrospray ionization source) in negative ion mode. Separation of the compounds was completed on a Mac-Mod ACE C-18, 5 µm, 75 × 2.1 mm i.d. HPLC column with a gradient flow rate of 0.250 ml/min (dual column method) using the conditions specified in Table 1. All source parameters were optimized under these conditions according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Transition ions monitored were as follows: PFBS: 299 -> 80 amu; PFBS Internal Standard: dual 18O2-labeled PFBS: 303 -> 84 amu; PFHxS: 399 -> 80 amu; PFHxS Internal Standard: triple 18O2-labeled PFHxS: 405 -> 86 amu; PFOS: 499 -> 80 amu; PFOS Internal Standard: dual 18O2-labeled PFOS: 503 -> 84 amu.

TABLE 1.

LC-MS/MS Conditions for HPLC Separation of PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS

| Time (min) | Mobile phase B % |

|---|---|

| 0.01 | 30 |

| 1.80 | 30 |

| 3.50 | 60 |

| 4.50 | 60 |

| 5.50 | 90 |

| 7.00 | 90 |

| 8.00 | 30 |

| 11.50 | 30 |

| 11.55 | End of run |

The gradient was run with mobile phase A (2 mM ammonium acetate) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for significant differences using 1-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett post-test for inhibition assays and Student’s t-test for one time point uptake determinations. p < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Uptake of PFASs by Human and Rat Hepatocytes

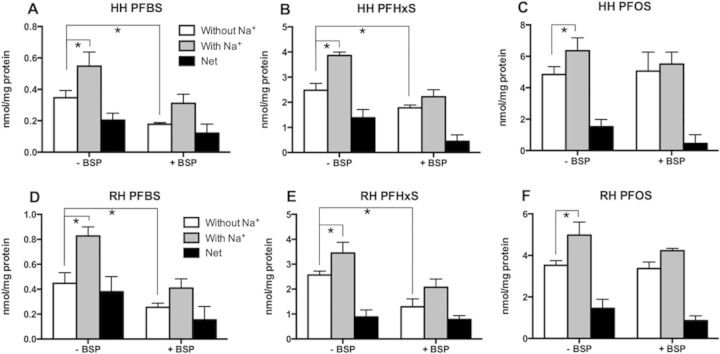

To determine whether sodium-dependent transporters are involved in the uptake of PFASs into hepatocytes, uptake of 50 µM PFBS, PFHxS, or PFOS was measured at 2 min using freshly isolated human and rat hepatocytes. First, sodium-dependent uptake of [3H]-taurocholate was used to ascertain that the isolated hepatocytes were functional (Supplementary Fig. 1). Then, sodium-dependent uptakes of the 3 PFASs were measured in the same batches of hepatocytes. As seen in Figures 1A to 1C, sodium-dependent uptake was observed for all 3 PFASs in human hepatocytes. Under the experimental conditions used, the net sodium-dependent uptakes (net uptake, black bars) for PFHxS (Fig. 1B) and PFOS (Fig. 1C) were similar and they were higher than PFBS (Fig. 1A). Similar sodium-dependent uptake also was observed in rat hepatocytes for PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS (Figs. 1D to 1F). In addition, uptake was also measured in the presence of 100 µM bromosulfophthalein (BSP), a known inhibitor of both NTCP and the OATPs. BSP inhibited both sodium-dependent and sodium-independent uptake of PFBS and to a lesser degree, PFHxS. For PFOS, only the sodium-dependent portion was inhibited (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PFAS uptake into freshly isolated human (A–C) and rat (D–F) hepatocytes. Uptakes of 50 µM PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS in the absence or presence of 100 µM bromosulfophthalein (BSP) was measured into freshly isolated human (HH) and rat hepatocytes (RH) for 2 min in the absence (white bars) or presence (gray bars) of sodium. Net sodium-dependent uptake (black bars) was calculated by subtracting the value of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium. Each bar represents the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments with triplicate determinations. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. *p < .05.

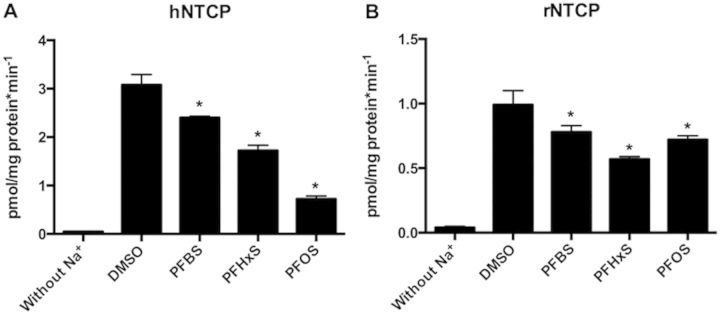

Uptake of PFASs by Human and Rat NTCP

To test whether PFASs would interact with human or rat NTCP, uptake of the model substrate [3H]-taurocholate was measured in the absence or presence of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, or PFOS. Using CHO Flp-in cells stably expressing human NTCP, the uptake of [3H]-taurocholate was inhibited in a PFAS-chain length-dependent manner with PFOS exerting the strongest effect followed by PFHxS and PFBS (Fig. 2A). In HEK293 cells transiently expressing rat NTCP, PFHxS showed the strongest inhibition of [3H]-taurocholate uptake (50% inhibition) whereas PFBS and PFOS inhibited only by 20%–25% (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of 3H-taurocholate uptake mediated by human (A, hNTCP) and rat (B, rNTCP) NTCP by PFASs. Human NTCP-mediated 30 nM [3H]-taurocholate uptake was measured at 37°C for 1 min in the absence (DMSO) or presence of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS using the CHO-hNTCP cell line. Rat NTCP-mediated 30 nM [3H]-taurocholate uptake was measured at 37°C for 1 min in the absence or presence of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS using HEK293 cells transiently transfected with rNTCP. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. *p < .05 compared to DMSO control.

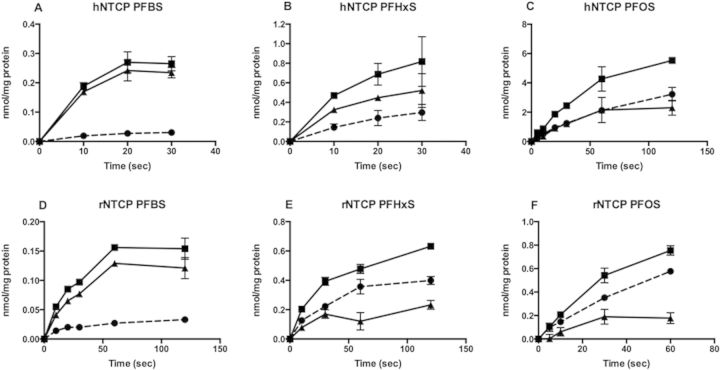

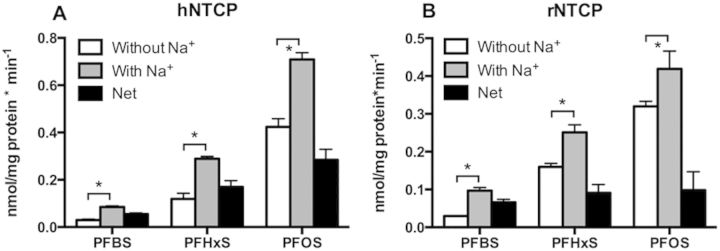

Based on the results of the inhibition experiments that demonstrated interactions with all 3 PFASs, direct uptakes of PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS by human and rat NTCP were determined and quantified by LC-MS/MS. As shown in Figure 3A, using 10 µM substrate and 1-min incubation, sodium-dependent net uptake by human NTCP was highest for PFOS, followed by PFHxS and PFBS mirroring the chain length-dependent inhibition seen before. In contrast, net uptake by rat NTCP was similar for all 3 PFASs at the same experimental condition (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Uptake of PFAS by human (A, hNTCP) and rat (B, rNTCP) NTCP. CHO-hNTCP cells or HEK293 cells transiently transfected with rNTCP were used to measure the uptake of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS in the absence (white bars) and presence (gray bars) of sodium. Net sodium-dependent uptake (black bars) was calculated by subtracting the values of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium. Each bar represents the mean ± SD from 2 independent experiments each performed with triplicate determinations. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. *p < .05.

In order to further characterize the transport by NTCP, uptakes of PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS were measured in a time-dependent manner at low (10 µM) and high substrate concentrations (200 µM for PFBS and 400 µM for PFHxS and PFOS). At low concentrations, the duration of the initial linear portion of human NTCP-mediated transport (Figs. 4A–C) was different between the 3 PFASs. The initial linear range was approximately 10 s for uptake for PFBS and PFHxS and it extended up to 60 s for PFOS. For rat NTCP, the initial linear range was around 20 s for PFBS (Fig. 4D) and 30 s for both PFHxS (Fig. 4E) and PFOS (Fig. 4F). At the high substrate concentrations, uptake of all PFASs by human and rat NTCP was linear up to at least 20 s (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Time-dependent uptake of PFASs by human (A–C; hNTCP) and rat (D–F; rNTCP) NTCP. Uptake of 10 µM PFBS (A, D), PFHxS (B, E), and PFOS (C, F) was measured at 37°C at the indicated time points using CHO-hNTCP cells and HEK293 cells transiently transfected with rNTCP in the absence (circles) and presence (squares) of sodium. Net sodium-dependent uptake (triangles) was calculated by subtracting the value of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. Each point represents the mean ± SD of triplicates.

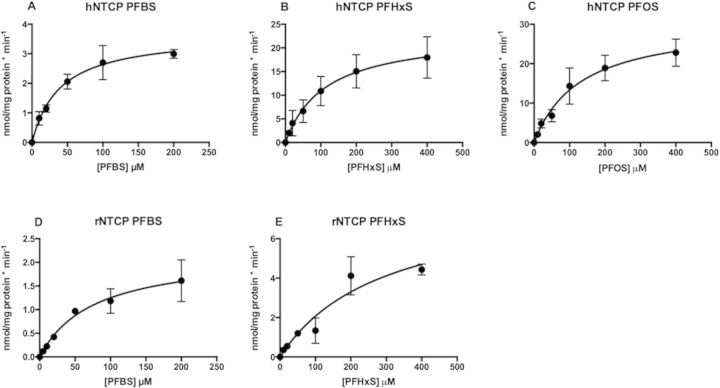

Based on the results from the time-dependent uptake experiments, all concentration- dependent transport measurements for kinetic analysis of PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS were determined at 10 s. Concentration-dependent net sodium-dependent uptake of PFBS, PFHxS and PFOS by human NTCP, and PFBS and PFHxS by rat NTCP are shown in Figures 5A to 5E. Kinetic parameters were calculated based on the Michaelis–Menten equation and the resulting Km and Vmax values are summarized in Table 2. PFBS was transported by human NTCP with the highest affinity (Km value of 39.6 µM) but the lowest Vmax value whereas both PFHxS (Km = 112 µM) and PFOS (Km = 130 µM) had lower affinities and higher maximal transport rates. The intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km) was similarly twice as high for the 2 substrates with the higher Vmax values. With respect to rat NTCP, although PFBS was transported with a higher affinity (Km = 76.2 µM) than PFHxS (Km = 294 µM) the difference in the Vmax values resulted in equal intrinsic clearances for both compounds (Table 2). The kinetic parameters of PFOS by rat NTCP were not determined due to low signal-to-noise ratio of the transport.

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of human (A–C) and rat (D, E) NTCP-mediated transport of PFBS (A, D), PFHxS (B, E), and PFOS (C). Uptake of increasing concentrations of PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS was measured within the initial linear range of transport using CHO-hNTCP cells (A–C) and HEK293 cells transiently transfected with rNTCP (D, E). Net uptake was calculated by subtracting the values of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium and was corrected for total protein concentration. Resulting data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation to obtain Km and Vmax values. Each point represents the mean ± SD from 3 to 4 independent experiments performed in triplicates.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of PFBS, PFHxS and PFOS transport mediated by human or rat NTCP

| Transporter | PFAS | Km (µM) | Vmax (nmol/mg/protein*min) | Vmax/Km (ml/mg/protein*min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hNTCP | PFBS | 39.6 ± 8.2 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.02 |

| PFHxS | 112 ± 32.9 | 23.2 ± 3.0 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | |

| PFOS | 130 ± 32.9 | 30.7 ± 3.2 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | |

| rNTCP | PFBS | 76.2 ± 23.6 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| PFHxS | 294 ± 121 | 8.1 ± 1.8 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

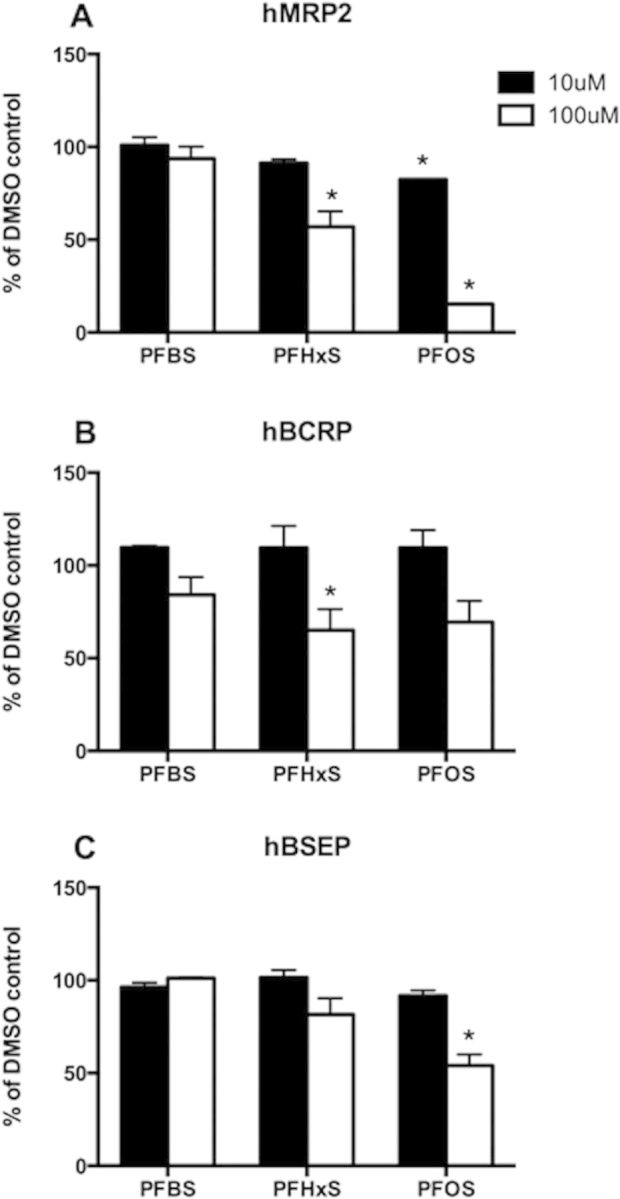

Inhibition of Human MRP2, BCRP and BSEP Transport by PFASs

To determine whether PFASs interact with efflux transporters in the hepatocytes, transport of model substrates by human MRP2 (model substrate CDCF), BCRP (model substrate [3H]-estrone-3-sulfate), and BSEP Sf9 vesicles (model substrate [3H]-taurocholate) was measured in the absence or presence of PFBS, PFHxS or PFOS at either 10 or 100 µM. While the transport of CDCF by human MRP2 was not affected by PFBS (Fig. 6A), it was inhibited by PFHxS (100 µM) and PFOS (10 µM and 100 µM). At 100 µM, PFOS did inhibit the transport by more than 80% (Fig. 6A). Transport of [3H]-estrone-3-sulfate mediated by human BCRP was decreased in the presence of all 3 PFASs, however, only the inhibition by 100 µM PFHxS was statistically significant (Fig. 6B). In addition, BSEP-mediated transport of [3H]-taurocholate was only inhibited by 100 µM PFOS but not by any of the other conditions (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of human MRP2 (A), BCRP (B), and BSEP (C) transport by PFASs. Transport of 5 µM CDCF, 0.01 µM [3H]-estrone-3-sulfate or 0.5 µM [3H]-taurocholate by human MRP2, BCRP and BSEP vesicles were measured with or without 10 µM (Black bar) or 100 µM (white bar) PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. *p < .05 compared to DMSO control.

Transport of PFASs by Human and Rat ASBT

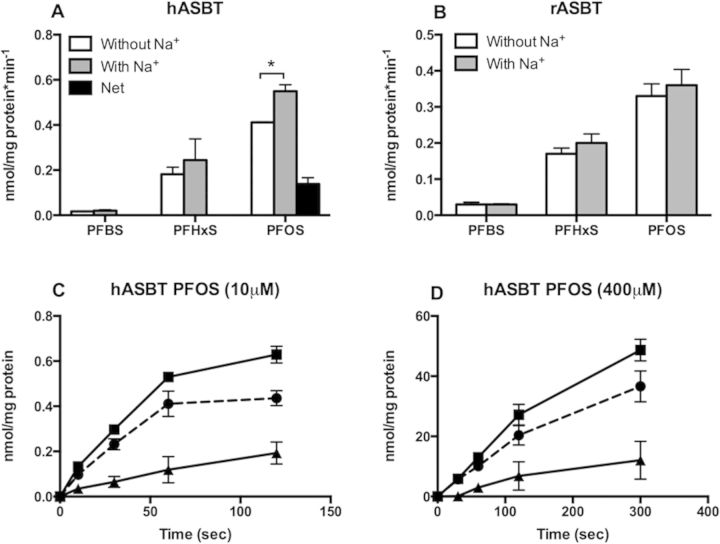

ASBT is another sodium-dependent transporter belonging to the same gene family as NTCP. It is normally expressed at the apical membrane of ileal enterocytes, cholangiocytes, and renal proximal tubule cells. It transports bile acids in a sodium-dependent way. In HEK293 cells transiently expressing human or rat ASBT, uptake of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, or PFOS was measured at 1 min in the absence or presence of sodium. Sodium-dependent uptake was only observed for PFOS by human ASBT (Fig. 7A) while none of the 3 PFASs were transported by rat ASBT (Fig. 7B). The proper function of human and rat ASBT was confirmed by measuring sodium-dependent transport of the model substrate [3H]-taurocholate (Supplementary Fig. 2).

FIG. 7.

Uptake of PFASs by human (A, C, D) and rat (B) ASBT. HEK293 cells transiently transfected with hASBT (A) or rASBT (B) were used to measure uptake of 10 µM PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS in the absence (white bars) or presence (gray bars) of sodium for 2 min. Net sodium-dependent uptake (black bars) was calculated by subtracting the values of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of triplicates from 2 independent experiments. (C, D) Uptake of 10 µM PFOS was measured at 37°C for the indicated time points by HEK293 cells transiently transfected with hASBT in the absence (circles) or presence (squares) of sodium. Net sodium-dependent uptake (triangles) was calculated by subtracting the values of uptake in the absence of sodium from uptake in the presence of sodium. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. Each point represents the mean ± SD of triplicates. *p < .05.

Time-dependent uptake was performed for human ASBT-mediated PFOS in order to further characterize its kinetics. Uptake was linear up to 2 min at both the low (10 µM) and high (400 µM) PFOS concentration (Figs. 7C and D). However, the kinetic parameters of PFOS transport could not be determined with confidence due to a low signal-to-noise ratio.

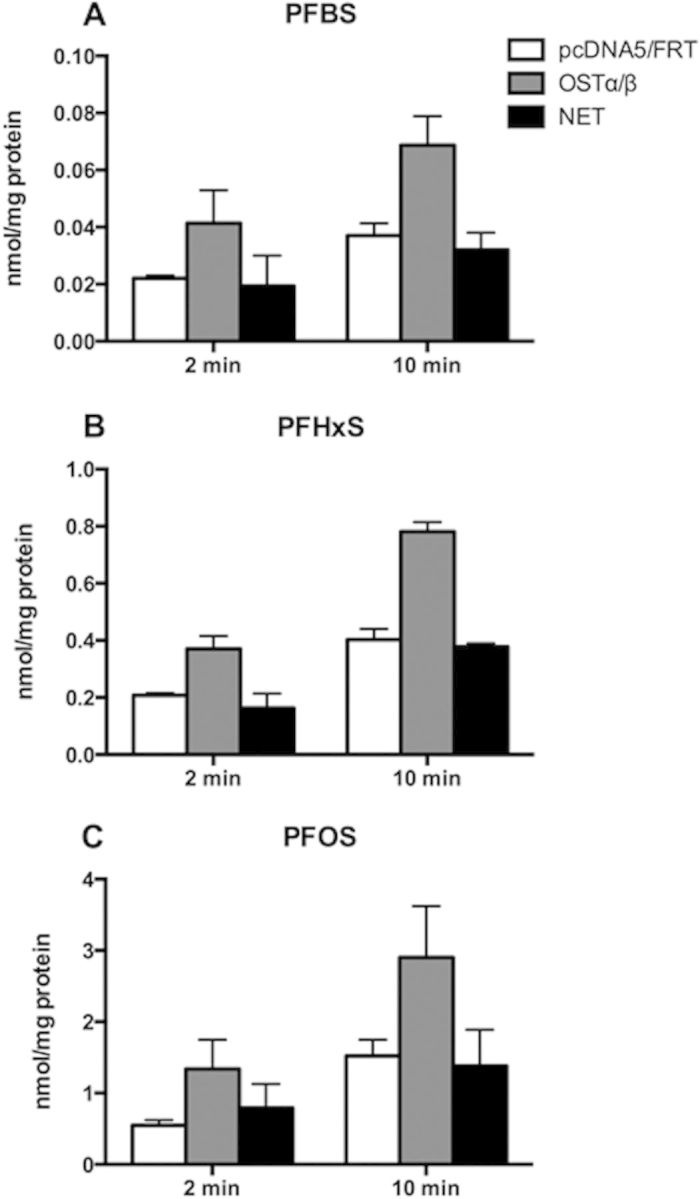

Transport of PFASs by Human OSTα/β

Human OSTα/β is expressed at the basolateral membrane of enterocytes to mediate the efflux of bile acids. Because it can transport bidirectionally depending on the concentration gradient of substrates, uptake of 10 µM PFASs was measured at 2 and 10 min after establishing the proper function of OSTα/β (Supplementary Fig. 3). At both time points, uptake of all 3 PFASs was higher in human OSTα/β transfected HEK293 cells than in empty vector transfected cells and net uptake was higher at 10 min as compared to 2 min (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Uptake of PFASs by human OSTα/β. HEK293 cells transiently transfected with hOSTα/β (gray bars) or empty vector pcDNA5/FRT (white bars) were used to measure uptake of 10 µM PFBS (A), PFHxS (B) or PFOS (C) at 2 and 10 min. Net uptake (black bars) was calculated by subtracting the values of uptake in empty vector transfected cells from uptake in the hOSTα/β transfected cells. The results were corrected for total protein concentration in each well. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of triplicates from 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that uptake of PFASs into human and rat hepatocytes is mediated by sodium-dependent and sodium-independent mechanisms. Furthermore, we could show that all 3 PFASs, PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS, are substrates for human and rat NTCP. Carrier-mediated uptake by rat hepatocytes has been reported previously for PFOA and it was shown that BSP, an inhibitor of OATPs and NTCP, can inhibit this transport (Han et al., 2008). However, specific transporters had not been identified so far. In addition to NTCP, we also demonstrated that human ASBT can mediate the uptake of PFOS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that sodium-dependent transport is reported for perfluoroalkyl substances. Furthermore, human OSTα/β was able to transport all 3 PFASs.

Using BSP as an inhibitor, we investigated whether the sodium-independent OATPs or the sodium-dependent NTCP would be the major transport system for the uptake of PFASs into hepatocytes. The fact that sodium-independent uptake of PFOS was not inhibited by BSP (Fig. 1) suggests that NTCP is the major uptake transporter and that OATPs play a minor role. The shorter chain PFBS and PFHxS are probably transported by both types of transporters but again, NTCP seems to be the major carrier given the minor inhibition of the sodium-independent uptake (Fig. 1).

Fenestration of sinusoids in combination with specific transporters in the sinusoidal membrane of hepatocytes allows numerous protein-bound endo- and xenobiotics to be excreted by the liver. While these fenestrae allow the protein-bound compounds to be in close proximity with the uptake transporters in hepatocytes, protein binding also prevents the compounds from being excreted in the urine via the glomerular filtration process in the kidneys. PFASs such as PFOS and PFHxS are highly protein-bound in the plasma, predominately to albumin (Butenhoff et al., 2012; Kerstner-Wood et al., 2003), and given that NTCP can transport these PFASs and it is abundantly expressed in the sinusoidal membrane, it is plausible that this could be the major mechanism for the previously reported preferential accumulation of these compounds in the liver (Kärrman et al. 2010; Maestri et al. 2006).

In humans, biliary excretion has been suggested as the main route of elimination for PFOS and has been estimated to be 200-fold higher than urinary excretion (Harada et al., 2007). The estimated reabsorption rates are 97% and 95% in humans and rats, respectively, very comparable between the 2 species (Harada et al., 2007). In the study reported herein, we demonstrated that PFOS and to a lesser degree, PFHxS, were able to inhibit MRP2, BCRP, and BSEP. These are 3 of the ABC transporters expressed in the canalicular membrane of human hepatocytes, suggesting that they are the likely candidates for canalicular secretion of PFOS and PFHxS. We would like to emphasize that inhibition does not necessarily mean that the inhibitors are substrates of the transporters they inhibit and as a consequence these 3 transporters should be tested in the future whether they directly mediate transport of PFOS and PFHxS.

We demonstrated that human ASBT can transport PFOS when expressed in HEK293 cells. It is plausible that human ASBT can transport PFOS in vivo as well and that would suggest that PFOS can be absorbed in the intestine preferentially compared to other PFASs. The relative high unspecific background seen in our data indicates that passive diffusion of PFOS probably plays an important role as well. We have preliminary data that demonstrated additional transporters expressed in the small intestine such as human OATP2B1 (Drozdzik et al., 2014) and rat OATP1A5 (Walters et al., 2000) could play a role in the reabsorption of PFASs, especially in the case of PFHxS and PFBS which were not transported by rat ASBT. However, detailed functional characterization of these transporters will need to be performed in the future.

In addition to enterocytes, ASBT is also expressed in the epithelial cells lining the bile duct where it samples biliary contents for signaling to the hepatocytes and is part of the cholehepatic shunt pathway (Benedetti et al., 1997; Meier and Stieger, 2002; Xia et al., 2006). In conjunction with ASBT transport, cholehepatic shunting of PFOS might be an additional critical component for its retention in the liver. Urinary excretion of PFOS is limited to a large extent as a result of its strong binding to serum albumin (Butenhoff et al., 2012). Even when dissociated from albumin, ASBT present in the brush border membrane of proximal tubular cells (Hagenbuch and Dawson, 2004) could potentially reabsorb the unbound PFOS present in the filtrate hence keeping the urinary excretion to a minimum.

Although we could show that PFBS is a substrate of both human and rat NTCP, the human serum elimination half-life has been estimated to be around 26 days and urine was shown to be the dominant route of elimination in rodents, monkeys, and human (Olsen et al., 2009). Compared with PFOS, the enhanced urinary excretion of PFBS could be due to enhanced glomerular filtration of PFBS with higher water solubility (PFBS is more water soluble than PFOS) and/or lower protein-binding in the blood (% protein binding of PFBS and PFOS to serum albumin are 93.5 and 99.8, respectively; Kerstner-Wood, 2003). The transporters of the OAT family expressed in the kidney (OAT1 and OAT3) may also play a role because these carriers are involved in the transport of the shorter chain PFCAs which are water-soluble (Weaver et al., 2010); hence, they are also the likely candidates for PFBS excretion.

It is well accepted that human NTCP transports, in addition to bile acids, other endo- and xenobiotics such as certain statins (Bi et al., 2013). Even though ASBT is a bile acid cotransporter closely related to NTCP, to date, known substrates of ASBT have been restricted to bile acids (Dawson, 2011; Hagenbuch and Dawson, 2004). Thus, the identification of PFOS as an ASBT substrate represents a very novel finding. This raises the possibility that other compounds similar to PFOS might be substrates of ASBT.

In conclusion, our studies reveal that PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS are substrates for the sodium-dependent liver transporter NTCP in humans and rats, and that human ASBT can transport PFOS. The 3 ABC transporters MRP2, BCRP, and BSEP can be inhibited in particular by PFOS, and human OSTα/β can transport all 3 PFASs. Thus, the combined action of the hepatic NTCP and ABC transporters, together with the intestinal ASBT and OSTα/β, likely facilitate the enterohepatic circulation of PFHxS and PFOS. In addition, ASBT expressed in cholangiocytes possibly contributes to cholehepatic shunting of PFOS. Both pathways could potentially play a role in the accumulation of PFOS in the liver and subsequently contribute to its long serum elimination half-life in humans.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants RR021940 and GM077336, by an unrestricted research grant from the 3 M Company, and by the Cell Isolation Core lab at the University of Kansas Medical Center Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutics, Kansas City, KS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Megan Roth and Zhonghua Sheng for their help with plasmid construction.

REFERENCES

- Andersen M. E., Butenhoff J. L., Chang S. C., Farrar D. G., Kennedy G. L., Jr, Lau C., Olsen G. W., Seed J., Wallace K. B. (2008). Perfluoroalkyl acids and related chemistries–toxicokinetics and modes of action. Toxicol. Sci. 102, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatori N., Christian W. V., Lee J. Y., Dawson P. A., Soroka C. J., Boyer J. L., Madejczyk M. S., Li N. (2005). OSTα-OSTβ: a major basolateral bile acid and steroid transporter in human intestinal, renal, and biliary epithelia. Hepatology 42, 1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti A., Di Sario A., Marucci L., Svegliati-Baroni G., Schteingart C. D., Ton-Nu H. T., Hofmann A. F. (1997). Carrier-mediated transport of conjugated bile acids across the basolateral membrane of biliary epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 272, G1416–G1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y. A., Qiu X., Rotter C. J., Kimoto E., Piotrowski M., Varma M. V., Ei-Kattan A. F., Lai Y. (2013). Quantitative assessment of the contribution of sodium-dependent taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP) to the hepatic uptake of rosuvastatin, pitavastatin and fluvastatin. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 34, 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck R. C., Franklin J., Berger U., Conder J. M., Cousins I. T., de Voogt P., Jensen A. A., Kannan K., Mabury S. A., van Leeuwen S. P. (2011). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 7, 513–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butenhoff J. L., Pieterman E., Ehresman D. J., Gorman G. S., Olsen G. W., Chang S. C., Princen H. M. (2012). Distribution of perfluorooctanesulfonate and perfluorooctanoate into human plasma lipoprotein fractions. Toxicol. Lett. 210, 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat A. M., Wong L. Y., Kuklenyik Z., Reidy J. A., Needham L. L. (2007). Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999-2000. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 1596–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. C., Noker P. E., Gorman G. S., Gibson S. J., Hart J. A., Ehresman D. J., Butenhoff J. L. (2012). Comparative pharmacokinetics of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) in rats, mice, and monkeys. Reprod. Toxicol. 33, 428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claro da Silva T., Polli J. E., Swaan P. W. (2013). The solute carrier family 10 (SLC10): beyond bile acid transport. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 252–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson P. A. (2011). Role of the intestinal bile acid transporters in bile acid and drug disposition. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol., 169–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdzik M., Groer C., Penski J., Lapczuk J., Ostrowski M., Lai Y., Prasad B., Unadkat J. D., Siegmund W., Oswald S. (2014). Protein abundance of clinically relevant multidrug transporters along the entire length of the human intestine. Mol. Pharm. 11, 3547–3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H., Tittlemier S. A., Volkel W., Wilhelm M., Twardella D. (2009). Perfluorinated compounds–exposure assessment for the general population in Western countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 212, 239–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuis S. J., Birkholz D., Ralitsch M., Thibault N. (2010). Human detoxification of perfluorinated compounds. Public Health 124, 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuis S.J., Curtis L., Birkholz D. (2013). Gastrointestinal Elimination of Perfluorinated Compounds Using Cholestyramine and Chlorella pyrenoidosa. ISRN Toxicol. 2013:657849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenbuch B., Dawson P. (2004). The sodium bile salt cotransport family SLC10. Pflugers Arch. 447, 566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenbuch B., Meier P. J. (1994). Molecular Cloning, Chromosomal Localization, and Functional Characterization of a Human Liver Na+ Bile Acid Cotransporter. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1326–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Nabb D. L., Russell M. H., Kennedy G. L., Rickard R. W. (2012). Renal elimination of perfluorocarboxylates (PFCAs). Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Yang C. H., Snajdr S. I., Nabb D. L., Mingoia R. T. (2008). Uptake of perfluorooctanoate in freshly isolated hepatocytes from male and female rats. Toxicol. Lett. 181, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K. H., Hashida S., Kaneko T., Takenaka K., Minata M., Inoue K., Saito N., Koizumi A. (2007). Biliary excretion and cerebrospinal fluid partition of perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctane sulfonate in humans. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 24, 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R. H., Tirona R. G., Leake B. F., Glaeser H., Lee W., Lemke C. J., Wang Y., Kim R. B. (2006). Drug and bile acid transporters in rosuvastatin hepatic uptake: function, expression, and pharmacogenetics. Gastroenterology 130, 1793–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde M., De Silva A. O., Muir D. C., Letcher R. J. (2011). Monitoring of perfluorinated compounds in aquatic biota: an updated review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7962–7973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. D., Gibson S. J., Ober R. E. (1984). Cholestyramine-enhanced fecal elimination of carbon-14 in rats after administration of ammonium [14C]perfluorooctanoate or potassium [14C]perfluorooctanesulfonate. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 4, 972–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrman A., Domingo J.L., Llebaria X., Nadal M., Bigas E., van Bavel B., Lindström G. (2010). Biomonitoring perfluorinated compounds in Catalonia, Spain: concentrations and trends in human liver and milk samples. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 17, 750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Wong L. Y., Jia L. T., Kuklenyik Z., Calafat A. M. (2011). Trends in exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. Population: 1999-2008. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 8037–8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstner-Wood C., Coward L., Gorman G. (2003). Protein binding of perfluorobutane sulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate to plasma (human, rat, and monkey), and various human-derived plasma protein fractions. In (Southern Research Corporation, Study 9921.7. US EPA docket AR-226-1354. US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Kissa E., Kissa E. (2001). Fluorinated surfactants and repellents. 2nd ed Marcel Dekker, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kullak-Ublick G. A., Glasa J., Boker C., Oswald M., Grutzner U., Hagenbuch B., Stieger B., Meier P. J., Beuers U., Kramer W., et al. (1997). Chlorambucil-taurocholate is transported by bile acid carriers expressed in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Gastroenterology 113, 1295–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestri L., Negri S., Ferrari M., Ghittori S., Fabris F., Danesino P., Imbriani M. (2006). Determination of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctanesulfonate in human tissues by liquid chromatography/single quadrupole mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 20, 2728–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier P. J., Stieger B. (2002). Bile salt transporters. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 635–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H., Hirata T., Terada T., Jutabha P., Miura D., Harada K. H., Inoue K., Anzai N., Endou H., Inui K., Kanai Y., Koizumi A. (2008). Roles of organic anion transporters in the renal excretion of perfluorooctanoic acid. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 103, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen G. W., Burris J. M., Ehresman D. J., Froehlich J. W., Seacat A. M., Butenhoff J. L., Zobel L. R. (2007). Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate,perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 1298–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen G. W., Chang S. C., Noker P. E., Gorman G. S., Ehresman D. J., Lieder P. H., Butenhoff J. L. (2009). A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS) in rats, monkeys, and humans. Toxicology 256, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder A., Eckhardt U., Stieger B., Tynes R., Schteingart C. D., Hofmann A. F., Meier P. J., Hagenbuch B. (1998). Substrate specificity of the rat liver Na+-bile salt cotransporter in Xenopus laevis oocytes and in CHO cells. Am. J. Physiol. 274, G370–G375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seacat A. M., Thomford P. J., Hansen K. J., Clemen L. A., Eldridge S. R., Elcombe C. R., Butenhoff J. L. (2003). Sub-chronic dietary toxicity of potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate in rats. Toxicology 183, 117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundström M., Chang S. C., Noker P. E., Gorman G. S., Hart J. A., Ehresman D. J., Bergman A., Butenhoff J. L. (2012). Comparative pharmacokinetics of perfluorohexanesulfonate (PFHxS) in rats, mice, and monkeys. Reprod. Toxicol. 33, 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters H.C., Craddock A.L., Fusegawa H., Willingham M.C., Dawson P.A. (2000). Expression, transport properties, and chromosomal location of organic anion transporter subtype 3. Am. J. Physiol. 279, G1188–G1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Y. M., Ehresman D. J., Butenhoff J. L., Hagenbuch B. (2010). Roles of rat renal organic anion transporters in transporting perfluorinated carboxylates with different chain lengths. Toxicol. Sci. 113, 305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., Francis H., Glaser S., Alpini G., LeSage G. (2006). Bile acid interactions with cholangiocytes. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 3553–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., McGill M. R., Dorko K., Kumer S. C., Schmitt T. M., Forster J., Jaeschke H. (2014). Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced cell death in primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 279, 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. H., Glover K. P., Han X. (2010). Characterization of cellular uptake of perfluorooctanoate via organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1A2, organic anion transporter 4, and urate transporter 1 for their potential roles in mediating human renal reabsorption of perfluorocarboxylates. Toxicol. Sci. 117, 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. G., Wong C. K., Wong M. H. (2012). Environmental contamination, human exposure and body loadings of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), focusing on Asian countries. Chemosphere 89, 355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.