Abstract

We previously showed that human beta defensin-3 (hBD-3), an epithelial cell derived antimicrobial peptide, mediates chemotaxis and activation of myeloid cells. Here, we provide evidence that hBD-3 induces the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 on primary human monocytes by a mechanism involving autocrine activation of ionotropic P2X7 receptors (P2X7R) by ATP. Incubation of monocytes with hBD-3 resulted in increased expression of both the CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules. Treatment of monocytes with a selective P2X7R antagonist inhibited the ability of hBD-3 to induce expression of CD86 but not CD80. The hBD-3-dependent upregulation of CD86 was also attenuated in monocytes incubated with apyrase, a potent scavenger of extracellular ATP. Finally, direct activation of monocyte P2X7 receptors by exogenous ATP mimicked the ability of hBD-3 to induce CD86 expression. These data suggest that hBD-3 induces monocyte activation by both P2X7-dependent (CD86 upregulation) and P2X7-independent (CD80 upregulation) signaling mechanisms and raise the possibility that activation of P2X7 receptors could play an important role in shaping the inflammatory microenvironment in conditions where hBD-3 is highly expressed, such as psoriasis or oral carcinoma.

Keywords: Leukocytes, Antimicrobial peptides, Cell Activation

INTRODUCTION

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) are molecules released from injured cells that can positively or negatively modulate host immune responses via recognition by innate receptors. There is increasing evidence that DAMPs, such as ATP, uric acid, DNA, and high-mobility group box 1, play critical roles in modulating immune responses and inflammation in cancer, allergy, arthritis, and response to vaccination (1–8) by mechanisms that, in part, involve, chemoattraction and activation of professional antigen-presenting cells. In these studies, we investigate the potential link between antigen-presenting cell activation caused by an antimicrobial peptide, human beta defensin-3 (hBD-3), and the DAMP, ATP.

HBD-3, a cationic antimicrobial protein produced by epithelial cells, can activate myeloid antigen-presenting cells by inducing the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, cytokines and chemokines (9–14). We have demonstrated that hBD-3 activates human monocytes via signaling pathways that are mediated in part by Toll-like receptors 1 and 2 (10). The range of monocyte responses to hBD-3, however, can be distinguished from those induced by the well-characterized TLR1/2 agonist, Pam3CSK44 (15). This suggests that hBD-3 may engage monocyte signaling pathways in addition to TLR1/2. In this regard, we recently reported that concentrations of hBD-3 that induce monocyte activation also cause plasma membrane damage and repair responses (16). It is possible, therefore, that these reversible changes in plasma membrane integrity might amplify or modulate hBD-3-dependent APC activation as a consequence of releasing various DAMPs. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the ability of hBD-3 to activate immune responses in monocytes additionally involves autocrine activation of the ATP-gated ion channel receptor, P2X7R.

ATP is released by damaged or dying cells and modulates immune activation in surrounding tissues (17). Released ATP recruits phagocytic antigen-presenting cells to sites of local tissue damage by engaging G protein-coupled P2Y-purinergic receptor family. At higher extracellular concentrations, ATP additionally triggers gating of P2X7R ion channels, resulting in NLRP3 inflammasome activation and release of the acute phase pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β (18). P2X7R is predominantly expressed by hematopoietic cell types including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells (19). P2X7R channels are stable trimeric complexes of P2X7R protein subunits; the latter contain two membrane-spanning segments, cytosolic amino- and carboxy-terminal tails, and a large cysteine-rich extracellular loop. The binding of extracellular ATP to three ligand-recognition sites formed by the interfaces of the three extracellular loops induces repositioning of the three juxtaposed second transmembrane segments that line the ion-conducting pore of the trimeric channel complex. This rapidly switches gating of the channel pore from the closed to the open state. Open-gated P2X7R function as non-selective cation channels that facilitate rapid efflux of cytosolic K+ and influx of extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ (19). With prolonged ATP binding, the P2X7R trimeric complex transitions to another conformational state characterized by further dilation of the conducting pore to facilitate the flux of larger (up 900 Da) organic molecules; these can include various cytosolic metabolites such as ATP (20). If sustained, this latter conformational state of P2X7R leads to cell death (21).

Our previous analyses of immune modulation by hBD-3 centered on induction of the co-stimulatory molecule, CD86, which was differentially regulated by hBD-3 versus Pam3CSK4 in monocytes (15). We have also shown that CD86 in monocytes is induced by another antimicrobial peptide, LL-37(22). Interestingly, LL-37 activation of monocytes and other cell types has been linked to P2X7R activation (23), lending feasibility to our hypothesis that activation of this ion channel may play an important role in the CD86 induction caused by hBD-3.

To investigate these possibilities, we treated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells with ATP or hBD-3, in the absence or presence of a selective P2X7R antagonist or the ATP scavenger apyrase. Our studies demonstrate that hBD-3 causes CD86 induction in monocytes in part by an indirect mechanism consistent with autocrine P2X7R activation. Moreover, the effects are selective because CD80 induction by hBD-3 is not affected by blocking P2X7R. These experiments also demonstrate for the first time that short-term exposure to high concentrations of ATP alone is sufficient to cause CD86 induction in human monocytes. These findings provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of monocyte activation by hBD-3 as well as biological effects of the ubiquitous DAMP, ATP, on antigen-presenting cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Complete medium (CM) was used for cell culture and consisted of Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1% HEPES (1 mM; BioWhittaker), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (BioWhittaker), and 1% L-Glutamine (2 mM; BioWhittaker). Antibodies used were anti-CD14-Allophycocyanin (APC) Cy7 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), anti-CD80-APC (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and anti-CD86-AlexaFluor700 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The wash buffer used during flow cytometry staining consisted of BBL TTA Hemagglutination Buffer (BD, Sparks, MD), 1% BSA (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma Aldrich). Synthetic hBD-3 was purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Apyrase was bought from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). AZ 10606120 dihydrochloride (AZ) and KN-62 were purchased from (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom).

Isolation of PBMC and monocytes

PMBC were isolated from blood drawn in heparin-coated tubes. Briefly, 20 ml of blood was mixed with RPMI (up to 30 ml total volume) and centrifuged for 25 minutes at 461 × g over 10 ml of Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells in the buffy coat were harvested and washed with RPMI before being re-suspended in CM and the cells counted. RossetteSep Monocyte Enrichment Kits (StemCell Tech) were used to isolate monocytes from whole blood for studies requiring purified monocyte cell culture. Purity was checked by CD14 staining and flow cytometry and determined to range from 78–90%.

HBD-3 treatment

Cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells per well in 500 µl of CM. HBD-3 was added to wells at a concentration of 20 µg/ml (3.9 µM) and then the cells were incubated at 37°C overnight in 5% CO2 incubator. In some experiments, cells were pre-incubated with AZ for 20 min at 37°C before hBD-3 was added. In other experiments, apyrase (2.5 U/ml) or apyrase boiled for 5 min was added to the cells at the same time as hBD-3 and incubated overnight.

PI staining and flow cytometry

After overnight incubation, cells were transferred to Falcon tubes (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) and washed twice in wash buffer. Cells were stained with anti-CD14-allophycocyanin cyanine dye 7, anti-CD86-allophycocyanin, and anti-CD80-AlexaFluor700 for 10 minutes in the dark. Cells were then washed and re-suspended in 400 µl wash buffer along with 10 µl of PI (BD Pharmingen). After an additional 10 minute incubation in the dark, cells were analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FACSDIVA (Version 6.1; BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA) or FlowJo (Version 7.6, Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software.

Analysis of CD86 mRNA expression

Monocytes or PBMC were incubated for 6 h or 18 h with ATP (3 mM). RNA was extracted with TRIZol reagent. Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science; Indianapolis, IN) was used to generate first-strand cDNA from the purified RNA. CD86 and GAPDH transcripts were quantified using a StepOne-Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY) with reactions performed in 25 µl containing RT2 SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (12.5µl), 1:25 dilutions of RT product, and 1 µM PCR primer pair stock that were run in triplicate. Amplification cycle conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 40 cycles of (95°C, 15 sec; 55°C, 30–40 sec; and 72°C, 30 sec.). Expression of CD86 was calculated using the ΔΔCt method using StepOne software v. 2.1 with values normalized to GAPDH expression. RT2SYBR Green ROX qPCR Master mix (PA-012) and predesigned qPCR primers for CD86 and human GAPDH were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

P2X7 Receptor-Dependent YO-PRO Dye Influx

An HEK293 cell line (HEK-hP2X7) stably transfected with human P2X7 receptor cDNA has been previously described (1). HEK-hP2X7 cells or the parental wildtype HEK293 cell line (HEK-wt) were plated on 24-well tissue culture plates (106/ml; 500 µL/well) for attachment and growth in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum. After overnight culture, the growth medium in each well was aspirated and replaced with 500 µL basal salt solution (BSS) containing 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM glucose, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Each well was supplemented with 1 µM YO-PRO dye. Some wells were further supplemented with 10 µM AZ10606120 (P2X7 antagonist). The 24-well plate was equilibrated to 37°C in the BioTek Synergy HT plate reader. Baseline fluorescence (485 nm/540 nm) in each well was measured at 25 sec intervals for 5 min prior to the addition of 1 mM ATP, 20 µg/ml synthetic or recombinant hBD3, or saline vehicle. The fluorescence in each well was measured at 25 sec intervals for an additional 30 min prior to the addition of 1% Triton X-100 to permeabilize all cells.

P2X7 Receptor-Dependent Ca2+ Influx

HEK-hP2X7 or HEK-wt cells were plated and grown on 24-well tissue culture plates as described for the YO-PRO influx experiments. After overnight culture, the growth medium in each well was aspirated and replaced with 500 µL basal salt solution (BSS) supplemented with 1 µM fluo-4 AM ester (premixed with 20mg/ml pluronic F-127 at 1:1 by volume) and 2.5mM probenecid. After incubation at 37°C for 45 min, the fluo-4 loading medium was aspirated, replaced with 500 µL BSS supplemented with 2.5mM probenecid, and the cells were incubated another 15 min to allow intracellular hydrolysis of residual fluo4-AM ester. Some wells were further supplemented with 10 µM AZ10606120 (P2X7 antagonist) and the 24-well plate placed into the BioTek Synergy HT plate reader preheated to 37°C. Baseline fluorescence (485 nm/540 nm) in each well was measured at 25 sec intervals for 5 min. The fluo-4-loaded cells were then stimulated with 1 mM ATP, 20 µg/ml synthetic or recombinant hBD3, or saline vehicle. The fluorescence in each well was measured at 25 sec intervals for an additional 30 min prior to the addition of 1% Triton X-100 to permeabilize all cells for maximum Ca2+-dependent fluorescence and then supplemented with 15mM EGTA and 50mM Tris to determine Ca2+-independent fluorescence.

Statistical Methods

Nonparametric tests were used for statistical analyses. Paired sample tests (Wilcoxon sign rank and sign tests) were used to assess differences in CD80 and CD86 staining comparing monocytes incubated with hBD-3 with monocytes incubated with hBD-3 and AZ. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM).

Human studies

A University Hospitals Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board has reviewed and approved all human subject studies performed.

RESULTS

Induction of CD86 expression on monocytes by hBD-3 is suppressed by P2X7R antagonist

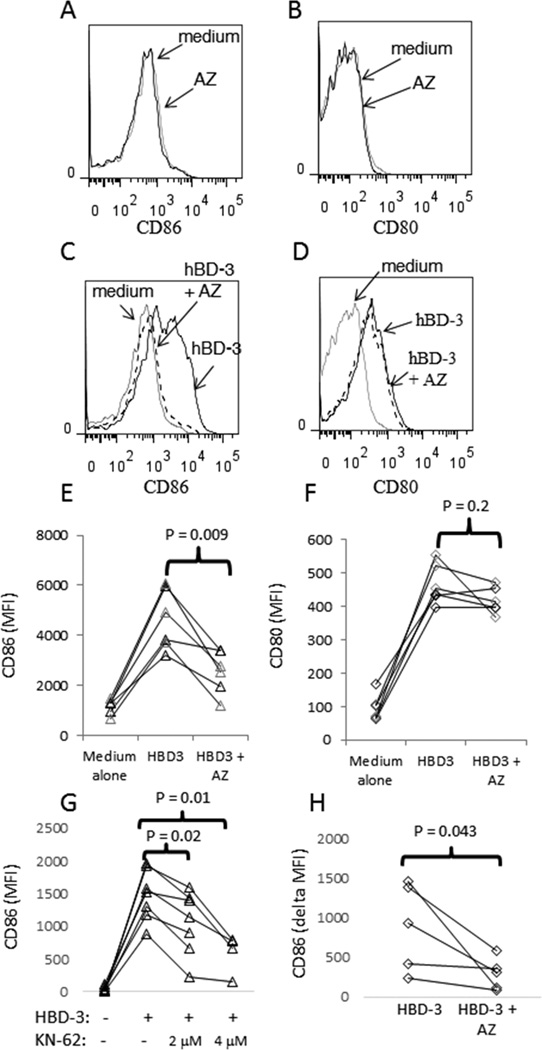

To determine if P2X7R is involved in monocyte activation caused by hBD-3, we tested the effects of the selective P2X7R antagonist, AZ 10606120 dihydrochloride (AZ), on the ability of hBD-3 to induce CD80 and CD86 surface expression. PBMCs were pre-incubated with AZ for 20 minutes prior to the addition of hBD-3. In overnight incubations, we have found no evidence that hBD-3 modifies CD14 surface expression on monocytes in PBMC cell culture (not shown). AZ remained in the culture with hBD-3 for the duration of the subsequent 18 h incubation, after which CD14+ cells were assessed for CD80 and CD86 expression by flow cytometry. Incubation with AZ alone had no effect on the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (Fig 1A and B). When combined with hBD-3, AZ markedly attenuated the capacity of hBD-3 to induce CD86 expression in monocytes (Fig. 1C and E). In contrast, AZ had no effect on the induction of CD80 expression by hBD-3 (Figure 1D and F). Neither LPS nor Pam3CSK4 activation of monocytes was affected by AZ treatment, suggesting that the effects were specific to hBD-3 (data not shown). To confirm the requirement of P2X7R in hBD-3-induced CD86 expression, we also tested the effects of another P2X7R antagonist, KN-62. Similar to AZ, KN-62 inhibited the capacity of hBD-3 to induce CD86 expression in monocytes from PBMC cell cultures (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1. Blocking P2X7 inhibits CD86 induction on monocytes.

PBMC were isolated from whole blood, incubated overnight in medium alone, medium plus hBD-3 (20 µg/ml), medium + AZ (400 nM) or medium + hBD-3 + AZ. Cells were stained with antibodies reactive to CD14, CD80, CD86 and with PI. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cellular debris was gated out via forward scatter-area (FSC-A) vs. side scatter-area (SSC-A), doublets were gated out via FSC-A vs. FSC-H and dead cells were removed as PIbright cells. Analyses of CD86 (A) and CD80 expression (B) are shown for CD14+ cells incubated in AZ compared to cells incubated in medium alone. Assessment of CD86 (C) and CD80 expression (D) is shown for cells incubated in medium alone, medium + hBD-3 or medium plus hBD-3 + AZ. Summary data showing the MFI (y-axis) of CD86 expression (E) or CD80 expression (F) in cells treated as defined (x-axis). Summary data for CD86 induction in PBMC incubated overnight with hBD-3 or hBD-3 + KN-62 are shown (G) as are results from studies using purified monocytes incubated overnight with hBD-3 plus or minus AZ inhibitor (H). Each line in the summary graphs connects respective data points for cells derived from a single donor.

We next assessed the effects of P2X7R inhibition in purified monocytes stimulated with hBD-3. Monocytes were obtained by negative selection and incubated with hBD-3 ± AZ overnight. Similar to our observations in PBMC, the addition of the P2X7R inhibitor to purified monocytes (78–90% purity) resulted in significant inhibition of CD86 induction by hBD-3 (Fig. 1H). This observation provides evidence that the activation of P2X7R by hBD-3 is independent of a non-myeloid cell population.

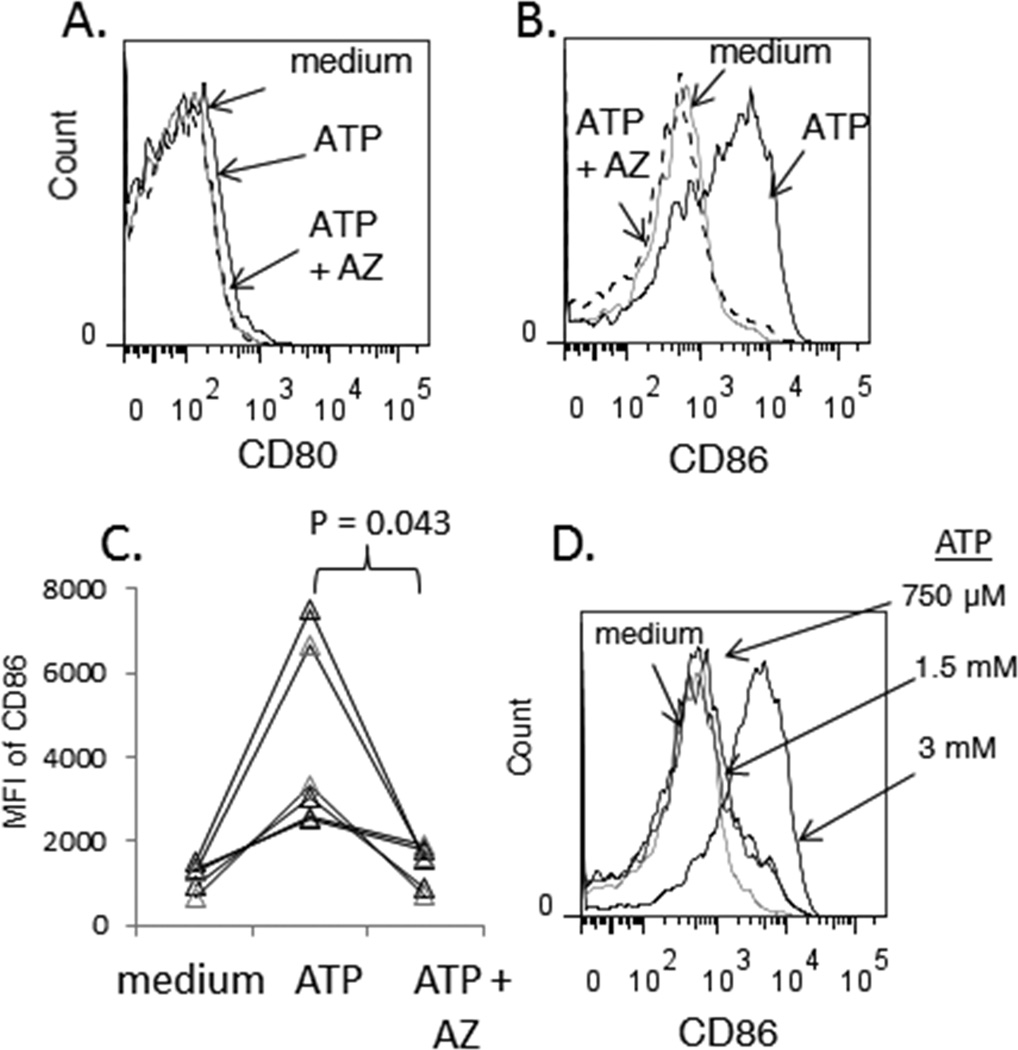

Activation of P2X7R by exogenous ATP is sufficient to induce CD86 expression on monocytes

Due to its low affinity for ATP, P2X7R activation requires millimolar concentrations of exogenously added ATP (24). Incubation of monocytes with ATP (3 mM) markedly induced CD86 expression but had no effect on CD80 expression (Figure 2A–C). The induction of CD86 expression by ATP was blocked in the presence AZ (Figure 2B and C). Lower concentrations of ATP failed to induce CD86 expression (Figure 2D), consistent with millimolar EC50 that characterizes ATP activation P2X7R signaling (24). Notably, monocytes from 40% of our donors exhibited low viability after overnight stimulation with 3 mM ATP, consistent with the ability of sustained P2X7R activation to cause leukocyte death (21). Thus, we limited our analysis of ATP-induced CD86 expression to monocytes from donors whose cells remained viable even during extended exposure to ATP. We also observed that sustained co-stimulation with ATP and hBD-3 induced monocyte death in most donor PBMC samples which prevented evaluation of their phenotype (data not shown).

Figure 2. ATP induces CD86 expression on monocytes by activating P2X7.

PBMCs were isolated from whole blood and incubated overnight in medium alone, medium supplemented with ATP, or medium supplemented with AZ and ATP. Cells were then stained for flow cytometric analysis. Expression of CD80 (A) or CD86 (B) is shown for CD14+ cells in the indicated culture conditions. (C) Summary data from 6 experiments showing MFI of CD86 expression in CD14+ cells incubated overnight in the indicated conditions (x-axis). (D) Dose-dependent induction of CD86 expression by ATP in CD14+ cells after overnight incubation.

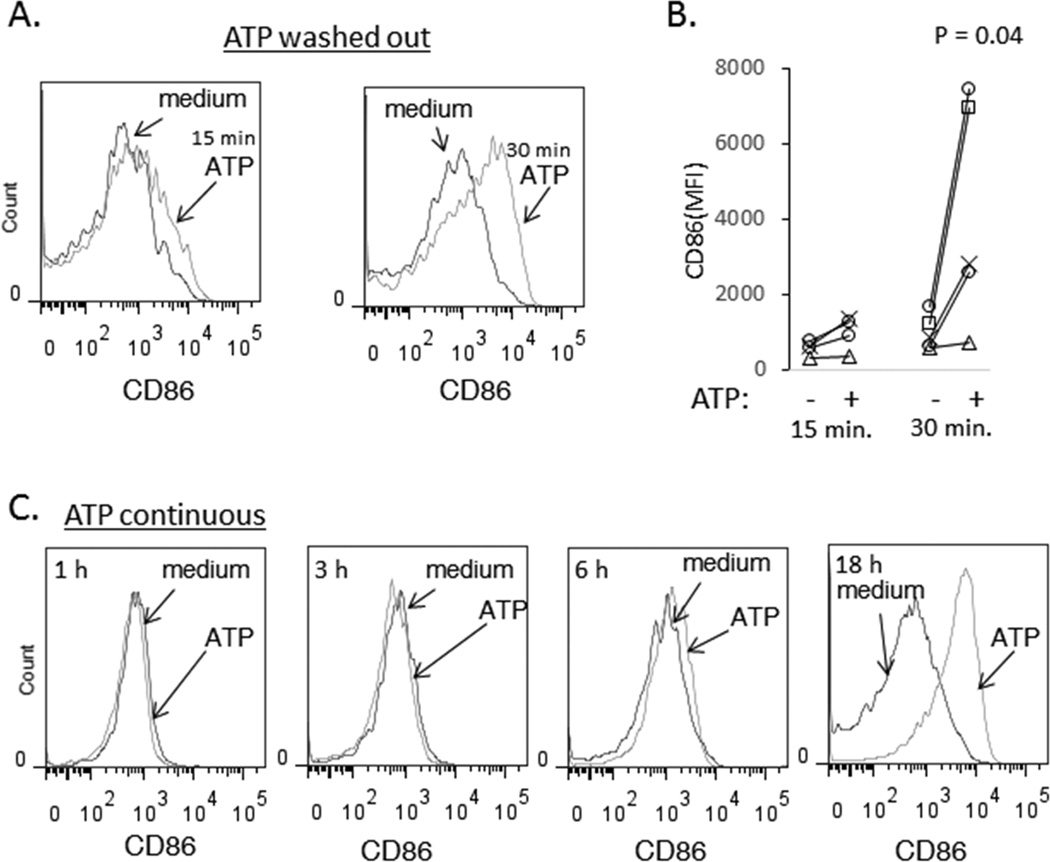

To determine the duration of ATP stimulation required for CD86 induction, PBMC were incubated with 3 mM ATP for 15 or 30 min before the cells were washed and then re-plated in complete medium for overnight (18 h) incubation. ATP stimulus durations of 15–30 min caused induction of CD86 expression in monocytes that was observed after overnight incubation (Figure 3A), suggesting that short-term or acute activation of P2X7R channel function is sufficient to initiate intracellular signaling cascades that result in CD86 expression.

Figure 3. Brief exposure to ATP is sufficient to induce CD86 expression and detection of CD86 induction occurs between 6 and 18 h post ATP stimulation.

(A and B) PBMC were incubated in medium or medium supplemented with 3mM ATP for 15 min or 30 min. Cells were washed and re-plated for an overnight incubation. Histograms show CD86 expression in CD14+ monocytes (A). Results from 5 experiments are shown. (C-D) PBMC were incubated in medium or medium supplemented with 3mM ATP and CD14+ cells were assessed for CD86 expression after 1 h (A), 3 h (B), 6 h (C) or overnight incubations (D). The results are representative of 2 experiments.

To determine the kinetics of CD86 induction in response to P2X7R activation, PBMCs were incubated in the absence or presence of 3 mM ATP for 1, 3, 6, or 18 h prior to sampling and analysis of CD86 cell surface expression in monocytes. Induction of CD86 surface expression was only observed at the 18 h time point (Figure 3C). Although the timing of increased CD86 surface expression after ATP stimulation was consistent with induction of new protein synthesis, studies of CD86 mRNA expression at 6 h and 18 h post stimulation of purified monocytes or PBMC with ATP were inconclusive, demonstrating inconsistent and modest enhancement on CD86 mRNA induction (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that modulation of CD86 expression by ATP occurs via post-transcriptional mechanisms.

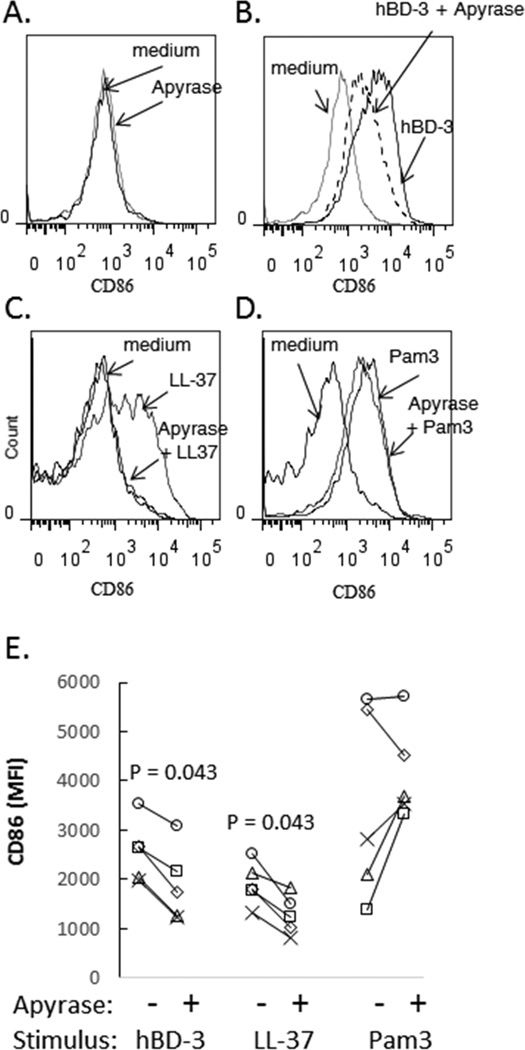

HBD-3 induction of CD86 is attenuated in the presence of apyrase

To determine if hBD-3 directly interacts with P2X7R or acts indirectly to activate P2X7R as a secondary consequence of autocrine ATP release, we incubated cells with recombinant potato apyrase, an enzyme that efficiently hydrolyzes extracellular ATP (and ADP) into AMP. PBMCs were incubated overnight in medium alone, medium + hBD-3, medium + apyrase, or medium + apyrase + hBD-3. LL37, another antimicrobial peptide previously proposed as a direct P2X7R agonist (23), and Pam3CSK4, a TLR1/2 agonist, were used for comparison. In preliminary experiments, we found that high concentrations (≥ 5 U/ml) of the recombinant apyrase alone caused increased expression of CD86 in monocytes, possibly due to activation of TLR’s by residual bacterial endotoxins (data not shown). A lower concentration (2.5 U/ml) of apyrase, however, did not affect baseline CD86 expression during overnight incubation (Fig. 4A) but partially blocked induction of CD86 expression by hBD-3 (Fig. 4B and 4E). This suggests that the ability of hBD-3 to stimulate P2X7R-dependent CD86 expression is mediated, in part, by an indirect mechanism involving autocrine P2X7R activation by local release of ATP into the pericellular microenvironment. LL-37 also induced robust up-regulation of cell surface CD86 which, surprisingly, was prevented in the presence of apyrase (Figure 4C and 4E). These data suggest that LL37 also induces autocrine P2X7R signaling to mediate CD86 expression in monocytes. In contrast to its inhibitory actions on the induction of CD86 by antimicrobial peptides, apyrase did not suppress Pam3CSK4 induction of CD86 expression (Figure 4D and 4E). As a positive control for apyrase activity, we found that apyrase used in these studies blocked ATP-mediated cell death of monocytes (measured by PI staining) during overnight incubations (not shown). An experiment with heat inactivated apyrase demonstrated partial loss of apyrase inhibitory activity. CD86 expression in CD14+ cells incubated in medium, apyrase, hBD-3, hBD-3 + apyrase or hBD-3 + heat-inactivated apyrase equaled 2367, 2271, 11582, 2510 and 6654 mean fluorescent intensity units, respectively. This experiment suggests that a substantial fraction of the inhibitory effects of apyrase are lost with heat inactivation, consistent with an important contribution from enzyme activity.

Figure 4. Apyrase inhibits induction of CD86 expression that is mediated by hBD-3 or LL-37.

(A) PBMC were incubated overnight in medium or medium + recombinant apyrase (2.5 U/ml) and CD86 expression was assessed on the surface of CD14+ cells. (B) PBMC were incubated overnight in medium, medium plus hBD-3 or medium + hBD-3 + apyrase and CD14+ cells were assessed for CD86 expression. (C) Similar studies were carried out to compare CD86 induction in PBMC that were stimulated with LL-37 (20 µg/ml) or (D) Pam3CSK4 (500 ng/ml). (E) Summary data from 5 experiments are shown.

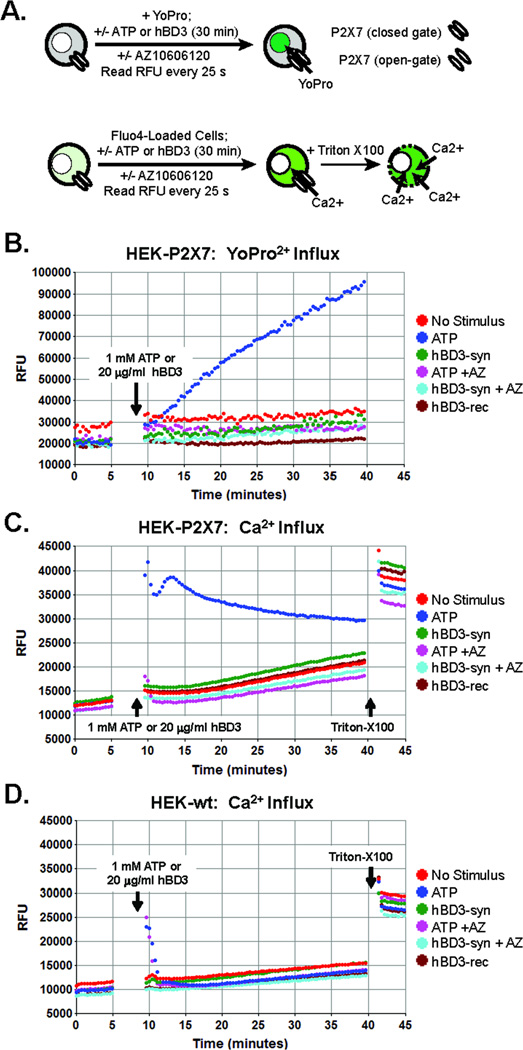

HBD3 does not directly activate human P2X7 receptors

To determine if hBD3 directly interacts with P2X7R, we compared the effects of ATP versus hBD3 (synthetic or recombinant) on P2X7R-dependent channel function in a previously described HEK293 cell line (HEK-P2X7R) stably transfected with human P2X7R cDNA (25). Parallel experiments were performed using wildtype HEK293 cells (HEK-wt) that lack native expression of P2X7R. We assayed induction of the dilated-pore conformation of P2X7R channels that develops with their sustained open-gating by measuring influx of YO-PRO2+, a 375 Da divalent cation and DNA-intercalating dye that is normally membrane-impermeable, but readily conducted by dilated-pore P2X7R channels (20, 27). YO-PRO2+ fluorescence is markedly increased upon binding intracellular nucleic acids (Fig. 5A). In HEK-P2X7R cells, ATP triggered an increase in YO-PRO2+ fluorescence that gradually developed over the 30 min test period and was completely suppressed in the presence of AZ10606120 (Fig. 5B). Control experiments verified that ATP did not stimulate accumulation of YO-PRO2+ in the HEK-wt cells (data not shown). Similarly, no increases in YO-PRO2+ uptake were observed in HEK-P2X7R cells stimulated with either synthetic or recombinant hBD-3 (Fig. 5B). We also assessed P2X7R non-selective cation channel function by measuring Ca2+ influx in HEK-P2X7R (Fig. 5C) or HEK-wt cells (Fig. 5D) loaded with fluo-4 indicator. In HEK-P2X7R cells, ATP immediately triggered a robust increase in Ca2+-dependent fluo4 fluorescence that was sustained for the 30 min test period and completely suppressed in presence of AZ10606120 (Fig. 5C). In HEK-wt cells, ATP elicited only a transient increase in fluo4 fluorescence that decayed to the basal level within 3 min (Fig. 5D); this transient Ca2+ mobilization reflects ATP activation of the G protein-coupled P2Y2 receptors that are natively expressed in HEK293 cells (26). As expected, AZ10606120 did not antagonize this P2Y2R-mediated response. Notably, hBD-3 (synthetic or recombinant) did not trigger increases in Ca2+-dependent fluo4 fluorescence in HEK-P2X7R (or HEK-wt) cells that significantly differed from the slow increases observed in non-stimulated cells. Taken together, these experiments indicate that human P2X7R channels are not directly activated by hBD3 at concentrations which trigger up-regulation of CD86 in monocytes.

Figure 5. hBD-3 does not directly activate P2X7 receptor ion channel function.

(A) Schematic for assays of P2X7 receptor ion channel function by either YoPro2+ dye influx (upper panel) or Ca2+ influx in cells preloaded with fluo-4 Ca2+ indicator dye. Synthetic or recombinant hBD-3 (20 µg/ml) were tested for direct interaction with P2X7 receptors in (B, C) HEK293 cells expressing human P2X7 receptors (HEK-P2X7) or (D) parental wildtype HEK293 cells (HEK-wt). ATP (1 mM) was used as a positive control stimulus for P2X7 activation. Where indicated, HEK-P2X7 or HEK-wt cells were pre-incubated with 10 µM AZ10606120 (AZ) for 10 min prior to stimulation with ATP or hBD-3. In the fluo-4 measurements, the assays were terminated by permeabilization of the cells with 1% triton-X100. (B) Comparative effects of ATP versus hBD-3 on YoPro2+ influx in HEK-P2X7 cells in the absence or presence of AZ. (C) Comparative effects of ATP versus hBD-3 on Ca2+ influx in HEK-P2X7 cells in the absence or presence of AZ. (D) Comparative effects of ATP versus hBD-3 on Ca2+ influx in HEK-wt cells in the absence or presence of AZ. All traces are representative of results from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that hBD-3 induces the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) on the surface of monocytes and that TLR1/2 signaling is involved in this response (10). Here, we provide evidence that activation of P2X7R signaling in response to hBD-3 is also important for the induction of CD86, but not CD80 expression, in these APCs. These data highlight the complexities of monocyte activation by hBD-3. Our new findings suggest that CD86 expression is further amplified by engagement of an autocrine P2X7R-dependent signaling cascade in monocytes exposed to hBD-3. This mechanism does not appear to influence CD80 induction that is also caused by hBD-3 suggesting that CD80 induction may be predominantly dependent on TLR signaling as we have previously reported (10).

The ability of hBD-3 to cause P2X7R activation appeared to involve autocrine ATP release from monocytes because the response was observed in purified cell populations and markedly attenuated by apyrase. ATP can be released from viable cells, i.e., independently of lytic death, via either direct efflux of cytosolic ATP through the plasma membrane or exocytosis of granules/organelles that can accumulate and compartmentalize ATP (28–30). ATP efflux mechanisms can involve regulated gating of host cell plasma membrane channels, insertion of microbial pore-forming proteins, or transient non-selective disruption of plasma membrane lipid bilayer integrity by biophysical (e.g., electroporation) or biochemical (e.g., lipase activity or cholesterol-abstracting molecules) perturbations. Exocytotic mechanisms of ATP release in monocytes and other cells can involve mobilization of secretory lysosomes that contain ATP (31–33). The potential for hBD-3 to cause increased plasma membrane permeability is supported by our recent studies which demonstrated that hBD-3 can cause membrane damage in monocytes as detected by increased propidium iodide (PI) staining and membrane blebbing (16). In response to focal membrane damage, monocytes also initiate membrane repair mechanisms that include fusion of secretory lysosomes with the plasma membrane in order to reconstitute damaged regions. In this process, ATP can be released into the extracellular microenvironment of the cell surface (34). Consistent with this scenario, we demonstrated that cell surface expression of lysosomal membrane marker, LAMP1, is increased in monocytes after overnight incubation with hBD-3(16). Nonetheless, we were unable to unequivocally correlate hBD-3-induced PI staining, as an index of membrane damage, with induction of CD86 expression in the current study. Moreover, although we previously observed that LL-37 did not cause membrane damage and blebbing in monocytes, the ability of this particular anti-microbial peptide to induce CD86 expression was inhibited by apyrase. This suggests that anti-microbial peptides such as hBD-3 and LL-37 may also directly stimulate exocytotic release of ATP stored in secretory lysosomes or other granules/vesicles. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling has been shown to trigger exocytosis of ATP-containing lysosomes in THP-1 monocytes (35). We and others have previously reported that hBD-3 modulate – positively or negatively - the activity of multiple chemokine GPCRs expressed in myeloid and lymphoid leukocytes (36–38).

Interestingly, LL-37 has been shown by other groups to activate P2X7R directly in a manner not affected by apyrase (23, 39, 40). The differences in our results to those previously reported may stem from the different methodologies used in each study. In previous studies, monocytes were positively selected and stimulated with LPS prior to treatment with LL-37. IL-1β processing and release was used in these studies as the outcome. In contrast, we stimulated PBMCs overnight with LL-37 and assayed CD86 up-regulation as the outcome. In addition, the previous studies used 10–20 µM LL-37 compared to the 3.9 µM LL-37 employed in our experiments. It is conceivable that these differences in LL-37 concentrations may have influenced potential interactions with P2X7R. Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility that either LL-37 or hBD-3 can mediate some activity via direct apyrase-independent interactions with P2X7R. As noted previously, we limited the tested concentration of apyrase to a level that did not by itself induce CD86 expression. We were only able to show partial inhibition of hBD3-induced CD86 expression by apyrase under these conditions and, therefore, it remains formally possible that at least some of the activity of these molecules stems from direct antimicrobial peptide/P2X7 interactions. However, neither synthetic nor recombinant hBD3 induced activation of P2X7R channel activity in our functional assays using HEK293 cells expressing human P2X7 receptors (Figure 5). Thus, the inability of apyrase to completely suppress hBD3-induced CD86 expression may reflect limited spatial or kinetic accessibility of the large apyrase protein to cell surface compartments wherein P2X7 receptors are activated by highly localized release of autocrine ATP.

ATP is a well-defined DAMP that is released from damaged and apoptotic cells and acts as a chemotactic agent for phagocytic cells (41). ATP will also enhance the release of IL-1β and IL-18 in monocyte/macrophages that are pre-exposed to LPS. This activity is dependent on ATP signaling through the ligand-gated ion channel P2X7 (42). Here, we show that activation of the P2X7R by ATP in monocytes has important biological activity even in the absence of LPS priming. Exposure of monocytes to ATP appears to result in the induction of CD86 cell surface expression. It is not yet clear if increased surface expression of CD86 is driven by enhanced transcription of CD86 mRNA. Our analyses of CD86 mRNA were inconclusive, with evidence of only modest CD86 mRNA enhancement. Thus, it is possible that ATP regulates CD86 expression via a post-transcriptional mechanism. Interestingly, only a brief exposure (roughly 30 minutes) to high concentrations of ATP is required for induction of CD86 surface expression. Thus, transient periods of ATP exposure, such as might occur in monocytes infiltrating damaged tissue, could lead to modified maturation and function of these cells. Our results suggest that DAMP release, including ATP, from host cells could be a common mechanism by which antimicrobial peptides may affect inflammation. Our observations in human monocytes are also similar to reports of CD86 and CD80 induction in mouse DC exposed to ATP in vitro and in vivo (43). The latter observation was proposed as a possible mechanism contributing to graft-versus-host disease.

The potential to differentially regulate CD80 and CD86 expression on APCs through exposure to DAMPs, antimicrobial peptides, or both could have important implications for APC function. Although both CD86 and CD80 are important co-stimulatory molecules that enhance antigen presentation (44), differences in the accessibility of one versus the other has consequences for adaptive immune function and response (45–47). For example, blockade of CD86 leads to increased Treg function (48) and a Th2 bias (47) in vivo. Thus, differential induction of these molecules by antimicrobial peptides, microbial products and DAMPS could influence adaptive immune responses.

Abbreviations used in this article

- Pam3CSK4

3N-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2RS)-propyl]-[R]-cysteinyl-[S]-seryl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysyl-[S]-lysine x3 HCl

Footnotes

Authorship

A.B.L. and B.M.F. performed experiments for these studies. A.B.L, G.R.D., A.W. and S.F.S. designed experiments and all authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Source of support: This work was supported by NIH grants (P01-DE017337 and R01-GM36387), the NIH funded Center for AIDS Research at Case Western Reserve University (P01-AI-36219) a grant from the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

References

- 1.Foell D, Wittkowski H, Roth J. Mechanisms of disease: a 'DAMP' view of inflammatory arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:382–390. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Ortiz C, Vermaelen K, Panaretakis T, Mignot G, Ullrich E, Perfettini JL, Schlemmer F, Tasdemir E, Uhl M, Genin P, Civas A, Ryffel B, Kanellopoulos J, Tschopp J, Andre F, Lidereau R, McLaughlin NM, Haynes NM, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nature medicine. 2009;15:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goh FG, Midwood KS. Intrinsic danger: activation of Toll-like receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:7–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Takeshita F, Ishii KJ. Recognition of damage-associated molecular patterns related to nucleic acids during inflammation and vaccination. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:168. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisetsky DS. The origin and properties of extracellular DNA: from PAMP to DAMP. Clin Immunol. 2012;144:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rock KL, Kataoka H, Lai JJ. Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Hara M, Yokoi H, Matsumoto K, Saito H, Nagaoka I, Ikeda S, Okumura K, Ogawa H. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensin (hBD)-3 and hBD-4 activate mast cells and increase skin vascular permeability. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:434–444. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funderburg N, Lederman MM, Feng Z, Drage MG, Jadlowsky J, Harding CV, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. Human-defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18631–18635. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0702130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia JR, Jaumann F, Schulz S, Krause A, Rodriguez-Jimenez J, Forssmann U, Adermann K, Kluver E, Vogelmeier C, Becker D, Hedrich R, Forssmann WG, Bals R. Identification of a novel, multifunctional beta-defensin (human beta-defensin 3) with specific antimicrobial activity. Its interaction with plasma membranes of Xenopus oocytes and the induction of macrophage chemoattraction. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s004410100433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nagaoka I, Okumura K, Ogawa H. The human beta-defensins (−1, −2, −3, −4) and cathelicidin LL-37 induce IL-18 secretion through p38 and ERK MAPK activation in primary human keratinocytes. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:1776–1784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nakano N, Ng W, Sayama K, Hashimoto K, Nagaoka I, Okumura K, Ogawa H. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensins stimulate epidermal keratinocyte migration, proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:594–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pazgier M, Hoover DM, Yang D, Lu W, Lubkowski J. Human beta-defensins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1294–1313. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5540-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funderburg NT, Jadlowsky JK, Lederman MM, Feng Z, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. The Toll-like receptor 1/2 agonists Pam(3) CSK(4) and human beta-defensin-3 differentially induce interleukin-10 and nuclear factor-kappaB signalling patterns in human monocytes. Immunology. 2011;134:151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lioi AB, Rodriguez AL, Funderburg NT, Feng Z, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. Membrane damage and repair in primary monocytes exposed to human beta-defensin-3. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2012;92:1083–1091. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0112046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu Y, Franchi L, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:1913–1925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Morelli A, Torboli M, Bolognesi G, Baricordi OR. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg TH, Newman AS, Swanson JA, Silverstein SC. ATP4-permeabilizes the plasma membrane of mouse macrophages to fluorescent dyes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1987;262:8884–8888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qu Y, Dubyak GR. P2X7 receptors regulate multiple types of membrane trafficking responses and non-classical secretion pathways. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrov V, Funderburg N, Weinberg A, Sieg S. Human beta defensin-3 induces chemokines from monocytes and macrophages: Diminished activity in cells from HIV-infected persons. Immunology. 2013 doi: 10.1111/imm.12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elssner A, Duncan M, Gavrilin M, Wewers MD. A novel P2X7 receptor activator, the human cathelicidin-derived peptide LL37, induces IL-1 beta processing and release. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:4987–4994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gudipaty L, Humphreys BD, Buell G, Dubyak GR. Regulation of P2X(7) nucleotide receptor function in human monocytes by extracellular ions and receptor density. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C943–C953. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphreys BD, Virginio C, Surprenant A, Rice J, Dubyak GR. Isoquinolines as antagonists of the P2X7 nucleotide receptor: high selectivity for the human versus rat receptor homologues. Molecular pharmacology. 1998;54:22–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schachter JB, Sromek SM, Nicholas RA, Harden TK. HEK293 human embryonic kidney cells endogenously express the P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cankurtaran-Sayar S, Sayar K, Ugur M. P2X7 receptor activates multiple selective dye-permeation pathways in RAW 264.7 and human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Molecular pharmacology. 2009;76:1323–1332. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.059923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjaelde RG, Arnadottir SS, Overgaard MT, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. Renal epithelial cells can release ATP by vesicular fusion. Front Physiol. 2013;4:238. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imura Y, Morizawa Y, Komatsu R, Shibata K, Shinozaki Y, Kasai H, Moriishi K, Moriyama Y, Koizumi S. Microglia release ATP by exocytosis. Glia. 2013;61:1320–1330. doi: 10.1002/glia.22517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pryazhnikov E, Khiroug L. Sub-micromolar increase in [Ca(2+)](i) triggers delayed exocytosis of ATP in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2008;56:38–49. doi: 10.1002/glia.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dou Y, Wu HJ, Li HQ, Qin S, Wang YE, Li J, Lou HF, Chen Z, Li XM, Luo QM, Duan S. Microglial migration mediated by ATP-induced ATP release from lysosomes. Cell Res. 2012;22:1022–1033. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sivaramakrishnan V, Bidula S, Campwala H, Katikaneni D, Fountain SJ. Constitutive lysosome exocytosis releases ATP and engages P2Y receptors in human monocytes. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4567–4575. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Chen G, Zhou W, Song A, Xu T, Luo Q, Wang W, Gu XS, Duan S. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:945–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wesley UV, Bove PF, Hristova M, McCarthy S, van der Vliet A. Airway epithelial cell migration and wound repair by ATP-mediated activation of dual oxidase 1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:3213–3220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakaki H, Tsukimoto M, Harada H, Moriyama Y, Kojima S. Autocrine regulation of macrophage activation via exocytosis of ATP and activation of P2Y11 receptor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng Z, Dubyak GR, Lederman MM, Weinberg A. Cutting edge: human beta defensin 3--a novel antagonist of the HIV-1 coreceptor CXCR4. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:782–786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin G, Kawsar HI, Hirsch SA, Zeng C, Jia X, Feng Z, Ghosh SK, Zheng QY, Zhou A, McIntyre TM, Weinberg A. An antimicrobial peptide regulates tumor-associated macrophage trafficking via the chemokine receptor CCR2, a model for tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swope VB, Jameson JA, McFarland KL, Supp DM, Miller WE, McGraw DW, Patel MA, Nix MA, Millhauser GL, Babcock GF, Abdel-Malek ZA. Defining MC1R regulation in human melanocytes by its agonist alpha-melanocortin and antagonists agouti signaling protein and beta-defensin 3. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2255–2262. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chotjumlong P, Bolscher JG, Nazmi K, Reutrakul V, Supanchart C, Buranaphatthana W, Krisanaprakornkit S. Involvement of the P2X7 purinergic receptor and c-Jun N-terminal and extracellular signal-regulated kinases in cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 induction by LL-37. J Innate Immun. 2013;5:72–83. doi: 10.1159/000342928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomasinsig L, Pizzirani C, Skerlavaj B, Pellegatti P, Gulinelli S, Tossi A, Di Virgilio F, Zanetti M. The human cathelicidin LL-37 modulates the activities of the P2X7 receptor in a structure-dependent manner. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:30471–30481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802185200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, Lysiak JJ, Harden TK, Leitinger N, Ravichandran KS. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perregaux DG, McNiff P, Laliberte R, Conklyn M, Gabel CA. ATP acts as an agonist to promote stimulus-induced secretion of IL-1 beta and IL-18 in human blood. Journal of immunology. 2000;165:4615–4623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilhelm K, Ganesan J, Muller T, Durr C, Grimm M, Beilhack A, Krempl CD, Sorichter S, Gerlach UV, Juttner E, Zerweck A, Gartner F, Pellegatti P, Di Virgilio F, Ferrari D, Kambham N, Fisch P, Finke J, Idzko M, Zeiser R. Graft-versus-host disease is enhanced by extracellular ATP activating P2X7R. Nature medicine. 2010;16:1434–1438. doi: 10.1038/nm.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA. CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:233–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olsson C, Michaelsson E, Parra E, Pettersson U, Lando PA, Dohlsten M. Biased dependency of CD80 versus CD86 in the induction of transcription factors regulating the human IL-2 promoter. Int Immunol. 1998;10:499–506. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi-qun Z, Joost van Neerven RJ, Kasran A, de Boer M, Ceuppens JL. Differential requirements for co-stimulatory signals from B7 family members by resting versus recently activated memory T cells towards soluble recall antigens. Int Immunol. 1996;8:37–44. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu XY, Zhou YH, Wang MY, Jin LP, Yuan MM, Li DJ. Blockade of CD86 signaling facilitates a Th2 bias at the maternal-fetal interface and expands peripheral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells to rescue abortion-prone fetuses. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:338–345. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng Y, Manzotti CN, Liu M, Burke F, Mead KI, Sansom DM. CD86 and CD80 differentially modulate the suppressive function of human regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:2778–2784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]