Abstract

Objective

Transition may be associated with poor health outcomes, but limited data exist regarding inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Acquisition of self-management skills is felt to be important to this process. IBD specific checklists of such skills have been developed to aid in transition, but none has been well studied or validated. This study aimed to describe self-assessment of ability to perform tasks on one of these checklists and to explore the relationship to patient age and disease duration.

Methods

10–21yr old patients with IBD were recruited. An iPad survey queried the patients for self-assessment of ability to perform specific self-management tasks. Task categories included: basic knowledge of IBD, doctor visits, medications and other treatments, and disease management. Associations with age and disease duration were tested with Spearman rank correlation.

Results

67 patients (31 male) with Crohn's disease (n=40), ulcerative colitis (n=25), and indeterminate colitis (n=2) participated. Mean patient age was 15.8 ±2.5yr with median disease duration of 5yr (2mo-14yr). The proportion of patients who self-reported ability to complete a task without help increased with age for most tasks including: telling others my diagnosis (ρ=0.43, p=0.003), telling medical staff I do not like or am having trouble following a treatment (ρ=0.37, p=0.003), and naming my medications (ρ=0.28, p=0.02). No task significantly improved with disease duration.

Conclusions

Self-assessment of ability to perform some key tasks of transition appears to improve with age, but not with disease duration. Importantly, communication with the medical team did not improve with age, despite being of critical importance to functioning within an adult care model.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic immune mediated inflammatory condition that includes Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis. IBD represents a significant burden of disease in the United States affecting more than 1.4 million Americans.(1) An estimated 20–30% of patients with IBD initially present before the age of 18 years, and the incidence of IBD appears to be rising among all age groups. (2, 3) Additionally, early onset of IBD in the pediatric age range has been associated with more severe disease manifestations then adult onset.(4)

Pediatric patients with IBD are typically cared for by pediatric gastroenterologists who have been trained to manage these diseases with special attention to the aspects of the illness that are unique to childhood and adolescence. All forms of IBD are lifelong illnesses that are rarely fatal, making it necessary that these patients transition from a pediatric to an adult gastroenterologist as they pass from adolescence to adulthood.

Transition is the active process of a purposeful, planned movement from child-centered to adult-centered care.(5) This process includes the transition of responsibility for health-related tasks from parent to patient, as well as preparation for transfer to an adult health-care system.(6) Transfer of care is when a patient and his or her medical records move from one provider to another at a distinct point in time.(7) Attention to this period of transition is important due to the risk of decreased adherence to medications and potential loss to follow-up. A good physician-patient relationship with agreement on goals of therapy is important for medication adherence,(8) and by the very nature of the transition process this relationship must be disrupted and a new one formed. This period of transition and transfer may be associated with poorer health outcomes,(9) but little research has been done regarding transition and transfer in patients with IBD. There is widespread agreement that as part of the transition process adolescents need to acquire the self-management skills necessary to function independent of parents and staff in order to be ready to transfer to an adult health-care system.(10, 11) However, at this time no ideal model for a transition process to aid in the acquisition of these skills exists.

Checklists designed to assess ability to perform self-management skills have recently been created by the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Foundation as well as the ImproveCareNow Network (ICN), a multi-center collaboration for quality improvement in pediatric IBD. Neither of these checklists has been well-studied or validated. The aims of the present study were to: 1) describe patient responses on a survey querying self-assessment of the patient’s ability to perform the self-management tasks listed on one of these transition checklists, and 2) to explore the relationship between self-assessed ability to perform tasks on the checklist, duration of disease, and age of the patient at the time of assessment.

Methods

Subjects and Ethics

This study was a cross-sectional survey involving a convenience sample of patients ages 10–21 attending an outpatient Pediatric Gastroenterology appointment. At our institution patients are typically transferred to an adult gastroenterologist between the ages of 18–22, although we do not have a formalized transition process or materials. We do not have a specific IBD clinic at our institution. Patients are seen by their primary pediatric gastroenterologist during that physician’s designated clinic time. At the time of this study there were four faculty and six fellows routinely caring for pediatric patients with IBD.

Inclusion in the study required IBD diagnosed by standard means(12). Exclusion criteria included known developmental delay. All eligible patients were identified through the medical record system at the University of Michigan Health System. Eligible patients were approached sequentially on days on which research personnel (E.W. and B.S) were available. This study was part of a quality improvement effort and was considered exempt and not regulated by the University of Michigan institutional review board.

Development and Implementation of the Survey

The survey was created using Qualtrics (Provo, UT) survey software and administered via an iPad (Apple, Cupertino, CA) through a Qualtrics web link. The patient completed the survey on an iPad. Completion of the survey took place in the presence of one of the study team members. In order to avoid parental influence on responses patients were asked to direct any questions regarding the survey to the study team member. The survey included 23 questions asking the patient to rate his/her ability to perform certain tasks related to transition, which were taken directly from the ImproveCareNow (ICN) Self-Management Handbook Transition Checklist and all checklist questions were included.(13) The questions encompassed four domains: 1) “Basic knowledge about IBD” 2) “Doctor Visits” 3) “Medication and other treatments” 4) “Disease Management.” For each question, there were three possible responses: “I can do this on my own with no help from others,” “I can do this with some help from others”, or “I cannot do this or need a lot of help from others.” The survey included additional questions were aimed at self-identifying patient characteristics including: age (in years), gender, diagnosis, duration of disease, disease distribution, hospitalization and remission history, medication adherence and surgical history (See Supplemental Figure 1 for patient survey).

Statistical Analysis

Data were extracted from Qualtrics in SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) format and converted to Stata format using Stat Transfer 11.2 (Circle Systems, Seattle, WA). Data analyses were performed with Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX). Associations with age and disease duration were tested using Spearman rank correlation using age in years as an integer variable. Disease duration was broken down into 9 categories along which the Spearman rank was calculated. These categories were: <6 months, 6–12 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4–5 years, 6–8 years, 9–10 years, >10 years. To facilitate graphic representation of age-related associations, patients were grouped by age into categories (<14 years, 14–17 years, >17 years). Patients were also grouped by disease duration (<3 years, 3–5 years and >5 years) to facilitate graphic representation of the data.

For the purpose of calculating a score for the portion of the survey containing the task-related questions each response was given a number value as follows: “I cannot do this, or need a lot of help from others” = 1, “I can do this with some help from others” = 2, “I can do this on my own with no help from others” = 3. An overall score as well as subcategory scores for categories of questions were tabulated for each patient. The best possible overall score is 69. These scores were analyzed for association with age and disease duration using Spearman rank correlation as described above.

Results

71 patients were asked to participate; 2 refused. None of the identified patients had known developmental delay and therefore no patients were excluded based on this criterion. One patient was excluded due to failure to answer any questions in the questionnaire. One completed questionnaire was excluded due to observed parental influence on the answers. Data from a total of 67 patients were analyzed. Consort diagram is provided in Supplemental Figure 2.

Demographic information was self-reported on the patient survey (See Table 1). There were no differences in the age at the time of study (p=0.92) or disease duration (p=0.58) between patients with Crohn’s disease or those with ulcerative colitis.

Table 1. Patient Demographics.

Based on survey answers

| CD | UC | IC | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 40 | 25 | 2 | 67 |

| Age at study, yr (mean ± SD) | 7.7 ± 2.5 | 8 ± 2.6 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 2.5 |

| <14 | 8 | 4 | - | 12 |

| 14–17 | 21 | 14 | 2 | 37 |

| 18+ | 11 | 7 | - | 18 |

| Disease duration, yr (n, %)* | ||||

| <1 | 6 (15) | 1 (4) | 1 (50) | 8 (12) |

| 1–3 | 7 (18) | 6 (24) | - | 13 (19) |

| 4–5 | 10 (25) | 6 (24) | 1 (50) | 17 (25) |

| 6–8 | 6 (15) | 4 (16) | - | 10 (14) |

| >8 | 3 (7) | 4 (16) | - | 7 (10) |

| Gender (n, %)* | ||||

| Female | 21 (53) | 12 (48) | 2 (100) | 35 (52) |

| Male | 19 (48) | 13 (52) | - | 32 (48) |

| Disease in remission (n, %)* | ||||

| Yes | 25 (63) | 17 (68) | 1 (50) | 43 (64) |

| No | 14 (35) | 7 (28) | 1 (50) | 22 (33) |

| Length of remission, yr (n, %**) | ||||

| <0.5 | 6 (24) | 6 (35) | - | 12 (28) |

| 0.5–1 | 3 (12) | 1 (6) | 1 (100) | 5 (12) |

| 1 | 1 (4) | 5 (29) | - | 6 (14) |

| 2 | - | 2 (12) | - | 2 (5) |

| ≥3 | 14 (56) | 1 (6) | - | 15 (35) |

| Prior hospitalization for IBD (n, %) | ||||

| Yes | 25 (63) | 15 (60) | 2 (100) | 42 (63) |

| No | 15 (38) | 10 (40) | - | 25 (37) |

| Prior surgery for IBD (n, %) | ||||

| Yes | 8 (20) | 3 (12) | 1 (50) | 12 (18) |

| No | 32 (80) | 22 (88) | 1 (50) | 55 (82) |

n=number; yr = years; SD = standard deviation; CD = Crohn’s disease; UC = ulcerative colitis; IC = indeterminate colitis

Sum of answers less than total because not all patients answered corresponding question

Percentile for remission based the N of those who answered they were in remission. N = 43 total in remission (25 with CD, 17 with UC and 1 with IC)

Survey Scores and Association with Age and Disease Duration

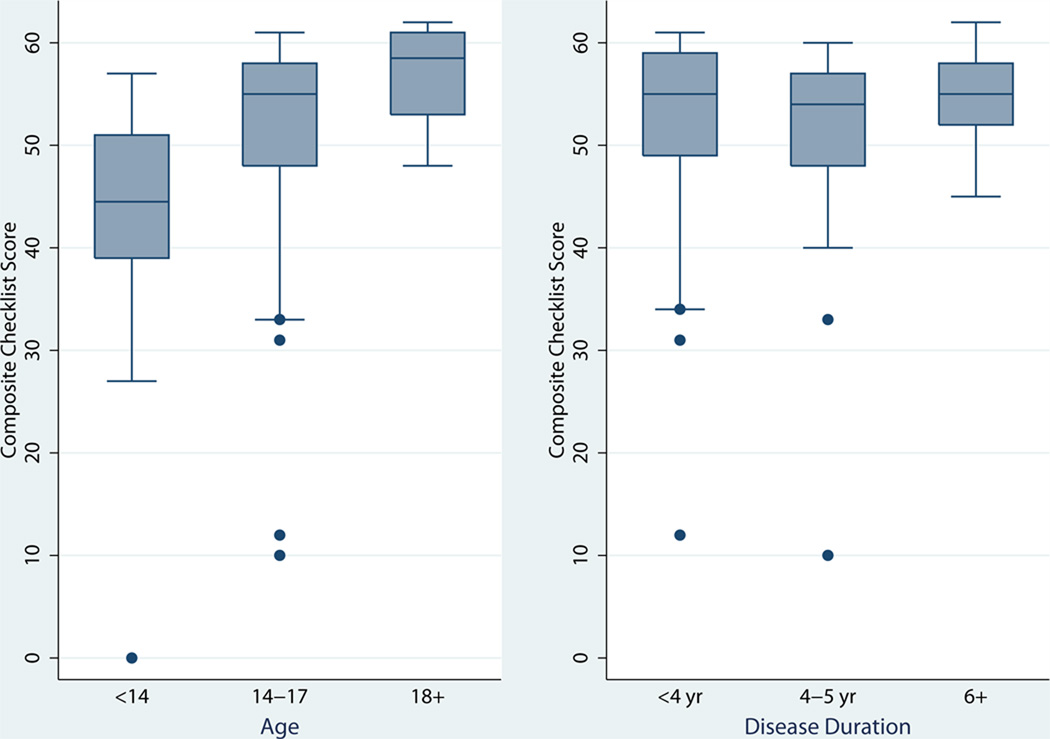

The patient’s responses to each task were scored as described above in order to tabulate an overall score for the tasks queried. The mean scores for each age group were 38.9, 50.5 and 56.9 for <14 years, 14–17 years and 18+ years respectively. We found that there was significant improvement with increasing age of the patient (ρ =0.62, p<0.0001, n=69), but not with the duration of disease (p=0.46, n=55) (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Post hoc composite checklist score calculated from scores of each question. Box plot represents mean and interquartile ranges of scored patient responses across age and disease duration.

When the score was subdivided by skill set, we found that there was improvement with older age for all skill sets including: Basic Disease Knowledge (ρ=0.60,p<0.0001), Doctor Visits (ρ =0.30, p=0.013), Medications and Treatments (ρ =0.520, p<0.0001), and Disease Management (ρ =0.61, p<0.0001). There was no improvement with longer disease duration for any of the skill sets (p=0.091, p=0.80, p=0.89, p=0.23 respectively).

Tasks for Which Self-Assessment Did Not Improve with Increasing Age

As reflected in the total score, there was improvement with increasing age in self-assessed ability for the majority of the tasks queried (See Table 2). The tasks that did not show improvement with age were: “ask questions during medical appointments” (p=0.44), “answer questions during medical appointments” (p=0.27); “get medications when it is time to take them” (p=0.061); “tell others why I take each medication” (p=0.055); and “know what other services are available to me (ex. Social worker, dietician, psychologist)” (p=0.066). There were no associations noted between any of the tasks and disease duration (See Table 2).

Table 2. Change in Patient Self-Assessment of Skill By Age and Duration of Disease.

Percentage of Patients Self-Assessing as “Can do with no help”

| Age of patient at survey* | Disease duration* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | <14 yr | 18+ yr | p-value** | <2 yr | 6+ yr | p-value** |

| BASIC KNOWLEDGE | ||||||

| I can tell others what my diagnosis is | 45% | 94% | 0.0003 | 58% | 76% | 0.36 |

| I can explain how my illness affects my body | 50% | 83% | 0.021 | 64% | 82% | 0.27 |

| I can tell when I am having a flare up or when I need to go see the doctor | 42% | 72% | 0.0088 | 64% | 65% | 0.98 |

| I can list the foods and/or activities that make me feel bad or uncomfortable | 64% | 94% | 0.0012 | 82% | 88% | 0.47 |

| DOCTOR VISIT | ||||||

| I can tell others the name of my Gastroenterologist | 50% | 100% | 0.0002 | 82% | 94% | 0.31 |

| I can answer questions during mymedical appointments | 64% | 67% | 0.27 | 67% | 65% | 0.99 |

| I can ask questions during my medical appointments | 58% | 61% | 0.44 | 36% | 53% | 0.53 |

| I can tell my doctor or nurse if I do not like my treatment or am having trouble following it | 36% | 83% | 0.0026 | 64% | 71% | 0.88 |

| I feel comfortable talking with my doctors or nurses if I do not understand what they are talking about during medical appointments | 58% | 93% | 0.0092 | 73% | 94% | 0.14 |

| MEDICATIONS | ||||||

| I can name my medications and/or treatments | 58% | 89% | 0.020 | 83% | 88% | 0.70 |

| I can tell others when I take each medication and how much | 45% | 78% | 0.044 | 74% | 65% | 0.64 |

| I can tell others why I take each medication | 58% | 89% | 0.055 | 64% | 88% | 0.16 |

| I can get the medications I need when it is time for me to take them | 73% | 83% | 0.061 | 82% | 88% | 0.38 |

| I can make changes in my medications as recommended by my gastroenterologist | 33% | 72% | 0.0012 | 73% | 53% | 0.57 |

| I can tell others what will happen to me if I do not take my medications correctly | 50% | 89% | 0.011 | 70% | 82% | 0.34 |

| I can tell what medications I cannot take because they might interact with the medications I already take | 9% | 44% | 0.017 | 55% | 24% | 0.18 |

| DISEASE MANAGEMENT | Age of patient at survey* | Disease duration* | ||||

| Question | <14 yr | 18+ yr | p-value** | <2 yr | 6+ yr | p-value** |

| I can tell my parents when I am running out of medications | 50% | 94% | 0.0085 | 75% | 82% | 0.63 |

| I can call the pharmacy to get refills on my medications | 9% | 56% | <0.0001 | 0% | 29% | 0.098 |

| I can prepare my medication in advance to accommodate long trips, overnights etc. | 27% | 94% | 0.0002 | 73% | 82% | 0.39 |

| I call the doctor to schedule my medical appointments | 9% | 44% | <0.0001 | 0% | 18% | 0.087 |

| I know what other health services (eg. CCFA, social worker, dietician, psychologist) are available to me | 27% | 50% | 0.0662 | 27% | 47% | 0.4647 |

| I can explain the impact of smoking on my disease | 9% | 56% | 0.0108 | 18% | 18% | 0.2627 |

| I can explain the impact of alcohol on my disease | 0% | 56% | 0.0014 | 27% | 12% | 0.1584 |

Categorized for illustration purposes. Statistical analysis performed using ordinal age or disease duration in years.

P-values refer to Spearman ranked sum of question response vs. data range in years.

Self-Assessed Ability for Patients 18 Years and Older

By age 18 greater than 80% of patients self-assessed that they “can do without help” the majority of the tasks queried. Tasks for which greater than 20% of the patients over age 18 self-assessed that they cannot “do without help” include: “recognize a flare of disease or know when I need to see the doctor”; “answer questions during medical appointments”; “ask questions during medical appointments”; “tell others when I take each medication and how much”; “make changes to my medications as recommended by my gastroenterologist”; “tell what medications I cannot take because they will interact with the medicines that I already take”; “call the pharmacy to get refills of my medications”; “call the doctor’s office to schedule appointments”; “know what other health services are available to me”; “can explain the impact of smoking/alcohol on my disease.” (See Table 2.)

Discussion

The acquisition of self-management skills is considered an important part of the transition process and preparation for successful transfer to an adult-centered care model. (7) Several checklists have been developed to aid physicians in the process of assessing self-management skills in their patients, but none have yet been validated with IBD populations at this time. The goal of this study was to use one of these checklists to systematically gather data from adolescent patients with IBD regarding self-management skills. In addition, we sought to examine the associations between self-assessment of self-management skills and patient age and duration of disease.

Our study found that self-assessed ability to perform self-management tasks related to IBD seems to improve with age, but not with disease duration. This was found to be true across all sub-categories of skills. Based on these findings it appears that age, rather than length of time living with IBD, has a greater impact on acquisition of IBD-related self-management tasks. This is consistent with findings in other chronic medical conditions.(6, 11, 14) It is also consistent with recent research by Huang et al. that found that self-efficacy related health-literacy improved with increasing age in patients with IBD.(15)

We also found that for many of the tasks analyzed, >80% of patients age 18 or older reported being able to complete the task without help. While this is encouraging, the remaining patients who do not feel capable of completing these tasks independently would likely have an inadequate skill set to be successful in an autonomous adult health care model.

For example, 17% of patients age 18 and older reported requiring at least some assistance with medications administration. One possible explanation for <100% reporting ability to complete this task might be due to patients who were receiving at least one of their medications via infusion or observed injection. For this subgroup of patients the appropriate response may not be clear as they cannot get their infusion or injection medication without assistance. Revising questions to address medications given by infusion or injection may be helpful for future assessment measures.

Additionally, there were many tasks for which more than 20% of patients age 18 or older reported requiring at least some help, as discussed above. These are important skills for effective medical self-management of IBD, and indicate possible areas for intervention and education in our clinic. For example, only 28% of patients age 18 and older reported that they needed at least some help to “recognize a flare of disease or know when [they] need to go see the doctor.” Some patient difficulty regarding this ability may be due to the nature of a patient’s disease. Minimal or subtle symptoms may be more common in patients with isolated small bowel disease, making it harder to know when their disease is flaring. Therefore an inability to recognize a flare may be due to lack of significant symptoms, rather than lack of understanding or teaching. There were insufficient numbers of patients in this study to analyze this question within the context of disease location. Additionally, we recognize that this is a compound question, so it is somewhat difficult to interpret the response. Future studies should assess the patient’s ability to recognize symptoms associated with exacerbations of disease activity, and study whether this is dependent on disease location. Future studies should also separately assess the patient’s ability to recognize symptoms that warrant urgent medical attention. Both of these are areas where additional teaching may be beneficial.

Additionally, 44% and 56% of patients over the age of 18 need at least some help to “call the pharmacy to get refills” or “call the doctor to schedule my medical appointments”, respectively. This is concerning because these are important self-managements tasks. However, there is the possibility that some of these patients may request refills of medications or request appointments electronically and therefore were unsure how to answer this question. While electronic refill and appointment requests were not available in our practice at the time of this study, the question does not specify our office and if a patient’s pharmacy or general pediatrician did utilize electronic requests at the time it may have altered the answer. Future checklists should make sure wording addresses the current technology as it pertains to self-management skills.

Two other key tasks included the ability to ask and to answer questions during medical appointments, for which 33% and 39% of patients 18 and older, respectively, reported requiring at least some help. These low rates of confidence in active participation at physician visits highlights our need to involve patients more actively in discussions during medical visits. Expecting adolescent patients to have a patient-only portion of all medical visits may improve their confidence in their own ability to participate in discussions about their medical care. This is widely considered good practice throughout most pediatric practices.(16) However, the extent to which this consistently occurs with every visit in general, and specifically in the case of the patients surveyed, was not determined in this study. Previous research has shown that perceived self-efficacy is strongly associated with perceived transfer readiness.(17) Our findings suggest that the use of checklists may be helpful in the transition process by allowing for assessment of perceived ability to complete medical self-management tasks. If this could be done at regular intervals as part of a formal transition program it may help the medical team and the parents to better understand how the patient is progressing in ability for self-management. It may also help the medical team and family target patient-specific areas for intervention to improve transfer readiness.

Alternative tools for assessing self-efficacy in IBD, have been presented by Keefer et al. and Zijlstra et al.(18, 19) Additional research is needed to determine the best method to objectively assess the medical self-management skills of pediatric patients with IBD. It will also be important to develop a tool to assess the allocation of responsibility between child and parent for health-related tasks during the transition process.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. First of all, this study included only one of the transition-readiness assessment checklists that are publically available. Second, the checklist had limitations including: multiple compound questions; a focus on patients prescribed medications that are taken at home rather than intravenous infusions or observed injections; and question wording that does not incorporate current technology allowing for electronic requests for medication refills or appointments. Future versions should limit each listed task to a single distinct skill, allow for an adapted checklist to assess self-management readiness among patients receiving infusions or observed injection medications, and incorporate language that addresses current technology as it pertains to self-managements tasks. Third, this study was conducted with a relatively small sample size recruited from a single center, which limits the generalizability to the larger IBD population. Lastly, we did not control for potential confounders in development of self-management skills such as socioeconomic status or educational level of patient and parents or guardian. It would be useful for further studies to include these assessments to better inform the results. Despite these limitations, this study is an important first step in describing the use of an IBD-specific checklist for assessment of a patient’s perceived ability to perform self-management tasks.

Conclusion

We found that in pediatric patients with IBD, increasing age is associated with improvement in perceived ability to complete medical self-management tasks, while longer disease duration is not. However, age alone is not enough to prepare our pediatric patients to be effective patients in an adult-care model as evidenced by many patients who feel they cannot independently carry out many essential tasks of medical self-management by age 18.

Without an improved transition process our patients will not be adequately prepared to function independently and assume the burden of their own disease management as they transfer to adult care. The transition checklist used in this study was created for the ImproveCareNow Network to fill a need for materials to aid physicians in improving the transition readiness of their patients.(20) Our study highlights that checklists may be a helpful tool for assessment of patient progress toward perceived self-management in a more complete transition process. While checklists may provide information, it is how this information is acted upon to improve the patient’s transition process that will be important. Additionally, checklists must be written to make tasks both more specific and more inclusive to adequately and appropriately assess ability. Most importantly, any checklist or other tool developed must be validated against its ability to predict a patient’s successful transition, transfer to and eventual functioning within adult-centered care.

Further study is needed to establish benchmarks of transition and medical self-management readiness to transition. Additionally, as transition programs are established, outcomes following transfer to adult care must be assessed to better understand which elements of a transition program are most effective. This will allow us to improve the transition process to benefit patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

Dr. Fredericks’ work on this project was supported by a K23 award from the National Institutes of Health (grant number DK090202)

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content Legends

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Patient survey.

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Consort diagram.

References

- 1.Long MD, Hutfless S, Kappelman MD, et al. Challenges in designing a national surveillance program for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2014;20:398–415. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435441.30107.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benchimol EI, To T, Griffiths AM, et al. Outcomes of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: socioeconomic status disparity in a universal-access healthcare system. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;158:960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.039. e961–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, et al. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2010;50:27–31. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b99baa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernier-Massouille G, Balde M, Salleron J, et al. Natural history of pediatric Crohn's disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1106–1113. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:570–576. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredericks EM, Dore-Stites D, Well A, et al. Assessment of transition readiness skills and adherence in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatric transplantation. 2010;14:944–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeisler B, Hyams JS. Transition of management in adolescents with IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:109–115. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Barkun A, et al. Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003;98:1535–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1062–e1070. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viner R. Barriers and good practice in transition from paediatric to adult care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2001;94(Suppl 40):2–4. doi: 10.1177/014107680109440s02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonagh JE, Kelly DA. The challenges and opportunities for transitional care research. Pediatric transplantation. 2010;14:688–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis--the Porto criteria. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005;41:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000163736.30261.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crandall W. A Self Management Handbook for Patients & Families with IBD. Columbus, OH: Nationwide Children's Hospital; 2011. Living Well with Inflammatory Bowel Disease; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredericks EM, Dore-Stites D, Lopez MJ, et al. Transition of pediatric liver transplant recipients to adult care: patient and parent perspectives. Pediatric transplantation. 2011;15:414–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang JS, Tobin A, Tompane T. Clinicians poorly assess health literacy-related readiness for transition to adult care in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suris JC, Michaud PA, Akre C, et al. Health risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1113–e1118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Staa A, van der Stege HA, Jedeloo S, et al. Readiness to transfer to adult care of adolescents with chronic conditions: exploration of associated factors. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Taft TH. The role of self-efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease management: preliminary validation of a disease-specific measure. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17:614–620. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zijlstra M, De Bie C, Breij L, et al. Self-efficacy in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study of the "IBD-yourself", a disease-specific questionnaire. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e375–e385. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, et al. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain. 2000;88:41–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.