Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of the combined treatment of refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remain uncertain.

Aims

Conduct systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature in English and Chinese about ECT in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia.

Methods

English and Chinese databases were searched for studies published prior to May 20, 2015 regarding the efficacy and safety of the combined treatment of refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications and ECT. Two researchers selected and evaluated studies independently using pre-defined criteria. Review Manager 5.3 software was used for data analysis.

Results

A total of 22 randomized control studies, 18 of which were conducted in mainland China, were included in the analysis. Meta-analysis of data from 18 of the 22 studies with a pooled sample of 1394 individuals found that compared to treatment with antipsychotic medications alone, combined treatment with antipsychotic medications and ECT had significantly higher rates of achieving study-specific criteria of ‘clinical improvement’ (RR=1.25, 95%CI=1.14-1.37). Based on the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria, the quality of evidence for this assessment of efficacy was ‘moderate’. However, the proportion of participants who experienced headache during the treatment was significantly higher in the combined treatment group (RR=9.10, 95%CI=3.97-20.86, based on a pooled sample of 517 from 8 studies) and the proportion who experienced memory impairment was also higher in the combined treatment group (RR=6.48, 95%CI=3.54-11.87, based on a pooled sample of 577 from 7 studies). The quality of evidence about these adverse events was rated as ‘very low’.

Conclusions

There are very few high quality randomized controlled clinical trials about the combination of antipsychotic medications and ECT in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. This meta-analysis found that the combination of antipsychotic medications and ECT could improve psychiatric symptoms in patients with refractory schizophrenia, but the incomplete methodological information provided for most of the studies, publication bias (favoring studies with better outcomes in the combined treatment group), and the low quality of evidence about adverse outcomes, cognitive impairment, and overall functioning raise questions about the validity of the results.

Keywords: electroconvulsive therapy, antipsychotic medication, refractory schizophreinia, systematic review, meta-analysis

Abstract

背景

抗精神病药物合并电抽搐治疗 (electroconvulsive therapy, ECT)对难治性精神分裂症患者的疗效和安全性还不确定。

目的

对电抽搐治疗在难治性精神分裂症中的应用的相关中英文文献进行系统综述和 meta 分析。

方法

在中英文数据库中检索2015年5月20日前发表的关于抗精神病药物合并ECT治疗难治性精神分裂症疗效和安全性的研究。由两名研究人员根据预先设定的标准独立筛选和评估文献。采用Review Manager 5.1软件进行数据分析。

结果

共纳入 22 项随机对照研究,其中在中国大陆开展的研究有 18 项。本研究对 22 项研究中的18项研究共 1394 例样本进行 meta 分析后发现,相比于单独使用抗精神病药物,抗精神病药物合并 ECT 治疗达到各研究特定的“ 临床改善” 标准的比例要显著高 (RR=1.31, 95%CI=1.22-1.41)。根据推荐 GRADE 分级的评估、制定和评价标准 (Grades of Recommendaton, Assessment, Development, and evaluation, GRADE),该疗效评估的证据质量是“中等”。但是,在治疗过程中出现头痛的参与者比例在合并治疗组中显著更高(RR=9.10, 95%CI=3.97-20.86,基于 8 项研究 517 例样本)。合并治疗组中出现记忆受损的患者的比例也高(RR=6.48,95% CI=3.54-11.87,基于 7 项研究 577 例样本)。这些不良反应的证据质量被评定为“非常低”

结论

有关抗精神病药物合并ECT治疗难治性精神分裂症的高质量随机对照临床试验很少。该meta分析发现,抗精神病药物合并ECT可以改善难治性精神分裂症患者的精神症状,但大多数研究提供的方法学信息不全,存在发表偏倚(更偏向于合并治疗组结果相对好的研究),有关不良反应、认知受损和整体功能的证据质量较低,这使我们需要对结果的效度有所质疑。

中文全文

本文全文中文版从2015年10月26日起在htp://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215093可供免费阅览下载

1. Introduction

About 20-30% of patients with schizophrenia are classified as ‘refractory schizophrenia’.[1] The original diagnostic criteria for refractory schizophrenia proposed by Kane in 1995[2,3] were as follows: 1) partially nonresponsive over the past 5 years when treated with three kinds of antipsychotic medications (at least two of which were of different chemical structures) which were administered at appropriate dosages for a sufficient duration; 2) intolerance of side effects of the antipsychotic medications; and 3) relapse or symptomatic deterioration even when taking sufficient doses of appropriate medication. Other widely accepted criteria of refractory schizophrenia include a duration of illness of more than five years; psychiatric symptoms that show no improvement after two-years of regular, full dose and full course treatment with two kinds of antipsychotics; and no response to clozapine.[2]

The difficulty of treating patients with refractory schizophrenia can lead to a poor quality of life for affected individuals.[3] Clozapine is considered an effective medicine for most patients with refractory schizophrenia, but another therapeutic option considered in several studies is the combined use of antipsychotic medication and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[1] However, the findings from these studies have been inconsistent: compared to continued use of standard antipsychotic medications,some studies find the combined use of antipsychotic medication and ECT beneficial,some find it no different,and some find it inferior due to the increased occurrence of memory loss and headache.[4] This paper reports on the first known systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic, combining studies reported both in English and in Chinese.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We searched the following databases for studies published before May 1, 2015: Pubmed, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), The Cochrane Library, EBSCO, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chongqing VIP database for Chinese Technical Periodicals, WANFANG DATA, Chinese Biological Medical Literature Database, Taiwan Electronic Periodical Services, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We used the keywords ‘refractory’, ‘schizophrenia’, ‘psychosis’, ‘electric shock’, ‘electroconvulsive’, ‘clinical control study’, ‘randomly, placebo’,and ‘randomly, trial’ (and the Chinese equivalents) in the searches. Various combinations of these keywords were used to search for articles, reference lists of included articles were hand-checked for further relevant studies, and experts in the field were asked about ongoing studies.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All reports of randomized controlled trails (RCTs) about the combined treatment of refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications and ECT were screened using the following inclusion criteria: a) a diagnosis of refractory (or ‘treatment-resistant’) schizophrenia made by psychiatrists; b) the control group was treated with antipsychotic medications; and c) the intervention group was treated with antipsychotic medication and ECT. Studies published in either English or Chinese were considered. Observational studies, anthropologic studies, review articles, research protocols, case reports, and duplicated reports were excluded.

2.3. Screening of articles

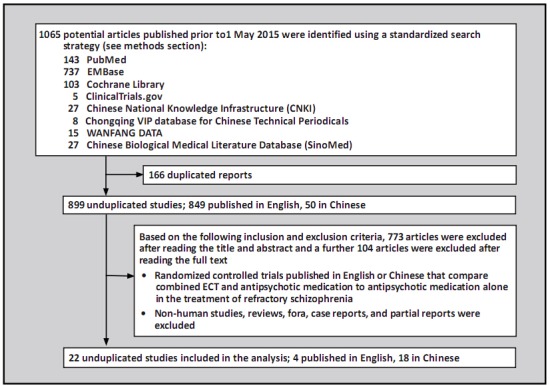

All search results were imported into Endnote X5 software. Two authors (WWZ and PCC) independently screened titles and abstracts after eliminating duplicates. The full texts of the remaining articles were screened according to the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. When the two authors disagreed about the inclusion of an article and were unable to agree after discussing the article, a third author (LCB) made the final determination. As shown in Figure 1, 22 studies were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1. Identification of included studies.

2.4. Evaluation of risk of bias

Two authors (WWZ and PCC) assessed the risk of bias independently for all included articles using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB)[5] tool which considers seven specific items: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and treating clinicians about group assignment; blinding of evaluators of outcomes about group assignment; incomplete data (attrition and exclusions); selective outcome reporting; and other biases (including study-specific biases or concerns about fraudulent results). Each aspect was rated as ‘low risk of bias’, ‘high risk of bias’, or ‘unclear’ (if insufficient information was provided in the article to make a determination). A third author’s (LCB) opinion was sought when the two raters disagreed.

We also evaluated the quality and level of evidence of each outcome variable for each of the 22 included studies using the Cochrane collaboration’s Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) software. This software assesses limitations of the design, consistency of results, indirect evidence, precision of results, publication bias, and effect size for each outcome.[5,6] The overall level of evidence is rated as ‘high’, ‘medium’, ‘low’, or ‘very low’.

2.5. Outcome measures

This meta-analysis was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of the combination of antipsychotic medication and ECT in the treatment of patients with refractory schizophrenia. The primary outcome measure of effectiveness was the reduction in the total score of the main scale used to assess psychiatric symptoms during treatment. The primary outcome measure of adverse events was based on the score of the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS). Secondary outcomes were the changes of cognitive and overall functioning after treatment.

2.6. Data extraction

For each included study, two authors (WWZ and PCC) independently extracted data using a pre-designed data extraction form including the names of authors, publication year, sample size, number of outcome events, age of participants, and types of antipsychotics used. Discrepancies between the two coders were checked by a third author (LCB).

2.7. Analysis

Based on the results of a previous study about risk of bias,[25] the overall risk of bias for each of the 22 studies was classified as ‘low’ if the ratings were ‘low’ for all seven items on the ROB tool, ‘unclear’ if any item is rated as ‘unclear’ and all other items are rated as ‘low’, and ‘high’ if any of the items are rated as ‘high’. The kappa statistic was used to measure the inter-rater agreement between the two independent raters for the ratings of each item and for the overall rating.[7] Review Manager (RevMan 5.3) was used to estimate pooled the mean difference (MD) when the same continuous measure was used as the outcome measure in all included studies, the standard mean difference (SMD) when different continuous measures were used as outcome measures in included studies,and risk ratios (RR) for outcomes that were categorical measures. Heterogeneity was measured using I2.[8] When I2 is less than 50% and p>0.10, the results were considered homogeneous and the fixed-effect model was used; when I2 is greater than 50% but less than 75%, results were considered heterogeneous and the random-effect model was used. If I2 is 75% or greater, we conducted sensitivity analysis to identify potential contributors to heterogeneity; if I2 remained 75% or greater after removing outliers, we only provided descriptive results without pooling estimates. A funnel plot was used to evaluate potential publication bias.[5]

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

As shown in Figure 1, we identified a total of 1065 articles in the selected databases. After removing 166 duplicated articles using Endnote X5 software, there were 899 unduplicated reports. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 773 articles were excluded by reading the title and abstract and a further 104 were excluded by reading the full text. The remaining 22 articles[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] were included in the subsequent analyses: 18 (81.8%) were from China [10,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,22,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and 4 (18.2%) from other countries; [9,11,17,23] all were published between 1999 and 2015.

The characteristics of these 22 included studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

a) Definition of refractory schizophrenia: The inclusion and exclusion criteria varied across studies, but most studies used either the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia established by the Chinese Society of Psychiatry (CCMD)[33] or the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia developed by the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV),[34] required a duration of illness of at least 2 years (with one exception[9]), and required unsatisfactory clinical results when previously using at least two types of antipsychotic medications.

b) Gender of participants: One study[32] only included females, but all other studies[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31] included both males and females.

c) Age of participants: Three studies[9,17,27] did not describe the age of participants; the remaining 19 studies[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,26,28,29,30,31,32] were conducted with adults ranging from 18 to 74 years of age.

d) Duration of illness: Among the 17 studies that provided the mean duration of illness among participants,[9,11,12,13,15,17,18,19,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] the range in the mean duration of illness was from 6 to 21 years.

e) Type of antipsychotic medication used in study: All participants received antipsychotic medications either alone or in combination with ECT. The medications employed included clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone,quetiapine, ziprasidone, chlorpromazine,and flupenthixol.

f) ECT sessions: Two studies[9,17] did not provide information on the number of ECT sessions; the remaining studies[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] reported using 6 to 24 ECT sessions. Among the 18 studies[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,18,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] that provided information on ECT frequency, the range in frequency was from three sessions per week to two sessions per month. Only eight studies[11,12,13,17,22,23,28,31] reported on the type of ECT stimulus,which was either bilateral or bitemporal.

g) Outcome measures: Standard measures of psychiatric symptoms,primarily the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)[35] and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),[36] were used to assess effectiveness,though the criteria used to determine clinical improvement varied somewhat across studies. Overall adverse events were assessed using TESS[37] in six studies.[10,13,18,20,28,30] Five studies reported results of cognitive functioning: two studies[11,23] used the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),[41] one study[18] used the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST),[42] and two studies[19,31] used the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS).[43] Overall functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)[38] in three studies[11,18,28] and the Clinical Global Impression score (CGI) [44] in one study.[17]

h) Duration of follow-up: One study[26] did not provide information about the duration of follow-up; one study[14] had a 3 to 5 week follow-up; four studies[17,21,27,31] followed patients for 4 weeks; nine studies[9,10,15,19,20,22,23,30,32] followed patients for 8 weeks; six studies[12,13,16,18,28,29] followed patients for 12 weeks; and one study[11] followed patients for 24 weeks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 22 randomized controlled trials that compare treatment of refractory schizophrenia with combined ECT and antipsychotic medication versus treatment with antipsychotic medication alone

| study |

treatment ECT group/control group |

age ECT group/control group |

sample size ECT group/control group |

trial duration (weeks) |

number of ECT sessions | blind evaluation | outcome measures (change required for ‘improvement’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chanpatana 1999[11] | ECT+flupenthixol/flupenthixol | 20-49 | 17/18 | 24 | 14 | yes | BPRS; GAF; MMSE |

| Goswami 2003[17] | ECT+chlorpromazine/sham ECT+chlorpromazine | NA | 15/10 | 4 | NA | yes | BPRS(20%) and CGI≤3 or BPRS≤35 |

| Yang 2005[27] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | NA | 30/30 | 4 | 6-12 | NA | PANSS(20%) |

| Ding 2007[13] | ECT+risperidone/risperidone | 36.5/38.7 | 30/30 | 12 | ≥12 | NA | PANSS(20%); TESS |

| Cai 2008[10] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | 18-60 | 50/50 | 8 | 6-12 | NA | BPRS(25%); TESS |

| Braga 2009[9] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | NA | 21/17 | 8 | NA | NA | BPRS(20%) |

| Jiang 2009[18] | ECT+risperidone/risperidone | 38.3/39.7 | 34/35 | 12 | 8-12 | NA | PANSS(50%); TESS; WCST; GAF |

| Zhou 2009[31] | ECT+olanzepine/olanzepine | 43.1/42.2 | 31 /32 | 4 | 8-12 | NA | PANSS(25%); WMS |

| liu 2010a[21] | ETC+various antipsychotics/various antipsychotics | 38.4/39.4 | 37/33 | 4 | 12 | NA | SANS(50%); SAPS(50%) |

| Liu 2010b[22] | ECT+risperidone/clozapine | 28.6/29.6 | 30/30 | 8 | ≥12 | NA | PANSS(25%) |

| Ding 2011[14] | ETC+various antipsychotics/various antipsychotics | 29.8/31.5 | 100/100 | 3-5 | 9-15 | NA | PANSS(50%) |

| Du 2011[15] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | 38.6 | 30/30 | 8 | 10 | NA | BPRS (25%) |

| Duo 2003[16] | ECT+olanzepine/olanzepine | 43.8/42.7 | 30/30 | 12 | 8-12 | NA | PANSS (25%) |

| Jiang 2011[19] | ECT+various antipsychotics/various antipsychotics | 43.4 | 23/23 | 8 | 17-24 | NA | PANSS (50%); WMS |

| Yang 2011[28] | ECT+risperidone/risperidone | 18-65 | 35/36 | 12 | 12 | NA | PANSS (25%); GAF; TESS |

| Chen 2012[29] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | 31.9/33.6 | 36/35 | 12 | 7-12 | NA | PANSS (25%) |

| Wang 2012[32] | ECT+quetapine/quetapine | 28.9/29.3 | 31/31 | 8 | 10 | NA | PANSS (25%) |

| Zhang 2012[30] | ECT+olanzepine/olanzepine | 38.4 | 42/42 | 8 | 16 | NA | PANSS (25%); TESS |

| Chen 2013[12] | ECT+various antipsychotics/various antipsychotics | 18-60 | 50/40 | 12 | 8-12 | NA | PANSS (25%) |

| Jiang 2013[20] | ECT+ziprasidone/ziprasidone+clozapine | 21-74 | 81/81 | 8 | 12 | NA | BPRS (25%); TESS |

| Wang 2013[26] | ECT+olanzepine/olanzepine | 45.5 | 36/36 | NA | 10-12 | NA | PANSS (25%) |

| Petrides 2015[23] | ECT+clozapine/clozapine | 18-60 | 20/19 | 8 | 20 | yes | BPRS (40%); MMSE |

ECT, electroconvulsive therapy

NA, data not available

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale[36]

GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning[38]

MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Exam[41]

PANSS,Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale[35]

CGI, Clinical Global Impression[44]

TESS, Treatment Emergent Symptoms Scale[37]

WCST,Wisconsin Card Sort Test[42]

WMS, Weschler Memory Scale[43]

SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms[40]

SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms[39]

a only had female participants

Table 2.

Supplemental information for the 22 studies included in the systematic review

| study | definition of ‘treatment refractory schizophrenia’ |

mean (sd) years of illness ECT group /control group |

type of ECT stimulus | ECT frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diagnostic frequency criteria | number of failed drug trials | chlorpromazine equivalent dose (mg/d) | duration of illness | severity of illness | ||||

| Chanpatana1999[11] | NA | ≥2 | >750 | ≥2 years | BPRS>35 | 13.7 (5.5)/14.2 (6.4) | bilateral | 2-4/month |

| Goswami 2003[17] | DSM-IV | ≥3 | >1000 | ≥5 years | NA | 7.6/6.9 | bitemporal | NA |

| Yang 2005[27] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS>60 | 6.3 (4.3)/6.0 (4.9) | NA | 3/week |

| Ding 2007[13] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | >450 | ≥5 years | PANSS>65 | 9.7 (11.0)/9.7 (10.4) | bitemporal | 1-2/week |

| Cai 2008[10] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | >600 | NA | BPRS>50 | 1-10a | NA | 3/week |

| Braga 2009[9] | NA | NA | >250 | ≥8 weeks | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jiang 2009[18] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS≥60 | 12.6 (5.1)/12.4 (5.0) | NA | 2-3/week |

| Zhou 2009[31] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | >600 | ≥5 years | PANSS≥60 | 21.0 (7.8)/19.4 (9.9) | bitemporal | 2-3/week |

| Liu 2010a[21] | CCMD-3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3/week |

| Liu 2010b[22] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS≥60 | 8.3 (4.2)/8.0 (3.2) | bitemporal | 1-3/week |

| Ding 2011[14] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3/week |

| Du 2011[15] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | >1000 | ≥5 years | BPRS≥45 | 10.0 (4.0) | NA | NA |

| Duo 2011[16] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17.5 (5.6)/18.6 (4.2) | NA | 2-3/week |

| Jiang 2011[19] | CCMD-3 | ≥2 | NA | ≥2 years | PANSS≥60 | 7.5 (7.6) | NA | NA |

| Yang 2011[28] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS≥60, | 11.2 (5.2)/10.3 (4.9) | bitemporal | 2-3/week |

| Chen 2012[29] | CCMD-3 | ≥2 | >600 | ≥5 years | PANSS>60 | 16.1 (11.6)/15.8 (11.2) | NA | 2-3/week |

| Wang 2012[32] | CCMD-3 | ≥2 | >600 | ≥5 years | PANSS≥60 | 8.7 | NA | 3/week |

| Zhang 2012[30] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS>60 | NA | NA | 1-3/week |

| Chen 2013[12] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | PANSS>60 | 9.0 (1.7)/8.5 (0.9) | bitemporal | 2-3/week |

| Jiang 2013[20] | CCMD-2-R | ≥3 | NA | NA | NA | 7.9 | NA | 1-3/week |

| Wang 2013[26] | CCMD-3 | ≥3 | NA | ≥5 years | NA | 13.2 (5.2) | NA | 3/week |

| Petrides 2015[23] | DSM-IV | ≥2 | >600 | ≥2 years | BPRS; CGIb | NA | bilateral | 2-3/week |

ECT, electroconvulsive therapy

NA, data not available

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale[36]

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale[35]

CGI, Clinical Global Impression[44]

DSM-IV, 4th edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for mental disorders[34]

CCMD-3, 3rd edition of Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders[33]

CCMD-2-R, Revised 2nd edition of Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders[33]

a range (not mean) in duration of illness

b one of the four psychotic items of BPRS≥4 or total score≥12; and CGI≥4

3.2. Risk of bias and publication bias

The results of the assessment of risk of bias in the 22 studies are shown in Table 3. Most of the studies, particularly those from China,did not provide sufficient details about the methods used in the study,so the majority of the assessments for the seven items included in the Risk of Bias (ROB) tool[5] were rated as ‘uncertain’. One study[17] used sham ECT and, thus, was double-blind; two other studies[11,23] used blinded outcome evaluators; and one study[23] reported that the participants and treating clinicians were not blinded; but none of the other studies provided information about blinding of the participant, the treating clinician, or the outcome evaluator. Only two studies[17,18] described the method of randomization. Overall, one study[23] was rated as ‘high’ risk of bias and the other studies were all rated as ‘uncertain’ risk of bias; none of the studies were classified as being at low-risk of bias. The inter-rater reliability of the two independent coders’ assessment of overall risk of bias in the studies was acceptable (kappa=0.75).

Table 3.

Evaluation of risk of bias in the 22 included studies based on the seven items in the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool

| study | random sequence generation | allocation concealment | blinding of participants and providers | blinding of outcome assessment | incomplete outcome data | selective reporting | other biasesa | overall risk of biasb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chanpatana 1999[11] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Goswami 2003[17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Yang 2005[27] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Ding 2007[13] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Cai 2008[10] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Braga 2009[9] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Jiang 2009[18] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Zhou 2009[31] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Liu 2010a[21] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Liu 2010b[22] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Ding 2011[14] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Du 2011[15] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Duo 2011[16] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Jiang 2011[19] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Yang 2011[28] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Chen 2012[29] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wang 2012[32] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Zhang 2012[30] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Chen 2013[12 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Jiang 2013[20] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wang 2013[26] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Petrides 2015[23] | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| kappac | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

a Other biases considered include including study-specific biases or concerns about fraudulent results

b If any of seven items are coded high-risk of bias the overall study is classified as high-risk, if all seven items are coded as low-risk the overall study is classified as low-risk; all other studies (i.e., those with some items coded ‘unclear’ and no items coded as high-risk) are classified as ‘unclear’

c Weighted kappa values for inter-rater reliability of the two independent coders who assessed each item for the 23 studies

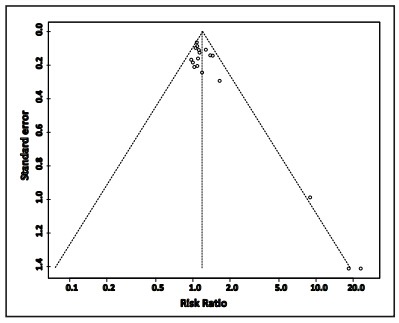

The funnel plot of the primary outcome of efficacy provided by 18 of the studies[9,10,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,22,23,26,27,29,30,31,32] is shown in Figure 2. There is substantial publication bias; the three smaller studies[9,19,23] were more likely to find a significant advantage for combined treatment with ECT plus antipsychotic medications versus the sole use of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia.

Figure 2. Funnel plot of publication bias based on the primary outcome measure of efficacy in 18 of the 22 included studies.

As shown in Table 4, based on the GRADE criteria the overall quality of the evidence about effectiveness (defined as percent of patients who showed ‘improvement’ by the end of the trial) was rated as ‘moderate’, but the quality of evidence about general side effects (assessed using TESS), cognitive functioning, and overall functioning was rated as ‘very low’. The six studies that provided data about general side effects based on the TESS score[10,13,18,20,28,30] had very heterogeneous results and, thus, could not be pooled in a meta-analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of meta-analysis and GRADE assessments of quality of data about different outcome measures of randomized compared trials comparing ECT and antipsychotic medication versus medication alone in the treatment of treatment refractory schizophrenia

| outcomes | number of studies (pooled sample) |

test for heterogeneity | analytic model | test for overall effect | estimate | 95% confidence interval of estimate | GRADE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p | Z | p | ||||||

| effectiveness | 18 (1394) | 38% | 0.05 | fixed | 7.51 | <0.001 | 1.31 (RR) | 1.22-1.41 | moderate |

| side effect (TESS) | 6 (534) | 81% | < 0.01 | - | - | - | - | - | very low |

| cognitive function | 4 (199) | 65% | 0.04 | random | 1.14 | 0.25 | -0.28 (SMD) | -0.77-0.20 | very low |

| overall function | 3 (157) | 48% | 0.14 | fixed | 7.26 | <0.01 | 10.25 (MD) | 7.48-13.01 | very low |

GRADE, Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

ECT, electroconvulsive therapy

TESS, Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale[37]

RR, risk ratio

SMD, standardized mean difference

MD, mean difference

3.3. Efficacy

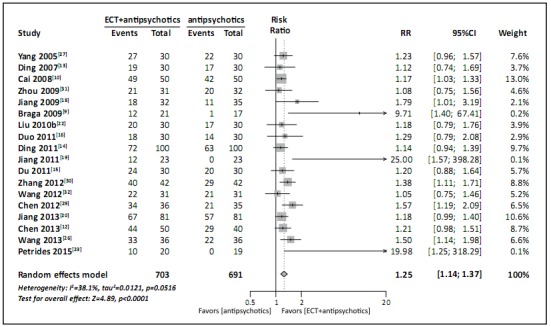

Eighteen studies with a pooled sample of 1394 participants provided information on efficacy (i.e., percent of cases that achieved the study-specific criteria for ‘improvement’) at the end of the trial.[9,10,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,22,23,26,27,29,30,31,32] The I2 was satisfactory but the corresponding p-value was too small to justify considering the results of the various studies homogeneous (I2=38%, p=0.05), so a random-effect model was conducted. The result, shown in Figure 3, indicate that patients with refractory schizophrenia treated with the combination of ECT and antipsychotic medications are more likely to experience symptomatic improvement than patients treated with antipsychotic medications alone (RR=1.25, 95% CI =1.14-1.37).

Figure 3. Forest plot of proportion of patients with refractory schizophrenia who achieve study-specific criteria of improvement following treatment with either ECT plus antipsychotic medications or antipsychotic medications alone.

3.4. Adverse effects

As shown in Table 5, six studies with a pooled sample of 534 participants reported TESS scores.[10,13,18,20,28,30] The TESS results from these studies were quite heterogeneous, so it is only possible to provide a descriptive assessment of the results. Using the overall TESS score as the measure of the severity of adverse events, three of the studies[18,28,30] showed no significant differences between the two groups, one study[13] found significantly more severe adverse events in the ECT plus antipsychotic medication group, and two studies[10,20] found significantly more severe adverse events in the group that only received antipsychotic medication.

Table 5.

Results for six studies that used the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS) to assess adverse events in patients with refractory schizophrenia treated with combined electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and antipsychotic medication versus those treated with antipsychotic medication alone

| study | ECT + medication group | medication only group | mean difference [95% CI] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean (sd) | n | mean (sd) | |||

| Ding, 2007[13] | 30 | 2.7 (2.4) | 30 | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.44 [0.47,2.41] | |

| Cai 2008[10] | 50 | 2.9 (1.6) | 50 | 3.7 (2.0) | -0.76 [-1.47,-0.05] | |

| Jiang 2009[18] | 32 | 7.7 (5.9) | 35 | 6.8 (5.4) | 0.95 [-1.78,3.68] | |

| Yang 2011[28] | 30 | 8.2 (6.1) | 31 | 7.9 (5.9) | 0.34 [-2.69,3.37] | |

| Zhang 2012[30] | 42 | 5.9 (2.7) | 42 | 6.9 (2.7) | -0.98 [-2.13,0.17] | |

| Jiang 2013[20] | 81 | 3.4 (0.8) | 81 | 4.5 (1.1) | -1.10 [-1.40,-0.80] | |

Thirteen studies[13,14,15,18,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] provided information about specific adverse events. As shown in Table 6, a total of 26 kinds of adverse events were reported. Meta-analysis of the results identified two adverse effects that were reported at a significantly higher frequency by patients receiving combined treatment with ECT plus antipsychotic medication than by patients treated with antipsychotic medications alone: headache (based on a pooled sample of 517 individuals from eight studies, OR=9.10, 95%CI=3.97-20.86) and memory impairment (based on a pooled sample of 577 individuals from seven studies, OR=6.48, 95%CI=3.54-11.87).

Table 6.

Comparison of incidence of different adverse events in patients with refractory schizophrenia treated with electroconvulsive therapy and antipsychotic medications versus those treated only with antipsychotic medications

| events | number of studies | participants | I2 | p | statistical method (risk ratio) | effect estimate [95% C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abnormal electrocardiogram | 6 | 383 | 32% | 0.20 | fixed | 0.83 [0.58,1.19] |

| abnormal electroencephalogram | 2 | 123 | 85% | 0.01 | random | 1.97 [0.31,12.65] |

| abnormal liver enzymes | 7 | 448 | 0% | 0.80 | fixed | 0.67 [0.34,1.34] |

| akathisia | 4 | 263 | 0% | 0.80 | fixed | 0.69 [0.37,1.26] |

| anorexia/decreased appetite | 1 | 60 | not applicable | fixed | 2.00 [0.19,20.90] | |

| blurred vision | 3 | 203 | 0% | 0.95 | fixed | 0.92 [0.37,2.26] |

| constipation | 6 | 388 | 42% | 0.13 | fixed | 0.52 [0.37,0.73] |

| decreased motor activity | 2 | 140 | 71% | 0.06 | random | 0.22 [0.02,3.10] |

| dizziness | 5 | 323 | 51% | 0.08 | random | 1.23 [0.56,2.70] |

| drowsiness | 7 | 457 | 61% | 0.02 | random | 0.71 [0.35,1.42] |

| dry mouth | 3 | 203 | 0% | 0.85 | fixed | 1.03 [0.49,2.18] |

| Extrapyramidal symptoms | 3 | 182 | 0% | 0.40 | fixed | 1.74 [0.84,3.58] |

| headache | 8 | 517 | 7% | 0.37 | fixed | 9.10 [3.97,20.86] |

| hypotension | 1 | 60 | not applicable | fixed | 0.33 [0.01,7.87] | |

| increased salivation | 5 | 328 | 54% | 0.07 | random | 0.41[0.18,0.93] |

| insomnia | 5 | 322 | 59% | 0.05 | random | 0.46 [0.07,3.22] |

| leukopenia | 5 | 336 | 0% | 0.49 | fixed | 0.31 [0.12,0.82] |

| memory impairment | 7 | 577 | 36% | 0.16 | fixed | 6.48 [3.54,11.87] |

| menstrual disorder | 1 | 60 | not applicable | fixed | 1.50 [0.27,8.34] | |

| nasal congestion | 1 | 63 | not applicable | fixed | 3.09 [0.13,73.17] | |

| nausea/vomiting | 5 | 334 | 0% | 0.94 | fixed | 2.33 [0.99,5.49] |

| rigidity | 2 | 140 | 0% | 0.65 | fixed | 0.69 [0.40,1.18] |

| tachycardia | 4 | 268 | 0% | 0.58 | fixed | 0.77 [0.50,1.21] |

| tremors | 2 | 140 | 0% | 0.82 | fixed | 0.77 [0.43,1.38] |

| weakness | 3 | 185 | 0% | 0.43 | fixed | 0.25 [0.11,0.59] |

| weight gain | 7 | 468 | 4% | 0.40 | fixed | 0.61 [0.43,0.87] |

3.5. Cognitive function

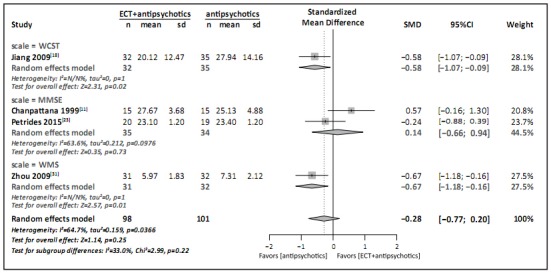

Five studies reported cognitive function results,[11,18,19,23,31] but only four of them had data that could be pooled in a meta-analysis.[11,18,23,31] The meta-analysis (Figure 4) comparing the standardized mean difference (SMD) in the final scale scores between groups used the total MMSE score[41] for the two studies that used MMSE,[11,23] the perseverative errors score from the WCST[42] for the study that used the WCST,[18] and the picture recognition score from the WMS[43] for the study that use the WMS.[31] The results for the study that use the WCST and for the study that used the WMS indicate significantly greater cognitive impairment in the group treated with ECT and antipsychotic medications, but when pooled with results from the two studies that use MMSE to assess cognitive functioning, the overall results were not significantly different between the two groups (SMD=-0.28, 95%CI=-0.77~0.20). However, as stated previously (Table 4), the quality of evidence from these studies was rated as ‘very low’.

Figure 4. Forest plot of standardized mean difference in scores of three cognitive measures among patients with refractory schizophrenia following treatment with either ECT plus antipsychotic medications or antipsychotic medications alone.

3.6. Overall function

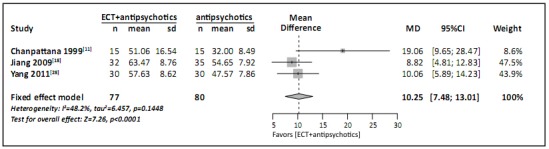

The meta-analysis of the three studies[9,16,26] that used the GAF to assess overall functioning at the end of the trial is shown in Figure 5. (The study that employed CGI to assess overall functioning[17] could not be included because the report for the study did not include a standard deviation for the mean CGI score.) For each of the three studies and for the pooled result for the studies, the overall functioning at the end of the study was significantly better in the ECT plus antipsychotic medication group than in the group treated with antipsychotic medications alone (MD=10.25, 95%CI=7.48-13.01). However,the quality of evidence for these studies was rated as ‘very low’ based on the GRADE criteria.

Figure 5. Forest plot of mean difference in scores of the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF) among patients with refractory schizophrenia following treatment with either ECT plus antipsychotic medications or antipsychotic medications alone.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

Since the operational definition of ‘refractory schizophrenia’ was first proposed by Kane in 1995,[3] there has been increasing research about the identification and management of these hard-totreat patients. Previous meta-analyses conclude that clozapine can improve psychiatric symptoms and decrease the occurence of extrapyramidal side effects for about half of these refractory patients.[24] ECT is an option for increasing the proportion of refractory patients who achieve satisfactory clinical outcomes, but there are few studies addressing this issue, possibly because of the reluctance of patients and clinicians to use ECT.

Extensive screening of English-language and Chinese-language databases identified 22 RCTs on this topic, among which 4 were in English and 18 were in Chinese, suggesting that the use of ECT as an adjunctive treatment in refractory schizophrenia is less controversial in China than abroad. The pooled result about efficacy (defined as the proportion of participants that achieved the study-specific criteria for ‘improvement’) included 1394 individuals that participated in 18 studies. It clearly indicated a superior clinical result for refractory patients who received combined treatment with ECT and antipsychotic medications (RR=1.25, 95% CI=1.14~1.37). Moreover, the quality of the evidence for this outcome using the GRADE criteria was rated as ‘moderate’, which means that the result is reasonably robust. We also found that patients who received combined treatment were much more likely to report headaches and memory impairment during the treatment and to have higher overall functioning at the end of treatment, but the quality of evidence for these findings was rated as ‘very low’.

4.2. Limitations

The low quality of the RCTs identified for inclusion in this review seriously limits the validity of the results, particularly the results related to the occurrence of adverse effects, cognitive impairment, and overall functioning. As shown in our assessment of the risk of bias, the main problem was that most of the reports on the included studies did not provide details about the methods employed in the study, resulting in an overall rating of the assessment of risk of bias of ‘uncertain’ in 21 of the 22 included studies.

The most troubling problem was lack of blinding. Double blinding is difficult to achieve in studies involving ECT because of the practical and ethical problems of administering ‘sham ECT’, so it is not surprising that sham ECT was only used in 1 of the 22 included studies. On the other hand,it is relatively easy to blind raters who assess the outcome measures,but this was only done in 3 of the 22 studies. We also identified a clear publication bias, favoring publication of studies that find superior outcomes among patients receiving both ECT and antipsychotic medication.

4.3. Implication

The current study systematically reviewed and evaluated all available RCTs about the efficacy and safety of the combined use of antipsychotics and ECT in the treatment of patients with refractory schizophrenia. Meta-analysis of the 22 identified studies found that compared to treatment with antipsychotic medications alone,combined treatment with ECT and antipsychotic medication resulted in improved clinical outcomes, higher rates of headaches and memory impairment during treatment, and better overall functioning at the end of treatment. However, given the low quality of the evidence in the studies and the existence of publication bias,these results must be considered suggestive,not definitive. Better designed studies that include more detailed description of the methods employed are needed to confirm (or disprove) these results.

Studies about the use of ECT in schizophrenia are relatively common in China, so this is one area in which China could make an important contribution to the global literature. However, Chinese mental health researchers will not be able to make useful international contributions until they resolve common problems in the design and implementation of their studies, problems that could be easily addressed by strict adherence to the recommendations for RCTs in the CONSORT statement.[5]

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers of this analysis for their useful comments.

Biographies

Wenzheng Wang graduated from Shanghai Jiaotong University in 2014 with a doctor’s degree in clinical medicine. Since 2009 she has worked at the Shanghai Mental Health Center as a resident physician. Her research interest is substance abuse, especially alcohol and tobacco abuse.

Chengcheng Pu graduated from Peking University in 2013 with a doctor’s degree in clinical medicine. Since then he has worked at the No.6 Hospital of Peking University as an attending physician. His research interest is the identification and treatment of schizophrenia.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Center (SHDC12014111), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (13z2260500, 14411961400), the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (2013SY003, 2013SY011, 2014ZYJB0002), and the Shanghai Health System Leadership in Health Research Program (XBR2011005). The funding agencies played no role in the design, analysis, or write up of the results of the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Van Sant SP, Buckley PF. Pharmacotherapy for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:411–434. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conley RR, Buchanan RW. Evaluation of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophre Bull. 1997;23:663–674. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane JM. Treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;57:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu TB, Zang DX. [Treatment-resistant schizophrenia] Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2000;10:114. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.10053220.2000.02.040. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley Online Library; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CB, He YL, Zhang MY. [Reasonable application of the consistency test methods] Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2000;12:228–230. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2000.04.016. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braga RJ, Mendelowitz AJ, Fink M, Schooler NR, Bailine SH, Malur C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ECT in clozapine-refractory schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;S8:212S–213S. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai XY, Lin LJ, Su Y, Zheng YM, Luo XF, Yang FY, et al. [The case-control study of MECT combined clozapine in the treatment of refractory schizophrenia] Zhongguo Min Kang Yi Xue. 2008;20:1423–1424. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chanpattana W, Chakrabhand MS, Sackeim HA, Kitaroonchai W, Kongsakon R, Techakasem P, et al. Continuation ECT in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a controlled study. J ECT. 1999;15:178–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen QL, Weng KH, Xu ZQ, Wang XL, et al. [A control study of antipsychotic combined with MECT in treatment-resistant schizophrenia] Lin Chuang Xin Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 2013;19:204–206. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2013.03.007-0204-03. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding YF, Zheng SQ, Song CH. [The comparison study of curative effect of risperidone and modified electroconvulsive shock therapy in refractory schizophrenia] Jing Shen Yi XueZa Zhi. 2007;20:397–398. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-7201.2007.06.025. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding L, Ma YJ. [clinical study of MECT on 100 patients with refractory schizophrenia] Zhongguo She Qu Yi Shi: Yi Xue Zhuan Ye. 2011;13(31):82–83. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2011.31.075. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du ZH, Li FM, Liu SP. [Analysis of efficacy and safety of clozapine combined with MECT treatment on refractory schizophrenia] Zhongguo Min Kang Yi Xue. 2011;23(24):3056. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2011.24.035. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duo J. [Clinical treatment analysis of refractory schizophrenia] Yi Xue Xin Xi: Zhong Xun Kan. 2011;24(5):2003–2004. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2011.05.377. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goswami U, Kumar U, Singh B. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in treatment resistant schizophreinia: A double blind study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45(1):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang XQ, Yang KR, Zhou B, Jin P, Zheng LF, Gao XF, et al. [Studyon efficacy of modified electroconvulsive therapy(MECT) together with risperidone in treatment treatment-resistant schizophrenia(TRS)] Zhongguo Shen Jing Jing Shen Ji BingZa Zhi. 2009;35(2):79–83. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0152.2009.02.005. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.iang SH, Huang SJ, Wei LQ. [Clinical analysis of MECT on 46 patients with refractory schizophrenia] Zhongguo She Qu Yi Shi: Yi Xue Zhuan Ye. 2011;13(17):57. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2011.17.055. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang ZW. [Clinical analysis on MECT combined with ziprasidone in treatment of patients with refractory schizophrenia] Lin Chuang He Shi Yan Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;12(17):1394–1395. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-4695.2013.17.024. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu FQ, Gong GQ. [Effect of schizophrenia MECT] Zhongguo Xian Dai Yi Sheng. 2010;48(1):29. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-9701.2010.01.015. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu GJ, Liu GS, Zhang XB. [A control study of risperidone combined with MECT in refractory schizophrenia] Lin Chuang Xin Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 2010;16(1):8–10. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2010.01.005.0008-03. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrides G, Malur C, Braga RJ, Bailine SH, Schooler NR, Malhotra AK, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy augmentation in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a prospective randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13060787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinclair D, Adams CE. Treatment resistant schizophrenia: acomprehensive survey of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:253. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartling L, Hamm MP, Milne A, Vandermeer B, Santaguida PL, Ansari M, et al. Testing the risk of bias tool showed low reliability between individual reviewers and across consensus assessments of reviewer pairs. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(9):973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F, Guo DW. [Efficacy study of olanzapine combined with MECT on the treatment of refractory schizophrenia] Lin Chuang He Li Yong Yao Za Zhi. 2013;6(24):99. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-3296.2013.24.082. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang KJ, Liu TB, Yang HC, Gao H, Wu DH, Feng Z, et al. [Acomparative study of MEC T combined with excitement aggressive behavior treatment on refractory schizophrenia] Zhongguo Min Kang Yi Xue. 2005;17:485–486. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang KR, Jiang XQ , Mao FR, Zheng LF, Zhou B, Jin P, et al. [Modified electroconvulsive therapy combined with risperidone in treatment of negative symptoms in treatment-resistant schizophrenia] Zhejiang Yi Xue. 2011;33:1602–1605. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2785.2011.11.012. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan DR. [Comparative analysis of MECT treatment on refractory schizophrenia] Xin jiang Yi Xue. 2012;42:57–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5183.2012.09.016. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang SR, Zhang JL, Li XZ, Yang YF, Lang SY. [Observational study of the Efficacy of MECT combined olanzapine on the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. Ren Min Jun Yi. 2012;2:39. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou HJ, Mao ZR, Chen YJ, Song BF, Shi DQ. [A comparative study of modified electroconvulsive therapy combined with Olanzapine in the treatment of treatment-refractory schizophrenia] Shen Jing Ji Bing Yu Jing Shen Wei Sheng. 2009;9(4):328–331. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6574.2009.04.017. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YB. [Comparative study of quetiapine combined MECT on the treatment of female refractory schizophrenia] Dang Dai Yi Xue. 2012;18(22):133–134. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-4393.2012.22.100. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen YF. [Chinese Mental Disorder Diagnosis andClassification Criteria] Jinan: Shandong Science and Technology Press; 2001. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TRim 2000) American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kay SR, Flszbein A, Opfer LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang MY. [Psychiatric Rating Scale Manual] Hunan: Hunan Science and Technology Press; 1998. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th text revision ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. pp. 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. Lowa City: University of Lowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Lowa City: University of Lowa; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockrell JR, Folstein MF. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK. Wisconsin card sorting test-64 card version (WCST-64) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chelune GJ, Bornstein RA, Prifitera A. Advances in Psychological Assessment. Springer; 1990. The Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guy W. Psychiatric Measures. Washington DC: APA; 2000. Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale. Revised by Rush J. [Google Scholar]