Abstract

Accumulation of extracellular matrix derived from glomerular mesangial cells is an early feature of diabetic nephropathy. Ca2+ signals mediated by store–operated Ca2+ channels regulate protein production in a variety of cell types. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of store–operated Ca2+ channels in mesangial cells on extracellular matrix protein expression. In cultured human mesangial cells, activation of store–operated Ca2+ channels by thapsigargin significantly decreased fibronectin protein expression and collagen IV mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner. Conversely, inhibition of the channels by 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate significantly increased the expression of fibronectin and collagen IV. Similarly, overexpression of stromal interacting molecule 1 reduced, but knockdown of calcium release–activated calcium channel protein 1 (Orai1) increased fibronectin protein expression. Furthermore, 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate significantly augmented angiotensin II–induced fibronectin protein expression, whereas thapsigargin abrogated high glucose– and TGF-β1–stimulated matrix protein expression. In vivo knockdown of Orai1 in mesangial cells of mice using a targeted nanoparticle siRNA delivery system resulted in increased expression of glomerular fibronectin and collagen IV, and mice showed significant mesangial expansion compared with controls. Similarly, in vivo knockdown of stromal interacting molecule 1 in mesangial cells by recombinant adeno–associated virus–encoded shRNA markedly increased collagen IV protein expression in renal cortex and caused mesangial expansion in rats. These results suggest that store–operated Ca2+ channels in mesangial cells negatively regulate extracellular matrix protein expression in the kidney, which may serve as an endogenous renoprotective mechanism in diabetes.

Keywords: calcium, diabetic nephropathy, extracellular matrix, fibronectin, ion, channel, mesangial cells

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the most common cause of ESRD.1,2 One of early features of DN includes accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in glomerular mesangium.3,4 This pathologic change in glomerulus may, with time, progress to glomerulosclerosis and ultimately, irreversible ESRD.5,6 Overproduction of ECM, including fibronectin and collagen IV (Col IV), by glomerular mesangial cells (MCs) and deposition of these proteins to mesangium are important contributors to mesangial expansion in the early stage of DN.7–9 Therefore, suppression of ECM production in MCs may be a therapeutic option to protect kidney from diabetic damages.

MCs sit between glomerular capillary loops and play important roles in mesangial matrix homeostasis.7,10,11 MC dysfunction is closely associated with several kidney diseases, including DN.12,13 Like many other cell types, MC function is controlled by intracellular Ca2+ signals.11,14 In this regard, store–operated Ca2+ channel (SOC) plays a pivotal role in many physiologic processes in MCs.14 SOC is activated on depletion of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in response to activation of G protein–coupled receptors.15 Two proteins, STIM116,17 and Orai1,18–20 have been identified as required components of the SOC pathway. STIM1 is located in the ER membrane and functions as an ER Ca2+ sensor, whereas Orai1 is located in the plasma membrane and functions as a Ca2+ channel.21,22 Over the past decades, we and others have shown that SOC mediates MC Ca2+ responses to a variety of circulating and locally produced hormones.23–27 We have also shown that STIM1 was required for activation of SOC in human MCs.28 Recently, we found that the SOC pathway was enhanced in human MCs with prolonged high glucose treatment.29 However, the role of SOC in MCs in the development of DN is completely unknown. In this study, we used both in vitro and in vivo systems and tested a hypothesis that SOC in MCs regulated ECM protein expression.

Results

SOC Suppressed ECM Protein and mRNA Expression in Human MCs

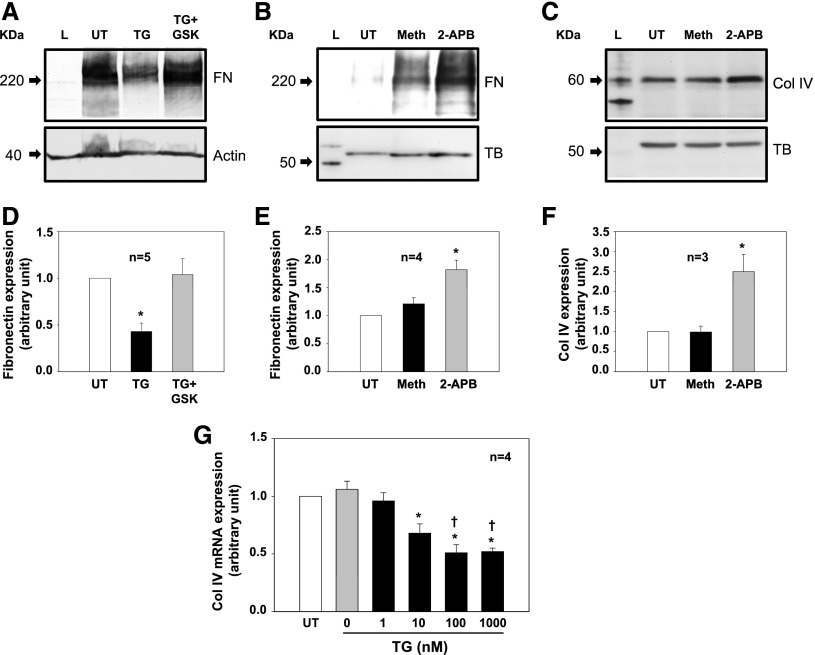

Treatment of cultured human MCs with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG), a classic and widely used activator of SOC,15 for 2 days significantly reduced fibronectin protein expression (Figure 1, A and D). This inhibitory effect was abolished by GSK-7975A, a selective SOC inhibitor.30–33 Consistently, inhibition of SOC with 50 μM 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB) but not its vehicle control (methanol) significantly increased fibronectin protein expression (Figure 1, B and E). The 2-APB response was also observed for Col IV, another matrix protein (Figure 1, C and F). Furthermore, activation of SOC by TG reduced expression of Col IV mRNA in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1G). These data suggest that SOC negatively regulates ECM expression at both mRNA and protein levels in MCs.

Figure 1.

SOC suppressed ECM protein and mRNA expression in cultured human MCs. (A–C) Representative Western blots showing (A) activation of SOC on fibronectin (FN), (B) inhibition of SOC on FN, and (C) inhibition of SOC on Col IV expressions. TG was 1 μM. GSK, GSK-7975A (10 μM); Meth, methanol (vehicle control for 2-APB; 50 μM); TB, tubulin; UT, untreated cell. Both actin and TB were used as a loading control. Serum-starved cells (in 0.5% FBS) were with or without treatments for 2 days before harvested. (D–F) Summary data corresponding to experiments presented in A–C, respectively. *P<0.05 compared with the other two groups. (G) Quantitative real–time RT-PCR showing effects of different doses of TG on Col IV mRNA expression. Cells were treated with TG for 24 hours in 0.5% FBS medium (0 represents DMSO control). Expression levels of Col IV mRNA at different doses of TG treatment were normalized to those in MCs without treatment (UT). *P<0.05 compared with UT and TG at 0 and 1 nM groups; †P<0.05 compared with TG at the 10 nM group.

Overexpression of STIM1 Decreased but Knockdown of Orai1 Increased Fibronectin Expression in Human MCs

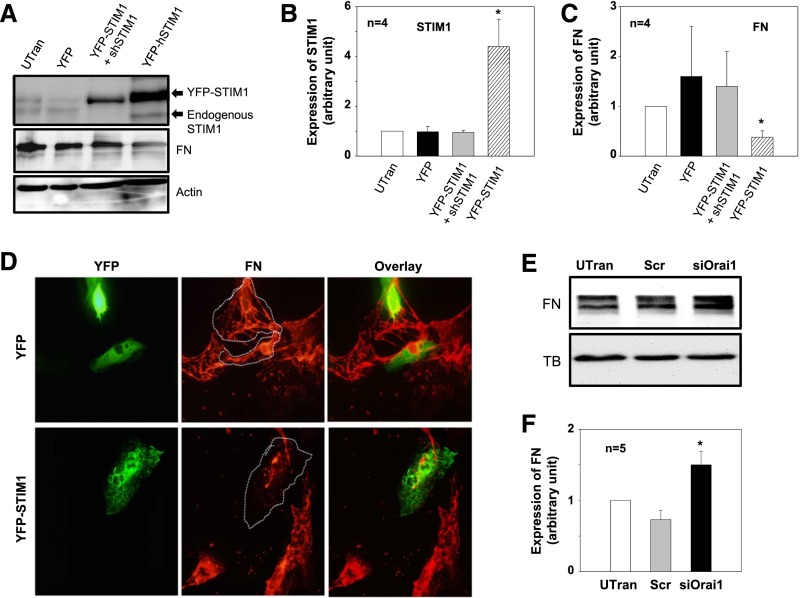

STIM1 is an ER membrane protein that gates SOC by interacting with the channel protein, Orai1.16,17,21,22 We expressed STIM1 in MCs by transfecting the cells with YFP-tagged human STIM1 expression plasmid (pDS_XB_YFP-STIM1-II).17 As shown by the data in Figure 2, with increased STIM1 expression (YFP-STIM1), fibronectin was correspondingly decreased. Cotransfection of the expression plasmid with an shRNA construct against human STIM1 (YFP-STIM1+shSTIM1) not only reversed a high expression of STIM1 but prevented a decrease in fibronectin protein expression as well. Consistent with the Western blot data, immunofluorescence staining showed that fibronectin signals were reduced in MCs transfected with YFP-STIM1 compared with YFP (alone)-transfected MCs (control). Importantly, the fibronectin signals were also much weaker than those in the neighboring negatively transfected cells (Figure 2D). Furthermore, knocking down Orai1, the pore-forming subunit of SOC, using previously characterized synthetic siRNA29 significantly increased fibronectin expression (Figure 2, E and F). These data further support an inhibitory effect of SOC on ECM protein expression.

Figure 2.

Expression of STIM1 decreased and knockdown of Orai1 increased fibronectin (FN) expression in human MCs. (A) Representative Western blot showing FN expression in human MCs without transfection (UTran) and cells transfected with YFP construct or YFP–tagged human STIM1 expression plasmid (YFP-STIM1) or cotransfected with YFP-STIM1 with shRNA against human STIM1 (YFP-STIM1+shRNA). Actin was used as a loading control. (B and C) Summary data from the experiments presented in A showing (B) STIM1 and (C) FN expression levels in MCs with different treatments by normalized to actin. *P<0.05 compared with all other groups. (D) Immunofluorescence staining showing fibronectin expression (red signals) in human MCs transfected with either YFP (green signals in upper panels) or YFP–tagged STIM1 expression plasmid (YFP-STIM1; green signals in lower panels). The YFP- or YFP-STIM1–transfected cells are outlined with dashed lines. Experiments were performed 2 days after transfection. Images were representative of at least three independent experiments. Original magnification ×200. (E) Representative Western blot showing FN expression in human MCs UTran and the cells transfected with scramble control siRNA (Scr) or siRNA against human Orai1 (siOrai1). α-Tubulin (TB) was used as a loading control. (F) Summary data from the experiments presented in E. FN expression level in each group was normalized to TB, and the values in each group were further normalized to the those of the UTran group. *P<0.05 compared with both the UTran and the Scr groups.

SOC Limited Ang II–Induced Fibronectin Expression in Human MCs

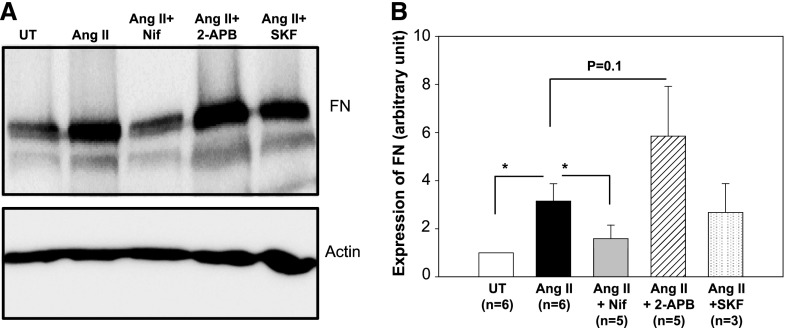

Ang II is a fibrotic factor that stimulates ECM protein production in DN.5,34–38 Ang II signaling in MCs involves several types of Ca2+-conductive channels. These include voltage–operated Ca2+ channel (VOC), receptor–operated Ca2+ channel (ROC), and SOC.11,14,24,29,39–41 We then examined effects of different channel blockers on Ang II–induced fibronectin expression in human MCs. As shown by the data in Figure 3, Ang II treatment (100 nM for 2 days) markedly increased fibronectin expression level. This response was significantly attenuated by nifedipine (1 μM), a selective inhibitor of VOC, but was not affected by SKF96365 (10 μM), an inhibitor to ROC/TRPC channels. Importantly, 2-APB (50 μM) that selectively inhibits SOC at a concentration >10 μM15,42,43 potentiated the Ang II effect, although it did not reach statistical significance. These data suggest that Ang II–activated Ca2+ channels function distinctly in regulation of ECM protein expression. VOC mediates Ang II–stimulated fibronectin expression, whereas SOC may attenuate its fibrotic response.

Figure 3.

SOC suppressed Ang II–induced fibronectin (FN) expression in human MCs. (A) Representative Western blot showing FN expression in human MCs without treatment (UT) or treated with Ang II (100 nM), Ang II plus nifedipine (1 μM; Ang II+Nif), Ang II plus 2-APB (30 μM; Ang II+2-APB), or Ang II plus SKF96365 (10 μM; Ang II+SKF). Actin was used as a loading control. MCs were with and without various treatments for 2 days in 0.5% FBS medium. (B) Summary data from the experiments presented in A. FN expression levels were normalized to actin. *P<0.05 compared with the group as indicated (paired t test).

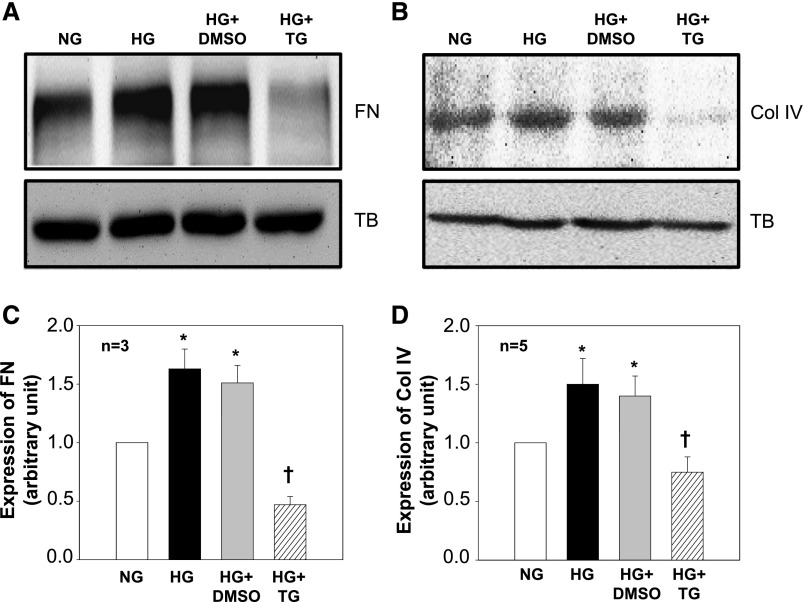

Activation of SOC Inhibited High Glucose–Induced ECM Protein Expression in MCs

High glucose is a pathogenic stimulator for ECM expression in MCs during the progress of DN.5,9,44–47 We examined if activation of SOC could inhibit high glucose–induced fibrotic response. As shown in Figure 4, high glucose treatment significantly increased expression levels of both fibronectin and Col IV proteins. The high glucose responses were significantly abolished by TG but not by its vehicle. Furthermore, TG treatment reduced fibronectin and Col IV expression to a level lower than that in untreated MCs (NG in Figure 4), although it did not reach a statistically significant level. These data suggest a beneficial role of SOC in diabetic kidney.

Figure 4.

SOC inhibited high glucose (HG)-stimulated ECM protein expression in human MCs. (A and B) Representative Western blots showing (A) fibronectin (FN) and (B) Col IV expression in MCs cultured in normal glucose (NG, 5.6 mM glucose+20 mM mannitol) or HG (25 mM glucose) in the absence or presence of DMSO (1:1000; vehicle control) and TG (1 μM). Tubulin (TB) was used as a loading control. MCs were with and without various treatments for (A) 2 or (B) 3 days in 0.5% FBS medium. (C and D) Summary data from the experiments presented in A and B, respectively. FN and Col IV expression levels were normalized to tubulin. *P<0.05 compared with NG group; †P<0.05 compared with both HG and HG+DMSO groups.

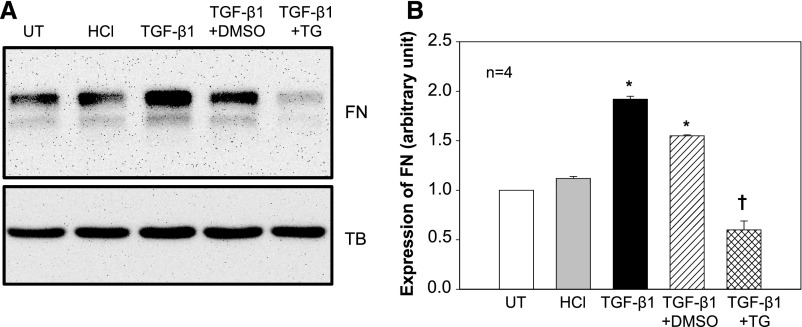

Activation of SOC Inhibited TGF-β1–Stimulated Fibronectin Expression in MCs

It has been firmly established that TGF-β signaling plays the most crucial role in glomerular matrix accumulation in DN.5,47 We next studied if SOC regulated the TGF-β1 pathway, As expected, TGF-β1 but not its vehicle control (HCl) dramatically increased fibronectin protein expression. Activation of SOC by TG significantly abolished the TGF-β1 response (Figure 5). These data indicate that suppression of TGF-β1 signaling may be one mechanism for the antifibrotic effect of SOC.

Figure 5.

Activation of SOC inhibited TGF-β1–stimulated fibronectin (FN) protein expression in human MCs. (A) Representative Western blots showing FN expression in MCs without treatment (UT) or treated with HCl (4 mM; vehicle control for TGF-β1) or TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) in the presence of DMSO (1:1000; vehicle control of TG) or TG (1 μM). All treatments were 15 hour with 0.5% FBS medium. Tubulin (TB) served as a loading control. (B) Summary data from the experiments presented in A. FN expression level was normalized to tubulin. *P<0.05 compared with both UT and HCl groups; †P<0.05 compared with both TGF-β1 and TGF-β1+DMSO groups.

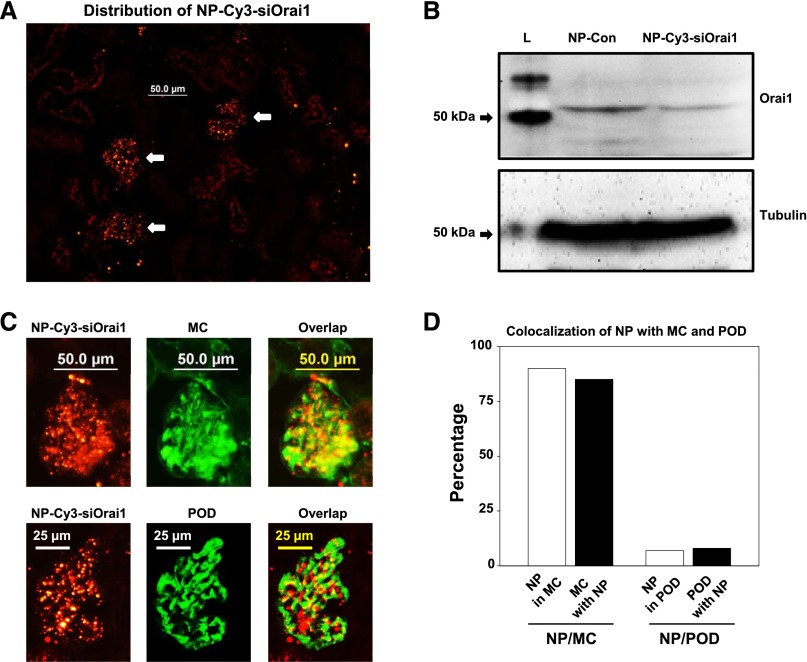

In Vivo Knockdown of Orai1 in MCs Increased ECM Protein Expression in Renal Cortex and Glomerulus and Induced Mesangial Expansion in Mice

Orai1 is the pore-forming unit of SOC.21,22 We speculated that we could inhibit SOC function in MCs in vivo by delivery of siRNAs against Orai1 to intact animals. We have previously shown specific delivery of approximately 75 nm PEGylated gold nanoparticles (NPs) into MCs in mouse kidney.48 We have also previously shown that approximately 75 nm cyclodextrin–containing polycation (CDP) –containing NPs carrying siRNA (siRNA-CDP-NPs) accumulate in the glomerulus49 and that these siRNA-CDP-NPs can be used for the selective delivery of functional siRNA to mouse MC in vivo.50 In this study, we formulated the siRNA-CDP-NPs with Cy3-tagged siRNA against mouse Orai1 (NP-Cy3-siOrai1) and injected these siRNA-CDP-NPs into mice through the tail vein. Consistent with our previous reports,48 the siRNA-CDP-NP complexes were accumulated in glomeruli, with scarce distribution in other regions (Figure 6A). Western blot of renal cortex extracts verified the efficiency of knocking down Orai1 (Figure 6B). To confirm delivery of siRNA-CDP-NPs to the MCs, we counterstained kidney sections from mice that received Cy3-siRNA containing NP with the MC marker thymic antigen 1 using the OX-7 antibody and the podocyte marker synaptopodin protein using antisynaptopodin antibody. We found persistent Cy3-siRNA fluorescent signal after administration of the siRNA-CDP-NPs that highly colocalized with the OX-7 but not synaptopodin antibody staining (Figure 6C). Semiquantitative colocalization analysis revealed 85% OX-7 staining colocalization with Cy3 fluorescence and 90% colocalization of Cy3-siRNA fluorescence with OX-7 staining (Figure 6D). However, both values of colocalization of Cy3-siRNA fluorescence with synaptopodin staining were minimal (Figure 6D). These data show that siRNA-CDP-NPs were predominantly deposited in glomerular MCs.

Figure 6.

NP-Cy3-siOrai1 was predominantly localized in MCs in mouse kidney. (A) Representative images from three mice showing localization of NP-Cy3-siOrai1 (red) in glomeruli (indicated by arrows) but not in tubules. Original magnification ×200. (B) Representative Western blot of renal cortex extracts from three independent experiments showing Orai1 expression in the mouse with injection of NP control (NP-Con) and NP-Cy3-siOrai1. Although the predicted size of Orai1 is approximately 33 kD, the antibody actually detects a band at approximately 50 kD. L, protein ladder; tubulin, loading control. (C) Localization of NP-Cy3-siOrai1 in MCs (upper panels) and podocytes (POD; lower panels) representative of three mice. MCs were stained with OX-7 (green), and podocytes were stained with synaptopodin (green). NP-Cy3-siOrai1 was shown as red signals. Original magnification ×200. (D) Semiquantification of the colocalizations of MC and podocyte markers with NP-Cy3-simOrai1 shown in C using BioimageXD software.

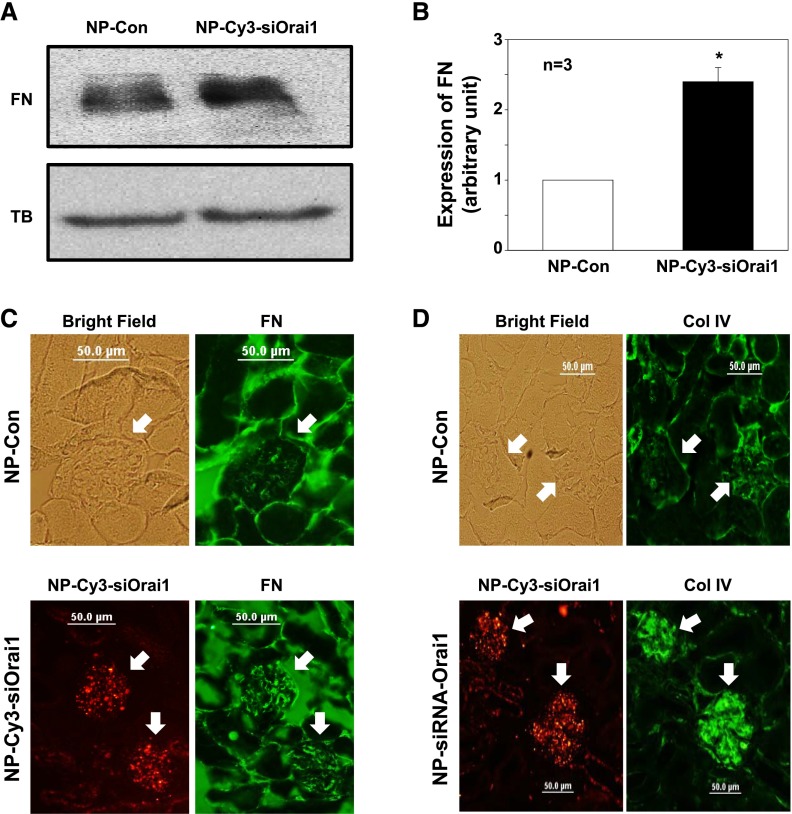

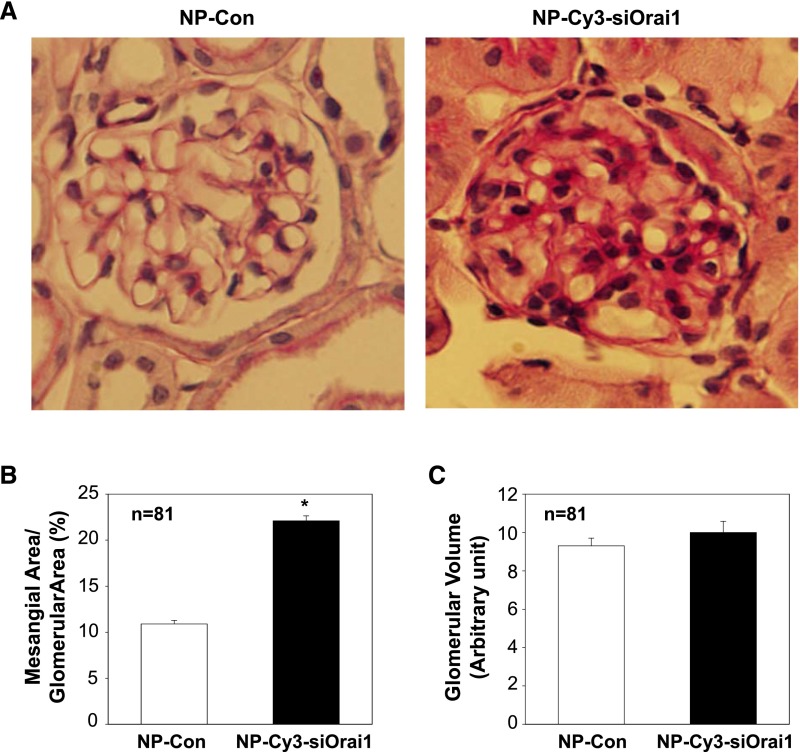

We then conducted Western blot and found that abundance of fibronectin protein in the renal cortex was significantly increased in the mice treated with siRNA-CDP-NPs carrying Cy3-siOrai1 (Figure 7, A and B). Consistently, additional immunohistochemical examinations showed remarkable increases in both fibronectin and Col IV staining in the glomeruli of mice receiving siRNA-CDP-NPs (Figure 7, C and D). In agreement with those changes, the mice treated with siRNA-CDP-NPs carrying Cy3-siOrai1 showed significant expansion of mesangium (Figure 8, A and B). However, glomerular volume in Orai1–knocked down mice only had the tendency to increase but no statistical significance.

Figure 7.

In vivo knockdown of Orai1 in MCs increased glomerular ECM protein expression in mice. (A and B) Western blot of renal cortex extracts showing expressions of fibronectin (FN) protein in the cortex of kidney from the mice treated with control NP (NP-Con) and NP-Cy3-siOrai1 (knockdown of Orai1). TB, α-tubulin (a loading control). (A) Representative blot. (B) Summary data. *P<0.05 compared with NP-Con. (C and D) Immunohistochemistry showing expressions of (C) FN and (D) Col IV in the glomeruli of the mice treated with NP-Con and NP-Cys-siOrai1. Both FN and Col IV are shown as green staining. In NP-Con, a bright-field image was captured to show the glomerulus. In NP-Cy3-siOrai1, the distribution of NP-Cy3-siOrai1 is indicated by Cy3 signals (red). Arrows indicate glomeruli. Original magnification ×200.

Figure 8.

In vivo knockdown of Orai1 in MCs induced mesangial expansion in mice. (A) Representative periodic acid–Schiff staining showing mesangial matrix expansion in the glomeruli from mice treated with NP alone (NP-Con) or NP-siRNA-Orai1 (NP-Cy3-siOrai1). Original magnification ×200. (B and C) Summary data from 81 glomeruli (n=81) from five to seven sections per kidney per mouse of five mice showing glomerular mesangial area and glomerular volume. *P<0.05.

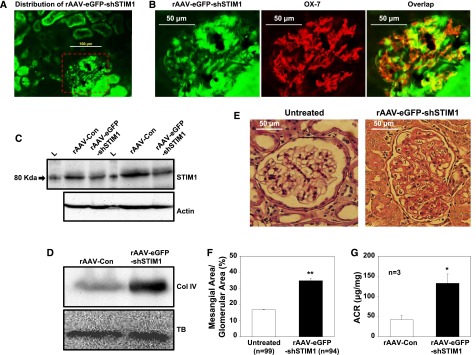

In Vivo Knockdown of STIM1 in MCs Increased Col IV Protein Expression in Renal Cortex and Induced Mesangial Expansion in Rats

The inhibition of SOC on mesangial matrix expression in intact animals was further examined in rats. We chose recombinant adeno–associated virus (rAAV) to deliver shRNA against rat STIM1 to rat kidney, because the in vivo rAAV/shRNA delivery system has been well developed in rats.51–54 The rAAV–carried eGFP–tagged shRNA against rat STIM1 (rAAV-eGFP-shStim1) was administered to rats by tail vein injection. An rAAV1/2 encoding an eGFP–tagged scrambled shRNA served as a control. Rats were euthanized 8 weeks after injection. Although the rAAV-eGFP-shRNA was distributed in both glomerulus and tubule regions (Figure 9A), there was good colocalization of rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 signals with OX-7 staining (Figure 9B), suggesting that MCs had good infection with the virus. Western blot verified a reduction of STIM1 protein in the renal cortex from the rats treated with rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 (Figure 9C). Corresponding to a low expression of STIM1 protein, Col IV expression level was dramatically increased in the renal cortex of the rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 rats compared with rAAV-Con rats (Figure 9D). Like the mice with knockdown of Orai1, the rats with knockdown of STIM1 showed significant mesangial expansion (Figure 9, E and F). In addition, the rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 rats manifested tubular hypertrophy, probably because of knockdown of STIM1 in tubular epithelial cells. Furthermore, the rats receiving rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 had a significantly greater urinary albumin excretion rate, an indication of renal injury (Figure 9G). In summary, these data from rats suggest a renoprotective effect of the endogenous SOC in the kidney.

Figure 9.

In vivo knockdown of STIM1 in MCs increased ECM protein expression in renal cortex and induced mesangial expansion in rats. STIM1 was knocked down using shRNA against rat STIM1 (shSTIM1). The shSTIM1 construct was tagged with eGFP and packaged into rAAV (rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1). Rats were euthanized 8 weeks after injection of rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 and control rAAV (rAAV-Con). (A) Distribution of rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 (green signals) in rat kidney representative of three rats. Kidney was fixed with 4% PFA. Original magnification ×200. (B) Enlarged images from the red-dashed box in A showing localization of rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 in MCs. MCs were stained with OX-7 (red); rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 is shown as green signals. Original magnification ×200. (C) Western blot of fresh renal cortex extracts from the rats with injection of rAAV-Con and rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1. The blots represents two repeats from the same samples. Actin is a loading control. L, protein ladder. (D) Western blot of fresh renal cortex extracts showing Col IV expression in renal cortex of the rats treated with rAAV-Con and rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1. The blot is representative of three independent experiments (three rats). TB, tubulin (a loading control). (E) Representative periodic acid–Schiff staining of kidney sections from a rat without administration of rAAV (untreated) and a rat treated with rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1. The rat with administration of rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 showed marked mesangial expansion and tubular hypertrophy. Original magnification ×200. (F) Summary data. The numbers of glomeruli from five to seven sections per kidney per rat from three untreated rats and two rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1–treated rats are indicated. **P<0.01 (untreated versus rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1). (G) Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) in rAAV-Con and rAAV-eGFP-shSTIM1 rats (8 weeks after injection). *P<0.05.

Discussion

Diabetes is the leading cause of ESRD worldwide. The early changes in diabetic kidney include accumulation of ECM proteins in the glomerulus, which ultimately progresses to glomeruloscleorosis and irreversible ESRD. There is no curative therapy currently available for DN. Despite the increased use of antihypertensive medications and rennin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors in patients with DN, the improvement of renal function is slight.55 Therefore, new therapeutic approaches are needed. This study provides in vitro and in vivo evidence that SOC in MCs inhibits glomerular matrix protein expression. Thus, SOC in MCs could be a protective mechanism in diabetic kidneys. Theoretically, selective enhancement of the renoprotective SOC function and any component in its signaling pathway would be expected to ameliorate renal damage in diabetes and limit the development of DN.

Our previous study showed that the abundance of STIM1/Orai1 proteins (essential components of SOC pathway) was increased in the glomerulus by diabetes and MCs by high glucose.29 This paradoxical phenomenon suggests that, in addition to well known deleterious processes, diabetes simultaneously activates a beneficial SOC pathway in MCs as a compensatory mechanism to counteract detrimental pathways generated in diabetic kidneys. For instance, the Ang II system is significantly enhanced and contributes to mesangial expansion and glomerular fibrosis through fibrogenic mechanisms in diabetic kidney.35–37 However, Ang II can activate Gq–coupled receptor signaling and thus, activates the matrix-inhibitory SOC.39,56,57 Conceivably, if SOC is suppressed, the Ang II–induced matrix protein expression would be augmented because of loss of an antagonistic action from SOC. The dual effects of Ang II in diabetic kidney may explain the modest effect of RAS inhibitors on delaying progression of DN, because the inhibitors suppress both detrimental and beneficial effects of Ang II and thereby, compromise their therapeutic efficiency.

SOC function is distinct in different tissues and cell types.15,58 In general, the SOC–associated signaling pathway promotes protein synthesis and cell growth,15 for instance, contributing to cardiac hypertrophy.51,59 However, a recent study revealed that the SOC–mediated Ca2+ influx suppressed cell growth in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and rat uterine leiomyoma cells through inhibition of AKT1.60 Thus, the effect of SOC on protein production might be cell type specific and/or cell context dependent. Our data suggest that SOC–mediated Ca2+ signaling in glomerular MCs negatively regulates ECM protein expression. A similar example is the regulation of protein secretion by Ca2+ in juxtaglomerular (JG) cells. Like MCs, JG cells are modified smooth muscle cells that synthesize, store, and release renin into the blood stream for initiating the RAS system. Usually, Ca2+ signal through SOC stimulates protein secretion in granular cells.15 In contrast, activation of SOC in JG cells inhibits renin secretion.61

MCs express several type of Ca2+-conductive channels.14 Our study suggests that inhibition of ECM protein expression is SOC specific, because blockade of VOC and ROC significantly attenuated and did not affect the Ang II–induced matrix protein expression in cultured MCs, respectively. Previous studies by us and others showed that VOC and ROC can regulate contractile function of MCs.14,40,62,63 Differential functions of distinct Ca2+ channels in the same cell might be caused by channel type–specific downstream pathways. For instance, in MCs, the intermediators that regulate ECM protein expression may be functionally linked or physically adjacent to SOC. Thus, the local Ca2+ signals delimited to the SOC–associated Ca2+ microdomains can be sensed by these molecules and subsequently, inhibit ECM protein expression.

Although the mechanism for SOC inhibiting ECM protein expression in MCs is not fully elucidated in this study, inhibition on TGF-β1 signaling might be involved. However, in addition to the TGF-β1/Smad pathway,3,4,47,64–67 many molecules and multiple pathways, such as Ang II,35–37 reactive oxygen species,3,9,68 mitogen–activated protein kinase,3,47,69 and protein kinase C,3,47,70 are involved in accumulation of ECM in DN. It is possible that the SOC–mediated Ca2+ signals modulate one or more of those pathways, leading to suppression of ECM expression.

Here, we used the siRNA-CDP-NP delivery system and an rAAV delivery system to introduce RNAi sequences into MCs in mice and rats, respectively. This approach is built on the anatomic properties of glomerular capillary. The glomerular capillary walls have 70–100 nm endothelial fenestrations. The surrounded glomerular basement membrane generates a size-selective barrier with a pore size of 4 nm. MCs directly adjoin the endothelium without intervening the basement membrane.7,71 Thus, particles in the size of 4–100 nm can permeate through the fenestrated glomerular capillary wall and yet, be restricted in passing through the glomerular basement membrane, and therefore, they come into the mesangial region under a high transmural pressure gradient. Shimizu et al.71 have successfully delivered nanocarriers containing siRNA in the 10- to 20-nm-size range to MCs in animals. We used a similar approach using approximately 75 nm siRNA-CDP-NPs that have been shown to accumulate within the glomeruli of mice.49 In agreement with those studies, the siRNA-CDP-NPs in this study were predominantly localized in MCs, with very limited distribution in the extraglomerular region and glomerular podocytes. Both mouse and human MCs could rapidly internalize the siRNA-NPs in vitro (data not shown). Therefore, the decrease in Orai1 protein expression in renal cortex was most likely caused by knockdown of Orai1 in MCs. We further reason that the increases in fibronectin and Col IV expression in renal cortex and glomerulus and glomerular mesangial expansion were attributed to reduced Orai1 protein (i.e., inhibition of SOC) in MCs.

One advantage of rAAV vectors is that they can efficiently transfer genes of interest to a target tissue or organ, leading to high levels of stable and long-term expression after a single application.72–76 Although our viral particles were in a size of approximately 20 nm, the rAAV/shRNA complex was not as selective to MCs as siRNA-CDP-NPs. In addition to MCs, renal tubules and other glomerular cell types were also infected by the virus. Hence, the increase in Col IV expression, mesangial expansion, and renal injury (increase in albumin-to-creatinine ratio) in the rAAV/shSTIM1-treated rats might be partially attributed to a decreased STIM1 protein (i.e., inhibition of SOC) in MCs. Whether and how much a reduction of STIM1 in other type of cells contributed to the increase in glomerular matrix are unclear in this study.

In summary, this study strongly suggests a beneficial effect of SOC in MCs by inhibiting ECM protein expression, which may protect the kidney from diabetic injury at early stages of DN. Thus, SOC could be a promising therapeutic option to limit progress of DN. Furthermore, MCs do not have a cell type–specific promoter, and thereby, it is impossible to genetically manipulate an MC–specific gene expression. We have shown in this study that the nanocarriers of a particular size can be used as MC–specific siRNA delivery systems by systemic injection. Because the siRNA-CDP-NPs system has been used as a research tool as well as a human therapeutic48,71,77,78 and because MC injury is associated with many renal diseases,7,10 systemic administration of MC-selective siRNA-CDP-NPs targeting a particular protein may have a potential for the treatment of renal diseases.

Concise Methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In total, 9 male Sprague–Dawley rats and 10 male C57BL/6 mice were used in this study. All rats and mice were between 2 and 4 months of age. Rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN), and mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All animals were maintained at the animal facility of UNTHSC under local and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

In Vivo Delivery of NPs into the Kidney of Mice

The targeted NP delivery system was used to deliver siRNA against Orai1 to the kidneys of mice. Mice were randomly divided into control and Orai1–knocked down groups (five mice in each group). The mice in the Orai1–knocked down group were given NPs containing Cy3-tagged siRNA against mouse Orai1 (NP-Cy3-siOrai1) by tail vein injection at a dose of 10 mg/kg siRNA in an approximately 100-μl injection volume. The mice in the control group were only given NPs through the same route in the same injection volume. Mice in both groups received the intravenous injections on days 1 and 3 of the experiment and were euthanized on day 5 for kidney harvesting.

In Vivo Delivery of rAAVs into the Kidney of Rats

rAAVs of serotype 1/2 (rAVE; GeneDetect, Sarasota, FL) were used to deliver shRNA constructs to rat kidneys. Rats were randomly divided into control and STIM1–knocked down groups (three rats each group). The rats in STIM1–knocked down group were injected with rAAV1/2 encoding eGFP-tagged shRNA against rat STIM1 (rAAV-eGFP-shStim1) through the tail vein at 1.5×1010 genomic particles in approximately 0.3 mL. The target gene sequence of the shRNA was published in ref. 79. In the control group, rats were injected with rAAV1/2 encoding an eGFP–tagged scrambled shRNA at the same concentration of virus in the same injection volume. Rats were euthanized 8 weeks after injection for kidney harvesting. In Figure 9, E and F, three rats without virus treatment were used as controls.

siRNA-CDP-NP Formulation

siRNA NPs were formed by using CDP and adamantine-polyethylene glycol as previously described (precomplexation).80 NPs were formed in 5% glucose in deionized water (D5W) at a charge ratio of 3± and an siRNA concentration of 2 mg/ml. The Cy3–labeled siRNA oligos targeting mouse Orai1 were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Chicago, IL). The sense strand sequence is 5′-/5Cy3/GGGUUGCUCAUCGUCUUUAGUGC-3′.

Immunofluorescence Histochemistry

Rats and mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg body wt) at indicated time points. After washing out blood with PBS, the left kidneys were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight. Formalin-fixed organs were dehydrated and embedded in molten paraffin to generate sections of 4 μm in thickness (Cryostat 2800 Frigocut-E; Leica Instruments). Anti–OX-7 mouse mAb at 1:100 and Alexa Fluor 488 (for mice) or 568 (for rats) goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) at 1:2000 were used to label glomerular MCs. Sections were examined using an Olympus microscope (BX41) equipped for epifluorescence and an Olympus DP70 digital camera with DP manager software (version 2.2.1). Images were converted to 16-bit format and uniformly adjusted for brightness and contrast using ImageJ (version 1.47; NIH). Semiquantification of colocalizations of NP-Cy3-siOrai1 with the MC or podocyte marker (Figure 6D) was examined using BioimageXD software.

Assessment of Mesangial Area and Glomerular Volume

Four-micrometer paraffin–embedded kidney sections were stained with periodic acid–Schiff (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Images were captured using an Olympus DP70 digital camera with DP manager software (version 2.2.1) and traced using ImageJ software (version 1.47; NIH). Glomerular area was measured by tracing around the perimeter of the glomerular tuft. Mesangial area was defined as the periodic acid–Schiff-positive and nuclei-free area in the mesangium and expressed as a ratio to a total glomerular area. Glomerular volume was estimated using the formula V=(4A/3)(A/π)1/2, where A is area, and V is volume.

Extraction of Renal Cortical Proteins

Right kidneys were removed from rats or mice immediately after euthanasia. Renal cortex was separated from the other region of the kidney using a sharp blade, and the cortical tissue was minced using two sharp blades. The cortical tissues were sonicated in a lysis buffer followed by centrifugation at 20,817×g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were collected for Western blot.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human MCs were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). Cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 25 mM Hepes, 4 mM glutamine, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 20% FBS. Cells <10 generations were used in this study.

All transfections in this study were transient transfections using LipofectAmine and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen-BRL, Carlsbad, CA) following the protocols provided by the manufacturer. Experiments were conducted approximately 48 hours after transfection.

Immunofluorescence Cytochemistry

Human MCs were transfected with either YFP alone or YFP–tagged STIM1 expression plasmid. Immunofluorescence staining was performed 2 days after transfection using the protocol described in our previous publication.81 The cells were incubated with fibronectin primary antibody at 1:50 in PBS plus 10% donkey serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 at 4°C overnight. The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 1:500 for 1 hour at room temperature. Fluorescent staining was examined using an Olympus microscope (BX41) equipped for epifluorescence and an Olympus DP70 digital camera with DP manager software (version 2.2.1). Images were converted to 16-bit format and uniformly adjusted for brightness and contrast using ImageJ (version 1.47; NIH).

Western Blots

Whole-cell lysates or renal cortical extracts were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with primary fibronectin, Col IV, β-actin, α-tubulin, STIM1, and Orai1 antibodies. Bound antibodies were visualized with Super Signal West Pico or Femto Luminol/Enhancer Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The specific protein bands were visualized and captured using an AlphaEase FC Imaging System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). The integrated density value of each band was measured by drawing a rectangle outlining the band using AlphaEase FC software with autobackground subtraction. The expression levels of targeted proteins were quantified by normalization of the integrated density values of those protein bands to that of the actin or tubulin band on the same blot.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

As described in our previous publication,29 briefly, the total RNA was isolated from cultured human MCs using a PerfectPure RNA Cultured Cell Kit (5 Prime, Inc., Hamburg, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Human Col IV primers (forward: CAGCCAGACCATTCAGATCC; reverse: TGGCGCACTTCTAAACTCCT) and β-actin primers (forward: ACTGTGTGGATTACATGGGCCAGA; reverse: AGGATTGCCTCCACAATCCGTACA) were synthesized by IDT (Coralville, IA). The Col IV levels were normalized by β-actin mRNA. Quantification was calculated as follows: mRNA levels =2ΔCt, where ΔCt=Ct,Col IV−Ct,actin.

Materials

TG, nifedipine, SKF96365, 2-APB, rabbit polyclonal antifibronectin, β-actin and α-tubulin antibodies, methanol, and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. GSK-7975A was kindly donated by GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, UK). GOK/STIM1 mouse mAb was purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Anti-Orai1 and anti-CD90/thymic antigen 1 (MRC OX-7) antibodies were purchased from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Mouse anti-Col IV mAb was purchased from Meridian Life Science, Inc. (Memphis, TN). YFP-STIM expression plasmid (pDS_XB_YFP-STIM1-II) was a gift from Tobias Meyer (Stanford University School of Medicine Stanford, CA). This plasmid was originally characterized in ref. 17. The shRNA construct that targets on human STIM1 (shSTIM1) was generated in our laboratory using GeneClip U1 Hairpin Cloning System-hMGFP (Promega). This construct has been used in our previous study.28

Statistical Analyses

Data were reported as means±SEMs. The one-way ANOVA plus Newman–Keuls post hoc analysis and unpaired t test were used to analyze the differences among multiple groups and between two groups, respectively, unless indicated in individual figures. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank GlaxoSmithKline for providing GSK-7975A compound and Dr. Tobias Meyer at Stanford University School of Medicine for providing YFP-STIM expression plasmid (pDS_XB_YFP-STIM1-II).

The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81400805 (to P.W.) and National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-DK079968 (to R.M.) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Townsend RR, Feldman HI: Chronic kidney disease progression. Nephrol Self Assess Program 8: 271–288, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend RR, Feldman HI: Chronic kidney disease: Past problems, current challenges, and future facets. Nephrol Self Assess Program 8: 239–243, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanwar YS, Akagi S, Sun L, Nayak B, Xie P, Wada J, Chugh SS, Danesh FR: Cell biology of diabetic kidney disease. Nephron Exp Nephrol 101: e100–e110, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziyadeh FN, Sharma K: Role of transforming growth factor-β in diabetic glomerulosclerosis and renal hypertrophy. Kidney Int Suppl 51: S34–S36, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, Xie P, Wallner EI, Chen S, Chugh S, Danesh FR: Diabetic nephropathy: Mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 4–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonson MS: Phenotypic transitions and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 71: 846–854, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlöndorff D, Banas B: The mesangial cell revisited: No cell is an island. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1179–1187, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooch JL, Barnes JL, Garcia S, Abboud HE: Calcineurin is activated in diabetes and is required for glomerular hypertrophy and ECM accumulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F144–F154, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorin Y, Block K, Hernandez J, Bhandari B, Wagner B, Barnes JL, Abboud HE: Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase mediates hypertrophy and fibronectin expression in the diabetic kidney. J Biol Chem 280: 39616–39626, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abboud HE: Mesangial cell biology. Exp Cell Res 318: 979–985, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stockand JD, Sansom SC: Glomerular mesangial cells: Electrophysiology and regulation of contraction. Physiol Rev 78: 723–744, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashgarian M, Sterzel RB: The pathobiology of the mesangium. Kidney Int 41: 524–529, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scindia YM, Deshmukh US, Bagavant H: Mesangial pathology in glomerular disease: Targets for therapeutic intervention. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 62: 1337–1343, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma R, Pluznick JL, Sansom SC: Ion channels in mesangial cells: Function, malfunction, or fiction. Physiology (Bethesda) 20: 102–111, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parekh AB, Putney JW, Jr.: Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85: 757–810, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Veliçelebi G, Stauderman KA: STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169: 435–445, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr., Meyer T: STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 15: 1235–1241, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A: A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441: 179–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP: CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312: 1220–1223, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XHF, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD: Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 9357–9362, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng X, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Soboloff J, Gill DL: STIM and Orai: Dynamic intermembrane coupling to control cellular calcium signals. J Biol Chem 284: 22501–22505, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Deng X, Gill DL: Calcium signaling by STIM and Orai: Intimate coupling details revealed. Sci Signal 3: pe42, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campos AH, Calixto JB, Schor N: Bradykinin induces a calcium-store- dependent calcium influx in mouse mesangial cells. Nephron 91: 308–315, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menè P, Teti A, Pugliese F, Cinotti GA: Calcium release-activated calcium influx in cultured human mesangial cells. Kidney Int 46: 122–128, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutt LK, O’Neil RG: Effect of elevated glucose on endothelin-induced store-operated and non-store-operated calcium influx in renal mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1225–1235, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma R, Sansom SC: Epidermal growth factor activates store-operated calcium channels in human glomerular mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 47–53, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li WP, Tsiokas L, Sansom SC, Ma R: Epidermal growth factor activates store-operated Ca2+ channels through an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-independent pathway in human glomerular mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 279: 4570–4577, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sours-Brothers S, Ding M, Graham S, Ma R: Interaction between TRPC1/TRPC4 assembly and STIM1 contributes to store-operated Ca2+ entry in mesangial cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 234: 673–682, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhari S, Wu P, Wang Y, Ding Y, Yuan J, Begg M, Ma R: High glucose and diabetes enhanced store-operated Ca(2+) entry and increased expression of its signaling proteins in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1069–F1080, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashmole I, Duffy SM, Leyland ML, Morrison VS, Begg M, Bradding P: CRACM/Orai ion channel expression and function in human lung mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129: 1628–1635, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice LV, Bax HJ, Russell LJ, Barrett VJ, Walton SE, Deakin AM, Thomson SA, Lucas F, Solari R, House D, Begg M: Characterization of selective Calcium-Release Activated Calcium channel blockers in mast cells and T-cells from human, rat, mouse and guinea-pig preparations. Eur J Pharmacol 704: 49–57, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derler I, Schindl R, Fritsch R, Heftberger P, Riedl MC, Begg M, House D, Romanin C: The action of selective CRAC channel blockers is affected by the Orai pore geometry. Cell Calcium 53: 139–151, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerasimenko JV, Gryshchenko O, Ferdek PE, Stapleton E, Hébert TO, Bychkova S, Peng S, Begg M, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH: Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel blockade as a potential tool in antipancreatitis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 13186–13191, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Block K, Ricono JM, Lee DY, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE, Gorin Y: Arachidonic acid-dependent activation of a p22(phox)-based NAD(P)H oxidase mediates angiotensin II-induced mesangial cell protein synthesis and fibronectin expression via Akt/PKB. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1497–1508, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN: The role of angiotensin II in diabetic nephropathy: Emphasis on nonhemodynamic mechanisms. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 153–163, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennefick TM, Anderson S: Role of angiotensin II in diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 17: 441–447, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mima A, Matsubara T, Arai H, Abe H, Nagai K, Kanamori H, Sumi E, Takahashi T, Iehara N, Fukatsu A, Kita T, Doi T: Angiotensin II-dependent Src and Smad1 signaling pathway is crucial for the development of diabetic nephropathy. Lab Invest 86: 927–939, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Block K, Eid A, Griendling KK, Lee DY, Wittrant Y, Gorin Y: Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase mediates Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PDK-1 in response to angiotensin II: Role in mesangial cell hypertrophy and fibronectin expression. J Biol Chem 283: 24061–24076, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans JF, Lee JH, Ragolia L: Ang-II-induced Ca(2+) influx is mediated by the 1/4/5 subgroup of the transient receptor potential proteins in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells from diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol 302: 49–57, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du J, Sours-Brothers S, Coleman R, Ding M, Graham S, Kong DH, Ma R: Canonical transient receptor potential 1 channel is involved in contractile function of glomerular mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1437–1445, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall DA, Carmines PK, Sansom SC: Dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca(2+) channels in human glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F97–F103, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma HT, Venkatachalam K, Parys JB, Gill DL: Modification of store-operated channel coupling and inositol trisphosphate receptor function by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate in DT40 lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 277: 6915–6922, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prakriya M, Lewis RS: Potentiation and inhibition of Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP(3) receptors. J Physiol 536: 3–19, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blaes N, Pécher C, Mehrenberger M, Cellier E, Praddaude F, Chevalier J, Tack I, Couture R, Girolami JP: Bradykinin inhibits high glucose- and growth factor-induced collagen synthesis in mesangial cells through the B2-kinin receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F293–F303, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tahara A, Tsukada J, Tomura Y, Yatsu T, Shibasaki M: Effects of high glucose on AVP-induced hyperplasia, hypertrophy, and type IV collagen synthesis in cultured rat mesangial cells. Endocr Res 37: 216–227, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung DS, Li JJ, Kwak SJ, Lee SH, Park J, Song YS, Yoo TH, Han SH, Lee JE, Kim DK, Moon SJ, Kim YS, Han DS, Kang SW: FR167653 inhibits fibronectin expression and apoptosis in diabetic glomeruli and in high-glucose-stimulated mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F595–F604, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN: Molecular mechanisms of diabetic renal hypertrophy. Kidney Int 56: 393–405, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi CHJ, Zuckerman JE, Webster P, Davis ME: Targeting kidney mesangium by nanoparticles of defined size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 6656–6661, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Han H, Davis ME: Polycation-siRNA nanoparticles can disassemble at the kidney glomerular basement membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 3137–3142, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuckerman JE, Gale A, Wu P, Ma R, Davis ME: siRNA delivery to the glomerular mesangium using polycationic cyclodextrin nanoparticles containing siRNA. Nucleic Acid Ther 2014, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hulot JS, Fauconnier J, Ramanujam D, Chaanine A, Aubart F, Sassi Y, Merkle S, Cazorla O, Ouillé A, Dupuis M, Hadri L, Jeong D, Mühlstedt S, Schmitt J, Braun A, Bénard L, Saliba Y, Laggerbauer B, Nieswandt B, Lacampagne A, Hajjar RJ, Lompré AM, Engelhardt S: Critical role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation 124: 796–805, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao G, Tu L, Li X, Yang S, Chen C, Xu X, Wang P, Wang DW: Delivery of AAV2-CYP2J2 protects remnant kidney in the 5/6-nephrectomized rat via inhibition of apoptosis and fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther 23: 688–699, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vavrincova-Yaghi D, Deelman LE, Goor H, Seelen M, Kema IP, Smit-van Oosten A, Zeeuw D, Henning RH, Sandovici M: Gene therapy with adenovirus-delivered indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase improves renal function and morphology following allogeneic kidney transplantation in rat. J Gene Med 13: 373–381, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghayur A, Liu L, Kolb M, Chawla A, Lambe S, Kapoor A, Margetts PJ: Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of TGF-β1 to the renal glomeruli leads to proteinuria. Am J Pathol 180: 940–951, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pavkov ME, Mason CC, Bennett PH, Curtis JM, Knowler WC, Nelson RG: Change in the distribution of albuminuria according to estimated glomerular filtration rate in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 1845–1850, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saleh SN, Albert AP, Peppiatt CM, Large WA: Angiotensin II activates two cation conductances with distinct TRPC1 and TRPC6 channel properties in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol 577: 479–495, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loutzenhiser K, Loutzenhiser R: Angiotensin II-induced Ca(2+) influx in renal afferent and efferent arterioles: Differing roles of voltage-gated and store-operated Ca(2+) entry. Circ Res 87: 551–557, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nesin V, Wiley G, Kousi M, Ong EC, Lehmann T, Nicholl DJ, Suri M, Shahrizaila N, Katsanis N, Gaffney PM, Wierenga KJ, Tsiokas L: Activating mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 cause overlapping syndromes of tubular myopathy and congenital miosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 4197–4202, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voelkers M, Salz M, Herzog N, Frank D, Dolatabadi N, Frey N, Gude N, Friedrich O, Koch WJ, Katus HA, Sussman MA, Most P: Orai1 and Stim1 regulate normal and hypertrophic growth in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 1329–1334, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peng H, Liu J, Sun Q, Chen R, Wang Y, Duan J, Li C, Li B, Jing Y, Chen X, Mao Q, Xu KF, Walker CL, Li J, Wang J, Zhang H: mTORC1 enhancement of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ entry constrains tuberous sclerosis complex-related tumor development. Oncogene 32: 4702–4711, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schweda F, Riegger GAJ, Kurtz A, Krämer BK: Store-operated calcium influx inhibits renin secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F170–F176, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graham S, Ding M, Sours-Brothers S, Yorio T, Ma JX, Ma R: Downregulation of TRPC6 protein expression by high glucose, a possible mechanism for the impaired Ca2+ signaling in glomerular mesangial cells in diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1381–F1390, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding Y, Stidham RD, Bumeister R, Trevino I, Winters A, Sprouse M, Ding M, Ferguson DA, Meyer CJ, Wigley WC, Ma R: The synthetic triterpenoid, RTA 405, increases the glomerular filtration rate and reduces angiotensin II-induced contraction of glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int 83: 845–854, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Qu X, Yao J, Caruana G, Ricardo SD, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Bertram JF: Blockade of endothelial-mesenchymal transition by a Smad3 inhibitor delays the early development of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 59: 2612–2624, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tu Y, Wu T, Dai A, Pham Y, Chew P, de Haan JB, Wang Y, Toh BH, Zhu H, Cao Z, Cooper ME, Chai Z: Cell division autoantigen 1 enhances signaling and the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-β in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 79: 199–209, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei X, Xia Y, Li F, Tang Y, Nie J, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Hou FF: Kindlin-2 mediates activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling and renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1387–1398, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kretzschmar M, Liu F, Hata A, Doody J, Massagué J: The TGF-beta family mediator Smad1 is phosphorylated directly and activated functionally by the BMP receptor kinase. Genes Dev 11: 984–995, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gorin Y: Nox4 as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of uremic toxicity associated to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 541–543, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Wagner B, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE: Angiotensin II-induced ERK1/ERK2 activation and protein synthesis are redox-dependent in glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J 381: 231–239, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kanzaki M, Zhang YQ, Mashima H, Li L, Shibata H, Kojima I: Translocation of a calcium-permeable cation channel induced by insulin-like growth factor-1. Nat Cell Biol 1: 165–170, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shimizu H, Hori Y, Kaname S, Yamada K, Nishiyama N, Matsumoto S, Miyata K, Oba M, Yamada A, Kataoka K, Fujita T: siRNA-based therapy ameliorates glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 622–633, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leone P, Shera D, McPhee SW, Francis JS, Kolodny EH, Bilaniuk LT, Wang DJ, Assadi M, Goldfarb O, Goldman HW, Freese A, Young D, During MJ, Samulski RJ, Janson CG: Long-term follow-up after gene therapy for canavan disease. Sci Transl Med 4: 165ra163, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ: Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol 70: 8098–8108, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kessler PD, Podsakoff GM, Chen X, McQuiston SA, Colosi PC, Matelis LA, Kurtzman GJ, Byrne BJ: Gene delivery to skeletal muscle results in sustained expression and systemic delivery of a therapeutic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 14082–14087, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McPhee SWJ, Francis J, Janson CG, Serikawa T, Hyland K, Ong EO, Raghavan SS, Freese A, Leone P: Effects of AAV-2-mediated aspartoacylase gene transfer in the tremor rat model of Canavan disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 135: 112–121, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Monahan PE, Samulski RJ: AAV vectors: Is clinical success on the horizon? Gene Ther 7: 24–30, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A: Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature 464: 1067–1070, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chaudhary K, Moore H, Tandon A, Gupta S, Khanna R, Mohan RR: Nanotechnology and adeno-associated virus-based decorin gene therapy ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F777–F782, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones BF, Boyles RR, Hwang SY, Bird GS, Putney JW: Calcium influx mechanisms underlying calcium oscillations in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 48: 1273–1281, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartlett DW, Davis ME: Physicochemical and biological characterization of targeted, nucleic acid-containing nanoparticles. Bioconjug Chem 18: 456–468, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang Y, Ding M, Chaudhari S, Ding Y, Yuan J, Stankowska D, He S, Krishnamoorthy R, Cunningham JT, Ma R: Nuclear factor κB mediates suppression of canonical transient receptor potential 6 expression by reactive oxygen species and protein kinase C in kidney cells. J Biol Chem 288: 12852–12865, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]