Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium yongonense, as a novel member of the M. avium complex (MAC), was recently reported to be isolated from human specimens in South Korea and Italy. Due to its close relatedness to other MAC members, particularly M. intracellulare in taxonomic aspects, the development of a novel diagnostic method for its specific detection is necessary for clinical or epidemiologic purposes.

Methods

Using the Mycobacterium yongonense genome information, we have identified a novel IS-element, ISMyo2. Targeting the ISMyo2 sequence, we developed a real-time PCR method and applied the technique to Mycobacterial genomic DNA.

Results

To identify proper nucleic acid targets for the diagnosis, comparisons of all insertion sequence (IS) elements of 3 M. intracellulare and 3 M. yongonense strains, whose complete genome sequences we reported recently, led to the selection of a novel target gene, the M. yongonense-specific IS element, ISMyo2 (2,387 bp), belonging to the IS21 family. Next, we developed a real-time PCR method using SYBR green I for M. yongonense-specific detection targeting ISMyo2, producing a 338-bp amplicon. When this assay was applied to 28 Mycobacterium reference strains and 63 MAC clinical isolates, it produced amplicons in only the 6 M. yongonense strains, showing a sensitivity of 100 fg of genomic DNA, suggesting its feasibility as a diagnostic method for M. yongonense strains.

Conclusions

We identified a novel ISMyo2 IS element belonging to the IS21 family specific to M. yongonense strains via genome analysis, and a real-time PCR method based on its sequences was developed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1978-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mycobacterium yongonense, Insertion sequence (IS) element, ISMyo2, Real-time PCR, Diagnostic marker

Background

Members of the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), which are responsible for opportunistic infections, particularly in AIDS patients, are the most important nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in clinical or epidemiological contexts. Traditionally, the MAC includes two species, M. avium and M. intracellulare [1–3]. In addition to these 2 species, recent advances in molecular taxonomy have fuelled the identification of novel species within the MAC [4–9].

Among these species, our group introduced the novel species Mycobacterium yongonense, which is phylogenetically related to M. intracellulare and was isolated from a Korean patient with pulmonary symptoms [10]. Notably, the RNA polymerase β subunit gene (rpoB) sequence of M. yongonense is identical to that of M. parascrofulaceum, a distantly related scotochromogen, suggesting acquisition of the rpoB gene via a potential lateral gene transfer (LGT) event [11–13]. Recently, Tortoli et al. reported pulmonary disease caused by M. yongonense strains isolated from patients in Italy. However, this strain notably harbors rpoB sequences almost identical to those of M. intracellulare but not to those of M. parascrofulaceum, suggesting the possibility of the existence of another group of M. yongonense strains that were not subject to the LGT event involving the rpoB gene from M. parascrofulaceum [14]. Furthermore, the potential of its misidentification has recently been proposed [15]. Therefore, the development of a novel diagnostic method for the precise identification of clinical strains of M. yongonense is necessary.

Insertion sequence (IS) elements have several traits of great interest in relation to epidemiological evaluations, taxonomic studies and diagnostic purposes. Depending on the degree of mobility and the copy number of IS elements, DNA fingerprints based on Southern blotting and hybridization can be used to infer strain relatedness [16]. For mycobacterial IS elements, it has generally been accepted that genetic rearrangement due to their insertion may frequently be limited to the species or subspecies level [17–20]. This specificity has led to the use of IS elements as markers for mycobacterial diagnosis, such as IS6110 for the detection of M. tuberculosis [19], or IS900 for the detection of M. paratuberculosis [21].

The aim of the present study is to develop a novel real-time PCR method targeting IS elements for the specific detection of M. yongonense. To this end, we first sought to identify the most appropriate IS element for use as a diagnostic target via comparison of the entire IS elements of 3 strains of M. intracellulare [ATCC 13950T (NC_016946), MOTT-02 (NC_016947), and MOTT-64 (NC_016948)] and 3 strains of M. yongonense [DSM 45126T (NC_020275), MOTT-H4Y (AKIG00000000) and MOTT-36Y (NC_017904)], whose complete genome sequences were recently reported by our group [12, 22–26]. Firstly, the two M. yongonense strains, MOTT-H4Y and MOTT-36Y had been identified as M. intracellulare INT 5 group [27]. However, our complete genome based phylogenetic analysis proved they belonged into M. yongonense rather than M. intracellulare (data not shown).

Results

Characterization of the ISMyo2 IS element specific to M. yongonense

To select IS elements specific to M. yongonense strains for the diagnosis of M. yongonense, we compared the distributions of IS elements/transposase sequences between 3 M. yongonense strains (DSM 45126T, MOTT-36Y, and MOTT-H4Y) and 4 other MAC strains (M. avium 104, 3 strains of M. intracellulare: ATCC 13950, MOTT-02, and MOTT-64) via analysis of the seven retrieved mycobacterial genomes (Table 1). We identified a total of 56, 40 and 53 IS elements in M. yongonense DSM 45126T, M. yongonense MOTT-36Y, and M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y, respectively, using the IS finder program (Additional file 1). In the case of M. yongonense DSM 45126T, 12 types of IS families (IS5, IS21, IS30, IS110, IS256, IS481, IS607, IS630, IS1380, IS1634, ISL3, and ISNCY) were identified in the genome. Through comparison of the distributions of IS elements among the 7 retrieved mycobacterial genome sequences, seven IS elements (ISMyo2, IS5376, ISMysp3, ISAcl1, ISMch6, ISMav2, and IS1602) were identified which found in only the genomes of M. yongonense strains. Among these IS elements, we finally targeted an ISMt2- like IS element belonging to the IS21 family, designated ISMyo2, which was found in only the 3 M. yongonense strains, and not in other examined strains (Additional file 2).

Table 1.

Genome sequences used in this study

| Strains | GenBank No. | Genome size (bp) | G + C ratio | CDS | tRNA | INT-group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. intracellulare ATCC 13950T | NC_016946 | 5,402,402 | 68.10 | 5,145 | 47 | INT2 |

| M. intracellulare MOTT-02 | NC_016947 | 5,409,696 | 68.10 | 5,151 | 47 | INT2 |

| M. intracellulare MOTT-64 | NC_016948 | 5,501,090 | 68.07 | 5,251 | 46 | INT1 |

| M. yongonense DSM 45126T | NC_020275 | 5,521,023 | 67.95 | 5,147 | 47 | INT5 |

| M. yongonense MOTT-36Y | NC_017904 | 5,613,626 | 67.91 | 5,128 | 46 | INT5 |

| M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y | AKIG00000000 | 5,443,025 | 68.08 | 5,020 | 48 | INT5 |

| M. avium 104 | NC_008595 | 5,475,491 | 68.99 | 5,120 | 46 | - |

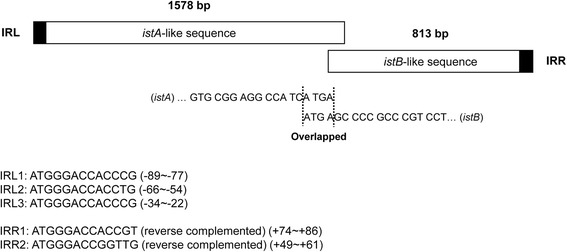

As shown for other IS elements of the IS21 family [28], the M. yongonense-specific IS elements also exhibit two consecutive open reading frames: a long upstream frame, designated istA (1,578-bp), and a shorter downstream frame, designated istB (813-bp). istA- and istB-like sequences overlap between the stop codon of istA and the start codon of istB. Additionally, upstream and downstream of the two overlapping ORFs, there are three left inverted repeat (IRL) sequences (IRL1: ATGGGACCACCCG, IRL2: ATGGGACCACCTG, IRL3: ATGGGACCACCCG) and two right inverted repeat (IRR) sequences (IRR1: ATGGGACCACCGT, IRR2: ATGGGACCGGTTG) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the sequence of the M. yongonense-specific IS elements ISMyo2. For the istA-like and istB-like sequences, the stop and start codons overlap. Three left inverted repeat (IRL) sequences were found upstream of the istA-like sequence, and two right inverted repeat (IRR) sequences were found downstream of istB-like sequence

A BLAST database search at the protein level revealed that istA- and istB- like sequences from Saccharopolyspora spinosa show sequence identities of 76.4 % (396/518) and 76.4 % (204/267), respectively, with those of ISMyo2. However, no mycobacterial IS elements matching ISMyo2 were found (data not shown). Based on these findings, the IS element identified in the M. yongonense strains was considered a putative novel IS element belonging to the IS21 family and was designated ISMyo2 according to the nomenclature suggested by Mahillon and Chandler [29], and its GenBank accession No. is KP861986.

The copy numbers of ISMyo2 in the genomes of the 3 M. yongonense strains, DSM 45126T, MOTT-36Y, and MOTT-H4Y, were 6, 5 and 4, respectively (Additional files 2 and 3). Exceptionally, in the genome of M. yongonense MOTT-36Y, a copy of ISMyo2 (W7S_12150) was identified, but there was no stop codon between the istA- and istB-like sequences. Additionally, in the case of M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y, a copy of ISMyo2 included only an istB-like sequence (W7U_06705), and no istA-like sequences (Additional file 3).

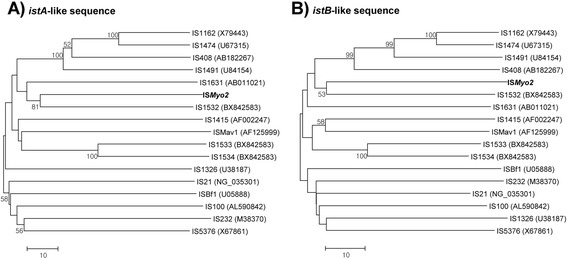

For comparison with other IS elements related to the IS21 family, 16 additional IS element sequences were retrieved from the GenBank database and compared with the istA- and istB-like sequences of ISMyo2. ISMyo2 clustered together with IS1532 from M. tuberculosis for two ORFs, though they showed low sequence similarity at the amino acid level (33.5 % for the istA sequence and 34.3 % for the istB sequence) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic trees based on (a) istA-like sequences and (b) istB-like sequences from M. yongonense DSM 45126T and 16 other bacteria. The trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 replications, and values of <50 are not indicated in the trees. The bars indicate the numbers of substitutions per amino acid position

The phylogenetic tree based on the istA- and istB-like sequences from the M. yongonense strains showed the presence of four different groups (Additional file 4). In the case of M. yongonense DSM 45126T, the observed ISMyo2 sequences were highly conserved in the genome. However, those of M. yongonense MOTT-36Y or MOTT-H4Y showed variations in the genomes. For the istA sequence (1,578 bp), the sequence homologies between the 6 alleles of M. yongonense DSM 45126T, the 5 alleles of M. yongonense MOTT-36Y, and the 4 alleles of M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y ranged from 99.7 to 100.0 %, from 75.6 to 100.0 %, and from 81.1 to 99.9 %, respectively. For the istB sequence (813 bp), the sequence homologies between the 6 alleles of M. yongonense DSM 45126T, the 5 alleles of M. yongonense MOTT-36Y, and the 4 alleles of M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y were 100 %, from 79.2 to 100.0 %, and from 84.7 to 100.0 %, respectively.

Development of a real-time PCR assay targeting ISMyo2 for the detection of M. yongonense strains

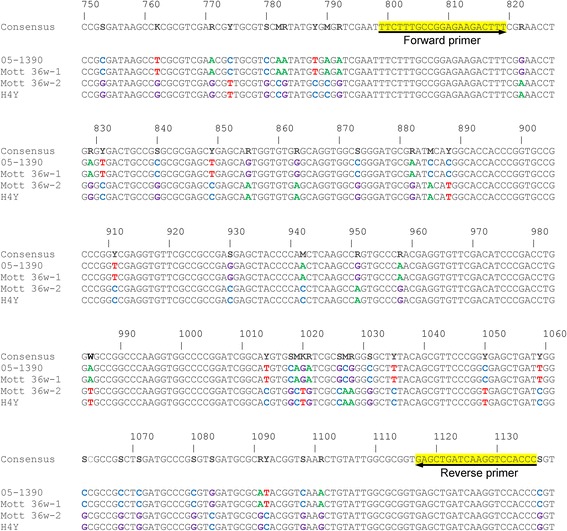

To develop appropriate primer sets based on ISMyo2 sequences for the specific amplification of M. yongonense strains, ISMyo2 sequences from a total of 15 copies from the genomes of 3 M. yongonense strains were compared. Finally, we designed a primer set targeting sequences that are conserved in all 15 copies of ISMyo2, producing 338-bp amplicons (from the 799th to the 1136th nucleotide of the ISMyo2 sequence of M. yongonense DSM 45126T ) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Primers designed for the identification of Myocbacterium yongonense on the basis of ISMyo2 sequence alignment for M. yongonense strains. Arrows indicate the primer positions. The numbers indicate the nucleotide positions in the istA-like sequence of ISMyo2 of M. yongonense. Boldface bases denote the bases that differ from those in the consensus sequence. The strains included in this analysis were as follows: M. yongonense DSM 45126T; M. yongonense MOTT-36Y; and M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y

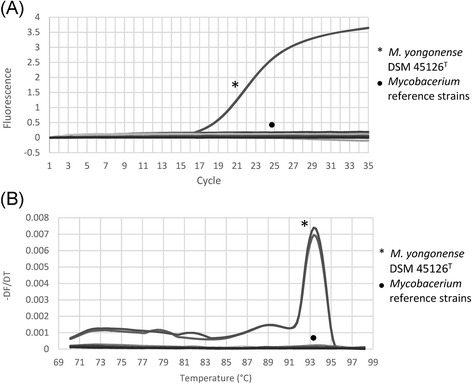

Specificity of the diagnostic assays

The specificity of the real-time PCR assay developed for the identification of M. yongonenese was tested in 28 reference strains of mycobacteria via Cq and melting curve analyses. Three M. yongonense strains (DSM 45126T, MOTT-36Y, and MOTT-H4Y) were specifically identified through measurement of Cq and Tm (~93 °C), whereas none of the 25 other reference strains showed any detectable Cqs or melting temperatures (Additional file 5, Fig. 4). The real-time PCR assay was then applied to 63 clinical isolates, including a number of MAC species; again, only the 3 M. yongonense strains were identified, and not the 60 other clinical MAC isolates (M. intracellulare INT-1: 35 strains, M. intracellulare INT-2: 16 strains, M. intracellulare INT-3: 1 strain, M. avium: 8 strains and M. chimaera: 1 strain), based on the measurement of Cqs and specific Tms (~93 °C) (Additional files 6, 7A and B). Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of the real-time PCR products of 6 M. yongonense strains (3 reference and 3 clinical strains) revealed a single electrophoretic band of the predicted size (338 bp) (Additional file 7C).

Fig. 4.

Specificity test for the real-time PCR assay developed for the identification of M. yongonense with using 28 reference strains of Mycobacterium species. M. yongonense was specifically identified based on Cq and melting temperature measurements. The tested strains are the same as those listed in Additional file 5 and were tested in duplicate via SYBR Green I real-time PCR. a, amplification curves; b, melting curve analysis

Sensitivity of the diagnostic assays

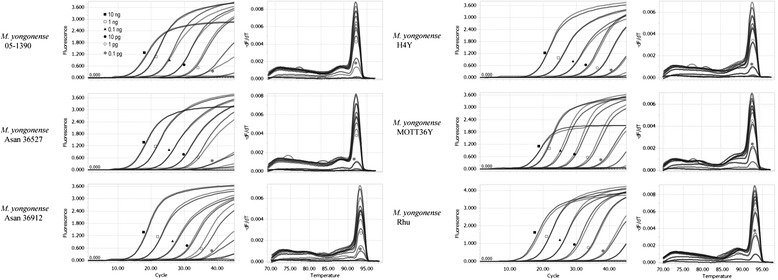

To determine the detection limits of the real-time PCR assay for the detection of M. yongonense strains, serially diluted DNA from all 6 strains of the tested M. yongonense (3 reference and 3 clinical strains) was subject to real-time PCR. The detection limit of the real-time PCR assay for M. yongonense species was 10 fg of genomic DNA in one strain (Rhu) and 0.1 pg in all of the other tested strains (Additional file 8, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of the detection limits of the real-time PCR assay for the identification of M. yongonense species. All of the strains of M. yongonense species tested were detected, using as little as 0.1 pg of their genomic DNA

Discussion

Among the members of the MAC complex, for the diagnosis and epidemiology of 4 M. avium subspecies (M. avium subsp. hominissuis, M. avium subsp. avium, M. avium subsp. silvaticum and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis), at least four major IS elements have been widely used, namely IS1245, IS1311, IS900 and IS901 [30]. However, despite the increases in global clinical cases and in the species diversity of M. intracellulare-related strains, the description of IS elements for their diagnosis and epidemiology has rarely been reported thus far. In this study, we first introduced a novel IS element, ISMyo2, specific to M. yongonense strains, which belong to the M. intracellulare-related species. This element can be used for the diagnosis and epidemiology of these strains, particularly to resolve the current taxonomic need of selectively discriminating M. yongonense from other M. intracellulare related strains.

In this study, genome analysis using IS finder revealed the presence of a total of 56 IS elements and IS-like elements, consisting of at least 12 types of IS families, in the genome of M. yongonense DSM 45126T. Of these IS elements, a total of 7 were shown to be present in only the genomes of 3 M. yongonense strains, and were absent in the genomes of 3 M. intracellulare strains (Additional file 2). However, considering the copy numbers, BLAST search results, and sequence conservation between IS alleles in a genome, we finally selected ISMyo2, belonging to the IS21 family, as a target IS element for the diagnosis of M. yongonense strains.

It is worth noting several characteristic features of ISMyo2 that make it a useful diagnostic marker for M. yongonense. The first is the high specificity of ISMyo2 for M. yongonense. To date, 4 types of IS21 family members have been described in the genus Mycobacterium, three in M. tuberculosis (IS1532, IS1533 and IS1534) [31] and one in M. avium (ISMav1) [30]. Despite belonging to the IS21 family, the ISMyo2 element identified in this study shows a very low level of sequence homology with other IS21 members from mycobacteria, particularly in terms of DNA sequences, suggesting the feasibility of using ISMyo2 as a diagnostic marker for M. yongonense. Furthermore, the application of a real-time PCR assay targeting ISMyo2 in reference mycobacterial strains demonstrated that the assay was specific to only M. yongonense strains (Fig. 4, Additional file 5). Furthermore, it did not produce any amplicons in any of the 61 examined M. intracellulare clinical isolates, which included diverse genotypes such as INT-1, INT-2 and INT-3, which are closely related to M. yongonense (Additional files 6 and 7).

Second, the ISMyo2- targeting assay was able to detect 2 types of M. yongonense variants. Our genome analysis revealed that ISMyo2 is also present in the genomes of 2 strains of M. yongonense, MOTT-36Y and MOTT-H4Y, which were previously designated as the M. intracellulare INT-5 genotype, as well as in genome of M. yongonense DSM 45126T. Although two INT-5 strains exhibit rpoB sequences identical to that of M. intracellulare but not to that of M. parascrofulaceum, our phylogenetic analysis based on complete genome sequences showed that these strains and M. yongonense DSM 45126T are tightly clustered and are separated from other M. intracellulare strains (data not shown), suggesting that they may be members of the same species, M. yongonense. Our results also strongly supported the hypothesis previously put forth by Tortoli et al. [14] that there may be at least two variants in M. yongonense strains, one of which was subjected to the rpoB LGT event from M. parascrofulaceum, including strains such as M. yongonense DSM 45126T, and another, phylogenetically older variant, that was not subject to the rpoB LGT, including strains such as the INT-5 strains MOTT-36Y and MOTT-H4Y.

Third, the ISMyo2 targeting assay exhibited high sensitivity in detecting M. yongonense strains. Our genome analysis showed that more than 4 copies of ISMyo2 are present in M. yongonense genomes (Additional files 3 and 4). Furthermore, the sequence conservation between the ISMyo2 alleles found in the M. yongonense genomes facilitated the development of a common primer set capable of PCR amplification of all of these alleles (Fig. 3). Thus, we successfully developed a real-time PCR assay capable of PCR amplification of all of the alleles via performing multiple sequence alignments of 15 ISMyo2 alleles from the genomes of 3 M. yongonense strains. Our real-time PCR assay can detect PCR amplicons at a DNA level of 100 fg in all 6 M. yongonense strains (Fig. 5, Additional file 8), suggesting its feasibility as a diagnostic method for M. yongonense strains.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we identified a novel ISMyo2 IS element belonging to the IS21 family that is specific to M. yongonense strains via genome analysis and developed a real-time PCR method based on its sequences.

Methods

Genome sequences used in this study

Seven mycobacterial genome sequences, from strains belonging to the M. avium complex (3 M. intracellulare strains: ATCC 13950T, MOTT-02, and MOTT-64; 3 M. yongonense strains: DSM 45126T, MOTT-36Y, and MOTT-H4Y; and one M. avium strain: M. avium 104) were retrieved from the GenBank database (Table 1) and used for comparative analysis of IS-elements.

Mycobacterial strains

Twenty-eight mycobacterial reference strains (Additional file 5) and 63 clinical isolates (Additional file 6) were used in this study. Twenty-three of the 28 mycobacterial reference strains (with the exception of M. massiliense KCTC 19086T and 3 M. yongonense strains, DSM 45126T, MOTT-H4Y, MOTT-36Y and M. tuberculosis ATCC 27294T) were provided by the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis (KIT). In the case of M. tuberculosis ATCC 27294T, genomic DNA of M. tuberculosis was provided from the KIT. The M. massiliense KCTC 19086T strain was provided by the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC), and the three M. yongonense strains, DSM 45126T, MOTT-H4Y and MOTT-36Y, were from Seoul National University College of Medicine (SNUMC). No ethics approval was required for the bacterial isolates in this study.

Analysis of insertion sequence (IS) elements

Using the sequence information from the seven mycobacterial genomes, and especially the information on annotated genes, IS elements from each genome were identified. IS elements from M. yongonense DSM 45126T were identified using a default parameter of the IS-finder tool (http://www-is.biotoul.fr) [32] and compared with IS elements from the other six mycobacterial genome sequences using the MegAlign (DNASTAR package, http://www.dnastar.com/t-megalign.aspx) [33] and BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) programs. To identify terminal inverted repeat (IR) sequences, upstream and downstream sequences of the targeted M. yongonense-specific IS element were analyzed using the Spectral Repeat Finder tool (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/srf/) with default parameters except for a parameter of ‘minimum number of copies’ (we used this parameter value with 2, the default value was 5) [34].

Phylogenetic analysis

The identified novel IS element ISMyo2 was compared with the IS elements from 2 other M. yongonense strains (M. yongonense MOTT-36Y and M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y) and 16 known IS elements belonging to the IS21 family. Amino acid or nucleotide sequences were aligned using the ClustalW method in MEGA 4 software [35]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method [36] and maximum composite likelihood (in the case of nucleotide sequences) or number of differences substitution models (in the case of amino acid sequences) in MEGA 4 software [35]. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 replications.

DNA extraction

To prepare genomic DNA from reference or clinical isolated mycobacteria, strains were cultured on the 7H10 agar plate (supplemented with OADC) for 7 to 10 days in the 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from single colonies of the clinical isolates via the bead beater–phenol extraction method as described previously [37].

Primer design

A set of primers [forward primer, 5′-TTCTTTGCCGGAGAAGACTTT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GGGTGGACCTTGATCAGCTC-3′] was designed to produce a 338-bp ISMyo2 amplicon (from the 799th to 1136th nucleotide in the M. yongonense DSM 45126T ISMyo2 sequence) from all strains of M. yongonense using Oligo V 6.5 (Molecular Biology Insights).

Real-time PCR

The LightCycler 96 system was used for real-time PCR. A 10 μl reaction mixture was prepared for each sample, with the following components: 1 μl of Taq buffer (including 20 mM MgCl2) supplied together with Ex Taq HS (Takara), 0.25 μM forward primer, 0.25 μM reverse primer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.7 mg/ml BSA (NEB), 0.5 × SYBR Green I (Sigma S9430), 3 % DMSO, 0.25 U of ExTaq HS, and sterile distilled water. The cycling conditions were 2 min at 95 °C and 5 s at 98 °C, followed by 35 or 45 cycles of 10 s at 98 °C, 10 s at 64 °C and 40 s at 72 °C (single acquisition of fluorescence signals). Melting curve analysis was performed as follows: 10 s at 98 °C and 1 min at 70 °C, after which the temperature was increased from 70 °C to 98 °C at a temperature transition rate of 0.2 °C/s, with continuous acquisition of the fluorescence signal. Quantification cycles (Cqs) and amplicon melting temperatures (Tms) were measured using LightCycler 96 system software, V1.1. The Tm specificity was verified via duplicate real-time PCR measurements with a panel of reference mycobacterial DNAs. A total of 63 clinical isolates were subsequently tested for the identification of M. yongonense species. The detection limit of the real-time PCR assay for M. yongonense was tested in duplicate using serially diluted genomic DNA from 10 ng to 10 fg.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files (Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Acknowledgments

Byoung-Jun Kim and Kijeong Kim, equally contributed to this work.

Funding

This study was financially supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Grant No., NRF-2014R1A1A2004008) and a grant (Grant No., HI13C15620000) from Korean Healthcare Technology R&D project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- BLAST

bagic local alignment search tool

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- Cq

quantification cycle

- dNTP

deoxynucleotide triphosphate

- fg

femto gram

- IR

inverted repeat

- IRL

left inverted repeat

- IRR

right inverted repeat

- IS element

insertion sequence element

- KCTC

Korean Collection for Type Culture

- KIT

Korean Institute of Tuberculosis

- LGT

lateral gene transfer

- MAC

Mycobacterium avium complex

- ng

nano gram

- NTM

nontuberculous mycobacteria

- ORF

open reading frame

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- pg

pico gram

- rpoB

RNA polymerase β subunit gene

- SNUMC

Seoul National University College of Medicine

Additional files

Distributions of IS-element/transposase in M. avium complex strains. (XLSX 8 kb)

Distributions of IS-elements from M. yongonense and other M. intracellulare strains. (XLSX 10 kb)

IS Myo2 elements in the genomes of M. yongonense DSM 45126 T, M. yongonense MOTT-36Y and M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y. (XLSX 10 kb)

Phylogenetic tree based on (A) istA -like sequences and (B) istB -like sequences from M. yongonense DSM 45126 T, M. yongonense MOTT-36Y and M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y. IS-elements of M. tuberculosis were used as an outgroup. The trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 replications and <50 were not indicated. The bars indicate numbers of substitutions per nucleotide position. (PDF 76 kb)

Mycobacterial reference strains used in the present study and specificity of real-time PCR for the detection of the insertion sequence specific to Mycobacterium yongonense. (XLSX 11 kb)

Identification of the insertion sequence specific to M. yongonense among clinical isolates by real-time PCR. (XLSX 12 kb)

Real-time PCR identification of M. yongonense from clinical isolates of Mycobacterium species. All the M. yongonense species among the clinical isolates tested were specifically identified by measurement of their Cqs and melting temperatures. The clinical isolates tested are the same ones listed in Additional file 2 and were tested in duplicate by SYBR Green I real-time PCR. (A) amplication curves. (B) melting curve analysis. (C) agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of real-time PCR products. M, 100 bp DNA marker; 1, M. yongonense DSM 45126T; 2, M. yongonense Asan 36527; 3, M. yongonense Asan 36912; 4, M. yongonense MOTT-H4Y; 5, M. yongonense MOTT-36Y; 6, M. yongonense Rhu; 7, negative control. (PDF 250 kb)

Limit of detection of real-time PCR for the identification of the insertion sequence specific to M. yongonense. (XLSX 10 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare non-financial competing interests.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

BJK (Byoung-Jun Kim) and BRK carried out IS element and phylogenetic analysis. KK carried out real-time PCR and interpretation the data. YHK helped to draft the manuscript. BJK (Bum-Joon Kim) conceived of the study, participated in study design and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Byoung-Jun Kim, Email: arukas22@snu.ac.kr.

Kijeong Kim, Email: kimkj@cau.ac.kr.

Bo-Ram Kim, Email: blast3br@naver.com.

Yoon-Hoh Kook, Email: yhkook@snu.ac.kr.

Bum-Joon Kim, Phone: (82) 2-740-8316, Email: kbumjoon@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Falkinham JO., 3rd Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(2):177–215. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inderlied CB, Kemper CA, Bermudez LE. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6(3):266–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turenne CY, Wallace R, Jr, Behr MA. Mycobacterium avium in the postgenomic era. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):205–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang D, Herlin T, Stegger M, Andersen AB, Torkko P, Tortoli E, et al. Mycobacterium arosiense sp. nov., a slowly growing, scotochromogenic species causing osteomyelitis in an immunocompromised child. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58(Pt 10):2398–2402. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben Salah I, Cayrou C, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Mycobacterium marseillense sp. nov., Mycobacterium timonense sp. nov. and Mycobacterium bouchedurhonense sp. nov., members of the Mycobacterium avium complex. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59(Pt 11):2803–2808. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.010637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murcia MI, Tortoli E, Menendez MC, Palenque E, Garcia MJ. Mycobacterium colombiense sp. nov., a novel member of the Mycobacterium avium complex and description of MAC-X as a new ITS genetic variant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56(Pt 9):2049–2054. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saini V, Raghuvanshi S, Talwar GP, Ahmed N, Khurana JP, Hasnain SE, et al. Polyphasic taxonomic analysis establishes Mycobacterium indicus pranii as a distinct species. Plos One. 2009;4(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tortoli E, Rindi L, Garcia MJ, Chiaradonna P, Dei R, Garzelli C, et al. Proposal to elevate the genetic variant MAC-A, included in the Mycobacterium avium complex, to species rank as Mycobacterium chimaera sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt 4):1277–1285. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02777-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Ingen J, Boeree MJ, Kosters K, Wieland A, Tortoli E, Dekhuijzen PNR, et al. Proposal to elevate Mycobacterium avium complex ITS sequevar MAC-Q to Mycobacterium vulneris sp nov. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2009;59:2277–2282. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.008854-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim BJ, Math RK, Jeon CO, Yu HK, Park YG, Kook YH, et al. Mycobacterium yongonense sp. nov., a slow-growing non-chromogenic species closely related to Mycobacterium intracellulare. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63(Pt 1):192–199. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.037465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BJ, Hong SH, Kook YH, Kim BJ. Molecular evidence of lateral gene transfer in rpoB gene of Mycobacterium yongonense strains via multilocus sequence analysis. Plos One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BJ, Kim BR, Lee SY, Seok SH, Kook YH, Kim BJ. Whole-Genome Sequence of a Novel Species, Mycobacterium yongonense DSM 45126T. Genome Announc. 2013;1(4):e00604-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00604-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Kim BJ, Kim BR, Kook YH. The development of a novel Mycobacterium-Escherichia coli shuttle vector system using pMyong2, a linear plasmid from Mycobacterium yongonense DSM 45126T. PloS one. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tortoli E, Mariottini A, Pierotti P, Simonetti TM, Rossolini GM. Mycobacterium yongonense in pulmonary disease. Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11):1902–1904. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SK, Kim EC. Possible misidentification of Mycobacterium yongonense. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(6):1089–1090. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.131508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisercic M, Ochman H. The ancestry of insertion sequences common to Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175(24):7863–7868. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7863-7868.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale JW. Mobile genetic elements in mycobacteria. Eur Respir J. 1995;20:633s–648s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunze ZM, Portaels F, McFadden JJ. Biologically distinct subtypes of Mycobacterium avium differ in possession of insertion sequence IS901. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(9):2366–2372. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2366-2372.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall S, Ghanekar K, McFadden J, Dale JW. Context-sensitive transposition of IS6110 in mycobacteria. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 11):3169–3176. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittington R, Marsh I, Choy E, Cousins D. Polymorphisms in IS1311, an insertion sequence common to Mycobacterium avium and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, can be used to distinguish between and within these species. Mol Cell Probes. 1998;12(6):349–358. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1998.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green EP, Tizard ML, Moss MT, Thompson J, Winterbourne DJ, McFadden JJ, et al. Sequence and characteristics of IS900, an insertion element identified in a human Crohn's disease isolate of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(22):9063–9073. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim BJ, Choi BS, Choi IY, Lee JH, Chun J, Hong SH, et al. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium intracellulare clinical strain MOTT-36Y, belonging to the INT5 genotype. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(15):4141–4142. doi: 10.1128/JB.00752-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim BJ, Choi BS, Lim JS, Choi IY, Kook YH, Kim BJ. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium intracellulare clinical strain MOTT-64, belonging to the INT1 genotype. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(12):3268. doi: 10.1128/JB.00471-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim BJ, Choi BS, Lim JS, Choi IY, Lee JH, Chun J, et al. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium intracellulare clinical strain MOTT-02. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(10):2771. doi: 10.1128/JB.00365-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim BJ, Choi BS, Lim JS, Choi IY, Lee JH, Chun J, et al. Complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium intracellulare strain ATCC 13950(T) J Bacteriol. 2012;194(10):2750. doi: 10.1128/JB.00295-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee H, Kim BJ, Kim K, Hong SH, Kook YH, Kim BJ: Whole-Genome Sequence of Mycobacterium intracellulare Clinical Strain MOTT-H4Y, Belonging to INT5 Genotype. Genome Announc 2013, 1(1) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00006-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Park JH, Shim TS, Lee SA, Lee H, Lee IK, Kim K, et al. Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium intracellulare-related strains based on the sequence analysis of hsp65, internal transcribed spacer and 16S rRNA genes. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59(Pt 9):1037–1043. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger B, Haas D. Transposase and cointegrase: specialized transposition proteins of the bacterial insertion sequence IS21 and related elements. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58(3):403–419. doi: 10.1007/PL00000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(3):725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rindi L, Garzelli C. Genetic diversity and phylogeny of Mycobacterium avium. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefevre P, Braibant M, Content J, Gilot P. Characterization of a Mycobacterium bovis BCG insertion sequence related to the IS21 family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178(2):211–217. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D32–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clewley JP, Arnold C. MEGALIGN. The multiple alignment module of LASERGENE. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;70:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma D, Issac B, Raghava GP, Ramaswamy R. Spectral Repeat Finder (SRF): identification of repetitive sequences using Fourier transformation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1405–1412. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Nei M, Dudley J, Tamura K. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9(4):299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim BJ, Lee SH, Lyu MA, Kim SJ, Bai GH, Chae GT, et al. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(6):1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1714-1720.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]