Abstract

The gut microbiota has the capacity to produce a diverse range of compounds that play a major role in regulating the activity of distal organs and the liver is strategically positioned downstream of the gut. Gut microbiota linked compounds such as short chain fatty acids, bile acids, choline metabolites, indole derivatives, vitamins, polyamines, lipids, neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hormones have many biological functions. This review focuses on the gut microbiota and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis. Dysbiosis in liver cirrhosis causes serious complications, such as bacteremia and hepatic encephalopathy, accompanied by small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and increased intestinal permeability. Gut dysbiosis in cirrhosis and intervention with probiotics and synbiotics in a clinical setting is reviewed and evaluated. Recent studies have revealed the relationship between gut microbiota and host metabolism in chronic metabolic liver disease, especially, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and with the gut microbiota metabolic interactions in dysbiosis related metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity. Recently, our understanding of the relationship between the gut and liver and how this regulates systemic metabolic changes in liver cirrhosis has increased. The serum lipid levels of phospholipids, free fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially, eicosapentaenoic acid, arachidonic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid have significant correlations with specific fecal flora in liver cirrhosis. Many clinical and experimental reports support the relationship between fatty acid metabolism and gut-microbiota. Various blood metabolome such as cytokines, amino acids, and vitamins are correlated with gut microbiota in probiotics-treated liver cirrhosis patients. The future evaluation of the gut-microbiota-liver metabolic network and the intervention of these relationships using probiotics, synbiotics, and prebiotics, with sufficient nutrition could aid the development of treatments and prevention for liver cirrhosis patients.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, Microbiota, Metabolism, Fatty acids, Probiotics

Core tip: The gut microbiota has the capacity to produce a diverse range of compounds that have a major role in regulating the activity of distal organs and the liver is strategically positioned downstream of the gut indicating the importance of the gut-liver axis. This review focuses on gut microbiota and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis. The serum lipid levels of phospholipids, free fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid, arachidonic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid have significant correlations with specific fecal flora in liver cirrhosis. Various blood metabolome such as cytokines, amino acids, and vitamins are correlated with gut microbiota in probiotics-treated liver cirrhosis patients.

INTRODUCTION

An increasing amount of recent evidence has demonstrated that several diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, allergy, cancer, obesity, autism and liver disease, are related to alterations in intestinal microbiota (known as dysbiosis)[1-3]. Gut-derived complications in liver cirrhosis such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut), resulting in bacterial or endotoxin translocation-related systemic disorders such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hyperdynamic state, portal hypertension, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, and multiple organ failure, have been reported in clinical settings[2,4-8]. Different etiologies of liver cirrhosis, including viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease (ALD), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), have different gut microbiota and mechanisms of developing liver fibrosis. Furthermore, each disease has a different hepatic metabolism, suggesting further development in this research area[2,7-9]. However, there have been few reports of correlations between gut microbiota and host metabolism in cirrhotic patients. This review will discuss (1) the relationship between gut microbiota and host metabolism in general; (2) the results of intervention for liver cirrhosis by probiotics; and (3) gut-microbiota and host metabolism in cirrhosis and the use of systems biology as a tool for analysis.

GUT MICROBIOTA AND HOST METABOLISM

The anatomy of the liver provides its close interaction with the gut[9,10]. Gut-derived bacteria and their components and metabolites, as well as nutrients and other signals are delivered to the liver via the portal circulation. Then, the liver plays a crucial role in defense against gut-derived materials, which is defined as the gut-liver axis[9,10]. Gut microbiota function as a bioreactor for autonomous metabolic and immunological functions that can mediate responses within the host environment in response to external stimuli[11]. The complexity of the gut microbiota suggests that it behaves as an organ. Therefore, the concept of the gut-liver axis must be complemented with the gut-microbiota-liver network because of the high intricacy of the microbiota components and metabolic activities[11].

The host and its gut microbiota coproduce a large array of small molecules during the metabolism of food and xenobiotics (compounds of non-host origin that enter the gut with the diet or are produced by microbiota), many of which play critical roles in communication between host organs and the host’s microbial symbionts. The metabolite, gut microbiota, and potential biologic functions are shown in Table 1[12-40].

Table 1.

Metabolite, gut microbiota, and potential biologic functions

| Metabolites | Related bacteria | Potential biological functions | Ref. |

| Short-chain fatty acids | Clostridial clusters IV and XIVa of Firmicutes, including species of Eubacterium, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and Coprococcus | Decreased colonic pH, inhibit the growth of pathogens; stimulate water and sodium absorption; participate in cholesterol synthesis; provide energy to the colonic epithelial cells; GI hormones secretion via enteroendocrine cells, implicated in human obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer. Immunological homeostasis in the gut | [14-18] |

| Bile acids | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria, Enterobacter, Bacteroides, Clostridium | Absorb dietary fats and lipid-soluble vitamins, facilitate lipid absorption, maintain intestinal barrier function, signal systemic endocrine functions to regulate triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose and energy homeostasis | [19-21] |

| Choline metabolites | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium | Modulate lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis. Involved in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, dietary induced obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease | [22,23] |

| Phenolic, benzoyl, and phenyl derivatives | Clostridium difficile, F. prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium, Subdoligranulum, Lactobacillus | Detoxification of xenobiotics; indicate gut microbial composition and activity; utilize polyphenols. Urinary hippuric acid may be a biomarker of hypertension and obesity in humans. Urinary 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, 4-cresol, and phenylacetate are elevated in colorectal cancer. Urinary 4-cresyl sulfate is elevated in children with severe autism | [24,25] |

| Indole derivatives | Clostridium sporogenes, E. coli | Protect against stress-induced lesions in the GI tract; modulate expression of proinflammatory genes, increase expression of anti-inflammatory genes, strengthen epithelial cell barrier properties. Implicated in GI pathologies, brain-gut axis, and a few neurological conditions | [26-28] |

| Vitamins | Bifidobacterium | Provide complementary endogenous sources of vitamins, strengthen immune function, exert epigenetic effects to regulate cell proliferation | [29,30] |

| Polyamines | Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium saccharolyticum | Exert genotoxic effects on the host, anti-inflammatory and antitumoral effects. Potential tumor markers | [31,32] |

| Lipids | Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Clostridium | Impact intestinal permeability, activate intestine-brain-liver neural axis to regulate glucose homeostasis; LPS induces chronic systemic inflammation; conjugated fatty acids improve hyperinsulinemia, enhance the immune system and alter lipoprotein profiles. Cholesterol is the basis for sterol and bile acid production | [33,34] |

| Neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds:serotonin, tryptophan, kynurenine. dopamine, noradrenaline, GABA | Lactobacillus ,Bifidobacterium, Escherichia, Bacillus, Saccharomyces, Candida, Streptococcus, Enterococcus | Neurofunction related as mood, emotion, cognition, reward (CNS), motility/secretion and behavior | [35-39] |

| HPA hormones: cortisol | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Indirect regulation of HPA. Regulation of stress response, host metabolism, anti-inflammation, wound healing, endocrine abnormalities prominent in stress related psychiatric disorders | [40] |

GI: Gastrointestinal; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid; CNS: Central nervous system; HPA: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal. Adapted from Ref. [12, 13] and revised by the authors.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), predominantly butyrate, acetate and propionate, are anaerobically produced by gut microbiota in the intestine. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, are a significant source of energy for gut enterocytes, and influence the gastrointestinal barrier function through the stimulation of tight junction and mucous production[41-43]. The authors showed that tight junction permeability was decreased by SCFAs in a Caco-2 intestinal monolayer and human umbilical vein endothelial cell monolayer, via lipoxygenase activation in in vitro studies[44,45]. This suggests that SCFAs may have biological effects in other organs as well as the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest a role for SCFAs in reducing inflammation[41]. Our previous reports showed that increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production and nuclear factor kappa B activity induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were downregulated by SCFAs using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and co-culture of macrophages and adipocytes[46-48]. LPS-induced acute liver injury was attenuated by orally administered tributyrin, a prodrug of butyrate and a dairy food component, via increased portal vein concentration up to one to two orders of magnitude in rats[49]. In humans, two reports by Bloemen et al[50,51] measuring portal and hepatic venous SCFA concentrations indicated a porto-systemic shunting effect in liver cirrhosis patients.

SCFAs are also proposed to increase satiety following the consumption of a diet rich in fiber as they act as agonists for free fatty acid receptors 2 and 3 (FFAR2/3 known as G-protein coupled receptor; GPR43/41). Both of these GPRs trigger the production and release of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), peptide YY (PYY) and other gut hormones that stimulate satiety in the host[52]. Gut intestinal (GI) hormones such as ghrelin and leptin secretion are mediated on enteroendocrine cells by the action of SCFAs[18,53]. SCFAs that traffic to distal sites and can be carried by monocarboxylate transporters, which are abundantly expressed at the blood-brain barrier then enter the central nervous system[54-57]. However, it remains to be definitively established whether alterations in intestinal microbiota-derived SCFAs are actually reflected at physiologically relevant concentrations in the central nervous system[13].

Bile is composed of individual bile acid moieties, mucous, phospholipids and biliverdin, and their main physiological roles in the small intestine are the emulsification of fats, the release of fat-soluble vitamins and regulation of cholesterol metabolism[58]. Specific bile acids differentially act as ligands to activate or repress host receptors, including farnesid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, vitamin D receptor and the GPR, TGR5. These receptors are expressed locally on various intestinal epithelial cells and systematically, within a diverse range of organs including both the liver and adipose tissue[21]. Therefore, bile acids function as systemic signaling molecules and significantly alter host gene-expression profiles[21,59].

Choline synthesized by intestinal biota is important for lipid metabolism and is metabolized to trimethylamine, then further metabolized in the liver to trimethylamine-N-oxide that contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease[22]. Reducing the bioavailability of choline can contribute to NAFLD and altered glucose metabolism[60]. Phenolic, benzoyl, and phenyl derivatives produced by the detoxification of xenobiotics have various bioactivities, are indicators of microbial composition and activity, and are useful biomarkers for several diseases including liver disease[25].

A significant amount of the neurotransmitter dopamine is produced in the human gut[61]. Norepinephrine and dopamine production in the gut is mediated by the expression of β-glucuronidases from commensal gut bacteria through the cleavage of their inactive conjugated forms[62]. Nitric oxide produced by gut microbes plays a pivotal role in gastric emptying[63]. The inhibitory transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid is generated by Lactobacillus brevis and Bifidobacterium dentium, both of which have been isolated from humans[64,65]. The precursors to neuroactive compounds, such as tryptophan for serotonin function and the kynurenine pathway, are controlled by gut-microbiota as a bidirectional communication component of the brain-gut axis[39].

The role of gut microbiota in the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been extensively analyzed using germ-free mice[40]. The concept of Microbial Endocrinology was reported and the importance of controlling gut microbiota in relation with various host functions was discussed by Lyte and colleagues[13,66].

GUT MICROBIOTA AND ITS MANIPULATION IN LIVER CIRRHOSIS

The gut microbiota plays an important role in the pathophysiology of cirrhosis. Changes in gastrointestinal functions, including malabsorption and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, is common with concomitant portal hypertension in cirrhosis patients[67]. Recent reviews reported the pathophysiologic changes of gut microbiota in cirrhotic patients, gut-bacterial interactions, “leaky gut”, translocation of bacteria and gut-derived LPS in infectious complications, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatic encephalopathy[2,5,68,69]. Hyperdynamic circulation, portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, renal disturbance including hepatorenal syndrome, and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in cirrhosis are correlated with endotoxemia[6].

ALD is a spectrum of alcoholic diseases including steatosis, steatohepatitis, acute alcoholic steatohepatitis, alcoholic fibrosis, and cirrhosis (Laennec’s Cirrhosis) caused by excessive alcohol use over a prolonged period of time[9]. Multiple pathogenic factors are involved in the development of ALD. Alcohol and its metabolites induce reactive oxygen species and hepatocyte injury through mitochondrial damage and endoplasmic reticulum stress[70,71]. The activation of Kupffer cells has been identified as a central element in the pathogenesis of ALD. Kupffer cells and recruited macrophages in the liver are activated by LPS through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, and LPS levels increase in the portal and systemic circulation after excessive alcohol intake[72]. Fibrosis is a dynamic and progressive process governed by stellate cell activation by LPS, TLR4 and inflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β signaling[73].

NAFLD is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide as a result of the increasing prevalence of obesity, characterized by a spectrum of liver diseases ranging from simple fatty liver (NAFL) to steatohepatitis (NASH) with a possible progression to fibrosis[11]. The concept of the gut-liver axis may be complemented with the gut-microbiota-liver network because of the high intricacy of the microbiota components and metabolic activities; these activities form the active diet-driven power plant of the host[11,74]. However, there have been few descriptive studies on gut-microbiota composition under NASH and NAFLD conditions; therefore, the type and role of gut microbes in human liver damage are poorly understood[11]. The use of meta-omic platforms to assist the understanding of NAFLD gut-microbiota alteration as a tool and its application in patients has been proposed[11]. A detailed explanation of the meta-omic platform is described later.

As for the therapeutic approach to control dysbiosis, selective digestive decontamination (SDD), probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics have been performed. SDD is a method to treat bacterial translocation-related complications caused by poorly absorbed antibiotics such as quinolone. SDD was effective in some studies but a major concern of long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and increased infections in chronic disease situations[75].

In this review, probiotics and synbiotics in liver cirrhosis are discussed. Probiotics were defined by the World Health Organization in 2001 as “live microorganisms, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Prebiotics belong to a group of nondigestive food constituents that selectively alter the growth and/or activity of bacteria in the colon. The combined use of probiotics and prebiotics is called synbiotics. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, the main species of probiotics, are considered as nonpathogenic to humans. The pathophysiologic basis for using probiotics in liver disease is as follows: (1) prevention of infection; (2) improvement of the hyperdynamic circulatory state of cirrhosis; (3) prevention of hepatic encephalopathy; (4) improvement of liver function; and (5) therapeutic potential of NAFLD[76].

Infection, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and endotoxemia, can be induced in compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients with or without surgery. Rayes et al[77,78] also reported the beneficial effects of probiotics against infectious complications in cirrhosis patients that underwent liver transplantation or liver resection. We reported that synbiotics (Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and galacto-oligosaccharides) treatment attenuated the decrease in intestinal integrity as assessed by serum diamine-oxidase activity and reduced infectious complications after hepatic surgery[79]. Meta-analysis indicated an apparent reduction of infectious complications (odds ratio 0.24) in abdominal surgery[80]. However, a small size randomized controlled clinical trial showed that VSL#3® treatment to decompensated cirrhotic patients reduced plasma aldosterone, but did not reduce the incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[81]. As for hyperdynamic circulation, a prospective study reported that VSL#3® improved hemodynamic states, hepatic venous pressure gradients, cardiac index, heart rate, systemic vascular resistance, and mean arterial pressure, without any adverse reactions in cirrhosis patients with ascites[82]. Several reports showed that probiotics treatment to cirrhosis patients prevented hepatic encephalopathy with decreased blood ammonia or bilirubin levels[83,84]. The mechanism of hepatic encephalopathy prevention is the improvement of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and gut dysbiosis[84]. VSL#3® treatment improved hepatic function, serum aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase levels, both in NAFLD and cirrhosis patients with ALD and hepatitis C virus infection[85]. As for NAFLD, the immune-regulatory effects of probiotics may be beneficial in NAFLD treatment, and they should be considered a complementary therapeutic approach in NAFLD patients as indicated in a review by Ferolla et al[86]. The mechanisms of action are increased fatty acid formation, change in colonic pH, growth factor induction, change in intestinal flora, bacterial adherence inhibition by colonization resistance, immune modulation, increased phagocyte activity, increased IgA secretion and modulation of lymphocyte functions[87].

Table 2[69,77-79,81,83,85,88-94] shows the main randomized controlled studies in cirrhosis patients. These reports suggest that probiotics treatment improved gut dysbiosis and bacterial translocation, leading to the improvement of cirrhosis prognosis. Trials with probiotics in general have been limited by a lack of stability of the products as a drug and differences among bacterial species and subspecies[93,95]. Therefore, the results have been heterogeneous with regard to the duration, type of organism or combination of organisms and outcomes, and mixed results been achieved. The properties of different probiotic species vary and can be strain-specific. This is also complicated by a lack of uniformity in batch-to-batch formulations and studies not being performed under an investigational new drug regulatory procedure. The variety of available probiotics also makes the accumulation of evidence difficult. Furthermore, a risk of bacterial sepsis and fungal sepsis should be considered in infants and immune-deficient patients[96].

Table 2.

Effects of the probiotics intervention on gut microbiota composition and its clinical and/or biochemical consequences

| Type of study | Category of patients/duration of treatment | Probiotics | Clinical outcome | Ref. |

| RCT | 36 cirrhotics/6 mo | Lactobacillus.acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium lactis and S. thermophiles | Blood ammonia levels | [88] |

| RCT | 65 cirrhotics/6 mo | Lactobacilli | Incidence of HE, hospital admission, plasma-ammonia level, serum bilirubin level | [83] |

| R | 50 cirrhotics/14 d | Bifidobacterium, L. acidophilus and Enterococcus vs Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium | Bifidobacterium count, fecal pH, fecal and blood ammonia in both groups, endotoxin level only with B. subtilis and E. faecium | [89] |

| RCT | 17 cirrhotics with HVPG > 10 mmHg/2 mo | VSL # 3® | Plasma aldosterone | [81] |

| RCT | 41 chronic liver disease/14 d | Bifidobacterium bifidus, L. acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and S. thermophilus | E. coli count, intestinal flora imbalance, improvement in debilitation, food intake, abdominal distension, and ascitic fluid | [90] |

| RCT | 66 cirrhotics underwent liver transplantation/2 wk after the operation | Pediacoccus pentosaceus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus paracasei and Lactobacillus plantarum | Infectious complication | [78] |

| RCT | 39 cirrhotics/42 d | E. coli Nissle | Endotoxemia, Child-Pugh score, Restoration of normal colonic colonization | [91] |

| RCT | 63 cirrhotics patients with large oesophageal varices without history of variceal bleeding/2 mo | Propranolol plus VSL # 3® | HVPG, plasma TNF-α levels. | [92] |

| RCT | 25 nonalcoholic minimal HE cirrhotics (defined by a standard psychometric battery)/60 d | Yogurt contained L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus | Minimal HE | [93] |

| RCT | 61 cirrhotics underwent hepatic surgery/2 wk before and after surgery | Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota, Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult, and galactooligosaccharides | Intestinal integrity, infectious complication | [79] |

| RCT | 63 cirrhotics underwent liver transplantation/12 d after the operation | L. plantarum 299 and oat fiber | Infectious complication | [77] |

| RCT | 50 cirrhotics underwent living donor liver transplantation/2 d and 2 wk before and after the operation, respectively | L. casei strain Shirota, B. breve strain Yakult, and galactooligosaccharides | Infectious complication | [94] |

| RCT | 30 cirrhotics with minimal HE/4 wk | Lactobacillus GG | Endotoxemia, gut dysbiosis, gut microbiome-metabolome linkages | [69] |

| RCT | 138 cirrhotics/3 mo | VSL # 3® | HE, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | [84] |

HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; HVPG: Hepatic venous pressure gradient; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; R: Randomized.

GUT MICROBIOTA AND HOST METABOLISM IN LIVER CIRRHOSIS

The effect of gut microbiota on host metabolism has been reported in the context of host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions in dysbiosis related metabolic diseases (diabetes, obesity and chronic liver disease) as various obesity-associated mechanisms including insulin resistance, fibrosis, and abnormalities in lipid metabolism[8,86,97]. However, few studies on the association between gut microbiota and metabolism in cirrhosis have been reported.

We previously reported the measurement of fecal microbiota, organic acids, and plasma lipids in hepatic cancer patients in three different groups characterized by histopathology as normal liver, chronic hepatitis/liver fibrosis, and liver cirrhosis[46]. These data were obtained by fecal culture without using probiotics and by comparison among different liver diseases. The serum lipid levels of phospholipids, free fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), EPA/arachidonic acid (AA) ratio, AA and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) had significant correlations with specific fecal flora, such as Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, and Candida (Figure 1). These correlations differed among the three groups suggesting that chronic liver disease itself modifies fatty acid metabolism induced by intestinal flora. These data indicate that the relationship between gut microbiota and host metabolism differs by metabolic activity of the liver, indicating that individual “the gut-microbiota-liver network” exists in each clinical disease entities and the importance to evaluate in future studies[11].

Figure 1.

Correlation networks among fecal microflora and organic acid and serum organic and fatty acid concentrations in hepatic cancer patients. Square boxes indicate fecal components and ellipsoids indicate serum components. Solid lines indicate positive correlations and dotted lines indicate negative correlations. A: Normal liver group; B: Chronic hepatitis or liver fibrosis group; C: Liver cirrhosis group. aP < 0.05 and bP < 0.01 by Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. Bact: Bacteroidaceae; Bifi: Bifidobacterium; Lact: Lactobacillus; Enteroba: Enterobacteriaceae; Enteroco: Enterococcus; Cand: Candida; C1: Formic acid; C2: Acetic acid; C3: Propionic acid; C4: Butyric acid; AA: Arachidonic acid; EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid; FFA: Free fatty acid; PL: Phospholipid. Data adapted from Usami et al[46].

With regards to polyunsaturated fatty acids, Wall et al[98] performed a mouse study investigating the effects of Bifidobacterium breve NCIMB 702258 administration with coadministration of α-linolenic acid on fatty acid composition of the liver, adipose tissues, large intestine and brain, and showed increased c9, t11 conjugated linoleic acid and EPA levels in the liver, while Bifidobacterium administration alone did not change the EPA levels in normal mice. Wall et al[99] also demonstrated increased EPA levels in adipose tissues from severe combined immunodeficient mice after Bifidobacterium breve NCIMB 702258 administration. Conjugated linoleic acid is a microbial metabolite associated with the alleviation of NAFLD[100]. Kankaanpää et al[101] reported the effects of 8 wk of Bifidobacterium Bb-12- or Lactobacillus CG-supplemented infant formula administration on the plasma fatty acid composition in infants. They found that Bifidobacterium decreased serum phospholipid EPA to 61% and AA levels to 77% compared with baseline values. In addition, Lactobacillus decreased EPA to 22% and AA to 62%. These reports described the effects of probiotics on host fatty acid compositions, but the results differed among the probiotics used and the host conditions. It was recently demonstrated that exposure of the human intestinal mucosa to Lactobacillus plantarum WCFSI induced the upregulation of genes in the intestinal mucosa involved in lipid/fatty acid transport, uptake and metabolism, such as CD36 and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein[102]. Several genes participating in mitochondrial and peroxisomal fatty acid metabolism were also upregulated[102].

With regards to liver damage and metabolism in hepatitis C virus patients, hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection perturbed glucose homeostasis through several direct and indirect mechanisms, leading to both hepatic and extrahepatic insulin resistance and accelerated disease progression including the development of hepatocellular carcinoma and type 2 diabetes[103]. Furthermore, changes in polyunsaturated fatty acids and lipid metabolism induced by hepatitis C core protein is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of lipid metabolism disorders[102,104]. The administration of AA or EPA modulated the hepatitis C viral mechanism in hepatocytes[105]. Every step of the hepatitis C virus life cycle is intimately connected to lipid metabolism[106].

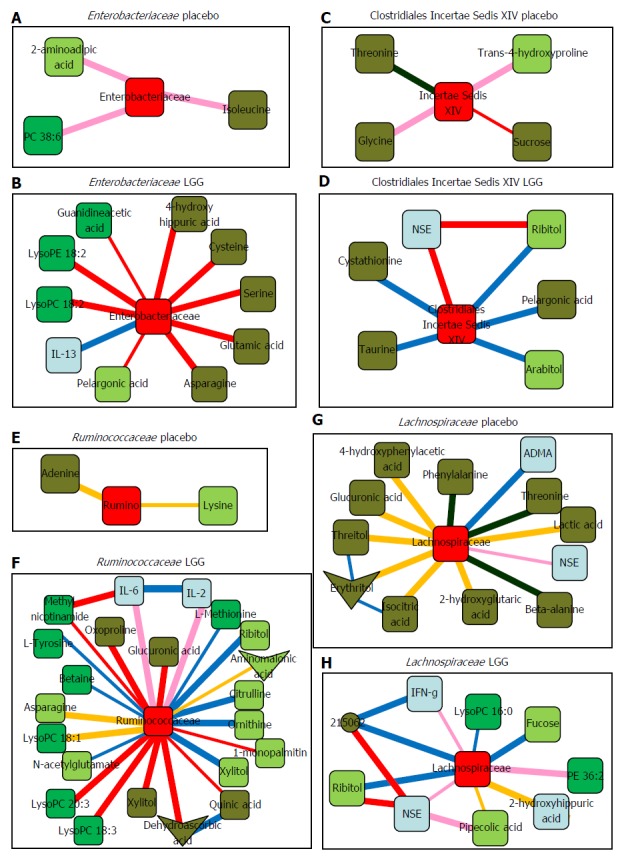

Bajaj et al[69] reported gut microbiota and serum/urine metabolome in a phase I randomized clinical trial using probiotic Lactobacillus GG (LGG) in patients with cirrhosis. They showed the safety and tolerance of 4 wk LGG administration in cirrhosis patients, which improved endotoxemia and gut dysbiosis. Furthermore, significant gut microbe-metabolome linkage was obtained by LGG as the results of system biology analysis. Figure 2 shows the correlation network among changed gut microbiota by LGG and metabolomic analysis. For example, a reduction in Enterobacteriaceae was associated with a linked change with anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-13 and ammoniagenic amino acids that was not seen in the placebo group. Changes in the levels of several vitamins in the blood were also observed following the co-administration of multivitamins with sufficient nutrition in both the LGG and placebo groups in their study.

Figure 2.

Sub-networks showing correlation network differences from baseline to week 8 in placebo and in Lactobacillus GG groups separately centered on selected bacterial taxa. Color of nodes: Blue, inflammatory cytokine; light green, serum metabolites; dark green, urine metabolites. Color of edges: pink, negative remained negative but there is a net loss of negative correlation; dark blue, negative changed to positive; yellow, positive remained positive but there is a net loss of positive correlation; red, positive to negative; dark green, complete shift of negative to positive; military green, complete shift of positive to negative. A, B: Sub-networks of correlation changes centered around Enterobacteriaceae; C, D: Sub-networks of correlation changes centered around Clostridiales Incertae Sedis XIV; E, F: Sub-networks of correlation changes centered around Ruminococcaceae; G, H: Sub-networks of correlation changes centered around Lachnospiraceae. NSE: Neuron-specific enolase; IL: Interleukin; IFN: Interferon; LysoPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LysoPE: Lysophosphatidylethanolamine; ADMA: Asymmetricdimethylarginine; Rumino: Ruminococcaceae. Data adapted from Bajaj et al[69].

Obesity-associated hepatocellular carcinoma was recently attributed to molecular mechanisms such as chronic inflammation caused by adipose tissue remodeling and pro-inflammatory adipokine secretion, ectopic lipid accumulation and lipotoxicity, altered gut microbiota, and disrupted senescence in stellate cells, as well as insulin resistance leading to increased levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors. LPS, a pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognized by TLR4, initiated various inflammatory and oncogenic pathways to develop hepatocarcinogenesis and was enriched in the intestine of obese humans and rodents[97,107].

The complexity of the gut microbiota could be revealed using a recent systems biology culturomics-based method, genomic- and metagenomic-based methods, and proteomic- and metabolomic-based methods[11]. Samples from the gut or other microbiota (e.g., feces and saliva) are assayed on solid media selective for axenic cultivation. Isolated microbial colonies are subjected to peptide extraction before matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF)-based mass-spectrometry processing and species identification by peptide fingerprinting in the culturomics-based method. After standardized DNA extraction and quality control protocols, metagenomic sequences from the microbiota are generated by prosequencing selected 16S rRNA regions from microbial genomes by metagenomic-based methods. The detection of metabolites from samples such as feces, urine, blood, plasma and saliva, can be performed using metabolomic approaches including gas-chromatography mass spectrometry, proton nuclear magnetic spectroscopy (1H-NMR) and a liquid chromatography mass spectrometry in metabolomic-based method. These are recommended as platforms to understand further the gut-microbiota-liver metabolic network[11,108].

This review highlighted recent studies that reported an association between gut microbiota and host metabolism in cirrhosis. However, those reports mark the beginning of a new research area of the gut-liver axis. The liver is the central organ in host-metabolism and future studies are important and will form a new research area in the setting of the gut-microbiota-liver metabolic network. Hopefully this will contribute to interventions for the development of liver cirrhosis and related infectious and non-infectious complications including metabolic disturbances evoked by the gut-liver axis, especially in ALD, NAFLD and hepatocarcinogenesis.

CONCLUSION

Gut microbiota can produce a diverse range of compounds that play a major role in regulating the activity of distal organs and the liver is strategically positioned downstream of the gut. We are gaining increased insight into the close relationship between the gut and the liver evoked by systemic metabolic changes. The evaluation of the gut-microbiota-liver metabolic network and the intervention of these relationships using probiotics, synbiotics, prebiotics with sufficient nutrition might aid the development of treatment and prevention for liver cirrhosis patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ayumi Kajita for rearranging the reference papers in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflicting financial interests exist.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 19, 2015

First decision: July 20, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

P- Reviewer: Mach TH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Hamer HM, De Preter V, Windey K, Verbeke K. Functional analysis of colonic bacterial metabolism: relevant to health? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1–G9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minemura M, Shimizu Y. Gut microbiota and liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1691–1702. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov II, Honda K. Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riordan SM, Williams R. The intestinal flora and bacterial infection in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:744–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcovich M, Zocco MA, Roccarina D, Ponziani FR, Gasbarrini A. Prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: focusing on gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6693–6700. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukui H. Gut-liver axis in liver cirrhosis: How to manage leaky gut and endotoxemia. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:425–442. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quigley EM, Quera R. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: roles of antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S78–S90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quigley EM, Stanton C, Murphy EF. The gut microbiota and the liver. Pathophysiological and clinical implications. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1020–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabo G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:30–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visschers RG, Luyer MD, Schaap FG, Olde Damink SW, Soeters PB. The gut-liver axis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:576–581. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32836410a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Chierico F, Gnani D, Vernocchi P, Petrucca A, Alisi A, Dallapiccola B, Nobili V, Lorenza P. Meta-omic platforms to assist in the understanding of NAFLD gut microbiota alterations: tools and applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:684–711. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Minireview: Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1221–1238. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, Hammer RE, Williams SC, Crowley J, Yanagisawa M, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16767–16772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:235–243. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheppach W. Effects of short chain fatty acids on gut morphology and function. Gut. 1994;35:S35–S38. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1_suppl.s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzer P, Reichmann F, Farzi A. Neuropeptide Y, peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide in the gut-brain axis. Neuropeptides. 2012;46:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:241–259. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groh H, Schade K, Hörhold-Schubert C. Steroid metabolism with intestinal microorganisms. J Basic Microbiol. 1993;33:59–72. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620330115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swann JR, Want EJ, Geier FM, Spagou K, Wilson ID, Sidaway JE, Nicholson JK, Holmes E. Systemic gut microbial modulation of bile acid metabolism in host tissue compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4523–4530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006734107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin FP, Sprenger N, Montoliu I, Rezzi S, Kochhar S, Nicholson JK. Dietary modulation of gut functional ecology studied by fecal metabonomics. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5284–5295. doi: 10.1021/pr100554m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lord RS, Bralley JA. Clinical applications of urinary organic acids. Part 2. Dysbiosis markers. Altern Med Rev. 2008;13:292–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Xie G, Zhao A, Zhao L, Yao C, Chiu NH, Zhou Z, Bao Y, Jia W, Nicholson JK, et al. The footprints of gut microbial-mammalian co-metabolism. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:5512–5522. doi: 10.1021/pr2007945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama MT, Carlson JR. Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:173–178. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, Jackson W, Lu J, Jury J, Deng Y, Blennerhassett P, Macri J, McCoy KD, et al. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:599–609, 609.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keszthelyi D, Troost FJ, Masclee AA. Understanding the role of tryptophan and serotonin metabolism in gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, Angenent LT, Ley RE. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Said HM. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins in health and disease. Biochem J. 2011;437:357–372. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanfrey CC, Pearson BM, Hazeldine S, Lee J, Gaskin DJ, Woster PM, Phillips MA, Michael AJ. Alternative spermidine biosynthetic route is critical for growth of Campylobacter jejuni and is the dominant polyamine pathway in human gut microbiota. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43301–43312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto M, Benno Y. The relationship between microbiota and polyamine concentration in the human intestine: a pilot study. Microbiol Immunol. 2007;51:25–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serino M, Luche E, Gres S, Baylac A, Bergé M, Cenac C, Waget A, Klopp P, Iacovoni J, Klopp C, et al. Metabolic adaptation to a high-fat diet is associated with a change in the gut microbiota. Gut. 2012;61:543–553. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyte M. Microbial endocrinology as a basis for improved L-DOPA bioavailability in Parkinson’s patients treated for Helicobacter pylori. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:895–897. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyland NP, Cryan JF. A gut feeling about GABA: Focus on GABA(B) receptors. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:124. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2010.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Mahony SM, Clarke G, Borre YE, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brahe LK, Astrup A, Larsen LH. Is butyrate the link between diet, intestinal microbiota and obesity-related metabolic diseases? Obes Rev. 2013;14:950–959. doi: 10.1111/obr.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang HB, Wang PY, Wang X, Wan YL, Liu YC. Butyrate enhances intestinal epithelial barrier function via up-regulation of tight junction protein Claudin-1 transcription. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3126–3135. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willemsen LE, Koetsier MA, van Deventer SJ, van Tol EA. Short chain fatty acids stimulate epithelial mucin 2 expression through differential effects on prostaglandin E(1) and E(2) production by intestinal myofibroblasts. Gut. 2003;52:1442–1447. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohata A, Usami M, Miyoshi M. Short-chain fatty acids alter tight junction permeability in intestinal monolayer cells via lipoxygenase activation. Nutrition. 2005;21:838–847. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyoshi M, Usami M, Ohata A. Short-chain fatty acids and trichostatin A alter tight junction permeability in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Nutrition. 2008;24:1189–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Usami M, Miyoshi M, Kanbara Y, Aoyama M, Sakaki H, Shuno K, Hirata K, Takahashi M, Ueno K, Hamada Y, et al. Analysis of fecal microbiota, organic acids and plasma lipids in hepatic cancer patients with or without liver cirrhosis. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohira H, Fujioka Y, Katagiri C, Yano M, Mamoto R, Aoyama M, Usami M, Ikeda M. Butyrate enhancement of inteleukin-1β production via activation of oxidative stress pathways in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated THP-1 cells. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;50:59–66. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aoyama M, Kotani J, Usami M. Butyrate and propionate induced activated or non-activated neutrophil apoptosis via HDAC inhibitor activity but without activating GPR-41/GPR-43 pathways. Nutrition. 2010;26:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyoshi M, Sakaki H, Usami M, Iizuka N, Shuno K, Aoyama M, Usami Y. Oral administration of tributyrin increases concentration of butyrate in the portal vein and prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in rats. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloemen JG, Venema K, van de Poll MC, Olde Damink SW, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Short chain fatty acids exchange across the gut and liver in humans measured at surgery. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:657–661. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bloemen JG, Olde Damink SW, Venema K, Buurman WA, Jalan R, Dejong CH. Short chain fatty acids exchange: Is the cirrhotic, dysfunctional liver still able to clear them? Clin Nutr. 2010;29:365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyauchi S, Hirasawa A, Ichimura A, Hara T, Tsujimoto G. New frontiers in gut nutrient sensor research: free fatty acid sensing in the gastrointestinal tract. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:19–24. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09r09fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dockray GJ. Gastrointestinal hormones and the dialogue between gut and brain. J Physiol. 2014;592:2927–2941. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.270850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steele RD. Blood-brain barrier transport of the alpha-keto acid analogs of amino acids. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2060–2064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vijay N, Morris ME. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:1487–1498. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kekuda R, Manoharan P, Baseler W, Sundaram U. Monocarboxylate 4 mediated butyrate transport in a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:660–667. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maurer MH, Canis M, Kuschinsky W, Duelli R. Correlation between local monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) densities in the adult rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Begley M, Gahan CG, Hill C. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:625–651. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vaquero J, Monte MJ, Dominguez M, Muntané J, Marin JJ. Differential activation of the human farnesoid X receptor depends on the pattern of expressed isoforms and the bile acid pool composition. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:926–939. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, Thaiss CA, Kau AL, Eisenbarth SC, Jurczak MJ, et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eisenhofer G, Aneman A, Friberg P, Hooper D, Fåndriks L, Lonroth H, Hunyady B, Mezey E. Substantial production of dopamine in the human gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3864–3871. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asano Y, Hiramoto T, Nishino R, Aiba Y, Kimura T, Yoshihara K, Koga Y, Sudo N. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1288–G1295. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00341.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orihata M, Sarna SK. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase delays gastric emptying of solid meals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:660–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barrett E, Ross RP, O’Toole PW, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. γ-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ventura M, Turroni F, Zomer A, Foroni E, Giubellini V, Bottacini F, Canchaya C, Claesson MJ, He F, Mantzourani M, et al. The Bifidobacterium dentium Bd1 genome sequence reflects its genetic adaptation to the human oral cavity. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lyte M. Microbial endocrinology and infectious disease in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sadik R, Abrahamsson H, Björnsson E, Gunnarsdottir A, Stotzer PO. Etiology of portal hypertension may influence gastrointestinal transit. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1039–1044. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiest R, Lawson M, Geuking M. Pathological bacterial translocation in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, Puri P, Sterling RK, Luketic V, Stravitz RT, Siddiqui MS, Fuchs M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Lactobacillus GG modulates gut microbiome, metabolome and endotoxemia in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1113–1125. doi: 10.1111/apt.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lieber CS. Alcoholic fatty liver: its pathogenesis and mechanism of progression to inflammation and fibrosis. Alcohol. 2004;34:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1513–1524. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel GE, Bradford BU, Thurman RG. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:101–108. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aoyama T, Paik YH, Seki E. Toll-like receptor signaling and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/192543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farrell GC, van Rooyen D, Gan L, Chitturi S. NASH is an inflammatory disorder: pathogenic, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Gut Liver. 2012;6:149–171. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pinzone MR, Celesia BM, Di Rosa M, Cacopardo B, Nunnari G. Microbial translocation in chronic liver diseases. Int J Microbiol. 2012;2012:694629. doi: 10.1155/2012/694629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheth AA, Garcia-Tsao G. Probiotics and liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42 Suppl 2:S80–S84. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318169c44e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rayes N, Seehofer D, Hansen S, Boucsein K, Müller AR, Serke S, Bengmark S, Neuhaus P. Early enteral supply of lactobacillus and fiber versus selective bowel decontamination: a controlled trial in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2002;74:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200207150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rayes N, Seehofer D, Theruvath T, Schiller RA, Langrehr JM, Jonas S, Bengmark S, Neuhaus P. Supply of pre- and probiotics reduces bacterial infection rates after liver transplantation--a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Usami M, Miyoshi M, Kanbara Y, Aoyama M, Sakaki H, Shuno K, Hirata K, Takahashi M, Ueno K, Tabata S, et al. Effects of perioperative synbiotic treatment on infectious complications, intestinal integrity, and fecal flora and organic acids in hepatic surgery with or without cirrhosis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:317–328. doi: 10.1177/0148607110379813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pitsouni E, Alexiou V, Saridakis V, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Does the use of probiotics/synbiotics prevent postoperative infections in patients undergoing abdominal surgery? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:561–570. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jayakumar S, Carbonneau M, Hotte N, Befus AD, St Laurent C, Owen R, McCarthy M, Madsen K, Bailey RJ, Ma M, et al. VSL#3® probiotic therapy does not reduce portal pressures in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2013;33:1470–1477. doi: 10.1111/liv.12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rincón D, Vaquero J, Hernando A, Galindo E, Ripoll C, Puerto M, Salcedo M, Francés R, Matilla A, Catalina MV, et al. Oral probiotic VSL#3 attenuates the circulatory disturbances of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Liver Int. 2014;34:1504–1512. doi: 10.1111/liv.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pawar RR, Pardeshi ML, Ghongane BB. Study of effects of probiotic lactobacilli in preventing major complications in patients of liver cirrhosis. Value Health. 2012;3:206–211. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lunia MK, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S. Probiotics prevent hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1003–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loguercio C, Federico A, Tuccillo C, Terracciano F, D’Auria MV, De Simone C, Del Vecchio Blanco C. Beneficial effects of a probiotic VSL#3 on parameters of liver dysfunction in chronic liver diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:540–543. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000165671.25272.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferolla SM, Armiliato GN, Couto CA, Ferrari TC. Probiotics as a complementary therapeutic approach in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:559–565. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guerrero Hernández I, Torre Delgadillo A, Vargas Vorackova F, Uribe M. Intestinal flora, probiotics, and cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pereg D, Kotliroff A, Gadoth N, Hadary R, Lishner M, Kitay-Cohen Y. Probiotics for patients with compensated liver cirrhosis: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Nutrition. 2011;27:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao HY, Wang HJ, Lu Z, Xu SZ. Intestinal microflora in patients with liver cirrhosis. Chin J Dig Dis. 2004;5:64–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2004.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu JE, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Dong PL, Chen M, Duan ZP. Probiotic yogurt effects on intestinal flora of patients with chronic liver disease. Nurs Res. 2010;59:426–432. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181fa4dc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lata J, Novotný I, Príbramská V, Juránková J, Fric P, Kroupa R, Stibůrek O. The effect of probiotics on gut flora, level of endotoxin and Child-Pugh score in cirrhotic patients: results of a double-blind randomized study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:1111–1113. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282efa40e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gupta N, Kumar A, Sharma P, Garg V, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Effects of the adjunctive probiotic VSL#3 on portal haemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis and large varices: a randomized trial. Liver Int. 2013;33:1148–1157. doi: 10.1111/liv.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, Hafeezullah M, Varma RR, Franco J, Pleuss JA, Krakower G, Hoffmann RG, Binion DG. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1707–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eguchi S, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, Soyama A, Ichikawa T, Kanematsu T. Perioperative synbiotic treatment to prevent infectious complications in patients after elective living donor liver transplantation: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2011;201:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bengmark S. Ecoimmunonutrition: a challenge for the third millennium. Nutrition. 1998;14:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Delzenne NM, Williams CM. Prebiotics and lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:61–67. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karagozian R, Derdák Z, Baffy G. Obesity-associated mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Metabolism. 2014;63:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wall R, Ross RP, Shanahan F, O’Mahony L, Kiely B, Quigley E, Dinan TG, Fitzgerald G, Stanton C. Impact of administered bifidobacterium on murine host fatty acid composition. Lipids. 2010;45:429–436. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wall R, Ross RP, Shanahan F, O’Mahony L, O’Mahony C, Coakley M, Hart O, Lawlor P, Quigley EM, Kiely B, et al. Metabolic activity of the enteric microbiota influences the fatty acid composition of murine and porcine liver and adipose tissues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1393–1401. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nagao K, Inoue N, Wang YM, Shirouchi B, Yanagita T. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Zucker (fa/fa) rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:9–13. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kankaanpää PE, Yang B, Kallio HP, Isolauri E, Salminen SJ. Influence of probiotic supplemented infant formula on composition of plasma lipids in atopic infants. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyoshi H, Moriya K, Tsutsumi T, Shinzawa S, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Fujinaga H, Goto K, Todoroki T, Suzuki T, et al. Pathogenesis of lipid metabolism disorder in hepatitis C: polyunsaturated fatty acids counteract lipid alterations induced by the core protein. J Hepatol. 2011;54:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bugianesi E, Salamone F, Negro F. The interaction of metabolic factors with HCV infection: does it matter? J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S56–S65. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Irmisch G, Hoeppner J, Thome J, Richter J, Fernow A, Reisinger EC, Lafrenz M, Loebermann M. Serum fatty acids, antioxidants, and treatment response in hepatitis C infection: greater polyunsaturated fatty acid and antioxidant levels in hepatitis C responders. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Menzel N, Fischl W, Hueging K, Bankwitz D, Frentzen A, Haid S, Gentzsch J, Kaderali L, Bartenschlager R, Pietschmann T. MAP-kinase regulated cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity is essential for production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002829. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Popescu CI, Riva L, Vlaicu O, Farhat R, Rouillé Y, Dubuisson J. Hepatitis C virus life cycle and lipid metabolism. Biology (Basel) 2014;3:892–921. doi: 10.3390/biology3040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, Kanda H, Sato S, Oyadomari S, Iwakura Y, Oshima K, Morita H, Hattori M, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fiehn O, Barupal DK, Kind T. Extending biochemical databases by metabolomic surveys. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23637–23643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.173617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]