Abstract

Objective

To identify Chlamydia trachomatis antigens associated with tubal factor infertility and acute infection.

Methods

A C. trachomatis proteome array was used to compare antibody profiles among women with tubal factor infertility, normal fertility, and acute C. trachomatis infection.

Results

Thirteen immunodominant antigens reacted with 50% or more sera from all women (N=73). Six C. trachomatis antigens were uniquely recognized by women diagnosed with tubal factor infertility. Combining fragmentation of the six antigens with serum sample dilution, chlamydial antigens HSP60, CT376, CT557, and CT443 could discriminate between women with tubal factor infertility and women with normal fertility with a sensitivity of 63% (95% CI: 0.41–0.77) and specificity of 100% (95% CI: 0.91–1), respectively. These antigens were designated as tubal factor infertility-associated antigens. However, these tubal factor antigens were unable to distinguish tubal factor infertility patients from those with acute infection. A combination of CT875 and CT147 distinguished women with acute infection from all other C. trachomatis-exposed women with a detection sensitivity of 63% (95% CI: 0.41–0.77) and specificity of 100% (95% CI: 0.95–1), respectively. Thus, CT875 and CT147 were designated as acute infection-associated antigens.

Conclusion

A sequential screening of antibodies against panels of C. trachomatis antigens can be used to identify women with tubal factor infertility and acute C. trachomatis infection.

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis is a leading cause of sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the US, affecting over one million women in 2008 alone (1). C. trachomatis infection is often asymptomatic, and thus undiagnosed and untreated. Untreated, C. trachomatis infection may lead to ascending infection, causing complications such as ectopic pregnancy and tubal factor infertility (1, 2). However, not all women infected with C. trachomatis develop tubal damage. Women with normal fallopian tubes on laparoscopy or with normal fertility can have high titers of antibodies to C. trachomatis (3). It is unclear what determines whether a woman exposed to C. trachomatis will develop tubal pathology. Host immune responses to C. trachomatis infection are thought to contribute significantly to tubal damage.

Extensive efforts have been made to identify biomarkers that correlate with tubal factor infertility (TFI). Previous studies have revealed a strong association of anti-C. trachomatis and anti-HSP60 antibodies with TFI (3–9). Using a high-resolution whole genome protein array, we previously compared the profiles of anti-C. trachomatis antibodies between women with TFI and women with infertility due to nontubal causes and confirmed the association of HSP60 with TFI and identified new antigens associated with TFI (5). However, these and other studies focused on well-defined study groups for comparison. When more diverse patient populations were included, the anti-C. trachomatis and HSP60 antibodies were no longer able to differentiate women with tubal factor infertility from those with normal fertility and acute C. trachomatis infection (5). The goal of this study was to use a whole genome proteome array to define distinct panels of C. trachomatis antigens for predicting tubal pathology and acute infection.

Materials and Methods

All subjects were recruited at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio with Institutional Review Board approval. All participants underwent a single blood draw. Serum samples were stored at −20° C until analyzed. The tubal factor infertility (TFI) group (n=24) were recruited from a university-based infertility clinic. Inclusion criteria were subjects of at least 21 years of age with a pelvic laparoscopy demonstrating hydrosalpinx, fimbrial phimosis, or peritubal adhesions. Exclusion criteria included prior tubal ligation, surgical finding of endometriosis, or a history of pelvic infection or inflammation other than pelvic inflammatory disease, such as appendicitis. The fertile control (FC) group (n=25) were recruited from a university affiliated county hospital. FC subjects were at least 21 years of age and had at least one live birth and normal pelvic findings at the time of tubal ligation, performed either using laparoscopy or through mini-laparotomy. The sexually transmitted infection (STI) subjects (n=24) were referred by the health department to a university-based clinic after diagnosis of C. trachomatis based on positive C. trachomatis nucleic acid detection (10, 11). STI patients were of reproductive age (15–45 years of age). Phlebotomy was performed within 2 weeks of the diagnosis. Clinical characteristics of the 3 study groups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Anti-Chlamydia trachomatis Antibody Titers

| Patient Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubal Factor Infertility (n=24) | Fertile Control (n=25) | Sexually Transmitted Infection (n=24) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (years) ± SD | 32.6 ± 4.4 | 32.5 ± 5.7 | 21.8 ± 3.1 | |

| Kruskal Wallis | Tubal factor infertility vs fertile control p=0.20 |

Fertile control vs sexually transmitted infection p<0.001 |

Tubal factor infertility vs sexually transmitted infection p<0.001 |

|

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 42% | 49% | ||

| Hispanic | 46% | 51% | 31% | |

| African American | 8% | 69% | ||

| Asian | 4% | |||

| Mean (titer) ± SD | 35, 483 ± 39, 950 | 23,760 ± 23, 974 | 65500 ± 70079 | |

| Antibody* | ||||

| Kruskal Wallis† | Tubal factor infertility vs fertile control‡ p=0.525 |

Fertile control vs sexually transmitted infection‡ p=0.166 |

Tubal factor infertility vs sexually transmitted infection‡ p=0.525 |

|

SD, standard deviation.

Age, race and anti-C. trachomatis antibodies levels are shown for women in each group. Women in the acute infection group (sexually transmitted infection) were significantly younger than those in the tubal factor infertility group or the fertile control group.

Antibody titers measured against C. trachomatis organisms.

Pairwise comparisons corrected with Dunn-Šidák’s method.

P=0.06

C. trachomatis serovar D or C. pneumoniae AR39 organisms used in the current study were grown, purified, and titrated as described previously (3, 5, 12, 14). Antichlamydial organism antibodies in human sera were titrated using an immunofluorescence assay (3, 5). HeLa cells infected with C. trachomatis or C. pneumoniae organisms were used as antigens for titrating human serum samples. The human antibody binding was visualized with a goat anti-human IgG conjugated with Cy3 and the fluorescence labelings were observed and photographed with an Olympus AX70 fluorescence microscope equipped with multiple filter sets, as previously described (15, 16). The highest dilution of a serum that still gave a positive reactivity was defined as the titer of the given serum sample.

A glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein microplate ELISA-based proteome array was used to detect human antibody recognition of chlamydial proteins as previously described (10, 11). Individual chlamydial GST fusion proteins bound to 96-well microplates precoated with glutathione were used to react with human serum samples preabsorbed with a bacterial lysate containing GST alone. The human antibody reactivity was detected with a goat anti-human IgG, IgA, and IgM conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and the optical density (OD) was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader. To confirm the antibody binding specificity, all human sera were further absorbed with lysates made from either HeLa cells alone or C. trachomatis serovar D-infected HeLa cells before reacting with the fusion protein-coated plates. The antibody binding that remained positive after HeLa-alone lysate absorption but significantly reduced by Chlamydia–HeLa lysate absorption was considered true positive.

Power calculations were based on the hypothesis that the sensitivity and specificity are both greater than 0.5. If the true value of the sensitivity and specificity are both 0.8 and the significance level is 5%, then this study will attain a power of 80% with 24 subjects per group.

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2007 and R version 2.14.1. Kruskal-Wallis was used to compare anti-C. trachomatis and anti-C. pneumoniae antibody titers between all three groups of patients. Pairwise contrasts were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn-Šidák’s correction for multiple testing. Results from ELISA were analyzed using both Kruskal-Wallis (for comparing quantitative OD value data) and Fisher’s exact test (for comparing the number of sera positively reacted with a given antigen). Dunn-Šidák’s correction was used to account for multiple testing. Combination of these two methods allowed us to identify C. trachomatis antigens that are both clinically and statistically significant. When Kruskal-Wallis was used, the OD values (after subtracting background from the same plate) were used. When the Fisher’s exact test was used, positive reactivity frequency was used. A reaction was determined positive when the OD value was 2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean calculated from the same 96-well plate (5).

Results

Subjects were randomly recruited from three distinct socioeconomic and demographic groups from January 1, 2006 to June 1, 2011. The tubal factor infertility (TFI) group (n=24) were recruited from a university-based infertility clinic. The fertile control (FC) group (n=25) were recruited from a university affiliated county hospital. The sexually transmitted infection (STI) group (n=24) were referred by the health department to a university based clinic after diagnosis of C. trachomatis. Clinical characteristics of study subjects are shown in Table 1.

Serially diluted serum samples from women with TFI, FC, and STI were reacted with C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae-infected HeLa cells to measure the titers of the corresponding antibodies. STI women displayed the lowest levels of anti-C. pneumoniae antibodies (7,785 ± 6,296) compared to TFI (23,000 ± 23,084, p=0.04) and FC groups (17,136 ± 19,709, p=0.53) while TFI and FC displayed similar levels of the antibodies (p=0.25). The levels of anti-C. pneumoniae antibodies correlated well with the age among the three groups of women. STI women were significantly younger (mean age 21.8 ± 3.1 years) than both TFI (34.6 ± 4.4, p<0.001) and FC (32.5 ± 5.7, p<0.001), respectively, while the TFI and FC women displayed similar ages (p=0.20). Thus, anti-C. pneumoniae antibody levels increase with age. However, as shown in the bottom portion of Table 1, there was no significant difference in anti-C. trachomatis antibody titers between the groups (p=0.06). Titers were highest in STI group (65,500 ± 70,078) compared to those in either the TFI (35,483 ± 39,950, p=0.52) or FC groups (23,760 ± 23,974, p=0.17). There was no significant difference between TFI and FC groups (p=0.53). In contrast to the age-dependent increase in anti-C. pneumoniae antibody titers, the anti-C. trachomatis antibody titers decreased as age progressed. Contrary to previous studies using anti-C. trachomatis antibodies to differentiate TFI from infertility of nontubal causes (3, 5), we found that the overall anti-C. trachomatis antibodies were not able to differentiate TFI patients from FC or STI groups. We next used a whole genome protein array to analyze the human serum samples in order to identify antibodies able to differentiate these groups of patients.

When antibodies from 24 TFI, 25 FC, and 24 STI women were reacted with 908 C. trachomatis proteins (Fig. 1), the 73 patient sera recognized C. trachomatis antigens distributed across the entire genome (panel A) with 541 antigens recognized by at least one serum and 367 antigens not detected by any serum (B). Many C. trachomatis antigens were recognized by all 3 groups of women although some antigens were preferentially recognized by individual or combinations of groups (C). As shown in panel D, regardless of which groups the women were from, 50% or more of the 73 patient sera recognized a total of 13 antigens, including pCT03 (Pgp3, a plasmid-encoded hypothetical protein that is secreted into host cell cytosol; ref: (19, 20), CT858 (CPAF, a chlamydial protease/proteasome-like activity factor known to be secreted into host cell cytosol; ref: 13), CT101 (hypothetical protein, HP), CT841 (FtsH, ATP-dependent Zinc protease), CT240 (Recombination protein RecR), CT443 (outer membrane complex protein B, OmcB; ref: 21), CT142, and CT143 (both HPs), CT813 and CT529 (both inclusion membrane proteins, Incs; ref: 22, 23), CT694 (a putative effector of the type III secretion pathway; ref: (24), CT022 (50S ribosomal protein L31 type B), and CT806 (insulinase family/protease III, Ptr). These proteins were designated as immunodominant antigens in these women.

Fig. 1. Reactivity of 908 C. trachomatis fusion proteins with 73 sera from 3 different groups of women.

GST fusion proteins representing 908 C. trachomatis ORFs were each reacted with serum samples from women with tubal factor infertility (TFI in red, n=24), normal fertility (FC in yellow, n=25), or acute infection (STI in green, n=24). Any reaction with an OD ≥ mean + 2 SDs calculated from the same plate was determined positive, which was used to calculate positive recognition frequency (Freq). The positive OD values were expressed as binding intensity in increasing brightness of fluorescent color while the negative OD values were always in black, as indicated at the bottom of panel D. The 908 ORFs encoded by C. trachomatis genome and plasmid were listed first in order of ORFs from CT001 to pCT08 (panel A), and then in order of recognition frequency from high (H) to low (L) (panels B–D).

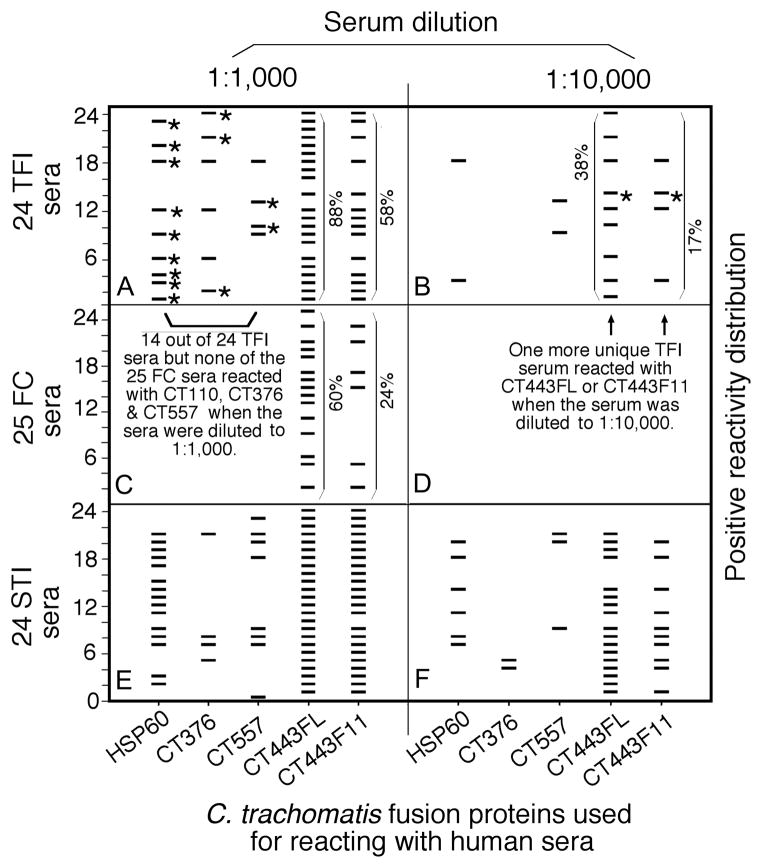

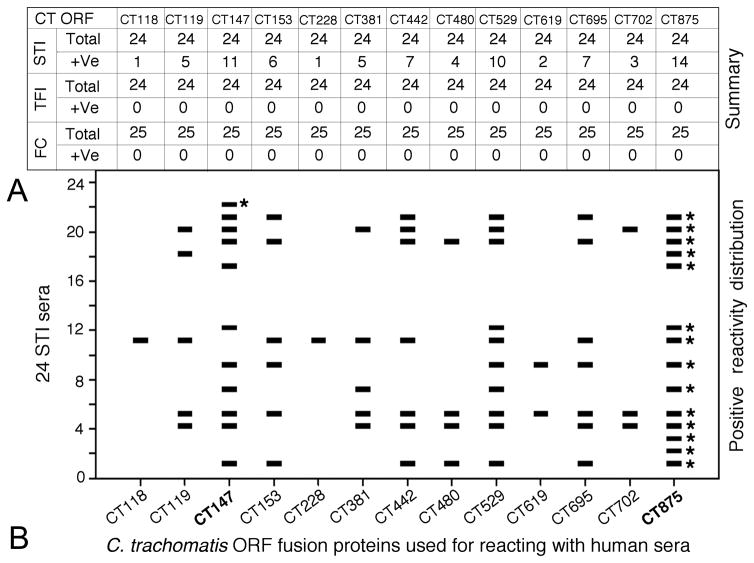

The reactivity of each of the 908 C. trachomatis antigens with 73 human sera was compared between the 3 groups of women both quantitatively (intensity as measured in OD values) and qualitatively (frequency of recognition). Antigens that displayed statistically significant differences in reactivity (either quantitatively or qualitatively) and were recognized by 10% or more of the sera from at least one group of women were selected. There were 97 antigens that met both the above requirements (data not shown). We first focused on antigens that displayed statistically significant differences in recognition by TFI versus FC women (Table 2). Among the antigens preferentially recognized by TFI sera, 5 failed to react with any sera from FC women under the serum dilution of 1:1000, suggesting that these antigens can distinguish TFI from FC women with 100% specificity. When the reactivity patterns of these 5 antigens with TFI women were revealed (Fig. 2), we found that HSP60 reacted with sera from 9 out of 24 TFI women, with a detection sensitivity of 38%. Antigens CT376 reacted with additional 3 TFI samples while CT557 reacted with another 2. Thus, the tri-antigen panel could detect TFI samples with a sensitivity of 58% while still maintaining 100% specificity. The remaining 2 antigens (CT111 and CT579) failed to react with any additional unique TFI sera (data not shown). It is worth noting that CT443, the outer membrane complex protein B (OmcB), was recognized by TFI women with the highest frequency and intensity (both were significantly higher comparing to FC women). We next tested whether a combination of human serum dilution and CT443 fragmentation could help to further differentiate TFI from FC women. The CT443 full-length (FL) proteins were expressed in 12 different fragments, all of which were used to react with both TFI and FC women sera at different dilutions (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Only the fragments representing the C-terminal portion of CT443, including fragments 9 (F9), 11 (F11), and 12 (F12), were reactive with human sera. At each human serum dilution, the CT443 fragments produced significantly greater differences than the full length CT443 did in antibody reactivity between TFI and FC samples. For example, at 1:1000 dilution of human sera, the full length CT443 reacted with 88% of TFI and 60% of FC women (a 32% decrease in reactivity with FC women antibodies) while F11 with 58% TFI and 24% FC (59% decrease). When the human serum was used at 1:10,000 dilution, neither CT443FL nor F11 reacted with FC sera but both reacted with 38% and 17% of TFI sera respectively. Among the TFI sera recognized by CT443, one was unique and not detected by any of the already identified 3 TF-associated antigens. Thus, a combination of serum sample dilution with the 4 antigens (HSP60, CT376, CT557, and CT443) could differentiate TFI from FC with a sensitivity of 63% (95% CI: 0.41–0.77) while maintaining 100% specificity (95% CI: 0.91–1). Thus, these 4 antigens were designated as TFI antigens. However, these 4 antigens also strongly reacted with STI serum samples even when the sera were highly diluted (Fig. 2, panels e & f). We next reanalyzed proteome array data in order to identify C. trachomatis antigens that could differentiate STI from TFI women. A total of 21 C. trachomatis antigens strongly reacted with STI sera but reacted poorly with either TFI or FC women serum samples (data not shown) and were thus designated as STI or acute infection-associated antigens. When human serum samples were diluted at 1:10,000, 13 of the 21 STI-associated antigens failed to react with any sera from either TFI or FC women but maintained positive reactivity with some STI serum samples (Fig. 3). Notably, antigen CT875 reacted with 14 out of the 24 STI serum samples. CT147 reacted with an additional unique STI sample. A combination of CT875 and CT147 can distinguish women with acute infection from those with tubal factor infertility and normal fertility with a detection sensitivity of 63% (95% CI: 0.41–0.77) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 0.95–1).

Table 2.

Antigens Preferentially Recognized by Women With Tubal Factor Infertility but Not Normal Fertility

| Groups | Tubal Factor Infertility (n=24) | Normal Fertility (n=25) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORFs | Freq. | Mean ± SD | Freq. | Mean ± SD | Fisher’s | Kruskal Wallis |

| HSP 60 (CT110) | 38% | 0.308±0.512 | 0% | 0.018±0.054 | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| CT376 | 25% | 0.137±0.186 | 0% | 0.005±0.037 | 0.003 | 0.08 |

| CT111 | 17% | 0.129±0.238 | 0% | 0.043±0.062 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| CT557 | 17% | 0.142±0.289 | 0% | 0.008±0.047 | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| CT579 | 17% | 0.077±0.163 | 0% | 0.004±0.040 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| CT443 | 88% | 0.717±0.576 | 60% | 0.306±0.258 | 0.04 | 0.31 |

SD, standard deviation.

Six C. trachomatis proteins were statistically significantly recognized by the tubal factor infertility group, but not the fertile control group, in terms of either recognition frequency (Freq; Kruskal Wallis Test) or intensity (optical density values listed as mean±SD or mean ± SD; Fisher’s exact Test).

Fig. 2. Reactivity patterns of antigens preferentially recognized by TFI women with serum samples from STI women.

Antigens HSP60, CT376, CT557, CT443FL (full length), and CT443F11 (fragment 11; X-axis) were reacted with each of the 73 human sera from tubal factor infertility (TFI, panels a & b), fertile control (FC, panels c & d) and sexually transmitted infection (STI, panels e & f) groups (Y-axis). The human sera were used at either 1:1000 (panels a, c and e) or 1:10,000 (b, d and f) dilution. Each horizontal bar indicates a positive reactivity as determined based on the mean plus 2 standard deviations. Unique reactivities between an antigen and a TFI serum are marked with stars. The reactivity frequencies of CT443FL and CT443F11 with TFI (panles a & b) and FC (panel c) sera were marked accordingly. Note that antigens preferentially recognized by TFI sera were also highly reactive with STI sera.

Fig. 3. Reactivity patterns of 13 antigens with STI women samples.

When human sera were diluted at 1:10,000 dilution, 13 antigens (listed at top and bottom of the figure) completely lost reactivity with either TFI or FC women samples but each maintained certain level of reactivity with STI samples (panel A). The patterns of the reactivity of the 13 antigens with 24 STI samples are shown in panel B. Each horizontal bar indicates a positive reactivity. Sera reacting uniquely with CT875 and CT147 are marked with a star. Please note that CT875 and CT147 (highlighted in bold face) detected 15 out of the 24 STI sera with a sensitivity of 63% while maintaining 100% specificity.

Discussion

The overall goal of the current study was to identify C. trachomatis antigens that can be used to differentiate women with tubal factor infertility, normal fertility, and acute infection. The three groups in this study are representative of the reproductive-age female population with different clinical diagnoses and diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. The anti-C. pneumoniae antibody levels increased with increasing age in our study population, consistent with observations made previously in other populations (17, 18). Furthermore, anti-C. trachomatis antibody levels are the highest in the youngest group (STI), in agreement with the consensus that younger patients are more susceptible to C. trachomatis infection (2). However, the overall anti-C. trachomatis antibody titers failed to differentiate TFI from FC or STI groups. Thus, we used a whole genome proteome array to search for C. trachomatis antigens that might allow us to differentiate these groups. We have found that a four antigen panel consisting of HSP60, CT376, CT557 and CT443 in combination with antiserum sample dilution can distinguish TFI from FC with a detection sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 100%. However, this same set of antigens strongly reacted with sera from STI group. We next identified 21 STI-associated antigens, two of which, CT875 and CT147, distinguished STI women from other C. trachomatis-exposed women with a detection sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 100%. Thus, it is possible to use sequential screening of different panels of C. trachomatis antigens to differentiate women with tubal factor infertility, normal fertility, and acute infection. We have also presented evidence that antigen fragmentation and serum dilution can be used to further improve detection sensitivity and specificity.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, these findings can be applied clinically not only in infertility clinics but also in general women’s health care settings for identifying women with tubal factor infertility, acute infection, and prior exposure to C. trachomatis respectively. In an infertility clinic, the antibody detection-based testing may complement or replace the more expensive, invasive approaches such as hysterosalpingogram (HSG) and laparoscopy for diagnosing tubal factor infertility. Panels of C. trachomatis antigens could be developed into a widely available commercial test kit at a price of ~$10 each. The antibody testing kit could also be used as a screening tool in low risk patient populations. Individuals with antibodies to TFI antigens (HSP60, CT376, CT557, & CT443) but not STI antigens (CT875 & CT147) could be referred for HSG or laparoscopy for further confirmation of TFI or considering IVF. Individuals with antibodies reactive with both TFI and STI antigens could be referred for antibiotics treatment after confirmation with a DNA detection-based diagnosis of vaginal swab samples. The antibody detection-based kit may also provide prognosis for individuals with prior exposure to C. trachomatis infection.

Fig. 4. Diagram for proposed patient testing.

Individuals screened positive for antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis (Io) will be subjected to a second screen for antibodies to tubal factor infertility (TFI)-associated antigens (Ags; IIo). Those positive for anti-TFI Ag antibodies will be further screened for antibodies to antigens associated with acute infection or sexually transmitted infection (STI; IIIo). If positive, these are the acutely infected patients. If negative, the patients likely have tubal factor infertility. Shaded boxes indicate C. trachomatis infection.

Identification of biomarkers associated with tubal pathology may not only provide a safer means for diagnosis or prognosis of C. trachomatis infection but may also promote our understanding of the mechanisms of C. trachomatis pathogenesis and development of C. trachomatis vaccines. It is widely believed that HSP60 or host immune responses to HSP60 may play important roles in tubal pathology (25, 26, 27, 28, 29). Whether and how the TFI-associated CT376, CT557, and CT443 may also contribute to tubal pathology is worthy of further investigation.

Finally, we ought to be cautious in interpretation and application of the current findings. The already identified antigen panels still need to be confirmed in larger and more diverse populations; Additionally, more careful titration of additional antigens may further improve detection sensitivity while maintaining high specificity.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by R01AI64537 from NIH (to G. Zhong).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Rogers serves as a paid speaker for Merck and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C; Services USDoHaH, editor. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2008. Atlanta, GA: Nov, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/toc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services CfDCaP, editor. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2008 supplement, Chlamydia Prevalence Monitoring Project Annual Report 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Jan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodgers AK, Wang J, Zhang Y, Holden A, Berryhill B, Budrys NM, et al. Association of tubal factor infertility with elevated antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis caseinolytic protease P. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;203(5):494, e7–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claman P, Honey L, Peeling RW, Jessamine P, Toye B. The presence of serum antibody to the chlamydial heat shock protein (CHSP60) as a diagnostic test for tubal factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 1997 Mar;67(3):501–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)80077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodgers AK, Budrys NM, Gong S, Wang J, Holden A, Schenken RS, et al. Genome-wide identification of Chlamydia trachomatis antigens associated with tubal factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2011 Sep;96(3):715–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Hartog JE, Morre SA, Land JA. Chlamydia trachomatis-associated tubal factor subfertility: Immunogenetic aspects and serological screening. Hum Reprod Update. 2006 Nov-Dec;12(6):719–30. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephens AJ, Aubuchon M, Schust DJ. Antichlamydial antibodies, human fertility, and pregnancy wastage. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:525182. doi: 10.1155/2011/525182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veenemans LM, van der Linden PJ. The value of Chlamydia trachomatis antibody testing in predicting tubal factor infertility. Hum Reprod. 2002 Mar;17(3):695–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeling RW, Kimani J, Plummer F, Maclean I, Cheang M, Bwayo J, et al. Antibody to chlamydial hsp60 predicts an increased risk for chlamydial pelvic inflammatory disease. J Infect Dis. 1997 May;175(5):1153–8. doi: 10.1086/516454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Zhang Y, Lu C, Lei L, Yu P, Zhong G. A Genome-Wide Profiling of the Humoral Immune Response to Chlamydia trachomatis Infection Reveals Vaccine Candidate Antigens Expressed in Humans. J Immunol. 2010 Aug 1;185(3):1670–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma J, Zhong Y, Dong F, Piper JM, Wang G, Zhong G. Profiling of human antibody responses to Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital tract infection using microplates arrayed with 156 chlamydial fusion proteins. Infect Immun. 2006 Mar;74(3):1490–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1490-1499.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene W, Xiao Y, Huang Y, McClarty G, Zhong G. Chlamydia-infected cells continue to undergo mitosis and resist induction of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2004 Jan;72(1):451–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.451-460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong G, Fan P, Ji H, Dong F, Huang Y. Identification of a chlamydial protease-like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J Exp Med. 2001 Apr 16;193(8):935–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene W, Zhong G. Inhibition of host cell cytokinesis by Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect. 2003 Jul;47(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan P, Dong F, Huang Y, Zhong G. Chlamydia pneumoniae secretion of a protease-like activity factor for degrading host cell transcription factors required for [correction of factors is required for] major histocompatibility complex antigen expression. Infect Immun. 2002 Jan;70(1):345–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.345-349.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan T, Lu H, Hu H, Shi L, McClarty GA, Nance DM, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis in chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J Exp Med. 1998 Feb 16;187(4):487–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh WP, Taylor MB, Hughes K, Chew SK, Fong CW, Phoon MC, et al. Seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against Chlamydia pneumoniae in Chinese, Malays and Asian Indians in Singapore. Int J Epidemiol. 2002 Oct;31(5):1001–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, Kundsin RB, Stampfer MJ, Poulin S, Hennekens CH. Prospective study of Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG seropositivity and risks of future myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999 Mar 9;99(9):1161–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Chen D, Zhong Y, Wang S, Zhong G. The chlamydial plasmid-encoded protein pgp3 is secreted into the cytosol of Chlamydia-infected cells. Infect Immun. 2008 Aug;76(8):3415–28. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01377-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Lei L, Lu C, Galaleldeen A, Hart PJ, Zhong G. Characterization of Pgp3, a Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-encoded immunodominant antigen. J Bacteriol. 2010 Sep 17; doi: 10.1128/JB.00847-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi M, Gong S, Lei L, Liu Q, Zhong G. A Chlamydia trachomatis OmcB C-terminal fragment is released into host cell cytoplasm and is immunogenic in humans. Infect Immun. 2011 Mar 21; doi: 10.1128/IAI.00003-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C, Chen D, Sharma J, Cheng W, Zhong Y, Liu K, et al. The hypothetical protein CT813 is localized in the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane and is immunogenic in women urogenitally infected with C. trachomatis. Infect Immun. 2006 Aug;74(8):4826–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00081-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fling SP, Sutherland RA, Steele LN, Hess B, D’Orazio SE, Maisonneuve J, et al. CD8+ T cells recognize an inclusion membrane-associated protein from the vacuolar pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Jan 30;98(3):1160–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hower S, Wolf K, Fields KA. Evidence that CT694 is a novel Chlamydia trachomatis T3S substrate capable of functioning during invasion or early cycle development. Mol Microbiol. 2009 Jun;72(6):1423–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cappello F, Conway de Macario E, Di Felice V, Zummo G, Macario AJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and anti-Hsp60 immunity: the two sides of the coin. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Aug;5(8):e1000552. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domeika M, Domeika K, Paavonen J, Mardh PA, Witkin SS. Humoral immune response to conserved epitopes of Chlamydia trachomatis and human 60-kDa heat-shock protein in women with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Infect Dis. 1998 Mar;177(3):714–9. doi: 10.1086/514218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ausiello CM, Palazzo R, Spensieri F, Fedele G, Lande R, Ciervo A, et al. 60-kDa heat shock protein of Chlamydia pneumoniae is a target of T-cell immune response. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2005 Jul-Dec;19(3–4):136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinnunen A, Paavonen J, Surcel HM. Heat shock protein 60 specific T-cell response in chlamydial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2001 Jul-Aug;54(1–2):76–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bulut Y, Faure E, Thomas L, Karahashi H, Michelsen KS, Equils O, et al. Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 activates macrophages and endothelial cells through Toll-like receptor 4 and MD2 in a MyD88-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 2002 Feb 1;168(3):1435–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bax CJ, Mutsaers JA, Jansen CL, Trimbos JB, Dorr PJ, Oostvogel PM. Comparison of serological assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies in different groups of obstetrical and gynecological patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003 Jan;10(1):174–6. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.1.174-176.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hjelholt A, Christiansen G, Johannesson TG, Ingerslev HJ, Birkelund S. Tubal factor infertility is associated with antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) but not human HSP60. Hum Reprod. 2011 Aug;26(8):2069–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma J, Bosnic AM, Piper JM, Zhong G. Human antibody responses to a Chlamydia-secreted protease factor. Infect Immun. 2004 Dec;72(12):7164–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7164-7171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Chen C, Chen D, Wu Y, Zhong Y, Zhong G. Characterization of fifty putative inclusion membrane proteins encoded in the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. Infect Immun. 2008 Jun;76(6):2746–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00010-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gervassi AL, Grabstein KH, Probst P, Hess B, Alderson MR, Fling SP. Human CD8+ T cells recognize the 60-kDa cysteine-rich outer membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol. 2004 Dec 1;173(11):6905–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]