Abstract

Influenza is one of the most common infections threatening public health worldwide and is caused by the influenza virus. Rapid emergence of drug resistance has led to an urgent need to develop new anti-influenza inhibitors. In this study we established a 293T cell line that constitutively synthesizes a virus-based negative strand RNA, which expresses Gaussia luciferase upon influenza A virus infection. Using this cell line, an assay was developed and optimized to search for inhibitors of influenza virus replication. Biochemical studies and statistical analyses presented herein demonstrate the sensitivity and reproducibility of the assay in a high-throughput format (Z′ factor value>0.8). A pilot screening provides further evidence for validation of the assay. Taken together, this work provides a simple, convenient, and reliable HTS assay to identify compounds with anti-influenza activity.

Keywords: Cell-based assay, Gaussia luciferase, Influenza A virus, High-throughput screen

Graphical abstract

Using a stable cell line derived from 293T cells that are able to quantitate influenza A virus infectivity, an assay was developed and optimized to search for inhibitors of influenza virus. This work provides a simple, convenient, and reliable high throughput screening assay for anti-influenza drug development.

1. Introduction

Influenza viruses are members of the family of Orthomyxoviridae and are classified into three types: influenza A, B and C viruses based on antigenic differences. Influenza A virus has caused significant morbidity in the last and in this century1. To date, influenza-specific drugs include M2 ion channel blockers (amantadine and rimantadine) and neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir and zanamivir), both of which were approved to prevent and treat influenza2. However, rapid emergence of drug-resistant mutants restricts their utilization3, 4, and therefore leads to an urgent need to develop novel antivirals.

The use of high-throughput screening (HTS) technology for antiviral discovery is a fairly recent endeavor. Utilizing virus-inducible reporter genes to quantitate the infectivity has been achieved for several viruses5, 6. A reporter system mimicking the process of transcription/replication of influenza virus was constructed by Lutz et al.7. Cells were transfected with a reporter system that expressed Firefly luciferase in a response proportional to the infectivity of influenza virus. This luciferase assay is more rapid and simple than the standard plaque assays. Afterward de Vries et al.8 adapted this system by substituting Gaussia luciferase. Gaussia luciferase (hereafter referred to as Gluc), discovered from the marine copepod Gaussia princeps, can give high levels of light emission centered at 470 nm by catalyzing the oxidation of the substrate coelenterazine to coelenteramide9. This reaction requires no cofactors but O2, and it generates over 100-fold higher bioluminescent signal intensity when compared with other frequently used luciferase reactions (e.g., Renilla or Firefly luciferase)10, 11. With the help of a secretory signal, Gluc was secreted into the culture medium. Lysis of the cells was not necessary, and the measurement of luciferase activity was simple and time-saving, making Gluc assays a promising technique. Nevertheless, transient transfection of the Gluc reporter system is likely to introduce variation between the experiments.

In this work, a stable cell line derived from 293T cell was established, named 293T-Gluc. It synthesizes the reporter protein Gluc when infected with influenza A virus. We then developed a reporter assay based on this engineered cell line. Antiviral activities of three anti-influenza compounds (ribavirin, amantadine hydrochloride and nucleozin) were assessed by this assay. Results demonstrated the ability of this assay to identify influenza inhibitors. Several parameters (Z′ factor, CV, S/B, S/N) utilized to evaluate the quality of HTS (high-throughput screening) assays also validated our approach. These findings suggest that this cell-based assay is a promising tool to identify new anti-influenza drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and viruses

MDCK and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco׳s modified Eagle׳s medium with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) was rescued from eight plasmids using cocultured MDCK and 293T cells12. Influenza A/PR/8/1934 (H1N1), seasonal influenza B/Beijinghaidian/1386/2013 (Victoria) and influenza B/Massachusetts/02/2012 (Yamagata) were propagated in embryonated chicken eggs according to classical virological techniques. Virus titers were determined on MDCK cells and represented as the median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50), as previously described13. These viruses were provided kindly by Dr. Yuelong Shu at China CDC.

2.2. Reagents and plasmids

Coelenterazine-h was purchased from Promega. Nucleozin and TPCK-treated trypsin were obtained from Sigma. The Microsource Library (2000 compounds) was obtained from commercial sources and compounds from this library were dissolved in DMSO at 2 mmol/L. Plasmid pHH-Gluc (a kind gift from Dr. Erik de Vries8) was used as template for Gluc reporter system (containing the RNA polymerase I promoter/terminator and influenza A/WSN/33 NP segment UTRs) amplification. The primers used are as follows: forward primer 5′–TATGAATTCGGAAAAACGCCAGC AAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′–ATAAGGGCCCAAAATCTTCTTTCATCCGC-3′. PCR products were cloned into pLenti6/V5-DEST vector (Invitrogen) generating pLenti6-Gluc.

2.3. Establishing a stable reporter cell line

293T cells were transfected with pLenti6-Gluc using lipofectamine2000 in accordance with the manufacturer׳s protocol, and then were selected with 10 μg/mL Blasticidin 24 h post-transfection. Under antibiotic selective pressure several clonal colonies were obtained and tested for luciferase expression. One clonal cell line demonstrated high-level expression of luciferase; this cell line was named 293T-Gluc and was used for subsequent experiments.

2.4. Gluc reporter assay

293T-Gluc cells were cultured to 90% confluence, released with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS at 7×105 cells/mL. Cells were then seeded in the wells of 96-well plate at 100 μL/well. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, cells were infected with the indicated influenza viruses, which were contained in 10 μL serum-free DMEM culture medium. Post-infection medium also contained TPCK-treated trypsin with the final concentration of 1 μg/mL.

In specificity studies, infection was allowed to proceed for 24 h at 35 °C. For influenza A/PR/8/1934, influenza B/Beijinghaidian/1386/2013 (Victoria) and influenza B/Massachusetts/02/2012 (Yamagata), infections were carried out at a multiplicity of 0.1, 1 and 10, respectively, whereas a multiplicity of 0.1 and 1 was used when testing the response of influenza A/WSN/33 virus to Gluc reporter assay.

The dynamic signal range of the Gluc reporter assay was assessed by infecting 293T-Gluc cells with varying quantities of influenza A/WSN/33 virus (MOI of 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 and 1) and determining Gluc activity at various times post-infection (12, 24, 36 and 48 h post-infection).

For evaluation assay of antivirals and high-throughput screening, 1 μL of each tested compound was added to cells and incubated for 2 h prior to infection, after which cells were infected with influenza A/WSN/33 virus at an MOI of 0.05. After a further incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the cell supernatant was collected and measured for Gluc activity. In each 96-well plate ribavirin and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The inhibition rate of the tested compounds was calculated with the following equation, where RLU indicates relative light unit: Inhibition rate=(RLUinfected cells−RLUtested compound)/(RLUinfected cells −RLUmock-infected cells)×100%.

2.5. Luciferase activity assay

A stock of coelenterazine-h was prepared in ethanol to a concentration of 1.022 mmol/L and stored at –20 °C. Before assay the stock was diluted into PBS by a factor of 60, which was used as working solution for luminescence. The working solution was held for 30 min at room temperature in the dark to stabilize it14. For luminescence analysis, 60 μL of working solution was added to 10 μL of cell-free conditioned medium and measured for 0.5 s using a 96-well microplate luminometer with automated substrate injection (Berthold Centro LB 960). The results were expressed in relative light units (RLUs).

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Specificity for influenza A virus

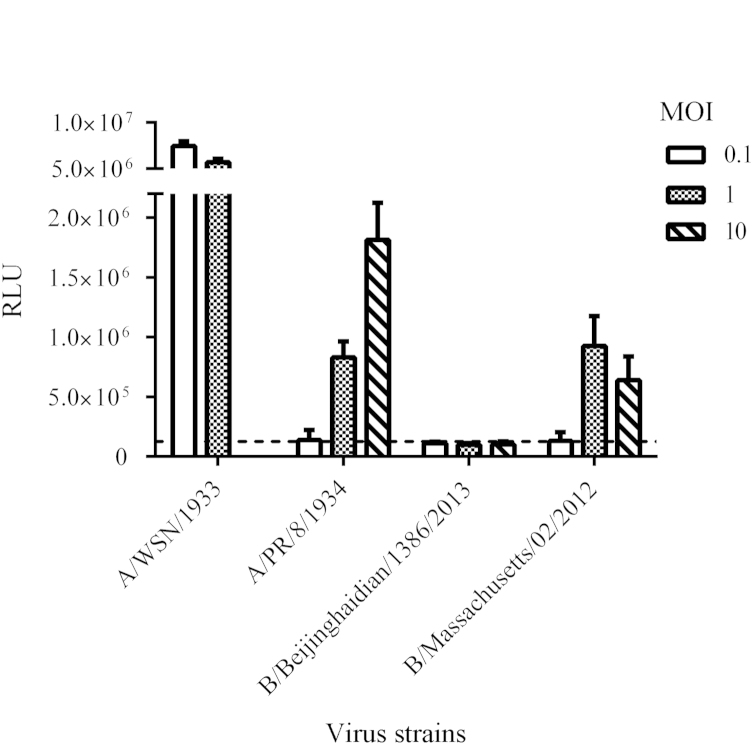

In construction of pLenti6-Gluc, the open reading frame (ORF) of the influenza A/WSN/33 NP protein was replaced by Gaussia luciferase and this RNA segment was inserted in a human RNA polymerase I promoter/terminator cassette in the reverse orientation and complementary sense. As a stable cell line, 293T-Gluc cells that contain pLenti6-Gluc synthesize a viral negative strand RNA constitutively, which expresses Gluc under control of the untranslated regions (UTRs) of the influenza A/WSN/33 NP segment (Fig. 1). We assessed the response of this reporter cell line to different strains of influenza virus. As shown in Fig. 2, the infection with influenza A viruses induced much higher luciferase activity than did the two strains of influenza B virus. The observation that the 293T-Gluc cell line is more responsive to influenza A virus may reflect species specificity of UTR region for the corresponding RdRp, which is consistent with a previous observation7. Among all the virus strains tested, the A/WSN/33 strain exhibited the most potent ability to induce luciferase activity when the cells were infected at identical MOI. Therefore, influenza A/WSN/33 virus was used for all subsequent experiments.

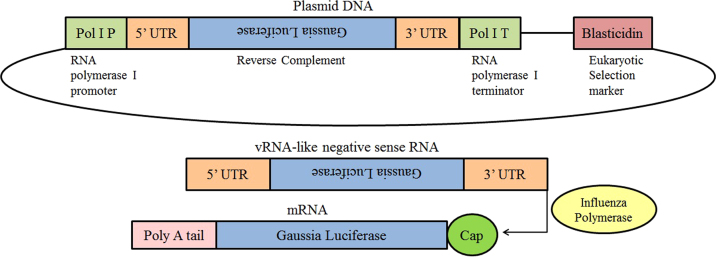

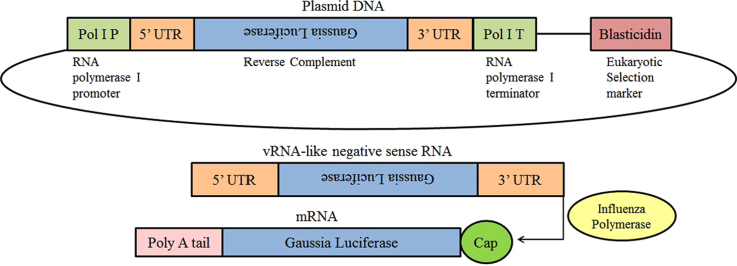

Figure 1.

Schematic of the influenza virus Gluc reporter construct. The Gaussia luciferase open reading frame was inserted in the reverse orientation and complementary sense between the influenza virus untranslated regions (UTRs) which serve as the viral promoter. This cassette is flanked by a human RNA polymerase I (Pol I) promoter and terminator. The transcribed RNA is a vRNA-like negative sense RNA, which mimics an influenza virus genome segment. Upon infection, the influenza virus polymerase recognizes the UTRs and Gaussia luciferase is transcribed and expressed. A eukaryotic selection marker of Blasticidin was used to establish stable cell line 293T-Gluc.

Figure 2.

Specificity of Gluc reporter assay. Experiments were conducted as described in Materials and Methods. 293T-Gluc cells were seeded and infected with indicated viruses at various doses for 24 h. Infection with A/WSN/33 at an MOI of 10 was not tested. Gluc activity of mock-infected cells was regarded as background and indicated by a dashed line. Data were shown as average±standard deviation (n=3).

3.2. Dynamic signal range of the 293T-Gluc reporter assay

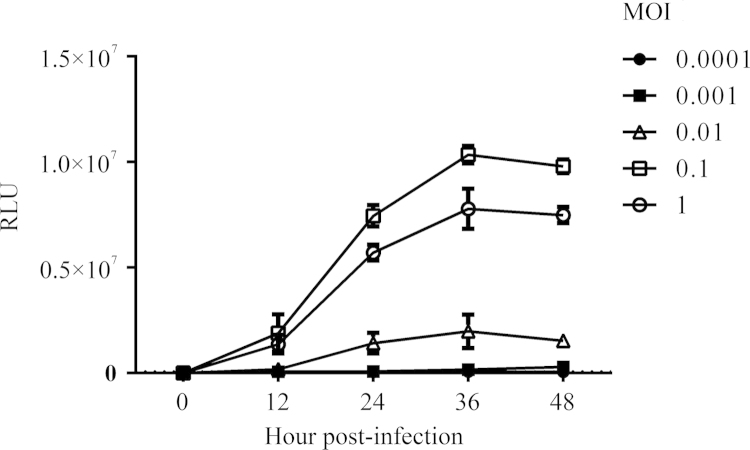

To further optimize the assay a signal range was determined using serial 10-fold dilutions of influenza A/WSN/33 virus. As shown in Fig. 3, infection at MOIs of 0.1 or higher induced a Gluc signal at 12 h post-infection, and signal intensity significantly increased thereafter and reached a peak at 36 h post-infection. When infected with virus at MOIs of 0.001 or lower, cells failed to generate a detectable Gluc signal. It should be noted that viral infection at an MOI of 1 induced significant CPE in 293T-Gluc cells like MDCK, while the cells kept a normal morphology during the 96 h time period of post-infection when the MOI was less than 0.1 (data not shown). This may explain the observation that the Gluc signal from the cells infected at an MOI of 1 was less than that of MOI of 0.1 (Fig. 3), most likely due to reduced cell viability. Based on this result, the amount of virus used and the measurement time point were set at an MOI of 0.05 and 24 h post-infection, respectively.

Figure 3.

Signal range of the 293T-Gluc reporter assay. 293T-Gluc cells were infected with varying quantities of influenza A/WSN/33 virus. Infections were performed at MOI of 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 and 1. Gluc activities were measured at 4 times points with equal intervals of 12 h and that of mock-infected cells was regarded as background (indicated by a dashed line, which is very approachable to X-axis). Data are shown as average±standard deviation (n=3).

3.3. Evaluation of anti-influenza virus agents

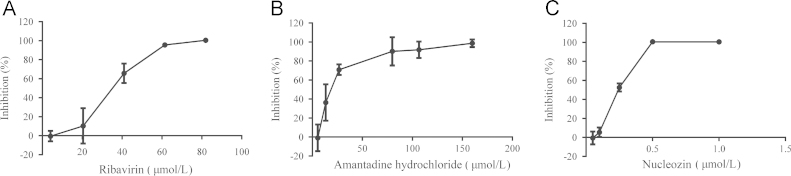

To ascertain assay sensitivity, three reference compounds, including ribavirin, amantadine hydrochloride and nucleozin, were examined in our assay. Ribavirin is used against several DNA and RNA viruses including influenza viruses15, 16. It is converted to ribavirin monophosphate, which disturbs GTP synthesis, leading to inhibition of RNA synthesis in cells17. Amantadine hydrochloride, approved for the treatment of influenza infections, acts in the early phase of the life cycle of influenza A virus to target the M2 ion channel18, 19. Nucleozin is a novel inhibitor with anti-influenza activity. It impedes influenza A virus replication by triggering the aggregation of NP and inhibits its nuclear accumulation20. We used the Gluc reporter assay to evaluate these antivirals in dose-response experiments, measuring IC50 (Fig. 4). All the compounds showed the ability to reduce the luciferase signal driven by influenza A/WSN/33 virus. IC50 values determined from our experiments were comparable to data previously reported (Table 1), demonstrating the applicability of the Gluc reporter assay for screening influenza inhibitors. Furthermore, compared with the conventional plaque reduction assay (PRA)24, the method herein is more rapid and simple for the determination of IC50 values. At least 48 h were needed before the number of plaques could be calculated, whereas our assay can give results in 24 h after infection. Moreover, this unbiased and automated method of infectivity quantitation avoids tedious plaque counting, making it an ideal approach.

Figure 4.

Dose–response relationships of three anti-influenza inhibitors. (A) Ribavirin; (B) amantadine hydrochloride; (C) nucleozin. Tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO at various concentrations. Data from the assay were analyzed and calculated by GraphPad Prism software. Three independent experiments were done, and representative data are shown as average±standard deviation (n=3).

Table 1.

Inhibitory activity of the compounds against influenza A replicationa.

| Compound | IC50 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tested (μmol/L)b | Reported (μmol/L) | Ref. | |

| Ribavirin | 26.62±7.15 | 11.06 | 21 |

| Amantadine hydrochloride | 24.94±6.10 | 78.32 | 22 |

| Nucleozin | 0.23±0.04 | 0.32 | 23 |

Activity against influenza A/WSN/33 virus.

Values are mean±standard deviation from three independent experiments.

3.4. High-throughput screening

The above results suggest the potential to use the Gluc reporter assay to screen compounds against influenza A virus. To ensure that the assay can be used in high-throughput screening, we assessed its accuracy by using several statistical parameters25 (Table 2). Z′ factor is a simple statistical characteristic for HTS assay. It can be used to evaluate the performance of an assay. A robust assay should have a Z′ factor>0.5 and the larger the value of Z′ factor, the better the data quality of the assay26. The Z′ factor in our experiments was 0.84 (n=48), which is considered to be excellent for use in HTS (Fig. 5). Normally, infected cells treated with a positive anti-influenza compound are used as positive control for calculating the Z′ factor. Nevertheless, according to the assay validation guidance for agonist assays (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83783/), the background signal is also suitable for use as a ‘minimum signal’. Since viral infection acts as an agonist of luminescent protein, we used mock-infected cells as positive control in the validation analysis. Similarly, other work used mock-infected cells as positive control to calculate the Z′ factor27. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4, most of the anti-influenza compounds tested were able to achieve full inhibition in our assay. Moreover, the minimum signals derived from infected cells treated with one of the positive anti-influenza compounds were close to that of mock-infected cells.

Table 2.

Summary of statistical parameters to assess the robustness of the HTS assay.

Z′=1–3(STDinfected cells+STDmock-infected cells)/(MEANinfected cells−MEANmock-infected cells).

%CV (coefficient of variation)=STDinfected cells/MEANinfected cells×100%.

S/B (signal-to-background ratio)=Meaninfected cells/Meanmock-infected cells.

S/N (signal-to-noise ratio)=(Meaninfected cells−Meanmock-infected cells)/((STDinfected cells)2+(STDmock-infected cells)2)1/2.

Figure 5.

Determination of Z′ factor of the 293T-Gluc report assay. Approximately 7×104 293T-Gluc cells were seeded per well of a 96-well tissue culture plate and half were infected with influenza A/WSN/33 virus at an MOI of 0.05. At 24 h post-infection, Gluc activity was measured and Z′ factor value was calculated as described.

CV is another parameter used for quality assessment. It reflects signal deviation within an assay and is recommended to be less than or equal to 20% (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83783/). The CV of our assay was 5.79%, which meets the requirements for HTS. In addition, the S/B ratio (23.24) and the S/N ratio (16.29) were comparable to those of other HTS assays reported28, 29, proving our assay was suitable for use in a high-throughput screen.

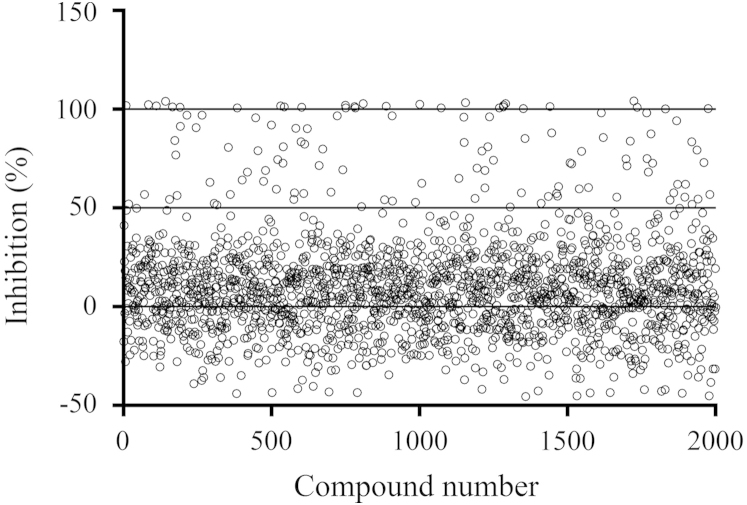

As a proof of concept, we carried out a pilot screening of the Microsource Library as described above and the results are plotted in Fig. 6. In each 96-well plate, ribavirin and DMSO were used as a positive and negative control, respectively. Majority of the 2000 screened compounds did not decrease the luminescence signal by more than 50%. Seventeen showed strong luminescence reduction by 90%–100%, which translates to a hit rate of 0.85%. Compared with assays exploiting the principle of cytopathic effects (CPE) protection30, the approach established here is rapid and simple for anti-influenza inhibitor screening. We anticipate that this approach will facilitate the discovery of compounds with anti-influenza activity and lead to drug development.

Figure 6.

Results of the pilot high-throughput screening. Two thousand compounds from Microsource library were automatically added to cells by machine arm and final concentrations were 20 μmol/L. Each circle represents the inhibition rate of each compound. Seventeen compounds showed 90–100% inhibition of luminescence signal with a hit rate of 0.85%.

4. Conclusions

Influenza virus remains a health threat, and much more work needs to be done to discover new antivirals. In this work we reported a cell-based high-throughput assay to identify inhibitors for influenza virus. The assay used Gaussia luciferase as a readout. Several criterions for HTS were evaluated, including Z′ factor and CV. Results obtained validated the robustness of our assay. Furthermore, we used this high-throughput assay to screen 2000 small molecules at 20 μmol/L. Seventeen compounds showed 90%–100% inhibition of luminescence signal for a rate of 0.85%. Utilization of this cell-based high-throughput assay will benefit identification of new anti-influenza lead compounds in future work.

Acknowledgments

We thank National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention for the seasonal influenza B/Beijinghaidian/1386/2013 (Victoria) and B/Massachusetts/02/2012 (Yamagata) strains. This work was supported in part by National S&T Major Special Project on Major New Drug Innovation (No. 2012ZX09301-002-004) (S.C.), National Science and Technology Major Project, “China Mega-Project for Infectious Disease” (No. 2013ZX10004601-002), and the Xiehe Scholar (S. C.).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Medina R.A., García-Sastre A. Influenza A viruses: new research developments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:590–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das K. Antivirals targeting influenza A virus. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6263–6277. doi: 10.1021/jm300455c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samson M., Pizzorno A., Abed Y., Boivin G. Influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2013;98:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKimm-Breschkin J.L. Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors: antiviral action and mechanisms of resistance. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7 Suppl 1:25–36. doi: 10.1111/irv.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhlberger E., Lotfering B., Klenk H.D., Becker S. Three of the four nucleocapsid proteins of Marburg virus, NP, VP35, and L, are sufficient to mediate replication and transcription of Marburg virus-specific monocistronic minigenomes. J Virol. 1998;72:8756–8764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8756-8764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohl A., Hart T.J., Noonan C., Royall E., Roberts L.O., Elliott R.M. A bunyamwera virus minireplicon system in mosquito cells. J Virol. 2004;78:5679–5685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5679-5685.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz A., Dyall J., Olivo P.D., Pekosz A. Virus-inducible reporter genes as a tool for detecting and quantifying influenza A virus replication. J Virol Methods. 2005;126:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries E., Tscherne D.M., Wienholts M.J., Cobos-Jimenez V., Scholte F., Garcia-Sastre A. Dissection of the influenza A virus endocytic routes reveals macropinocytosis as an alternative entry pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001329. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhaegent M., Christopoulos T.K. Recombinant Gaussia luciferase. Overexpression, purification, and analytical application of a bioluminescent reporter for DNA hybridization. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4378–4385. doi: 10.1021/ac025742k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remy I., Michnick S.W. A highly sensitive protein–protein interaction assay based on Gaussia luciferase. Nat Methods. 2006;3:977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruecker O., Zillner K., Groebner-Ferreira R., Heitzer M. Gaussia-luciferase as a sensitive reporter gene for monitoring promoter activity in the nucleus of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Genet Genomics. 2008;280:153–162. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann E., Neumann G., Kawaoka Y., Hobom G., Webster R.G.A. DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hygiene. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tannous B.A. Gaussia luciferase reporter assay for monitoring biological processes in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:582–591. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidwell R.W., Huffman J.H., Khare G.P., Allen L.B., Witkowski J.T., Robins R.K. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of virazole: 1-beta-d-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide. Science. 1972;177:705–706. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4050.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snell N.J. Ribavirin—current status of a broad spectrum antiviral agent. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:1317–1324. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.8.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leyssen P., Balzarini J., De Clercq E., Neyts J. The predominant mechanism by which ribavirin exerts its antiviral activity in vitro against flaviviruses and paramyxoviruses is mediated by inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase. J Virol. 2005;79:1943–1947. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1943-1947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies W.L., Grunert R.R., Haff R.F., McGahen J.W., Neumayer E.M., Paulshock M. Antiviral activity of 1-adamantanamine (amantadine) Science. 1964;144:862–863. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3620.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann C.E., Neumayer E.M., Haff R.F., Goldsby R.A. Mode of action of the antiviral activity of amantadine in tissue culture. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:623–628. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.3.623-628.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao R.Y., Yang D., Lau L.S., Tsui W.H., Hu L., Dai J. Identification of influenza A nucleoprotein as an antiviral target. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:600–605. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsay S.M., Timm A., Yin J. A quantitative comet infection assay for influenza virus. J Virol Methods. 2012;179:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abed Y., Goyette N., Boivin G. Generation and characterization of recombinant influenza A (H1N1) viruses harboring amantadine resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:556–559. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.556-559.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng H., Wan J., Lin M.I., Liu Y., Lu X., Liu J. Design, synthesis, and in vitro biological evaluation of 1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carboxamide derivatives as new anti-influenza A agents targeting virus nucleoprotein. J Med Chem. 2012;55:2144–2153. doi: 10.1021/jm2013503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stranska R., Schuurman R., Scholl D.R., Jollick J.A., Shaw C.J., Loef C. ELVIRA HSV, a yield reduction assay for rapid herpes simplex virus susceptibility testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2331–2333. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2331-2333.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iversen P.W., Eastwood B.J., Sittampalam G.S., Cox K.L. A comparison of assay performance measures in screening assays: signal window, Z′ factor, and assay variability ratio. J Biomol Screen. 2006;11:247–252. doi: 10.1177/1087057105285610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J.H. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann H.H., Palese P., Shaw M.L. Modulation of influenza virus replication by alteration of sodium ion transport and protein kinase C activity. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Severson W.E., Shindo N., Sosa M., Fletcher T., 3rd, White E.L., Ananthan S. Development and validation of a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of SARS CoV and its application in screening of a 100,000-compound library. J Biomol Screen. 2007;12:33–40. doi: 10.1177/1087057106296688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noah J.W., Severson W., Noah D.L., Rasmussen L., White E.L., Jonsson C.B. A cell-based luminescence assay is effective for high-throughput screening of potential influenza antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2007;73:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su C.Y., Cheng T.J., Lin M.I., Wang S.Y., Huang W.I., Lin-Chu S.Y. High-throughput identification of compounds targeting influenza RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19151–19156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013592107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]