Abstract

Genes with relevant roles in the differentiation of closely-related species are likely to have diverged simultaneously with the species and more accurately reproduce the species tree. The Lusitanian (Microtus lusitanicus) and Mediterranean (M. duodecimcostatus) pine voles are two recently separated sister species with fossorial lifestyles whose different ecological, physiological and morphological phenotypes reflect the better adaptation of M. duodecimcostatus to the underground habitat. Here we asked whether the differentiation of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus involved genetic variations within the tumour suppressor p53 gene, given its role in stress-associated responses. We performed a population-genetic analysis through sequencing of exons and introns of p53 in individuals from sympatric and allopatric populations of both the species in the Iberian Peninsula in which a unidirectional introgression of mitochondrial DNA was previously observed. We were able to discriminate the two species to a large extent. We show that M. duodecimcostatus is composed of one genetically unstructured group of populations sharing a P53 protein that carries a mutation in the DNA-binding region not observed in M. lusitanicus, raising the possibility that this mutation may have been central in the evolutionary history of M. duodecimcostatus. Our results provide suggestive evidence for the involvement of a master transcription factor in the separation of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus during Microtus radiation in the Quaternary presumably via a differential adaptive role of the novel p53 in M. duodecimcostatus.

Introduction

Microtus lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus (the Lusitanian and the Mediterranean pine voles, respectively) are western European endemic sister species, with an estimated origin of <150 Kyr (Brunet-Lecomte and Chaline, 1991; Tougard et al., 2008). Both the species exhibit burrowing behaviour but differ in a set of ecological and morphological traits that together suggest that M. duodecimcostatus is more dependent from the subterranean habitat than M. lusitanicus (Mathias, 1990; Santos et al., 2009a, 2009b; Santos et al., 2010). Living underground forces rebreathe of air with low oxygen (hypoxia) and high carbon dioxide tensions (hypercapnia). Respiratory properties and acid–base parameters in the blood of M. duodecimcostatus suggest that this species has developed features to adequately deliver oxygen to tissues under hypoxic-hypercapnic stress (Mathias and Freitas, 1989). Similarly, subterranean species of the genus Spalax (blind mole rat) have evolved physiological and genetic adaptations to efficiently cope with hypoxia (Nevo, 2011). One such genetic variation is located within the tumour suppressor p53 gene (Ashur-Fabian et al., 2004), the most mutated gene in human cancers (Vogelstein et al., 2000). This gene encodes an important transcription factor with constitutive functions in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, apoptosis and metabolism in response to stimuli like hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, genotoxic and oxidative stress (Brady and Attardi, 2010). The p53 mutation found in Spalax—R174K in the human protein—was shown to be sufficient to affect the transcriptional activity of both Spalax and human P53 protein (Ashur-Fabian et al., 2004; Avivi et al., 2007). Other codon variations in P53 were shown to provide adaptive responses to a wide range of environmental cues in other species (Villiard et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2013), strengthening the hypothesis that P53 protein may adapt in structure and function in accordance with ecological stress (Zhao et al., 2013).

Under this assumption and considering the underground dependence of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus, we decided to investigate the presence of genetic variations in the p53 gene in both the species. The two existing population-level studies on the genetic diversity of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus in the Iberian Peninsula have found evidence for a past introgressive hybridization from M. duodecimcustatus to M. lusitanicus of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) gene (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012), and possibly of the nuclear gene IRBP (interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein) given the impossibility to discriminate individuals from the two species when using this marker (Barbosa et al., 2013). Here we performed a population-genetic analysis involving 96 individuals (52 M. lusitanicus and 44 M. duodecimcostatus) sampled in the Iberian Peninsula, and the p53 DNA sequence encoding part of the DNA-binding region of P53, from the 3′ end of exon 5 to the 5′ extreme of exon 7, which includes residue 174. We used specimens captured both in allopatric and sympatric areas where introgressed animals have been observed (Jaarola et al., 2004; Tougard et al., 2008; Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013; Rodriguez-Prieto et al., 2014), to ultimately evaluate whether genes involved in the differentiation of species separated recently carry signature changes reflecting speciation more accurately than neutral genes (Ting et al., 2000). Variability of the obtained p53-coding sequences of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus was further compared with the published sequences from other Microtus species, rodents and mammals.

Materials and methods

Samples

M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus specimens were collected from 21 different sampling sites, throughout the species distribution range in the Iberian Peninsula (Supplementary Table S1). Thirty-one of these individuals had also been studied for cytb sequence diversity in a previous study (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012). Ten samples from M. duodecimcostatus (from sampling sites 21, 22 and 23) came from the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Spain, as well as one sample from M. cabrerae that was used for sequence comparisons within Microtus.

DNA extraction, p53 amplification and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the liver or tail fragments conserved in ethanol using a standard phenol–chloroform protocol. Amplification conditions were as in (DeWoody, 1999), with primer pair p53C and p53D used for amplification and sequencing reactions. PCR products were sequenced on both the strands by Macrogen Inc (Seoul, Korea).

p53 sequence analyses

p53 sequences were aligned using the Clustal W algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994), revised and edited manually in BioEdit 7.2.3 (Hall, 1999). Repeat motifs of polymorphic insertion/deletions (indels) found in intron 6 of p53 were kept clustered. p53 alleles from heterozygous individuals were inferred using PHASE within DnaSP 5.10.01 (Librado and Rozas, 2009). Five replicate PHASE runs were conducted using default values before a final run with 100 burn-in steps and 1000 iterations. The PHASE probability threshold was set to 0.90. Shared sequence types were collapsed into haplotypes using the program DNAcollapser (Villesen, 2007).

Exonic sequences were translated into amino acid (AA) sequences in Mega 5.2.2 (Tamura et al., 2011) using the universal code. Positions of AA were determined using the structured model of human P53. Known sequences of the p53 gene from M. agrestis, M. arvalis, M. oeconomus, M. rossiaemeridionalis and M. ochrogaster were obtained in GenBank (accession numbers listed in Supplementary Table S2), and used for sequence comparisons within Microtus.

Phylogenetic tree and haplotype network construction for p53 and cytb

Phylogenetic relationships among haplotypes were reconstructed by either maximum likelihood in Mega 5.2.2, or using Bayesian inference as implemented in MrBayes 3.2.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012). The program JModelTest 2.1.4 (Darriba et al., 2012) was used to estimate the best DNA substitution model for a set of sequences by performing hierarchical likelihood ratio tests to compare 88 different models and applying the Akaike Information Criterion under default settings. For p53 haplotypes, the TPM2uf model was chosen with uniform rates of variable sites with the following estimated nucleotide frequencies: A=0.1947, C=0.2537, G=0.2938 and T=0.2578; and substitution rate matrix: (AC)=1495.6642, (AG)=8493.0230, (AT)=1495.6642, (CG)=1.0000, (CT)=8492.0230 and (GT)=1.0000. Because a regional partition of cytb haplotypes according to introgression status was observed in M. lusitanicus (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013), we reconstructed the phylogenetic tree of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus using all the cytb sequences available in GenBank and assigned each specimen to its place of origin to investigate any connection between the geographical distribution of p53 and cytb haplotypes. A total of 129 cytb haplotypes were retrieved from all the published sequences of each species, 77 haplotypes from 79 individuals of M. lusitanicus and 52 from 55 specimens of M. duodecimcostatus (accession numbers in Supplementary Table S2; Jaarola et al., 2004; Tougard et al., 2008; Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013). For the construction of the cytb phylogenetic tree the TIM3 substitution model was chosen with a proportion of invariable sites and a gamma-distributed rate variation across sites (TIM3+I+G). The estimated parameters of the model were as follows: substitution rate matrix (AC)=2.1238, (AG)=40.0258, (AT)=1.0000, (CG)=2.1238, (CT)=15.2400 and (GT)=1.0000; gamma shape parameter=0.8630, with 70.9% of invariable sites; and nucleotide frequencies of A=0.3117, C=0.3030, G=0.1307 and T=0.2547. Bayesian inference analysis was performed with two independent runs with four chains (one cold and three hot chains) for one (p53) or ten (cytb) million generations, with a sample frequency of 100. Average s.d. of the split frequencies between the independent runs was checked for convergence on a stationary distribution (Ronquist et al., 2012). The first 25% of the trees were discarded as burn-in and the remaining trees were used to reconstruct a consensus tree and estimate Bayesian posterior probabilities. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed for p53 haplotypes with 10 000 bootstrap replicates. Gene topologies for p53 were inferred using the median-joining network construction approach as computed with Network 4.6.1.2 (Bandelt et al., 1999). Phylogenetic and network analyses were rooted using gene sequences of M. rossiaemeridionalis (= M. levis; GenBank accession number AF014024) or of M. gerbei (GenBank accession numbers in Supplementary Table S2).

Genetic diversity and demographic analyses on p53 sequences

DnaSP 5.10.01 was used to determine nucleotide diversity (π), haplotype number (h) and diversity (Hd), and number of variable sites. Genetic differentiation among the groups of samples of M. lusitanicus and M.duodecimcostatus was assessed by the analysis of molecular variance of the p53 sequences using Arlequin 3.5.1.2 (Excoffier and Lischer, 2010). Signals of departure from neutrality were tested using Tajima's D and Fu's Fs statistics. Statistics based on the mismatch distribution were used to test for demographic expansions under a sudden or a spatial model. Extra repeat motifs found in intron 6 (indel of 10 bp) were removed to allow pairwise comparisons between all the sequences. Statistically significant differences between the observed and the simulated expected mismatch distributions (1000 bootstraps) were evaluated with the sum of the square deviations and Harpending's raggedness index (hg), using Arlequin 3.5.1.2. Frequency distribution graphs were obtained using DNAsp 5.10.01.

Selection tests on p53 exonic sequences under different codon substitution models

Using the Microtus genus phylogenetic tree obtained with exonic nucleotide sequences of the p53 fragment (189 bp), the rate of non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions (ω) of each branch was calculated with PAML 4.7 (Yang, 2007). In addition, each codon of the 63aa P53 fragment was tested for selection pressure by site-specific models. To contrast Microtus p53 diversity with variability within rodents and mammals, we supplemented our data with available nucleotide sequences of this gene region and constructed rodent and mammalian p53-based phylogenies. Unrooted phylogenetic trees using GenBank retrieved p53 exonic sequences covering the 3′ end of exon 5 to the 5′ extreme of exon 7 (189 bp) of Microtus (8 species), rodents (21 species) and mammals (60 species) were obtained with MrBayes 3.2.2 and used as input data in PAML 4.7. Species used in these analyses and respective p53 accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. Bayesian inference analysis was performed as before. JModelTest 2.1.4 selected the TPM2 model as the best substitution model for the Microtus phylogeny (substitution rate matrix: (AC)=1638.9541, (AG)=3746.4665, (AT)=1638.9541, (CG)=1.0000, (CT)=3746.4665 and (GT)=1.0000), the TPM2uf+I+G model for the rodent phylogeny (with gamma shape parameter=2.5410, 52.7% of invariable sites, nucleotide frequencies of A=0.1970, C=0.3098, G=0.2908 and T=0.2024; substitution rate matrix: (AC)=2.7868, (AG)=13.8676, (AT)=2.7868, (CG)=1.0000, (CT)=13.8676 and (GT)=1.0000), and the HKY+I+G model for the mammalian phylogeny (gamma shape parameter=0.8430, with 30.6% of invariable sites; and nucleotide frequencies of A=0.2267, C=0.3287, G=0.2467 and T=0.1979). Statistical tests for selection were done using codon-based maximum likelihood methods implemented in the program ‘codeml' from PAML 4.7. Five comparisons of paired models, M0-model=2, M1–M2, M0–M3, M7–M8 and the branch-site test of positive selection, were used for the likelihood ratio test. The M0-model=2 comparison is suitable to test if the ω ratio (dN/dS ratio) for a particular branch is different from that for all other branches. Likelihood ratio tests of M1–M2 and M7–M8 are useful to examine positive selection acting on codons. The M0–M3 comparison tests the variable pressure among sites. Branch-site test of positive selection compares the modified model A with the corresponding null model with ω2=1 fixed and aims to detect positive selection on sites along the foreground branch. Posterior probabilities for positively selected sites were calculated with Naïve Empirical Bayes for model M3 and Bayes Empirical Bayes for models M2, M8 and model A. Model A was replicated with different starting omega values to ensure convergence of the likelihood. Gaps in the alignment were treated as ambiguity characters in likelihood calculations.

Results

p53 DNA sequence diversity

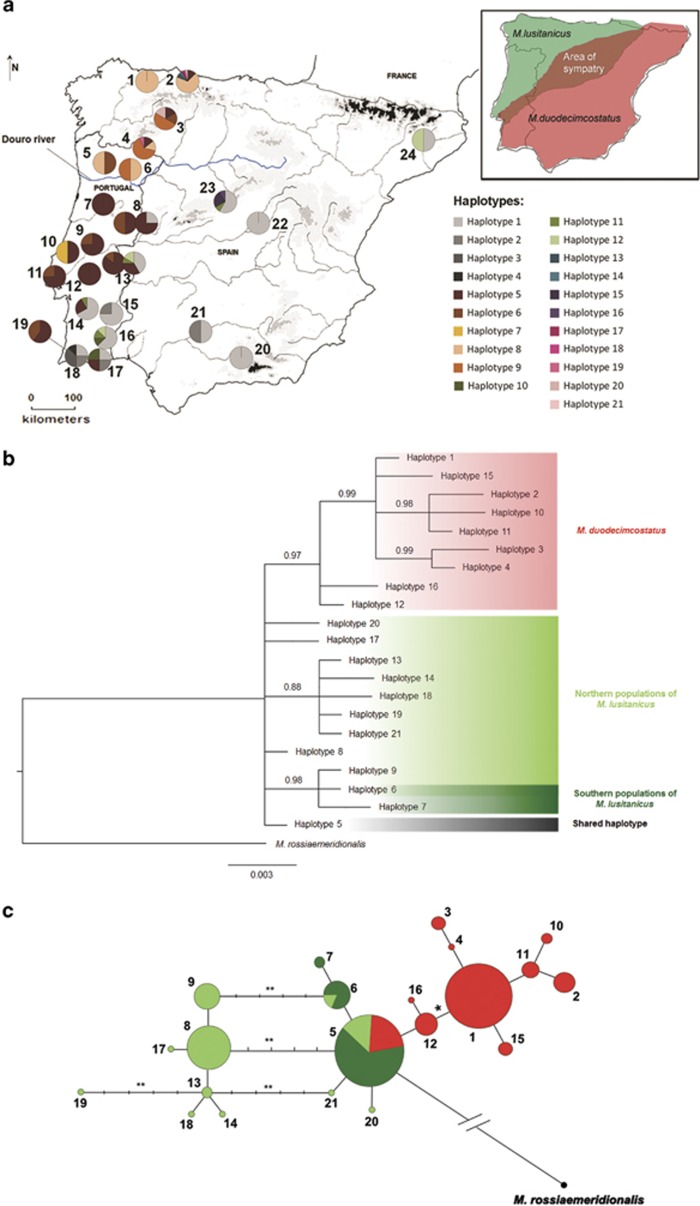

The amplified sequence (697 bp) revealed that a tandem repeat of 20 bp ((GGTTT)3GATTT) within intron 6, common to other Microtus species (DeWoody, 1999), contained one or two extra repeat motifs of 5 bp (GGTTT) in at least one p53 allele in 29 individuals of M. lusitanicus. We found seven single-nucleotide polymorphisms in M. lusitanicus and nine in M. duodecimcostatus (Table 1), of which three and eight, respectively, were parsimony informative. The seven single-nucleotide polymorphisms found in M. lusitanicus were all located in intron 6, whereas in M. duodecimcostatus the variable sites were scattered along the introns and exons of the analysed sequence. A total of 21 haplotypes were found, 12 in M. lusitanicus and 10 in M. duodecimcostatus (Figure 1a, Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1. Sequence diversity values, fixation indices and sources of variation in p53 sequences from M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus.

| Species (region) | Number of sequences |

Sequence diversity |

Fixation indices and source of variation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of segregating sitesa | π±s.d.b | hb | Hd±s.d.b | φST | φCT | φSC | % Among groups | % Within populations | ||

| Microtus lusitanicus | 104 | 7 | 0.0046±0.0027 | 12 | 0.748±0.026 | |||||

| (All populations) | 0.576 | 42.37 | ||||||||

| (Northern group)/(southern group) | 0.697 | 0.670 | 0.080 | 67.04 | 30.32 | |||||

| (Northern group) | 60 | 6 | 0.0034±0.0021 | 11 | 0.697±0.051 | 0.129 | 87.09 | |||

| (Southern group) | 44 | 2 | 0.0007±0.0001 | 3 | 0.403±0.076 | 0.055 | 94.51 | |||

| Microtus duodecimcostatus | 88 | 9 | 0.0017±0.0002 | 10 | 0.629±0.055 | |||||

| (All populations) | 0.190 | 81.04 | ||||||||

indel of 10 bp not included.

π, nucleotide diversity; h, number of haplotypes; Hd,haplotype diversity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of p53 haplotypes in the Iberian Peninsula and respective phylogenetic and network relationships. (a) Map of the Iberian Peninsula showing frequency distributions of p53 haplotypes from M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus according to sampling site (numbered 1 to 24). In sampling sites 8 and 13 the left pie corresponds to M. lusitanicus and the right pie to M. duodecimcostatus. Sampling sites and haplotype labels are as in Supplementary Table S1. Shaded areas of the map denote altitude gradients, with darker areas corresponding to higher altitudes. Douro river is highlighted in blue. Top right corner: distribution range of each species in the Iberian Peninsula (green: M. lusitanicus; red: M. duodecimcostatus; brown: area of sympatry). (b) Phylogenetic relationships among p53 haplotypes, according to the Bayesian inference analysis and with M. rossiaemeridionalis as the outgroup. Numbers above branches represent posterior probabilities. Maximum likelihood inferred the same topology but with lower branch support. Northern and southern populations of M. lusitanicus are located north- and southward of the Douro river, respectively. (c) Median-joining network of the 21 p53 haplotypes found in M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus and the haplotype from M. rossiaemeridionalis. Numbers of circles correspond to the respective haplotypes as in a and b. Colours of circles correspond to species and regional populations as in b. Areas of the circles in the network are proportional to the haplotype frequency. Each bar on the connecting lines separates two mutational events except between haplotype 5 and haplotype from M. rossiaemeridionalis (18 mutational steps). * Mutational event corresponding to a non-synonymous mutation in P53 protein; ** Mutational event corresponding to an additional repeat motif (5 bp) in intron 6.

Phylogenetic and network relationships among p53 haplotypes

The phylogenetic tree of p53 was comprised by one lineage with high posterior probability corresponding to M. duodecimcostatus (Figure 1b). The most common haplotype in M. lusitanicus (haplotype 5) was shared with M. duodecimcostatus (54 and 18% of samples, respectively). Haplotypes 8, 9, 13, 14 and 17 to 21 were exclusive of M. lusitanicus sampled to the north of the Douro river, while M. lusitanicus located southward of this river only carried haplotypes 5–7 (Figures 1a and b). The network displayed three unresolved reticulations because of an indel in intron 6 (one or two extra repeat motifs of 5 bp) (Figure 1c). Ninety-seven percent of M. lusitanicus from the northern region carried this indel, 65% of them in both the alleles. One mutation in intron 5 separated the two main genetic groups, between haplotypes 5 and 12, the latter appearing exclusively in M. duodecimcostatus. The most frequent haplotype in M. duodecimcostatus was haplotype 1 (82% of samples), which connected to haplotype 12 by one mutational step that corresponded to a non-synonymous mutation in exon 7. The root of the network was located along the branch that connects haplotype 5 to M. rossiaemeridionalis haplotype (outgroup), suggesting that haplotype 5 may be the ancestral haplotype between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus.

Geographical distribution of p53 sequence diversity

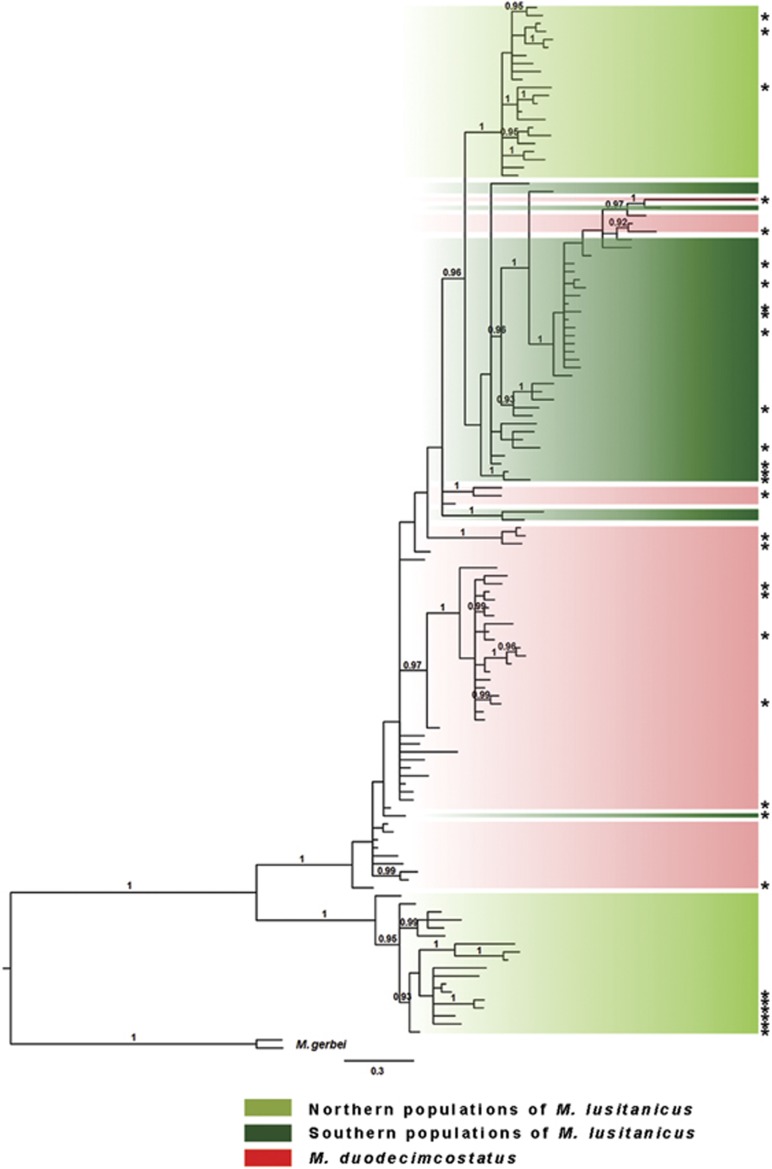

The analysis of molecular variance revealed no genetic structure for M. duodecimcostatus, indicating that the global source of variation is within and not among groups (Table 1). A genetic structuring was found for M. lusitanicus when sampling sites were divided in two regional groups, one comprised by the localities north of the Douro river and another by the localities south of this river, indicating that the overall source of variation is among the regions (67.04%). Overall, the southern group of M. lusitanicus showed lower nucleotide diversity and φST value than M. duodecimcostatus and the northern group of M. lusitanicus (Table 1). The separation in two regional groups of populations for M. lusitanicus is also apparent in the reconstructed cytb phylogenetic gene tree (Figure 2). Two lineages with high posterior probabilities were observed, one that corresponded to M. lusitanicus of the northern regional group and the other to a cluster comprised of M. duodecimcostatus and introgressed individuals of M. lusitanicus (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013). Notably, these introgressed M. lusitanicus were also subdivided with high posterior probability in the two regional groups separated by the Douro river, suggesting that regional separation occurred after secondary contact between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships among cytb haplotypes of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus. Phylogenetic tree was obtained with a Bayesian inference analysis and using M. gerbei as the outgroup. Numbers above branches represent posterior probabilities (only values >0.90 are shown). *Haplotypes corresponding to individuals on which sequencing of the p53 gene was also performed.

Mismatch distribution analyses using p53 sequences suggested past population range expansion (sudden-expansion and spatial-expansion models) for M. duodecimcostatus and the southern group of M. lusitanicus, while for the northern group of M. lusitanicus the observed distributions were significantly different from that expected under a spatial-expansion model according to sum of the square deviation (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S4).

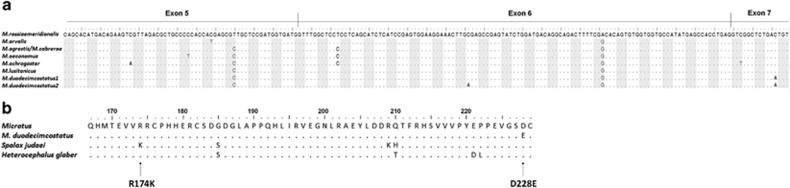

P53 protein diversity

The 697-bp amplified fragment of p53 encodes a region of 63 AAs. We found two types of coded sequences, one in M. duodecimcostatus and one in other Microtus species (Figure 3). The R174K mutation was not present in Microtus. However, M. duodecimcostatus carried a unique non-synonymous mutation at position 694, in exon 7. This mutation was a C–A transversion in the third position of codon 228 (residue number in the human protein), resulting in a conservative AA replacement of an aspartic acid (D) for a glutamic acid (E). It was found in all but four individuals (91% of the total sample) that came from the sympatric area of the distribution range. Two individuals from sampling sites 16 and 17 (allopatry; Figure 1a) carried an additional synonymous mutation at site 186, in exon 6 (C–A transversion in one p53 allele; R202R; M. duodecimcostatus2 in Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Comparison between p53 exonic (exons 5 to 7) and protein sequences of Microtus and two subterranean species. (a) Alignment of p53 exonic sequences found in Microtus. (b) Alignment of P53 protein sequences corresponding to p53 exonic sequences of Microtus, Spalax judaei (accession number CAH03844) and Heterocephalus glaber (accession number EHB04497). Residue numbers are as in human P53 protein (two more residues than in Microtus). Mutations R174K occurring in Spalax and D228E from M. duodecimcostatus are indicated.

Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood of p53-coding sequence

All comparisons of M0 with branch model=2 suggested a significant different ω ratio for the M. duodecimcostatus branch, a result not observed when the M. lusitanicus branch is chosen (Supplementary Table S5). Site-selection tests also suggested a general negative selection acting on p53 codons (M0, ω=0.07, ω=0.07 and ω=0.08 among Microtus, rodents and mammals, respectively), but with significant variation among sites in rodents and mammals (M0–M3, P<0.01), implying that the selective pressure on this region varies among AAs. Model M3 indicated for the mammalian lineages only site 209 with high Naïve Empirical Bayes posterior probability for being positively selected. Branch-site tests of positive selection with M. duodecimcostatus as the foreground branch were not significant in the three sets of lineages analysed, although in all the cases branch-site model A predicted site 228 as potentially being under positive selection in this branch when compared with the background branches (Bayes Empirical Bayes posterior probabilities >0.94). When selecting M. lusitanicus as the foreground branch, branch-site model A returned much lower posterior probabilities that this site is under positive selection in this branch (posterior probabilities <0.32).

Discussion

We did not find the R174K variation of P53 in either M. lusitanicus or M. duodecimcostatus. We were particularly interested in the latter because of its more pronounced underground habits. This mutation, although associated with hypoxic resistance in Spalax, is also not found in other subterranean taxa such as the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber; Figure 3b), and may not be required per se to live in a hypoxic environment. Our most remarkable result, however, was the finding of a D228E mutation within the DNA-binding region of P53 in the majority of M. duodecimcostatus—91% of the total sample– and its absence in the other Microtus species analysed (M. lusitanicus, M. agrestis, M. arvalis, M. oeconomus, M. rossiaemeridionalis, M. cabrerae and M. ochrogaster). This mutation could have appeared de novo in M. duodecimcostatus or existed as standing variation in ancestral populations, in which case we should have found it within M. lusitanicus, even at a low frequency. The absence of this alteration in other Microtus and the high frequency with which it is found in M. duodecimcostatus (68% in homozygosity) strongly suggests that this mutation may have had an important role in the differentiation of this species during the Pleistocene, when arvicolines (voles) in the Iberian Peninsula responded to the new environmental conditions with radiation to many ecological specialist species (Gomez Cano et al., 2013). The largely allopatric distribution range of these two species may well reflect this ecological divergence. In sympatry, both the voles occupy a specialized ecological niche, in which soil characteristics seem to be particularly relevant (Borghi et al., 1994; Santos et al., 2009a, 2009b; Santos et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2011). Niche specialization may involve distinctive physiological and genetic adaptations (Singh et al., 2009; Hadid et al., 2013), probably species and stress environmental specific, as suggested with the S104E variation observed within the P53 protein of high-altitude M. oeconomus or the R174K mutation in P53 of the subterranean Spalax (Ashur-Fabian et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2013). The D228E mutation could similarly have favoured M. duodecimcostatus as this species expanded its territory in the Iberian Peninsula and evolved a more pronounced fossorial behaviour than M. lusitanicus.

Our phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood results are in agreement with analyses on the complete gene sequence that show the presence of mostly purifying sites in the DNA-binding domain of p53 in mammals (Khan et al., 2011). The non-significant results from the tests for positive selection most probably result from the fact that our analysed fragment is short-sized (63 codons) and shows low divergence among sequences, even when sampling is increased to include evolutionary distant mammalian taxa, resulting in low power of the likelihood ratio tests (Yang and Nielsen, 2002). It is worth noting, however, that parameter estimates under branch-site model A suggest the presence of sites under positive selection, namely site 228 for M. duodecimcostatus, with a posterior probability of >94%. The same test also predicts the physiologically important site 174 as being positively selected in the Spalax branch, with a posterior probability of >56% (Supplementary Table S5). Lack of statistical support from the branch-site test of positive selection prevents us from interpreting these results as a conclusive evidence of positive selection acting on these sites (Zhang et al., 2005), but clearly opens up the possibility that 228E may have a role in M. duodecimcostatus physiology, as already demonstrated for site 174K in Spalax, and that this issue should be addressed with functional studies.

As to the p53 genetic structuring of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus in the Iberian Peninsula, we found that M. duodecimcostatus is comprised of one genetically unstructured group of populations that possibly resulted from the range expansion of an ancestral population that carried haplotype 1 of p53. This haplotype harbours the D228E alteration in the protein sequence, which is therefore spread throughout a wide geographical range within this species' distribution. The shared haplotype with M. lusitanicus (haplotype 5) may have already been present in a common ancestral species, persisting in M. duodecimcostatus by incomplete lineage sorting.

We found that M. lusitanicus may be separated in the two regional groups, one located northward and the other located southward of the Douro river, which possibly resulted from a range contraction of M. lusitanicus in the past. Haplotype richness and exclusiveness found in the northern populations of M. lusitanicus may be explained by the past relative isolation from the southern populations, whereas the lower haplotype and nucleotide diversities and φST value found in the latter suggest that these populations suffered a more severe bottleneck followed by a rapid and recent expansion of an ancestral population with increase in effective population size and consequent spread of haplotype 5 south of the Douro river. The majority of the individuals from the northern region carried an extended tandem repeat sequence in intron 6, mostly in homozygosity. These additional repeats appear to have been independently formed on contemporary haplotypes—haplotypes 5, 6 and 21—with which present-day haplotypes unique to the northern region share single-nucleotide polymorphisms (compare Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure S2). Noteworthy, the tandem repeat region is located in close vicinity to the 5′ splice site of intron 6 of p53 and is enriched in thymidines, making it a potential binding site for splicing regulators like TIA1 (Aznarez et al., 2008). The majority of intron 6 polymorphic sites found in M. lusitanicus (5 out of 7) are present in the northern populations, suggesting that this gene region is mutation-prone in particular in these populations. The additional repeats could thus have evolved to prevent skipping of exon 6 in the presence of deleterious splice mutants, or appeared associated with a more mutagenic genomic background and remained in these populations as neutral mutations.

We propose that the secondary contact between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus that resulted in the observed introgression of M. duodecimcostatus mtDNA into M. lusitanicus (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013) presumably occurred before a range contraction of M. lusitanicus, as indicated by the presence of both non-introgressed and introgressed individuals in the northern populations and by the separation of introgressed individuals in the northern and southern populations (Figure 2). Introgression of the p53 gene from M. duodecimcostatus into M. lusitanicus is not apparent from our results because of the absence in M. lusitanicus of the most frequent p53 haplotypes found in M. duodecimcostatus, regardless of the cytb introgression status in M. lusitanicus. We cannot presently exclude the possibility of a generalized low level of nuclear introgression between these the two species due to the scarcity of the available data. Any significance for the non-introgression of p53 needs to be further elucidated. Exclusion of p53 from introgression could result from the incompatibility of the mutated p53 within the M. lusitanicus genomic background.

In conclusion, our results provide suggestive evidence for the involvement of p53 in the differentiation of the sister species M. duodecimcostatus and M. lusitanicus in the Iberian Peninsula, possibly via an adaptive role of the novel P53. Given the number of subcellular networks that involve P53 during stress responses, any alteration in this protein that becomes fixed, can potentially exert a pleiotropic effect by modifying more than one function of P53, and ultimately, through network rewiring and changes in gene expression patterns, organismal phenotype and fitness (Menendez et al., 2007; Li and Johnson, 2010).

Data archiving

Sequence data have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KR052208-KR052239. Additional information on each sampled specimen and p53 haplotypes is available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.bc65p.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Isabel Rey from the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Spain, for providing biological samples and to Margarida A. Duarte for assistance in data analysis. This work was supported by European Funds through COMPETE and by the National Funds through the Portuguese Science Foundation (UID/AMB/50017/2013 project, FCT-PTDC/BIA-BEC/103729/2008 project and FCT-SFRH/BPD/81925/2011 postdoctoral grant to ASQ).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website (http://www.nature.com/hdy)

Supplementary Material

References

- Ashur-Fabian O, Avivi A, Trakhtenbrot L, Adamsky K, Cohen M, Kajakaro G et al. (2004). Evolution of p53 in hypoxia-stressed Spalax mimics human tumor mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12236–12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avivi A, Ashur-Fabian O, Joel A, Trakhtenbrot L, Adamsky K, Goldstein I et al. (2007). P53 in blind subterranean mole rats—loss-of-function versus gain-of-function activities on newly cloned Spalax target genes. Oncogene 26: 2507–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznarez I, Barash Y, Shai O, He D, Zielenski J, Tsui LC et al. (2008). A systematic analysis of intronic sequences downstream of 5' splice sites reveals a widespread role for U-rich motifs and TIA1/TIAL1 proteins in alternative splicing regulation. Genome Res 18: 1247–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A. (1999). Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16: 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa S, Pauperio J, Searle JB, Alves PC. (2013). Genetic identification of Iberian rodent species using both mitochondrial and nuclear loci: application to noninvasive sampling. Mol Ecol Resour 13: 43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos-Silveira C, Santos SM, Monarca R, Mathias Mda L, Heckel G. (2012). Deep mitochondrial introgression and hybridization among ecologically divergent vole species. Mol Ecol 21: 5309–5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi CE, Giannoni SM, Martínez-Rica JP. (1994). Habitat segregation of three sympatric fossorial rodents in the Spanish Pyrenees. Z Saugetierkd 59: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Brady CA, Attardi LD. (2010). p53 at a glance. J Cell Sci 123 (Pt 15): 2527–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet-Lecomte P, Chaline J. (1991). Morphological evolution and phylogenetic relationships of the European ground voles (Arvicolinae, Rodentia). Lethaia 24: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9: 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWoody JA. (1999). Nucleotide variation in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene of voles from Chernobyl, Ukraine. Mutat Res 439: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Lischer HE. (2010). Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 10: 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Cano AR, Cantalapiedra JL, Mesa A, Moreno Bofarull A, Hernandez Fernandez M. (2013). Global climate changes drive ecological specialization of mammal faunas: trends in rodent assemblages from the Iberian Plio-Pleistocene. BMC Evol Biol 13: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadid Y, Tzur S, Pavlicek T, Sumbera R, Skliba J, Lovy M et al. (2013). Possible incipient sympatric ecological speciation in blind mole rats (Spalax). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 2587–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jaarola M, Martinkova N, Gunduz I, Brunhoff C, Zima J, Nadachowski A et al. (2004). Molecular phylogeny of the speciose vole genus Microtus (Arvicolinae, Rodentia) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol 33: 647–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MM, Ryden AM, Chowdhury MS, Hasan MA, Kazi JU. (2011). Maximum likelihood analysis of mammalian p53 indicates the presence of positively selected sites and higher tumorigenic mutations in purifying sites. Gene 483: 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Johnson AD. (2010). Evolution of transcription networks—lessons from yeasts. Curr Biol 20: R746–R753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. (2009). DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25: 1451–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias ML. (1990). Morphology of the incisors and the burrowing activity of Mediterranean and Lusitanian Pine Voles (Mammalia, Rodentia). Mammalia 54: 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Mathias ML, Freitas JP. (1989). Oxygen transport and blood buffering capacity in the Mediterranean Pine Vole. Misc Zool 13: 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez D, Inga A, Jordan JJ, Resnick MA. (2007). Changing the p53 master regulatory network: ELEMENTary, my dear Mr Watson. Oncogene 26: 2191–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo E. (2011). Evolution under environmental stress at macro- and microscales. Genome Biol Evol 3: 1039–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Prieto A, Igea J, Castresana J. (2014). Development of rapidly evolving intron markers to estimate multilocus species trees of rodents. PLoS One 9: e96032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61: 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SM, Mathias MDL, Mira AP. (2010). Local coexistence and niche differences between the Lusitanian and Mediterranean pine voles (Microtus lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus. Ecol Res 25: 1019–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Santos SM, Mathias ML, Mira AP. (2011). The influence of local, landscape and spatial factors on the distribution of the Lusitanian and the Mediterranean pine voles in a Mediterranean landscape. Mamm Biol 76: 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Santos SM, Mira AP, Mathias ML. (2009. a). Factors influencing large-scale distribution of two sister species of pine voles (Microtus lusitanicus and Microtus duodecimcostatus: the importance of spatial autocorrelation. Can J Zoolog 87: 1227–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Santos SM, Mira AP, Mathias ML. (2009. b). Using presence signs to discriminate between similar species. Integr Zool 4: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Cheong N, Narayan G, Sharma T. (2009). Burrow characteristics of the co-existing sibling species Mus booduga and Mus terricolor and the genetic basis of adaptation to hypoxic/hypercapnic stress. BMC Ecol 9: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CT, Tsaur SC, Wu CI. (2000). The phylogeny of closely related species as revealed by the genealogy of a speciation gene, Odysseus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5313–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougard C, Brunet-Lecomte P, Fabre M, Montuire S. (2008). Evolutionary history of two allopatric Terricola species (Arvicolinae, Rodentia) from molecular, morphological, and palaeontological data. Biol J Linn Soc 93: 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Villesen P. (2007). FaBox: an online toolbox for fasta sequences. Mol Ecol Notes 7: 965–968. [Google Scholar]

- Villiard E, Brinkmann H, Moiseeva O, Mallette FA, Ferbeyre G, Roy S. (2007). Urodele p53 tolerates amino acid changes found in p53 variants linked to human cancer. BMC Evol Biol 7: 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. (2000). Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1586–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R. (2002). Codon-substitution models for detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol Biol Evol 19: 908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nielsen R, Yang Z. (2005). Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol 22: 2472–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Ren JL, Wang MY, Zhang ST, Liu Y, Li M et al. (2013). Codon 104 variation of p53 gene provides adaptive apoptotic responses to extreme environments in mammals of the Tibet plateau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20639–20644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.