Abstract

Mononuclear copper complexes, [(tmpa)CuII(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1, tmpa = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine) and [(BzQ)CuII(H2O)2](ClO4)2 (2, BzQ = bis(2-quinolinylmethyl)benzylamine)], act as efficient catalysts for the selective two-electron reduction of O2 by ferrocene derivatives in the presence of scandium triflate (Sc(OTf)3), in acetone, whereas 1 catalyzes the four-electron reduction of O2 by the same reductant in the presence of Brønsted acids such as triflic acid. Following formation of the peroxo-bridged dicopper(II) complex [(tmpa)CuII(O2)CuII(tmpa)]2+, the two-electron reduced product of O2 with Sc3+ is observed to be scandium peroxide ([Sc3+(O22−)]+). In the presence of three equiv of hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA), [Sc3+(O22−)]+ was oxidized by [Fe(bpy)3]3+ (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) to the known superoxide species [(HMPA)3Sc3+(O2•−)]2+ as detected by EPR spectroscopy. A kinetic study revealed that the rate-determining step of the catalytic cycle for the two-electron reduction of O2 with 1 is electron transfer from Fc* to 1 to give a cuprous complex which is highly reactive toward O2, whereas the rate-determining step with 2 is changed to the reaction of the cuprous complex with O2 following electron transfer from ferrocene derivatives to 2. The explanation for the change in catalytic O2-reaction stoichiometry from four-electron with Brønsted acids to two-electron reduction in the presence of Sc3+ and also for the change in the rate-determining step is clarified based on a kinetics interrogation of the overall catalytic cycle as well as each step of the catalytic cycle with study of the observed effects of Sc3+ on copper-oxygen intermediates.

Introduction

Copper proteins play important roles in oxidation of substrates accompanied by two-electron reduction of dioxygen (O2) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or four-electron reduction of O2 to water (H2O) depending on the type of enzymes.1 For example, in the oxidation of their substrates, galactose oxidases2 and amine oxidases3 effect the two-electron reduction of O2 to hydrogen peroxide4 whereas multicopper oxidases (MCO’s)5 and heme-copper oxidases (HCO’s)6 facilitate the four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O. The catalytic four-electron reduction of O2 with synthetic copper complexes as well as other metal complexes has merited special attention because of not only the mechanistic interest in relation to MCO’s but also in development of a fuel cell technology and their application using earth-abundant metals such as iron, cobalt and copper.7–15 On the other hand, the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 to H2O2 has also attracted increasing interest, because H2O2 is regarded as a promising candidate as a high-density energy carrier as compared with gaseous hydrogen and also H2O2 can be used as a liquied fuel in simple one-compartment fuel cells.16–18 There have been many reports on the electrocatalytic and homogeneous four-electron reduction of O2 with copper complexes.16–24 In contrast, there has been only few examples for the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 using a copper complex.25 Whether copper complexes are effective for two-or four-electron reduction of O2 depends on a variety of factors, including the ligand type and resulting nature of copper-oxygen intermediates formed as reactive species in the O2 reduction catalysis.24,25 The counter anions of proton sources employed also affects the O2-reduction catalytic reactivity with copper complexes, with-respect-to the observed stoichiometry and/or mechanism of reaction.26,27 However, there has been no report on the change in the number of electrons to reduce O2 (two-electron vs four-electron) in O2 reduction catalysis induced by metal ions acting as Lewis acids.

We report herein the drastic change to a two-electron from a four-electron reduction of O2 with [(tmpa)CuII(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1) induced by the Lewis acid [Sc(OTf)3]. In contrast to the case of 1, the selective two-electron reduction of O2 occurred with [(BzQ)CuII(H2O)2](ClO4)2 (2) in the presence of triflic acid (HOTf) as well as Sc(OTf)3. The mechanism of the selective two-electron reduction of O2 with 1 and 2 is examined by a kinetics study of the overall catalytic cycle as well as each step of the catalytic cycle with study of the observed effects of Sc3+ on copper-oxygen intermediates.

Experimental Section

Materials

The following reagents were obtained commerceally and used as received: Scandium triflate [Sc(OTf)3], decamethylferrocene (Fc*), 1,1′-dimethylferrocene (Me2Fc), ferrocene (Fc), perchloric acid (70%), trifluoroacetic acid, hydrogen peroxide (30%) and NaI (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Following literature procedures,28 acetone was dried and distilled under Ar. The compounds [(tmpa)CuII(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1)29 and bis(2-quinolinylmethyl)benzylamine (BzQ)30 were prepared as described.

[(BzQ)CuII(H2O)2](ClO4)2; (2) A 50 mL flask with BzQ (389 mg, 1.0 mmol) and Cu(ClO4)2 ·6H2O (370 mg, 1.0 mmol), as prepared and 20 mL MeOH was then added; the solution became blue and with stirring over 1 h, it yielded a precipitate consisting of blue microcrystals. The solid product 2 was collected employing a vacuum filtration procedure and then and washed with 15mL MeOH, and dried under vacuum. (599 mg, 0.86 mmol, 86% yield) Anal. Calcd (C28H29Cl2CuO10N3): C, 47.14; H, 3.96; N, 6.11. Found: C, 47.15; H, 3.87; N, 6.06. X-ray quality crystals were obtained by allowing pentane to slowly diffuse into a saturated acetone solution of 2.

Single Crystal X-ray Crystallography

All reflection intensities were measured at 110(2) K using a SuperNova diffractometer (with Atlas detector) and Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å) using the CrysAlisPro program (Version 1.171.36.32 Agilent Technologies, 2013); the latter was also employed to refine cell dimensions and for data reduction. The structure was solved and refined on F2 using SHELXS-2013 (Sheldrick, 2013). Analytical numeric absorption corrections based on a multifaceted crystal model were applied using CrysAlisPro. The data collection temperature was controlled using a Cryojet (Oxford Instruments) system. Unless otherwise specified, the H atoms were placed at calculated positions using AFIX 23, AFIX 43 or AFIX 137 instructions with isotropic displacement parameters with values 1.2 or 1.5 times Ueq those for the C atoms attached. The H atoms attached to O1Wn, O2Wn and O3Wn (n = 1, 2) (coordinated water molecules) were found from difference Fourier maps, and their coordinates were refined freely (DFIX instructions were used to restrain the O–H and H…H distances within acceptable ranges).

There are three crystallography independent Cu(II) complexes, six ClO4− perchlorate anions, plus seven lattice acetone solvate molecules per asymmetric unit. The structure is mostly ordered. Five of the six counterions are disordered over two orientations. The occupancy factors of the major components of the disorder refine to 0.871(6), 0.54(2), 0.661(6), 0.591(4), 0.560(16).

C102H123Cl6Cu3N9O37: moiety formula: 3(C27H27CuN3O2), 6(ClO4), 7(C3H6O), Fw = 2470.41, blue block, 0.34 × 0.33 × 0.18 mm3, monoclinic, P21/n (no. 14), a = 22.8236(3), b = 12.18146(19), c = 39.6106(6) Å, β = 92.6704(13)°, V = 11000.8(3) Å3, Z = 4, Dx = 1.492 g cm−3, μ = 2.760 mm−1, Tmin-Tmax: 0.474–0.684. 73408 Reflections were measured up to a resolution of (sin θ/λ)max = 0.62 Å−1. 21523 Reflections were unique (Rint = 0.0243), of which 19284 were observed [I > 2σ(I)]. 1682 Parameters were refined using 746 restraints. R1/wR2 [I > 2σ(I)]: 0.0341/0.0914. R1/wR2 [all refl.]: 0.0388/0.0948. S = 1.028. Residual electron density found between −0.55 and 0.66 e Å−3. The molecular weight is given for the moiety formula.

Reaction Procedure

Spectral changes (Hewlett Packard 8453 photodiode-array spectrophotometer with a quartz cuvette (path length = 10 mm)) at 298 K were observed as a function of varying Sc(OTf)3 concentrations during the dioxygen catalytic reduction experiments. Employing a microsrying, an acetone solution of Sc(OTf)3 was added to an O2-saturated acetone solution containing [(tmpa)CuII(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1) (1.0 × 10−5 M) or [(BzQ)CuII(H2O)2](ClO4)2 (2) (1.0 × 10−4 M) and Fc* (2.0 × 10−3 M). Fc*+ and Me2Fc+ concentrations being produced during the reaction were determined from known absorptivity data, λmax = 780 nm (ε = 500 M−1 cm−1 at 298 K and 600 M−1 cm−1 at 213 K) for Me2Fc*+ and λmax 650 nm, εmax = 360 M−1 cm−1 for Me2Fc+. For Fc*+ the extinction coefficient was estimated by carrying out a Fc* electron-transfer oxidation using [RuIII(bpy)3]-(PF6)3. The limiting concentration of O2 in an acetone solution was prepared by a mixed gas flow of O2 and N2, using a gas mixer (Kofloc GB-3C, KOJIMA Instrument Inc.), that able to effect controlled pressure and flow rate mixing of two gases. Hydrogen peroxide determination was carried out by standard iodide titration where the O2 reduction product solution in acetone was diluted and reacted with NaI in excess. Quantitation of the I3− formed was then calculated using its visible spectrum (λmax = 361 nm, ε = 2.5 × 104 M−1 cm−1).31 All low-temperature UV–vis absorption spectra and spectral changes were recorded using a Hewlett Packard 8453A diode array spectrophotometer with attached liquid nitrogen cooled cryostat (Unisoku USP-203-A).

Kinetic Measurements

Fast reaction with short half-lives (≤ 10 s) at 298 K were performed with a UNISOKU RSP-601 stopped flow spectrophotometer possessing a MOS-type high selective photodiode array and attached Unisoku thermostated cell holder. The kinetics of electron-transfer from Fc* to 1 were analyzed by monitoring absorption band changes due to Fc*+ formation. Pseudo-first-order conditions were used throughout, with Fc* concentrations kept at more than a 10-fold excess compared to that of 1.

Electrochemistry

Copper(II) complex cyclic voltammetry using an ALS 630B electrochemical analyzer was utilized for measurements at 1 atm and under nitrogen or argon, both in the presence and absence of Sc(OTf)3; conditions included use of deaerated acetone solutions with 0.1 M [(n–butyl)4N]PF6 (TBAPF6) all at RT. A platinum working electrode (surface area of 0.3 mm2) was employed within a conventional three-electrode cell using a Pt counter electrode. The BAS platinum working electrode was often polished with an alumina suspension (BAS); prior to use this, acetone was used to wash the electrode. The reference electrode used was Ag/AgNO3 (0.01 M) and to convert potentials to values vs the SCE, 0.29 V was added.32

EPR Measurements

A JEOL JES-RE1XE spectrometer was used to record EPR spectra of Cu(II) and scandium superoxide complexes. The modulation amplitude employed was selected to optimize the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio and resolution under conditions of non-saturating microwave power. A Mn2+ marker inserted into the EPR cavity was used to determine g values and hyperfine coupling constants.

Theoretical Calculations

Using a 32-processor QuantumCube™ with Gaussian 09 (revision A.02), DFT calculations on copper complexes were performed. A UCAM-B3LYP/6-311G(d) level of theory was employed for geometry optimization.33–36 Computational results graphical output were generated using GaussView (ver. 3.09; Semichem, Inc.).37

Results and Discussion

Catalytic Two-Electron Reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1 in the Presence of Sc(OTf)3

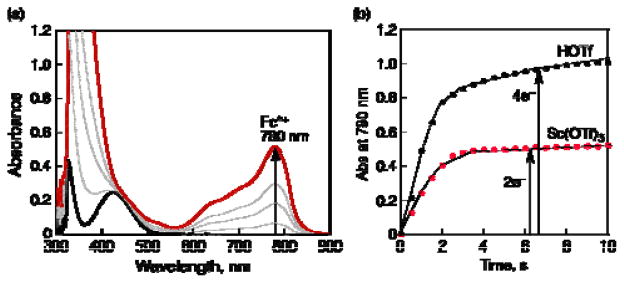

We have previously reported that [(tmpa)CuII(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1) (tmpa = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine) catalyzed the four-electron reduction of O2 by decamethylferrocene (Fc*) to H2O in the presence of perchloric acid or trifluoroacetic acid in acetone as shown in eq 1,

|

(1) |

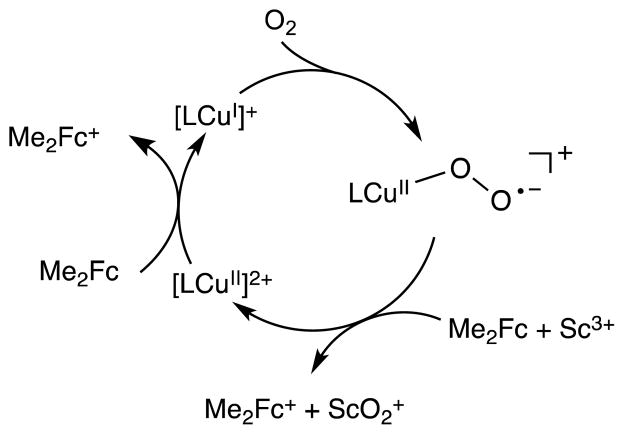

where four-equiv of Fc*+ (decamethylferrocinium ion) relative to O2 were consumed.24a,26 When Sc(OTf)3 is employed as a Lewis acid instead of HClO4 or CF3COOH, 1 also efficiently catalyzes the reduction of O2 where Fc*+ is also produced (Figure 1). In this case, however, the stoichiometry of O2 reduction is different and follows eq 2,

Figure 1.

(a) UV-vis spectral changes observed in the two-electron and four-electron reduction of O2 (0.5 mM) by Fc* (2.0 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (2.0 mM) catalyzed by 1 (40 μM) in acetone at 298 K. (b) Time courses of absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+ in the two-electron and four-electron reduction of O2 (0.5 mM) by Fc* (2.0 mM) catalyzed by 1 (40 μM) in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 (2.0 mM) and HOTf (40 mM), respectively.

| (2) |

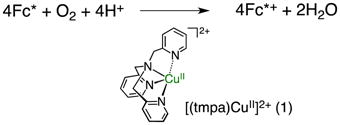

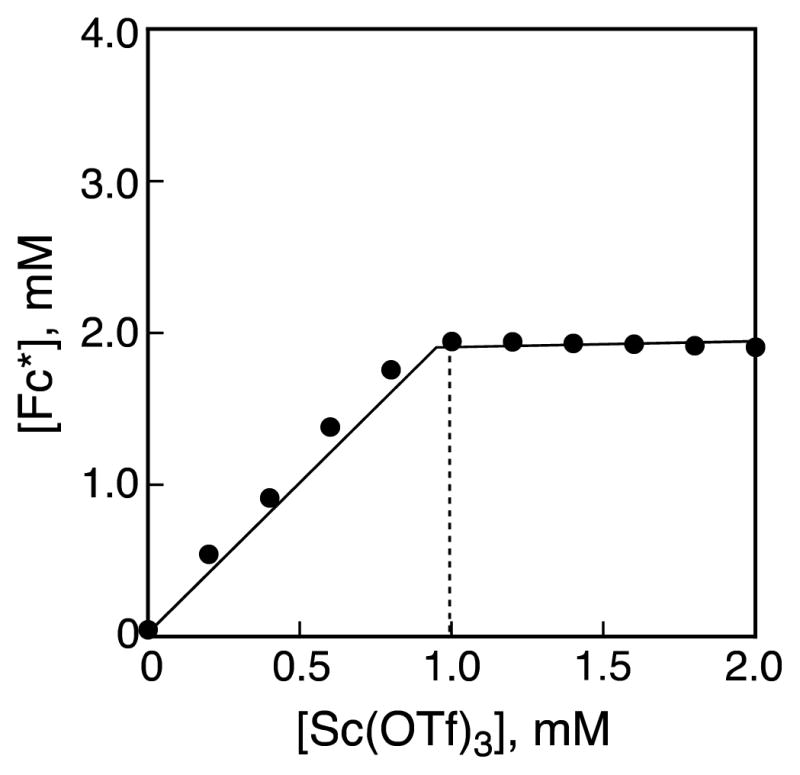

where two-equivalents of Fc*+ (λmax = 780 nm) relative to O2 are produced and one equiv of Sc3+ is consumed instead of four protons (eq 1), as shown in the spectral titration in Figure 2. The reduced product of O2 is [Sc3+(O22−)]+, based on the stoichiometry determined, Figure 2. The yield of [Sc3+(O22−)]+ was determined to be 100% based on an iodometric titration (Figure S1 in Supporting Information (SI)).29

Figure 2.

Plot of absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+ vs concentration of Sc(OTf)3 in the two-electron reduction of O2 (2.5 mM) by Fc* (2.0 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (0–2.0 mM) catalyzed by 1 (40 μM) in acetone at 298 K.

To further support the formation of scandium peroxide ([Sc3+(O22−)]+), the reaction mixture was oxidized using the one-electron oxidant ([Fe(bpy)3]3+), which was stabilized in the presence of three equiv of the hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA) ligand to produce ([(HMPA)3Sc3+(O2•−)]2+), as shown by eq 3.37 The formation of [(HMPA)3Sc3+(O2•−)]2+ was detected

| (3) |

by EPR spectroscopy as shown in Figure 3. The g value (2.0112) and and superhyperfine coupling constant due to scandium (I =7/2; aSc = 3.82 G) are the same as those reported previously.38 The end-on coordination of O2•− to Sc3+ is indicated by inequivalent a(17O) values (14 and 17 G)38 and supported by optimized geometry calculations by an unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) SCF optimization using the 6-311++G** basis set.39 In contrast to the case for this superoxo complex, DFT calculations suggest that the side on structure of the peroxo complex ([Sc3+(O22−)]+) is more stable than an end-on coordinated peroxo-scandium species (Figure S2 in SI).

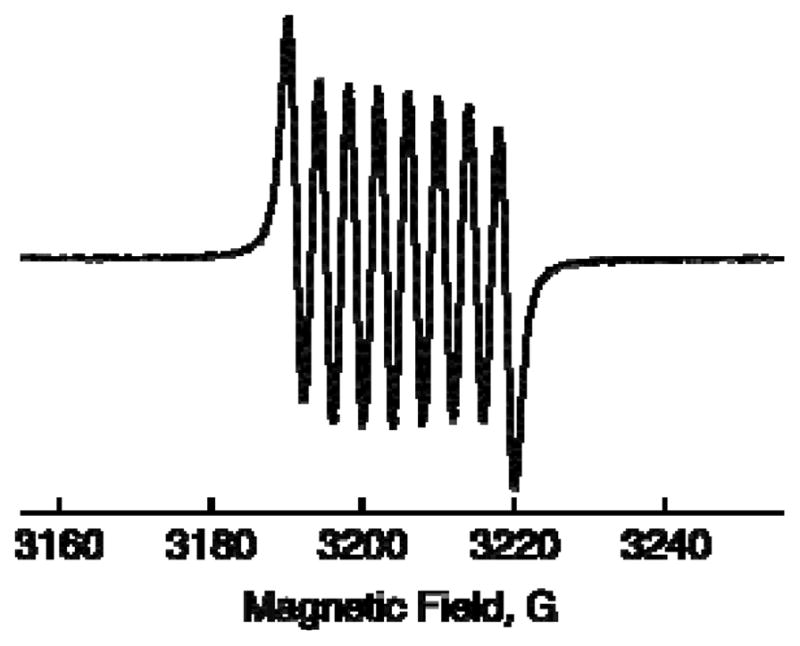

Figure 3.

EPR spectrum observed after addition of [FeIII(bpy)3]3+ and HMPA (30 mM) to an N2-saturated acetone solution of [Sc3+(O22−)]+, which was produced by the two-electron reduction of O2 (11 mM) by Fc* in the presence of [(tmpa)CuII](ClO4)2 (1) (10 μM) and Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) in acetone at 298 K. The g value is 2.011, confirming the production of the known HMPA-Sc-superoxide complex.

Kinetics and Mechanism of Catalytic Two-Electron Reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1

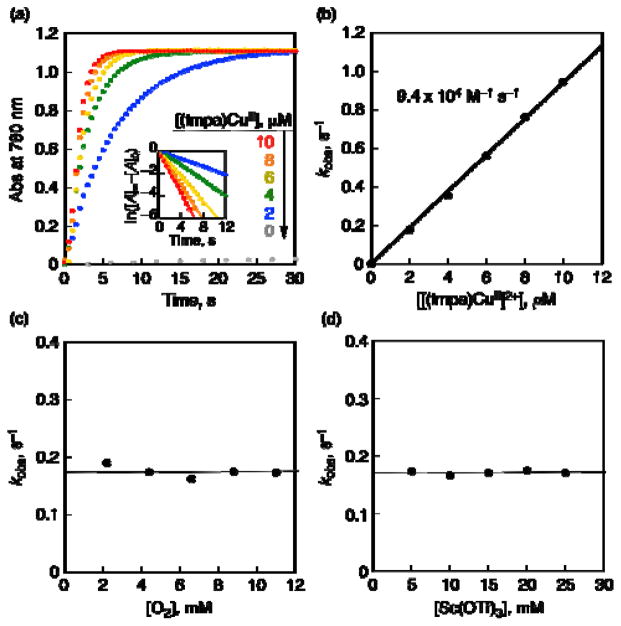

The rate of formation of Fc*+ in the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1 was monitored by an increase in absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+. The rate obeyed pseudo-first-order kinetics in the presence of excess Sc(OTf)3 and O2 relative to Fc* (Figure 4a). The observed pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) increases linearly with increasing concentration of 1 (Figure 4b), whereas the kobs value remained constant with increasing concentration of O2 (Figure 4c). The kobs value was also constant at the Sc(OTf)3 concentration above 5 mM (Figure 4d). Thus, the kinetic formulation of the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1 in the presence of large excess Sc(OTf)3 is given by eq 4,

Figure 4.

(a) Time profiles of formation of Fc*+ monitored by absorbance at 780 nm (ε = 500 M−1 cm−1) in the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (2.0 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) catalyzed by 1 (2–10 μM) in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K. Inset: First-order plots. (b) Plot of kobs vs [1] for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (2.0 mM) in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) in acetone at 298 K. (c) Plot of kobs vs [O2] for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (2.0 mM) catalyzed by 1 (2.0 μM) in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K. (d) Plot of kobs vs [Sc(OTf)3] for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* (2.0 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (5–25 mM) catalyzed by 1 (2 μM) in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K.

| (4) |

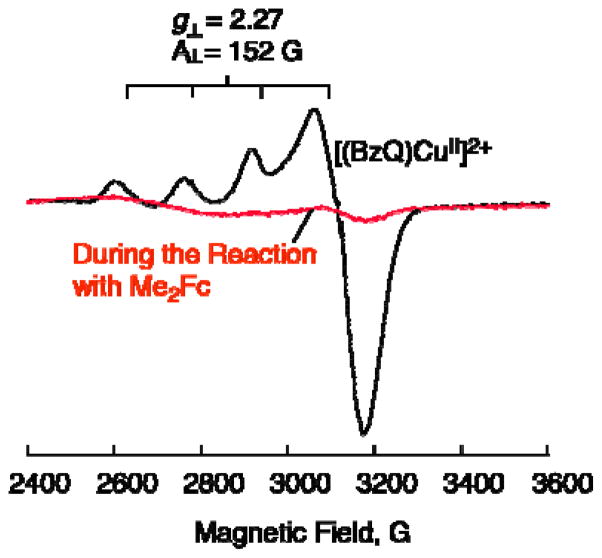

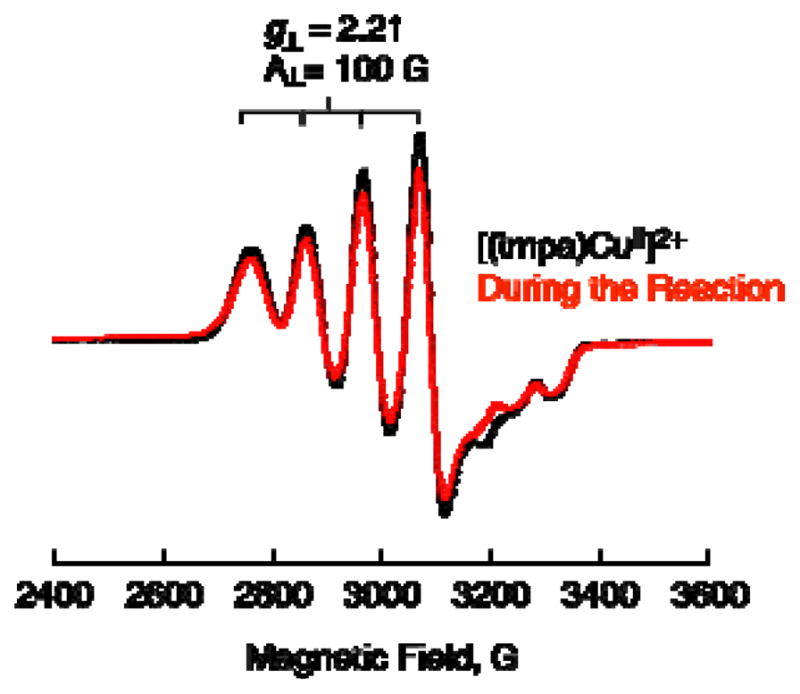

where kcat is the second-order catalytic rate constant of 1. The kcat value was determined to be (9.4 ± 0.5) × 104 M−1 s−1 at 298 K. This value is twice of the rate constant (ket) of electron transfer from Fc* to 1 (5.0 ± 0.1) × 105 M−1 s−1 in acetone at 298 K,24a i.e., kcat = 2ket, because the electron transfer should occur twice to reduce O2 in the catalytic cycle when two equiv of Fc*+ are formed. This inidicates that electron transfer from Fc* to 1 is the rate-determining step in the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1. In such a case, 1 should remain as the cupric complex [(tmpa)CuII]2+ during the catalytic two-electron reduction reaction. This was confirmed by the observation of the EPR spectrum of 1 as measured during catalysis as shown in Figure 5, where the EPR spectrum (red line) during the reaction is the same as [(tmpa)CuII]2+ before the reaction (black line).

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of [(tmpa)CuII]2+ 1 (0.10 mM) (black line) measured at 77 K during the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 (11 mM) by Fc* (2 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) at 298 K (red line). EPR parameters of [(tmpa)CuII]2+: g⊥ = 2.21, |A⊥| = 100 G, g// = 2.00, |A//| = 64 G.

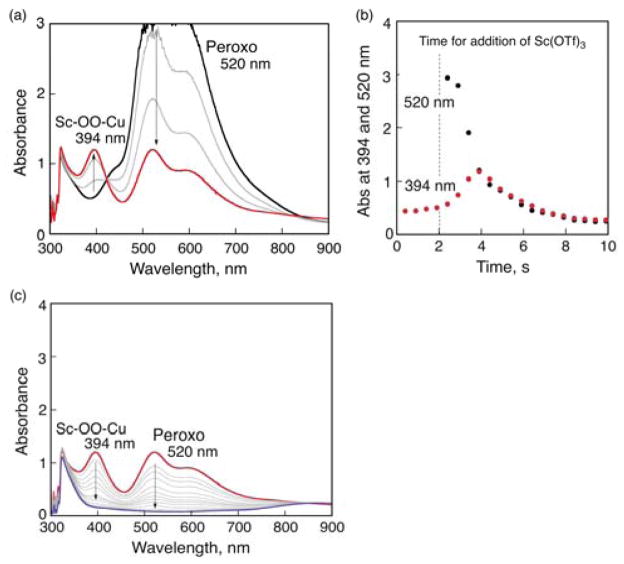

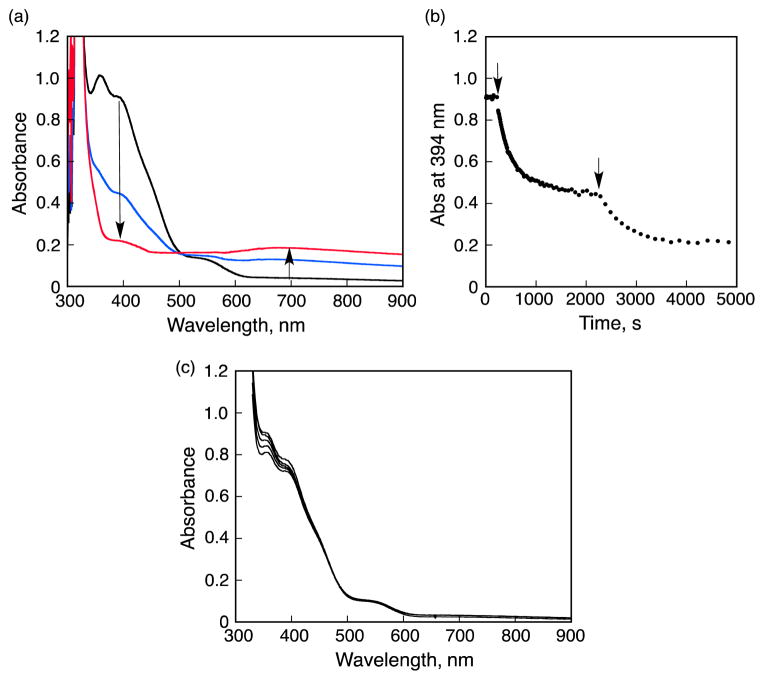

Electron transfer from Fc* to 1 is followed by the well-established nearly diffusion controlled binding of O2 to [(tmpa)CuI]+ producing superoxo complex ([(tmpa)CuII-(O2)]+) that further rapidly reacts with [(tmpa)CuI]+ to afford the peroxo complex (trans–μ–1,2–peroxo-dicopper complex ([(tmpa)CuII(O2)CuII(tmpa)]2+) (Figure 6), where the absorption band at 520 nm due to the peroxo compelex was observed by the reaction of [(tmpa)CuI]+ with O2 at 213 K.24a,26 The addition of one equiv of Sc(OTf)3 (2 mM) to an acetone solution of the peroxo complex resulted in disappearance of the absorption band due to the peroxo complex, accompanied by appearance of the absorption band at 394 nm, which is tentatively assigned to the Sc3+-bound peroxo complex, [(tmpa)CuII(O2)-Sc(OTf)3]2+; the conversion exhibits an isosbestic point (Figures 6a and 6b). At prolonged reaction times, absorption bands at both 394 and 520 nm decayed to yield [(tmpa)CuII]2+ (blue line in Figure 6c) and [Sc3+(O22−)]+.

Figure 6.

(a,c) UV-vis absorption spectral change in the reaction of [(tmpa)CuI]+ (2.0 mM) with O2 in O2-saturated acetone (black), followed by addition of Sc(OTf)3 (2.0 mM) to the resulting solution at 213 K (red) at (a) 0–4 s and (c) 4–10 s time delays. (b) Absorption time profiles at 394 nm due to the Sc3+-bound peroxo complex, [(tmpa)CuII(O2)Sc(OTf)3]2+ and 520 nm due to [(tmpa)CuII(O2)CuII(tmpa)]2+. Sc(OTf)3 was added at 2 s time delay.

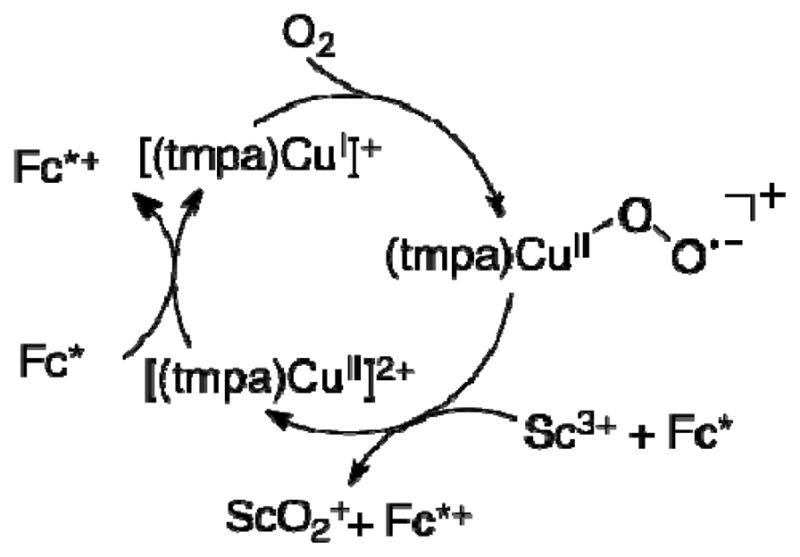

Based on the results described above, the catalytic cycle of the two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1 in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 is proposed as shown in Scheme 1. Electron transfer from Fc* to 1 is the rate-determining step to produce Fc*+ and [(tmpa)CuI]+, which rapidly reacts with O2 to produce the superoxo complex ([(tmpa)CuII(O2)]+). There are two pathways of the further reaction of [(tmpa)CuII(O2)]+. One is the reaction of [(tmpa)CuII(O2)]+ with [(tmpa)CuI]+ to produce the peroxo complex ([(tmpa)CuII(O2)CuII(tmpa)]2+) which reacts with Sc3+ to yield [(tmpa)CuII]2+ and [Sc3+(O22−)]+ (Figure 6). In such a case, the catalytic rate constant would be the same as the rate constant of electron transfer from Fc* to [(tmpa)CuII]2+ (kcat = ket). Because kcat = 2ket (vide supra), the superoxo complex ([(tmpa)CuII(O2)]+) may be rapidly reduced by Fc* with Sc3+ to produce Fc*+ and [Sc3+(O22−)]+, accompanied by regeneration of [(tmpa)CuII]2+ (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

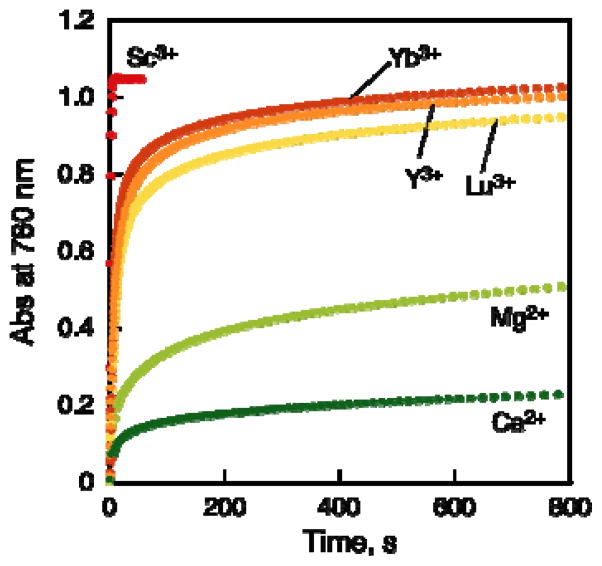

When Sc(OTf)3 was replaced by trivalent metal trifates such as Yb(OTf)3, Y(OTf)3 and Lu(OTf)3, which are weaker Lewis acid than Sc(OTf)3,38–40 the catalytic reactivity of the two-electon reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1 becomes lower than that the case of Sc(OTf)3 as shown in Figure 7. Di-valent metal triflates such as Mg(OTf)2 and Ca(OTf)2, which are still weaker Lewis acid than trivalent metal triflates,39–42 exhibited lower reactivity and the reaction was stopped before completion (Figure 7). Thus, strong Lewis acidity of metal ions is required for the efficient catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with 1.

Figure 7.

Time courses of absorbance at 780 nm due to Fc*+ in the two-electron reduction of O2 (11 mM) by Fc* (2.0 mM) with metal triflates [Sc(OTf)3, Yb(OTf)3, Y(OTf)3, Lu(OTf)3, Mg(OTf)2, and Ca(OTf)2] (2.0 mM) catalyzed by 1 (40 μM) in acetone at 298 K.

When Fc* was replaced by a weaker one-electron reductant such as 1,1′-dimethylferrocene (Me2Fc), no electron tranfser from Me2Fc (Eox = 0.28 V vs SCE) to 1 (Ered = −0.05 V vs SCE) occurred, leading to no catalytic reduction of O2 in the presence of Sc(OTf)3. Thus, we examined the catalytic reduction of O2 by Me2Fc in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 using a copper(II) complex which has a more positive Ered value than 1 (vide infra).

Catalytic Two-Electron Reduction of O2 by Me2Fc with 2 in the Presence of Sc(OTf)3

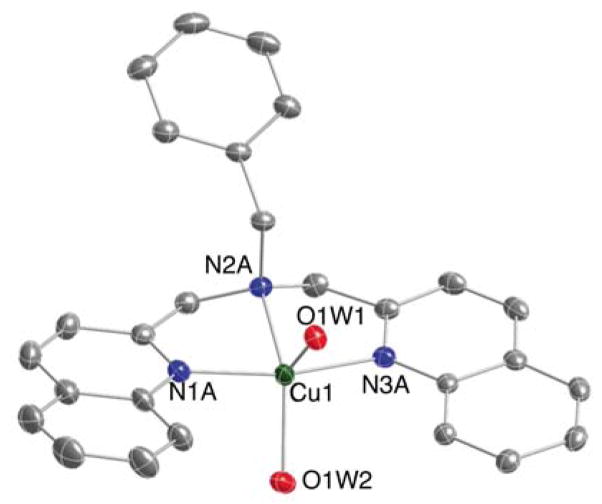

Pyridyl ligand alterations which introduce steric effects are known to result in a decrease in the donor ability to a Cu(II) center, which causes a positive shift in the redox potential of Cu(II) complexes.29 In order to use milder reductants for the reduction of dioxygen, we synthesized [(BzQ)CuII](ClO4)2 (2) as a potential catalyst. Complex 2 was generated by the addition of BzQ to Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O in MeOH and characterized by elemental analysis. Recrystallization of 2 from acetone/pentane afforded crystals suitable for X-ray structure determination; the structure of 2 is shown in Figure 8.43 The steric effect of quinoline ligand is recognized as the elongated Cu-N bonds as compared with those of [(tmpa)CuII]2+.

Figure 8.

Displacement ellispoid plot (50% probability level)of one crystallographically independent cation of [CuII(BzQ)(H2O)2](ClO4)2 • 2.33(C3H6O) BzQCuII; the two remaining cations, the ClO4− counteranions, and the lattice acetone solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances: Cu1-N1A,1.9950(14) Å; Cu1-N2A, 2.0494(14) Å; Cu1-N3, 1.9958(14) Å; Cu1-O1W1, 2.1934(12) Å Cu1-O1W2 2.0002 (13). Selected bond angles: N1A-Cu1-N3A, 165.60(6)°; N1A-Cu1-N2A, 83.21(6)°; N2A-Cu1-N3A, 83. 82.39(6)°; N1A-Cu1-O1W1, 90.69(5)°; O1W1-Cu1-O1W2, 108.97(5)°; N2A-Cu1-O1W2, 141.95(6)°.

The Ered value of 2 was determined to be 0.44 V vs SCE, which is much more positive than that of 1 (−0.05 V vs SCE), thus the two-electon reduction of O2 by Me2Fc became possible using 2 as a catalyst in the presence of Sc(OTf)3 in acetone at 298 K (eq 5).

| (5) |

The stoichiomety is the same as in eq 2, where one equiv of Sc3+ was consumed for formation of two equiv of Me2Fc+ (Figure S3). Ferrocene itself can also be used to reduce O2 to [Sc3+(O22−)]+ with 2 and Sc(OTf)3 although the rate is slower than that of Me2Fc because of the higher Eox value of Fc (0.37 V vs SCE) than that of Me2Fc (Eox = 0.28 V vs SCE).

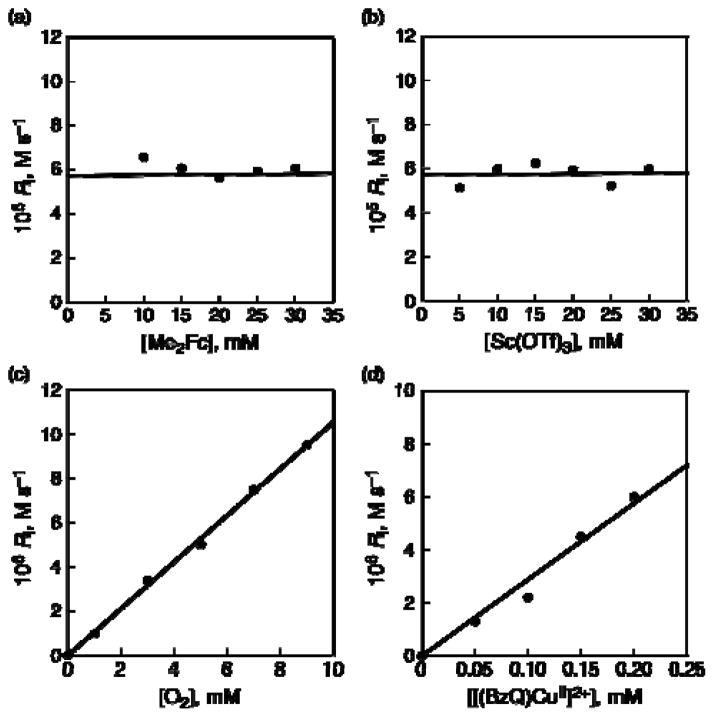

The rate of formation of Me2Fc+ obeyed pseudo-zero-order kinetics as shown in Figure 9a, where the inital rate of formation of Me2Fc+ (Ri) is independent of concentration of Me2Fc. Ri is also independent of concentration of Sc3+ (Figure 9b), whereas Ri is proportional to concentrations of O2 and 2 as shown in Figure 9c and 9d, respectively. Thus, the rate of formation of the two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc with 2 in the presence of large excess Sc(OTf)3 is given by eq 6,

Figure 9.

(a) Plot of the initial rate of formation of Me2Fc+ vs [Me2Fc] in the two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc with Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) catalyzed by 2 (0.2 mM) in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K. (b) Plot of the initial rate of formation of Me2Fc+ vs [Sc(OTf)3] in the two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc (10 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 catalyzed by 2 (0.20 mM) in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K. (c) Plot of kobs vs [O2] for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc (10 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) catalyzed by 2 (0.2 mM) in acetone at 298 K. (d) Plot of kobs vs [2] for the two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc (10 mM) with Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) catalyzed by 2 in saturated ([O2] = 11 mM) acetone at 298 K.

| (6) |

where k′cat is the the second-order catalytic rate constant.

Because the catalytic rate is proportional to concentrations of O2 and 2, but independent of concentrations of Me2Fc or Sc3+, the the rate-determining step in the catalytic cycle is the reaction of [(BzQ)CuI]+ with O2. In such a case, 2 is converted to [(BzQ)CuI]+ during the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 by Me2Fc with 2. This was confirmed by disappearace of the EPR spectrum of 2 measured during the catalysis as shown in Figure 10, where the EPR signal due to 2 (black line) is converted to the CuI complex, which is EPR silent (red line).

Figure 10.

EPR spectra of [[(BzQ)CuII]2+] (2) (0.10 mM) (black line) observed at 77 K, [[(BzQ)CuI]+] (0.05 mM) produced during the catalytic reduction of oxygen (2.2 mM) in the presence of Me2Fc (10 mM) and Sc(OTf)3 (10 mM) (red line).

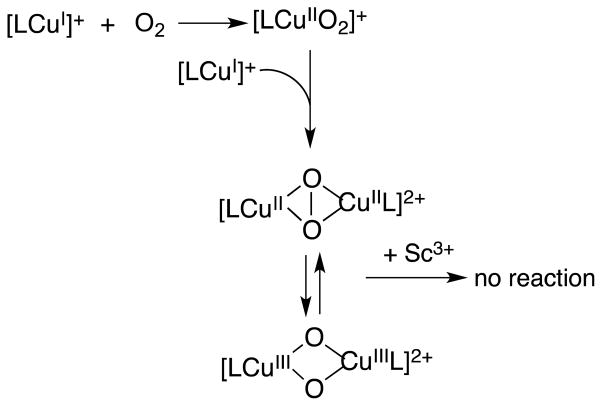

The reaction of the CuI complex of 2 with O2 was previously reported to afford copper(II)-oxygen intermediates different than that known for the case of 1, that are a (η2:η2-peroxo)dicopper(II) complex (λmax = 362 and 535 nm) plus a bis(μ-oxo)dicopper(III) species (λmax = 394 nm) (see Figure 11a, black line); the mixture had been characterized by resonance Raman spectroscopy.29 The addition of 2 equiv HOTf to an acetone solution of the peroxo and bis-μ-oxo complexes resulted in the decomposition of the Cu-O2 species to release H2O2 (Figure 11b). In contrast, the addition of Sc(OTf)3 to an acetone solution of the peroxo and bis-μ-oxo complexes resulted in little change in absorption bands of the Cu-O2 intermediates (Figure 11c), indicating that these complexes are stable against Sc3+ (Scheme 2).

Figure 11.

(a) UV-vis spectral changes observered upon the addition of 2 eq of HOTf (4.0 mM) to the mixture of the μ-η2-η2-(side-on) peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complex and the bis-μ-oxo dinuclear copper(III) complex. (b) Absorption time profiles at 394 nm due to the addition of HOTf (4.0 mM) to to the mixture of the μ-η2-η2-(side-on) peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complex and the bis-μ-oxo dinuclear copper(III) complex. (c) UV-vis spectral changes observered upon the addition of Sc(OTf)3 (4.0 mM) to the mixture of the μ-η2-η2-(side-on) peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complex and the bis-μ-oxo dinuclear copper(III) complex.

Scheme 2.

Thus, once the μ-η2-η2-(side-on) peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complex and the bis-μ-oxo dinuclear copper(III) complex are formed via the superoxo complex, no catalytic reduction of O2 by Me2Fc would occur with 2 in the presence of Sc(OTf)3. Under the catalytic conditions, the superoxo complex is reduced by Me2Fc in the presence of Sc3+ to yield Me2Fc+ and Sc(O2)+, accompanied by regeneration of 2 without formation of the μ-η2-η2-(side-on) peroxo dinuclear copper(II) complex or the bis-μ-oxo dinuclear copper(III) complex as shown in Scheme 3. The rate-determining step in Scheme 3 is the reaction of [(BzQ)CuI]+ with O2 to produce the superoxo complex, when the catalytic rate is proportional to concentrations of O2 and 2, but independent of concentrations of Me2Fc or Sc3+ as observed in Figure 9.

Scheme 3.

Conclusion

The four-electron reduction of O2 by Fc* with a mononuclear complex [(tmpa)CuII](ClO4)2 (1) in the presence of a proton source (HOTf) was changed to the two-electron reduction of O2 by replacing Brønsted acids by Sc(OTf)3 that acts as a strong Lewis acid. The rate-determining step of the catalytic cycle is found to be electron transfer from Fc* to O2. When 1 was replaced by a copper(II) complex [(BzQ)CuII](ClO4)2 (2), which has a more positive reduction potential as compared with 1, the catalytic two-electron reduction of O2 is made possible by using a weaker one-electron reductant than Fc* such as Me2Fc and Fc. In this case, the rate-determining step is the reaction of [(BzQ)CuI]+ with O2 to produce the superoxo complex. The Lewis acid-induced change in the stoichiometry of the catalytic O2 reduction provides a new way to control this important biological or chemical “fuel-cell” reaction which can produce either hydrogen peroxide or water.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Advanced Low Carbon Technology Research and Development (ALCA) program from Japan Science Technology Agency (JST) to S.F., the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS: Grants 20108010 to S.F. and 26620154 and 26288037 to K.O.) sponsored by the MEXT (Japan), and by KOSEF/MEST through the WCU Project (R31-2008-000-10010-0). K.D.K. also acknowledges support from the USA National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Spectral and kinetic analytical data, theoretical calculation data (Figures S1–S6), and X-ray crystallographic data (pdf); crystallographic file (cif). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Hadt RG, Tian L. Chem Rev. 2014;114:3659. doi: 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kosman DJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:15. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Battaini G, Granata A, Monzani E, Gullotti M, Casella L. Adv Inorg Chem. 2006;58:185. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rosenzweig AC. Nat Chem. 2009;1:684. doi: 10.1038/nchem.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humphreys KJ, Mirica LM, Wang Y, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4657–4663. doi: 10.1021/ja807963e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee A, Smirnov VV, Lanci MP, Brown DE, Shepard EM, Dooley DM, Roth JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9459–9473. doi: 10.1021/ja801378f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuirl MA, Dooley DM. Copper Proteins with Type 2 Sites. In: King RB, editor. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. 2. II. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester: 2005. pp. 1201–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Blanford CF, Heath RS, Armstrong FA. Chem Commun. 2007:1710. doi: 10.1039/b703114a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mano N, Soukharev V, Heller A. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:11180–11187. doi: 10.1021/jp055654e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Pereira MM, Santana M, Teixeira M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1505:185. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Winter M, Brodd RJ. Chem Rev. 2004;104:4245. doi: 10.1021/cr020730k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ferguson-Miller S, Babcock GT. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2889. doi: 10.1021/cr950051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S, Mills DA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.062003.101730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kaila VRI, Verkhovsky MI, Wikström M. Chem Rev. 2010;110:7062. doi: 10.1021/cr1002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:187. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S. Chem Lett. 2008;37:808. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Collman JP, Devaraj NK, Decréau RA, Yang Y, Yan YL, Ebina W, Eberspacher TA, Chidsey CED. Science. 2007;315:1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1135844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collman JP, Decréau RA, Lin H, Hosseini A, Yang Y, Dey A, Eberspacher TA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Collman JP, Ghosh S, Dey A, Decréau RA, Yang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5034. doi: 10.1021/ja9001579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Rosenthal J, Nocera DG. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:543. doi: 10.1021/ar7000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chang CJ, Loh ZH, Shi C, Anson FC, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10013. doi: 10.1021/ja049115j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dogutan DK, Stoian SA, McGuire R, Schwalbe M, Teets TS, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:131. doi: 10.1021/ja108904s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Teets TS, Cook TR, McCarthy BD, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8114. doi: 10.1021/ja201972v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Halime Z, Kotani H, Li Y, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104698108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Gros CP, Guilard R. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10441. doi: 10.1021/ja048403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Tokuda Y, Gros CP, Guilard R. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:17059. doi: 10.1021/ja046422g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fukuzumi S, Mandal S, Mase M, Ohkubo K, Park H, Benet-Buchholz J, Nam W, Llobet A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9906. doi: 10.1021/ja303674n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. Inorg Chem. 1989;28:2459. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:653. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuzumi S, Mochizuki S, Tanaka T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1989:391. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vielstich W, Lamm A, Gasteiger HA. Handbook of fuel cells: fundamentals, technology, and applications. Wiley; Chichester, U.K., Hoboken, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Zagal JH, Griveau S, Silva JF, Nyokong T, Bedioui F. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:2755. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li W, Yu A, Higgins DC, Llanos BG, Chen Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17056. doi: 10.1021/ja106217u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Gewirth AA, Thorum MS. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:3557. doi: 10.1021/ic9022486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stambouli AB, Traversa E. Renew Sust Energy Rev. 2002;6:295. [Google Scholar]; (c) Markovic NM, Schmidt TJ, Stamenkovic V, Ross PN. Fuel Cells. 2001;1:105. [Google Scholar]; (d) Steele BCH, Heinzel A. Nature. 2001;414:345. doi: 10.1038/35104620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asahi M, Yamazaki S-i, Itoh S, Ioroi T. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:10705. doi: 10.1039/c4dt00606b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Honda T, Kojima T, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4196. doi: 10.1021/ja209978q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mase K, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2800. doi: 10.1021/ja312199h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Disselkamp RS. Energy Fuels. 2008;22:2771. [Google Scholar]; (b) Disselkamp RS. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010;35:1049. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Fukuzumi S, Yamada Y, Karlin KD. Electrochim Acta. 2012;82:493. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamada Y, Fukunishi Y, Yamazaki S, Fukuzumi S. Chem Commun. 2010;46:7334. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamada Y, Yoshida S, Honda T, Fukuzumi S. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4:2822. [Google Scholar]; (d) Shaegh SAM, Nguyen NT, Ehteshami SMM, Chan SH. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:8225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Zhang J, Anson FC. J Electroanal Chem. 1992;341:323. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J, Anson FC. J Electroanal Chem. 1993;348:81. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J, Anson FC. Electrochim Acta. 1993;38:2423. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lei Y, Anson FC. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:5003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Weng YC, Fan FRF, Bard AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17576. doi: 10.1021/ja054812c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thorum MS, Yadav J, Gewirth AA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:165. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) McCrory CCL, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP, Chidsey CED. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:12641. doi: 10.1021/jp076106z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McCrory CCL, Devadoss A, Ottenwaelder X, Lowe RD, Stack TDP, Chidsey CED. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3696. doi: 10.1021/ja106338h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Pichon C, Mialane P, Dolbecq A, Marrot J, Riviere E, Keita B, Nadjo L, Secheresse F. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:5292. doi: 10.1021/ic070313w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dias VLN, Fernandes EN, da Silva LMS, Marques EP, Zhang J, Marques ALB. J Power Sources. 2005;142:10. [Google Scholar]; (c) Losada J, del Peso I, Beyer L. Inorg Chim Acta. 2001;321:107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Thorseth MA, Tornow CE, Tse ECM, Gewirth AA. Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:130. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thorseth MA, Letko CS, Rauchfuss TB, Gewirth AA. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:6158. doi: 10.1021/ic200386d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Fukuzumi S, Kotani H, Lucas HR, Doi K, Suenobu T, Peterson RL, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6874. doi: 10.1021/ja100538x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Tahsini L, Lee YM, Ohkubo K, Nam W, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7025. doi: 10.1021/ja211656g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tahsini L, Kotani H, Lee YM, Cho J, Nam W, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. Chem–Eur J. 2012;18:1084. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Das D, Lee YM, Ohkubo K, Nam W, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4018. doi: 10.1021/ja312256u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das D, Lee Y-M, Ohkubo K, Nam W, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2825. doi: 10.1021/ja312523u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakuda S, Peterson RL, Ohkubo K, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2825. doi: 10.1021/ja3125977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armarego WLF, Chai CLL. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. 5. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Schopfer MP, Puiu SC, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:1404. doi: 10.1021/ic901431r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kryatov SV, Taktak S, Korendovych IV, Rybak-Akimova EV, Kaizer J, Torelli S, Shan X, Mandal S, MacMurdo V, Mairata i Payeras A, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2005;44:85. doi: 10.1021/ic0485312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunishita A, Osako T, Tachi Y, Teraoka J, Itoh S. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2006;79:1729. [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Mair RD, Graupner AJ. J Anal Chem. 1964;36:194. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Kuroda S, Tanaka T. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann CK, Barnes KK. Electrochemical Reactions in Nonaqueous Systems. Marel Dekker; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:270. [Google Scholar]; (b) Curtiss LA, McGrath MP, Blaudeau J-P, Davis NE, Binning RC, Jr, Radom L. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:6104. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Yanai T, Tew DP, Handy NC. Chem Phys Lett. 2004;393:51. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tawada Y, Tsuneda T, Yanagisawa S, Yanai T, Hirao K. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:8425. doi: 10.1063/1.1688752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takaichi J, Ohkubo K, Sugimoto H, Nakano M, Usa D, Maekawa H, Fujieda N, Nishiwaki N, Seki S, Fukuzumi S, Itoh S. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:2438. doi: 10.1039/c2dt32413j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennington R, II, Keith T, Millam J, Eppinnett K, Hovell WL, Gilliland R. Gaussview. Semichem, Inc; Shawnee Mission, KS: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Fukuzumi S, Patz M, Suenobu T, Kuwahara Y, Itoh S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1605. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawashima T, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:3344. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00916d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K. Chem–Eur J. 2000;6:4532. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001215)6:24<4532::aid-chem4532>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10270. doi: 10.1021/ja026613o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuzumi S. Prog Inorg Chem. 2009;56:49. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K, Morimoto Y. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:8472. doi: 10.1039/c2cp40459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morimoto Y, Kotani H, Park J, Lee YM, Nam W, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:403. doi: 10.1021/ja109056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.When a weak Lewis acid, Mg(OTf)2 was applied to the catalyst for the O2 reduction reaction with Fc*, the absorption changes for formation of Fc*+ were significantly smaller as compared with the case of Sc(OTf)3 as shown in Figure 7.

- 43.The crystal structure of a similar copper(II) complex of BzQ type ligand have already been reported. Osako T, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Cramer CJ, Itoh S. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:581. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0005-5.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.