Abstract

Objectives

To determine the baseline factors predictive of significant radiographic progression (SRP) in patients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) despite receiving methotrexate (MTX).

Methods

Patients from the MTX arm of the Trial of Etanercept and Methotrexate with Radiographic Patient Outcomes (TEMPO) trial with sustained moderate RA (defined as ≥3.2 mean disease activity score in 28 joints ≤5.1 during the last 6 months of the first year) were analysed for SRP (mTSS >3.0 overall) after 2 and 3 years. Baseline predictors for SRP were identified by univariate and multivariate analyses. All variables shown to be significantly associated with SRP were categorised based on clinically relevant cut-offs and tertiles and were included in a matrix risk model.

Results

228 patients were assigned MTX treatment, 210 patients were in the radiographic intention-to-treat population, and 96 of these had sustained moderate RA. SRP occurred in 25 (26%) and 33 (34%) patients after 2 and 3 years of MTX treatment, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analyses found that C reactive protein (CRP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity at baseline were predictive of SRP after 2 and 3 years (p<0.05 for all). The matrix risk model showed that RF positivity and CRP levels >40 mg/L at baseline were significantly associated with SRP after 2 (p<0.05 for both; R2=0.24) and 3 years (p<0.05 for both; R2=0.22). The baseline erosion score was not found to be predictive of SRP.

Conclusions

Patients with sustained moderate RA despite receiving MTX treatment are at risk of SRP, with both RF positivity and high CRP levels shown to be predictive of this.

Keywords: Methotrexate, Rheumatoid Arthritis, DMARDs (synthetic), Treatment

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), moderate to high disease activity can lead to radiographic progression.

Previous studies have investigated baseline variables that may be predictive of radiographic progression, but have largely included patient populations with early and severe RA.

Those with moderate RA represent a substantial proportion of patients in clinical practice; however, this population is heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

What does this study add?

Within patients with moderate RA, we identified that both high C reactive protein levels and rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity at baseline were factors contributing to the risk of significant radiographic progression (SRP), despite methotrexate (MTX) treatment.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The identification of predictors of SRP could facilitate early, aggressive treatment where necessary and avoid unnecessary treatment escalation in patients with moderate activity at low/no risk of SRP.

Introduction

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), high disease activity can lead to radiographic progression, subsequent functional disability and a reduced quality of life.1 2 Recent EULAR guidelines recommend clinical remission (mean disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) of <2.6) or low disease activity (LDA; DAS28 ≤3.2) to be the key targets of RA treatment.3 Patients with RA who do not achieve clinical remission or LDA after 3–6 months are advised to switch or adjust treatment until this target is attained.3–5 Despite these recommendations, many patients in Europe have moderate disease activity (≥3.2 DAS28 ≤5.1) but remain on methotrexate (MTX), the most common first-line treatment, and do not switch to more aggressive treatment strategies.6–10

Previous studies have investigated baseline variables that may be predictive of radiographic progression.11–16 However, these studies have largely included patient populations with early and severe RA and parameters that have been of poor prognostic value. Studies investigating the risk of disease progression in patients with established and stable moderate disease activity are very limited. While it is recognised that moderate disease activity is not an adequate target for patients with RA, in real life, those with moderate RA represent a substantial proportion of patients in clinical practice.8 10 The objective of this study was to identify factors contributing to the risk of significant radiographic progression (SRP) among patients with moderately active RA despite receiving MTX treatment, to help improve treatment to target in this heterogeneous RA population.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This study is a subanalysis of the Trial of Etanercept and Methotrexate with Radiographic Patient Outcomes (TEMPO) trial (NCT00393471), a double-blind, randomised, 3-year multicentre study. In TEMPO, 682 patients were randomly assigned to receive etanercept (ETN) 25 mg twice weekly (n=223), MTX <20 mg/week (n=228), or a combination of both (n=231). At baseline, patients in the MTX arm received MTX 7.5 mg/week. At the week 4 visit, if the patient had an inadequate response (defined as any painful or swollen joints), the patient's oral MTX dose was increased to 15 mg/week. At the week 8 visit, if the patients still had an inadequate response, the oral MTX dose was increased to 20 mg/week. Treatment remained stable over the 3 years. Further details of the TEMPO trial design and results have been reported previously.17–19

For this subanalysis, patient data from the MTX arm of the TEMPO trial with sustained moderate RA (defined as ≥3.2 mean DAS28 ≤5.1) during the last 6 months of the first year were used (weeks 24 and 52 assessments). With these criteria for ‘sustained moderate RA’, patients with moderate disease activity at baseline that could potentially improve in the first year of treatment were excluded. In addition, patients with moderate RA during weeks 24–52 were assumed to have stable disease activity. The patients analysed had received ≥1 dose of MTX and had ≥1 post-baseline evaluation.

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guideline for good clinical practice and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent, which was reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board.

Assessments and statistical analysis

Details of the method of radiographic analysis are explained in detail elsewhere.17 19 Briefly, radiographs were taken of hands, wrists and feet and scored based on the modified Total Sharp Score (mTSS) method (possible range 0–448).20 For this analysis, a linear extrapolation was used in case of discontinuation before the scheduled annual radiographic visits. On the basis of the cut-off value used in previous analyses, SRP was defined as an increase from baseline of mTSS >3.0 measured over 2 and 3 years of MTX treatment.19 21

Univariate analysis

Baseline variables analysed for predictors of SRP were: age (years); gender (male/female); duration of disease (years); corticosteroid use (yes/no); corticosteroid dose; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; mm/h); C reactive protein (CRP; mg/L); swollen joint count; tender joint count; health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) score; erosion score; mTSS; rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity status (yes/no); RF, mg/L. Month 6–12 variables analysed for predictors of SRP were: ESR, mm/h; CRP, mg/L; swollen joint count; tender joint count; HAQ score; RF, mg/L. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed using these variables in order to identify potential predictors of SRP.

The relationship between erosion score and SRP was determined by calculating the numbers (%) of patients with and without SRP based on their baseline erosion score. The φ coefficients were calculated and p values were determined using Fisher's exact test. Spearman's correlation coefficients were used to compare the relationship between the baseline erosion score and the change in mTSS from baseline at 3 years.

Multivariate analysis

Predictor variables with p<0.10 from the univariate analysis were subsequently selected for stepwise multivariate analysis. All variables with a probability p<0.05 were kept in the final logistic regression model. Results from both the univariate and multivariate analyses were presented as OR with 95% CI.

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the final multivariate model to predict radiographic progression. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated as a measure of the model's accuracy. A positive likelihood ratio (LR+) and a negative likelihood ratio (LR−) were calculated.22 The predictive performance of the model was judged according to commonly agreed levels of LR for diagnostic tests: LR+>10 and LR−<0.1 are very strong; LR+=5–10 and LR−=0.1–0.2 are strong; LR+=2–5 and LR−=0.2–0.5 are moderate; LR+=1–2 and LR−=0.5–1.0 are fair; LR+=1 and LR−=1 are null.23

Matrix risk model

A matrix risk model was constructed to show the percentage probability of SRP after 2 and 3 years of MTX treatment using the significant baseline predictors and to identify the subgroups at a higher risk of SRP. These variables were categorised based on clinically relevant cut-offs and tertiles and were included in a logistic regression model. The mean and median changes from baseline in mTSS for each subgroup were calculated.

Results

Study population

In the TEMPO study, 210 of 228 (92%) patients received MTX and had a 2-year and 3-year assessment of the annual progression of the disease based on their mTSS (radiographic intention-to-treat (rITT)). The mean baseline MTX dose in the rITT was 7.36 (±SD 0.68). By week 24 and until week 52, 95% of patients were receiving ≥15 mg of MTX. During the last 6 months of the first year, 96 of these patients had moderate RA and were included in the analysed population reported here. After 2 and 3 years of MTX treatment, SRP occurred in 25 of 96 (26%) and 33 of 96 (34%) patients, respectively. When analysed per year, SRP occurred in 16 of 96 (17%) patients over 2 years and 15 of 96 (16%) patients over 3 years. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of the patients are summarised in table 1. Patients exhibiting SRP after 3 years of MTX treatment generally had lower disease duration, higher CRP and ESR levels, higher erosion and mTSS, and a greater proportion were RF positive than those who did not display SRP.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics in patients with and without SRP after 3 years

| Baseline characteristic | Patients with SRP after 3 years |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=63) | Yes (n=33) | Total (n=96) | |

| Age, years | 55.4 (12.5) | 51.3 (13.4) | 54.0 (12.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 53 (84) | 26 (79) | 79 (82) |

| Disease duration, years | 7.3 (5.8) | 5.8 (4.7) | 6.8 (5.5) |

| Swollen joints | 21.8 (10.6) | 22.4 (9.7) | 22.0 (10.2) |

| Tender joints | 32.4 (13.4) | 33.7 (13.4) | 32.8 (13.3) |

| ESR, mm/h | 35.2 (23.8) | 54.3 (28.5) | 41.8 (26.9) |

| CRP, mg/L | 18.5 (20.8) | 43.2 (35.5) | 26.9 (29.0) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 34 (54) | 28 (85) | 62 (65) |

| HAQ | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) |

| mTSS | 31.1 (53.6) | 40.7 (47.8) | 34.4 (51.7) |

| Erosion score | 13.6 (29.6) | 18.2 (25.4) | 15.2 (28.2) |

| MTX dose, mg/week | – | – | 7.40 (0.62) |

Data presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise stated.

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; mTSS, modified Sharp/van der Heijde; MTX, methotrexate; RF, rheumatoid factor; SRP, significant radiographic progression.

Predictors of SRP

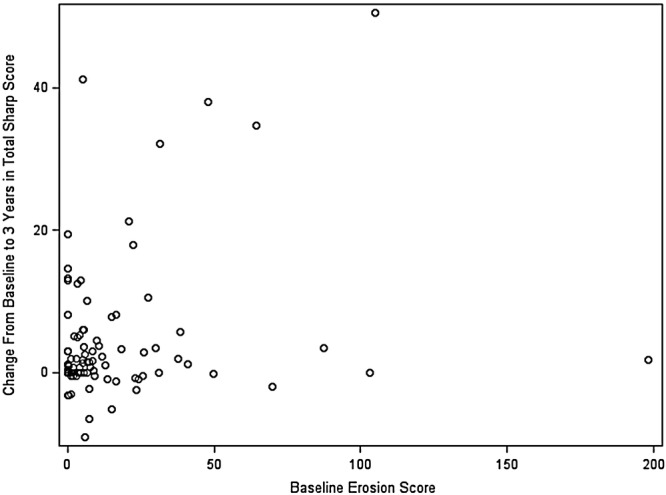

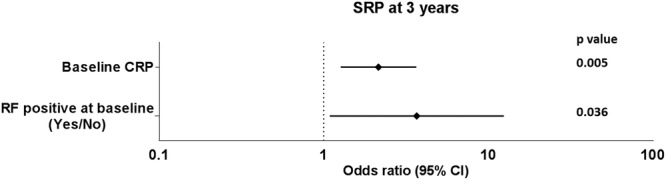

Univariate analysis showed baseline ESR levels, CRP levels, RF levels and RF positivity that were predictive of SRP at 2 (all p<0.05) and 3 years (all p<0.05; table 2). The patient's baseline erosion score was not related to SRP: the Spearman's correlation coefficient showed a very weak relationship between baseline erosion score and change in mTSS after 3 years (0.125; p=0.225; figure 1). In addition, the proportions of patients with baseline erosion scores of 0, >0–<4 and ≥4 showed similar levels of SRP (p=0.118) after 3 years (see online supplementary table S1). Univariate analysis showed month 6–12 ESR, CRP and RF levels that were predictive of SRP at 2 years (all p<0.05), and ESR levels, RF levels, swollen joint count (all p<0.05; table 2) and CRP (p<0.1; table 2) at 3 years. Multivariate analysis confirmed that baseline RF levels were predictive of SRP at 2 years only (p<0.001), while baseline CRP and RF positivity were predictive of SRP after 2 (both p<0.05; R2=0.29) and 3 years (both p<0.05; R2=0.27; figure 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for SRP after 3 years in patients with moderate disease activity despite MTX treatment

| Characteristic | Patients with SRP after 3 years (Yes/No), n=96 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | N | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Age | 96 | 0.72 (0.47 to 1.11) | 0.141 |

| Gender (male/female) | 96 | 1.43 (0.49 to 4.18) | 0.516 |

| Disease duration, years | 96 | 0.74 (0.47 to 1.16) | 0.188 |

| Corticosteroids (Yes/No) | 96 | 0.87 (0.36 to 2.11) | 0.767 |

| Dose of corticosteroids, 0–5 mg/no | 96 | 0.93 (0.32 to 2.71) | 0.982 |

| Dose of corticosteroids, >5 mg/no | 96 | 0.84 (0.31 to 2.26) | 0.760 |

| Swollen joints | 96 | 1.06 (0.69 to 1.61) | 0.800 |

| Tender joints | 96 | 1.10 (0.72 to 1.68) | 0.648 |

| ESR, mm/h | 95 | 2.09 (1.32 to 3.33) | 0.002 |

| CRP, mg/L | 94 | 2.52 (1.51 to 4.20) | <0.001 |

| RF, mg/L | 96 | 2.69 (1.41 to 5.12) | 0.003 |

| RF positive, n (%) | 96 | 4.78 (1.63 to 13.96) | 0.004 |

| HAQ | 96 | 1.22 (0.79 to 1.88) | 0.372 |

| mTSS | 96 | 1.20 (0.79 to 1.81) | 0.391 |

| Erosion score | 96 | 1.17 (0.77 to 1.76) | 0.461 |

| Last observation (months 6–12) | |||

| ESR, mm/h | 95 | 1.69 (1.09 to 2.62) | 0.020 |

| CRP, mg/L | 95 | 1.51 (0.99 to 2.30) | 0.057 |

| RF, mg/L | 96 | 2.09 (1.03 to 4.23) | 0.040 |

| Swollen joints | 96 | 1.58 (1.00 to 2.49) | 0.048 |

| Tender joints | 96 | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.80) | 0.411 |

| HAQ | 96 | 0.93 (0.61 to 1.42) | 0.737 |

| MTX dose, mg/week | 96 | 1.23 (0.77 to 1.96) | 0.387 |

| MTX dose 7.5–10 mg/week or 5–20 mg/week | 96 | 0.95 (0.17 to 5.49) | 0.956 |

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; mTSS, modified Sharp/van der Heijde; MTX, methotrexate; RF, rheumatoid factor; SRP, significant radiographic progression.

Figure 1.

Change from baseline to 3 years in mTSS versus baseline erosion score. Spearman's correlation coefficient= 0.125 (p=0.225) (mTSS, modified Sharp/van der Heijde).

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis for SRP after 3 years in patients with moderate disease activity despite MTX treatment. Baseline CRP in mg/L. N=94 excluding 2 patients with missing CRP value (SRP, significant radiographic progression; MTX, methotrexate; CRP, C reactive protein; RF, rheumatoid factor).

Model validation

On the basis of the ROC analysis, the accuracy of the model was assessed and the AUC, which was found to be equal to 0.78 and 0.77 at 2 and 3 years, respectively, indicated a fair test of prediction. For the baseline predictors of SRP after 2 years, LR+ was 2.48 (95% CI 1.58 to 3.89) and the LR− was 0.41 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.78). At 3 years, LR+ and LR− were calculated at 3.23 (95% CI 1.82 to 5.74) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.74), respectively. All of these data are indicative of a moderate predictive performance of the model.

Matrix risk model

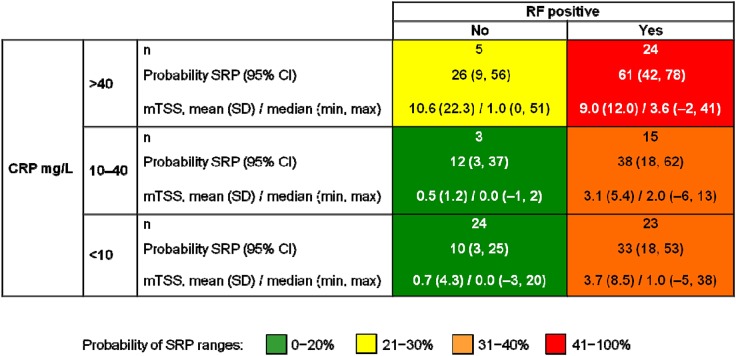

Although categorising the variables decreased the explained variance (Nagelkerke's R2), the final model with all variables categorised showed that RF positivity and CRP >40 mg/L were significantly associated with SRP at 2 (p<0.05 for both; R2=0.24) and 3 years (p<0.05 for both; R2=0.22; online supplementary figure S1). The matrix risk model showed both RF positivity and CRP >40 mg/L to be the most predictive of SRP at 2 (51%; 95% CI 32 to 69) and 3 years (61%; 95% CI 42 to 78; figure 3). The median (minimum, maximum) change from baseline in mTSS was 3.6 (−2, 41) in patients from the subgroup at a higher risk of SRP (CRP >40 mg/L and RF positive; n=24) compared with 0.0 (−3, 20) in patients from the lowest risk subgroup (CRP <10 and RF negative; n=24).

Figure 3.

Matrix risk model showing the probability of SRP in patients with moderate disease activity after 3 years of MTX treatment. Higher percentage indicates more severe radiographic progression (SRP, significant radiographic progression; MTX, methotrexate; CRP, C reactive protein; RF, rheumatoid factor).

Discussion

The results of this study highlight that patients with established moderate RA despite receiving MTX treatment are at risk of radiographic progression, specifically when objective signs of inflammation (CRP) or RF is present. In this patient population, high CRP levels and RF positivity at baseline were strongly predictive of SRP. When observing patients all together, those who had a CRP >40 mg/L and were RF positive had greater radiographic progression than those in the lowest risk groups. This confirms the heterogeneity of the moderate activity RA population and emphasises the value of biological biomarkers to identify patients with a higher risk of structural damage progression. In the original TEMPO study, patients were treated with ETN, MTX or a combination of ETN and MTX. ETN monotherapy and ETN plus MTX resulted in significantly less radiographic progression than MTX alone. Therefore, patients with higher CRP and RF positivity could achieve better results if they switched to more aggressive therapy sooner rather than continuing on MTX alone.

We selected patients with moderate disease activity because they constitute the majority of patients with RA in the clinic, despite EULAR guidelines recommending that patients switch to more aggressive treatment strategies when LDA/remission is not achieved.4 5 For this analysis, patients within the moderate disease activity range at baseline were excluded as they had the potential to improve in the first year of treatment, and we assumed that patients with moderate RA during weeks 24–52 of TEMPO had stable disease activity. This assumption is further supported by the observation that at the end of the 3-year controlled phase of TEMPO, the mean DAS28 was within the moderate range (DAS28=3.9).24

This is the first study to examine predictors of radiographic progression in patients with established moderate disease activity. A study by Visser et al12 in severe early RA also found higher CRP levels to be predictive of radiographic progression, as well as autoantibodies and erosion score.25 We found no relationship between the baseline erosion score and SRP, although the sample size may not have been sufficient to show a correlation. Another study performed by Vastesaeger et al13 in patients with severe early-onset RA on MTX monotherapy also found that higher CRP and ESR levels were associated with rapid radiographic progression. Conversely, a study of pooled data from a number of clinical trials showed that it was clinical measures (as measured by swollen joint counts) rather than inflammation markers (as measured by CRP levels) that were predictive of radiographic progression in patients receiving MTX monotherapy.14 It must be noted that in all of these studies discussed, rapid radiographic progression was measured as mTSS change from a baseline of ≥5, whereas we used >3. The mean change in mTSS in TEMPO over 3 years was −0.14 (95% CI −1.07 to 0.78) for combination therapy, 1.61 (95% CI 0.41 to 2.81) for ETN monotherapy, and 5.95 (95% CI 2.96 to 8.94) for MTX monotherapy, respectively.18 Therefore, we found that 3 units, rather than 5 units, was an acceptable cut-off point with which to define SRP.

The study had a number of limitations. This was a post hoc analysis, and therefore our patient population was limited to those within the TEMPO study. The sample size of n=96 was small and the mean dose of MTX at a baseline of 7.5 mg/week was low, which makes it difficult to generalise the results. However, by week 24, the majority of patients were receiving optimal doses (≥15 mg) of MTX. Overall, we observed a limited level of radiographic progression which may have restricted our ability to determine SRP; however, this is representative of a standard patient population with RA in the 21st century. Our study focused only on the patients receiving MTX monotherapy, mainly because it is these patients who would potentially be most at risk. Further work should investigate the predictive factors associated with disease progression in patients on ETN monotherapy, versus ETN plus MTX combination therapy, in order to give a full picture of those susceptible to SRP. Another limitation to note is that RF autoantibody status is often measured alongside the anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) autoantibody, as both are associated with poor outcomes in patients with RA, including radiographic progression.26 27 Comparison of ACPA status with the RF status would have been informative, but unfortunately ACPA data were not available for analysis. Although we found CRP levels at baseline to be predictive of SRP, they are often dynamic and may have decreased throughout the study, even though the disease activity remained moderate. Since SRP is evaluated after 2 and 3 years, it would have been useful to determine if the CRP levels at later time points were still predictive of radiographic progression. That CRP and RF status are predictors of poor response to MTX and not of disease progression is also impossible to rule out. However, since CRP has been shown to correlate with progression in patients with active disease,28 we provide evidence for the first time that this is also likely in patients with moderately active RA. Other established markers of progression, such as high erosion score, were not found to be predictors of SRP in our study. This is probably because the majority of patients in the TEMPO study had severe early RA and already had erosive disease.

In summary, patients with moderate activity RA receiving MTX treatment may exhibit radiographic progression. In particular, those patients having both high CRP levels and RF positivity at baseline were at higher risk of radiographic progression after 2 and 3 years of MTX treatment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer in October 2009. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Kim Brown of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer.

Competing interests: BF has received consultant fees from Pfizer, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Roche, Sobi and UCB, and grants/research support from Pfizer and MSD. GG and YB are employees of Pfizer. HWN is a former employee of Pfizer.

Ethics approval: The protocol received independent ethics committee (IEC) approval before initiation of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guideline for good clinical practice and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Scott DL, Pugner K, Kaarela K et al. The links between joint damage and disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:122–32. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.2.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsing PM, van Gestel AM, Swinkels HL et al. The relationship between disease activity, joint destruction, and functional capacity over the course of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2009–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.123919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:964–75. 10.1136/ard.2009.126532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aga AB, Lie E, Uhlig T et al. Time trends in disease activity, response and remission rates in rheumatoid arthritis during the past decade: results from the NOR-DMARD study 2000–2010. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:381–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fautrel B, Flipo RM, Saraux A. Eligibility of rheumatoid arthritis patients for anti-TNF-alpha therapy according to the 2005 recommendations of the French and British Societies for Rheumatology. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1698–703. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyrich KL, Deighton C, Watson KD et al. Benefit of anti-TNF therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with moderate disease activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1323–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iannone F, Gremese E, Gallo G et al. High rate of disease remission in moderate rheumatoid arthritis on etanercept therapy: data from GISEA, the Italian biologics register. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:31–7. 10.1007/s10067-013-2348-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokka T, Pincus T. Most patients receiving routine care for rheumatoid arthritis in 2001 did not meet inclusion criteria for most recent clinical trials or American College of Rheumatology criteria for remission. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1138–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saevarsdottir S, Wedren S, Seddighzadeh M et al. Patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who smoke are less likely to respond to treatment with methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: observations from the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Swedish Rheumatology Register cohorts. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:26–36. 10.1002/art.27758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visser K, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK et al. A matrix risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving different dynamic treatment strategies: post hoc analyses from the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1333–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.121160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vastesaeger N, Xu S, Aletaha D et al. A pilot risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1114–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid arthritis near remission: clinical rather than laboratory inflammation is associated with radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1975–80. 10.1136/ard.2011.153734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao KP, Weinblatt ME, Cui J et al. Clinical predictors of erosion-free status in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1473–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emery P, McInnes IB, van Vollenhoven R et al. Clinical identification and treatment of a rapidly progressing disease state in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:392–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewe R et al. Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3928–39. 10.1002/art.23141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Rodriguez-Valverde V et al. Comparison of etanercept and methotrexate, alone and combined, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: two-year clinical and radiographic results from the TEMPO study, a double-blind, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1063–74. 10.1002/art.21655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol 1999;26:743–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Takeuchi T et al. Recovery of clinical but not radiographic outcomes by the delayed addition of adalimumab to methotrexate-treated Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 52-week results of the HOPEFUL-1 trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:904–13. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:763–70. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90128-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1994;271:703–7. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510330081039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijde D, Burmester G, Melo-Gomes J et al. The safety and efficacy of adding etanercept to methotrexate or methotrexate to etanercept in moderately active rheumatoid arthritis patients previously treated with monotherapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:182–8. 10.1136/ard.2007.076166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90. 10.1002/art.21405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Rycke L, Peene I, Hoffman IE et al. Rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: diagnostic value, associations with radiological progression rate, and extra-articular manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1587–93. 10.1136/ard.2003.017574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronnelid J, Wick MC, Lampa J et al. Longitudinal analysis of citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies (anti-CP) during 5 year follow up in early rheumatoid arthritis: anti-CP status predicts worse disease activity and greater radiological progression. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1744–9. 10.1136/ard.2004.033571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plant MJ, Williams AL, O'Sullivan MM et al. Relationship between time-integrated C-reactive protein levels and radiologic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1473–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.