Abstract

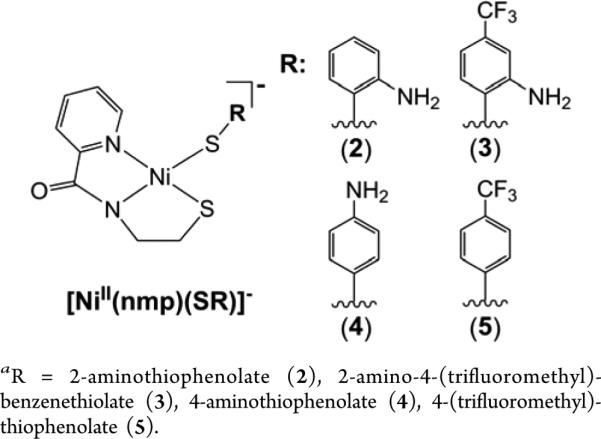

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyzes the disproportionation of superoxide (O2• −) into H2O2 and O2(g) by toggling through different oxidation states of a first-row transition metal ion at its active site. Ni-containing SODs (NiSODs) are a distinct class of this family of metalloenzymes due to the unusual coordination sphere that is comprised of mixed N/S-ligands from peptide-N and cysteine-S donor atoms. A central goal of our research is to understand the factors that govern reactive oxygen species (ROS) stability of the Ni–S(Cys) bond in NiSOD utilizing a synthetic model approach. In light of the reactivity of metal-coordinated thiolates to ROS, several hypotheses have been proffered and include the coordination of His1-Nδ to the Ni(II) and Ni(III) forms of NiSOD, as well as hydrogen bonding or full protonation of a coordinated S(Cys). In this work, we present NiSOD analogues of the general formula [Ni(N2S)(SR′)]−, providing a variable location (SR′ = aryl thiolate) in the N2S2 basal plane coordination sphere where we have introduced o-amino and/or electron-withdrawing groups to intercept an oxidized Ni species. The synthesis, structure, and properties of the NiSOD model complexes (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] (2), (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2-p-CF3)] (3), (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-NH2)] (4), and (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-CF3)] (5) (nmp2− = dianion of N-(2-mercaptoethyl)picolinamide) are reported. NiSOD model complexes with amino groups positioned ortho to the aryl-S in SR′ (2 and 3) afford oxidized species (2ox and 3ox) that are best described as a resonance hybrid between Ni(III)-SR and Ni(II)-•SR based on ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis), magnetic circular dichroism (MCD), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopies, as well as density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The results presented here, demonstrating the high percentage of S(3p) character in the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the four-coordinate reduced form of NiSOD (NiSODred), suggest that the transition from NiSODred to the five-coordinate oxidized form of NiSOD (NiSODox) may go through a four-coordinate Ni-•S(Cys) (NiSODox-Hisoff) that is stabilized by coordination to Ni(II).

INTRODUCTION

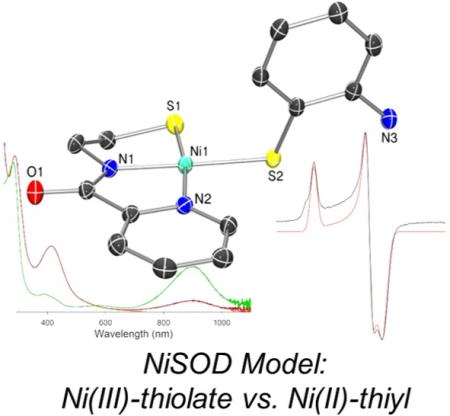

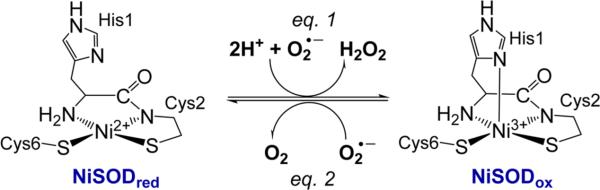

Aerobic organisms utilize superoxide dismutase (SOD) metalloenzymes in their defense against the free radical superoxide (O2• −), which if unregulated plays a role in a variety of disease states.1–8 The most recently discovered class of SODs are the nickel-containing SODs (NiSODs), which utilize Ni in a mixed nitrogen and thiolate coordination environment to catalyze the disproportionation of O2• − to H2O2 and O2 by cycling through Ni(II/III) redox states (see eqs 1 and 2 in Figure 1).9 X-ray crystal structures of NiSOD from two separate Streptomyces strains confirm two distinct metal coordination geometries.10–12 In the reduced form (NiSODred), the low-spin (S = 0) Ni(II) ion lies in a square-planar N2S2 environment composed of the N-terminal amine of His1, the deprotonated peptido-N of Cys2, and two thiolato-S from Cys2 and Cys6 (Figure 1). The oxidized form (NiSODox) contains the same ligand set, but the S = ½ Ni(III) ion is five-coordinate and additionally bound to the imidazole-Nδ of His1 resulting in a Ni–N3S2 square-pyramidal geometry (Figure 1).10–12

Figure 1.

Structures of the NiSOD active site and the corresponding SOD half-reactions.

Questions concerning the enzyme's unusual N/S coordination sphere, particularly its stability toward O2 and reactive oxygen species (ROS), in light of the reactive Ni–S(Cys) bonds,13 and the catalytic mechanism have prompted researchers to develop maquette-based,14–20 tripeptide,21–24 and low molecular weight25–38 analogues that seek to replicate NiSOD's structure and/or function.39,40 Indeed, several experimental and theoretical efforts have suggested that the mixed peptide-N/amine-N ligation serves as one key factor to promote greater Ni-character in the redox-active molecular orbital of NiSOD, in particular for the Ni(II) or NiSODred state, thus preventing unwanted S-oxidation/oxygenation.10,30,41 For example, a direct electronic structure comparison of two planar Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes (NiSODred models) with diamine/dithiolate versus amine/carboxamide/dithiolate donors revealed a significant increase in Ni character of the Ni(dπ)–S(pπ) antibonding highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) upon introduction of the carboxamide, i.e., 18% Ni, 74% S for diamine; 33% Ni, 50% S for amine/carboxamide.30 Direct density functional theory (DFT) computations on truncated versions of NiSODred clearly demonstrated more S(pπ) character than Ni(dπ) character in the π-antibonding HOMO (25% Ni, 67% S) and HOMO–1 (37% Ni, 44% S).10 Taken together, these results support a highly covalent Ni–S bond in NiSODred that, nonetheless, still has significant S-character in the HOMO even with inclusion of the Ni–Npeptide bond. Thus, the enzyme has evolved in such a way to promote Ni-based oxidation via the destabilization of the Ni(dπ) orbitals. This proposal has been verified by examining the electronic structure of the DFT-generated hypothetical four-coordinate (4C) planar version of NiSODox, namely NiSODox-Hisoff, that revealed a HOMO composition of 58% Ni(dπ) and 24% S(pπ).10 On the other hand, the actual NiSODox HOMO is predominantly Ni in character with the unpaired electron occupying the Ni dz2 orbital, as verified by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Thus, the electronic structural changes from NiSODred → NiSODox-Hisoff → NiSODox gradually move toward more Ni-character in the HOMO. This analysis begs the question as to what prevents NiSODred from undergoing deleterious S-based redox chemistry upon conversion to NiSODox. Could a Ni-stabilized •S(Cys) be traversed in such a conversion? To date, few low molecular weight analogues of NiSOD with mixed peptide-N/amine-N/thiolate-S coordination have been shown to achieve catalytic O2• − disproportionation. Many such complexes are prone to undergo irreversible S-based rather than Ni-based oxidation although in some cases, a transient Ni(III) species has been trapped and observed by EPR spectroscopy.35,42,43

The work presented here adopts the methodology developed by our group for synthesizing asymmetric, 4C planar Ni–N2S2 models of NiSOD employing the nmp2− ligand (see Chart 1; nmp2− = dianion of N-(2-mercaptoethyl)picolinamide).32 Synthesis of such models was achieved through splitting of a proposed S,S-bridged dimer [Ni2(nmp)2] with exogenously added thiolate ions or Sexo (where exo refers to the exogenously added monodentate S-ligand) that afforded a variety of Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes. We now report this S,S-bridged species to be the tetramer [Ni4(nmp)4] (1). The use of Sexo to complete the N2S2 coordination sphere is synthetically novel in that it provides a specific point of control for modeling Cys6 (see Figure 1) at a site-differentiated location in the coordination sphere. In this way, the electronic properties of the complex can be evaluated and tuned by changing Sexo. Prior work on Ni(II)-nmp systems focused on synthetic methodology32 and the electronic influence of second-sphere N–H···S hydrogen bonds (H-bonds).33 None of these complexes afforded a stable oxidized species. Instead, oxidation took place at Sexo to afford the disulfide of Sexo (through a transient thiyl radical) and 1 in quantitative yields. We hypothesized that enforcing a potential N-donor near the Ni center and/or decreasing the basicity of Sexo would allow us to intercept a Ni(III) or Ni(II)-thiyl species. Indeed, the presence of Naxial ligands has proven beneficial in spectroscopically observing other Ni(III)-N2S2 complexes related to NiSOD.36,44 Thus, the primary objective of this work is to gauge the impact of electronically deficient Sexo and Naxial-tethered Sexo donors on the redox properties of the corresponding NiSOD model complexes. The synthesis, structure, properties, and reactivity of the following Ni–N2S2 complexes will be described: (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] (2), (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2-p-CF3)] (3), (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-NH2)] (4), and (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-CF3)] (5) (Chart 1). The NiSOD model complexes with amino groups positioned ortho to the aryl-S (2 and 3) afforded oxidized species that are best described as a resonance hybrid between Ni(III)-(−SR) and Ni(II)-(•SR) and are the first examples of the room temperature (RT) observation of Ni-stabilized thiyl radicals with relatively long (hours) lifetimes.

Chart 1.

General Structure of the [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− Complexes Reported in This Studya

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Information

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received, unless otherwise noted. Acetonitrile (MeCN), tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether (Et2O), and pentane were purified by passage through activated alumina columns of an MBraun MB-SPS solvent purification system and stored under an N2 atmosphere until use. N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) was purified with a VAC solvent purifier containing 4 Å molecular sieves and stored under N2. The ligand N-2-(mercaptoethyl)-picolinamide (nmpH2; H represents dissociable protons) and its corresponding Ni(II) complex, [Ni4(nmp)4] (1), were prepared according to the published procedure.32 All reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of N2 using Schlenk line techniques or under an atmosphere of purified N2 in an MBraun Unilab glovebox. The syntheses of Et4N+ thiolate salts from Et4NCl and the appropriate sodium thiolate were carried out according to previously published methods.45,46

Physical Methods

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected on a ThermoNicolet Model 6700 spectrophotometer running the OMNIC software. All samples were run as solid samples prepared as pressed KBr pellets. X-band (9.60 GHz) EPR spectra were obtained using a Bruker ESP 300E EPR spectrometer controlled with a Bruker microwave bridge at 10 K. The EPR was equipped with a continuous-flow liquid He cryostat and a temperature controller (ESR 9) made by Oxford Instruments, Inc. EPR spectra were simulated using the program QPOWA, as modified by J. Telser.47 Electronic absorption spectra were collected at 298 K using a Varian Model Cary-50 spectrophotometer containing a Quantum Northwest TC 125 temperature control unit. The UV-vis samples were prepared in gas-tight Teflon-lined screw cap quartz cells with an optical path length of 1 cm. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were performed with a PAR Model 273A potentiostat using a Ag/Ag+ (0.01 M AgNO3/0.1 M nBu4NPF6 electrolyte in MeCN) reference electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and a glassy carbon working milli-electrode (diameter = 2 mm). CV measurements were performed at ambient temperature using 3.5 or 8.0 mM analyte in DMF under Ar containing 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte. The “maximize stability” mode and a low-pass 5.3 Hz filter were used in the PAR PowerCV software. Analyte potentials were referenced against a 0.05–0.1 mM ferrocene standard. 1H NMR spectra were recorded in the listed deuterated solvent on a 400 MHz Bruker Model BZH 400/52 NMR spectrometer or a Varian Unity Inova 500 MHz NMR spectrometer at RT with chemical shifts internally referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS = Si(CH3)4), or the residual protio signal of the deuterated solvent.48 Low-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LR-ESI-MS) data were collected using a Bruker Model Esquire 3000 plus ion-trap mass spectrometer. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) data were collected using an Orbitrap Elite system with precision to the third decimal place. Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) and low temperature absorption data were collected using a Jasco Model J-715 spectropolarimeter, in conjunction with an Oxford Instrument SM-4000 8T magnetocryostat. The sample for these studies was prepared in a 1:4 (v/v) solvent mixture of MeCN and butyronitrile and sparged with dry O2(g) for 5 min. Glass strain contributions to the MCD signal were removed by taking the difference between spectra collected with the magnetic field aligned parallel and antiparallel to the light-propagation axis. Elemental analysis for C, H, and N was performed at QTI-Intertek in Whitehouse, NJ and ALS Environmental (formerly Columbia Analytical Services) in Tucson, AZ.

(Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] (2)

To a 6 mL DMF slurry of 1 (0.1550 g, 0.1622 mmol) was added a yellow DMF solution (2 mL) of (Et4N)(SPh-o-NH2) (0.1517 g, 0.5962 mmol) dropwise at RT. The DMF gradually took up a burgundy-red color over time. The mixture was stirred under N2 for 20 h in a 40 °C water bath. The resulting dark red, mostly homogeneous solution was filtered through Celite to remove unreacted 1, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness via short-path vacuum distillation. The resulting brown-black residue was dissolved in 5 mL of MeCN, cooled to −20 °C, and filtered through a plug of Celite. The dark red MeCN filtrate was removed under vacuum, and the residue stirred in 5 mL of Et2O overnight to afford 0.2093 g (0.3554 mmol, 60%) of an orange-red powder. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3 containing 0.05% v/v TMS, δ from TMS): 8.49 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 8.13 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.10 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.75 (t, 1H, J = 9.3 Hz), 6.48 (m, 2H), 4.81 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.45 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 3.22 (br, 9H integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+), 2.32 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 1.25 (br, 20H integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+). FTIR (KBr pellet) νmax (cm−1): 3407 (m, νNH), 3309 (m, νNH), 2974 (w), 2915 (w), 2846 (w), 1670 (m, νCO of residual DMF), 1617 (vs, νCO), 1593 (vs, νCO), 1568 (m), 1559 (m), 1475 (m), 1437 (w), 1391 (s), 1293 (w), 1172 (w), 1093 (s), 999 (m), 786 (w), 755 (m), 687 (w), 623 (w), 558 (w), 485 (w). UV-vis (MeCN, 298 K) λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 453 (7200). LR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]– calcd for C14H14N3OS2Ni, 362.0 (100.0), 364.0 (49.3), 363.0 (18.1), 365.0 (10.3), 366.0 (10.2); found: 361.9 (100.0), 363.9 (47.4), 362.9 (14.4), 364.9 (8.5), 365.8 (9.4). HR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]– calcd for C14H14N3OS2Ni, 361.994 (100.0), 363.989 (47.6), 362.996 (15.2), 364.992 (7.2), 365.986 (5.4); found: 361.994 (100.0), 363.990 (48.9), 362.997 (15.0), 364.992 (6.9), 365.986 (8.1). Anal. Calcd for C22H34N4OS2Ni·H2O·MeCN·0.5DMF: C, 52.00; H, 7.27; N, 13.08. Found: C, 51.39; H, 6.56; N, 13.21.

(Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2-p-CF3)] (3)

To a 6 mL DMF slurry of 1 (0.2380 g, 0.2490 mmol) was added a bright yellow DMF (3 mL) solution of (Et4N)(SPh-o-NH2-p-CF3) (0.3012 g, 0.9342 mmol). The solvent gradually took up a reddish-brown color over time. The mixture was stirred under N2 for 20 h in a 40 °C water bath. The resulting dark red, mostly homogeneous solution was filtered to remove unreacted 1, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness via short-path vacuum distillation. The resulting red-burgundy residue was dissolved in 5 mL of THF, cooled to −20 °C, and filtered through a plug of Celite. The dark red THF filtrate was removed under vacuum to result in a black oily material. This residue was triturated with 5 mL of Et2O or pentane overnight to afford a burgundy-black powder (0.4150 g, 0.6935 mmol, 74%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN, δ from protio solvent): 8.48 (d, 1H, J = 5.0 Hz), 8.11 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 7.83 (t, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 7.25 (t, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz), 6.69 (s, 1H), 6.60 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 5.13 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.22 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 3.15 (q, 23H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 10.0 Hz), 2.12 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 1.19 (t, 34H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 7.5 Hz). FTIR (KBr pellet) νmax (cm−1): 3407 (w,νNH), 3286 (w,νNH), 2980 (w), 2917 (w), 2849 (w), 1765 (w), 1620 (vs, νCO), 1592 (vs, νCO), 1483 (m), 1432 (m), 1329 (vs), 1102 (m), 1072 (m), 999 (w), 787 (w). UV-vis (MeCN, 298 K) λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 448 (3800). LR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]– calcd for C15H13F3N3OS2Ni, 430.0 (100), 432.0 (49.5), 431.0 (19.1), 433.0 (10.8), 434.0 (10.3); found: 429.8 (100.0), 431.8 (48.0), 430.8 (16.1), 432.8 (9.1), 433.8 (8.8). HR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]– calcd for C15H13F3N3OS2Ni, 429.981 (100.0), 431.977 (47.6), 430.984 (16.2), 432.979 (6.2), 433.974 (5.3); found: 429.982 (100.0), 431.977 (47.2), 430.985 (16.9), 432.980 (8.1), 433.974 (8.1). Anal. Calcd for C23H33F3N4OS2Ni·0.5Et2O: C, 50.18; H, 6.40; N, 9.36. Found: C, 50.10; H, 6.07; N, 9.09.

(Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-NH2)] (4)

To a 6 mL DMF slurry of 1 (0.1783 g, 0.1866 mmol) was added a pale yellow DMF solution (2 mL) of (Et4N)(SPh-p-NH2) (0.1709 g, 0.6717 mmol) dropwise at RT. The DMF solvent gradually took up a burgundy-red color over time. The mixture was stirred under N2 for 20 h in a 40 °C water bath. The resulting dark burgundy, mostly homogeneous solution was filtered through Celite to remove unreacted 1, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness via short-path vacuum distillation. The resulting brown-black residue was dissolved in 5 mL of MeCN, cooled to −20 °C, and filtered through Celite. The burgundy MeCN filtrate was removed under vacuum and the resulting black residue was stirred in 5 mL of Et2O overnight to afford 0.1741 g (0.3138 mmol, 47%) of an orange-red powder. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3 containing 0.05% v/v TMS, δ from TMS): 8.60 (d, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 7.69 (m, 4H), 7.12 (t, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 6.41 (d, 2H, J = 10.0 Hz), 3.44 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 3.37 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.31 (q, 10H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 10.0 Hz), 2.31 (t, 2H, J = 6.5, –NCH2CH2S–), 1.28 (t, 15H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 7.5 Hz). FTIR (KBr pellet) νmax (cm−1): 3315 (m,νNH), 3197 (m,νNH), 2983 (w), 2912 (w), 2841 (w), 1671 (m, νCO of residual DMF), 1616 (vs, νCO), 1592 (vs, νCO), 1486 (s), 1455 (m), 1396 (m), 1268 (w), 1174 (w), 1096 (s), 1002 (w), 817 (w), 794 (w), 766 (w), 718 (w), 704 (w), 688 (w), 631 (w). UV-vis (MeCN, 298 K), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 458 (6100). LR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]− calcd for C14H14N3OS2Ni, 362.0 (100.0), 364.0 (49.3), 363.0 (18.1), 365.0 (10.3), 366.0 (10.2); found: 361.9 (100.0), 363.9 (43.8), 362.9 (19.1), 364.9 (10.0), 365.9 (7.0). HR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]− calcd for C14H14N3OS2Ni, 361.994 (100.0), 363.989 (47.6), 362.996 (15.2), 364.992 (7.2), 365.986 (5.4); found: 361.994 (100.0), 363.989 (47.3), 362.997 (15.5), 364.992 (6.5), 365.986 (8.0). Anal. Calcd for C22H34N4OS2Ni·H2O·0.5THF·0.1DMF: C, 52.61; H, 7.40; N, 10.35. Found: C, 52.74; H, 7.91; N, 10.37.

(Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-CF3)] (5)

To a 6 mL DMF slurry of 1 (0.0849 g, 0.0888 mmol) was added a pink DMF solution of (Et4N)(SPh-p-CF3) (0.1023 g, 0.3328 mmol) dropwise at RT. The solvent gradually took up a burgundy-red color over time. The mixture was stirred under N2 for 20 h in a 40 °C water bath. The resulting dark red, mostly homogeneous solution was filtered through Celite to remove unreacted 1, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness via short-path vacuum distillation. The resulting brown-black residue was dissolved in 5 mL of THF, cooled to −20 °C, and filtered through a plug of Celite. The dark red THF filtrate was removed under vacuum and the resulting dark black residue was stirred in 5 mL of Et2O overnight to afford 0.0858 g (0.157 mmol, 47%) of a burgundy-black sticky material. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN, δ from protio solvent): 8.53 (d, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 8.09 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.83 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.52 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.24 (t, 1H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.17 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.23 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz, –NCH2CH2S–), 3.15 (q, 14H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.16 (br, 4H, integrates high due to overlap with H2O, –NCH2CH2S–), 1.19 (t, 20H, integrates high due to the presence of excess Et4N+, J = 8.0 Hz). FTIR (KBr pellet) νmax (cm−1): 2981 (w), 2914 (w), 2839 (w), 1670 (s, νCO of residual DMF), 1623 (vs, νCO), 1593 (vs, νCO), 1560 (m), 1486 (m), 1458 (w), 1385 (s), 1323 (s), 1274 (w), 1256 (w), 1183 (w), 1155 (w), 1086 (s), 1058 (m), 1009 (w), 826 (w), 761 (w), 686 (w). UV-vis (MeCN, 298 K), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 432 (4600). LR-ESI-MS (m/z): [M–Et4N]− calcd for C15H12F3N2OS2Ni, 415.0 (100.0), 417.0 (49.4), 416.0 (18.7), 418.0 (10.6), 419.0 (10.3); found: 414.8 (100.0), 416.8 (48.0), 415.8 (16.8), 417.8 (8.5), 418.7 (8.9). HR-ESI-MS measured with Na+ salt (m/z): calcd for C15H12F3N2OS2Ni, 414.970 (100.0), 416.966 (47.6), 415.973 (16.2), 417.968 (6.2), 418.963 (5.3); found: 414.970 (100.0), 416.965 (47.3), 415.973 (15.8), 417.968 (7.1), 418.962 (8.1). Anal. Calcd for C23H32F3N3OS2Ni: C, 50.56; H, 5.90; N, 7.69. Found: C, 49.41; H, 5.99; N, 6.29. A reasonable fit to C, H, N could not be obtained due to the oily nature of the resulting product.

X-ray Crystallographic Data Collection and Structure Solution and Refinement

Red needlelike crystals of 1 were grown by Et2O layering over a CD3OD solution of Na3[{Ni-(nmp)}3(BTAS)] (BTAS3− is the trianion of N1,N3,N5-tris(2-mercaptoethyl)benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide) at RT under aerobic atmosphere. Dark red bladelike crystals of 2 were grown by slow vapor diffusion of Et2O into a solution of 2 in DMF:C6H5Cl (1:1) at RT. In addition, dark red blade crystals of 4 were grown by slow vapor diffusion of Et2O into a solution of 4 in THF:DMF (~4:1) at RT. Suitable crystals were mounted on a glass fiber. The X-ray intensity data were measured at 100 K on a Bruker SMART APEX II X-ray diffractometer system with graphite-monochromatic Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), using ω-scan technique controlled by the SMART software package.49 The data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects50 and integrated with the manufacturer's SAINT software. Absorption corrections were applied with the program SADABS.51 Subsequent structure refinement was performed using the SHELXTL 6.1 solution package operating on a Pentium computer. The structure was solved by direct methods using the SHELXTL 6.1 software package.52,53 All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically.54 Non-hydrogen atoms were located from successive difference Fourier map calculations. In the structure of 1, two carbon atoms (C1 and C2) and one oxygen atom (O1) were found disordered in two sets of each: labeled for the carbon atoms as C1 and C2 (one set) and C1′ and C2′ (other set); and labeled for the oxygen atom as O1 (one set) and O1′ (other set), respectively. The two sets for the atoms (C1 and C2) were divided using the PART commands and proper restraints. The set of C1 and C2 has 46% occupancy while the other (C1′ and C2′) has 54% occupancy. The occupancies for O1 and O1′ are set at 50% each. The structure of 4 has two distinct, but chemically indistinguishable Ni complexes. Selected data and metric parameters for complexes 1, 2, and 4 are summarized in Table S1 in the Supporting Information and Table 1, respectively. Perspective views of the complexes were obtained using ORTEP.55

Table 1.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Bond Angles (deg) for [Ni4(nmp)4] (1), (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] (2), and (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-NH2)] (4)

| 1 | 2 | 4a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths (Å) | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 1.866(4) | 1.8750(16) | 1.8698(14) |

| Ni(1)–N(2) | 1.951(4) | 1.9418(16) | 1.9450(14) |

| Ni(1)–S(1) | 2.1500(12) | 2.1386(6) | 2.1474(5) |

| Ni(1)–S(2) | 2.2170(12) | 2.2173(6) | 2.2160(5) |

| Bond Angles (deg) | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(2) | 83.47(16) | 83.36(7) | 83.12(6) |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–S(1) | 87.33(12) | 88.62(5) | 87.88(4) |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–S(2) | 178.39(14) | 178.74(5) | 177.51(4) |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–S(1) | 168.73(12) | 171.97(5) | 168.97(4) |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–S(2) | 95.78(11) | 97.60(5) | 99.36(4) |

| S(1)–Ni(1)–S(2) | 93.25(5) | 90.41(2) | 89.621(18) |

| C(9)–S(2)–Ni(1) | 108.44(17) | 104.66(6) | 107.39(6) |

Parameters for one of the two unique, but chemically similar, Ni complexes observed in the asymmetric unit of 4.

Computations

All computations were performed using the ORCA 2.9.0 program developed by Dr. Frank Neese.56 The crystallographically determined coordinates for 2 provided the initial structures for the computational model (II) and its one-electron oxidized derivative (IIox). Both models were then subjected to unconstrained geometry optimizations within the framework of DFT using Becke's three-parameter hybrid functional and the Lee–Yang–Parr correlation functional (B3LYP).57,58 Ahlrichs’ valence triple-ζ basis set, TZV(P) basis set,59,60 was chosen for the Ni, N, and S atoms, respectively, while Ahlrichs’ polarized split valence and auxiliary basis sets,59 SV(P) and SV/C, were selected for all of the remaining atoms. The spin-restricted formalism was chosen for II, while the spin-unrestricted formalism was used for IIox, which was modeled as S = ½. Single-point DFT calculations on the geometry-optimized models were performed using the same functional and basis sets as those used in the geometry optimizations. The Pymol program61 was utilized to generate isosurface plots of MOs and spin densities with isodensity values of 0.05 and 0.005 a.u., respectively.

The ORCA 2.9.0 program was also employed to compute EPR parameters for the geometry-optimized model IIox by using the DFT-based coupled-perturbed self-consistent field approach in conjunction with the B3LYP functional. This calculation was performed using the CP(PPP) basis set62,63 for Ni, Kutzelnigg's NMR/EPR (IGLO-III) basis set64 for all N and S atoms, and the TZV(P) basis set for the remaining atoms.

Oxidation of 3

To a solution of 3 containing 10.9 mg of 3 (0.0194 mmol) stirring in 4 mL of DMF was added ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) dropwise (1.748 mL of a 10.0 mM DMF solution, 0.0175 mmol) at RT. Upon the addition of CAN, the red-brown color associated with the Ni(II)-N2S2 complex was replaced by a dark-green color. The mixture was stirred for another 15 min at RT and filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon filter to yield a green transparent DMF solution. A red solid of a color consistent with a minor amount of 1 was evident in the filter. The oxidation was monitored by UV-vis and EPR spectroscopy.

Oxidation of 2

Chemical oxidation of 2 was performed in the same manner as with 3, except for using 11.2 mg (0.0227 mmol) of 2 and 2.045 mL of CAN (10.0 mM DMF solution, 0.0205 mmol). The red solution of 2 darkened to green upon the addition of CAN. Within minutes, the green color paled with the appearance of a red precipitate.

Oxidation of 4

Chemical oxidation of 4 was performed in the same manner as with 3, except for using 9.6 mg (0.020 mmol) of 4 and 1.752 mL of CAN (10.0 mM DMF solution, 0.0175 mmol). The orange-red solution of 4 paled to light orange upon addition of CAN with the appearance of a red precipitate.

Oxidation of 5

Chemical oxidation of 5 was performed in the same manner as with 3, except for using 8.9 mg (0.016 mmol) of 5 and 1.459 mL of CAN (10.0 mM DMF solution, 0.0146 mmol). The orange-red solution of 5 paled to light orange upon addition of CAN with the appearance of a red precipitate.

Reactivity

UV-vis Monitoring of 3 and 3ox with NaN3 and N-methylimidazole

To a 5 mM DMF stock (2.5 mL) of 3 was added 10 equiv of N-methylimidazole (N-MeIm) or NaN3, and the UV-vis spectrum was recorded. Solutions were oxidized in the same manner as above in the presence of 10 equiv of N-MeIm or NaN3 to observe any changes in the electronic absorbance profile to indicate anion binding to the metal center.

Reactivity with KO2

To 5 mM DMF solutions of 3 or 3ox (generated by adding 1 equiv of CAN to 3) was added 1 equiv of KO2 in DMF containing 18-crown-6 ether (4.1 equiv).65 Workup of the reaction is as stated in Chart S2 in the SI.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

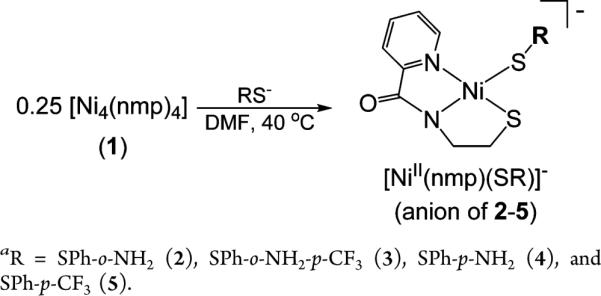

Synthesis

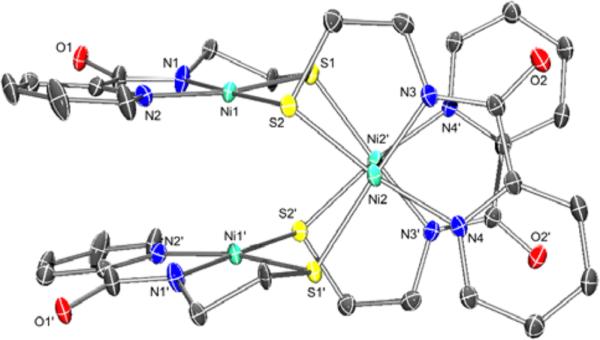

In previous work,32,33 an S,S-bridged Ni-nmp unit was used as a metallosynthon to generate 4C planar Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes of the general formula [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− as active site models of NiSODred. The ligand nmp2− is a tridentate chelate that contains pyridine-N, carboxamide-N, and alkyl thiolate-S donors that replicate the asymmetric ligand environment derived from His1 and Cys2 in the enzyme. In these reports, various ways of changing R on the monodentate thiolate (analogous to Cys6) were explored, and most syntheses were based on splitting a putative [Ni2(nmp)2] S,S-bridged dimeric complex with various exogenous thiolate ligands. Elemental analysis and FTIR data of the solid were consistent with the proposed formula, but the poor solubility of this complex precluded more detailed spectroscopic and structural analyses. Based on a structure reported herein (vide infra), we describe this complex to be a tetrameric S,S-bridged species [Ni4(nmp)4] (1) (Figure 2). While this result alters our prior synthetic schemes, it does not change the ratio of exogenous thiolate-to-Ni(nmp) used, i.e., 1:1 when considering single Ni(nmp) units in the S,S-bridged complex. As such, complexes 2–5 were synthesized by reacting a 40 °C DMF slurry of 1 with 4 equiv of the Et4N+ salts of various thiolates to yield the monomeric Ni(II) complexes in modest-to-good yields (50%–75%) (see Scheme 1). All complexes were isolated as analytically pure (except 5) dark-red to orange-red solids of moderate stability to air. However, decomposition to the free thiol and 1 occurred when dissolved in protic solvents such as MeOH or H2O, even under anaerobic conditions.

Figure 2.

ORTEP of [Ni4(nmp)4] (1) with the atom labeling scheme at 50% thermal probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Ni(II) Complexesa

Spectroscopic Properties

Complexes 2–5 are soluble in polar solvents such as DMF and MeCN to form deeply colored red-brown solutions arising from charge-transfer (CT) bands in the 430–460 nm range (ε = 3800–7200 M−1 cm−1 in MeCN at 298 K). NiSODred displays an absorption profile with a λmax at 450 nm (ε = 480 M−1 cm−1) and a shoulder at 543 nm (ε = 150 M−1 cm−1) arising from d–d transitions,10 a spectroscopic benchmark of 4C planar Ni(II) centers in an N2S2 coordination environment.40 These ligand-field bands are masked in 2–5 by the intense CT features that involve electronic transitions between py-N and Ni(II).33 Further solution measurements such as 1H NMR experiments revealed that all complexes are diamagnetic, as expected for a 4C planar Ni(II) ion (see Figures S5, S7, S9, and S11 in the Supporting Information (SI)). These results do not exclude higher coordination numbers, as low-spin tbp or square-pyramidal Ni(II) would also be S = 0, but NMR results of known o-aminothiophenolate N,S-coordinated planar Ni(II) complexes exhibit shifts in the NH2 resonance (δNH2) by +1.4 ppm upon coordination.66 In addition, the symmetric and asymmetric N–H stretches (νNH) of the NH2 group red-shift by ~200 cm−1 upon coordination.66 The NH2 proton resonance is close (+0.15–0.28 ppm) to the value obtained for the free thiolate and there are no significant changes in νNH in 2–4. These minor changes in δNH2 and νNH confirm that no Ni(II)–NH2Ph bond exists in 2–4 under the conditions used.

Structural Characterization

The tetrameric complex 1 and monomeric complexes 2 and 4 have been characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), the details of which can be found in the Experimental Section, Table 1, and Table S1 in the SI. Complex 1 crystallizes with four separate Ni(nmp) fragments bridged by the alkyl-S of another Ni(nmp) complex (see Figure 2). A summation of the significant bond lengths and angles is provided in Table 1, and a comparison with other monomeric [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− complexes is provided in Table 2. The tetramer is formed through specific Ni–S–Ni linkages (e.g., Ni1–S2–Ni2–S1′), such that each nmp-S bridges a different 4C planar Ni(II) ion. Compared to other reported [Ni(nmp)-(SR)]− structures with NiN2S2 coordination,32,33 the average Ni–Ncarboxamide distance (1.862 Å) is significantly shorter than that for Ni–Npy (1.943 Å), because of strong σ-donation by the carboxamide ligand. This property, along with the monodentate nature of SR, generally results in a longer Ni–Sexo versus Ni–Snmp bond distance. Indeed, this bond is considerably longer in 1 (2.208 Å) than the Ni–S bond originating from the coordinated nmp2− ligand (2.155 Å). In this case, Sexo represents a metallothiolate from another Ni(nmp) unit instead of an exogenously added thiolate ligand in prior reports. The average Ni···Ni separation is 3.4 Å, which precludes any direct Ni–Ni interaction.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances for [Ni(nmp)(SR)]– NiSOD Model Complexesa

| Bond Distances (Å) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Ni–Ncarboxamide | Ni–Npy | Ni–Snmp | Ni–Sexo |

| SPh-p-Cl | 1.8638(14) | 1.9470(14) | 2.1492(5) | 2.2139(4) |

| StBu | 1.882(2) | 1.9635(19) | 2.1629(7) | 2.1938(7) |

| S-o-babtb | 1.877(3) | 1.947(3) | 2.1518(12) | 2.1939(14) |

| S-mebc | 1.863(7) | 1.944(7) | 2.156(3) | 2.172(3) |

| SPh-o-NH2 | 1.8750(16) | 1.9418(16) | 2.1386(6) | 2.2173(6) |

| SPh-p-NH2 | 1.8698(14) | 1.9450(14) | 2.1474(5) | 2.2160(5) |

| average | 1.872 ± 0.008 | 1.948 ± 0.008 | 2.151 ± 0.008 | 2.201 ± 0.018 |

Bond distances reported for Ni(1), N(1), N(2), S(1), and S(2) of the unit cell.

S-o-babt = anion of o-benzoylaminobenzenethiol.

S-meb = anion of N-(2-mercaptoethyl)benzamide.

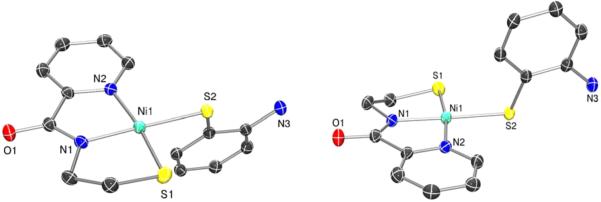

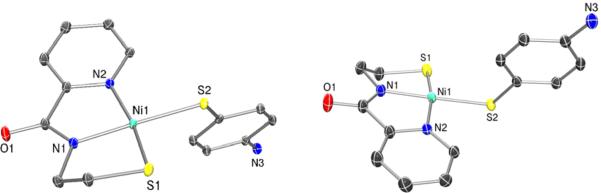

Analogous to previously published [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− structures,32,33 2 and 4 (Figures 3 and 4, respectively and Figure S1 in the SI) demonstrated distorted 4C planar Ni(II) centers with two N- and two S-ligands in a cis disposition, resulting in a Ni(II)-N2S2 coordination sphere as in NiSODred. Crystallographic details and selected bond distances and angles are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Complex 4 crystallizes with two unique, but chemically equivalent, Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes. Bond distances are comparable to 1 and other [Ni(nmp)-(SR)]− structures (Ni–Ncarboxamide: 1.8750 Å (2), 1.8698 Å (4); Ni–Npy: 1.9418 Å (2), 1.9450 Å (4); Ni–Snmp: 2.1386 Å (2), 2.1474 Å (4); Ni–Sexo: 2.2173 Å (2), 2.2160 Å (4); see Table 2 for a comparison with all structurally characterized Ni-nmp complexes) and reflect a trend in the electronic nature or Lewis basicity of the differing donor atoms. To emphasize the strong-field nature of the carboxamide donor, other 4C planar NiSODred models (N = 4)29,31,35,43 with multidentate chelates exhibit short Ni–Ncarboxamide bonds (average: 1.861 Å) and long Ni–Strans-carboxamide bonds (average: 2.175 Å) in their crystal structures. Thus, the lengthening of the Ni–Sexo bonds in 2 and 4 is not solely due to the monodentate Sexo coordination. NiSODred exhibits similar distances (average from the two reported Streptomyces structures): Ni-NH2(His1): 1.97 ± 0.14 Å; Ni–Npeptide(Cys2): 1.93 ± 0.02 Å; Ni–S(Cys2): 2.20 ± 0.06 Å; Ni–S(Cys6- trans to peptide-N): 2.19 ± 0.01 Å.11,12 The trends expected for the different Ni–N and Ni–S bonds are presumably muted in the enzyme structures due to poor resolution and the redox heterogeneity in the crystals (equal mix of Ni(II) and Ni(III) ions). In 2 and 4, the closest Ni–NH2 distance is 4.4 Å, establishing the absence of any five-coordinate species in the solid state. The Ni···NHis distance is also long in NiSODred, 4.26 Å (PDB: 1T6U) and 3.81 Å (PDB: 1Q0D), indicative of the nonbonding nature of this potential N-donor in the enzyme. Because of the ortho-positioning of the aniline-NH2 in 2, the N and coordinated Sexo are separated by 3.024 Å (sum of the van der Waals radii for N and S is 3.55 Å), which would suggest an intramolecular hydrogen bond with the ligated S. However, the N–H–S angle is estimated to be 110° (if H is placed in an ideal position), suggesting relatively poor orbital overlap between the donor–acceptor pair. Strong hydrogen bonds are usually linear in nature, i.e., ∠N–H···S ≈ 180°.67 To emphasize the importance of this angle, hydrogen bonding to coordinated S-ligands in other NiSOD model compounds usually results in a decrease by 0.02–0.03 Å in the Ni–S distance due to relief of the Ni(dπ)–S(pπ) antibonding interaction, as the S lone pair is engaged in the hydrogen bond.33,41 No such contraction of the Ni–S bonds was observed, when compared to the non-hydrogen-bonded complex 4. Collectively analyzing the six structurally characterized complexes in this family (Table 2) revealed that distances to the nmp2− ligating atoms are largely invariable. The largest variations appear in Sexo (Ni–S(avg.): 2.201 ± 0.018 Å), which range from 2.172 to 2.217 Å and generally correlate with the electronic nature of this particular S-donor.

Figure 3.

Different views of the ORTEP of the anion of (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] (2) with the atom labeling scheme at 50% thermal probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Figure 4.

Different views of the ORTEP of the anion of (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-p-NH2)] (4) with the atom labeling scheme at 50% thermal probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Electrochemistry

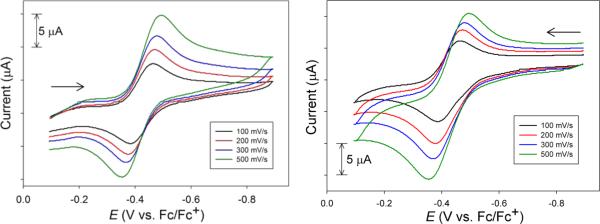

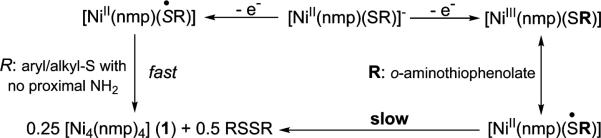

To assess the role of the o-NH2 group in the electrochemical activity of the Ni-nmp complexes, we performed cyclic voltammetry (CV) on 2–5. Previously reported [NiII(nmp)(SR)]− complexes display irreversible waves in their CVs with cathodic and anodic peaks assigned to redox activity associated with the coordinated RS− ligand, i.e., [NiII(nmp)(SR)]− → 0.25[NiII4(nmp)4] (1) + 0.5RSSR.32,33 Similar CVs and redox assignments were also observed with the peptide-based [NiII(GC-OMe)(SR)]− (GC-OMe is the dianion of H2N-Gly-l-Cys-OMe) complexes.34 In both cases, R represented simple aryl/alkyl thiolates or more complex thiolates with appended hydrogen-bonding moieties. In this study, we anticipated that providing a potential N-donor ligand from the o-aminothiophenolate would provide a viable mechanism to capture an oxidized species related to NiSODox.

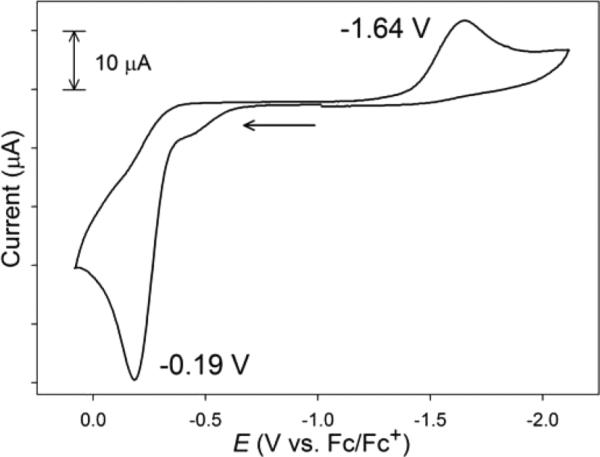

Representative CVs are displayed in Figures 5 and 6, as well as Figures S2 and S3 in the SI. All CVs were recorded in DMF at RT and E values are reported versus an externally referenced ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+) couple using a glassy carbon working electrode and 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte. Electrochemical measurements on 4 and 5, complexes without an o-NH2 group, revealed irreversible waves (ΔEp ≈ 1.5 V) in the CV that are due to Sexo redox. The CV of 5 (containing the p-CF3 group), for example, displayed two distinct electrochemical events at potentials of −1.64 V (Ered) and −0.19 V (Eox) (Figure 5) that we assign as the RS• (or 0.5 RSSR) → RS− and RS− → RS• (or 0.5 RSSR) electrochemical reactions, respectively. These values are on par with reported potentials for simple organic disulfides such as PhSSPh (Eox = −0.49, Ered = −2.12 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMF)68 and even more structurally complex thiolates that display qualitatively similar CVs.69 The CV of a related 4C planar Ni(II)-NS3 complex, [Ni(pdmt)(SPh)]− (pdmt = pyridine-2,6-dimethanethiolate), which also owes its electrochemical activity to the monodentate thiolate PhS−, resembles the CV of 5 with values (Eox = −0.47, Ered = −1.73 V in DMF) shifted approximately +0.20 V from that of free PhSSPh (above) due to coordination to Ni(II).70 The comparative positive shift of ~0.40 V in the Ered/ox associated with 5 from PhSSPh is consistent with the electron-withdrawing p-CF3 substituted aryl thiolate ligand. Complex 4 with the p-NH2 substitution on SR behaved similarly (Eox = −0.51 V in DMF) with additional low current intensity waves that we have yet to identify (see Figure S2 in the SI). Again, comparison with p-NH2-PhSSPh-p-NH2 (Eox = −0.88, Ered = −2.33 V vs Fc/Fc+ in DMF)68 revealed a slight shift upon coordination of the thiolate to Ni(II). Regardless, the CVs of 4 and 5 only reflect ligand-based electrochemistry with no indication of a Ni(III/II) process. Additional verification of the reactions displayed in Scheme 2 (left side) comes from bulk oxidation experiments with CAN or Fc+, which yielded 1 and the corresponding disulfide in near stoichiometric yield. Collectively, the [NiII(nmp)(SR)]− complexes with simple alkyl/aryl R-groups do not go through any observable Ni(III) state, as all oxidation chemistry is associated with Sexo (even the electron-deficient Sexo in 5) and is suggestive of the high S-character in the HOMO of these complexes.

Figure 5.

CV of an 8 mM solution of 5 in DMF at RT (glassy carbon working electrode, 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte, 100 mV/s scan speed). The arrow shows the direction of the scan.

Figure 6.

CV of a 3.5 mM solution of 3ox in DMF at RT from different scan directions (see arrow, glassy carbon working electrode, 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte).

Scheme 2.

General Redox Activity of [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− Complexes

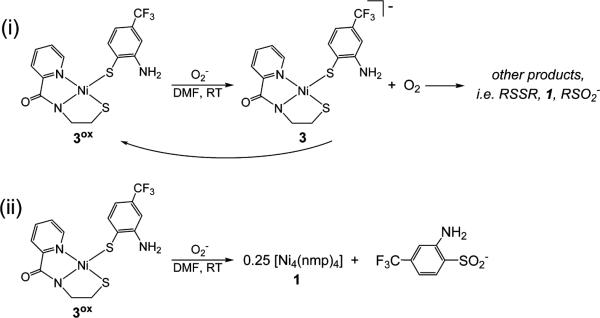

The CVs of 2 and 3 displayed similar irreversible waves with the exception of a quasi-reversible wave observed at E1/2 = −0.69 V and −0.43 V for 2 and 3, respectively (DMF, RT), that was slightly superimposed on Eox. As expected, the oxidation of 2 is easier than 3 due to the p-CF3 substitution on Sexo. Since the free o-aminothiophenolate is irreversibly oxidized at more positive potentials, this E1/2 may be assigned as a metal-centered Ni(III/II) electron-transfer process. For simplicity, we will limit our discussion to complex 3, but similar CVs were observed for 2 (see Figure S3 in the SI). The possibility of isolating and characterizing an oxidized NiSOD model, as suggested by the electrochemistry, led us to generate this species (termed 3ox) by chemical oxidation with CAN and to study its redox properties. Interestingly, the CV of in situ-generated 3ox displayed a redox-couple at E1/2 = −0.43 V (ΔEp ≈ 0.060 V; and ipa/ipac ≈ 1) that was remarkably similar to the CV of 3 (Figure 6 and Figure S3 in the SI). Additional metrics such as the linear (r2 = 0.991, of 3ox) ip vs v1/2 plot support the fact that this couple is a reversible, diffusion-controlled process. Scanning from either side of the isolated E1/2 does not result in any changes (Figure 6). It is important to reiterate that [NiII(nmp)(SR)]− complexes do not exhibit any reversibility in their CVs (see Figure 5). The appearance of such a wave in the CV of 3 is thus a new feature in these otherwise isostructural NiSOD model complexes. A unique feature of 3 is the presence of the o-NH2 group that must be the stabilizing feature to allow observation of such an oxidized species on the CV time scale. We propose that this redox event is due to one of the following couples: (i) [NiII(nmp)(SR)]−/[NiIII(nmp)(SR)] or (ii) [NiII(nmp)(SR)]−/[NiII(nmp)(•SR)]. In case (ii), the o-NH2 group supports a coordinated S-radical to prevent the formation of RSSR and 1 that would result in the typical irreversible CVs (Scheme 2). Of course, a resonance description of [NiIII(nmp)(SR)] ↔ [NiII(nmp)(•SR)] is the more-realistic possibility (vide infra) (Scheme 2, right side).

Properties of 3ox

Exposure of DMF solutions of 2 or 3 to air or O2(g) resulted in an immediate color change of the solution from red to green accompanied by the eventual formation of a red precipitate. These solutions afforded a broad, low-energy feature at ~900 nm in the RT electronic absorption spectrum. This transformation occurs on the minute (2, full formation of 1 within minutes) or hour (3, ~70% 1 after 24 h) time scale with the red precipitate confirmed to be 1, suggesting the same ultimate fate as seen with other [Ni(nmp)(SR)]− complexes (Scheme 2). However, the difference here is that transient oxidized complexes are spectroscopically observable. Furthermore, chemical reduction of in situ-generated 3ox with [Co(Cp)2] resulted in regeneration of the reduced species 3 as verified by UV-vis, 1H NMR, and ESI-MS experiments. Thus, bulk chemical oxidation and reduction mirrored the electrochemical observations and was also a reversible process. Due to the longer lifetime of 3ox, we limit our discussion below to this species, although similar spectroscopic observations were noted for 2.

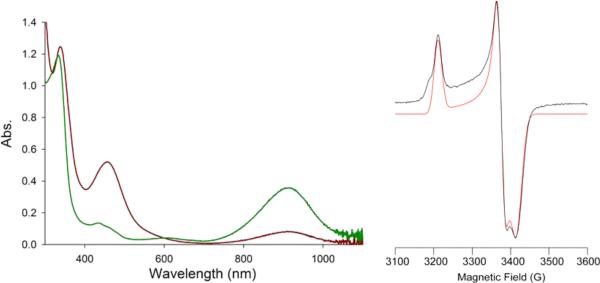

To better identify the oxidized complex, we performed in situ spectroscopic characterization of the reaction mixture after chemically oxidizing 3 with oxidants such as CAN or Fc+ salts. For example, addition of a stoichiometric amount of CAN to a DMF solution of 3 at RT immediately generated a green solution with a broad and intense absorption band at 910 nm, concomitant with the disappearance of the CT band associated with 3 at 450 nm (Figure 7). Low-energy bands in this region have been observed in 4C planar Ni(III) complexes with N2S2 dicarboxamido-dithiolato coordination and were attributed to S-to-Ni(III) CT transitions,44 a common spectroscopic feature for Ni(III)-N/S coordination complexes. Interestingly, Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes containing o-aminothiophenolate ligands with radical character also exhibit a low-energy band in a similar range in their UV-vis spectra. However, it must be noted that these bands are observed for the Ni-coordinated o-iminosemiquinonato form that would require the loss of two protons and one electron from the original o-aminothiophenol (see Chart S1 in the SI).66 A close structural comparison of the C–C (avg: 1.397 ± 0.011 Å), C–S (1.773 Å), and C–N (1.392 Å) distances of Sexo in 2 and, by analogy, 3 did not reveal any contraction in the C–N (1.348 Å), C–S (1.724 Å) distances nor the quinoid structure (average = 1.405 ± 0.0226 Å) typical of a o-iminosemiquinonate and are more consistent with a coordinated thiophenolate anion71 (see Chart S1 in the SI). It is thus unlikely that an N,S-coordinated o-iminosemiquinonate is present in 2ox or 3ox. However, spectroscopically characterized metal-thiyl complexes with thiophenolate ligands of Ni(II) (λ = 670–800 nm in CH2Cl2),72 Co(III) (λ = 780 nm in CH2Cl2),73 Ru(III) (λ = 850 nm in acetone),74 and V(IV) (λ = 910 nm in MeCN)75 exhibit broad and distinct low-energy bands similar to 3ox. These are significantly red-shifted from the broad transition observed for the free phenylthiyl radical (λ = 460–500 nm) generated by pulse radiolysis in pH 11 aqueous solution.71 Most of these metal-thiyl complexes have been observed at low temperature, due to rapid formation of the disulfide, which is not surprising considering the second-order decay rate for disulfide formation from free PhS• (k = 9.6 × 109 M−1 s−1).71 These facts make the spectroscopic observation of 3ox even more noteworthy, in that this species is stable for hours at 298 K. After 24 h in DMF, the green color of 3ox faded and the red precipitate of 1 was isolated in ~70% yield.

Figure 7.

(Left) UV-vis spectrum of 3 (red trace) and in situ-generated 3ox (green trace) by addition of CAN to 3 in DMF at 298 K. (Right) X-band EPR spectrum (black trace) and simulation (red trace) of in situ generated 3ox in DMF at 10 K. Simulation parameters: g = [2.132, 2.028, 2.004], W = 35, 30, 45 MHz.

An X-band EPR spectrum was collected for in situ-generated 3ox at 10 K in a DMF glass and is shown in Figure 7, along with a simulated fit. According to the simulation, the three g-values observed are g = 2.132 (~g∥), 2.028, and 2.004 (gavg = 2.055; g⊥ ≈ 2.016) with line widths of 35, 30, and 45 MHz, respectively. The typical EPR pattern for Ni(III), as seen in complexes that unambiguously contain Ni(III), such as NiIIIF430M,76 the oxidized cofactor from methyl coenzyme M reductase (MCR), and a wide variety of Ni(III) tetraazamacrocyclic77,78 and amino acid79,80 complexes, can be described by g⊥ ≈ 2.2–2.3 and g∥ = 2.00, which arise from a low-spin d7 configuration with the single unpaired electron residing in the Ni dz2 orbital.80 EPR parameters for relevant, formally Ni(III) complexes are summarized in Table S2 in the SI. This classical Ni(III) EPR pattern is the reverse of that seen here for 3ox, so the present complex cannot be an exclusive Ni(III) species with a dz21 ground state.

EPR spectra previously reported for Ni(III)–N2S2 complexes that more closely resemble 3 do not exhibit quite the classical pattern described above, as the symmetry of these complexes is often lower, leading to more rhombic EPR spectra, but most do have g⊥ ≈ 2.2–2.3 and g∥ ≈ 2.00.10,36,43,44,81–83 Moreover, their spectra are more anisotropic with g-spreads, gmax – gmin ≈ 0.3, as opposed to 0.128 for 3ox, and with an overall greater deviation from the free electron (radical) g value (ge = 2.00) than for 3ox (2.055), namely with gavg ≈ 2.2.10,36,44,81,83 The lower g-spread in 3ox, smaller deviation from ge, and ambiguous electronic ground state (see computational section below) would be more consistent with a coordinated S-radical with a smaller degree of electron delocalization onto the Ni d-orbitals, as observed in Ni-S4 (bis-dithiolene) complexes,84,85 than in classical Ni(III) complexes and even in other oxidized Ni(II) complexes with N2S2 donor sets. Thus, taken together, the UV-vis and EPR spectra support a Ni(III)-(SR) ↔ Ni(II)-(•SR) description for 3ox, rather than a genuine Ni(III)-SR species.

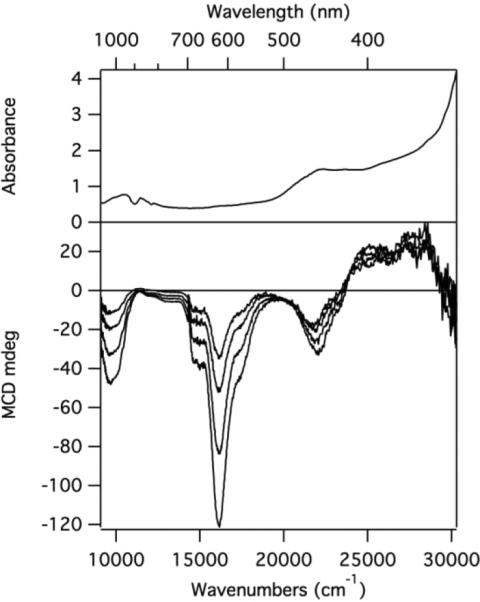

Low Temperature Absorption and MCD

The low temperature (4.5 K) absorption spectrum of 2ox, generated by sparging 2 with O2(g) for 5 min, exhibited a broad band centered at ~22 000 cm−1 (455 nm) and a lower energy feature at ~10 000 cm−1 (1000 nm) (Figure 8, top). The MCD spectrum of this sample (Figure 8, bottom) exhibited negatively signed features corresponding to the bands observed in the low temperature absorption spectrum, as well as a prominent feature at ~16 000 cm−1 (625 nm). All MCD features increase in intensity with decreasing temperature, characteristic of C-term behavior and indicative of a paramagnetic species. Note that the three features observed in the MCD spectrum of 2ox coincide with the three absorption bands observed at RT of in situ-generated 3ox (Figure 7), providing further evidence that 2ox and 3ox have nearly identical electronic structures. Given the relatively high intensities of the MCD features exhibited by 2ox, it can be concluded that, in this species, and by analogy in 3ox, significant unpaired spin density resides on the Ni atom. In support of this conclusion, the large ratio of MCD-to-absorption intensity of the feature at ~16 000 cm−1 (625 nm) indicates that the corresponding transition contains significant Ni 3d → 3d character.

Figure 8.

Low temperature absorption (4.5 K, top) and MCD (4.5, 8, 15, and 25 K, bottom) spectra of 2ox generated in situ by sparging 2 in a 1:4 (v/v) solvent mixture of MeCN and butyronitrile with O2(g) for 5 min.

Computations

To obtain further insight into the geometric and electronic structures of 2ox, DFT geometry optimization and property calculations were performed for a model of this species (termed IIox). An analogous geometry optimization for a model of the crystallographically characterized precursor 2 (model II) yielded Ni–ligand bond distances that agree reasonably well with the experimental values, thus validating our approach used to generate a model of the structurally ill-defined complex 2ox (Table 3). During the geometry optimization of IIox, the Ni atom retained a 4C planar geometry with Ni–ligand bond distances somewhat shorter than those in its one-electron reduced counterpart II (Table 3). A DFT calculation of the EPR parameters for IIox yielded g-values of 2.16, 2.06, and 2.04, which agree well with the g-values determined experimentally for 3ox of 2.132, 2.028, 2.004 (Figure 7). Therefore, an analysis of the computed electronic structure description for IIox is warranted.

Table 3.

Ni–Ligand Bond Distances in DFT-Optimized Models of II and IIox, Compared with X-ray Crystallographically Determined Values for 2

| DFT |

X-ray Structure of 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| II | IIox | (Et4N)[Ni(nmp)(SPh-o-NH2)] | |

| Ni–Sexo | 2.278 | 2.211 | 2.218 |

| Ni–Snmp | 2.198 | 2.169 | 2.138 |

| Ni–Ncarboxamide | 1.895 | 1.880 | 1.875 |

| Ni–Npy | 1.981 | 1.990 | 1.942 |

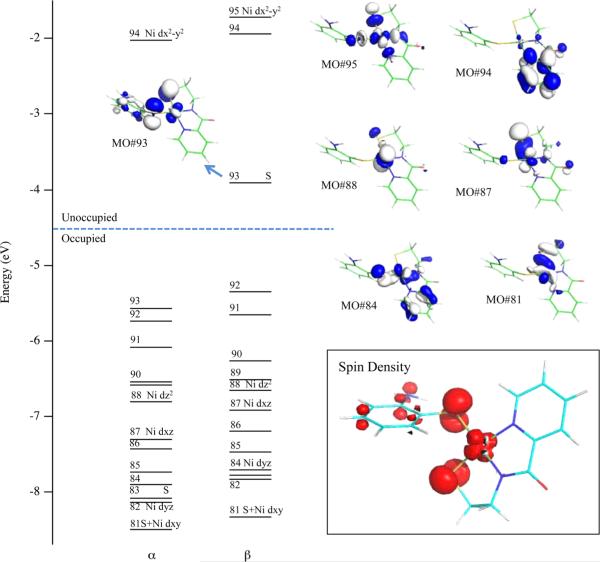

A comparison of the spin-up (α) and spin-down (β) manifolds of MOs obtained from a spin-unrestricted DFT calculation for IIox (Figure 9) revealed that the βLUMO (βMO#93) corresponds to the formally singly occupied MO, as its α-counterpart (αMO#83, not shown) is occupied. To higher energy, the βLUMO+2 (βMO#95) can be identified as the Ni 3dx2-y2-based MO, while the βLUMO+1 (βMO#94) is mainly localized on the aryl-carboxamide moiety of the supporting nmp2− ligand. As expected for a 4C planar complex, the occupied Ni 3dz2-, 3dxy-, 3dxz-, and 3dyz-based orbitals (βMO#88, #87, #84, and #81, respectively) are significantly stabilized relative to the unoccupied Ni 3dx2-y2-based βMO#95.

Figure 9.

Relevant portion of the MO diagram and isosurface plots of select βMOs obtained from a spin-unrestricted DFT calculation for IIox. Inset: Spin density plot for IIox (red = positive spin density; white = negative spin density).

The βLUMO has predominant S 3p (53% total: 26% from Sexo and 27% from Snmp) and Ni 3d (21%; mainly 3dxz and some 3dyz) orbital character, suggesting that the removal of an electron from II results in partial oxidation of both the thiolates and the Ni(II) ion. Consistent with this prediction, a plot of the spin density for IIox shows that the unpaired electron is delocalized over the two S and the Ni atoms (Figure 9, inset). Consequently, our computational results obtained for IIox indicate that 2ox is best described as a hybrid of [Ni(III)-(−SR)] ↔ [Ni(II)-(SR)] resonance structures. This description is in line with the intense MCD features and sizable g-spread displayed by 3ox relative to a free thiyl.

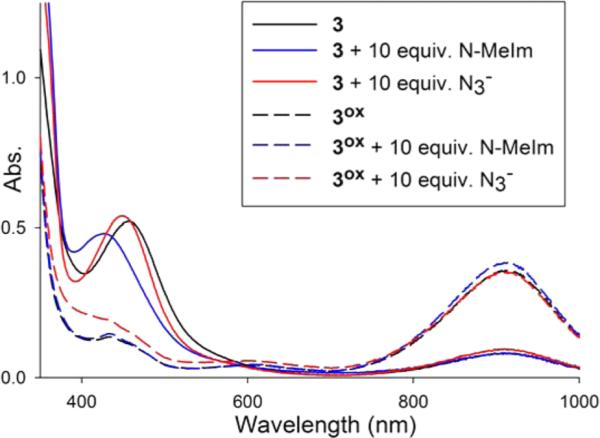

Reactivity of 3ox with Azide and Superoxide

The azide anion (N3−) is often employed as a redox-inert analogue of superoxide to obtain information on M–O2• − interactions. NiSOD shows no direct Ni–N3− interaction based on EPR, UV-vis, and resonance Raman (rR) studies.10,12 To evaluate the anion affnity of the Ni center in 3 and 3ox, we added excess (10 equiv) NaN3 to this NiSOD model and monitored its UV-vis spectrum. As observed for NiSOD, the UV-vis spectrum of 3 or 3ox did not change upon the addition of N3− (Figure 10), even after 1 h. Despite the presence of the potentially coordinating amine-N from Sexo, we tested whether the presence of 10 equiv of N-MeIm impacted any Ni–N3− bonding. Indeed, the addition of N-MeIm resulted in a ~30 nm blue-shift in λmax of 3 that may imply a Ni···N-MeIm interaction; however, no other direct evidence for a Ni-NMeIm bond was obtained. Analogous to the results in the absence of N-MeIm, no change was observed in the UV-vis spectrum when 10 equiv of N3− are added (Figure 10); thus, much like NiSOD, the Ni center in 3 and 3ox does not bind N3−.

Figure 10.

UV-vis spectra of 3 (black) and 3ox (black dash); 3 + 10 equiv N-MeIm (blue) and 3ox + 10 equiv N-MeIm (blue dash); 3 + 10 equiv N3− (red) and 3ox + 10 equiv N3− (red dash). All experiments were performed in DMF at 298 K.

To evaluate the potential of 3 and 3ox as SOD catalysts, experiments were performed with 18-crown-6 ether solubilized KO2 in DMF at 298 K. Addition of a stoichiometric amount of KO2 to a DMF solution of 3 resulted in no reaction, as monitored by UV-vis. However, the same reaction with in situ generated 3ox produced an immediate solution color change from green to red-brown. To obtain more information regarding the products formed in this reaction, fractional precipitation and isolation of the components present in the reaction mixture were performed (see Chart S2 in the SI). After vacuum distilling DMF from the reaction mixture, MeCN was added that afforded a red-orange precipitate and a brown MeCN-soluble portion. The MeCN-insoluble component was identified as the tetrameric species 1, based on FTIR data. Two separate reactions of 3ox and O2• − revealed that the bulk of the Ni-nmp ends up as 1 (avg: 65% yield). Further attempts at separating components in the MeCN-soluble portion by selective precipitation with THF and Et2O revealed the presence of 3 and the free unbound sulfinate (RSO2−) and sulfonate (RSO3−) of Sexo based on ESI-MS (see Figure S4 in the SI). Unfortunately, quantitative isolation of species other than 1 was not possible due to similar solubility profiles and the presence of CAN-related species. In addition, no O2(g) generation was observed utilizing electrochemical detection methods.86 One can envision two primary reaction paths of 3ox with superoxide: (i) O2• − behaves as an outer-sphere reductant to furnish the corresponding Ni(II) complex 3 and O2 (Scheme 3i), or (ii) O2• − oxygenates the Sexo atom of 3ox to generate the resulting sulfinate (RSO2−) and tetramer 1 (Scheme 3ii). Scheme 3i would be more in line with a Ni(III) assignment for 3ox, whereas Scheme 3ii is more consistent with a Ni(II)-thiyl. However, one could envision the formation of similar products in both pathways if the product Ni(II) species 3 in Scheme 3i reacted with O2 in a manner other than as an outer-sphere Ni(II) oxidant (i.e., “other products” in Scheme 3i). Either scenario explains the lack of any detectable O2(g) via electrochemistry, although the path in Scheme 3ii is more consistent with the significant amount of isolated 1 in the reaction mixture. Regardless of the path at work, these results advocate for a Ni(II)-thiyl assignment for 3ox.

Scheme 3.

Possible Scenarios for the Reaction of 3ox with Superoxide

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have prepared and characterized four Ni(II)-N/S complexes of the general formula [Ni(N2S)(SR′)]−, where SR′ represents a site-differentiated location of the N2S2 coordination sphere as models of NiSOD. The SR′ ligand was functionalized with electron withdrawing substituents and/or a tethered N-donor in efforts to promote the formation of an oxidized Ni(III) complex that would be structurally and electronically analogous to the Ni–N3S2 coordination sphere of NiSODox. We hypothesized that the incorporation of a weak Naxial ligand in SR′ from o-aminothiophenolate could mimic the long (2.3–2.6 Å) Ni-NHis bond in NiSOD and would be required to obtain such an oxidized species. Indeed, site-directed variants and DFT calculations revealed that the axial Ni-NHis bond in NiSODox is crucial for maintaining the rate (k ≈ 109 M−1 s−1)87,88 and appropriate electrochemical potential (0.090 V vs Ag/AgCl, pH 7.4, phosphate buffer) for turnover.10,89 In addition, the few low molecular weight NiSOD models that access Ni(III) or that exhibit some SOD activity contain an Naxial ligand.27,34,35 Chemical oxidation of NiSOD models 4 and 5 that lack this potential N-donor resulted in the quantitative formation of 1 and the disulfide (R′SSR′) of the monodentate thiolate. This result was not too surprising, given the expected high percentage of S-character in the HOMO of such Ni(II)-N2S2 complexes, although we had initially anticipated the electron-deficient thiolate in 5 would prevent such chemistry. Chemical oxidation of models 2 and 3 that contain a potential N-donor ligand resulted in the transient formation of an oxidized species (2ox and 3ox) that is best described as a resonance hybrid of a Ni(III)-thiolate and Ni(II)-thiyl species: [Ni(III)-(SR)] ↔ [Ni(II)-(•SR)]. This assignment was confirmed through a variety of experimental (X-ray, UV-vis, MCD, EPR, reactivity) and theoretical (DFT) techniques. These results may at first appear incongruent with the actual mechanism of NiSOD. Most experimental work supports an outer-sphere electron transfer mechanism for O2•− disproportionation with the Ni(III/II) center possibly remaining 5C throughout catalysis.8,39,40 In the first turnover, conversion of 4C NiSODred to 5C NiSODox likely results in a 4C planar intermediate (NiSODox-Hisoff) before formation of NiSODox due to the kinetics of electron transfer versus Ni–N(His) bond formation. Although this transient species has never been observed experimentally, DFT computations on NiSODox-Hisoff indicate a predominant Ni-based HOMO and support a Ni(III) oxidation state (vide supra) even before axial His1 binding. This assignment is in contrast to the Ni(III)-thiolate ↔ Ni(II)-thiyl resonance description for the NiSOD models 2ox and 3ox. However, •S(Cys) radicals have been observed in other enzymes,90 some of which function through such a radical species.91–97 Based on the EPR spectrum, Ni exists in the 3+ state in NiSODox with no indications of a coordinated •S(Cys), but the results presented here suggest that the transition from NiSODred to NiSODox-Hisoff may go through a Ni-stabilized/coordinated •S(Cys).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T.C.H. acknowledges financial support from a National Science Foundation CAREER Award (No. CHE-0953102) and the Offce of the Vice President for Research (OVPR) and the Offce of the Provost at the University of Georgia (UGA). T.C.B. acknowledges financial support by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. GM 64631). S. D. acknowledges the NIH (Grant No. T32-GM008505) for support and the NSF (Grant No. CHE-0840494) for computational resources.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

Additional structural data for 1, 2, and 4 including CIF files, CVs of 2, 3, and 4, a table of selected EPR-active Ni complexes, the flowchart and ESI-MS workup of the reaction of 3ox + KO2, and the 1H NMR and high-resolution ESI-MS of 2–5 are provided as Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Valentine JS, Wertz DL, Lyons TJ, Liou L-L, Goto JJ, Gralla EB. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998;2:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller A-F. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCord JM. In: Critical Reviews of Oxidative Stress and Aging: Advances in Basic Science, Diagnostics, and Intervention. Rodriguez H, Cutler R, editors. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte., Ltd.; Singapore: 2003. pp. 883–895. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Leo ME, Borrello S, Passantino M, Palazzotti B, Mordente A, Daniele A, Filippini V, Galeotti T, Masullo C. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;250:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kocatürk PA, Akbostanci MC, Tan F, Kavas GÖ. Pathophysiology. 2000;7:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(00)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB., III J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2003;17:24–38. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortunato G, Pastinese A, Intrieri M, Lofrano MM, Gaeta G, Censi MB, Boccalatte A, Salvatore F, Sacchetti L. Clin. Biochem. 1997;30:569–571. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(97)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheng Y, Abreu IA, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ, Miller A-F, Teixeira M, Valentine JS. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3854–3918. doi: 10.1021/cr4005296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller A-F. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiedler AT, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Brunold TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5449–5462. doi: 10.1021/ja042521i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wuerges J, Lee J-W, Yim Y-I, Yim H-S, Kang S-O, Carugo KD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:8569–8574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308514101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Bruns CK, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8038–8047. doi: 10.1021/bi0496081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grapperhaus CA, Darensbourg MY. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:451–459. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neupane KP, Shearer J. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10552–10566. doi: 10.1021/ic061156o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearer J, Long LM. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:2358–2360. doi: 10.1021/ic0514344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tietze D, Breitzke H, Imhof D, Kothe E, Weston J, Buntkowsky G. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009;15:517–523. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tietze D, Tischler M, Voigt S, Imhof D, Ohlenschläger O, Görlach M, Buntkowsky G. Chem.—Eur. J. 2010;16:7572–7578. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tietze D, Voigt S, Mollenhauer D, Tischler M, Imhof D, Gutmann T, González L, Ohlenschläger O, Breitzke H, Görlach M, Buntkowsky G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:2946–2950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shearer J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:2569–2572. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shearer J, Peck KL, Schmitt JC, Neupane KP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16009–16022. doi: 10.1021/ja5079514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause ME, Glass AM, Jackson TA, Laurence JS. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:362–364. doi: 10.1021/ic901828m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause ME, Glass AM, Jackson TA, Laurence JS. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:2479–2487. doi: 10.1021/ic102295s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass AM, Krause ME, Laurence JS, Jackson TA. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:10055–10063. doi: 10.1021/ic301717q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause ME, Glass AM, Jackson TA, Laurence JS. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:77–83. doi: 10.1021/ic301175f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma H, Chattopadhyay S, Petersen JL, Jensen MP. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:7966–7968. doi: 10.1021/ic801099r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma H, Wang G, Yee GT, Petersen JL, Jensen MP. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362:4563–4569. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee W-Z, Chiang C-W, Lin T-H, Kuo T-S. Chem.—Eur. J. 2012;18:50–53. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakane D, Funahashi Y, Ozawa T, Masuda H. Chem. Lett. 2010;39:344–346. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shearer J, Zhao N. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:9637–9639. doi: 10.1021/ic061604s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shearer J, Dehestani A, Abanda F. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:2649–2660. doi: 10.1021/ic7019878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathrubootham V, Thomas J, Staples R, McCraken J, Shearer J, Hegg EL. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5393–5406. doi: 10.1021/ic9023053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gale EM, Patra AK, Harrop TC. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:5620–5622. doi: 10.1021/ic9009042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gale EM, Narendrapurapu BS, Simmonett AC, Schaefer HF, III, Harrop TC. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:7080–7096. doi: 10.1021/ic1009187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gale EM, Cowart DM, Scott RA, Harrop TC. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10460–10471. doi: 10.1021/ic2016462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gale EM, Simmonett AC, Telser J, Schaefer HF, III, Harrop TC. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:9216–9218. doi: 10.1021/ic201822f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gennari M, Orio M, Pécaut J, Neese F, Collomb M-N, Duboc C. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6399–6401. doi: 10.1021/ic100945n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gennari M, Retegan M, DeBeer S, Pécaut J, Neese F, Collomb M-N, Duboc C. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10047–10055. doi: 10.1021/ic200899w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullins CS, Grapperhaus CA, Frye BC, Wood LH, Hay AJ, Buchanan RM, Mashuta MS. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:9974–9976. doi: 10.1021/ic901246w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shearer J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2332–2341. doi: 10.1021/ar500060s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broering EP, Truong PT, Gale EM, Harrop TC. Biochemistry. 2013;52:4–18. doi: 10.1021/bi3014533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullins CS, Grapperhaus CA, Kozlowski PM. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006;11:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neupane KP, Gearty K, Francis A, Shearer J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14605–14618. doi: 10.1021/ja0731625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakane D, Wasada-Tsutsui Y, Funahashi Y, Hatanaka T, Ozawa T, Masuda H. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:6512–6523. doi: 10.1021/ic402574d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiedler AT, Brunold TC. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:8511–8523. doi: 10.1021/ic061237k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenfield SG, Armstrong WH, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:3014–3018. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palermo RE, Power PP, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1982;21:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belford RL, Belford GG. J. Chem. Phys. 1973;59:853–854. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulmer GR, Miller AJM, Sherden NH, Gottlieb HE, Nudelman A, Stoltz BM, Bercaw JE, Goldberg KI. Organometallics. 2010;29:2176–2179. [Google Scholar]

- 49.SMART v5.626: Software for the CCD Detector System. Bruker AXS; Madison, WI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker N, Stuart D. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1983;A39:158–166. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldrick GM. SADABS, Area Detector Absorption Correction. University of Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheldrick GM. SHELX-97, Program for Refinement of Crystal Structures. University of Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL 6.1, Crystallographic Computing System; Siemens Analytical X-Ray Instruments. Madison, WI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burnett MN, Johnson CK. ORTEP-III, Report No. ORNL-6895. Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Oak Ridge, TN: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neese F. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1998;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schäfer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;97:2571–2577. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neese F. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002;337:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 61.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4. Schrödinger, LLC; Cambridge, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wachters AJH. J. Chem. Phys. 1970;52:1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 63.The Ahlrichs (2d2fg,3p2df) polarization functions were obtained from the TurboMole basis set library under ftp.chemie.unikarlsruhe.de/pub/basen Sc-Zn: 2p functions from ref 60, plus one f-function from the TurboMole library.

- 64.Kutzelnigg W, Fleischer U, Schindler M. The IGLO Method: Ab Initio Calculation and Interpretation of NMR Chemical Shifts and Magnetic Susceptibilities. Vol. 23. Springer–Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gampp H, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;22:357–358. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herebian D, Bothe E, Bill E, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10012–10023. doi: 10.1021/ja011155p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jeffrey GA. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding. 1st Edition Oxford University Press, Inc.; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antonello S, Daasbjerg K, Jensen H, Taddei F, Maran F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14905–14916. doi: 10.1021/ja036380g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang TM, Tomat E. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:7846–7849. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50824b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krüger H-J, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:1148–1155. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tripathi GNR, Sun Q, Armstrong DA, Chipman DM, Schuler RH. J. Phys. Chem. 1992;96:5344–5350. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stenson PA, Board A, Marin-Becerra A, Blake AJ, Davies ES, Wilson C, McMaster J, Schröder M. Chem.—Eur. J. 2008;14:2564–2576. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kimura S, Bill E, Bothe E, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6025–6039. doi: 10.1021/ja004305p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grapperhaus CA, Poturovic S. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:3292–3298. doi: 10.1021/ic035085u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang Y-H, Su C-L, Wu R-R, Liao J-H, Liu Y-H, Hsu H-F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5708–5711. doi: 10.1021/ja2004208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jaun B. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1990;73:2209–2217. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wieghardt K, Walz W, Nuber B, Weiss J, Ozarowski A, Stratemeier H, Reinen D. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gore ES, Busch DH. Inorg. Chem. 1973;12:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J-F, Kumar K, Margerum DW. Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:3481–3484. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lappin AG, Murray CK, Margerum DW. Inorg. Chem. 1978;17:1630–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krüger H-J, Peng G, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:734–742. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Green KN, Brothers SM, Jenkins RM, Carson CE, Grapperhaus CA, Darensbourg MY. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:7536–7544. doi: 10.1021/ic700878y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanss J, Krüger H-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:360–363. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<360::AID-ANIE360>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lim BS, Fomitchev DV, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:4257–4262. doi: 10.1021/ic010138y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Szilagyi RK, Lim BS, Glaser T, Holm RH, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9158–9169. doi: 10.1021/ja029806k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carvalho NMF, Antunes OAC, Horn A., Jr. Dalton Trans. 2007;2007:1023–1027. doi: 10.1039/b616377g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herbst RW, Guce A, Bryngelson PA, Higgins KA, Ryan KC, Cabelli DE, Garman SC, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3354–3369. doi: 10.1021/bi802029t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ryan KC, Guce AI, Johnson OE, Brunold TC, Cabelli DE, Garman SC, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1016–1027. doi: 10.1021/bi501258u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bryngelson PA, Arobo SE, Pinkham JL, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:460–461. doi: 10.1021/ja0387507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giles NM, Giles GI, Jacob C. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;300:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Licht S, Gerfen GJ, Stubbe J. Science. 1996;271:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fontecave M, Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Mulliez E. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2149–2166. doi: 10.1021/cr020427j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cutsail GE, III, Telser J, Hoffman BM. [March 19, 2015];Biochim. Biophys. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.01.025. Acta, DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.1001.1025 (published online: Feb. 14, 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grove TL, Benner JS, Radle MI, Ahlum JH, Landgraf BJ, Krebs C, Booker SJ. Science. 2011;332:604–607. doi: 10.1126/science.1200877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Silakov A, Grove TL, Radle MI, Bauerle MR, Green MT, Rosenzweig AC, Boal AK, Booker SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8221–8228. doi: 10.1021/ja410560p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang J, Woldring RP, Román-Mélendez GD, McClain AM, Alzua BR, Marsh ENG. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:1929–1938. doi: 10.1021/cb5004674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Broderick JB, Duffus BR, Duschene KS, Shepard EM. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4229–4317. doi: 10.1021/cr4004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.